Abstract

Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) is a non-heme iron enzyme that catalyzes phenylalanine oxidation to tyrosine, a reaction that must be kept under tight regulatory control. Mammalian PAH features a regulatory domain where binding of the substrate leads to allosteric activation of the enzyme. However, existence of PAH regulation in evolutionarily distant organisms, such as certain bacteria in which it occurs, has so far been underappreciated. In an attempt to crystallographically characterize substrate binding by PAH from Chromobacterium violaceum (cPAH), a single-domain monomeric enzyme, electron density for phenylalanine was observed at a distal site, 15.7Å from the active site. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments revealed a dissociation constant of 24 ± 1.1 µM for phenylalanine. Under the same conditions, no detectable binding was observed in ITC for alanine, tyrosine, or isoleucine, indicating the distal site may be selective for phenylalanine. Point mutations of residues in the distal site that contact phenylalanine (F258A, Y155A, T254A) lead to impaired binding, consistent with the presence of distal site binding in solution. Kinetic analysis reveals that the distal site mutants suffer a discernible loss in their catalytic activity. However, x-ray structures of Y155A and F258A, two of the mutants showing more noticeable defect in their activity, show no discernible change in their active site structure, suggesting that the effect of distal binding may transpire through protein dynamics in solution.

Keywords: Phenylalanine hydroxylase, substrate affinity, distal substrate binding site, regulation of enzyme activity

Introduction

Phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH) is a non-heme iron (II) enzyme that, in the presence of oxygen and cofactor 6(R)-L-erythro-tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), catalyzes the hydroxylation of L-phenylalanine to L-tyrosine (Fitzpatrick 2003; Kappock and Cardonna 1996). Phenylketonuria (PKU) arises when dysfunctional PAH in humans impairs metabolism of phenylalanine, leading to accumulation of abnormal levels of phenylalanine in the blood (Erlandsen et al. 2003; Scriver 1995). In mammals, PAH is a homotetramer; each subunit comprises three distinct domains, an N-terminal regulatory domain, a catalytic domain and a C-terminal oligomerization domain (Abu-Omar et al. 2005; Flatmark and Stevens 1999). Since the conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine is essentially irreversible and because PAH is expressed abundantly in the liver, activity of the enzyme is tightly regulated through allosteric activation by its own substrate, phenylalanine, binding at a secondary site in the regulatory domain (Chehin et al. 1998; Kaufman 1993; Kobe et. Al 1999; Li et al. 2011). Sequence homology analysis comparing the N-terminal regulatory domains of eukaryotic PAHs and prephenate dehydratase (PDH), an enzyme required for phenylalanine biosynthesis in bacteria, led to the discovery of two key conserved motifs implicit in phenylalanine binding: GAL (residues 46–48 in human PAH) and IESRP (residues 65–69 in human PAH) (Flydal et al. 2010; Gjetting et al. 2001). Deletion of the N-terminal regulatory domain of PAH liberates the enzyme of its requirement for activation by phenylalanine, therefore resulting in improved activity in the truncated enzyme (Daubner et al. 1997; Knappskog et al. 1996). Other factors such as phosphorylation of the serine residue at position 16 also aid in regulation of PAH (Kappock and Cardonna 1996; Fitzpatrick 1999; Horne et al. 2002; Parniak and Kaufman 1981). Additionally, recent work indicates that redox signaling involving Cys203 and Cys334 in human PAH may play a role in dynamic regulation of PAH (Fuchs et al. 2012).

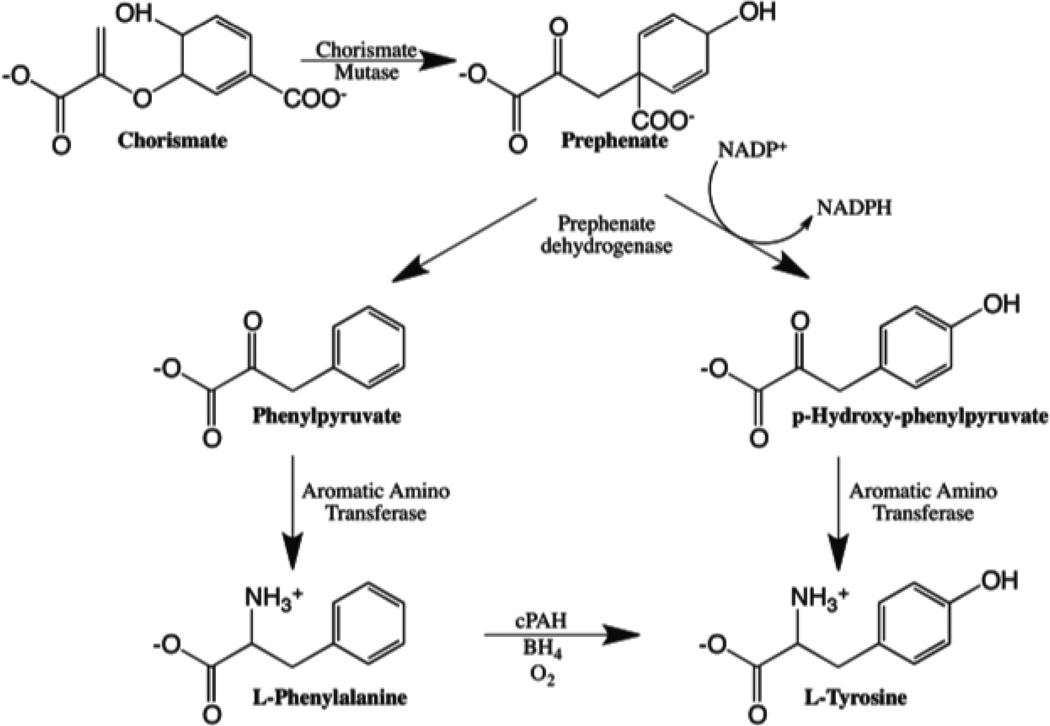

In certain bacteria in which PAH is found, the enzyme is a single domain, monomeric protein catalyzing the same conversion (Abu-Omar et al. 2005; Leiros et al. 2007). In Chromobacterium violaceum, conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine catalyzed by PAH (cPAH) provides a biosynthetic source of tyrosine, which is also synthesized via p-hydroxyphenyl pyruvate of the chorismate pathway, the same pathway that yields phenylalanine in the organism (Scheme 1) (Herrmann 1995; Singh 1999). The physiological role of this additional PAH-catalyzed route to tyrosine in bacteria is unclear; however, under certain conditions, such as nutrient starvation, one might expect that the conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine may be counterproductive, as this may lead to dangerous depletion of the phenylalanine pool in the organism. Tyrosine supply under such conditions can come exclusively from the chorismate pathway via p-hydroxyphenyl pyruvate. Therefore, it follows that, like its mammalian counterpart, the bacterial enzyme needs to be regulated as well. However, unlike its mammalian counterpart, cPAH lacks a regulatory domain and a second binding site for phenylalanine has never been observed kinetically or demonstrated structurally (Fitzpatrick 2012).

Scheme 1.

Tyrosine synthesis in some bacterial organisms, such as Chromobacterium violaceum, can occur via two pathways.

Even though human PAH (hPAH) is more complex than cPAH and the overall sequence similarity between both proteins is modest (35%), cPAH shares a similar structural motif as the catalytic domain of hPAH; both structures can be superimposed with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1.2 Å (Fusetti et al. 1998; Loaiza et al. 2008). Furthermore, the active site of both enzymes contains a histidine-histidine-glutamate catalytic triad, which together with water coordinates iron in octahedral geometry. Binding of substrate analogues 3-(2-thienyl)-L-alanine (THA) and L-norleucine (NLE) has been characterized in the active site of truncated catalytic domain hPAH using X-ray crystallography (Andersen et al. 2002; Andersen et al. 2003). Four main contacts appear to secure substrate analogues in place within the second coordination sphere of iron: hydrogen bonding with Ser349 and Arg270, backbone interaction with Thr278, and ring packing with His285 (Andersen et al. 2002). These residues are conserved in cPAH, except threonine has been replaced by leucine. To date no known crystallographic structures exist of PAH bound to its natural substrate, phenylalanine. Herein, we report our discovery of an additional substrate binding site in cPAH, a site 15.7 Å distal to the active site. ITC data consistent with the presence of this distal site are described. Additionally, through mutational analysis, we show that binding at the distal may affect catalysis, but not through conformational changes that could be observed by crystal structure analysis.

Experimental

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of cPAH

For crystallization, phenylalanine hydroxylase from Chromobacterium violaceum (cPAH) was sub-cloned from a pET3a vector into a pGEX-6P1 vector following standard cloning protocols. The resultant N-terminally fused glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged protein was expressed in the E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS strain (Novagen). Cells were grown at 37°C in Luria Bertani medium containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 50 µg/ml chloramphenicol. When OD600 reached ~0.5, expression of protein was induced with 1mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactpyranoside (IPTG) and advanced overnight at 18°C with shaking. The cells were centrifuged at 4 °C for 10 minutes at 7000×g and the pellet was subsequently resuspended in PBS containing 400 mM KCl and lysed via French Press. The crude extract was centrifuged at 4 °C for 1h at 22,000× g and the pellet was discarded. Further clarification of the supernatant was achieved with a final spin at 4 °C, 100,000× g for 15 minutes. Protein was purified with a glutathione-Sepharose column (GE Lifesciences) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, using PreScission Protease (GE Lifesciences) to cleave the GST tag. The protein was additionally purified in a buffer containing 50 mM TrisHCl, pH 7.6, 50 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex S75 column (GE Lifesciences) followed by anion exchange chromatography on a HiTrap DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow column (GE Lifesciences). The purity of the protein was assayed by SDS-PAGE and purified protein was concentrated using Amicon Ultra Centrifugal filters (Millipore), and buffer exchanged into 50 mM HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid), pH 7.4. Protein was stored at −80 °C, and concentration was determined spectrophotometrically.

