Abstract

Distinct molecular subtypes of breast carcinomas have been identified, but translation into clinical use has been limited. We have developed two platform independent algorithms to explore genomic architectural distortion using array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) data to measure 1) whole arm gains and losses (WAAI) and 2) complex rearrangements (CAAI). By applying CAAI and WAAI to data from 595 breast cancer patients we were able to separate the cases into eight subgroups with different distributions of genomic distortion. Within each subgroup data from expression analyses, sequencing and ploidy indicated that progression occurs along separate paths into more complex genotypes. Histological grade had prognostic impact only in the Luminal related groups while the complexity identified by CAAI had an overall independent prognostic power. This study emphasizes the relationship between structural genomic alterations, molecular subtype and clinical behavior, and show that objective score of genomic complexity (CAAI) is an independent prognostic marker in breast cancer.

Introduction

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease as reflected by histopathology, molecular alterations and clinical behavior. In order to relate cellular and sub-cellular features to clinical parameters and outcome, substantial effort has been exerted towards identifying tumor groups with distinct molecular features. Estrogen receptor (ER) status is a major discriminating factor of clinical importance (1). However recent gene expression based classifications have identified five different subgroups where two were luminal-cell related (Luminal A and Luminal B), one myoepithelial-cell related (Basal-like), one resembled normal breast tissue (Normal-like) and one were erbB2-enriched (2-4). The erbB2-enriched group has frequent activation of the erbB2/HER2 pathway, shows a high correlation to the Basal-like centroid and such tumors seem to be closely associated with the Basal-like phenotype (4). The erbB2-enriched and Basal-like subtypes are called “Basal-related tumors” in this paper. Basal-like and Luminal A carcinomas have different etiologies and for most purposes may be considered as distinct diseases (4-7). This is also reflected in the genomic portraits defined by aCGH, and it seems that the history of molecular subgroups is inscribed in the DNA alterations (8-10). Despite the power of RNA and DNA based profiling, translating complex molecular classifications into clinical practice has proven a formidable challenge. Clinical cohorts are often selected to have tumors of a certain category, and might not include all subtypes or outcome groups. The size of sample sets available for microarray studies has so far been limited, and combining sets to increase size has been challenging since various types of array platforms have been employed.

Array CGH does not reveal the chromosomal rearrangement patterns associated with copy number alterations; however much can be inferred from cytogenetic studies (11). The genomic architectural changes in breast tumors revealed by karyotyping follow some main traits. One such event seen early in tumor progression is the loss or gain of whole chromosome arms (12). Alternative events involve more complex rearrangements, where several different chromosomes concomitantly undergo inversions, deletions and amplifications (12).

Previously we found that invasive breast tumors had different patterns of aCGH aberrations and could be grouped in three different categories; simplex, complex I ‘sawtooth’ and complex II ‘firestorm’ (13). Tumors of the simplex type had few alterations with loss or gain of whole arms dominating, while tumors of the complex type had either many chromosomes altered with multiple regions with low level loss and gain (sawtooth pattern) or had a few selected regions with high copy number gains with intermittent losses (firestorms). We hypothesized that distinct molecular mechanisms underlie such patterns of aberrations. The simplex and the complex (sawtooth and firestorm) classification proposed by Hicks et al was not obtained algorithmically (13); hence no objective measure across platforms is available.

One aim of this study was to develop objective estimates of genome-wide architectural distortion. For each chromosome arm, two platform independent scores were defined: one measures whole-arm deviations from normal copy number (Whole Arm Aberration Index; WAAI) and the other the degree of local distortion (Complex Arm Aberration Index; CAAI). Our marker of genomic complexity (CAAI) was hypothesized to have independent prognostic power in breast cancer. Our aim was to investigate this marker in a large series of breast carcinomas (n=595) analyzed with aCGH and its relation to patient outcome. In addition a semi-supervised classifier was constructed based on acknowledged genomic alterations in Luminal A and Basal-like tumors by combining information from the WAAI and CAAI estimates. As three of the four tumor sets had extensive additional molecular data and clinical follow up available, this approach presciently revealed distinct patterns of genomic architectural distortion associated with outcome. Thus, varying levels of genomic distortion and survival outcomes may reflect different paths of tumor progression.

Results

Genomic architecture characterized by CAAI and WAAI

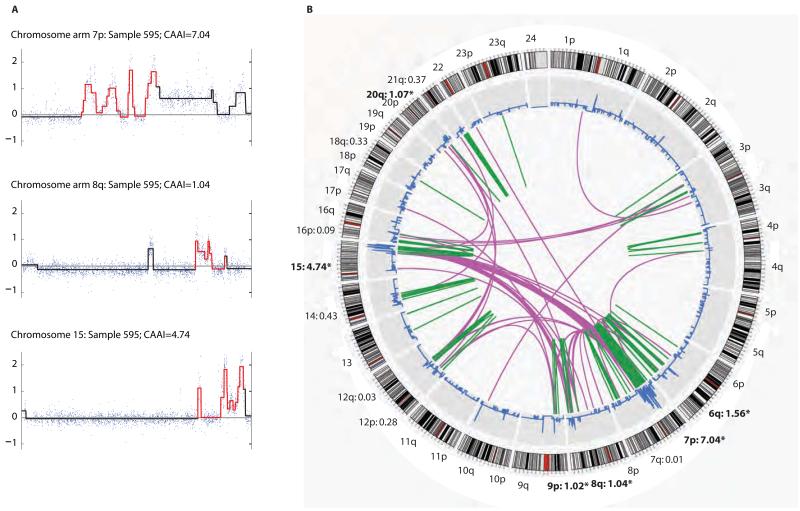

Two novel algorithms were constructed; one to identify complex architectural distortions characterized by physically tight clusters of break points with large changes of amplitude (CAAI), and another to recognize gains and loss of whole chromosome arms (WAAI). Segmented data from one tumor with corresponding CAAI values are illustrated for selected chromosome arms (Fig. 1A). The Circos plot from paired-end sequencing of the same sample (Fig. 1B) shows that CAAI recognizes regions with structural complexity (14). Areas of complex rearrangements were found by selecting chromosome arms with CAAI≥0.5. Comparison in one cohort of HER2 copy number gains estimated by FISH and the CAAI score showed that all but one sample with high CAAI had more than four copies of HER2 (fig. S1).

Figure 1. CAAI values compared to structural rearrangements identified by paired-end sequencing.

A) Raw (dots) and segmented (line) data for chromosome arms 7p and 8q and chr.15 from sample 595. Red segments correspond to the 20 Mb windows with highest CAAI; the corresponding CAAI was 7.04, 1.04 and 4.74 respectively. Chromosome arm 7p had an additional region with high level CAAI, but as this score was lower than 7.04 it was not highlighted in red.

B) Structural sequence alterations identified by genome wide paired-end sequencing for the same sample. Outer circle show the cytobands for each chromosome, followed by a plot indicating the copy number variation. The green bars in the centre refer to smaller intra-chromosomal changes such as duplications and inversions while pink lines indicate inter-chromosomal translocations. In this sample 13 chromosome arms had CAAI>0, six of these had CAAI≥0.5, these are in bold and marked with *. The two regions with most rearrangements showed the highest CAAI (chromosome arm 7p and chr.15). Areas with few rearrangements had low or zero CAAI.

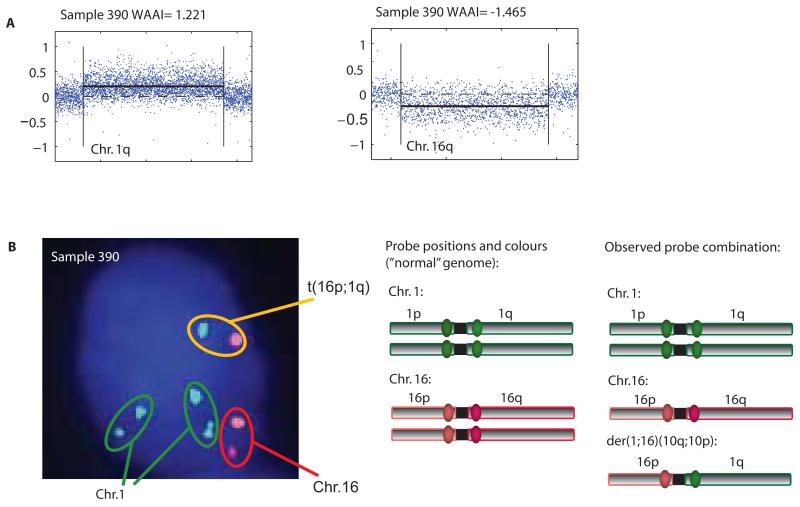

For most chromosome arms, the distribution of WAAI was approximately symmetric around zero (fig. S2). For some arms however, WAAI was skewed towards positive values (1q, 8q and 16p) and for others towards negative values (16q and 17p), reflecting a bias towards gain or loss. This pattern was seen in all cohorts, independent of platform (fig. S2). Arms with WAAI≥0.8 were defined as whole arm gains and arms with WAAI≤−0.8 as whole arm losses. Whole arm gain of 1q and whole arm loss of 16q by aCGH in an ER positive, diploid, invasive ductal carcinoma of histological grade 3 (Fig. 2A) were analyzed with FISH illustrating a combination of probes indicating a centromere-close translocation t(1q;16p) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. WAAI and centromere close translocation.

A) Plotted aCGH values for chromosome arm 1q and 16q from case WZ061; unsegmented data as blue points and PCF values as black line showed whole chromosome arm gain of 1q and loss of 16q. This was reflected in the estimated WAAI; WAAI= 1.221 for 1q and WAAI= −1.465 for 16q.

