Abstract

Early brain injury occurs in newborns with congenital heart disease (CHD) placing them at risk for impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes. Predictors for preoperative brain injury have not been well described in CHD newborns. This study aimed to analyze, retrospectively, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in a heterogeneous group of newborns who had CHD surgery during the first month of life using a detailed qualitative CHD MRI Injury Score, quantitative imaging assessments (regional apparent diffusion coefficient [ADC] values and brain volumes), and clinical characteristics. Seventy-three newborns that had CHD surgery at 8 ± 5 (mean ± standard deviation) days of life and preoperative brain MRI were included; 38 also had postoperative MRI. Thirty-four (34/73, 47%) had at least 1 type of preoperative brain injury, and 28/38 (74%) had postoperative brain injury. The 5-minute APGAR score was negatively associated with preoperative injury, but there was no difference between CHD types. Infants with intraparenchymal hemorrhage, deep gray matter injury, and/or watershed infarcts had the highest CHD MRI Injury Scores. ADC values and brain volumes were not different in infants with different CHD types, or in those with and without brain injury. In a mixed group of CHD newborns, brain injury was found preoperatively on MRI in almost 50%, and there were no significant baseline characteristic differences to predict this early brain injury, except 5-minute APGAR score. We conclude that all infants, regardless of CHD type, who require early surgery, should be evaluated with MRI as they are all at high risk for brain injury.

Keywords: brain injury, brain magnetic resonance imaging, congenital heart disease, congenital heart surgery, neonate, infant

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) affects 6-8 per 1000 live births with about 50% requiring operative intervention in the neonatal period [1, 2]. Infants with CHD are at a high risk for brain injury and impaired long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes [3]. Brain injury in these infants is complex and multi-factorial. Ischemic infarcts or white matter injury can be detected preoperatively in up to 40% on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).4 In addition, new injury is found in up to 30% postoperatively [2, 4-7]. Infants may also be born with evidence of prenatal brain injury with onset of microcephaly or cerebral atrophy in utero, perhaps as a sequela of altered cerebral blood flow [8-12]. The brain may also be structurally immature, making it more vulnerable [13].

It is important to understand early clinical factors that are associated with an increased risk of preoperative brain injury. Birth factors such as gestational age, growth parameters, APGAR scores, and initial arterial blood pH may be the earliest indicators following birth of risk for preoperative brain injury. Lower 5-minute APGAR scores appear to relate to preoperative brain injury on MRI [4, 13]. Neonates with CHD born at earlier gestational ages have an increased risk of impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes, so that the timing of birth may be an important factor [14]. RACHS-1 (Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery) categories were established as a method for assessing mortality risk associated with the surgical procedures, but these have not been related to already present brain injury [15]. The injury may be cumulative over time and some forms of CHD may be associated with higher rates of brain injury compared to others [16]. Therefore, a combination of early factors plus the underlying type of CHD and also surgery may correlate most with preoperative brain injury.

Unfortunately, the type and severity of brain injury is variable and it is not well known which newborns are at the highest risk and how each injury type affects long-term outcome. This has made practice plans involving routine brain injury screening difficult to implement [16]. Brain MRI is a useful tool to measure acute and chronic brain injury and has been routinely performed, clinically and for research, in infants undergoing CHD surgery. Preoperative MRI may identify early evidence of brain injury so that changes seen postoperatively can be differentiated from prior injury [5]. Preoperative brain injury however, does not necessarily increase the incidence of postoperative injury [7].

The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) is a measure of water diffusion in brain tissue and is measured on diffusion-weighted images (DWI) on brain MRI. It provides a measure of tissue complexity and rises during late fetal life with a steady decline during infancy [17-22]. A high ADC value is seen in chronic damaged white matter; however, a low ADC value indicates acute ischemia. In premature newborns, high white matter ADC values were associated with lower neurodevelopmental scores at age 2 years and were thought to be due to reduced white matter maturation [23, 24]. In a study of newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, lower regional ADC values were found in those with impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes [25]. This quantitative brain MRI measure has not been well studied in newborns with CHD.

Volumetric brain MRI is another quantitative measure which can add value to qualitative MRI. Some studies have evaluated brain volumes in certain forms of CHD, i.e. hypoplastic left heart syndrome, and found evidence for reduced volumes [9]. Brain volumes with different types of CHD have not been directly compared and values have not been compared to other clinical and MRI measures, although this may help identify those at the highest risk for impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes.

The objectives of this study were to: 1) evaluate the current prevalence, types, and severity of brain injury in infants with neonatal CHD surgery, 2) compare brain injury in infants with different types of CHD and develop a comprehensive CHD MRI Injury Score, 3) evaluate the usefulness of regional ADC values and brain volumes as quantitative measures of brain injury in CHD infants, and 4) understand clinical and surgical factors predictive of early brain injury. We hypothesized that predictors of preoperative brain injury can be identified and that infants with and without early brain injury will have differences in regional ADC values and brain volumes.

Material and Methods

Sample Size

We conducted a retrospective study of all infants with CHD who had surgery in the first 30 days of life (neonatal period) at Arkansas Children’s Hospital (ACH) Heart Center. The inclusion period was between June 1, 2009 and June 30, 2011. Seventy-three newborns with CHD surgery during the first month of life and preoperative brain MRI were identified; 38 also had postoperative brain MRI. Recorded baseline characteristics included demographics, birth history (i.e. birth weight, gestational age, birth head circumference, APGAR scores, and need for intubation), family history, age at admission to ACH, prenatal diagnosis of CHD, initial echocardiogram results, need for balloon atrial septostomy (BAS), type of CHD, and results of genetic tests. For each infant, details pertaining to the surgery included, age at surgery, surgical RACHs category, use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) including total bypass time and the degree of hypothermia. Each infant’s CHD was also classified into a large aggregate group [26]. This study received Institutional Review Board approval prior to initiation.

Brain Imaging

All infants underwent preoperative clinical brain MRI on a 1.5 Tesla scanner (General Electric or Phillips Medical) using a standardized MRI protocol that consisted of sagittal T1 weighted images, axial T2 weighted images, inversion recovery, fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR), diffusion weighted images (DWI), and susceptibility weighted images (SWI) or gradient echo (GRE) sequences. Postoperative brain MRIs were obtained once patients were clinically stable. The first postoperative MRI was included as the follow-up MRI, with most being obtained prior to discharge following the initial surgery. Fifty-two percent of infants had postoperative imaging. All MRIs were read by pediatric neuroradiologists.

Qualitative Analysis of Brain MRIs

The brain MRIs were reviewed again by board-certified pediatric neuroradiologists (CMG and RHR, with 27 and 14 years of experience, respectively) and were analyzed and scored according to published standards [4, 27]. The neuroradiologists were blinded to clinical condition, and only knew the gestational age at the time of the MRI and that the infant had CHD.

