Abstract

Purpose

Young eyes compensate for the defocus imposed by spectacle lenses by changing their rate of elongation and their choroidal thickness, bringing their refractive status back to the pre-lens condition. We asked whether the initial rate of change either in the ocular components or in refraction is a function of the power of the lenses worn, a result that would be consistent with the existence of a proportional controller mechanism.

Methods

Two separate studies were conducted; both tracked changes in refractive errors and ocular dimensions. Study A: To study the effects of lens power and sign, young chicks were tracked for 4 days after they were fitted with positive (+5, +10 or +15 D) or negative (−5, −10, −15 D) lenses over one eye. In another experiment, biometric changes to plano, +1, +2 and +3 D lenses were tracked over a 24 h treatment period. Study B: Normal emmetropisation was tracked from hatching to 6 days of age and then a defocusing lens, either +6 D or −7 D, was fitted over one eye and additional biometric data collected after 48 h.

Results

In study A, animals treated with positive lenses (+5, +10 or +15 D) showed statistical similar initial choroid responses, with a mean thickening 24 μm h−1 over the first 5 h. Likewise, with the low power positive lenses, a statistically similar magnitude of choroidal thickening was observed across groups (+1 D: 46.0 ± 7.8 μm h−1; +2 D: 53.5 ± 9.9 μm h−1; +3 D 53.3 ± 24.1 μm h−1) in the first hour of lens wear compared to that of a plano control group. These similar rates of change in choroidal thickness indicate that the signalling response is binary in nature and not influenced by the magnitude of the myopic defocus. Treatments with −5, −10 and −15 D lenses induced statistically similar amounts of choroidal thinning, averaging −70 ± 15 μm after 5h and −96 ± 45 μm after 24 h. Similar rates in inner axial length changes were also seen with these lens treatments until compensation was reached, once again indicating that the signalling response is not influenced by the magnitude of hyperopic defocus. In study B, after 48 h of +6 D lens treatment, the average refractive error and choroidal changes were found to be larger in magnitude than expected if perfect compensation had taken place, with a + 2.4 D overshoot in refractive compensation.

Conclusion

Taken together, our results with both weak and higher power positive lenses suggest that eye growth is guided more by the sign than by the magnitude of the defocus, and our results for higher power negative lenses support a similar conclusion. These behaviour patterns and the overshoot seen in Study B are more consistent with the behaviour of a bang-bang controller than a proportional controller.

Keywords: chick, choroid, emmetropisation, myopia

Introduction

Emmetropisation is the process by which the growing eye adjusts the relationship between its physical length and focal length so that the images of distant objects fall on the retina. In other words, it is the process by which young eyes correct neonatal refractive errors, most prominently during early postnatal life. In the laboratory this process is studied using optical defocusing lenses to artificially impose refractive errors – positive and negative spectacle lenses for myopic and hyperopic refractive errors respectively. In young eyes, induced changes in the rate of elongation and in choroidal thickness rapidly ameliorate these refractive errors.1–3 These compensatory responses suggest an active negative (closed loop) feedback mechanism by which eyes correct for refractive errors. The existence of such a feedback mechanism in animals has contributed to renewed interest in the role of focusing errors in myopic changes in children and young adults – that they may result from a misdirection of growth as a consequence of the normal operation of this active emmetropisation mechanism attempting to compensate for hyperopic defocus, either due to lags of accommodation during extensive near vision4,5 and/or due to variations in eye shape.6,7

Although several hypotheses have been advanced to explain how emmetropisation might work, these have been hindered by the paucity of the information on the nature of emmetropisation, especially the control system aspects.8–10 In the studies described here we addressed two issues that are central to the understanding of a negative feedback control system. First, is the output simply switched on and off according to the sign of the error signal, or is the output proportional to the magnitude of the error signal? Second, what is the set-point? Specifically, is compensation absolute (i.e., bringing the eye to optical emmetropia) or relative (i.e., correcting only for the imposed defocus, so returning the eye to its pre-lens refractive error)?

With respect to the first issue, two types of controllers are typical of negative feedback circuits. One, referred to as a bang-bang controller, operates in an ‘on-or-off’ mode as is typical of thermostat-controlled furnaces.11 The other, referred to as a proportional controller, may react the same as a bang-bang controller when far from its set-point but show graded responses when approaching its set-point. The latter behaviour is exemplified by furnaces that put out less heat when the temperature is close to the set-point.11 In the case of lens compensation, although the reported magnitudes of compensation are generally proportional to the power of the lenses worn (Figure 1), this does not preclude either type of controller. In the case of a proportional controller, eyes wearing more powerful lenses are expected to compensate at a faster rate, for example, if the rate of ocular elongation was proportional to the amount of defocus. In the case of a bang-bang controller, the rate of compensation would be the same for all lenses of the same sign, with full compensation being achieved earlier with lower powered lenses. In the latter case, if the compensation were measured over a long enough period, the average measured rate of change for the eyes with less powerful lenses would be less, even if the actual (early) rate of change did not depend on lens power. Thus to distinguish between these two types of controllers, one needs to measure and compare early responses to lenses of different power. Furthermore, the bang-bang controller, but not the proportional controller, is likely to overshoot full compensation and show oscillations about its set-point.

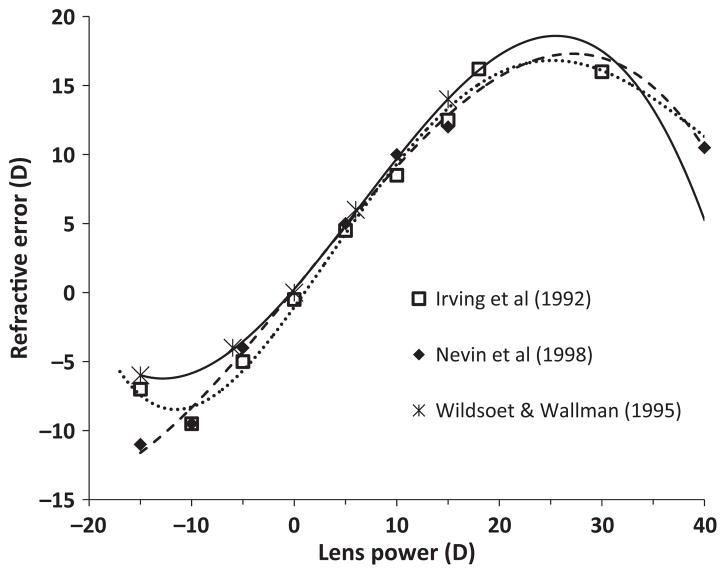

Figure 1.

