Abstract

Gastric gland mucin is secreted from gland mucous cells, including pyloric gland cells and mucous neck cells located in the lower layer of the gastric mucosa. These mucins typically contain O-glycans carrying terminal α1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine residues (αGlcNAc) attached to the scaffold protein MUC6, and biosynthesis of the O-glycans is catalyzed by the glycosyltransferase, α1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase (α4GnT). We previously used expression cloning to isolate cDNA encoding α4GnT, and then demonstrated that αGlcNAc functions as natural antibiotic against Helicobacter pylori, a microbe causing various gastric diseases including gastric cancer. More recently, it was shown that αGlcNAc serves as a tumor suppressor for differentiated-type adenocarcinoma. This review summarizes these findings and identifies dual roles for αGlcNAc in gastric cancer.

Keywords: expression cloning; glycosyltransferase, H. pylori; knockout mouse; mucin histochemistry

I. Introduction

Gastric mucins consist primarily of heavily glycosylated glycoproteins that protect the gastric mucosa from the external environment by forming a mucous gel layer [24]. These mucins are classified into two subtypes: surface mucin and gland mucin. The former is secreted from surface mucous cells lining the gastric mucosa and contains surface mucin-specific glycans such as Lewis-related blood group carbohydrates attached to the mucin core protein MUC5AC, while the latter is secreted from gland mucous cells, including pyloric gland cells and mucous neck cells, located in the lower layer of the gastric mucosa and contains gland mucin-specific glycans attached to MUC6 [22].

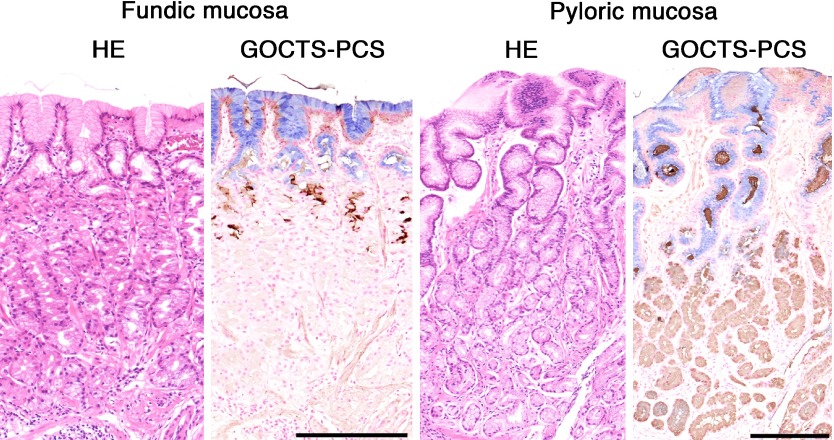

To detect these glycans histochemically, the galactose oxidase-cold thionin Schiff (GOCTS) reaction, originally developed as the galactose oxidase-Schiff reaction [10, 26], is used to stain surface mucin-specific glycans a blue color. On the other hand, gland mucin-specific glycans, also called class III mucins, are identified as a brown stain by paradoxical Concanavalin A staining (PCS), which consists of oxidation, reduction, reaction with Concanavalin A, and visualization by horseradish peroxidase [11, 20]. Dual staining using GOCTS followed by PCS can localize both types of glycans on a single tissue section (Fig. 1) [23].

Fig. 1.

Histochemical demonstration of the surface mucin- and gland mucin-specifc glycans in human stomach, as revealed by GOCTS-PCS staining. Glycans in the surface mucin are detected by the GOCTS reaction as a blue color, while glycans in gland mucin appear brown following PCS staining. HE, Hematoxylin & Eosin. Bars=200 µm.

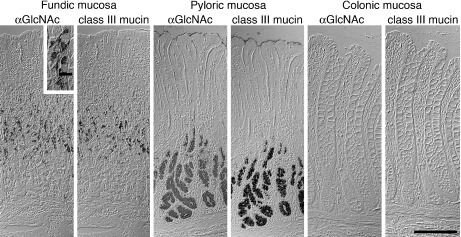

Ishihara et al. developed the monoclonal antibody HIK1083, which specifically reacts with O-glycans having terminal α1,4-linked N-acetylglucosamine residues (αGlcNAc) contained in the gland mucin [8]. By using that antibody it was also shown that αGlcNAc expression is limited to gland mucous cells and duodenal Brunner’s glands (Fig. 2) [8, 18]. Because the expression pattern of αGlcNAc was identical to that of class III mucin (Fig. 2), it was suggested that class III mucin could be αGlcNAc itself [21]. Although αGlcNAc glycan is unique to gastric gland mucin, its biological function has remained unknown.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of αGlcNAc and class III mucin in human gastrointestinal tract. Expression of αGlcNAc in the gastrointestinal tract mirrors that of class III mucin. αGlcNAc panels: immunohistochemistry with HIK1083 antibody. Class III mucin panels: paradoxical Concanavalin A staining. Bar=200 µm, and bar in inset indicates 20 µm. (from Nakayama et al. 1999; Copyright 1999 National Academy of Sciences, USA)