Brain MRI Score

A MRI score was developed by a pediatric neurologist (SBM) and pediatric neuroradiologists (CMG and RHR) in an objective manner. The score incorporated imaging abnormalities associated with impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes (i.e. white matter injury, gray matter injury, focal cerebral infarction, and watershed infarcts) and also additional findings that may be of added significance (i.e. changes in susceptibility weighted imaging). The method was based on brain injury scoring systems by Andropoulos, et al [28]. The score was developed by using a numerical value for each of 11 possible brain MRI findings which accounted for the severity of each type by the relative size or number of areas involved (Table 1). A value of “1” was thought to be consistent with severity across injury types based on the researchers clinical and radiology knowledge, experience, and other types of MRI scores. Higher relative weight was given to deep gray matter injury, watershed infarct, and stroke based on studies reporting the implication of injury at these locations [29-31]. The total score could be 100, although it would not be clinically possible to obtain without mortality. Each MRI was given a score after all images had been read.

Table 1.

Brain injury types and the CHD MRI Injury Score

| Brain Injury Typesa | CHD MRI Injury Scoreb | Total Score Possiblec |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Focal Infarct | Small | Moderate | Severe | 36 | ||

| ACA left | 1 | 3 | 6 | |||

| ACA Right | 1 | 3 | 6 | |||

| MCA left | 1 | 3 | 6 | |||

| MCA Right | 1 | 3 | 6 | |||

| PCA left | 1 | 3 | 6 | |||

| PCA Right | 1 | 3 | 6 | |||

|

| ||||||

| 2. Watershed Infarct | Right | Left | Both | 12 | ||

| Anterior Watershed | 3 | 3 | 6 | |||

| Posterior Watershed | 3 | 3 | 6 | |||

|

| ||||||

| 3. White Matter injury ± Cystic PVL | 12 | |||||

| White matter injury | None | Minimal | Moderate | Severe | Hemorrhagic | |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | Add 1 | ||

| Cystic PVL | Right | Left | ||||

| 3 | 3 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 4. Deep gray matter injury | None | Minimal | Moderate | Severe | 5 | |

| 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | |||

|

| ||||||

| 5. Susceptibility weighted image | Minimal | Moderate | Severe | 12 | ||

| Cortex | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Deep gray matter | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| White matter | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Cerebellum | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

|

| ||||||

| 6. Intraventricular hemorrhage | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade | 8 | |

| Left | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Right | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

|

| ||||||

| 7. Subdural hemorrhage | None | Present | 3 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||||

| Presence of mass effect | Yes | No | ||||

| 2 | 0 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 8. Subarachnoid hemorrhage | None | Present | 1 | |||

| 0 | 1 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| 9. Intraparenchymal | Small | Moderate | Severe | 6 | ||

| 1 | 3 | 6 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 10. Choroid Plexus hemorrhage | Right | Left | Bilateral | 2 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 11. Atrophy | None | Present | 3 | |||

| 0 | 3 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Total | 100 | |||||

ACA anterior cerebral artery, MCA middle cerebral artery, PCA posterior cerebral artery, PVL periventricular leukomalacia

There are 11 categories of brain injury, each representing a different type

Shown is the CHD MRI Injury Score for each type of brain injury based on the size of the injury, number of areas involved, or regions involved

The Total Score Possible column represents the CHD MRI Injury Score possible for each of the 11 brain injury types and adds up to a total of 100.

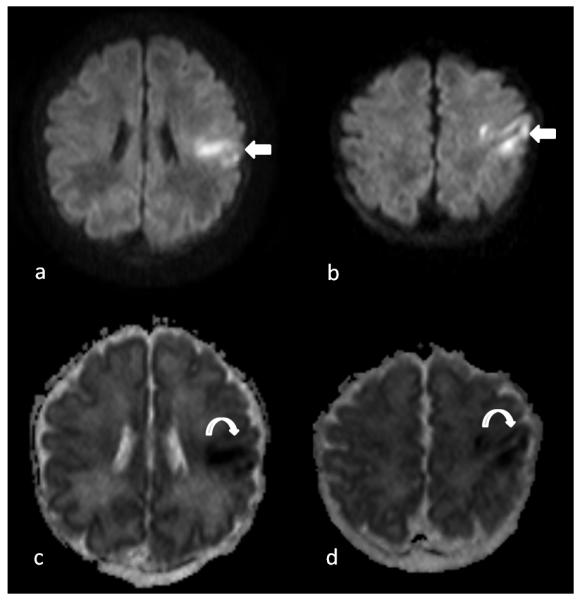

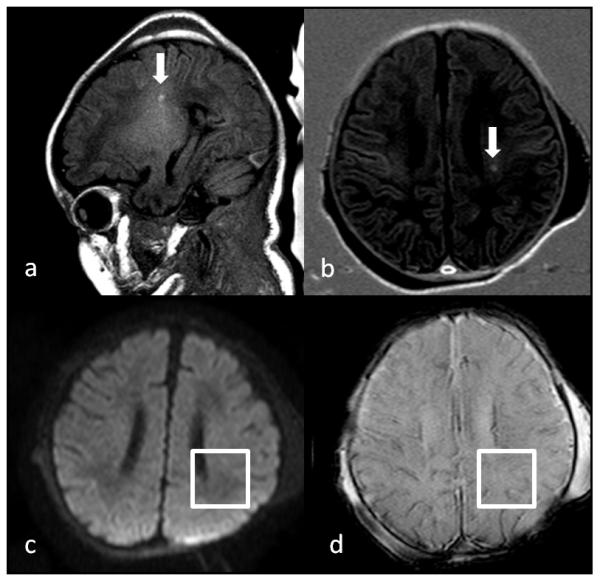

Brain Injury Type: Focal Infarct (Fig. 1)

Fig 1.

Preoperative brain MRI on a 1 day old infant with hypoplastic left heart syndrome showing a focal hyperintensity in the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) distribution on Axial B1000 images (arrows on image a and b) and hypointensity on apparent diffusion coefficient map (curved arrows on image c and d) indicating restricted diffusivity suggestive of acute infarction. By size it was considered small, so received a score of “1”. The infant also had a right posterior watershed infarction and bilateral grade 1 intraventricular hemorrhages, so received a total CHD MRI Injury score of “6”.

The vascular territory for each infarct was recorded. If the size of infarct was < 1/3rd of the size of the arterial territory, it was considered small, 1/3rd—2/3rds of the size of the arterial territory, it was considered moderate, and if it was > 2/3rds of the size of the arterial territory, it was considered severe. Watershed infarcts were examined separately as they do not follow an arterial territory. Bilateral injury received a higher score than unilateral involvement. Both acute infarcts and areas of encephalomalacia were included.

Brain Injury Type: White Matter Injury (Fig. 2)

Fig 2.

