Abstract

Background

Temporal trends in incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) in the United States have been reported only in regional populations. The Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system encompasses a national network of clinical care facilities. The aim of this study was to identify temporal trends in the incidence and prevalence of CD and UC among VA users using national VA data sets.

Methods

Veterans with CD and UC were identified during fiscal years 1998 to 2009 in the national VA outpatient and inpatient files. Incident and prevalent cases were identified by diagnosis code, and age-standardized and gender-standardized annual prevalence and incidence rates were estimated using the VA 1998 population as the standard population.

Results

The total of unique incident cases were 16,842 and 26,272 for CD and UC, respectively; 94% were men. The average annual age-standardized and gender-standardized incidence rate of CD was 33 per 100,000 VA users (range, 27–40), whereas the average for UC was 50 per 100,000 VA users (range, 36–65). In 2009, the age-standardized and gender-standardized point prevalence rate of CD was 287 per 100,000 VA users, whereas the point prevalence of UC was 413 per 100,000 VA users.

Conclusions

Prevalence of CD and UC increased 2-fold to 3-fold among VA users between 1998 and 2009. The incidence of UC decreased among VA users from 1998 to 2004 but has remained stable from 2005 to 2009. The incidence of CD has remained stable during the observed time period.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, epidemiology

The incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), collectively referred to as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), vary considerably worldwide. The highest incidence and prevalence rates have been reported in North America and Europe, with incidence rates as high as 20.2 per 100,000 for CD and 19.5 per 100,000 for UC.1–3 The prevalence of IBD also varies within the United States and Europe, with lower prevalence rates for both CD and UC in the southern regions compared with the northern regions.4–6

In the United States, temporal trends in the incidence and prevalence of IBD have been reported in only a few regional populations. In Olmsted County, Minnesota, the incidence of both CD and UC increased between 1940 and 1970 from 3.1 to 9.4 per 100,000 and from 2.3 to 6.5 per 100,000, respectively, but remained stable between 1970 and 2000.7 However, the incidence of both CD and UC rose significantly from 1996 to 2006 in a study of ethnically diverse pediatric IBD in a managed care organization in Northern California.8 In Olmsted County, the prevalence of CD has increased from 1991 to 2001 by 31%; however, the prevalence of UC of 214 per 100,000 was reported to remain stable.7 Conversely, the prevalence of both CD and UC were reported to increase in the Northern California study between 1996 and 2002.9 Differences in the temporal trends of IBD may be related to geographic differences or ethnic diversity. There have been no studies reporting temporal incidence and prevalence trends of IBD in a national cohort in the United States.

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is the largest integrated health care system in the United States and has more than 120 facilities throughout the country. As of September 2008, there were an estimated 23,440,000 living U.S. veterans, of whom 8,493,700 received VA benefits in fiscal year 2008.10 Only a few studies have examined the epidemiology of IBD among the U.S. veterans. These studies have focused on hospitalized veterans who may not represent the greater veteran population with IBD. One study reported a decrease in IBD-related hospitalization rates in the VA from 1985 to 2006 among Caucasians, but an increase in IBD-related hospitalizations among most groups of non-Caucasians in the same time period.11 In addition, the age distribution of IBD-related hospitalization shifted toward older age groups in recent years, which was more pronounced among VA users with UC than CD.11 The aim of this study was to describe the temporal trends in the incidence and prevalence of IBD among a nationally distributed cohort of users of the VA health care system. Examining temporal trends may give clues about risk factors and are also important in quantifying the burden of disease among this unique population to assess their medical needs and disease outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

We used data from the national VA administrative data sets to estimate the incidence and prevalence of IBD among VA users. We identified veterans with IBD during fiscal years 1998 to 2009 (October 1997–September 2009) in the national VA administrative data sets, specifically the Patient Treatment Files and the Outpatient Care Files. The Patient Treatment Files and the Outpatient Care Files contain individual-level data from inpatient and outpatient encounters, respectively, from all VA facilities with information on demographics (age, gender, ethnicity), encounters or visits (date, frequency), diagnosis codes (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]), and medical and surgical procedure codes (Current Procedural Terminology).

The Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center data include the total number of unique veterans using the VA health care system each fiscal year, herein described as VA users. The Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center does not include data on medical care received outside the VA system. For each fiscal year, unique patients were identified from inpatient, inpatient observation beds, extended care, outpatient, and pharmacy encounters in all VA facilities. The Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center data were used in this study to determine the total number of VA users in each fiscal year stratified by specified age categories and gender. Total VA users based on the described definition increased by 65% during the study period from 3,270,650 in 1998 to 5,387,043 in 2009.

Case Identification

VA users with IBD were identified by ICD-9 diagnosis codes for CD (555.x) or UC (556.x), which were recorded on at least 2 VA encounters with at least 1 code from an outpatient encounter as our group has previously described and validated in VA data sets with a positive predictive value of 86% for UC.12 ICD-9 codes for CD using VA data have also been validated to have a positive predictive value of 88%.13 VA users with ICD-9 codes for both CD and UC were classified as indeterminate colitis (IC). Prevalent cases of IBD for each fiscal year were identified by the presence of any VA encounter in the Outpatient Care Files and the Patient Treatment Files during that fiscal year irrespective of diagnoses recorded in preceding years back to October 1997. Incident cases of IBD for each fiscal year were identified by the first appearance of an ICD-9 code for CD or UC in any patient with no previous diagnosis code for either CD or UC in preceding years back to October 1997 and at least 2 years of VA encounters before the IBD index date.

Statistical Analyses

The incidence rates were calculated annually for newly identified IBD cases. The numerator for these rates was the total number of newly identified cases in a given fiscal year based on the presence of ICD-9 code for CD or UC in that year among patients with no previous diagnosis code for CD or UC as described in the Case Identification section. The denominator for incidence rates served as an estimate of the at-risk population of VA users in each fiscal year and was considered as the total number of all VA users in each fiscal year with at least 1 encounter in the VA health care system (Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center data) excluding those with a previous diagnosis code for either CD or UC.

The prevalence was calculated as proportions for CD, UC, or IC identified in each fiscal year of the study and the entire study period (1998–2009). The numerator was defined as the total number of IBD cases during each fiscal year by the presence of an ICD- 9 code for CD or UC as described in the Case Identification section. The denominator was the total number of VA users irrespective of present or past diagnoses in each fiscal year as determined from the Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center data.

The calculated incidence and prevalence rates were subsequently standardized for possible temporal changes in the age and gender distribution of the underlying populations by applying the direct standardization method using the 1998 VA population in Veterans Health Administration Support Service Center as the standard population. The rates were expressed per 100,000 VA users. Age-specific incidence rates were categorized in the age groups of younger than 25, 25 to 34, 35 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64, 65 to 74, 75 to 84, and older than 85 years at IBD index and calculated for each fiscal year. Incidence rates are presented graphically as a central moving average including 1 year before and after each data point (1999–2008). Incidence rate ratios for CD or UC were calculated for the each year during the entire time period (fiscal year 1998–2009) using a Poisson model adjusting for gender and age at IBD index.

Ethical Considerations

The institutional review boards of the Baylor College of Medicine and the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, Texas, approved this study.

RESULTS

A total of 45,510 incident cases of IBD were identified among VA users during fiscal years 1998 to 2009, consisting of 16,842 cases of CD (38%), 26,272 cases of UC (57%), and 2,396 cases of IC (5%). Of incident IBD cases, 94% were men and the ethnic distribution was 72% Caucasian, 8% African American, 3% Hispanic, 2% Other, and 16% in whom race could not be classified (Table 1). There was a predominance of UC over CD among incident cases in all ethnic groups (57% UC versus 37% CD, P < 0.01) (incidence rate ratios, 1.57; 95% confidence interval, 1.51–1.63), with the most dramatic difference in Hispanics (67% UC versus 28 % CD, P < 0.001). The predominance of UC over CD among incident IBD cases was seen in most age groups, except among those who were younger than 25 years at IBD index were more likely to have CD than UC (50% CD versus 42% UC).

TABLE 1.

