Abstract

Ventilatory insufficiency remains the leading cause of death and late stage morbidity in Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). To address critical gaps in our knowledge of the pathobiology of respiratory functional decline, we used an integrative approach to study respiratory mechanics in a translational model of DMD. In studies of individual dogs with the Golden Retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) mutation, we found evidence of rapidly progressive loss of ventilatory capacity in association with dramatic morphometric remodeling of the diaphragm. Within the first year of life, the mechanics of breathing at rest, and especially during pharmacological stimulation of respiratory control pathways in the carotid bodies, shift such that the primary role of the diaphragm becomes the passive elastic storage of energy transferred from abdominal wall muscles, thereby permitting the expiratory musculature to share in the generation of inspiratory pressure and flow. In the diaphragm, this physiological shift is associated with the loss of sarcomeres in series (∼60%) and an increase in muscle stiffness (∼900%) compared with those of the nondystrophic diaphragm, as studied during perfusion ex vivo. In addition to providing much needed endpoint measures for assessing the efficacy of therapeutics, we expect these findings to be a starting point for a more precise understanding of respiratory failure in DMD.

Keywords: respiratory mechanics, dystrophin, animal models, diaphragm, muscular dystrophy

duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe, childhood-onset muscle wasting disease with an approximate incidence of 1 in 3,500 boys caused by mutations in the X-linked dystrophin gene (28). As with less common childhood-onset muscular dystrophies, progressive weakness in muscles of locomotion dominates the clinical course to loss of ambulation, but the leading cause of late-stage morbidity and mortality is progressive failure of the respiratory pump (4, 21, 25). Patient-oriented studies have defined the rate of decline in standardized indices from pulmonary function tests (4, 21, 27), and studies in mdx mice have provided mechanistic information about some of the molecular and cellular correlates of muscle degeneration (9, 42). However, a reliable model of the effect of dystrophin's absence on respiratory mechanics and loss of ventilatory capacity has been elusive. Whereas the diaphragm of the mdx mouse is its most severely affected muscle, studies of respiratory mechanics have been limited to whole-body plethysmography, limiting the extent to which the contribution of different respiratory muscle groups can be determined (29, 30). Therefore, there is a compelling need for a model of respiratory mechanics in DMD to improve our understanding of the disease process in man, and to provide a platform for therapeutic development. Golden Retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) is an important translational model of DMD that exhibits the major hallmarks of the human disease on a greatly accelerated time scale (33, 47), but its potential as a model of respiratory pathobiology in DMD has not been fully exploited.

To address these needs, we applied both novel and classical experimental approaches to assess the age-related loss of ventilatory capacity in GRMD and the accompanying changes in respiratory mechanics. In DMD, exertional increase in metabolic rate is limited by global weakness of the muscles of locomotion, rendering the progressive decline of ventilatory capacity early in DMD clinically silent (4). Consequently, assessment of respiratory mechanics at higher ventilatory rates has been challenging. In a canine model, we used doxapram to exploit the pharmacodynamics of direct channel activation in the sensory afferents controlling respiratory drive, thereby dissociating respiratory mechanics from metabolic loading. This allowed us to test hypotheses related to changes in the mechanics of tidal breathing in the setting of elevated respiratory drive in relatively young dogs with the GRMD mutation and with no overt clinical signs of ventilatory insufficiency.

In DMD, the diaphragm is affected earlier and more severely than other skeletal muscles. This is possibly due to heavy use as the primary driver of ventilation at rest. We used esophageal and gastric balloon manometry to test the hypothesis that doxapram stimulation would uncover deficits in transdiaphragmatic pressure (Pdi) caused by loss of diaphragm contractile capacity in GRMD during tidal breathing.

The two-compartment chest wall model of respiration first established by Konno and Mead allows for the relative contribution of opposing inspiratory muscles to be estimated noninvasively by comparing volume changes in the abdomen (VAB) and rib cage (VRC) approximated by respiratory inductance plethysmography (RIP) (11, 31). Because positive change in VAB during inspiration is caused largely by the shortening and caudal motion of the diaphragm, the diaphragm's contribution to inspiration can be estimated by measuring ΔVAB expressed as a percentage of total tidal volume (Vt) during normal breathing. In DMD, clinical studies suggest that the diaphragm's contribution to inspiration at rest progressively diminishes during the first two decades of life, with ΔVAB reduced from ∼70% to ∼30% by the onset of nocturnal oxygen desaturation (37, 44). In very advanced DMD, severe diaphragm weakness sometimes results in abdominal paradox: cranial diaphragm motion during inspiration as negative chest wall pressure developed by the intercostal and auxiliary muscles overwhelms the diaphragm (11, 23, 39). We hypothesized that a similar shift in VRC/VAB partitioning would be observed in GRMD at rest, that loss of abdominal volumetric contribution would limit increases in Vt under stimulated conditions, and that stimulated metabolic loading would uncover abdominal paradox absent at rest in dogs with no clinical signs of ventilatory insufficiency.

Simultaneous recording of compartmental volumes and pressures can be used to assess the contribution of nondiaphragm inspiratory and expiratory muscles. We predicted that during periods of stimulated respiratory drive, dogs with the GRMD mutation would rely more heavily on inspiratory and expiratory intercostal and abdominal muscles than normal dogs to achieve similar rates of ventilation.

Dystrophin-deficient muscles undergo progressive changes in passive as well as active properties (49), and radiographic and NMR studies have reported thickening of the GRMD diaphragm (7, 51). We tested the hypothesis that changes to the morphometry of the GRMD diaphragm itself, in particular the presence of additional interstitial collagen resulting from fibrosis, would affect the muscle's passive mechanical properties, potentially impacting overall respiratory mechanics at rest and under load. To test this, we developed and utilized a novel system for oxygenated perfusion of the isolated hemidiaphragm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

This study included 34 dogs with the GRMD mutation; 4 dystrophin-expressing GRMD-carrier dogs; and 17 unaffected, normal dogs, either from the GRMD breeding colony or mongrel, ranging from 4 to 18 mo of age. Seven dogs with the GRMD mutation and five normal control dogs were included in doxapram studies under anesthesia at the time of euthanasia. All animals used in this study were cared for and used humanely in accordance with the requirements specified by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Pennsylvania, the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, and Wake Forest University, and in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (revised 1996; National Research Council, Washington, DC). RIP studies of awake dogs were conducted at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, and Wake Forest University. All doxapram studies were conducted at the University of Pennsylvania. Although all dogs were a part of other research projects, no intervention was expected to affect parameters assessed in the present study.

Respiratory inductance plethysmography.

RIP traces were generated by inductance bands embedded in the Lifeshirt jacketed telemetry system (Vivometrics) and analyzed using Vivologic software (Vivometrics). Shirts from a range of sizes were fitted to dogs with the primary aim being proper location of rib cage (RC) and abdominal (AB) inductance bands. The RC band was located at the level of the fourth rib, and the AB band just caudal to the rib cage. Measurements of awake and anesthetized dogs were made in the laterally recumbent posture. The standard method of calibrating RIP traces involves performing an isovolume maneuver to establish the relative contribution of RC and AB signals to Vt (31). Because this method is inapplicable to dogs, we used the quantitative diagnostic calibration (QDC) technique first described by Sackner et al. for use in humans, and subsequently applied to dogs (41, 42, 45). QDC compares standard deviations of raw RC and AB signals collected over ∼5 min of regular, quiet breathing to calculate a proportionality constant, K, which relates the relative contributions of those signals to Vt. Subsequently, Vt as measured by spirometry over the same period, is used to calculate the scaling factor, M, which scales the proportionally calibrated sum of RC and AB signals to real Vt. Our calibration procedures differed slightly between dogs studied during wakeful breathing and those included in the anesthetized doxapram study. In awake dogs, when we were interested in the proportional contribution of AB and RC compartments, we calculated K alone without spirometry. These animals were fitted with the Lifeshirt as described above, placed in lateral recumbency, and allowed to breath quietly for ∼5 min. QDC calibration was performed on RC and AB traces from this period. For the doxapram study, dogs were intubated and anesthetized (2% isoflurane), and placed in lateral recumbency before performing the QDC calibration as described above. In addition, we calculated the scaling factor, M, to establish approximate, RIP-derived values for Vt, VAB, and VRC by using spirometry data from a Datex Omeida anesthesia machine, which integrates signals from syringe-calibrated flow sensors to determine Vt.

