Abstract

Objective

Across the United States, tens of thousands of college students are mandated to receive an alcohol intervention following an alcohol policy violation. Telephone interventions may be an efficient method to provide mandated students with an intervention, especially when they are away from campus during summer vacation. However, little is known about the utility of telephone-delivered brief motivational interventions.

Method

Participants in the study (N = 57) were college students mandated to attend an alcohol program following a campus-based alcohol citation. Participants were randomized to a brief motivational phone intervention (pBMI) (n = 36) or assessment only (n = 21). Ten participants (27.8%) randomized to the pBMI did not complete the intervention. Follow-up assessments were conducted 3, 6, and 9 months post-intervention.

Results

Results indicated the pBMI significantly reduced the number of alcohol-related problems compared to the assessment-only group. Participants who did not complete the pBMI appeared to be lighter drinkers at baseline and randomization, suggesting the presence of alternate influences on alcohol-related problems.

Conclusion

Phone BMIs may be an efficient and cost-effective method to reduce harms associated with alcohol use by heavy-drinking mandated students during the summer months.

1. Introduction

Tens of thousands of college students receive alcohol violations for violating campus policy for diverse offenses, include possession of alcohol, being in the presence of alcohol, behavioral problems while intoxicated, and alcohol-related medical complications (see Barnett et al., 2008). Students who are found to violate the campus’s alcohol policy are regularly mandated to complete either public service or an alcohol intervention (Wechsler et al., 2002). Brief Motivational Interventions (BMIs) are currently the standard individual intervention supported by empirical research (Cronce & Larimer, 2011). BMIs are commonly delivered in 1 to 2 individual meetings (one-on-one), are approximately 50 minutes long (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007), and use a motivational interviewing approach (e.g., Miller & Rollnick, 2012) to reduce heavy drinking.

Although BMIs delivered on campus can effectively reduce drinking (e.g., Carey, Henson, Carey, & Maisto, 2009) and alcohol-related problems (e.g., Borsari & Carey, 2005) in mandated college students, summer months pose a specific challenge to continuity of care as most students leave campus for three to five months. However, surprisingly little research has been conducted regarding drinking during the summer months and there is little information regarding how these mandated cases are handled at the end of the school year. Motivational interventions delivered via the telephone have been used to address substance use and other risky behaviors in a variety of populations (Walker, Roffman, Picciano, & Stephens, 2007). Furthermore, telephone interventions have been demonstrated to reduce drinking in adults as a “step down” treatment following intervention (e.g., McKay, Lynch, Shepard, & Pettinati, 2005) or as a component of stepped care (e.g., Bischof et al., 2008). Of course, web interventions that incorporate personalized feedback and harm reduction strategies have shown some promise with mandated college students (Doumas, Workman, Smith, & Navarro, 2011), and could also be of utility during the summer months. That said, interventions incorporating some degree of therapist contact (whether face-to-face or via telephone) have been linked to larger and more sustained reductions in drug and alcohol abuse than computerized or web-based treatments (Newman, Szkodny, Llera, & Przeworski, 2011). A recent meta-analysis demonstrated a similar pattern with college students; namely, that in-person BMIs were superior to web- or computer-delivered interventions in facilitating long-term reductions in alcohol use (Carey et al., 2012). Therefore, telephone interventions may represent an ideal blend of convenience and personal communication. To our knowledge, no study has implemented a telephone-administered BMI with college students reporting heavy drinking and alcohol-related consequences.

This study examined a subset of data from a larger trial implementing stepped care with mandated college students (Borsari et al., 2012). The occurrence of alcohol violations occurring late in the school year provided the opportunity to evaluate the efficacy of a phone BMI (pBMI) delivered during the summer months. All participants had received a brief advice session addressing their alcohol use before departing campus, yet continued to report risky drinking six weeks after this session. We hypothesized that individuals receiving the pBMI during the summer would reduce their drinking and alcohol-related problems significantly more than individuals receiving assessment only.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Design

The data used in this study was from a larger trial implementing stepped care with mandated college students at a four-year, private liberal arts university in the Northeast US (see Borsari et al., 2012 for description). There were two steps of intervention. First, following completion of the baseline assessment, all participants initially received a 15-minute Brief Advice (BA) session (Step 1). Six weeks following this session, participants completed an assessment via the internet. Participants who reported continued risky alcohol use (defined as 4 or more heavy drinking episodes and/or reporting 5 or more alcohol-related problems in the past month) during the 6-week assessment were randomized to (a) Step 2 intervention, a 60- minute or less pBMI or (b) an assessment only control condition (AO). Urn randomization (Stout, Wirtz, Carbonari, & Del Boca, 1994), using gender and race as blocking variables, was used to randomly assign participants to condition. Participants completed 3-, 6- and 9-month follow-ups via web assessment.