B) Multi gene FISH analyses with four selected probes derived from centromere close BAC clones on chr.1 and chr.16 were hybridized to tumor cells (imprint) from WZ061. The image to the left show a tumor cell with all fluorescent probes superimposed revealing two green signals together, one orange and red and one green and orange (note that the probes will never be fused due to the large stretches of heterochromatin around the centromere). The figure to the right illustrates the combination of fluorochromes observed in nuclei from lymphocytes with non-translocated chr.1 and chr.16 and an illustration of the observed combination in the tumor cells probably demonstrating a translocation and a derivative chromosome; der(1;16)(10q;10p).

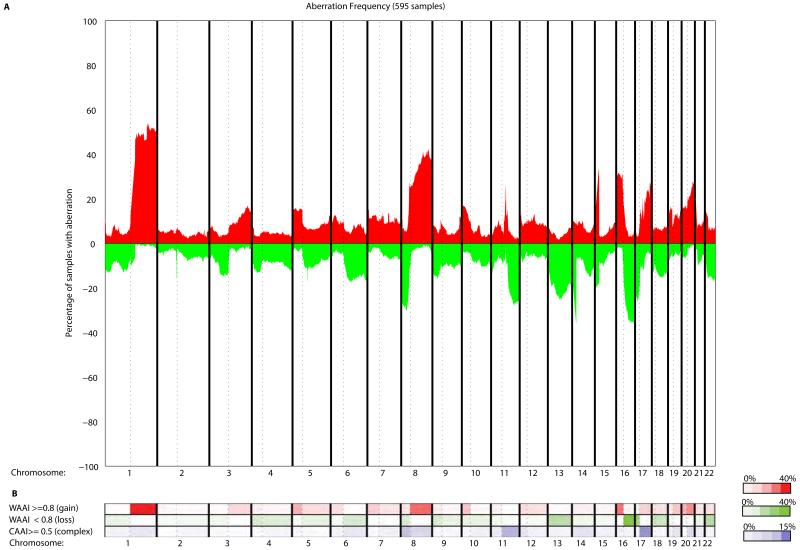

To determine the association between clinico-pathological information and frequency of chromosomal aberrations, four cohorts of breast cancer patients were analyzed using WAAI and CAAI (Fig. 3A, Table S1, Fig. S3). We utilized three previously published aCGH datasets; MicMa n=125 (13), WZ n=141 (15) and Chin-UCAM n=162 (16) (see materials and methods for details). In addition aCGH data for 167 patients of the Ull-cohort not previously published were analyzed. The four cohorts were merged for the analysis of association to clinico-pathological information, and the frequency plot in Fig. 3A shows an aberration pattern typical for breast cancer.

Figure 3. Genome wide distribution of genomic loss and gain compared to frequencies of WAAI and CAAI in 595 breast carcinomas.

A) Frequency plot illustrating the percentage of samples with gain and loss genome wide (red: gain, green: loss).

B) The frequency of samples scored with whole arm changes identified by WAAI and complex rearrangements scored by CAAI are shown in the heatmap. The color indicates the percentage arms with WAAI over and under the chosen threshold and the percentage of arms with CAAI higher than the threshold for each chromosome arm with: WAAI≥0.8 (red, top row), WAAI≤−0.8 (green, middle row) and CAAI≥0.5 (blue, bottom row). The plot illustrates the nonrandom distribution of different types of genomic events.

We found that the most frequent events such as gain of 1q and loss of 16q/17p are whole arm events, while the majority of gains on 17q and losses on 11q have CAAI≥0.5 and are likely caused by complex rearrangements (Fig. 3B). A few alterations such as gain on 8q and 20q displayed both whole arm gain and high CAAI (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that the type of alteration and on which chromosome arm it occurs is of importance in breast cancer.

Defining subgroups based on genomic architecture

Several studies have shown that the number of genomic alterations and the regions preferentially altered differ between the molecular expression subtypes (8,9,16,17). Luminal A/ER positive tumors often have few alterations with gain of 1q and loss of 16q dominating while Basal-like tumors frequently have many alterations affecting most of the chromosomes (8,9,16-18). Loss on 5q and gain on 10p have been proposed as specific Basal-like alterations (8,9,17,19), similar to findings in breast carcinomas from BRCA1 mutation carriers (20,21). Based on this, we distinguished between four groups of tumors: those with whole arm gain of 1q and/or loss of 16q (group A), those with regional loss on 5q and/or gain on 10p (group B), those with both (group AB), and those with neither (group C) (see materials and methods). The selection of these criteria was not influenced by knowledge of molecular or clinical parameters in the studied cohorts.

To further characterize these groups we split each into two “CAAI subgroups” depending on the level of complex rearrangement: those with CAAI < 0.5 for all arms (low level CAAI; A1, B1, AB1, C1) and those with CAAI≥0.5 for at least one arm (high level CAAI; A2, B2, AB2, C2). The group distribution was similar for all four cohorts, except for the WZ cohort that had more samples of type C and fewer samples with high level CAAI, most likely due to selection of diploid tumors (Table S2) (13). The WAAI-score was constructed to capture whole arm events and not localized gains and losses; this is to reflect underlying defects in DNA maintenance, such as isochromosomes and centromere close translocations. Localized gains on 1q and losses on 16q would not be classified as A-tumors according to our definition. This approach to classify tumors is an advance over previous stratification paradigms, as the criteria are not limited to specific genomic regions but also the architectural type of rearrangements such as gain or loss of whole chromosome arms (9,13,22).

Patterns of genomic architecture in the WAAI/CAAI groups

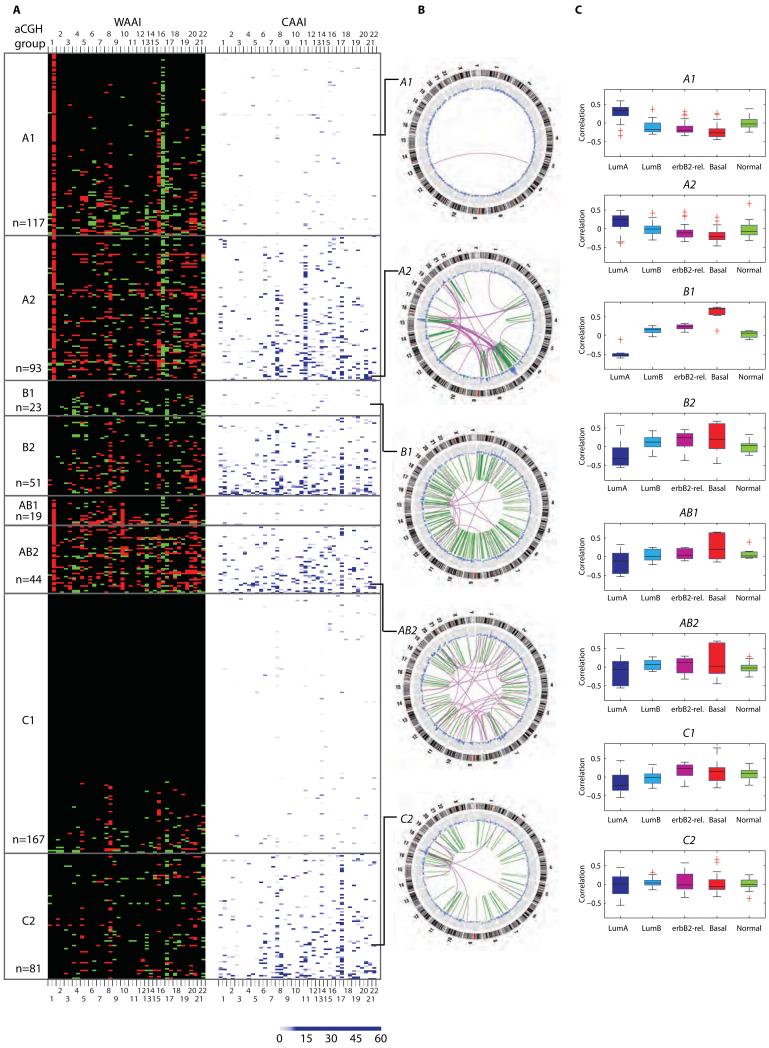

WAAI and CAAI characteristics

WAAI and CAAI revealed different chromosomal event and frequency distributions among the eight subgroups (Fig. 4A and 5). The subgroups displayed pronounced differences with respect to the number of whole chromosome arm loss or gain events (Fig. 4A and fig. S4). For each of the four WAAI groups, the tumors with complex rearrangements (i.e. A2, B2, AB2 and C2) had more whole arms affected, mostly by gains (WAAI≥0.8), than the corresponding group without complex rearrangements.

Figure 4. Genome wide distribution of WAAI and CAAI for all samples sorted into WAAI groups, examples of identified structural aberrations and corresponding gene expression patterns.

A) The heatmap illustrates the WAAI and CAAI score for all 595 samples sorted into A, B, AB and C tumors and thereafter into groups of tumors with and without high level CAAI on one chromosome arm or more. The sample sizes of the eight groups are indicated. Each row in the heatmap corresponds to one sample, and each column to a chromosome arm (from 1p to 22). The left panel indicate WAAI alterations for each chromosome arm (red: WAAI≥0.8, green; WAAI≤−0.8, black: 0.8>WAAI<−0.8). The right panel indicate the corresponding CAAI score for each chromosome arm for the same samples (no rearrangements=white. The CAAI scale is indicated below the figure).

B) Structural sequence alterations identified by genome wide paired-end sequencing for selected samples from the various WAAI/CAAI groups. The outer circle shows the cytobands for each chromosome, followed by the copy number variation. The green bars in the center indicate smaller intra chromosomal changes while pink lines indicate inter chromosomal translocations. The lines indicate the position of the selected samples in the aCGH/CAAI groups. C) Correlation to each of the five intrinsic subtypes for a total of 186 cases sorted into WAAI/CAAI groups.

