Abstract

LodA is a novel lysine-ε-oxidase which possesses a cysteine tryptophylquinone cofactor. It is the first tryptophylquinone enzyme known to function as an oxidase. A steady-state kinetic analysis shows that LodA obeys a ping-pong kinetic mechanism with values of kcat of 0.22±0.04 s−1, Klysine of 3.2±0.5 µM and KO2 of 37.2±6.1 µM. The kcat exhibited a pH optimum at 7.5 while kcat/Klysine peaked at 7.0 and remained constant to pH 8.5. Alternative electron acceptors could not effectively substitute for O2 in the reaction. A mechanism for the reductive half reaction of LodA is proposed that is consistent with the ping-pong kinetics.

Keywords: Amine oxidase, cofactor, quinoprotein, lysine oxidase, redox enzyme

1. Introduction

LodA is a novel lysine-ε-oxidase which was recently found in the melanogenic marine bacterium, Marinomonas mediterranea [1–3]. This enzyme was originally called marinocine but is now referred to as LodA, the gene product of lodA. LodA exhibits antimicrobial properties in vivo that result from its production of H2O2. It is secreted to the external medium in the biofilms in which the bacterium resides. This causes death of a subpopulation of cells within the M. mediterranea biofilm that is accompanied with differentiation, dispersal and phenotypic variation among dispersal cells [4].