We measured respiratory phase angle from RIP tracing as an index of abdominal paradox. Phase angle is a measure of the degree to which RC and AB movements are synchronized during tidal breathing. A phase angle of zero indicates fully synchronous motion, whereas 180° indicates a state in which RC and AB are exactly asynchronous. Values from 1° to 180° reflect AB lagging behind RC by a proportional amount of the breathing cycle. Vivologic software calculates phase angle on a breath-by-breath basis as described (3). We averaged breath-by-breath phase angle measurements over approximately 30-s periods of regular quiet breathing or, in the case of doxapram, 30 s beginning at peak Vt following doxapram administration.

Pressures.

Gastric pressure (Pgas) and esophageal pressure (Pes) were measured as described (40) using balloons constructed from an intraaortic balloon pump coronary perfusion support system (Fideltity; Datascope). These polyethylene balloons have the advantage of being mounted on long, flexible cannulae. The balloon material is inelastic, and therefore does not contribute to Pgas or Pes as a result of any inherent recoil. The balloons were connected to calibrated TSD104A pressure transducers (Biopac Systems), the output digitized at 500 Hz with an MP150c data acquisition system (Biopac Systems), and analyzed using AcqKnowledge software (Biopac Systems). Interbreath pressures were set to zero during restful breathing. Transdiaphragmatic pressure (Pdi) was calculated by subtracting Pes from Pgas.

Anesthesia and doxapram studies.

Dogs were induced with dexmedetomidine hydrochloride (375 μg/m2) (Pfizer Animal Health) before being masked down with isoflurane (Baxter Healthcare), intubated, and maintained at 2% isoflurane continuously throughout the study in a laterally recumbent position. Gastric and esophageal balloon catheters were placed, and the Lifeshirt jacket was fitted to the dog as described above. Doxapram hydrochloride (Baxter Healthcare) bolus was administered via the saphenous vein at 1 mg/kg, followed by a second dose of 2 mg/kg 5 min later.

Histology.

The length of the costal muscular diaphragm was measured in vivo at three standardized places through an incision in the abdominal wall at necropsy. To determine sarcomere length at these dimensions, strips were clamped with two-headed biopsy forceps, excised, and fixed in 10% formalin. Diaphragm thickness was measured once at this point. Fixed tissue blocks were sectioned longitudinally, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (Fisher Scientific) as described (6), and imaged at 20×. Sarcomere length was determined by measuring the length of 10 sarcomeres by eyepiece micrometer and dividing by 10. In addition, diaphragm, external and internal intercostal, abdominal wall, and cranial tibialis muscle blocks were excised and frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane. These were later thawed and fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h prior to paraffin embedding and sectioning at 7 μm. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or picrosirius red (Sigma-Aldrich) and imaged at 20× in brightfield. Images were analyzed for collagen cross-sectional area using Image Pro 7. Image files were converted from the RGB (red, green, blue) color model to the YIQ (in-phase/quadrature) color model. Channel Y (luminance) was extracted from the YIQ image. The extracted Y channel is an 8-bit, gray-scale image. Image segmentation was histogram-based; double-threshold intensity ranges were set as follows: contractile apparatus, 0–140; collagen, 140–205. Data were exported to Microsoft Excel for further analysis. Investigators were blinded to genotype and muscle origin for each slide, and collagen cross-sectional area (CSA) was quantified for each by averaging three 500-μm2, nonoverlapping images.

Ex vivo diaphragm mechanics.

A section of costal hemidiaphragm was removed at the time of euthanasia and rapidly cooled on ice. The internal thoracic artery was cannulated, and the muscle was perfused with perfusate warmed to 37°C. Perfusate was a modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing, in mmol/l: CaCl2, 1.5; glucose, 5.5; KCl, 4.7; MgSO4, 1.66; NaCl, 118.0; NaH2PO4, 1.18; NaHCO3, 24.88; and Na-pyruvate, 2.0 in H2O, to which was added 20% heparinized whole blood. The perfusate was oxygenated and warmed by means of an Apex cardiopulmonary bypass membrane oxygenator (Cobe Cardiovascular) fed with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The oxygenator's integral heat exchanger was warmed by a water bath (Haake A 28F/SC 100; Thermo Fisher) to maintain perfusate at 37°C. After warming for 10 min, a strip roughly 1 cm wide was cut in the muscular diaphragm parallel to the direction of shortening and left attached to the rib at the costal margin. The central-tendon end of the strip was fixed to the arm of a calibrated 305C-LR muscle lever (Aurora Scientific), and the rib was solidly fixed in place. Unipolar electrodes (Biopac Systems) connected to a model S88 stimulator (Grass Technologies) were used to elicit twitch and tetanus contractions to establish viability and L0 as described (41). Sets of five lissajous loops were performed at 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 Hz. Length and force were sampled at 500 Hz using an MP150 data acquisition system (Biopac Systems) and analyzed in AcqKnowledge software (Biopac Systems).

Statistics.

All data in figures are presented as means ± SD. Significance between groups was tested with paired or unpaired Student's t-test as appropriate; P ≤ 0.05 is considered significant and is denoted with an asterisk.

RESULTS

Diaphragms in animals with the GRMD mutation are dysfunctional during quiet breathing.

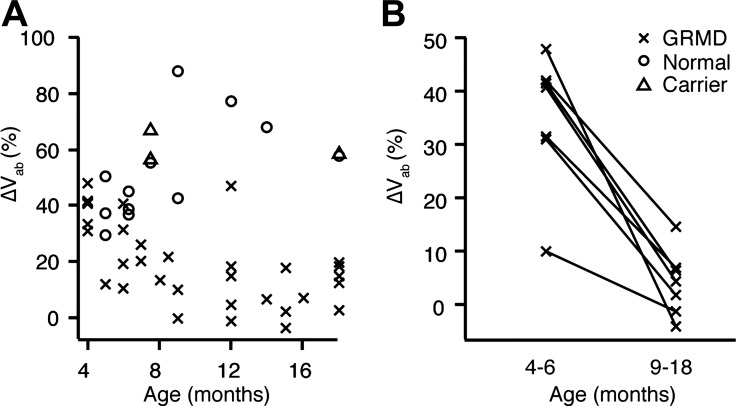

We used RIP to measure ΔVAB in 22 dogs with the GRMD mutation, 12 normal dogs, and 3 dogs that were dystrophin-expressing GRMD carriers that were laterally recumbent, during periods of wakeful, quiet breathing. Dogs with the GRMD mutation showed reduced ΔVAB compared with normal and carrier dogs (20.2 ± 15.8% vs. 54.2 ± 16.3%; P < 0.01) indicating reduced diaphragm range of motion and contribution to inspired volume. The difference was larger in older dogs (Fig. 1A). Seven dogs with the GRMD mutation from this group were studied at two time points, and all showed an age-related decline in ΔVAB (Fig. 1B) at rest. Although normal dogs were not measured at multiple time points, no normal (or carrier) dog over 1 year of age showed a ΔVAB of less than 60%.

