Abstract

The Tibetan Plateau is one of the highest regions on Earth. Tibetan highlanders are adapted to life and reproduction in a hypoxic environment and possess a suite of distinctive physiological traits. Recent studies have identified genomic loci that have undergone natural selection in Tibetans. Two of these loci, EGLN1 and EPAS1, encode major components of the hypoxia-inducible factor transcriptional system, which has a central role in oxygen sensing and coordinating an organism's response to hypoxia, as evidenced by studies in humans and mice. An association between genetic variants within these genes and hemoglobin concentration in Tibetans at high altitude was demonstrated in some of the studies (8, 80, 96). Nevertheless, the functional variants within these genes and the underlying mechanisms of action are still not known. Furthermore, there are a number of other possible phenotypic traits, besides hemoglobin concentration, upon which natural selection may have acted. Integration of studies at the genomic level with functional molecular studies and studies in systems physiology has the potential to provide further understanding of human evolution in response to high-altitude hypoxia. The Tibetan paradigm provides further insight on the role of the hypoxia-inducible factor system in humans in relation to oxygen homeostasis.

Keywords: hypoxia-inducible factor, EPAS1, EGLN1, evolution, Tibetan, adaptation

the severely reduced oxygen availability at high altitude, termed hypobaric hypoxia, presents a significant challenge to the ability of humans residing there to live and reproduce. As such, it is likely to have acted as an agent of natural selection. Three human populations have lived at high altitude for millennia: Andeans on the Andean Altiplano, Tibetans on the Tibetan Plateau, and Ethiopians on the Semian Plateau. Of these, Tibetans appear to have lived at high altitude the longest. According to archeological and other data, e.g., genetic studies, humans have lived on the Tibetan Plateau, one of the highest regions on Earth with an average elevation of ∼4,000 m, a barometric pressure of <500 mmHg, and an inspired partial pressure of oxygen of ∼80 Torr, for at least 25,000 yr (1, 2, 71, 101). In contrast, it is estimated that the Andean Altiplano was first populated approximately only 11,000 yr ago (2), while the Amhara population in Ethiopia is assumed to have settled at high altitude for ∼5,000 yr (3). This suggests that Tibetans will have had more time and opportunity for natural selection in response to a hypoxic environment than any other high-altitude human population.

Over the last few decades, much research has been done to investigate how Tibetans are adapted to life in a hypoxic environment. Compared with other high-altitude populations and lowland natives who emigrated to high altitude, Tibetans were found to exhibit distinctive physiological traits and to be resistant to certain pathophysiological processes. While in a number of studies these traits exhibited a great degree of heritability (7, 11, 12, 20), it was largely unknown whether the distinctive high-altitude Tibetan phenotype was the result of natural selection. It is only recently, within the last few years, i.e., in the postgenomic era, that advances in genomic technology and science have made it possible to gather evidence of natural selection in Tibetans and to implicate certain genes in their genetic adaptation. Nevertheless, the functional variants within these genes and the underlying mechanisms involved are still unknown.

In this review, we highlight the dominant physiological features of Tibetans living at high altitude. We then review the findings of recent studies investigating genetic selection in Tibetans. We discuss how the genes identified as strong candidates for a role in Tibetans' evolutionary adaptation to high altitude are involved in human physiological processes related to oxygen homeostasis. We discuss and speculate on the potential physiological trait(s) upon which natural selection has acted. Finally, we consider how the evolutionary paradigm of the Tibetan high-altitude adaptation provides insights and raises questions on the role of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) system in humans who live at sea level.

TIBETAN PHYSIOLOGY AT HIGH ALTITUDE

The human response to hypoxia is characterized by systemic changes in cardiovascular, respiratory, and hematopoietic physiology, which affect convective oxygen transport. Central to the Tibetan high-altitude phenotype is the fact that certain components of convective oxygen transport are markedly different in Tibetans compared with other humans living at high altitude. In this review, most comparisons are made between Tibetans and Andeans, as the physiology of these two populations has been extensively studied. In contrast, significantly less is known about the physiology of the Ethiopian highlanders.

An immediate rise in ventilation is the most obvious response of human lowlanders exposed to acute high-altitude hypoxia, followed by more complex time-dependent changes with prolonged exposure (69). Tibetan highlanders resemble acclimatized newcomers in that they maintain a high resting ventilation and brisk hypoxic ventilatory sensitivities (32, 36), whereas Andeans exhibit a considerable degree of ventilatory blunting (46, 78). Indeed, Tibetan highlanders had elevated resting ventilation and augmented acute hypoxic ventilatory responses when compared directly with Han Chinese long-term residents of the same altitude (102) or Bolivian Aymaras resident in the Andes (11).

Hypoxia constricts rather than dilates the human pulmonary vasculature (59). Regional hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV) distributes blood away from hypoxic regions of the lung and can be beneficial in maintaining perfusion-ventilation matching. However, a consequence of HPV is that global hypoxia, such as that experienced at high altitude, leads to pulmonary arterial hypertension and right heart strain. Tibetan highlanders, in contrast to their Andean counterparts or other high-altitude residents, exhibit a relative resistance to developing pulmonary hypertension. This was demonstrated directly in a study of five Tibetans resident at 3,658 m who had pulmonary arterial pressures within sea level norms that were little changed by additional hypoxia (27). Consistent with this is the demonstration of elevated nitric oxide, a vasodilator, in the lungs of Tibetans compared with Andean highlanders and lowlanders at sea level (10, 34). Furthermore, a study demonstrated lack of smooth muscle in the small pulmonary arteries in Tibetan men at 3,600 m, consistent with the absence of pronounced pulmonary vascular remodeling and hypertrophy that accompanies pulmonary hypertension (30).

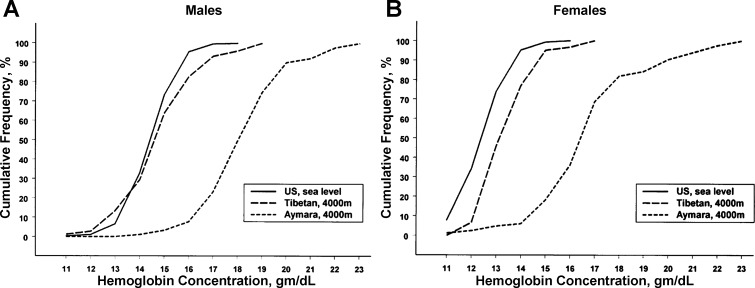

A hallmark of high-altitude hypoxic exposure in humans is the rise in red cell mass accompanied by elevated hemoglobin (Hb) concentration and hematocrit, which is associated with a rise in blood erythropoietin (Epo) levels (73). Perhaps the most striking phenotypic difference between Tibetan highlanders and other high-altitude residents is their blunted erythropoietic response to hypoxia. This is evident by the fact that, at similar high altitudes, Tibetans have significantly lower Hb concentrations, typically 1–3.5 g/dl lower, than their Andean counterparts or Han Chinese migrants to high altitude (7, 26, 55, 90). Tibetans exhibit little or no increase in Hb concentration with increasing altitude (6, 91), and, at 4,000 m, both male and female Tibetans have Hb concentrations comparable to those of US sea level residents (7) (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative frequency distribution of hemoglobin concentrations in US residents at sea level and Tibetan and Bolivian Aymara natives at 4,000 m. A: results for men. B: results for women. [From Beall et al. (7).]

Chronic mountain sickness (CMS) is a high-altitude disorder linked with the above components of oxygen transport. It is a syndrome of adaptive failure to chronic hypoxia characterized by excessive erythrocytosis with abnormally high Hb and hematocrit levels, hypoventilation, pulmonary hypertension, and eventually right heart failure (47, 53). It occurs in adults after prolonged residence at high altitude and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (40, 60). Of interest is the remarkably low prevalence of CMS in Tibetan highlanders compared with other high-altitude populations, such as Andeans or Han Chinese migrants to high altitude (54). The overall prevalence of CMS in Tibetans living on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau was 1.2% compared with 5.6% in Han Chinese (92). Using the same criteria as Monge et al. (53) to define CMS, i.e., [Hb] >21.3 g/dl and arterial O2 saturation < 83%, a lower prevalence was reported in Tibetans (0.9%) at 4,300 m (Madu) (93) compared with Peruvian Quechuas (15.6%) at the same altitude (Cerro De Pasco) (53).

