Abstract

Background

Early detection and treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors produces significant clinical benefits, but no consensus exists on optimal screening algorithms. This study aimed to evaluate the comparative and cost effectiveness of staged laboratory-based and non-laboratory-based total cardiovascular disease risk assessment.

Methods and Results

We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and cost-effectiveness modeling methods to compare strategies with and without laboratory components, and using single-stage and multistage algorithms, including approaches based on Framingham risk scores (laboratory-based assessments for all individuals). Analyses were conducted using data from 5,998 adults in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey without history of CVD, using 10-year CVD death as the main outcome. A micro-simulation model projected lifetime costs, quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) for 60 Framingham-based, non-laboratory-based, and staged screening approaches. Across strategies the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.774–0.780 in men and 0.812–0.834 in women. There were no statistically significant differences in AUC between multistage and Framingham-based approaches. In cost-effectiveness analyses, multistage strategies had ICERs of $52,000/QALY and $83,000/QALY for men and women, respectively. Single-stage/Framingham-based strategies were dominated (higher cost and lower QALYs) or had unattractive ICERs (>$300,000/QALY) compared to single-stage/non-laboratory-based and multistage approaches.

Conclusions

Non-laboratory-based CVD risk assessment can be useful in primary CVD prevention, as a substitute for laboratory-based assessments or as the initial component of a multistage approach. Cost-effective multistage screening strategies could avoid 25–75% of laboratory testing used in CVD risk screening with predictive power comparable to Framingham risks.

Keywords: screening, statin therapy, economics, primary prevention

Background

The clinical benefits from early detection and treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors are significant and well-established.1, 2 There is less agreement on what form an optimal CVD screening strategy should take in light of the various screening mechanisms available to stratify high- and low-risk persons for intervention.3–6 A recent review of CVD screening guidelines from major professional organizations in Western countries found that most guidelines called for assessments based on total CVD risk scores (such as Framingham or SCORE), and all of these risk scores included at least one laboratory-based component (i.e., total and/or HDL cholesterol).7

Non-laboratory-based risk assessment approaches use risk factors that can be assessed in a 5 or 10 minute clinical evaluation (such as age, smoking, blood pressure and body-mass index [BMI]) to predict CVD risk using less time and fewer resources compared to laboratory-based risk scores.8 We previously found that a non-laboratory-based CVD risk score discriminated CVD mortality risk similarly to the Framingham risk scores in a representative U.S. population in men, but there were significant differences in women.9 A potential two-staged CVD screening strategy could incorporate non-laboratory-based risk assessment as an initial step to identify patients who would benefit the most from further, laboratory-based testing (e.g., using Framingham risk) and recommend treatment decisions accordingly (i.e., those determined to be “high-risk” at either stage would receive treatment, others would not), thus optimizing the tradeoffs in predictive accuracy and cost compared to purely laboratory- or non-laboratory-based approaches.10

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the potential role of multistage screening using two types of analysis: 1) an external validation of the risk discrimination performance of various multistage specifications compared to the Framingham CVD risk score; and 2) a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) of various multistage specifications compared to Framingham- and non-laboratory-based screening strategies.

Methods

Primary CVD screening strategies were evaluated using two types of analyses: 1) receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis using observational data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III); and 2) model-based CEA using data from the 2005–2006 and 2007–2008 NHANES populations and other published sources. We considered three general types of screening strategies for our study: 1) single-stage/Framingham-based strategies, where all individuals aged 25–74 years were characterized as high- or low-risk based on their Framingham CVD risk (this approach is most consistent with current statin treatment guidelines for developed countries)6; 2) single-stage/non-laboratory-based strategies, which was similar to the single-stage/Framingham-based approach except there was no cholesterol testing, and risk characterization was based on non-laboratory-based total risk; and 3) multistage screening, where only a subset of individuals with intermediate-level risk results in a non-laboratory-based assessment would go on to receive laboratory testing, and individuals could be characterized as high-risk from Stage 1 (based on their non-laboratory-based risk) or Stage 2 (based on their Framingham CVD risk11).