Demographic Data of Incident and Prevalent IBD Cases in VA Users, 1998 to 2009

| Incident Cases | Prevalent Cases | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC | CD | IC | UC | CD | IC | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | P | n | % | n | % | n | % | P | |

| Total patients | 26,272 | 16,842 | 2396 | 32,736 | 21,288 | 4092 | ||||||||

| Race | ||||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 18,816 | 71.6 | 12,086 | 71.8 | 1778 | 74.2 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| African American | 1962 | 7.5 | 1374 | 8.1 | 272 | 11.4 | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 811 | 3.0 | 359 | 2.1 | 77 | 3.2 | ||||||||

| Other | 412 | 1.6 | 230 | 1.4 | 49 | 2.0 | ||||||||

| Unknown | 4271 | 16.3 | 2793 | 16.6 | 220 | 9.2 | ||||||||

| Gender | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| Male | 24,857 | 94.6 | 15,552 | 92.3 | 2215 | 92.4 | 30,997 | 94.7 | 19,647 | 92.3 | 3801 | 92.9 | ||

| Female | 1415 | 5.4 | 1290 | 7.7 | 181 | 7.6 | 1739 | 5.3 | 1641 | 7.7 | 291 | 7.1 | ||

| Age at IBD index, yr | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||||||

| <25 | 420 | 1.6 | 482 | 2.9 | 96 | 4.0 | 463 | 1.4 | 553 | 2.6 | 130 | 3.2 | ||

| 25–34 | 1300 | 4.9 | 1264 | 7.5 | 220 | 9.2 | 1748 | 5.3 | 1691 | 7.9 | 401 | 9.8 | ||

| 35–44 | 1886 | 7.2 | 1577 | 9.4 | 279 | 11.6 | 2586 | 7.9 | 2273 | 10.7 | 587 | 14.3 | ||

| 45–54 | 3791 | 14.4 | 3029 | 18.0 | 508 | 21.2 | 5223 | 16.0 | 4293 | 20.2 | 933 | 22.8 | ||

| 55–64 | 6734 | 25.6 | 4201 | 24.9 | 638 | 26.7 | 7839 | 24.0 | 4916 | 23.1 | 938 | 22.9 | ||

| 65–74 | 6863 | 26.2 | 3653 | 21.7 | 446 | 18.6 | 8624 | 26.3 | 4494 | 21.1 | 764 | 18.7 | ||

| 75–84 | 4891 | 18.6 | 2409 | 14.3 | 201 | 8.4 | 5830 | 17.8 | 2820 | 13.2 | 327 | 8.0 | ||

| 85+ | 387 | 1.5 | 227 | 1.3 | 8 | 0.3 | 423 | 1.3 | 248 | 1.2 | 12 | 0.3 | ||

A total of 58,116 unique prevalent IBD cases were identified during the study period, with 21,288 cases of CD (37%), 32,736 cases of UC (56%), and 4.092 cases of IC (7%). The demographic features were not different from those of incident cases. Among the prevalent cases, greater than 90% were men, and 50% were between the ages of 55 and 74 years at IBD index.