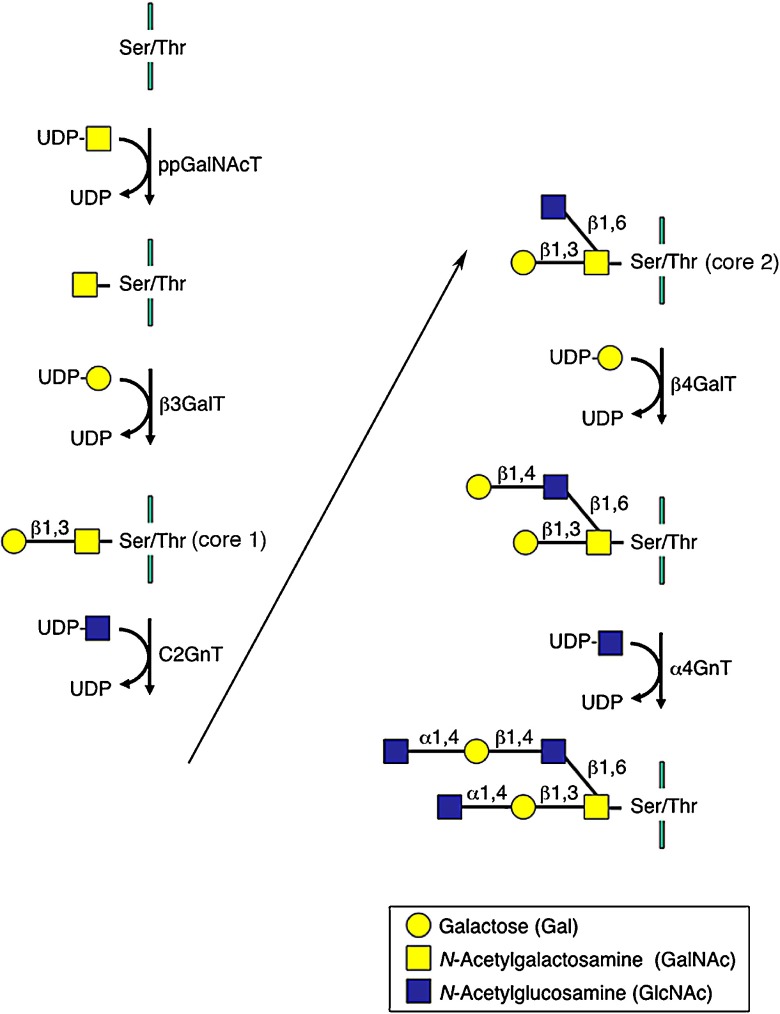

αGlcNAc biosynthesis is catalyzed by a concerted reaction of various glycosyltransferases acting on serine or threonine residues of scaffold proteins such as MUC6 (Fig. 3). In particular, α1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferese (α4GnT), which transfers GlcNAc from UDP-GlcNAc to terminal β-galactose (βGal) residues present in O-glycans with an α1,4-linkage, is critical to form αGlcNAc [19]. To understand αGlcNAc function in gastric mucosa, we isolated cDNA encoding α4GnT by expression cloning [21]. Using α4GnT cDNA as a molecular tool, we then showed that αGlcNAc is a class III mucin itself and has dual roles in antagonizing gastric cancer. In this review, I first describe the isolation and expression of α4GnT in gastric mucosa, and then report recent advances, emphasizing primarily our own data, in understanding how αGlcNAc protects against gastric adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 3.

αGlcNAc biosynthesis. αGlcNAc is synthesized by a concerted reaction of various glycosyltransferases. α4GnT, which transfers GlcNAc from UDP-GlcNAc to βGal residues attached to serine/threonine residues present in O-glycans with an α1,4-linkage, plays a key role to form αGlcNAc. UDP, uridine diphosphate. ppGalNAcT, polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase. β3GalT, β1,3-galactosyltransferase. C2GnT, core 2 β1,6-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. β4GalT, β1,4-galactosyltransferase. α4GnT, α1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase.