Fig. 1.

A: cross-sectional study of diaphragmatic contribution to breathing (ΔVAB) at rest in 22 dogs with the GRMD mutation (x), 3 dystrophin-expressing carrier dogs (Δ), and 12 normal dogs (o) shows a loss of diaphragm function in GRMD. B: decline in ΔVAB at rest in seven individual dogs with the GRMD mutation measured at two time points.

Pdi in dogs with the GRMD mutation is reduced at rest and during direct stimulation of respiratory drive.

To address whether doxapram would uncover deficits in Pdi caused by loss of diaphragm contractile capacity in GRMD we used balloon manometry to trace Pdi throughout the hyperventilatory response to doxapram bolus injection. In anesthetized and instrumented dogs with the GRMD mutation (n = 7) and normal (n = 5) dogs, we administered doxapram intravenously to temporarily stimulate an abrupt increase in ventilation while monitoring respiratory performance. Table 1 shows ages, weights, and basic respiratory parameters of dogs included in the doxapram study. End-inspiratory Pdi in dogs with the GRMD mutation was lower than in normal dogs at rest (5.45 ± 2.39 mmHg vs. 7.8 ± 1.11 mmHg; P < 0.05) and at the peak effect following 1 mg/kg doxapram (10.44 ± 4.4 mmHg vs. 16.26 ± 2.92 mmHg; P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Major ventilatory parameters of 7 dogs with the GRMD mutation and 5 normal control dogs included in the doxapram study

| Animal ID | Dystrophin, ± | Age, months | Weight, kg | Ventilation, ml·kg−1·min−1 (baseline) | Ventilation, ml·kg−1·min−1 (1 mg/kg doxapram) | Tidal volume, ml/kg (baseline) | Tidal volume, ml/kg (1 mg/kg doxapram) | Respiratory rate, breaths/min (baseline) | Respiratory rate, breaths/min (1 mg/kg doxapram) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g892 | − | 10 | 16.6 | 17.5 | 246.5 | 3.5 | 12.1 | 5 | 25 |

| g092 | − | 13 | 13 | 142 | 375.3 | 10.9 | 22.1 | 13 | 17 |

| g124 | − | 6 | 9.8 | 58.2 | 189.8 | 5.8 | 9.7 | 10 | 20 |

| g547 | − | 17 | 17.3 | 57.5 | 372.3 | 8.2 | 18.6 | 7 | 23 |

| g033 | − | 16 | 19.3 | 116.5 | 408 | 9 | 17.3 | 13 | 25 |

| g566 | − | 16 | 13.8 | 38.8 | 333.8 | 7.8 | 19.6 | 5 | 17 |

| g890 | − | 17 | 20 | 90.8 | 308.1 | 5.7 | 10.6 | 16 | 29 |

| n290 | + | 7 | 21.5 | 109.8 | 304.4 | 11 | 23.3 | 10 | 16 |

| n559 | + | 7 | 20.3 | 83.1 | 463.3 | 13.8 | 31.3 | 6 | 15 |

| n530 | + | 9 | 23 | 82.8 | 346.4 | 10.3 | 22.6 | 8 | 16 |

| n256 | + | 13 | 27.8 | 135.1 | 330.9 | 11.3 | 21.6 | 12 | 19 |

| n016 | + | 7 | 20 | 115 | 576.3 | 10.5 | 24 | 10 | 25 |

Dogs with the GRMD mutation lose volumetric reserve during direct stimulation of respiratory drive.

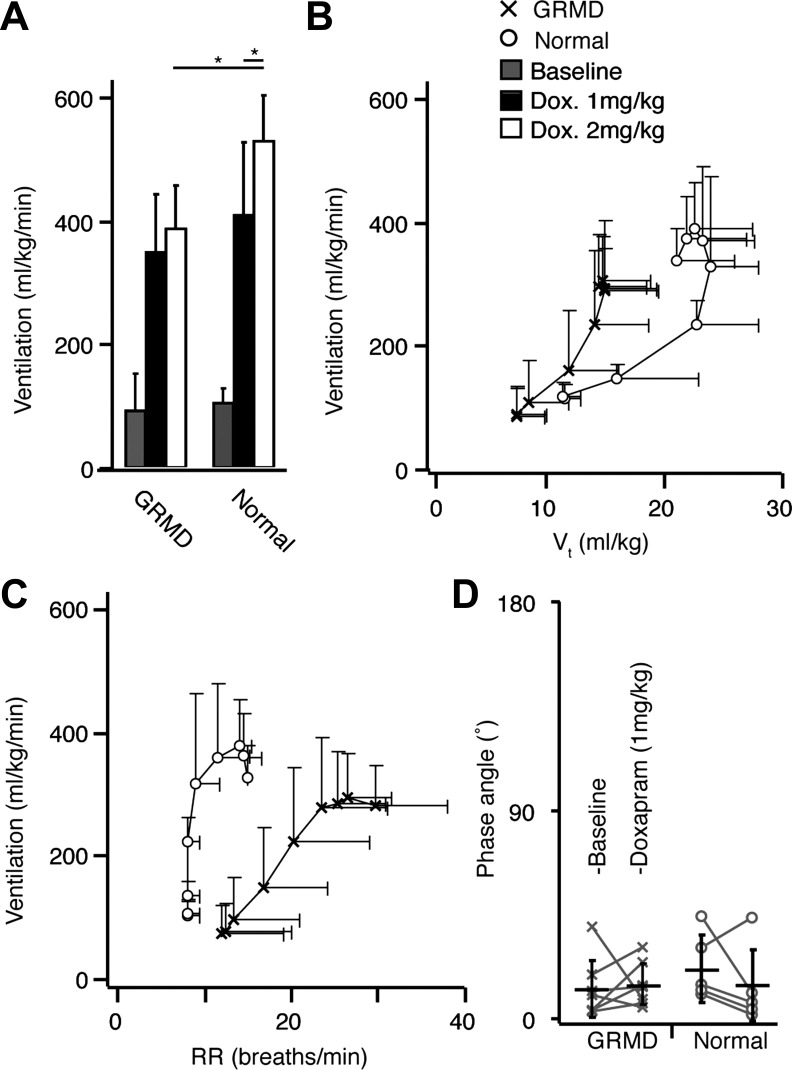

We were interested in whether the measured loss of diaphragmatic contribution to Vt at rest would result in Vt limitation during periods of respiratory drive. After an initial dose (1 mg/kg) of doxapram, dogs with the GRMD mutation and normal dogs reached similar peak rates of ventilation (GRMD, 343.9 ± 90.6 ml·kg−1·min−1; normal, 403.8 ± 113.9 ml·kg−1·min−1) and relative reductions in end-tidal CO2 (GRMD, 26.7 ± 6.3%; normal, 29.4 ± 6.8%) within 2 min of the doxapram bolus, before returning to near-baseline rates of ventilation by 5 min postbolus. A subsequent higher dose (2 mg/kg) further increased ventilation in normal dogs but not in dogs with the GRMD mutation (Fig. 2A), indicating a loss of ventilatory capacity in the GRMD animals. In both cases and in both groups, dogs responded to the onset of doxapram first by increasing Vt, then respiratory rate in a manner consistent with graded exercise, as shown by the typical J shape in Fig. 2B. However, at equal rates of ventilation, Vt was consistently lower in the dogs with the GRMD mutation, which compensated with higher respiratory rates (Fig. 2B). Neither anesthesia nor doxapram had an appreciable effect on ΔVAB in individual dogs from either group (data not shown). At rest and at peak ventilation following doxapram administration (1 mg/kg), we observed no difference in phase angle between dogs with the GRMD mutation and normal dogs, indicating an absence of abdominal paradox (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