Compensatory refractive changes induced by spectacle lenses reflect both the sign and power of the inducing lenses: data replotted from Irving et al. (1992) for lenses worn for 7 days from hatching, from Nevin et al. (1998) for lenses worn for 4 days starting at 7 days of age, and from Wildsoet and Wallman (1996) for lenses worn for 5 days starting at 3 days.

With respect to the second issue – whether the compensation is absolute – the simplest, physicist view of emmetropisation would be that it compensates for all refractive errors – pre-existing and imposed, bringing the eye to zero refractive error. However, longitudinal measurements of developmental changes in refractive error in a number of experimental animals, including young chicks, 12 tree shrews13 and monkeys14–16 and also in children17 suggest that individual eyes asymptote at idiosyncratic refractions, implying either that these different refractions all lie within the dead-zone (depth-of-focus) of the emmetropisation controller or that each individual has its own ‘emmetropic’ set-point. Experimental studies of lens compensation offer an opportunity to further address this issue although most published data cannot be partitioned into changes occurring in response to the imposed focusing errors from changes in response to the eye’s intrinsic refractive error.

To address these issues, we carried out two studies using spectacle lenses fitted to young chicks. One study (Study A), compared the effects of lenses of different power on the rates of change in refraction and ocular components. We also compared refractive end-points with imposed defocus levels. In a second study (Study B), we followed the on-going natural emmetropisation of young chicks for 5 days before fitting lenses so that we could assess lens compensation with respect to pre-treatment trends.

Pilot studies providing the motivation for the research described here, as well as data reported for the second study described here, were previously published in abstract form.18

Methods

Subjects & treatments

White-Leghorn chicks (Gallus gallus domesticus) were either hatched in the laboratory from fertile eggs (Department of Animal Science, University of California, Davis) or purchased as day-old chicks (Truslow Farms, New Mexico) and raised in a temperature controlled environment on a 12 h light, 12 h dark cycle (Study A) or a 14 h light, 10 h dark cycle (Study B). Food and water were freely available. Care and use of the animals complied with the ARVO Resolution of the Use of Animals in Research.

Velcro-mounted lenses were used to impose defocus in all experiments. The lenses were made from PMMA material to a modified human contact lens design,2 which provided the chicks with panoramic vision through the lenses. During lens wear, chicks were kept in cages with raised floors and had their food sieved to minimize the accumulation of dust on the lenses. Lenses were removed and cleaned 1–3 times per day.

Measurements

All measurements were made under either halothane or isoflurane anaesthesia (Phoenix Laboratories http://www.pclv.net/; 1–1.5% in oxygen). In Study B topical vecuronium bromide (Organon; 1 mg mL−1 in 0.85% saline with 0.026% benzalkonium chloride) was used to induce mydriasis (and presumably cycloplegia) for measurements.

Refractive errors were measured either by static streak retinoscopy (Study A) or with a Hartinger Coincidence Refractometer (Jena; modified for use with small eyes) in Study B (for details, see).19 All refraction data are presented as ‘spherical equivalents’ (i.e. the average of the refractive errors measured in the two principal meridians). Data are not corrected for the ‘small eye’ artifact.20

Axial ocular dimensions were measured by high frequency A-scan ultrasonography (35 MHz transducer, 100 MHz sampling), which allows the thickness of the retina, choroid and sclera to be measured in addition to the principal ocular components (anterior chamber depth, lens thickness, vitreous chamber depth; for details see.21 Previous studies have shown that spectacle lens compensation in young chicks is accomplished principally by changes in choroidal thickness and the rate of overall ocular elongation, which reflects scleral changes.2 The common clinical practice of regarding the axial length as the distance from cornea to the anterior surface of the retina (i.e. optical axial length), confounds these two parameters because increased choroidal thickness reduces the axial length, defined in that way. For the current studies, axial length was calculated instead as the distance from the anterior surface of the cornea to the inner surface of the sclera, as an index of scleral changes, and is referred to as inner axial length.

Studies

A. Effects of lens power & sign

To investigate whether compensation for imposed defocus depends on its magnitude, as well as its sign, six-day-old chicks were measured (refractive error and axial dimensions) and then fitted with either positive (+5, +10 or +15 D) or negative (−5, −10, −15 D) lenses over one eye. All lens-wearing and fellow eyes were measured again 5 h after the lenses were fitted (n = 5 each group) as well as after 24 and 48 h of lens-wear.

In a separate short-term experiment, the effects of +1, +2 and +3 D lenses as well as plano lenses (n = 6 each group) were measured 1, 3, 5 and 24 h after lens fitting. This experiment covered the possibility that the lens compensation mechanism saturates at a relatively low defocus value and capitalised on the rapid significant choroidal thickening that characterizes the early response to positive lenses and the ability of our ulrasonography equipment to accurate measure these changes. In this event, we might expect to see defocus-dependent, proportional response rates only for these very low lens powers. Choroidal thickness changes elicited by negative lenses are necessarily small (a thin tissue is limited in the extent to which it can reduce its thickness), and thus results from an equivalent experiment with low power negative lenses were predicted to be inconclusive and this experiment not run.

Because our principal interest was in how lens power affected the rate of response to the lenses, only data from lens-treated eyes are shown, and rate of change analyses are also limited to lens-treated eyes. Because the eyes wearing positive lenses compensated more rapidly and thus more completely to the imposed defocus than those wearing negative lenses, we further examined the refractive error data of the former group to address the question of whether or not eyes emmetropise to idiosyncratic set-points.

