Abstract

Background

Data from a school-based study concerning fourth-grade children’s dietary recall accuracy were linked with data from the South Carolina Department of Education (SCDE) through the South Carolina Budget and Control Board Office of Research and Statistics (ORS) to investigate the relationships of children’s school absenteeism with body mass index (BMI), academic achievement, and socioeconomic status (SES).

Methods

Data for all variables were available for 920 fourth-grade children during two school years (2005–2006, 2006–2007). Number of school days absent for each child and eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals (SES measure) were provided to ORS by SCDE. Children’s weight and height were measured by research staff; age/sex specific BMI percentile was calculated and grouped into categories. For academic achievement, Palmetto Achievement Challenge Tests scores were provided by the school district. The associations of absenteeism with BMI, academic achievement, SES, and school year were investigated with logistic binomial models using the modified sandwich variance estimator to adjust for multiple outcomes within schools.

Results

The relationships between absenteeism and each of BMI percentile category and SES were not significant (all coefficient p values > 0.118). The relationship between absenteeism and academic achievement was inversely significant (p value < 0.0001; coefficient = −0.087).

Conclusions

These results support the inverse relationship between absenteeism and academic achievement that was expected and has been found by other researchers. The lack of significant results concerning the relationships between absenteeism and both BMI and SES disagrees with earlier, limited research. More research to investigate these relationships is needed.

Keywords: Child & Adolescent Health, Growth & Development, Program Planning

INTRODUCTION

The implementation of the “No Child Left Behind Act of 2001” created a focus on academic achievement, requiring all public schools to administer state-wide annual standardized tests.1 The “Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004” created a focus on student health, requiring each school district to develop and implement a local wellness policy that promotes student health and reduces childhood obesity.2 Balancing these two legislations encourages schools to take a coordinated approach when developing school policies and school health programs. Recognizing and understanding the associations of student health with school performance is an important first step toward addressing these school policies.

The incidence of childhood obesity has increased dramatically in the United States over the last several decades.3–4 This epidemic has led to increased research on the long-term health implications of obesity in children and adolescents. Overweight and obese children face social discrimination and are at greater risk for health consequences such as type 2 diabetes and adverse levels of cardiovascular disease risk factors.5

The National Coordinating Committee on School Health and Safety implemented a project6–11 to promote awareness of evidence linking health and school performance and to identify knowledge gaps. In one of the six review articles published for that project, Taras and Potts-Datema6 reviewed studies published from 1994–2004 that investigated the association of obesity with academic outcomes among school-aged children. That literature review,6 which was published in 2005, revealed a research gap, particularly concerning the association of childhood obesity and school absenteeism, as only one article (by Schwimmer and colleagues12) had investigated this relationship. Schwimmer and colleagues12 found that severely-obese children and adolescents reported significantly more school days missed than the general student population; however, investigating this association was not their primary aim. To our knowledge, the research gap persists; since the Taras and Potts-Datema review,6 only one published article (by Geier and colleagues13) has directly assessed the relationship between body mass index (BMI) and absenteeism in children. Geier and colleagues13 investigated this relationship among fourth- to sixth-grade children in the inner city of Philadelphia, PA, and found that obese children were absent significantly more than healthy-weight children.

To help fill the research gap, the current article investigated the correlation of children’s absenteeism with BMI, academic achievement, and socioeconomic status (SES). It was hypothesized that absenteeism and BMI would be significantly and positively correlated, and that absenteeism would be significantly and inversely correlated with academic achievement and SES. To conduct analyses for this investigation, data from a school-based study concerning fourth-grade children’s dietary recall accuracy14 were linked with data from the South Carolina Department of Education (SCDE) through the South Carolina Budget and Control Board Office of Research and Statistics (ORS).