Multistage screening strategy

Stage 1 in the proposed multistage screening approach was to calculate an individual’s total CVD risk (i.e., risk of experience fatal or non-fatal CVD event) using non-laboratory-based risk factors: age, sex, smoking status, history of diabetes, blood pressure treatment, systolic blood pressure, and body-mass index (BMI).8 The resulting total risk predictions were used to identify three types of patients from Stage 1: 1) High-risk patients; 2) Intermediate-risk patients that were identified for laboratory-based risk assessment; and 3) Low-risk patients. Framingham-based risk assessment results from Stage 2 dictated dichotomous risk characterization (i.e., high- or low-risk) for patients at intermediate risk (as identified by the Stage 1). This type of multistage screening strategy was therefore defined by three variables: 1) An upper bound for the non-laboratory-based risk assessment (to identify high-risk individuals from the first stage), xU; 2) A lower bound for the non-laboratory-based risk assessment (to identify low-risk individuals from the first stage), xL; and 3) A Framingham-based treatment threshold for those at intermediate-risk from the first stage, xT. In the risk discrimination analysis, we compared the Framingham CVD risk score (single-stage/laboratory-based strategy) to three versions of the multistage strategy that only used laboratory-based risk assessment for 75%, 50%, and 25% of the population. Appendix A1 describes these strategies in more detail. Figure 1 shows how a hypothetical multistage screening strategy would dictate laboratory screening and statin treatment decisions in the model-based CEA.

Figure 1.

A hypothetical two-staged primary CVD screening strategy that incorporates non-laboratory-based risk assessment

In a multistage screening framework, all individuals are assessed using non-laboratory-based risk assessment initially, and those at intermediate risk from the first stage are ultimately assessed using laboratory-based (Framingham) risk. xT is the laboratory-based treatment threshold, xL is the lower bound for laboratory testing (based on non-laboratory-based risk assessment), xU is the upper bound for laboratory testing (based on non-laboratory-based risk assessment). Compared to laboratory-based risk assessment strategy for all individuals, a multistage strategy would only result in different treatment decisions for individuals in regions I and VI.

-Regions I and II would be characterized as high-risk and recommended for statin treatment but not recommended for laboratory testing from Stage 1

-Region III would be characterized as intermediate-risk and recommended for laboratory testing from Stage 1, but not recommended for statin treatment based on Stage 2

-Region IV would be characterized as intermediate-risk from and recommended for laboratory testing from Stage 1, and recommended for statin treatment based on Stage 2

-Regions V and VI would characterized as low-risk and not be recommended for either laboratory testing or statin treatment from Stage 1

Study population for ROC analysis

NHANES III is a complex, multi-stage, nationally representative U.S. sample that contains health and nutrition information for 33,394 persons aged 2 months and older.12 Baseline values were collected from 1988–1994, and cause-specific mortality status is available for adults up to 2006, providing at least 10-year follow-up data for these individuals. The general methodology and results for the NHANES III are described elsewhere.13 Among the 20,050 adults in the NHANES III population, 14,973 were between the ages of 25 and 74 years, and 1,742 of these individuals were excluded from our study sample for history of myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke or cancer, resulting in 13,248 individuals that met our inclusion criteria. Among these individuals, 5,999 had complete data required to calculate the Framingham and non-laboratory-based risk scores. Although we focused our study on the population with complete data, we used imputed data to address the possibility of confounding due to missing values in our analysis. Appendix A2 describes the missing data and imputation approaches used in the risk discrimination analysis.

Risk discrimination analyses using ROC analysis

The performance in risk discrimination for each screening strategy was assessed using the individual score-specific ranks, with 10-year CVD death as the outcome of interest. Causes of death for the NHANES III population are verified by National Death Index (NDI) death certificate match. CVD deaths were defined by having an underlying cause of (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-10 codes in parentheses): Acute myocardial infarction (I21-I22), other acute ischemic heart disease (I24), atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (I25.0), all other forms of chronic ischemic heart disease (I20, I25.1-I25.9), or cerebrovascular diseases (I60-I69). Sex-specific ROC curves were generated and areas under the ROC curve (AUCs) were compared for the Framingham CVD risk score and three versions of the multistage screening approach defined by different boundary thresholds for intermediate risk. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were also calculated for each screening approach based on a commonly-used risk threshold (10-year Framingham CVD risk >10%6). The Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic for reclassification index could not be calculated due to the outcome data being restricted to fatal CVD events (the risk scores predict fatal and nonfatal CVD outcomes).14 We assumed a monotonic relationship between the risk of fatal CVD events observed in the data and the composite outcomes predicted by the CVD risk scores in the ROC curve analysis due to this data limitation. The non-laboratory-based score predicted both fatal and nonfatal CVD events similarly compared to laboratory-based scores in its derivation study, which supports our assumption of this monotonic relationship.8