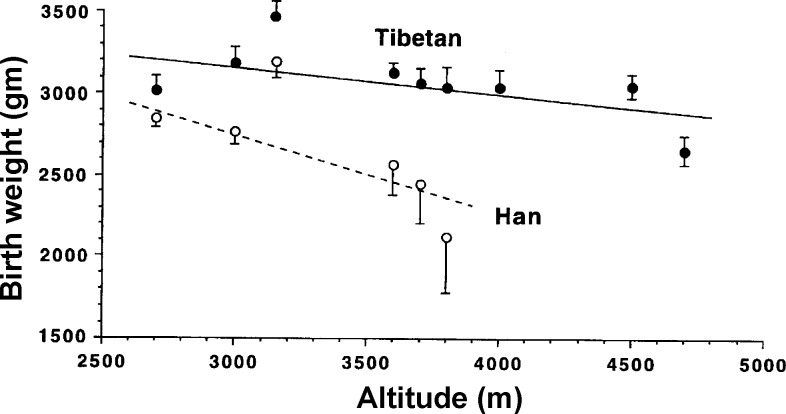

Another characteristic of the Tibetan population is a relative protection against the occurrence of intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), which is associated with low birth weight at high altitude. It is well recognized that reproductive success is more difficult at high than low altitude, especially among nonnatives (43). Birth weight progressively reduces with increasing altitude across populations (41, 56, 97). However, the magnitude of this fall in birth weight varies among populations: it is smaller in populations that have lived for multiple generations at high altitude (31, 57, 99), such as Tibetans and Andeans, suggesting that genetic factors play a role. Not only were heavier birth weights observed in Tibetans compared with Han Chinese at the same altitude, but the pre- and postnatal mortality was threefold higher in Han Chinese than Tibetans (57). Figure 2 shows the birth weight reduction with altitude for Tibetan and Han Chinese. To explain these differences, various studies have focused on oxygen delivery to the placenta and found that they are associated with differences in uterine artery (UA) blood flow, as opposed to changes in ventilation, Hb concentration, or Hb saturation in pregnant women. Higher UA flow velocities (58) and larger UA diameters (17) were observed in pregnant Tibetan compared with Han Chinese women. Analogous results have been found in studies of Andean populations; a doubling of the UA diameter during pregnancy was demonstrated in Andean women but not in European women at high altitude, an effect seen only under circumstances of chronic hypoxia but not at low altitude (42, 89, 100). The underlying mechanisms for these observations, and whether they are the same in Tibetans and Andeans, are not currently known.

Fig. 2.

Birth weight plotted against altitude of residence for Tibetans and Han Chinese, showing a significantly smaller birth weight fall with increasing altitude in Tibetans than in Han Chinese. Values are means ± SE. [From Moore et al. (57).]

The phenotypic characteristics of Ethiopian highlanders have not been examined as extensively. Amhara Ethiopians at 3,500 m were reported to have low Hb concentrations comparable with those of lowlanders (3, 9), resembling Tibetans; however, Scheinfeldt et al. (75) observed higher Hb concentration in high-altitude Amharas compared with lowlanders. Pulmonary arterial pressure, on the other hand, was found to be elevated in Ahmara highlanders (35).

The distinctive oxygen-transport traits found in Tibetans compared with other high-altitude populations, together with reports of intrapopulation heritability, have been interpreted as demonstrating the presence of genetic influences on high-altitude adaptation. Moreover, the association of these traits to disorders such as CMS and IUGR, which have the potential to influence reproduction and survival, suggests that some of these phenotypic characteristics, alone or in combination, may be offering an evolutionary survival benefit to Tibetans.

STUDIES OF THE TIBETAN GENOME: EVIDENCE OF NATURAL SELECTION

Recent genome-wide analyses in Tibetans provided the first lines of evidence that this population has undergone genetic adaptation to high altitude. These studies used different methodologies to compare the Tibetan genome with genomes of closely related ethnic backgrounds, such as the Han Chinese (8, 13, 62, 80, 88, 95, 96). The rationale was that any differences captured in the genetic structure between the two populations are likely to have arisen through natural selection in response to the hypoxic environment inhabited by the Tibetans. These studies have been extensively reviewed (5, 51, 76, 79). The studies are summarized in Table 1, and the key findings are discussed below.

Table 1.

Summary of genome-wide studies of high altitude adaptation in Tibetans

| Study | Populations | Methodology (Approach and Platform) | HIF Pathway Genes Identified |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simonson et al. (80) | 1. Tibetan highlanders from Qinghai Province (n = 31) vs. lowland HapMap CHB and JPT (n = 90) | 1. XP-EHH, iHS (Affymetrix 6.0 SNP array) | EGLN1 (& EPAS1) |

| 2. Tibetan highlanders (n = 29) from Qinghai Province | 2. Candidate gene association study (Hb concentration) | ||

| Beall et al. (8) | 1. Tibetan highlanders from Yunnan Province (n = 35) vs. lowland HapMap CHB (n = 84) | 1. GWADS (Illumina 610-Quad SNP array) | EPAS1 |

| 2. Tibetan highlanders from Mag Xiang, Tibet Autonomous Region (n = 70) and from Zhaxizong Xiang, Tibet Autonomous Region (n = 91) | 2. Candidate gene association study (Hb concentration) | ||

| Yi et al. (96) | 1. Tibetan highlanders from Tibetan Autonomous Region (n = 50) vs. lowland HapMap CHB (n = 40) and Danish controls (n = 100) | 1. PBS (Exome Sequencing, Illumina) | EPAS1 |

| 2. Tibetan highlanders from Tibetan Autonomous Region (n = 366) | 2. Candidate gene association study (erythrocyte count) | ||

| Bigham et al. (13) | Tibetan highlanders from Tibetan Autonomous region (n = 50) vs. lowland HapMap East Asian (n = 60) and European controls (n = 90) | LSBL, lnRH, Taj D, WGLRH (Affymetrix 6.0 SNP array) | EGLN1 (& EPAS1) |

| Peng et al. (62) | 1. Tibetan highlanders from Qinghai Province (n = 50) vs. lowland HapMap CHB/JPT | 1. XP-CLR, FST (Affymetrix 6.0 SNP array) | EPAS1 (& EGLN1) |

| 2. Tibetan highlanders from Qinghai Province (n = 50) vs. lowland HapMap CHB/JPT/YRI/CEU | 2. Full-length sequencing of EPAS1 (haplotype construction, FST) | ||

| 3. Tibetan highlanders from Tibetan Autonomous Region, Qinghai, and Yunnan Provinces (n = 1,334) | 3. Candidate gene SNP genotyping for allele frequency comparisons | ||

| Xu et al. (95) | Tibetan highlanders from Tibet (Shannan, Rikaza, Linzhi, Lasha, and Changdu) (n = 46) vs. Han Chinese (n = 92), YRI (n = 60), CEU (n = 60), and JPT (n = 44) from HapMap | FST, iHS, XP-EHH (Affymetrix 6.0 SNP array), haplotype construction | EPAS1& EGLN1 |

| Wang et al. (88) | Tibetan highlanders from near Lhasa (n = 30) vs. lowland HapMap CHB (n = 45), JPT (n = 45), CEU (n = 59), and YRI (n = 60) and East Asian from HGDP | FST, iHS, XP-EHH (Illumina 1M) | EPAS1 (& EGLN1) |

HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; CHB, Han Chinese in Beijing, China; JPT, Japanese in Tokyo, Japan; YRI, Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria; CEU, Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry; HGDP, human genome diversity project; XP-EHH, cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity; iHS, integrated haplotype score; GWADS, genome-wide allelic differentiation scan; PBS, population branch statistic; LSBL, locus-specific branch length; lnRH, natural logarithm of ratio of heterozygosities; Taj D, Tajima's D statistic; WGLRH, whole genome long-range haplotype; XP-CLR, cross-population composite likelihood ratio test; FST, fixation index. The basis of these and other techniques are described in recent reviews (15, 80).