B. Effects of lenses measured after repeated baseline measurements

If the emmetropisation controller produces a maximal output until an opposing error signal is encountered, this delay would cause the eye to overshoot its refractive end-point before reversing its direction of growth. To look for evidence of such overshoot in young chicks, refractive errors and axial dimensions were measured on the day of hatching (day 1), again on the following day (day 2), and 4 days later (day 6), after which right eyes were fitted with either +6 D lenses (n = 10) or −7 D lenses (n = 5). To avoid possible artefacts associated with repeated frequent measurement, we collected only one post-lens set of measurements, after 2 days of lens wear.

Results

The results from our first study imply that emmetropisation is guided primarily by the sign of defocus. Specifically, we found no consistent differences related to lens power in the initial rates of change in refractive error, choroidal thickness or axial length, although there were large differences related to the sign of the lenses worn. This was true for positive lenses, even when lens powers were kept low. In our second study we found that after 2 days of positive lens wear the refractive errors had changed by more than the power of the imposed lenses, that is, the eyes initially overcompensated for the defocus imposed by the lenses. The latter result implies that the eye continues to grow in the direction that compensates for the imposed defocus until the eye’s refractive error reverses. Thus at least for positive lenses, a bang-bang type of controller best fits with observed compensation patterns.

A. Effects of spectacle lens power & sign

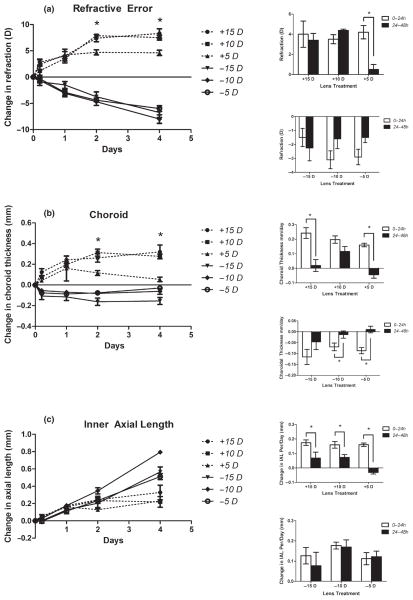

In the first study, the principal finding for eyes wearing our higher power lenses (−5, −10 and −15 D) is that the initial rates of change in refraction (Figure 2a), choroid thickness (Figure 2b) and inner axial length (Figure 2c) vary only with the sign of defocus, and not with the magnitude.

Figure 2.

Change in refractive error plotted as a function of lens wearing time for eyes fitted with one of 6 lenses ranging in power from −15 D to +15 D (Study A). The left panel shows changes in refractive error (a), choroidal thickness (b) and ocular length (c). Measurements made at the time of lens-fitting have been subtracted from all data shown. The bar graphs on the right of each panel show the changes over the first and second 24 h periods of lens wear. For all three parameters, initial rates of change are similar for eyes wearing lenses of the same sign; the curves representing eyes wearing the lowest power lenses level off before those wearing higher power lenses. The positive lens groups show larger choroidal thickness changes than the negative lens groups (b), whereas the negative lens groups shows larger and more enduring ocular elongation (c). The more rapid compensation for positive lenses reflects rapid choroidal thickening. * P < 0.05.

With the positive lenses, compensation to the imposed myopic defocus pushes refractions in the direction of increasing hyperopia. The three positive lens groups showed similar, rapid changes over the first 24 h. Their average change in refraction after 5 h of lens wear was +2.46 ± 0.50 D. The change was larger over the first 24 h of lens wear, i.e., +4.46 ± 0.50 D, equivalent to a rate of 0.13 D per h, with no significant difference between the groups (P = 0.36; Figure 2a). The +5 D lens group showed nearly complete compensation to the imposed defocus at this time and so thereafter the rate of change in refraction slowed for this group, while the +10 and + 15 D lens groups showed further increases in induced hyperopia between 24 and 48 h, similar in magnitude to the changes over the initial 24 h period.

With the negative lenses, significant myopic shifts in refractive error compared to baseline were observed after 5 h in both −10 and −15 D lens groups (−10 D lens: −1.40 ± 0.68 D, P = 0.022; −15 D lens: −1.63 ± 0.43 D, P = 0.04) but not in the −5 D lens group (0.10 ± 0.93 D, P = 0.23). However, after 24 h the refractions of all groups were significantly different from baseline measurements (−5 D lens: −2.10 ± 0.69 D, P = 0.005; −10 D lens: −3.20 ± 0.25 D, P < 0.001; −15 D lens: −2.625 D ± 0.25 D, P < 0.001), with no significant differences between them (P = 0.27). Nonetheless, refractive compensation to the negative lenses was much slower than that to the positive lenses, with eyes becoming myopic at a rate of 0.076 D per h over the first 48 h, with similar rates of change in all groups (P = 0.38).

Changes in choroidal thickness were principally responsible for compensatory refractive changes over the first day; thickening was seen with the positive lenses and thinning with the negative lenses (Figure 2b). With 5 to 15 D lenses, the choroids of all three positive lens-wearing groups thickened at approximately the same rate over the first 24 h (P = 0.64), to reach an average thickness of 120 ± 35 μm after 5 h and 233 ± 40 μm after 24 h. This trend was then reversed for the eyes wearing +5 D lenses, whose choroids began to thin, consistent with their near complete refractive compensation to the imposed defocus, to become significantly thinner compared those of eyes wearing +10 and +15 D lenses at both 2 and 4 day time-points (P = 0.005). Negative lens treatments induced early, significant choroidal thinning compared to baseline values, averaging −70 ± 15 μm of thinning after 5 h (P = 0.013) and −96 ± 46 μm at 24 h (P < 0.001). As with the positive lens treatments, most of the choroidal thickness changes occurred within the first 24 h of treatments.

