Abstract

Nicotine exposure in adolescence produces lasting changes in subsequent behavioral responses to addictive agents. We gave nicotine to adolescent rats (postnatal days PN30-47), simulating plasma levels in smokers, and then examined the subsequent effects of nicotine given again in adulthood (PN90-107), focusing on cerebrocortical serotonin levels and utilization (turnover) as an index of presynaptic activity of circuits involved in emotional state. Our evaluations encompassed responses during the period of adult nicotine treatment (PN105) and withdrawal (PN110, PN120, PN130), as well as long-term changes (PN180). In males, prior exposure to nicotine in adolescence greatly augmented the increase in serotonin turnover evoked by nicotine given in adulthood, an interaction that was further exacerbated during withdrawal. The effect was sufficiently large that it led to significant depletion of serotonin stores, an effect that was not seen with nicotine given alone in either adolescence or adulthood. In females, adolescent nicotine exposure blunted or delayed the spike in serotonin turnover evoked by withdrawal from adult nicotine treatment, a totally different effect from the interaction seen in males. Combined with earlier work showing persistent dysregulation of serotonin receptor expression and receptor coupling, the present results indicate that adolescent nicotine exposure reprograms future responses of 5HT systems to nicotine, changes that may contribute to life-long vulnerability to relapse and re-addiction.

Keywords: Adolescence, Nicotine, Serotonin, Sex differences, Withdrawal

INTRODUCTION

The standard view of developmental neurotoxicity is that the immature brain is more susceptible to damage by neuroactive drugs and chemicals because it is in the process of forming structures and circuits (Barone et al., 2000; Cuomo, 1987; Grandjean and Landrigan, 2006). Yet, at the same time, the heightened plasticity of the developing brain allows it to offset damage more readily than in the mature brain, in part because of the ability to generate new neurons. This explains why, in some circumstances, normal function can be maintained even after extreme damage early in life (Lorber, 1981; Priestley and Lorber, 1981). Likewise, it clarifies why adverse neurodevelopmental effects of maternal cigarette smoking tend to be greater than those from cocaine; cocaine is used in discrete episodes, allowing for recovery and neuroregeneration in between exposures, whereas fetal nicotine exposure from cigarette use is sustained throughout pregnancy (Coles, 1993; Slotkin, 1998). Neural plasticity in the immature brain is highly influenced by patterns of synaptic activity because neurotransmitters act as morphogens, controlling neuronal cell replication, differentiation and circuit formation (Dreyfus, 1998; Lauder, 1985; Whitaker-Azmitia, 1991). For normal development to proceed, synaptic stimulation has to follow discrete spatial and temporal patterns, with a specified level of signal intensity (Slotkin, 2004, 2008). At the same time, it is this aspect that leaves the brain vulnerable to neuroactive drugs and chemicals that disrupt brain development, not by causing outright damage, but rather by disrupting the spatiotemporal organization of neurotransmitter signals, leading to abnormalities at the functional, rather than the gross structural level, essentially “plasticity gone awry.”

It is now evident that the development and programming of synaptic circuits continues into adolescence, well past the completion of gross brain structure (Rakic et al., 1994; Slotkin, 2002, 2008; Spear, 2000; Walker et al., 1999). This is especially important in light of the fact that adolescence is the likely point for initiation of cigarette smoking. Studies over the past few years show that the adolescent brain is much more responsive to nicotine than the adult with regard to both synaptic and behavioral responses (Adriani et al., 2003, 2004; Faraday et al., 2001, 2003; Klein, 2001; Levin, 1999; Slawecki and Ehlers, 2002; Slawecki et al., 2003; Slotkin, 2002, 2008; Trauth et al., 2000b). More importantly, in smokers, adolescent nicotine exposure promotes future addiction liability and reduces the likelihood of being able to quit (Chen and Millar, 1998). In fact, nicotine exposure in adolescence affects the subsequent adult responses to a wide variety of other addictive drugs (Adriani et al., 2006; Bracken et al., 2011; Hutchison and Riley, 2008; Imad Damaj et al., 2009; Kelley and Middaugh, 1999; Klein, 2001; Marco et al., 2006; Rinker et al., 2011; Santos et al., 2009). In our earlier work, we explored some of the mechanisms underlying this reprogramming and found major contributions from effects on cerebrocortical serotonergic (5HT) pathways involved in emotional behaviors (Slotkin, 2002; Slotkin et al., 2006, 2007a; Slotkin and Seidler, 2007, 2009; Xu et al., 2001, 2002). This is particularly important in light of the close connection between tobacco addiction and depressive disorders: adolescent tobacco use is highly correlated with depression (Goodman and Capitman, 2000; Patten et al., 2000; Wu and Anthony, 1999), and depressive symptoms exacerbated by nicotine withdrawal contribute to the failure of therapies for smoking cessation (Colby et al., 2000; Salin-Pascual et al., 1995; Tsoh et al., 2000), especially in adolescent smokers (Colby et al., 2000; Hurt et al., 2000). Our findings identified essentially permanent changes in the expression of 5HT receptors associated with depression, as well as the 5HT transporter, which is the major target for antidepressant therapy (Slotkin et al., 2006, 2007a; Slotkin and Seidler, 2009; Xu et al., 2001, 2002); further, we showed that adolescent nicotine exposure altered the responses of these synaptic proteins to nicotine given subsequently in adulthood (Slotkin and Seidler, 2009).