Simonson et al. (80) performed a genome-wide comparison of Tibetan and Han Chinese or Japanese populations. They identified chromosomal regions of positive selective sweeps by calculating two separate genomic statistics: the cross-population extended haplotype homozygosity statistic (XP-EHH), and the integrated haplotype score (iHS) for 200-kb non-overlapping genomic regions. The basis of these and other techniques is described in recent reviews (15, 82). They then scanned the positive regions for 247 a priori selected candidate genes (based on their involvement in oxygen homeostasis) and found 10 genes that were located in or near these regions. Among these genes were EPAS1, EGLN1, and PPARA, with EGLN1 identified by both genomic statistics. In addition, in a cohort of 29 Tibetans, genetic variants in the latter two genes were associated with Hb concentration such that the selected haplotype in each gene was correlated with low Hb concentration. However, people with excessive erythrocytosis or anemia were not excluded from this genotype-phenotype analysis.

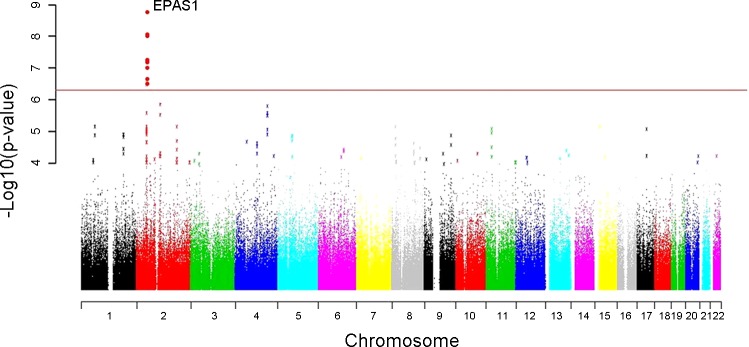

Beall et al. (8) used a genome-wide allelic differentiation scan (GWADS) to compare ∼500,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between Tibetan high-altitude natives (from the Yunnan province) and lowland Han Chinese (see Fig. 3). This provided a completely unbiased genome-wide analysis investigating genetic selection, with no a priori assumptions or hypotheses. They found eight SNPs that achieved genome-wide significance (P values ranging from 2.81 × 10−7 to 1.49 × 10−9) in terms of their divergence between the two ethnic groups, which clustered within ∼235 kb on chromosome 2, just downstream of EPAS1. These SNPs were found to be in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) with one another: i.e., they were associated with each other in a nonrandom way such that they occurred together more often than expected by chance. This extended haplotype was present at high frequencies in Tibetans (46%) and low frequencies (2%) in Han Chinese. In addition, through candidate gene approaches in two further separate cohorts of Tibetans, they identified ∼30 SNPs in EPAS1 in high LD (consistent with a dominant variant hypothesis) that correlated significantly with Hb concentration. The correlation was such that major allele (alias “Tibetan” allele) homozygotes averaged a Hb concentration of ∼1 g/dl lower than the heterozygotes in each separate cohort. These EPAS1 SNPs were found at higher frequencies in Tibetans than in Han Chinese and were in high LD with the signal from the genome-wide allelic differentiation scan, thus providing evidence for selection on EPAS1 associated with low Hb concentration in Tibetan highlanders.

Fig. 3.

Genome-wide allelic differentiation scans comparing Tibetan highlanders and HapMap Han Chinese. Eight single nucleotide polymorphisms near EPAS1 achieved genome-wide significance. [From Beall et al. (8).]

Yi et al. (96) sequenced 50 Tibetan exomes and compared the sequencing data with Han Chinese and Danish populations to identify changes in allelic frequencies consistent with genetic adaptation in Tibetans. Using population branch statistics (PBS), they identified EPAS1 as the strongest candidate gene for natural selection. In addition, the most differentiated (in terms of allelic frequency) EPAS1 variant was correlated with erythrocyte count within a larger Tibetan cohort. This was an intronic EPAS1 SNP, which was captured by this exome-targeted approach and was found at 87% frequency in Tibetans compared with 9% in Han Chinese. Interestingly, no coding genetic variants were identified to be highly differentiated between the populations. This leads to suggest that adaptation to high altitude has not proceeded by way of selection on coding variants that might be expected to alter protein structure and function. Based on their analyses, they estimated a Tibetan-Han divergence time of 2,750 yr, which is far more recent than previously estimated based on archeological data or other analyses (1, 62, 101). This short divergence time has been disputed; it has been argued that it may be related to a complex mosaic of the Tibetan population created by multiple migrations at different times into the Plateau and to the small sample sizes in the study (1).

Xu et al. (95) compared genome-wide allelic frequencies between Tibetan and Han Chinese and identified 6 EGLN1 SNPs and 25 EPAS1 SNPs among the top differentiated SNPs (top 0.0001% SNPs with FST statistic > 0.3). They went on to identify positive selective sweeps and dominant haplotypes in EPAS1 and EGLN1 genes in Tibetans and also showed a correlation of the prevalence of the dominant haplotypes for these genes with altitude of residence.

Peng et al. (62) SNP-typed 50 Tibetan individuals and compared the results with data from HapMap Han Chinese, identifying EPAS1 as one of the genes that underwent a selective sweep in Tibetans. They also sequenced the full length of the EPAS1 gene in these individuals and showed marked allelic differentiation at this locus between Tibetans and Han Chinese. They constructed haplotypes, and further analysis allowed an estimation of a divergence time for Tibetans that was sixfold greater than that of Yi et al. (96) and consistent with previous archeological and genetic reports (1, 2, 101). They also genotyped three SNPs from each of EPAS1, EGLN1, and PPARA in a large cohort of 1,334 Tibetans. They found significant differences in allele frequencies for the EPAS1 SNPs between Tibetan and Han Chinese/Japanese and also for one of the SNPs in EGLN1.

Wang et al. (88) performed a number of tests of selection using genome-wide SNP data from 30 Tibetans living near Lhasa and identified the EPAS1 locus as the strongest signal of positive selection in the Tibetan genome. The second most significant genomic region with evidence of positive selection was a region containing the EGLN1 gene.

Bigham et al. (13) performed high-density genome scans and applied four population genetic statistics to identify selection-nominated candidate genes and candidate regions for two high-altitude populations, Andeans and Tibetans. These two populations were studied separately. They found different patterns of positive selection for the two populations. In Tibetans, a genomic region containing EPAS1 exhibited significant variation between Tibetans and the lowland comparators, HapMap Asians. Interestingly, EGLN1 showed evidence of positive selection in both Tibetans and Andeans, although the SNP frequencies and haplotypes are different between the two populations.

While EGLN1 was identified as undergoing selection in both Tibetans and Andeans, neither EPAS1 or EGLN1 featured as candidates in recent genomic studies in Ethiopian highlanders (3, 37, 75). Other, different, candidate genes have been found in these studies. PPARA, however, which was previously reported as a selection candidate in Tibetans (80), was also identified as a selection candidate gene in highland Ethiopians with a marginal association with Hb concentration (75). Thus different high-altitude populations evolved independently to adapt to the challenges of a hypoxic environment. However, of interest is that, in the study by Huerta-Sanchez et al. (37), the top candidate gene, DEC1, is functionally related to the oxygen-sensing pathway; it is transcriptionally regulated by HIF-1α, directly binds HIF-1α, downregulates HIF-1α and HIF-2α protein expression, and represses many HIF-target genes. It is likely these interpopulation differences in genetic adaptation relate to the length of high-altitude inhabitation, the severity of the hypoxic stimulus, the different genetic backgrounds, different opportunities for admixture with lowlanders, and evolutionary chance.