For solution studies, cPAH was also purified from a pET3a vector in the absence of an affinity tag according to a previously published procedure (Volner et al. 2003) with some changes. Briefly, protein expression was induced with 1mM IPTG and proceeded overnight for 16 hours at 18 °C. The cells were harvested and lysed via French Press. cPAH was purified via DEAE-cellulose anion exchange chromatography followed by gel-filtration chromatography on a Superdex S75 column (GE-Lifesciences). Fractions corresponding to cPAH were concentrated, buffer exchanged into 70 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, and stored at −80 °C. Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically. This sample was also co-crystallized with Phe in the presence of Fe(II) to confirm the distal site binding of the substrate in the presence of native metal (see below).

Generation of cPAH point mutants

All mutant constructs were prepared using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Mutants were expressed in E. coli and purified following both purification methods described above.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

For crystallization, cPAH was concentrated to 10 mg/ml in a solution of 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Crystals of cPAH were obtained at ambient temperature utilizing hanging drop vapor diffusion from solution 43 of Hampton Research’s PEG/ION 2 screen (0.1 M Na-HEPES, pH 7.0, 0.01 M Magnesium chloride hexahydrate, 0.005 M Nickel (II) chloride hexahydrate, and 15% w/v PEG 3,350) with 8.3 mM Hexamine cobalt (III) chloride and 8.3 mM Guanidine hydrochloride as additives. Crystals of cPAH were grown via seeding initially with seeds from a mutant of cPAH, and then using seeds of the wild type protein. Seeds were generated by first crushing the crystals in solution removed from the reservoir under which the crystals grew, followed by breaking up crystals further using Seed Bead (Hampton Research). The total drop size was 5 µl (2 µl protein, 2 µl reservoir solution, 0.4 µl of each additive, 0.2 µl seeding solution). The substrate, phenylalanine, was introduced to the crystals using two methods: soaking and co-crystallization. In the soaking experiments, crystals were soaked in a solution containing 1 mM phenylalanine and 25% ethylene glycol as the cryoprotectant for 3 hours and then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. 10 mg/ml cPAH was preincubated in solution with 1 mM phenylalanine for 5 hours and then co-crystallized in the conditions described above. Crystals were soaked briefly in 25% ethylene glycol and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Data from phenylalanine soaked crystals (1.55 Å) and co-crystallized phenylalanine-cPAH (1.35 Å) were collected at beamline 23-ID-D of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Diffraction data were collected at 100K on a Mar300 CCD detector (Mar USA) and processed using the HKL3000 program (Otwinowski and Minor 1997). The crystals belong to the P1 space group with one molecule per asymmetric unit.

In order to obtain crystals of cPAH in its native Fe (II) metallated state, crystals were grown in a glove box (Innovative Technologies) under nitrogen atmosphere (≤ 2 ppm O2) in the absence of both nickel and cobalt. The crystallization buffer used in these experiments contained 0.1 M Na-HEPES pH 7.0, 0.01 M Magnesium chloride hexahydrate, and 15% w/v PEG. Crystals were grown by the seeded, sitting drop vapor diffusion method with 8.3 mM Ferrous ammonium sulfate and 8.3 mM Guanidine hydrochloride as additives. Phenylalanine soaking was carried out as described above, with a shorter soak period of 20 minutes since drops dried out quickly in the anaerobic environment. Crystals were flash frozen inside the glovebox after briefly soaking in a solution of 25% ethylene glycol.

The structure was determined by molecular replacement with the program molrep (Vagin and Teplyakov 1997) of the ccp4 suite (Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 1994) using the previously published apo-cPAH structure (PDB ID code 1LTU) (Erlandsen 2002). Cycles of refinement and model building were performed with the programs Refmac5 (Murshudov et al. 2011) and Coot (Emsley et al. 2010) respectively. Anisotropic B factors were used during the refinement of all structures except the structure of untagged cPAH bound to both Fe (II) and phenylalanine. Weights were optimized during the refinement of two structures: F258A mutant and the structure of untagged cPAH bound to both Fe (II) and phenylalanine. In some cases, such as the refinement of S203P, cPAH phenylalanine soaked and cocrystallized structures, TLS Motion Determination (Painter and Merritt 2006) was used. The Rcryst and Rfree for the phenylalanine soaked structure, which includes residues 7–283 in the polypeptide chain, are 16.3% and 20.7% respectively. The Rcryst and Rfree for the co-crystallized phenylalanine-cPAH structure are 15.9% and 20.7%. The crystallographic data and refinement statistics are listed in Tables 1 and 2. All figures were rendered with the program PYMOL (Version 1.5.0.4).

Table 1.

Crystallographic refinement statistics for Phe soaked, co-crystallized, and iron bound cPAH structures.

| cPAH Soaked with Phe |

cPAH Cocrystallized with Phe |

wt cPAH | cPAH (Fe) Soaked with Phe |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| Space group | P1 | P1 | P1 | P1 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 36.7, 38.3, 47.7 | 36.9, 38.6, 47.8 | 36.9, 38.6, 47.9 | 38.3, 36.8, 48.4 |

| , , ( ) | 76.7, 73.0, 85.7 | 76.6, 72.9, 85.4 | 76.5, 73.2, 85.4 | 107.7, 103.9, 84.6 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0-1.55 (1.58-1.55) | 50.0-1.35 (1.37-1.35) | 50.0-1.50 (1.53-1.50) | 50.0-2.14 (2.18-2.14) |

| Rmerge (%) | 3.6 (24.0) | 4.3 (19.7) | 3.1 (33.7) | 6.4 (40.3) |

| I / I | 26.2 (2.3) | 34.2 (5.3) | 24.2 (1.8) | 18.8 (2.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 95.0 (84.6) | 93.5 (84.0) | 95.1 (82.5) | 94.0 (68.6) |

| Redundancy | 2.3 (2.0) | 3.9 (3.3) | 1.9 (1.7) | 3.7 (2.7) |

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 1.55 | 1.35 | 1.50 | 2.14 |

| No. reflections | 31363 | 47843 | 35492 | 12125 |

| Rwork / Rfree | 16.3/20.7 | 15.9/20.7 | 17.1/21.0 | 20.6/25.1 |

| No. atoms | ||||

| Protein | 2227 | 2259 | 2246 | 2139 |

| Ion | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Water | 228 | 339 | 195 | 26 |

| R.m.s. deviations Bond lengths (Å) | 0.011 | 0.025 | 0.010 | 0.010 |

| Bond angles ( ) | 1.400 | 2.199 | 1.324 | 1.402 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | ||||

| Protein | 16.1 | 13.6 | 14.5 | 31.3 |

| Ion | 18.6 | 15.0 | 26.4 | 31.8 |

| Water | 32.9 | 26.5 | 29.7 | 38.4 |

| Ligand | 17.6 | 18.7 | --- | 27.1 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

Rsym = ΣΣ|Ihkl − Ihkl(j)|/ΣIhkl, where Ihkl(j) is the observed intensity and Ihkl is the final average intensity.

Rcrys = Σ‖Fobs| − |Fcalc‖/Σ|Fobs| and Rfree = Σ‖Fobs| − |Fcalc‖/Σ|Fobs|, where Rfree and Rcrys are calculated using a randomly selected test set of 5% of the data and all reflections excluding the 5% test data, respectively

Table 2.