Model-based CEA

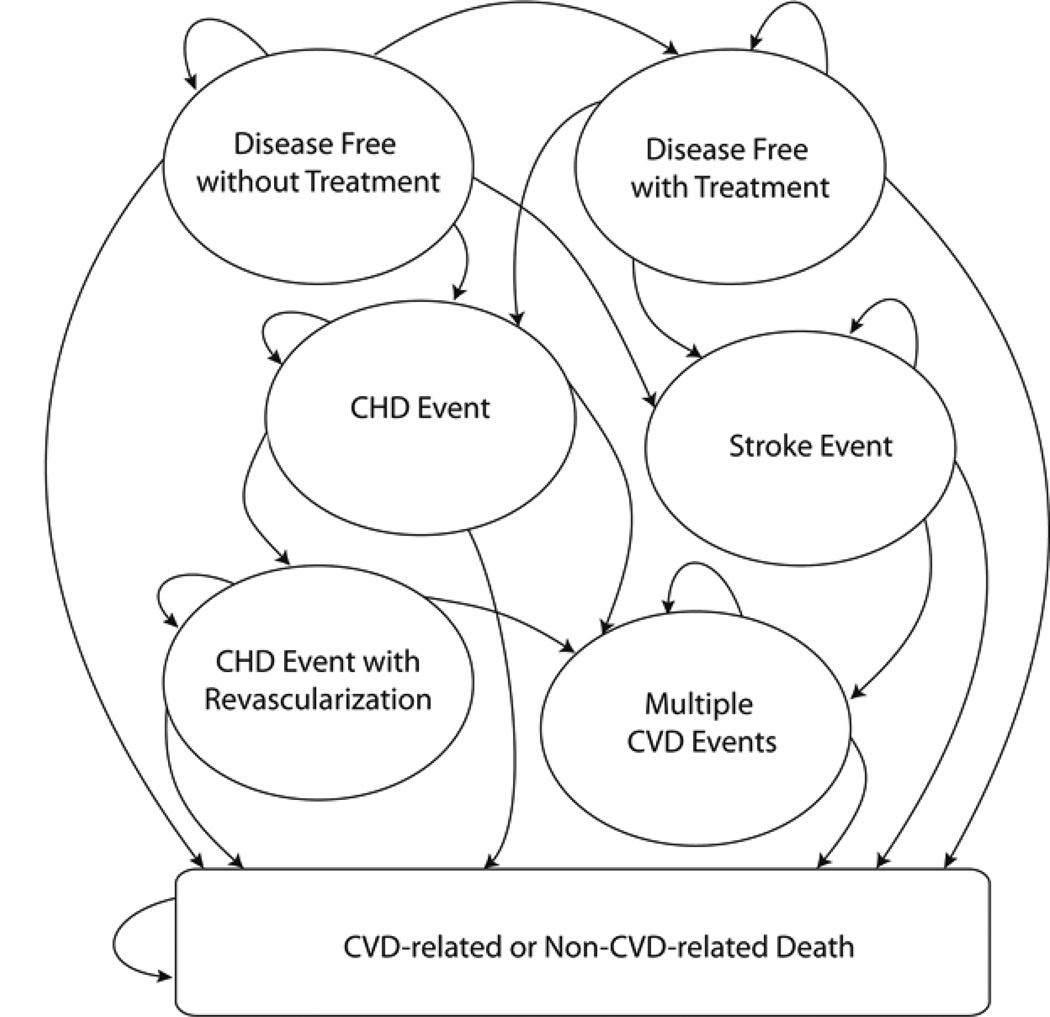

We developed a CVD micro-simulation model to assess the cost effectiveness of single-stage and multistage screening strategies that informed laboratory testing and statin treatment decisions. The model projected the lifetime health outcomes and CVD-related costs of 10,000 men and 10,000 women sampled from representative NHANES populations (2005–6 and 2007–8 waves) without history of CVD. Figure 2 shows the model structure in terms of general disease states and possible annual transitions. This structure was based on a previously published CVD Markov model where CVD risk is based on Framingham (laboratory-based) risk functions.15, 16 Because this study focuses on primary CVD prevention, all of the individuals started in the “Disease Free (without Treatment)” health state. Individuals in this health state were screened for CVD using non-laboratory-based (and potentially laboratory-based) risk assessment every five years at a routine general physician visit, until they were characterized as high-risk and received treatment, experienced a coronary heart disease (CHD) and/or stroke event, or died. Appendix A3 contains detailed information about the model structure, population, input parameters, and calibration of the disease model. Figure 2 depicts the micro-simulation model structure.

Figure 2.

Simplified depiction of the cardiovascular disease model

In the micro-simulation model, all individuals begin in the “Disease Free without Treatment” state. Transitions to “Disease Free with Treatment” depend on the type of screening strategy being evaluated. All other transitions are based on published estimates, with adjustments made for statin treatment when applicable.

We projected the average per-person costs and QALYs accrued using 20 total risk thresholds for each single-stage strategy and 20 combinations of thresholds for each multistage approach (Appendix A4 contains more detail for all 60 strategies evaluated). Strategies were ranked by cost, then incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were calculated; inefficient strategies were ruled out by strong dominance (higher incremental costs and lower incremental QALYs) or weak dominance (if they had higher incremental costs per QALY than a more effective strategy) per conventional CEA rules.17 Costs and QALYs were each discounted at 3% as recommend by the U.S. Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine.18 Risk thresholds were evaluated separately for men and women due to sexspecific differences in CVD prevalence and severity.