The changes in receptor or transporter expression evoked by adolescent nicotine treatment can represent primary reprogramming of synaptic function, or alternatively could be adaptive responses to underlying defects in presynaptic activity; for example, receptor upregulation could be compensatory for a reduction in presynaptic input, essentially restoring synaptic function to normal. In the current study, we resolved this issue by monitoring 5HT levels and utilization (turnover) so as to assess presynaptic activity. We contrasted the effects of adolescent nicotine treatment with those obtained for nicotine in adulthood, and then evaluated how adolescent exposure reprograms the response to subsequent adult nicotine treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and nicotine treatments

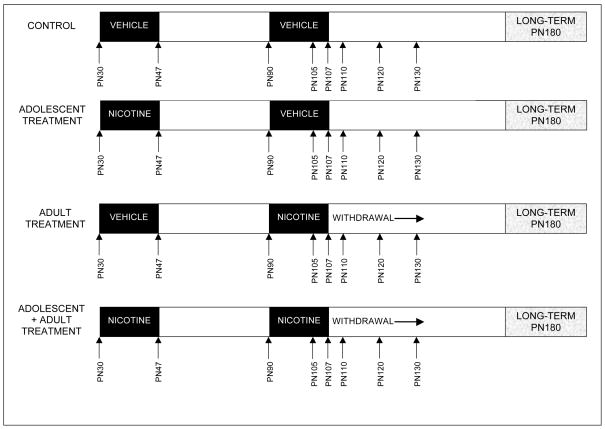

All procedures utilized tissues that were archived from earlier studies and maintained frozen at −45° C, so that no additional animals were actually used for this study. Details of animal husbandry, institutional approvals, maternal and litter characteristics, and growth curves, have all been presented in earlier work from the original animal cohorts (Slotkin et al., 2008a, b; Slotkin and Seidler, 2009). Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Raleigh, NC) were housed individually and allowed free access to food and water. There were four treatment groups (shown schematically in Fig. 1): controls (adolescent vehicle + adult vehicle), adolescent nicotine treatment (adolescent nicotine + adult vehicle), adult nicotine administration (adolescent vehicle + adult nicotine), and those receiving the combined treatment (adolescent nicotine + adult nicotine). On postnatal day (PN) 30, each rat was quickly anesthetized with ether, a 2 × 2 cm area on the back was shaved, and an incision was made to permit subcutaneous insertion of a type 1002 Alzet osmotic minipump (Durect Corp., Cupertino, CA). Pumps were prepared with nicotine bitartrate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) dissolved in bacteriostatic water (Abbott Laboratories, N. Chicago, IL), to deliver an initial dose rate of 6 mg/kg of nicotine (calculated as free base) per day. The incision was closed with wound clips and the animals were permitted to recover in their home cages. Control animals were implanted with minipumps containing only the water and an equivalent concentration of sodium bitartrate. It should be noted that the pump, marketed as a 2-week infusion device, actually takes 17.5 days to be exhausted completely (information supplied by the manufacturer) and thus the nicotine infusion terminates during PN47; we have confirmed exhaustion of the pumps at the predicted time by direct measurement of plasma nicotine and cotinine levels (Trauth et al., 2000a). Plasma nicotine levels achieved with this administration model resemble those seen in typical smokers (25 ng/ml) as characterized previously (Trauth et al., 2000a).

Figure 1.

Schematic of nicotine treatment regimens and sampling times.

On PN90, each animal was then implanted with a type 2ML2 minipump as already described, again set to deliver either vehicle or nicotine at an initial dose rate of 6 mg/kg per day, with the infusion terminating during PN107. Studies were conducted at four time points, one during adult nicotine administration (PN105), three during the posttreatment withdrawal period (PN110, PN120, PN130) and a final determination at six months of age (PN180). Animals were decapitated and the cerebral cortex was dissected (Slotkin et al., 2007a), frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −45°C until assayed. For each treatment group, 12 animals were examined at each age point, equally divided into males and females.