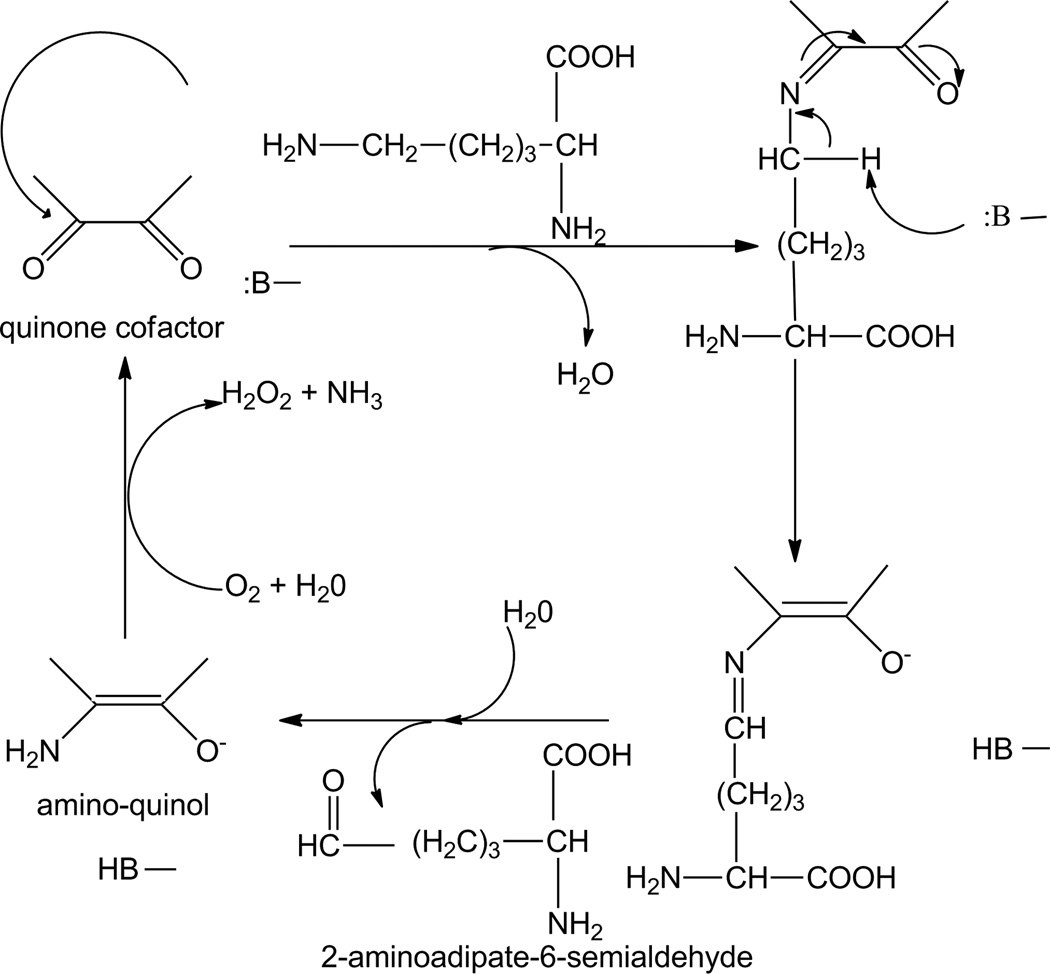

Typical amino acid oxidases utilize a flavin cofactor for catalysis and act upon the α-amino group. LodA removes the ε-amino group of lysine and the recent crystal structure of LodA reveals that it contains a cysteine tryptophylquinone (CTQ, Figure 1) cofactor [5]. CTQ is a protein-derived cofactor [6], which is generated by the posttranslational modification of cysteine 516 and tryptophan 581 of LodA. Analysis of LodA by mass spectrometry yields a molecular mass that is also consistent with the presence of CTQ [7]. Another protein, LodB, is required for the posttranslational formation of CTQ [7,8]. All other tryptophylquinone cofactor-containing enzymes are dehydrogenases that use other redox proteins as their electron acceptors [9]; this is the first time that one has been shown to function as an oxidase. The best known tryptophylquinone enzymes possess tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ, Fig. 1) where the modified Trp is cross-linked to another Trp rather than a Cys [10]. The known TTQ enzymes are primary amine dehydrogenases [6,11]. The one other CTQ-dependent enzyme that has been characterized is a quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase (QHNDH) which possesses two covalently attached hemes in addition to CTQ [12,13].

Figure 1.

Tryptophylquine cofactors that are formed by posttranslational modifications. CTQ is cysteine tryptophylquinone. TTQ is tryptophan tryptophylquinone. TPQ is 2,4,5-trihydroxyphenylalanine quinone or topaquinone. LTQ is lysine tryptophylquinone.

Another class of protein-derived cofactors that contain quinones derived from Tyr residues has been identified [14]. These possess the topaquinone (TPQ, Fig. 1) cofactor and are found only in primary amine oxidases. In each case, these enzymes also possess a tightly bound copper in the active site which is required for biogenesis of the cofactor and subsequently participates in catalysis. A related cofactor is lysine tyrosylquinone (LTQ) which is the catalytic center of mammalian lysyl oxidase [15]. This enzyme is also a lysine ε-oxidase but it acts only on lysyl residues of a protein substrate rather than free lysine [16]. Like the TPQ-dependent enzymes, lysyl oxidase also possesses a tightly-bound copper in the active site [17]. LodA is the first example of an amino acid or primary amine oxidase that contains neither a flavin nor a metal at its active site.

This paper presents a steady-state kinetic analysis of the reaction that is catalyzed by LodA (eq 1) to determine its steady-state reaction mechanism and kinetic parameters. The results are used to propose a reaction mechanism which is consistent with the crystal structures of a lysine-bound adduct of LodA [5].

| (1) |

2. Materials and Methods

Recombinant LodA was expressed in E.coli Rosetta cells which had been transformed with pET15LODAB [7] which contains lodA with an attached 6xHis tag and lodB which is required for the posttranslational modification of LodA that forms CTQ. The cells were cultured in LB media with ampicillin and chloramphenicol. Expression levels of active LodA are very sensitive to induction conditions and previously determined optimal conditions [7] were followed. When the absorbance of the culture reached a value of 0.6, the temperature was decreased to15 °C and cells were induced by addition of 1 mM IPTG. Cells were harvested after 2 hr and then broken by sonication in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (KPi), pH7.5. The soluble extract was applied to a Nickel-NTA affinity column and the His-tagged LodA was eluted using 100–120 mM imidazole in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5. LodA was then further purified by ion exchange chromatography with DEAE cellulose in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5. The His-tagged LodA bound to the resin and was eluted using 180–270 mM NaCl in the same buffer. The protein was judged pure by SDS-PAGE and its UV-visible absorption spectrum exhibited a broad peak centered at 400 nm with an absorbance at 400 nm which was about 13-fold less intense than the absorbance at 280 nm. Methylamine dehydrogenase (MADH) [18], amicyanin [19] and cytochrome c-550 [20] were purified from Paracoccus denitrificans as described previously.