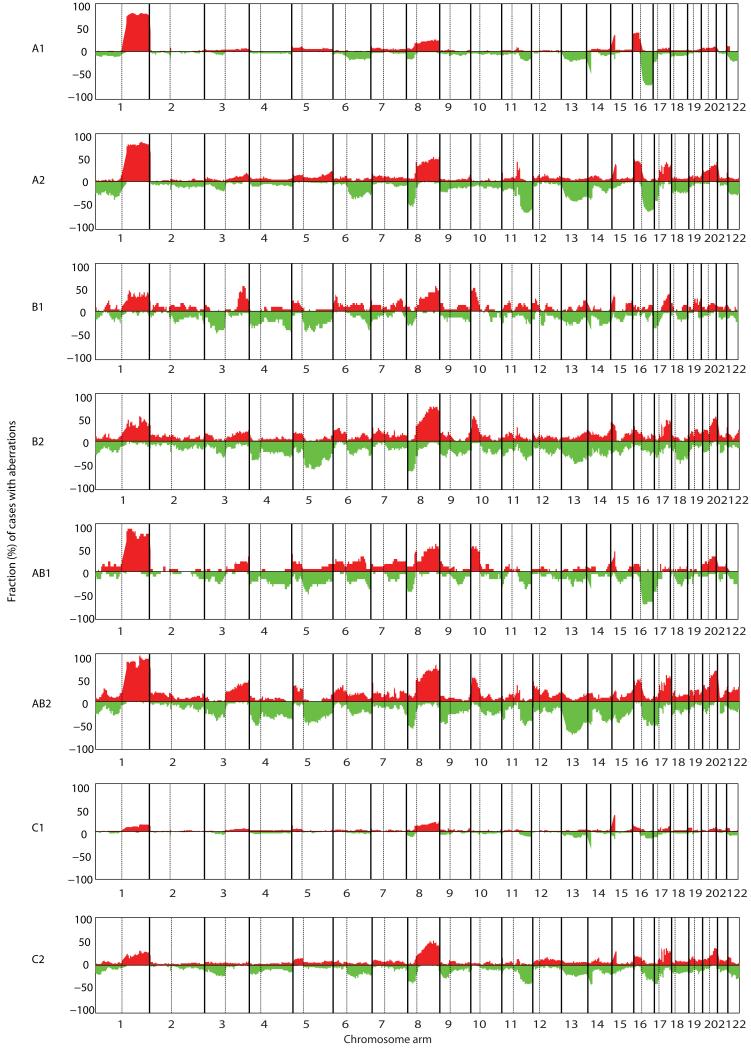

Figure 5. Frequencies of gain and loss of the eight WAAI/CAAI defined groups.

The figure shows frequency plots illustrating the percentage of samples with gains and losses within each WAAI/CAAI group (red; gain, green; loss). A1 tumors are dominated by gain on 1q and 16p and loss on 16q. These alterations are frequent in A2 tumors, in addition to gain on 8q, 17q and 20q and loss on 6q, 8p, 11q, 13 and 17p. B1, B2, AB1 and AB2 tumors have similarities in the patterns of gain and loss with almost all chromosomes affected, a pattern very dissimilar from aberrations in A1 and A2 tumors. C1 tumors have few alterations, with gain of 8q dominating. This is the most frequent aberration in C2 tumors as well, followed by gain on 1q, 17q and 20q.

Tumors of type A were frequently ER positive, of low or intermediate grade, diploid and included a majority of the invasive lobular carcinomas (Table S3). Group A was the only group with frequent alterations of whole chromosomes; particularly prominent were gain of 5, 7, 8 and 20 and loss of 18 (Fig. 4A), in line with previous cytogenetic findings (11,23). A1 and A2 tumors had the same distributions of altered arms, and the increased number of gains seen in A2 tumors were mainly affecting 8q, 16p, 20p and 20q (fig S5). In tumors of type A2, complex rearrangements were most frequent on 11q and 8p, followed by 17q and 8q (fig. S6). The high level amplifications on 8p and 11q include genes of interest such as FGFR1 and CCND1, loci known to be frequently amplified in ER positive breast carcinomas (24-26).

Tumors of type B were more frequently of high grade, aneuploid and TP53 mutated than tumors of type A (Table S3). Tumors of type B1 were dominated by whole arm losses, most frequently of 17p, 4p, 4q and 5q, while tumors of type B2 had complex alterations often affecting many arms, most frequently 17q, followed by 8p and 20q (Fig. 4A and fig. S4, S5, S6). The overall frequencies of aberrations were quite similar in B1 and B2 (Fig. 5).

AB tumors had elements of both A and B tumors, were dominated by aneuploid tumors of intermediate or high grade, and had the highest frequency of whole arm alterations (both gains and losses) (Table S3 and fig. S4, S5). The AB tumors with complex rearrangements had a heterogeneous distribution pattern of arms with high level of CAAI (Fig. 4A, fig. S6).

Group C tumors had the fewest number of whole arm alterations however the most frequent were observed gains of 8q and 16p and losses of 17p and chromosome 22 (Fig. 4A and fig. S4, S5). This was seen both in C1 and C2 carcinomas, with 17p being more frequently lost in C2 than in C1. For C2 tumors high level of CAAI was frequent on 17q but rare on 11q (Fig. 4A and fig. S6). The clinico-pathological parameters among group C tumors were similar with the A group, but had fewer ER positive and more TP53 mutated tumors (Table S3). Interestingly almost half of all tumors with histological grade 1 and most carcinomas of a special histological type such as lobular, tubulolobular and mucinous were grouped as C by our method.

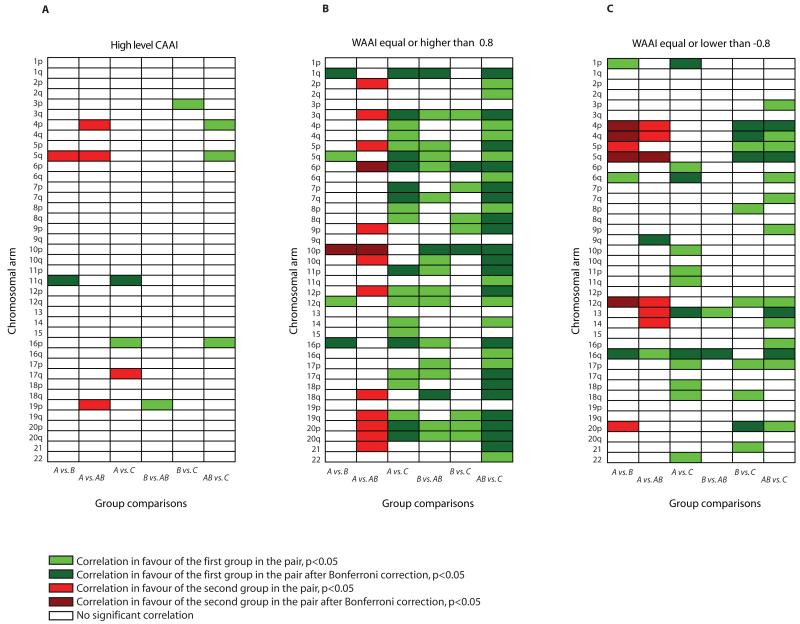

A pair wise comparison of the WAAI and CAAI for the four groups across all chromosome arms showed that alterations of several arms distinguished A tumors from both B, AB and C tumors (Fig. 6). High CAAI values on 11q were associated with A tumors in contrast to C and B tumors, and high CAAI values on 5q were characteristic of B and AB tumors and not A and C tumors. The high level of resemblance between CAAI distribution in B and AB was supported by WAAI alterations as well; no arms had significant differences in negative WAAI. This indicates that the whole chromosome arm losses characteristic of the B tumors are also present in AB tumors.

Figure 6. Pair wise comparison of WAAI and CAAI for the four groups across all chromosome arms.

A-C) A pair wise correlation of high level CAAI (A), WAAI≥0.8 (B) and WAAI≤−0.8 (C) between all eight WAAI/CAAI groups for all chromosome arms. Green color indicate a correlation in favor of the first group in the pair, red color indicate a correlation in favor of the second group in the pair. Bright color indicate arms where the correlation reach a significant level (p<0.05), the dark color indicate arms where the correlation reach a significant level after Bonferroni correction (p<0.05/39).

Paired-end sequencing

Paired-end sequencing was performed on a few selected samples representing distinct expression subgroups and where sufficient amount of DNA were available these analyses reveal genomic rearrangements down to the single base level and identify both inter- and intra-genomic fusions (14) (Fig. 4B). Analysis of the A1 tumor showed a single rearrangement, in contrast to the A2 tumor which exhibited a larger number of complex inter- and intra-chromosomal rearrangements, in line with the high level CAAI. The 1q/16q translocation in the A1 tumor was missed as the paired-end sequencing method does not detect alterations involving centromere-close heterochromatin (27). The B1 tumor showed numerous smaller structural rearrangements (“mutator phenotype”) in contrast to the pattern seen in the A1 and A2 tumors. The AB2 tumor showed a mutator phenotype pattern, but with more inter-chromosomal rearrangements than the B1 tumor. The C2 tumor had some segmental duplications/inversions in addition to complex rearrangements involving chromosome arm 17q.

