Abstract

Purpose

To generate a map of local recurrences after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) for patients with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) and to model an adjuvant radiation therapy planning treatment volume (PTV) that encompasses a majority of local recurrences.

Methods and Materials

Consecutive patients with resectable PDA undergoing PD and 1 or more computed tomography (CT) scans more than 60 days after PD at our institution were reviewed. Patients were divided into 3 groups: no adjuvant treatment (NA), chemotherapy alone (CTA), or chemoradiation (CRT). Cross-sectional scans were centrally reviewed, and local recurrences were plotted to scale with respect to the celiac axis (CA), superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and renal veins on 1 CT scan of a template post-PD patient. An adjuvant clinical treatment volume comprising 90% of local failures based on standard expansions of the CA and SMA was created and simulated on 3 post-PD CT scans to assess the feasibility of this planning approach.

Results

Of the 202 patients in the study, 40 (20%), 34 (17%), and 128 (63%) received NA, CTA, and CRT adjuvant therapy, respectively. The rate of margin-positive resections was greater in CRT patients than in CTA patients (28% vs 9%, P = .023). Local recurrence occurred in 90 of the 202 patients overall (45%) and in 19 (48%), 22 (65%), and 49 (38%) in the NA, CTA, and CRT groups, respectively. Ninety percent of recurrences were within a 3.0-cm right-lateral, 2.0-cm left-lateral, 1.5-cm anterior, 1.0-cm posterior, 1.0-cm superior, and 2.0-cm inferior expansion of the combined CA and SMA contours. Three simulated radiation treatment plans using these expansions with adjustments to avoid nearby structures were created to demonstrate the use of this treatment volume.

Conclusions

Modified PTVs targeting high-risk areas may improve local control while minimizing toxicities, allowing dose escalation with intensity-modulated or stereotactic body radiation therapy.

Introduction

Of an estimated 45,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer in the United States in 2013 (1), only 20% of patients will present with resectable disease (2). However, even in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer, the outcomes are poor, with 5-year survival rates of 18% to 25% (3, 4) and local recurrence rates of 20% to 60% after adjuvant therapy (5–7). Autopsy data suggest that local recurrence occurs in 70% to 80% of patients, either alone or synchronously with distant failure (8, 9). Local failure is thus a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Despite controversy surrounding optimal therapy, the standard adjuvant treatment for pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the United States includes both chemotherapy and chemoradiation (10–14). This is based on a phase III trial that demonstrated a survival advantage with adjuvant fluorouracil-based chemoradiation compared with surgery alone (10), bolstered by similar findings in large institutional studies (15, 16). The standard adjuvant radiation target volumes for pancreatic adenocarcinoma are based on Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) consensus guidelines (17) and are directed at the tumor bed and locoregional lymph nodes. Three-dimensional conformal radiation treatment (3D-CRT) or intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) may be used to treat these volumes. These radiation therapy courses require up to 6 weeks of treatment, and patients cannot receive full-dose chemotherapy during radiation. Although standard chemoradiation is generally well tolerated, the persistent burden of local recurrence suggests that standard adjuvant radiation target doses and volumes should be reconsidered.

We hypothesize that a thorough analysis of local failure patterns after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) can more accurately identify areas at the highest risk for local recurrence. This may allow reduction of target volumes, dose escalation, decreased treatment-related toxicity, or a combination of these. This study was designed to map the location of radiographic local recurrences relative to major blood vessels in the abdomen, allowing the use of vascular anatomy as a reference to construct a standard, reproducible target that includes areas at high risk for local failure.

Methods and Materials

Patient selection

Two hundred and two consecutive patients who had undergone PD, had histologically confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma between 2007 and 2010, and had at least 1 abdominal computed tomographic (CT) scan more than 60 days after resection available for review were included in this analysis. All patients had provided informed consent for treatment, and the study was approved by our internal institutional review board. Patients who received neoadjuvant therapy, who underwent resection other than PD, or who had periampullary or ampullary cancer were excluded. Follow-up information was obtained from hard-copy and electronic hospital charts.

Patients were grouped into the following categories based on adjuvant therapy received: no adjuvant therapy (NA), chemotherapy alone (CTA), or chemoradiation (CRT). Of patients who received CTA or CRT (n = 163), 75% received adjuvant treatment at our institution, and 25% were treated at another facility. Adjuvant chemotherapy consisted of a gemcitabine-based regimen in 74% of patients in the CRT or CTA group, and 26% received a 5-fluorouracil-based regimen. For patients treated at our institution, radiation was delivered by 3D-CRT or IMRT using fields based on RTOG guidelines (17). The median total dose and fraction size were 50.4 Gy and 1.8 Gy, respectively, administered with concurrent 5-fluorouracilebased or gemcitabine chemotherapy. The details of radiation therapy could not be fully assessed for patients treated elsewhere.

