Abstract

In many species, there are antipredator benefits of grouping with conspecifics. For example, animals often aggregate to better avoid potential predators (the ‘avoidance hypothesis’). Animals also often group together in direct response to predators to facilitate escape (the ‘escape hypothesis’). The avoidance hypothesis predicts that animals with previous experience with predation risk will aggregate more than animals without experience with predation risk. In contrast, the escape hypothesis predicts that immediate exposure to predation risk causes animals to aggregate. We simultaneously tested these two nonexclusive hypotheses in threespine sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus. Schooling behaviour (time spent schooling, latency to school and time schooling in the middle of the school) was quantified with a mobile model school. Fish that had been chased by a model predator in the past schooled more, started schooling faster and spent a marginally greater proportion of time schooling in the middle of the school than fish that had not been chased. In contrast, there was no difference in the schooling behaviour of fish that were immediately exposed to either a model pike or a control, stick stimulus. A second experiment confirmed that fish perceived the model pike and stick differently: fish froze more often in the presence of the model pike, oriented to it more often and spent less time with the model pike than they did with the stick. These results provide strong support for the avoidance hypothesis.

Keywords: antipredator behaviour, avoidance hypothesis, escape hypothesis, Gasterosteus aculeatus, schooling behaviour, threespine stickleback

Defence against predators has played an important role in the evolution of social grouping in prey animals (Alexander 1974; Farr 1975; reviewed in Pulliam & Caraco 1984). A rich literature shows that the antipredator benefits of grouping can accrue during different stages of the predator–prey interaction sequence. For example, grouping can improve predator detection (i.e. ‘many eyes’; Pulliam 1973; Kenward 1978; Lima 1990; Magurran et al. 1985; Godin et al. 1988; Roberts 1996) and minimize an individual’s risk of predation via the dilution effect (Foster & Treherne 1981; Turner & Pitcher 1986; Inman & Krebs 1987). Grouping can also improve escape from predators via coordinated predator defence (Curio 1978; Pitcher 1983) or predator confusion (Neill & Cullen 1974). Confusion might occur via a variety of sensory modalities, including hearing (Larsson 2012), vision (Tosh et al. 2009), or disruption of predator fish lateral line or electrosensory systems (New et al. 2001; Larsson 2009).

These different mechanisms can be classified into two broad categories according to when the benefits of grouping accrue during the predator–prey interaction sequence. The first category includes benefits of grouping that occur prior to the initiation of a predator attack (e.g. detection). In those cases, the function of grouping is to avoid predators (the avoidance hypothesis). The second category includes benefits of grouping that occur in response to the immediate presence of a predator (e.g. predator confusion or coordinated swimming). In those cases, the function of grouping is to improve escape (the escape hypothesis). For finerscale descriptions of the predator–prey interaction sequence, see Lima & Dill (1990) and Kelley & Magurran (2003).

Although many studies have documented antipredator benefits of grouping in diverse taxa (birds: Kenward 1978; Roberts 1996; insects: Calvert et al. 1979; Foster & Treherne 1981; fish: Seghers 1974; Magurran 1986; mammals: Monaghan & Metcalfe 1985; Jarman 1987), few studies (Ostreiher 2003; Fairbanks & Dobson 2007; Beauchamp & Ruxton 2008; Briones-Fourzán & Lozano-Álvarez 2008) have experimentally discriminated between different antipredator functions of grouping in any particular species, and none have been conducted in fish. This is an important question because although grouping provides copious antipredator benefits, it also has costs such as increased competition for food (Ekman 1979; Janson & Goldsmith 1995) and risk of disease (Poulin 1999). Because of these costs of grouping, animals should modulate grouping behaviour according to the level of perceived risk, and should group only when the benefits of grouping outweigh the costs (Pitcher & Parrish 1993; Lima & Bednekoff 1999). In other words, animals should only group when it is beneficial to do so. Therefore, understanding the conditions under which animals form groups can reveal insights into the function of grouping behaviour. In this study, we simultaneously tested whether the function of grouping in threespine sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus, is to avoid or to escape from predators.

Threespine sticklebacks are suitable subjects for evaluating the antipredator function of grouping because they are prey to a variety of different predator species, including fish, birds and odonates (Reimchen 1994). Previous studies have shown that sticklebacks use grouping (shoaling and schooling behaviour) as an antipredator defence (Ranta et al. 1992; Tegeder & Krause 1995; Bode et al. 2010; Kozak & Boughman 2012) and that predators are an important selective pressure that has shaped the evolution of schooling behaviour in this species (Vamosi 2002; Doucette et al. 2004). Some of the variation in schooling behaviour in threespine sticklebacks has a heritable basis (Wark et al. 2011), and threespine sticklebacks from populations that are under strong predation pressure school more (Doucette et al. 2004; for a similar pattern in other fish species see Seghers 1974; Foster & Treherne 1981; Magurran & Seghers 1991; Endler 1995).