Preoperative brain MRI on a 12 day old infant with interrupted aortic arch, type A, and ventricular septal defect showing focal white matter injury (arrows) in the left periventricular white matter seen as focal hyperintensity on a T1 weighted image (a) and inversion recovery weighted image (b). There was no corresponding signal change on the diffusion weighted image (DWI) (c) and the susceptibility weighted image (SWI) (d). The white matter injury was graded as moderate, so received a score of “3”. The infant also had minimal SWI changes in the white matter and cortex, a subdural hemorrhage, and bilateral choroid plexus hemorrhages, so had a total CHD MRI Injury score of “8”.

White matter injury was defined as focal T1 hyperintensity without signal abnormality on DWI, GRE, or SWI. Minimal white matter injury was defined as representing ≤ 3 areas of T1 signal abnormality measuring < 2mm in size, moderate injury was documented if there were > 3 areas of T1 signal abnormality or the areas measured > 2 mm in size but were smaller than 5% of the involved hemisphere, and severe injury was present when > 5% of the hemisphere was involved. If the white matter injury was hemorrhagic, an additional score of 1 was added as this finding may represent a more severe injury type. Cystic periventricular leukomalacia (PVL), representing a chronic form of white matter injury was included separately and scored per hemisphere involved.

Brain Injury Type: Deep Gray Matter Injury

Deep gray matter injury was defined as minimal if there were ≤ 3 areas of T1 signal abnormality measuring < 2mm in size in the deep gray matter structures (thalamus, lentiform nucleus, and caudate nucleus), moderate if there were > 3 areas of T1 signal abnormality or the areas measured > 2 mm in size, and severe injury was considered present when > 5 areas of T1 signal abnormality were present or the majority of a gray matter structure had signal abnormality.

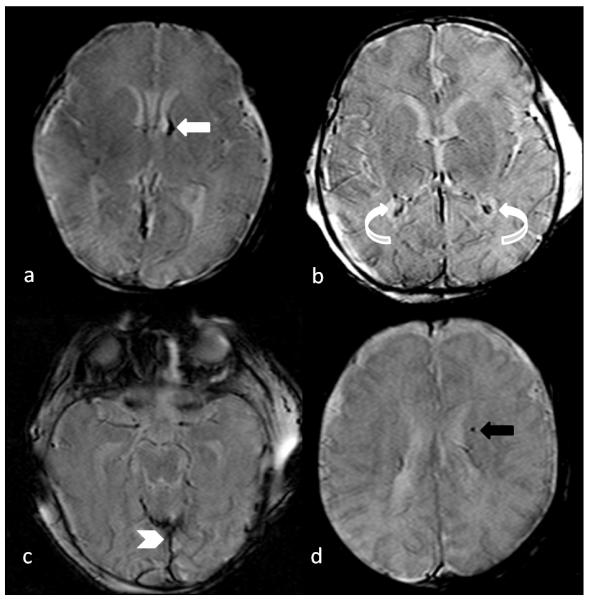

Brain Injury Type: Susceptibility Weighted Imaging (Fig. 3)

Fig 3.

Axial susceptibility weighted images (SWI) of different infants, demonstrating a grade 1 intraventricular hemorrhage (white arrow in image a) which received a score of “1”, bilateral choroid plexus hemorrhage (curved arrows in image b) which received a score of “2”, extra axial hemorrhage along the posterior falx cerebri and tentorium (chevron in image c) which received a score of “1”, and focal intraparenchymal hemorrhage in the left periventricular region (black arrow in image d) which received a score of “1”.

Low signal on SWI or GRE sequences were evaluated in the cortex, white matter, deep gray matter, and cerebellum to include all of the areas where these changes may be present. Minimal was considered if there were ≤ 3 involved areas, moderate if there were 4-6 areas involved, and severe if there were > 6 areas involved.

Brain Injury Type: Hemorrhages

The hemorrhage types identified included intraventricular hemorrhage, subdural hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, intraparenchymal hemorrhage, and/or choroid plexus hemorrhage. Intraventricular hemorrhages were defined and graded based on the well-established definitions used in practice [32]. Each grade was used as the score. A subdural hemorrhage was given additional points if there was the presence of mass effect, as this clinically represents a more significant hemorrhage. A small intraparenchymal hemorrhage was when there were ≤ 3 areas of hemorrhage all < 1 cm in size, moderate if there were 3-5 areas of hemorrhage, or at least 1 of the hemorrhages was > 1cm in size, but all are ≤ 3cm in size, and severe (large) if there were > 5 areas of hemorrhage, or at least 1 of the areas was > 3 cm in size. Hemorrhage in the choroid plexus was scored based on the side(s) involved.

Brain Injury Type: Atrophy

Atrophy was defined as enlargement of the extra-axial fluid spaces, dilatation of the lateral ventricles, and cortical sulcal prominence, and was only marked when the neuroradiologists thought that the finding was present by consensus.

ADC Measurement

ADC values were calculated on the clinically acquired brain MRIs on the PACS workstation using a region of interest (ROI) method by a MRI physicist [33]. The mean ADC values (10−6 mm2/s) in the anterior and posterior white matter, the basal ganglia, and in the thalamus over the left and right brain were measured by drawing ROIs using the polygonal function on an axial ADC image at the level of the maximal total brain area intersecting the lateral ventricles. Repeated measurements were performed at another time for some MRIs to ensure reproducibility.

Volumetric MRI Analysis

Using the clinical MRI scans, brain measurements were performed on serial axial T1 images using the standard clinical scanning protocol. Quantification of cross sectional areas on individual slices was performed from axial T1 images that were input into a personal computer-based system as converted digital images. Images were digitized using a DT 2858 Frame Grabber (Data Translation, Wellesley, MA). Tracings and area calculations were made from the digital images of the total intracranial volume, whole brain, corpus callosum, and ventricular volume. The anatomic boundary of the corpus callosum for the tracings was previously described [34-36]. Commercial image analysis software (Image-Pro Plus; Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD) was used. Data from individual slices were compiled using a customized algorithm (GBS) that incorporates slice thickness, inter-gap size, number of slices, and external calibration standardization to render a final volumetric estimate for each structure/space measured. Head circumference was measured by tracing the outer border of the scalp at the level of the maximum occipital protuberance using an axial T1 MRI slice. Volumetric estimates using this technique are highly reproducible [34].

Statistical Analysis

Neonatal demographics, clinical, and surgical features as well as brain imaging findings were summarized as mean ± standard deviation as well as median (25th, 75th quartiles) for continuous data and frequency and percentage for categorical data. The prevalence of brain injury was defined as any finding of brain injury compared to no finding of brain injury. To estimate any association between demographic, clinical, and surgical features with brain injury prevalence, univariable analysis used the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for continuous and ordinal variables, and Chi-square test of independence for categorical variables.