Additional genes that may have undergone selection in Tibetans with rather weaker signals of selection do exist and have been reported in the various studies (29, 80, 96). However, what is striking when considering the convergent findings of all of the studies to date is the independent identification of positive selection in Tibetans (from different geographic locations) at genomic loci that involve EPAS1 (which codes for HIF-2α) and EGLN1 [which codes for prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) 2], both key components of the HIF pathway, thus implicating these genes in the genetic adaptation of Tibetans to high altitude.

EPAS1 AND EGLN1: THE HIF TRANSCRIPTIONAL PATHWAY

HIFs are a family of transcription factors that coordinate oxygen sensing and intracellular responses to hypoxia through regulation of expression of hundreds of genes belonging to biological pathways such as energy metabolism, angiogenesis, erythropoiesis, iron homeostasis, apoptosis, and others (77).

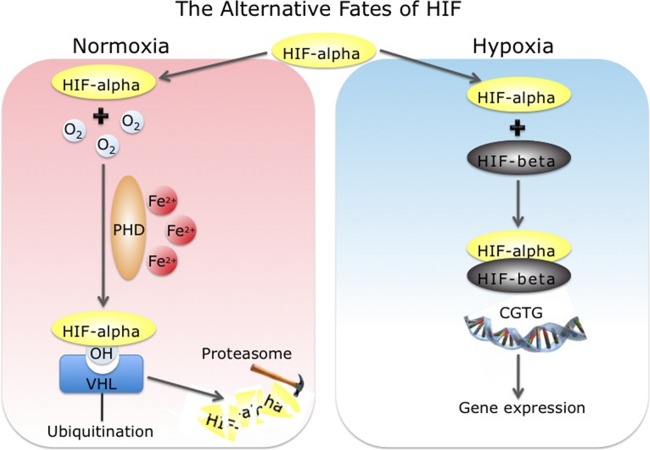

EPAS1 encodes HIF-2α (87), which is one of three HIF-α subunit isoforms. In the presence of oxygen, HIF-α is hydroxylated at two proline residues by PHD enzymes, of which there are three isoforms, PHD1, PHD2 (coded by the EGLN1 gene), and PHD3, in an oxygen-dependent manner (22, 38, 39). This hydroxylation enhances the binding of the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) protein to HIF-α, which in turn enhances HIF-α ubiquitination, resulting in its subsequent rapid proteasomal degradation (18, 39). In hypoxia, the reduced hydroxylase activity of the PHD enzymes results in the stabilization and accumulation of the HIF-α subunits, which then heterodimerize with HIF-β and transcriptionally activate target genes (Fig. 4). Evidence for a central role of the HIF pathway, and more specifically for EPAS1 (HIF-2α) and EGLN1 (PHD2), in systemic erythropoiesis, but also in other aspects of integrative physiology related to oxygen homeostasis, comes from studying patients with genetic abnormalities in the HIF system and from genetic mouse models. The most extensively studied patients are those with Chuvash polycythemia, who are homozygous for a hypomorphic allele of the VHL tumor suppressor, which impairs HIF-1α and HIF-2α degradation (4). These patients have excessive erythrocytosis with high Hb and hematocrit levels due to an upregulation of Epo production. Apart from VHL, gain-of-function mutations in EPAS1 leading to stabilization of HIF-2α (64, 65, 67) and mutations in EGLN1 associated with diminished activity of PHD2 (45, 66) have also been identified in patients with excessive erythrocytosis.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-α by hypoxia. In the presence of oxygen (O2) and iron (Fe2+), prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes hydroxylate specific proline residues in HIF-α, increasing the binding of the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor protein. This targets HIF-α for ubiquitination and mediates its proteosmal degradation. In hypoxia, HIF-α accumulates, dimerizes with HIF-β, binds to DNA, and transcriptionally regulates hypoxia-responsive genes. [Courtesy of Dr. Federico Formenti, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.]

Further phenotyping has shown that patients with Chuvash polycythemia have abnormal cardiopulmonary physiology. They have pulmonary hypertension, increased resting ventilation, and, upon exposure to acute systemic hypoxia, they exhibit an exaggerated pulmonary vascular response and an exaggerated ventilatory sensitivity (81). In addition, they have abnormal metabolism during exercise with a reduced maximal exercise capacity, an increased exercise-induced lactate accumulation, and an early and marked phosphocreatine depletion and acidosis in skeletal muscle (24). In contrast, patients with gain-of-function HIF-2α mutations have a more restricted cardiopulmonary phenotype of pulmonary hypertension and exaggerated pulmonary vascular responses to acute hypoxia (23, 25).

Studies in genetically modified mice further elucidated the role of the HIF pathway in systemic physiology. Both HIF-1α- and HIF-2α-null mice die during embryogenesis (61, 74). Postnatal deletion of HIF-2α in a conditional mouse model resulted in anemia and demonstrated that HIF-2α, rather than HIF-1α, is the critical isoform regulating erythropoiesis in adults (28). Mice with heterozygous deficiency for functional HIF genes, either HIF-1α (98) or HIF-2α (16), developed less polycythemia and pulmonary hypertension in response to hypoxia. Mouse models of Chuvash polycythemia confirmed the phenotype of increased ventilation and pulmonary hypertension found in humans and further demonstrated that the effects seen in the disease are primarily HIF-2α driven as opposed to HIF-1α driven (33). Similarly, a mouse model of the human HIF-2α gain-of-function mutation recapitulated the phenotype of excessive erythrocytosis and pulmonary hypertension in a dose-dependent manner (86). Knockout mice with heterozygous loss of HIF-1α had depressed carotid body oxygen sensitivity and abnormal ventilatory acclimatization to chronic hypoxia (44). In contrast, HIF-2α+/− mice manifested heightened carotid responses to hypoxia, highlighting potentially different roles of HIF-1 and HIF-2 in systemic physiology (63). Germline PHD2−/− mice are not viable (85). PHD2 conditional knockout mice developed excessive erythrocytosis and increased vascular growth (83, 84), and mice heterozygous for PHD2 had increased ventilatory sensitivity to hypoxia and carotid body hyperplasia (14).

The above findings highlight the key role of the HIF pathway as a master controller of oxygen sensing and regulator of systemic physiology in humans and mice. It is evident that perturbations of the HIF pathway, whether leading to an upregulation or a downregulation of the hypoxic HIF response, act on components of convective oxygen transport such as ventilation, hypoxic pulmonary vascular response, and erythropoiesis and produce phenotypic changes. Interestingly, it is these components of oxygen transport that are distinctive in Tibetan highlanders and make up their high-altitude phenotype, as previously mentioned, alluding to a role of the HIF pathway in their adaptation to hypoxia. This is discussed below, where we consider the potential physiological trait(s) upon which natural selection may have acted.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE CONSIDERATIONS

We have briefly reviewed the evidence that genetic variation in the HIF pathway affects hematopoietic and cardiopulmonary physiology in humans. The similarities between the phenotype of lowland patients with genetic mutations in the HIF pathway that “upregulate” the HIF response with the phenotype of patients with CMS at high altitude are remarkable. Coupling these observations with the recent studies identifying EPAS1 and EGLN1 as loci that have undergone recent positive selection in Tibetans (8, 13, 62, 80, 95, 96) suggests that natural selection to hypoxia in Tibetans may have occurred through genetic variation in the HIF pathway, which operated on related integrative-physiology phenotypes. Several questions remain unanswered.