Gene expression classification

For 186 tumors gene expression data were available (28,29). As no gold standard for assigning samples to subtypes across microarray platforms exists and it has been shown that normalization across datasets with different proportion ER positive samples affects subtyping (30); correlation to the subtype centroids were based on the original studies. Both A1 and A2 tumors showed strong correlation to the Luminal A subtype (Fig. 4C). Luminal B tumors were more frequent in the A2 group, indicating that A2 tumors represent more advanced tumors with high proliferation and increased growth factor signaling than A1 (31) (Table S4). This was also supported by ploidy data as the A2 group had a higher fraction of aneuploid and high grade tumors (fig. S7). The B1 tumors were dominated by the Basal-like subtype. The subtype correlation patterns of B2 and AB1/AB2 were quite similar, dominated by negative correlation to the Luminal A subtype, and overall had a closer resemblance to B1 than to A1/A2. A majority of erbB2-enriched and Normal-like tumors were classified as C tumors (29/45 and 19/34 respectively, Table S4). Normal-like tumors are rare and often omitted from breast cancer expression classification studies (32). It is acknowledged that samples depleted of tumor cells frequently correlate closely with the Normal-like centroid and the existence of a Normal-like subtype is disputed (32). However, Normal-like tumors can be aggressive and highly proliferative with stem cell properties, and even be cultivated like the cell line PMC42 (33), and Normal-like cell lines have shown enrichment in stem-cell related features (34). Almost 30% of all Basal-like tumors were classified as C tumors. This reflects both cases with other alterations than the selected 5q loss and/or 10p gain but in addition several cases had almost a “flat” aCGH profile. The latter is in line with previous studies that have identified a subgroup of Basal-like tumors having low genomic instability (16,35). Data on cellularity of the tumor samples do not suggest that these flat profiles are due to contamination of normal cells or lymphocytes (Table S5 and fig S8). Although some Basal-like tumors are shown to be polyclonal (36), it is unlikely that such tumors would result in flat profiles particularly with respect to amplifications.

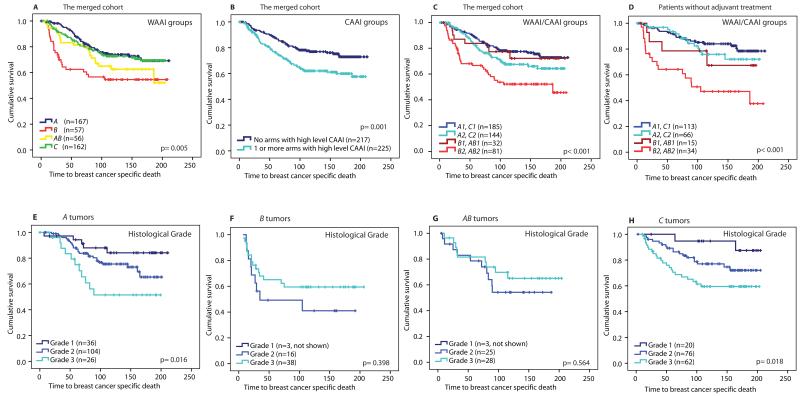

WAAI and CAAI groups as prognostic markers

Both the WZ cohort that was highly selected according to ploidy and outcome, and the ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) samples were omitted from survival and risk analyses to avoid bias, leaving 451 cases in the merged dataset. Kaplan-Meier plots illustrate significant difference in breast cancer specific death between the four WAAI groups and the two CAAI groups (p=0.005 and p=0.001 respectively, Fig. 7A and B). By adding CAAI to the WAAI groups, additional prognostic information is obtained as a separation of the B and AB groups into a group with better and a group with worse prognosis (p<0.001, Fig 7C and fig. S9). In a multivariate Cox regression analysis patients with the B type of tumor had a twofold increased risk of dying of breast cancer compared to those with the A type independent of lymph node status, tumor size, histological grade and treatment (HR: 2.14, CI (95%): 1.20-3.81, p=0.01, Table 1A). We also found an increased hazard rate (HR: 1.74, CI (95%): 1.18-2.55, p=0.005) for breast cancer specific death among patients with high level CAAI compared to those without; independent of treatment, lymph node status, tumor size, histological grade and WAAI class (Table 1B). Groups with similar outcome and biological features were collapsed to be able to do a multivariate analysis of the combined WAAI and CAAI groups and not lose power (Fig. 7C, fig. S8). In a multivariate Cox analysis patients with B2 or AB2 tumors had a 2.20 times higher risk (CI (95%): 1.35-3.59, p=0.002) and patients with A2 or C2 tumors had a 1.37 times higher risk (CI (95%): 0.87-2.17, p=0.17) of dying from breast cancer compared to patients with low level CAAI (Table 1C). In Fig. 7D survival curves for patients that did not receive any adjuvant therapy is displayed and shows the inferior outcome for B2/AB2 with a well separation from B1/AB1 (p<0.001), and the increased hazard risk for breast cancer related death for the B2/AB2 groups were also evident in this group of patients (Table S6). This finding in therapy naïve patients is important as it supports that the differences cannot be explained by therapy sensitivity, but seems related to the biology of the tumors. These analyses suggest that high level CAAI is an independent prognostic marker of breast cancer. A summary of the statistical analyses is presented in Table S7 according to the guidelines for reporting prognostic tumor markers (REMARK) (37).

Figure 7. CAAI and aCGH groups and breast cancer specific survival in the merged clinical dataset (n=451 cases).

A-D) The Kaplan Meier plots illustrate that breast cancer patients with tumors with B and AB tumors have the shortest survival (A), as do patients with high level CAAI (B). The differences between the groups by combination of WAAI groups and high level CAAI is shown in C. The Kaplan Meier curves show that B2 and AB2 have the worst survival, both in the merged cohort but also in patients that did not receive any adjuvant treatment (D). In C and D, groups with similar outcome and biology are collapsed. Kaplan Meier plots of survival estimates of all eight groups are shown in fig. S8.

E-H) the different impact of histological grade in the four WAAI groups is illustrated. Patients with an A or C tumor were stratified into long, intermediate and short time survival by histological grade (p=0.02 and p=0.03) in contrast to patients with B and AB tumors where we could not show any difference in breast cancer specific survival related to histological grade.

Table 1. Multivariate Cox regression analysis, the risk of breast cancer specific death measured by the defined parameters CAAI and WAAI.

| a) The four WAAI groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Cox regression | ||||

| Variables n=389 | p value | HR | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| WAAI groups | ||||

| B tumors (vs. A tumors) | 0.010 | 2.14 | 1.20 | 3.81 |

| AB tumors (vs. A tumors) | 0.283 | 1.38 | 0.78 | 2.48 |

| C tumors (vs. A tumors) | 0.586 | 1.14 | 0.72 | 1.81 |

| Lymph node status | ||||

| Positive (vs. negative) | <0.001 | 1.99 | 1.36 | 2.91 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| pT2 (vs. pT1) | 0.113 | 1.38 | 0.93 | 2.06 |

| pT3 and pT4 (vs. pT1) | 0.001 | 2.83 | 1.53 | 5.21 |

| Histological grade | ||||

| Grade 2 (vs. Grade 1) | 0.078 | 2.05 | 0.92 | 4.54 |

| Grade 3 (vs. Grade 1) | 0.017 | 2.71 | 1.19 | 6.15 |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||

| Tamoxifen alone (vs. no adj.) | 0.119 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 1.10 |

| Chemo. with/without Tam.(vs. no adj.) | 0.138 | 0.65 | 0.36 | 1.15 |

| b) Samples with high CAAI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Cox regression |

||||

| Variables n=389 | p value | HR | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| CAAI (high vs. low) | 0.005 | 1.74 | 1.18 | 2.55 |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||

| Tamoxifen alone (vs. no adj.) | 0.027 | 0.60 | 0.39 | 0.95 |

| Chemo. with/without Tam.(vs. no adj.) | 0.162 | 0.67 | 0.38 | 1.18 |

| Lymph node status | ||||

| Positive (vs. negative) | <0.001 | 2.29 | 1.49 | 3.51 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| pT2 (vs. pT1) | 0.067 | 1.45 | 0.97 | 2.16 |

| pT3 and pT4 (vs. pT1) | <0.001 | 3.02 | 1.63 | 5.58 |

| Histological grade | ||||

| Grade 2 (vs. Grade 1) | 0.082 | 2.04 | 0.91 | 4.56 |

| Grade 3 (vs. Grade 1) | 0.003 | 3.46 | 1.54 | 7.80 |

| WAAI groups | ||||

| B tumors (vs. A tumors) | 0.037 | 1.85 | 1.04 | 3.29 |

| AB tumors (vs. A tumors) | 0.551 | 1.20 | 0.66 | 2.20 |

| C tumors (vs. A tumors) | 0.677 | 1.10 | 0.69 | 1.76 |

| c) The combined WAAI and CAAI groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate Cox regression | ||||

| Variables n=389 | p value | HR | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||

| Lower | Upper | |||

| aCGH/CAAI grouped into four: | ||||

| A2, C2 (vs. Al, C1) | 0.172 | 1.37 | 0.87 | 2.17 |

| Bl, AB1 (vs. Al, Cl) | 0.901 | 1.05 | 0.47 | 2.36 |

| B2, AB2 (vs. Al, Cl) | 0.002 | 2.20 | 1.35 | 3.59 |

| Lymph node status (pos. vs. neg.) | 0.001 | 1.89 | 1.29 | 2.76 |

| Tumor size | ||||

| pT2 (vs. pT1) | 0.145 | 1.35 | 0.90 | 2.01 |

| pT3 and pT4 (vs. pT1) | 0.001 | 2.79 | 1.51 | 5.16 |

| Histological grade | ||||

| Grade 2 (vs. Grade 1) | 0.123 | 1.88 | 0.84 | 4.20 |

| Grade 3 (vs. Grade 1) | 0.013 | 2.81 | 1.24 | 6.36 |

| Adjuvant treatment | ||||

| Tamoxifen alone (vs. no adj.) | 0.040 | 0.62 | 0.40 | 0.98 |

| Chemo. with/without Tam.(vs. no adj.) | 0.129 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.14 |

As we regard several of the WAAI classes to represent distinct entities, we analyzed each of them separately with respect to commonly used prognostic markers, including histological grade, tumor size, lymph node status, estrogen receptor status, TP53 mutation status and expression based subtype. Analyzing A tumors (n=166) by univariate Cox regression analysis we found that histological grade, tumor size, lymph node status, TP53 mutation status and high level CAAI on more than two chromosomal arms were strong prognostic predictors (Table S8A). This is in contrast to B tumors (n=57) where only lymph node status and mutated TP53 indicated an increased hazard rate (borderline significant p-value, Table S8B). High level CAAI was a strong prognostic marker in AB tumors (n=55) with a HR of 5.06 (CI (95%): 1.38-18.59, p=0.015), but only if more than two arms were affected. In C-tumors histological grade, tumor size, lymph node status and TP53-status was of importance (n=160) (Table S8C and S8D). These results suggest that histological grade is prognostic only in A and C-tumors (Fig. 7E-G).

