Abstract

The potent profibrotic cytokine TGFβ induces connective tissue growth factor (CCN2/CTGF) is induced in fibroblasts in a fashion sensitive to SB-431542, a specific pharmacological inhibitor of TGFβ type I receptor (ALK5). In several cell types, TGFβ induces CCN1 but suppresses CCN3, which opposes CCN1/CCN2 activities. However, whether SB-431542 alters TGFβ-induced CCN1 or CCN3 in human foreskin fibroblasts in unclear. Here we show that TGFβ induces CCN1 but suppresses CCN3 expression in human foreskin fibroblasts in a SB-431542-sensitive fashion. These results emphasize that CCN1/CCN2 and CCN3 are reciprocally regulated and support the notion that blocking ALK5 or addition of CCN3 may be useful anti-fibrotic approaches.

Keywords: Fibroblasts, CCN1, CCN2, cyr61, ctgf, TGFbeta, ALK5

Introduction

Connective tissue growth factor (CCN2, CTGF), a member of the CCN family of proteins (Bork 1993; Perbal 2013), is not normally expressed in connective tissue but is potently upregulated in tissue repair and fibrosis (Blom et al. 2001; Leask and Abraham 2006; Leask et al. 2009). In fibroblasts, CCN2 is induced by the fibrogenic cytokine transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) (Grotendorst et al. 1996; Holmes et al. 2001; van Beek et al. 2006) in a fashion sensitive to SB-431542, a specific TGFβ type I receptor (ALK4/5/7) inhibitor (Thompson et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2011). CCN2 enhances the profibrotic effects of TGFβ and has been implicated in fibrosis of most human tissues (Ito et al. 1998; Paradis et al. 1999; Mori et al. 1999; Lawrencia et al. 2009; Shi-wen et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2011).

Other members of the CCN family are also implicated in tissue repair and fibrosis. For example, CCN1, which has similar in vitro functions to CCN2 (Chen et al. 2011) is also induced in tissue repair and fibrosis as well as, in several cell types, by TGFβ (Leivonen et al. 2005; Jun and Lau 2010; Liu et al. 2014). Similarly, CCN3, which has anti-fibrotic functions opposing CCN2 is suppressed by TGFβ in a variety of cell types (Riser et al. 2009, 2012; Lemaire et al. 2011; Tran et al. 2011; Abd El Kadr et al. 2013). Although in fibroblasts TGFβ generally signals through TGFβ type I receptor (ALK5) (Leask and Abraham 2004) and mediates TGFβ-induced CCN2 expression in gingival and dermal fibroblasts (Thompson et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2011), it has yet to be demonstrated that ALK5 inhibition blocks TGFβ-induced CCN1 expression or TGFβ-suppressed CCN3 expression in human dermal fibroblasts,

In this report, we test the effect of the ALK5 inhibitor SB-4311542 on basal and TGFβ-induced CCN1 and CCN3 expression in human foreskin dermal fibroblasts. Our data provide potentially useful information aimed at developing novel therapeutic strategies to combat fibrosis.

Materials and methods

Isolation and culturing of fibroblasts

Human foreskin fibroblasts (ATCC) were cultured in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10 % FBS and 1 % antibiotic/anti-mycotic solution (Invitrogen, Burlington, Ontario). Cells were plated onto a six well plate at a density of 60000 cells/well, cultured for 24 h at 37 °C, serum-starved (in low glucose DMEM, 0.5 % FBS) for 24 h, pre-treated for 45 min with DMSO or TGFβ type I (ALK4/5/7) inhibitor (SB-431542, Calbiochem, 10 μM) prior to the addition of TGFβ1 (R and D Systems, 1 ng/ml) for 6 h (for RNA) or 24 h (for protein analysis)

Real time RT-PCR

Experiments were conducted essentially as previously described (Pala et al. 2008; Thompson et al. 2011). RNA was harvested using Tri Reagent (Sigma) and quantified. Forty ng of RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified using TaqMan (Applied Biosystems) in a 15 μl reaction containing Assays on Demand primers for CCN2, CCN1 or CCN3 (Applied Biosystems) and 6-carboxyfluroscein-labeled TaqMan MGB probe. RNA levels were assessed using reverse Transcriptase qPCR One-step Mastermix (Applied Biosystems) and the ABI Prism 7900 HT sequence detector (Perkin-Elmer-Cetus, Vaudreuil, QC). All Assays on Demand primers are designed and tested for specificity by the manufacturer. Samples were run in triplicate, and expression values were standardized to control values from 18S primers using the ΔΔCt method. Experiments were repeated thrice, and statistical analysis was done on data obtained from these biological replicates using one way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test on GraphPad, and p values less that 0.05 were taken to be significant.

