INTRODUCTION

Nanoparticle technology has long been applied to augment immunotherapy via effective delivery of antigen or immunoadjuvant to antigen presenting cells (APCs) (ref 13–15). An interesting alternative approach is to use nanoparticles to block or engage the surface receptors of APCs. For innate immunity, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and foreign antigen on APCs are recognized by T cell receptors (TCR) on T cells, which is a critical step for antigen recognition. Thus, one immune modulating strategy is to decorate nanoparticles with immune cell-recognizable peptides, polysaccharides, and antibodies to enhance or intercept these MHC-TCR interactions, a strategy successfully demonstrated against infectious diseases and cancers.16–19 For instance, short peptides containing MHC I or II covalently attached to carboxylated polystyrene beads could induce strong innate immunity and protection against tumor cells by activating the antigen presentation pathway (ref 20). In another study, T cell-mediated immune response could be down-regulated by simultaneous blocking of lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) and intra cellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), accomplished by using two separate anti LFA-1 and anti ICAM-1 nanoparticles with antibodies against those antigens for dendritic cells and T cells, respectively.21

Spherical nanoparticles have been used in these studies. We hypothesize that multi-segmented nanorods would be advantageous over spherical nanoparticles in engaging cell-cell interactions because of the spatial control of multiple ligands on a nanorod. Multi-segmented metallic nanorods can be readily synthesized by templated electrodeposition. The diameter and length of the nanorods can be controlled by the template, typically a porous polymeric membrane that is removed by acid dissolution after the electrodeposition. Importantly, different metals can be deposited on the template in a sequential manner to create multiple segments of controllable length. This in turn allows different functional groups to be immobilized on the respective segments based on specific metal-ligand interactions, for example, thiol on Au and carboxylic acid on Ni. This strategy has been applied to improve biolistic gene gun delivery, with DNA immobilized on the Ni segment and transferrin on the Au segment of a bi-segmented Ni/Au nanorod.10 It has also been used to functionalize triple-segmented nanowires composed of Au/Pt/Au with proteins through specific covalent linkages between proteins and metal segments.11 We previously surface-functionalized bi-metallic nanorods with a folate and a thermo-sensitive polymer for temperature-responsive incorporation and release of doxorubicin. Upon increasing the length of the gold segment where doxorubicin was immobilized, anti-cancer effect was accordingly escalated, highlighting the versatility to control the functionality of the nanorod by varying the length ratio of the metallic segments.12 Thus, in terms of conferring multi-functionality and multi-valency to nanostructures, multi-segmented nanorods are superior to spherical nanoparticles because of the spatial control for heterogeneous surface chemistries.

We here propose a bridging strategy for facilitated T cell-mediated immune responses by increasing intercellular association of immune cells with immune-recognizable Au/Ni nanorods (Au/Ni NRs). Au/Ni NRs were fabricated by an electrodeposition technique and the Au segment was surface-decorated with mannose, intended to target DCs, and the Ni segment with a RGD peptide for immune cell recognition, respectively. By bridging DCs to T cell, we speculate the antigen presenting pathway will be facilitated due to the intercellular proximity, which is a critical step toward antigen presentation. Multi-functionalization of the nanorod was characterized by electron and confocal microscopy and the cytokine release patterns from T cells were compared according to the segmental ratio of the functionalized nanorods. The proximity of the immune cells and the nanorods was also confirmed by electron microscopy and confocal microscopy. The in vitro T cell response as manifested by IL-2 and TNF (a?) was enhanced with a Au/Ni ratio of x:y in the nanorods that were x nm in diameter and y nm in length.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

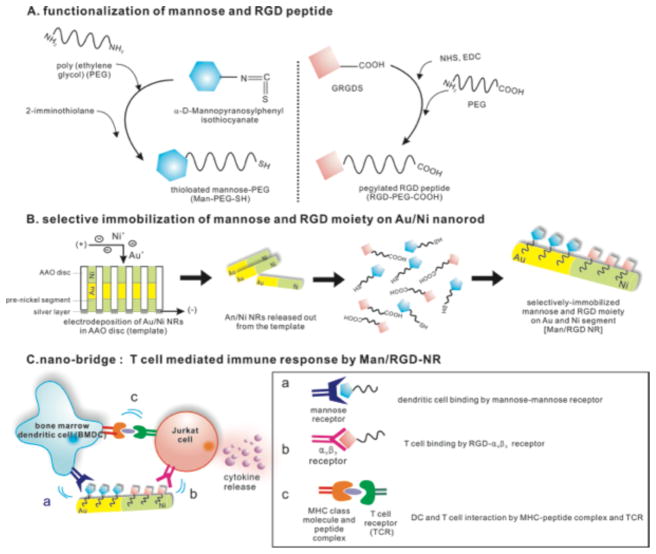

In order to fabricate immune-recognizable ‘nano-bridge’, a bi-segmented nanorod composed of gold and nickel was electrodeposited and then surface-functionalized with two different ligands for BMDCs and Jurkat cells (Figure 1). The template-based fabrication of metallic nanorods by electrodeposition has several advantages such as multi-segmentation of the nanorods and controlling the aspect ratio of the nanorods according to the electric coulombs. Thus, we fabricated three types of bi-metallic nanorods with different lengths (1, 2, and 4μm) and then selectively surface-modified them with mannose and GRGDS (Man/RGD NRs). This was accomplished by introducing thiol groups and carboxylate groups to pegylated mannose and GRGDS, respectively, for metal-selective immobilization and the synthesis of the conjugates were also confirmed (Figure 1A; Figure S1). The pegylation served as a spacer to ensure a good display of the ligand on the surface and to improve the colloidal stability of the nanorods. Because the ligands were displayed on the surface via a hydrophilic linker, we speculated that the ligands could be easily recognizable by immune cells as shown in the literature.22, 23

Figure 1.

