Abstract

Purpose.

Bisretinoids form in photoreceptor cells and accumulate in retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) as lipofuscin. To examine the role of these fluorophores as mediators of retinal light damage, we studied the propensity for light damage in mutant mice having elevated lipofuscin due to deficiency in the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter Abca4 (Abca4−/− mice) and in mice devoid of lipofuscin owing to absence of Rpe65 (Rpe65rd12).

Methods.

Abca4−/−, Rpe65rd12, and wild-type mice were exposed to 430-nm light to produce a localized lesion in the superior hemisphere of retina. Bisretinoids of RPE lipofuscin were measured by HPLC. In histologic sections, outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness was measured as an indicator of photoreceptor cell degeneration, and RPE nuclei were counted.

Results.

As shown previously, A2E levels were increased in Abca4−/− mice. These mice also sustained light damage–associated ONL thinning that was more pronounced than in age-matched wild-type mice; the ONL thinning was also greater in 5-month versus 2-month-old mice. Numbers of RPE nuclei were reduced in light-stressed mice, with the reduction being greater in the Abca4−/− than wild-type mice. In Rpe65rd12 mice bisretinoid compounds of RPE lipofuscin were not detected chromatographically and light damage–associated ONL thinning was not observed.

Conclusions.

Abca4−/− mice that accumulate RPE lipofuscin at increased levels were more susceptible to retinal light damage than wild-type mice. This finding, together with results showing that Rpe65rd12 mice did not accumulate lipofuscin and did not sustain retinal light damage, indicates that the bisretinoids of retinal lipofuscin are contributors to retinal light damage.

Keywords: Abca4, bisretinoid, light, lipofuscin, retina, retinal degeneration, retinal pigment epithelium

Fluorophores of the lipofuscin that accumulates in RPE contribute to mechanisms involved in light damage to retina.

Introduction

It is well known that the retina is subject to photochemical damage when exposed to prolonged periods of light of increased intensity.1,2 Light damage to both photoreceptor cells and retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells has been observed. However, the mechanisms that lead to the damage and which irradiance levels can be considered safe are not completely understood. Conclusions as to whether photoreceptor cells or RPE are damaged first and which cells are affected more severely have varied. For instance, the loss of photoreceptors cells is greatest when intense light exposure begins during the normal nighttime phase of the diurnal cycle.3,4 The death of both cell types occurs by means of programmed apoptotic processes.5,6 Two action spectra for photochemical damage to the retina have been described: one adheres to the absorption spectrum of rhodopsin and has been recorded by using long exposures (>24 hours) at low irradiances,7,8 while the other exhibits decreasing thresholds at shorter wavelengths and is associated with high irradiances and shorter exposure periods.9,10

Light-induced retinal injury is linked to the availability of the 11-cis-retinal chromophore of visual pigment. This feature is evidenced by the protection against light damage provided by conditions that block or slow the regeneration of 11-cis-retinal. These conditions include null mutations in Rpe6511 and lecithin:retinol acyltransferase12; amino acid variants in Rpe6513,14; systemic delivery of 13-cis-retinoic acid15; and halothane anesthesia that interferes with 11-cis-retinal binding to the opsin molecule.16 On the other hand, an increase in rhodopsin content in rod outer segments increases light damage susceptibility.17 Studies18 also indicate that the superior hemisphere of rat retina may be more sensitive to phototoxicity because of greater concentrations of rhodopsin.

Although light exposure triggers photoreceptor cell apoptosis only after photo-isomerization of visual pigment, phototransduction may not be necessary.6,12,19 Products of bleaching such as all-trans-retinal (λmax ∼380 nm),6,12 or metarhodopsin II20,21 have been suggested as the damaging agent. An extensive bleach of rhodopsin can potentially release ∼3 mM all-trans-retinal,21 yet a single bleaching event does not induce photoreceptor cell death in mice.6 Moreover, all-trans-retinal has an absorbance maximum of 380 nm and only little absorbance above 450 nm22; at these longer wavelengths retinal photodamage readily occurs.