Multivariate analysis was also completed using regression models. Logistic regression was used to estimate for any association between demographic and clinical data while adjusting for known confounders including APGAR score and age, while Poisson regression was used to estimate any association between demographic and clinical data with the total number of brain injuries. To estimate any association between the constructed brain injury severity scale with clinical and demographic data, beta regression was utilized. Beta regression is an extension of generalized linear model theory that has been shown to be useful in modeling percentages [37], including analyzing ischemic stroke lesion volumes [38]. Considering the brain injury severity scale was constructed with an absolute minimum (i.e. no injury) and maximum (i.e. complete injury), the raw score was converted into a percentage for modeling. Finally, change in pre- and postoperative ADC values were estimated using linear regression adjusting for age, disease group, and prevalence of brain injury.

Study data were stored securely using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) and statistical analysis was completed using R 2.15.1 (Vienna, Austria) and Stata 12.1 (College Station, TX).

Results

Seventy-three infants with neonatal CHD surgery at 8 ± 5 (mean ± standard deviation) days of life and preoperative brain MRI at 8 ± 7 days of life were identified. Differences between infants with and without preoperative brain injury were not statistically significant for all demographic, early clinical, and surgery characteristics (Table 2). Mortality was not different in those with brain injury compared to those without (p = 0.6). The presence of preoperative brain injury was also not associated with the type of CHD either by specific type or using a large group classification scheme (Table 3) [26].

Table 2.

Demographics, early clinical, and surgery characteristics separated by the presence or absence of preoperative brain injury

| No Brain Injury*a | Brain Injury*b | p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 39 | 34 | ||

| Gender | 0.489 | |||

| Male | 26 (37%) | 20 (59%) | ||

| Female | 13 (33%) | 14 (41%) | ||

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 23 (59%) | 21 (70%) | 0.633 | |

| African-American | 8 (21%) | 3 (10%) | ||

| Hispanic | 6 (15%) | 3 (10%) | ||

| Asian | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | ||

| Other | 1 (3%) | 2 (7%) | ||

| Prenatal diagnosis of CHD | 0.445 | |||

| Yes | 10 (28%) | 12 (36%) | ||

| No | 26 (72%) | 21 (64%) | ||

| Mode of delivery | 0.113 | |||

| Caesarean Section | 20 (54%) | 12 (35%) | ||

| Vaginal delivery | 17 (46%) | 22 (65%) | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 27 [21, 32] | 24 [21, 28] | 0.385* | |

| Birth gestational age (weeks) | 39 [38, 39] | 38 [37, 39] | 0.163* | |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3000 [2695, 3374] | 3085 [2630, 3295] | 0.946* | |

| Age at admission (days) | 0 [0, 2] | 0 [0, 2] | 0.924* | |

| APGAR Score 1 minute | 8 [7, 8] | 8 [6, 8] | 0.569* | |

| APGAR Score 5 minutes | 9 [8, 9] | 8 [8, 9] | 0.251* | |

| Intubation at delivery | 0.920 | |||

| Yes | 8 (22%) | 7 (21%) | ||

| No | 28 (78%) | 26 (79%) | ||

| BAS | 0.975 | |||

| Yes | 8 (23%) | 7 (23%) | ||

| No | 27 (77%) | 24 (77%) | ||

| Abnormal genetic testing | 0.461 | |||

| Yes | 7 (18%) | 4 (12%) | ||

| No | 32 (82%) | 30 (88%) | ||

| Age of preoperative MRI (days) | 4 [2, 10] | 8 [4, 13] | 0.118* | |

| Age at surgery (days) | 7 [4, 10] | 8 [4, 12] | 0.653* | |

| RACHS-1 Category | 0.708 | |||

| RACHS 1-2 | 4 (11%) | 2 (6%) | ||

| RACHS 3-4 | 27 (71%) | 24 (71%) | ||

| RACHS 5-6 | 7 (18%) | 8 (24%) | ||

| CPB at Surgery | 0.999 | |||

| Yes | 33 (85%) | 28 (85%) | ||

| No | 6 (15%) | 5 (15%) | ||

| CPB time (minutes) | 161 [110, 191] | 141 [113, 168] | 0.271* | |

| AoX time (minutes) | 66 [31, 100] | 56 [28, 83] | 0.778* | |

| Minimum Surgery Temperature (C°) | 23 [18, 28] | 24 [20, 28] | 0.484* | |

| Mortality | 0.556 | |||

| Yes | 7 (18%) | 8 (24%) | ||

| No | 32 (82%) | 26 (76%) | ||

| Length of hospitalization (days) | 35 [29, 52] | 33 [20, 78] | 0.918 |

Median (25th, 75th percentile) and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney reported. Otherwise, N (%) and Chi-square reported.

CHD congenital heart disease, BAS balloon atrial septostomy, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, RACHS-1 Risk Adjustment Congenital Heart Surgery, CPB cardiopulmonary bypass, AoX aortic cross clamp time

No Brain Injury was defined as a CHD MRI Injury Score of “0”

Brain Injury was defined as a CHD MRI Injury Score of “≥ 1”

Table 3.

CHD types separated by the presence or absence of preoperative brain injury

| Main Diagnosis Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No Brain Injury*a | Brain Injury*b | p value* | |

| Transposition of the great arteries (dTGA) | 7 (18%) | 7 (21%) | 0.775 |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) | 9 (23%) | 9 (26%) | 0.737 |

| Coarctation of Aorta (COA) | 8 (21%) | 7 (21%) | 1.000 |

| Pulmonary Atresia | 5 (13%) | 2 (6%) | 0.315 |

| Tetrology of Fallot (TOF) | 4 (10%) | 1 (3%) | 0.217 |

| Large Group Diagnosis [26] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No Brain Injury*a | Brain Injury*b | p value* | |

| N | 39 | 34 | |

| Large Group Category | 0.510 | ||

| Conotruncal | 16 (41%) | 12 (35%) | |

| AVSD | 1 (3%) | 2 (6%) | |

| APVR | 1 (3%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Heterotaxy | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Complex | 1 (3%) | 3 (9%) | |

| LVOTO | 14 (36%) | 14 (41%) | |

| Septal | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | |

| RVOTO | 5 (13%) | 1 (3%) |

N (%) and Chi-square reported.

