Abstract

Previous studies demonstrated that an increase in dietary NaCl (salt) intake stimulated endothelial cells to produce Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β). The intent of the present study was to determine the functional significance of increased TGF-β on endothelial cell function. Young Sprague-Dawley rats were fed diets containing 0.3 or 8.0% NaCl for two days before treatment with a specific inhibitor of the TGF-β receptor I/Activin receptor-like kinase 5 (TβRI/ALK5) kinase, or vehicle for another two days. At day 4 of study, endothelial phosphorylated Smad2(S465/467) increased and Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) levels decreased in the high-salt treated rats. In addition, phosphorylated Akt(S473) and phosphorylation of the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase (NOS3) at S1177 increased. Treatment with the TβRI/ALK5 inhibitor reduced Smad2 phosphorylation to levels observed in rats on the low-salt diet and prevented the downstream signaling events induced by the high-salt diet. In HUVEC, reduction in PTEN levels increased phosphorylated Akt and NOS3. Treatment of macrovascular endothelial cells with TGF-β1 increased phosphorylated NOS3 and the concentration of nitric oxide metabolites in the medium, but had no effect on either of these variables in cells pre-treated with siRNA directed against PTEN. Thus, during high-salt intake, an increase in TGF-β directly promoted a reduction in endothelial PTEN levels, which in turn regulated Akt activation and NOS3 phosphorylation. This effect closes a feedback loop that potentially mitigates the effect of TGF-β on the vasculature.

Keywords: dietary salt, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, PTEN, Akt, endothelium

Introduction

The endothelium serves as an integral component of arterial function through maintenance of vascular tone and smooth muscle function. Regulation of endothelial function is complex and may be modified by environmental stress. Findings from several studies developed an evolving paradigm that suggests the vasomotor function of endothelium is modified by dietary NaCl (termed salt in this paper) content.1–6 These prior studies demonstrated that an increase in dietary salt intake promotes the endothelial cell production of active Transforming Growth Factor-beta (TGF-β). The mechanism of endothelial cell activation by salt intake required a signaling cascade involving the large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (BKCa) channel, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase B (Akt).4, 7, 8

PTEN (Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10) is a lipid phosphatase that directly antagonizes the 3-kinase activity of the class I PI3K family. Levels of PTEN therefore directly participate in the regulation of cellular levels of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3).9–12 Among other effects, increased PIP3 levels promote Akt activation.13 One target of activated Akt is S1177 on the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase (NOS3).14 This important post-translational phosphorylation event provides more prolonged NO release by NOS3 at baseline and following stimulation.14–16 Because this latter regulatory mechanism is especially significant in the setting of changes in dietary salt intake,7 endothelial PTEN levels might directly regulate NO production through control of Akt activation. The hypothesis tested in this paper is that dietary salt-induced production of TGF-β promoted alterations in endothelial cell function that facilitated NO production and the primary control mechanism of this process involved PTEN and the TGF-β receptor I/Activin receptor-like kinase 5 (TβRI/ALK5) and the Smad signaling pathway.17