Related changes in inner axial lengths (IAL) were identical across all lens groups (positive and negative) over the first 48 h, implying that the lenses were without scleral effects over this period, and contrasting with the rapid and sign-dependent choroidal changes over the same period. However, a significant reduction in the rate of axial elongation was recorded in all positive lens groups after 48 h (P = 0.006). For all three groups, the eyes continued to elongate over the first day (mean: 165 ± 41 μm per day), but elongation slowed by the second day (24.4 ± 25 μm per day), albeit to a lesser extent in the +5 D lens group compared to +10 and +15 D lens groups. Thus over the second day (24–48 h), the +10 and +15 D lens groups recorded an average elongation of 66.2 ± 10 μm per day compared to 72.1 ± 24 μm per day for the +5 D lens group; however this difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.15). In contrast, all three negative lens groups showed similar rates of IAL elongation, much larger than for the positive lens groups, over this same 48 h period (138 ± 94 μm per day).

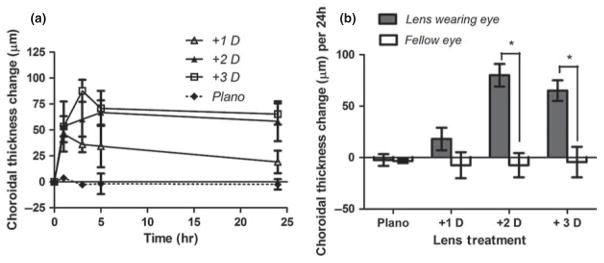

For eyes wearing very low power positive lenses (plano to +3 D), choroidal thickness changes provide the most sensitive measure of the necessarily small compensatory responses. Interestingly here, we found choroidal thickness changes over the monitoring period to vary with lens power (Mixed ANOVA analysis: F3,18 = 10.792; P < 0.0001). Further post hoc testing (Fischer’s Least Significant Difference) found no significant difference in the thickening responses of eyes wearing +2 and +3 D lenses after 24 h (80 ± 11 vs 65 ± 10 μm respectively, P = 0.35; Figure 3). On the other hand, the changes in the +1 D lens and plano lens groups were significantly less than those of the +2 D and +3 D lens groups (P < 0.01 in both cases) and not significantly different from each other (+1 D lens group, 18 ± 11 μm; plano group, 7 ± 3 μm; P = 0.21). Nonetheless, graphical analysis of the data suggested an early, transient thickening of choroid in eyes fitted with +1 D but not plano lenses. Thus in further analyses, we parsed the data, calculating a rate of change for each measurement interval (Table 1). This analysis revealed similar increases in choroidal thickness over the first hour with all three positive lenses, being in all cases significantly different from that recorded with the plano lens (P < 0.05; unpaired student’s t-test). Differences between the positive lens groups developed after the 1 h time-point; only the +3 D lens treated group showed continued choroidal thickening (P = 0.028); choroidal thickness stabilised in +2 D lens-treated eyes and began to reverse in +1 D lens-treated eyes. After 3 h, choroidal thickness had also stabilised in +3 D lens-treated eyes. We note however, there are inherent limitations to studies involving such low power lenses, as covered in later discussion.

Figure 3.

Choroidal changes over time for eyes wearing plano, +1, +2 and +3 D lenses; (a) total change over the monitoring period (b). The changes over 24 h with the +2 and +3 D lenses are similar to each other and significantly larger than those with the plano and +1 D lenses; however, the short-term (1 & 3 h) choroidal thickness changes with the +1 D lens are significantly larger than those with the plano lens.

Table 1.

Calculated rates of choroidal thickness change per hour after monocular low powered positive lenses were fitted to young chicks

| Time interval | Rate of choroid thickness change per hour (μm h−1)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plano | +1 D | +2 D | +3 D | |

| 0–1 h | −3.67 ± 2.3 | 46.0 ± 7.8 | 53.5 ± 9.9 | 53.3 ± 24.1 |

| 1–3 h | 0.5 ± 5.5 | −5 ± 2.5 | 3.4 ± 5.6 | 17.2 ± 3.5 |

| 3–5 h | −8.0 ± 5.7 | −0.8 ± 4.1 | 3.3 ± 2.4 | −0.8 ± 3.4 |

| 5–24 h | −0.5 ± 2.0 | −0.8 ± 10.9 | −0.4 ± 19.2 | −0.2 ± 10.1 |

To look for evidence that individual eyes have idiosyncratic refractive set-points to which they return after compensating for imposed optical defocus, we further analysed data from eyes wearing either +1, +2, +3, +5 or +10 D lenses, whose refractions had asymptoted. Asymptotic responses were judged both visually and by determining the rate of change in refractive error and choroid between the last two measurement time-points. These data were plotted as measured changes in refractive errors against the values that would be expected if lens compensation returned these eyes to their pre-lens refractions (Figure 4). Linear regression analysis of these data yielded a slope of 0.735 ± 0.056 and a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.88 (P = 0.19). Equivalent analysis using predictions based on absolute compensation, i.e. net refractive error of zero with lens in place, yielded a much weaker correlation (r = 0.03). Although not conclusive, these results are more consistent with the hypothesis that lens compensation is relative, that is, that eyes return to their pre-lens refractive states.

Figure 4.

Plot of observed changes in refractive error versus the changes predicted for relative compensation (compensation for only the lensimposed defocus) in eyes wearing +1 D, +2 D, +3 D, +5 D or +10 D lenses; data taken at time when refractions had asymptoted; see Figure 2. The regression line fit to the data (solid line) closely approximates perfect relative compensation, represented by the interrupted line (slope of unity).

In summary, the overall pattern of behaviour fits best with that of a bang-bang controller. However, we acknowledge that the data for negative lenses are less robust. Specifically, we cannot exclude the possibility that there is a range of low power lenses over which initial responses are proportional to lens powers. The upper limit of this range, if it exists, would be less than 2 D for positive lenses, i.e., less than 1 D outside the depth-of-focus of the chick eye.