One question relates to the identification of the “substrate” of natural selection, in other words, the phenotype on which selection occurred. In some reports, the putatively selected “Tibetan” genetic variants were associated with lower Hb concentrations at high altitude (8, 80, 96). Several possibilities exist. One is that blunted erythropoiesis may be beneficial for highlanders, and that low Hb concentration may be the “selected” phenotype. Arguments in favor of this are the association of excessive erythrocytosis with CMS, which poses significant morbidity and mortality risks, and the remarkably low prevalence of CMS in the Tibetan population. On the other hand, the higher Hb and hematocrit levels found in the Andean populations are not always associated with disease and do not preclude the Andeans from being a growing population at high altitude, suggesting that blunted erythropoiesis alone may not be a sufficient enough advantage to drive genetic selection in Tibetans. Another possibility is that the phenotype of low-Hb concentration is selected only as part of a more complex integrative phenotype that offers a survival advantage at high altitude, owing to the pleiotropic effects of the HIF pathway, and of EPAS1 in particular. It is even possible that the hematopoietic phenotype may actually be a secondary outcome, or even a “side effect”, of the selection process, which may have acted on some other aspect of the phenotype. Apart from affecting cardiopulmonary physiology, EPAS1 plays roles in placenta and embryonic development (19, 52, 70) and may be involved in IUGR (21). Of particular interest is that the placenta is one of the tissues where high expression of HIF-2α is found (72). The increased reproductive ability of Tibetans, as evident by the low pre- and postnatal mortality compared with Han Chinese high-altitude residents, coupled with their resistance to IUGR, suggests that natural selection on EPAS1 may have also operated via effects during pregnancy on fetal growth. The study of associations between birth weight at high altitude and genotype is a potentially fruitful area of investigation.

A further question to consider is whether the effects of the genetic variation in EPAS1 and EGLN1 selected for in Tibetans are functional and operate in generating a phenotype only in conditions of severe and ongoing, i.e., for years, environmental hypoxia. It is of interest that, while genetic variants in EPAS1 and EGLN1 were significantly correlated with Hb concentration in Tibetan highlanders, neither EPAS1 nor EGLN1 featured in any of a number of genome-wide studies exploring genetic determinants of Hb concentration at sea level (22–24). This suggests that either the genetic variation in EPAS1 or EGLN1 relates to a hematopoietic phenotype only in conditions of severe and prolonged environmental hypoxia, or that the “functional” genetic variants in these genes are unique to Tibetans, naturally selected by living for generations in hypoxia. This raises an interesting question as to whether lessons can be learned from the Tibetan paradigm on the role of the HIF system near sea level. An ensuing fundamental question is to what degree the physiological responses that lowland humans exhibit when exposed to high altitude, e.g., erythropoietic and cardiopulmonary, can be considered adaptive to a reduction in ambient oxygen as opposed to “mishaps” arising from oxygen-sensing mechanisms that have been optimized to operate at “normal” oxygen levels found at sea level. Accordingly, the HIF system in humans may have been optimized to sculpt structure and physiological function using oxygen as a guiding signal rather than to respond to environmental hypoxic challenges. For example, reduced oxygen delivery to the kidneys is used as a guiding signal to stimulate Epo production through an upregulated HIF system to restore reductions in Hb or hematocrit levels, e.g., in anemia or hemorrhage, rather than to respond to environmental oxygen changes. Similarly, HPV, in which the HIF system plays a role, is a process evolved at sea level and is fundamental for the fetal circulation in utero, but it can be maladaptive in response to reductions in environmental oxygen.

Recently, Petousi et al. (68) studied ethnic Tibetans living at sea level in the UK and provided a first report of their phenotype in the absence of on-going, severe environmental hypoxia. In this study, Tibetans resident at sea level had a lower Hb concentration, a higher resting ventilation, and blunted pulmonary vascular responses to both acute (minutes) and sustained (8 h) hypoxic challenges compared with Han Chinese lowlanders. The physiological studies were complemented with cellular studies, which showed that the relative expression and the hypoxic induction of HIF-regulated genes were significantly lower in peripheral blood lymphocytes from Tibetans compared with Han Chinese. Thus this study provided evidence that Tibetans possess a hypo-responsive HIF system and demonstrated that a phenotype is present at sea level in the absence of on-going environmental hypoxia to activate the HIF system. Indeed, Tibetans are the first humans in whom a hypo-responsive HIF system has been demonstrated, and this may represent an evolutionary resetting of the HIF system to operate within a hypoxic environment.

Nonetheless, for the genes that have undergone natural selection in Tibetans, neither the functional variants nor the mechanisms by which they may be operating have been identified to date. In the case of EPAS1, all of the genetic variants reported in Tibetans to date are found in noncoding regions, either within introns of EPAS1 or downstream of EPAS1; whole exome sequencing (96) or targeted sequencing of the full-length EPAS1 gene (62) in Tibetans failed to reveal any coding genetic variants as functional candidates. Thus it is likely that “functional” genetic variation in Tibetans might lie in regulatory regions and actually affect transcription of the EPAS1 gene itself, as opposed to downstream HIF-2α structure and function. In keeping with such a possibility, Petousi et al. (68) reported lower HIF-2α mRNA expression in peripheral blood lymphocytes from Tibetan than from Han Chinese volunteers, which may be related to lower levels of transcription of EPAS1. In the case of EGLN1, two coding variants have been described of particularly high frequencies in Tibetans (48, 49, 50, 94), although their effect on PHD2 protein structure and function are not yet known. Functional molecular studies are required to unravel the “causal” variants in the candidate genes and their mechanism of action. Further exploration of Tibetan physiology by integrating studies at the genomic level with functional molecular studies and whole-system phenotyping has the potential to yield important additional insights into human evolution in response to the environment of high-altitude hypoxia.

