Abstract

Mutations in PSEN1 are the most common cause of autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD). We describe an African-American woman with a family history consistent with FAD who began to have cognitive decline at age 50. Her clinical presentation, MRI, FDG- and PIB-PET scan findings were consistent with AD and she was found to have a novel I238M substitution in PSEN1. As this mutation caused increased production of Aβ42 in an in-vitro assay, was not present in two population databases, and is conserved across species, it is likely to be pathogenic for FAD.

Keywords: autosomal dominant, Alzheimer’s disease, PSEN1, Presenilin-1, familial, PIB-PET, African, gamma-secretase, in-vitro, Aβ42

Introduction

Alterations in the PSEN1 gene are the most common mutations causing autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD) with 185 distinct pathogenic PSEN1 mutations being reported (www.molgen.ua.ac.be/ADMutations). PSEN1 serves as the catalytic core for the γ-secretase complex and mutations modify how γ-secretase cleaves amyloid precursor protein (APP)(1), increasing the relative or absolute levels of the 42-amino acid beta-amyloid derivative of APP(2) (Aβ42). Though there is good evidence supporting pathogenicity of most PSEN1 mutations, the pathogenesis remains uncertain for some(3). We describe a novel PSEN1 mutation (I238M substitution) in a patient with clinically probable AD with biomarker evidence supporting a diagnosis of AD and a family history consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance and demonstrate that the mutation increases Aβ42 when expressed in in-vitro.

Materials and Methods

The index patient was seen for clinical care and then enrolled in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) at UCLA which is a comprehensive study of persons with or at-risk for inheriting FAD mutations. DIAN subjects undergo clinical, genetic and biochemical assessments, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) scanning with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) and Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB)(4). PET scans were processed as previously described(5). Volumetric MRI analyses were performed using NeuroQuant Software (CoreTechs Labs, LaJolla, CA). Genetic testing was initially performed through Athena Diagnostics (Worcester, MA) such that the entire open reading frame of the PSEN1 gene was sequenced and then replicated in a research lab with an independently collected sample.

To examine the effect of the PSEN1 variant on APP processing, the I238M mutation was introduced by site-directed mutagenesis into a cDNA construct containing wild-type PSEN1 using a Quick Change II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene)(6). Human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells were transiently transfected with mutant or wild-type PSEN1 vectors or control vector (GFP) and human APP cDNA with the Swedish mutation for 48 hours. The culture medium was replaced with fresh medium and incubated for 16 hrs. Secreted Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were measured in the culture media by ELISA with specific antibodies recognizing Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen).

Results

The index patient is a right-handed African-American woman who presented with progressive cognitive deterioration beginning at 50 years of age. Her only past medical history was dyspepsia and migraine headaches since childhood. Her symptoms started with short-term memory loss, poor concentration and inability to multi-task. She also had significant symptoms of anxiety that preceded her cognitive decline by years. When first evaluated at age 51, her Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) score was 27/30, losing 3 points on delayed recall. By age 52 she had difficulties with instrumental and basic activities of daily living and had an MMSE score of 20/30. Subsequent evaluation at age 53 revealed a MMSE of 17/30 and severely impaired verbal memory. On an orally presented 10-word shopping list memory test she recalled a maximum of 6 over 5 trials and after a 15-minute delay recalled none and had 3 intrusions. On recognition testing she recognized 9/10 but had 10 false positive errors. She also demonstrated impaired comprehension and reduced category and letter fluency, generating 7 animals and 9 words beginning with the letter “F” in one minute. On clock-drawing, she placed the numbers and hands incorrectly. Neurological examination showed no evidence of parkinsonism, myoclonus, cerebellar signs or abnormal gait. Ideomotor apraxia was noted on both upper limbs. Over time she lost sense of direction and had reduced ability to cook associated with leaving the stove on and ultimately needed supervision for personal hygiene. At age 54 she had an MMSE score of 8/30, and when last seen at age 56 she scored 6/30 on the MMSE and was otherwise unable to complete neuropsychological testing and obtained a Clinical Dementia Rating scale(7) score of 2.0.

The patient’s father was diagnosed with AD in his late fifties and died at age 65. Her paternal aunt and grandmother also died with dementia, but the age of onset and age at death was uncertain. The patient is the oldest of 6 siblings and none were thought to have cognitive symptoms at the time the patient was last seen.