B. Effects of lenses measured after repeated baseline measurements

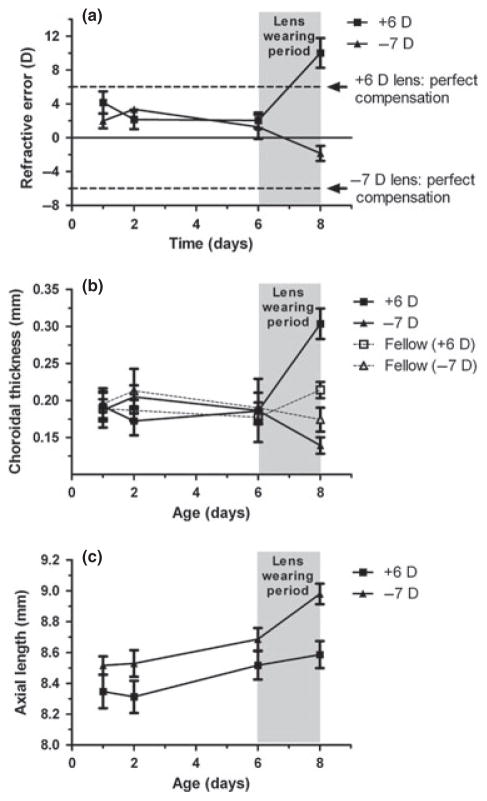

As noted earlier, if the emmetropisation controller produces a constant (maximal) output until an opposing error signal is encountered, as in the case of a bang-bang controller, this delay would cause the eye to overshoot its refractive end-point before reversing its direction of growth. In our second study, all the eyes were found to be moving slowly in the direction of emmetropia before the lenses were fitted (Figure 5a). Thus immediately before the lenses were fitted the means representing the refractive errors for lens-treated eyes and their fellows (+6 D and −7 D lens groups and two groups of fellow eyes) are tightly clustered. With the +6 D lenses, we expected nearly complete compensation after 2 days of lens wear, based on data from our first study. Instead this +6 D lens group overshot full compensation both in terms of ‘absolute emmetropia’ (compensation for both the lens power and the initial refractive error), and ‘relative compensation’ (compensation for the lens power only); the mean refractive error for this group was +9.4 ± 4.5 D, a change of 8.4 ± 4.9 D. On an individual basis, 7 of the 10 eyes wearing +6 D lenses overshot by both criteria. Furthermore, we observed overshooting in four of the six eyes within the group that exhibited relatively stable refractions prior to lens wear (i.e. recording a change of less than 2.4 D during the period from day 2 to day 6). This behaviour is consistent with that of a bang-bang controller. The eyes wearing −7 D lenses showed incomplete compensation and no overshooting, presumably because the rate of refractive compensation for negative lenses is much slower than for positive lenses. Thus while the refractions of the −7 D lens group shifted in the correct direction, opposite to that recorded for the +6 D lens group, the average change was about half as much (−3.4 ± 3.5 D).

Figure 5.

Mean refractive errors (a), choroidal thickness (b) and axial length (c) measured over time for eyes fitted with +6 D and −7 D lenses (Study B). Fellow eye choroidal thickness data is shown to illustrate yoking of the choroid response. The lens-wearing period is indicated by the shaded zone. The refractive errors of the two lens groups diverged over the 2 days of lens wear. The eyes fitted with +6 D lenses changed by more than 6 D over the 2 days, i.e., overcompensated; in contrast, this time period was not sufficient for full compensation for −7 D lenses. Arrows show values that would have been reached at 8 days, had perfect absolute compensation occurred. The changes in choroid thickness and in ocular elongation are in opposite directions for the eyes wearing positive and negative lenses. The untreated fellow eyes show choroidal responses similar to, but smaller than, the lens-treated eyes (b), implying interocular yoking.

Changes in both choroidal thickness and IAL contributed to the compensatory refractive changes of both the positive and negative lens groups (Figure 5b,c). If we consider only the nine birds that had apparently attained stable refractions over the pre-lens period (6 from the +6 D lens group, 3 from the −7 D lens group), we find: (1) in all eyes wearing positive lenses the choroids thickened during lens wear; in 2 of 3 eyes wearing negative lenses the choroids thinned, (2) in 5 of 6 eyes wearing +6 D lenses and in all three eyes wearing −7 D lenses the IALs changed in the compensatory direction, and (3) individual eyes maintained stable refractions over the pre-lens period by different combinations of changes in these two ocular components.

This study also yielded further evidence of ‘interocular yoking.’ Although the two eyes of chicks are generally regarded as responding independently to visual manipulations, there are many published reports of monocular treatments having effects on the untreated fellow eyes.2,22–30 In this second study, the choroids of the untreated eyes showed changes over the 2-day lens-wearing period in the same direction as their fellow lens-wearing eyes, albeit of reduced magnitude (approximately 70%; Figure 5b). Based on the assumption that such yoking acts in both directions, we speculate that the degree of change in the lens-wearing eyes would have been constrained by the untreated fellow eye, and thus less than expected if both eyes wore similar lenses.

Discussion

We have presented two sets of data suggesting that the emmetropisation controller responsible for lens compensation behaves more like a bang-bang controller than a proportional controller: (1) Across a wide range of lens powers, including very low positive powers, the initial ocular responses depend on the sign, not the power of the lens, and (2) eyes wearing positive lenses overshoot full compensation. In the following discussion, we review the strength of the evidence and consider its biological significance.

Does lens power influence the rate of lens compensation? Although we found similar initial rates of compensation over a wide range of powers of ‘same-sign’ lenses (5–15 D), the conclusion that only the sign of the lens influences the initial rate of compensation must be qualified. If either the error-sensing stage at the input, or the growth-influencing stage at the output, saturate at a low level of defocus (say 2 D), there might be a range below this, not represented in our negative lens data, over which the rate of compensation is proportional to the power of the imposed lens. Below we also discuss two potential confounders for our experiment involving low power, positive lenses.