A: maximum ventilation achieved in response to intravenous doxapram administration under anesthesia in seven dogs with the GRMD mutation and five normal dogs. Although both groups responded equally to the initial doxapram dose (1 mg/kg), dogs with the GRMD mutation failed to further increase maximum ventilation after a second, higher dose (2 mg/kg). B and C: ventilation-Vt and ventilation-RR relationships after doxapram bolus (1 mg/kg) in seven dogs with the GRMD mutation (x) and five normal (o) dogs. Points along curves are at 10-s intervals following bolus from lower left to upper right. Dogs with the GRMD mutation employed higher respiratory rates earlier to achieve equivalent increases in ventilation. D: respiratory phase angle was not different between groups before or during maximal doxapram-mediated ventilation.

Expiratory muscles compensate for diaphragm dysfunction in GRMD.

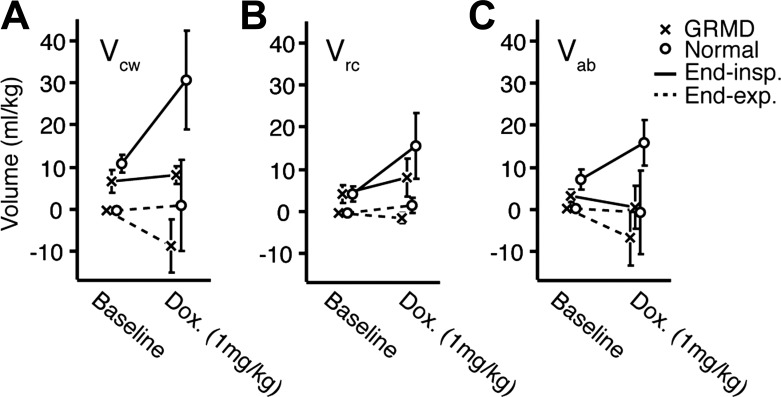

DMD is associated with reduced functional residual capacity (FRC). We were interested in whether loss of volumetric reserve observed in GRMD would be accompanied by abnormal end-inspiratory chest wall volume (EIVcw) and end-expiratory chest wall volume (EEVcw). Figure 3 shows relative maximum EIVcw and minimum EEVcw by compartment in dogs with GRMD and normal dogs before and after a doxapram bolus (1 mg/kg). We found that the increases in Vt that dogs with the GRMD mutation achieved were almost entirely the result of lowered EEVcw and not increased EIVcw (Fig. 3A). In contrast, normal dogs achieved larger increases in Vt primarily by tapping into inspiratory reserve. Furthermore, RIP allowed us to differentiate between changes in rib cage and abdominal contributions to these volumes. The reduction in EEVcw observed in dogs with the GRMD mutation upon doxapram administration was primarily caused by lower end-expiratory VAB rather than VRC, indicating increased cranial motion of the diaphragm at end-expiration (Fig. 3, B and C).

Fig. 3.

Volumetric reserve. A: chest wall volume (Vcw) changes in response to doxapram (1 mg/kg) as measured by respiratory inductance plethysmography in seven dogs with the GRMD mutation (x) and five normal (o) dogs. Difference between end-inspiratory volume (EIV) (solid lines) and end-expiratory volume (EEV) (dashed lines) Vcw is equivalent to total tidal volume (Vt). EEV during quiet breathing (baseline) is set to zero. Doxapram (1 mg/kg) elicits very different increases in Vt; by means of increased EIVcw in normal dogs, and decreased EEVcw in dogs with the GRMD mutation. B and C: doxapram-mediated changes in Vcw by compartment: rib cage (VRC) and abdomen (VAB). Reduced EEVcw after doxapram in GRMD is primarily due to cranial displacement of the diaphragm throughout the breathing cycle as shown by reduction of abdominal end-inspiratory and end-expiratory volumes.

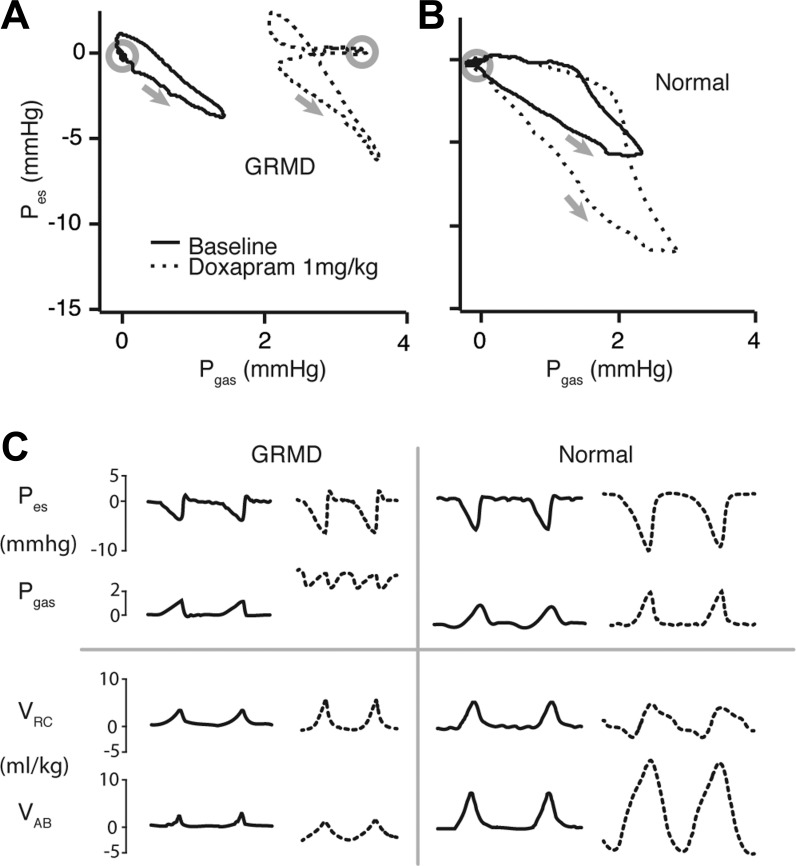

If abdominal expiratory muscles drive VAB and chest wall volume below its equilibrium point during expiration, we would expect to observe a consequent increase in abdominal pressure (Pgas) (18, 27). Therefore, we performed a detailed analysis of gastric and esophageal pressures (Pgas and Pes, respectively) before and after doxapram administration. Indeed, dogs with the GRMD mutation demonstrated a pattern of transient increases in Pgas over two time scales following the initial dose of doxapram (1 mg/kg) (Fig. 4). The first was repeated each breath at end-expiration, observed as a rightward spike in Pes/Pgas loops. The second was a longer-term increase occurring over several breaths during peak doxapram effect, observed as a rightward shift of the entire loop. The end-expiratory Pgas spike emerged only at the higher dose in normal dogs, and then to a lesser degree than in dogs with the GRMD mutation, whereas there was no long-term increase in Pgas after either dose in normal dogs.

Fig. 4.