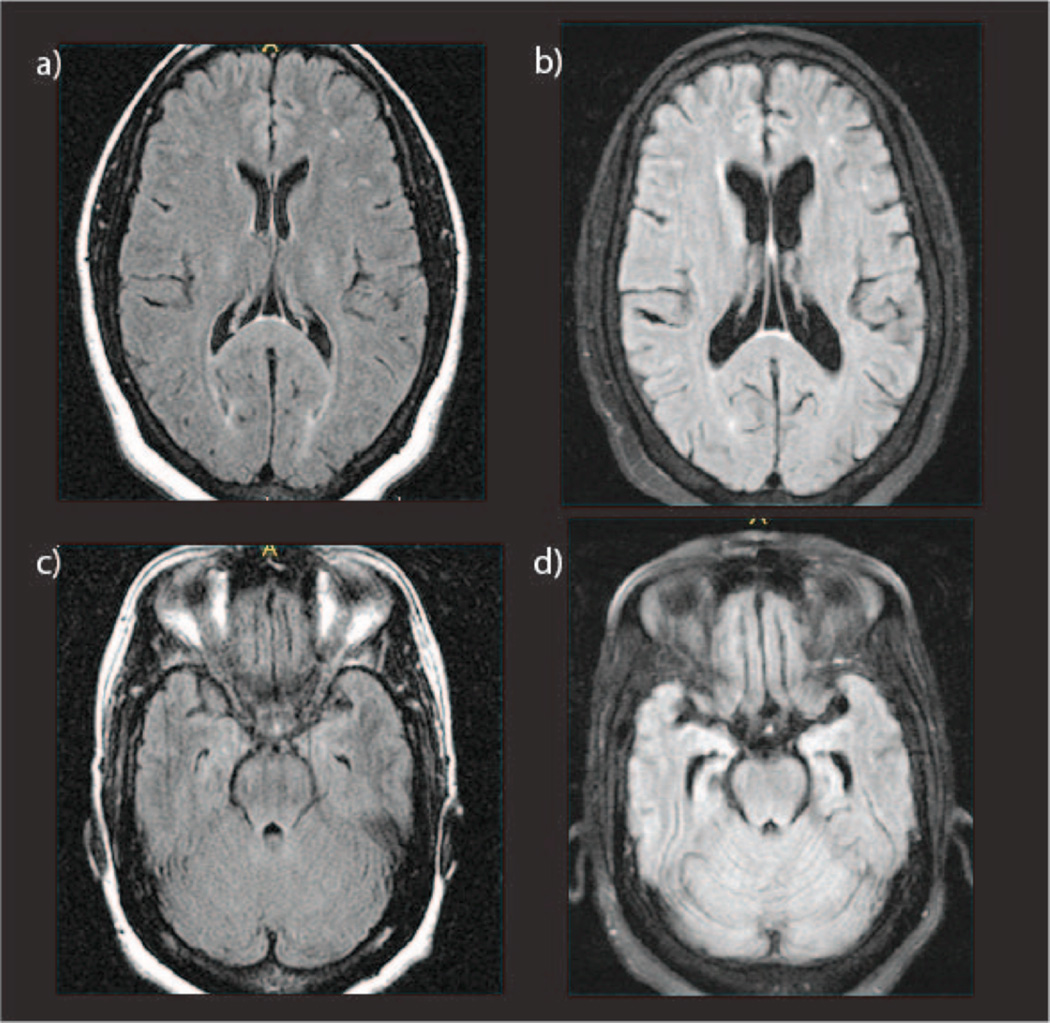

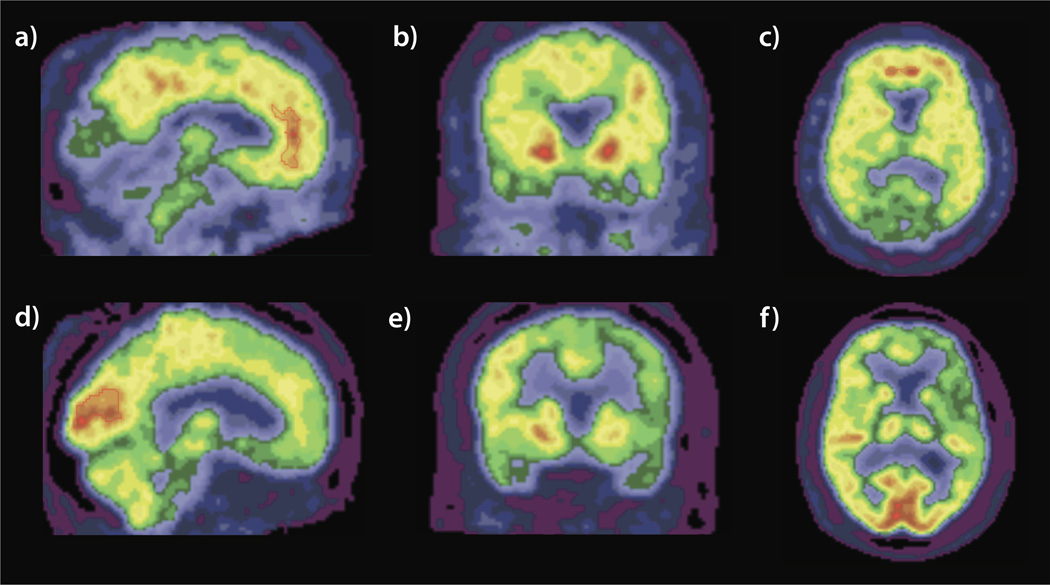

Clinical brain MRI (Figure 1) and SPECT scans performed at age of 51 were thought to be within normal limits. Biochemical screening was negative for vasculitic, metabolic or infectious causes. At age 55 a research MRI revealed mild atrophy of the left hemisphere, with widening of the Sylvian fissure, and hippocampal volumes less than 1% and inferior lateral ventricles > 99% the size of age matched control values. A repeat clinical MRI performed at age 56 showed cerebral atrophy relative to her first MRI (Figure 1). At this same time PIB-PET imaging, referenced to the brainstem, revealed a substantial increase in signal in multiple areas including the precuneus, temporal, prefrontal, and parietal lobes as well as the caudate that was maximal in the anterior cingulate (AC) gyrus (ratio of signal in AC to the brainstem was 3.4 relative to 1.3 in controls, Figure 2). FDG-PET revealed hypometabolism predominantly in the left hemisphere, involving the frontal and temporal lobes (left superior temporal lobe SUVR 0.85, and ratio of left superior temporal lobe SUVR to right of 0.87, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

T1-weighted FLAIR MRI scans at age 51 (a and c) when the subject was mildly symptomatic and at age 56 (b and d) at which time the subject had a CDR score of 2. Interval cerebral atrophy is evident.

Figure 2.

Sagittal (a), coronal (b), and axial (c) views of the PIB-PET scan of the index patient at age 55. Note the positive PIB signal in the anterior cingulate gyrus, precuneus, pallidum, and prefrontal cortex. Sagittal (d), coronal (e), and axial (f) views of the FDG-PET scan. Note the global hypometabolism particularly in the left frontal and bilateral temporal lobes with relative sparing of the occipital lobes. Scans are in radiological orientation.