The data from low power lenses would have been more definitive had we verified that the refractions had stabilised before the lenses were put on, a precaution not necessary for high power lenses. For example, if one imposes a + 15 D lens, one can be assured that the induced compensatory changes will dominate the subsequent course of emmetropisation even if the eye begins a few dioptres hyperopic or myopic relative to the end-point of its ongoing emmetropisation. On the other hand, if an eye is +4 D hyperopic and we fit a + 3 D spectacle lens, two outcomes are possible. If the eye is already near its refractive set-point (e.g., if that were near +4 D), the spectacle lens would provoke lens compensation, as in the +15 D lens example. If, however, the spectacle lens serves to bring the eye closer to its refractive set-point (e.g., if that were +1 D), it will eliminate the error signal for emmetropisation and hence no compensatory changes in ocular growth would be expected. This phenomenon by itself would weaken the measured compensation to low power lenses, with the effect of making lens compensation appear proportional to lens power.

A second and perhaps more important complication of experiments with low power lenses is that less time will be required to achieve full compensation compared to moderate to high power lenses, even if the initial responses rates were the same. Kee,31 has shown that the choroid can thin for negative lenses within 1 h. In a bid to account for such rapid changes, we included multiple early measurement time-points in our study using low power positive lenses, i.e., 1, 3 and 5 h after the lenses were fitted. Our data confirmed detectible early choroidal thickening with our +1 D lens as well with +2 and +3 D lenses, with this thickening response being more sustained with the +3 D lens. Furthermore, the apparent power-dependent differences in choroidal responses after 24 h of lens wear can be mostly explained as a product of the more transient nature of the changes induced by the lowest power (+1 D) lens. As noted in the methods, we chose not to include a parallel experiment involving low power negative lenses. Because of the limited ability of thin tissues to thin further, it would not have been possible to distinguish between saturation of choroidal responses and a thinning artefact. For example, a reduction of thickness by 100 μm, i.e., by about 50%, represents an approximate 1.5 D change in refractive error.2

Of course there is an upper limit to how much lens-induced defocus can be compensated, even in chicks. As shown in Figure 1, above +30 D the degree of compensation observed decreases, and above +50 D the eye becomes myopic rather than hyperopic, presumably because the defocus is so great that it induces form-deprivation myopia.32 In mammals and primates, the range over which lens compensation occurs is much smaller, particularly on the positive lens side.33,34–37

What can we infer from the properties of the emmetropisation controller, i.e., what determines the all-or-none response of the emmetropisation system? It could reflect activity of the detector at the input stage, which senses the refractive error, being saturated even by low power lenses. Alternatively, it could result from output having only two states. Because there is evidence suggesting that the choroidal and ocular elongation (scleral) responses, although usually in concert, are independently controlled,38,39 either response could be limited at either the input or output. From the available data, these possibilities cannot be distinguished. 39

The performance of any negative feedback control system is determined by its sensitivity, dead-zone (the region of input that produces no output), and dynamics (the time relationship between changes in input and output). The interaction among these parameters determines its temporal response characteristics, including the pattern of oscillations around the set-point. What can we infer about the sensitivity and dead-zone of the emmetropisation controller from our results? From the choroidal thickening observed in response to the low power positive lenses (see above) we can say that the size of the dead-zone or threshold sensitivity is less than 1 D, as the +1 D lens treatment elicited a typical choroidal compensatory response, albeit transient. It has previously been found that an imposed 2 D interocular difference using +1 and −1 D lenses fitted to the two eyes of individual chicks elicits compensation, a finding consistent with an estimated depth-of-focus of the chick eye of 0.8 D for a 2 mm pupil.40 Therefore our findings are consistent with the notion that the depth-of-focus governs the performance of the emmetropisation mechanism, although we note that 1 D of defocus would be only just outside the depth-of-focus. We speculate that there may be more than one defocus signal used in guiding and fine-tuning the emmetropisation response and the exquisitely sensitive choroidal mechanism may reflect the influence of just one. The role of longitudinal chromatic aberration as a defocus cue in emmetropisation has been the subject of recent investigations by Rucker and Wallman; 41,42 it may represent the primary defocus cue when the image plane is within the eye’s classically-defined depth-of-focus.

With respect to the dynamics of the emmetropisation system, the ‘overshoot’ of several dioptres in refractive error observed in our second study (Figure 5) suggest that there is a substantial lag between the time when the visual input (the manifest refractive error) reverses and the rate of ocular elongation changes. Such a lag would create a refractive ‘momentum’ that limits how quickly the emmetropisation controller can respond to a reversal of the error signal. It is also consistent with other findings showing only sluggish changes in ocular (scleral) length.31 Because refractive overshooting is not a consistent finding in our studies, we are inclined to suspect that typical measurement protocols, i.e., involving repeatedly measuring animals over relatively short time intervals, alter lens compensation. Specifically, any slowing of the rate of compensation resulting from such interventions might be expected to reduce the likelihood of overshooting.

What is the relationship between ‘experimental emmetropisation’, as reflected in lens compensation and natural emmetropisation? If the delay before changes in ocular elongation take place causes overshoot during lens compensation, what accounts for the apparent stability of refractions in eyes that are not compensating for lenses (e.g., as seen in the first phase of our second study)? In other words, why would not the compensation for a small naturally occurring refractive errors also result in a large overshoot? Our data and those of others show that the choroid can respond in either direction in a matter of hours, much faster than the changes in ocular elongation.1,31,38,43 Because of this difference in response time, we conjecture that small changes in refractive error are normally quickly reduced by changes in choroidal thickness, so that the stimulus for altered ocular elongation is short-lived. Once the small change in ocular elongation takes place, if it is not sufficient to compensate for the pre-existing refractive error, the process starts over. By this means small refractive errors could be compensated for with minimal overshoot. Large changes in refractive error, however, such as those imposed by more powerful defocusing lenses, cannot be so effectively compensated for by the choroid alone and thus the stimulus for altered ocular elongation is more enduring. Once the rate of elongation changes, the change can persist for several days after the visual input reverses,44 resulting in refractive over-compensation.