5HT concentration and turnover

Tissues were thawed and homogenized in ice-cold 0.1 M perchloric acid and sedimented for 20 min at 40,000 × g. The supernatant solution was collected and aliquots were used for analysis of 5HT and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5HIAA) by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (Xu et al., 2001). Concurrently-run standards were used to calculate the regional concentrations. Transmitter turnover was calculated as the 5HIAA/5HT ratio.

Data Analysis

To avoid type I statistical errors that might result from repeated testing of the global data set, we first performed a global ANOVA, incorporating all the variables (adolescent treatment, adult treatment, age, sex) and both dependent measures (5HT concentration and turnover), considered as repeated measures because both values arise from the same samples); data were log-transformed because of heterogeneous variance between the two dependent measures. Lower-order ANOVAs were then run according to the main treatment effects and interactions of treatment with the other variables. Where appropriate, this was followed by post hoc comparisons of treatment groups, using Fisher’s Protected Least Significant Difference; however, where treatment effects did not interact with other variables only the main effect was recorded without testing of individual differences. Significance was assumed at the level of p < 0.05.

Data are presented as means and standard errors. To facilitate comparisons, the effects of adult nicotine administration and withdrawal are shown as the percentage change from the corresponding basal values (i.e. values for the control group or adolescent nicotine alone), but statistical comparisons were made on the original data, which are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

5HT and 5HIAA Concentrations (mean ± SE)

| Age | Measure | Male | Female | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Adolescent Nicotine | Adult Nicotine | Adolescent + Adult Nicotine | Control | Adolescent Nicotine | Adult Nicotine | Adolescent + Adult Nicotine | ||

| 105 | 5HT* | 301 ± 6 | 303 ± 14 | 300 ± 17 | 277 ± 11 | 296 ± 17 | 268 ± 12 | 302 ± 17 | 276 ± 16 |

| 5HIAA* | 208 ± 8 | 199 ± 12 | 206 ± 8 | 213 ± 8 | 225 ± 5 | 233 ± 17 | 225 ± 10 | 222 ± 11 | |

| 5HIAA/5HT | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 0.66 ± 0.03 | 0.69 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.05 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | |

| 110 | 5HT* | 293 ± 15 | 341 ± 29 | 288 ± 15 | 263 ± 5 | 300 ± 16 | 301 ± 19 | 262 ± 12 | 301 ± 10 |

| 5HIAA* | 216 ± 8 | 235 ± 10 | 224 ± 12 | 215 ± 9 | 230 ± 16 | 250 ± 12 | 253 ± 15 | 242 ± 12 | |

| 5HIAA/5HT | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 0.78 ± 0.04 | 0.82 ± 0.02 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | |

| 120 | 5HT* | 324 ± 30 | 396 ± 48 | 314 ± 7 | 277 ± 11 | 313 ± 11 | 319 ± 8 | 298 ± 11 | 283 ± 42 |

| 5HIAA* | 224 ± 9 | 234 ± 13 | 244 ± 7 | 232 ± 5 | 261 ± 5 | 260 ± 9 | 260 ± 10 | 251 ± 16 | |

| 5HIAA/5HT | 0.71 ± 0.05 | 0.62 ± 0.06 | 0.78 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.80 ± 0.03 | 0.87 ± 0.02 | 0.91 ± 0.07 | |

| 130 | 5HT* | 282 ± 20 | 276 ± 14 | 256 ± 23 | 240 ± 21 | 251 ± 22 | 274 ± 16 | 297 ± 37 | 264 ± 30 |

| 5HIAA* | 185 ± 11 | 173 ± 3 | 172 ± 8 | 188 ± 6 | 204 ± 12 | 209 ± 7 | 219 ± 6 | 208 ± 9 | |

| 5HIAA/5HT | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 0.70 ± 0.06 | 0.82 ± 0.09 | 0.84 ± 0.07 | 0.78 ± 0.06 | 0.79 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.08 | |

| 180 | 5HT* | 332 ± 9 | 322 ± 18 | 330 ± 7 | 338 ± 16 | 350 ± 9 | 325 ± 9 | 303 ± 14 | 323 ± 16 |

| 5HIAA* | 209 ± 7 | 230 ± 21 | 247 ± 10 | 271 ± 9 | 267 ± 7 | 251 ± 12 | 231 ± 12 | 263 ± 10 | |

| 5HIAA/5HT | 0.63 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.04 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.80 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 0.79 ± 0.04 | 0.77 ± 0.04 | 0.81 ± 0.03 | |