In sticklebacks, as in most fishes, it is unknown whether prey in high-predation environments school more primarily in order to avoid or to escape from predators. A previous study found that sticklebacks school after a simulated attack by an aerial predator (Tegeder & Krause 1995), which is consistent with the escape hypothesis. Another study found that, in certain populations, repeated exposure to predation risk by trout causes sticklebacks to shoal more when predators are absent (Kozak & Boughman 2012), a finding consistent with the avoidance hypothesis.

However, to our knowledge, no study has attempted to disentangle the relative importance of schooling as an avoidance anti-predator behaviour or as a reaction to the immediate threat of predation to facilitate escape.

Therefore, to discriminate between the avoidance and escape hypotheses, we experimentally manipulated sticklebacks’ previous experience with predation risk and then measured their schooling behaviour. According to the avoidance hypothesis, sticklebacks school in order to avoid encounters with predators. Assuming that fish learn about predation risk via their own experience (e.g. Kelley & Magurran 2003; Ferrari & Chivers 2006), the avoidance hypothesis predicts that sticklebacks with more experience with predators will school more than sticklebacks with less experience, even when predators are not immediately present. We also quantified schooling behaviour of the same individuals following immediate exposure to either a model pike or a nonthreatening control stimulus (a stick). According to the escape hypothesis, sticklebacks school in order to escape from predators. Therefore, the escape hypothesis predicts that sticklebacks will school in immediate response to a predator (Tegeder & Krause 1995), that is, that they will school more in response to the presence of the predator (the model pike) than in response to the presence of a nonthreatening stimulus (the stick). We performed a second experiment to confirm that sticklebacks perceived the model pike as a threat.

Note, however, that the avoidance and escape hypotheses are not mutually exclusive and might interact (e.g. Trokovic et al. 2011). For example, animals with previous experience indicating that predation risk is high might be especially responsive to the immediate threat of predation. Our design allowed us to test whether schooling is used for both avoiding and escaping from predators, and to test for an interaction between previous and immediate experience with predation risk on schooling behaviour.

METHODS

Subjects

Juvenile threespine sticklebacks (G. aculeatus) were collected in November 2011 from Putah Creek, CA, U.S.A., and acclimated to the laboratory for 10 weeks prior to the experiment. Mean ± SE body size of sticklebacks in the experiment was 39.89 ± 0.61 mm. Threespine sticklebacks co-occur with northern pike, Esox lucius, throughout much of their range across the northern hemisphere (Bell & Foster 1994). However, pike are not present in Putah Creek; therefore, any observed differences in stickleback behaviour in our experiments could not be attributed to previous experience with pike. Fish were kept on a 16:8 h light:dark cycle at 20 °C and fed daily ad libitum a diet consisting of bloodworms, Mysis and brine shrimps. Water was cycled via a recirculating flow-through system with particulate, biological and UV filters (Aquaneering, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.).

Experiment 1: Effects of Previous Experience versus Immediate Exposure on Schooling

Overview

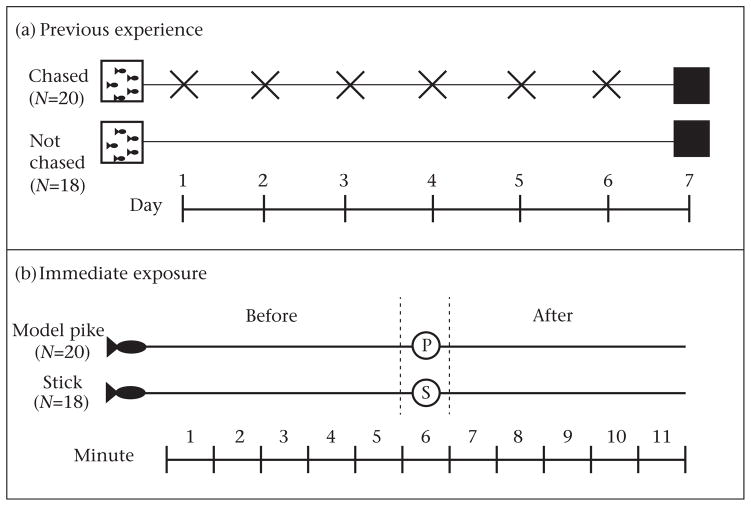

Fish were either chased every day for 1 week by a model pike or were not chased by a model pike (‘previous experience’). Schooling behaviour was then measured before and after exposure to a model pike or stick (‘immediate exposure’). The experimental design is in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of experiment 1. We quantified the influence of both previous experience and immediate exposure to a model predator on schooling behaviour of threespine sticklebacks. (a) To manipulate previous experience, fish were either chased (X) with a model pike and exposed to alarm pheromone (‘chased’) or were ‘not chased’ for 6 days. On the seventh day, fish were individually isolated behind a black tarp for 24 h, represented by black boxes. (b) To examine immediate exposure to predator, schooling behaviour was measured immediately before and after exposure to either a model pike (P) or a piece of water tubing (‘stick,’ S) on day 8. Each individual was placed into a pool and the model school began moving (at Minute 1). Schooling was measured for 5 min. Then, either the model pike or the stick was introduced and ‘swam’ opposite the model school for 1 min. The stimulus was removed and behaviour recorded for 5 min ‘after’ exposure to either the predator or the stick.