Sequencing of the PSEN1 gene revealed a cytosine to guanidine point mutation at nucleotide position 714. This causes an isoleucine to methionine substitution at codon 238 (I238M) in the fifth transmembrane region of PS1. There have been no mutations previously reported at this codon though two mutations at nearby codon 237(8, 9) and one at codon 239(10) have been reported in association with FAD. The I238M sequence variant was not found in the preliminary data release of the 1000 Genomes Project (http://www.1000genomes.org), V4 of the Pilot3 Release, dated 2011-08-04. No variants were reported at this position among 694 subjects of multiple ethnicities including African Americans. In addition, this variant was not found in the NHBLI GO sequencing project (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/) that includes 6,503 people including 4,300 Americans of European descent and 2,203 African-Americans. This variant was also not found in series of 130 Africans of varied origins(11). The isoleucine in this region is conserved in human PSEN2 as well as in the PSEN1 homologue in zebrafish, chickens, mice, macaques and other mammalian species. Her apolipoprotein E genotype was ε3/ε3.

The assay analyzing the effect of the I238M mutation on APP metabolism confirmed the presence of elevated levels of Aβ40, Aβ42 and the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio relative to that produced by wild-type PS1. Levels of Aβ42 produced by cells in which the I238M mutation was introduced were 2.4× those produced by cells with WT PS1 (p = 4.5 × 10−8(12)). This was previously reported in association with another novel PSEN1 mutation in Figure 3 in Ringman et al, 2011(12).