Crystallographic refinement statistics for distal site mutants of cPAH.

| S203P | Y155A | F258A | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P1 | P1 | P1 |

| Cell dimensions | |||

| a, b, c (Å) | 37.0, 38.6, 47.9 | 36.8, 38.4, 47.8 | 36.8, 38.6, 48.0 |

| , , ( ) | 76.7, 73.2, 85.5 | 76.5, 72.9, 86.0 | 76.5, 73.0, 85.4 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0-1.55 (1.58-1.55) | 50.0-1.35 (1.37-1.35) | 50.0-1.49 (1.52-1.49) |

| Rmerge (%) | 4.0 (26.8) | 3.9 (27.0) | 5.9 (34.7) |

| I / I | 15.5 (2.5) | 35.3 (2.4) | 20.1 (2.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 92.7 (81.1) | 90.4 (51.3) | 92.0 (59.7) |

| Redundancy | 1.6 (1.5) | 3.7 (2.5) | 3.7 (2.5) |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 1.55 | 1.35 | 1.49 |

| No. reflections | 31409 | 45873 | 35044 |

| Rwork / Rfree | 16.9/20.7 | 15.2/18.1 | 16.5/21.4 |

| No. atoms | |||

| Protein | 2259 | 2223 | 2234 |

| Ion | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Water | 256 | 259 | 208 |

| R.m.s. deviations Bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| Bond angles ( ) | 1.361 | 1.313 | 1.248 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |||

| Protein | 11.7 | 18.2 | 18.7 |

| Ion | 8.9 | 21.4 | 26.0 |

| Water | 23.7 | 33.1 | 30.1 |

| Ligand | 11.7 | --- | --- |

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) experiments were conducted aerobically and anaerobically at 25 °C on a GE/MicroCal ITC200 Calorimeter. Enzyme solutions were prepared by an overnight dialysis against 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). A typical experiment under aerobic conditions consisted of titrating a 1–10 mM phenylalanine solution into a 50–100 µM protein solution. To test the selectivity of the distal site, a 1.5 mM solution of tyrosine, a 1.5 mM solution of isoleucine, and a 1 mM solution of alanine were separately titrated into a 50 µM protein solution. A total of 18 injections (2 µ L/injection) were performed for cPAH (WT, S203P, T254A, F258A, and Y155A). Reference subtraction (titration of ligand in buffer only) was conducted for each analysis. Each experiment had a spacing of 180 secs between injections. The experiments were performed in duplicates with varying titrant concentrations. The data was then analyzed using the one-site model in SEDPHAT (v. 10.40) (Houtman et al. 2007) and MicroCal Origin software version 7.0 (provided by GE).

In experiments aimed at examining active site binding of phenylalanine upon reconstitution of the active site, ITC experiments were conducted in an anaerobic glovebox (PlasLabs) under argon atmosphere at 25 °C, in order to prevent oxidation of (6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin dihydrochloride (BH4). Buffer solutions were stored in vials with rubber septa caps and deoxygenated extensively by bubbling argon gas through them. Preweighed amounts of solid L-Phe, BH4, and ferrous ammonium sulfate were placed in separate vials and brought into the glovebox, along with protein samples and degassed buffers. Ferrous ammonium sulfate was dissolved in 10 mM HCl while both BH4 and L-Phe were dissolved in dialysis buffer. In order to reconstitute the apo enzyme with ferrous iron, dissolved oxygen was initially removed from the protein solution by gently pipetting the solution up and down for at least 50 repetitions followed by the addition of 0.5–1.0 mol ferrous ammonium sulfate (25–50 µM) per mol of PAH to the enzyme (50–100 µM). For experiments in which phenylalanine was titrated into reconstituted enzyme, 200 µM BH4 was also added to the enzyme and was allowed to equilibrate at 25 °C for 15 minutes prior to the start of the experiment. A typical experiment involved titrating either a 1–10 mM solution of phenylalanine or a 0.75–1.0 mM solution of BH4 into the protein solution.

Steady-state kinetic studies

Enzyme activity was measured on a Shimadzu UV-2501 double-beam spectrophotometer equipped with a thermostat-controlled cuvette holder. Assays were conducted at 20 ± 1°C by following hydroxylation of phenylalanine to tyrosine at 275 nm. 1mL total volume assay mixtures contained 0.8–2 µM cPAH, a five fold excess of ferrous ammonium sulfate (FeSO4) with respect to enzyme concentration, 0.1 M Na-HEPES (pH 7.4) saturated with O2, 100U/ml bovine catalase, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 350 µM 6,7-dimethyltetrahydropterin (DMPH4), and were initiated with 10–1200 µM L-phenylalanine. Initial rates were determined by measuring absorbance from 10 s up to 20 s following initiation by phenylalanine. Assays for each mutant and the wild type protein were conducted in triplicate. All kinetic data were analyzed using the program Kaleidagraph and fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation Vi = Vmax[S]/(KM+[S]). The parameters for kcat/KM were obtained from the plot of Vi versus [S] by determination of the slope of the linear portion of the curve according to the following expression: kcat/KM = slope/E where E represents the final enzyme concentration. Data are given as mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

We performed molecular dynamics simulations using the AMBER package (Case et al. 2012) to elucidate the impact of distal Phe binding on structure and dynamics of cPAH. We simulated three systems applying identical simulation protocols: cPAH with bound Fe3+ based on coordinates from Erlandsen et al. (1LTV) and two systems based on the X-ray structure of cPAH with Phe bound to the newly discovered distal site (3TCY). One simulation contained the bound Phe, for the other the ligand was artificially removed. For the latter two simulations the bound Co2+ was replaced by a Fe3+ for consistency. For all simulations we removed co-crystallized ethanediol molecules but preserved all resolved water molecules for the simulations. Systems were protonated in MOE (Labute 2009) and a truncated octahedral water box with a minimum wall distance of 12 Å was added.

The AMBER force field 99SB-ILDN (Lindorff-Larsen et al. 2010) was applied for protein residues, the TIP3P model for water (Jorgensen et al. 1983). The Fe3+ ion was treated as described earlier (Fuchs et al. 2012), partial charges for free Phe were derived via RESP fitting (Bayly et al. 1993) at HF/6-31G*-level. Atom types for free Phe were chosen as a combination of N-terminal and C-terminal Phe for the backbone atoms as well as standard Phe for the side chain. After a detailed equilibration protocol (Wallnoefer et al. 2010) 1 µs of sampling trajectories were collected for each of the three systems by the GPU accelerated code of AMBER (Goetz et al. 2012). Analysis of trajectories included 1D and 2D root mean square deviation analysis of protein atom positions to ensure stability of molecular dynamics simulations. Further analyses covered the calculation of residue-wise fluctuations as B-factors as well as extraction of geometries and secondary structure elements from stored coordinates.

Accession Numbers

Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the PDB with accession numbers 3TCY (Phe soaked cPAH), 3TK2 (cPAH co-crystallized with Phe), 3TK4 (Cobalt-bound cPAH), 4JPY (Iron and Phe-bound cPAH), 4JPX (S203P), 4ESM (Y155A), and 4ETL (F258A).

Results

Crystallographic characterization of substrate binding at the distal site on cPAH

In an attempt to crystallographically characterize substrate binding with cPAH, two methods of ligand introduction were utilized: crystal soaking and pre-incubation of enzyme and the substrate in solution prior to crystallization. Crystals of cPAH, soaked in cryoprotectant containing three-fold molar excess of phenylalanine with respect to enzyme concentration (in the crystallization drop), diffracted to 1.55 Å resolution (Table 1). The cPAH construct used in these experiments was purified as a GST-fused construct following GST affinity chromatography and the tag was proteolytically removed (see Materials and Methods). It was crystallized from a solution that contained both hexamine cobalt(II) chloride and nickel chloride. The structure was determined by molecular replacement (MR) using a previously solved structure of cPAH as the search model (PDB code 1LTU (Erlandsen et al. 2002)). Strong electron density near the active site in the 2Fo-FC map calculated with the model that resulted after the MR search indicated the presence of bound metal, at the same place where iron was seen in a previous structure of cPAH soaked with ferrous ammonium sulfate (PDB code 1LTV (Erlandsen et al. 2002)). We modeled a cobalt(II) ion into this density based on the fact that we have more cobalt than nickel salt in the crystallization buffer. The structures we discuss hereafter all contain a modeled cobalt ion at the active site, however since the identity of the metal in the active site has not been established, we refer to the structures as metallated PAH. These metallated cPAH models were nearly identical to the Fe(III) bound cPAH structure that was reported before (Erlandsen et al. 2002) and our own structure of cPAH purified following the procedure described by Erlandsen et al. and crystallized in a glove box under oxygen-free environment in the presence of Fe(II) (see below). Refinement of the crystallographic data led to final Rcrys and Rfree values of 16.3% and 20.7%, respectively (Table 1). Clear electron density for phenylalanine was observed, indicating phenylalanine was bound to the enzyme, but not in the active site. A 2Fo-Fc electron density difference map, contoured at = 2, depicted density that was unambiguously interpreted as phenylalanine in a site 15.7 Å distal to the active site (Figure 1) (distance between C atom of the substrate and the active-site metal).

Figure 1.

Phenylalanine binding in cPAH. A 2Fo-Fc map contoured at σ = 2, depicts density for phenylalanine indicating it binds at a distal site 15.7 Å from the active site (the active site metal is shown as a black sphere).

Phenylalanine (final concentration of 1 mM) was pre-incubated in solution with cPAH for 5 hours prior to crystallization without additional phenylalanine soaking following crystallization. These crystals diffracted to a resolution of 1.35 Å and the structure was refined to Rcrys and Rfree values of 15.9% and 20.7%, respectively (Table 1). Electron density shows that once again, phenylalanine is nestled in the distal binding site, occupying the same orientation as seen in the soaked crystals, with no discernible density in the active site. The average B-factors estimated after final refinement for phenylalanine from soaked and co-crystals are 17.6 Å2 and 18.7 Å2, respectively. Comparatively, the average B-factor for the entire phenylalanine-soaked and co-crystallized protein is 16.1 and 13.6 Å2, respectively (Table 1), suggesting nearly complete occupancy at the distal site.