For multistage strategies, we included a sensitivity analysis that allowed for the possibility of higher retention and treatment initiation for patients identified as high-risk from Stage 1 compared to those identified as intermediate-risk in Stage 1 and high-risk in Stage 2, based on the premise that immediate treatment initiation would result in better adherence relative to delayed medication decisions. There is some evidence for the effect of statin initiation timing on adherence for secondary CVD prevention, but there is no analogous study for primary CVD prevention.19 Therefore, we assumed modest differential rates of 100% initiation from Stage 1 and 95% for Stage 2 (i.e., 5% of individuals characterized as high-risk from Stage 2 would not receive treatment due to lack of follow-up of laboratory results) in a sensitivity analysis.20

We varied the values of all input parameters across plausible ranges in deterministic sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of model-based CEA results. Given the relative importance of our assumptions around treatment initiation and additional physician visit costs associated with Stage 2, we performed two-way sensitivity analyses around these parameters. We also performed a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) to assess the overall uncertainty of our CEA results with respect to joint uncertainty around all model parameters. Detailed deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analysis methods are described in Appendix A5. There was no need for Institutional Review Board approval since there were no human subjects or animal subjects used for any of our analyses.

Results

Table 1 shows the risk profile characteristics of the NHANES III population used in the risk discrimination analysis by sex for the subpopulation for whom complete data were available. Appendix A6 shows the same information for the full population, which includes imputed values for missing data. From 10-year follow-up data for each individual (excluding those with imputed risk characteristics values), there were 118 and 58 CVD deaths for men and women, which represented 26.6% and 25.3% of the total deaths within the 10-year follow-up period, respectively.

Table 1.

Population characteristics of the NHANES III population that met inclusion criteria

| MEN (n=3,501) | WOMEN (n=2,497) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.0 | 45.6 |

| Currently smoker (%) | 53.8 | 59.4 |

| History of diabetes (%) | 6.5 | 7.8 |

| Blood pressure treatment (%) | 11.1 | 13.5 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 129.1 | 122.3 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 205.1 | 206.5 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 47.4 | 54.6 |

| Body-mass index (kg/m2) | 26.7 | 27.4 |

Figures 3a and 3b show the ROC curves for the Framingham CVD risk score, and the three versions of the multistage screening strategy evaluated in the risk discrimination analysis (where 75%, 50%, or 25% of the population would receive laboratory testing). In men, the AUC for the Framingham CVD risk score was 0.776 and the multistage strategies had AUCs of 0.774–0.780, with no significant differences between the Framingham and any multistage strategies (all p-values >0.5). In women, the AUC for the Framingham CVD risk score was 0.834 and the multistage strategies had AUCs of 0.812–0.827, with no significant differences between the Framingham and any multistage strategies (all p-values >0.05). Table 2 contain detailed information (AUCs with 95% confidence intervals, p-values compared to Framingham, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV) for all screening approaches analyzed in the risk discrimination analyses, and Appendix A6 contains these results for the imputed population analysis.

Figure 3.

a. ROC curves (10-year CVD death outcome) for multistage and Framingham CVD risk scores, men.

b. ROC curves (10-year CVD death outcome) for multistage and Framingham CVD risk scores, women.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for the three versions of the multistage screening strategy (with 25%, 50%, and 75% of the population receiving laboratory-based testing) and the Framingham CVD (“fram cvd”) scores, with 10-year CVD death as the outcome of interest, for individuals with complete data. For men (Figure 3a), the performances in risk discrimination, as assessed by AUC (i.e., area under the ROC curve) were 0.776, 0.774, 0.778, and 0.780 for the Framingham CVD and multistage (75%, 50%, and 25% of adults receiving laboratory-based risk assessments) risk scores, respectively, with a p-value for the differences compared to the Framingham score of 0.71, 0.74, and 0.57. For women (Figure 3b), the corresponding AUC results were 0.834, 0.827, 0.819, 0.812, with p-values for the differences compared to the Framingham score of 0.15, 0.14, and 0.06.

Table 2.