A and B: representative traces of esophageal vs. gastric pressure throughout the breathing cycle before and at peak doxapram (1 mg/kg) effect in a dog with the GRMD mutation and a normal dog. Gray arrows indicate direction of loop. Gray circles indicate end-expiration. Dogs with the GRMD mutation showed transient increases in gastric pressure (Pgas) throughout the breathing cycle consistent with a postexpiratory recoil (PER) breathing strategy. C: representative synchronized traces of pressures and compartmental volumes in the time domain during two complete breathing cycles before and at peak doxapram (1 mg/kg) effect in a dog with the GRMD mutation and a normal dog.

Remodeling increases the passive stiffness of the GRMD diaphragm.

We examined the gross morphometry, histopathology, and passive viscoelastic properties of the GRMD diaphragm. When measured at equal sarcomere lengths, the muscular diaphragms of dogs with the GRMD mutation were shorter in the direction of contraction compared with normal dogs (31.7 ± 7.2 mm vs. 75.6 ± 15.6 mm; P < 0.01) and thicker in the orthogonal plane (8.06 ± 3.4 mm vs. 2.4 ± 0.4 mm; P < 0.01). These findings indicate a process of remodeling that involves the deletion of sarcomeres rather than hypercontraction (Fig. 5). Based on histological staining for interstitial collagen, the amount of diaphragmatic CSA attributable to interstitial collagen (46.6% ± 5.6%) was significantly greater than that of other respiratory or locomotory muscles (Fig. 6). To address the physiological correlates of this remodeling process we developed an isolated, perfused muscle preparation to allow direct comparison of passive tension from GRMD and dystrophin-expressing carrier diaphragms subjected to cyclical length changes ex vivo (49). Although the aorta has been used with success to perfuse the canine diaphragm for potential transplantation (34), we found that the collateral connections between the internal thoracic and intercostal arteries afforded adequate delivery of oxygen to a large volume of tissue (Fig. 7A) (5). These studies showed that the specific passive stiffness of the GRMD diaphragm strip was much higher and invariant at all physiologically relevant cyclical shortening rates than in a dystrophin-expressing carrier diaphragm at muscle lengths above 100% of L0 (Fig. 7B). The dynamic elastic modulus between 100% and 107% of L0 was 21.4 g/mm2 in dogs with the GRMD mutation vs. 2.4 g/mm2 in a carrier dog.

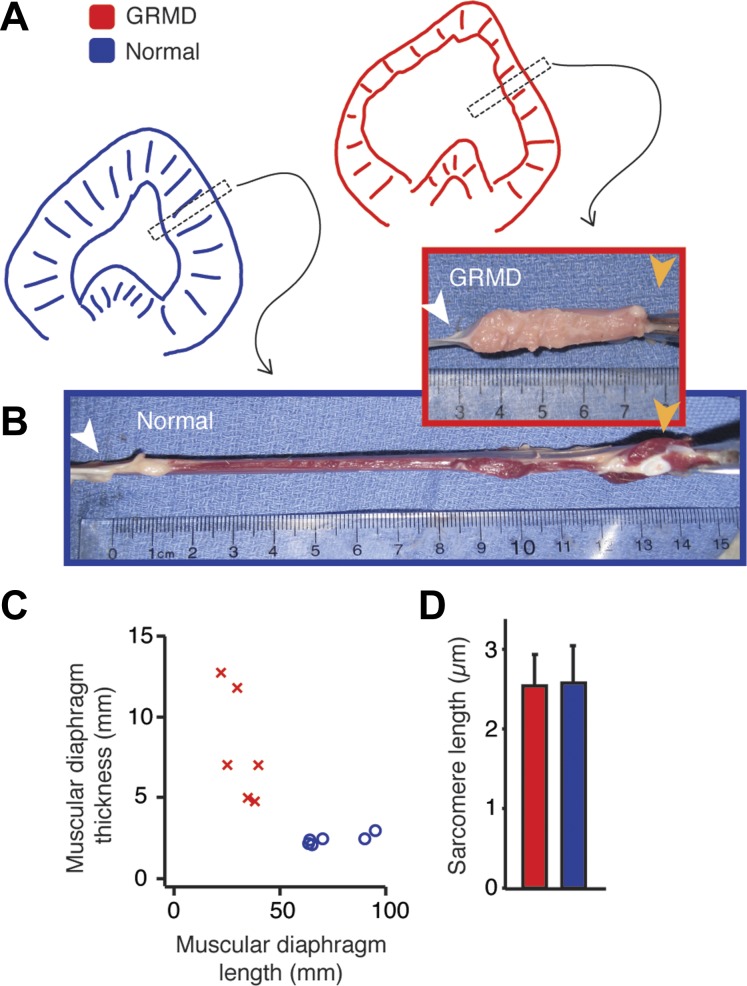

Fig. 5.

The GRMD diaphragm undergoes a dramatic remodeling that alters passive properties of the muscle. A: schematic cranial view of typical diaphragms from 1-year-old dogs viewed cranially (GRMD, red; normal, blue) showing reduced muscular length in the direction of shortening and expansion of central tendon area in GRMD. B: representative photographs of longitudinal sections of costal diaphragm (location indicated in A) showing reduced muscle length and increased thickness in GRMD. White arrowheads indicate central tendon, orange arrowheads indicate insertion on rib. C: plot of muscular diaphragm length vs. thickness in six dogs with the GRMD mutation and five normal dogs. D: sarcomere length at these muscle lengths do not differ between dogs with the GRMD mutation and normal dogs, indicating that the reduced diaphragm length in GRMD results from removal of sarcomeres in series.

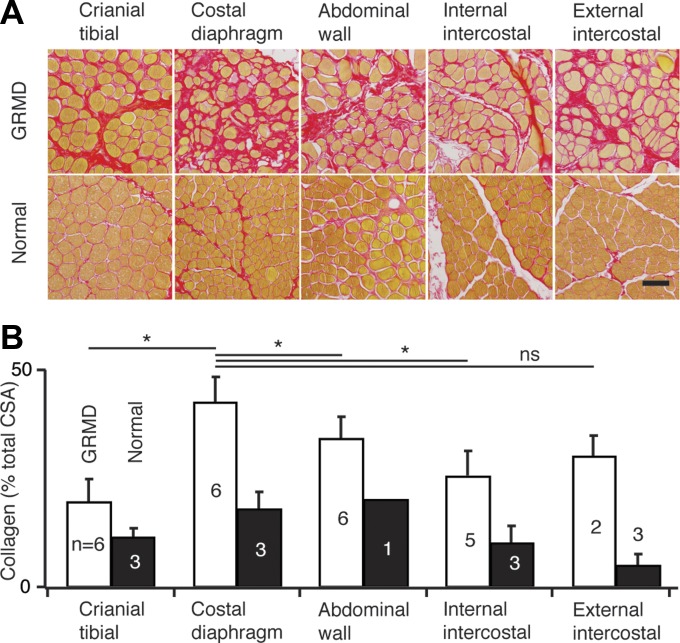

Fig. 6.

A: representative photomicrographs of muscle sections stained with picrosirius red from one dog with the GRMD mutation and one normal dog. Scale bar = 100 μm. Collagen (stained red) is increased in GRMD. B: collagen cross-sectional area (CSA) quantified in muscle sections stained with picrosirius red from dogs with the GRMD mutation and normal dogs. The number of dogs in each group is indicated in white. GRMD diaphragms had significantly higher collagen CSA than other GRMD muscles.