LodA activity had previously been assayed using a standard coupled assay for oxidases in which horseradish peroxidase (HRP) is also present and uses the H2O2 product of the oxidase reaction to oxidize Amplex Red to resorufin which leads to a change in fluorescence [21]. This assay was modified to instead follow the change in absorbance associated with production of resorufin which has an extinction coefficient at of 54000 M−1 cm−1 at its absorbance maximum of 570 nm. The assay mixture contained 0.05 mM Amplex Red, 0.1U/ml of HRP and 0.4 µM LodA in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5 at 25 °C. The concentration of LodA was determined using an ε280=125,180 M−1cm−1 which was calculated from its amino acid sequence [22]. Experiments were performed in which [lysine] was varied in the presence of fixed concentrations [O2] and vice versa. To vary the concentration of O2, an appropriate amount of a stock solution of air-saturated buffer ([O2]=252 µM) was mixed with the reaction mixture which had been made anaerobic by repeated cycles of vacuum and purging with argon. The reactions were initiated by the addition of lysine. In order to account for a small background reaction in which Amplex Red is spontaneously converted to resorufin, control experiments were performed in the absence of LodA to determine the background rate which was subtracted from the experimentally-determined LodA-dependent reaction rates. The reaction was also assayed by monitoring the release of the ammonia product using a coupled assay. The assay mixture contained 20 U/ml glutamate dehydrogenase, 5 mM α-ketoglutarate, 0.4 µM LodA and 93.7 µM NADH in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5 at 25 °C and the reactions were initiated by the addition of lysine. In assays to test the reactivity of artificial electron acceptors the assay mixture contained 0.4 µM LodA in 50 mM KPi, pH 7.5 at 25 °C under anaerobic conditions. The reaction was initiated by addition of lysine and monitored by the spectral change associated with the reduction of each electron acceptor, phenazine ethosulfate (PES) plus 2,6-dichloroinophenol (DCIP) (ε600=21,500 M−1cm−1), ferricyanide (ε420=1,040 M−1cm−1), or NAD+ (ε340=6,220 M−1cm−1), amicyanin (ε595=4,600 M−1cm−1), cytochrome c-550 (ε550=30,200 M−1cm−1).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Steady-state reaction mechanism and parameters