Previous experience treatment

We randomly assigned 40 fish to one of eight tanks (53 × 33 × 24 high cm) with five individuals per tank. One week prior to behavioural observations, we randomly assigned the eight tanks to one of two ‘previous experience’ treatments, ‘chased’ and ‘not chased’ (control), with N = 20 individuals per group. Fish in the ‘chased’ group were exposed to a simulated predator attack once per day for 6 consecutive days.

In the ‘chased’ group, a model pike predator was vigorously shaken and thrashed throughout the tank for 30 s. To provide olfactory cues of predation risk, ‘chased’ fish were also exposed to alarm pheromone of dead sticklebacks (Brown & Godin 1997). Alarm pheromone was prepared by removing skin of dead sticklebacks that had been preserved in a −80 °C freezer, mashing the fragments in water for 5 min, and then decanting the fluid (without skin fragments) into 5 ml tubes that were stored at −20 °C for 1 week prior to use. At the same time that the model pike was added to the tank, a 5 ml aliquot of olfactory cues was poured into the tank. Fish in the ‘not chased’ group were not exposed to the model pike and 5 ml of water was added to the control tanks every day as a control for possible disturbance caused by adding alarm pheromone.

Behavioural assay and immediate exposure treatment

To determine whether schooling increases as a result of previous experience with predators (which would support the avoidance hypothesis) or increases upon immediate exposure to the presence of a predator (which would support the escape hypothesis), we observed the schooling behaviour of sticklebacks that differed in previous experience with the model pike before and after their exposure to the model pike predator or a control stimulus (Fig. 1).

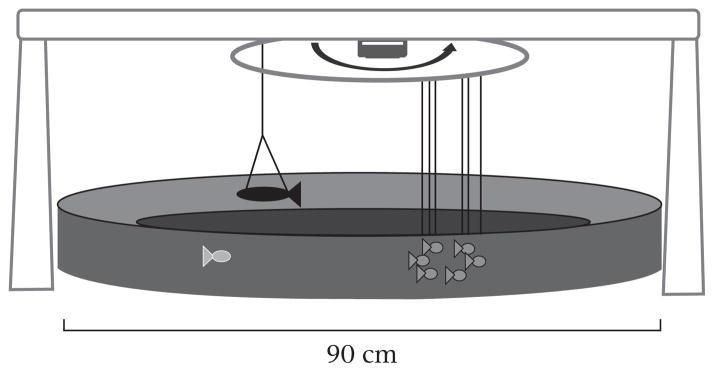

Half of the fish from each ‘previous experience’ treatment were randomly assigned to one of two ‘immediate exposure’ treatments, ‘model pike’ or ‘stick’ (Fig. 1). A ‘school’ of model sticklebacks was used to measure schooling behaviour (similar to Wark et al. 2011). The school consisted of six model sticklebacks (mean ± SE standard length: 39 ± 2.69mm) positioned in a circle and spaced approximately one body length apart (Fig. 2; see Supplementary Fig. S1 for a picture of a model stickleback). Movement of the artificial school was controlled by a motor that randomly made the school ‘swim’ either clockwise or anticlockwise in a 0.9 m diameter pool at 0.75 m/s. We detected no effect of direction on schooling behaviour (results not shown). The pool water was 10 cm deep, and the models were positioned 2 cm above the bottom and an average ± SE of 16.25 ±1.5 cm from the edge of the pool wall (see Supplementary Video S1, which shows a focal fish schooling with the model school). Time spent schooling (swimming within one body length of the school, in seconds), latency to school (s) and the proportion of time spent schooling in the middle of school (behind the first model and in front of the last model) were recorded using JWatcher v1.0 software (http://www.jwatcher.ucla.edu/). We measured the proportion of time spent schooling as the proportion of schooling time rather than as the proportion of total time of the behavioural assay.

Figure 2.

The behavioural arena featured a model school of six clay sticklebacks (medium grey) that ‘swam’ around the arena. Latency to school, time spent schooling and position within school (centre or not centre) of the focal fish was recorded (‘before’ exposure to a model pike or a stick). Then, either a model pike (pictured, dark grey) or a stick was introduced and briefly ‘swam’ opposite the model school. Then, the model pike or stick was removed and schooling behaviour of the focal fish recorded (‘after’).

