Abstract

Acquisition and maintenance of avoidance behaviour is a key feature of all human anxiety disorders. Animal models have been useful in understanding how anxiety vulnerability could translate into avoidance learning. For example, behaviourally-inhibited temperament and female sex, two vulnerability factors for clinical anxiety, are associated with faster acquisition of avoidance responses in rodents. However, to date, the translation of such empirical data to human populations has been limited since many features of animal avoidance paradigms are not typically captured in human research. Here, using a computer-based task that captures many features of rodent escape-avoidance learning paradigms, we investigated whether avoidance learning would be faster in humans with inhibited temperament and/or female sex and, if so, whether this facilitation would take the same form. Results showed that, as in rats, both vulnerability factors were associated with facilitated acquisition of avoidance behaviour in humans. Specifically, inhibited temperament was specifically associated with higher rate of avoidance responding, while female sex was associated with longer avoidance duration. These findings strengthen the direct link between animal avoidance work and human anxiety vulnerability, further motivating the study of animal models while also providing a simple testbed for a direct human testing.

Keywords: Anxiety Disorders, Associative Learning, Avoidance Learning, Female Sex, Inbred Wistar-Kyoto Rats, Translational Research

1. Introduction

1.1. Behavioural Avoidance

Behavioural avoidance is often an adaptive strategy in daily life, which can prevent or reduce the impact of potentially aversive events and actions (e.g., stopping at a red light to avoid an accident). However, in some cases, emphasis on avoiding sources of possible harm can contribute to the development of a psychopathology. Indeed, avoidance behaviour is a predominant symptom in all anxiety disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), and it often distinguishes between those who develop a disorder following an exposure to stressors and those who recover (O'Donnell et al. 2007; Karamustafalioglu et al. 2006; Marshall et al. 2006; North et al. 1999; Barlow 2002). In spite of such a crucial role of avoidance behaviour in human anxiety disorders, most of the relevant literature on how avoidance behaviour develops and is maintained is based on research with non-human animals (Dymond and Roche 2009).

1.2. Escape-avoidance in non-human animals

In rats, avoidance paradigms often involve a warning signal (e.g., a light or tone) that precedes the occurrence of an aversive event (e.g., electric shock). The rats first learn to terminate the aversive event by making an adequate protective response (escape response; ER). Gradually, they learn the association between the warning signal and the aversive event, and come to exhibit the protective response during the warning signal but before onset of the aversive event, which results in omission of that aversive event (avoidance response; AR).

The acquisition and extinction of ARs show considerable individual differences. For instance, inbred Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats are highly stress-reactive and exhibit withdrawal responses in social and non-social situations, such as low activity in the open field and the forced-swim test (Pare 1994). Due to such reserved response in the face of novel situations, WKY rats are often used as an animal model for behaviourally-inhibited temperament (Servatius et al. 2008). Interestingly, in spite of the lack of mobility commonly associated with this strain, WKY rats acquire lever-press ARs at an accelerated rate and to a higher asymptotic level than outbred Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (Servatius et al. 2008). In addition to strain differences, there are also sex differences; specifically, female rats often show facilitated acquisition of the ARs relative to males of the same strain (Beck et al. 2010; Beatty and Beatty 1970; Van Oyen, Walg, and Van De Poll 1981). Since both female sex and inhibited temperament are vulnerability factors for anxiety disorders in humans (Gladstone et al. 2005; Clauss and Blackford 2012; Essex et al. 2010; Wittchen and Hoyer 2001; Zhang and Ho 2011; Chronis-Tuscano et al. 2009; Gudino 2013; Pigott 1999; Rosenbaum et al. 1993), these findings suggest a possible mechanism – facilitated acquisition of avoidance behaviour – that mediates vulnerability to anxiety disorders in humans.

1.3. Avoidance in humans

To date, the translation of animal models of avoidance to human clinical research has been limited by a lack of tools for measuring human avoidance behaviour in a laboratory setting. So far, human avoidance behaviour has been assessed mainly by subjective self-report questionnaires (e.g., Taylor and Sullman 2009; Sheynin et al. 2013; Cloninger 1986), which directly query the respondent about the type and frequency of avoidant behaviours, and then assign a point score based on these answers. Such approaches are subject to all the limitations of self-report, including the opportunity for people to falsify or withhold information, and the possibility that people may not be able to accurately or objectively assess their own behaviour. Questionnaires that probe past behaviour patterns also, of course, are unable to directly assess how these behaviours are acquired.

In attempts to more directly evoke and evaluate avoidance learning, several human studies have used mild (“unpleasant but bearable”) electric shocks (e.g., Delgado et al. 2009; Lovibond et al. 2008), or aversive visual or auditory stimuli (e.g., Dymond et al. 2011) as the aversive events that could be avoided. For instance, Lovibond et al. (2008) have considered paradigms in which human subjects make responses to avoid electric shock; their data provide support of an expectancy-based model of avoidance and anxiety, in which ARs are executed to attenuate the expectancy that one develops for an upcoming aversive event. Lovibond’s procedure consists of a 5-s visual warning signal followed by a 10-s delay interval and a period of a possible shock that could be avoided by pressing a specific key (the AR). Self-reported shock expectancy and skin conductance were recorded during the delay interval and were shown to decrease as the AR was acquired, suggesting a mechanism for anxiety reduction by avoidance performance. Furthermore, Lovibond et al. (2009) used a similar procedure to demonstrate how execution of ARs can prevent individuals from extinguishing fear conditioning, as well as to suggest a common cognitive mechanism in classical and instrumental aversive conditioning (Lovibond et al. 2013).

Although such methodologies add to our understanding of avoidance behaviour, it has also been argued that, due to ethical considerations, the aversive stimuli such as electric shock used in most human avoidance paradigms are too mild to effectively produce a conditioned response (Arcediano, Ortega, and Matute 1996). In addition, in many cases, human participants are explicitly informed about the AR at the beginning of the experimental session, meaning that the experiment investigates participants’ ability to perform ERs and ARs, rather than how participants learn to acquire these responses (e.g., Molet, Leconte, and Rosas 2006; Lovibond et al. 2008).