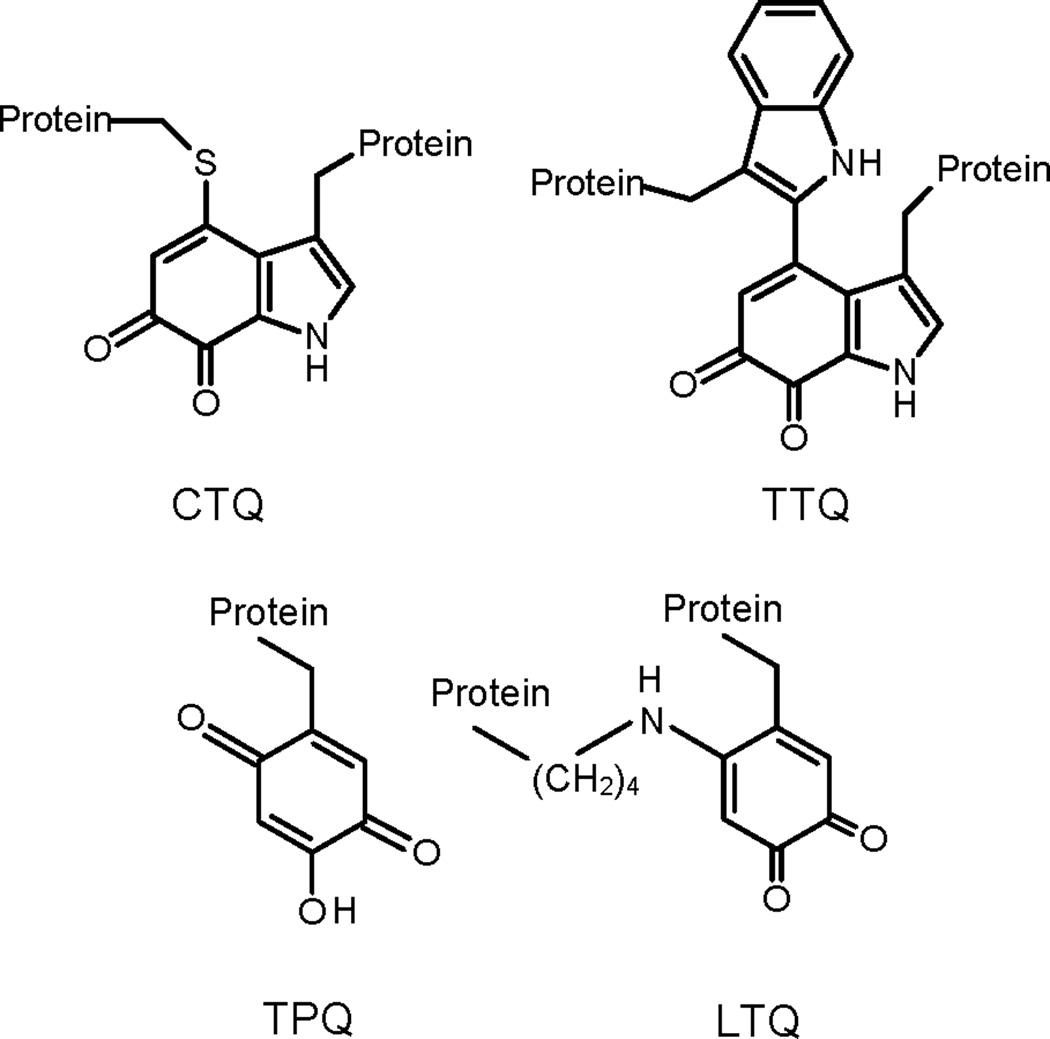

Steady-state assays of lysine oxidation by LodA were performed in order to determine the kinetic mechanism of this reaction and the kinetic parameters that describe this reaction. The initial rates of reaction were determined at different concentrations of lysine in the presence of a set of fixed concentrations of O2 (Fig. 2A). Double reciprocal plots of these data exhibited a set of lines which are clearly more parallel than intersecting (Fig. 2B). Similarly, when the initial rates of reaction were determined at different concentrations of O2 in the presence of a set of fixed concentrations of lysine a set of parallel lines was obtained in the reciprocal plots. These data are consistent with a ping-pong kinetic mechanism rather than an ordered or random sequential mechanism and thus the reaction is described by eq 2 [23]. Secondary plots of the intercept (1/kcat apparent) versus 1/[O2] (Fig. 2C), intercept/slope (1/Klysine apparent) versus 1/[O2] (Fig. 2D), intercept (1/kcat apparent) versus 1/[lysine] (Fig. 2E) and intercept/slope (1/KO2 apparent) versus 1/[lysine] (Fig. 2E) were each linear. These plots are described by eqs 3 and 4 [23] where A is the varied substrate and B is the fixed substrate. Analysis of these data yielded values of kcat of 0.22±0.04 s−1, Klysine of 3.2±0.5 µM and KO2 of 37.2±6.1 µM.

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Figure 2.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of LodA. A. Initial rates were determined at different concentrations of lysine in the presence of a fixed concentration of 252 (○), 129 (♦), 54 (▼), 11 (▲) or 5 (●) µM O2. B. Double reciprocal plot of the data shown in panel A. C. Secondary plots of the y-intercept (1/apparent kcat) from panel B versus 1/[O2]. Data are fit by eq 3. D. Secondary plots of the y-intercept/slope (1/apparent Klysine) from panel B versus 1/[O2]. Data are fit by eq 4. E. Secondary plots of the y-intercept (1/apparent kcat) from plots of v/E versus [O2] against 1/[lysine]. Data are fit by eq 3. F. Secondary plots of the y-intercept/slope (1/apparent KO2) from plots of v/E versus [O2] against 1/[lysine]. Data are fit by eq 4. Error bars are indicated in the secondary plots (C–F).