Preparation of Au/Ni nanorod for selective immobilization of mannose and RGD peptide (Man/RGD NR) and description of ‘nano-bridge’ for enhanced T cell-mediated immune responses. (A) Functionalization of mannose and RGD peptides for surface-immobilization. After pegylation of mannose, the terminal amine group of Man-PEG-NH2 was thiolated with 2-imminothiolane to prepare Man-PEG-SH. RGD-PEG-COOH was synthesized by conjugating hetero-functional PEG (NH2-PEG-COOH) to the activated GRGDS peptides. (B) Selective immobilization of Au and Ni segments with the functionalized mannose and RGD peptides. After sequential electrodeposition of Au and Ni, Man-PEG-SH and RGD-PEG-COOH were added for selective modification by Au-thiol and Ni-carboxylic acid reactions. (C) BMDC and Jurkat cell-recognizable ‘nano-bridge’ for facilitating antigen presentation. By bridging between BMDC and Jurkat cell, the antigen presentation is facilitated and T cell mediated immune response is fortified.

Numerous studies have indicated that thiolated molecules and carboxylated biomolecules could be selectively immobilized on the surface of Au and Ni through these linkages.10, 12 Previously, we fabricated bi-metallic nanorods by electrodeposition and selectively surface-functionalized the Au/Ni segments with thiolated Pluronic and folate.12 Here, the metal selective-decoration strategy of bi-metallic nanorods was employed for fabricating immune-recognizable nano-bridges. Thus, the decorated nanorods made of equal part of RGD moieties and mannose shows a multi-valency toward BMDCs and Jurkat cells (Figure 1B and C). Antigen presentation occurs when antigen presenting cells such as mature and activated dendritic cells are in close contact with immature T cells to present a MHC and peptide fragment complex to TCR and activate T cells. Thus, we speculate that the antigen presentation behavior can be greatly influenced by the proximity of those two cells. We also hypothesize that the antigen presentation event of two immune cells can be controlled by changing the segmental lengths of the dual-functionalized nano-bridge because those interactions can be facilitated or suppressed according to the manipulated proximity.

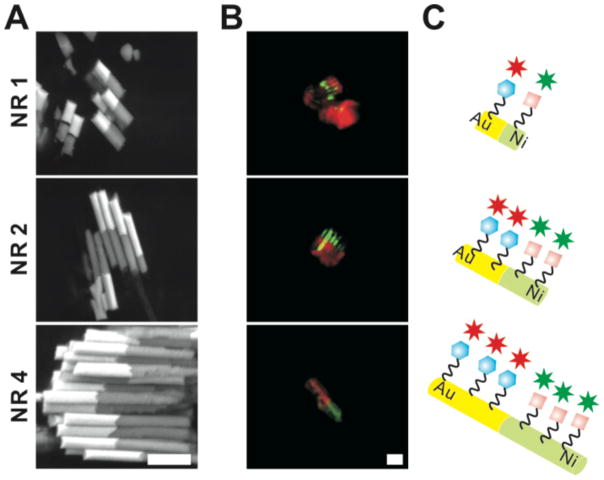

After fabricating bi-metallic nanorods with two different ligands, we confirmed the Au/Ni NR structure and spatially controlled immobilization of RGD and mannose moieties on the nanorods by SEM and CLSM (Figure 2). The back-scattered SEM images clearly showed that the nanorods were composed of Au (light grey) and Ni (dark grey) segments with a 1:1 aspect ratio and the total length was 1, 2, and 4μm (Figure 2A). When the surface-immobilized ligands were fluorescently labeled with respective dyes, the mannose moieties and RGD moieties were confirmed to be spatially confined on the Au/Ni NRs, maintaining the same respect ratio of Au/Ni NRs (Figure 2B). This result clearly confirmed that those ligands were selectively attached to each segment; the mannose moieties to Au segments and the RGD moieties to Ni segments. As shown in Figure 2C, while the mannose moieties and the RGD moieties were immobilized on the surface at the same aspect ratio (1:1), the functionalized area of the nanorods gradually increase as the length of the nanorods increase from 1μm to 4μm. Thus, we hypothesize that the Man/RGD NR would show multi-valency against two different immune cells while the affinity toward respective cells would escalate as the length of the nanorods increase due to the increased amount of mannose moieties or RGD moieties on NR surface. Unlike spherical nanoparticles, the degree of surface-immobilization on the nanorods is readily controllable and favorably employed to surface-immobilize different ligands toward specific cell types in a single nanorod, whose implication on interactions with cells has been amply documented in the literature.8, 24–26

Figure 2.

Visualization of Mannose/RGD moieties-immobilized nanorods (Man/RGD NR) with different lengths (NR 1 = 1μm, NR 2 = 2μm, and NR 4 = 4μm). Back-scattered SEM images (A) shows bi-segmented nanorods composed of Au (white) and Ni segment (dark grey) of fluorescently-labeled Man/RGD NR. In CLSM images (B), where Alexa 647-labeled Mannose and FITC-labeled RGD moieties are shown in red and green, respectively. The illustrations of the Man/RGD NR are also represented (C). The scale bars of all microscopic images are 2μm.

