Abstract

Rationale: Previous studies of risk factors for progression of lung disease in cystic fibrosis (CF) have suffered from limitations that preclude a comprehensive understanding of the determinants of CF lung disease throughout childhood. The epidemiologic component of the 27-year Wisconsin Randomized Clinical Trial of CF Neonatal Screening Project (WI RCT) afforded us a unique opportunity to evaluate the significance of potential intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for lung disease in children with CF.

Objectives: Describe the most important intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for progression of lung disease in children with CF.

Methods: Variables hypothesized at the onset of the WI RCT study to be determinants of the progression of lung disease and potential risk factors previously identified in the WI RCT study were assessed with multivariable generalized estimating equation models for repeated measures of chest radiograph scores and pulmonary function tests in the WI RCT cohort.

Measurements and Main Results: Combining all patients in the WI RCT, 132 subjects were observed for a mean of 16 years and contributed 1,579 chest radiographs, and 1,792 pulmonary function tests. The significant determinants of lung disease include genotype, poor growth, hospitalizations, meconium ileus, and infection with mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The previously described negative effect of female sex was not seen.

Conclusions: Modifiable extrinsic risk factors are the major determinants of progression of lung disease in children with CF. Better interventions to prevent or treat these risk factors may lead to improvements in lung health for children with CF.

Keywords: pulmonary function test, chest X-ray, newborn screening, nutrition, sex

Despite significant improvements in lung disease and survival in cystic fibrosis (CF) for successive birth cohorts, the progression of CF lung disease and early mortality occurs for most patients (1). The median age of death in the United States is 27 years, with a wide variation that includes a substantial number of deaths during childhood (1). Many risk factors are postulated as being important in the progression of CF lung disease and early mortality (2–10), but their relative impact over time has been uncertain. Other than our preliminary evaluation of genotype (11), previous studies of determinants of lung disease in CF have been cross-sectional or conducted over short time periods, and have involved patients diagnosed after variable delays in the era before newborn screening (NBS). Previous studies have typically focused on a limited number of intrinsic (e.g., meconium ileus) (9) or extrinsic (e.g., pulmonary exacerbations) (3) risk factors. Regarding sex, important studies have identified a “sex gap” with less morbidity and mortality for male patients (12, 13); these studies may have been confounded by delays in time to diagnosis for female patients and/or care-related biases that favored male patients (14, 15). In addition, studies have often collected data in the course of usual care (3, 12) and have not included patients monitored prospectively in a protocol-guided research setting (16). Finally, most previous studies have not included longitudinal quantitative chest imaging, which is more sensitive to progression of lung disease than traditional spirometry (17–22).

The initial hypothesis of the 27-year Wisconsin CF Neonatal Screening Project Randomized Clinical Trial (WI RCT) was that the introduction of NBS for CF would have minimal risks and potential benefits in terms of nutritional status and the progression of lung disease (23–25). Although we have previously described benefits to nutrition and cognition for patients identified after NBS (26–28), owing to patients identified after NBS as being exposed to Pseudomonas aeruginosa and having a higher percentage of severe genotypes, we have not observed benefits to CF lung disease (29), although others have described improvements in pulmonary outcomes associated with NBS (30, 31). The epidemiologic component of the WI RCT, however, afforded us the opportunity to evaluate the significance of prespecified potential intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors and to explore the importance of other variables tracked systematically for this cohort of patients (26, 32). Using all available data from the WI RCT, here we describe the significant risk factors for—or determinants of—progression of lung disease throughout childhood in patients monitored prospectively from early diagnosis through age 21 years, using protocol-driven monitoring and treatment regimens (32). Some of the results of this study were previously reported in abstract form (33, 34).

Methods

The design of the WI RCT is described in detail elsewhere (32). In summary, we performed an assessment of the potential benefits of early diagnosis after NBS in randomly identified children with CF managed prospectively. Blood specimens of newborns born in Wisconsin between 1985 and 1994 were assigned either to an early CF diagnosis group (screened patients) or to a standard diagnosis group (control patients) (32), which had an NBS test that was unreported unless the parents requested the data. To avoid selection bias, control patients were unblinded at 4 years of age and enrolled into the same evaluation and treatment protocol (32) used for the screened patients and control patients who were diagnosed symptomatically before age 4 years (35). A sweat chloride level of at least 60 mEq/L at one of Wisconsin’s two CF centers was required to establish the diagnosis, excluding patients with “atypical” or “nonclassical” CF. This investigation was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Wisconsin (Madison, WI) and the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin (Milwaukee, WI).

Patients were seen every 6 weeks for the first year of life and every 3 months thereafter and assessed by the evaluation and treatment protocol (32) we developed in 1984 and reviewed regularly. Parents reported cough frequency and sputum production at each visit. Respiratory cultures were obtained every 6 months (36). Spirometry measurements were begun when children reached 4 years of age, and recorded at least every 6 months only if they met strict quality control measures (25). Chest radiographs were obtained at the time of diagnosis, age 2 and 4 years, and annually thereafter and were scored using the Brasfield (BCXR) and Wisconsin chest X-ray (WCXR) scoring systems (37, 38). These films were labeled with codes and scored randomly by a pediatric pulmonologist and thoracic radiologist who were unaware of patient identity or age. Comparisons revealed more than satisfactory correlations (25, 37). Only the results using the WCXR scoring system, the more sensitive of the two methods (37), are reported here.

Statistical Analysis

For this study, we combined the subjects of the screened and control cohorts because group comparisons revealed no clinically meaningful differences in pulmonary outcomes after adjustment for confounders (29). Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with independent working correlations were used for repeated measures of WCXRs and FEV1. Initially, 18 variables hypothesized to be risk factors at the onset of the WI RCT study and risk factors for lung disease previously identified in the WI RCT study (see the online supplement) were assessed individually with a base model GEE, adjusted for age and age at the time of diagnosis. Factors significantly associated with FEV1 and/or WCXR were included in a multivariable model. To avoid collinearity, only one variable related to P. aeruginosa was kept in this multivariable model.