We tested an equal number of individuals from each treatment group each day and randomized the order in which individuals from each treatment group were tested. A previous study in the laboratory (L. Hostert, unpublished data) showed that 24 h isolation increases rates of schooling. Therefore, prior to testing, individuals were isolated in cups behind a black curtain for 24 h. Immediately prior to a behavioural assay, an individual was gently transferred to the pool and left undisturbed for 4 min. Then, the model school was placed into the pool (‘before’, Fig. 1). One minute later, the school began circling the arena and the behaviour of the focal fish was recorded for 5 min (Fig. 2). While the school was still moving, the ‘immediate exposure’ treatment was applied. In the ‘model pike’ treatment, a model pike (225 mm) was hung 38.1 cm away on the opposite side of the pool from the model school and ‘swam’ simultaneously opposite the school in the same direction as the school (see Supplementary Fig. S1 for a picture of the model pike). In the ‘stick’ treatment, a small tube (125 mm of clear blue water tubing) was hung opposite the school. After 1 min, the model pike or stick was removed. Schooling behaviour was recorded for the following 5 min as described above (‘after’, Fig.1). The focal fish was then removed from the pool and measured for standard length. Time of day was noted at the start of the trial. Every four trials, one-tenth of the water in the pool was suctioned out and replaced to remove fish debris. There was no detectable effect of time, overall trial order, or time since last water change on behaviour (results not shown). Behavioural assays took place during 10–13 February 2012. Two tanks (one ‘chased’ and one ‘not chased’ tank, N = 10 fish) were tested each day.

Experiment 2: Validation of Immediate Exposure

An important assumption of this study was that the sticklebacks would perceive the model pike and the stick differently. To test this assumption, we observed the antipredator behaviour of 20 wild-caught fish from the same population not used in experiment 1 in the presence of the model pike or stick. Individuals were housed in four tanks (N = 5 fish per tank) for 1 week before being individually isolated in cups for 24 h as in experiment 1.

A small plant (65 × 25 ×155 high mm) with gravel underneath (100 × 80 mm) was added to the pool to provide refuge. Prior to the behavioural assay, an individual was gently transferred to the pool and left undisturbed for 10 min (Fig. 2). Then, we attached either the model pike or the stick to the motor and ‘swam’ it around the pool and recorded the following behaviours for 2 min: time frozen, time hiding, time within one body length of the stimulus after actively swimming towards the stimulus, number of freezes and number of times oriented towards the stimulus. Behavioural assays took place on 5–6 March 2012.

Data Analysis

Repeated measures general linear models (subject: individual) were used to determine whether schooling behaviours were affected by previous experience or immediate exposure to a model pike predator or their interaction. Time schooling, latency to school and position in the school were +1 log-transformed to meet model assumptions and each variable was analysed separately. The repeated factor was before and after exposure to the model pike or stick. We chose a compound symmetry within-individual covariance structure over unstructured and first-order autoregressive using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC, Akaike 1974). The following variables were included as fixed factors: previous experience (chased or not chased), immediate exposure (pike or stick), before/after exposure, as well as all two- and three-way interactions. Size and time of day were initially included as covariates in each analysis, but in each case, their associated F values were less than 1 and were therefore removed. Tank was included as a random effect and its significance assessed by model comparison using AIC. In all cases, including tank as a random effect did not improve model fit and was therefore removed. Removal of covariates and tank as random effect did not change the final results. To further compare behaviour in the immediate presence of the model pike and stick, another set of GLMs were run that considered only the ‘after’ data.

In experiment 2, general linear models were used to determine whether the model pike elicited an antipredator response in the sticklebacks. Each behavioural variable was analysed separately. A compound symmetry covariance structure was used. Treatment (pike or stick) was a fixed factor. Size and time of day were included as covariates. Covariates were sequentially removed if F < 1.

Five fish were not included in the analyses: two died over the course of experiment 1, and in three trials, the model pike or stick did not attach to the rotating disk (two from experiment 1, and one from experiment 2). All statistical analyses were conducted in PASW 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.).

Ethical Note

Exposure to simulated predation risk can be stressful for animals. Therefore, we took measures to maximize animal welfare by minimizing the duration of exposure to simulated predation risk and by providing refuges (plants and gravel) in the sticklebacks’ tanks. The experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Illinois (Protocol number 09204, approved on 1 September 2009).

RESULTS

Fish schooled with the model school for a mean ± SE of 95.88 ± 22.95 s during 10 min. This is comparable to rates of schooling by sticklebacks in the field (S. Pearish, personal observation) and similar to published rates of stickleback schooling behaviour (Ranta et al.1992; Frommen et al. 2009; Wark et al. 2011; but see Ward et al. 2007). A summary of the behavioural data is given in Supplementary Table S1.