We propose that the principal function of the choroid in emmetropisation is to improve the dynamics of the response and minimize overshooting during normal emmetropisation. In the case of the chick eye, which grows so fast, the large capacity of the choroid to change its thickness to positive lenses serves to buffer the refractive error change that would otherwise emerge in the day or two required for the rate of ocular elongation to change. In the more slowly growing mammalian and primate eyes, the observed smaller amplitudes of choroidal changes36,45–47 would be adequate.

Toward what set-point does emmetropisation go? One of the important issues in emmetropisation is that of calibration. How does an individual eye determine where emmetropia lies? If the error signals used provided an absolute measure of emmetropia, then all eyes would emmetropise toward that value. On the other hand, if absolute calibration is not possible, at least early in life, individual eyes might emmetropise toward their own idiosyncratic refractions. In monkeys repeated measurements over many weeks confirm that young eyes stabilize at idiosyncratic refractions.15 The observation that young tree shrews became nearly emmetropic with low power (+4 D) positive lenses in place is more difficult to interpret, as the natural set-point of emmetropisation in the tree shrew appears close to absolute emmetropia.37 Finally, the abnormal refractions seen in chicks reared in constant light48–50 and in animals with their optic nerve cut,51–53 suggest that emmetropisation need not have a set-point of zero. Although there are other plausible interpretations of these observations, for example, emmetropisation may be fundamentally altered by the imposed conditions, in fact, optic-nerve-sectioned chicks can compensate for lenses and return to their abnormal pre-lens refractions.52 Perhaps when the nature of the error signals is understood, this puzzle will be solved.

How can we reconcile the idiosyncratic refractive set-points in young animals with the nearly uniform refractions of adult animals?15,54 For example, the refractions of 8 week-old chickens are clustered much more tightly about emmetropia than those of younger chickens.54 The passive emmetropisation that results from larger eyes having smaller refractive errors than identically shaped smaller eyes19 can at least partly explain this difference. It is further possible that there is a second active emmetropisation mechanism, either much slower or acting later in life, that supplements both the latter passive mechanism and the early active emmetropisation mechanism studied here. Or perhaps there is just one active emmetropisation mechanism whose dynamic range becomes more constrained with increasing age, as suggested by lens compensation data collected from older animals.55,56

In conclusion, the observed response characteristics of sign- but not magnitude-dependence, and initial overshooting of the end-point for positive lenses are characteristic of a bang-bang controller although unresolved is whether this behaviour can be generalize to lower power negative lenses and whether this behaviour reflects input or output. Our results also leave unresolved the mechanism(s) by which the sign is decoded

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant NIH EY-R01-2392.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest and have no proprietary interest in any of the materials mentioned in this article.