Exploratory analyses were conducted by adding other variables available in the WI RCT data set (see the online supplement) to the base model, and if statistically significant, to the multivariable model. All variables that remained statistically significant were included in a final, fully adjusted model. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

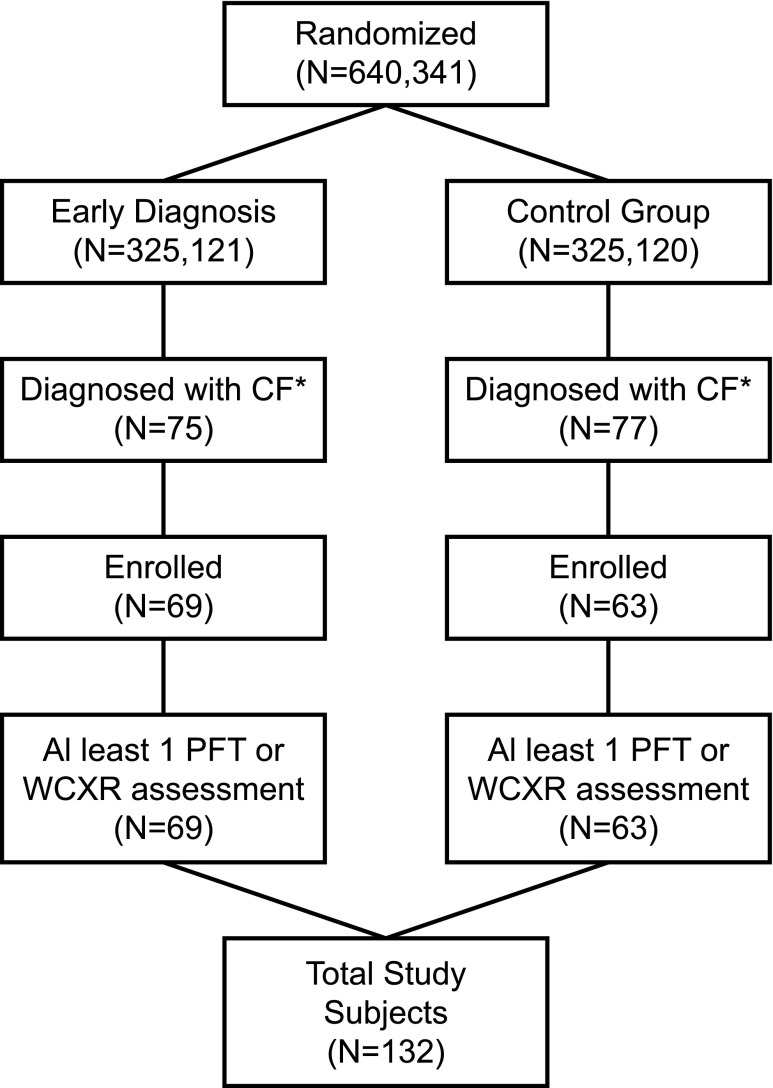

All of the 132 subjects with CF enrolled in the WI RCT contributed at least one of the 1,579 chest radiographs, and 1,792 high-quality pulmonary function tests (PFTs) (25), over a mean observation time of 16.0 years during the 27-year study (Figure 1). Five deaths occurred before age 21 years. These 132 subjects were generally representative of a typical CF population in the United States (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study cohort flowchart. *Sweat test result at least 60 mmol/L and signs/symptoms of cystic fibrosis (CF). PFT = pulmonary function test; WCXR = Wisconsin chest X-ray.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study subjects

| Characteristic | Category | n (%) (total n = 132) |

|---|---|---|

| Patient group | Control | 63 (48) |

| Screened | 69 (52) | |

| Center | Madison | 70 (53) |

| Milwaukee | 62 (47) | |

| Sex | Male | 78 (59) |

| Female | 54 (41) | |

| Genotype | F508del/F508del | 70 (57) |

| F508del/any CFTR class I–III mutation | 35 (29) | |

| Any class IV or V mutations | 17 (14)* | |

| Pancreatic status | Pancreatic sufficiency | 21 (16)† |

| Pancreatic insufficiency | 107 (84) | |

| Meconium ileus | No | 103 (78) |

| Yes | 29 (22) |

Definition of abbreviation: CFTR = cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator.

No subjects had two class IV or V mutations. Genotype was unknown for 10 subjects.

Pancreatic status was determined principally by fat malabsorption studies, as described in detail elsewhere (26), at a mean age of 4 years and was unknown for four subjects.