No Brain Injury was defined as a CHD MRI Injury Score of “0”

Brain Injury was defined as a CHD MRI Injury Score of “≥ 1”

AVSD atrioventricular septal defect, APVR anomalous pulmonary venous return, LVOTO left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, RVOTO right ventricular outflow tract obstruction

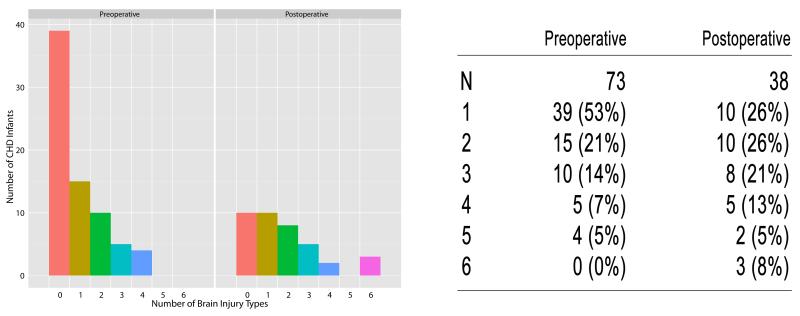

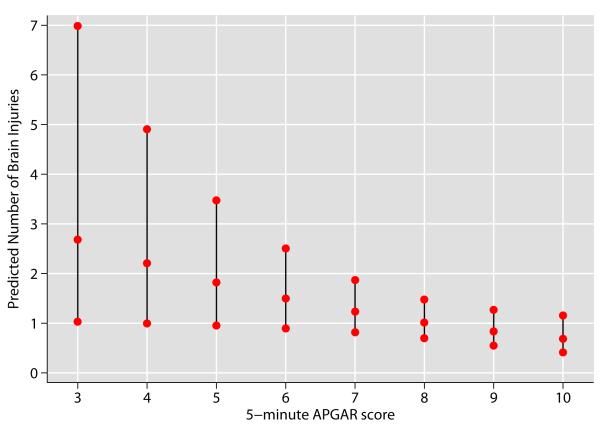

The total number of brain lesions detected on preoperative MRI was, 1) 34/73 (47%) with at least one type of preoperative brain injury, and 2) 26% having 2 to 4 injury types (Fig. 4). The 5-minute APGAR score was negatively associated with brain injury using Poisson regression (Fig. 5); for every unit increase in APGAR score, the average number brain lesions expected decreased by 0.17 (p = 0.025, 95% CI: (−0.31, −0.02). For example, the predicted number of brain lesions detected for an infant with a 5-minute APGAR score of 3 was 2.2, while a score of 8 was associated with 0.94 predicted brain lesions. Moreover, the predictive capacity of a score > 8 provided few false positives (sensitivity 90.3%, 95% CI: 80.1%, 96.4%) while identifying more false negatives (specificity 12.2%, 95% CI: 4.6%, 24.8%).

Fig 4.

Brain Injury Count by Surgery Time Point

Bar chart of the number of brain injury types seen in CHD infants preoperatively and postoperatively. Each bar represents the number of CHD infants (N) with that number of brain injury types. Zero represents no brain injury, while 6 represents 6 types of brain injury (of 11 possible types).

Fig 5.

Prediction of Brain Injury with APGAR Score

The middle point of the vertical line at each 5-minute APGAR Score represents the mean estimated number of brain injury types with that score and the outer points are the limits of the 95% confidence interval. An APGAR score of ≤ 7 was predictive of ≥ 1 type of brain injury.

Thirty-eight infants (52.1%) also had postoperative brain MRI at 46 ± 41 days of life. Having a postoperative MRI was associated with increased median birth weight (3200 vs. 2985 grams, p = 0.028), younger median age at surgery (6 vs. 10 days, p = 0.024), and CPB at surgery (95% vs. 74%, p = 0.013). Only 10/38 (26%) had no evidence for brain injury postoperatively (Fig. 4). Overall, the number of brain injury types seen postoperatively was higher than that seen preoperatively (max 7 vs. 4, p < 0.001). A Poisson mixed effects regression adjusted for repeat MRIs, CHD diagnosis, and the differences between those with and without postoperative MRIs.

Excluding all hemorrhages, preoperatively 26% (n=19) and postoperatively 61% (n=23) had other brain injury types. For the 38 with both pre and postoperative MRIs, 57% of those without preoperative injury had postoperative injury, while in those with preoperative injury, 33% experienced an increase in injury on postoperative MRI. Developmental brain malformation was rare, as this was only seen in 2 infants. Persistent cavum septum pellucidum however, was present in 39 of 73 (53%) infants preoperatively, perhaps indicating brain immaturity (although may be seen in normal term newborns).

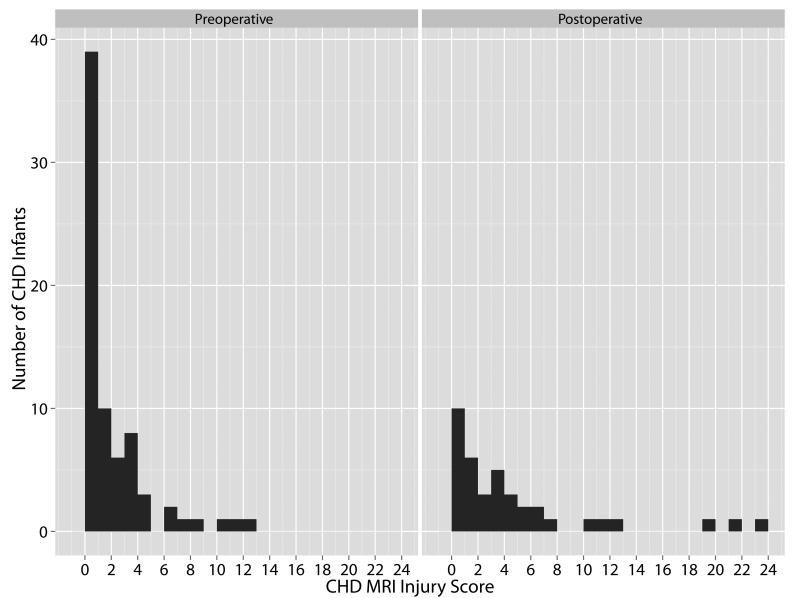

Using the proposed CHD MRI Injury Score, infants preoperatively had a score of 1.6 ± 2.7 compared to 4.3 ± 5.9, postoperatively (Fig. 6). The score was 5 ± 5 versus 4 ± 4, in the infants with preoperative versus postoperative MRI scores of 1 or more, indicating at least some form of brain abnormality. Evaluating preoperative and postoperative MRIs collectively (n = 111), the presence of intraparenchymal hemorrhage, watershed infarction, gray matter injury, and/or atrophy were associated with mean injury scores of >10, the highest brain injury severities (Table 4). MRIs with a subdural hemorrhage had the lowest mean score. To predict brain injury over time, a unit increase in the proposed MRI score was positively associated with an increase in the number of brain injury types observed (p < 0.001).

Fig 6.

CHD MRI Injury Score by Surgery Time Point

Bar chart of CHD MRI Injury Score for preoperative (n = 73) and postoperative (n = 38) brain MRIs. Each bar represents the number of infants with that CHD MRI Injury Score.

Table 4.