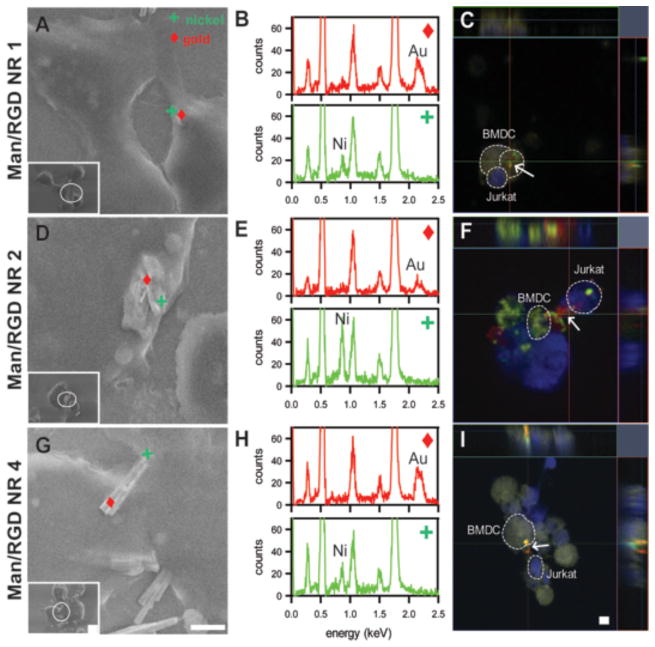

Man/RGD NRs were incubated with Jurkat cells and differentiated BMDCs (as confirmed in Figure S2) and their proximity was visualized by VP-SEM with EDX and CLSM as shown Figure 3. We pre-incubated with Jurkat cells with Man/RGD NRs 3h prior to addition of BMDCs to maximize the RGD-αvβ3 interactions between the RGD moieties of the NRs. In order to monitor the association of NRs to Jurkat cells or BMDCs, we employed VP-SEM to capture the images of the cells associated with NRs. Although mannose and RGD moieties have high affinities toward respective receptors on cells, the associated NRs/immune cells complex might be disrupted during the preparation of specimen for conventional SEM due to harsh conditions such as dehydration or drying steps. During the preparation of samples for VP-SEM, however, the NRs associated with cells remained intact because the disruption could be minimized as discussed in the experimental. Thus, after placing the fixed NRs/immune cell complex on a cool stage of VP-SEM, we visualized the moment of cell-to-NR interactions in an identical status of in vitro cultivation. In Figure 3A, D, G, the VP-SEM images visualized the Man/RGD NRs association with immune cells at low and high magnification and the orientation of the NRs was also confirmed by elemental analysis, where the spotted nanorods were analyzed by EDX for confirmation of Ni (green spots) and Au (red spots) (Figure 3B, E, and H). Most short nanorods were engulfed or phagocytosed by cells while longer ones were surface-attached to the cells; NR1 (Figure 3A) were buried in the cellular membranes while the morphology of the NRs became distinguishable from Man/RGD NR2 (Figure 3D) to Man/RGD NR4 (Figure 3G). This can be attributed to the differential phagocytic behavior of cells depending on the dimension of NRs. Previous studies employing nanorods and nanowires with smaller dimensions have consistently indicated that small nanorods and nanowires have a tendency to be engulfed by surrounding cells.27, 28 In our previous study, we also observed that the bi-segmented nanorods below 2μm were internalized by cancer cells after ligand-receptor interaction in the cell surface, where the endocytic uptakes were desirable for delivery of anti-cancer drugs 12. In another study, electrodeposited nanorods for gene therapy were employed for transfection of cancer cells. Due to the short length of 100 nm, the nanorods were efficiently endocytosed by the cells.10 Although the efficiency of phagocytosis is dependent on cell type and rigidity of the nanowire, the size has been shown to be the major factor controlling cellular uptake.29–32 Similarly, in the current study, the tendency of phagocytosis clearly decreased when the size of the NR increased; we observed that some Man/RGD NR2 was also phagocytosed, and Man/RGD NR 4 was not engulfed by cells. This result strongly suggests that the length of a nano-bridge needs to be optimized to tether immune cells together for facilitated immune responses because the bridges are required to be located on the surface of the immune cells. Thus, we speculated that Man/RGD NR 4 can serve as the potential candidate for the nano-bridge over Man/RGD NR1 or Man/RGD NR2 in terms of minimizing the cellular uptake.

Figure 3.

Visualization of the immune cells bridged with Man/RGD NRs. The proximity of the nanorods was confirmed both by VP-SEM (A, E and G) equipped with EDS (B, E, and H) and CLSM (C, F, and I). Man/RGD-NRs were incubated with T cells for 3h and LPS-activated BMDCs were then added. After 18h, Man/RGD-NR associated with BMDC and T cell was visualized by VP-SEM on a cool-stage at −14°C (left). While the inset images are in low magnification, the magnified images of the white circles in the inset were also shown. EDS spectrum of the indicated spots (□/+) in SEM images (middle). The peaks of Ni (0.9 keV) and Au (2.3 keV) were assigned to determine the orientation of the Man or RGD. In CLSM images, BMDC (yellow) and T cell (blue) were shown with Man/RGD-NR (white arrow) with RGD (green) and mannose (red) (right). Orthogonal views are also presented on the upper and the right to highlight the location of the nanorods. All scale bars in the images indicate 2μm.