This reaction was also studied using another coupled enzyme assay in which the rate of formation of the ammonia product was coupled to NADH oxidation by glutamate dehydrogenase in the presence of α-ketoglutarate. When the assay was performed using saturating concentrations of 100 µM lysine and 252 µM O2 the rate of reaction was 0.25±0.07 s−1 which is within experimental error of the kcat value obtained in the assay which monitored H2O2 production.

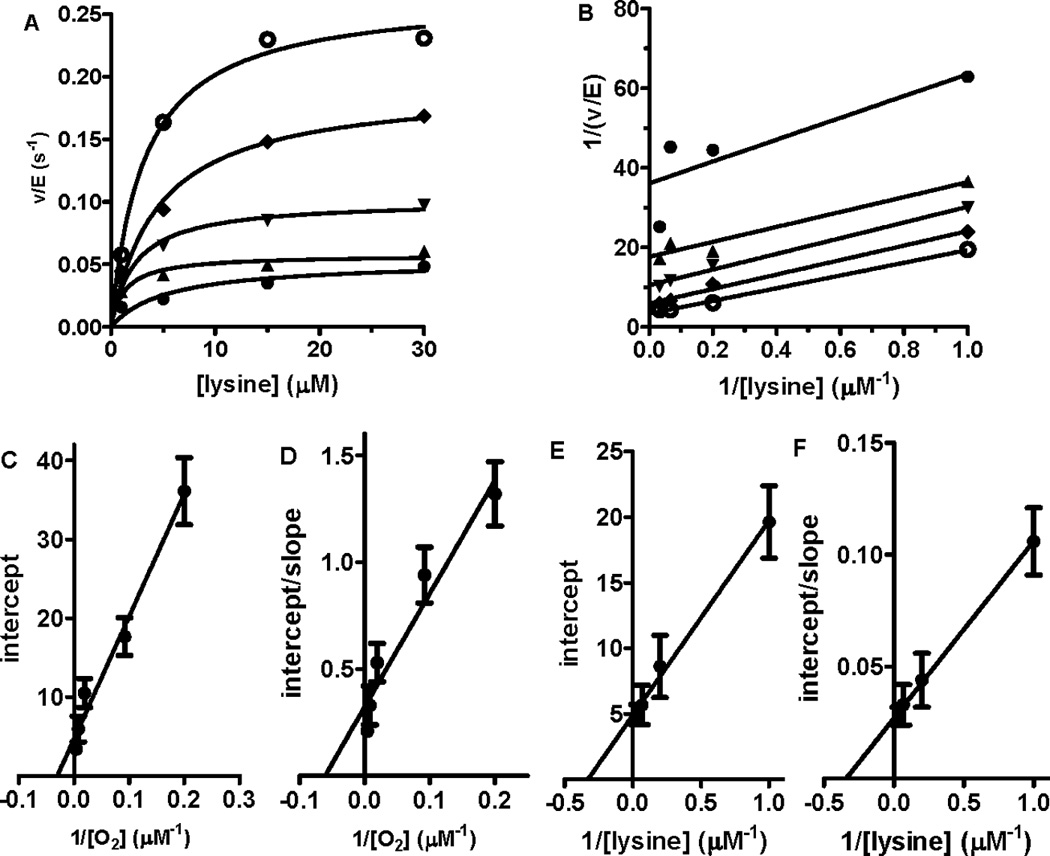

3.2. Dependence of LodA activity on pH

The pH dependence of kcat and kcat/Km for lysine were determined at 252 µM O2 (Fig. 3). The kcat value exhibited a bell-shaped pH profile with a maximum at pH 7.5. This suggests that there are at least two residues that are required and that one must be protonated and the other must be unprotonated for catalysis. In contrast the kcat/Km values reached a maximum at pH 7.0 and stayed relatively constant up to pH 8.5. Thus, the catalytic efficiency of LodA is retained at the higher pH as a consequence of a decrease in Klysine.

Figure 3.

Dependence on pH of kcat (A) and kcat/Km for lysine at saturating concentration of O2. Error bars are indicated.