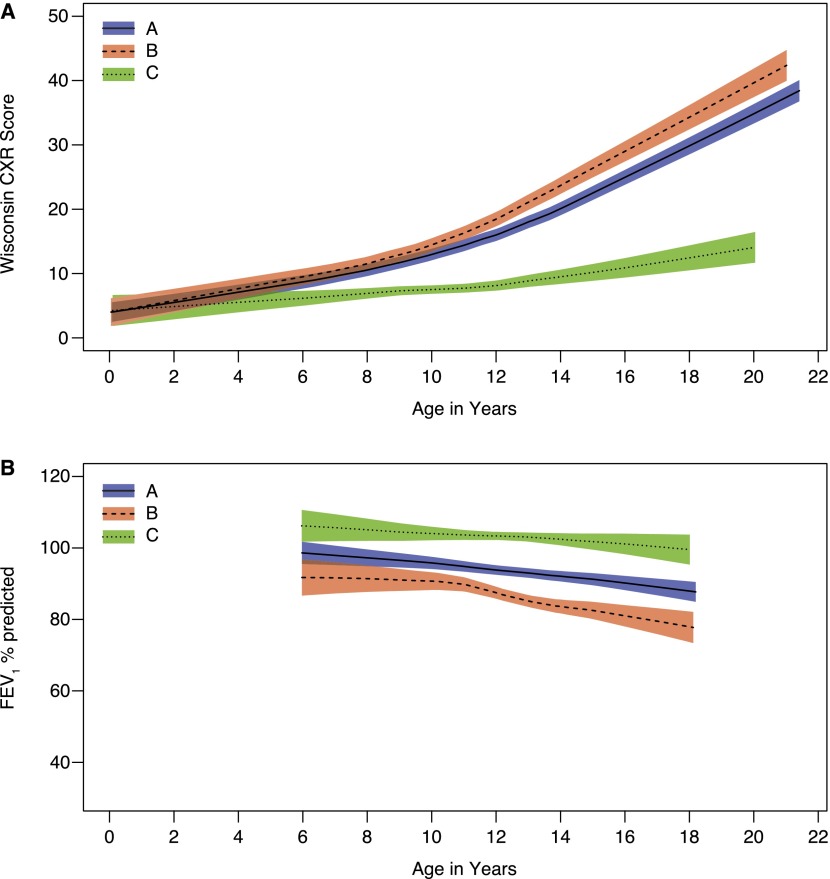

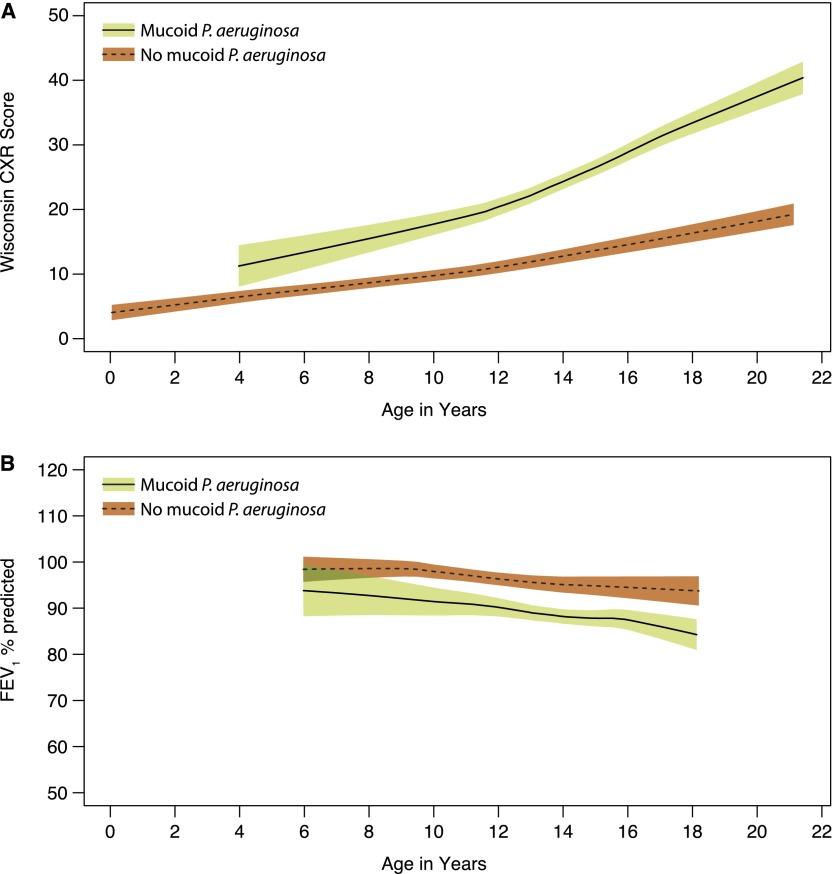

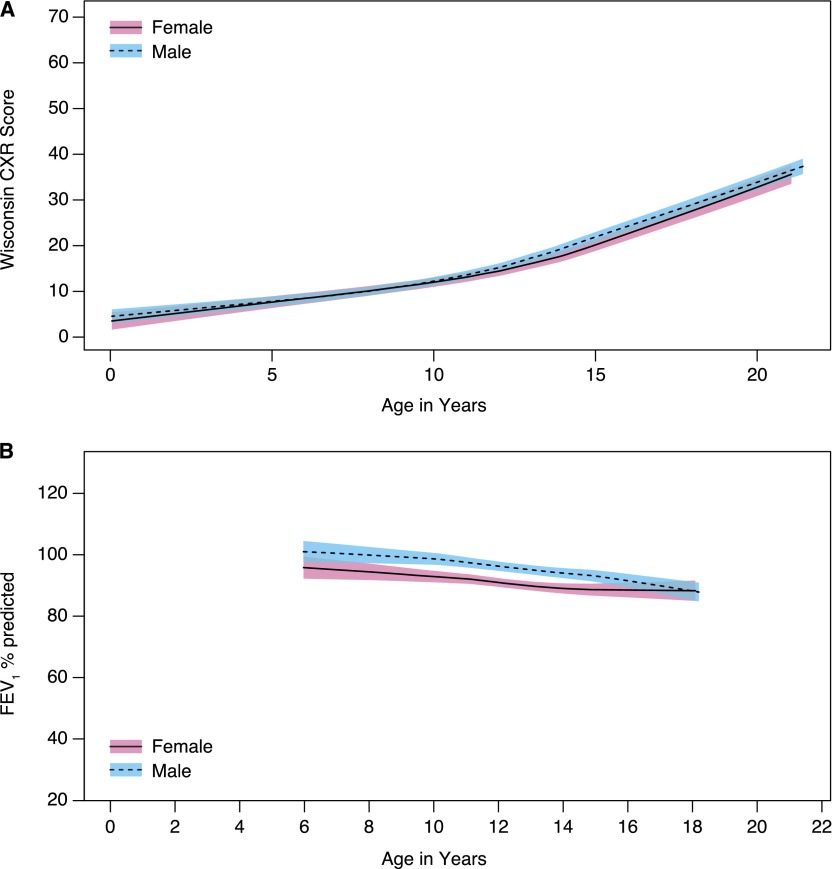

The difference in FEV1 expressed as a percentage of the predicted value (FEV1 % predicted) and WCXR scores for each of the 18 prespecified risk factors, estimated with GEE models adjusted only for age and age at the time of diagnosis, is listed in Table 2. In this simple analysis, age, genotype (Figure 2), height-for-age percentile, age (wk) at diagnosis, having been recently hospitalized, meconium ileus, and mucoid P. aeruginosa (ever having a positive culture [Figure 3], the duration of infection, and the age at first positive culture) were significantly associated with severity of CF lung disease. These variables were then included together in a multivariable GEE model to estimate the difference in FEV1 % predicted and WCXR for each risk factor, adjusting for other significant covariates (see Table E1 in the online supplement). In the model that estimated FEV1 % predicted, a history of meconium ileus and the age at diagnosis were no longer significantly associated with severity of CF lung disease. In addition, although the estimated difference in FEV1 % predicted between subjects with homozygous F508del and F508del/any CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) class I–III mutation was statistically significant in the simple analysis (difference [SE] of 6.72 [3.20]; P = 0.04) (Figure 2), this difference was not statistically significant when included in the multivariable model (difference [SE] of 4.95 [2.79]; P = 0.08). In the model that estimated WCXR, age at diagnosis was no longer significantly associated with severity of CF lung disease. The estimated difference in WCXR between subjects with homozygous F508del and F508del/any CFTR class I–III mutation was not statistically significant in the simple or multivariable GEE model (difference [SE] in the multivariable model of 1.26 [1.67]; P = 0.5). It should be noted that sex was not a significant risk factor for either FEV1 % predicted or WCXR (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Estimates of the differences in FEV1 % predicted and Wisconsin chest X-ray score, using generalized estimating equation models with independent working correlation structures for prespecified risk factors for progression of lung disease, in models adjusted only for age and age at the time of diagnosis

| FEV1 % Predicted |

WCXR Score |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factor | Difference (SE) | P Value | Difference (SE) | P Value |

| Age, yr | −1.23 (0.19) | <0.001 | 1.62 (0.11) | <0.001 |

| Sex (Ref: Male) | −3.55 (2.81) | 0.2 | −0.62 (1.65) | 0.7 |

| Genotype (Ref: Any CFTR class IV or V mutation) | ||||

| F508del/F508del | −6.80 (4.07) | 0.09 | 5.05 (1.46) | <0.001 |

| F508del/any CFTR class I–III mutation | −13.52 (4.70) | 0.004 | 6.35 (2.06) | 0.002 |