A radiologist specializing in pancreatic cancer identified local recurrences, defined as new radiographic evidence of tumor inferior to the diaphragm and superior to the bottom of the L3 vertebra, excluding hepatic or gastric metastases. Recurrences were typically not biopsy proven.

Failure mapping and treatment modeling

Recurrences were plotted on a template of 1 CT scan of a post-PD patient, using Pinnacle software (Philips Healthcare, Fitchburg, WI), creating a 3-dimensional map of local failures. The distances from the center of each local failure to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and celiac axis (CA) were measured; local failures were plotted in relation to these blood vessels, scaling for individual abdominal width.

An adjuvant radiation target volume for use in both fractionated IMRT and SBRT was designed to cover regions where local failures commonly occurred based on the 3-dimensional map. The CA and SMA were each contoured along the natural curve of the vessels superiorly and 1 cm and 3 cm inferiorly, respectively, from the center of the vessels’ origins. A combined contour structure of the CA and SMA was expanded to create 2 clinical target volumes (CTV): (1) CTV90 encompassing 90% of plotted recurrences; and (2) CTV80 encompassing 80% of plotted recurrences. We recommend an institution-dependent expansion of the CTV90 and CTV80, if considered necessary, to create the respective planning target volumes (PTV), PTV90 and PTV80. For this study we propose an adjuvant SBRT plan wherein no expansions to the CTVs are applied to generate the PTV, inasmuch as patients at our institution are treated with breath-hold techniques, then aligned with a cone-beam CT scan to spine, and finally shifted to clips placed in the tumor bed based on kilovolt imaging between each treatment field. PTV90 and PTV80 were adjusted to avoid the jejunum, bowel, and stomach by 3 mm to generate the final volumes, PTV90-final and PTV80-final. With the use of these final volumes, 3 simulation adjuvant SBRT treatment plans were created that delivered 25.0 Gy in 5.0-Gy fractions with early (α/β = 10) and late (α/β = 3) biological effective doses (BEDs) of 42.62 Gy and 77.92 Gy to PTV90-final and a simultaneous integrated boost to a total dose of 33.0 Gy in 6.6-Gy fractions with early and late BEDs of 54.8 Gy and 105.6 Gy to PTV80-final. These plans were delivered in 5 consecutive daily fractions over 1 to 2 weeks. No more than 1 cc of PTV80-final received more than 120% of the prescription dose, and more than 90% of each PTV received 100% of the prescription dose. Doses and organs at risk (OAR) constraints were based on a multicenter trial in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer that used fractionated SBRT (18). These plans were not used in clinical treatment.

A standard radiation plan that followed the RTOG 0848 protocol (19) was developed for each simulated patient by contouring the most proximal 1.0 cm of the CA and 3.0 cm of the SMA, preoperative tumor, pancreaticojejunostomy, surgical clips indicating regions of concern for residual tumor, and the aorta as directed. The CTV was created by merging the following expansions: CA, SMA, and PV by 1.0 cm in all directions, the PJ and surgical clips by 0.5 cm in all directions, and the aorta by 2.5 cm to the right, 1.0 cm to the left, 2.0 cm anteriorly, and 0.2 cm posteriorly. The PTV was established by expanding the CTV by 0.5 cm in all directions.

Finally, to evaluate the plan characteristics and dosimetric parameters of plans using conventional fractionation on the same 3 patients, we created a plan that delivered 51.2 Gy in 1.6-Gy fractions to PTV90-final with an integrated boost to 64.0 Gy in 2.0-Gy fractions to PTV80-final (32 fractions total) (Supplementary Table E1, available at www.redjournal.org).

Statistical analysis

Means, medians, and proportions were compared among subgroups using the 2-sided Student’s t-test, the Mann-Whitney U test, and the 2-sided Fisher’s exact test, respectively. A P value of ≤.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics software version 20.0 (International Business Machines Corporation, Chicago, IL). ROOT physics analysis software version 5.32 (20), a data analysis software developed at CERN (Centre Europeen de Recherche Nucleaire)for high energy physics data analysis (Geneva, Switzerland) was used to quantify the distances of local recurrence from the SMA and CA.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The median follow-up time for the entire cohort was 22.1 months (range, 3.1–94.7 months), specifically 9.1 months (range, 2.1–55.5 months), 22.7 months (range, 5.6–43.4 months), and 22.3 months (range, 3.3–94.7 months) for patients receiving NA, CTA, and CRT as adjuvant therapy, respectively. The baseline clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the 202 patients in the study, 40 (20%) had NA, 34 (17%) had CTA, and 128 (63%) had CRT as adjuvant therapy. The NA patients were older, with a median age of 71.3 years compared with 60.7 and 64.1 years in the CTA and CRT groups (P = .025 and P = .002, respectively). The patients receiving CRT were more likely to have had margin-positive resections than were those in the CTA group (28% vs 9%, P = .023). All other clinical characteristics were comparable among patients receiving NA, CTA, and CRT adjuvant therapy.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | All n = 202 |