ng/g

RESULTS

The global, repeated-measures ANOVA incorporating all factors (adolescent treatment, adult treatment, sex, age) and both dependent measures (5HT concentration, 5HT turnover) confirmed that adolescent nicotine changed the response to nicotine administered in adulthood, and further, that the interaction was sex- and age-selective, and differed between the two dependent measures: p < 0.05 for adolescent nicotine × adult nicotine × sex × age, p < 0.05 for adolescent nicotine × adult nicotine × measure. In addition, the effects of adult nicotine administration by itself showed the same interactions with sex and age: p < 0.05 for adult nicotine × sex × age, p < 0.0002 for adult nicotine × measure, p < 0.05 for adult nicotine × sex × measure. Accordingly, we then performed separate analyses for 5HT concentration and turnover, evaluating the effects of adult nicotine administration with and without the prior adolescent nicotine treatment. We calculated the results first as “basal values,” representing the longitudinal effects of adolescent nicotine administration followed by vehicle in adulthood; then we determined the changes caused by nicotine given in adulthood, as a percentage of the basal values for the respective pretreatment group (adolescent vehicle, adolescent nicotine).

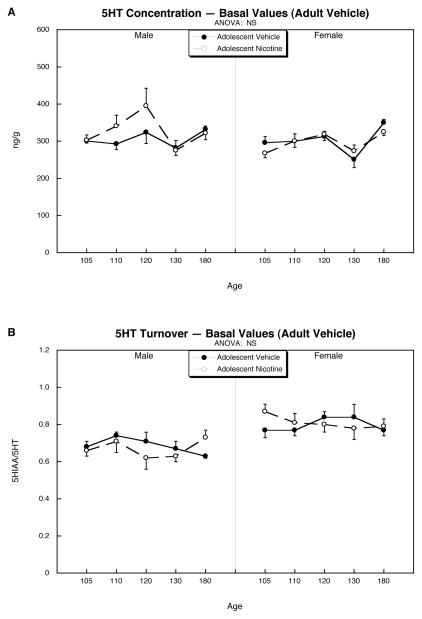

By itself, adolescent nicotine treatment evoked no significant changes in 5HT levels or turnover in adult throughout the course of PN105 to PN180 (Figure 2). When nicotine was given in adulthood (PN90 to PN107), animals that had not received prior exposure in adolescence showed little or no effect on the cerebrocortical 5HT concentration either during treatment or withdrawal (Fig. 3A). In contrast, males who had been exposed to nicotine in adolescence showed a profound decrement in 5HT concentration triggered by withdrawal from adult nicotine treatment, an effect that was not seen in females. Levels returned to normal between PN130 and PN180.

Figure 2.

Effects of adolescent nicotine administration on 5HT concentrations (A) and turnover (B). Animals received vehicle or nicotine from PN30-47 and then were implanted in adulthood with minipumps delivering vehicle from PN90-107. Data represent means and standard errors. Multivariate ANOVA (factors of treatment, sex, age) indicated no significant effects of nicotine or interaction of nicotine with the other variables; accordingly, no lower-order tests were performed. These data then provided the basal values for comparisons of the effects of adult nicotine administration and withdrawal shown in Figure 3. Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

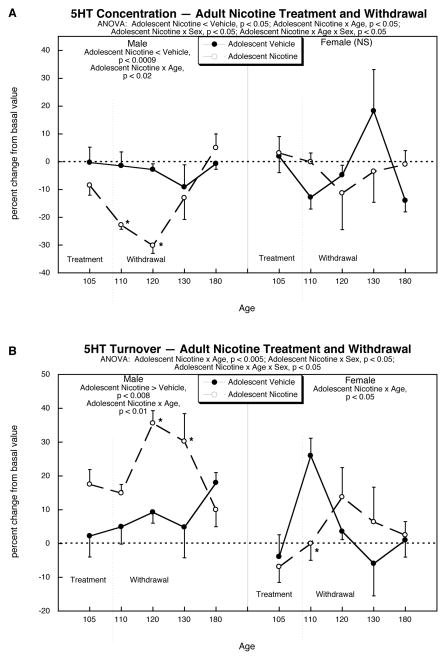

Figure 3.

Effects of adult nicotine administration and withdrawal in animals with or without prior exposure to nicotine in adolescence: (A) 5HT concentrations, (B) 5HT turnover. Data represent means and standard errors, shown as the percent change from the corresponding basal values given in Figure 2. ANOVA at the top of each panel gives the result of multivariate comparisons incorporating all factors (adolescent treatment, sex, age). Because nicotine treatment interacted with sex, lower-order tests are shown separately for males and females. Where a nicotine × age interaction was detected in the lower-order test, asterisks show the individual ages where the response to adult nicotine administration differed significantly between the group given adolescent nicotine vs. adolescent vehicle. Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

Likewise, prior adolescent nicotine exposure had a major effect on the response of 5HT turnover to adult nicotine treatment and withdrawal (Figure 3B). Adult males who received vehicle in adolescence showed a small, but significant overall increase in 5HT turnover when compared to basal values (main treatment effect, p < 0.04), both during nicotine treatment and in withdrawal. These increases were greatly augmented in males who had received prior adolescent nicotine exposure (main treatment effect, p < 0.008 comparing adolescent nicotine + adult nicotine group to the adolescent vehicle + adult nicotine group). Furthermore, there was a significant change in time course of effect (age interaction, p < 0.01), characterized by a large increase in turnover during late stages of withdrawal (PN120, PN130) that subsided by PN180. In females receiving just the adult nicotine treatment, there was an increase in 5HT turnover triggered by withdrawal (adult nicotine × age interaction compared to basal values, p < 0.05; individually significant on PN110, p < 0.003). In females who received prior adolescent nicotine exposure the withdrawal-induced peak was blunted and displaced to later times (PN120, PN130).