| Maternal education level (Ref: Did not graduate from high school) | −1.23 (4.20) | 0.8 | −3.96 (2.71) | 0.1 |

| Milwaukee CF center (Ref: Madison) | 1.79 (2.84) | 0.5 | 0.81 (1.58) | 0.6 |

| Old hospital | −5.29 (3.68) | 0.2 | 2.29 (1.85) | 0.2 |

| Pancreatic insufficiency | −4.88 (4.95) | 0.3 | 1.91 (2.96) | 0.5 |

| Height for age < 10th percentile | −12.37 (3.56) | <0.001 | 5.49 (1.78) | 0.002 |

| Age (wk) at diagnosis | 0.04 (0.01) | <0.001 | −0.03 (0.01) | <0.001 |

| Recent hospitalization* | −11.48 (2.70) | <0.001 | 7.98 (1.17) | <0.001 |

| Meconium ileus | −8.33 (3.34) | 0.01 | 0.41 (2.04) | 0.8 |

| Staphylococcus aureus, >1 positive respiratory culture | 0.99 (4.75) | 0.8 | −1.29 (0.81) | 0.1 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa, ever-positive respiratory culture | 3.07 (3.26) | 0.4 | −1.15 (1.35) | 0.4 |

| P. aeruginosa, yr since initial positive culture | −0.16 (0.38) | 0.7 | 0.45 (0.29) | 0.1 |

| P. aeruginosa, age at initial positive culture | 0.05 (0.34) | 0.9 | −0.24 (0.23) | 0.3 |

| Mucoid P. aeruginosa, ever-positive respiratory culture | −5.13 (2.86) | 0.07 | 5.86 (2.00) | 0.004 |

| Mucoid P. aeruginosa, years since initial positive culture | −1.33 (0.55) | 0.02 | 1.35 (0.36) | <0.001 |

| Mucoid P. aeruginosa, age at initial positive culture | 0.52 (0.49) | 0.3 | −0.80 (0.24) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: CFTR = cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; WCXR = Wisconsin chest X-ray.

Any hospitalizations within the 6 months before a measurement of FEV1 or the same age as WCXR.

Figure 2.

(A) Wisconsin chest X-ray (WCXR) scores and (B) FEV1 % predicted for patients with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) genotype F508del/F508del (group A), F508del/any class I–III mutation (group B), and any class IV–V mutation (group C). The range of WCXR scores was from 0 to 100, with 0 the best and 100 the worst. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

(A) Wisconsin chest X-ray (WCXR) scores and (B) FEV1 % predicted for patients who ever or never had a positive respiratory culture for mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals.

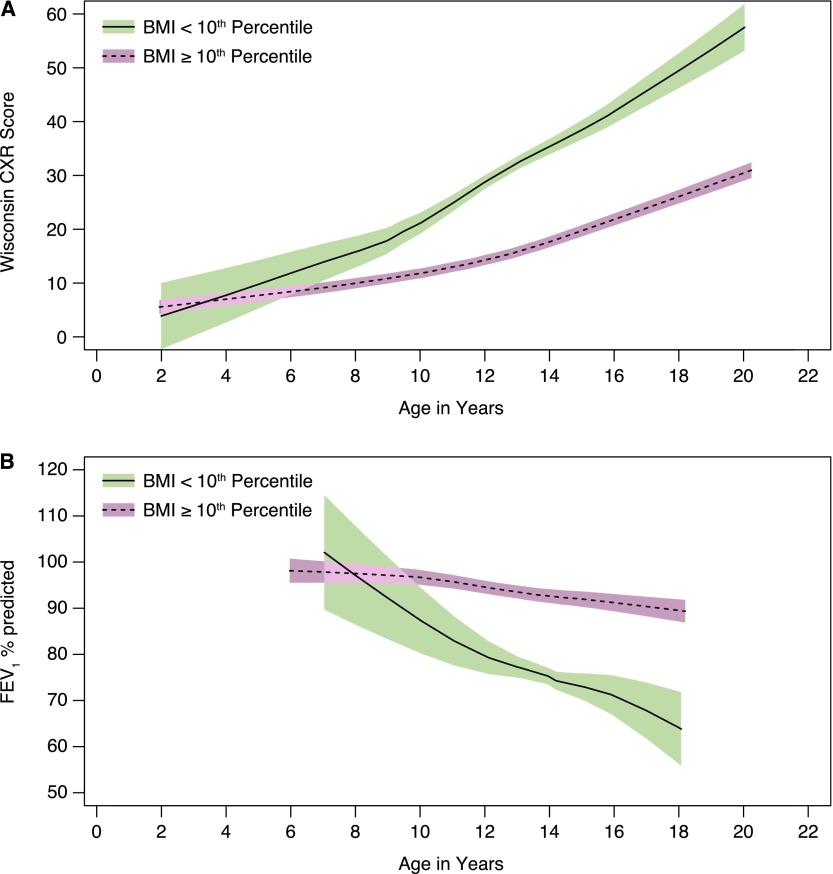

Figure 4.

(A) Wisconsin chest X-ray (WCXR) scores and (B) FEV1 % predicted for male and female patients. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Other variables that were tracked in the WI RCT were evaluated individually in GEE models adjusted only for age and age at diagnosis. Those variables that were significantly associated with FEV1 % predicted and/or WCXR are listed in Table E2. Although females acquired mucoid P. aeruginosa slightly earlier than males (median age of 11.5 yr, as compared with 14.0 yr in males; P = 0.05), the interaction between sex and age at acquisition of P. aeruginosa was not significantly associated with either FEV1 % predicted or WCXR. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), CF-related diabetes, infection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and liver disease were not tracked routinely for the WI RCT cohort; the incidence of these complications was low in the WI RCT study population. Only 3 patients had a sputum culture positive for Burkholderia cepacia complex on a total of 11 cultures. Socioeconomic status (SES) was tracked by median income by ZIP code and maternal education only. Chronic use of dornase alfa, inhaled tobramycin, azithromycin, and hypertonic saline (each of which was introduced when they became available in the United States) was significantly associated with worsening CF lung disease. These associations were most consistent with indication bias (more medications are prescribed for sicker patients) and these therapies were not considered for additional analysis.