NA n = 40 |

CTA n = 34 |

CRT n = 128 |

NA vs CTA P value |

NA vs CRT P value |

CTA vs CRT P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, median (range) | 65.3 (38.7, 88.3) | 71.3 (42.5, 88.3) | 60.7 (39.5, 87.3) | 64.1 (38.7, 87.3) | .025 | .002 | .666 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 105 (52) | 16 (40) | 17 (50) | 72 (56) | |||

| Female | 97 (48) | 24 (60) | 17 (50) | 56 (44) | .483 | .102 | .564 |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 182 (90) | 38 (95) | 32 (94) | 112 (88) | |||

| Other | 20 (10) | 2 (5) | 2 (6) | 16 (12) | >.999 | .247 | .368 |

| Tumor diameter, median (range) | 3 (1.2, 9.5) | 3 (1.5, 5.0) | 3.5 (1.5, 6.5) | 3 (1.2, 9.5) | .205 | .584 | .318 |

| T stage | |||||||

| T1 | 10 (5) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 6 (5) | |||

| T2 | 39 (19) | 7 (18) | 9 (26) | 23 (18) | |||

| T3 | 147 (73) | 28 (70) | 23 (68) | 96 (75) | |||

| T4 | 6 (3) | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | 3 (2) | .660 | .734 | .703 |

| N stage | |||||||

| N0 | 41 (20) | 7 (18) | 7 (21) | 27 (21) | |||

| N1 | 161 (80) | 33 (82) | 27 (79) | 101 (79) | .773 | .822 | >.999 |

| Margins | |||||||

| Negative | 154 (76) | 31 (78) | 31 (91) | 92 (72) | |||

| Positive | 48 (24) | 9 (22) | 3 (9) | 36 (28) | .129 | .545 | .023 |

| Differentiation | |||||||

| Well | 5 (2) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 4 (3) | |||

| Moderate | 138 (68) | 28 (70) | 22 (65) | 88 (69) | |||

| Poor | 61 (30) | 11 (28) | 13 (38) | 37 (29) | .694 | .983 | .621 |

| PD type | |||||||

| Classic | 99 (49) | 22 (55) | 20 (59) | 57 (45) | |||

| Pylorus-preserving | 103 (51) | 18 (45) | 14 (41) | 71 (55) | .816 | .279 | .177 |

| Any local recurrence | |||||||

| No | 112 (55) | 21 (52) | 12 (35) | 79 (62) | |||

| Yes | 90 (45) | 19 (48) | 22 (65) | 49 (38) | .164 | .357 | .007 |

| Any distant recurrence | |||||||

| No | 102 (50) | 17 (43) | 15 (44) | 70 (55) | |||

| Yes | 100 (50) | 23 (58) | 19 (56) | 58 (45) | .889 | .209 | .311 |

Abbreviations: CRT = chemoradiation therapy; CTA = chemotherapy alone; NA = no adjuvant therapy; PD = pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Local recurrence map

Local failures occurred in 90 of the 202 patients overall (45%), in 19 of the 40 patients (48%) receiving NA, in 22 of the 34 patients (65%) receiving CTA, and in 49 of the 129 patients (38%) receiving CRT (Table 1). The percentage of patients experiencing local recurrence was significantly greater in patients receiving CTA than in those receiving CRT (65% vs 38%, P = .007).