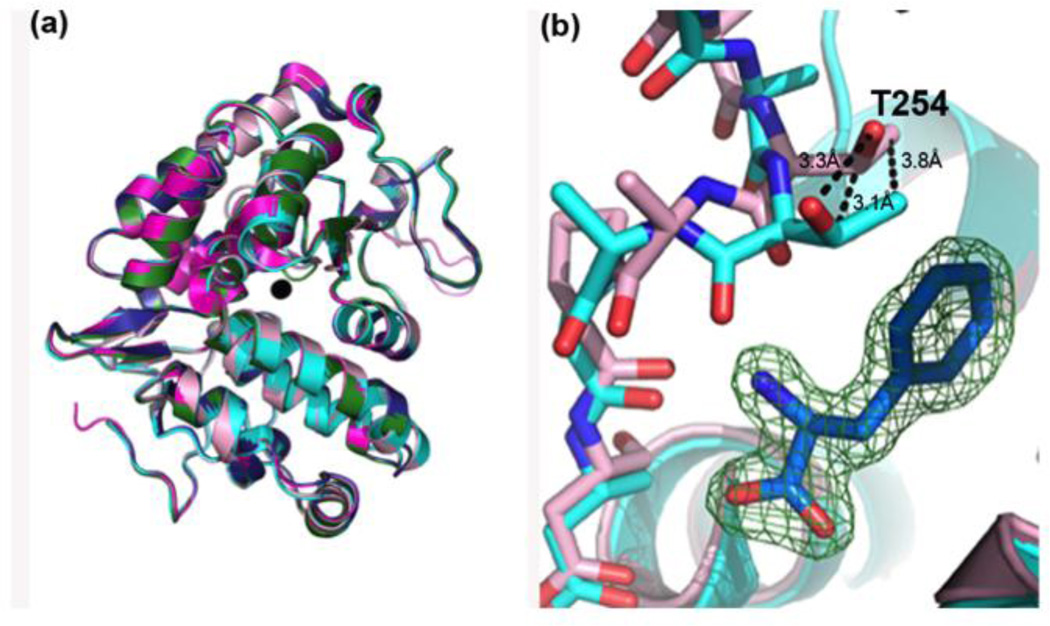

Structural changes to the backbone upon binding of phenylalanine in the distal site are minimal, with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.33 Å among alpha carbons, and predominately localized to residues that constitute the binding pocket (Figure 2A). The 254–257 loop, which connects the 13 helix with the 14 helix, shifts slightly outward. Most notably, Thr254 is displaced approximately 3.2 Å and rotates to create enough space to accommodate binding of phenylalanine (Figure 2B). The binding pocket is comprised mainly of hydrophobic amino acids and phenylalanine is stabilized largely through van der Waals contacts with hydrophobic side chains lining the pocket (Figure 3A). For example, the aromatic ring of phenylalanine stacks against that of Phe258 at an average interplanar distance of 3.8 Å. Additional van der Waals contacts are made with phenylalanine and the side chains of Leu178, Tyr155, Tyr159, and Ala158. Hydrogen bonding also appears to be important in this binding event and occurs between phenylalanine and the main chain atoms of Pro256, Phe258, Asp257, Thr254, and Ala158 (Figure 3B). Phenylalanine is further stabilized through hydrogen bonding with an invariant water molecule that interacts with Gly162 and Tyr262. All these interactions appear to ensure tight binding of the substrate at this distal site, with nearly each atom of the substrate making contact with one or more atoms on the residues lining up the distal site pocket, indicative of a high-affinity interaction. Finally, the distal binding pocket appears to be closed after substrate binding through the formation of a salt bridge near the surface between Asp257 and Lys165 (Figure 3B). These results indicate that the distal site presents substantial attractive forces for binding of the substrate. We were curious as to whether this second phenylalanine site is conserved in other bacteria yielding single domain, monomeric PAH. Alignment of other bacterial sequences to C. violaceum indicate that many of the residues are conserved in some bacterial PAHs while others do not observe such conservation, suggesting that some proteins may have the site and others do not (Supporting Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Global structural changes in the backbone of cPAH upon binding of phenylalanine in the distal site are minimal. (a) Superposition of 5 cPAH structures: wt-phe bound (pink), wt-Co(II) (cyan), wt-apo (1LTU, magenta), wt-Fe(III) (1LTV, blue), and wt-Fe(III)-BH2 (1LTZ, green) indicated the backbone is relatively unchanged after phenylalanine binding. (b) The most notable structural change occurs when T254 shifts to create a space to accommodate phenylalanine binding.

Figure 3.

Tight binding of phenylalanine in the distal binding pocket does not result in major conformational changes. (a) Phenylalanine makes numerous van der Waals contacts with neighboring residues and is further stabilized predominately by (b) hydrogen bonding with main chain residues. (c) Distal site substrate binding does not result in conformational crosstalk with residues in the active site. Superposition of the distal phe bound (pink) and unbound wild type (cyan) structures is shown here.

The absence of any discernible electron density for phenylalanine at the active site could mean that it was occluded in some way or that binding here requires the presence of the pterin cofactor (see below). Pre-incubation of phenylalanine with the enzyme prior to crystallization should discount the notion that the lack of density for phenylalanine at the active site is the result of crystal packing. Furthermore, inspection of crystal packing indicates that, as expected for a polar active site, solvent channels are not impeded due to packing.

As mentioned above, the studies presented so far have been conducted with protein purified by GST affinity chromatography and the GST tag was proteolytically removed (see Experimental Procedures). However, we noticed that the catalytic activity of the protein purified in this manner was lower than that of the protein purified without any tag reported previously (Volner et al. 2003) (see Experimental Procedures, Supporting Figure S2. The GST method did not include EDTA in the buffer, but the later procedure did). We therefore chose to conduct further studies with untagged protein, purified using a previously published procedure, for kinetic analysis and ITC (see below). We confirmed by X-ray structural analysis that the untagged protein binds to phenylalanine at the distal site (Supporting Figure S3).

To offset concern that phenylalanine may bind in the distal site as the result of occupancy of an inhibitory metal, such as cobalt, in the active site (Zoidakis et al. 2005), the untagged protein purified according to the procedure of Erlandsen et al. (Erlandsen et al. 2002) was crystallized in the presence of the native metal, iron, in a glove box under nitrogen atmosphere. These crystals diffracted at a resolution of 2.14 Å and the structure was refined to Rcrys and Rfree values of 20.6% and 25.1% respectively (Table 1). Electron density indicates that with Fe (II) bound in the active site, phenylalanine still preferentially binds in the distal site in the same orientation as described above (Supporting Figure S4). From this structure it can be concluded that phenylalanine binding in the distal site does not arise only when an inhibitory metal occupies the active site, but also when the enzyme is bound to its native metal.