II. Molecular Cloning and Expression of α4GnT, the Enzyme Responsible for αGlcNAc Biosynthesis

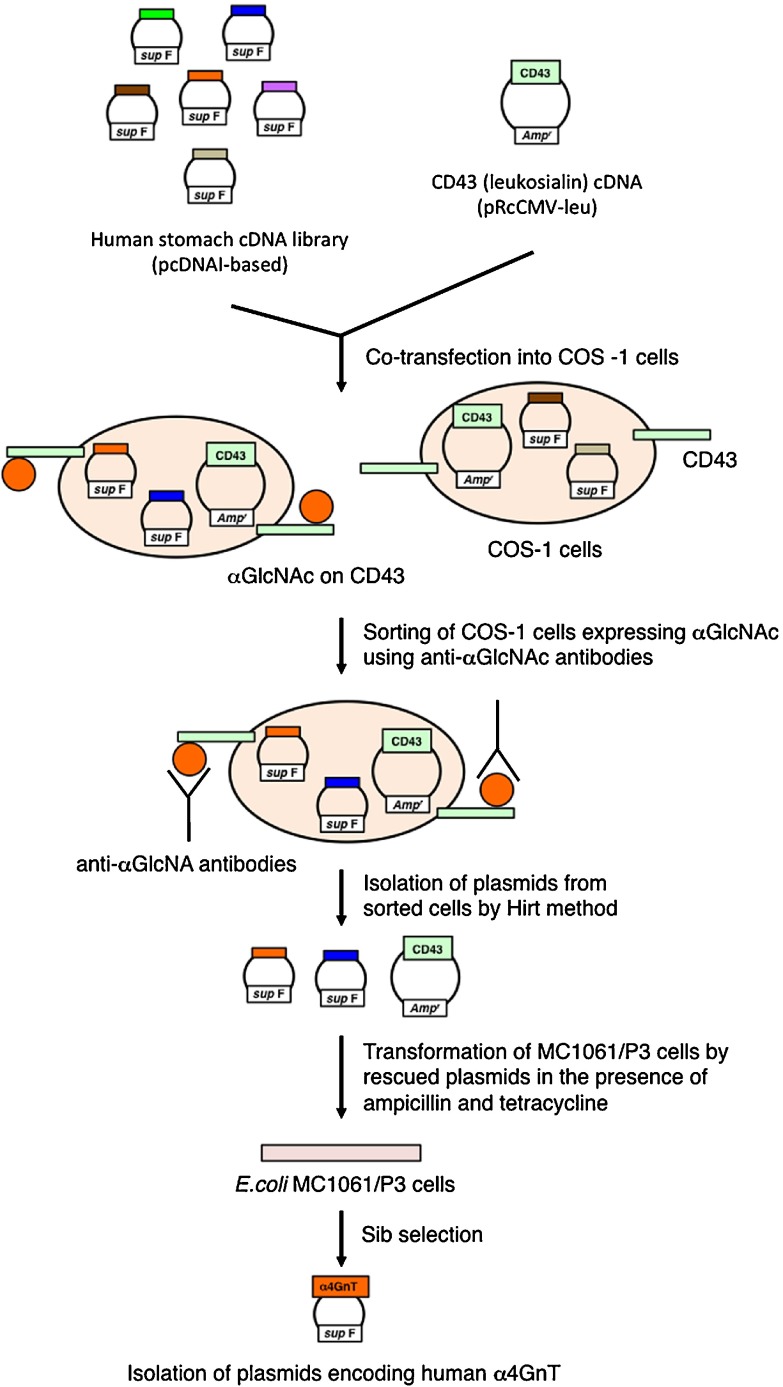

Because molecular cloning of cDNA encoding α4GnT was critical for understanding the biological role of αGlcNAc, we obtained human α4GnT cDNA using an expression cloning strategy (Fig. 4) [21]. Briefly, COS-1 cells, which are originally negative for αGlcNAc, were co-transfected with a human stomach cDNA library constructed in the mammalian expression vector pcDNAI together with a cDNA encoding the membrane-bound sialoglycoprotein of leukocytes leukosialin (CD43) which contains 80 O-glycans in its extracellular domain [3]. Transfected cells were then screened using monoclonal antibodies specific for αGlcNAc, including HIK1083 [8], PGM36, and PGM37 [14]. Transfected cells recognized by any of these antibodies were enriched by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Plasmid cDNAs were rescued from sorted cells and used to transform E. coli MC1061/P3 cells. As pcDNAI carries a sup F gene that corrects defects in both ampicillin- and tetracycline-resistance genes present in the P3 episome, transformed MC1061/P3 cells were resistant to both antibiotics, while MC1061/P3 cells transformed only by the leukosialin plasmid were resistant only to ampicillin. Thus, to identify plasmids derived from the cDNA library, cells were selected in the presence of ampicillin and tetracycline. Isolation of human α4GnT cDNA was achieved after several rounds of sib selection.

Fig. 4.

Expression cloning strategy used to obtain α4GnT cDNA. See text for detail.

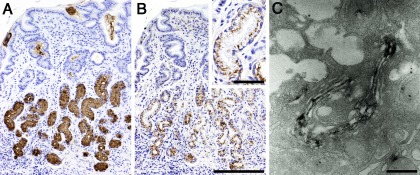

Our analysis indicated that α4GnT is a typical type II membrane protein of 340 amino acids and exhibiting a very short cytoplasmic N-terminal domain, a transmembrane domain and a large extracellular catalytic domain [21]. α4GnT showed significant homology to α1,4-galactosyltransferase (α4GalT, Gb3/CD77 synthase), with 35% overall sequence similarity at the amino acid level [13]. We then generated polyclonal antibodies against α4GnT, which we used to show that α4GnT is expressed in mucous cells that secrete αGlcNAc (Fig. 5) [27].

Fig. 5.

Expression of αGlcNAc and α4GnT in human gastric mucosa. (A) αGlcNAc is expressed in gland mucin secreted from the pyloric gland. (B) α4GnT is detected in the supranuclear region, which corresponds to the Golgi apparatus of the pyloric gland cells. (C) αGlcNAc is expressed in the medial Golgi of mucous neck cells of the fundic gland. A: Immunohistochemistry with HIK1083 antibody. B and C: Immunohistochemistry with anti-α4GnT antibody. Bars=200 µm (B) and 50 µm (B, inset), respectively. Bar=500 nm (C). (C is from Zhang et al. 2001; doi: 10.1177/002215540104900505 on SAGE Journals)