2.2 Participants

Participants (N = 57) were undergraduate students age 18 years and older who violated campus alcohol policy within six weeks of the end of the spring semester. As a result of the timing of their offense, they received a BA session but completed their 6 week assessment during the summer and therefore were not able to receive an in-person BMI in Step 2. This situation provided us with an opportunity to evaluate the efficacy of a phone BMI in this subgroup of participants. Participants provided informed consent and the university Institutional Review Board of Brown University and the study site approved all procedures.

2.2.1 Recruitment

Recruitment took place from April to May throughout the duration of the parent trial (2005–2009). Because the follow-up assessments were completed using web-based surveys, all potential participants were provided detailed information regarding procedures implemented to protect the security of their responses. Students who declined to participate in the project received treatment as usual from the OHW; this treatment consisted of a 15–30 minute individual discussion of their referral incident and alcohol use. Students were also informed they might be asked to receive a second intervention addressing alcohol use and problems over the summer months. Students were told they would receive $15 for the baseline assessment, $40 for the 6-week assessment, and $25, $35 and $60 for the 3-, 6- and 9-month assessments, respectively.

2.3 Measures

Participants provided demographic information regarding their gender, age, weight, year in school, and race/ethnicity. Alcohol use outcome variables were obtained using the Alcohol and Drug Use Measure (Borsari & Carey, 2005). Frequency of heavy episodic drinking (HED) was obtained using a gender-specific question that asked participants to report the number of times they consumed 5 or more drinks for males (4+ for females) in one sitting in the past month. This measure also recorded the number of drinks consumed during a typical and peak episode (i.e., the maximum number of drinks), as well as the amount of time spent drinking for each of those episodes to calculate the students’ estimated typical and peak blood alcohol concentration (pBAC). Alcohol-related consequences were assessed using the Brief-YAACQ (B-YAACQ; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005). The B-YAACQ was used as an outcome variable as this measure has been found to be reliable and sensitive to changes in alcohol use over time (Kahler, Hustad, Barnett, Strong, & Borsari, 2008). The B-YAACQ demonstrated high internal consistency in this sample (α = .89). Regarding recidivism, participants were asked how many times they had been mandated for another alcohol violation since the last assessment.

2.4 Interventions

2.4.1 Brief Advice

The manualized Brief Advice was administered by peer counselors (fellow undergraduate student). The counselor training focused on becoming familiar with the didactic information and basic MI strategies (e.g., asking open-ended questions, avoiding confrontation and labeling students). All Brief Advice sessions were audio recorded and reviewed by one of the first four authors. Peer counselors received on-going, individual feedback on their intervention delivery skills to ensure adherence. Peer counselors facilitated discussion of the events leading to the referral incident and any changes the student had made to his or her drinking as a result. The participant was then provided with a 12-page educational booklet that addressed definitions of risky drinking, common alcohol-related problems, and ways to reduce or stop drinking (adapted from Cunningham, Wild, Bondy, & Lin, 2001). The average time to complete the Brief Advice was 15.23 minutes (SD = 4.06).

2.4.2. Phone Brief Motivational Intervention (pBMI)

This pBMI contained the same content and feedback as the in-person BMI sessions that have significantly reduced alcohol use and problems with mandated and non-mandated students in other trials (Borsari & Carey, 2000, 2005; Borsari, O’Leary Tevyaw, Barnett, Kahler, & Monti, 2007; Carey, Carey, Henson, Maisto, & DeMartini, 2011; Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2006; Carey et al., 2009; Hustad et al., in press). The only difference between the BMI delivered in the parent trial and the pBMI was the mode of delivery. The pBMIs were delivered by three master’s-level and doctoral-level professional clinicians. For the pBMI, a password protected personalized feedback report was emailed to the participant the day of the scheduled pBMI session. The participants were required to have access to the feedback form during the call, as well as take the call in a private, quiet, and safe location (e.g., not while driving). During the call, the interventionists used motivational interviewing skills while reviewing topics of the feedback form, including normative quantity/frequency of drinking, BAC and tolerance, alcohol-related consequences, influence of setting on drinking, and alcohol expectancies. The pBMI lasted between 35–45 minutes. The pBMI sessions were not audio-recorded.