METHODS

Subjects

Because the sample for the school-based study concerning fourth-grade children’s dietary recall accuracy has been described in detail elsewhere,14 only a summary is provided here. Data were collected in one school district in Columbia, SC, in 17, 17, and eight elementary schools during the 2004–2005, 2005–2006, and 2006–2007 school years, respectively. Schools were selected based on high participation in school meals from the 28 elementary schools in the district. Written child assent and parental consent were obtained prior to data collection for the dietary recall accuracy study. The assent and consent forms described all components of data collection, including observations of school meals, dietary recall interviews, measurement of weight and height, and that the school district would share children’s achievement test scores with us. For the three school years of data collection, at the schools where data were collected, 83% to 89% of children were eligible for free or reduced-price school meals.

Data for the second and third school years of the dietary recall accuracy study were linked to additional data from SCDE by ORS, which provided aggregate results to study investigators. Permission to link these data sets and to analyze and provide aggregate results was granted to ORS by SCDE. The ORS is a central repository where organizations entrust their health and human service data, yet preserve control at all times. To link across data sources from multiple providers, the ORS developed a series of algorithms using source-specific personal identifiers to create a global unique identifier. Using the global identifier in lieu of personal identifiers enables ORS staff to create and use enhanced views of data across multiple providers while protecting confidentiality.

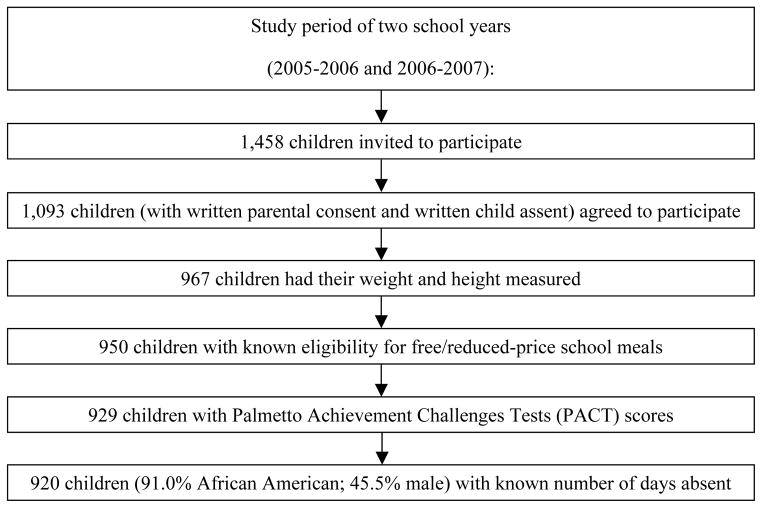

For the current article’s analyses, complete data were available for 920 fourth-grade children. Figure 1 shows the structure of the final sample of children included in analyses.

Figure 1.

Structure of the sample of 920 fourth-grade children analyzed for the current article.

Measures

Absenteeism

Absenteeism was defined as the number of days a child was absent out of the 180 total possible school enrollment days. Absenteeism data were provided at the individual child-level to ORS by SCDE, but only beginning with the 2005–2006 school year.

BMI Percentile Category

BMI (kg/m2) is a recommended measure to identify youth who are obese or overweight.15 It provides an indicator of student health.16–17

In the spring of each of the two school years, research staff used established procedures to measure children’s weight and height.18–19 Measurements were always conducted in the morning after breakfast but before lunch. Weight was measured on digital scales and recorded to the nearest 0.10 pound. Height was measured on portable stadiometers and recorded to the nearest 0.125 inch. Weight and height were measured in duplicate (after repositioning the child). If the two weights and/or heights were not within 0.25 pounds and/or 0.25 inches, respectively, a third measurement was taken. If three measurements were taken, the average of the closest two was used.

Inter-rater reliability was assessed daily for pairs of research staff on a total random sample of 160 of the 920 children (17.4%). For all research staff pairs, intraclass correlations exceeded 0.99 for weight and for height each school year.