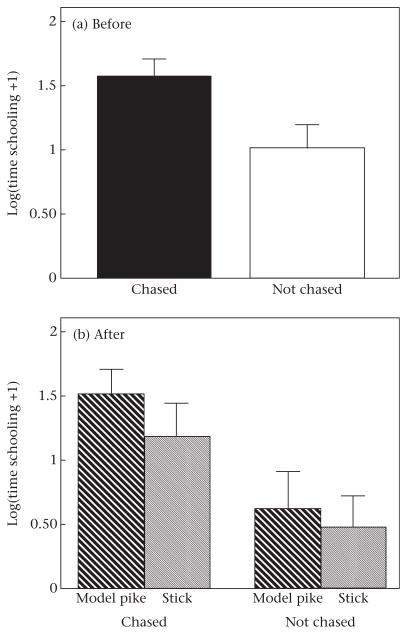

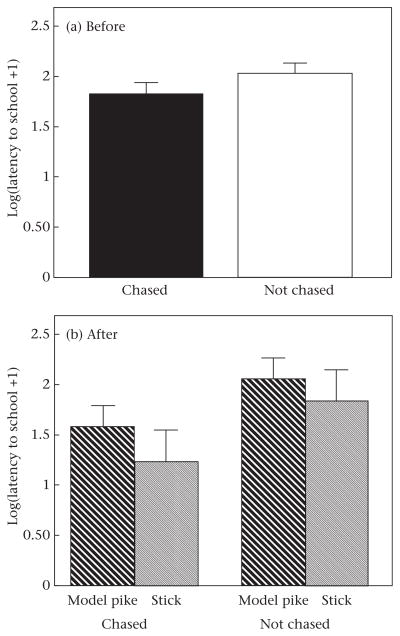

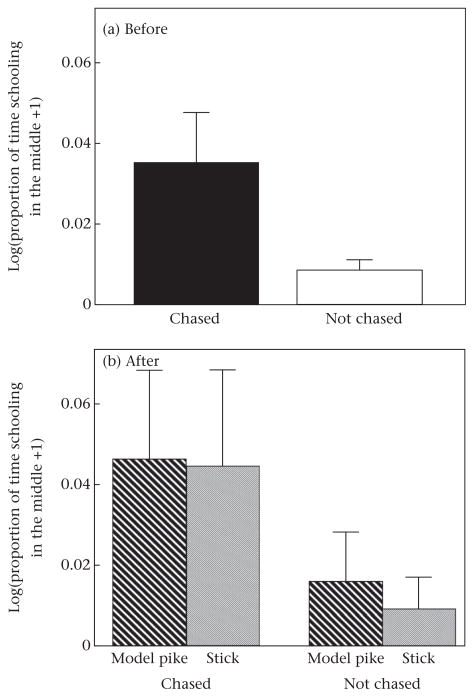

Previous experience influenced schooling behaviour: fish that had been previously ‘chased’ schooled longer (Table 1, Fig. 3), began schooling sooner (Table 2, Fig. 4) and spent a marginally higher proportion of time schooling in the middle of the school (Table 3, Fig. 5) compared to fish that had not been chased (control).

Table 1.

General linear model with repeated measures with individual as the subject on log (total time schooling + 1) in threespine sticklebacks

| F1,32 | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 105.75 | 0.000 |

| Previous | 9.83 | 0.004 |

| Immediate | 0.89 | 0.352 |

| Before/after | 13.5 | 0.001 |

| Previous*immediate | 0.03 | 0.865 |

| Previous*before/after | 1.72 | 0.199 |

| Immediate*before/after | 0.27 | 0.604 |

| Previous*immediate*before/after | 1.60 | 0.215 |

Figure 3.

Time spent schooling by threespine sticklebacks that had been either chased or not chased (a) before and (b) after exposure to a model pike or stick. Error bars denote standard errors.

Table 2.

General linear model with repeated measures with individual as the subject on log (latency to school + 1) in threespine sticklebacks

| F1,32 | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 443.51 | 0.000 |

| Previous | 4.76 | 0.037 |

| Immediate | 0.15 | 0.697 |

| Before/after | 3.54 | 0.069 |

| Previous*immediate | 0.02 | 0.903 |

| Previous*before/after | 1.62 | 0.212 |

| Immediate*before/after | 2.63 | 0.115 |

| Previous*immediate*before/after | 0.44 | 0.514 |

Figure 4.

Latency to school by threespine sticklebacks that had been either chased or not chased (a) before and (b) after exposure to a model pike or a stick. Error bars denote standard errors.

Table 3.

General linear model with repeated measures with individual as the subject on log (proportion of time schooling in the middle of the school + 1) in threespine sticklebacks

| F1,32 | P | |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 9.94 | 0.004 |

| Previous | 3.42 | 0.074 |

| Immediate | 0.21 | 0.886 |

| Before/after | 1.36 | 0.253 |

| Previous*immediate | 0.07 | 0.800 |

| Previous*before/after | 0.25 | 0.621 |

| Immediate*before/after | 0.10 | 0.753 |

| Previous*immediate*before/after | 0.07 | 0.790 |

Figure 5.

Proportion of time schooling in the middle of the school by threespine sticklebacks that had been either chased or not chased (a) before and (b) after exposure to a model pike or stick. Error bars denote standard errors.

In contrast, immediate exposure to a model predator did not affect time schooling (Table 1, Fig. 3), latency to school (Table 2, Fig. 4), or the proportion of time schooling in the middle of the school (Table 3, Fig. 5), as shown by the nonsignificant ‘immediate exposure*before/after’ interaction. Considering only the data ‘after’ exposure to the model pike or stick, there was also no difference in time schooling (F1,32 = 1.068, P = 0.309), latency to school (F1,32 = 1.21, P = 0.280), or the proportion of time schooling in the middle of the school (F1,32 = 0.04, P = 0.838) between fish that were exposed to a model pike or a stick. However, ‘after’ exposure to the model pike or the stick, fish that had been chased schooled more (F1,32 = 10.39, P = 0.003) and had a lower latency to school (F1,32 = 4.18, P = 0.049) than fish without previous experience. There was no difference in the proportion of time schooling in the middle of the school after exposure between fish that had been chased compared to those that had not been chased (F1,32 = 2.87, P = 0.100).