References

- 1.Wallman J, Wildsoet C, Xu A, et al. Moving the retina: choroidal modulation of refractive state. Vision Res. 1995;35:37–50. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)e0049-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wildsoet C, Wallman J. Choroidal and scleral mechanisms of compensation for spectacle lenses in chicks. Vision Res. 1995;35:1175–1194. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00233-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu X, Park TW, Winawer J, Wallman J. In a matter of minutes, the eye can know which way to grow. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2238–2241. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gwiazda JE, Hyman L, Norton TT, et al. Accommodation and related risk factors associated with myopia progression and their interaction with treatment in COMET children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2143–2151. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weizhong L, Zhikuan Y, Wen L, Xiang C, Jian G. A longitudinal study on the relationship between myopia development and near accommodation lag in myopic children. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2008;28:57–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2007.00536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mutti DO, Sinnott LT, Mitchell GL, et al. Relative peripheral refractive error and the risk of onset and progression of myopia in children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:199–205. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charman WN, Radhakrishnan H. Peripheral refraction and the development of refractive error: a review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2010;30:321–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2010.00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung GK, Ciuffreda KJ. Model of human refractive error development. Curr Eye Res. 1999;19:41–52. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.19.1.41.5343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hung GK, Ciuffreda KJ. A unifying theory of refractive error development. Bull Math Biol. 2000;62:1087–1108. doi: 10.1006/bulm.2000.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackie CA, Howland HC. An extension of an accommodation and convergence model of emmetropisation to include the effects of illumination intensity. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1999;19:112–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Del Toro V, Parker SR. Principles of Control Systems Engineering. ix. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1960. p. 686. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tepelus TC, Schaeffel F. Individual set-point and gain of emmetropisation in chickens. Vision Res. 2010;50:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norton TT, Siegwart JT, Jr, Amedo AO. Effectiveness of hyperopic defocus, minimal defocus, or myopic defocus in competition with a myopiagenic stimulus in tree shrew eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:4687–4699. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley DV, Fernandes A, Lynn M, Tigges M, Boothe RG. Emmetropisation in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta): birth to young adulthood. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:214–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith EL, III, Hung LF. The role of optical defocus in regulating refractive development in infant monkeys. Vision Res. 1999;39:1415–1435. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00229-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith EL, III, Hung LF. Form-deprivation myopia in monkeys is a graded phenomenon. Vision Res. 2000;40:371–381. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(99)00184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gwiazda J, Thorn F, Bauer J, Held R. Emmetropization and the progression of manifest refraction in children followed from infancy to puberty. Clin Vis Sci. 1993;8:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wildsoet CF, Wallman J. Is the rate of lens compensation proportional to the degree of defocus? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38(ARVO Suppl):S461. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallman J, Adams JI. Developmental aspects of experimental myopia in chicks: susceptibility, recovery and relation to emmetropization. Vision Res. 1987;27:1139–1163. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glickstein M, Millodot M. Retinoscopy and eye size. Science. 1970;168:605–606. doi: 10.1126/science.168.3931.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nickla DL, Wildsoet C, Wallman J. Visual influences on diurnal rhythms in ocular length and choroidal thickness in chick eyes. Exp Eye Res. 1998;66:163–181. doi: 10.1006/exer.1997.0420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buck C, Schaeffel F, Simon P, Feldkaemper M. Effects of positive and negative lens treatment on retinal and choroidal glucagon and glucagon receptor mRNA levels in the chicken. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:402–409. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegwart JT, Jr, Norton TT. The time course of changes in mRNA levels in tree shrew sclera during induced myopia and recovery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:2067–2075. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schippert R, Brand C, Schaeffel F, Feldkaemper MP. Changes in scleral MMP-2, TIMP-2 and TGFbeta-2 mRNA expression after imposed myopic and hyperopic defocus in chickens. Exp Eye Res. 2006;82:710–719. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao H, Frost MR, Siegwart JT, Jr, Norton TT. Patterns of mRNA and protein expression during minus-lens compensation and recovery in tree shrew sclera. Mol Vis. 2011;17:903–919. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rucker FJ, Zhu X, Bitzer M, Schaeffel F, Wallman J. Interocular interactions in lens compensation: yoking and anti-yoking. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:E-abstract 3931. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McBrien NA, Norton TT. The development of experimental myopia and ocular component dimensions in monocularly lid-sutured tree shrews (Tupaia belangeri) Vision Res. 1992;32:843–852. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(92)90027-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu X, Wallman J. Temporal properties of compensation for positive and negative spectacle lenses in chicks. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:37–46. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wildsoet CF. Bidirectional, optical sign-dependent regulation of BMP2 gene expression in chick retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:6072–6080. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-9917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hammond DS, Wildsoet CF. Lens defocus-induced changes in the ocular somatostatin signaling pathway of chicks. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:3429. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kee CS, Marzani D, Wallman J. Differences in time course and visual requirements of ocular responses to lenses and diffusers. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:575–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nevin ST, Schmid KL, Wildsoet CF. Sharp vision: a prerequisite for compensation to myopic defocus in the chick? Curr Eye Res. 1998;17:322–331. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.17.3.322.5220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hung LF, Crawford ML, Smith EL. Spectacle lenses alter eye growth and the refractive status of young monkeys. Nat Med. 1995;1:761–765. doi: 10.1038/nm0895-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graham B, Judge SJ. The effects of spectacle wear in infancy on eye growth and refractive error in the marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) Vision Res. 1999;39:189–206. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(98)00189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whatham AR, Judge SJ. Compensatory changes in eye growth and refraction induced by daily wear of soft contact lenses in young marmosets. Vision Res. 2001;41:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howlett MH, McFadden SA. Spectacle lens compensation in the pigmented guinea pig. Vision Res. 2009;49:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegwart JT, Jr, Norton TT. Binocular lens treatment in tree shrews: effect of age and comparison of plus lens wear with recovery from minus lens-induced myopia. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winawer J, Wallman J. Temporal constraints on lens compensation in chicks. Vision Res. 2002;42:2651–2668. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nickla DL, Schroedl F. Parasympathetic influences on emmetropisation in chicks: evidence for different mechanisms in form deprivation vs negative lens-induced myopia. Exp Eye Res. 2012;102:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmid KL, Wildsoet CF. The sensitivity of the chick eye to refractive defocus. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1997;17:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rucker FJ, Wallman J. Chick eyes compensate for chromatic simulations of hyperopic and myopic defocus: evidence that the eye uses longitudinal chromatic aberration to guide eye-growth. Vision Res. 2009;49:1775–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rucker FJ, Wallman J. Chicks use changes in luminance and chromatic contrast as indicators of the sign of defocus. J Vis. 2012;12:23. doi: 10.1167/12.6.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nickla DL. Transient increases in choroidal thickness are consistently associated with brief daily visual stimuli that inhibit ocular growth in chicks. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:951–959. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winawer J, Zhu X, Choi J, Wallman J. Ocular compensation for alternating myopic and hyperopic defocus. Vision Res. 2005;45:1667–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Troilo D, Nickla DL, Wildsoet CF. Choroidal thickness changes during altered eye growth and refractive state in a primate. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1249–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hung LF, Wallman J, Smith EL., III Vision-dependent changes in the choroidal thickness of macaque monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1259–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Read SA, Collins MJ, Sander BP. Human optical axial length and defocus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:6262–6269. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li T, Howland HC, Troilo D. Diurnal illumination patterns affect the development of the chick eye. Vision Res. 2000;40:2387–2393. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li T, Troilo D, Glasser A, Howland HC. Constant light produces severe corneal flattening and hyperopia in chickens. Vision Res. 1995;35:1203–1209. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(94)00231-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Padmanabhan V, Shih J, Wildsoet CF. Constant light rearing disrupts compensation to imposed- but not induced-hyperopia and facilitates compensation to imposed myopia in chicks. Vision Res. 2007;47:1855–1868. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wildsoet CF, McFadden SA. Optic nerve section does not prevent form deprivation-induced myopia or recovery from it in the mammalian Eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:E-Abstract 1737. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wildsoet C. Neural pathways subserving negative lens-induced emmetropisation in chicks–insights from selective lesions of the optic nerve and ciliary nerve. Curr Eye Res. 2003;27:371–385. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.27.6.371.18188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Troilo D, Gottlieb MD, Wallman J. Visual deprivation causes myopia in chicks with optic nerve section. Curr Eye Res. 1987;6:993–999. doi: 10.3109/02713688709034870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wallman J, Adams JI, Trachtman JN. The eyes of young chickens grow toward emmetropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981;20:557–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norton TT, Amedo AO, Siegwart JT., Jr The effect of age on compensation for a negative lens and recovery from lens-induced myopia in tree shrews (Tupaia glis belangeri) Vision Res. 2010;50:564–576. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wildsoet C, Anchong R, Mannasse J, Troilo D. Susceptibility to experimental myopia declines with age in the chick. Optom Vis Sci. 1998;75(Suppl):265. [Google Scholar]