Risk discrimination results for multistage and universal Framingham strategies

| MEN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | AUC (95% CI) | p-value vs. Framingham | Sensitivity* | Specificity* | PPV* | NPV* |

| Framingham | 0.776 (0.733-0.819) | -- | 0.814 | 0.516 | 0.055 | 0.988 |

| Multistage75** | 0.774 (0.730-0.819) | 0.710 | 0.458 | 0.886 | 0.124 | 0.979 |

| Multistage50** | 0.778 (0.734-0.822) | 0.743 | 0.695 | 0.766 | 0.094 | 0.986 |

| Multistage25** | 0.780 (0.736-0.824) | 0.567 | 0.788 | 0.636 | 0.070 | 0.988 |

| WOMEN | ||||||

| Strategy | AUC (95% CI) | p-value vs. Framingham | Sensitivity* | Specificity* | PPV* | NPV* |

| Framingham | 0.834 (0.782-0.885) | -- | 0.793 | 0.759 | 0.073 | 0.994 |

| Multistage75** | 0.827 (0.773-0.880) | 0.152 | 0.552 | 0.885 | 0.103 | 0.988 |

| Multistage50** | 0.819 (0.764-0.875) | 0.140 | 0.741 | 0.761 | 0.069 | 0.992 |

| Multistage25** | 0.812 (0.756-0.869) | 0.063 | 0.828 | 0.635 | 0.051 | 0.994 |

Using >10% 10-year Framingham CVD risk as positivity criterion (for multistage strategies, this is only applied to individuals at intermediate risk, since Framingham risk would not be known for others). Those with non-laboratory-based risk >xU in multistage also used for positivity criterion.

Multistage formulations that resulted in 75%, 50%, and 25% of the population receiving laboratory testing.

Table 3 show the lifetime, discounted, per-person total cost and QALY results for the non-dominated single-stage/Framingham-based, single-stage/non-laboratory-based, and multistage screening strategies included in the model-based CEA. In the base-case analysis, there were no single-stage/Framingham-based strategies on the efficient frontier (i.e., all of the single-stage/Framingham-based strategies were dominated) for men, and only one for women (at the highest cost and QALY result, with an ICER of $330,000/QALY). At a WTP for health estimate of $50,000/QALY, single-stage/non-laboratory-based thresholds of >2% and >7.5% would be optimal primary CVD screening strategies for men and women, respectively. At a WTP for health estimate of $100,000/QALY, different forms of multistage screening strategies would be optimal for men and women. Various forms of single-stage/non-laboratory-based and multistage strategies would be optimal at lower WTP estimates ($8,000-$45,000/QALY).

Table 3.

Base-case cost-effectiveness results for non-dominated multistage and single-stage primary CVD screening strategies for adults in the U.S.

| MEN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy type | Threshold(s) | Costs | QALYs | ICER |

| No treatment or lab screening | -- | $15,988 | 19.593 | -- |

| Single-stage, non-lab-based | >12.5% non-lab risk | $16,524 | 19.668 | $7,100 |

| Multistage28* | xL=7.5%, xU=25%, xT=10% | $16,702 | 19.684 | $12,000 |

| Multistage15* | xL=3%, xU=5%, xT=5% | $17,043 | 19.706 | $15,000 |

| Single-stage, non-lab-based | >2% non-lab risk | $17,232 | 19.710 | $46,000 |

| Multistage24* | xL=0.5%, xU=2%, xT=1% | $17,387 | 19.713 | $52,000 |

| WOMEN | ||||

| Strategy type | Threshold(s) | Costs | QALYs | ICER |

| No treatment or lab screening | -- | $8,971 | 21.301 | -- |

| Single-stage, non-lab-based | >15% non-lab risk | $9,748 | 21.344 | $18,000 |

| Single-stage, non-lab-based | >10% non-lab risk | $9,992 | 21.349 | $45,000 |

| Single-stage, non-lab-based | >7.5% non-lab risk | $10,167 | 21.352 | $50,000 |

| Multistage56* | xL=1%, xU=7.5%, xT=3% | $10,589 | 21.358 | $83,000 |

| Single-stage, Framingham-based | >3% Framingham risk | $10,697 | 21.358 | $330,000 |

Multistage formulations that resulted in 28%, 15%, 24%, and 56% of the population receiving laboratory testing.

Model-based CEA results were most sensitive to variations in stage-specific physician costs and treatment initiation assumptions, statin costs, disutility associated with taking statins, statins-induced diabetes, and model time horizons. Specifically, excluding extra physician costs (to follow-up on laboratory results) associated with Stage 2 favored approaches that involved laboratory testing (i.e., single-stage/Framingham-based and multistage), higher treatment initiation from Stage 1 favored the single-stage/non-laboratory-based approach, while higher statin costs, larger disutility from taking statins, statin-induced diabetes risks, or lower model time horizons favored stricter (i.e., higher) treatment thresholds for all types of strategies. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis results were similar to the base-case findings. Appendices A5 and A7 contain details on the methods and results of the sensitivity analysis, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we proposed and evaluated a multistage primary CVD screening framework for adults in the U.S. without history of CVD. Our discrimination analysis showed that multistage screening approaches discriminated risk of CVD death comparably to the Framingham risk score while avoiding 25–75% of laboratory tests that would be used for primary CVD prevention. We also found that cost-effective screening guidelines (assuming commonly-used cost-effectiveness thresholds of $50,000–100,000/QALY) included non-laboratory-based risk assessment as a single stage or as part of multistage screening approach. Single-stage/Framingham-based screening, which is the approach that is most consistent with current screening recommendations in developed countries, was dominated or offered poor value for money based on typical standards for cost-effectiveness ratios (e.g. with ICER > $300,000/QALY, which significantly exceeds oft-used benchmarks of $50,000 or $100,000 per QALY) in our base-case cost-effectiveness analysis.21 Our cost-effectiveness results were most sensitive to assumptions regarding statin costs, disutility associated with taking statins, statin-induced diabetes, model time horizon, extra physician visit costs associated with laboratory testing, and the effect of treatment initiation timing on statin adherence.