1.4. Computer-based tasks and the current study: Bridging the gap

Another line of human studies has considered computer-based tasks, some of which take the form of a spaceship videogame. For example, in one such design (Molet, Leconte, and Rosas 2006), participants control a spaceship and attempt to gain points by destroying an enemy that appears on the screen. During the task, warning signals appear and predict an on-screen aversive event (e.g. point loss and destruction of the player’s avatar). Participants can avoid this aversive event by moving the spaceship to designated “safe areas” on the screen during the warning period. The idea here is that, even though no physiologically aversive stimulus (e.g. electric shock) is delivered, people are nonetheless generally motivated to avoid aversive events within the game. Variations of such tasks have been successfully used to test passive avoidance (Arcediano, Ortega, and Matute 1996), active avoidance (Molet, Leconte, and Rosas 2006), differential effects of reinforcement contingencies and contextual variables (Raia et al. 2000), and discriminative learning and context-dependent latent inhibition (Byron Nelson and del Carmen Sanjuan 2006). However, none of those studies analyzed escape behaviour or the transition from ER to AR, nor have they tried to replicate the rat studies which show accelerated avoidance acquisition as a function of inhibited temperament or female sex.

Accordingly, in the current study, we have used a videogame task, based on that of Molet et al. (2006), to study avoidance acquisition, including the transition from ER to AR, in healthy humans with and without the vulnerability factors of inhibited temperament and female sex. We hypothesized that, as observed in rats, inhibited participants would demonstrate faster learning to escape from and/or avoid the aversive events in the current task. Consistent with the animal results, we further hypothesized that females might show similar effects. We were also interested in whether each vulnerability factor could independently promote acquisition and expression of avoidance, or whether the two factors might differentially contribute to specific aspects of avoidance behaviour.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 102 healthy young adults (Rutgers University-Newark undergraduate students; mean age 21.0 years, SD 4.3; 62.7% female). Seventy-one participants (69.6%) were recruited via a departmental subject pool, in which available research studies are posted and students sign up to participate in exchange for research credits in a psychology class. The remaining thirty-one participants (30.4%) were recruited via flyers posted around the campus and received cash payments in the amount of $20. No significant differences were observed between participants that received cash vs. those that received credits, on any behavioural, demographic, or questionnaire measure (all p>0.050); analyses were therefore pooled over all 102 participants. Participants were tested individually; the participant and experimenter sat in a quiet testing area during the experiment. All participants provided written informed consent and the experiment was approved by the local research ethics committee and conducted in accordance with guidelines established by the Declaration of Helsinki for the protection of human subjects.

2.2. Questionnaire

All participants completed the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ), a self-report questionnaire, which consists of 100 true/false items asking how the individual feels or behaves in various daily situations, and provides scores relating to three orthogonal personality dimensions (Cloninger, Przybeck, and Svrakic 1991). One personality dimension assessed by the TPQ, which the authors termed harm avoidance (HA), is defined as personality related to behavioural inhibition in response to novel or aversive situations (Cloninger 1986, 1987). In agreement with work reported by other groups (e.g., Mardaga and Hansenne 2007; Baeken et al. 2009; Wilson et al. 2011; Bailer et al. 2013), we used this subscale to assess inhibited temperament in the current study. We accordingly predicted that HA scores would be related to avoidance learning in the current task. The other two dimensions assessed by the TPQ are reward dependence (RD), defined as marked response to rewarding stimuli, and novelty seeking (NS), defined as exploratory activity in response to novel stimulation; we predicted little or no relationship between either RD or NS and avoidance learning in the current task.

2.3. Escape-Avoidance task

All participants were also administered a computer-based task which took the form of a spaceship videogame, which was an elaboration of a previously published task (Molet, Leconte, and Rosas 2006). The task was conducted on a Macintosh computer programmed in the SuperCard language (Solutions Etcetera, Pollock Pines, CA). The keyboard was masked except for three keys, labeled “←”, “→” and “FIRE”, which the participants used to perform the task. In the task (Figure 1), participants controlled a spaceship and could move it to one of five horizontal locations at the bottom of the screen, by using the left and right arrow keys. There was one enemy spaceship that randomly moved to one of six locations on the screen, approximately every 1-s (Figure 1A). Participants were instructed to gain points by using the “FIRE” key to shoot at and destroy this spaceship; every successful hit caused an explosion of the enemy spaceship and provided a reward of one point. This enemy spaceship did not fire back at the participant’s spaceship.

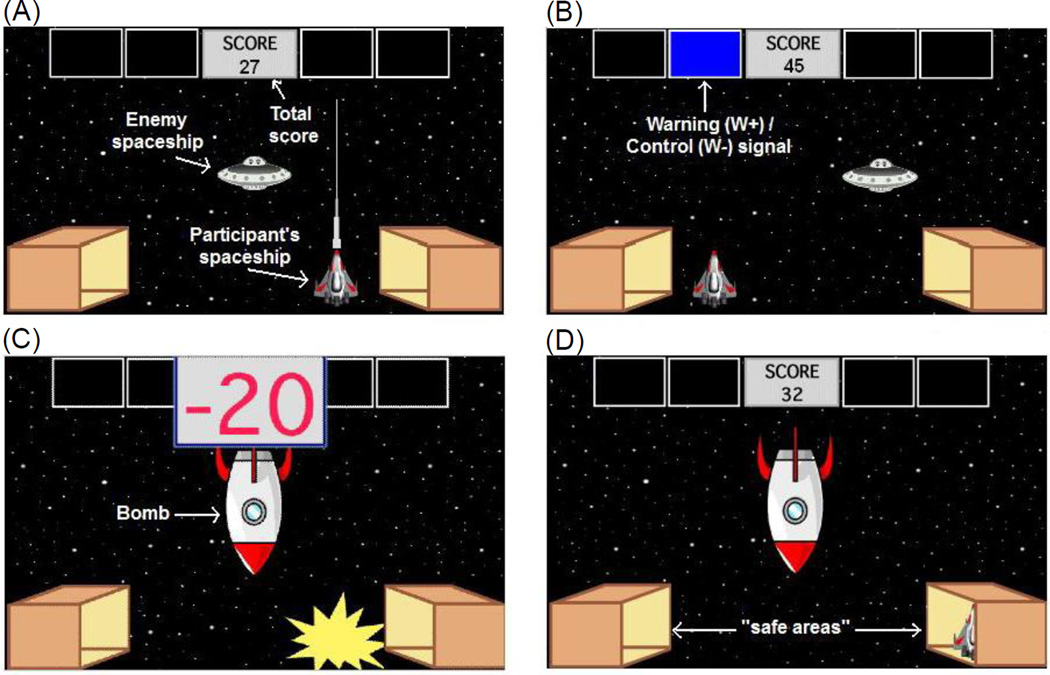

Figure 1.