2.5 Follow-up Assessments

Participants received telephone and/or email reminders to complete web-based follow-up assessments. Of the 36 students randomized to receive a Step 2 intervention, 26 (72.2%) participants received a pBMI. Despite repeated efforts to schedule their pBMI, 10 participants did not complete the intervention nor received personalized feedback. We continued to invite these non-completers (henceforth NC) to complete follow-up assessments. The average number of days from randomization to pBMI completion was 29.8 days. Of the 57 participants, 46 (80.7%) participants completed the 3-month follow-up; 52 (91.2%) participants completed the 6-month assessment; and 48 (84.2%) participants completed their 9-month assessment.

2.6 Data Analysis Plan

T-tests were used to examine group differences among the pBMI and AO groups at the time of randomization (6 weeks following the Brief Advice session)1. For the intent-to-treat analyses, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE; Liang & Zeger, 1986) using PROC GENMOD in SAS (SAS Institute Inc., 1997) to compare the two groups (pBMI and AO) on number of days of HED, typical BAC, drinks per week, frequency of drinking in the past month, and number of alcohol-related consequences. As students continued to be drinking in a risky fashion at the 6-week assessment, we alsocovaried the 6-week value of the respective dependent variable and included a linear effect of time. All participants, including those with missing data, were included in these analyses. Treatment condition was dummy coded using AO as the reference group. In addition time was centered so that we could evaluate the main effect of treatment and the time X treatment interaction in one simultaneous model; the time X treatment interaction indicates whether treatment effects became more or less pronounced over time.

3. Results

3.1 Preliminary Analyses

Participants were 61% male, 96% Caucasian, 4% Bi-racial, and 98% freshman with a mean age of 19.07 (SD = 0.88). They were cited for possession or presence of alcohol (80%), behavioral infraction (5.4%), or alcohol-related medical complications (12.3 %). Fifty-seven students completed their 6-week assessment over the summer break and were eligible for a Step 2 intervention2. Of these 57 students, 36 were randomly assigned to receive a pBMI and the remaining 21 participants were assigned to assessment-only. As can be seen in Table 1, ANOVAs revealed only one significant difference between these three conditions (pBMI, AO, NC): Members of the AO group were significantly older than the members of the NC and pBMI groups. Visual examination of group means prompted us to conduct pair-wise t-tests between groups, which confirmed the lack of group differences (p’s > .10).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics at 6-week Assessment Prior to Randomization

| Variable | Phone BMI n=36 | Assessment Only n=21 | Test Statistic (t/χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD or %) | M (SD or %) | ||

| Age in Years | 18.83 (0.74) | 19.48 (0.98) | 2.61 |

| Gendera | |||

| Male | 22 (61.11) | 13 (61.90) | 0.00 |

| Female | 14 (38.89) | 8 (38.10) | |

| Racea | |||

| White | 35 (97.22) | 21 (100.00) | |

| Non-white | 1 (2.78) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Year in schoola | |||

| Freshmen | 26 (72.22) | 11 (52.38) | |

| Sophomore | 7 (19.44) | 7 (33.33) | |

| Upperclassmen | 2 (5.56) | 3 (14.29) | |

| GPA | 2.97 (0.59) | 2.93 (0.80) | 0.23 |

| Alcohol use variables | |||

| Age at first drink | 15.22 (2.06) | 15.50 (1.79) | 0.50 |

| Type of offensea | |||

| Alc. presence or possession | 30 (83.33) | 16 (76.19) | |

| Behavioral infraction | 4 (11.11) | 4 (19.05) | |

| Medical infraction | 2 (5.56) | 1 (4.76) | |

| Self-close friend differenceb,c | −2.84 (8.78) | −3.75 (8.41) | −0.37 |

| Peak drinksb | 10.47 (4.47) | 11.63 (4.54) | 0.89 |

| Average no. drinks: typical episodeb | 7.44 (3.37) | 8.05 (3.30) | 0.64 |

| Dependent Variables | |||

| Frequency of drinkingb | 9.88 (8.56) | 10.60 (6.68) | 0.32 |

| Drinks per weekb,c | 18.87 (11.17) | 21.45 (12.65) | 0.76 |

| Heavy episodic drinkingb | 6.31 (2.79) | 8.15 (5.26) | 1.44 |

| Peak BACb | 0.19 (0.09) | 0.22 (0.09) | 1.43 |

| B-YAACQ | 6.52 (5.02) | 8.35 (5.89) | 1.19 |

Note: Behavioral infraction = Drunk in public, fighting, and fake ID; Heavy episodic drinking is defined as 5 or more drinks per occasion for men (4 or more for women); BAC = Blood Alcohol Content; B-YAACQ= Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire

Empty cells or counts < 5 precluded use of χ2 tests

Past month

Self-close friend difference = Self drinks per week – Close friend drinks per week

p < .05

3.2 Intervention Integrity and Fidelity

3.2.1 Brief Advice

A random selection of 10 (18%) of the 57 Step 1 sessions were coded to determine whether peer counselors discussed the booklet information during the session. Results indicated 14 or more of the 16 topics had been addressed in 70% of the sessions.

3.2.2 Phone Brief Motivational Intervention

As noted above, the pBMI sessions were not audio recorded. However, the parent project did record and code 161 (83%) face-to-face BMI sessions using the Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (MISC 2.1; Miller, Moyers, Ernst, & Amrhein, 2008). The interventionists for the pBMI sessions also implemented the coded face-to--face BMI sessions during the school year. Fidelity assessments demonstrated that these BMIs were delivered with high levels of integrity (see Borsari et al., 2012).

3.3 Main Outcomes

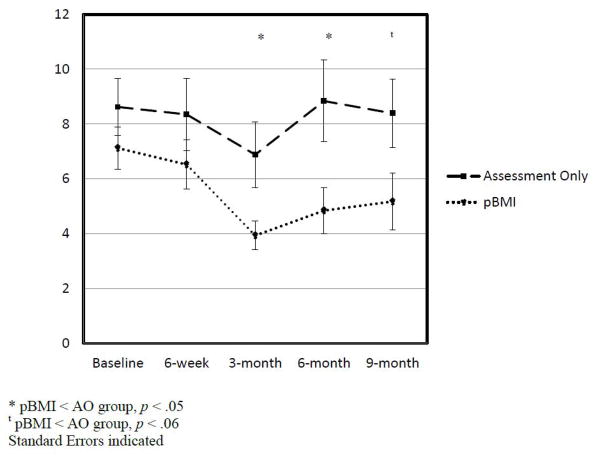

The results of the GLM models revealed no group differences in the four alcohol consumption variables. However, there were significant group differences on alcohol-related problems (IRR = 2.47, 95% CI =0.39–0.4.53, p < .02).3 Furthermore, the group X time interaction for this model was nonsignificant (p = .34), indicating that the effect of pBMI on alcohol-related problems persisted over time. Regarding the means and standard errors plotted for each time point in Figure 1, pairwise comparisons indicated that the pBMI group reported significantly fewer problems than the AO group at 3 and 6 month follow-ups (p’s < .05).

Figure 1.

Number of alcohol-related consequences over time for the two groups

3.4 Recidivism

In total, 11 participants (7 males and 4 females) reported receiving a second infraction during the 9 month follow-up period. Specifically, six infractions occurred between the 3 and 6 month assessments, 5 infractions occurred between the 6 and 9 month assessments, and no participants received two or more infractions. Seven of the 11 recidivists were in the AO group, indicative of a significant difference in recidivism rates over the 9 month follow-up period (likelihood ratio χ2(1) = 4.055, p = .04).

4. Discussion

This study provides preliminary support for implementing a pBMI to reduce alcohol-related problems with mandated students upon their return to campus, especially when face-to-face sessions are not feasible. Specifically, mandated students who continued to exhibit risky drinking behaviors following a brief advice session reported greater reductions in alcohol-related problems as well as lower recidivism rates following pBMI compared to an assessment-only control condition. Although it is likely that only a select subset of mandated students will require intervention over the summer months, this study indicates that a pBMI may be an effective option for campus providers who desire subsequent follow-up with higher-risk students

The maintenance of reductions in consequences in the months following a pBMI, even after returning to campus, is also of note. Of course, this was a small study with small numbers of participants in each group, precluding sweeping conclusions. That said, confidence in the outcomes is enhanced by their remarkable similarity to those of the parent trial (Borsari et al., 2012) in which in-person BMI recipients reported a reduction in problems but not alcohol use. Furthermore, previous (Borsari & Carey, 2005) and subsequent (Hustad et al., in press) trials implementing this BMI with mandated students have also demonstrated a similar pattern of reduction in consequences. This BMI contains an emphasis on consequences, providing those reported at baseline and the 6 week assessments and focusing on those that the students reported “bothered” them the most. Such a focus on personally-relevant consequences may have facilitated the adjustment of their drinking styles to minimize consequences. The mechanisms of the observed changes remain unclear: It is possible that a phone intervention may contain therapeutic interactions that facilitate change in ways that web or computer interventions cannot (e.g., Newman et al., 2011).