GRANTS

N. Petousi was funded by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Training Research Fellowship (Grant 089457/Z/09/Z).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: N.P. drafted manuscript; N.P. and P.A.R. edited and revised manuscript; N.P. and P.A.R. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldenderfer M. Peopling the Tibetan plateau: insights from archaeology. High Alt Med Biol 12: 141–147, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldenderfer MS. Moving up in the world. Am Sci 91: 542–549, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkorta-Aranburu G, Beall CM, Witonsky DB, Gebremedhin A, Pritchard JK, Di Rienzo A. The genetic architecture of adaptations to high altitude in Ethiopia. PLoS Genet 8: e1003110, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ang SO, Chen H, Hirota K, Gordeuk VR, Jelinek J, Guan Y, Liu E, Sergueeva AI, Miasnikova GY, Mole D, Maxwell PH, Stockton DW, Semenza GL, Prchal JT. Disruption of oxygen homeostasis underlies congenital Chuvash polycythemia. Nat Genet 32: 614–621, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beall CM. Genetic changes in Tibet. High Alt Med Biol 12: 101–102, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beall CM. Two routes to functional adaptation: Tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104, Suppl 1: 8655–8660, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beall CM, Brittenham GM, Strohl KP, Blangero J, Williams-Blangero S, Goldstein MC, Decker MJ, Vargas E, Villena M, Soria R, Alarcon AM, Gonzales C. Hemoglobin concentration of high-altitude Tibetans and Bolivian Aymara. Am J Phys Anthropol 106: 385–400, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beall CM, Cavalleri GL, Deng L, Elston RC, Gao Y, Knight J, Li C, Li JC, Liang Y, McCormack M, Montgomery HE, Pan H, Robbins PA, Shianna KV, Tam SC, Tsering N, Veeramah KR, Wang W, Wangdui P, Weale ME, Xu Y, Xu Z, Yang L, Zaman MJ, Zeng C, Zhang L, Zhang X, Zhaxi P, Zheng YT. Natural selection on EPAS1 (HIF2alpha) associated with low hemoglobin concentration in Tibetan highlanders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 11459–11464, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beall CM, Decker MJ, Brittenham GM, Kushner I, Gebremedhin A, Strohl KP. An Ethiopian pattern of human adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 17215–17218, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beall CM, Laskowski D, Strohl KP, Soria R, Villena M, Vargas E, Alarcon AM, Gonzales C, Erzurum SC. Pulmonary nitric oxide in mountain dwellers. Nature 414: 411–412, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beall CM, Strohl KP, Blangero J, Williams-Blangero S, Almasy LA, Decker MJ, Worthman CM, Goldstein MC, Vargas E, Villena M, Soria R, Alarcon AM, Gonzales C. Ventilation and hypoxic ventilatory response of Tibetan and Aymara high altitude natives. Am J Phys Anthropol 104: 427–447, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beall CM, Strohl KP, Blangero J, Williams-Blangero S, Decker MJ, Brittenham GM, Goldstein MC. Quantitative genetic analysis of arterial oxygen saturation in Tibetan highlanders. Hum Biol 69: 597–604, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bigham A, Bauchet M, Pinto D, Mao X, Akey JM, Mei R, Scherer SW, Julian CG, Wilson MJ, Lopez Herraez D, Brutsaert T, Parra EJ, Moore LG, Shriver MD. Identifying signatures of natural selection in Tibetan and Andean populations using dense genome scan data. PLoS Genet 6: e1001116, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bishop T, Talbot NP, Turner PJ, Nicholls LG, Pascual A, Hodson EJ, Douglas G, Fielding JW, Smith TG, Demetriades M, Schofield CJ, Robbins PA, Pugh CW, Buckler KJ, Ratcliffe PJ. Carotid body hyperplasia and enhanced ventilatory responses to hypoxia in mice with heterozygous deficiency of PHD2. J Physiol 591: 3565–3577, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biswas S, Akey JM. Genomic insights into positive selection. Trends Genet 22: 437–446, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brusselmans K, Compernolle V, Tjwa M, Wiesener MS, Maxwell PH, Collen D, Carmeliet P. Heterozygous deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha protects mice against pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular dysfunction during prolonged hypoxia. J Clin Invest 111: 1519–1527, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen D, Zhou X, Zhu Y, Zhu T, Wang J. [Comparison study on uterine and umbilical artery blood flow during pregnancy at high altitude and at low altitude]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 37: 69–71, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cockman ME, Masson N, Mole DR, Jaakkola P, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Maher ER, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Maxwell PH. Hypoxia inducible factor-alpha binding and ubiquitylation by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein. J Biol Chem 275: 25733–25741, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowden Dahl KD, Fryer BH, Mack FA, Compernolle V, Maltepe E, Adelman DM, Carmeliet P, Simon MC. Hypoxia-inducible factors 1alpha and 2alpha regulate trophoblast differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 25: 10479–10491, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curran LS, Zhuang J, Sun SF, Moore LG. Ventilation and hypoxic ventilatory responsiveness in Chinese-Tibetan residents at 3,658 m. J Appl Physiol 83: 2098–2104, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai SY, Kanenishi K, Ueno M, Sakamoto H, Hata T. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha is involved in enhanced apoptosis in the placenta from pregnancies with fetal growth restriction. Pathol Int 54: 843–849, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, Hewitson KS, O'Rourke J, Mole DR, Mukherji M, Metzen E, Wilson MI, Dhanda A, Tian YM, Masson N, Hamilton DL, Jaakkola P, Barstead R, Hodgkin J, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell 107: 43–54, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Formenti F, Beer PA, Croft QP, Dorrington KL, Gale DP, Lappin TR, Lucas GS, Maher ER, Maxwell PH, McMullin MF, O'Connor DF, Percy MJ, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Smith TG, Talbot NP, Robbins PA. Cardiopulmonary function in two human disorders of the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) pathway: von Hippel-Lindau disease and HIF-2alpha gain-of-function mutation. FASEB J 25: 2001–2011, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Formenti F, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Emmanuel Y, Cheeseman J, Dorrington KL, Edwards LM, Humphreys SM, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, McNamara CJ, Mills W, Murphy JA, O'Connor DF, Percy MJ, Ratcliffe PJ, Smith TG, Treacy M, Frayn KN, Greenhaff PL, Karpe F, Clarke K, Robbins PA. Regulation of human metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107: 12722–12727, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gale DP, Harten SK, Reid CD, Tuddenham EG, Maxwell PH. Autosomal dominant erythrocytosis and pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with an activating HIF2 alpha mutation. Blood 112: 919–921, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garruto RM, Chin CT, Weitz CA, Liu JC, Liu RL, He X. Hematological differences during growth among Tibetans and Han Chinese born and raised at high altitude in Qinghai, China. Am J Phys Anthropol 122: 171–183, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groves BM, Droma T, Sutton JR, McCullough RG, McCullough RE, Zhuang J, Rapmund G, Sun S, Janes C, Moore LG. Minimal hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in normal Tibetans at 3,658 m. J Appl Physiol 74: 312–318, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gruber M, Hu CJ, Johnson RS, Brown EJ, Keith B, Simon MC. Acute postnatal ablation of Hif-2alpha results in anemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 2301–2306, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu M, Dong X, Shi L, Lin K, Huang X, Chu J. Differences in mtDNA whole sequence between Tibetan and Han populations suggesting adaptive selection to high altitude. Gene 496: 37–44, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta ML, Rao KS, Anand IS, Banerjee AK, Boparai MS. Lack of smooth muscle in the small pulmonary arteries of the native Ladakhi. Is the Himalayan highlander adapted? Am Rev Respir Dis 145: 1201–1204, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haas JD. Human adaptability approach to nutritional assessment: a Bolivian example. Fed Proc 40: 2577–2582, 1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hackett PH, Reeves JT, Reeves CD, Grover RF, Rennie D. Control of breathing in Sherpas at low and high altitude. J Appl Physiol 49: 374–379, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hickey MM, Richardson T, Wang T, Mosqueira M, Arguiri E, Yu H, Yu QC, Solomides CC, Morrisey EE, Khurana TS, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Simon MC. The von Hippel-Lindau Chuvash mutation promotes pulmonary hypertension and fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 827–839, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoit BD, Dalton ND, Erzurum SC, Laskowski D, Strohl KP, Beall CM. Nitric oxide and cardiopulmonary hemodynamics in Tibetan highlanders. J Appl Physiol 99: 