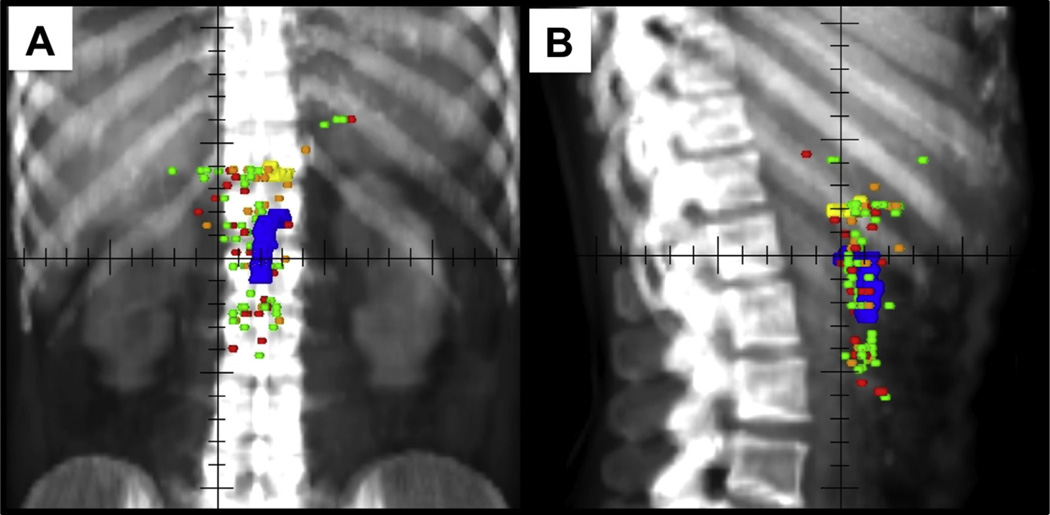

Patterns of local failure by type of adjuvant therapy are shown in Figure 1. Local recurrences are plotted with respect to the CA and SMA. Twenty-eight (31%) patients experienced recurrence closer to the CA, with a mean and standard deviation of the distance to the CA of 11.7 mm (3.0 mm), 10.6 mm (10.0 mm), and 18.8 mm (12.1 mm) in the NA, CTA, and CRT groups respectively. Sixty-two patients (69%) experienced recurrence closer to the SMA, with a mean and standard deviation of the distance to the SMA of 8.0 mm (7.5 mm), 4.5 mm (3.7 mm), and 6.4 mm (4.5 mm) for the NA, CTA, and CRT groups respectively.

Fig. 1.

Local recurrence map. (A) Anterior-posterior and (B) lateral views of local recurrence plots in relation to the celiac artery (yellow) and superior mesenteric artery (blue) after pancreaticoduodenectomy for patients receiving no adjuvant therapy (red), chemotherapy alone (orange), and chemoradiation (green).

Novel adjuvant field delineation and treatment planning

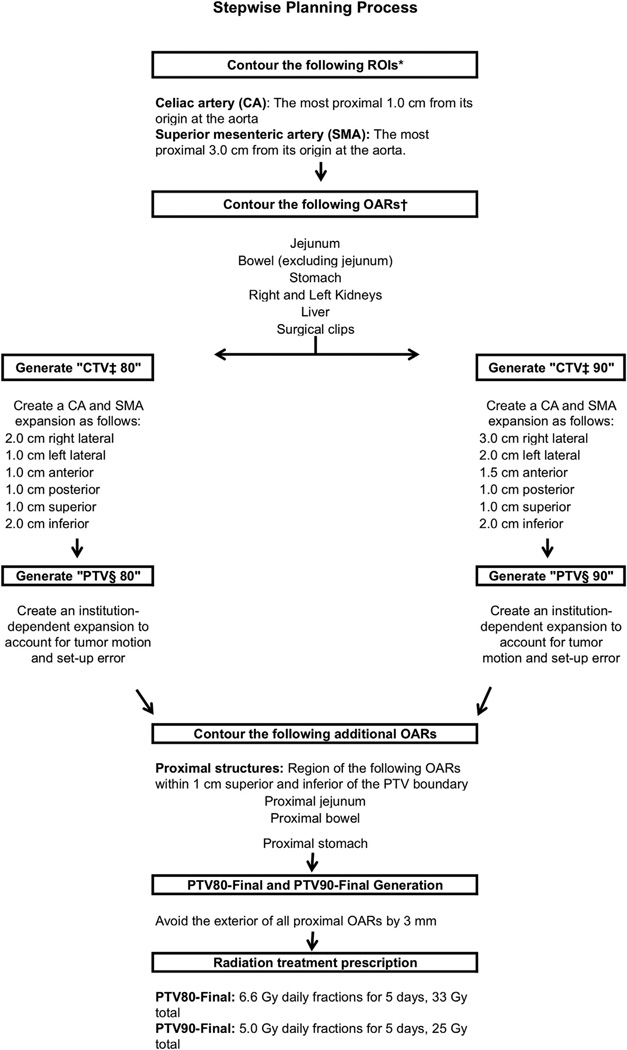

Stepwise planning process

Figure 2 outlines the procedure for developing an adjuvant radiation target volume containing areas at high risk for local recurrence based on the 3-dimensional map created in this study (Fig. 1). A unique gross tumor volume (GTV) was not defined, inasmuch as the plan is for radiation therapy after PD where no gross tumor is present; however, if the preoperative CT indicates that the tumor location was distant from the SMA or CA axis, or suspect nodes do not fall within the proposed field, then adjustments should be made or a standard plan should be considered.

Fig. 2.

Stepwise planning process. *ROI region of interest, †organ at risk, ‡clinical target volume, §planning target volume.

A CTV was constructed by expanding the combined CA and SMA contour structure to create a volume that contained areas where failure was common. Ninety percent of recurrences were encompassed by a 3.0-cm right-lateral, 2.0-cm left-lateral, 1.5-cm anterior, 1.0-cm posterior, 1.0-cm superior, and 2.0-cm inferior expansion of the combined CA and SMA contours to create CTV90. Eighty percent of recurrences were encompassed by a 2.0-cm right-lateral, 1.0-cm left-lateral, 1.0-cm anterior, 1.0-cm posterior, 1.0-cm superior, and 2.0-cm inferior expansion of the combined CA and SMA contours to create CTV80. An institution-dependent expansion could be created, if necessary, on both CTV80 and CTV90 to generate PTV80 and PTV90. Regional OARs included the jejunum, bowel, stomach, liver, and kidneys. The jejunum, bowel, and stomach OARs were avoided by adjusting the PTV80 and PTV90 to provide a fixed 3-mm avoidance of these OARs. PTV90-final and PTV80-final therefore target the regions where 80% and 90% of recurrences occur while dose to regional OARs is limited.