Nicotine treatment had a small, but statistically significant effect on body weights (data not shown). By itself, adolescent nicotine evoked an average 3% reduction (p < 0.05 for the main treatment effect), without interactions of treatment with age or sex, and a similar result was obtained with adult nicotine alone (average 3% reduction, p < 0.05 for the main treatment effect, no interaction with age or sex). Animals receiving nicotine both in adolescence and adulthood showed an average 6% weight deficit (p < 0.0002 for the main treatment effect, no interaction with age or sex), representing additive effects of the two individual treatments (no interaction of adolescent nicotine × adult nicotine). There were no significant differences in cerebral cortex weight for any of the treatments (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our findings support the view that nicotine exposure in adolescence reprograms the response to subsequent exposure to nicotine in adulthood, and further, that this effect is strongly sex-selective. In our earlier work, we found that in males, adolescent nicotine administration augments the expression of 5HT receptors, an effect that emerges in young adulthood and then persists long-term (Slotkin and Seidler, 2009). Ordinarily, receptor upregulation is a compensatory response to reduced presynaptic input; however, in the present study, we found that neurotransmitter utilization, monitored by 5HT turnover, was largely unchanged over the same period in animals that had received just the adolescent treatment. Accordingly, the net effect (unchanged presynaptic activity but increased receptor levels) is augmented 5HT synaptic function, lasting months after discontinuing adolescent nicotine treatment. In females, adolescent nicotine produces the opposite effect on receptors, characterized by deficits that emerge in young adulthood (Slotkin and Seidler, 2009); again, we did not find this change to be associated with any significant change in 5HT turnover, so for females, the net effect is a persistent reduction in synaptic communication. In either situation, then, overall 5HT function does not return to normal after adolescent nicotine exposure, but rather, changes persist well beyond the immediate effects of nicotine administration and withdrawal. Thus, our results suggest that nicotine dependence permanently reprograms 5HT neural circuitry so that the restoration of normal behavioral function after discontinuing nicotine treatment does not actually connote a return to the pre-exposure state. This interpretation is consistent with the “sensitization-homeostasis” model of addiction, which predicts that long-term changes in synaptic function leave the brain susceptible to subsequent readdiction, thus accounting for the high likelihood of relapse (DiFranza and Wellman, 2005).

Reprogramming of 5HT synaptic function by adolescent nicotine treatment was even more evident when we challenged the animals with nicotine in adulthood. In males who had received prior nicotine treatment in adolescence, adult nicotine administration produced a much greater increase in 5HT turnover, an effect that was exacerbated even further after initiating withdrawal. In fact, the enhanced utilization was so large that it produced depletion of neurotransmitter stores, leading to significant reductions in the 5HT concentration. The evidence for reprogramming is reinforced by our prior results for 5HT receptors (Slotkin and Seidler, 2009); rather than showing the expected downregulation in response to presynaptic hyperactivity, males given adolescent nicotine display increases in receptor binding after adult nicotine administration, further augmenting the consequences of presynaptic overstimulation. The question remains, though as to what triggers this change in presynaptic-postsynaptic response coupling. There are two likely possibilities. First, there could be physical miswiring of 5HT synapses, i.e. 5HT neurons may not be properly juxtaposed to cells with the receptors. Indeed, adolescent nicotine produces permanent changes in dendritic morphology (McDonald et al., 2005). Alternatively, there could be deficits in post-receptor coupling (Slotkin et al., 2008b). Notwithstanding whether these mechanisms underlie the observed changes in the parameters of 5HT synaptic function, the expectation is that behavioral consequences linked to 5HT systems will be substantially worsened when nicotine administration in adulthood is preceded by prior exposure in adolescence.