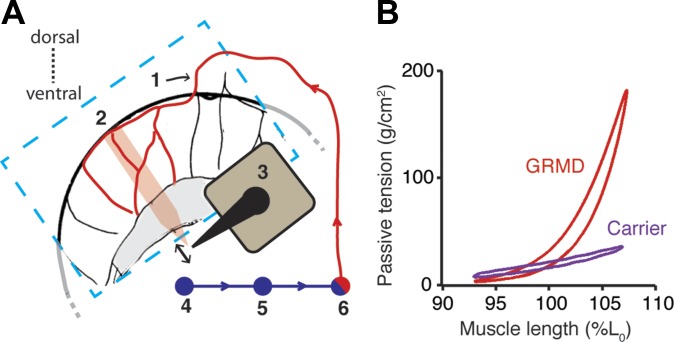

Fig. 7.

Perfusion via the interior thoracic artery enables study of ex vivo diaphragm mechanics. A: schematic of a region of the costal diaphragm viewed cranially [see refs. (5, 34)]. A section of costal diaphragm is removed (region outlined in light blue) and the interior thoracic artery is cannulated (1) and perfused with a mixture of modified Krebs-Hanselite and heparinized whole blood at 37°C. A wide strip (∼1 cm) of costal diaphragm is excised (pink shaded area) but left attached at the rib (2), whereas the central tendon end is attached to a muscle ergometer (3). Perfusate is collected and pumped (4) through a heat exchanger (5) and membrane oxygenator (6) before being reperfused. B: lissajous loops of specific passive tension vs. length in viable, perfused ex vivo diaphragm muscle strips from a dog with the GRMD mutation and a dystrophin-expressing carrier dog showing increased stiffness at lengths over 100% of L0 in GRMD.

DISCUSSION

In this study we combined noninvasive, invasive, ex vivo, and histological approaches to improve our understanding of the mechanics of breathing during the progressive loss of ventilatory capacity in a translational model of DMD. Our data indicate that respiratory decline in dogs with the GRMD mutation is accompanied by changes in passive and active properties of the respiratory pump. In both DMD and GRMD, widespread muscle disease severely limits the loading of the respiratory system by way of an exercise-induced increase in metabolic demand. To circumvent this limitation and to simulate the effects of moderate exercise, we uncoupled these processes using the respiratory stimulant doxapram (13, 14).

Normally, increasing demand for ventilation through exercise results in a progressive and sequential recruitment of additional inspiratory and expiratory contractile reserve that follows a well characterized pattern. In graded exercise, increased respiratory drive caused by metabolic loading leads first to the recruitment of additional diaphragmatic motor units, followed by intercostal and auxiliary muscles to increase Vt, followed in turn by an increase in respiratory rate (1). Ultimately, at high rates of exercise, expiratory muscles are recruited to shorten breathing cycle time, and to drive EEVcw below the chest wall's elastic equilibrium point, thus accessing expiratory reserve volume and further increasing Vt. Doxapram's putative mode of action, as well as its independence from anesthetic concentration, suggested that the complex neural circuitry underlying the respiratory muscle recruitment sequence would remain intact (13, 14). Indeed, our observations show that both normal dogs and those with the GRMD mutation followed this pattern.

The impairment of ability to increase Vt meant that dogs with the GRMD mutation required higher respiratory rates and earlier expiratory muscle recruitment to achieve similar ventilatory rates as normal dogs after administration of doxapram. Dogs with the GRMD mutation also failed to further increase ventilation after a subsequent higher dose. Together, these findings indicate that ventilatory capacity is severely compromised in dogs with the GRMD mutation by approximately 1 year of age. Furthermore, although a dog with the GRMD mutation loses ventilatory capacity, a combination of remodeling of the diaphragm and alteration of the timing of accessory muscle recruitment partially compensate for this loss by enabling the expiratory muscles of the abdomen to aid inspiration.

The observation that doxapram reduces EEVAB together with increased end-expiratory Pgas in GRMD is consistent with the compensatory adoption of a respiratory muscle recruitment sequence, termed postexpiratory recoil (PER), which normally emerges only during heavy exercise or under pathological conditions such as diaphragm paralysis. Grimby et al. first showed, in healthy subjects during a period of heavy exercise, that contraction of abdominal wall muscles at end-expiration functions not only to increase expiratory flow and Vt, but also to store elastic and gravitational energy in the diaphragm for the next breath (26, 19, 35). PER appears to be further augmented in dogs with the GRMD mutation because the entire range over which the diaphragm moves is shifted cranially under increased respiratory drive, likely increasing passive energy storage in the diaphragm's elastic elements.

Recruitment of the expiratory musculature in GRMD is further facilitated by a remodeling of the diaphragm, which affects the passive mechanical properties of the muscle. Although the GRMD diaphragm becomes weaker, as evidenced by reduced Pdi, it also becomes shorter, thicker, and severely fibrotic, with a resulting increase in passive resistance to distension at three levels. First, series deletion of sarcomeres alone increases passive stiffness as individual sarcomeres are stretched further for a given absolute muscle length change. Second, increased collagen in the extracellular matrix increases muscle length-specific and CSA-specific stiffness. Finally, the increase in muscle length-specific stiffness is further multiplied by the increase in overall CSA of the thickened muscle. It should be noted that due to animal availability, passive stiffness in the GRMD diaphragm was compared with that from a heterozygous carrier animal. Although carrier diaphragms appeared grossly normal, and respiratory disease has not been reported in human or canine carriers, further comparisons to normal diaphragms are needed. Regardless, the reliance on PER combined with the absence of abdominal paradox observed in this study suggests a possible compensatory role for a stiff diaphragm.

Two clinical examples lend support to this interpretation. Abdominal paradox resulting from a weak or nonfunctional but compliant diaphragm is an energetically and volumetrically unfavorable scenario for gas exchange (53). An example of severe abdominal paradox in the clinic is acute diaphragmatic paralysis following iatrogenic phrenic nerve injury during cardiac surgery. Surgical therapy for refractory cases involves plication (reduction of the area and excursion of the nonfunctional diaphragm), which serves to eliminate abdominal paradox, increase maximum lung volumes, and reduce the work of breathing for a given Vt (16, 22, 46, 50). In other words, it is better by these important metrics to have a short and therefore stiff diaphragm with little or no range of motion, than a compliant but weak or nonfunctioning diaphragm.

Second, dogs with the GRMD mutation are not a unique example of compensatory PER in the setting of diaphragm sarcomere deletion. Hyperinflation of the lungs and increased FRC in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease leads to a remodeling of diaphragmatic muscle fibers, whereby sarcomeres are deleted in series in such a way that ideal resting sarcomere length is maintained in the shortened muscle (10). This allows Pdi to be more effectively generated around a higher chest wall equilibrium volume and enables compensatory PER breathing (10, 19, 35). Patients with DMD (and dogs with the GRMD mutation in this study) breathe at a lower than normal FRC (38), suggesting that the stimulus and mechanism for diaphragm remodeling are likely different.