Discussion

Genome-wide, high resolution analyses of both DNA and RNA have brought novel insights into breast carcinoma classification (3,9,16), but conclusions have been limited by small sample sizes. By developing platform independent algorithms, we could merge aCGH data from several clinical cohorts and perform DNA based grouping of breast carcinomas, utilizing previous DNA and RNA classifications. This, combined with defined surrogate markers for Luminal and Basal-like breast cancer, revealed several distinct patterns of aberrant genomic architecture. Tumors of type A were dominated by ER positive, Luminal A tumors with large WAAI magnitude (both gains and losses), and by concomitant 1q gain and 16q loss probably caused by unbalanced centromere-close translocations between the two chromosomes (38). The same mechanism affecting other arms might explain the frequent losses and gains of whole chromosome arms in group A. Interestingly gain of 1q and/or loss of 16q are seen in different epithelial tumor types such as hepatocellular, ovarian, nasopharyngeal and prostate carcinomas (39). Gain of 16p is almost always seen together with the loss of 16q and the loss of 17p is common in a wide variety of tumors (39).

Several studies have indicated that Luminal tumors have a distinct progression path (40-43). This is reflected in our study by A2 tumors having more arms with high WAAI magnitude, being more frequently aneuploid, of high grade and with worse outcomes than A1 tumors (Fig. 4A). Amplification is found to precede the development of aneuploidy in breast cancer cell lines (44), and our study indicates that the same switch also occurs in vivo. Progression from A1 to A2 seems to induce a shift in gene expression pattern with a higher correlation to the Luminal B centroid and worse outcome (Fig. 4C and 7C).

The B tumors had a completely different and more heterogeneous genomic pattern. Group B1 tumors were dominated by losses. The single B1 case investigated by paired-end sequencing had in addition the typical mutator phenotype pattern reflecting multiple segmental duplications (14). In two separate studies we have found that a subgroup of Basal-like tumors are characterized by losses and progress from hypodiploid to aneuploid, often with complex rearrangements (36,45), in line with the B1 group being dominated by losses. Both AB and some C tumors had an expression pattern pointing towards a Basal-like relationship (Fig. 4C). In addition, AB2 and some C2 tumors had the greatest genomic distortion, were often aneuploid, had short survival, and we hypothesize that B2, AB2 and some C2 cases reflect more advanced tumors (Basal-like, erbB2-enriched and Normal-like).

We found that A and B tumors were different both at the genomic, transcriptomic and clinical level. It has been shown that amplifications on 8p/11q and 8q/17q occurs preferentially in two phenotypically diverse groups of breast cancer (46), consistent with the different CAAI distribution in A and B tumors. In a study using high resolution methylation arrays on one of the cohorts, we found patterns of methylation in A tumors resembling the CD24+/Luminal cell relationship and likewise a connection between B tumors and CD44+/progenitor cell methylation patterns (47). There are several indicators that molecular subgroups of breast cancer reflect transformation of different breast epithelial cell progenitors (48-50). Our study indicates that molecular subgroups can be recognized by differences in genomic architecture, possibly reflecting underlying subgroup-specific defects linked to different cells of origin. Basal-like carcinomas can be divided into several subtypes (51-53), and recent work indicates that a Luminal progenitor on a BRCA1 deficient background may be the cell of origin of such tumors (54). We hypothesize that the heterogeneity seen in groups B, AB and C with respect to the distribution of WAAI and CAAI, indicates that tumors of these types descend from different but related early progenitors, and that alternative combinations of repair defects defines several progression paths.

Complex rearrangements as defined by CAAI occurred in all subgroups, and CAAI had a strong prognostic impact independent of other factors, even if it only occurred on only one chromosomal arm. The mechanisms behind complex rearrangements are not completely understood, but one type can be explained by breakage-fusion-bridge cycles due to double strand repair defects resulting in high level amplicons with intermittent deletions (55,56). As high level amplicons are seen even in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (57) and in diploid tumors (13), this opens the possibility for a distinct subtype of carcinomas having complex alterations at an early stage of progression (“de novo complexity”).

The findings of this study are based on retrospective analyses of four previously collected datasets, and are thus limited by ethnicity, sample size and inclusion criterias. The acknowledged heterogeneity of breast cancer is evident among these 595 cases and the results illustrate the need to stratify patients by genomic alterations prior to risk. To be able to do this, several larger cohorts with long follow up are needed. Although we here present a tool to merge data from different type of platforms, the results will always be imitated by the platform with the lowest resolution. To fully validate the findings and to explore the subgroups further, larger cohorts with long time follow up analyzed on high resolution arrays will be advantageous.

The present study indicates that the type of genomic architectural distortion is of major importance in determining the tumor phenotype and can be used to group tumors into Luminal and Basal-related tumors. This is of major importance, since the value of established prognostic markers is subgroup dependent. We also find that even in biological distinct subtypes of breast cancer, the addition of complex rearrangements seem to be of major importance for patient outcome. A strong hierarchical relationship between subtypes of breast carcinomas is yet to be defined, but our findings provide a background for further functional studies aiming to elucidate the relationship between genomic architecture, phenotypic traits and the cell of origin in breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Patient samples and gene expression data

595 patients from four clinical cohorts were included in this study. The aCGH data from three of these cohorts have previously been published and are reanalyzed in this paper. For one cohort of 167 samples we present new aCGH-data. A summary of the cohorts with clinical and pathological data are found in Table S1 and detailed clinical information in Table S5. Previously published expression data was available for a subset of the samples; 112 Chin-UCAM, 113 MicMa and 73 Ull (16,28,29). The subtype assignment for each sample and the centroid correlation values were as published in the original papers.

1. The MicMa cohort.

Fresh frozen tumor biopsies were collected from 150 of the 920 patients included in the “Oslo Micrometastasis Project” from 1995-1998 (58). Expression data, TP53 mutation status and clinical data for these samples are described (29). 125 of these samples were available for aCGH analyses and were partly part of a previous publication (13).

2. The WZ cohort

A total of 141 frozen tumor specimens were selected from the archives of the Cancer Center of the Karolinska Institute, from 1987-1991. Clinical data and aCGH data are previously published (13). This cohort were retrospectively selected to represent a majority of diploid cases where half of the patients were long term survivors, the other half of the patients were dead of breast cancer.

3. The Chin-UCAM cohort

162 primary operable breast cancer specimens collected from 1990 to 1996 were obtained from the Nottingham Tenovus Primary Breast Cancer Series. Clinical data, expression and aCGH data are previously published (16).

4. The Ull cohort

Tumor specimens from 212 patients with primary breast cancer were sequentially collected at Oslo University Hospital Ullevål from 1990 to 1994. Primary breast carcinoma tissue was collected at primary surgery and fresh frozen at −80°C. DNA was isolated from and tumor tissue using chloroform/phenol extraction followed by ethanol precipitation (Nuclear Acid Extractor 340A; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA) according to standard procedures. Clinical data, TP53 mutation data and expression data for 80 of these samples are described by Langerød et al in 2007 (28). Sufficient DNA for aCGH analysis were available from 167 tumors, these data are not previously published.

Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization (aCGH) data

The raw and preprocessed data can be accessed from NCBI’s GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ ) with accession numbers GSE8757 (Chin-UCAM), GSE20394 (Ull), GSE19425 (MicMa and WZ).

DNA from the MicMa cohort were hybridized to the ROMA (Representational Oligonucleotide Microarray Analysis) 85k microarray, developed at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (59). The method is based on oligonucleotide probes designed after the restriction fragments from digestion with Bgl II. The platform is manufactured by NimbleGen, and the experiments followed the ROMA/NimbleGen protocol as previously described (13). Probe intensities were read with the GenePix Pro 4.0 software and used for ratio calculation. The data from both the MicMa and WZ cohort were normalized using an intensity-based lowess curve fitting algorithm.

DNA from the Ull samples was analyzed using 244k CGH microarrays (Hu-244A, Agilent technologies, Santa Clara, California, USA). This platform contains over 236.000 mapped in-situ synthesized oligonucleotide probes representing coding and non-coding sequences of the genome (60). The standard Agilent protocol was used, without pre-labeling amplification of input genomic DNA. Scanned microarray images were read and analyzed with Feature Extraction v9.5 (Agilent Technologies), using protocols (CGH-v4_95_Feb07 and CGH-v4 91 2) for aCGH-preprocessing which included linear normalization.