Computer-based escape-avoidance task. (A) An enemy spaceship appears in one of six locations on the screen, approximately every 1-s. The participant’s goal is to gain points by shooting and destroying this spaceship (1 point for each hit). (B) The warning and control signals (W+ and W−, respectively) are colored rectangles (pink and blue) in the top part of the screen, which appear in pseudorandom order, every 20-s, and remain visible for 5-s (the warning and control periods). (C) W+ is always followed by appearance of a bomb, which remains onscreen for 5-s (bomb period). The bomb period is divided into six segments of equal duration; during each segment there is an explosion and loss of 5 points to a maximum of 30 points. (D) Moving to a “safe area” during the bomb period stops point loss (ER), while moving to a safe area during the warning period and remaining there through the rest of the warning period and through the subsequent bomb period prevents any point loss (AR). Labels shown in white text are for illustration only and do not appear on the screen during the task.

In addition, every 20-s, one of two colored rectangles (pink or blue) appeared for 5-s in one of four designated areas at the top of the screen (Figure 1B). For each participant, one of the rectangles represented a “warning signal” (W+) and the other one represented a “control signal” (W−); assignments of color to W+ and W− were counterbalanced across participants. Presence of W+ signaled the warning period, which was always followed by appearance of a bomb. The bomb remained onscreen for 5-s (bomb period). The bomb period was divided into six segments of equal duration; during each segment there was an explosion and a loss of 5 points (Figure 1C), to a maximum of 30 points. Presence of W− (control period) was not associated with any specific event; the control period used for measuring non-associative stimulus-evoked responding.

At the bottom corners of the screen, there were two box-shaped areas representing “safe areas” (Figure 1D). Moving the participant’s spaceship to one of those boxes was defined as “hiding”. While hiding, the participant’s spaceship could not be destroyed and no points could be lost, but neither could the participant shoot the enemy spaceship and gain points. Hiding during the bomb period was defined as an ER and stopped the aversive outcome (explosion and point loss) for any segment that the participant stayed inside the box. Hiding during the warning period was defined as an AR and completely prevented the aversive outcome (i.e., no explosion and no point loss), if the participant remained inside the box through the rest of the warning period and through the bomb period. However, if the participant moved his/her spaceship outside the box during the bomb period, the trial was not scored as an AR, and explosions and point loss would resume until either the participant executed an ER or the bomb period was completed. Importantly, the participant was given no explicit instructions about the safe areas or the hiding response.

At the beginning of the experiment, the participants saw the following brief instructions: “You are about to play a game in which you will be piloting a spaceship. You may use LEFT and RIGHT keys to move your spaceship, and press the FIRE key to fire lasers. Your goal is to score as many points as you can. The number of points will appear on the top of the screen. Good Luck!” Participants were then given one minute of practice time, during which they could shoot the enemy spaceship but no signals or bombs appeared. Twenty-four trials followed, each defined by the appearance of a signal (W+ or W−); the start of a trial was not explicitly signaled to the participant. On warning trials (W+ trials), W+ appeared for a 5-s warning period, followed by the 5-s bomb period, and then a 10-s intertrial interval, during which participants could gain points without any risk of aversive events. On control trials (W− trials), W− appeared for 5-s control period followed by a 15-s intertrial interval. Each experimental session included 12 W+ trials and 12 W− trials; trial order was counterbalanced among participants. Four different pseudorandom but fixed trial orders were used, with the constraint that the same type of signal (W+/W−) could not appear more than three times in a row. Participants were randomly and evenly assigned to trial orders, creating four order groups. A running tally at the top of the screen showed the current points accumulated; this tally was not allowed to fall below zero, to minimize frustration among participants. Importantly, even when tally was equal to zero and no further points could be lost, if the participant failed to hide during the bomb period, point loss and explosion of the participant’s spaceship were still displayed on the screen, so that the participant could observe the aversive outcome associated with failure to hide.

2.4. Data analysis

Approximately every 100-ms, the program checked if the participant’s spaceship was inside or outside one of the boxes. Following Molet et al. (2006), each 5-s of warning period, control period, and bomb period was divided into three equal segments for analysis. For each segment, the computer recorded whether the participant exhibited hiding which was defined as spending the entire segment duration in one of the boxes. Several dependent variables were recorded to describe various aspects of hiding behaviour. First, hiding duration, defined as number of segments with full hiding, was calculated for the warning or control period and for the bomb period, on each trial. Since hiding during the bomb period stopped the aversive event, this variable was used to assess ER.

Second, AR was assessed in terms of AR rate (number of W+ trials on which an AR was shown) and AR duration (number of warning period segments during which the participant exhibited hiding, averaged across trials). Importantly, to consider only hiding that was part of an AR response, only W+ trials where an AR was shown were included in the analyses of AR duration. While all ARs by definition result in avoidance of any point loss on that trial, longer AR duration indicates that a participant made a response earlier after onset of W+, and remained in hiding longer overall on that trial.

To test the acquisition of the hiding behaviour in the current task, we assessed hiding duration across the different trials. For this purpose, we used a mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with within-subject factors of trial (12 trials per period), as well as period (warning period, control period, bomb period) and between-subject factor of trial order (four different pseudorandom orders). Then, we used a consistent approach to analyze personality and sex differences on the described dependent variables. Stepwise linear regressions were used with predictors of the continuous scores on the different TPQ subscales (NS, HA, RD), sex and trial order. Dependent variables were average hiding duration during warning, control, and bomb periods, AR rate and AR duration. Since sample size was large (N=102), normality of groups was not expected to affect analyses. Sphericity was checked by Mauchly’s test and Greenhouse-Geisser correction was used when sphericity was violated. Post-hoc tests were executed when appropriate. Internal consistency of the different questionnaires was analyzed using Cronbach’s α with reverse scoring for individual questions taken into account. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Alpha was set to 0.05, with Bonferroni correction used as appropriate to protect against inflated risk of family-wise type-I error. Effects and interactions that did not approach significance (p>0.100) are not reported.