3.3. Reactivity towards alternative electron acceptors

The distinguishing property between an oxidase and a dehydrogenase is that the oxidases use O2 as their final electron acceptor whereas dehydrogenases use other redox proteins or non-protein electron acceptors other than O2. Since all other know tryptophylquinone enzymes are dehydrogenases the ability of LodA to function as a dehydrogenase was tested using alternative electron acceptors. The most widely used assay for quinoprotein dehydrogenases uses PES coupled to DCIP. For comparison the assay was also performed on MADH which possesses the TTQ cofactor. When assayed in the presence of saturating methylamine with 5 mM PES and 100 µM DCIP MADH exhibited a rate of 36 s−1 while LodA when assayed in the presence of saturating lysine under these conditions exhibited a rate of 0.06 s−1. Another commonly used artificial electron acceptor is ferricyanide. When similarly assayed in the presence of 1 mM potassium ferricyanide with saturating lysine LodA exhibited a rate of 0.10 s−1. For a more direct comparison of the efficiency of the artificial electron acceptors, the assays were repeated using 252 µM PES or ferricyanide, a concentration equivalent to that used for O2 (KO2 = 37.2±6.1 µM). At this concentration the rates with PES/DCIP and ferricyanide were each 0.01 s−1 which is barely above background, compared 0.22±0.04 s−1 for O2. NAD+ (1 mM) was also tested in the presence of 100 µM lysine and no detectable reaction was observed. Two protein electron acceptors were also tested. The copper protein amicyanin [19] is the natural electron acceptor for MADH. In the steady state reaction of methylamine dependent amicyanin reduction by MADH, amicyanin exhibits a kcat of 48 s−1 and Km of 6 µM [24]. When LodA was assayed with 100 µM amicyanin and saturating lysine the rate was only 0.008 s−1. Cytochrome c-550 from P. denitrificans is a relatively promiscuous electron acceptor that shares structural features with many bacterial and mammalian cytochromes c [25]. When LodA was assayed with 100 µM cytochrome and saturating lysine the rate was 0.002 s−1.

One cannot rule out the possibility that in vivo there is an unidentified redox-active molecule or protein that could serve as an electron acceptor for LodA instead of O2. However, no significant dehydrogenase activity of LodA could be detected in this study. These results support the proposal that the generation of H2O2 and consequent antimicrobial activity [1] is the main physiological function of LodA, which is secreted from cell to perform this function.