Each child’s age at the time of weight and height measurement was calculated by subtracting the child’s date of birth (provided usually by the school but occasionally by a parent) from the date of measurement. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s sex-specific BMI-for-age growth charts for youth ages two to 20 years were used to determine each child’s BMI percentile.21–22 The BMI percentiles were then grouped into the following five descriptive categories based on the June 2007 recommendations of the Expert Committee for the Prevention, Assessment and Treatment of Child and Adolescent Overweight and Obesity:16 underweight (< 5th percentile), healthy weight (≥ 5th and < 85th percentile), overweight (≥ 85th and < 95th percentile), obese (≥ 95th percentile and < 99th percentile) and severely obese (≥ 99th percentile).

Academic Achievement

Academic achievement is most commonly measured using school grades and standardized test scores. Across South Carolina, from 1999–2008, the Palmetto Achievement Challenge Tests (PACT) were administered annually to third- through eighth-grade children in all public schools.22 As grades may be susceptible to differences across assignments, teachers, or schools, standardized tests provide a less variable and more comparable measure of academic achievement.

School staff administered PACT according to state guidelines in May of each school year. The PACT, a set of standardized exams, consisted of four sections which each covered one academic area (English language arts, math, science, social studies). For each academic area, the PACT result was reported as a scale score and as a categorical performance level. For fourth-grade children, for each PACT section, scale scores ranged from 336 to 464, and had a mean of 400.22 The categorical performance levels were “below basic” (child did not meet minimum expectations), “basic” (child met minimum expectations), “proficient” (child met expectations), and “advanced” (child exceeded expectations for student performance based on the curriculum standards).22 For the English language arts, math, science, and social studies scale scores, the “basic” category ranged from 395 to 409, 399 to 415, 397 to 411, and 394 to 412, respectively.23 For the current article’s analyses, the school district provided PACT scale scores and categorical performance levels for each child in the study.

To analyze PACT scores for the current article, a numeric value was assigned to each child’s categorical performance level for each of the four sections, with “below basic” = 1, “basic” = 2, and “proficient/advanced” = 3. (The “proficient” and “advanced” categories were combined for the current article’s analyses because few children in the sample were classified as “advanced”.) Because the scale scores for the “basic” category spanned approximately the same range for each of the four sections, and because pairwise correlations of scaled scores for the four sections were moderately high (ranging from 0.62 to 0.72), a composite score was computed for each child by summing the numeric values for the four sections. Composite scores ranged from 4 to 12, with 4 indicating that a child had a performance level that was “below basic” for all four sections, and 12 indicating that a child had a performance level that was “proficient/advanced” for all four sections.

SES

For school-based studies, SES can be difficult to collect at the individual child level due to parental privacy and confidentiality concerns. As an alternative to collecting family-income data, eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals was used as a proxy measure for the current article’s analyses. Individual level eligibility for free, reduced-price, or full-price school meals was obtained through SCDE and analyzed by ORS staff. Due to a low frequency of children eligible for reduced-price school meals, eligibility for free and reduced-price school meals were combined, giving two markers for SES — “low-SES” (children who were eligible for free or reduced-price school meals) and “high-SES” (children who were not eligible for free or reduced-price school meals and, thus, paid full price).

Children from families with incomes ≤ 130% of the poverty level are eligible for free meals, and those with incomes between 130% and 185% of the poverty level are eligible for reduced-price meals (≤ 40 cents).24 In 2005, for a family of four, 130% and 185% of the poverty level was $25,155 and $35,798, respectively; in 2006, for a family of four, 130% and 185% of the poverty level was $26,000 and $37,000, respectively.25 Therefore, the low-SES marker used for the current article’s analyses included families with approximate income levels of $37,000 or less.