Our risk discrimination results would confirm intuitions physicians might hold for very low- and very high-risk individuals screened for primary CVD risk, which is that laboratory testing will not change the risk assessment and treatment decisions in most cases. Cholesterol information might influence decisions for those at intermediate risk, especially considering previous evidence that there were significant differences in predicting CVD death between the Framingham and non-laboratory-based score in women.9 In this study we found no significant difference between the multistage screening approaches and the Framingham risk score in the same population. In our model-based CEA, we assumed that cholesterol levels influenced the underlying risk in patients (and non-laboratory-based risk assessment was only used a proxy for this true Framingham-based risk function), and still found that universal laboratory testing was an inefficient use of healthcare resources compared to non-laboratory-based or multistage approaches.

A recent modeling study by Chamnan et al. assessed the impact of a multistage screening framework that incorporated simple CVD risk assessment (using the Cambridge risk score) as an initial phase, and found that their multistage approach could produce a similar number of CVD events avoided compared to more expensive laboratory-based strategies in the UK .10 Costs were not explicitly modeled in that study, however, and screening and treatment thresholds were based on relatively arbitrary cutoffs (i.e., 20% of Cambridge score risk distribution) as opposed to optimized thresholds informed by CEA. Despite the differences in study approaches, our risk discrimination and cost-effectiveness findings support the policy conclusions from that study, which is that non-laboratory-based and multistage screening guidelines might save enough resources from reduced laboratory tests to justify any reduction in screening accuracy from the lack of cholesterol information.

Recent studies have evaluated the cost-effectiveness of primary CVD screening guidelines for statin treatment decisions in developed countries, but none of these economic evaluations incorporated a non-laboratory-based screening component.22–26 The non-laboratory-based and multistage screening frameworks are consistent with the evolving trend of primary risk CVD assessment, which is moving away from single risk factor-based guidelines to total risk-based (or “personalized”) approaches.27 The incorporation of a non-laboratory-based component can allow physicians to make treatment decisions faster and at lower costs compared to current laboratory-based recommendations. Our study is the first to evaluate the tradeoffs between risk discrimination performance, screening costs, and health benefits after incorporating simple risk assessment.

Our study has several important limitations. First, the outcome in our risk discrimination (ROC curve) analysis did not include nonfatal CVD events, but the non-laboratory-based risk score was shown to predict fatal and nonfatal CVD outcomes with similar accuracy compared to laboratory-based approaches.8 Our model-based CEA, however, explicitly modeled both fatal and nonfatal CVD events and their cost, morbidity, and mortality implications. Second, we assumed that the benefits from statin treatment were constant for a long time horizon and across a wide spectrum of risk in the model-based CEA. Although most statin trials have not extended beyond five years, the former assumption is commonly made in modeling studies with lifetime horizons (with treatment adjustments made for compliance and adverse events).23–26, 28, 29 The latter assumption is supported by findings from the recent JUPITER trial and Cholesterol Treatment Trialist’s (CTT) Collaborators’ meta-analysis, which suggested that statin benefits are not different between healthy and higher-risk individuals.30, 31 Third, we only considered age-constant screening and treatment thresholds in our study, although there is evidence that age-specific thresholds could result in efficiency gains.22 While we recognize that younger individuals have longer tails of life expectancy, and this could affect optimal specifications of treatment thresholds, we opted to only consider age-constant thresholds to minimize the complexity of our policy recommendations. Fourth, our micro-simulation model was biased in favor of the Framingham-based screening strategies due to the underlying (Framingham) risk functions that determined CVD outcomes in the model. This assumption was conservative in terms of the role of non-laboratory-based and multistage risk screening strategies, which were shown to be cost effective relative to Framingham-based screening despite this bias.