Discussion

We describe a case of young onset AD in an African-American woman with a family history consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance associated with a novel PSEN1 mutation. The age of onset in the index patient appeared to be at least 5 years before that of her father’s. Though onset age within families with PSEN1 mutations tends to be consistent, variation such as this is not unusual and unfortunately the ages of symptom onset in other family members are unknown. The index patient’s presentation was fairly typical for AD, starting with an episodic memory deficit with gradual progression to involvement of multiple cognitive domains and impairment in activities of daily living. Significant anxiety in the current case highlights previous observations of early neuropsychiatric symptoms associated with PSEN1 mutations(12, 13). The case for pathogenicity of the I238M PSEN1 mutation is further supported by in-vitro demonstration of increased production of the Aβ protein. According to the algorithm of Guerreiro et al, this variant meets criteria for being probably pathogenic(11).

There are limitations to this report. Firstly, it would be ideal to know the age of disease onset in other affected family members and verify co-segregation of the I238M mutation with the disease. Unfortunately, there were no other affected family members to test and no other unaffected family members were interested in research involvement. Secondly, demonstration of characteristic AD changes in cerebrospinal fluid and autopsy verification would provide further evidence for AD pathology. However, the atrophy patterns observed on MRI and FDG- and PIB-PET findings provide biomarker evidence for the presence of AD pathology.

To our knowledge, this is only the third pathogenic PSEN1 mutation described in persons of African or African-American origin(14, 15) and only the fourth associated with FAD in this population(16). The study of variants in FAD genes in persons of African ancestry is of interest in that genetic diversity is greatest in this population(11). Despite this, the I238M PSEN1 substitution was not found in 2,303 African-Americans.

In conclusion, we describe a novel I238M substitution in the PSEN1 gene that is associated with a case of early onset AD with a positive family history and has the effect of increasing Aβ42 production in-vitro. We recommend genetic counseling for family members of AD patients found to have the I238M mutation in PSEN1.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by PHS K08 AG-22228, The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network NIA U19 AG032438, the UCLA Clinical Translational Research Institute 1UL1-RR033176, Alzheimer's Disease Research Center Grant P50 AG-16570, General Clinical Research Centers Program M01-RR00865, and the Easton Consortium for Alzheimer's Disease Drug Discovery and Biomarker Development.

References

- 1.Berezovska O, et al. Familial Alzheimer's disease presenilin 1 mutations cause alterations in the conformation of presenilin and interactions with amyloid precursor protein. J Neurosci. 2005;25(11):3009–3017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0364-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheuner D, et al. Secreted amyloid beta-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer's disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 1996;2:864–870. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee P, Medina L, Ringman JM. The Thr354Ile substitution in PSEN1: disease-causing mutation or polymorphism? Neurology. 2006;66(12):1955–1956. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000219762.28324.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris JC, et al. Developing an international network for Alzheimer research: The Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Clin Investig (Lond) 2012;2(10):975–984. doi: 10.4155/cli.12.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bateman RJ, et al. Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(9):795–804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hecimovic S, et al. Mutations in APP have independent effects on Abeta and CTFgamma generation. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17(2):205–218. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(Suppl 1):173–176. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297004870. discussion 177-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sodeyama N, et al. Very early onset Alzheimer's disease with spastic paraparesis associated with a novel presenilin 1 mutation (Phe237Ile) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71(4):556–557. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.4.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen JC, et al. Early onset familial Alzheimer's disease: Mutation frequency in 31 families. Neurology. 2003;60(2):235–239. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000042088.22694.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llado A, et al. A novel PSEN1 mutation (K239N) associated with Alzheimer's disease with wide range age of onset and slow progression. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(7):994–996. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerreiro RJ, et al. Genetic screening of Alzheimer's disease genes in Iberian and African samples yields novel mutations in presenilins and APP. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(5):725–731. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringman JM, et al. Biochemical, neuropathological, and neuroimaging characteristics of early-onset Alzheimer's disease due to a novel PSEN1 mutation. Neurosci Lett. 2011;487(3):287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ringman JM, et al. Female preclinical presenilin-1 mutation carriers unaware of their genetic status have higher levels of depression than their non-mutation carrying kin. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(3):500–502. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2002.005025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heckmann JM, et al. Novel presenilin 1 mutation with profound neurofibrillary pathology in an indigenous Southern African family with early-onset Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 1):133–142. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rippon GA, et al. Presenilin 1 mutation in an african american family presenting with atypical Alzheimer dementia. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(6):884–888. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards-Lee T, et al. An African American family with early-onset Alzheimer disease and an APP (T714I) mutation. Neurology. 2005;64(2):377–379. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149761.70566.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]