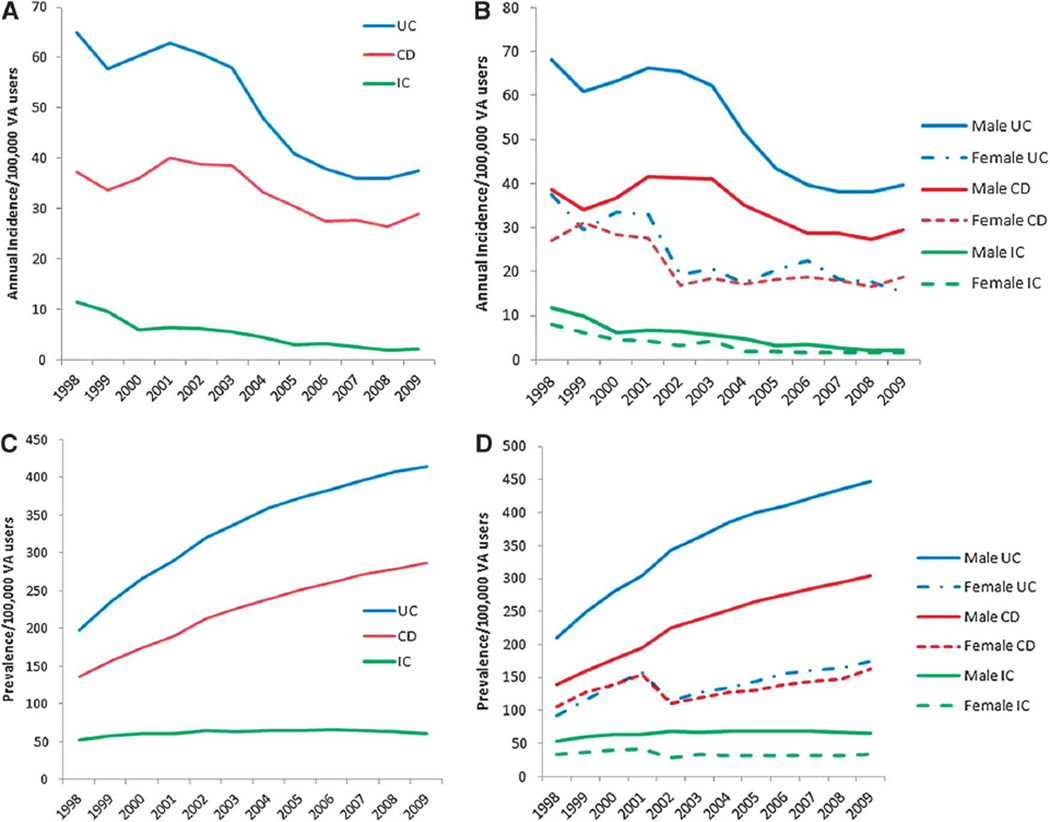

Standardized Incidence Rates

Annual age-standardized and gender-standardized incidence rates of CD varied from a low of 26 per 100,000 in 2008 to a high of 40 per 100,000 VA users in 2001, which remained stable during the study period (Fig. 1A). Standardized incidence rates of UC varied from a low of 36 per 100,000 in 2008 to a high of 65 per 100,000 VA users in 1998. There was a downward trend of UC incidence from 1998 to 2004, with a stable incidence from 2005 to 2009. Crude and standardized incidence rates were generally similar in magnitude and temporal trends for both CD and UC. The standardized incidence rates of IBD were lower in female patients compared with male patients (incidence rate ratios, 0.51; 95% confidence interval, 0.49–0.53). The CD incidence rates in women ranged from 16 to 31 per 100,000 VA users compared with 27 to 42 per 100,000 VA users in men (Fig. 1B). The UC incidence rates in female patients ranged from 15 to 38 per 100,000 VA users, which were lower compared with 38 to 69 per 100,000 VA users in male patients.

FIGURE 1.

A, Age-standardized and gender-standardized incidence of IBD among VA users. There were a total of 26,272 incident UC cases, 16,842 incident CD cases, and 2396 incident IC cases. B, Gender-specific incidence of IBD among VA users. There were a total of 24,857 incident male UC cases, 1415 incident female UC cases, 15,552 incident male CD cases, 1290 incident female CD cases, 2215 incident male IC cases, and 181 incident female IC cases. C, Age-standardized and gender-standardized prevalence of IBD among VA users. There were a total of 32,736 prevalent UC cases, 21,288 prevalent CD cases, and 4092 prevalent IC cases. D, Gender-specific prevalence of IBD among VA users There were a total of 30,997 prevalent male UC cases, 1739 prevalent female UC cases, 19,647 prevalent male CD cases, 1641 prevalent female CD cases, 3808 prevalent male IC cases, and 291 prevalent female IC cases.

Standardized Prevalence Rates

Annual age-standardized and gender-standardized prevalence rates of CD increased progressively more than 2-fold from 136 per 100,000 in 1998 to 287 per 100,000 VA users in 2009. Standardized prevalence rates of UC increased steadily by almost 2.5-fold from 198 per 100,000 VA users in 1998 to 413 per 100,000 VA users in 2009 (Fig. 1C). The CD prevalence rates were lower in female patients compared with male patients, ranging from 106 to 163 per 100,000 VA users and 139 to 304 per 100,000 VA users, respectively (Fig. 1D). Likewise, the UC prevalence rates were lower in women compared with men, ranging from 92 to 174 per 100,000 VA users and 209 to 447 per 100,000 VA users, respectively.