Although the proximity of the immune cells to NRs could be visualized by SEM, this method could not confirm whether the bridging was actually caused by specific interactions between the immobilized ligands of NRs and respective cellular receptors. This was accomplished by tagging each molecule and cell with specific fluorescence probes and examination by CLSM. It should be noted that the multiple slices of the CLSM images with different z-axis were intentionally superimposed on one 2-D image to locate NRs whatever their orientation was within the NR-immune cell complex. Figure 3C, F, and I show the CLSM images of NR-immune cells complex, where Jurkat cell (blue) and BMDC (yellow) were fluorescently labeled for discrimination of cell types. Mannose (red) and RGD moiety (green) on the NRs were also labeled for determining their directions. The orthogonal views of the NRs-immune cell complex were also shown in the upper and the right sides of the z-axis stacked CLSM images to determine 3-D locations of the NRs associated with Jurkat cells and BMDCs. In Figure 3C, Man/RGD NR 1 (white arrow) was located in the middle of BMDC in the 2-D view as well as the orthogonal view. This suggests that the NR1 was internalized by the cells rather than attached on the surface of the cells. However, Man/RGD NR 2 and Man/RGD NR 4 were shown to be attached on the surface of the cells and located between Jurkat cells and BMDCs. More specifically, the orientation of the NRs were dependent on the ligands-receptor interaction; the mannose (red) were attached to the surface of BMDCs (yellow) while the RGD moieties (green) were associated with Jurkat cells (blue). In together with the SEM images, these results clearly suggest that the longer NRs can play a role of a bridge to tether Jurkat cells and BMDCs by the specific ligand-receptor interactions. Several studies have previously shown that immune responses could be stimulated with multi-valent nanospheres.29, 30 The conventional immunotherapeutic strategies were mainly focused on increasing the avidity of the nanospheres by immobilizing multiple ligands and using the decorated nanospheres to subsequently block or stimulate the receptors for suppressing and provoking immune responses. On the other hand, our study is well distinguished from those studies in terms of the binding strategy; Man/RGD NRs are designed as nano-bridges to simultaneously target toward multiple types of immune cells and bringing them together.

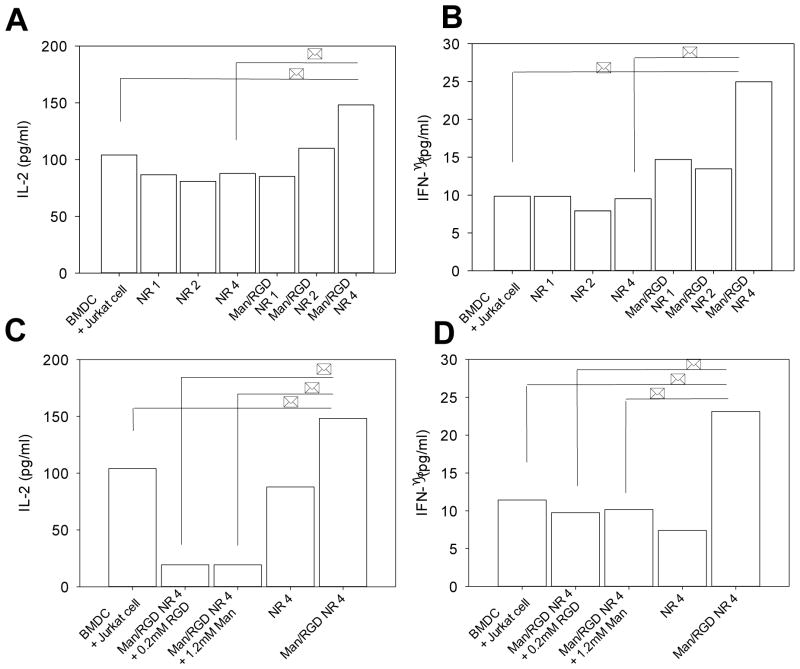

Cytokine release of T lymphocytes, a hallmark of humoral immunity, is primarily caused by antigen presentation of activated dendritic cells. We therefore monitored the cytokine levels to determine the effects of the nano-bridging on the antigen presentation process. First, the ratio of the NRs to BMDCs was optimized for increased levels of cytokine production. This was accomplished by escalating the number of NR with respect to that of Jurkat cells from 1 to 500 with a fixed ratio of BMDCs to Jurkat cell (Figure S3). We measured IL-2 levels for 24h and concluded that a 50:1 ratio of NRs to Jurkat cells would be optimal because the cytokine production did not show significant improvement beyond this ratio. Based on the preliminary study, IL-2 and IFN-γ levels were determined for the bridging system composed of the immune cells and Man/RGD NRs with different lengths (Figure 4). The cytokine levels showed a strong dependency on the length of the NRs; the cytokine levels clearly increased when the length of the NR increased from NR 1 to NR 4 (Figure 4A and B). Up to 2 μm in length, the decorated NRs did not show any statistical differences in cytokine levels compared to unmodified NRs. However, Man/RGD NR 4 clearly increased both IL-2 and IFN-γ levels by 1.4-folds and 2.5-folds in comparison to those with NRs, respectively. Thus, we can speculate that all Man/RGD NRs can bind to the immune cells by specific ligand-receptor interactions, however, Man/RGD NR 1 and Man/RGD NR 2 cannot serve as nano-bridges because they are internalized after the specific binding. In accordance with the result from Figure 3, this result strengthens the importance of the optimized length for the bridging system for facilitated antigen presentation. Furthermore, we also inhibited the specific ligand-receptor interactions of Man/RGD NRs towards the immune cells to exclude the possibility of non-specific activation of immune responses by gold segments as indicated by several studies (Figure 4C and D)31. When either of RGD moiety or mannose was added to the bridging system, the cytokine levels were significantly diminished. This can be certainly attributed to the blocking of αvβ3 receptors and mannose receptor of Jurkat cells and BMDCs. In the bridging system, Man/RGD NRs need to be simultaneously anchored both to BMDCs and Jurkat cells for facilitation of antigen presentation. Thus, when either of this anchoring is blocked, the whole process of the antigen presentation is affected and the cytokine release is decreased accordingly. Consequently, we showed that antigen presentation of DCs could be facilitated by the physical bridging of two immune cells, whose concept was proved by bi-segmented nanorods co-decorated with mannose and RGD moieties.