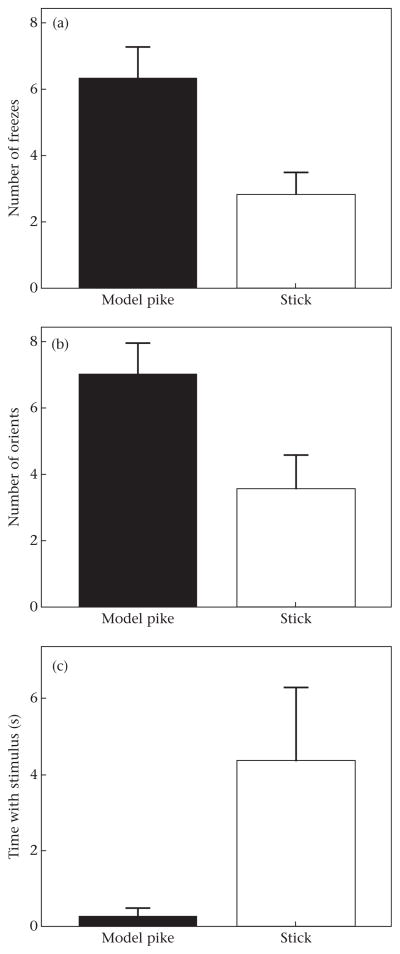

In experiment 2, sticklebacks froze more often in the presence of the model pike than in the presence of the stick (F1,15 = 13.315, P = 0.002; Fig. 6a), oriented more towards the model pike (F1,15 = 6.254, P = 0.024; Fig. 6b) and spent less time with the model pike (F1,15 = 6.917, P = 0.019; Fig. 6c). Exposure to the model pike or stick did not influence time spent frozen or hidden (P > 0.1).

Figure 6.

Number of (a) freezes and (b) orientations towards stimulus, and (c) time spent with stimulus by threespine sticklebacks during exposure to either a model pike or a stick in experiment 2.

DISCUSSION

This experiment tested whether the function of schooling is to avoid predators before an encounter or to escape from predators after an encounter. Threespine sticklebacks previously chased by a model pike schooled more, began schooling faster and spent marginally more time in the middle of the school than individuals that had not been chased. In contrast, immediate exposure to a model pike did not alter schooling behaviour. These results suggest that previous experience with predation risk increases schooling behaviour but immediate exposure does not, a pattern consistent with the avoidance hypothesis but not the escape hypothesis. We found no evidence for an interaction between the avoidance and escape hypotheses.

The test of the escape hypothesis in this experiment relied on the effectiveness of the ‘immediate exposure’ treatment. In other words, we assumed that immediate exposure to a model pike was perceived as a threat, while immediate exposure to a stick was not. To test this assumption, individual behaviour in the presence of the model pike and the stick was compared. Fish showed more anti-predator behaviours in the presence of the model pike than in the presence of the stick: they oriented more to the model pike, spent less time with the model pike and froze more often in the presence of the model pike (Fig. 6). Another study showed that sticklebacks that froze in the presence of a live pike survived for longer than individuals that did not freeze (McGhee et al. 2012). Thus, our results suggest that sticklebacks behaved towards the model pike as though it was a threat.

One potential interpretation of our results is that the sticklebacks in this study were not actively schooling with the model school but were instead treating it as a refuge. In the original development of this assay, Wark et al. (2011) addressed this concern by demonstrating that threespine sticklebacks preferentially associated with the model school over stationary and mobile plant refuges.

Wark et al. (2011) also showed that there is a heritable component to schooling behaviour in this species. Our study suggests that there is also an important role for experience. Indeed, our results suggest that some of the population-level differences in schooling behaviour that are often observed in fish species (Seghers 1974; Magurran & Seghers 1991; Magurran et al.1993; Endler 1995; Wark et al. 2011) could reflect previous experience with predators in the environment.

While our results are consistent with a previous study on sticklebacks (Kozak & Boughman 2012) and strongly support the avoidance hypothesis, there is also support for the escape hypothesis in this species. Tegeder & Krause (1995) showed that individual threespine sticklebacks exposed to a light stimulus representing an aerial predator immediately approached a shoal of other sticklebacks. One possible explanation for the different results is that different types of predators (e.g. bird or fish predator) might elicit different immediate antipredator reactions. Sticklebacks in this experiment did not school in immediate response to the pike model, perhaps because freezing is a more effective immediate tactic than schooling for preventing predation by a fish predator. Freezing might allow sticklebacks to escape from fish predators that rely on their lateral line, an organ that senses hydrodynamic pressure changes in the vicinity, for detecting prey (Reist 1983; Savino & Stein 1989; Brown & Smith 1998; Lehtiniemi 2005).