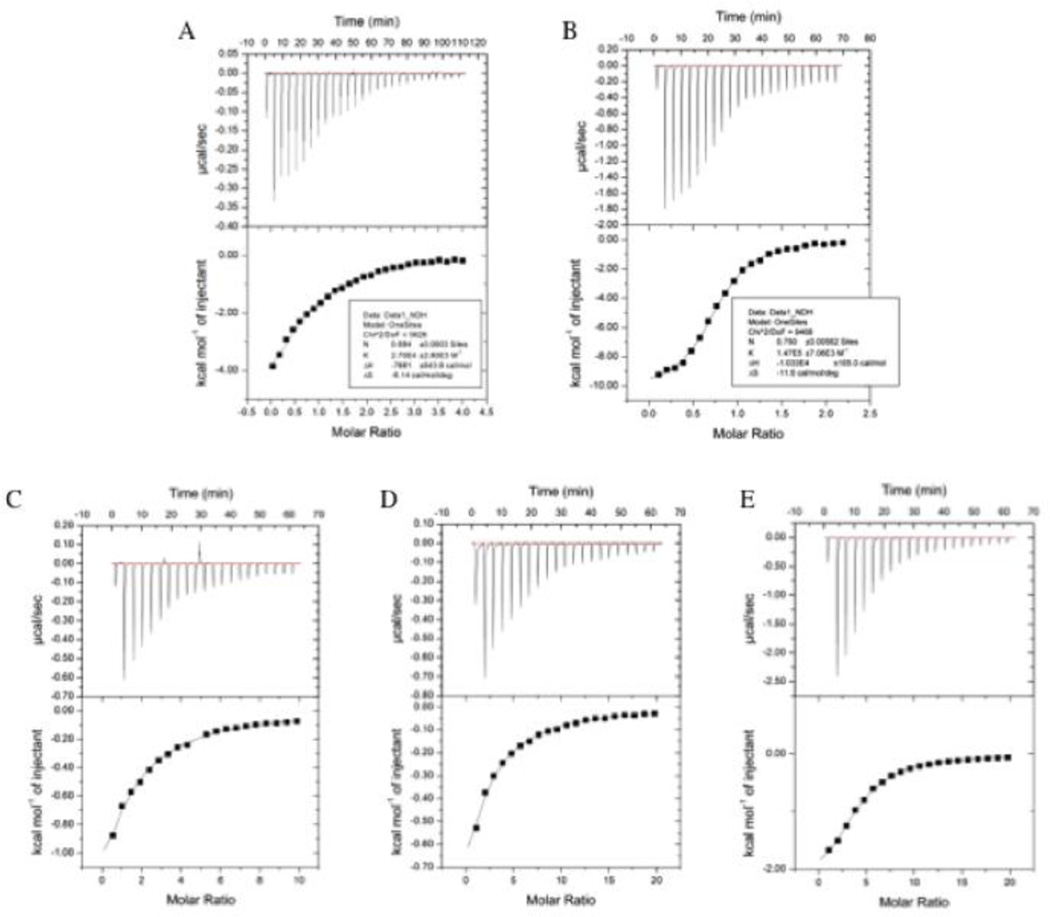

Distal site phenylalanine binding in solution

To elucidate whether binding in the distal site also exists in solution, ITC was employed. In contrast to our expectation that two separate binding events would be observed, one corresponding to the active site and one to the distal, titration produced a binding isotherm (Figure 4A) that could be satisfactorily fitted to a one-site model yielding a dissociation constant (Kd) of 24 ± 1.1 µM (Table 3). Such a result may indicate the presence of only one binding site on the protein or two sites with similar Kd and enthalpy of binding (Mayers et al. 2011). To probe this further, distal and active-site mutants were generated. Three point mutations (F258A, Y155A, T254A) in the distal site were made in side chains that interact with bound phenylalanine, presumably resulting in an enzyme with lowered affinity for phenylalanine at the distal site. Phe258 was selected because it makes a stacking interaction with the aromatic ring of phenylalanine. Tyr155 also makes contact with phenylalanine in the distal site, while the side chain of Thr254 moves to make space for phenylalanine binding. The results of the ITC experiments indicated a marked decrease in the affinity for phenylalanine by the three mutants: T254A, Y155A, and F258A with Kds of 376 ± 10 µM, 559 ± 30 µM and 775 ± 44 µM, respectively (Figures 4B–4D, Table 3). Further analysis using a two-site model did not reveal any statistical difference from the one-site model. The precision of the stoichiometry (n) becomes ambiguous in the case of the mutants because the c value (the ratio of total ligand concentration in the cell versus the Kd value) is small (c<40) due to the large Kd and the shape of the thermogram (Broecker et al. 2011). The clear impairment of phenylalanine binding in all three cases indicates that the binding characterized in the wild-type cPAH ITC experiment involved either the distal site alone or at least a contribution of the distal site to binding in solution.

Figure 4.

Representative thermograms for phenylalanine binding to wild type cPAH (a) distal binding mutants: (b) Y155A, (c) T254A, and (d) F258A, and the active site mutant (e) S203P. The protein concentration ranged from 50–100 µM with the titrant (phenylalanine) concentrations at 1–10 mM.

Table 3.

Dissociation constants and thermodynamic parameters for binding of phenylalanine to native cPAH and distal site mutants at 25°C.

| Sample | Location | Kd (µM) | ΔH0 (kcal mol−1) | ΔS (cal mol−1 K−1) | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cPAH | - | 24 ± 1.1 | −10.8 ± 0.2 | −15.4 | 0.9 |

| Y155A | Distal site | 559 ± 30 | −3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.8 | 0.6 |

| F258A | Distal site | 775 ± 44 | −12.0 ± 7.1 | −26.1 | 0.7 |

| T254A | Distal site | 376 ± 10 | −11.9 ± 1.3 | −24.5 | 0.7 |

| S203P | Active site | 7.0 ± 0.3 | −11.2 ± 0.1 | −14.0 | 0.6 |

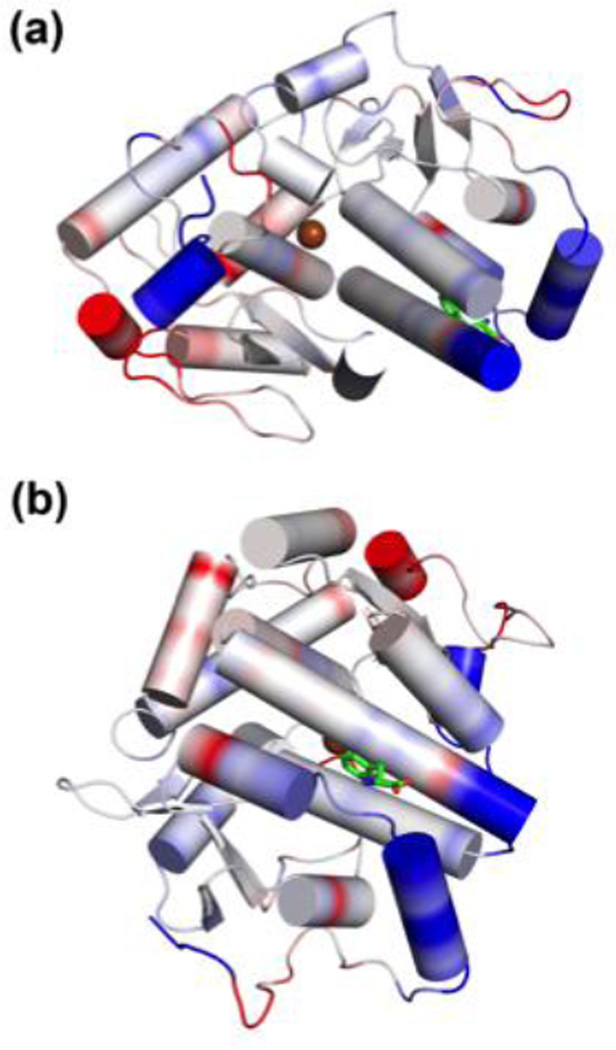

To rule out the possibility that the mutations in the distal phenylalanine binding site may have impaired binding in the active site as a result of gross changes in the global structure of the proteins, we crystallized both Y155A and F258A mutants (purified using GST affinity chromatography). The crystal structures for both mutants were found to be nearly identical to that of wild type cPAH in the active site region of the proteins (Figure 5, Table 2). For Y155A, the only difference found relative to wild type is localized near the distal site. The gap generated by removal of the bulky tyrosine phenolic group was occupied by a nearby aromatic residue, Tyr 159, which flips its ring to fill the cavity (Supporting Figure S5). This structural adjustment indicates a certain amount of conformational plasticity in the distal site, perhaps in the entire protein. The Y155A mutant crystals were soaked with phenylalanine (at the same concentration as wild type) and, consistent with the ITC data, did not show any electron density for the substrate anywhere in the protein. The same was also true for the F258A mutant. It is unlikely that the structural results would be any different if we had studied untagged mutants in crystallography experiments. The N-terminal part of the polypeptide chain, including the pentapeptide GST leftover sequence (GPLGS), was disordered and not visible in the crystal structures.

Figure 5.

The distal mutant crystallographic structures were found to be nearly identical to wild type cPAH. Y155A (red) and F258A (gray) superposed with the wild type cPAH phenylalanine bound structure (pink) reveals no changes to the structure in the backbone (a) or in the active site (b).

To further investigate binding in solution, a mutant in the active site, S203P, expected to show reduced binding of phenylalanine there, was studied. The choice of this mutation is based on the fact that a naturally occurring mutation of the equivalent serine residue in hPAH leads to PKU, possibly due to loss of hydrogen bonding with the substrate at the active site resulting in a catalytically impaired enzyme. This is supported by the crystal structure of the catalytic domain of hPAH bound to THA, which shows that the serine residue is engaged in hydrogen bonding with the substrate analog at the active site (Andersen et al. 2002). Indeed, our results show that this mutant is catalytically less active than wild-type cPAH (Figure 8A and Table 5). Interestingly, S203P cPAH reveals a better binding affinity for phenylalanine than wild type, with Kd close to 7 ± 0.3 M (Figure 4E, Table 3). It is unclear why S203P has a higher affinity for phenylalanine than wild type cPAH. It is possible that the binding affinity probed by ITC actually represents an average of two distinct binding events, one at the distal site (Kd1) and one at the active site (Kd2), with Kd1<Kd2, which seems reasonable for the following reason. Our crystal structures obtained in the presence of phenylalanine indicate occupancy of phenylalanine in the distal site, but not the active site, even in the absence of steric occlusion. Therefore, it is conceivable that by impairing the contribution of the presumed higher affinity site, the distal site (represented above as Kd1), the overall affinity for substrate will be reduced, resulting in higher Kd values (Table 3, F258A, T254A, Y155A). Furthermore, impairment of the lower affinity site, the active site (represented above as Kd2), would have the opposite effect: the overall binding would be improved, resulting in lower Kd values, as seen with the S203P mutant. Alternatively, the S203P mutation may actually lead to a better but unproductive binding of Phe at the active site (this mutant shows impaired catalysis) due to attraction of the greasy pyrrolidine ring of proline. Such an unproductive binding may reflect a gain in the overall affinity for phenylalanine. It is also possible that mutation of Ser203 might have caused a conformational rearrangement at the distal site leading to better binding there, however the crystal structure of the S203P mutant shows no noticeable change in either the active or the distal site, with the mutant showing distal-site binding as expected in the co-crystal structure (Table 2, Supporting Figure S6). Thus our ITC data and crystal structures so far appear to provide evidence of phenylalanine binding in the distal site but no evidence of it binding in the active site. One explanation for why we can’t detect active site binding of phenylalanine by ITC, although we know it does exist since the enzyme catalyzes conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine, could be that the affinity for phenylalanine in the active site of cPAH is dependent on the presence of cofactor, pterin. This notion is based on the kinetic analysis ofVolner et al. (2003) which showed that binding of BH4 precedes phenylalanine and hence may be required for its binding.

Figure 8.