Radiation treatment planning incorporated a simultaneous integrated boost to deliver a total dose of 25 Gy in 5 fractions of 5 Gy to PTV90-final (larger volume) and 33 Gy in 5 fractions of 6.6 Gy to PTV80-final (smaller volume) by use of SBRT. Treatment plans were generated with 9 equally spaced, non-coplaner beams.

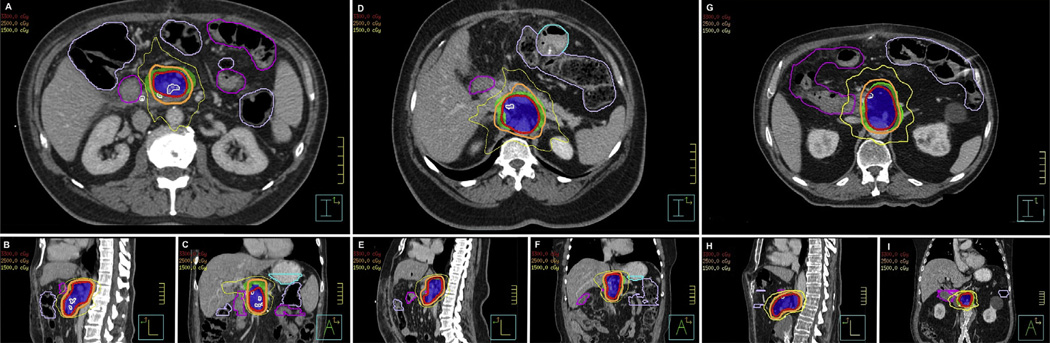

Treatment plan generation and dosimetric considerations

Figure 3 illustrates 3 simulated plans created by the stepwise planning process outlined in Figure 2. This resulted in PTV90-final volumes of 183 to 216 cc and PTV80-final volumes of 84 to 140 cc for the simulated plans. The dosimetric constraints and the corresponding radiation treatment characteristics for the SBRT plans are presented in Table 2. All plans achieved the same predefined dosimetric constraints as those required by a prospective multicenter trial of fractionated SBRT (18). Because SBRT is not standard practice, we have also included plan characteristics and dosimetric parameters of 3 plans using more conventional fractionation to deliver 51.2 Gy in 1.6-Gy fractions to PTV90-final and 64 Gy in 2.0-Gy fractions to PTV80-final in Supplementary Table E1 (available at www.redjournal.org).

Fig. 3.

Demonstration of proposed adjuvant plan for 3 simulated patients. Radiation treatment plans were created using the stepwise process. Axial, sagittal, and coronal views are shown for patient 1 (A, B, and C), patient 2 (D, E, and F), and patient 3 (G, H, and I). PTV90-final (green), PTV80-final (dark blue), 33 Gy isodose line (red), 25 Gy isodose line (orange), 15 Gy isodose line (khaki), proximal stomach (light blue), proximal bowel (purple), and proximal jejunum (pink) are indicated on each plan.

Table 2.

Plan characteristics and dosimetric parameters for 3 simulated patients

| Plan features | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PTV80-final | |||

| Volume | 123.0 cc | 83.7 cc | 139.6 cc |

| Coverage at 33 Gy | 91.6% | 97.5% | 92.5% |

| PTV90-final | |||

| Volume | 183.2 cc | 128.7 cc | 215.7 cc |

| Coverage at 25 Gy | 92.5% | 94.8% | 96.6% |

| Prescription percentage | 89.0% | 90.0% | 92.0% |

| OAR | Constraints | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jejunum | V15 <9 cc | 5.11 cc | 2.71 cc | 8.72 cc |

| V20 <3 cc | 1.00 cc | 1.22 cc | 0.60 cc | |

| Proximal jejunum | V33 <1 cc | 0.00 cc | 0.00 cc | 0.00 cc |

| Bowel | V15 <9 cc | 1.67 cc | 2.77 cc | 0.15 cc |

| V20 <3 cc | 0.00 cc | 1.49 cc | 0.00 cc | |

| Proximal bowel | V33 <1 cc | 0.00 cc | 0.04 cc | 0.00 cc |

| Stomach | V15 <9 cc | 0.00cc | 0.50 cc | 0.00 cc |

| V20 <3 cc | 0.00 cc | 0.00 cc | 0.00 cc | |

| Proximal stomach | V33 <1 cc | 0.00 cc | 0.00 cc | 0.00 cc |

| Liver | V12 <50 cc | 11.36% | 5.78% | 0.06% |

| Combined | V12 <75 cc | 0.42% | 13.57% | 1.29% |

| Spinal | V8 <1 cc | 0.47 cc | 0.04 cc | 0.92 cc |

| PTV | Constraints | |||

| PTV80-final | V42.9 <1cc | 0.14 cc | 0.34 cc | 0.92 cc |

Abbreviations: OAR organs at risk; PTV80-final = planning target volume containing 80% of mapped recurrences with avoidance of proximal organs at risk; PTV90-final = planning target volume containing 90% of mapped recurrences with avoidance of proximal organs at risk.