Our results also indicate that, even in animals given nicotine only in adulthood, there are important sex differences in 5HT synaptic activity. Overall, males showed a persistent elevation of 5HT turnover that did not resolve even by PN180. This is especially interesting because 5HT receptor upregulation also emerges over this long time-span, instead of the compensatory downregulation that would be expected as an adaptation to increased neurotransmitter release (Slotkin et al., 2007b; Slotkin and Seidler, 2009). Presynaptic overstimulation, combined with receptor upregulation, indicates a sustained state of 5HT hyperresponsiveness, providing a biologic basis for the sensitization-homeostasis model and for sustained vulnerability to relapse (DiFranza and Wellman, 2005). A second sex difference seen in adults given nicotine was that females, but not males, showed a substantial rise in 5HT turnover in the first few days after discontinuing nicotine treatment. Given the known roles of 5HT in emotional state and anxiety, these differences may contribute to the fact that, in smokers, females show a greater depressive component during withdrawal, contributing to relapse (Nakajima and al’Absi, 2012; Pomerleau et al., 2005). In turn, this would indicate that smoking cessation strategies in females could benefit from pharmacologic interventions centering around 5HT and its role in depression and anxiety. Interestingly, prior nicotine exposure in adolescence blunted or delayed the withdrawal-induced spike in 5HT turnover seen in females; in turn, this suggests that emotional responses to nicotine withdrawal in adulthood are likely to differ in females who had prior nicotine exposure in adolescence.

Finally, although our work focused on cerebrocortical 5HT pathways, there is every reason to suspect that reprogramming of responses involves other brain regions and neurotransmitters involved in addiction, reward and emotional state. Adolescent nicotine treatment evokes late-emerging suppression of both striatal dopaminergic activity and noradrenergic responsiveness in the hippocampus and other regions (Trauth et al., 2001). Furthermore, there are persistent effects of adolescent nicotine, adult nicotine, or combined exposure, on cholinergic pathways in multiple brain regions, including those involved in learning and memory, reward and emotion (Abreu-Villaça et al., 2003; Slotkin et al., 2008a). Accordingly, it is highly likely that these additional targets compound the impact of adolescent and adult nicotine exposure on the cerebrocortical 5HT systems evaluated in the current study. Although it would be difficult to ascribe specific functional outcomes to each individual pathway, these results all point to major reprogramming of neural circuits by adolescent nicotine that converge on the many behaviors that contribute to the establishment, maintenance and persistence of addiction. It would be clearly useful to pursue whether smoking cessation therapies might benefit from antidepressants targeting different neurotransmitters (e.g. bupropion for dopaminergic systems, venlafaxine for noradrenergic systems), alone or in combination with more commonly-used, serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors.

In summary, the present work reinforces the concept that nicotine has unique effects in adolescence, leading to lasting, potentially permanent, changes in 5HT synaptic function that are likely to contribute to responses to other addictive drugs (Adriani et al., 2006; Bracken et al., 2011; Hutchison and Riley, 2008; Imad Damaj et al., 2009; Kelley and Middaugh, 1999; Klein, 2001; Marco et al., 2006; Rinker et al., 2011; Santos et al., 2009). Our results also provide a proof-of-principle that the period in which synaptic plasticity can reprogram drug responses extends well beyond fetal or neonatal stages, so that the entire framework of what constitutes “developmental neurotoxicity” needs to be expanded. Specifically, as shown here, prior exposure to nicotine in adolescence augments the effects of nicotine administration and withdrawal in adulthood, both for 5HT systems (as seen here) as well as for other neurotransmitter circuits (Slotkin et al., 2008a). These changes may contribute to life-long vulnerability to relapse and re-addiction.

Highlights.

Adolescent nicotine treatment sensitized 5HT systems to subsequent adult nicotine effects and withdrawal

The main effect was activation of 5HT presynaptic activity, monitored by 5HT turnover

Effects were much greater in males than females, and peaked during withdrawal

Reprogramming of responses by adolescent nicotine may contribute to relapse and re-addiction

Acknowledgments

Research was supported by NIH ES022831 and EPA 83543701. EPA support does not signify that the contents reflect the views of the Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Abbreviations used