III. αGlcNAc Is Identical to Class III Mucin

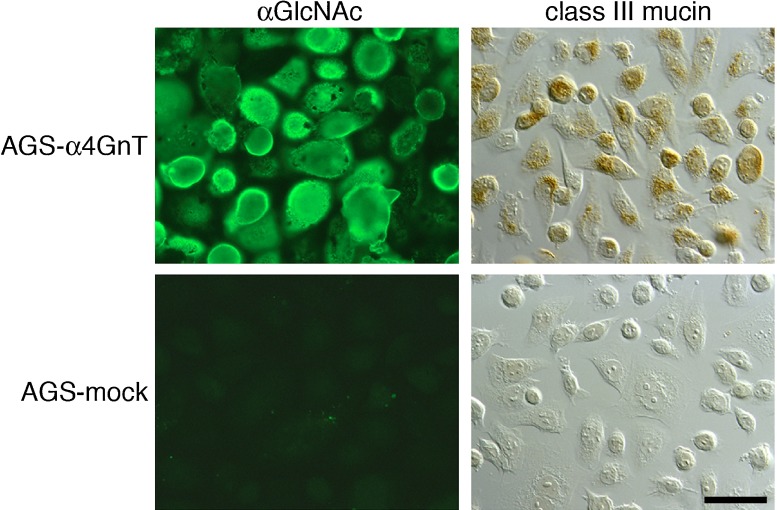

Since the expression pattern of class III mucin as identified by PCS is identical to that of αGlcNAc (Fig. 2), we investigated a potential association between αGlcNAc and class III mucin [21]. To this end, we generated a line of human gastric adenocarcinoma cells (AGS) stably expressing αGlcNAc (AGS-α4GnT) by transfecting AGS cells negative for both αGlcNAc and class III mucin with α4GnT cDNA. When we stained AGS-α4GnT cells with PCS, we detected class III mucin, demonstrating that αGlcNAc actually is class III mucin (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Expression of class III mucin on gastric adenocarcinoma AGS cells stably transfected with α4GnT cDNA. AGS-α4GnT cells express αGlcNAc and are positive for class III mucin. AGS-mock cells, transfected by vector alone, are negative for both αGlcNAc and class III mucin. αGlcNAc is detected by immunocytochemistry with HIK1083 antibody, and class III mucin is detected by paradoxical Concanavalin A staining. Bar=50 µm. (from Nakayama et al. 1999; Copyright 1999 National Academy of Sciences, USA)