Materials and Methods

Animal and tissue preparation

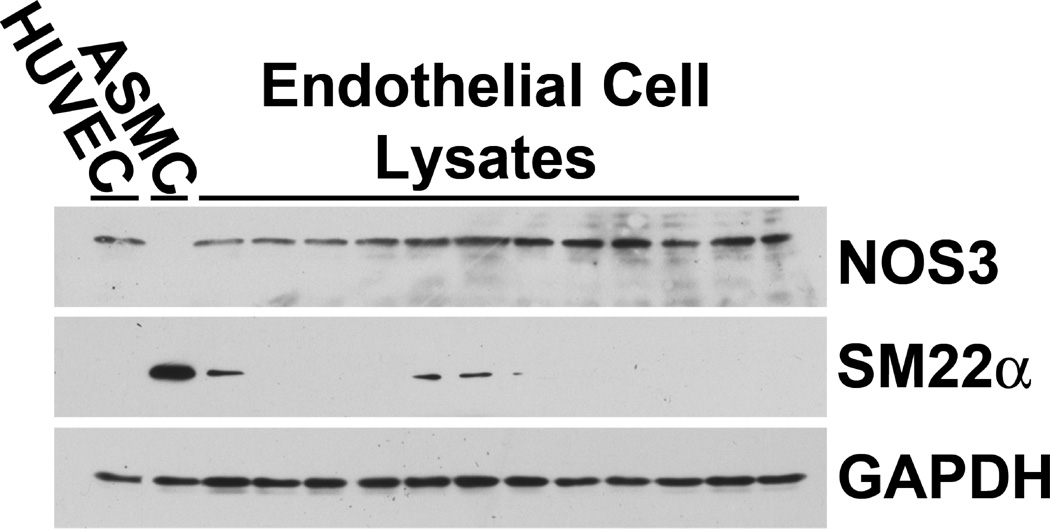

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved the project. Studies were conducted using 24 one-month-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN). The rats were housed under standard conditions and given 0.3% NaCl diet (AIN-76A with 0.3% NaCl; Dyets, Inc., Bethlehem, PA) and water ad libitum for 4 days before receiving diet containing either 0.3% NaCl or 8.0% NaCl (AIN-76A with 8.0% NaCl; Dyets, Inc., Bethlehem, PA) for four days. Two days before the end of the experiment, vehicle or 6-[2-tert-Butyl-5-(6-methyl-pyridin-2-yl)-1H-imidazol-4-yl]-quinoxaline (SB525334, (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX), which is a specific inhibitor of the kinase activity of TGF-β receptor I/Activin receptor-like kinase 5 (TβRI/ALK5) and has been shown to prevent renal fibrosis in vivo in puromycin-induced nephritis,18 was added to the drinking water to achieve a dose of 10 mg/kg/d. Four groups of rats were studied. Group 1 rats received the 0.3% NaCl diet and vehicle; group 2 rats were fed the 0.3% NaCl diet and given SB525334. Group 3 rats received 8.0% NaCl and vehicle, while group 4 rats received 8.0% NaCl and SB525334. On the final day of study, rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane. Aortae were harvested under sterile conditions and aortic endothelial cell lysates were obtained as described previously.4 To validate further the experimental approach used to isolate aortic endothelial cells, endothelial lysates from 12 animals were probed for NOS3, SM22α (transgelin), which is a protein abundantly expressed in smooth muscle cells,19 and GAPDH using western blot analyses (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Endothelial cell lysates from 12 rats were probed for the presence of NOS3, SM22α (transgelin), which is strongly expressed in smooth muscle cells 19, and GAPDH. These western blot analyses were compared to lysates from HUVEC (lane 1) and ASMC in culture (lane 2). NOS3 was found in HUVEC and in all the endothelial lysates, but not the lysate of cultured aortic smooth muscle cells (ASMC). In contrast, SM22α was not observed in HUVEC but was abundantly expressed in ASMC. This sensitive assay revealed that eight of the twelve endothelial cell lysates contained no SM22α, while four of the twelve lysates demonstrated slight expression of SM22α. When expressed relative to GAPDH, the amount of SM22α in the endothelial cell lysates averaged 2.7±1.6% of that observed in the lysate of the ASMC. These data demonstrated minimal contamination of the endothelial cell lysates with smooth muscle tissue.

Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC) and Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells (ASMC) in culture

Primary cultures of macrovascular endothelial cells (HUVEC) were obtained commercially (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Monolayers of HUVEC were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2/95% air in Medium 200 supplemented with Low Serum Growth Supplement (Life Technologies). Medium was exchanged at 48-h intervals and cells were not used beyond 25–30 passages. Primary cultures of aortic smooth muscle cells (ASMC) were produced and maintained using previously developed protocols.20

Silencing endothelial PTEN and in vitro incubation studies

RNA interference was accomplished using SignalSilence® PTEN siRNA II (#6538, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); non-targeting siRNA #1 (D-001810, Dharmacon RNA Technologies, Lafayette, CO) served as a control in these experiments. HUVEC at 80% confluence were transfected using siRNA transfection reagent (DharmaFECT4, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) containing the siRNA. Preliminary experiments using siTOX transfection control (Thermo Fisher Scientific) determined the optimum exposure conditions that maximized transfection efficiency and minimized toxicity. PTEN siRNA (100 nM) was complexed with 2 µl of DharmaFECT4 in 200-µl total volume and then added to complete medium in a final volume of 1 ml for each well in a 12-well plate. After incubation in the transfection solution for 12 h, the medium was replaced and incubation continued up to 72 h. In some experiments, cells were then incubated in medium that contained vehicle alone or human recombinant TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), 12 pM, for an additional 16 h.

After incubation, the conditioned medium was harvested, centrifuged at 300 xg for 10 min at 4°C to remove cell debris, and then stored at −80°C until assayed for nitric oxide metabolites (NOx). Cell lysates were obtained for analysis of PTEN, Akt, NOS3, GAPDH, and total protein concentration.

Nitric oxide metabolites (NOx)

In samples of the conditioned medium, NOx was assayed using the optimized VCl3 reagent-based kit (QuantiChrom Nitric Oxide Assay Kit, (D2NO-100, BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA), which determines nitrite concentrations using Griess methodology following reduction of nitrate to nitrite. The time required for the reduction is 10 min at 60°C. In these studies, cell culture media samples were deproteinated, and assays were performed in duplicate and averaged.

Western blot analyses

Cell lysates were produced using modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer that contained 10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 0.1% SDS, 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM PMSF, and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete, EDTA-free, Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). Total protein concentration was determined using a kit (BCA Protein Assay Reagent Kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific Pierce Protein Research Products, Rockford, IL), and the samples were processed for western blotting. Protein extracts (10 to 60 µg) were boiled for 3 min in Laemmli buffer and separated by 7 to 12% SDS-PAGE (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), before electrophoretic transfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat milk and then probed with an antibody (diluted 1:1000) that recognized specifically NOS3 (BD Biosciences, BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, California), PTEN, phospho-NOS3(S1177), phospho-Akt(S473), total Akt (all from Cell Signaling Technology), SM22α (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO), and GAPDH (Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, MA), which served as the loading control. The published cDNA sequence of rat NOS3 (accession # NM_021838) showed that the serine residue that corresponded to S1177 in the human NOS3 sequence was S1176. In this paper, phosphorylation of this serine residue was referred to as phospho-NOS3(S1177). The membranes were developed in standard fashion (SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate; Thermo Fisher Scientific Pierce Protein Research Products); density of the bands was quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Statistical analyses

Data were expressed as the mean±SEM. Significant differences were determined by ANOVA with post hoc testing. A p-value < 0.05 assigned statistical significance.