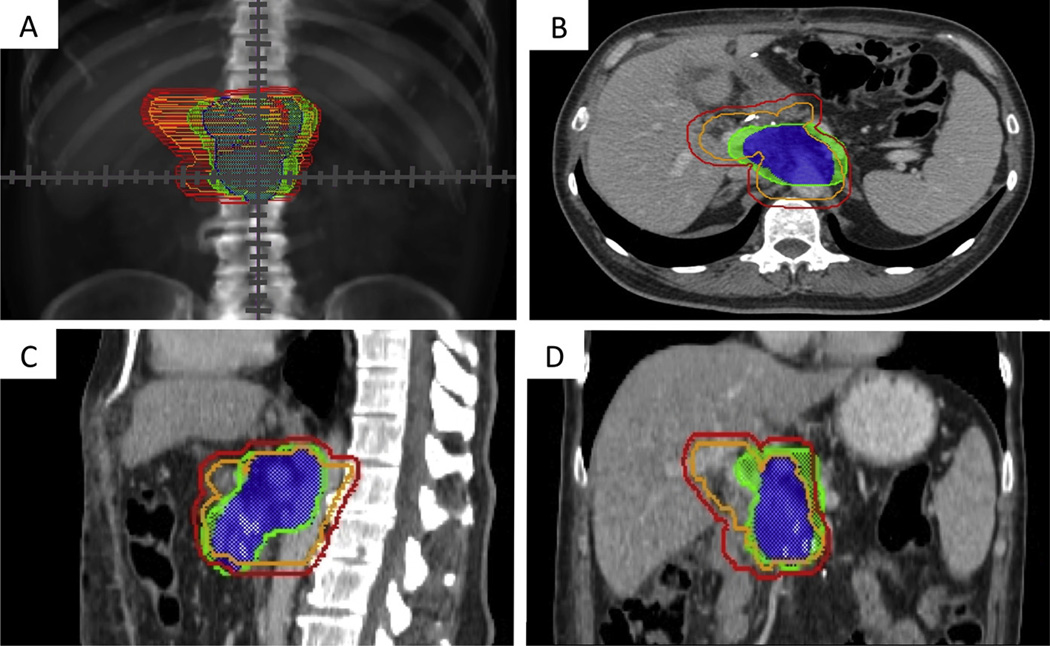

A standard plan that followed the RTOG 0848 protocol (19) was created for these same 3 simulation cases, resulting in CTVs of 201 cc, 276 cc, and 434 cc and PTVs of 350 cc, 460 cc, and 713 cc respectively. The patient with the largest CTV and PTV had an abdominal aortic aneurysm, resulting in larger volumes (caused by the required aortic expansion outlined in RTOG 0848) than those in the other 2 simulation cases. Figure 4 shows the RTOG 0848 CTV and PTV and the proposed PTV-80final and PTV-90final of 1 patient as an example of where areas could potentially be reduced to minimize the toxicity of adjuvant treatment.

Fig. 4.

A standard Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 0848 clinical target volume (orange) and planning target volume (red) are shown simultaneously with the proposed PTV80-final (blue) and PTV90-final (green) of this study on an anterior-posterior digitally reconstructed radiograph (A) and on axial (B), sagittal (C), and coronal (D) computed tomographic sections of 1 simulated patient as an example of where areas could potentially be reduced to minimize the toxicity of adjuvant treatment. PTV80-final = planning target volume containing 80% of mapped recurrences with avoidance of proximal organs at risk; PTV90-final = planning target volume containing 90% of mapped recurrences with avoidance of proximal organs at risk.

Discussion

Even with adjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiation, local failure remains a common cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. This is the first study to create an anatomic map of local recurrences from which specific areas at highest risk for local failure are identified, informing the design of smaller radiation target volumes. We propose an adjuvant treatment volume that is based on expansions of the SMA and CA because these vessels are along the retroperitoneal margin of the PD, a common region for local recurrence (Fig. 2). Treatment volumes using the proposed technique for 3 simulated plans were consistently smaller than those based on the RTOG 0848 protocol. Our proposed target volumes may enable dose escalation, hypofractionation, or both in an effort to improve outcomes in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

This unique treatment approach has several theoretical advantages. The proposed target volume significantly reduces the volume of irradiated tissue for patients receiving adjuvant radiation therapy, compared with historical standards. Although this reduced field excludes some regional nodal areas, the patterns of failure data presented here suggest that treating large fields may not be necessary because most local recurrences occur within a small volume surrounding the CA and SMA. Early clinical trials in locally advanced (21) (definitive) and resectable (22) (neoadjuvant) pancreatic cancer have also suggested that a smaller radiation field (treating the tumor alone with a small circumferential margin) is as effective as, and less toxic than, comprehensive nodal irradiation, allowing the concurrent administration of more intensive chemotherapy and perhaps earlier resumption of full-dose systemic therapy.