There are important caveats in ascribing a compensatory role to the observed diaphragm remodeling in GRMD. Abdominal paradox is typically observed in scenarios of diaphragm dysfunction where other respiratory muscles are normal. Because abdominal paradox requires inspiratory intercostal muscles to be strong enough to overpower a weak diaphragm and all respiratory muscles are affected in GRMD, the absence of abdominal paradox could be a function of insufficient intercostal strength. A similar argument could be made against PER, because clinical examples typically involve normal abdominal muscles. We view changes to the mechanics of breathing in GRMD not so much as compensation for a failing diaphragm per se, but as a redistribution of the work of breathing to a larger volume of muscle, thus minimizing peak force on any individual sarcomere. In this context, the augmentation of diaphragmatic elastance could play an important role by further enabling the muscles of the abdomen to contribute to inspiration. This interpretation recalls the significance of the Gowers' sign in the clinical assessment of locomotive muscle performance in DMD (8, 23). Gower first observed that when asked to stand from a seated position without the aid of elevated structures, children with body-wide neuromuscular disease follow a stereotyped sequence of motions, the effect of which is to spread the work of standing among as many muscles as possible. Although the combined effect of diaphragm remodeling in GRMD appears to be beneficial, further study is needed to determine processes underlying the observed changes, and whether any component of diaphragm stiffness is maladaptive.

There is indirect evidence that a similar process of remodeling and compensatory recruitment of the respiratory musculature takes place in DMD, but there has been no previous opportunity to integrate the individual components as facilitated in this translational model. One study reported sonographically detectable thickening of the muscular diaphragm in boys with DMD (17), and progressive loss of diaphragm range-of-motion beginning early in the disease without abdominal paradox has been reported in DMD (30, 35). And, although boys with DMD breathe at a lower FRC, PER has not been reported. The interpretation of adaptive diaphragm function put forward here attributes a possible positive functional role to fibrosis, a process usually considered pathologic. Therefore, these findings could be relevant to therapies that target this process. Moreover, the diaphragm has an essential role in anatomical partition, which might be compromised by necrotizing myocytolysis in the absence of fibrosis, leading to a high incidence of additional morbidity from transdiaphragmatic herniation of abdominal viscera (7, 12).

The observation that dogs with the GRMD mutation recruit a broader range of respiratory muscles than normal control dogs to achieve the same rates of ventilation suggests that the lack of a doxapram dose-response in this population reflects a functional limitation of the respiratory pump. We cannot, however, rule out the possibility that dystrophin expression in the central nervous system (CNS) directly affects neuronal pathways involved in the integration of afferent and efferent signals responsive to doxapram-receptor binding. Although the functions of dystrophin and the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex in the CNS are not well understood, cognitive impairment has been identified in some patients with DMD, and progress has been made in identifying potential biochemical pathways that might be implicated (2, 15, 52).

Although the phenotype is severe in dystrophin-deficient dogs, quantifiable biomarkers of disease progression have been difficult to standardize. The ratio of diaphragmatic length to thickness reported here is arguably the most extreme morphometric abnormality noted in GRMD to date, and holds promise as an endpoint measure in translational research. Furthermore, having established quantifiable changes in respiratory mechanics and capacity in a group of dogs with the GRMD mutation and with relatively severe disease, we anticipate that longitudinal studies consisting of serial measurements of individual animals will further enhance the value of this translational model in view of the inherent phenotypic variability of the outbred GRMD line. This variability cannot be addressed by inbreeding without compromising the viability of the overall colony (32). Noninvasive or minimally invasive biomarkers of skeletal muscle function in GRMD are currently limited to analyses of gait, passive range of motion, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) analysis of muscle volume and composition, and of proximal and distal hindlimb muscle force during nerve electrostimulation (31). Because MRI and electrostimulation require general anesthesia in dogs, we have recently added doxapram respiratory studies before anesthesia reversal, without observable detriment to animals undergoing serial studies.

GRANTS

Support for this study was provided by National Institutes of Health Grants NS-042874, NS-052476, and RR-028027; and by the Muscular Dystrophy Association. A.F.M. and M.P. were supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Training Grant T32 AR-053461.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: A.F.M., M.P., A.S.M., M.A.M., G.S., J.N.K., and H.H.S. conception and design of research; A.F.M., M.P., A.S.M., M.K.C., J.R.B., G.S., and H.H.S. performed experiments; A.F.M., G.S., and H.H.S. analyzed data; A.F.M., M.P., A.S.M., M.A.M., and H.H.S. interpreted results of experiments; A.F.M. and H.H.S. prepared figures; A.F.M. and H.H.S. drafted manuscript; A.F.M., M.P., A.S.M., M.A.M., M.K.C., J.R.B., J.N.K., and H.H.S. edited and revised manuscript; A.F.M., M.P., A.S.M., M.A.M., M.K.C., J.R.B., G.S., J.N.K., and H.H.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Bogan and S. Chakkalakal for excellent technical assistance; and M. Cereda, D. Cooper, G. Guild, T. Khurana, S. Levine, D. Ren, S. Singhal, and T. Svitkina for insightful discussions.

Present address of M.K. Childers: Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98109.