- 5HIAA

5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid

- 5HT

5-hydroxytryptamine, serotonin

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- PN

postnatal day

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: TAS has received consultant income in the past three years from the following firms: The Calwell Practice (Charleston WV), Finnegan Henderson Farabow Garrett & Dunner (Washington DC), Carter Law (Peoria IL), Gutglass Erickson Bonville & Larson (Madison WI), The Killino Firm (Philadelphia PA), Alexander Hawes (San Jose, CA), Pardieck Law (Seymour, IN), Tummel & Casso (Edinburg, TX), Shanahan Law Group (Raleigh NC), and Chaperone Therapeutics (Research Triangle Park, NC).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abreu-Villaça Y, Seidler FJ, Qiao D, Tate CA, Cousins MM, Thillai I, Slotkin TA. Short-term adolescent nicotine exposure has immediate and persistent effects on cholinergic systems: critical periods, patterns of exposure, dose thresholds. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1935–1949. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriani W, Deroche-Gamonet V, Le Moal Ml, Laviola G, Piazza PV. Preexposure during or following adolescence differently affects nicotine-rewarding properties in adult rats. Psychopharmacology. 2006;184:382–390. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriani W, Granstrem O, Macri S, Izykenova G, Dambinova S, Laviola G. Behavioral and neurochemical vulnerability during adolescence in mice: studies with nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:869–878. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriani W, Spijker S, Deroche-Gamonet V, Laviola G, Le Moal M, Smit AB, Piazza PV. Evidence for enhanced neurobehavioral vulnerability to nicotine during periadolescence in rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4712–4716. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04712.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barone S, Das KP, Lassiter TL, White LD. Vulnerable processes of nervous system development: a review of markers and methods. Neurotoxicology. 2000;21:15–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracken AL, Chambers RA, Berg SA, Rodd ZA, McBride WJ. Nicotine exposure during adolescence enhances behavioral sensitivity to nicotine during adulthood in Wistar rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Millar WJ. Age of smoking inititation: implications for quitting. Health Rep. 1998;9:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby SM, Tiffany ST, Shiffman S, Niaura RS. Are adolescent smokers dependent on nicotine? A review of the evidence. Drug Alc Depend. 2000;59:S83–S95. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00166-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles CD. Saying goodbye to the crack baby. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1993;15:290–292. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(93)90024-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo V. Perinatal neurotoxicology of psychotropic drugs. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1987;8:346–350. [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Wellman RJ. A sensitization-homeostasis model of nicotine craving, withdrawal, and tolerance: integrating the clinical and basic science literature. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2005;7:9–26. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus CF. Neurotransmitters and neurotrophins collaborate to influence brain development. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1998;5:389–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraday MM, Elliott BM, Grunberg NE. Adult vs. adolescent rats differ in biobehavioral responses to chronic nicotine administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:475–489. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00642-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faraday MM, Elliott BM, Phillips JM, Grunberg NE. Adolescent and adult male rats differ in sensitivity to nicotine’s activity effects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;74:917–931. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman E, Capitman J. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking among teens. Pediatrics. 2000;106:748–755. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean P, Landrigan PJ. Developmental neurotoxicity of industrial chemicals. Lancet. 2006;368:2167–2178. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69665-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Croghan GA, Beede SD, Wolter TD, Croghan IT, Patten CA. Nicotine patch therapy in 101 adolescent smokers: efficacy, withdrawal symptom relief, and carbon monoxide and plasma cotinine levels. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison MA, Riley AL. Adolescent exposure to nicotine alters the aversive effects of cocaine in adult rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imad Damaj M, Kota D, Robinson SE. Enhanced nicotine reward in adulthood after exposure to nicotine during early adolescence in mice. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.06.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley BM, Middaugh LD. Periadolescent nicotine exposure reduces cocaine reward in adult mice. J Addict Dis. 1999;18:27–39. doi: 10.1300/J069v18n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein LC. Effects of adolescent nicotine exposure on opioid consumption and neuroendocrine responses in adult male and female rats. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;9:251–261. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauder JM. Prevention of Physical and Mental Congenital Defects. New York: Alan R. Liss; 1985. Roles for neurotransmitters in development: possible interaction with drugs during the fetal and neonatal periods; pp. 375–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED. Persisting effects of chronic adolescent nicotine administration on radial-arm maze learning and response to nicotinic challenges. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1999;21:338. [Google Scholar]