DNA from the Chin-UCAM cohort were as previously described (16) analyzed with a customized oligonucleotide microarray containing 30k 60-mer oligonucleotide probes representing 27800 mapped sequences of the human genome (61). Signal intensities and fluorescent ratios were obtained with BlueFuse version 3.2 (Bluegnome). Raw data were preprocessed using the software R (62) with the Bioconductor package limma (63).

FISH analysis

FISH analysis was performed using imprints from a selected tumor (i.e. interphase cells) with nick-translated probes prepared from BACs selected to be close to the centromere of chromosome 1 and 16. The hybridization was performed as previously published (13). Evaluation of signals was carried out in an epifluorescence microscope. Selected cells were photographed in a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope equipped with an Axio Cam MRM CCD camera and Axio Vision software at minimum 21 z-levels. The signals from lymphocytes served as controls. The combination of signals was evaluated, and was regarded as representative if they were observed in the majority of the cells.

Measurements of tumor ploidy

The ploidy of each tumor was determined by measurement of DNA content of non-tumoral and tumoral cells independently using Feulgen photocytometry (64,65). The optical densities of intact nuclei on an imprint were measured and a DNA index calculated and displayed as a histogram. Normal cells and diploid tumors display a major peak at ploidy 2n. Highly aneuploid tumors display broad peaks that often center on ploidy 4n, but may include cells from 2n to 6n or above. The histograms were visually interpreted to assign one number to the tumor ploidy. This was done in a non-arbitrary way by selecting the value for which the maximum is reached.

Pathology data and survival analyses

For each series an experienced pathologist reviewed Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) slides and immunohistochemical staining for ER and PgR from all tumors and reclassified them according to the WHO classification guidelines for breast cancer as previously published (13,16,28).

The endpoint for the survival analysis was breast cancer specific death measured from the date of surgery to death of the disease or otherwise censored at the time of the last follow-up visit or non-cancer-related death. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for time to breast cancer specific death was constructed and p-values calculated by the log rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was used for the univariate estimation of prognostic impact for the available clinical parameters including expression classes in the four WAAI groups. Three multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were performed by a backward conditional strategy including the WAAI groups, CAAI groups and the combined WAAI/CAAI groups respectively. Due to the number of events a selection of clinical variables for inclusion in the models was made including tumor size (pT), lymph node status, treatment and histological grade. The same analyses were also performed on non-adjuvant treated patients separately. All calculations were made using SPSS 16.0, and details about the analyses are in the REMARK document (Table S7).

Statistical methods and analytical tools

Segmentation into regions of constant copy number

For each sample a piecewise constant regression function were fitted to the log-transformed aCGH data, using the PCF algorithm (15,66). For each probe a fitted value (“PCF-value”) was thus obtained. The user controls the sensitivity of the method (via a “penalty parameter” gamma) and the least allowed number of probes in a segment (kmin). In our case, segmentation was performed on data from three different platforms with relative probe densities (average number of probes per unit distance) 0.12 (Chin-UCAM), 0.34 (MicMa/WZ) and 1.00 (244k Ull). As we aimed to pool all the segmented aCGH profiles, we scaled the parameters gamma and kmin to obtain roughly equal segmentation resolutions in the three platforms based on the theoretical resolution (thus essentially favoring variance reduction over bias reduction in the estimated copy number profiles for increasing probe densities) (15). Values for gamma and kmin were chosen to 100 and 20 for Ull, 34 and 7 for MicMa/WZ and 16 and 3 for Chin-UCAM. We acknowledge that the theoretical and the actual resolution may differ in different parts of the genome and that the theoretical functional resolution may be estimated as proposed by Coe et al (67). In our study ResCalc was not applied. Visual inspection of different segmentations with varying parameter choices indicated that this was a minor problem. The hypothesis of uniform distribution of aberrations is unlikely and some arrays, like Agilent 244k, are even constructed to be gene centered. Furthermore probes in repetitive regions of the genome will be sparsely spaced to maintain specificity. If such probes were removed, ResCalc would increase the functional resolution, however the coverage would be reduced (68).

Centering of copy number estimates

To center the segmented data, we found the density of the PCF-values using a kernel smoother with an Epanechnikov kernel and a window size of 0.03. The three tallest peaks P1, P2 and P3 in the density were considered in decreasing order of height (if there was less than three peaks, we replicated the highest one to obtain three peaks). For each, we found the location and relative height (i.e. the absolute height of the peak divided by the sum of the heights of the three highest peaks). Among P1 and P2 the peak P with location closest to the median of the PCF-values was selected. If the relative height of P was at least 0.2, then the PCF-values were centered by subtracting the location of P; otherwise, the PCF-values were centered by subtracting the location of the tallest of all the three peaks.

Whole Arm Aberration Index (WAAI)

WAAI was found separately for each arm and sample. The normalized PCF (NPCF) values were defined as the centered PCF-values divided by the residual standard deviation. The variable s was obtained by averaging NPCF over all probes. If s>0, WAAI was the 5% quantile of NPCF; if s≤0, WAAI was the 95% quantile of NPCF (in practice constrained to a predefined grid). Arms with WAAI≥0.8 were called as whole-arm gains, and arms with WAAI≤−0.8 were called as whole arm losses. See Fig. S2 for an example.

Complex Armwise Aberration Index (CAAI)

CAAI was found separately for each arm and sample. For each break point found by PCF, we calculated three scores P, Q and W, that reflected the proximity to neighboring break points, the magnitude of change and a weight of importance:

where α was a constant, L1, L2 the number of probes and H1, H2 the PCF-values for the segments joined at the break point. For any genomic subregion R we defined

by summing over all break points in R. We defined CAAI as the maximal value of SR across all subregions R of a predefined size of 20 Mb. The reason for using a window rather than calculating a score across the whole arm is to avoid spurious calls due to accumulation of isolated events not related to complex rearrangements. The size was a compromise between ensuring a local measure and including enough breakpoints to capture complex rearrangements. Table S5 contains all calculated WAAI and CAAI scores and the group designation for each sample.

Supplementary Material

Fig S1 Validation of CAAI

Fig. S2: Arm wise distribution of WAAI

Fig. S3: Frequencies of gains and loss in the four cohorts.

Fig. S4: Frequencies of whole arm alterations in the WAAI/CAAI groups.

Fig. S5: Chromosome wise frequencies of whole arm alterations in the WAAI/CAAI groups.

Fig. S6: Chromosome wise frequencies of high level CAAI in the WAAI/CAAI groups.

Fig. S7: Ploidy measurements and histological grade in the aCGH/CAAI groups.

Fig. S8: The tumor cell percentage related to expression subclasses and the WAAI/CAAI groups.

Fig. S9: The prognostic impact of the combined WAAI/CAAI groupsin all samples and the WAAI groups, CAAI groups and combined WAAI/CAAI groups in non-adjuvant treated patients.

Table S1: Demographic data for the four cohorts

Table S2: Distribution between the WAAI and CAAI groups in the four cohorts.

Table S3: Clinico-pathological characteristics of the four WAAI groups

Table S4: Correlation between intrinsic subgroups and WAAI and CAAI groups:

Table S5: Clinical data and WAAI/CAAI scores

Table S6: Multivariate Cox regression analysis of patients that did not receive adjuvant therapy, the risk of breast cancer specific death measured by the defined parameters CAAI and WAAI.

Table S7: REMARK profile of the study.

Table S8: Univariate Cox regression analysis showing hazard rates for different parameters in the four individual WAAI groups.

“This study demonstrates the relationship between structural genomic alterations, molecular subtype and clinical behavior, and shows that an objective score of genomic complexity can provide independent prognostic information in breast cancer.”

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Eldri U. Due for technical assistance.

Grants: ALBD: The Norwegian Research council, grant no. 155218/V40, 175240/S10, and The Norwegian Cancer Society, grant D99061. HGR and IHR have received grants from Radiumhospitalets Legater. CC received grant from Cancer Research UK, grant CRUK C507/A3086, Cancer Research UK NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, Cambridge Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre. BN and LOB received grant from Communities Sixth Framework Programme, project: DISMAL, contract no.: LSHC-CT-2005-018911. BN received funding from The Norwegian Cancer Association, Helse Sør-Øst and The Research Council of Norway. EB the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Cancer Society and Hlse Sør-Øst. AZ received grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, the Swedish Research Council and the Stockholm Cancer Society. OCL received funding from the norwegian Research Council.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Accession to data: The raw data and preprocessed data can be accessed from NCBI’s GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ ) with accession number GSE8757 (ChinUCAM), GSE20394 (Ull) and GSE19425 (MicMa and WZ).

The software used in this paper is written in Java and is available at http://www.ifi.uio.no/bioinf/Projects/GenomeArchitecture. A guide for the bioinformatic analysis is included on the webpage.