Western blot analysis

Protein was harvested using Radioimmuno-precipitation Assay (RIPA) lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 % Triton-X, 1 % deoxycholate, 0.1 % SDS, 2 mM EDTA) and quantified by a kit (BCA, Sigma) as described by the manufacturer’s. Equal amounts of cell lysate (50 μg) were subjected to SDS/PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose (Biorad), blocked for 1 h in 5 % non fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.01 % Tween-20, and incubated with anti-CCN2 (1:400; Santa Cruz), anti-CCN1 (1:1000 Santa Cruz), anti-CCN3 (1:2000 R and D Systems) or anti-β-actin (1:8000, Sigma) antibodies diluted in the same solution overnight at 4 °C. When indicated, rCCN3 (1.5 ng, R and D Systems) was added as a control. Blots were washed 3 times for 5 min with Tris-buffered saline with 0.01 % Tween-20 and developed by the application of appropriate horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch) and ECL™ Western blot detection reagents (Amersham Bioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and visualized using X ray film (Kodak).

Results

The ALK4/5/7 inhibitor SB-431542 reduces TGFβ-induced CCN2 and CCN1 but suppresses CCN3 mRNA and protein expression in human foreskin fibroblasts

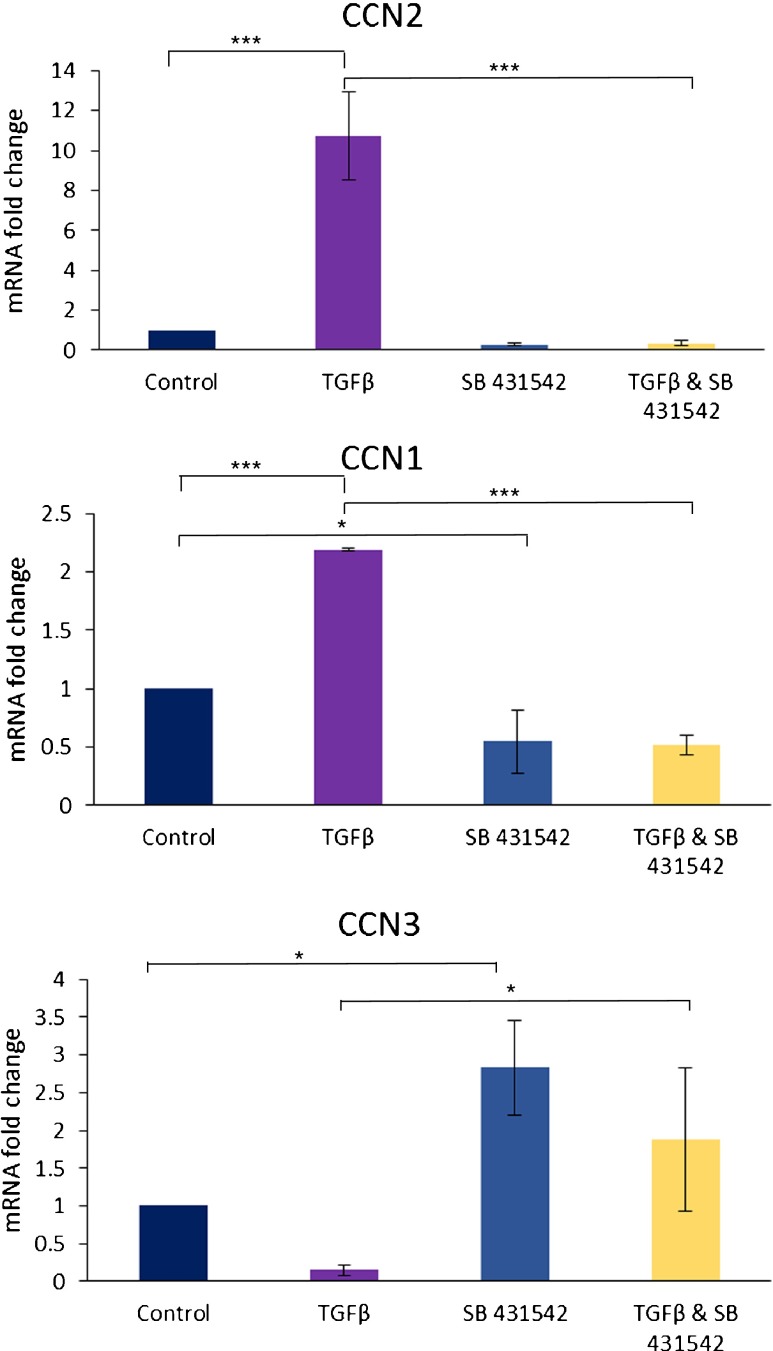

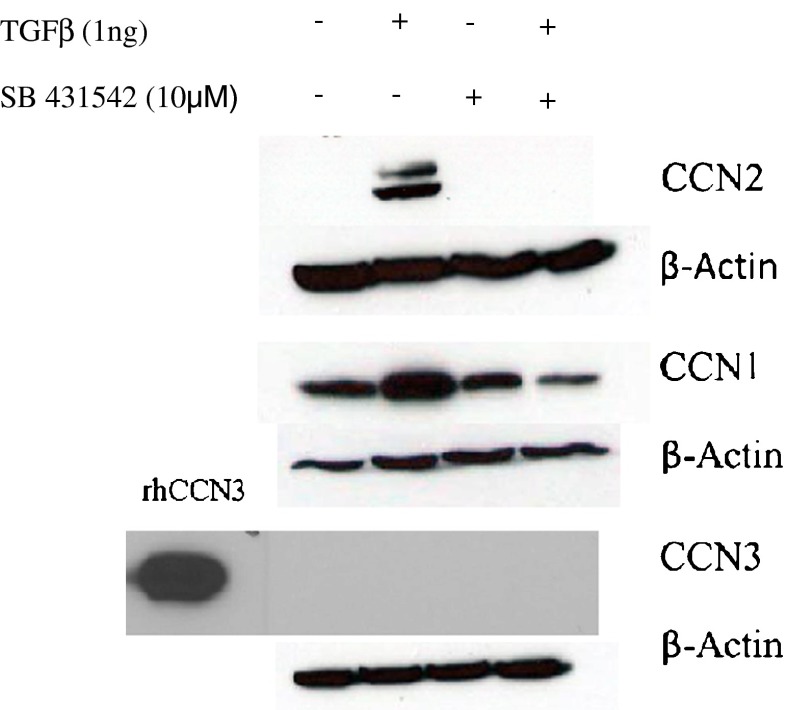