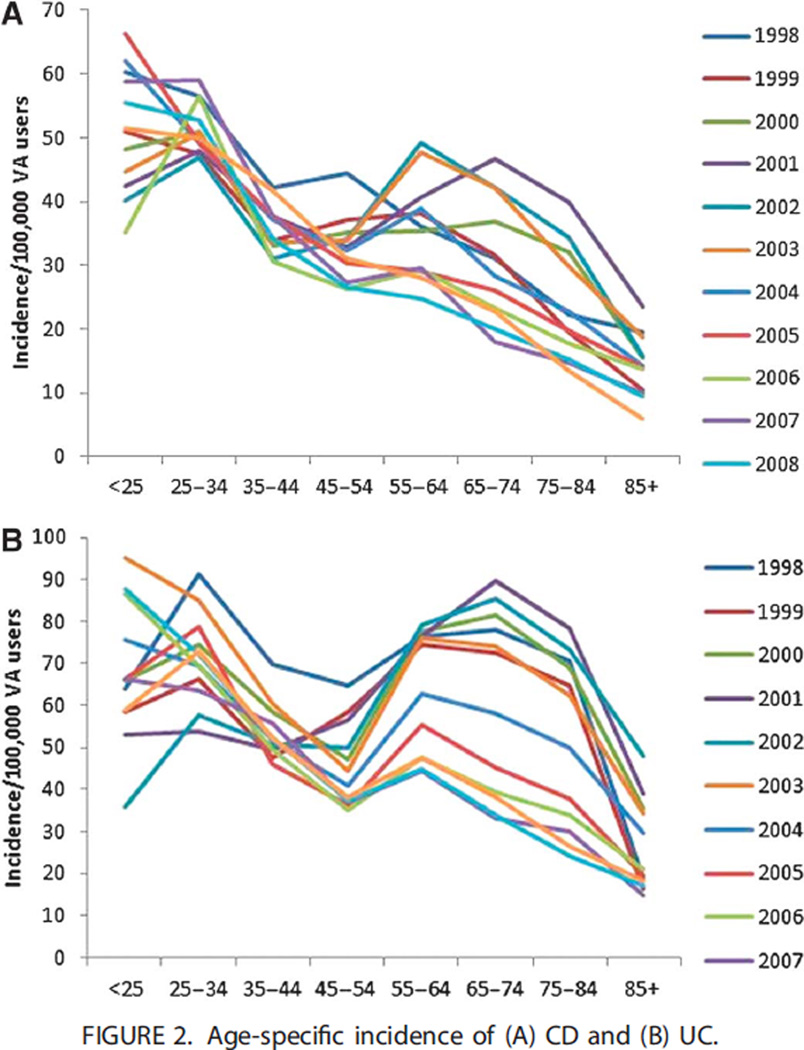

Age-Specific Incidence of CD and UC

Age-specific CD rates demonstrated a bimodal age distribution (Fig. 2A). The peak incidence was 60 per 100,000 VA users in the 25 to 34 years age group. There was a second smaller incidence peak of 36 per 100,000 VA users in the 55 to 64 years age group. The bimodal age distribution was observed in all years except 1998, 2005, 2008, and 2009.

FIGURE 2.

Age-specific incidence of (A) CD and (B) UC.

The UC incidence rates demonstrated a more pronounced bimodal age distribution compared with CD across the entire study period, 1998 to 2009 (Fig. 2B). The first incidence peak was observed in the 25 to 34 years age group at 68 per 100,000 VA users, and the second larger incidence peak was observed in the 55 to 64 years age group at 63 per 100,000 VA users. The bimodal age distribution was observed in every year reported.

DISCUSSION

We examined the temporal trends in the IBD incidence and prevalence in a national cohort of VA users in the 12-year period between 1998 and 2009. Among a total of 45,512 incident cases of IBD, the incidence of CD remained stable, and the incidence of UC decreased from 1998 to 2004 and remained stable from 2005 to 2009. We have observed a progressive increase of more than 2-fold in the IBD prevalence during the same time period. The incidence and prevalence of UC were higher than those of CD among VA users. The incidence and prevalence of IBD were higher among male patients than among female patients. A bimodal age distribution was identified in both UC and CD but was more prominent in UC.