References

- 1.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365:1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de RM, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, Fluge O, Pergamenschikov A, Williams C, Zhu SX, Lonning PE, Borresen-Dale AL, Brown PO, Botstein D. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, Aas T, Geisler S, Johnsen H, Hastie T, Eisen MB, van de RM, Jeffrey SS, Thorsen T, Quist H, Matese JC, Brown PO, Botstein D, Eystein LP, Borresen-Dale AL. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:10869–10874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, Deng S, Johnsen H, Pesich R, Geisler S, Demeter J, Perou CM, Lonning PE, Brown PO, Borresen-Dale AL, Botstein D. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, Karaca G, Troester MA, Tse CK, Edmiston S, Deming SL, Geradts J, Cheang MC, Nielsen TO, Moorman PG, Earp HS, Millikan RC. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millikan RC, Newman B, Tse CK, Moorman PG, Conway K, Dressler LG, Smith LV, Labbok MH, Geradts J, Bensen JT, Jackson S, Nyante S, Livasy C, Carey L, Earp HS, Perou CM. Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2008;109:123–139. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9632-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalgin GS, Alexe G, Scanfeld D, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP, Ganesan S, DeLisi C, Bhanot G. Portraits of breast cancer progression. BMC. Bioinformatics. 2007;8:291. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergamaschi A, Kim YH, Wang P, Sorlie T, Hernandez-Boussard T, Lonning PE, Tibshirani R, Borresen-Dale AL, Pollack JR. Distinct patterns of DNA copy number alteration are associated with different clinicopathological features and gene-expression subtypes of breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes. Cancer. 2006;45:1033–1040. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin K, Devries S, Fridlyand J, Spellman PT, Roydasgupta R, Kuo WL, Lapuk A, Neve RM, Qian Z, Ryder T, Chen F, Feiler H, Tokuyasu T, Kingsley C, Dairkee S, Meng Z, Chew K, Pinkel D, Jain A, Ljung BM, Esserman L, Albertson DG, Waldman FM, Gray JW. Genomic and transcriptional aberrations linked to breast cancer pathophysiologies. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:529–541. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin SF, Wang Y, Thorne NP, Teschendorff AE, Pinder SE, Vias M, Naderi A, Roberts I, Barbosa-Morais NL, Garcia MJ, Iyer NG, Kranjac T, Robertson JF, Aparicio S, Tavare S, Ellis I, Brenton JD, Caldas C. Using array-comparative genomic hybridization to define molecular portraits of primary breast cancers. Oncogene. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teixeira MR, Pandis N, Heim S. Cytogenetic clues to breast carcinogenesis. Genes Chromosomes. Cancer. 2002;33:1–16. doi: 10.1002/gcc.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutrillaux B, Gerbault-Seureau M, Zafrani B. Characterization of chromosomal anomalies in human breast cancer. A comparison of 30 paradiploid cases with few chromosome changes. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1990;49:203–217. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(90)90143-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hicks J, Krasnitz A, Lakshmi B, Navin NE, Riggs M, Leibu E, Esposito D, Alexander J, Troge J, Grubor V, Yoon S, Wigler M, Ye K, Borresen-Dale AL, Naume B, Schlicting E, Norton L, Hagerstrom T, Skoog L, Auer G, Maner S, Lundin P, Zetterberg A. Novel patterns of genome rearrangement and their association with survival in breast cancer. Genome Res. 2006;16:1465–1479. doi: 10.1101/gr.5460106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephens PJ, McBride DJ, Lin ML, Varela I, Pleasance ED, Simpson JT, Stebbings LA, Leroy C, Edkins S, Mudie LJ, Greenman CD, Jia M, Latimer C, Teague JW, Lau KW, Burton J, Quail MA, Swerdlow H, Churcher C, Natrajan R, Sieuwerts AM, Martens JW, Silver DP, Langerod A, Russnes HE, Foekens JA, Reis-Filho JS, Richardson van, V, A. L., Borresen-Dale AL, Campbell PJ, Futreal PA, Stratton MR. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009;462:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nature08645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baumbusch LO, Aaroe J, Johansen FE, Hicks J, Sun H, Bruhn L, Gunderson K, Naume B, Kristensen VN, Liestol K, Borresen-Dale AL, Lingjaerde OC. Comparison of the Agilent, ROMA/NimbleGen and Illumina platforms for classification of copy number alterations in human breast tumors. BMC. Genomics. 2008;9:379. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin SF, Teschendorff AE, Marioni JC, Wang Y, Barbosa-Morais NL, Thorne NP, Costa JL, Pinder SE, van de Wiel MA, Green AR, Ellis IO, Porter PL, Tavare S, Brenton JD, Ylstra B, Caldas C. High-resolution aCGH and expression profiling identifies a novel genomic subtype of ER negative breast cancer. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R215. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-10-r215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adelaide J, Finetti P, Bekhouche I, Repellini L, Geneix J, Sircoulomb F, Charafe-Jauffret E, Cervera N, Desplans J, Parzy D, Schoenmakers E, Viens P, Jacquemier J, Birnbaum D, Bertucci F, Chaffanet M. Integrated profiling of basal and luminal breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11565–11575. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farabegoli F, Hermsen MA, Ceccarelli C, Santini D, Weiss MM, Meijer GA, van Diest PJ. Simultaneous chromosome 1q gain and 16q loss is associated with steroid receptor presence and low proliferation in breast carcinoma. Mod. Pathol. 2004;17:449–455. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincent-Salomon A, Gruel N, Lucchesi C, MacGrogan G, Dendale R, Sigal-Zafrani B, Longy M, Raynal V, Pierron G, Taris M. de, I, C., Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Pierga JY, Salmon R, Sastre-Garau X, Fourquet A, Delattre O, de CP, Aurias A. Identification of typical medullary breast carcinoma as a genomic sub-group of basal-like carcinomas, a heterogeneous new molecular entity. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R24. doi: 10.1186/bcr1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johannsdottir HK, Jonsson G, Johannesdottir G, Agnarsson BA, Eerola H, Arason A, Heikkila P, Egilsson V, Olsson H, Johannsson OT, Nevanlinna H, Borg A, Barkardottir RB. Chromosome 5 imbalance mapping in breast tumors from BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers and sporadic breast tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 2006;119:1052–1060. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tirkkonen M, Johannsson O, Agnarsson BA, Olsson H, Ingvarsson S, Karhu R, Tanner M, Isola J, Barkardottir RB, Borg A, Kallioniemi OP. Distinct somatic genetic changes associated with tumor progression in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ-line mutations. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1222–1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fridlyand J, Snijders AM, Ylstra B, Li H, Olshen A, Segraves R, Dairkee S, Tokuyasu T, Ljung BM, Jain AN, McLennan J, Ziegler J, Chin K, Devries S, Feiler H, Gray JW, Waldman F, Pinkel D, Albertson DG. Breast tumor copy number aberration phenotypes and genomic instability. BMC. Cancer. 2006;6:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molist R, Remvikos Y, Dutrillaux B, Muleris M. Characterization of a new cytogenetic subtype of ductal breast carcinomas. Oncogene. 2004;23:5986–5993. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Letessier A, Sircoulomb F, Ginestier C, Cervera N, Monville F, Gelsi-Boyer V, Esterni B, Geneix J, Finetti P, Zemmour C, Viens P, Charafe-Jauffret E, Jacquemier J, Birnbaum D, Chaffanet M. Frequency, prognostic impact, and subtype association of 8p12, 8q24, 11q13, 12p13, 17q12, and 20q13 amplifications in breast cancers. BMC. Cancer. 2006;6:245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paterson AL, Pole JC, Blood KA, Garcia MJ, Cooke SL, Teschendorff AE, Wang Y, Chin SF, Ylstra B, Caldas C, Edwards PA. Co-amplification of 8p12 and 11q13 in breast cancers is not the result of a single genomic event. Genes Chromosomes. Cancer. 2007;46:427–439. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reis-Filho JS, Savage K, Lambros MB, James M, Steele D, Jones RL, Dowsett M. Cyclin D1 protein overexpression and CCND1 amplification in breast carcinomas: an immunohistochemical and chromogenic in situ hybridisation analysis. Mod. Pathol. 2006;19:999–1009. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell PJ, Stephens PJ, Pleasance ED, O’Meara S, Li H, Santarius T, Stebbings LA, Leroy C, Edkins S, Hardy C, Teague JW, Menzies A, Goodhead I, Turner DJ, Clee CM, Quail MA, Cox A, Brown C, Durbin R, Hurles ME, Edwards PA, Bignell GR, Stratton MR, Futreal PA. Identification of somatically acquired rearrangements in cancer using genome-wide massively parallel paired-end sequencing. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:722–729. doi: 10.1038/ng.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langerod A, Zhao H, Borgan O, Nesland JM, Bukholm IR, Ikdahl T, Karesen R, Borresen-Dale AL, Jeffrey SS. TP53 mutation status and gene expression profiles are powerful prognostic markers of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2007;9:R30. doi: 10.1186/bcr1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naume B, Zhao X, Synnestvedt M, Borgen E, Russnes HG, Lingjaerde OC, Stromberg M, Wiedswang G, Kvalheim G, Karesen R, Nesland JM, Borresen-Dale AL, Sorlie T. Presence of bone marrow micrometastasis is associated with different recurrence risk within molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2007;1:160–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lusa L, McShane LM, Reid JF, De CL, Ambrogi F, Biganzoli E, Gariboldi M, Pierotti MA. Challenges in projecting clustering results across gene expression-profiling datasets. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1715–1723. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loi S, Sotiriou C, Haibe-Kains B, Lallemand F, Conus NM, Piccart MJ, Speed TP, McArthur GA. Gene expression profiling identifies activated growth factor signaling in poor prognosis (Luminal-B) estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. BMC. Med. Genomics. 2009;2:37. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peppercorn J, Perou CM, Carey LA. Molecular subtypes in breast cancer evaluation and management: divide and conquer. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:1–10. doi: 10.1080/07357900701784238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Git A, Spiteri I, Blenkiron C, Dunning MJ, Pole JC, Chin SF, Wang Y, Smith J, Livesey FJ, Caldas C. PMC42, a breast progenitor cancer cell line, has normal-like mRNA and microRNA transcriptomes. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R54. doi: 10.1186/bcr2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sieuwerts AM, Kraan J, Bolt J, van der SP, Elstrodt F, Schutte M, Martens JW, Gratama JW, Sleijfer S, Foekens JA. Anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecule antibodies and the detection of circulating normal-like breast tumor cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009;101:61–66. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stefansson OA, Jonasson JG, Johannsson OT, Olafsdottir K, Steinarsdottir M, Valgeirsdottir S, Eyfjord JE. Genomic profiling of breast tumours in relation to BRCA abnormalities and phenotypes. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R47. doi: 10.1186/bcr2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navin N, Krasnitz A, Rodgers L, Cook K, Meth J, Kendall J, Riggs M, Eberling Y, Troge J, Grubor V, Levy D, Lundin P, Maner S, Zetterberg A, Hicks J, Wigler M. Inferring tumor progression from genomic heterogeneity. Genome Res. 2010;20:68–80. doi: 10.1101/gr.099622.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. REporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) Br. J. Cancer. 2005;93:387–391. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsarouha H, Pandis N, Bardi G, Teixeira MR, Andersen JA, Heim S. Karyotypic evolution in breast carcinomas with i(1)(q10) and der(1;16)(q10;p10) as the primary chromosome abnormality. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1999;113:156–161. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baudis M. Genomic imbalances in 5918 malignant epithelial tumors: an explorative meta-analysis of chromosomal CGH data. BMC. Cancer. 2007;7:226. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buerger H, Mommers EC, Littmann R, Simon R, Diallo R, Poremba C, Dockhorn-Dworniczak B, van Diest PJ, Boecker W. Ductal invasive G2 and G3 carcinomas of the breast are the end stages of at least two different lines of genetic evolution. J. Pathol. 2001;194:165–170. doi: 10.1002/path.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korsching E, Packeisen J, Helms MW, Kersting C, Voss R, van Diest PJ, Brandt B, van der WE, Boecker W, Burger H. Deciphering a subgroup of breast carcinomas with putative progression of grade during carcinogenesis revealed by comparative genomic hybridisation (CGH) and immunohistochemistry. Br. J. Cancer. 2004;90:1422–1428. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdel-Fatah TM, Powe DG, Hodi Z, Reis-Filho JS, Lee AH, Ellis IO. Morphologic and molecular evolutionary pathways of low nuclear grade invasive breast cancers and their putative precursor lesions: further evidence to support the concept of low nuclear grade breast neoplasia family. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2008;32:513–523. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318161d1a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Natrajan R, Lambros MB, Geyer FC, Marchio C, Tan DS, Vatcheva R, Shiu KK, Hungermann D, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Palacios J, Ashworth A, Buerger H, Reis-Filho JS. Loss of 16q in high grade breast cancer is associated with estrogen receptor status: Evidence for progression in tumors with a luminal phenotype? Genes Chromosomes. Cancer. 2009;48:351–365. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rennstam K, Baldetorp B, Kytola S, Tanner M, Isola J. Chromosomal rearrangements and oncogene amplification precede aneuploidization in the genetic evolution of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1214–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Loo P, Nordgard SH, Lingjaerde OC, Russnes HG, Rye IH, Sun W, Weigman VJ, Marynen P, Zetterberg A, Naume B, Perou CM, Borresen-Dale AL, Kristensen VN. Allele-specific copy number analysis of tumors. Unpublished. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Courjal F, Cuny M, Simony-Lafontaine J, Louason G, Speiser P, Zeillinger R, Rodriguez C, Theillet C. Mapping of DNA amplifications at 15 chromosomal localizations in 1875 breast tumors: definition of phenotypic groups. Cancer Res. 1997;57:4360–4367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kamalakaran S, Russnes HG, Janevski A, Levy D, Kendall J, Varadan V, Riggs M, Banerjee N, Synnestvedt M, Schlichting E, Kåresn R, Lucito R, Wigler M, Dimirova N, Naume B, Borresen-Dale AL, Hicks J. Subtype dependent alterations of the DNA methylation landscape in breast cancer. Abstract, SABCS. 2009.