Phenylalanine binding in the distal site leads to rigidification of the protein. B-factor difference maps from molecular dynamics simulations are shown above in two orientations of the same structure. The blue-white-red spectrum highlights regions of the protein that become rigidized in simulations with bound phenylalanine (blue), as well as areas that are more flexible (red). White regions indicate no change in flexibility during simulations. The distal Phe binding site (b) shows that helices near the site are rigidized upon binding of phenylalanine.

Table 5.

Steady-state kinetic parameters of phenylalanine hydroxylase and distal site mutants.

| Sample | Location | KM (µM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/KM (µM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cPAH | - | 244 ± 40.8 | 18.0 ± 0.03 | 0.048 ± 0.01 |

| Y155A | Distal site | 136.5 ± 5.91 | 8.81 ± 0.43 | 0.025 ± 0.004 |

| F258A | Distal site | 467.5 ± 99.6 | 10.9 ± 1.7 | 0.014 ± 0.0005 |

| T254A | Distal site | 414.0 ± 51.1 | 21.5 ± 2.3 | 0.032 ± 0.004 |

| S203P | Active site | 687.2 ± 53.0 | 4.9 ± 0.19 | 0.0056 ± 0.001 |

Data are given as mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

We therefore reasoned that reconstitution of the active site by including Fe(II) and BH4 may enhance its binding affinity for the substrate in that site. BH4 was used instead of DMPH4, which is used in kinetics (see below), since it binds better in ITC (kinetically, the two are more or less the same) (Volner et al. 2003; Citron et al. 1992; Phillips et al. 1984). These experiments were conducted under an anaerobic argon environment to prevent oxidation of BH4 and Fe(II). The Kd values obtained are presented in Table 4. Contrary to our expectation, we did not notice a significant difference in phenylalanine binding with wild-type cPAH or any substantial difference with the mutants S203P, T254A and F258A (Figure 6A–D). Y155A, however, shows appreciable improvement in binding in the presence of BH4 and Fe(II) (Figure 6E). Overall, these results indicate that ITC is more sensitive to distal rather than active site binding and that pterin’s presence in the active site has no bearing upon phenylalanine binding. In fact, going back to the structure of hPAH bound to BH4 and THA (Andersen et al. 2002), we could see no contact between BH4 and the substrate analog, indicating that our assumption that pterin binding will improve affinity for phenylalanine is perhaps not valid. Accordingly none of the variants we have studied, including S203P, showed any improvement in binding affinity for phenylalanine in the presence of pterin. It is possible that reconstitution is partial at best owing to BH4 inadequately binding under the conditions employed here, although we did observe BH4 binding with the protein samples in separate titration experiments with 16–44 µM affinity for wild type and mutants (Table 4 Supporting Figure S7). Based on this, we expected the cofactor to be bound under the conditions used in reconstitution.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters obtained via ITC for BH4 and L-Phe binding to cPAH and distal mutants upon reconstitution of the enzyme’s active site.

| Sample | Ligand | Kd (µM) | ΔH0 (kcal mol−1) | ΔS (cal mol−1 K−1) | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cPAH-Fe•(BH4) | Phe | 37 ± 0.3 | −7.9 ± 0.8 | −6.1 | 0.7 |

| Y155A-Fe•(BH4) | Phe | 171 ± 10 | −2.7 ± 0.1 | 8.3 | 0.5 |

| F258A-Fe•(BH4) | Phe | 529 ± 14 | −7.9 ± 0.1 | −11.6 | 0.5 |

| T254A-Fe•(BH4) | Phe | 329 ± 31 | −7.4 ± 4.2 | −8.8 | 0.5 |

| S203P-Fe•(BH4) | Phe | 6.8 ± 0.3 | −10.3 ± 0.1 | −11.0 | 0.8 |

| cPAH-Fe | BH4 | 23.5 ± 1.6 | −6.4 ± 0.4 | −0.4 | 0.7 |

| Y155A-Fe | BH4 | 16.2 ± 0.7 | −3.5 ± 0.1 | 10.2 | 1 |

| F258A-Fe | BH4 | 29.3 ± 1.6 | −4.6 ± 0.2 | 5.2 | 0.9 |

| T254A-Fe | BH4 | 43.6 ± 4.2 | −5.8 ± 0.6 | 0.4 | 1 |

| S203P-Fe | BH4 | 35.2 ± 3.3 | −3.4 ± 0.4 | 8.9 | 0.6 |

The protein concentration used was 100 µM for L-Phe and 50 µM for the binding of BH4.

Figure 6.

Representative isothermal titration calorimetry data obtained for the binding of L-Phe upon active site reconstitution with 50 M ferrous ammonium sulfate and 200 M BH4 in 100 M wild type cPAH (a) and distal binding mutants: (b) S203P, (c) T254A, (d) F258A, and (e) Y155A.

Y155A showed a noticeable improvement in Kd when both BH4 and Fe(II) were present. This can be explained by the advent of a new mode of binding which is different than productive binding at the active site. If it was active site productive binding, then Y155A would be a better catalyst than T254A, but it is not. Also, the kinetic data show that this mutant behaves anomalously, showing less activity at higher concentration of substrate, indicative of unproductive binding at high substrate concentration (Figure 8A). It is unlikely that BH4 and/or Fe(II) binding may have bolstered the distal site slightly leading to improvement there, although this cannot be ruled out.

The distal site selectively binds phenylalanine

It is possible that the distal binding site observed here is a result of accidental binding of the substrate at a sticky patch on the surface. Such a patch is expected to be less selective; it could bind other amino acids as well. To ascertain whether the distal site binds phenylalanine selectively, attempts were made to obtain binding information of two other amino acids, tyrosine and alanine, both crystallographically and via calorimetry. We were most interested in the possibility of tyrosine binding, because if bound in the distal site, it could serve to regulate the enzyme through product inhibition. We also chose to use isoleucine as a hydrophobic mimic of phenylalanine, while alanine serves as a general representative of most amino acids. Co-crystallization and crystal soaking with both tyrosine and a tyrosine analogue, N-Acetyl-L-Tyrosine (Sigma), failed to yield any detectable electron density for tyrosine in the distal site. Furthermore, titration of tyrosine, isoleucine, and alanine into cPAH by ITC did not reveal any binding event (Supporting Figure S8). These results indicate the distal site binds phenylalanine with some selectivity.

Catalytic Properties of the distal and active site mutants

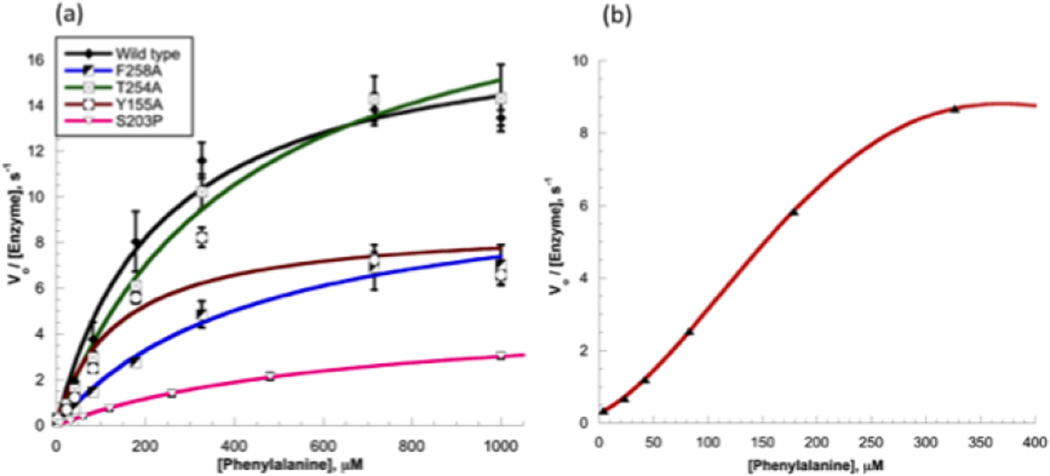

In order to determine the role of the distal phenylalanine binding site in cPAH, kinetic analyses of the distal site mutants were carried out under steady-state conditions. Enzymatic activities of cPAH and its mutants were investigated by holding oxygen and DMPH4 at saturation while varying the concentration of phenylalanine. The kinetic results for distal site mutants alongside wild type cPAH are summarized in Table 5. T254A showing close to 15-fold loss in binding according to ITC, displays somewhat similar catalytic activity as the wild type, although the fact that it is somewhat less active than the wild type is clearly discernible under low substrate concentrations. The two other mutants, Y155A and F258A, show more substantial loss in catalytic efficiency than the wild-type enzyme. The effect of the distal site mutation on the second-order rate constants kcat/KM shows that the mutants are noticeably less effective catalysts than the wild type protein (Table 5). The kcat/KM values reported in Table 5 were extracted from the slopes of the linear portion of the initial velocity vs. [substrate] plots. Under low substrate concentrations, the slope divided by the total enzyme concentration provides a measure of kcat/KM. Since the plots show departure from Michaelis-Menten behavior at relatively high concentration of the substrate, extraction of kcat/KM this way is likely to provide a better representation of the catalytic efficiency of the enzymes under sub-saturating substrate concentrations. While the mutations do not seem to have a dramatic effect on activity, there seems to be a trend among the mutants: the more severely impaired binder (via ITC analysis, Table 3) shows more noticeable loss in catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM). This trend was reproduced in three different measurements (the errors are shown in Figures 7A–B). However, due to the modest trend observed in the distal mutants, it is unclear from the kinetic data alone if the distal site has any regulatory role on catalytic turnover. Perhaps we must depart from steady-state kinetics to answer this question. We observed no noticeable changes in the position of residues within the active site region in the crystal structures of the distal mutants Y155A and F258A. It is possible that the mutations may have altered dynamic properties of the active site in solution leading to altered catalysis, effects that cannot be seen in the X-ray structures, which represent snapshots of the thermodynamically most stable form of the proteins.