IV. αGlcNAc Acts as a Natural Antibiotic against H. pylori Infection

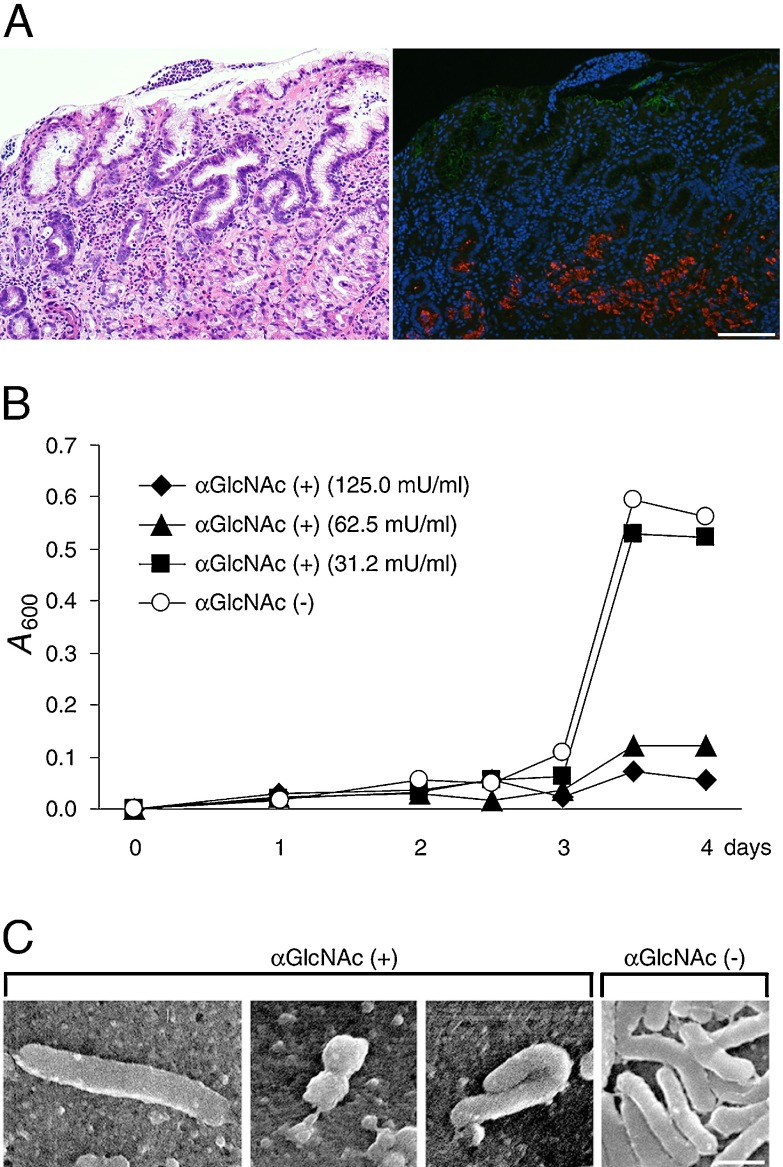

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) causes various gastric diseases, including chronic active gastritis, gastric adenocarcinoma, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT lymphoma) [25]. H. pylori largely colonizes the surface mucin and is rarely found in gland mucin (Fig. 7A) [5], suggesting that the presence of αGlcNAc protects against H. pylori infection. To test the hypothesis, we transfected Lec2 cells, a mutant CHO cell line defective in a sialic acid transporter and thus expressing core 1 O-glycans on the surface [2], with three expression vectors encoding C2GnT, α4GnT, and soluble CD43 (sCD43) to prepare recombinant sCD43 displaying αGlcNAc (Fig. 3) [12]. Lec2 cells are originally negative for core 2 branched structure and αGlcNAc. C2GnT forms a core 2 branched structure on core 1 structures [1]. β4GalT, expressed endogenously in Lec2 cells, attaches βGal to the core 2 branched structure, and α4GnT finally attaches GlcNAc to the terminal ends of core 2 and core 1 O-glycans with an α1,4-linkage. As controls, we transfected Lec2 cells with only two vectors, C2GnT and sCD43, allowing synthesis of O-glycans lacking αGlcNAc. After concentration of sCD43 released into culture medium of transfected Lec2 cells, we cultured H. pylori with varying amounts of sCD43 carrying αGlcNAc and found that H. pylori growth and motility were significantly suppressed in a dose-dependent manner and bacteria showed abnormal morphology, such as elongation and bending (Fig. 7B, 7C). By contrast, when we incubated bacteria with control sCD43 lacking αGlcNAc, we did not observe these effects, indicating that αGlcNAc antagonizes H. pylori growth [12].

Fig. 7.

Antimicrobial activity of αGlcNAc against H. pylori infection. (A) Chronic active gastritis of human gastric mucosa caused by H. pylori infection. The microbe is rarely found in the gland mucin expressing αGlcNAc. Left panel shows Hematoxylin & Eosin staining, and right panel shows immunofluorecent staining using anti-H. pylori antibody (as a green color) and HIK1083 antibody for αGlcNAc (as a red color). Bar=100 µm. (B) Growth curves of H. pylori cultured in the presence of sCD43 carrying αGlcNAc (αGlcNAc (+)) or sCD43 lacking αGlcNAc (αGlcNAc (–)). One milliunit of αGlcNAc (+) corresponds to 1 µg of GlcNAcα-pNP. A600: absorbance at 600 nm. (C) Scanning electron micrographs showing H. pylori incubated with 31.2 mU/ml of sCD43 carrying αGlcNAc (αGlcNAc (+)) or the same protein concentration of sCD43 lacking αGlcNAc (αGlcNAc (–)) for 3 days. Bar=1 µm. (Panels B and C from Kawakubo et al. 2004; Copyright 2004 American Association for the Advancement of Science)

Hirai et al. had previously demonstrated that the H. pylori cell wall contains a unique glycolipid, cholesteryl-α-d-glucopyranoside (CGL) [6]. To determine how αGlcNAc antagonized H. pylori growth, we cloned cholesterol α-glucosyltransferase (αCgT) from H. pylori [15] and then demonstrated that αGlcNAc suppressed its ability to form CGL in vitro [16]. We also showed that an active form of αCgT is present in the membrane fraction of bacteria, suggesting that bacterial αCgT is likely accessible to αGlcNAc in gland mucin [7].

H. pylori requires exogenous cholesterol for CGL biosynthesis. Thus, we cultured H. pylori in the absence of cholesterol and found that resultant H. pylori lacking CGL exhibited reduced growth and motility, and died completely upon prolonged incubation up to 21 days, indicating that CGL is indispensable for H. pylori survival [12]. Taken together, these studies show that αGlcNAc inhibits CGL biosynthesis by H. pylori by suppressing αCgT, thus protecting the gastric mucosa from infection. Notably, a single nucleotide polymorphism of the A4GNT gene associated withhigher risk for H. pylori infection was reported by Zheng et al. [28].