Figure 4.

Cytokine release from T cell upon administration of nanorods. Jurkat cells were incubated with Man/RGD NRs at the presence of CD11c+ BMDCs in serum free media for 24h. Man/RGD NRs were pre-incubated with Jurkat cells for 3h and CD11c+ BMDCs were added (number ratio of NR: Jurkat cell: BMDC=50:5:1). (A) Interleukine-2 (IL-2) and (B) interferon-γ (IFN-γ) levels of the released medium were determined by ELISA as described in Methods. In (C) and (D), RGD receptor (αvβ3) on T cells or mannose receptors on BMDC were pre-blocked in the cell culture medium containing 0.2 mM RGD peptides or 1.2 mM mannose to disturb the association of Man/RGD NR 4 toward immune cells. (C) IL-2 and (D) IFN-γ levels were measured with the same method. * indicates statistical significance (p<0.05).

CONCLUSION

A novel application of multi-segmented nanorods was demonstrated in this study to facilitate the antigen presentation process. Bi-segmental Au/Ni nanorods, 1–4 μm in length and xx nm in diameter, and selectively decorated with mannose and GRGDS on the respective metallic segments, served as nano-bridges to bring BMDC and Jurkat cells into close proximity. The 4 μm Au/Ni nanorods were optimal with respect to minimal phagocytosis and maximal enhancement of IL-2 and INF secretion. These novel nanorods may serve as interesting tools for ligand discovery towards immunotherapy and to gain mechanistic insight on the antigen presentation process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Anodized Aluminium Oxide (AAO) membrane, Anodisc, with a pore size of 0.1μm, was obtained from Whatman (Maidstone, England). Nickel (II) sulfate hexahydrate, nickel (II) chloride, α-D-Mannopyranosylphenyl isothiocyanate, lipopolysaccharide, and 2-mercaptoethanol were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St, Louis, MO). GRGDS (Anygen, South Korea) was purchased from Anygen (Gwangju, South Korea). Poly(ethyleneglycol) diamine (PEG-(NH2)2, Mw 2,000) and amine-poly(ethyleneglycol)-acid (NH2-PEG-COOH, Mw 2,000) were purchased from Sunbio (Anyang, South Korea). Human T lymphocytes (Jurkat cell) were purchased from Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, South Korea). RPMI1640 medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), streptomycin, penicillin, Trypsin/EDTA, and Alexa 647 conjugated concanavalin A were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Anti-CD11c (mouse), anti CD3 (human), and human interferon gamma (IFN-γ) ELISA development kits (ELISA Ready-SET-Go) were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Recombinant murine granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and human interleukin-2 (IL-2) ELISA development kit were purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ). FITC-anti CD11c (mouse) and FITC-IgG1 (hamster, isotype control) were purchased from BD Pharmingen™ (San Diego, CA). Alexa Fluor® 405 carboxylic acid succinimidyl ester and Texas Red®-X succinimidyl ester (mixed isomers) were purchased from Invitrogen.

Electrodeposition of multi-segmented metallic nanorod

Multi-segmented metallic nanorods were electrodeposited on the nanoporous Anodisc with the same method as previously described in the literature with minor modifications.10 Briefly, the aspect ratio of Au/Ni NRs were uniformly controlled by electrically depositing Au and Ni ions into porous Anodisc (template), where one side of the Anodisc was covered with silver layers by a thermo-evaporation technique (National Nanofab Center, Daejeon, Korea). Ni ions were first deposited to be served as a pre-deposited segment and then Au and Ni ions were sequentially deposited in order to fabricate Au/Ni multi-segmented metallic nanorods. Reductive potential was regularly applied at −0.95V and coulomb was applied according to the length of Au or Ni segment (−1.3C to −3.8C or −1.4C to −6.9C). In order to release single Au/Ni NRs from the template disc, silver layer and pre-Ni segment were removed by dissolving in 70% (v/v) nitric solution and Anodisc was dissolved in 3M sodium hydroxide. Au/Ni NRs were washed with methanol several times and visualized with a back scattered field emission scanning electron microscope at the Core Laboratory of Kangwon National University (FE-SEM, S-4300, Hitachi, Japan).