Figure 7.

Initial velocity (divided by total enzyme concentration) as a function of substrate concentration from three independent experiments (a) in wild type cPAH and three distal site mutants, Y155A, T254A, and F258A provides evidence that mutation in the distal site leads to a noticeable loss in catalytic activity at each concentration of substrate examined. Also shown in the plot is initial velocity as a function of substrate concentration for the active site mutant studied, S203P, which shows the greatest loss in catalytic activity of all mutants under investigation. (b) A plot of initial velocity vs. phenylalanine concentration from Y155A shows sigmoidal dependence of rate with substrate concentration.

Dynamics effects of the distal site binding probed by molecular dynamics simulations

To test whether the distal and active site are linked dynamically, molecular dynamic simulations were carried out at on a 1 µs time scale (see Experimental). Our data does not establish a dynamic link between the two sites, as no significant changes in active site structure and dynamics were observed upon Phe binding. However, upon comparison of B-factors from the three models under study, it is clear that the phenylalanine-bound complex is significantly more rigid than the two phenylalanine-less models (Figures 8A–B). Furthermore, we observe a second conformational state for residues around the distal Phe binding site. Whilst an extension of the native α helix to a 310 helix for residues 247–249 is not observed in the simulation of cPAH with bound Phe, we see this transition for both simulations with vacant remote site multiple times over the simulation time of 1 µs (occupancy 310 helix 22% and 44% respectively). Based on these observations, it is plausible that phenylalanine binding in the distal site is important for stabilizing cPAH in catalytically competent states by limiting dynamic excursions into unproductive states (see the discussion below).

Discussion

Most enzymes have evolved to have their active sites adorned with residues for optimal substrate binding. Having an additional site usually serves to regulate the enzyme, most commonly seen in multimeric allosteric enzymes. Although the exact role of cPAH in Chromobacterium violaceum is not known, the fact that it catalyzes the conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine, two vital primary metabolites, and that the conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine is essentially irreversible, warrants that this enzyme, like its mammalian counterparts, should be regulated. It is conceivable that at low concentrations of phenylalanine, conditions that may arise when the free-living organism is exposed to nutrient starvation, it would be counterproductive to have the cPAH route to tyrosine continue, because this may deplete the phenylalanine pool in the organism. When the concentration of phenylalanine rises, the distal site effect would ‘activate’ the enzyme (see below) producing a feed-forward effect, known in the mammalian systems. In light of a recent publication which indicates that phenylalanine can form ordered amyloid fibrils (Adler-Abramovich 2012), another possible role for cPAH could be to prevent fibril formation in the organism by converting phenylalanine to tyrosine. Perhaps binding in the distal site could activate the protein under these circumstances. The genome of Chromobacterium violaceum has been sequenced (Vasconcelos et al. 2003). As is generally true of other free-living organisms, a striking aspect of this organism is that it can thrive under dramatically fluctuating environmental conditions. Consistent with this behavior, a significant portion of its genome is dedicated to open reading frames that can appropriately respond to change in conditions such as nutrient starvation (Vasconcelos et al. 2003). It is tempting to speculate that having a separate binding site for the substrate in an enzyme involved in amino acid metabolism could confer some advantages enabling the organism to reprogram its biosynthetic machinery.

Since it has been established that hPAH is subject to allosteric activation by its effector, phenylalanine, it is natural to question whether the distal binding pocket of cPAH is also a site for allosteric regulation. Although it is not implausible to find allosteric sites in single domain proteins (Hardy and Wells 2004); the distal binding site we have uncovered does not really qualify for an allosteric site in the conventional sense since we do not observe conformational coupling between this and the active site. Superposition of the apo and phenylalanine-bound structures have nearly identical positions of side chains that connect the two sites, indicating lack of conformational cross talk between the two (Figure 3C). However, we cannot discount the idea that allostery can occur without conformational changes in the backbone, and that it may instead transpire from changes in dynamics (Cooper and Dryden 1984; Tsai et al. 2008; Tzeng and Kalodimos 2011). It is possible that cPAH in solution samples an ensemble of distinct conformations, some of which are productive and some are not. Binding of phenylalanine at the distal site may limit the ensemble in such a way that the enzyme on an average spends more time with its active site in the productive form. This is one of the ways whereby the distal site may contribute to catalysis through positive regulation. The observation of neighboring side chains readjusting in the Y155A mutant is consistent with the dynamic nature of the enzyme. Our MD simulation analysis, while not showing any conformational coupling between the distal site and the active site, does provide some evidence of rigidification upon substrate binding at the distal site, based on which we propose distal Phe binding as a potential mechanism to lock cPAH in a catalytic active conformation.

The distal site may also serve to negatively regulate the enzyme under conditions of low substrate concentration. Under limiting substrate conditions, one would expect the rate of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction to be reduced if a second binding site exists, by a factor corresponding to the fractional occupancy at the two sites. We do not know the relative affinity of the distal site for phenylalanine compared to that of the active site. Therefore, the extent to which the rate would be reduced cannot be estimated. Nevertheless, the fact that there is another site for substrate binding would in effect cause an apparent inhibition of the enzyme under conditions in which the concentration of phenylalanine is low in solution: a condition that would arise when the free-living bacterium is exposed to nutrient starvation. This type of inhibition would prevent conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine thereby preventing a depletion of the phenylalanine pool in the organism under such conditions. Recently, the crystal structure of another bacterial PAH, a single domain monomeric protein similar to cPAH, was reported. The crystal structure of this PAH is similar to that of cPAH, but kinetic study revealed that the enzyme appears to exhibit sigmoidal dependence of rate with substrate concentration (Leiros et al. 2007), a hallmark of multimeric allosteric enzymes. Based on this, the authors suspected the presence of a “long-lived dead-end complex of the substrate with the enzyme (Leiros et al. 2007)”. It is tempting to link that observation to the crystallographic observation we are reporting. Such a behavior may be explained by invoking a second binding mode, presumably at a second binding site distinct from the active site.

We noticed discernible sigmoidal character of the velocity vs. substrate concentration plot in the case of Y155A (Figure 8B). However, it is not clear why we are not observing a sigmoidal plot in kinetics with the other mutants studied and wild type cPAH. It is possible that our experimental conditions preclude us from observing any type of cooperativity existing in these systems.

Although more work remains to be done to establish the link between the distal site and enzymatic regulation, we believe the data presented here makes a number of important points. First, our study represents the first such work characterizing the binding of the natural substrate phenylalanine to any PAH. Secondly, it reveals the unexpected presence of another substrate binding site in a single-domain enzyme. The relevance of this work may be farther-reaching than PAH itself. Enzymes like PAH, which are involved in primary metabolism have to be regulated, either in mammalian or bacterial organisms. However, the bacterial genome tends to be simple, with many of their enzymes lacking sophistication in terms of having extra domains for regulatory binding effects; yet, they have the same need for regulation. If more and more metabolic enzymes from bacterial sources are crystallograpically characterized bound to their natural substrate, we may be able to determine how common is the presence of such additional binding sites.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our hosts Michael Becker, Craig Ogata, Nukri Sanishvili, and Nagarajan Venugopalan at the GM/CA CAT beamline 23-ID-D at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Julian E. Fuchs is a recipient of a DOC fellowship of the Austrian Academy of Sciences at University of Innsbruck. The authors acknowledge the platform High Performance Computing at University of Innsbruck for providing computer hardware resources for this project.

This research was funded by the National Science Foundation (CHE-0749572 to M.M.A.O.) and the National Institutes of Health (1R01RR026273 to C.D.)

Abbreviations

- PAH

phenylalanine hydroxylase

- BH4

(6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin dihydrochloride

- PKU

Phenylketonuria

- cPAH

phenylalanine hydroxylase from Chromobacterium violaceum

- hPAH

human phenylalanine hydroxylase

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- THA

3-(2-thienyl)-L-alanine

- NLE

L-norleucine

- Fe

Iron

- Co

Cobalt

- DMPH4

6,7-Dimethyltetrahydropterin

Contributor Information

Judith A. Ronau, Email: jronau@purdue.edu.

Lake N. Paul, Email: lpaul@purdue.edu.

Julian E. Fuchs, Email: Julian.Fuchs@uibk.ac.at.

Isaac R. Corn, Email: icorn@purdue.edu.

Kyle T. Wagner, Email: ktwagner@purdue.edu.

Klaus R. Liedl, Email: Klaus.Liedl@uibk.ac.at.

Mahdi M. Abu-Omar, Email: mabuomar@purdue.edu.

Chittaranjan Das, Email: cdas@purdue.edu.