V. αGlcNAc Serves as a Tumor Suppressor for Differentiated-type Adenocarcinoma of the Stomach

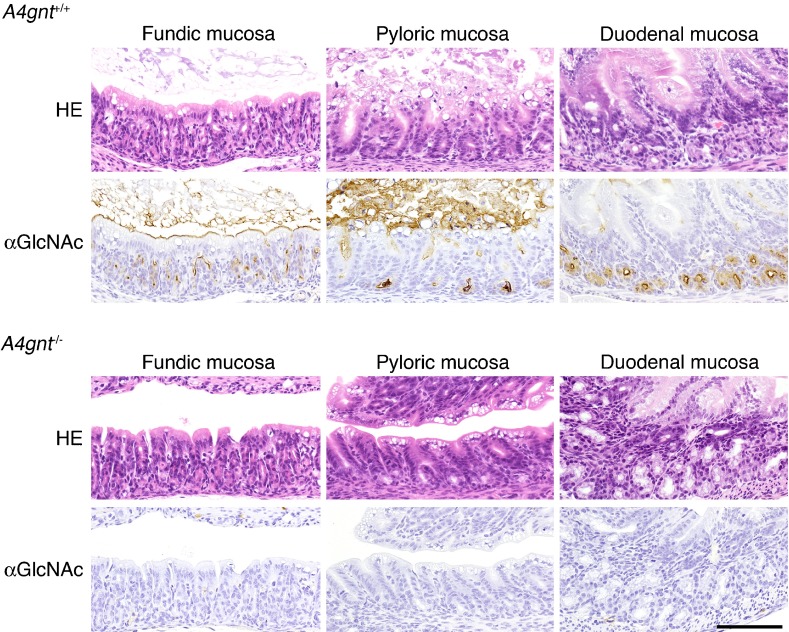

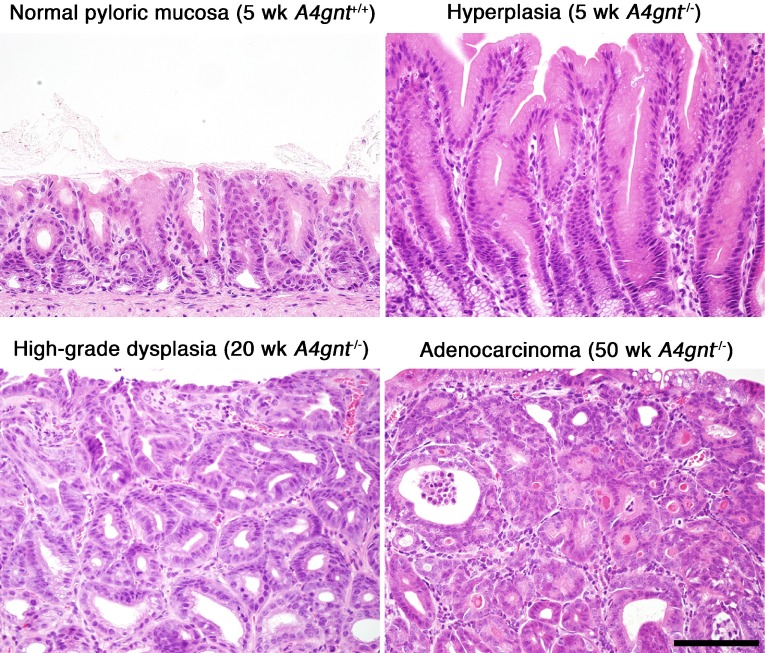

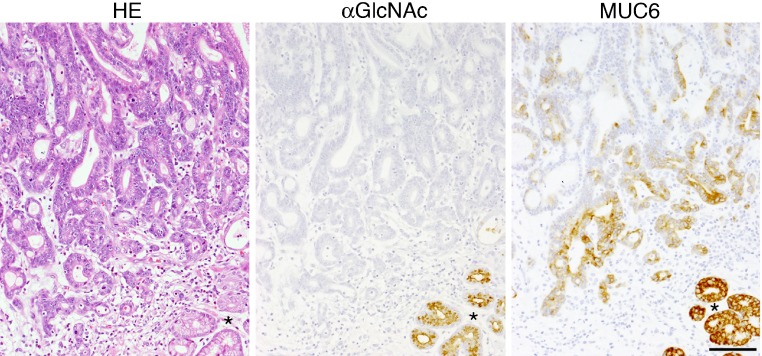

We next asked whether αGlcNAc had additional protective activities. To do so, we generated mice deficient in α4GnT by disrupting the A4gnt gene [9]. Immunohistochemistry using the αGlcNAc-specific antibody HIK1083 revealed that A4gnt-deficient mice showed a complete lack of αGlcNAc expression in gastric gland mucin and duodenal Brunner’s gland (Fig. 8). In addition, MALDI-TOF-MS analysis demonstrated that unlike wild-type mice, the gastric mucin of A4gnt-deficient mice showed a complete absence of O-glycans carrying αGlcNAc in oligosaccharides. These results formally establish that α4GnT is the sole enzyme catalyzing addition of αGlcNAc to O-glycans in vivo [9]. Histopathology analysis of gastric tissues from A4gnt-deficient mice revealed that they spontaneously exhibited hyperplasia by 5 weeks of age, low-grade dysplasia by 10 weeks, and high-grade dysplasia by 20 weeks. In 30-week-old mice, differentiated-type adenocarcinoma developed in 2 of 6 A4gnt-deficient mice, and the incidence of adenocarcinoma increased by 50 weeks of age. All 50-week-old mice exhibited differentiated type adenocarcinoma, with cancer cells located primarily in the gastric mucosa, and up to 60 weeks of age mice showed no sign of distant metastasis (Fig. 9). These pathologies were consistently restricted to the antrum of the glandular stomach, indicating that the mucous neck cells in the fundic mucosa were not involved in the gastric tumorigenesis in this model. Interestingly, mutant mice did not show gastric undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma, such as signet ring cell carcinoma, clearly demonstrating that A4gnt-deficient mice develop gastric differentiated-type adenocarcinoma through a hyperplasia-dysplasia-carcinoma sequence, even in the absence of H. pylori infection. No significant abnormalities were found in organs other than the glandular stomach. These results indicate that αGlcNAc serves as a tumor suppressor for gastric adenocarcinoma. In fact, significant reduced levels of αGlcNAc relative to MUC6 are seen in human early gastric differentiated-type adeno-carcinoma, and 40% of 48 MUC6-positive gastric cancer patients were completely negative for αGlcNAc (Fig. 10) [9]. Significant reduction of αGlcNAc was also seen in a potentially premalignant lesion gastric tubular adenoma.

Fig. 8.