Data Analyses

The associations of absenteeism with BMI, academic achievement, SES, and school year were investigated with logistic binomial models using the modified sandwich variance estimator26 to adjust for multiple outcomes within schools. Initially, models included BMI along with sex and age (in months grouped into quartiles); subsequently, the age- and sex-specific BMI percentile categories were considered in lieu of the three separate initial covariates. The BMI percentiles were grouped into categories recommended by the Expert Committee16 but with one exception – the underweight and healthy weight categories were combined into one category due to low frequency in the underweight category in the sample analyzed for the current article. Additionally, as in the study by Geier and colleagues13 (which to our knowledge is the only study published to date that directly assessed the relationship between BMI and absenteeism in children), for the current article’s analyses, the BMI percentile categories were also collapsed into the following two categories that had been used by Geier and colleagues: < 85th percentile (underweight and healthy weight) and ≥ 85th percentile (overweight, obese, and severely obese). Because results for BMI and BMI percentile category were similar (with the only significant association being between school absenteeism and PACT composite score), for ease of interpretation and presentation, the current article presents results only for BMI percentile categories.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the number and percent of children in the four BMI percentile categories by sex, school year, and SES. Table 2 shows the number of days absent and present, total number of enrollment days, and the percent of days absent by BMI percentile category, PACT composite score, SES, and school year. For the sample of 920 fourth-grade children, there were 4,836 total days absent during the 165,272 total possible school enrollment days.

Table 1.

Number and percent of fourth-grade children in the sample of 920 children for the four BMI percentile categories and overall by sex, school year, and socioeconomic status (SES).

| BMI Percentile Category1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underweight/Healthy Weight | Overweight | Obese | Severely Obese | Overall | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 228 (54%) | 74 (18%) | 73 (17%) | 44 (11%) | 419 (46%) |

| Female | 238 (48%) | 104 (21%) | 103 (21%) | 56 (11%) | 501 (54%) |

| School Year | |||||

| 2005–2006 | 328 (53%) | 121 (20%) | 107 (17%) | 61 (10%) | 617 (67%) |

| 2006–2007 | 138 (46%) | 57 (19%) | 69 (23%) | 39 (13%) | 303 (33%) |

| SES2 | |||||

| Low | 398 (52%) | 144 (19%) | 147 (19%) | 81 (11%) | 770 (84%) |

| High | 68 (45%) | 34 (23%) | 29 (19%) | 19 (13%) | 150 (16%) |

| Total | 466 | 178 | 176 | 100 | 920 |

BMI percentile categories were defined as underweight (< 5th percentile), healthy weight (≥ 5th and < 85th percentile), overweight (≥ 85th and < 95th percentile), obese (≥ 95th percentile and < 99th percentile) and severely obese (≥ 99th percentile). These categorical definitions were based on the Expert Committee’s 2007 recommendation.16 For the current article’s analyses, the underweight and healthy-weight categories were combined due to low frequency in the underweight category.

SES was determined by the individual child’s eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals. “Low” indicates that the child was eligible for free or reduced-price school meals, and “high” indicates that the child was not eligible, and, thus paid full price. To be eligible for free or reduced-price school meals, children’s families must have incomes ≤ 130% or between 130% and 185% of the poverty level, respectively.24

Table 2.

Total number of days absent and present, total enrollment days, and percent of days absent for the sample of 920 fourth-grade children by BMI percentile category, Palmetto Achievement Challenges Tests (PACT) composite score, socioeconomic status (SES), and school year.

| Days Absent | Days Present | Total Enrollment Days | Percent of Days Absent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI Percentile Category1 | ||||