To begin to determine whether ALK4/5/7 inhibition altered TGFβ-induced CCN1 and CCN3 mRNA expression, we cultured dermal fibroblasts for 24 h in 0.5 % serum. Cells were then treated for 45 min with or without SB-431542 and then treated for additional 6 h with or without TGFβ1. RNA was then extracted. As a control, samples were initially subjected to real-time PCR analysis to detect CCN2 and 18S transcripts. Compared with 18S mRNA expression, as expected based on previous data with gingival and dermal fibroblasts (Thompson et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2011), in the presence of DMSO, TGFβ1-induced CCN2 mRNA in human dermal fibroblasts (Fig. 1) but addition of the ALK4/5/7 blocked TGFβ1−induced CCN2 mRNA expression indicating that signaling (Fig. 1). We then subjected RNA samples to real-time PCR analysis to detect CCN1, CCN3 and 18S transcripts. ALK4/5/7 inhibition reduced basal and TGFβ1-induced CCN1 mRNA expression (Fig. 1). Conversely ALK4/5/7 inhibition enhanced basal CCN3 mRNA expression and reduced the ability of TGFβ1 to suppress CCN3 mRNA expression (Fig. 1). Similarly, the ability of TGFβ1 to induce CCN2 and CCN1 protein was blocked by ALK4/5/7 inhibition (Fig. 2). Although we were readily able to detect recombinant CCN3 expression in dermal foreskin fibroblasts, endogenous CCN3 was not detectable by our Western blotting methods (Fig. 2). Collectively, these results suggest that ALK4/5/7 mediates the ability of TGFβ to induce CCN2/CCN1 and suppress CCN3 expression (at least at the mRNA level) in human dermal foreskin fibroblasts.