3.4. Proposed mechanism

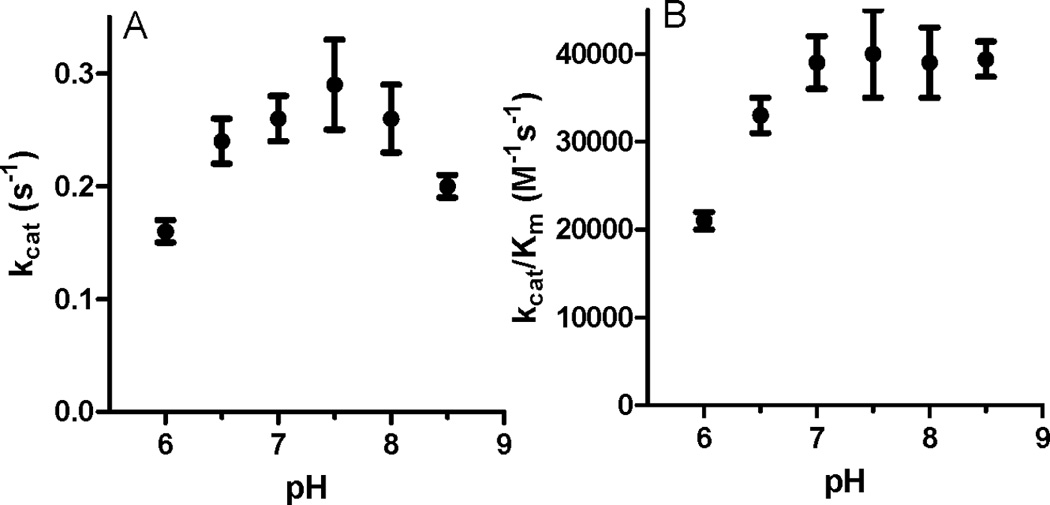

The ping-pong kinetic mechanism requires that an intermediate form of the enzyme exist after binding of substrate and release of the first product prior to binding of the second substrate. This finding is consistent with the reported crystal structure of LodA with a covalent lysine adduct with CTQ [5] and suggests the following reaction mechanism (Fig. 4). The ε-amino group of lysine must first be deprotonated, likely by an active site residue, so that the resulting nucleophilic NH2 group can attack the electrophilic carbonyl carbon to displace the bound oxygen and yield a Schiff base intermediate, as seen in the crystal structure. An active site residue then abstracts a proton from the ε-carbon reducing the cofactor and resulting in the Schiff base now involving the ε-carbon. Inspection of the crystal structure of the LodA-lysine adduct [5] reveals that the S of Cys448 is approximately 5.5 Å from this carbon and could possibly be involved in this step. This covalent adduct is then hydrolyzed to release the aldehyde product prior to O2 binding. This yields an aminoquinol intermediate form of the enzyme consistent with a ping-pong mechanism. This proposed mechanism for this reductive half-reaction is essentially identical to those of QHNDH [26] and MADH [24], which possess CTQ and TTQ, respectively. It is also the same mechanism proposed in the reductive half-reactions of the TPQ-dependent amine oxidases [27]. With the TTQ-dependent MADH it was shown that the ammonia product was not released until after the quinol was oxidized to the quinone by its electron acceptor, and that in the steady-state this occurred by displacement of the amino group from the cofactor by the next amine substrate molecule [26]. This may be true for LodA as well. Alternatively, it could be hydrolyzed by water. A key question which remains unanswered is how the quinol or aminoquinol in LodA is reoxidized by O2. In the TPQ-dependent oxidases Cu2+ is also present at the active site. It has been proposed that this interacts with the quinol intermediate to yield a Cu+-semiquinone intermediate which would allow reaction of the Cu+ with oxygen to generate a superoxide species in the first step of the reoxidation [28,29]. LodA, however, does not have a bound metal. Future characterization of the mechanism of the oxidative half-reaction of LodA should be of great interest.

Figure 4.

Proposed mechanism for LodA-catalyzed oxidative deamination of lysine. B represents an active site residue which participates in acid-base chemistry.

Highlights.

LodA has a tryptophylquinone cofactor but functions as an oxidase not a dehydrogenase

LodA exhibits a ping-pong kinetic mechanism with lysine and O2 as substrates

The kinetic mechanism of LodA is consistent with a covalent lysine-CTQ intermediate