- Lorber J. Is your brain really necessary? Nurs Mirror. 1981;152:29–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco EM, Llorente R, Moreno E, Biscaia JM, Guaza C, Viveros MP. Adolescent exposure to nicotine modifies acute functional responses to cannabinoid agonists in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;172:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CG, Dailey VK, Bergstrom HC, Wheeler TL, Eppolito AK, Smith LN, Smith RF. Periadolescent nicotine administration produces enduring changes in dendritic morphology of medium spiny neurons from nucleus accumbens. Neurosci Lett. 2005;385:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, al’Absi M. Predictors of risk for smoking relapse in men and women: a prospective examination. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26:633–637. doi: 10.1037/a0027280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten CA, Choi WS, Gillin JC, Pierce JP. Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking predict development and persistence of sleep problems in US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2000;106:50–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS, Mehringer AM, Snedecor SM, Ninowski R, Sen A. Nicotine dependence, depression, and gender: characterizing phenotypes based on withdrawal discomfort, response to smoking, and ability to abstain. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2005;7:91–102. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priestley BL, Lorber J. Ventricular size and intelligence in achondroplasia. Z Kinderchir. 1981;34:320–326. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1063368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakic P, Bourgeois JP, Goldman-Rakic PS. Synaptic development of the cerebral cortex: implications for learning, memory, and mental illness. Prog Brain Res. 1994;102:227–243. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinker JA, Hutchison MA, Chen SA, Thorsell A, Heilig M, Riley AL. Exposure to nicotine during periadolescence or early adulthood alters aversive and physiological effects induced by ethanol. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salin-Pascual RJ, De la Fuente JR, Galicia-Polo L, Drucker-Colin R. Effects of transdermal nicotine on mood and sleep in nonsmoking major depressed patients. Psychopharmacology. 1995;121:476–479. doi: 10.1007/BF02246496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos GC, Marin MT, Cruz FC, Delucia R, Planeta CS. Amphetamine- and nicotine-induced cross-sensitization in adolescent rats persists until adulthood. Addict Biol. 2009;14:270–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slawecki CJ, Ehlers CL. Lasting effects of adolescent nicotine exposure on the electroencephalogram, event related potentials, and locomotor activity in the rat. Dev Brain Res. 2002;138:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00455-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slawecki CJ, Gilder A, Roth J, Ehlers CL. Increased anxiety-like behavior in adult rats exposed to nicotine as adolescents. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:355–361. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA. Fetal nicotine or cocaine exposure: which one is worse? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:931–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA. Nicotine and the adolescent brain: insights from an animal model. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2002;24:369–384. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(02)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA. Cholinergic systems in brain development and disruption by neurotoxicants: nicotine, environmental tobacco smoke, organophosphates. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;198:132–151. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA. If nicotine is a developmental neurotoxicant in animal studies, dare we recommend nicotine replacement therapy in pregnant women and adolescents? Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2008;30:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Bodwell BE, Ryde IT, Seidler FJ. Adolescent nicotine treatment changes the response of acetylcholine systems to subsequent nicotine administration in adulthood. Brain Res Bull. 2008a;76:152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, MacKillop EA, Rudder CL, Ryde IT, Tate CA, Seidler FJ. Permanent, sex-selective effects of prenatal or adolescent nicotine exposure, separately or sequentially, in rat brain regions: indices of cholinergic and serotonergic synaptic function, cell signaling, and neural cell number and size at six months of age. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007a;32:1082–1097. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Ryde IT, MacKillop EA, Bodwell BE, Seidler FJ. Adolescent nicotine administration changes the responses to nicotine given subsequently in adulthood: adenylyl cyclase cell signaling in brain regions during nicotine administration and withdrawal, and lasting effects. Brain Res Bull. 2008b;76:522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Ryde IT, Tate CA, Seidler FJ. Lasting effects of nicotine treatment and withdrawal on serotonergic systems and cell signaling in rat brain regions: separate or sequential exposure during fetal development and adulthood. Brain Res Bull. 2007b;73:259–272. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ. A unique role for striatal serotonergic systems in the withdrawal from adolescent nicotine administration. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Seidler FJ. Nicotine exposure in adolescence alters the response of serotonin systems to nicotine administered subsequently in adulthood. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31:58–70. doi: 10.1159/000207494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin TA, Tate CA, Cousins MM, Seidler FJ. Prenatal nicotine exposure alters the response to subsequent nicotine administration and withdrawal in adolescence: serotonin receptors and cell signaling. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2462–2475. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauth JA, Seidler FJ, Ali SF, Slotkin TA. Adolescent nicotine exposure produces immediate and long-term changes in CNS noradrenergic and dopaminergic function. Brain Res. 2001;892:269–280. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauth JA, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. An animal model of adolescent nicotine exposure: effects on gene expression and macromolecular constituents in rat brain regions. Brain Res. 2000a;867:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauth JA, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Persistent and delayed behavioral changes after nicotine treatment in adolescent rats. Brain Res. 2000b;880:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02823-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsoh JY, Humfleet GL, Munoz RF, Reus VI, Hartz DT, Hall SM. Development of major depression after treatment for smoking cessation. Am J Psychiat. 2000;157:368–374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A, Rosenberg M, Balaban-Gil K. Neurodevelopmental and neurobehavioral sequelae of selected substances of abuse and psychiatric medications in utero. Child Adolesc Psychiat Clin North Am. 1999;8:845–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker-Azmitia PM. Role of serotonin and other neurotransmitter receptors in brain development: basis for developmental pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1991;43:553–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu LT, Anthony JC. Tobacco smoking and depressed mood in late childhood and early adolescence. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1837–1840. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.12.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Seidler FJ, Ali SF, Slikker W, Slotkin TA. Fetal and adolescent nicotine administration: effects on CNS serotonergic systems. Brain Res. 2001;914:166–178. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02797-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Seidler FJ, Cousins MM, Slikker W, Slotkin TA. Adolescent nicotine administration alters serotonin receptors and cell signaling mediated through adenylyl cyclase. Brain Res. 2002;951:280–292. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]