| Underweight/Healthy Weight | 2,517 | 81,173 | 83,690 | 3.0 |

| Overweight | 815 | 31,150 | 31,965 | 2.5 |

| Obese | 931 | 30,718 | 31,649 | 2.9 |

| Severely Obese | 573 | 17,395 | 17,968 | 3.2 |

| PACT Composite Score2 | ||||

| 4 | 1,204 | 26,966 | 28,170 | 4.3 |

| 5 | 827 | 25,754 | 26,581 | 3.1 |

| 6 | 691 | 22,969 | 23,660 | 2.9 |

| 7 | 560 | 22,635 | 23,195 | 2.4 |

| 8 | 420 | 16,305 | 16,725 | 2.5 |

| 9 | 487 | 17,137 | 17,624 | 2.8 |

| 10 | 320 | 13,714 | 14,034 | 2.3 |

| 11 | 203 | 8,963 | 9,166 | 2.2 |

| 12 | 124 | 5,993 | 6,117 | 2.0 |

| SES3 | ||||

| Low | 4,201 | 134,090 | 138,291 | 3.0 |

| High | 635 | 26,346 | 26,981 | 2.4 |

| School Year | ||||

| 2005–2006 | 3,146 | 107,757 | 110,903 | 2.8 |

| 2006–2007 | 1,690 | 52,679 | 54,369 | 3.1 |

BMI percentile categories were defined as underweight (< 5th percentile), healthy weight (≥ 5th and < 85th percentile), overweight (≥ 85th and < 95th percentile), obese (≥ 95th percentile and < 99th percentile) and severely obese (≥ 99th percentile) based on the Expert Committee’s 2007 recommendation.16 For the current article’s analyses, the underweight and healthy-weight categories were combined due to low frequency in the underweight category.

PACT composite score is the summation of the numeric value of each child’s categorical performance level for each of the four sections, with “below basic” = 1, “basic” = 2, and “proficient/advanced” = 3.22 (For the current article’s analyses, the “proficient” and “advanced” categories were combined because few children were classified as “advanced”.) These composite scores range from 4 to 12, with 4 indicating that a child had a performance level that was “below basic” for all four sections, and 12 indicating that a child had a performance level that was “proficient/advanced” for all four sections.

SES is determined by the individual child’s eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals. “Low” indicates that the child was eligible for free or reduced-price school meals and “high” indicates that the child was not eligible. To be eligible for free or reduced-price school meals, families must have incomes ≤ 130% or between 130% and 185% of the poverty level, respectively.24

In the logistic binomial regression models, absenteeism was not significantly related to any of the four BMI percentile categories (all three coefficient p values > 0.118) nor to BMI percentiles when collapsed into only two categories (coefficient p value = 0.4334). In the logistic binomial regression models, the relationship between absenteeism and PACT composite score was inversely significant (p value < 0.0001; coefficient = −0.087). As shown in Table 2, children with lower PACT composite scores were absent more often than children with higher PACT composite scores. Specifically, children with the highest PACT composite score of 12 were less likely to be absent on a given enrollment day at 2.0% versus 4.3% for children with the lowest PACT composite score of 4 (see Table 2). Logistic binomial regression models did not indicate a significant relationship between absenteeism and SES (coefficient p value = 0.352), or between absenteeism and school year (coefficient p value = 0.195).

DISCUSSION

The current article’s analyses failed to find a significant relationship between fourth-grade children’s BMI and absenteeism. This is in contrast to findings from the two studies12–13 mentioned in the Introduction. Schwimmer and colleagues12 found that in a sample of obese youth (ages five to 18 years) who had been referred to a specialist for evaluation of obesity compared to a sample of healthy youth (ages five to 18 years) from private practice pediatrician offices and community health clinics, obese youth were absent more than healthy youth (p < 0.001). During the month prior to evaluation, obese youth were absent a mean (± standard deviation) of 4.2 ± 7.7 days and healthy youth were absent a mean of 0.7 ± 1.7 days. However, as the objective of Schwimmer and colleagues’ study was to examine health-related quality of life measures in obese youth, the primary aim did not concern the association between obesity and absenteeism. Geier and colleagues13 found that in a sample of fourth- to sixth-grade children, obese children (BMI ≥ 95th percentile) were absent more than healthy-weight children (BMI ≥ 5th and < 85th percentile) (p < 0.05) after controlling for school. During the 180-day academic year, healthy-weight children were absent a mean of 10.1 ± 10.5 days and obese children were absent a mean of 12.2 ± 11.7 days.