Results

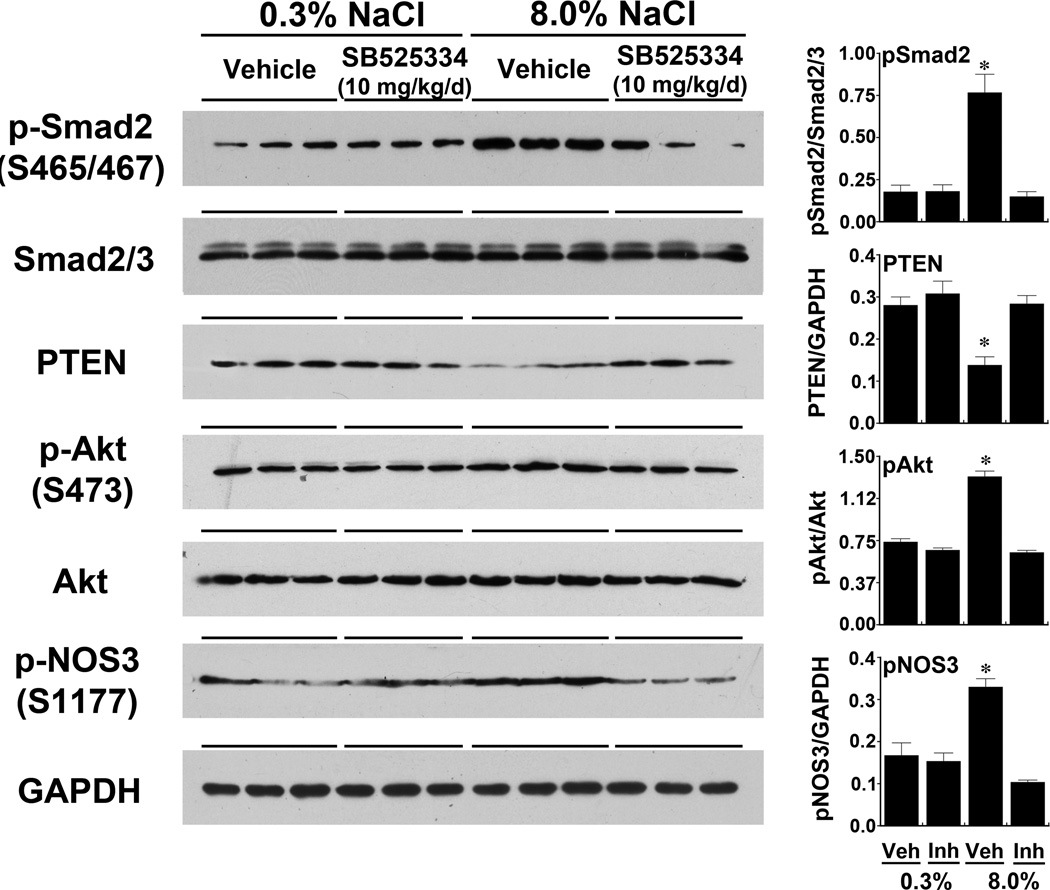

An increase in dietary salt intake promoted activation of the endothelial Smad signaling pathway, which decreased PTEN levels

Four groups of rats were studied. The first two groups were fed the 0.3% NaCl diet and given either vehicle or SB525334, which inhibits TβRI/ALK5,18 two days before the end of the experiment. The second two groups received the 8.0% NaCl diet and either vehicle or SB525334 two days before the end of the experiment. An increase in dietary salt intake increased p-Smad2(S465/467) in endothelial lysates; this increase was inhibited by treatment with SB525334 (Figure 2). Total Smad2/3 levels did not change. Increased salt intake also decreased endothelial PTEN levels and increased p-Akt(S473) without changing total Akt levels; treatment with SB525334 prevented these salt-induced changes in PTEN and p-Akt(S473). The dietary salt-induced relative increase in p-NOS3(S1177), which increases NO production,14–16 was abrogated by treatment with SB525334 (Figure 2). As shown previously,1, 5, 6 a high salt diet increased NOS3 protein levels in young rats. In the present study, compared to rats on the 0.3% NaCl diet, the 8.0% NaCl diet increased relative NOS3 (NOS3/GAPDH) levels (0.11±0.004 vs. 0.27±0.02; P < 0.001). Addition of SB525334 did not inhibit NOS3 protein expression during high salt intake (0.28±0.01) and did not change NOS3 protein expression during low salt intake (0.14±0.01).

Fig. 2.