Synthesis of mannose and GRGDS for immobilization

Mannose and GRGDS were immobilized on Au and Ni segment through a short spacer of PEG, respectively. For the immobilization of mannose, PEG-(NH2)2 (10.62 mg) in methanol (10 ml) was slowly dropped into α-D-mannopyranosylphenyl isothiocyanate (mannose) (2 mg) in methanol (1 ml). The reaction mixture was reacted at 4°C for 12h and vacuum-dried at 30°C. The synthesized mannose-PEG (NH2) (Man-PEG-NH2) was thiolated with Traut’s reagent (5.8 mg) in 50 mM bicin buffer (10 ml, pH 8.0), at 4°C for 1h and dialyzed in distilled water (DW) three times (Spectra Por6, MW cutoff= 1,000). In order to Pegylate GRGDS (RGD), the C terminus of GRGDS (1 mg) was activated using EDC (0.38 mg) and NHS (0.66 mg) in 1X PBS (pH 6.0) (the molar ratio of GRGDS: EDC: NHS = 1: 10: 2.69), and subsequently reacted with NH2-PEG-COOH (5.66 mg) at 4°C for 12h. Unreacted GRGDS and chemicals were removed by extensive dialysis in DW (SpectraPor6, MW cutoff = 1,000). The thiolated Man-PEG-NH2 (Man) and the pegylated GRGDS were characterized by 600 Mhz 1H-NMR spectroscopy in dimethyl sulfoxide-d6 (DPX600, Bruker).

Surface-modification of Au/Ni NRs with mannose and RGD moiety

The Au segment and the Ni segment of the nanorods were exclusively decorated with Man and RGD, respectively. In order to immobilize Man on Au segments, nanorod suspension (0.01 mg to 0.80 mg) in methanol was mixed with Man (0.08 mg to 0.32 mg) as the molar ratio of Au to Man was 1:1, under strong shaking at room temperature for 2h. Sequentially RGD (0.2 mg to 0.8 mg) was added to the nanorod suspension and reacted at 4°C for 12h. Unmodified Man and RGD and were washed out with DW for 10 times. In order to confirm specific immobilization of Man and RGD on Au/Ni NRs (Man/RGD NRs), Man and RGD were fluorescently labeled with Alexa 647 conjugated concanavalin A (Alexa 647-Con A) and fluorescence isothiocyanate (FITC). Alexa 647-Con A (200μg/ml) was specifically bind to mannose on Au segment in PBS (pH 7.2) at room temperature for 3h and FITC was chemically conjugated with N-terminal of RGD on Ni segment in methanol at 4°C for 12h. Excessive amounts of fluorescent dye was washed out with PBS and methanol, and visualized by confocal scanning laser microscopy (CLSM) at Korea Basic Science Institute (Carl Zeiss, LSM700, Germany). Alexa 647 and FITC were individually excited at 633 nm (Helium-Neon laser) and 488 nm (Argon-ion laser). Emission filters were set for detection of Alexa 647 (bp 620–680 nm) and FITC (bp 520–540 nm) at multi-tracking modes.

Preparation of BMDCs

Lymphocytes from murine bone marrow were freshly prepared and differentiated into BMDC by GM-CSF with a minor modification according to the literatures.32 Bone marrow cells (5×105 cell/ml) from the femurs and the tibia of C57BL/6 mice (female, 5–8 weeks) were seeded on a bacteriological plate and cultivated in 10 ml of a dendritic cell-differentiation medium (R10) with 200 U/ml of GM-CSF; RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS (v/v), streptomycin/penicillin, and 50μM of 2-mercaptoethanol. At day 3, 10 ml of additional fresh R10 containing 200 U/ml of GM-CSF was added to the plate. At day 6 and 8, the half media was exchanged with fresh R10 containing 100 U/ml of GM-CSF. In order to quantify the amount of CD11c+ BMDCs, the non-adherent cells at day 7 or 8 were collected and washed with PBS and re-suspended in an immunostaining buffer (PBS, 0.1% (v/v) FBS, 0.1% (v/v) sodium azide) in a round-bottom tube. Cells were fluorescently labeled with FITC-anti-CD11c at 4°C for 20 min and CD11c+ BMDCs were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells with desirable forward scattering and side scatting intensities between 200 and 700 were gated and further analyzed for detection of FITC-anti-CD11c labeled cells by Cell Quest™ Pro software (λex = 488 nm; λem = 525 nm band pass filter (bp)). After confirming CD11c+ BMDCs at day 7 or 8, the cells were activated and matured with R10 with 30 U/ml GM-CSF containing 1μg/ml lipopolysaccharide for 24h.

Bridging of BMDCs and Jurkat cells via Man/RGD NRs

T cell-mediated immune response via Man/RGD NRs was investigated according to different ratios or lengths of Man/RGD NRs. Jurkat T cell were plated on 24-well cell culture plates and serum-free media was fed (1×105 cells). After 1h, different amounts of Man/RGD NRs (length=1, 2, and 4μm; NR1, NR2, and NR4) were added and further incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C for 3h. The LPS-activated CD11c+ BMDCs in serum-free media (2×104 cells) was added. After 21h cultivation, IL-2 and IFN-γ levels secreted from the Jurkat T cells were measured by ELISA at 3h and 24h according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In order to confirm specific ligand-receptor interactions, mannose receptors on BMDC were blocked in 1.2 mM D-(+)-mannose for 15 min and RGD receptors (αvβ3 integrin) of Jurkat T cells were blocked by 0.8 mM RGD-PEG-COOH just before the bridging study.