In addition to being absent because of BMI-related illness, research has shown that overweight and obese children are more likely to be bullied or teased than their normal-weight peers;27 this could contribute to missed school days.6 Also, it is possible that obese children might be absent from school because they are embarrassed to participate in physical activities.6 With these two points in mind, it is somewhat surprising that the current article’s analyses of children’s BMI percentile category and absenteeism did not find a significant relationship.

As expected, the current article’s analyses found that absenteeism was inversely correlated with academic achievement. It is logical that children who are more often absent from school are not present to learn information and skills needed to perform well on academic achievement tests such as South Carolina’s PACT. A significant relationship between absenteeism and academic achievement has been found in some studies28–29 but not others.30 Sigfúsdóttir and colleagues28 analyzed cross-sectional survey data from 5,810 Icelandic youth ages 14 to 15 years; although absenteeism was treated as a control variable in the main analyses, initial bivariate correlations between key variables showed an inverse correlation of modest strength (r = −0.26) between self-reported grades and self-reported frequency of skipping classes. Silverstein and colleagues29 conducted a case-control study of 92 asthmatic children and age- and sex-matched non-asthmatic control subjects; in multivariable analysis of grade point average, absenteeism was significantly associated with grade point average, but asthma was not. Gutstadt and colleagues30 documented performance on standardized academic achievement tests in a group of 99 children (ages 9 to 17 years) with chronic asthma; results showed that school absenteeism was not associated with academic performance.

Surprisingly, the current article’s analyses found that absenteeism and SES were not significantly related. Geier and colleagues13 were unable to assess the effect of SES at the individual level; they suggested that future studies examine this variable to further understand the relationship between children’s BMI and absenteeism. Although the current article’s analyses did not find a significant relationship between absenteeism and SES, there was extremely low variability in the two SES categories, which may be hiding a true relationship. Also, eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals is a general rather than specific measure of SES, despite the strength of being at the individual level.

Limitations and Strengths

Limitations of the data analyzed for the current article include the fact that the study was not designed to investigate the relationship of children’s absenteeism with BMI, academic achievement, and SES. Data collected were cross-sectional, whereas longitudinal data would provide a better understanding of these relationships. Also, the sample was fairly homogenous with only fourth-grade children who were primarily African American and from one school district. Although this limits generalizability, for each school year, the race/sex composition of children who agreed to participate was similar to that of children who were invited, which suggests that the sample was representative of the population. The fact that schools were selected based on high participation in school meals could have decreased the mean SES of the sample, and led to low variability in the two SES categories.

Strengths of the current article’s analyses include the use of child-level (rather than school-level) eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals and PACT composite scores. Also, BMIs were from measured weights and heights rather than self- or parental-reported information. The time of day and time of year of weight/height measurements were consistent for the school years of data collection, and inter-rater reliability was assessed daily. The current article’s analyses provided a cost-efficient opportunity to investigate the relationship of absenteeism with BMI, academic achievement, and SES.

Conclusion

The current article’s analyses support the inverse relationship between children’s absenteeism and academic achievement that was expected and has been found by other researchers. However, these analyses fail to support the positive relationship between absenteeism and BMI and the inverse relationship between absenteeism and SES that was expected and has been found by other researchers. Studies designed specifically for the purpose of investigating these relationships and collecting actual, individual-level data are needed to further close these gaps in the literature.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL HEALTH

More research is needed to further investigate the relationship of children’s school absenteeism with BMI, academic achievement, and SES. Enhanced collaboration among schools, districts, state agencies, and researchers could facilitate cost-efficient opportunities for such research. For example, as part of local wellness policies, schools have the opportunity to assist researchers through the implementation of weight and height measurements that follow established procedures. Time of day and school year for measurements should be standardized to compare children’s BMI across school years, and measurers should be properly trained and regularly participate in inter-rater reliability.31 According to the “2010 Shape of the Nation Report”,32 13 of the 50 states in the U.S. require schools to measure BMI and/or weight and height for each student either in specific grades (such as fifth, eighth, and ninth) or in every grade from kindergarten through twelfth. By using weight and height measurements already collected in schools, and linking this with information concerning absenteeism, academic achievement and eligibility for free/reduced-price school meals already collected by districts, researchers can more easily design and conduct cost-effective and longitudinal studies to add to the literature base.