The choice of radiation dose (33 Gy in 6.6-Gy daily fractions) is supported by clinical experience with other gastrointestinal malignancies. A similar schedule (25 Gy in 5-Gy fractions) is commonly used for neoadjuvant therapy of rectal cancer and appears to be effective and well tolerated, although a much larger field is used (23, 24). The BED calculations using the linear-quadratic equation show that the BED of the proposed PTV80-final, which receives 33 Gy in 5 fractions, has early-effect and late-effect BEDs of 54.8 Gy and 105.6 Gy. This approximates the BED of standard chemoradiation (BED early/late 60 Gy/83.3 Gy), albeit with a somewhat higher late-effect BED. Given the effect of hypofractionation on true BED, the BED of the radiation regimen may be even higher, although the true BED of hypofractionated regimens is still unclear (25, 26).

Our treatment plan was designed without specific consideration to the original tumor location, in contrast to the current adjuvant radiation approach (RTOG 0848), which requires including the approximate location of the original tumor within the postoperative abdomen in the radiation target volume. In reality, significant variations in internal anatomy result from postoperative weight loss and major changes in gastrointestinal anatomy and motility, making accurate identification of the true preoperative location of the tumor difficult if not impossible. Our proposed target volumes are based on vascular anatomy, which is not significantly altered by pancreatic surgery and can be easily and reproducibly identified on simulation CT scans. Although the proposed plans in Figure 3 did not specifically target preoperative tumor volumes, surgical clips outlining the SMA margin of the tumor placed at the time of PD were still contained in the final planning target volumes. Nevertheless, we recommend fusing the preoperative and postoperative CT scans to ensure that the CA and SMA margins on the tumor fall within the proposed field to confirm coverage of areas at high risk for recurrence.

Although the majority of studies have evaluated SBRT in patients with locally advanced disease (27–29), 1 study by Hong and colleagues (30) evaluated neoadjuvant proton-based SBRT (25 Gy delivered in 5-Gy fractions) to the tumor and peripancreatic lymph nodes with concurrent 5-fluorouracil. No patients experienced grade 3 or 4 acute or chronic toxicities, with the caveat that the available median follow-up was short (12 months). A second study reported the use of adjuvant single-fraction SBRT (20–30 Gy) in 22 patients with close or positive margins (31). Notably, the study did not comment on the treatment planning process and specific dose constraints. No patients experienced grade 3 or 4 toxicity secondary to SBRT. Although additional data are necessary to enable assessment of the long-term toxicities of SBRT, the low rates of SBRT-related acute toxicity are promising subjects for prospective investigations, which are ongoing.

To our knowledge, this study represents the first detailed analysis of post-PD local recurrence patterns that reflects the type of adjuvant therapy received and maps recurrences relative to local vascular anatomy. In our series, patients receiving CRT were less likely than those treated with CTA to experience local recurrence, despite the higher proportion of margin-positive resections in those receiving CRT (28% vs 9%). We acknowledge a potential critique that the recurrence map is based on a systematic estimation of each recurrence location, and thus we cannot be certain that the estimation is exactly identical to the relative location of the original local failure. To minimize the impact of this uncertainty, a single radiologist specializing in abdominal CT identified and plotted all recurrences for the study. We are limited by the shorter follow-up times and the small number of recurrences in the NA and CTA groups in our study. With our available data, however, it does not appear that the anatomic distribution of recurrences varied significantly. Thus, these groups were combined when we defined our radiation target volume. Although we believe that increased dose to the high-risk area could result in improved local control, this redefined PTV should be evaluated in a prospective trial.

Conclusions

We demonstrate that a majority of local recurrences after PD are contained within a small region surrounding the CA and SMA. Treating the modified PTV generated in this study may allow for dose escalation with decreased toxicity by reducing the PTV. If the proposed PTV is treated with fractionated SBRT as opposed to standard CRT, it may allow for an increased BED to the tumor bed (26) and reduce chemotherapy delay. A combination of adjuvant fractionated SBRT with aggressive chemotherapy (FOLFIRINOX) and pancreatic tumor cell vaccine is currently being evaluated in a prospective pilot study (NCT01595321) (32).

Supplementary Material

Summary.