Knowing the conditions under which animals decide to enter a group is important because although groups provide anti-predator benefits, there are also costs associated with grouping (Ekman 1979; Janson & Goldsmith 1995; Poulin 1999). Thus, animals should group only when the benefits of grouping outweigh the costs (Lima & Bednekoff 1999). Although many studies have documented the antipredator benefits of grouping as a means of predator avoidance or response to predators (Pulliam 1973; Neill & Cullen 1974; Seghers 1974; Foster & Treherne 1981; Monaghan & Metcalfe 1985), the relative importance of these benefits might differ between animal species. By simultaneously testing the avoidance and escape benefits of grouping, the results of our experiment suggest that threespine sticklebacks use grouping as a means of predator avoidance and not escape.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Bell lab for their invaluable comments on the manuscript. This study drew from previous research by Lauren Hostert, to whom we are thankful.

Footnotes

Supplementary material for this article is available, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.10.025.

References

- Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RD. The evolution of social behaviour. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1974;5:325–383. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp G, Ruxton GD. Disentangling risk dilution and collective detection in the antipredator vigilance of semipalmated sandpipers in flocks. Animal Behaviour. 2008;75:1837–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Bell MA, Foster SA. The Evolutionary Biology of the Threespine Stickleback. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bode NWF, Faria JJ, Franks DW, Krause J, Wood AJ. How perceived threat increases synchronization in collectively moving animal groups. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2010;277:3065–3070. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briones-Fourzán P, Lozano-Álvarez E. Coexistence of congeneric spiny lobsters on coral reefs: differences in conspecific aggregation patterns and their potential antipredator benefits. Coral Reefs. 2008;27:275–287. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GE, Godin JGJ. Anti-predator responses to conspecific and heterospecific skin extracts by threespine sticklebacks: alarm pheromones revisited. Behaviour. 1997;134:1123–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GE, Smith RJF. Acquired predator recognition in juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): conditioning hatchery-reared fish to recognize chemical cues of a predator. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 1998;55:611–617. [Google Scholar]

- Calvert WH, Hedrick LE, Brower LP. Mortality of the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus L.): avian predation at five overwintering sites in Mexico. Science. 1979;204:847–851. doi: 10.1126/science.204.4395.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curio E. The adaptive significance of avian mobbing: teleonomic hypotheses and predictions. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 1978;48:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Doucette LI, Skúlason S, Snorrason SS. Risk of predation as a promoting factor of species divergence in threespine sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus L.) Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2004;82:189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman J. Coherence, composition and territories of winter social groups of the willow tit Parus montanus and the crested tit P. cristatus. Ornis Scandinavica. 1979;10:56–68. [Google Scholar]

- Endler JA. Multiple-trait coevolution and environmental gradients in guppies. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 1995;10:22–29. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(00)88956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks B, Dobson FS. Mechanisms of the group-size effect on vigilance in Columbian ground squirrels: dilution versus detection. Animal Behaviour. 2007;73:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Farr JA. Role of predation in the evolution of social behavior of natural populations of the guppy, Poecilia reticulate (Pisces: Poeciliidae) Evolution. 1975;29:151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1975.tb00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari MCO, Chivers DP. Learning threat-sensitive predator avoidance: how do fathead minnows incorporate conflicting information? Animal Behaviour. 2006;71:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Foster WA, Treherne JE. Evidence for the dilution effect in the selfish herd from fish predation on a marine insect. Nature. 1981;293:466–467. [Google Scholar]

- Frommen JG, Hiermes M, Bakker TCM. Disentangling the effects of group size and density on shoaling decisions of three-spined sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus) Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2009;63:1141–1148. [Google Scholar]

- Godin JGJ, Classon LJ, Abrahams MV. Group vigilance and shoal size in a small characin fish. Behaviour. 1988;104:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Inman AJ, Krebs JR. Predation and group living. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 1987;2:31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Janson CH, Goldsmith ML. Predicting group size in primates: foraging costs and predation risks. Behavioral Ecology. 1995;6:326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Jarman PJ. Group size and activity in eastern grey kangaroos. Animal Behaviour. 1987;35:1044–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley JL, Magurran AE. Learned predator recognition and antipredator responses in fishes. Fish and Fisheries. 2003;4:216–226. [Google Scholar]

- Kenward RE. Hawks and doves: factors affecting success and selection in goshawk attacks on wild pigeons. Journal of Animal Ecology. 1978;47:449–460. [Google Scholar]

- Kozak GM, Boughman JW. Plastic responses to parents and predators lead to divergent shoaling behaviour in sticklebacks. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2012;25:759–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M. Possible functions of the octavolateralis system in fish schooling. Fish and Fisheries. 2009;10:344–353. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M. Incidental sounds of locomotion in animal cognition. Animal Cognition. 2012;15:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10071-011-0433-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtiniemi M. Swim or hide: predator cues cause species specific reactions in young fish larvae. Journal of Fish Biology. 2005;66:1285–1299. [Google Scholar]