Since repetitive photon absorption is required to elicit retinal damage, photoproducts formed after sustained activation of rhodopsin could accumulate and act as photosensitizers causing cellular damage.7,23 Potential initiators that fit this description are the lipofuscin fluorophores of retina. The vitamin A aldehyde–derived fluorophores of this lipofuscin form in photoreceptor cells as byproducts of photon absorbance by the 11-cis-retinal chromophore of visual pigment; this origin is consistent with evidence coupling retinal light damage to activation of visual pigment. Under conditions of dark-rearing, the bisretinoids of lipofuscin probably also form from reactions of 11-cis-retinal.24 After being transferred to RPE when shed outer segments are phagocytosed, these fluorophores subsequently accumulate as lipofuscin in the lysosomal compartment of RPE. Significantly, native lipofuscin in the RPE exhibits an excitation spectrum with a range of approximately 425 to 580 nm and a peak at approximately 480 nm.25 Individual bisretinoid fluorophores that have been identified exhibit excitation maxima at 435, 439, 443, 490, and 510 nm.26–29 These relatively long excitation wavelengths are enabled by carbon–carbon double bonds that form extended conjugation systems in the bisretinoid molecules. Lipofuscin isolated from RPE cells can serve as a photo-inducible generator of singlet oxygen and superoxide anion and in the presence of light and RPE lipofuscin, lipid undergoes peroxidation.30–33 Retinal pigment epithelium cells that contain lipofuscin or one of its constituents, A2E, are subject to mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage and a loss of viability.34–38

To examine the role of RPE lipofuscin as a mediator of light damage, we studied the susceptibility to light damage of wild-type mice as compared to mice burdened with elevated RPE lipofuscin due to a null mutation in the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter Abca4 (Abca4−/− mice). We also studied mice that do not synthesize lipofuscin owing to deficiency in Rpe65 (Rpe65rd12).

Methods

Mice

Albino Abca4/Abcr null mutant mice and Abca4/Abcr wild-type mice (homozygous for Rpe65-Leu450), were generated and genotyped by PCR amplification of tail DNA.39,40 For genotyping of the murine Rpe65 variant, digestion of the 545-bp product with MwoI restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) indicated the Leu450 variant if 180- and 365-bp fragments were generated. Rpe65rd12 mice and C57BL/6J mice (homozygous for Rpe65-Met450) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were raised under 12-hour on–off cyclic lighting with in-cage illuminance of 30 to 80 lux. All procedures involving animals adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. The proposed research involving animals has been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

A2E was measured by HPLC as we have described previously.39,41 Briefly, murine eyecups were homogenized, extracted in chloroform/methanol (2:1) and after drying, the extract was redissolved in 50% methanolic chloroform containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic (TFA) and analyzed by reverse phase HPLC (Alliance System; Waters Corp., Milford, MA) using a dC18 column. Gradients of water and acetonitrile with 0.1 % TFA were used for the mobile phase. Chromatographic peak areas were determined by using Empower software (Waters Corp.), and molar quantity per eye was calculated by using external standards of synthesized compounds, the structures of which have been confirmed.27,29,42

Light Exposure

Mice were anesthetized with 80 mg/kg ketamine and 5 mg/kg xylazine, anesthesia that does not interfere with light-damage models.43 Pupils of right eyes were dilated with phenylephrine hydrochloride (2.5%; Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, TX) and cyclopentolate hydrochloride (0.5%, Alcon Laboratories), and ViscoTears Liquid Gel (2 mg/g; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, North Ryde, NSW, Australia) was applied to the surface of the cornea to maintain hydration and clarity. The cornea was positioned at a constant distance from the light source and to eliminate light scatter at the corneal surface, a thin glass plate (diameter, 7.5 mm; thickness, 0.4 mm) was placed on the cornea; light lost by absorption was <10%. Light intensity was measured with a Newport optical power meter (model 840; Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA). Light (430 ± 20 nm) was delivered to the superior hemisphere of the retina from a mercury arc lamp at an intensity of 50 mW/cm2 for 30 minutes.43 Throughout the period of illumination the operator carefully observed the positioning so as to re-adjust if shifts in the position occurred. Right eyes were light exposed and left eyes served as unexposed controls.

Histometric Analysis

Seven days after light exposure, eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours at room temperature. Hematoxylin-eosin–stained, sagittal, 6-mm paraffin sections were prepared. For measurement of outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness, three sections through the optic nerve head (ONH) of each eye were imaged digitally (Leica Microsystems, Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) with an ×10 objective, and ONL thickness was measured at 200-μm intervals from the ONH to a position 2.4 mm superior and inferior to the ONH along the vertical meridian. Outer nuclear layer width in pixels was converted to micrometers (1 pixel = 0.92 μm) and data from the three sections were averaged. For groups of Abca4−/− and Abca4+/+ mice at each age, mean ONL thickness at each position along the vertical meridian was plotted as a function of eccentricity from the ONH.44,45 Outer nuclear layer area was calculated as the sum of the ONL thicknesses in superior hemiretina (ONH to 1.0 mm) with multiplication by the measurement interval of 0.2 mm.