1796–1801, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoit BD, Dalton ND, Gebremedhin A, Janocha A, Zimmerman PA, Zimmerman AM, Strohl KP, Erzurum SC, Beall CM. Elevated pulmonary artery pressure among Amhara highlanders in Ethiopia. Am J Hum Biol 23: 168–176, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang ZR, Zhu SC, Ba ZF, Hu ST. Ventilatory control in Tibetan highlanders. In: Geological and Ecological Studies Of Qinghai-Xizang Plateau, edited by Liu DS. Beijing, PRC: Science, 1981, p. 1363–1369 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huerta-Sanchez E, Degiorgio M, Pagani L, Tarekegn A, Ekong R, Antao T, Cardona A, Montgomery HE, Cavalleri GL, Robbins PA, Weale ME, Bradman N, Bekele E, Kivisild T, Tyler-Smith C, Nielsen R. Genetic signatures reveal high-altitude adaptation in a set of Ethiopian populations. Mol Biol Evol 30: 1877–1888, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivan M, Haberberger T, Gervasi DC, Michelson KS, Gunzler V, Kondo K, Yang H, Sorokina I, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Kaelin WG., Jr Biochemical purification and pharmacological inhibition of a mammalian prolyl hydroxylase acting on hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 13459–13464, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, Wilson MI, Gielbert J, Gaskell SJ, Kriegsheim A, Hebestreit HF, Mukherji M, Schofield CJ, Maxwell PH, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292: 468–472, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaillard AS, Hommel M, Mazetti P. Prevalence of stroke at high altitude (3380 m) in Cuzco, a town of Peru. A population-based study. Stroke 26: 562–568, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen GM, Moore LG. The effect of high altitude and other risk factors on birth weight: independent or interactive effects? Am J Public Health 87: 1003–1007, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Julian CG, Wilson MJ, Lopez M, Yamashiro H, Tellez W, Rodriguez A, Bigham AW, Shriver MD, Rodriguez C, Vargas E, Moore LG. Augmented uterine artery blood flow and oxygen delivery protect Andeans from altitude-associated reductions in fetal growth. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R1564–R1575, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Julian CG, Wilson MJ, Moore LG. Evolutionary adaptation to high altitude: a view from in utero. Am J Hum Biol 21: 614–622, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kline DD, Peng YJ, Manalo DJ, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Defective carotid body function and impaired ventilatory responses to chronic hypoxia in mice partially deficient for hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 821–826, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ladroue C, Hoogewijs D, Gad S, Carcenac R, Storti F, Barrois M, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Leporrier M, Casadevall N, Hermine O, Kiladjian JJ, Baruchel A, Fakhoury F, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Feunteun J, Mazure N, Pouyssegur J, Wenger RH, Richard S, Gardie B. Distinct deregulation of the hypoxia inducible factor by PHD2 mutants identified in germline DNA of patients with polycythemia. Haematologica 97: 9–14, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lahiri S, Kao FF, Velasque T, Martinez C, Pezzia W. Irreversible blunted respiratory sensitivity to hypoxia in high altitude natives. Respiration Physiology 6: 360–374, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leon-Velarde F, Maggiorini M, Reeves JT, Aldashev A, Asmus I, Bernardi L, Ge RL, Hackett P, Kobayashi T, Moore LG, Penaloza D, Richalet JP, Roach R, Wu T, Vargas E, Zubieta-Castillo G, Zubieta-Calleja G. Consensus statement on chronic and subacute high altitude diseases. High Alt Med Biol 6: 147–157, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lorenzo FPV, Swierczek S, Huff CD, Prchal JT. The Tibetan PHD2 polymorphism Asp4Glu is associated with hypersensitivity of erythroid progenitors to EPO and upregulation of HIF-1 regulated genes hexokinase (HK1) and glucose transporter 1 (SLC2A/GLUT1). In: Proceedings of the 53rd ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition, 2011. Washington, DC: American Society of Hematology, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lorenzo FRV, Simonson TS, Yang Y, Ge R, Prchal JT. A novel PHD2 mutation associated with Tibetan genetic adaptation to high altitude hypoxia. In: Proceedings of the 52nd ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition, 2010. Washington, DC: American Society of Hematology, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lorenzo FRVST, Yang Y, Ge R, Prchal JT. A novel PHD2 mutation associated with Tibetan genetic adaptation to high altitude hypoxia. In: Proceedings of the 54th ASH Annual Meeting and Exposition, 2012. Washington, DC: American Society of Hematology, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacInnis MJ, Rupert JL. 'ome on the range: altitude adaptation, positive selection, and Himalayan genomics. High Alt Med Biol 12: 133–139, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meade ES, Ma YY, Guller S. Role of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors 1alpha and 2alpha in the regulation of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression in a human trophoblast cell line. Placenta 28: 1012–1019, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monge C, Arregui CA, Leonvelarde F. Pathophysiology and epidemiology of chronic mountain-sickness. Int J Sports Med 13: S79–S81, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moore LG, Armaza F, Villena M, Vargas E. Comparative aspects of high-altitude adaptation in human populations. Adv Exp Med Biol 475: 45–62, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moore LG, Curran-Everett L, Droma TS, Groves BM, McCullough RE, McCullough RG, Sun SF, Sutton JR, Zamudio S, Zhuang JG. Are Tibetans better adapted? Int J Sports Med 13, Suppl 1: S86–S88, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore LG, Shriver M, Bemis L, Hickler B, Wilson M, Brutsaert T, Parra E, Vargas E. Maternal adaptation to high-altitude pregnancy: an experiment of nature–a review. Placenta 25, Suppl A: S60–S71, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore LG, Young D, McCullough RE, Droma T, Zamudio S. Tibetan protection from intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) and reproductive loss at high altitude. Am J Hum Biol 13: 635–644, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore LG, Zamudio S, Zhuang J, Sun S, Droma T. Oxygen transport in Tibetan women during pregnancy at 3,658 m. Am J Phys Anthropol 114: 42–53, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Motley HL, Cournand A, Werko L, Himmelstein A, Dresdale D. The influence of short periods of induced acute anoxia upon pulmonary artery pressures in man. Am J Physiol 150: 315–320, 1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Penaloza D, Arias-Stella J. The heart and pulmonary circulation at high altitudes: healthy highlanders and chronic mountain sickness. Circulation 115: 1132–1146, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Peng J, Zhang L, Drysdale L, Fong GH. The transcription factor EPAS-1/hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha plays an important role in vascular remodeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 8386–8391, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peng Y, Yang Z, Zhang H, Cui C, Qi X, Luo X, Tao X, Wu T, Ouzhuluobu Basang Ciwangsangbu Danzengduojie Chen H, Shi H, Su B. Genetic variations in Tibetan populations and high-altitude adaptation at the Himalayas. Mol Biol Evol 28: 1075–1081, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Khan SA, Yuan G, Wang N, Kinsman B, Vaddi DR, Kumar GK, Garcia JA, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2alpha (HIF-2alpha) heterozygous-null mice exhibit exaggerated carotid body sensitivity to hypoxia, breathing instability, and hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108: 3065–3070, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Percy MJ, Beer PA, Campbell G, Dekker AW, Green AR, Oscier D, Rainey MG, van Wijk R, Wood M, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, Lee FS. Novel exon 12 mutations in the HIF2A gene associated with erythrocytosis. Blood 111: 5400–5402, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Percy MJ, Chung YJ, Harrison C, Mercieca J, Hoffbrand AV, Dinardo CL, Santos PC, Fonseca GH, Gualandro SF, Pereira AC, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, Lee FS. Two new mutations in the HIF2A gene associated with erythrocytosis. Am J Hematol 87: 439–442, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Percy MJ, Furlow PW, Beer PA, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, Lee FS. A novel erythrocytosis-associated PHD2 mutation suggests the location of a HIF binding groove. Blood 110: 2193–2196, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Percy MJ, Furlow PW, Lucas GS, Li X, Lappin TR, McMullin MF, Lee FS. A gain-of-function mutation in the HIF2A gene in familial erythrocytosis. N Engl J Med 358: 162–168, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Petousi N, Croft QPP, Cavalleri GL, Cheng HY, Formenti F, Ishida K, Lunn D, McCormack M, Shianna KV, Talbot NP, Ratcliffe PJ, Robbins PA. Tibetans living at sea level have a hyporesponsive hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) system and blunted physiological responses to hypoxia. J Appl Physiol 10.1152/japplphysiol.00535.