Fig. 1.

Inhibiting ALK5 decreased TGFβ-induced CCN1 and increases CCN3 mRNA expression. Human foreskin dermal fibroblasts were serum-starved overnight, incubated for 45 min with DMSO or SB-431542 (10 μM) prior to treatment for 6 h with or without TGFβ1 (1 ng/ml). Total RNAs were harvested and subjected to real time RT-PCR. Each sample was conducted in triplicate. CCN2, CCN1 and CCN3 expression were detected and normalized to that of 18S using the ΔΔCt method. Columns, Average (mRNA fold change compared to DMSO control) of triplicate samples performed on cells derived from each of three different experiments (N = 3; Averages +/-SEM are shown; One way ANOVA * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.001, *** p < 0.0001)

Fig. 2.

Inhibiting ALK5 decreased TGFβ-induced CCN1 protein expression: Western blot analysis Human foreskin dermal fibroblasts were serum-starved overnight, incubated for 45 min with DMSO or SB-431542 (10 μM) prior to treatment for 24 h with or without TGFβ1 (1 ng/ml). rCCN3 = recombinant CCN3 control. Protein was harvested and subjected to western blot analyses with anti-CCN1, anti-CCN2 and anti-CCN3 and anti-βactin antibodies. Experiments were conducted thrice, representative Western blots are shown

Discussion

TGFβ generally acts on fibroblasts via the Smad/TGFβ type I receptor (ALK5) pathway (Leask and Abraham 2004). It has previously been shown using a variety of fibroblast types that that Smad3/4/ALK5 mediates TGFβ-induced CCN2 expression (Holmes et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2002; Leask et al 2001, 2003; Thompson et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2011). Of the CCN family, CCN1 is believed to be regulated in a similar fashion to CCN2, whereas CCN3 is reciprocally regulated relative to both CCN1 and CCN2. For example, in several cell types, TGFβ induces CCN1 but suppresses CCN3. However, no report has directly examined the effect of ALK4/5/7 inhibition on TGFβ-induced CCN1 or TGFβ-induced expression. For example, the ability of ALK4/5/7 inhibition to affect TGFβ-induced CCN1 or TGFβ-suppressed CCN3 expression in human dermal fibroblasts has not been examined until this report. Moreover, whether ALK5 inhibition in general modifies TGFβ signaling in gingival fibroblasts has not yet been evaluated. As there is currently no sufficient treatment for fibrosis obtaining a greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying fibroblast activation, including the basis of CCN1, 2 and 3 expression, is an essential first step in the understanding of how to control fibrogenesis in general.

Our results showing that ALK4/5/7 inhibition blocks TGFβ-induced CCN2 and CCN1 expression in human dermal foreskin fibroblasts are consistent with several other published observations. For example, ALK5 inhibition reduces CCN2 overexpression in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis (Higashiyama et al. 2007). TGFβ-induced CCN2 expression in human Tenon’s capsule fibroblasts derived from the eye (Xiao et al. 2009), SB-4311542 blocked TGFβ-induced CCN2 expression in rat hepatic stellate cells (Leask et al. 2008) and TGFβ-induced CCN2 expression in gingival and dermal fibroblasts (Thompson et al. 2011; Guo et al. 2011). TGFβ also signals through non-canonical (for example MAP kinase) pathways (Leask and Abraham 2004); whether TGFβ induces CCN1 and suppresses CCN3 through the same non-canonical pathways through which TGFβ induces CCN2 is unclear. Also, the involvement of other TGFβ superfamily members in CCN family gene regulation needs to be investigated. It is interesting that although we were able to detect CCN3 mRNA by real time PCR and recombinant CCN3 by Western blot, but not endogenous CCN3 in human foreskin fibroblasts. In parallel studies, CCN3 is detectable in adult dermal fibroblasts (not shown) suggesting that, at a protein level, CCN3 protein might not be expressed in human foreskin fibroblasts.