CHD MRI Injury Score by brain injury type (n=111, preoperative and postoperative brain MRIs reported together)

| Brain Injury Type | Nc | CHD MRI Injury Score* |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Focal Infarct | |||

| Yes a | 11 | 6 [3, 12]d | |

| No b | 100 | 1 [0, 3] | |

|

| |||

| 2. Watershed Infarct | |||

| Yes | 3 | 11 [9, 17] | |

| No | 108 | 1 [0, 3] | |

|

| |||

| 3. White Matter Injury | |||

| Yes | 19 | 4 [3, 11] | |

| No | 92 | 0 [0, 2] | |

|

| |||

| 4. Deep Gray Matter Injury | |||

| Yes | 8 | 10 [5, 20] | |

| No | 103 | 1 [0, 3] | |

|

| |||

| 5. Susceptibility Weighted Image Changes | |||

| Yes | 26 | 5 [3, 11] | |

| No | 85 | 0 [0, 1] | |

|

| |||

| 6. Intraventricular Hemorrhage | |||

| Yes | 7 | 3 [3, 6] | |

| No | 103 | 1 [0, 3] | |

| Missi | 1 | 4 [4, 4] | |

|

| |||

| 7. Subdural Hemorrhage | |||

| Yes | 30 | 2 [1, 4] | |

| No | 81 | 0 [0, 3] | |

|

| |||

| 8. Subarachnoid Hemorrhage | |||

| Yes | 4 | 4 [2, 6] | |

| No | 107 | 1 [0, 3] | |

|

| |||

| 9. Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage | |||

| Yes | 5 | 19 [11, 21] | |

| No | 106 | 1 [0, 3] | |

|

| |||

| 10. Choroid Plexus Hemorrhage | |||

| Yes | 9 | 3 [3, 7] | |

| No | 102 | 1 [0, 3] | |

|

| |||

| 11. Atrophy | |||

| Yes | 11 | 10 [5, 16] | |

| No | 100 | 1 [0, 3] | |

|

| |||

| Total | 111 | 1 [0, 3] | |

Median (25th, 75th percentile) CHD MRI Injury Score reported

Yes indicates the presence of that type of brain injury on preoperative or postoperative brain MRI

No indicates the absence of that type of brain injury on preoperative or postoperative brain MRI

N is the total number of brain MRIs (preoperative [n=73] and postoperative [n=38]) that have the presence or absence of each brain injury type.

For example, the median CHD MRI Injury Score for a brain MRI which contained a Focal Infarct was a score of 6 compared to 1, the median CHD MRI Injury Score for a MRI which did not contain a focal infarct

The preoperative ADC values found in the anterior white matter (1500 + 200 10−6 mm2/s), posterior white matter (1409 + 209 10−6 mm2/s), thalamus (966 + 133 10−6 mm2/s), and basal ganglia (1054 ± 145 10−6 mm2/s), were not different between infants with different forms of CHD and between those with and without brain injury. The presence of dextrotransposition of the great arteries (dTGA), hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), other CHD types, brain injury, and postconceptual age at MRI was not associated with change from the preoperative to the postoperative MRI using a multivariate regression model.

Preoperatively, the head circumference was 36 ± 3 cm, total intracranial volume 459 ± 110 cm3, whole brain volume 379 ± 68 cm3, corpus callosum volume 1.1 ± 0.7 cm3, and axial ventricular volume 33 ± 2 cm3. Head circumference and volumes were not different between those with and without brain injury, using the Wilcoxon test (p > 0.05). Similarly, there was no difference in head circumference or brain volumes postoperatively for those with and without brain injury (p > 0.05). Using a multivariate regression model incorporating change in brain volume from the preoperative to the postoperative MRI, the postnatal age at MRI (gestational age + day of life at MRI), the presence of dTGA, HLHS, or other CHD type, and the presence of preoperative injury, there was no difference between groups (p > 0.05).

Discussion

This investigation represents one of the largest studies of preoperative and postoperative brain MRIs in a heterogeneous group of infants with neonatal CHD surgery. We sought to evaluate a number of clinical factors along with qualitative brain MRI scoring and quantitative imaging assessments in order to predict infants who are at the highest risk for brain injury, especially preoperatively. The results of this study did not support the proffered hypothesis. Only APGAR score was found to be a predictor for preoperative brain injury and there were no differences in preoperative or postoperative quantitative measurements on MRI in infants with and without brain injury and in infants with different types of CHD (i.e. HLHS, dTGA, and others). The results showed that all infants who require CHD surgery in the first month of life, regardless of CHD type, are at high risk for preoperative brain injury, yielding an even more important conclusion.

About 50% of infants in our study had evidence for brain injury preoperatively, which is comparable to other published reports. In most, brain injury severity was relatively mild and when hemorrhages (that may be incidental following birth) were excluded, only about 25% had evidence for preoperative brain injury. Some studies report infants as presenting with or without brain injury, and do not take into account the actual injury severity [4, 39]. Brain injuries in the form of a single small area of white matter injury may have relatively low long-term clinical significance compared to bilateral areas of substantial white matter changes, and such small unilateral lesions may eventually resolve over time [6]. Similarly, a small subdural hemorrhage can frequently be seen in a newborn due to birth forces following delivery and does not represent a form of significant brain injury.

It is not well known how brain injury severity affects long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with CHD. Most newborn brain injury scores focus on diffuse type injury patterns such as are seen in premature newborns and those with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy [27]. Few studies of brain injury in CHD newborns use a brain injury score [28]. Developing an appropriate brain injury scoring system for newborns with CHD is complicated due to the significant variability and severity of brain abnormalities seen in this population. The proposed scoring system represents an attempt to quantitate several types of brain abnormalities and is similar to a score by Andropoulos, et al., except that it does not incorporate MR Spectroscopy, as this was not obtained for most of our infants [28]. The presented method provides a means of classifying infants by brain injury severity.

The CHD MRI Injury Score demonstrated that infants with brain injury types most known to be associated with impaired long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes had higher overall scores, compared to infants with less concerning brain injury types. For example, the mean total injury score for the 30 MRIs that contained a subdural hemorrhage was considerably lower (median = 2) than the mean injury score for MRIs which included focal or watershed infarct (median = 6), white matter injury (median = 4), gray matter injury (median = 10), intraparenchymal hemorrhage (median = 19), and/or atrophy (median = 10), which represent more severe forms of brain injury (Table 4). This finding probably results from the score’s design in that some injury types have higher relative weights as well as the presence of multiple injuries with more heavily weighed injury types. Injury scores of at least 7 would be concerning for neurodevelopmental effects, making this scoring system beneficial in predicting impaired neurologic outcomes.