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Powell FL, Milsom WK, Mitchell GS. Time domains of the hypoxic ventilatory response. Respir Physiol 112: 123–134, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pringle KG, Kind KL, Sferruzzi-Perri AN, Thompson JG, Roberts CT. Beyond oxygen: complex regulation and activity of hypoxia inducible factors in pregnancy. Hum Reprod Update 16: 415–431, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qi X, Cui C, Peng Y, Zhang X, Yang Z, Zhong H, Zhang H, Xiang K, Cao X, Wang Y, Ouzhuluobu Basang Ciwangsangbu Bianba Gonggalanzi Wu T, Chen H, Shi H, Su B. Genetic evidence of paleolithic colonization and neolithic expansion of modern humans on the Tibetan plateau. Mol Biol Evol 30: 1761–1778, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rajakumar A, Conrad KP. Expression, ontogeny, and regulation of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors in the human placenta. Biol Reprod 63: 559–569, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Richalet JP, Souberbielle JC, Antezana AM, Dechaux M, Le Trong JL, Bienvenu A, Daniel F, Blanchot C, Zittoun J. Control of erythropoiesis in humans during prolonged exposure to the altitude of 6,542 m. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 266: R756–R764, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ryan HE, Lo J, Johnson RS. HIF-1 alpha is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization. EMBO J 17: 3005–3015, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scheinfeldt LB, Soi S, Thompson S, Ranciaro A, Woldemeskel D, Beggs W, Lambert C, Jarvis JP, Abate D, Belay G, Tishkoff SA. Genetic adaptation to high altitude in the Ethiopian highlands. Genome Biol 13: R1, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scheinfeldt LB, Tishkoff SA. Living the high life: high-altitude adaptation. Genome Biol 11: 133, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schofield CJ, Ratcliffe PJ. Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 343–354, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Severinghaus JW, Bainton CR, Carcelen A. Respiratory insensitivity to hypoxia in chronically hypoxic man. Respir Physiol 1: 308–334, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Simonson TS, McClain DA, Jorde LB, Prchal JT. Genetic determinants of Tibetan high-altitude adaptation. Hum Genet 131: 527–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Simonson TS, Yang Y, Huff CD, Yun H, Qin G, Witherspoon DJ, Bai Z, Lorenzo FR, Xing J, Jorde LB, Prchal JT, Ge R. Genetic evidence for high-altitude adaptation in Tibet. Science 329: 72–75, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Smith TG, Brooks JT, Balanos GM, Lappin TR, Layton DM, Leedham DL, Liu C, Maxwell PH, McMullin MF, McNamara CJ, Percy MJ, Pugh CW, Ratcliffe PJ, Talbot NP, Treacy M, Robbins PA. Mutation of von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor and human cardiopulmonary physiology. PLoS Med 3: e290, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Suzuki Y. Statistical methods for detecting natural selection from genomic data. Genes Genet Syst 85: 359–376, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Takeda K, Aguila HL, Parikh NS, Li X, Lamothe K, Duan LJ, Takeda H, Lee FS, Fong GH. Regulation of adult erythropoiesis by prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins. Blood 111: 3229–3235, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Takeda K, Cowan A, Fong GH. Essential role for prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2 in oxygen homeostasis of the adult vascular system. Circulation 116: 774–781, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Takeda K, Ho VC, Takeda H, Duan LJ, Nagy A, Fong GH. Placental but not heart defects are associated with elevated hypoxia-inducible factor alpha levels in mice lacking prolyl hydroxylase domain protein 2. Mol Cell Biol 26: 8336–8346, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tan Q, Kerestes H, Percy MJ, Pietrofesa R, Chen L, Khurana TS, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Lappin TR, Lee FS. Erythrocytosis and pulmonary hypertension in a mouse model of human HIF2A gain-of-function mutation. J Biol Chem 288: 17134–17144, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tian H, McKnight SL, Russell DW. Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 (EPAS1), a transcription factor selectively expressed in endothelial cells. Genes Dev 11: 72–82, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang B, Zhang YB, Zhang F, Lin H, Wang X, Wan N, Ye Z, Weng H, Zhang L, Li X, Yan J, Wang P, Wu T, Cheng L, Wang J, Wang DM, Ma X, Yu J. On the origin of Tibetans and their genetic basis in adapting high-altitude environments. PLoS One 6: e17002, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilson MJ, Lopez M, Vargas M, Julian C, Tellez W, Rodriguez A, Bigham A, Armaza JF, Niermeyer S, Shriver M, Vargas E, Moore LG. Greater uterine artery blood flow during pregnancy in multigenerational (Andean) than shorter-term (European) high-altitude residents. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R1313–R1324, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Winslow RM, Chapman KW, Gibson CC, Samaja M, Monge CC, Goldwasser E, Sherpa M, Blume FD, Santolaya R. Different hematologic responses to hypoxia in Sherpas and Quechua Indians. J Appl Physiol 66: 1561–1569, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wu T, Wang X, Wei C, Cheng H, Li Y, Ge D, Zhao H, Young P, Li G, Wang Z. Hemoglobin levels in Qinghai-Tibet: different effects of gender for Tibetans vs. Han. J Appl Physiol 98: 598–604, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu TY, Li W, Li Y, Ge RL, Cheng Q, Wang S, Zhao G, Wei L, Jin Y, Don G. Epidemiology of Chronic Mountain Sickness: Ten years' study in Qinghai, Tibet. Progress in Mountain Medicine and High Altitude Physiology. Press Committee of the 3rd World Congress on Mountain Medicine and High Altitude Physiology, Matsumoto, Japan, 1998, p. 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wu TY, Zhang Q, Jin B, Xu F, Cheng Q, Wan X. Chronic Mountain Sickness (Monge's disease): An observation in Qinghai-Tibet plateau. In: High Altitude Medicine, edited by Ueda G. Matsumoto, Japan: Shinshu University Press, 1992, p. 314–324 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xiang K, Ouzhuluobu Peng Y, Yang Z, Zhang X, Cui C, Zhang H, Li M, Zhang Y, Bianba Gonggalanzi Basang Ciwangsangbu Wu T, Chen H, Shi H, Qi X, Su B. Identification of a Tibetan-specific mutation in the hypoxic gene EGLN1 and its contribution to high-altitude adaptation. Mol Biol Evol 30: 1889–1898, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu S, Li S, Yang Y, Tan J, Lou H, Jin W, Yang L, Pan X, Wang J, Shen Y, Wu B, Wang H, Jin L. A genome-wide search for signals of high-altitude adaptation in Tibetans. Mol Biol Evol 28: 1003–1011, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yi X, Liang Y, Huerta-Sanchez E, Jin X, Cuo ZX, Pool JE, Xu X, Jiang H, Vinckenbosch N, Korneliussen TS, Zheng H, Liu T, He W, Li K, Luo R, Nie X, Wu H, Zhao M, Cao H, Zou J, Shan Y, Li S, Yang Q, Asan Ni P, Tian G, Xu J, Liu X, Jiang T, Wu R, Zhou G, Tang M, Qin J, Wang T, Feng S, Li G, Huasang Luosang J, Wang W, Chen F, Wang Y, Zheng X, Li Z, Bianba Z, Yang G, Wang X, Tang S, Gao G, Chen Y, Luo Z, Gusang L, Cao Z, Zhang Q, Ouyang W, Ren X, Liang H, Huang Y, Li J, Bolund L, Kristiansen K, Li Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Li R, Yang H, Nielsen R, Wang J. Sequencing of 50 human exomes reveals adaptation to high altitude. Science 329: 75–78, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yip R. Altitude and birth weight. J Pediatr 111: 869–876, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yu AY, Shimoda LA, Iyer NV, Huso DL, Sun X, McWilliams R, Beaty T, Sham JS, Wiener CM, Sylvester JT, Semenza GL. Impaired physiological responses to chronic hypoxia in mice partially deficient for hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. J Clin Invest 103: 691–696, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zamudio S, Droma T, Norkyel KY, Acharya G, Zamudio JA, Niermeyer SN, Moore LG. Protection from intrauterine growth retardation in Tibetans at high altitude. Am J Phys Anthropol 91: 215–224, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zamudio S, Postigo L, Illsley NP, Rodriguez C, Heredia G, Brimacombe M, Echalar L, Torricos T, Tellez W, Maldonado I, Balanza E, Alvarez T, Ameller J, Vargas E. Maternal oxygen delivery is not related to altitude- and ancestry-associated differences in human fetal growth. J Physiol 582: 883–895, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhao M, Kong QP, Wang HW, Peng MS, Xie XD, Wang WZ, Jiayang Duan JG, Cai MC, Zhao SN, Cidanpingcuo Tu YQ, Wu SF, Yao YG, Bandelt HJ, Zhang YP. Mitochondrial genome evidence reveals successful Late Paleolithic settlement on the Tibetan Plateau. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 21230–21235, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhuang J, Droma T, Sun S, Janes C, McCullough RE, McCullough RG, Cymerman A, Huang SY, Reeves JT, Moore LG. Hypoxic ventilatory responsiveness in Tibetan compared with Han residents of 3,658 m. J Appl Physiol 74: 303–311, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]