To count RPE nuclei, three sections through the ONH were imaged with the ×40 objective. Nuclei were counted within 200-μm intervals beginning at the edge of the ONH and continuing superiorly along the vertical axis. Data from the three sections were averaged to obtain mean values for each measurement interval. Mean nuclei numbers within the 0.2-mm measurement intervals were plotted as a function of distance from ONH to 1.6 mm superiorly. Counts were also summed to obtain total numbers of RPE.

Statistical Analysis

Significance was assessed at the 0.05 level (Prism 6; GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) by using statistical tests as indicated.

Results

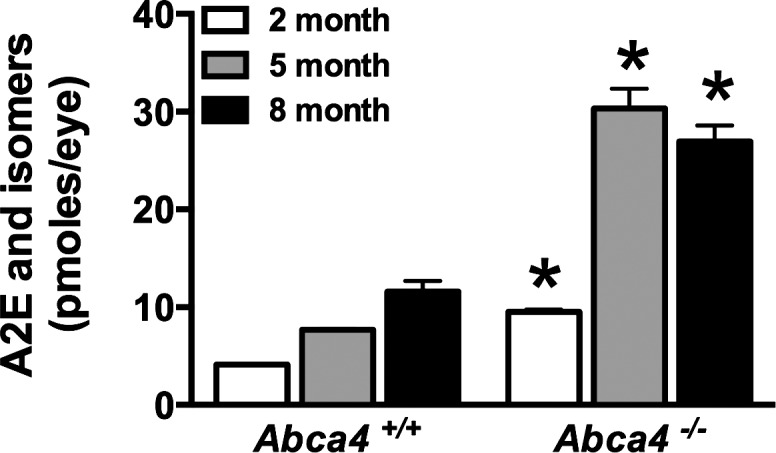

HPLC Quantitation of A2E

As formerly reported,20,39,46 deficiency in Abca4 was associated with substantial accumulations of lipofuscin pigments in the RPE (Fig. 1). We quantified A2E, a bisretinoid compound of RPE lipofuscin, by integrating HPLC peaks and normalizing to a calibration curve. A2E levels in the Abca4−/− mice were 3.8-fold greater than in wild-type mice at 5 months of age. However, the pattern of change in the two groups of mice was different. Specifically, while A2E increased steadily from 2 to 8 months of age in the Abca4+/+ mice, the amounts in Abca4−/− mice rose between 2 and 5 months of age and then leveled off at 8 months of age (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

HPLC quantitation of A2E in eyes of Abca4+/+ and Abca4−/− mice, age 2 to 8 months. A2E, its minor isomers, and isoA2E were measured separately and summed. Values are the mean ± SEM (2–5 samples per mean, 4–8 eyes per sample). *P < 0.01 when age-matched Abca4+/+ and Abca4−/− mice were compared by unpaired two-tailed t-test.