To our knowledge, no other state has a data warehouse like South Carolina’s ORS. Therefore, South Carolina has a unique opportunity to use ORS as an alternate source of data. However, ORS currently does not have access to weight and height measurement data. As South Carolina requires schools to collect body composition, students’ BMI, or height and weight once per year in the fifth, eighth, and ninth grades,32 the SCDE may obtain this data and share it with ORS, thereby enabling researchers to more easily investigate student health and academic achievement relationships among South Carolina children.

Human Subjects Approval Statement

The project was approved by the University of South Carolina’s institutional review board for human subjects.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by two grants (R01 HL074358 and R21 HL088617 with SD Baxter as Principal Investigator) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors appreciate the cooperation of children, faculty, and staff of elementary schools, and staff of Student Nutrition Services, of the Richland One School District (Columbia, SC).

Amy F. Joye, MS, RD was Project Director for grant R01 HL074358 until she suffered severe brain damage due to a medical tragedy at age 36. The Amy Joye Memorial Research Award has been established through the American Dietetic Association Foundation to award nutrition research grants in Amy’s memory.

Footnotes

The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Suzanne Domel Baxter, Email: sbaxter@mailbox.sc.edu, Research Professor, University of South Carolina, Institute for Families in Society, 1600 Hampton St. Ste. 507, Columbia, SC 29208, Phone: 803-777-1824 x 12, Fax: 803-777-1120.

Julie A. Royer, Email: Julie.Royer@ors.sc.gov, royerj@mailbox.sc.edu, Statistician, Office of Research and Statistics, SC Budget and Control Board, 1919 Blanding Street, Columbia, SC 29201, Phone: 803-898-9701, Fax: 803-898-9972 & Research Associate, University of South Carolina, Institute for Families in Society, 1600 Hampton St. Ste. 507, Columbia, SC 29208, Phone: 803-777-1824 x 22, Fax: 803-777-1120.

James W. Hardin, Email: jhardin@mailbox.sc.edu, Research Professor, University of South Carolina, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics & Institute for Families in Society, 1600 Hampton St. Ste. 507, Columbia, SC 29208, Phone: 803-777-1824 x 23, Fax: 803-777-1120.

Caroline H. Guinn, Email: cguinn@mailbox.sc.edu, Research Dietitian, University of South Carolina, Institute for Families in Society, 1600 Hampton St. Ste. 507, Columbia, SC 29208, Phone: 803-777-1824 x 24, Fax: 803-777-1120.

Christina M. Devlin, Email: cdevlin@mailbox.sc.edu, Research Dietitian, University of South Carolina, Institute for Families in Society, 1600 Hampton St. Ste. 507, Columbia, SC 29208, Phone: 803-777-1824 x 12, Fax: 803-777-1120.

References

- 1.No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. [Accessed July 24, 2010];Pub Law no 107–110, 115 stat 1425. 2002 Available at: http://www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02/index.html.

- 2.Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004. [Accessed July 24, 2010];Pub Law no 108–265, 118 stat 729. 2004 Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Governance/Legislation/Historical/PL_108-265.pdf.