Increased dietary salt intake activates the Smad2 signaling pathway to promote a decrease in endothelial PTEN levels, phosphorylation of Akt at S473, and phosphorylation of NOS3 at S1177. The TβRI/ALK5 kinase inhibitor, SB525334, prevented the salt-induced increases in Smad2 phosphorylation and the downstream signaling events that included the reduction in PTEN levels and increases in phosphorylated Akt(S473) and phosphorylated NOS3(S1177). The graphs on the right represented the pertinent relative protein levels of all the animals in the study (n = 6 rats in each group). *P < 0.05 compared to the other 3 groups

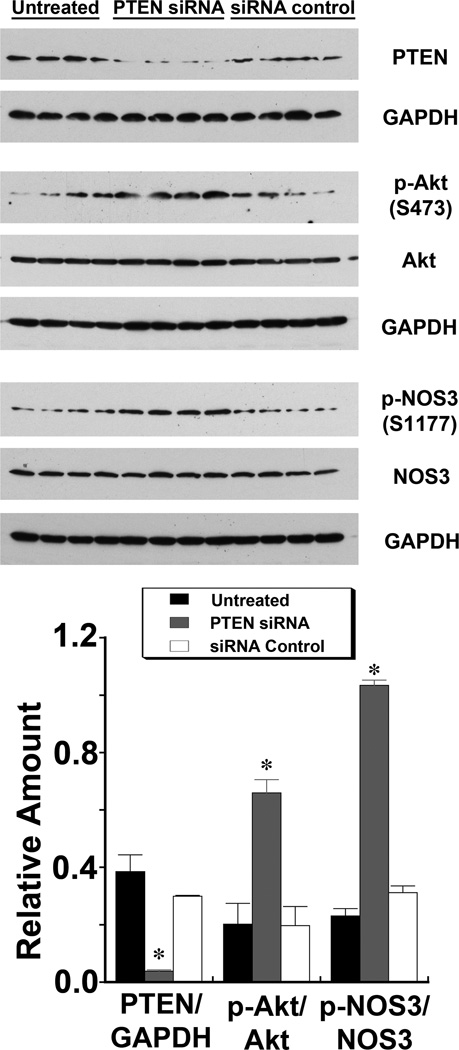

Endothelial PTEN levels determined Akt activity and NOS3 phosphorylation in vitro

PTEN levels fell in HUVEC treated with siRNA directed against PTEN. A concomitant increase in p-Akt(S473) without a change in total Akt levels was observed. In addition, p-NOS3(S1177) increased without a change in NOS3 when endothelial PTEN levels were reduced (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Reduction in PTEN levels by treatment of HUVEC with siRNA directed against PTEN increased level of phosphorylated Akt(S473) and levels of phosphorylated NOS3(S1177). The graphs represent summaries of 4 experiments in each group. *P < 0.05 compared to the other 3 groups