Loss of αGlcNAc in A4gnt-deficient mice. αGlcNAc is completely absent in gland mucous cells of the gastric mucosa and in Brunner’s glands of the duodenal mucosa of A4gnt-deficient mouse (A4gnt–/–). Shown is immunohistochemistry of one-week-old mice with αGlcNAc-specific HIK1083 antibody. Bar=100 µm.

Fig. 9.

Gastric pathology of A4gnt-deficient mice. Representative histopathology analysis showing hyperplasia at 5 weeks (upper right), high-grade dysplasia at 20 weeks (lower left), and differentiated type adenocarcinoma at 50 weeks (lower right) in the pyloric mucosa of A4gnt-deficient mice. For comparison (upper left), pyloric mucosa from a 5-week-old wild-type mouse is shown. Bar=100 µm.

Fig. 10.

Human early gastric differentiated-type adenocarcinoma. No expression of αGlcNAc is seen in MUC6-positive adenocarcinoma cells. Normal pyloric glands (*) adjacent to the carcinoma cells are positive for both αGlcNAc and MUC6. HE, Hematoxylin & Eosin. αGlcNAc and MUC6 are detected by immunocytochemistry with HIK1083 and anti-MUC6 (clone CLH5) antibodies, respectively. Bar=100 µm.

To define pathways linking αGlcNAc to tumor suppression, we carried out microarray and quantitative RT-PCR analyses of gastric mucosa from A4gnt–deficient and wild-type mice. Genes encoding inflammatory chemokine ligands such as Ccl2, Cxcl1, and Cxcl5, proinflammatory cytokines such as Il-11 and Il-1β, and growth factors such as Hgf and Fgf7 were upregulated in the gastric mucosa of mutant mice. Ccl2 upregulation is of particular interest, as it attracts tumor-associated macrophages, which exert pro-tumorigenic immune responses and promote tumor angiogenesis [4, 17]. In fact, both infiltration of inflammatory cells such as mononuclear cells and neutrophils and angiogenesis increased progressively in the gastric mucosa of A4gnt–deficient mice as they aged. These results demonstrate that αGlcNAc loss triggers gastric carcinogenesis through inflammation-associated pathways in vivo.

VI. Conclusion

In this review, I conclude that gastric gland mucin-specific αGlcNAc is identical to class III mucin detected by PCS and plays a dual role: it acts as a natural antibiotic to prevent gastric cancer by inhibiting H. pylori infection and it also functions as a tumor suppressor for differentiated-type gastric adenocarcinoma. These studies should encourage future development of new strategies to detect, diagnose, treat, and prevent gastric cancer.

VII. Acknowledgments

Part of this review article was presented at the 54th Annual meeting of the Japan Society of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry in Tokyo on September 27–28, 2013, as the Takamatsu Prize Lecture. I am grateful to all collaborators for their contributions to this research. I also wish to thank Dr. Tsutomu Katsuyama, Emeritus Professor of Shinshu University, Dr. Minoru Fukuda, Professor at the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute, and Dr. Michiko N. Fukuda, Professor at the Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute, for their encouragement and collaboration, and Dr. Elise Lamar for editing this manuscript.