It is interesting to note that although knock-in mice harboring a point mutation in CCN1 that specifically alters cellular inflammatory responses promotes wound healing by attenuating fibrotic responses (Jun and Lau 2010), strategies using antibodies to block action of the entire CCN1 protein block fibrosis in a model of kidney fibrosis (Lai et al. 2013). Thus it remains unclear whether CCN1 promotes or suppresses fibrosis; the answer to this question may entirely depend on the context examined. Nonetheless, our data that, at least at the mRNA level, that in fibroblasts CCN3 is regulated in a reciprocal fashion to CCN1 and CCN2 are consistent with previous results in other systems and also with the hypothesis that CCN3 may suppress CCN1/CCN2-dependent activities (Riser et al. 2009; Perbal 2013

In summation, our results emphasize that notion that ALK4/5/7 inhibition or rCCN3 could, in principle, be an appropriate method of suppressing fibroblast activation.

Acknowledgments

Our work is supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Scleroderma Society of Ontario. KT was the recipient of a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Summer Studentship.

References

- Abd El Kader T, Kubota S, Janune D, Nishida T, Hattori T, Aoyama E, Perbal B, Kuboki T, Takigawa M. Anti-fibrotic effect of CCN3 accompanied by altered gene expression profile of the CCN family. J Cell Commun Signal. 2013;7:11–18. doi: 10.1007/s12079-012-0180-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom IE, Goldschmeding R, Leask A (2001) Gene regulation of connective tissue growth factor: new targets for antifibrotic therapy? Matrix Biol 21:473–482 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bork P. The modular architecture of a new family of growth regulators related to connective tissue growth factor. FEBS Lett. 1993;327(2):125–130. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80155-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Mo FE, Lau LF (2011) The angiogenic factor Cyr61 activates a genetic program for wound healing in human skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 276:47329–47337 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen Y, Blom IE, Sa S, Goldschmeding R, Abraham DJ, Leask A. CTGF expression in mesangial cells: involvement of SMADs, MAP kinase and PKC. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1149–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotendorst GR, Okochi H, Hayashi N. A novel transforming growth factor beta response element controls the expression of the connective tissue growth factor gene. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo F, Carter DE, Leask A. Mechanical tension increases CCN2/CTGF expression and proliferation in gingival fibroblasts via a TGFβ-dependent mechanism. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama H, Yoshimoto D, Kaise T, Matsubara S, Fujiwara M, Kikkawa H, Asano S, Kinoshita M. Inhibition of activin receptor-like kinase 5 attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A, Abraham DJ, Sa S, Shiwen X, Black CM, Leask A. CTGF and SMADs, maintenance of scleroderma phenotype is independent of SMAD signaling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10594–10601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito Y, Aten J, Bende RJ, Oemar BS, Rabelink TJ, Weening JJ, Goldschmeding R. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in human renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 1998;53:853–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.1998.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun JI, Lau LF. The matricellular protein CCN1 induces fibroblast senescence and restricts fibrosis in cutaneous wound healing. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:676–685. doi: 10.1038/ncb2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CF, Chen YM, Chiang WC, Lin SL, Kuo ML, Tsai TJ. Cysteine-rich protein 61 plays a proinflammatory role in obstructive kidney fibrosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56481. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrencia C, Charrier A, Huang G, Brigstock DR. Ethanol-mediated expression of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) in mouse pancreatic stellate cells. Growth Factors. 2009;27:91–99. doi: 10.1080/08977190902786319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Abraham DJ. The control of TGFβ signaling in wound healing and fibrosis. FASEB J. 2004;18:816–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1273rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Abraham DJ. All in the CCN family: essential matricellular signaling modulators emerge from the bunker. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4803–4810. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Sa S, Holmes A, Shiwen X, Black CM, Abraham DJ. The control of CTGF (ccn2) gene expression in normal and scleroderma fibroblasts. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:180–183. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.3.