3. Results

3.1. Questionnaire and general performance

On the subscales of the TPQ questionnaire, mean (SD) values were 16.2 (4.8), 12.1 (6.7) and 19.8 (4.0) on NS, HA and RD, respectively. For the 34, 34 and 30 questions comprising NS, HA and RD, inter-item reliability was high (Cronbach’s α=0.709, 0.867 and 0.651, respectively). No correlations were found between TPQ subscales (Pearson correlations, all p>0.100).

All participants completed the computer-based task. Seven (6.8%) participants did not make any ERs, i.e., did not hide during any segment of the bomb period, on any W+ trial. Accordingly, these participants were never reinforced for a hiding response and thus, did not have the opportunity to learn the contingency in the task. Thus, following procedure in similar animal studies where data from “non-responders” are excluded (e.g., Beck et al. 2010), data from these participants were excluded from all behavioural analyses in the current study. There were no significant differences in demographic or questionnaire measures between those participants and the rest of the group (all p>0.050).

3.2. Hiding duration

To test acquisition of hiding behaviour in the current task, we analyzed participants’ hiding duration during warning, control and bomb periods, across the different trials (Figure 2A). Mixed ANOVA revealed main effects of trial [F(4.8,168.2)=50.738, p<0.001], period [F(1.8,168.2)=589.662, pπ.001] and trial order [F(3,91)=4.425, p=0.006]. Significant interactions were also found: period × trial [F(11.8,1073.8)=46.522, p<0.001] and period × trial × trial order [F(35.4, 1073.8)=1.616, p=0.013], while the interactions of trial × order and period × order approached significance (both 0.05<p<0.1). To investigate the two-way interaction (period × trial), hiding was compared between the three periods on each of the trials. Analyses revealed that starting from the fourth trial, all the three periods had different hiding duration (Tukey HSD post-hoc tests, all p<0.001), with longest hiding duration during the bomb period and shortest hiding duration during the control period (Figure 2A). To investigate the three-way interaction (period × trial × trial order), hiding on each type of period was compared between the four order groups, on each trial. None of these analyses reached adjusted significance (Tukey HSD post-hoc tests, all p>0.001).

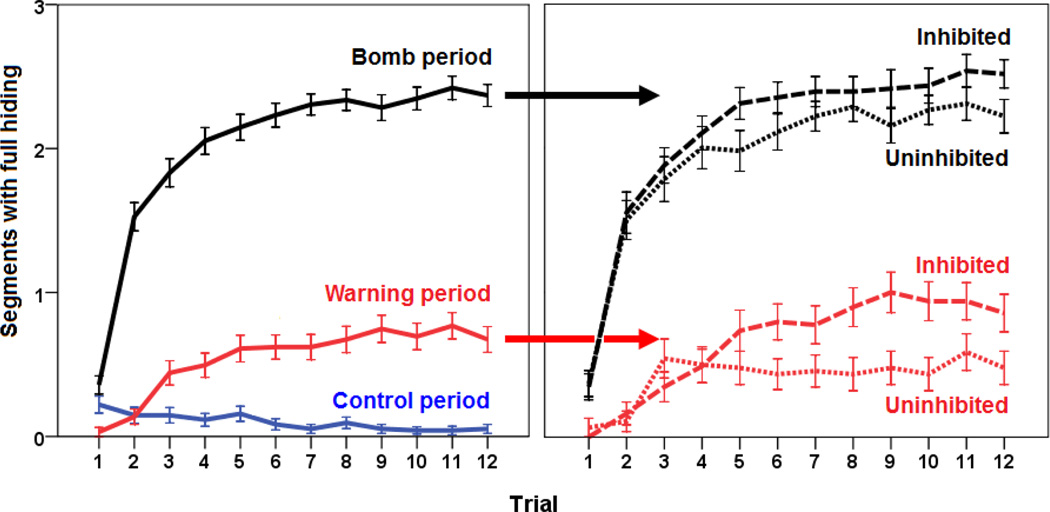

Figure 2.

Hiding duration, defined as number of segments during which the participant exhibited full hiding on each trial. (A) Hiding duration during the warning period, control period, and bomb period. Analyses revealed a main effect of trial, as well as differences between all the three periods starting from the fourth trial (all p<0.001) (B) Hiding duration during warning period and bomb period in inhibited (dashed curve; n=49) vs. uninhibited (dotted curve; n=46) participants, based on median split value on HA (median=12). Hiding during the control period was minimal in both groups and was omitted from this graph for clarity. Hiding duration during the warning period could be predicted by inhibited temperament (stepwise linear regression, p=0.024). Error bars indicate SEM.

Interestingly, there was a qualitative behaviour difference in the warning period between inhibited individuals and their uninhibited counterparts (based on median split value of HA (median=12); Figure 2B). To formally confirm this observation, several stepwise linear regressions were performed on average hiding duration during warning period, control period, and bomb period, with TPQ subscales scores, sex and trial order as predictor variables. Analyses revealed that hiding during the warning period could be predicted by a model including inhibited temperament (assessed by HA subscale) as a predictor variable [R2=0.054, R=0.232, F(1,93)=5.299, p=0.024]; none of the other predictor variables accounted for significant additional variance beyond that accounted for by inhibited temperament (all p>0.050). Analysis of hiding during the control period and bomb period identified no variables as significant predictors (all p>0.050).

3.3. AR rate and AR duration

Next, we analyzed AR rate, i.e., the number of trials where an AR was shown. Overall, 63 participants (66.3%) showed at least one AR throughout the experiment. As in the previous analyses, we used a stepwise linear regression to test whether sex or personality factors could reliably predict AR rate. Again, only inhibited temperament emerged as a significant predictor of AR rate [R2=0.044, R=0.211, F(1,93)=4.331, p=0.040].