The results of the study should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, this was a small and exploratory study, and confidence in the findings would be enhanced by replication at other sites and in larger samples. Second, the sample was predominately White and was collected at a small liberal arts school in the northeast. Third, we were unable to evaluate the effect of assessment reactivity on outcomes – it is possible that completing these assessments may have influenced the participants’ drinking behaviors. Although there is little evidence that college students significantly misrepresent their drinking (see Borsari & Muellerleile, 2009), lack of collateral verification limits our ability to interpret the observed reductions in alcohol-related consequences. For example, the reductions in alcohol-related problems reported in those who did not complete a pBMI may have been a result of avoiding the efforts of the interventionists to schedule a session during the summer months. Fourth, the large number of participants randomized to the pBMI (n = 36) compared to AO (n = 21) may have been an artifact of the urn randomization being conducted for the larger trial, not just those whose 6 week assessment occurred during the summer. Fifth, although the high fidelity of the face-to-face BMI sessions from the parent trial provides indirect evidence that the pBMI interventions were delivered according to the study protocol, there is no way of knowing what actually occurred during the pBMI sessions.

The findings of the study suggest many promising directions for future research. First, although alcohol use and problems during the summer before matriculation has been well documented, additional research is needed on the alcohol use patterns of current students during the summer months. Often, researchers intentionally avoid having assessments occur during the summer months to avoid potential confounds (e.g., Turrisi et al., 2009). Second, further research on the efficacy of pBMI and other modalities of intervention seem warranted. Specifically, videoconferencing software (e.g., Skype™) and electronic interventions (e.g., e-interventions; Doumas, McKinley, & Book, 2009; Hustad, Barnett, Borsari, & Jackson, 2010) may provide alternate and cost-efficient intervention modalities to reach mandated students. It will be vital to compare pBMIs with e-interventions of all these modalities to ensure the provision of the most effective care for mandated students. If they prove to be effective, then exploration of their utility as booster sessions or at other times of the school year (e.g., Spring Break) would be warranted. Third, recent research has indicated that students prefer information regarding descriptive norms and practical costs associated with drinking, and do not like didactic information about drinking or protective behavioral strategies (Miller & Leffingwell, 2013). These findings could inform what feedback to provide during the pBMI in order to maximize intrinsic interest and minimize distraction and boredom.

In conclusion, this project demonstrated mandated students who continued to report heavy drinking episodes and alcohol-related consequences following a Brief Advice session reported a reduction in alcohol-related problems after receiving a pBMI delivered during the summer, reductions that were maintained after the participants returned to campus. Therefore, pBMI may be a feasible solution to reach students with a timely and effective intervention to reduce the harms associated with heavy alcohol use, especially when face-to-face intervention is not feasible.

Acknowledgments

Brian Borsari’s contribution to this manuscript was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grants R01-AA015518 and R01-AA017874. Nadine Mastroleo and John T.P. Hustad’s contribution to this manuscript was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant T32 AA07459. Peter Monti’s contribution was sponsored by a Senior Research and Mentoring K05AA19681. The authors also wish to thank Donna Darmody, Dr. John J. King, and Dr. Kathleen McMahon for their support of the project, as well as recognize all of the interventionists’ efforts. A limited portion of the manuscript was presented at the 44th annual convention of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.

Footnotes

The presence of three groups in the dataset (pBMI, AO, and NC) presented three options for analysis in addition to traditional intent-to-treat approach that required merging the NC and the pBMI group. First, we could have dropped the NC group from the analyses and focused solely on the pBMI and AO. However, we felt this was too conservative and limited the scope of the manuscript. Second, we could have added the NC individuals into the AO group, as they did not receive the pBMI nor any other intervention. We felt this was not an ideal decision because these participants were not treated the same as the AO participants, as they knew they were eligible for a pBMI addressing their alcohol use but chose not to receive the intervention. Third, we could have examined a separate NC group, permitting us to examine influence of actually receiving the pBMI during the summer months on subsequent alcohol use and problems. We found this approach compelling, so we conducted an exploratory series of GLM models of the pBMI, AO, and NC groups. These supplemental analyses indicated no group differences on the drinking variables but significant differences on alcohol-related problems, with the pBMI and NC group showing lower problems (F (2, 33) = 3.58; p = .039; eta-squared of .174).