Present address of J.N. Kornegay: Department of Veterinary Integrative Biosciences, (Mail Stop 4458), College of Veterinary Medicine, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843–4458.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aliverti A, Cala SJ, Duranti R, Ferrigno G, Kenyon CM, Pedotti A, Scano G, Sliwinski P, Macklem PT, Yan S. Human respiratory muscle actions and control during exercise. J Appl Physiol 83: 1256–1269, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen JE, Rodgin DW. Mental retardation in association with progressive dystrophy. Am J Dis Child 100: 208–211, 1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen JL, Wolfson MR, McDowell K, Shaffer TH. Thoracoabdominal asynchrony in infants with airflow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis 141: 337–342, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birnkrant DJ, Bushby KM, Amin RS, Bach JR, Benditt JO, Eagle M, Finder JD, Kalra MS, Kissel JT, Koumbourlis AC, Kravitz RM. The respiratory management of patients with duchenne muscular dystrophy: a DMD care considerations working group specialty article. Pediatr Pulmonol 45: 739–748, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biscoe TJ, Bucknell A. The arterial blood supply to the cat diaphragm with a note on the venous drainage. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci 48: 27–33, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brumback RA, Leech RW. Color Atlas of Muscle Histochemistry. Littleton, MA: PSG, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brumitt JW, Essman SC, Kornegay JN, Graham JP, Weber WJ, Berry CR. Radiographic features of Golden Retriever muscular dystrophy. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 47: 574–580, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang RF, Mubarak SJ. Pathomechanics of Gowers' sign: a video analysis of a spectrum of Gowers' maneuvers. Clin Orthop Relat Res 470: 1987–1991, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claflin DR, Brooks SV. Direct observation of failing fibers in muscles of dystrophic mice provides mechanistic insight into muscular dystrophy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C651–C658, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clanton TL, Levine S. Respiratory muscle fiber remodeling in chronic hyperinflation: dysfunction or adaptation? J Appl Physiol 107: 324–335, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen CA, Zagelbaum G, Gross D, Roussos C, Macklem PT. Clinical manifestations of inspiratory muscle fatigue. Am J Med 73: 308–316, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper BJ, Valentine BA. X-linked muscular dystrophy in the dog. Trends Genet 4: 30, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotten JF. TASK-1 (KCNK3) and TASK-3 (KCNK9) tandem pore potassium channel antagonists stimulate breathing in isoflurane-anesthetized rats. Anesth Analg 116: 810–816, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cotten JF, Keshavaprasad B, Laster MJ, Eger EI, 2nd, Yost CS. The ventilatory stimulant doxapram inhibits TASK tandem pore (K2P) potassium channel function but does not affect minimum alveolar anesthetic concentration. Anesth Analg 102: 779–785, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cotton SM, Voudouris NJ, Greenwood KM. Association between intellectual functioning and age in children and young adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: further results from a meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 47: 257–265, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dagan O, Nimri R, Katz Y, Birk E, Vidne B. Bilateral diaphragm paralysis following cardiac surgery in children: 10-years' experience. Intensive Care Med 32: 1222–1226, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Bruin PF, Ueki J, Bush A, Manzur AY, Watson A, Pride NB. Inspiratory flow reserve in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Pediatr Pulmonol 31: 451–457, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Troyer A, Loring SH. Action of the respiratory muscles. In: Handbook of Physiology. The Respiratory System. Mechanics of Breathing. Bethesda, MD: Am. Physiol. Soc, 1986, chapt. 3, p. 443–461 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodd DS, Brancatisano T, Engel LA. Chest wall mechanics during exercise in patients with severe chronic air-flow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis 129: 33–38, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fauroux B, Guillemot N, Aubertin G, Nathan N, Labit A, Clement A, Lofaso F. Physiologic benefits of mechanical insufflation-exsufflation in children with neuromuscular diseases. Chest 133: 161–168, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finder JD, Birnkrant D, Carl J, Farber HJ, Gozal D, Iannaccone ST, Kovesi T, Kravitz RM, Panitch H, Schramm C, Schroth M, Sharma G, Sievers L, Silvestri JM, Sterni L, American Thoracic Society Respiratory care of the patient with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: ATS consensus statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 456–465, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gazala S, Hunt I, Bedard EL. Diaphragmatic plication offers functional improvement in dyspnoea and better pulmonary function with low morbidity. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 15: 505–508, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbert R, Auchincloss JH, Jr, Peppi D. Relationship of rib cage and abdomen motion to diaphragm function during quiet breathing. Chest 80: 607–612, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gowers W. A manual of disease of the nervous system. London: Churchill, 1886 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gozal D. Pulmonary manifestations of neuromuscular disease with special reference to Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy. Pediatr Pulmonol 29: 141–150, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimby G, Goldman M, Mead J. Respiratory muscle action inferred from rib cage and abdominal V-P partitioning. J Appl Physiol 41: 739–751, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn A, Bach JR, Delaubier A, Renardel-Irani A, Guillou C, Rideau Y. Clinical implications of maximal respiratory pressure determinations for individuals with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 78: 1–6, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman EP, Brown RH, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchene muscular dystrophy locus. Biotechnology 24: 457–466, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang P, Cheng G, Lu H, Aronica M, Ransohoff RM, Zhou L. Impaired respiratory function in mdx and mdx/utrn(+/−) mice. Muscle Nerve 43: 263–267, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishizaki M, Suga T, Kimura E, Shiota T, Kawano R, Uchida Y, Uchino K, Yamashita S, Maeda Y, Uchino M. Mdx respiratory impairment following fibrosis of the diaphragm. Neuromuscul Disord 18: 342–348, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Konno K, Mead J. Measurement of the separate volume changes of rib cage and abdomen during breathing. J Appl Physiol 22: 407–422, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kornegay JN, Bogan JR, Bogan DJ, Childers MK, Grange RW. Golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD): developing and maintaining a colony and physiological functional measurements. Methods Mol Biol 709: 105–123, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kornegay JN, Bogan JR, Bogan DJ, Childers MK, Li J, Nghiem P, Detwiler DA, Larsen CA, Grange RW, Bhavaraju-Sanka RK, Tou S, Keene BP, Howard JF, Jr, Wang J, Fan Z, Schatzberg SJ, Styner MA, Flanigan KM, Xiao X, Hoffman EP. Canine models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy and their use in therapeutic strategies. Mamm Genome 23: 85–108, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krupnick AS, Gelman AE, Okazaki M, Lai J, Das N, Sugimoto S, Tung TH, Richardson SB, Patterson GA, Kreisel D. The feasibility of diaphragmatic transplantation as potential therapy for treatment of respiratory failure associated with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: acute canine model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 135: 1398–1399, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine S, Gillen M, Weiser P, Feiss G, Goldman M, Henson D. Inspiratory pressure generation: comparison of subjects with COPD and age-matched normals. J Appl Physiol 65: 888–899, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu C, Cripe TP, Kim MO. Statistical issues in longitudinal data analysis for treatment efficacy studies in the biomedical sciences. Mol Ther 18: 1724–1730, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lo Mauro A, D'Angelo MG, Romei M, Motta F, Colombo D, Comi GP, Pedotti A, Marchi E, Turconi AC, Bresolin N, Aliverti A. Abdominal volume contribution to tidal volume as an early indicator of respiratory impairment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Eur Respir J 35: 1118–1125, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manni R, Ottolini A, Cerveri I, Bruschi C, Zoia MC, Lanzi G, Tartara A. Breathing patterns and HbSaO2 changes during nocturnal sleep in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Neurol 236: 391–394, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mier-Jedrzejowicz A, Brophy C, Moxham J, Green M. Assessment of diaphragm weakness. Am Rev Respir Dis 137: 877–883, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milic-Emili J, Mead J, Turner JM, Glauser EM. Improved technique for estimating pleural pressure from esophageal balloons. J Appl Physiol 19: 207–211, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy DJ, Renninger JP, Schramek D. Respiratory inductive plethysmography as a method for measuring ventilatory parameters in conscious, non-restrained dogs. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 62: 47–53, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nahum A, Ravenscraft SA, Adams AB, Marini JJ. Inspiratory tidal volume sparing effects of tracheal gas insufflation in dogs with oleic acid-induced lung injury. J Crit Care 10: 115–121, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petrof BJ, Shrager JB, Stedman HH, Kely AM, Sweeney HL. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 3710–3714, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romei M, D'Angelo MG, LoMauro A, Gandossini S, Bonato S, Brighina E, Marchi E, Comi GP, Turconi AC, Pedotti A, Bresolin N, Aliverti A. Low abdominal contribution to breathing as daytime predictor of nocturnal desaturation in adolescents and young adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Respir Med 106: 276–283, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sackner MA, Watson H, Belsito AS, Feinerman D, Suarez M, Gonzalez G, Bizousky F, Krieger B. Calibration of respiratory inductive plethysmograph during natural breathing. J Appl Physiol 66: 410–420, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwartz MZ, Filler RM. Plication of the diaphragm for symptomatic phrenic nerve paralysis. J Pediatr Surg 13: 259–263, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharp NJ, Kornegay JN, Van Camp SD, Herbstreith MH, Secore SL, Kettle S, Hung WY, Constantinou CD, Dykstra MJ, Roses AD. An error in dystrophin mRNA processing in golden retriever muscular dystrophy, an animal homologue of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Genomics 13: 115–121, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith PE, Edwards RH, Calverley PM. Ventilation and breathing pattern during sleep in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Chest 96: 1346–1351, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stedman HH, Sweeney HL, Shrager JB, Maguire HC, Panettieri RA, Petrof B, Narusawa M, Leferovich JM, Sladky JT, Kelly AM. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature 352: 536–539, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takeda S, Nakahara K, Fujii Y, Matsumura A, Minami M, Matsuda H. Effects of diaphragmatic plication on respiratory mechanics in dogs with unilateral and bilateral phrenic nerve paralyses. Chest 107: 798–804, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thibaud JL, Matot B, Barthélémy I, Blot S, Carlier PG. Diaphragm structural abnormalities revealed by NMR imaging in the dystrophic dog. Neuromuscul Disord 23: 809–810, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waite A, Tinsley CL, Locke M, Blake DJ. The neurobiology of the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex. Ann Med 41: 344–359, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willis BC, Graham AS, Wetzel R, L, Newth CJ. Respiratory inductance plethysmography used to diagnose bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis: a case report. Pediatr Crit Care Med 5: 399–402, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]