Interestingly, few predictors for potentially clinically significant brain injury were found. As others have shown, it appears that the 5-minute APGAR score may be one of the earliest perinatal indications for early brain injury. Our study showed that a 5-minute APGAR score of ≤ 7 was associated with 1 or more types of brain injury (Fig. 5). This is not surprising as the APGAR score is a directly assigned measure at birth for how the baby is transitioning to extra-uterine life. The APGAR score was found to be a biomarker for impaired outcome in newborns with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, and was established as part of the criteria for therapeutic hypothermia [40]. In hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, the APGAR score is typically considerably lower than for brain injured newborns with CHD. The slightly low number in newborns with CHD may indicate abnormal response at birth, perhaps “mild” hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Unlike other published reports, however, we did not find a correlation of gestational age with brain injury [14]. It may be that our study did not include a sufficiently wide range of gestational ages to observe this effect, however, our eligibility criteria was not based on gestational age. The preterm brain is especially vulnerable to injury [41]. Newborns with CHD may also have relative brain immaturity [28]. It may therefore, be the combination of gestational age and a newborns level of brain maturation that influences risk of early brain injury.

The study did not find a correlation between preoperative ADC values and the presence of early brain injury or a difference between infants with different forms of CHD. There was also no difference between infants with and without brain injury with respect to change in ADC values from the preoperative to the postoperative MRI. The postoperative brain MRI occurred at a mean of 38 days after the preoperative MRI, a time period long enough to show that ADC values declined in all measured regions, regardless of brain injury status. There was also no difference in this change between infants with different types of CHD, indicating that brain maturation perhaps occurs at a similar rate in all infants who require early surgery, and that those previously thought of as high risk groups (i.e. those with HLHS or dTGA) are not different from others who require early surgery. Without being able to compare the rate of the decline in ADC values during this time to a normal control population, the data cannot be used to determine whether this maturation is normal, only that it is not different between studied groups. Further studies of ADC values over time in infants with CHD are needed.

Likewise this study found comparable brain volumes among all infants, both preoperatively and postoperatively. Brain volume and brain growth was not different in infants with HLHS (n = 18) or TGA (n = 14) compared to other infants. This differs from reports of brain volume differences in these CHD types [9, 12]. Differences may not have been found because only 44% of our study infants had one of these forms of CHD or it may also be that brain volumes are similarly reduced in all infants who require early surgery. Volumes were only compared between infants based on CHD type and brain injury status, adjusting for age at MRI, and not to healthy control infants, so that the data cannot determine if brain volumes are normal among the studied cohort. It was reassuring, however, to find that brain growth was not altered in those with preoperative brain injury compared to the others at the time of the postoperative imaging. Alternatively, atrophy and reduced velocity of overall brain growth may require a longer interval between MRI studies to be detected. Further studies evaluating long-term brain growth in these infants would be beneficial.

This study is limited by its retrospective design. Brain MRIs were clinically acquired preoperatively on most infants who required early CHD surgery, but only about 50% had postoperative MRI. There were baseline differences between the infants who had postoperative imaging and those who did not, which may have affected results. More infants who only had preoperative MRI died (29% vs. 13%), but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.103). There was variability in the timing of postoperative brain MRIs between infants which could have impacted the injury score. MRIs within 1 week of surgery may show evidence of acute ischemic injury on the diffusion weighted sequence, but if performed later, only evidence for injury on other MRI sequences may be appreciated with pseudo normalization of signal changes on diffusion weighted sequences. Standardized timing for postoperative MRIs would be best, however given the range of postoperative stability in these infants, this would be hard to implement. Additionally, since the CHD MRI Injury score has not been validated this will need to be done in future studies.

Clinical practice at the time of the infants’ admission did not include standardized neurodevelopmental follow-up. At the time of this study, only 3 of the 58 survivors returned for clinically indicated neurodevelopmental assessments. There is likely a large number who would benefit from early neurodevelopmental testing, and will present at an older age when learning difficulties or other neurologic impairments arise. Since the time of our study, the American Heart Association’s Scientific Statement from July 2012 recommended that all infants with CHD should be followed for neurodevelopmental impairments as they are at high risk for such disabilities [3]. Without early developmental testing, this study is unable to correlate the MRI findings, CHD MRI Injury Score, and neurodevelopmental outcome.