Variables significant in this base model were then added individually to the multivariable models in Table E1. The variables that remained statistically significantly associated with FEV1 % predicted and/or WCXR were then included in a final model (Table 3). Only one variable for nutrition and P. aeruginosa was included to avoid collinearity. The total lifetime number of hospitalizations had a weak association with FEV1 % predicted and WCXR in adjusted GEE models, and therefore this variable was removed in favor of the recent hospitalizations variable. For FEV1 % predicted, meconium ileus became significantly associated and body mass index (BMI)-for-age percentile replaced height-for-age percentile as the most significantly associated nutrition variable (Figure 5). For WCXR, meconium ileus remained nonsignificant and BMI-for-age percentile replaced height-for-age percentile as the most significantly associated nutrition variable (Figure 5). The estimated difference between subjects with homozygous F508del and F508del/any CFTR class I–III mutation was still not statistically significant when added to the final model for FEV1 % predicted (difference [SE] of 5.33 [2.78]; P = 0.06) or WCXR (difference [SE] of 1.11 [1.64]; P = 0.5). Auscultation of crackles and parental report of daily sputum or cough were also significantly associated with FEV1 % predicted and WCXR, adjusting for the other covariates in the model (Table E2). However, these variables were not included in the final model because (1) there was a correlation between ever having a positive culture for mucoid P. aeruginosa and daily cough (Pearson correlation r = 0.24, P < 0.001), daily sputum (r = 0.23, P < 0.001), and auscultation of crackles (r = 0.13, P < 0.001); (2) adding these variables to our final model did not substantially improve model fit according to the quasi-Akaike information criterion (QIC) (39); and most importantly, (3) these signs and symptoms of lung disease are actually indicators of lung disease, and not determinants of lung disease.

Table 3.

Estimates of the differences in FEV1 % predicted and Wisconsin chest X-ray, using multivariable generalized estimating equation models with independent working correlation structures, adjusted for other significant risk factors for progression of lung disease

| FEV1 % Predicted |

WCXR Score |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factor | Difference (SE) | P Value | Difference (SE) | P Value |

| Age, yr | −0.75 (0.19) | <0.001 | 1.34 (0.14) | <0.001 |

| Genotype (Ref: Any CFTR class IV or V) | ||||

| F508del/F508del | −5.26 (3.55) | 0.1 | 4.81 (1.59) | 0.002 |

| F508del/any CFTR class I–III | −10.59 (4.03) | 0.009 | 6.26 (2.14) | 0.004 |

| BMI for age < 10th percentile | −15.75 (4.78) | 0.001 | 13.19 (5.11) | 0.01 |

| Recent hospitalization* | −9.57 (2.36) | <0.001 | 5.87 (1.16) | <0.001 |

| Meconium ileus | −6.62 (2.85) | 0.02 | −0.36 (1.80) | 0.8 |

| Mucoid P. aeruginosa, ever-positive respiratory culture | −4.45 (2.43) | 0.07 | 4.96 (1.79) | 0.006 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CFTR = cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; WCXR = Wisconsin chest X-ray.

Any hospitalizations within the 6 months before a measurement of FEV1 or the same age as WCXR.

Figure 5.

(A) Wisconsin chest X-ray (WCXR) scores and (B) FEV1 % predicted for patients with body mass index (BMI) less than the 10th percentile for age and patients with BMI equal to or exceeding the 10th percentile for age. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Early diagnosis of CF after NBS provides an opportunity for better care but does not ensure better outcomes (40), making NBS necessary but not sufficient to optimize outcomes for the majority of patients with CF (41). In our comparisons of screened patients identified through NBS and control patients identified with symptoms of CF, there have been no significant differences in severity of lung disease, despite significant benefits in nutrition and cognitive function for patients identified after NBS (26–28). Our comparisons between the screened and control groups have been complicated by center differences and dissimilar group characteristics, despite a large randomization process that was proven to be statistically valid (35). Besides the assessment of the effect of NBS on CF, it was recognized during the design of the WI RCT that additional information regarding the progression of lung disease in CF could be obtained. Therefore, key demographic, nutrition, and disease severity variables were tracked to better understand CF lung disease. In addition, early reports on the WI RCT cohort identified additional risk factors for progression of lung disease in young children with CF: meconium ileus (9), S. aureus (25), P. aeruginosa (23), and mucoid P. aeruginosa (42).

Now, taking advantage of the longest cohort study in CF, our longitudinal observations of all patients monitored in our 27-year study show that aside from genotype and meconium ileus, extrinsic risk factors that can be modified—namely, poor growth, hospitalizations, and infection with mucoid P. aeruginosa—are the major determinants of progression of lung disease throughout childhood in CF. Efforts to aggressively support nutrition after early diagnosis with NBS (40), the use of chronic medications that reduce pulmonary exacerbations (43–49), and early eradication of P. aeruginosa (50, 51) are likely to have long-lasting impacts in children with CF.

Previous studies (4, 12) have suggested that female sex is a risk factor for more severe lung disease, but we did not find such an effect in our study. This may be attributable to the similar early age of diagnosis for males and females in our study, in contrast to other cohorts, where females are typically diagnosed at older ages than male patients (52). This delay may result in a decreased likelihood of females with CF reaching the age of 40 years (13). Others have similarly not seen this sex effect, which may disappear with the introduction of NBS (53, 54), or with more aggressive care such as that provided in our standardized treatment protocols (55, 56). Removing these potential confounding effects is important in determining whether there are true differences in outcomes between males and females with CF related to sex as an intrinsic risk factor, or whether any sex differences can instead be explained by biases such as differences in the societal acceptance of being underweight for males versus females (14, 15).

The assessments of risk factors using FEV1 and WCXR were generally in agreement, with poor growth being the strongest risk factor for both measures of severity of lung disease. Differences for patients with different genotypes and mucoid P. aeruginosa were more significant on WCXR, whereas meconium ileus was a more significant risk factor for lower FEV1. These results extend our preliminary observations that characterization of lung disease by genotype is possible with quantitative chest radiograph scoring, but not with clinical symptoms or PFTs (11). We (57) and others (58) have previously described changes in chest CT scores associated with P. aeruginosa, without corresponding changes in FEV1. The reason for these differences is not known, although perhaps the improved sensitivity of chest imaging in detecting structural changes (17, 19, 21) that are associated with chronic inflammation (59, 60) and infection with mucoid P. aeruginosa (57) and genotype (60, 61) explains the more severe WCXR scores, and factors influencing growth (62) and corresponding lung growth (9) after meconium ileus explain the differences seen in FEV1.