Our cost effectiveness results suggest that the benefits treating individuals for primary CVD prevention with statins would outweigh the costs and risks of taking these drugs. Some have argued that statins are over-prescribed in individuals without history of CVD.32 However, our empirical analysis of the NHANES III population shows that multistage screening could be applied to any targeted primary prevention strategy, such as smoking cessation or intensive diet and exercise interventions, if a statin-based approach is not justified. Additionally, although we found that cost-effective treatment thresholds were sensitive to several statin-related model parameters (such as stain price, disutility associated with taking statins, and statin-induced diabetes), all efficient screening approaches in these scenarios were still heavily based on non-laboratory-based and/or multistage strategies.

Our multistage screening framework is relatively more complex than single-stage strategies and recent modeling studies have evaluated the use of novel CVD biomarkers (such as C-reactive protein) or more detailed treatment algorithms (that vary statin type and/or dosage based on additional risk thresholds) that were not considered in our analysis.25, 33 While we do not question the potential importance of these additional considerations, we opted to focus on the incorporation of the non-laboratory-based screen stage instead of attempting to simultaneously evaluate a large number of factors that could influence the efficiency of CVD screening guidelines. Future observational and model-based analyses can incorporate these considerations, and other developments related to CVD screening and treatment, into multistage screening studies.

Policy Implications and Conclusions

Previous studies have identified the potential for efficiency gains from incorporating non-laboratory-based into a multistage primary CVD screening framework. Our study explicitly evaluated the tradeoff between lower costs and reduced screening accuracy from substituting simple risk assessment for conventional laboratory-approaches. In our risk discrimination analyses we found that multistage screening approaches could predict 10-year CVD death comparably to the Framingham risk score while saving 25–75% laboratory testing used in primary CVD screening efforts. We also found that universal laboratory-based guidelines (i.e., single-stage/Framingham-based) were not efficient screening options compared to non-laboratory-based or multistage screening frameworks across a wide range of relevant willingness-to-pay estimates for health ($10,000–$100,000/QALY). Future studies can apply this multistage screening framework in other developed countries, as well as in low- and middle-income countries, where the screening and treatment conditions would likely lead to different formulations of optimized laboratory testing and statin treatment thresholds.

Supplementary Material

What is Known

Identification of high-risk individuals for statin treatment initiation is a widely-recommended primary prevention strategy.

Most primary cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines in developed countries recommend assessing cardiovascular disease risk using total risk scores, such as the Framingham risk score, that require cholesterol information.

A simple non-laboratory-based cardiovascular disease risk score has been developed and validated for the U.S. population that could be used as a substitute for or in conjunction with laboratory-based scores.

What this Article Adds

Up to 75% of cholesterol laboratory testing used for primary cardiovascular disease prevention in the U.S. could be avoided under a multistage screening approach (that utilizes non-laboratory-based screening as an initial test) without significant reductions in cardiovascular disease mortality prediction.

Non-laboratory-based cardiovascular disease risk assessment would part of any cost-effective primary prevention screening approach in the U.S., either as single test or as part of a multistage screening framework.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: Dr. Thomas A. Gaziano is supported by Grant No. 5R01HL104284-03 to the Harvard School of Public Health from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Milton C. Weinstein has a consulting relationship with Optuminsight, a company that does economic analyses for the pharmaceutical and device industries. All other authors report no conflict of interest disclosures.