Our study represents the first report of the descriptive epidemiology of IBD using the national VA data sets, including both inpatient and outpatient encounters. The veteran population differs from the general U.S. population in several aspects, including a male predominance and exposure to combat conditions. The effect of these differences on the incidence and prevalence of IBD is unclear.

The incidence and prevalence rates observed in our study were generally higher than those reported in previous studies. Population-based studies have reported the annual incidence rates of CD ranging from 0.5 per 100,000 in Japan to 20.2 per 100,000 in Canada and the prevalence rates ranging from 5.8 per 100,000 in Japan to 319 per 100,000 in Canada.2,14 The annual incidence rates of UC ranged from 0.3 per 100,000 in South Korea to 19.5 per 100,000 in Canada, and the prevalence rates ranged from 7.6 per 100,000 in South Korea to 294 per 100,000 in Denmark.15,16 Studies from the United States have reported a range of incidence rates from 6.3 to 7.9 per 100,000 for CD and from 10.1 to 12 per 100,000 for UC. The incidence and prevalence rates in our study were among VA users who have ongoing care at a VA facility, and therefore, our rates are higher than those in population-based studies. Although the incidence and prevalence rates of IBD in our national VA cohort study cannot be directly compared with those of population-based studies, the temporal and epidemiological trends of VA users highlight a growing population with IBD that require further study.

With the exception of this study, there have been no estimates of temporal trends in IBD incidence or prevalence in a national cohort in the United States. In the predominantly Caucasian Olmsted County, Minnesota, the annual incidence rates of both CD and UC increased between 1940 and 1970 from 3.1 to 9.4 per 100,000 and from 2.3 to 6.5 per 100,000, respectively. From 1970 to 2000, the incidence rates of both CD and UC in the same population remained stable.7 In the same population, agestandardized and gender-standardized prevalence rate for CD increased 31% from 133 to 174 per 100,000 between 1991 and 2000, whereas the age-standardized and gender-standardized prevalence rate for UC remained stable during the same time period, 214 per 100,000.7 In an ethnically diverse population from a managed care organization in Northern California from 1996 to 2002, the average annual incidence rates of CD and UC were reported to be 6.3 and 12 per 100,000 persons, respectively.9 In the same study, the point prevalence rates of both CD and UC increased between 1996 and 2002, from 96.3 to 100.3 per 100,000 for CD and from 155.8 to 205.8 per 100,000 for UC.9 The temporal incidence trends of pediatric IBD in this population showed an increase from 2.2 to 4.3 per 100,000 for CD and from 1.8 to 4.9 per 100,000 for UC during this time period.8 Similarly, a population- based study of pediatric IBD in Wisconsin from 2000 to 2001 reported the incidence rate to be 4.56 per 100,000 for CD and 2.14 per 100,000 for UC.17 Period prevalence estimates of IBD using national administrative data from 1999 to 2001 were 129 per 100,000 for CD and 191 per 100,000 for UC.18 In a second study of national health claims databases, the period prevalence from 2003 to 2004 was 201 per 100,000 for CD, 238 per 100,000 for UC, and 444 per 100,000 for IBD overall.5

We observed a bimodal age-specific incidence in UC for ages 25 to 34 years and 55 to 64 years, but only a minimal second peak in CD. This age-related variation in incidence has been similarly reported in Canada, Northern California, and Minnesota.6,7,9 In studies from Minnesota and Canada, the bimodal peak in UC was more prominent in male patients compared with female patients with UC, which may explain why the bimodal peak in UC in our study is more dramatic than reported in other studies. With regard to CD, the Minnesota study reported an incidence peak in 20 to 29 years age group, Canada was 30 to 39 years age group, and in our study, 25 to 34 years age group with a trend toward decreasing incidence with increasing age.

This study has several strengths. We used the VA administrative data sets to identify the incidence and prevalence of IBD using both inpatient and outpatient encounters, whereas previous epidemiological studies of IBD in the VA included only inpatient encounters. The VA administrative data sets contain national data and therefore provide a basis to determine the overall burden of IBD among all VA users. The VA consists of an ethnically heterogeneous population, which has not been investigated in regard to the epidemiology of IBD at a national level.