Brain injury occurs at a high rate in all newborns with CHD who require neonatal surgery. The entire group can be considered at elevated risk, so that in order to improve long-term neurologic outcomes, they must all be considered. APGAR score at 5-minutes was the only predictor for early brain injury, with no other helpful clinical characteristics identified. According to the American Heart Association’s Scientific Statement from July 2012, “neonates or infants requiring open heart surgery” should be considered at high risk for impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes [3]. Our study supports the idea that the mechanism for impaired neurologic outcomes may be early, often preoperative, brain injury, found to be prevalent in a mixed group of CHD infants. Additionally, brain injury was also found postoperatively, thereby compounding this risk. Therefore, to reduce the neurologic burden for these infants, future interventions need to be aimed at protecting the brain in all CHD newborns from the perinatal period through infancy. New studies evaluating brain MRI findings, CHD Brain Injury scores, and quantitative neuroimaging techniques with standardized neurodevelopmental assessments are needed to define how brain imaging can best be used as a marker for neurologic outcome in infants with CHD.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Arkansas Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Arkansas Biosciences Institute, Children’s University Medical Group, and the Center for Translational Neuroscience award from The National Institutes of Health (P20 GM103425). REDCap receives institutional support from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Translational Research Institute (NCATS/NIH 1 UL1 RR029884). The authors appreciate the work of Crystal Bland who performed brain volume measurements, Nupur Chowdhury, MS, CRRP, who collected study data, and Sadia Malik, MD [26] who assisted with large group classification of infants with more complex CHD types.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Samanek M. Congenital heart malformations: prevalence, severity, survival, and quality of life. Cardiol Young. 2000;10:179–185. doi: 10.1017/s1047951100009082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller SP, McQuillen PS. Neurology of congenital heart disease: insight from brain imaging. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F435–F437. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.108845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, Peacock G, Gerdes M, Gaynor JW, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126:1143–1172. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318265ee8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McQuillen PS, Hamrick SEG, Perez MJ, Barkovich AJ, Glidden DV, Karl TR, et al. Balloon atrial septostomy is associated with preoperative stroke in neonates with transposition of the great arteries. Circulation. 2006;113:280–285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.566752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherlock RL, McQuillen PS, Miller SP. Preventing brain injury in newborns with congenital heart disease: brain imaging and innovative trial designs. Stroke. 2009;40:327–332. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.522664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahle WT, Tavani F, Zimmerman RA, Nicolson SC, Galli KK, Gaynor JW, et al. An MRI study of neurological injury before and after congenital heart surgery. Circulation. 2002;106:I109–I114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Block AJ, McQuillen PS, Chau V, Glass H, Poskitt KJ, Barkovich AJ, et al. Clinically silent preoperative brain injuries do not worsen with surgery in neonates with congenital heart disease. J Tharac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berg C, Gembruch O, Gembruch U, Geipel A. Doppler indices of the middle cerebral artery in fetuses with cardiac defects theoretically associated with impaired cerebral oxygen delivery in utero: is there a brain-sparing effect? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2009;34:666–672. doi: 10.1002/uog.7474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hinton RB, Andelfinger G, Sekar P, Hinton AC, Gendron RL, Michelfelder EC, et al. Prenatal head growth and white matter injury in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2008;64:364–369. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181827bf4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaltman JR, Di H, Tian Z, Rychik J. Impact of congenital heart disease on cerebrovascular blood flow dynamics in the fetus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;25:32–36. doi: 10.1002/uog.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Licht DJ, Wang J, Silvestre DW, Nicolson SC, Montenegro LM, Wernovsky G, et al. Preoperative cerebral blood flow is diminished in neonates with severe congenital heart defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:841–849. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Limperopoulos C, Tworetzky W, McElhinney DB, Newburger JW, Brown DW, Robertson RL, Jr., et al. Brain volume and metabolism in fetuses with congenital heart disease: evaluation with quantitative magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. Circulation. 2010;121:26–33. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.865568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Licht DJ, Shera DM, Clancy RR, Wernovsky G, Montenegro LM, Nicolson SC, et al. Brain maturation is delayed in infants with complex congenital heart defects. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:529–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goff DA, Luan X, Gerdes M, Bernbaum J, D’Agostino JA, Rychik J, et al. Younger gestational age is associated with worse neurodevelopmental outcomes after cardiac surgery in infancy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkins KJ. Risk adjustment for congenital heart surgery: the RACHS-1 method. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2004;7:180–184. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Owen M, Shevell M, Majnemer A, Limperopoulos C. Abnormal brain structure and function in newborns with complex congenital heart defects before open heart surgery: a review of the evidence. J Child Neurol. 2011;26:743–755. doi: 10.1177/0883073811402073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cannie M, De KF, Meersschaert J, Jani J, Lewi L, Deprest J, et al. A diffusion-weighted template for gestational age-related apparent diffusion coefficient values in the developing fetal brain. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:318–324. doi: 10.1002/uog.4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hermoye L, Saint-Martin C, Cosnard G, Lee SK, Kim J, Nassogne MC, et al. Pediatric diffusion tensor imaging: normal database and observation of the white matter maturation in early childhood. Neuroimage. 2006;29:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huppi PS, Dubois J. Diffusion tensor imaging of brain development. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim DH, Chung S, Vigneron DB, Barkovich AJ, Glenn OA. Diffusion-weighted imaging of the fetal brain in vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:216–220. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller SP, Vigneron DB, Henry RG, Bohland MA, Ceppi-Cozzio C, Hoffman C, et al. Serial quantitative diffusion tensor MRI of the premature brain: development in newborns with and without injury. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:621–632. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider MM, Berman JI, Baumer FM, Glass HC, Jeng S, Jeremy RJ, et al. Normative apparent diffusion coefficient values in the developing fetal brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1799–1803. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnan ML, Dyet LE, Boardman JP, Kapellou O, Allsop JM, Cowan F, et al. Relationship between white matter apparent diffusion coefficients in preterm infants at term-equivalent age and developmental outcome at 2 years. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e604–e609. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramenghi LA, Rutherford M, Fumagalli M, Bassi L, Messner H, Counsell S, et al. Neonatal neuroimaging: going beyond the pictures. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:S75–S77. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liauw L, van Wezel-Meijler G, Veen S, van Buchem MA, van der Grond J. Do apparent diffusion coefficient measurements predict outcome in children with neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:264–270. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Botto LD, Lin AE, Riehle-Colarusso T, Malik S, Correa A. Seeking causes: Classifying and evaluating congenital heart defects in etiologic studies. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79:714–727. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller SP, Cozzio CC, Goldstein RB, Ferriero DM, Partridge JC, Vigneron DB, et al. Comparing the diagnosis of white matter injury in premature newborns with serial MR imaging and transfontanel ultrasonography findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1661–1669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andropoulos DB, Hunter JV, Nelson DP, Stayer SA, Stark AR, McKenzie ED, et al. Brain immaturity is associated with brain injury before and after neonatal cardiac surgery with high-flow bypass and cerebral oxygenation monitoring. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:543–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rutherford M, Pennock J, Schwieso J, Cowan F, Dubowitz L. Hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy: early and late magnetic resonance imaging findings in relation to outcome. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1996;75:F145–F151. doi: 10.1136/fn.75.3.f145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barkovich AJ, Hajnal BL, Vigneron D, Sola A, Partridge JC, Allen F, et al. Prediction of neuromotor outcome in perinatal asphyxia: evaluation of MR scoring systems. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:143–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller SP, Ramaswamy V, Michelson D, Barkovich AJ, Holshouser B, Wycliffe N, et al. Patterns of brain injury in term neonatal encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2005;146:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papile LA, Burstein J, Burstein R, Koffler H. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J Pediatr. 1978;92:529–534. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Kady RM, Choudhary AK, Tappouni R. Accuracy of apparent diffusion coefficient value measurement on PACS workstation: A comparative analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W280–W284. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaefer GB, Thompson JN, Jr., Bodensteiner JB, Hamza M, Tucker RR, Marks W, et al. Quantitative morphometric analysis of brain growth using magnetic resonance imaging. J Child Neurol. 1990;5:127–130. doi: 10.1177/088307389000500211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaefer GB, Bodensteiner JB, Thompson JN, Jr., Kimberling WJ, Craft JM. Volumetric neuroimaging in Usher syndrome: evidence of global involvement. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheth RD, Schaefer GB, Keller GM, Hobbs GR, Ortiz O, Bodensteiner JB. Size of the corpus callosum in cerebral palsy. J Neuroimaging. 1996;6:180–183. doi: 10.1111/jon199663180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smithson M, Verkuilen J. A better lemon squeezer? Maximum-likelihood regression with beta-distributed dependent variables. Psychol Methods. 2006;11:54–71. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swearingen CJ, Tilley BC, Adams RJ, Rumboldt Z, Nicholas JS, Bandyopadhyay D. Application of Beta Regression to analyze ischemic stroke volume in NINDS rt-PA clinical trials. Neuroepi. 2011;37:73–82. doi: 10.1159/000330375. at al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller SP, McQuillen PS, Vigneron DB, Glidden DV, Barkovich AJ, Ferriero DM, et al. Preoperative brain injury in newborns with transposition of the great arteries. Ann Thor Surg. 2004;77:1698–1706. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gluckman P, Wyatt J, Azzopardi D, Ballard R, Edwards A, Ferriero DM, et al. Selective head cooling with mild sytemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomized trial. Lancet. 2005;365:663–670. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17946-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Back SA, Luo NL, Borenstein NS, Levine JM, Volpe JJ, Kinney HC. Late oligodendrocyte progenitors coincide with the developmental window of vulnerability for human perinatal white matter injury. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1302–1312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01302.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]