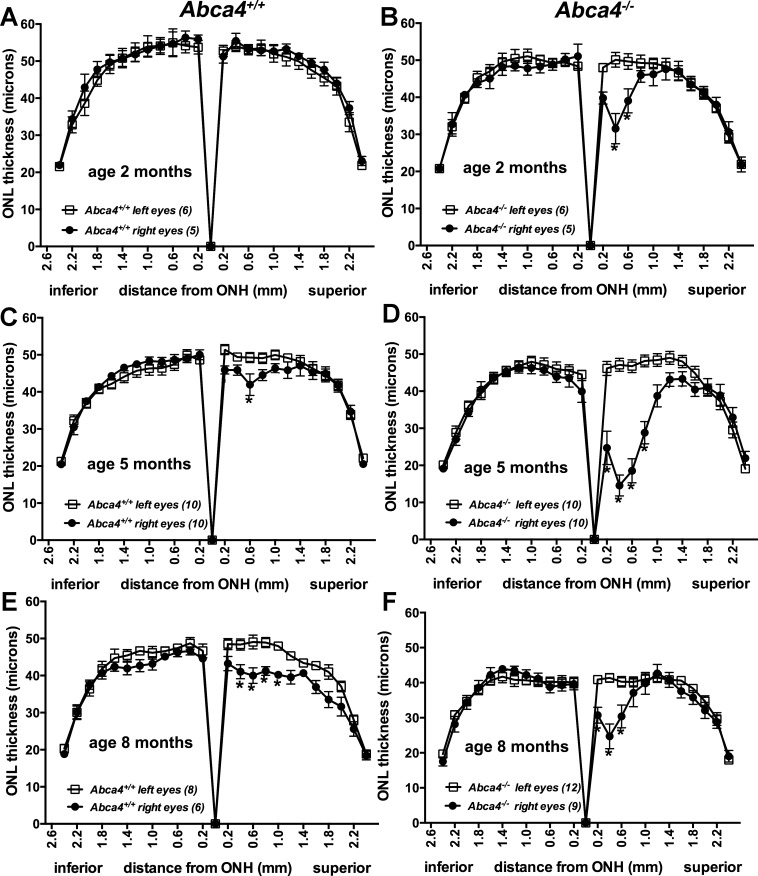

ONL Thickness

Consistent with previous work,43 our light damage model yielded a lesion in superior central retina; the lesion size was ∼800 μm along the vertical meridian. The measurement of ONL is an established approach to assessing photoreceptor cell integrity. Thus, to detect the light-induced lesion, we measured and plotted ONL thicknesses as a function of distance superior and inferior to the optic nerve head in the vertical plane (Fig. 2). In wild-type (Abca4+/+) mice at 2 months of age, no ONL thinning was observed in superior hemiretina of light-stressed (right) eyes after 1 week (Fig. 2A). Conversely, ONL width was reduced in superior retina of light-exposed eyes of Abca4 null mutant mice, with the differences at the 0.4- and 0.6-mm positions being statistically significant (P < 0.05; one-way ANOVA and Sidak's multiple comparison test; Fig. 2B). For mice at 5 months of age, 430-nm light induced a superior lesion in both the Abca4+/+ (0.6 mm, right versus left; P > 0.05) and Abca4−/− (0.2–0.8 mm, right versus left; P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA and Sidak's multiple comparison test) hemiretina, although visual inspection revealed that ONL thinning was more pronounced in the Abca4 null mutant versus wild-type mice (Figs. 2C, 2D, respectively). The lesions in the 8-month-old Abca4−/− and Abca4+/+ superior hemiretinae (Figs. 2E, 2F) were also distinct. However, although the difference between exposed and unexposed retinas in Abca4−/−mice was significant (0.2–0.6 mm, right versus left; P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA and Sidak's multiple comparison test), the plots of ONL thickness revealed that the lesions in the Abca4−/−mice were less pronounced at 8 months of age than at age 5 months. In this regard it was also apparent that even in the absence of experimental light damage (Fig. 2F, left eyes), ONL width was reduced in the 8-month-old Abca4−/− mice; this observation has been previously reported.40,47,48 Thus, in the case of the 8-month-old Abca4−/−mice, experimental light exposure was delivered on a background of genetically induced photoreceptor cell degeneration.

Figure 2.

ONL thicknesses measured in Abca4+/+ (A, C, E) and Abca4−/− (B, D, F) mice, both light-stressed (right) and control (non–light-stressed; left) eyes of 2-, 5-, and 8-month-old mice 7 days after light exposure. Values are mean ± SEM of numbers of eyes presented in parentheses. *P < 0.05 when right eyes were compared to left eyes by one-way ANOVA and Sidak's multiple comparison test. The lesions present as areas of reduced ONL thickness in superior retinae.