References

- 1.Abu-Omar MM, Loaiza A, Hontzeas N. Reaction mechanisms of mononuclear non-heme iron oxygenases. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2227–2252. doi: 10.1021/cr040653o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adler-Abramovich L, Vaks L, Carny O, Trudler D, Magno A, Caflisch A, Frenkel D, Gazit E. Phenylalanine assembly into toxic fibrils suggests amyloid etiology in phenylketonuria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2012;8:701–706. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen OA, Flatmark T, Hough E. Crystal structure of the ternary complex of the catalytic domain of human phenylalanine hydroxylase with tetrahydrobiopterin and 3-(2-thienyl)-L-alanine, and its implications for the mechanism of catalysis and substrate activation. J Mol Biol. 2002;320:1095–108. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00560-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen OA, Stokka AJ, Flatmark T, Hough E. 2.0 Ǻ Resolution Crystal Structures of the Ternary Complexes of Human Phenylalanine Hydroxylase Catalytic Domain with Tetrahydrobiopterin and 3-(2-Thienyl)-L-alanine or L-Norleucine: Substrate Specificity and Molecular Motions Related to Substrate Binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell WD, Kollman PA. A Well-Behaved Electrostatic Potential Based Method Using Charge Restraints for Deriving Atomic Charges: The RESP Model. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broecker J, Vargas C, Keller S. Revisiting the optimal c value for isothermal titration calorimetry. Anal. Biochem. 2011;418:307–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TE, III, Simmerling CL, Wang RE, et al. AMBER12. San Francisco: University of California; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chehin R, Thorolfsson M, Knappskog PM, Martinez A, Flatmark T, Arrondo JL, Muga A. Domain structure and stability of human phenylalanine hydroxylase inferred from infrared spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1998;422:225–30. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01596-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Citron BA, Davis MD, Kaufman S. Purification and biochemical characterization of recombinant rat liver phenylalanine hydroxylase produced in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 1992;3:93–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper A, Dryden DTF. Allostery without conformational change: A plausible model. European Biophysics Journal. 1984;11:103–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00276625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daubner SC, Hillas PJ, Fitzpatrick P. Characterization of chimeric pterin-dependent hydroxylases: contributions of the regulatory domains of tyrosine and phenylalanine hydroxylase to substrate specificity. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11574–115782. doi: 10.1021/bi9711137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erlandsen H, Kim JY, Patch MG, Han A, Volner A, Abu-Omar MM, Stevens RC. Structural Comparison of Bacterial and Human Iron-dependent Phenylalanine Hydroxylases: Similar Fold, Different Stability and Reaction Rates. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320:645–661. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erlandsen H, Patch MG, Gamez A, Straub M, Stevens RC. Structural studies on phenylalanine hydroxylase and implications toward understanding and treating phenylketonuria. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1557–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzpatrick PF. Tetrahydropterin-Dependent Amino Acid Hydroxylases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:355–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzpatrick PF. Mechanism of aromatic amino acid hydroxylation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:14083–14091. doi: 10.1021/bi035656u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzpatrick PF. Allosteric regulation of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;519:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flatmark T, Stevens RC. Structural Insight into the Aromatic Amino Acid Hydroxylases and Their Disease-Related Mutant Forms. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2137–2160. doi: 10.1021/cr980450y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flydal MI, Mohn TC, Pey AL, Siltberg-Liberles J, Teigen K, Martinez A. Superstoichiometric binding of L-Phe to phenylalanine hydroxylase from Caenorhabditis elegans: evolutionary implications. Amino Acids. 2010;39:1463–1475. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuchs JE, Huber RG, von Grufenstein S, Wallnoefer HG, Spitzer GM, Fuchs D, Liedl KR. Dynamic Regulation of Phenylalanine Hydroxylase by Simulated Redox Manipulation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e53005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fusetti F, Erlandsen H, Flatmark T, Stevens RC. Structure of tetrameric human phenylalanine hydroxylase and its implications for phenylketonuria. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:16962–16967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gjetting T, Petersen M, Guldberg P, Guttler F. Missense Mutations in the N-Terminal Domain of Phenylalanine Hydroxylase Interfere with Binding of Regulatory Phenylalanine. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:1353–1360. doi: 10.1086/320604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goetz AW, Williamson MJ, Xu D, Poole D, Le Grand S, et al. Routine microsecond molecular dynamics with AMBER – Part I: Generalized Born. J. Chem. Thoery Comput. 2012;8(5):1542–1555. doi: 10.1021/ct200909j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardy JA, Wells JA. Searching for new allosteric sites in enzymes. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:706–15. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrmann KM. The Shikimate Pathway: Early Steps in the Biosynthesis of Aromatic Compounds. Plant Cell. 1995;7:907–919. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.7.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horne J, Jennings IG, Teh T, Gooley PR, Kobe B. Structural characterization of the N-terminal autoregulatory sequence of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2041–7. doi: 10.1110/ps.4560102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houtman JC, Brown PH, Bowden B, Yamaguchi H, Appella E, Samelson LE, Schuck P. Studying multisite binary and ternary protein interactions by global analysis of isothermal titration calorimetry data in SEDPHAT: application to adaptor protein complexes in cell signaling. Protein Sci. 2007;16:30–42. doi: 10.1110/ps.062558507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kappock TJ, Cardonna JP. Pterin-dependent amino acid hydroxylases. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2659–2756. doi: 10.1021/cr9402034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaufman S. The phenylalanine hydroxylating system. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1993;67:77–264. doi: 10.1002/9780470123133.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knappskog PM, Flatmark T, Aarden JM, Haavik J, Martinez A. Structure/function relationships in human phenylalanine hydroxylase. Effect of terminal deletions on the oligomerization, activation and cooperativity of substrate binding to the enzyme. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:813–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0813r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobe B, Jennings IG, House CM, Michell BJ, Goodwill KE, Santarsiero BD, Stevens RC, Cotton RGH, Kemp BE. Structural basis of autoregulation of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:442–448. doi: 10.1038/8247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Labute P. Protonate 3D: Assignment of Ionization States and Hydrogen Coordinates to Macromolecular Structures. Proteins. 2009;75(1):187–205. doi: 10.1002/prot.22234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leiros H-KS, Pey AL, Innselset M, Moe E, Leiros I, Steen IH, Martinez A. Structure of Phenylalanine Hydroxylase from Colwellia psychrerythraea 34H, a Monomeric Cold Active Enzyme with Local Flexibility around the Active Site and High Overall Stability. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21973–21986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Ilangovan U, Daubner SC, Hinck AP, Fitzpatrick PF. Direct evidence for a phenylalanine site in the regulatory domain of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2011;505:250–255. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Palmo K, Maragakis P, Dror RO, et al. Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins. 2010;78(8):1950–1958. doi: 10.1002/prot.22711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loaiza A, Armstrong KM, Baker BM, Abu-Omar MM. Kinetics of thermal unfolding of phenylalanine hydroxylase variants containing different metal cofactors (FeII, CoII, and ZnII) and their isokinetic relationship. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:4877–83. doi: 10.1021/ic800181q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayers JR, Fyfe I, Schuh AL, Chapman ER, Edwardson JM, Audhya A. ESCRT-0 assembles as a heterotetrameric complex on membranes and binds multiple ubiquitinylated cargoes simultaneously. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9636–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.185363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:355–67. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. In: Otwinowski Z, Minor W, editors; Carter CW Jr, Sweet RM, editors. Methods in Enzymology, Macromolecular Crystallography, Part A. Vol. 276. New York: Academic Press; 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Painter J, Merritt EA. Optimal description of a protein structure in terms of multiple groups undergoing TLS motion. Acta Cryst. D. 2006;62:439–450. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906005270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parniak MA, Kaufman S. Rat liver phenylalanine hydroxylase. Activation by sulfhydryl modification. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:6876–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phillips RS, Parniak MA, Kaufman S. The interaction of aromatic amino acids with rat liver phenylalanine hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:271–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4. Schrödinger, LLC; [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scriver CR. Whatever happened to PKU? Clin Biochem. 1995;28:137–44. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(94)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh B. In: Plant amino acids: biochemistry and biotechnology. Singh K, editor. New York: Marcel Dekker Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsai C-J, Sol Ad, Nussinov R. Allostery: Absence of a Change in Shape Does Not Imply that Allostery Is Not at Play. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;378:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tzeng SR, Kalodimos CG. Protein dynamics and allostery: an NMR view. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:62–7. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasconcelos AT, Almeida DF, Hungria M, Guimarães CT, Antônio RV, et al. The complete genome sequence of Chromobacterium violaceum reveals remarkable and exploitable bacterial adaptability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11660–11665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832124100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an Automated Program for Molecular Replacement. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 1997;30:1022–1025. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Volner A, Zoidakis J, Abu-Omar MM. Order of substrate binding in bacterial phenylalanine hydroxylase and its mechanistic implication for pterin-dependent oxygenases. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2003;8:121–128. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wallnoefer HG, Handschuh S, Liedl KR, Fox T. Stabilizing of a Globular Protein by a Highly Complex Water Network: A Molecular Dynamics Study on Factor Xa. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:7405–7412. doi: 10.1021/jp101654g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zoidakis J, Loaiza A, Vu K, Abu-Omar MM. Effect of temperature, pH, metals on the stability and activity of phenylalanine hydroxylase from Chromobacterium violaceum. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005;99(3):771–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.