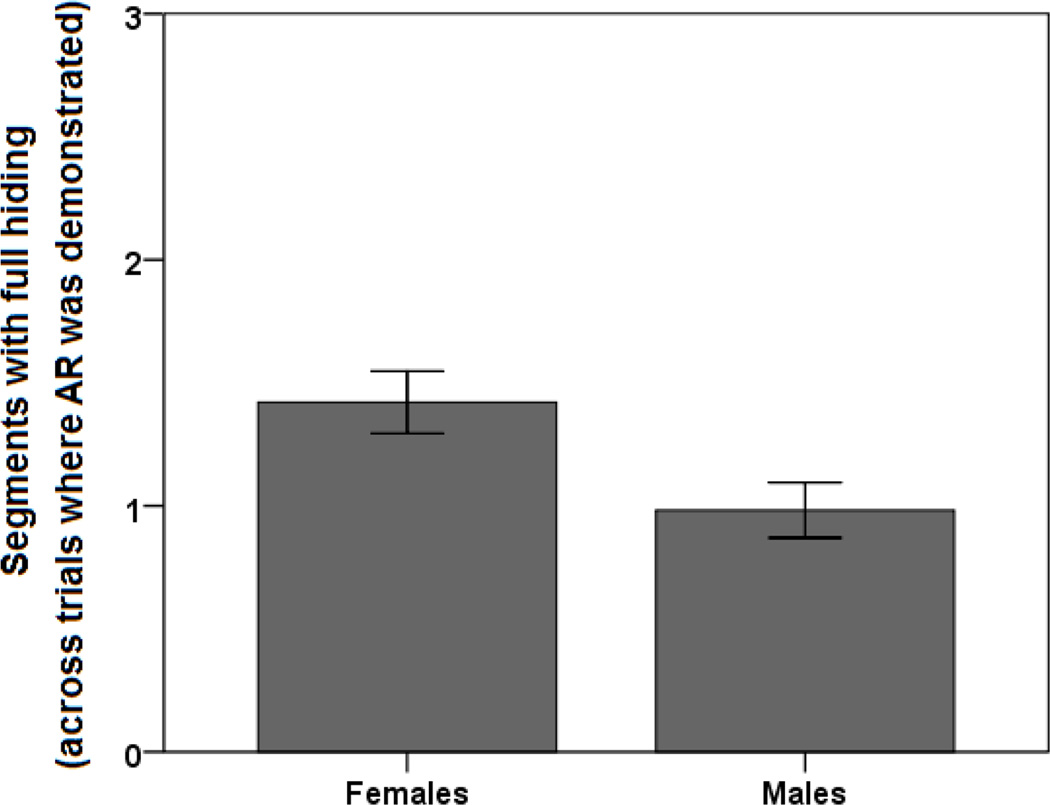

Lastly, we used a similar approach to analyze AR duration, calculated as the number of segments with full hiding during the warning period, averaged across all trials where an AR was demonstrated (i.e., W+ trials where the participant successfully avoided any point loss). Sex was the only significant predictor variable that was included [R2=0.092, R=0.304, F(1,61)=6.208, p=0.015], with females showing longer AR duration than males (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

AR duration, defined as the number of warning period segments during which the participant exhibited full hiding, across trials where an AR was demonstrated (i.e., no points were lost), in females (left; n=36) vs. males (right; n=27). AR duration could be predicted by sex (stepwise linear regression, p=0.015). Error bars indicate SEM.

4. Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to bridge the gap between human and animal avoidance literature, by testing human participants on a computer-based escape-avoidance task meant to capture several key features of the lever-press avoidance paradigm used in rats. As generally observed in animal research, and in spite of the lack of explicit instructions to use the safe areas, the vast majority of participants were able to learn an ER that terminated an aversive event, in this case accumulating point loss. However, only two-thirds of those participants also learned to produce ARs, allowing them to completely avoid that aversive event. Results showed associations between avoidance acquisition and two factors known to confer vulnerability to anxiety, namely inhibited temperament and female sex. While these factors have been shown to facilitate avoidance learning in animals, this is the first time to our knowledge that such associations have been examined in an escape-avoidance paradigm in humans. Importantly, each vulnerability factor was associated with a qualitatively different aspect of avoidance: inhibited temperament with greater propensity to execute ARs and female sex with longer-duration ARs.

4.1. Comparison to animal avoidance: Bridging the gap

The option to learn and execute an ER that terminates an aversive event (in this case, accumulating point loss) is a feature of the current task that makes it more closely related to animal avoidance paradigms, compared with prior human avoidance paradigms that do not consider the transition from ER to AR. As in the animal literature, almost all (over 90%) of human participants learned to execute an ER to terminate point loss, but there were individual differences in how well participants learned the AR.

In animal avoidance paradigms, such as rat lever-press avoidance, the inbred Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) strain, a model of behavioural inhibition, shows fast acquisition of the AR; this is apparent in both males and females compared to outbred Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (Beck et al. 2010; Servatius et al. 2008). Similarly, in the current study, humans with behavioural inhibition, assessed via a self-report questionnaire, showed facilitated acquisition of the AR (Figure 2B). This was not due simply to greater tendency to hide, because levels of hiding during the control period (W−) remained low in all individuals (Figure 2A). Similarly, in WKY rats, the greater expression of ARs is not easily attributable to a simple increase in non-specific responding (e.g., Beck et al. 2010). On the other hand, there tend to be no strain differences among rats in ability to escape the aversive event; similarly, in the current study, there was no effect of inhibited temperament on ERs (Figure 2B).

The second vulnerability factor examined in the current study was female sex. A large body of literature, not limited to lever-press paradigms, documents that female rats generally acquire active avoidance behaviours faster than their male counterparts (e.g., Beatty and Beatty 1970; Beck et al. 2010; Beck et al. 2011; Van Oyen, Walg, and Van De Poll 1981). In the current study, female sex was also associated with facilitated acquisition of the AR. Facilitated avoidance acquisition by female rats has sometimes been attributed to factors such as greater sensitivity to pain or suppression of startle responses linked to immune responses following exposure to shock (Beck and Servatius 2005, 2006); such explanations do not easily apply to the human data, where the aversive event was merely a point loss in a computer game. It is possible that, even when the to-be-avoided event is merely cognitive feedback, females may be more motivated to avoid this event. On the other hand, there is a large body of literature suggesting that females may simply be faster to acquire associations, not only in active avoidance paradigms but also in classical conditioning (Shors et al. 1998; Spence and Spence 1966; Wood and Shors 1998) and appetitive conditioning (Dreher et al. 2007; Lynch 2008; Saavedra et al. 1990), and such a tendency could also produce faster learning by females in the current task.

In the current study, the specific sex difference observed was longer AR duration in females than males. This component of the human task may be roughly comparable to response latency in the rat paradigms: that is, longer AR duration in the human paradigm typically means that the participant entered the safe area soon after W+ onset, and then remained there throughout the remainder of the warning period and the subsequent bomb period. Similarly, in rats, short response latency means that a rat has made the lever press response early in the warning period, soon after onset of W+. In rats, female sex is also associated with shorter response latency, but this may interact with strain, as well as with the presence of other factors such as a “safety signal” during the intertrial interval (e.g., Beck et al. 2010; Beck et al. 2011). Further experiments in both the animal and human paradigms may be useful to further explore these phenomena.