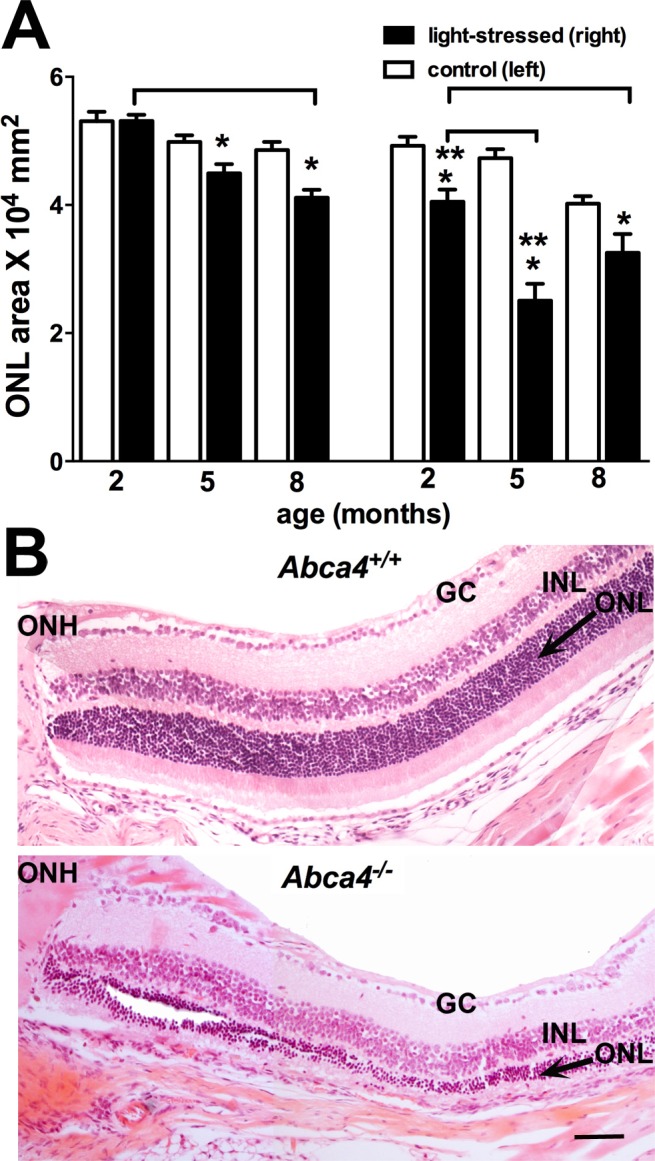

For further quantitation, we also calculated ONL area by summing ONL thicknesses in superior hemiretina (0.2–1.0 mm) and multiplying by the measurement interval of 0.2 mm (Fig. 3A). For the Abca4+/+ mice exposed to 430-nm light, ONL area was not reduced at 2 months of age. However, at 5 and 8 months of age, ONL area was decreased by 9% (P < 0.05) and 15% (P < 0.05), respectively, when compared to the control (left eyes, paired t-test). In the Abca4−/− mice, ONL area in light-exposed eyes (right) was decreased by 19% even at 2 months of age (P > 0.05, right versus left, paired t-test), and at 5 months of age, the reduction reached 47% (P < 0.05, left versus right eyes, paired t-test). The reduction in ONL area associated with light stress was also significantly greater in the Abca4−/− versus Abca4+/+ mice at 2 and 5 months of age when compared to wild type (P < 0.05, unpaired t-test). In addition, an effect of age was observed, with the light-induced ONL thinning in Abca4−/− mice being greater at 5 months than at 2 months and thinning in Abca4+/+ mice being greater at 8 months than at 2 months (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison test). Shown in Figure 3B are representative images of hematoxylin-eosin–stained superior retinae from Abca4+/+ and Abca4−/− mice (age 5 months). In the Abca4−/− mice, ONL thickness was severely reduced as compared to wild type.

Figure 3.

ONL thinning in light-stressed Abca4−/− and Abca4+/+ mice. (A) ONL areas in superior hemiretinae of right (light-stressed) and left (nonstressed control) eyes 1 week after light irradiation. ONL area was calculated by summing thickness measurements (0.2–1.0 mm from ONH) and multiplying by 0.2 mm. Values are means ± SEM of 5 to 11 mice. *P < 0.05, right eyes as compared to fellow left eyes (paired t-test); **P < 0.05, right eyes of Abca4−/− mice as compared to age-matched right eyes of Abca4+/+ mice (unpaired t-test, P < 0.05); bracket indicates P < 0.05, in Abca4+/+ mice, age 2 vs. 8 months, and in Abca4−/− mice, 2 vs. 5 months of age (ANOVA and Tukey's multiple comparison test). (B) Representative light micrographs of superior hemiretina of right eyes of 5-month-old Abca4+/+ (upper) and Abca4−/− (lower) mice 1 week after short-wavelength light exposure. Scale bar: 50 μm. GC, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer.