89 students were recruited in April-May over the 4 years of the study. Of these, 32 (35%) were deemed “responders” to the BA session and did not require further intervention. This percentage is a significantly higher than the percentage of responders in the parent trial (112 responders out of 530; 21%); χ2 = 5.38, p = 0.020)

Identical intent-to-treat GLM models had a similar pattern of results: no group differences on drinking variables, significant groups differences on alcohol-related problems (F (1,35) = 10.634, p = .002, η2 = .233).

The contents of this manuscript do not represent the views of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barnett NP, Borsari B, Hustad JTP, Tevyaw TOL, Colby SM, Kahler CW, Monti PM. Profiles of college students mandated to alcohol interventions. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:684–694. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G, Grothues JM, Reinhardt S, Meyer C, John U, Rumpf HJ. Evaluation of a telephone-based stepped care intervention for alcohol-related disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;93(3):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a brief motivational intervention with college student drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(4):728–733. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.68.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Two brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(3):296–302. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Hustad JTP, Mastroleo NR, Tevyaw TO, Barnett NP, Kahler CW, Monti PM. Addressing alcohol use and problems in mandated college students: A randomized clinical trial using stepped care. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(6):1062–1074. doi: 10.1037/A0029902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Muellerleile P. Collateral reports in the college setting: A meta-analytic integration. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2009;33(5):826–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, O’Leary Tevyaw T, Barnett NP, Kahler CW, Monti PM. Stepped care for mandated college students: a pilot study. American Journal on Addictions. 2007;16(2):131–137. doi: 10.1080/10550490601184498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Henson JM, Maisto SA, DeMartini KS. Brief alcohol interventions for mandated college students: comparison of face-to-face counseling and computer-delivered interventions. Addiction. 2011;106(3):528–537. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):943–954. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Henson JM, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Computer Versus In-Person Intervention for Students Violating Campus Alcohol Policy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(1):74–87. doi: 10.1037/a0014281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college drinking. Alcohol, Research & Health. 2011;34:210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Wild TC, Bondy SJ, Lin E. Impact of normative feedback on problem drinkers: A small-area population study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(2):228–233. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, McKinley LL, Book P. Evaluation of two Web-based alcohol interventions for mandated college students. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(1):65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Workman C, Smith D, Navarro A. Reducing high-risk drinking in mandated college students: evaluation of two personalized normative feedback interventions. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2011;40(4):376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Web-based alcohol prevention for incoming college students: a randomized controlled trial. Addict Behav. 2010;35(3):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.012. S0306-4603(09)00277-9 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Mastroleo NR, Kong L, Urwin R, Zeman R, LaSalle L, Borsari B. The comparative effectiveness of individual and group motivational intervention for mandated college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0034899. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Strong DR, Borsari B. Validation of the 30-Day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(4):611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: the brief young adult alcohol consequences questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2005;29(7):1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Pettinati HM. The Effectiveness of Telephone-Based Continuing Care for Alcohol and Cocaine Dependence: 24-Month Outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(2):199–207. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Leffingwell TR. What do college student drinkers want to know? Student perceptions of alcohol-related feedback. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(1):214–222. doi: 10.1037/a0031380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Moyers TB, Ernst D, Amrhein P. Manual for the motivational interviewing skills code (MISC) Version 2.1. 2008 Unpublished Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing, Third Edition: Helping People Change. Guilford Publication; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Newman MG, Szkodny LE, Llera SJ, Przeworski A. A review of technology-assisted self-help and minimal contact therapies for anxiety and depression: Is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy? Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(1):89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome reserach. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;(Suppl 12):70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Larimer ME, Mallett KA, Kilmer JR, Ray AE, Mastroleo NR, Montoya H. A randomized clinical trial evaluating a combined alcohol intervention for high-risk college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(4):555–567. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Roffman RA, Picciano JF, Stephens RS. The check-up: in-person, computerized, and telephone adaptations of motivational enhancement treatment to elicit voluntary participation by the contemplator. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2007;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-2. 1747-597X-2-2 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993–2001. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]