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Holmes A, Black CM, Abraham DJ. Connective tissue growth factor gene regulation. Requirements for its induction by transforming growth factor-beta 2 in fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13008–13015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Chen S, Pala D, Brigstock DR. Regulation of CCN2 mRNA expression and promoter activity in activated hepatic stellate cells. J Cell Commun Signal. 2008;2:49–56. doi: 10.1007/s12079-008-0029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A, Parapuram SK, Shiwen X, Abraham DJ. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, CCN2) gene expression: a potent clinical marker of fibroproliferative disease. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:89–94. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0037-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivonen SK, Häkkinen L, Liu D, Kähäri VM. Smad3 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 coordinately mediate transforming growth factor-beta-induced expression of connective tissue growth factor in human fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1162–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire R, Farina G, Bayle J, Dimarzio M, Pendergrass SA, Milano A, Perbal B, Whitfield ML, Lafyatis R (2011) Antagonistic effect of the matricellular signaling protein CCN3 on TGF-beta- and Wnt-mediated fibrillinogenesis in systemic sclerosis and Marfan syndrome. J Invest Dermatol 130:1514–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Thompson K, Leask A. CCN2 expression by fibroblasts is not required for cutaneous tissue repair. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:119–124. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, Kawara S, Shinozaki M, Hayashi N, Kakinuma T, Igarashi A, Takigawa M, Nakanishi T, Takehara K. Role and interaction of connective tissue growth factor with transforming growth factor-beta in persistent fibrosis: a mouse fibrosis model. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:153–159. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199910)181:1<153::AID-JCP16>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pala D, Kapoor M, Woods A, Kennedy L, Liu S, Chen S, Bursell L, Lyons K, Carter D, Beier F, Leask A. FAK/src suppresses early chondrogenesis: central role of CCN2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9239–9247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705175200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis V, Dargere D, Vidaud M, De Gouville AC, Huet S, Martinez V, Gauthier JM, Ba N, Sobesky R, Ratziu V, Bedossa P. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in experimental rat and human liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 1999;30:968–976. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. CCN proteins: a centralized communication network. J Cell Commun Signal. 2013;7(3):169–177. doi: 10.1007/s12079-013-0193-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riser BL, Najmabadi F, Perbal B, Peterson DR, Rambow JA, Riser ML, Sukowski E, Yeger H, Riser SC. CCN3 (NOV) is a negative regulator of CCN2 (CTGF) and a novel endogenous inhibitor of the fibrotic pathway in an in vitro model of renal disease. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:1725–1734. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riser BL, Bhagavathula N, Perone P, Garchow K, Xu Y, Fisher GJ, Najmabadi F, Attili D, Varani J. Gadolinium-induced fibrosis is counter-regulated by CCN3 in human dermal fibroblasts: a model for potential treatment of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. J Cell Commun Signal. 2012;6:97–105. doi: 10.1007/s12079-012-0164-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi-wen X, Stanton LA, Kennedy L, Pala D, Chen Y, Howat SL, Renzoni EA, Carter DE, Bou-Gharios G, Stratton RJ, Pearson JD, Beier F, Lyons KM, Black CM, Abraham DJ, Leask A. CCN2 is necessary for adhesive responses to transforming growth factor-beta1 in embryonic fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:10715–10726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K, Hamilton DW, Leask A (2011) ALK5 inhibition blocks TGFß-induced CCN2 expression in gingival fibroblasts. J Dent Res 89:1450–1454 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tran CM, Smith HE, Symes A, Rittié L, Perbal B, Shapiro IM, Risbud MV. Transforming growth factor β controls CCN3 expression in nucleus pulposus cells of the intervertebral disc. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:3022–3031. doi: 10.1002/art.30468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Beek JP, Kennedy L, Rockel JS, Bernier SM, Leask A. The induction of CCN2 by TGFbeta1 involves Ets-1. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R36. doi: 10.1186/ar1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Usinger W, Nichols B, Gray J, Xu L, Seeley TW, Brenner M, Guo G, Zhang W, Oliver N, Lin A, Yeowell D. Cooperative interaction of CTGF and TGF-β in animal models of fibrotic disease. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2011;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao YQ, Liu K, Shen JF, Xu GT, Ye W. SB-431542 inhibition of scar formation after filtration surgery and its potential mechanism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1698–1706. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]