Local recurrences cause significant morbidity and mortality after surgery for resectable pancreatic cancer. This retrospective analysis maps local recurrences after surgery alone, adjuvant chemotherapy, or adjuvant chemoradiation. Based on these local failure patterns, a planning treatment volume was developed that encompasses 90% of recurrences. This proposed planning treatment volume is substantially smaller than traditional adjuvant treatment volumes and may allow for dose escalation and hypofractionation.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Claudio X. Gonzalez Family Foundation, the Flannery Family Foundation, the Alexander Family Foundation, the Keeling Family Foundation, and the DeSanti Family Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

Supplementary material for this article can be found at www.redjournal.org.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, et al. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2004;363:1049–1057. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15841-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron JL, Riall TS, Coleman J, et al. One thousand consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies. Ann Surg. 2006;244:10–15. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217673.04165.ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner M, Redaelli C, Lietz M, et al. Curative resection is the single most important factor determining outcome in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2004;91:586–594. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Hop WC, et al. Long-term survival and metastatic pattern of pancreatic and periampullary cancer after adjuvant chemoradiation or observation: Long-term results of EORTC trial 40891. Ann Surg. 2007;246:734–740. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318156eef3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffin JF, Smalley SR, Jewell W, et al. Patterns of failure after curative resection of pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer. 1990;66:56–61. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900701)66:1<56::aid-cncr2820660112>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tepper J, Nardi G, Sutt H. Carcinoma of the pancreas: Review of MGH experience from 1963 to 1973. Analysis of surgical failure and implications for radiation therapy. Cancer. 1976;37:1519–1524. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197603)37:3<1519::aid-cncr2820370340>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hishinuma S, Ogata Y, Tomikawa M, et al. Patterns of recurrence after curative resection of pancreatic cancer, based on autopsy findings. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, et al. DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1806–1813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalser MH, Ellenberg SS. Pancreatic cancer: adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch Surg. 1985;120:899–903. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1985.01390320023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, et al. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1200–1210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, et al. Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1019–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Laethem JL, Hammel P, Mornex F, et al. Adjuvant gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy after curative resection for pancreatic cancer: A randomized EORTC-40013-22012/FFCD-9203/GERCOR phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4450–4456. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeo CJ, Abrams RA, Grochow LB, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: postoperative adjuvant chemo-radiation improves survival. A prospective, single-institution experience. Ann Surg. 1997;225:621–633. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199705000-00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman JM, Swartz MJ, Hsu CC, et al. Analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation after pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: Results of a large, prospectively collected database at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3503–3510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abrams RA, Regine WF, Goodman KA, et al. Consensus panel contouring atlas for the delineation of the clinical target volume in the postoperative treatment of pancreatic cancer. [Accessed June 2, 2013]; http://www.rtog.org/CoreLab/ContouringAtlases/PancreasAtlas.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herman J, Chang D, Goodman K, et al. A phase II multi-institutional study to evaluate gemcitabine and fractionated stereotactic body radiotherapy for unresectable, locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma [Abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(Suppl 15):4045. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodman KA, Regine WF, Dawson LA, et al. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group consensus panel guidelines for the delineation of the clinical target volume in the postoperative treatment of pancreatic head cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83:901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brun R, Rademakers F. ROOT: An object oriented data analysis framework. Nucl Instrum Meth A. 1997;389:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Small W, Jr, Berlin J, Freedman GM, et al. Full-dose gemcitabine with concurrent radiation therapy in patients with nonmetastatic pancreatic cancer: A multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:942–947. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talamonti MS, Small W, Jr, Mulcahy MF, et al. A multi-institutional phase II trial of preoperative full-dose gemcitabine and concurrent radiation for patients with potentially resectable pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:150–158. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapiteijn E, Marijnen CA, Nagtegaal ID, et al. Preoperative radiotherapy combined with total mesorectal excision for resectable rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:638–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones WE, 3rd, Thomas CR, Jr, Herman JM, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria resectable rectal cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:161. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Lamond J, Fowler J, et al. Effect of fractionation in stereotactic body radiation therapy using the linear quadratic model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song CW, Cho LC, Yuan J, et al. Radiobiology of stereotactic body radiation therapy/stereotactic radiosurgery and the linear-quadratic model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87:18–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koong AC, Christofferson E, Le QT, et al. Phase II study to assess the efficacy of conventionally fractionated radiotherapy followed by a stereotactic radiosurgery boost in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:320–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koong AC, Le QT, Ho A, et al. Phase I study of stereotactic radio-surgery in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58:1017–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schellenberg D, Goodman KA, Lee F, et al. Gemcitabine chemotherapy and single-fraction stereotactic body radiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:678–686. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong TS, Ryan DP, Blaszkowsky LS, et al. Phase I study of preoperative short-course chemoradiation with proton beam therapy and capecitabine for resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma of the head. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rwigema JC, Heron DE, Parikh SD, et al. Adjuvant stereotactic body radiotherapy for resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma with close or positive margins. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:70–76. doi: 10.1007/s12029-010-9203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pancreatic tumor cell vaccine (GVAX), low dose cyclophosphamide, fractionated stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), and FOL-FIRINOX chemotherapy in patients with resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. [Accessed May 20, 2013]; http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search/view?cdrid=733883&version=HealthProfessional&protocolsearchid=11740998.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.