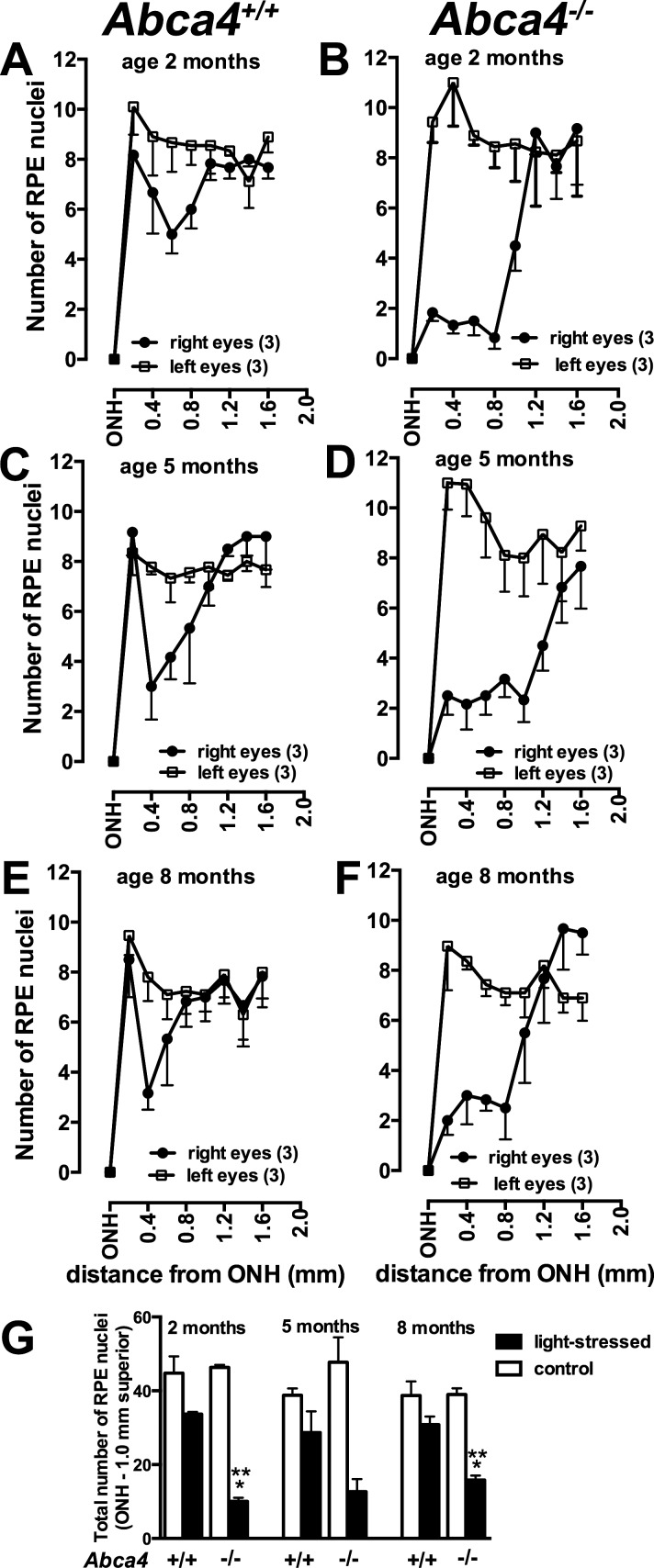

Counting of RPE nuclei within superior hemiretina also revealed a loss of RPE in light-stressed Abca4+/+ and Abca4−/− mice, the reduction being greater with the null mutation (Figs. 4A–F). For comparative purposes we calculated the sum of the nuclei counted within the RPE monolayer from the ONH to a distance 1.0 mm superiorly (Fig. 4G). In the wild-type eyes, RPE cell numbers in light-stressed (right) eyes were reduced by 20% to 26% (ages 2–8 months when compared to left control; P > 0.05, paired t-test), while in Abca4−/− mice the reduction ranged from 59% to 78% (P < 0.05, paired t-test). At 2 and 8 months of age, the reduction in RPE nuclei in the Abca4−/− mice was more pronounced than the reduction in the Abca4+/+ mice (P < 0.05, unpaired t-test).

Figure 4.

Effect of light stress on RPE cells in superior retina of Abca4+/+ and Abca4−/− mice. (A–F) Numbers of RPE cells (mean ± SEM) counted within 0.2-mm intervals and plotted as function of distance from ONH in superior hemiretina at 2, 5, and 8 months of age in Abca4+/+ (A, C, E) and Abca4−/− mice (B, D, F). (G) Total numbers of RPE cells from ONH to 1.0 mm along vertical axis in superior hemisphere of light-stressed (right) and control non–light-stressed eyes of Abca4+/+ and Abca4−/− mice at 2, 5, and 8 months of age (mean ± SEM; means are based on three values). *P < 0.05 as compared to fellow control eye; paired t-test; **P < 0.05 light-stressed Abca4+/+ versus Abca4−/− mice; unpaired t-test.