- 3.Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2000. J Amer Med Assoc. 2002;288:1728–1732. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. J Amer Med Assoc. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed July 24, 2010];The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/topics/obesity/

- 6.Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Obesity and student performance at school. J Sch Health. 2005;75(8):291–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Childhood asthma and student performance at school. J Sch Health. 2005;75(8):296–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Sleep and student performance at school. J Sch Health. 2005;75(7):248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taras H, Potts-Datema W. Chronic health conditions and student performance at school. J Sch Health. 2005;75(7):255–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taras H. Nutrition and student performance at school. J Sch Health. 2005;75(6):199–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taras H. Physical activity and student performance at school. J Sch Health. 2005;75(6):214–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. J Amer Med Assoc. 2003;289:1812–1819. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geier AB, Foster GD, Womble LG, McLaughlin J, Borradaile KE, Nachmani J, Sherman S, Kumanyika S, Shults J. The relationship between relative weight and school attendance among elementary schoolchildren. Obesity. 2007;15:2157–2161. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baxter SD, Hardin JW, Guinn CH, Royer JA, Mackelprang AJ, Smith AF. Fourth-grade children’s dietary recall accuracy is influenced by retention interval (target period and interview time) J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:846–856. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 24, 2010];About BMI for children and teens. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html.

- 16.Barlow SE, Committee TE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: Summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120:S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002;360:473–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maternal and Child Health Bureau. [Accessed July 24, 2010];Accurately weighing & measuring: Technique. Available at: http://depts.washington.edu/growth/module5/text/intro.htm.

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 24, 2010];BMI percentile calculator for child and teen: English version. Available at: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/dnpabmi/Calculator.aspx.

- 21.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. 2000 CDC Growth Charts for the United States: Methods and Development. National Center for Health Statistics; 2002. [Accessed July 24, 2010]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_11/sr11_246.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.South Carolina Department of Education. [Accessed July 24, 2010];Palmetto Achievement Challenge Tests (PACT) 2008 Available at: http://ed.sc.gov/agency/Accountability/Assessment/old/assessment/PACT/

- 23. [Accessed July 24, 2010];South Carolina Department of Education - PACT cut scores. 2008 Available at: http://ed.sc.gov/agency/Accountability/Assessment/old/assessment/PACT/cutscores.html.

- 24.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. [Accessed July 24, 2010];Eligibility Manual for School Meals. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/Governance/notices/iegs/EligibilityManual.pdf.

- 25.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed July 24, 2010];Prior HHS Poverty Guidelines and Federal Register References. Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/figures-fed-reg.shtml.

- 26.Hardin JW. The sandwich estimate of variance. In: Fomby T, Carter Hill R, editors. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Misspecified Models: Twenty Years Later, Advances in Econometrics. New York: Elsevier; 2003. pp. 305–325. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssen I, Craig WM, Boyce WF, Pickett W. Associations between overweight and obesity with bullying behaviors in school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1187–1194. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigfúsdóttir ID, Kristjansson AL, Allegrante JP. Health behaviour and academic achievement in Icelandic school children. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:70–80. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silverstein MD, Mair JE, Katuskic SK, Wollan PC, O’Connell EJ, Yunginger JW. School attendance and school performance: A population-based study of children with asthma. J Pediatr. 2001;139:278–283. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.115573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutstadt LB, Gillette JW, Mrazek DA, Fukuhara JT, LaBrecque JF, Strunk RC. Determinants of school performance in children with chronic asthma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1989;143:471–475. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150160101020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guinn CH, Baxter SD, Litaker MS, Thompson WO. Prevalence of overweight and at risk of overweight in fourth-grade children across five school-based studies conducted during four school years. [Accessed July 24, 2010];J Child Nutr Manag. 2007 :31. Available at: http://docs.schoolnutrition.org/newsroom/jcnm/07spring/guinn/index.asp. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.National Association for Sport and Physical Education & American Heart Association. 2010 Shape of the Nation Report: Status of Physical Education in the USA. Reston, VA: National Association for Sport and Physical Education; [Accessed July 24, 2010]. Available at: www.naspeinfo.org/shapeofthenation. [Google Scholar]