- Lima SL. The influence of models on the interpretation of vigilance. In: Bekoff M, Jamieson D, editors. Interpretation and Explanation in the Study of Animal Behavior: Vol. 2. Explanation, Evolution and Adaptation. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press; 1990. pp. 246–267. [Google Scholar]

- Lima SL, Bednekoff PA. Temporal variation in danger drives anti-predator behavior: the predation risk allocation hypothesis. American Naturalist. 1999;153:649–659. doi: 10.1086/303202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima SL, Dill LM. Behavioral decisions made under the risk of predation: a review and prospectus. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 1990;68:619–640. [Google Scholar]

- McGhee KE, Pintor LM, Suhr EL, Bell AM. Maternal exposure to predation risk decreases offspring antipredator behaviour and survival in threespine stickleback. Functional Ecology. 2012;26:932–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02008.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.02008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magurran AE. Predator inspection behaviour of minnow shoals: differences between populations and individuals. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 1986;19:267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran AE, Seghers BH. Variation in schooling and aggression amongst guppy (Poecilia reticulata) populations in Trinidad. Behaviour. 1991;118:214–234. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran AE, Oulton WJ, Pitcher TJ. Vigilant behaviour and shoal size in minnows. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie. 1985;67:167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Magurran AE, Seghers BH, Carvalho GR, Shaw PW. Evolution of adaptive variation in antipredator behavior. Marine Behaviour and Physiology. 1993;23:29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan P, Metcalfe NB. Group foraging in wild brown hares: effects of resource distribution and social status. Animal Behaviour. 1985;33:993–999. [Google Scholar]

- Neill SRS, Cullen JM. Experiments on whether schooling by their prey affects hunting behavior of cephalopods and fish predators. Journal of Zoology. 1974;172:549–569. [Google Scholar]

- New JG, Fewkes LA, Khan AN. Strike feeding behavior in the muskellunge, Esox masquinongy: contributions of the lateral line and visual sensory systems. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2001;204:1207–1221. doi: 10.1242/jeb.204.6.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostreiher R. Is mobbing altruistic or selfish behaviour? Animal Behaviour. 2003;66:145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher TJ. Heuristic definitions of shoaling behaviour. Animal Behaviour. 1983;31:611–613. [Google Scholar]

- Pitcher TJ, Parrish JK. Functions of shoaling behaviour in teleosts. In: Pitcher TJ, editor. Behaviour of Teleost Fishes. London: Chapman & Hall; 1993. pp. 363–439. [Google Scholar]

- Poulin R. Parasitism and shoal size in juvenile sticklebacks: conflicting selection pressures from different ectoparasites. Ethology. 1999;105:959–968. [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam HR. On the advantages of flocking. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1973;38:419–422. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(73)90184-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulliam HR, Caraco T. Living in groups: is there an optimal group size? In: Krebs JR, Davies NB, editors. Behavioral Ecology: an Evolutionary Approach. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer; 1984. pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ranta E, Lindström K, Peuhkuri N. Size matters when three-spined sticklebacks go to school. Animal Behaviour. 1992;43:160–162. [Google Scholar]

- Reimchen TE. Predators and morphological evolution in threespine stickleback. In: Bell MA, Foster SA, editors. The Evolutionary Biology of the Threespine Stickleback. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 240–273. [Google Scholar]

- Reist JD. Behavioral variation in pelvic phenotypes of brook stickleback, Culaea inconstans, in response to predation by northern pike, Esox lucius. Environmental Biology of Fishes. 1983;8:255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G. Why individual vigilance declines as group size increases. Animal Behaviour. 1996;51:1077–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Savino JF, Stein RA. Behavioural interactions between fish predators and their prey: effects of plant density. Animal Behaviour. 1989;37:311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Seghers BH. Schooling behavior in the guppy (Poecilia reticulata): an evolutionary response to predation. Evolution. 1974;28:486–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1974.tb00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder RW, Krause J. Density dependence and numerosity in fright stimulated aggregation behaviour of shoaling fish. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B. 1995;350:381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Tosh CR, Krause J, Ruxton GD. Basic features, conjunctive searches, and the confusion effect in predator–prey interactions. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2009;63:473–475. [Google Scholar]

- Trokovic N, Herczeg G, McCairns RJS, Ab Ghani NI, Merilä J. Intraspecific divergence in the lateral line system in the nine-spined stickleback (Pungitius pungitius) Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2011;24:1546–1558. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner GF, Pitcher TJ. Attack abatement: a model for group protection by combined avoidance and dilution. American Naturalist. 1986;128:228–240. [Google Scholar]

- Vamosi SM. Predation sharpens the adaptive peaks: survival trade-offs in sympatric sticklebacks. Annales Zoologici Fennici. 2002;39:237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Ward AJW, Webster MM, Hart PJB. Social recognition in wild fish populations. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2007;274:1071–1077. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wark AR, Greenwood AK, Taylor EM, Yoshida K, Peichel CL. Heritable differences in schooling behavior among threespine stickleback populations revealed by a novel assay. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018316. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.