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by internal funds from the Burnett School of Biomedical Sciences and in part the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R37GM41574 (V.L.D.), and grant BIO2010-15226 from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Spain (A.S.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lucas-Elio P, Gomez D, Solano F, Sanchez-Amat A. The antimicrobial activity of marinocine, synthesized by Marinomonas mediterranea, is due to hydrogen peroxide generated by its lysine oxidase activity. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:2493–2501. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2493-2501.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucas-Elio P, Hernandez P, Sanchez-Amat A, Solano F. Purification and partial characterization of marinocine, a new broad-spectrum antibacterial protein produced by Marinomonas mediterranea. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1721:193–203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molina-Quintero LR, Lucas-Elio P, Sanchez-Amat A. Regulation of the Marinomonas mediterranea antimicrobial protein lysine oxidase by L-lysine and the sensor histidine kinase PpoS. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6141–6149. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00690-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mai-Prochnow A, Lucas-Elio P, Egan S, Thomas T, Webb JS, Sanchez-Amat A, Kjelleberg S. Hydrogen peroxide linked to lysine oxidase activity facilitates biofilm differentiation and dispersal in several gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:5493–5501. doi: 10.1128/JB.00549-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okazaki S, Nakano S, Matsui D, Akaji S, Inagaki K, Asano Y. X-Ray crystallographic evidence for the presence of the cysteine tryptophylquinone cofactor in L-lysine epsilon-oxidase from Marinomonas mediterranea. J Biochem. 2013;154:233–236. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvt070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson VL. Generation of protein-derived redox cofactors by posttranslational modification. Mol. Biosyst. 2011;7:29–37. doi: 10.1039/c005311b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chacon-Verdu MD, Gomez D, Solano F, Lucas-Elio P, Sanchez-Amat A. LodB is required for the recombinant synthesis of the quinoprotein L-lysine-epsilon-oxidase from Marinomonas mediterranea. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez D, Lucas-Elio P, Solano F, Sanchez-Amat A. Both genes in the Marinomonas mediterranea lodAB operon are required for the expression of the antimicrobial protein lysine oxidase. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:462–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson VL. Structure and mechanism of tryptophylquinone enzymes. Bioorg Chem. 2005;33:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIntire WS, Wemmer DE, Chistoserdov A, Lidstrom ME. A new cofactor in a prokaryotic enzyme: tryptophan tryptophylquinone as the redox prosthetic group in methylamine dehydrogenase. Science. 1991;252:817–824. doi: 10.1126/science.2028257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davidson VL. Pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ) from methanol dehydrogenase and tryptophan tryptophylquinone (TTQ) from methylamine dehydrogenase. Adv. Protein Chem. 2001;58:95–140. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)58003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Datta S, et al. Structure of a quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase with an uncommon redox cofactor and highly unusual crosslinking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:14268–14273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241429098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoh A, et al. Crystal structure of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase from Pseudomonas putida - Identification of a novel quinone cofactor encaged by multiple thioether cross-bridges. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:2830–2834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mure M. Tyrosine-derived quinone cofactors. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:131–139. doi: 10.1021/ar9703342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang SX, et al. A crosslinked cofactor in lysyl oxidase: redox function for amino acid side chains. Science. 1996;273:1078–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagan HM, Li W. Lysyl oxidase: properties, specificity, and biological roles inside and outside of the cell. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003;88:660–672. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bollinger JA, Brown DE, Dooley DM. The formation of lysine tyrosylquinone (LTQ) is a self-processing reaction. Expression and characterization of a drosophila lysyl oxidase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11708–11714. doi: 10.1021/bi0504310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidson VL. Methylamine dehydrogenases from methylotrophic bacteria. Methods in Enzymology. 1990;188:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)88040-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Husain M, Davidson VL. An inducible periplasmic blue copper protein from Paracoccus denitrificans. Purification, properties, and physiological role. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:14626–14629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husain M, Davidson VL. Characterization of two inducible periplasmic c-type cytochromes from Paracoccus denitrificans. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261:8577–8580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gomez D, Lucas-Elio P, Sanchez-Amat A, Solano F. A novel type of lysine oxidase: L-lysine-epsilon-oxidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:1577–1585. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gill SC, von Hippel PH. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segal IH. Enzyme Kinetics. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1975. pp. 606–612. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks HB, Jones LH, Davidson VL. Deuterium kinetic isotope effect and stopped-flow kinetic studies of the quinoprotein methylamine dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2725–2729. doi: 10.1021/bi00061a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Timkovich R, Dickerson RE. The structure of Paracoccus denitrificans cytochrome c550. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:4033–4046. doi: 10.2210/pdb155c/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun D, Ono K, Okajima T, Tanizawa K, Uchida M, Yamamoto Y, Mathews FS, Davidson VL. Chemical and kinetic reaction mechanisms of quinohemoprotein amine dehydrogenase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10896–10903. doi: 10.1021/bi035062r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartmann C, Klinman JP. Structure-function studies of substrate oxidation by bovine serum amine oxidase: relationship to cofactor structure and mechanism. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4605–4611. doi: 10.1021/bi00232a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dooley DM, McGuirl MA, Brown DE, Turowski PN, McIntire WS, Knowles PF. A Cu(I)-semiquinone state in substrate-reduced amine oxidases. Nature. 1991;349:262–264. doi: 10.1038/349262a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee A, Smirnov VV, Lanci MP, Brown DE, Shepard EM, Dooley DM, Roth JP. Inner-sphere mechanism for molecular oxygen reduction catalyzed by copper amine oxidases. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9459–9473. doi: 10.1021/ja801378f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]