Aside from finding no evidence of a “sex gap,” our results are otherwise generally comparable to previous reports on the risk factors for progression of lung disease, and have the additional strengths of including longitudinal observations recorded prospectively throughout childhood and quantitative chest X-ray scoring as a measure of structural lung disease. Using data from the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis (ESCF), in which only a small minority of patients was diagnosed through NBS (16), Konstan and colleagues also showed that independent risk factors for decline in FEV1 include infection with P. aeruginosa, low weight for age, and pulmonary exacerbations treated with intravenous antibiotics (2). Their mean observation period was 4.4 years, compared with a mean of 16 years for our study. Schechter and colleagues showed that patients in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry (CFFPR) with worse SES based on Medicaid insurance status had more severe lung disease over a median observation period of 8 years (6). SES was assessed in our cohort using median income by ZIP code and maternal education, and we did not observe this as a risk factor. Because the WI RCT only enrolled patients from the state of Wisconsin, the range of variation in SES may have been narrower than in the national CFFPR population. In addition, regular clinic visits were ensured by protocol-guided management that required at least quarterly evaluations, and reimbursed parents for travel.

Our study has several limitations. Although patients were evaluated and managed prospectively, the retrospective nature of this analysis prevents us from determining causality, for example, the severity of lung disease may lead to worsening BMI, or vice versa. Because one of the original aims of the WI RCT was to avoid malnutrition, our analysis did not address the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation goal of maintaining BMI at greater than the 50th percentile (63). In addition, several potential risk factors for severity of lung disease were either underrepresented in this cohort (e.g., MRSA [64], ABPA [10]) or not monitored in our cohort (e.g., CF-related diabetes [65], genetic modifiers [7, 8], or prescriptions for oral antibiotics [66]). The reasons for hospitalizations were not recorded for this study, and therefore the effects of hospitalizations for pulmonary exacerbations may be even larger than reported here. Although we did not find a difference in lung disease for patients who were pancreatic insufficient, our comparisons were limited by having only 16 patients who were pancreatic sufficient in the initial cohort, and even fewer who contributed data all the way through age 21 years. In addition, pancreatic status is confounded by genotype and potentially by growth; because the patients with pancreatic insufficiency in our RCT received aggressive nutritional support, most avoided poor growth (67), in contrast to previous studies comparing lung disease in sufficient and insufficient patients (68). The difference in FEV1 % predicted between the homozygous F508del and F508del/any CFTR class I–III genotypes did not achieve statistical significance despite a possible clinically meaningful difference. It is unclear why subjects with F508del/any CFTR class I–III genotypes had apparently more severe lung disease by spirometry than the subjects who were homozygous for F508del, but we can speculate that this could be due to intrinsic factors such as genetic modifiers (7), and/or greater exposure to extrinsic risks such as early acquisition of P. aeruginosa. Further analysis is ongoing to understand these differences. Given longitudinal observations over a mean of 16 years, it is unlikely that any other possible type II errors occurred for clinically meaningful determinants of lung disease. Our assessment of the impact of chronic therapies with dornase alfa, inhaled tobramycin, hypertonic saline, and azithromycin is limited given that these medications were not available for part of the time period of the WI RCT study. Thus, we are unable to conduct an analysis to overcome the indication bias demonstrated in our exploration of these variables.

Nonetheless, from a 27-year prospective study of children with CF identified early after NBS or the appearance of symptoms, we have identified the significant risk factors for progression of structural and functional lung disease. We believe that this project is especially valuable because the long-term prospective, systematic follow-up using high-quality repeated measures from the time of diagnosis at a generally young age, combined with protocol-guided management, allowed us to assess potential determinants in an unbiased fashion and to avoid most confounders. Perhaps the best example of this advantage is our ability to assess sex comprehensively and provide evidence refuting the “gap” concept that arose in retrospective studies from the 1990s (12).

The clinical implications of our data are quite apparent. Patients with the extrinsic risk factors reported herein may be targeted for more aggressive therapy, including the exciting new therapies that are becoming available (69). Efforts directed specifically at supporting nutrition, especially the prevention of poor growth in early life, adherence (70) to the chronic medications that reduce pulmonary exacerbations, and early eradication of P. aeruginosa are likely to have long-lasting impacts in children with CF. In concert with NBS, and the lessons learned regarding infection control in our study, we have a significant opportunity to slow the progression of CF lung disease and alter the life course of patients with CF.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank HuiChuan Lai and Andrew Bush for assistance with critical review of this manuscript and interpretation of results. The authors thank the patients and the families who participated in this project and remain grateful to the entire Wisconsin Randomized Clinical Trial of CF Neonatal Screening Project team in Madison and Milwaukee.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK34108 and DK34108-23S1 Revised, and by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation grant SANDERS11A0.