Visualization of the bridging system

In order to visualize bridging of Jurkat T cell and BMDCs via Man/RGD NRs, Man/RGD NRs, Jurkat T cell, and BMDCs were fluorescently labeled and monitored by CLSM and SEM. Jurkat T cell in serum-free media (1×105 cells/ml) was dropped on a poly-L-lysine-coated glass and fluorescently-labeled Man/RGD NRs suspension in PBS (2μg/ml). After the 1h incubation, BMDCs in serum-free media (1×105 cells/ml) was added and incubated for 12h (BMDC:T cell:NR=1:1:10). Fluorescence labeling of anti-CD11c and anti-CD3 antibodies with Alexa Fluor® 405 carboxylic acid succinimidyl ester and Texas Red®-X succinimidyl ester were performed according to the manufacturer’s labeling protocol for proteins. For immunofluorescence staining, cells were blocked with a blocking buffer (10% FBS, 0.09% sodium azide in PBS) for 1h at 4°C and labeling with Alexa 405-anti CD11c (2.5μg/ml), Texas Red-anti CD3 (2.5μg/ml) in immunostaining buffer for 1h at 4°C, respectively. Cell were fixed with 2.5% (v/v) p-formaldehyde for 15 min and washed with PBS. Fluorescently-labeled Man/RGD NRs, Jurkat T cell, and BMDCs were visualized by CLSM. Texas Red labeled BMDCs and Alexa 405 labeled Jurkat T cells were individually excited at 532 nm and 405 nm and the emission signals were detected at bp 600–650 nm and bp 420–470 nm. FITC and Alexa 647 labeled RGD and mannose were excited and emitted with the same condition of Man/RGD NRs’ visualization by CLSM. Variable Pressure SEM (VP-SEM) was employed to minimize dissociation of NRs from the immune cells during the sample preparation according to the literatures 33. Briefly, Man/RGD NRs, Jurkat T cells, and BMDCs on a cover glass were fixed with 2.5% (v/v) p-formaldehyde for 20 min and washed. Cells were placed in a closed chamber for 1h, where osmium tetroxide solution (1%, w/v) was vaporized. The stained cells and their proximities with Man/RGD NRs were visualized with VP-SEM and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) of the nanorods was obtained (Carl Zeiss, Supra™ 55VP, Germany).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation in Korea.