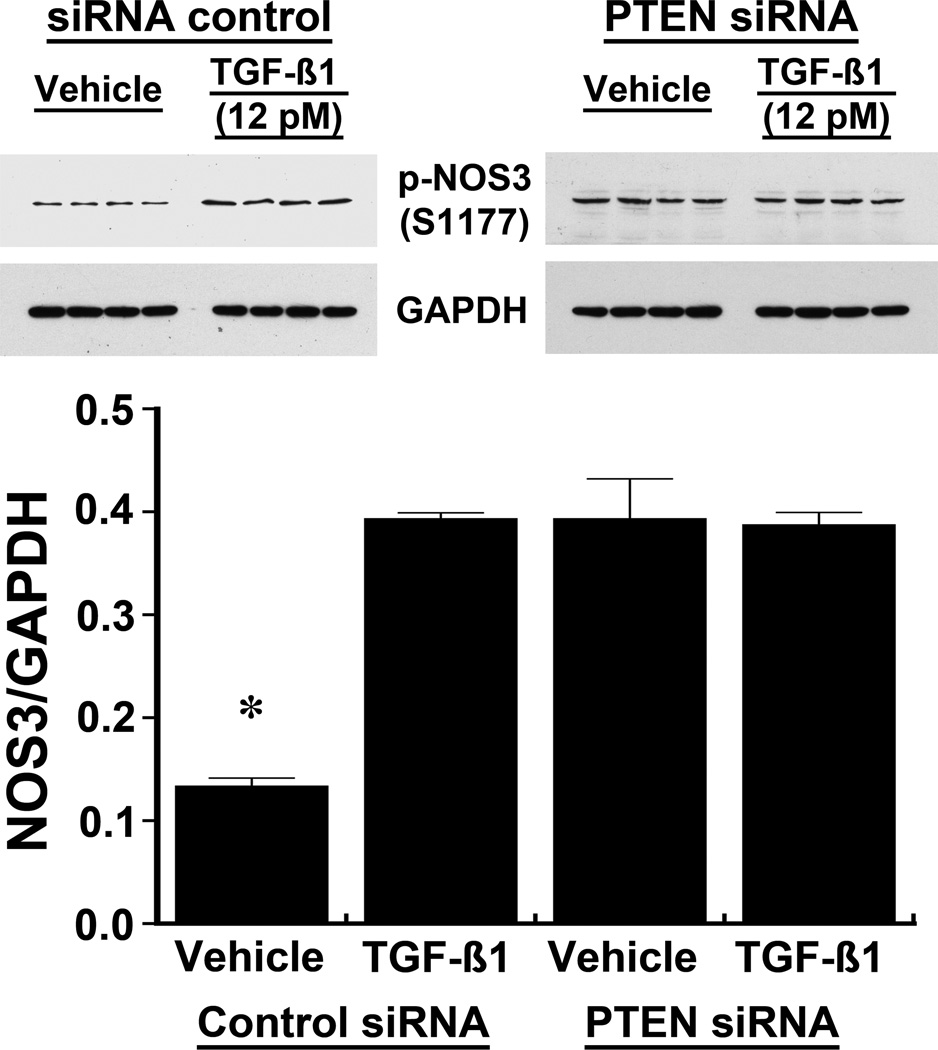

The effect of TGF-β on p-NOS3 and NO production was dependent on PTEN

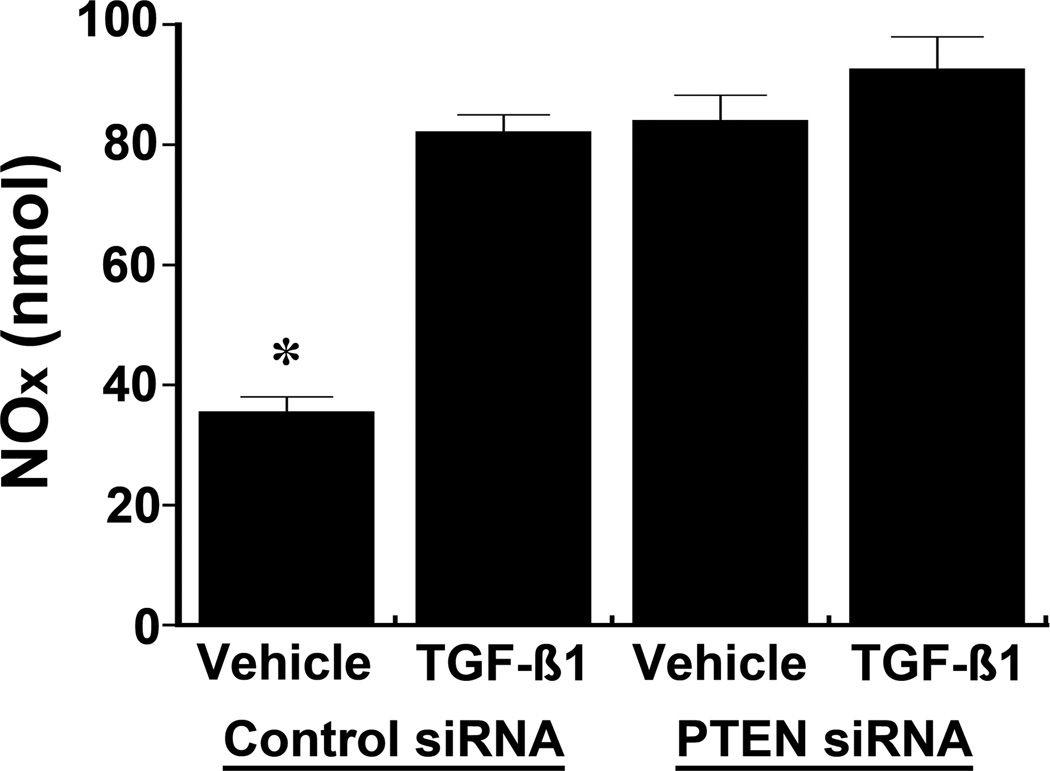

Following treatment with siRNA directed against PTEN, cells were incubated with 12 pM of active TGF-β1 to determine if TGF-β regulated p-NOS3 levels independently of PTEN. Addition of TGF-β promoted an increase in p-NOS3(S1177) in the vehicle-treated cells, while TGF-β1 produced no additional effect on p-NOS3(S1177) in HUVEC lacking PTEN from treatment with siRNA (Figure 4). NOx in the medium increased with TGF-β1 treatment, but no changes in NOx levels were observed following TGF-β1 treatment in the siRNA-pretreated cells (Figure 5).

Fig. 4.

The effect of TGF-β1 on the phosphorylation of NOS3 at S1177 in HUVEC was dependent on PTEN. Addition of TGF-β1, 12 pM, to the medium of HUVEC pre-treated with a non-targeting siRNA increased phosphorylation of NOS3(S1177). In contrast, following reduction in PTEN in HUVEC treated with siRNA directed against PTEN, TGF-β1 produced no changes in phosphorylated NOS3(S1177). The data (n = 4 experiments in each group) were also represented graphically. *P < 0.05 compared to the other 3 groups

Fig. 5.