References

- 1.Jackson R, Lynch J, Harper S. Preventing coronary heart disease. BMJ. 2006;332:617–618. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7542.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manuel DG, Kwong K, Tanuseputro P, Lim J, Mustard CA, Anderson GM, Ardal S, Alter DA, Laupacis A. Effectiveness and efficiency of different guidelines on statin treatment for preventing deaths from coronary heart disease: Modelling study. BMJ. 2006;332:1419. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38849.487546.DE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosca L. Guidelines for prevention of cardiovascular disease in women: A summary of recommendations. Prev Cardiol. 2007;10(Suppl 4):19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1520-037x.2007.07255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graham I, Atar D, Borch-Johnsen K, Boysen G, Burell G, Cifkova R, Dallongeville J, De Backer G, Ebrahim S, Gjelsvik B, Herrmann-Lingen C, Hoes A, Humphries S, Knapton M, Perk J, Priori SG, Pyorala K, Reiner Z, Ruilope L, Sans-Menendez S, Op Reimer WS, Weissberg P, Wood D, Yarnell J, Zamorano JL, Walma E, Fitzgerald T, Cooney MT, Dudina A, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Funck-Brentano C, Filippatos G, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Altiner A, Bonora E, Durrington PN, Fagard R, Giampaoli S, Hemingway H, Hakansson J, Kjeldsen SE, Larsen L, Mancia G, Manolis AJ, Orth-Gomer K, Pedersen T, Rayner M, Ryden L, Sammut M, Schneiderman N, Stalenhoef AF, Tokgozoglu L, Wiklund O, Zampelas A. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Full text. Fourth joint task force of the european society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(Suppl 2):S1–S113. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000277983.23934.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McPherson R, Frohlich J, Fodor G, Genest J, Canadian Cardiovascular S. Canadian cardiovascular society position statement--recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2006;22:913–927. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(06)70310-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Third report of the national cholesterol education program (ncep) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel iii) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferket BS, Colkesen EB, Visser JJ, Spronk S, Kraaijenhagen RA, Steyerberg EW, Hunink MG. Systematic review of guidelines on cardiovascular risk assessment: Which recommendations should clinicians follow for a cardiovascular health check? Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:27–40. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaziano TA, Young CR, Fitzmaurice G, Atwood S, Gaziano JM. Laboratory-based versus non-laboratory-based method for assessment of cardiovascular disease risk: The nhanes i follow-up study cohort. Lancet. 2008;371:923–931. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60418-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pandya A, Weinstein MC, Gaziano TA. A comparative assessment of non-laboratory-based versus commonly used laboratory-based cardiovascular disease risk scores in the nhanes iii population. PloS one. 2011;6:e20416. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chamnan P, Simmons RK, Khaw KT, Wareham NJ, Griffin SJ. Estimating the population impact of screening strategies for identifying and treating people at high risk of cardiovascular disease: Modelling study. BMJ. 2010;340:c1693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The framingham heart study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plan and operation of the third national health and nutrition examination survey, 1988-94. Series 1: Programs and collection procedures. Vital and health statistics. Ser. 1, Programs and collection procedures. 1994:1–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook NR, Ridker PM. Advances in measuring the effect of individual predictors of cardiovascular risk: The role of reclassification measures. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;150:795–802. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-11-200906020-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaziano TA, Steyn K, Cohen DJ, Weinstein MC, Opie LH. Cost-effectiveness analysis of hypertension guidelines in south africa: Absolute risk versus blood pressure level. Circulation. 2005;112:3569–3576. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.535922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaziano TA, Opie LH, Weinstein MC. Cardiovascular disease prevention with a multidrug regimen in the developing world: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:679–686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69252-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunink MG, Glasziuo P, Siegel J, Weeks J, Pliskin J, Elstein A, Weinstein MC. Decision making in health and medicine. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB. Recommendations of the panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276:1253–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muhlestein JB, Horne BD, Bair TL, Li Q, Madsen TE, Pearson RR, Anderson JL. Usefulness of in-hospital prescription of statin agents after angiographic diagnosis of coronary artery disease in improving continued compliance and reduced mortality. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:257–261. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casalino LP, Dunham D, Chin MH, Bielang R, Kistner EO, Karrison TG, Ong MK, Sarkar U, McLaughlin MA, Meltzer DO. Frequency of failure to inform patients of clinically significant outpatient test results. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1123–1129. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cutler DM, Rosen AB, Vijan S. The value of medical spending in the united states, 1960-2000. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;355:920–927. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greving JP, Visseren FL, de Wit GA, Algra A. Statin treatment for primary prevention of vascular disease: Whom to treat? Cost-effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d1672. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pletcher MJ, Lazar L, Bibbins-Domingo K, Moran A, Rodondi N, Coxson P, Lightwood J, Williams L, Goldman L. Comparing impact and cost-effectiveness of primary prevention strategies for lipid-lowering. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:243–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazar LD, Pletcher MJ, Coxson PG, Bibbins-Domingo K, Goldman L. Cost-effectiveness of statin therapy for primary prevention in a low-cost statin era. Circulation. 2011;124:146–153. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.986349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee KK, Cipriano LE, Owens DK, Go AS, Hlatky MA. Cost-effectiveness of using high-sensitivity c-reactive protein to identify intermediate- and low-cardiovascular-risk individuals for statin therapy. Circulation. 2010;122:1478–1487. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.947960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statin cost-effectiveness in the united states for people at different vascular risk levels. Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2009;2:65–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.808469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens DK. Improving practice guidelines with patient-specific recommendations. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:638–639. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-9-201105030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: Prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prosser LA, Stinnett AA, Goldman PA, Williams LW, Hunink MG, Goldman L, Weinstein MC. Cost-effectiveness of cholesterol-lowering therapies according to selected patient characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:769–779. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mihaylova B, Emberson J, Blackwell L, Keech A, Simes J, Barnes EH, Voysey M, Gray A, Collins R, Baigent C. The effects of lowering ldl cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: Meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380:581–590. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60367-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FAH, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJP, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT, Glynn RJ, Grp JS. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated c-reactive protein. New Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Redberg RF, Katz MH. Healthy men should not take statins. JAMA. 2012;307:1491–1492. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayward RA, Krumholz HM, Zulman DM, Timbie JW, Vijan S. Optimizing statin treatment for primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:69–77. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.