Author Contributions: Conception: D.B.S., Z.L., A.L., M.J.R., H.L., C.F., P.M.F.; design: D.B.S., Z.L., A.L., M.J.R., H.L., C.F., P.M.F.; analysis: D.B.S., Z.L., A.L., M.J.R., H.L., J.C., P.M.F.; interpretation: D.B.S., Z.L., A.L., M.J.R., H.L., J.C., C.F., P.M.F.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents online at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Cystic Fibrosis Foundation 2011 patient registry annual data report Bethesda, MD: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; 2012[accessed 2013 Aug 26]Available from: http://www.cff.org/UploadedFiles/research/ClinicalResearch/2011-Patient-Registry.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konstan M, Morgan W, Butler S, Pasta D, Craib M, Silva S, Stokes D, Wohl M, Wagener J, Regelmann W, et al. Risk factors for rate of decline in forced expiratory volume in one second in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis J Pediatr 2007151134–139.139.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waters V, Stanojevic S, Atenafu EG, Lu A, Yau Y, Tullis E, Ratjen F. Effect of pulmonary exacerbations on long-term lung function decline in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:61–66. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00159111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zemel BS, Jawad AF, FitzSimmons S, Stallings VA. Longitudinal relationship among growth, nutritional status, and pulmonary function in children with cystic fibrosis: analysis of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation National CF Patient Registry. J Pediatr. 2000;137:374–380. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.107891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders DB, Bittner RC, Rosenfeld M, Redding GJ, Goss CH. Pulmonary exacerbations are associated with subsequent FEV1 decline in both adults and children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:393–400. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schechter MS, Shelton BJ, Margolis PA, Fitzsimmons SC. The association of socioeconomic status with outcomes in cystic fibrosis patients in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1331–1337. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.6.9912100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drumm ML, Konstan MW, Schluchter MD, Handler A, Pace R, Zou F, Zariwala M, Fargo D, Xu A, Dunn JM, et al. Gene Modifier Study Group. Genetic modifiers of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1443–1453. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levy H, Murphy A, Zou F, Gerard C, Klanderman B, Schuemann B, Lazarus R, García KC, Celedón JC, Drumm M, et al. IL1B polymorphisms modulate cystic fibrosis lung disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:580–593. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z, Lai HJ, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Rock MJ, Splaingard ML, Farrell PM. Longitudinal pulmonary status of cystic fibrosis children with meconium ileus. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;38:277–284. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kraemer R, Deloséa N, Ballinari P, Gallati S, Crameri R. Effect of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis on lung function in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1211–1220. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-423OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braun AT, Farrell PM, Ferec C, Audrezet MP, Laxova A, Li Z, Kosorok MR, Rosenberg MA, Gershan WM. Cystic fibrosis mutations and genotype–pulmonary phenotype analysis. J Cyst Fibros. 2006;5:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corey M, Edwards L, Levison H, Knowles M. Longitudinal analysis of pulmonary function decline in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 1997;131:809–814. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nick JA, Chacon CS, Brayshaw SJ, Jones MC, Barboa CM, St Clair CG, Young RL, Nichols DP, Janssen JS, Huitt GA, et al. Effects of gender and age at diagnosis on disease progression in long-term survivors of cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:614–626. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0092OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Truby H, Paxton AS. Body image and dieting behavior in cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E92. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willis E, Miller R, Wyn J. Gendered embodiment and survival for young people with cystic fibrosis. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:1163–1174. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Padman R, McColley SA, Miller DP, Konstan MW, Morgan WJ, Schechter MS, Ren CL, Wagener JS Investigators and Coordinators of the Epidemiologic Study of Cystic Fibrosis. Infant care patterns at epidemiologic study of cystic fibrosis sites that achieve superior childhood lung function. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e531–e537. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanders DB, Li Z, Rock MJ, Brody AS, Farrell PM. The sensitivity of lung disease surrogates in detecting chest CT abnormalities in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47:567–573. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders DB, Li Z, Brody AS, Farrell PM. Chest computed tomography scores of severity are associated with future lung disease progression in children with cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:816–821. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201105-0816OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brody AS, Klein JS, Molina PL, Quan J, Bean JA, Wilmott RW. High-resolution computed tomography in young patients with cystic fibrosis: distribution of abnormalities and correlation with pulmonary function tests. J Pediatr. 2004;145:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Jong PA, Lindblad A, Rubin L, Hop WC, de Jongste JC, Brink M, Tiddens HA. Progression of lung disease on computed tomography and pulmonary function tests in children and adults with cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2006;61:80–85. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.045146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Jong PA, Nakano Y, Lequin MH, Mayo JR, Woods R, Paré PD, Tiddens HA. Progressive damage on high resolution computed tomography despite stable lung function in cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2004;23:93–97. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00006603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terheggen-Lagro SW, Arets HG, van der Laag J, van der Ent CK. Radiological and functional changes over 3 years in young children with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:279–285. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00051406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosorok MR, Zeng L, West SE, Rock MJ, Splaingard ML, Laxova A, Green CG, Collins J, Farrell PM. Acceleration of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis after Pseudomonas aeruginosa acquisition. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;32:277–287. doi: 10.1002/ppul.2009.abs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrell PM, Li Z, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Green CG, Collins J, Lai HC, Rock MJ, Splaingard ML. Bronchopulmonary disease in children with cystic fibrosis after early or delayed diagnosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1100–1108. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-434OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farrell PM, Li Z, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Green CG, Collins J, Lai HC, Makholm LM, Rock MJ, Splaingard ML. Longitudinal evaluation of bronchopulmonary disease in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36:230–240. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farrell PM, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Shen G, Koscik RE, Bruns WT, Splaingard M, Mischler EH Wisconsin Cystic Fibrosis Neonatal Screening Study Group. Nutritional benefits of neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:963–969. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koscik RL, Farrell PM, Kosorok MR, Zaremba KM, Laxova A, Lai HC, Douglas JA, Rock MJ, Splaingard ML. Cognitive function of children with cystic fibrosis: deleterious effect of early malnutrition. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1549–1558. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.6.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoff SM, Ahn HY, Davis L, Lai H Wisconsin CF Neonatal Screening Group. Temporal associations among energy intake, plasma linoleic acid, and growth improvement in response to treatment initiation after diagnosis of cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2006;117:391–400. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tluczek A, Becker T, Laxova A, Grieve A, Racine Gilles CN, Rock MJ, Gershan WM, Green CG, Farrell PM. Relationships among health-related quality of life, pulmonary health, and newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2011;140:170–177. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenfeld M. Overview of published evidence on outcomes with early diagnosis from large US observational studies. J Pediatr. 2005;147(3 Suppl):S11–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dankert-Roelse JE, Mérelle ME. Review of outcomes of neonatal screening for cystic fibrosis versus non-screening in Europe. J Pediatr. 2005;147(3 Suppl):S15–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrell PM Wisconsin Cystic Fibrosis Neonatal Screening Study Group. Improving the health of patients with cystic fibrosis through newborn screening. Adv Pediatr. 2000;47:79–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farrell P, Li Z, Sanders D, Lai H, Laxova A, Rock M, Levy H, Collins J, Férec C. Determinants of lung disease progression in children with CF [abstract] J Cyst Fibros. 2012;11(1 Suppl):S6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders DB, Li Z, Laxova A, Rock MJ, Farrell PM. Determinants of lung disease in children with CF [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:A1175. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farrell PM, Kosorok MR, Rock MJ, Laxova A, Zeng L, Lai HC, Hoffman G, Laessig RH, Splaingard ML Wisconsin Cystic Fibrosis Neonatal Screening Study Group. Early diagnosis of cystic fibrosis through neonatal screening prevents severe malnutrition and improves long-term growth. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kosorok MR, Jalaluddin M, Farrell PM, Shen G, Colby CE, Laxova A, Rock MJ, Splaingard M. Comprehensive analysis of risk factors for acquisition of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in young children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1998;26:81–88. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199808)26:2<81::aid-ppul2>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koscik RE, Kosorok MR, Farrell PM, Collins J, Peters ME, Laxova A, Green CG, Zeng L, Rusakow LS, Hardie RC, et al. Wisconsin cystic fibrosis chest radiograph scoring system: validation and standardization for application to longitudinal studies. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2000;29:457–467. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(200006)29:6<457::aid-ppul8>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brasfield D, Hicks G, Soong S, Tiller RE. The chest roentgenogram in cystic fibrosis: a new scoring system. Pediatrics. 1979;63:24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan W. Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2001;57:120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai HJ, Shoff SM, Farrell PM Wisconsin Cystic Fibrosis Neonatal Screening Group. Recovery of birth weight z score within 2 years of diagnosis is positively associated with pulmonary status at 6 years of age in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2009;123:714–722. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balfour-Lynn IM. Newborn screening for cystic fibrosis: evidence for benefit. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:7–10. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.115832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Z, Kosorok MR, Farrell PM, Laxova A, West SE, Green CG, Collins J, Rock MJ, Splaingard ML. Longitudinal development of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and lung disease progression in children with cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 2005;293:581–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuchs HJ, Borowitz DS, Christiansen DH, Morris EM, Nash ML, Ramsey BW, Rosenstein BJ, Smith AL, Wohl ME Pulmozyme Study Group. Effect of aerosolized recombinant human DNase on exacerbations of respiratory symptoms and on pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:637–642. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409083311003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konstan MW, Byard PJ, Hoppel CL, Davis PB. Effect of high-dose ibuprofen in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:848–854. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503303321303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ramsey BW, Pepe MS, Quan JM, Otto KL, Montgomery AB, Williams-Warren J, Vasiljev-K M, Borowitz D, Bowman CM, Marshall BC, et al. Cystic Fibrosis Inhaled Tobramycin Study Group. Intermittent administration of inhaled tobramycin in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:23–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Elkins MR, Robinson M, Rose BR, Harbour C, Moriarty CP, Marks GB, Belousova EG, Xuan W, Bye PT National Hypertonic Saline in Cystic Fibrosis (NHSCF) Study Group. A controlled trial of long-term inhaled hypertonic saline in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:229–240. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCoy KS, Quittner AL, Oermann CM, Gibson RL, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Montgomery AB. Inhaled aztreonam lysine for chronic airway Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:921–928. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1804OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saiman L, Anstead M, Mayer-Hamblett N, Lands LC, Kloster M, Hocevar-Trnka J, Goss CH, Rose LM, Burns JL, Marshall BC, et al. AZ0004 Azithromycin Study Group. Effect of azithromycin on pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis uninfected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1707–1715. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, Tullis E, Bell SC, Dřevínek P, Griese M, McKone EF, Wainwright CE, Konstan MW, et al. VX08-770-102 Study Group. A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1663–1672. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mayer-Hamblett N, Kronmal RA, Gibson RL, Rosenfeld M, Retsch-Bogart G, Treggiari MM, Burns JL, Khan U, Ramsey BW EPIC Investigators. Initial Pseudomonas aeruginosa treatment failure is associated with exacerbations in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47:125–134. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Treggiari MM, Retsch-Bogart G, Mayer-Hamblett N, Khan U, Kulich M, Kronmal R, Williams J, Hiatt P, Gibson RL, Spencer T, et al. Early Pseudomonas Infection Control (EPIC) Investigators. Comparative efficacy and safety of 4 randomized regimens to treat early Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:847–856. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lai HC, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Makholm LM, Farrell PM. Delayed diagnosis of US females with cystic fibrosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:165–173. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Viviani L, Bossi A, Assael BM Italian Registry for Cystic Fibrosis Collaborative Group. Absence of a gender gap in survival: an analysis of the Italian registry for cystic fibrosis in the paediatric age. J Cyst Fibros. 2011;10:313–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Assael BM, Castellani C, Ocampo MB, Iansa P, Callegaro A, Valsecchi MG. Epidemiology and survival analysis of cystic fibrosis in an area of intense neonatal screening over 30 years. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:397–401. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Verma N, Bush A, Buchdahl R. Is there still a gender gap in cystic fibrosis? Chest. 2005;128:2824–2834. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martin B, Schechter MS, Jaffe A, Cooper P, Bell SC, Ranganathan S. Comparison of the US and Australian cystic fibrosis registries: the impact of newborn screening. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e348–e355. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Farrell PM, Collins J, Broderick LS, Rock MJ, Li Z, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Gershan WM, Brody AS. Association between mucoid Pseudomonas infection and bronchiectasis in children with cystic fibrosis. Radiology. 2009;252:534–543. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2522081882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robinson TE, Leung AN, Chen X, Moss RB, Emond MJ. Cystic fibrosis HRCT scores correlate strongly with Pseudomonas infection. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44:1107–1117. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Davis SD, Fordham LA, Brody AS, Noah TL, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Qaqish BF, Yankaskas BC, Johnson RC, Leigh MW. Computed tomography reflects lower airway inflammation and tracks changes in early cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:943–950. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-343OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mott LS, Park J, Murray CP, Gangell CL, de Klerk NH, Robinson PJ, Robertson CF, Ranganathan SC, Sly PD, Stick SM AREST CF (Australian Respiratory Early Surveillance Team for Cystic Fibrosis) Progression of early structural lung disease in young children with cystic fibrosis assessed using CT. Thorax. 2012;67:509–516. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Augarten A, Paret G, Avneri I, Akons H, Aviram M, Bentur L, Blau H, Efrati O, Szeinberg A, Barak A, et al. Systemic inflammatory mediators and cystic fibrosis genotype. Clin Exp Med. 2004;4:99–102. doi: 10.1007/s10238-004-0044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lai HC, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Davis LA, FitzSimmon SC, Farrell PM. Nutritional status of patients with cystic fibrosis with meconium ileus: a comparison with patients without meconium ileus and diagnosed early through neonatal screening. Pediatrics. 2000;105:53–61. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stallings VA, Stark LJ, Robinson KA, Feranchak AP, Quinton H Clinical Practice Guidelines on Growth and Nutrition Subcommittee; Ad Hoc Working Group. Evidence-based practice recommendations for nutrition-related management of children and adults with cystic fibrosis and pancreatic insufficiency: results of a systematic review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:832–839. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dasenbrook EC, Merlo CA, Diener-West M, Lechtzin N, Boyle MP. Persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and rate of FEV1 decline in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:814–821. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-327OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Milla CE, Warwick WJ, Moran A. Trends in pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis correlate with the degree of glucose intolerance at baseline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:891–895. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9904075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Byrnes CA, Vidmar S, Cheney JL, Carlin JB, Armstrong DS, Cooper PJ, Grimwood K, Moodie M, Robertson CF, Rosenfeld M, et al. Australasian Cystic Fibrosis Bronchoalveolar Lavage (ACFBAL) Study Investigators. Prospective evaluation of respiratory exacerbations in children with cystic fibrosis from newborn screening to 5 years of age. Thorax. 2013;68:643–651. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Farrell PM, Lai HJ, Li Z, Kosorok MR, Laxova A, Green CG, Collins J, Hoffman G, Laessig R, Rock MJ, et al. Evidence on improved outcomes with early diagnosis of cystic fibrosis through neonatal screening: enough is enough! J Pediatr. 2005;147(3 Suppl):S30–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Farrell PM, Mischler EH, Engle MJ, Brown DJ, Lau SM. Fatty acid abnormalities in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Res. 1985;19:104–109. doi: 10.1203/00006450-198501000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanders DB, Farrell PM. Transformative mutation specific pharmacotherapy for cystic fibrosis. BMJ. 2012;344:e79. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eakin MN, Bilderback A, Boyle MP, Mogayzel PJ, Riekert KA. Longitudinal association between medication adherence and lung health in people with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2011;10:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]