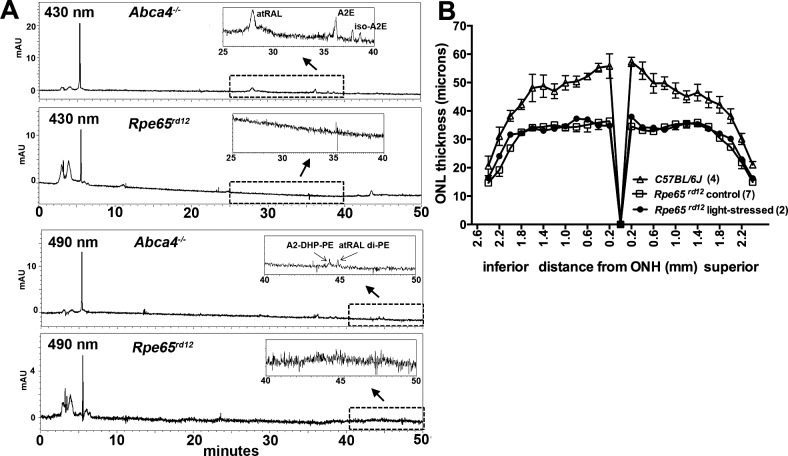

Light Damage and the Rpe65rd12 Mouse

The Rpe65rd12 mouse is characterized by loss of function of Rpe65 due to a naturally occurring severe truncation of the protein together with nonsense-mediated mRNA degradation.49 It has previously been reported that Rpe65 null mutation prevents an accumulation of the RPE fluorescence attributable to lipofuscin.50 Consistent with the latter observation, we found that bisretinoids of lipofuscin were not detected in Rpe65rd12 mice (Fig. 5). The bisretinoids examined chromatographically (Fig. 5A) included A2E, A2E isomers, A2-DHP-PE (dihydropyridine-phosphatidylethanolamine), and atRAL dimer–PE (all-trans-retinal dimer phosphatidylethanolamine). Rpe65 deficiency is also reported to confer a resistance to light damage.11 Thus, we tested our light damage model under conditions of a null mutation in Rpe65 by submitting Rpe65rd12 mice (5 months of age) to 430 ± 20 nm light (50 mW/cm2 for 30 minutes). There was no difference in ONL thickness in light-stressed (right) compared to non–light-stressed (left) eyes of Rpe65rd12 mice (P > 0.05, 0.2–2.0 mm, right versus left eyes; P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA and Sidak's multiple comparison test; Fig. 5B). Thinning was, however, observed owing to the Rpe65 mutation. Specifically, when non–light-stressed Rpe65rd12 mice (age 5 months) were compared to C57BL/6J mice (age 6 months), there was a noticeable decrease in ONL thickness (Fig. 5B). This change was consistent with previous reports indicating that mice homozygous for the Rpe65rd12 mutation undergo thinning of ONL after 3 months of age, with a 50% reduction in rows of ONL nuclei being measurable in the Rpe65rd12 mutants by 7 months of age.49,51

Figure 5.

Light stress in Rpe65rd12 mice. (A) Reverse phase HPLC chromatograms with UV-visible detection at 430 and 490 nm. The bisretinoids A2E, A2-DHP-PE, and atRAL dimer–PE are detected in eyes of Abca4−/− mice (age 6 months; four eyes pooled/sample) but are not detected in Rpe65rd12 mice (age 8 months; eight eyes pooled/sample). (B) Measurement of ONL in light-exposed (right) and control (left) eyes of Rpe65rd12 mice, age 5 months. Thicknesses are plotted as distance from ONH. C57BL/6J mice (6 months) served as wild type. Values are mean ± SEM of numbers of eyes presented in parentheses.