The effect of TGF-β1 on the release into the medium of NO, which was determined by quantifying the concentrations of nitrite and nitrate, was dependent on PTEN expression in HUVEC. TGF-β increased NO production in HUVEC pre-treated with non-targeting siRNA, but produced no additional effect when PTEN was reduced by pre-treatment with siRNA directed against PTEN (n = 4 experiments in each group). *P < 0.05 compared to the other 3 groups

Discussion

Work performed over the past 15 years has shown that the endothelium acts as a “dietary salt sensor” that responds to changes in salt intake. This effect is mediated through endothelial BKCa channel activity, which regulates not only the development of a signalosome complex composed of Pyk2, c-Src and PI3K, but also promotes a decrease in endothelial PTEN levels.1, 3–8, 21–24 PTEN is a phosphatase that counteracts the production of PIP3 by PI3K. Decreasing PTEN levels therefore facilitates the activity of PI3K, which regulates Akt activation through the generation of intracellular PIP3.9–12 One net effect of increased dietary salt intake is augmented endothelial production of TGF-β and potentially bioavailable nitric oxide (NO).3 Building upon these findings, the data in the present study demonstrated that 1) dietary salt induced endothelial cell production of TGF-β, which promoted an autocrine function on endothelial cells mediated through TβRI/ALK5 and the Smad signaling pathway; 2) TGF-β directly regulated endothelial PTEN levels in vivo through this canonical TGF-β-signaling pathway; and 3) the inhibitory effect of TGF-β on PTEN promoted endothelial cell production of NO by increasing Akt-mediated phosphorylation of NOS3 at S1177. By directly promoting a decrease in endothelial PTEN levels, active TGF-β can facilitate the generation of endothelium-derived NO, which in turn has been shown to mitigate the production of TGF-β in the vasculature,3 as well as promote other endothelial cell functions that are dependent upon Akt.25

The PI3K/PTEN/Akt/NOS3 pathway is gaining increased attention in endothelial cell biology. Findings from the present study complemented prior studies that demonstrated the critical interrelationship between enzymatic activities of both PI3K and PTEN in the regulation of intracellular PIP3 levels.9–12 PIP3 activates pleckstrin-homology domain-containing enzymes that include Akt;13 in turn, activated Akt facilitates NOS3 phosphorylation at S1177 and thereby increases NO production.26 NO production through Akt activation has been shown to increase during high dietary salt intake in young animals7 and this pathway is also directly involved in the regulation of vascular permeability27 and vasodilation induced by vascular endothelial growth factor.28 Several pharmaceutical agents also interact with this pathway. Statins activate endothelial Akt, which results in phosphorylation of NOS3.29, 30 Nitroglycerin appears to increase endothelial NO production by directly inhibiting PTEN, promoting Akt activation and NOS3 phosphorylation.31 Hyperglycemia directly inhibits this pathway via reactive oxygen species-mediated dephosphorylation of Akt32 and direct O-linked N-acetylglucosamine modification of NOS3 at S1177.33 Thus, the PI3K/PTEN/Akt/NOS3 pathway is a critical regulator of endothelial NO production and may be altered by changes in the cellular environment such as increased salt intake, cardiovascular drugs, and disease states that include diabetes mellitus.

Other factors participate in the endothelial cell response to changes in dietary salt intake. Aging promotes a reduction in NO produced by NOS3 in response to increased salt intake. The effect of aging appears to be related to endothelial cell PTEN levels, which increase with age and become refractory to changes in dietary salt intake in rats.6 An age-related increase in PTEN levels in cultured human microvascular endothelial cells has also been demonstrated.34 Shear-induced generation of NO by NOS3 appears to be optimized by the concomitant expression of GTP cyclohydrolase I, the rate-limiting enzyme in tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) biosynthesis.35 Generation of oxidative stress in the endothelium independently mediates reduction in bioavailable NO and enhances peroxynitrite formation particularly in advanced age.36–39

Perspectives

Vascular pathology (excluding atherosclerosis) includes remodeling not only of resistance vessels, but also compliance vessels. The disease burden – myocardial infarction, stroke, left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, kidney failure, and death – associated with decreased arterial compliance is very high.40–45 As an independent predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, reductions in conduit artery compliance represent an important health problem for the nation as a whole. The fibrogenic growth factor, TGF-β, appears to be involved in this process.46 The present studies uncovered a direct effect of dietary salt-induced production of TGF-β on macrovascular endothelial cell function. This effect – mediated through the Smad-signaling pathway – reduced intracellular PTEN and thereby facilitated Akt activation, which was critically important in NOS3 phosphorylation at S1177. Thus, the endothelial production of TGF-β in response to increased dietary salt intake resulted in an autocrine effect that impacted NO production, a potential inhibitor of the effects of TGF-β on vascular function.3 While presently untested, this inhibitory feedback system may be critically important in determining the changes in arterial compliance related to excess salt intake.47–49

Novelty and Significance.

1) What Is New?

Novel findings demonstrated in the present study include:

An increase in dietary salt stimulated endothelial cell production of TGF-β, an important growth factor that is now shown to have a direct action on endothelial cells mediated through the classical signaling pathway activated by TGF-β;

TGF-β directly regulated an important phosphatase (PTEN) in vascular endothelium; and

The inhibitory effect of TGF-β on intracellular levels of PTEN promoted endothelial cell production of nitric oxide by increasing the phosphorylation of the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase.

2) What Is Relevant?

Work from our laboratory has demonstrated that the endothelium acts as a “salt sensor” that responds to changes in dietary salt intake. One net effect of increased dietary salt intake is augmented endothelial production of TGF-β and potentially bioavailable nitric oxide (NO). Building upon these findings, the data in the present study demonstrated that by directly promoting a decrease in endothelial PTEN levels, active TGF-β produced during high salt intake can facilitate the generation of endothelium-derived NO, which in turn has been shown to mitigate the production of TGF-β in the vasculature as well as promote other endothelial cell functions that are dependent upon Akt. This newly identified autocrine action of salt-induced TGF-β is therefore important in arterial function.