An important factor in the animal data that is not captured in the human data is the phenomenon of warm-up, a phenomenon whereby an animal exhibits poorer performance at the beginning of an experimental session when compared to its own performance level at the end of the prior session (Hoffman, Fleshler, and Chorny 1961). A core feature of the WKY phenotype is absence of warm-up; that is, unlike SD counterparts, WKY rats perform well even on the first trials of a daily session (e.g., Servatius et al. 2008). The human paradigm includes only one 24-trial session, and so it cannot address whether anxiety-vulnerable humans exhibit a similar lack of warm-up. Future experiments could potentially address this issue by allowing training to occur over multiple sessions.

Another feature of the current task is that it includes competing appetitive and aversive components (Aupperle et al. 2011), namely the conflicting demands to acquire points by shooting enemies (which requires that the participant’s spaceship remains in the central area) and to avoid point loss by hiding (during which the ability to shoot enemies is suspended). This feature is generally absent in the rat lever-press paradigm, since there is presumably little competing incentive for the rat to refrain from lever-press, as the physiological costs of the response are assumed to be fairly low. As a result, rats that acquire the AR tend to decrease response latency across trials; in the animal paradigm, this leads to faster termination of W+ and the trial. In contrast, in the current task, there is a clear incentive to delay the AR, and remain in the open to shoot spaceships and accrue points, until the last possible moment before the bomb arrives. The current data suggest that the tradeoff between these competing appetitive and aversive components is different in males and females, resulting in longer AR duration (i.e., generally faster latencies to respond) in the females. One could also expect to see associations between those two competing components and the TPQ subscales of HA and RD, that represent tendencies to avoid aversive situations or respond to rewarding stimuli, respectively (Cloninger, Przybeck, and Svrakic 1991). However, in the current study, neither HA nor RD score accounted for significant variability on AR duration, beyond the effect of sex. In any case, the conflict between the competing aversive and appetitive components of the current paradigm provides us with the opportunity to investigate a type of inhibited responding, which is clearly not optimal and could potentially be related to pathological inhibition and avoidance symptom in clinical populations. Several animal avoidance paradigms have explicitly manipulated approach vs. avoidance tendencies, e.g. execution of an AR interrupts or prevents access to food. It would be interesting to compare AR latencies in males vs. females in such a paradigm, to see if sex differences are obtained similar to those observed in the human participants.

4.2. Comparison with human literature

In agreement with our hypothesis, we found that behaviourally-inhibited temperament in the current study, as assessed by HA score on the TPQ, was associated with facilitated avoidance learning. Importantly, the two other personality dimensions assessed, NS and RD, did not predict any behavioural variable assessed, indicating specificity of the relationship between behavioural inhibition and avoidance in this paradigm. In particular, inhibited temperament was a reliable predictor of both AR rate and hiding during the warning period, but not of hiding during the control or bomb period, suggesting that inhibited personality is related to a facilitation in aversive associative learning (where one learns to predict an aversive stimulus), rather than to a general tendency to hide. One could argue that in the current task, W+ and W− serve as conditioned stimuli (CS) and the bomb as an unconditioned stimulus (US), and that behavioural inhibition could be associated with facilitated acquisition of classically-conditioned CS-US associations. Such an idea has been raised in prior literature that demonstrated faster stimulus-response learning by inhibited individuals on other computer-based tasks (Bódi et al. 2009; Corr, Pickering, and Gray 1995; Sheynin et al. 2013). A similar suggestion was also provided by a recent functional imaging study, which showed increased neural activation in inhibited individuals during the expectancy but not during the experience of an aversive event (Ziv et al. 2010).

Furthermore, although we found a lack of correlation between personality measures and AR duration, other factors may influence the balance between drives to approach and avoid, and this would be an avenue of further study. As suggested by the longer AR duration in female participants, sex might be one of those factors. Long AR duration in the current task prevent potential reward (point gain), while not serving to further decrease potential harm (i.e., each AR will prevent the same amount of point loss, regardless of its duration) and might represent a tendency to pathological responding. Hence, this finding is also consistent with previous literature that linked female sex with increased vulnerability to develop anxiety disorders and enhanced avoidance behaviour (McLean and Hope 2010; Pigott 1999).

4.3. Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations that should be addressed in future work. First, this study found performance differences that were dependent upon trial order, highlighting its importance in associative learning. However, post-hoc analyses that tested differences between the four trial orders, across the different periods and trials, did not reach adjusted significance. Moreover, when trial order was included as a predictor in the linear regressions, it did not account for any additional variability in the analyzed behaviour, suggesting that the reported associations with sex and personality were not driven by trial order. Nonetheless, any future study that uses similar task design should pay attention to the trial order that is being used. Secondly, since in the current task participants were intentionally not informed about the availability of safe areas, it is often not clear whether an absence of responding is due to the lack of knowledge about the availability of that response or whether it is the result of a voluntary choice not to execute that response. In future work, a post-hoc questionnaire might be used to ask about the information learned during the task.

A question about experience with video games might also be meaningful since such experience might bias performance. However, in our current population of young college students, it seems reasonable to believe that most participants had at least some prior exposure to computer games. Further, it appears unlikely that sex differences on AR duration were confounded with experience with computer games (Pfister 2011), since such duration assesses the timing of a learned response, rather than the learning itself.

Lastly, reporting the total points gained during the task would be valuable in future studies as a measure of overall performance, including the tradeoff between competing tendencies for hiding (avoid point loss) vs. remaining in the open (opportunity to gain points). Alternatively, it is possible that while there are individual differences on specific behavioural aspects of the task, factors such as sex and inhibited temperament would not significantly affect total point score, suggesting distinct strategies to achieve comparable overall outcome.

Future studies would also benefit from several possible manipulations. First, the effect of different response-outcome contingencies could be tested. For instance, in the current task, execution of an AR protects the participant from the aversive event but has no effect on presence of W+. However, it would be possible to have the AR also result in termination of W+. A similar experiment was carried out in rat lever-press avoidance, in which the AR caused omission of a foot-shock but either did or did not cause termination of W+ (Avcu et al. 2012). Results showed that, while females learned ARs efficiently under both conditions, a sub-group of male rats showed slower learning when the AR did not terminate W+. One interpretation of this finding is that termination of W+ provides additional feedback (indicating that the aversive event has been successfully averted), facilitating acquisition of the AR; it would be interesting to see if similar facilitation occurred in humans and, if so, whether males may be particularly affected.