- 48.Dontu G, El-Ashry D, Wicha MS. Breast cancer, stem/progenitor cells and the estrogen receptor. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;15:193–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polyak K. Breast cancer: origins and evolution. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:3155–3163. doi: 10.1172/JCI33295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sims AH, Howell A, Howell SJ, Clarke RB. Origins of breast cancer subtypes and therapeutic implications. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2007;4:516–525. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kao J, Salari K, Bocanegra M, Choi YL, Girard L, Gandhi J, Kwei KA, Hernandez-Boussard T, Wang P, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, Pollack JR. Molecular profiling of breast cancer cell lines defines relevant tumor models and provides a resource for cancer gene discovery. PLoS. ONE. 2009;4:e6146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neve RM, Chin K, Fridlyand J, Yeh J, Baehner FL, Fevr T, Clark L, Bayani N, Coppe JP, Tong F, Speed T, Spellman PT, Devries S, Lapuk A, Wang NJ, Kuo WL, Stilwell JL, Pinkel D, Albertson DG, Waldman FM, McCormick F, Dickson RB, Johnson MD, Lippman M, Ethier S, Gazdar A, Gray JW. A collection of breast cancer cell lines for the study of functionally distinct cancer subtypes. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:515–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teschendorff AE, Miremadi A, Pinder SE, Ellis IO, Caldas C. An immune response gene expression module identifies a good prognosis subtype in estrogen receptor negative breast cancer. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R157. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lim E, Vaillant F, Wu D, Forrest NC, Pal B, Hart AH, sselin-Labat ML, Gyorki DE, Ward T, Partanen A, Feleppa F, Huschtscha LI, Thorne HJ, Fox SB, Yan M, French JD, Brown MA, Smyth GK, Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Aberrant luminal progenitors as the candidate target population for basal tumor development in BRCA1 mutation carriers. Nat. Med. 2009;15:907–913. doi: 10.1038/nm.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McClintock B. The Behavior in Successive Nuclear Divisions of a Chromosome Broken at Meiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1939;25:405–416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.25.8.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McClintock B. The Stability of Broken Ends of Chromosomes in Zea Mays. Genetics. 1941;26:234–282. doi: 10.1093/genetics/26.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iakovlev VV, Arneson NC, Wong V, Wang C, Leung S, Iakovleva G, Warren K, Pintilie M, Done SJ. Genomic differences between pure ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast and that associated with invasive disease: a calibrated aCGH study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:4446–4454. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wiedswang G, Borgen E, Karesen R, Kvalheim G, Nesland JM, Qvist H, Schlichting E, Sauer T, Janbu J, Harbitz T, Naume B. Detection of isolated tumor cells in bone marrow is an independent prognostic factor in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:3469–3478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lucito R, Healy J, Alexander J, Reiner A, Esposito D, Chi M, Rodgers L, Brady A, Sebat J, Troge J, West JA, Rostan S, Nguyen KC, Powers S, Ye KQ, Olshen A, Venkatraman E, Norton L, Wigler M. Representational oligonucleotide microarray analysis: a high-resolution method to detect genome copy number variation. Genome Res. 2003;13:2291–2305. doi: 10.1101/gr.1349003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Barrett MT, Scheffer A, Ben-Dor A, Sampas N, Lipson D, Kincaid R, Tsang P, Curry B, Baird K, Meltzer PS, Yakhini Z, Bruhn L, Laderman S. Comparative genomic hybridization using oligonucleotide microarrays and total genomic DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:17765–17770. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407979101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van den Ijssen, Tijssen M, Chin SF, Eijk P, Carvalho B, Hopmans E, Holstege H, Bangarusamy DK, Jonkers J, Meijer GA, Caldas C, Ylstra B. Human and mouse oligonucleotide-based array CGH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:e192. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, Zhang J. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Forsslund G, Nilsson B, Zetterberg A. Near tetraploid prostate carcinoma. Methodologic and prognostic aspects. Cancer. 1996;78:1748–1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Forsslund G, Zetterberg A. Ploidy level determinations in high-grade and low-grade malignant variants of prostatic carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1990;50:4281–4285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lingjaerde OC, Baumbusch LO, Liestol K, Glad IK, Borresen-Dale AL. CGH-Explorer: a program for analysis of array-CGH data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:821–822. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coe BP, Ylstra B, Carvalho B, Meijer GA, Macaulay C, Lam WL. Resolving the resolution of array CGH. Genomics. 2007;89:647–653. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Curtis C, Lynch AG, Dunning MJ, Spiteri I, Marioni JC, Hadfield J, Chin SF, Brenton JD, Tavare S, Caldas C. The pitfalls of platform comparison: DNA copy number array technologies assessed. BMC. Genomics. 2009;10:588. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig S1 Validation of CAAI

Fig. S2: Arm wise distribution of WAAI

Fig. S3: Frequencies of gains and loss in the four cohorts.

Fig. S4: Frequencies of whole arm alterations in the WAAI/CAAI groups.

Fig. S5: Chromosome wise frequencies of whole arm alterations in the WAAI/CAAI groups.

Fig. S6: Chromosome wise frequencies of high level CAAI in the WAAI/CAAI groups.

Fig. S7: Ploidy measurements and histological grade in the aCGH/CAAI groups.

Fig. S8: The tumor cell percentage related to expression subclasses and the WAAI/CAAI groups.

Fig. S9: The prognostic impact of the combined WAAI/CAAI groupsin all samples and the WAAI groups, CAAI groups and combined WAAI/CAAI groups in non-adjuvant treated patients.

Table S1: Demographic data for the four cohorts

Table S2: Distribution between the WAAI and CAAI groups in the four cohorts.

Table S3: Clinico-pathological characteristics of the four WAAI groups

Table S4: Correlation between intrinsic subgroups and WAAI and CAAI groups:

Table S5: Clinical data and WAAI/CAAI scores

Table S6: Multivariate Cox regression analysis of patients that did not receive adjuvant therapy, the risk of breast cancer specific death measured by the defined parameters CAAI and WAAI.

Table S7: REMARK profile of the study.

Table S8: Univariate Cox regression analysis showing hazard rates for different parameters in the four individual WAAI groups.