References

- 1.Arnold M, Hirschfeld-Warneken VC, Lohmüller T, Heil P, Blümmel J, Cavalcanti-Adam EA, López-García Mn, Walther P, Kessler H, Geiger B, et al. Induction of Cell Polarization and Migration by a Gradient of Nanoscale Variations in Adhesive Ligand Spacing. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2063–2069. doi: 10.1021/nl801483w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalishwaralal K, Banumathi E, Ram Kumar Pandian S, Deepak V, Muniyandi J, Eom SH, Gurunathan S. Silver Nanoparticles Inhibit Vegf Induced Cell Proliferation and Migration in Bovine Retinal Endothelial Cells. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2009;73:51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson JM, Patterson JL, Vines JB, Javed A, Gilbert SR, Jun HW. Biphasic Peptide Amphiphile Nanomatrix Embedded with Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles for Stimulated Osteoinductive Response. ACS Nano. 2011;5:9463–9479. doi: 10.1021/nn203247m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krippner-Heidenreich A, Tubing F, Bryde S, Willi S, Zimmermann G, Scheurich P. Control of Receptor-Induced Signaling Complex Formation by the Kinetics of Ligand/Receptor Interaction. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44155–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang N, Chittasupho C, Duangrat C, Siahaan TJ, Berkland C. Plga Nanoparticle-Peptide Conjugate Effectively Targets Intercellular Cell-Adhesion Molecule-1. Bioconj Chem. 2007;19:145–152. doi: 10.1021/bc700227z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiong XB, Lavasanifar A. Traceable Multifunctional Micellar Nanocarriers for Cancer-Targeted Co-Delivery of Mdr-1 Sirna and Doxorubicin. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5202–5213. doi: 10.1021/nn2013707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weissleder R, Kelly K, Sun EY, Shtatland T, Josephson L. Cell-Specific Targeting of Nanoparticles by Multivalent Attachment of Small Molecules. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1418–23. doi: 10.1038/nbt1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bandyopadhyay A, Fine RL, Demento S, Bockenstedt LK, Fahmy TM. The Impact of Nanoparticle Ligand Density on Dendritic-Cell Targeted Vaccines. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3094–3105. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valencia PM, Hanewich-Hollatz MH, Gao W, Karim F, Langer R, Karnik R, Farokhzad OC. Effects of Ligands with Different Water Solubilities on Self-Assembly and Properties of Targeted Nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salem AK, Searson PC, Leong KW. Multifunctional Nanorods for Gene Delivery. Nat Mater. 2003;2:668–71. doi: 10.1038/nmat974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wildt B, Mali P, Searson PC. Electrochemical Template Synthesis of Multisegment Nanowires:3 Fabrication and Protein Functionalization†. Langmuir. 2006;22:10528–10534. doi: 10.1021/la061184j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park S, Son YJ, Leong KW, Yoo HS. Therapeutic Nanorods with Metallic Multi-Segments: Thermally Inducible Encapsulation of Doxorubicin for Anti-Cancer Therapy. Nano Today. 2012;7:76–84. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon YJ, Standley SM, Goh SL, Fréchet JMJ. Enhanced Antigen Presentation and Immunostimulation of Dendritic Cells Using Acid-Degradable Cationic Nanoparticles. J Controlled Release. 2005;105:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cui Z, Han SJ, Vangasseri DP, Huang L. Immunostimulation Mechanism of Lpd Nanoparticle as a Vaccine Carrier. Mol Pharm. 2004;2:22–28. doi: 10.1021/mp049907k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nembrini C, Stano A, Dane KY, Ballester M, van der Vlies AJ, Marsland BJ, Swartz MA, Hubbell JA. Nanoparticle Conjugation of Antigen Enhances Cytotoxic T-Cell Responses in Pulmonary Vaccination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:E989–E997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104264108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho EC, Zhang Q, Xia Y. The Effect of Sedimentation and Diffusion on Cellular Uptake of Gold Nanoparticles. Nat Nano. 2011;6:385–391. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim TH, Jin H, Kim HW, Cho MH, Cho CS. Mannosylated Chitosan Nanoparticle-Based Cytokine Gene Therapy Suppressed Cancer Growth in Balb/C Mice Bearing Ct-26 Carcinoma Cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1723–32. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshikawa T, Okada N, Oda A, Matsuo K, Matsuo K, Mukai Y, Yoshioka Y, Akagi T, Akashi M, Nakagawa S. Development of Amphiphilic Γ-Pga-Nanoparticle Based Tumor Vaccine: Potential of the Nanoparticulate Cytosolic Protein Delivery Carrier. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akagi T, Wang X, Uto T, Baba M, Akashi M. Protein Direct Delivery to Dendritic Cells Using Nanoparticles Based on Amphiphilic Poly(Amino Acid) Derivatives. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3427–3436. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fifis T, Mottram P, Bogdanoska V, Hanley J, Plebanski M. Short Peptide Sequences Containing Mhc Class I and/or Class Ii Epitopes Linked to Nano-Beads Induce Strong Immunity and Inhibition of Growth of Antigen-Specific Tumour Challenge in Mice. Vaccine. 2004;23:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chittasupho C, Shannon L, Siahaan TJ, Vines CM, Berkland C. Nanoparticles Targeting Dendritic Cell Surface Molecules Effectively Block T Cell Conjugation and Shift Response. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1693–1702. doi: 10.1021/nn102159g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blume G, Cevc G, Crommelin MDJA, Bakker-Woudenberg IAJM, Kluft C, Storm G. Specific Targeting with Poly(Ethylene Glycol)-Modified Liposomes: Coupling of Homing Devices to the Ends of the Polymeric Chains Combines Effective Target Binding with Long Circulation Times. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1993;1149:180–184. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips WT, Klipper RW, Awasthi VD, Rudolph AS, Cliff R, Kwasiborski V, Goins BA. Polyethylene Glycol-Modified Liposome-Encapsulated Hemoglobin: A Long Circulating Red Cell Substitute. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288:665–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haun JB, Hammer DA. Quantifying Nanoparticle Adhesion Mediated by Specific Molecular Interactions. Langmuir. 2008;24:8821–8832. doi: 10.1021/la8005844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fakhari A, Baoum A, Siahaan TJ, Le KB, Berkland C. Controlling Ligand Surface Density Optimizes Nanoparticle Binding to Icam-1. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:1045–1056. doi: 10.1002/jps.22342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waite CL, Roth CM. Binding and Transport of Pamam-Rgd in a Tumor Spheroid Model: The Effect of Rgd Targeting Ligand Density. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:2999–3008. doi: 10.1002/bit.23255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartneck M, Keul HA, Zwadlo-Klarwasser G, Groll Phagocytosis Independent Extracellular Nanoparticle Clearance by Human Immune Cells. Nano Lett. 2009;10:59–63. doi: 10.1021/nl902830x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arnida, Janát-Amsbury MM, Ray A, Peterson CM, Ghandehari H. Geometry and Surface Characteristics of Gold Nanoparticles Influence Their Biodistribution and Uptake by Macrophages. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;77:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheng KC, Kalkanidis M, Pouniotis DS, Esparon S, Tang CK, Apostolopoulos V, Pietersz GA. Delivery of Antigen Using a Novel Mannosylated Dendrimer Potentiates Immunogenicity in Vitro and in Vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:424–36. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cruz LJ, Tacken PJ, Fokkink R, Joosten B, Stuart MC, Albericio F, Torensma R, Figdor CG. Targeted Plga Nano- but Not Microparticles Specifically Deliver Antigen to Human Dendritic Cells Via Dc-Sign in Vitro. J Controlled Release. 2010;144:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dreaden EC, Mwakwari SC, Austin LA, Kieffer MJ, Oyelere AK, El-Sayed MA. Small Molecule-Gold Nanorod Conjugates Selectively Target and Induce Macrophage Cytotoxicity Towards Breast Cancer Cells. Small. 2012;8:2819–22. doi: 10.1002/smll.201200333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, Aya H, Deguchi M, Ikehara S, Muramatsu S, Steinman RM. Generation of Large Numbers of Dendritic Cells from Mouse Bone Marrow Cultures Supplemented with Granulocyte/Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joubert LM. Scanning Electron Microscopy: Bridging the Gap from Stem Cells to Hydrogels. Microsc Microanal. 2010;16:596–597. [Google Scholar]