VIII. References

- 1.Bierhuizen M. F., Fukuda M. Expression cloning of a cDNA encoding UDP-GlcNAc:Gal β1-3-GalNAc-R (GlcNAc to GalNAc) β1-6GlcNAc transferase by gene transfer into CHO cells expressing polyoma large tumor antigen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A . 1992;89:9326–9330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deutscher S. L., Nuwayhid N., Stanley P., Briles E. I., Hirschberg C. B. Translocation across Golgi vesicle membranes: a CHO glycosylation mutant deficient in CMP-sialic acid transport. Cell. 1984;39:295–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuda M. In “Cell Surface Carbohydrates and Cell Development”, ed. by M. Fukuda. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 1992. Cell surface carbohydrates in hematopoietic cell differentiation and malignancy; pp. 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grivennikov S. I., Greten F. R., Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hidaka E., Ota H., Hidaka H., Hayama M., Matsuzawa K., Akamatsu T., Nakayama J., Katsuyama T. Helicobacter pylori and two ultrastructurally distinct layers of gastric mucous cell mucins in the surface mucous gel layer. Gut. 2001;49:474–480. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.4.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirai Y., Haque M., Yoshida T., Yokota K., Yasuda T., Oguma K. Unique cholesteryl glucosides in Helicobacter pylori: composition and structural analysis. J. Bacteriol. 1995;177:5327–5333. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.18.5327-5333.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoshino H., Tsuchida A., Kametani K., Mori M., Nishizawa T., Suzuki T., Nakamura H., Lee H., Ito Y., Kobayashi M., Masumoto J., Fujita M., Fukuda M., Nakayama J. Membrane-associated activation of cholesterol α-glucosyltransferase, an enzyme responsible for biosynthesis of cholesteryl-α-D-glucopyranoside in Helicobacter pylori critical for its survival. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2011;59:98–105. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2010.957092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishihara K., Kurihara M., Goso Y., Urata T., Ota H., Katsuyama T., Hotta K. Peripheral α-linked N-acetylglucosamine on the carbohydrate moiety of mucin derived from mammalian gastric gland mucous cells: epitope recognized by a newly characterized monoclonal antibody. Biochem. J. 1996;318 (Pt 2):409–416. doi: 10.1042/bj3180409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karasawa F., Shiota A., Goso Y., Kobayashi M., Sato Y., Masumoto J., Fujiwara M., Yokosawa S., Muraki T., Miyagawa S., Ueda M., Fukuda M. N., Fukuda M., Ishihara K., Nakayama J. Essential role of gastric gland mucin in preventing gastric cancer in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:923–934. doi: 10.1172/JCI59087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katsuyama T., Ono K., Nakayama J., Kanai M. In “Gastric Mucus and Mucus Secreting Cells”, ed. by K. Kawai. Excepta Medica; Amsterdam: 1985. Recent advances in mucosubstance histochemistry; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsuyama T., Spicer S. S. Histochemical differentiation of complex carbohydrates with variants of the concanavalin A-horseradish peroxidase method. J. Histochem. Cytochem. . 1978;26:233–250. doi: 10.1177/26.4.351046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawakubo M., Ito Y., Okimura Y., Kobayashi M., Sakura K., Kasama S., Fukuda M. N., Fukuda M., Katsuyama T., Nakayama J. Natural antibiotic function of a human gastric mucin against Helicobacter pylori infection. Science. 2004;305:1003–1006. doi: 10.1126/science.1099250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kojima Y., Fukumoto S., Furukawa K., Okajima T., Wiels J., Yokoyama K., Suzuki Y., Urano T., Ohta M., Furukawa K. Molecular cloning of globotriaosylceramide/CD77 synthase, a glycosyltransferase that initiates the synthesis of globo series glycosphingolipids. J. Biol. Chem. . 2000;275:15152–15156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909620199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurihara M., Ishihara K., Ota H., Katsuyama T., Nakano T., Naito M., Hotta K. Comparison of four monoclonal antibodies reacting with gastric gland mucous cell-derived mucins of rat and frog. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol Biol. 1998;121:315–321. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(98)10113-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H., Kobayashi M., Wang P., Nakayama J., Seeberger P. H., Fukuda M. Expression cloning of cholesterol α-glucosyltransferase, a unique enzyme that can be inhibited by natural antibiotic gastric mucin O-glycans, from Helicobacter pylori. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006;349:1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H., Wang P., Hoshino H., Ito Y., Kobayashi M., Nakayama J., Seeberger P. H., Fukuda M. α1,4GlcNAc-capped mucin-type O-glycan inhibits cholesterol α-glucosyltransferase from Helicobacter pylori and suppresses H. pylori growth. Glycobiology. 2008;18:549–558. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantovani A., Savino B., Locati M., Zammataro L., Allavena P., Bonecchi R. The chemokine system in cancer biology and therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. . 2010;21:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura N., Ota H., Katsuyama T., Akamatsu T., Ishihara K., Kurihara M., Hotta K. Histochemical reactivity of normal, metaplastic, and neoplastic tissues to α-linked N-acetylglucosamine residue-specific monoclonal antibody HIK1083. J. Histochem. Cytochem. . 1998;46:793–801. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakayama J. In “Handbook of Glycosyltransferases and Related Genes”, ed. by N. Taniguchi, K. Honke, and M. Fukuda. Springer-Verlag; Tokyo: 2002. α4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase; pp. 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakayama J., Katsuyama T., Fukuda M. Recent progress in paradoxical Concanavalin A staining. Acta Histochem. Cytochem. 2000;33:153–157. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama J., Yeh J.-C., Misra A. K., Ito S., Katsuyama T., Fukuda M. Expression cloning of a human α1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase that forms GlcNAcα14GalβR, a glycan specifically expressed in the gastric gland mucous cell-type mucin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1999;96:8991–8996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.8991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nordman H., Davies J. R., Lindell G., de Bolós C., Real F., Carlstedt I. Gastric MUC5AC and MUC6 are large oligomeric mucins that differ in size, glycosylation and tissue distribution. Biochem. J. . 2002;364:191–200. doi: 10.1042/bj3640191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ota H., Katsuyama T., Ishii K., Nakayama J., Shiozawa T., Tsukahara Y. A dual staining method for identifying mucins of different gastric epithelial mucous cells. Histochem. J. 1991;23:22–28. doi: 10.1007/BF01886504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ota H., Katsuyama T. Alternating laminated array of two types of mucin in the human gastric surface mucous layer. Histochem. J. 1992;24:86–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01082444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peek R. M. Jr., Blaser M. J. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulte B. A., Spicer S. S. Light microscopic histochemical detection of terminal galactose and N-acetylgalactosamine residues in rodent complex carbohydrates using a galactose oxidase-Schiff sequence and peanut lectin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1983;31:19–24. doi: 10.1177/31.1.6187799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang M. X., Nakayama J., Hidaka E., Kubota S., Yan J., Ota H., Fukuda M. Immunohistochemical demonstration of α1,4-N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase that forms GlcNAcα1,4Galβ residues in human gastrointestinal mucosa. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2001;49:587–596. doi: 10.1177/002215540104900505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng Z., Jia Y., Hou L., Persson C., Yeager M., Lissowska J., Chanock S. J., Blaser M., Chow W., Ye W. Genetic variation in α4GnT in relation to Helicobacter pylori serology and gastric cancer risk. Helicobacter. 2009;14:472–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]