3) Summary

The present studies uncovered a direct effect of dietary salt-induced production of TGF-β on endothelial cell function. The experiments showed definitively the involvement of TGF-β on intracellular PTEN levels in the endothelium. In so doing, Akt activation permitted increased, permitting the phosphorylation of NOS3 phosphorylation at S1177 and generation of nitric oxide (NO). Thus, the endothelial production of TGF-β in response to increased dietary salt intake resulted in an autocrine effect that impacted NO production, a potential inhibitor of the effects of TGF-β on vascular function.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding

A grant (1 IP1 BX001595) from the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Institutes of Health grants (R01 DK046199 and P30 DK079337 (George M. O'Brien Kidney and Urological Research Centers Program)), supported this research.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosure Statement

None

References

- 1.Ying WZ, Sanders PW. Dietary salt increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase and TGF-beta1 in rat aortic endothelium. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H1293–H1298. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.4.H1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ying WZ, Sanders PW. Increased dietary salt activates rat aortic endothelium. Hypertension. 2002;39:239–244. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.104142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ying WZ, Sanders PW. The interrelationship between TGF-beta1 and nitric oxide is altered in salt-sensitive hypertension. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;285:F902–F908. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00177.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ying WZ, Aaron K, Sanders PW. Mechanism of dietary salt-mediated increase in intravascular production of TGF-beta1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F406–F414. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90294.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ying WZ, Sanders PW. Dietary salt enhances glomerular endothelial nitric oxide synthase through TGF-beta1. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:F18–F24. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.1.F18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ying WZ, Aaron KJ, Sanders PW. Effect of aging and dietary salt and potassium intake on endothelial PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome 10) function. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ying WZ, Aaron K, Sanders PW. Dietary salt activates an endothelial proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2/c-src/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex to promote endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation. Hypertension. 2008;52:1134–1141. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.121582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ying WZ, Aaron K, Wang PX, Sanders PW. Potassium inhibits dietary salt-induced transforming growth factor-beta production. Hypertension. 2009;54:1159–1163. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.138255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanhaesebroeck B, Leevers SJ, Ahmadi K, Timms J, Katso R, Driscoll PC, Woscholski R, Parker PJ, Waterfield MD. Synthesis and function of 3-phosphorylated inositol lipids. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:535–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Brothers GM, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T, Ruland J, Penninger JM, Siderovski DP, Mak TW. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 1998;95:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mellor P, Furber LA, Nyarko JN, Anderson DH. Multiple roles for the p85alpha isoform in the regulation and function of PI3K signalling and receptor trafficking. Biochem J. 2012;441:23–37. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanhaesebroeck B, Stephens L, Hawkins P. PI3K signalling: The path to discovery and understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:195–203. doi: 10.1038/nrm3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stocker H, Andjelkovic M, Oldham S, Laffargue M, Wymann MP, Hemmings BA, Hafen E. Living with lethal PIP3 levels: Viability of flies lacking PTEN restored by a PH domain mutation in Akt/PKB. Science. 2002;295:2088–2091. doi: 10.1126/science.1068094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fulton D, Gratton JP, Sessa WC. Post-translational control of endothelial nitric oxide synthase: Why isn't calcium/calmodulin enough? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;299:818–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bauer PM, Fulton D, Boo YC, Sorescu GP, Kemp BE, Jo H, Sessa WC. Compensatory phosphorylation and protein-protein interactions revealed by loss of function and gain of function mutants of multiple serine phosphorylation sites in endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14841–14849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakao A, Imamura T, Souchelnytskyi S, Kawabata M, Ishisaki A, Oeda E, Tamaki K, Hanai J, Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-beta receptor-mediated signalling through Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4. EMBO J. 1997;16:5353–5362. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grygielko ET, Martin WM, Tweed C, Thornton P, Harling J, Brooks DP, Laping NJ. Inhibition of gene markers of fibrosis with a novel inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta type 1 receptor kinase in puromycin-induced nephritis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:943–951. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.082099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lees-Miller JP, Heeley DH, Smillie LB. An abundant and novel protein of 22 kDa (SM22) is widely distributed in smooth muscles. Purification from bovine aorta. Biochem J. 1987;244:705–709. doi: 10.1042/bj2440705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen PY, Gladish RG, Sanders PW. Vascular smooth muscle nitric oxide synthase anomalies in Dahl/Rapp salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 1998;31:918–924. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.4.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ying WZ, Sanders PW. Dietary salt modulates renal production of transforming growth factor-beta in rats. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:F635–F641. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.4.F635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ying W-Z, Sanders PW. Increased dietary salt activates rat aortic endothelium. Hypertension. 2002;39:239–244. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.104142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanders PW. Salt intake, endothelial cell signaling, and progression of kidney disease. Hypertension. 2004;43:142–146. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000114022.20424.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanders PW. Vascular consequences of dietary salt intake. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F237–F243. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00027.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Wang Y, Wang Y, Ma Y, Lan Y, Yang X. Transforming growth factor beta-regulated microRNA-29a promotes angiogenesis through targeting the phosphatase and tensin homolog in endothelium. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10418–10426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.444463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lane P, Gross SS. Disabling a c-terminal autoinhibitory control element in endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by phosphorylation provides a molecular explanation for activation of vascular NO synthesis by diverse physiological stimuli. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19087–19094. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200258200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Six I, Kureishi Y, Luo Z, Walsh K. Akt signaling mediates VEGF/VPF vascular permeability in vivo. FEBS Lett. 2002;532:67–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03630-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeBlanc AJ, Shipley RD, Kang LS, Muller-Delp JM. Age impairs Flk-1 signaling and NO-mediated vasodilation in coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2280–H2288. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00541.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kureishi Y, Luo Z, Shiojima I, Bialik A, Fulton D, Lefer DJ, Sessa WC, Walsh K. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin activates the protein kinase Akt and promotes angiogenesis in normocholesterolemic animals. Nat Med. 2000;6:1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/79510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bell RM, Yellon DM. Atorvastatin, administered at the onset of reperfusion, and independent of lipid lowering, protects the myocardium by up-regulating a pro-survival pathway. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:508–515. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02816-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao M, Sudhahar V, Ansenberger-Fricano K, Fernandes DC, Tanaka LY, Fukai T, Laurindo FR, Mason RP, Vasquez-Vivar J, Minshall RD, Stadler K, Bonini MG. Nitroglycerin drives endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:427–435. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho FM, Lin WW, Chen BC, Chao CM, Yang CR, Lin LY, Lai CC, Liu SH, Liau CS. High glucose-induced apoptosis in human vascular endothelial cells is mediated through NF-kappaB and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase pathway and prevented by PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathway. Cell Signal. 2006;18:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du XL, Edelstein D, Dimmeler S, Ju Q, Sui C, Brownlee M. Hyperglycemia inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity by posttranslational modification at the Akt site. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1341–1348. doi: 10.1172/JCI11235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarnawski AS, Pai R, Tanigawa T, Matysiak-Budnik T, Ahluwalia A. PTEN silencing reverses aging-related impairment of angiogenesis in microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394:291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lam C-F, Peterson TE, Richardson DM, Croatt AJ, d'Uscio LV, Nath KA, Katusic ZS. Increased blood flow causes coordinated upregulation of arterial eNOS and biosynthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H786–H793. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00759.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Loo B, Labugger R, Skepper JN, Bachschmid M, Kilo J, Powell JM, Palacios-Callender M, Erusalimsky JD, Quaschning T, Malinski T, Gygi D, Ullrich V, Luscher TF. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1731–1744. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blackwell KA, Sorenson JP, Richardson DM, Smith LA, Suda O, Nath K, Katusic ZS. Mechanisms of aging-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation: Role of tetrahydrobiopterin. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2448–H2453. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00248.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.el-Remessy AB, Bartoli M, Platt DH, Fulton D, Caldwell RB. Oxidative stress inactivates VEGF survival signaling in retinal endothelial cells via PI 3-kinase tyrosine nitration. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:243–252. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katusic ZS, d'Uscio LV, Nath KA. Vascular protection by tetrahydrobiopterin: Progress and therapeutic prospects. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, Burke GL, Wolfson SK., Jr Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular health study collaborative research group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:14–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Rourke MF, Safar ME. Relationship between aortic stiffening and microvascular disease in brain and kidney: Cause and logic of therapy. Hypertension. 2005;46:200–204. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000168052.00426.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fesler P, Safar ME, du Cailar G, Ribstein J, Mimran A. Pulse pressure is an independent determinant of renal function decline during treatment of essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1915–1920. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3281fbd15e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: Major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part I: Aging arteries: a "set up" for vascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:139–146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048892.83521.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P. Recent advances in arterial stiffness and wave reflection in human hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1202–1206. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.106.076166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekundayo OJ, Dell'italia LJ, Sanders PW, Arnett D, Aban I, Love TE, Filippatos G, Anker SD, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bakris G, Mujib M, Ahmed A. Association between hyperuricemia and incident heart failure among older adults: A propensity-matched study. Int J Cardiol. 2010;142:279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fleenor BS, Marshall KD, Durrant JR, Lesniewski LA, Seals DR. Arterial stiffening with ageing is associated with transforming growth factor-beta1-related changes in adventitial collagen: Reversal by aerobic exercise. J Physiol. 2010;588:3971–3982. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.194753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Todd AS, Macginley RJ, Schollum JB, Johnson RJ, Williams SM, Sutherland WH, Mann JI, Walker RJ. Dietary salt loading impairs arterial vascular reactivity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:557–564. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gates PE, Tanaka H, Hiatt WR, Seals DR. Dietary sodium restriction rapidly improves large elastic artery compliance in older adults with systolic hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;44:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000132767.74476.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He FJ, Marciniak M, Visagie E, Markandu ND, Anand V, Dalton RN, MacGregor GA. Effect of modest salt reduction on blood pressure, urinary albumin, and pulse wave velocity in white, black, and Asian mild hypertensives. Hypertension. 2009;54:482–488. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.133223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]