This study also has limitations inherent to an administrative data set. Our definitions are based on the accuracy and completeness of ICD-9 coding. We used a diagnostic algorithm of ICD-9 codes used previously and validated for IBD within the VA with positive predictive value 86% for UC and 88% for CD, similar to that derived in other administrative databases.12,13,17 Pharmacy data were not available as part of the case definitions. The VA IBD index date may not coincide with IBD onset or first diagnosis date. However, in the context of this study, it estimates the incident burden of IBD among VA users. Our study is based on a national health care system but is not population based. Our rates reflect the incidence and prevalence among VA users with at least 1 health care encounter in the VA for each fiscal year that may explain the higher incidence and prevalence rates than those reported in population-based studies and, therefore, cannot be directly compared. Changes in the incidence and prevalence of IBD may therefore reflect either true change in the occurrence of IBD or temporal changes in the size and composition of the VA population, including exposure to combat conditions, infection, or chemical exposure. This will require further study. Temporal trends could also reflect changes in practice patterns or diagnostic testing. Last, our results reflect the VA IBD population and may not be representative of the non-VA IBD populations in age, gender, or ethnic distribution.

In conclusion, we report that the prevalence of UC and CD is increasing among VA users. We observed a bimodal age-specific incidence distribution in UC, which corresponds to reports in other population-based studies in the United States. This study highlights a large and progressively growing population of VA users with IBD who will require further study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported in part by the American College of Gastroenterology Junior Faculty Development Award to J. K. Hou, a pilot grant from the Houston VA HSR&D Center of Excellence (HFP90-020) to J. K. Hou, and by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service, grant MRP05-305 to J. R. Kramer.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: J. K. Hou: contributed to study design, data analysis, and primary authorship of manuscript. He has approved of the final draft submitted. J. R. Kramer: contributed to study design, data analysis, and editorial input in the manuscript. She has approved of the final draft submitted. P. Richardson and M. Mei: contributed to study design, programming, data abstraction, data analysis, and editorial input in the manuscript. He has approved of the final draft submitted. H. El-Serag: contributed to study design, data interpretation, and editorial input in the manuscript. He has approved of the final draft submitted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cosnes J, Gower-Rousseau C, Seksik P, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1785–1794. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, et al. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1559–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinchbeck BR, Kirdeikis J, Thomson AB. Inflammatory bowel disease in northern Alberta. An epidemiologic study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988;10:505–515. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198810000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sonnenberg A, Wasserman IH. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease among U.S. military veterans. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:122–130. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90468-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1424–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, et al. Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD) Gut. 1996;39:690–697. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.5.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loftus CG, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, et al. Update on the incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1940–2000. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:254–261. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abramson O, Durant M, Mow W, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and time trends of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Northern California, 1996 to 2006. J Pediatr. 2010;157:233.e1–239.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Lewis JD, et al. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in a Northern California managed care organization, 1996–2002. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1998–2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Office of Policy and Planning, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics (008A3) [Accessed June 19, 2012]; Available at: http://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/uniqueveteransMay.pdf.

- 11.Sonnenberg A, Richardson PA, Abraham NS. Hospitalizations for inflammatory bowel disease among US military veterans 1975–2006. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1740–1745. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0764-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hou JK, Kramer JR, Richardson P, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer among Caucasian and African American veterans with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1011–1017. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thirumurthi S, Chowdhury R, Richardson P, et al. Validation of ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes for inflammatory bowel disease among veterans. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2592–2598. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita N, Toki S, Hirohashi T, et al. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Japan: nationwide epidemiological survey during the year 1991. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30(suppl 8):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986–2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:542–549. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vind I, Riis L, Jess T, et al. Increasing incidences of inflammatory bowel disease and decreasing surgery rates in Copenhagen City and County, 2003–2005: a population-based study from the Danish Crohn colitis database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1274–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kugathasan S, Judd RH, Hoffmann RG, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of children with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease in Wisconsin: a statewide population-based study. J Pediatr. 2003;143:525–531. doi: 10.1067/s0022-3476(03)00444-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herrinton LJ, Liu L, Lafata JE, et al. Estimation of the period prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease among nine health plans using computerized diagnoses and outpatient pharmacy dispensings. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:451–461. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]