Another limitation of the current paradigm is the lack of an extinction phase. Inhibited rats demonstrate slower extinction of ARs compared to uninhibited counterparts (Servatius et al. 2008). Importantly, human anxiety disorders are often characterized by impaired extinction learning, specifically, the extinction of aversive memories (Graham and Milad 2011). Many treatments for anxiety disorders involve extinction learning (e.g., exposure therapies; Rothbaum and Schwartz 2002), and factors that affect such learning have important clinical implication. The addition of an extinction phase to the current task and the analysis of individual behavioural differences, as well as potential therapeutic approaches, would be valuable.

Lastly, there is evidence from animal studies that addition of a signal that is present during periods of non-threat might facilitate avoidance learning (Beck et al. 2011). Specifically, it was shown that inhibited (male) rats acquire the AR slower when such a signal is absent, whereas female rats extinguish faster after training with such a signal. Whether such manipulations also affect male and female humans is still an open question and could be explored in the current paradigm. Moreover, it would be intriguing to test whether humans with anxiety vulnerabilities are more sensitive to such manipulations, similarly to female and inhibited rats.

4.4. Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use a cognitive task to examine escape-avoidance behaviour in humans. Consistent with prior results from the animal literature, acquisition of avoidance behaviours was facilitated in female participants and participants with inhibited temperament, both of which are vulnerability factors for anxiety disorders. Specifically, while most participants acquired ERs, females showed longer AR duration, whereas participants with inhibited temperament demonstrated higher AR rate. Such dissociation suggests differential mechanisms that confer exaggerated avoidance behaviour in humans. Further, because this task captures several important aspects of avoidance paradigms as commonly used in animal studies, the task may help bridge the gap between human and animal work and promote translational research. The addition of an extinction phase, as well as the manipulation of various properties of the paradigm (e.g., response-outcome contingencies, additional of a non-threat signal) are expected to parallel and further support published animal work, while also provide a direct tool for testing acquisition and maintenance of avoidance behaviour in healthy humans as well as psychiatric populations, including patients with anxiety disorders.

Highlights.

Adults were given a computer-based task based on animal escape-avoidance paradigms.

As in rats, inhibited temperament and female sex facilitated avoidance acquisition.

Inhibited participants showed higher rate of avoidance responses.

Females showed longer duration of avoidance responses.

The results help link animal avoidance models to anxiety vulnerability in humans.

Acknowledgements

For her assistance with data management, the authors wish to thank Yasheca Ebanks-Williams. This work was supported by the NSF/NIH Collaborative Research in Computational Neuroscience (CRCNS) Program, by NIAAA (R01 AA018737), by Award Number I01CX000771 from the Clinical Science Research and Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development, and by additional support from the Stress & Motivated Behavior Institute (SMBI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest

The authors affirm that they have no relationships that could constitute potential conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Jony Sheynin, Email: jony.sheynin@rutgers.edu.

Kevin D. Beck, Email: Kevin.Beck@va.gov.

Kevin C.H. Pang, Email: Kevin.Pang@va.gov.

Richard J. Servatius, Email: richard.servatius@va.gov.

Saima Shikari, Email: sshikari52@gmail.com.

Jacqueline Ostovich, Email: jjostovich@hotmail.com.

Catherine E. Myers, Email: Catherine.Myers2@va.gov.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: APA; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arcediano F, Ortega N, Matute H. A behavioural preparation for the study of human Pavlovian conditioning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology B. 1996;49:270–283. doi: 10.1080/713932633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aupperle RL, Sullivan S, Melrose AJ, Paulus MP, Stein MB. A reverse translational approach to quantify approach-avoidance conflict in humans. Behavioural Brain Research. 2011;225:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avcu P, Jiao X, Beck KD, Myers CE, Pang KCH, Servatius RJ. Avoidance acquisition in Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) and Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats: Shock expectancy or escape from fear?; Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting; 2012. 703.05/DDD49 [abstract]. [Google Scholar]

- Baeken C, De Raedt R, Ramsey N, Van Schuerbeek P, Hermes D, Bossuyt A, Leyman L, Vanderhasselt MA, De Mey J, Luypaert R. Amygdala responses to positively and negatively valenced baby faces in healthy female volunteers: influences of individual differences in harm avoidance. Brain Res. 2009;1296:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailer UF, Frank GK, Price JC, Meltzer CC, Becker C, Mathis CA, Wagner A, Barbarich-Marsteller NC, Bloss CS, Putnam K, Schork NJ, Gamst A, Kaye WH. Interaction between serotonin transporter and dopamine D2/D3 receptor radioligand measures is associated with harm avoidant symptoms in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Psychiatry Res. 2013;211:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty WW, Beatty PA. Hormonal determinants of sex differences in avoidance behavior and reactivity to electric shock in the rat. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1970;73:446–455. doi: 10.1037/h0030216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, Jiao X, Pang KC, Servatius RJ. Vulnerability factors in anxiety determined through differences in active-avoidance behavior. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2010;34:852–860. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, Jiao X, Ricart TM, Myers CE, Minor TR, Pang KC, Servatius RJ. Vulnerability factors in anxiety: Strain and sex differences in the use of signals associated with non-threat during the acquisition and extinction of active-avoidance behavior. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2011;35:1659–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, Servatius RJ. Stress-induced reductions of sensory reactivity in female rats depend on ovarian hormones and the application of a painful stressor. Horm Behav. 2005;47:532–539. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, Servatius RJ. Interleukin-1beta as a mechanism for stress-induced startle suppression in females. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1071:534–537. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bódi N, Kéri S, Nagy H, Moustafa A, Myers CE, Daw N, Dibo G, Takats A, Bereczki D, Gluck MA. Reward-learning and the novelty-seeking personality: a between- and within-subjects study of the effects of dopamine agonists on young Parkinson's patients. Brain. 2009;132:2385–2395. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byron Nelson J, del Carmen Sanjuan M. A context-specific latent inhibition effect in a human conditioned suppression task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (Hove) 2006;59:1003–1020. doi: 10.1080/17470210500417738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Diaz Y, Raggi VL, Fox NA. Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:928–935. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181ae09df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss JA, Blackford JU. Behavioral inhibition and risk for developing social anxiety disorder: a meta-analytic study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:1066 e1–1075 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A unified biosocial theory of personality and its role in the development of anxiety states. Psychiatric Developments. 1986;4:167–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. A proposal. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:573–588. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180093014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM. The Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire: U.S. normative data. Psychological Reports. 1991;69:1047–1057. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.3.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr PJ, Pickering AD, Gray JA. Personality and reinforcement in associative and instrumental learning. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995;19:47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MR, Jou RL, Ledoux JE, Phelps EA. Avoiding negative outcomes: tracking the mechanisms of avoidance learning in humans during fear conditioning. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;3:33. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.033.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher JC, Schmidt PJ, Kohn P, Furman D, Rubinow D, Berman KF. Menstrual cycle phase modulates reward-related neural function in women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2465–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605569104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Roche B. A contemporary behavior analysis of anxiety and avoidance. The Behavior Analyst. 2009;32:7–27. doi: 10.1007/BF03392173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymond S, Schlund MW, Roche B, Whelan R, Richards J, Davies C. Inferred threat and safety: symbolic generalization of human avoidance learning. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49:614–621. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essex MJ, Klein MH, Slattery MJ, Goldsmith HH, Kalin NH. Early risk factors and developmental pathways to chronic high inhibition and social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:40–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.07010051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone GL, Parker GB, Mitchell PB, Wilhelm KA, Malhi GS. Relationship between self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition and lifetime anxiety disorders in a clinical sample. Depress Anxiety. 2005;22:103–113. doi: 10.1002/da.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham BM, Milad MR. The study of fear extinction: implications for anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:1255–1265. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11040557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudino OG. Behavioral inhibition and risk for posttraumatic stress symptoms in Latino children exposed to violence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41:983–992. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9731-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HS, Fleshler M, Chorny H. Discriminated bar-press avoidance. J Exp Anal Behav. 1961;4:309–316. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1961.4-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamustafalioglu OK, Zohar J, Guveli M, Gal G, Bakim B, Fostick L, Karamustafalioglu N, Sasson Y. Natural course of posttraumatic stress disorder: a 20-month prospective study of Turkish earthquake survivors. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;67:882–889. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, Chen SX, Mitchell CJ, Weidemann G. Competition between an avoidance response and a safety signal: evidence for a single learning system. Biol Psychol. 2013;92:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, Mitchell CJ, Minard E, Brady A, Menzies RG. Safety behaviours preserve threat beliefs: Protection from extinction of human fear conditioning by an avoidance response. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:716–720. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, Saunders JC, Weidemann G, Mitchell CJ. Evidence for expectancy as a mediator of avoidance and anxiety in a laboratory model of human avoidance learning. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology (Hove) 2008;61:1199–1216. doi: 10.1080/17470210701503229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ. Acquisition and maintenance of cocaine self-administration in adolescent rats: effects of sex and gonadal hormones. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:237–246. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardaga S, Hansenne M. Relationships between Cloninger’s biosocial model of personality and the behavioral inhibition/approach systems (BIS/BAS) Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:715–722. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall RD, Turner JB, Lewis-Fernandez R, Koenan K, Neria Y, Dohrenwend BP. Symptom patterns associated with chronic PTSD in male veterans: new findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2006;194:275–278. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000207363.25750.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Hope DA. Subjective anxiety and behavioral avoidance: Gender, gender role, and perceived confirmability of self-report. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2010;24:494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molet M, Leconte C, Rosas JM. Acquisition, extinction and temporal discrimination in human conditioned avoidance. Behavioural Processes. 2006;73:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, Mallonee S, McMillen JC, Spitznagel EL, Smith EM. Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:755–762. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.8.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell ML, Elliott P, Lau W, Creamer M. PTSD symptom trajectories: from early to chronic response. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:601–606. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare WP. Open field, learned helplessness, conditioned defensive burying, and forced-swim tests in WKY rats. Physiol Behav. 1994;55:433–439. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)90097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister R. Gender effects in gaming research: a case for regression residuals? Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:603–606. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigott TA. Gender differences in the epidemiology and treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 18):4–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raia CP, Shillingford SW, Miller HL, Jr, Baier PS. Interaction of procedural factors in human performance on yoked schedules. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2000;74:265–281. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2000.74-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, Bolduc-Murphy EA, Faraone SV, Chaloff J, Hirshfeld DR, Kagan J. Behavioral inhibition in childhood: a risk factor for anxiety disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1993;1:2–16. doi: 10.3109/10673229309017052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Schwartz AC. Exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychother. 2002;56:59–75. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra MA, Abarca N, Arancibia P, Salinas V. Sex differences in aversive and appetitive conditioning in two strains of rats. Physiol Behav. 1990;47:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servatius RJ, Jiao X, Beck KD, Pang KC, Minor TR. Rapid avoidance acquisition in Wistar-Kyoto rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2008;192:191–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheynin J, Shikari S, Gluck MA, Moustafa AA, Servatius RJ, Myers CE. Enhanced avoidance learning in behaviorally inhibited young men and women. Stress. 2013;16:289–299. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2012.744391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ, Lewczyk C, Pacynski M, Mathew PR, Pickett J. Stages of estrous mediate the stress-induced impairment of associative learning in the female rat. Neuroreport. 1998;9:419–423. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence KW, Spence JT. Sex and anxiety differences in eyelid conditioning. Psychol Bull. 1966;65:137–142. doi: 10.1037/h0022982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JE, Sullman MJ. What does the Driving and Riding Avoidance Scale (DRAS) measure? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:504–510. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oyen HG, Walg H, Van De Poll NE. Discriminated lever press avoidance conditioning in male and female rats. Physiol Behav. 1981;26:313–317. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(81)90028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Yu L, Arnold SE, Bennett DA. Harm avoidance and risk of Alzheimer's disease. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:690–696. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182302ale. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Hoyer J. Generalized anxiety disorder: nature and course. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 11):15–19. discussion 20-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood GE, Shors TJ. Stress facilitates classical conditioning in males, but impairs classical conditioning in females through activational effects of ovarian hormones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4066–4071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.4066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Ho SM. Risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder among survivors after the 512 Wenchuan earthquake in China. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziv M, Tomer R, Defrin R, Hendler T. Individual sensitivity to pain expectancy is related to differential activation of the hippocampus and amygdala. Human Brain Mapping. 2010;31:326–338. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]