Discussion

Here we reported that a mutant mouse line (Abca4−/−) that accumulates RPE lipofuscin at amplified levels is more susceptible to short-wavelength light damage than wild-type mice. A2E, one of the components of lipofuscin, was 3.8-fold more abundant at 5 months of age in Abca4−/− mice than wild-type mice. In 5-month-old light-stressed Abca4−/− mice, ONL area (0.2–1.0 mm from ONH), a measure of photoreceptor cell viability, was reduced by 47% relative to control fellow eyes, while the light-induced reduction in the wild-type eyes was only 10% at this age. Moreover, A2E amounts increased with age (2 vs. 5 months) in the Abca4−/− and wild-type (2, 5, and 8 months) mice, as did the severity of light damage. We observed that light-induced damage was more pronounced in central retina than the periphery. In this regard it is significant that the level of A2E, just one of the bisretinoids of lipofuscin, is also higher centrally in the mouse.52 These findings are consistent with a role for RPE lipofuscin in mediating light damage. A functional 11-cis-retinal chromophore is necessary to elicit retinal light damage,11,12 but a direct effect of the chromophore cannot explain these results, since rhodopsin and 11-cis-retinal levels are not different in Abca4−/− versus wild-type mice.20

Whereas Abca4 deficiency increases bisretinoid formation and light damage, we showed that an absence of Rpe65 activity abrogates bisretinoid formation (Fig. 5) and, as has been reported previously,11 the mice are correspondingly refractory to light damage (Fig. 5). Rpe65 activity is rate limiting in the visual cycle and the failure to generate 11-cis-retinal owing to Rpe65 deficiency is the cause of photoreceptor cell degeneration beginning at 3 months of age.49,51 The underlying photoreceptor cell degeneration in Rpe65rd12 mice is not likely to have obscured the effects of experimental light damage if it had occurred: reduced ONL width in the Abca4−/− mouse was measurable even when light stress was delivered on a background of gene-induced ONL thinning (i.e., age 8 months). While 11-cis-retinal is not detected in Rpe65−/− mice, a small light response can be elicited from isorhodopsin, the latter forming from low levels of 9-cis-retinal53; nevertheless, this level of photosensitivity is not sufficient to detect bisretinoid formation (Fig. 5). It is significant that even a reduction in Rpe65 activity, as in the case of the Rpe65 variant at amino acid 450 (leucine to methionine), is associated with reduced lipofuscin accumulation39 and correspondingly, with diminished sensitivity to light damage.13,14

We note that the effects of genetically induced photoreceptor cell degeneration combined with experimental light damage were not additive in the Abca4−/− model. This observation can be made by inspecting ONL thinning in the light-stressed Abca4−/− mice at 5 and 8 months of age (Fig. 2). Specifically, the reduction in ONL thickness attributable to experimental light damage when light stress was delivered on a background of genetically induced photoreceptor cell degeneration (age 8 months) was less pronounced than at a younger age (age 5 months) preceding the onset of genetically induced photoreceptor cell death. Among the explanations for this effect could be the possibility that the two cell-death stimuli share a common downstream molecular pathway or that the underlying genetically induced photoreceptor cell degeneration elicits cell survival mechanisms that partially protect against subsequent light damage.

Various chromophores in RPE have been suggested to mediate short-wavelength light damage, including riboflavin, the mitochondrial enzyme cytochrome c oxidase, and melanin.23,54–58 However, riboflavin and cytochrome c oxidase are not expected to increase with a null mutation in Abca4 or with age, and these molecules would not be modulated by Rpe65 knockout. Ocular melanin can be excluded as a damaging agent, since pigmented and albino animals are equally susceptible to retinal light damage.56,59 In fact, ocular melanin decreases retinal irradiance, thereby lengthening the time to retinal damage. In another model, the Rdh8−/−Rdh12−/−Abca4−/− mouse, A2E levels were also many-fold greater than in wild type, and photoreceptor cell degeneration 7 days after a 30-minute white light exposure (10,000 lux)60 was more pronounced than in wild-type retinas. In this case, however, the damaging agent was assumed to be all-trans-retinal.

While most studies of light damage address photoreceptor cell loss, the site of origin of light damage in primates may be photoreceptor outer segments and/or RPE cells; indeed, some investigators have reported the greatest damage in RPE cells.9,61–65 In the work presented here, we observed light-induced loss of both RPE and photoreceptor cells. The light stress–induced reduction of RPE numbers was greater with the Abca4−/− null mutation than in wild type; however, for reasons unknown to us, we were unable to detect an age-related increase in light stress–induced RPE loss in the wild-type and null mutant mice. We cannot draw conclusions as to whether damage was initiated in photoreceptor cells and RPE independently or whether for instance, the primary injury resided in RPE cells, with the loss of photoreceptor cells following owing to the dependence of photoreceptor cells on RPE functioning. The formation of the pigments of RPE lipofuscin begins in photoreceptor outer segments with transfer to the RPE when these cells phagocytose packets of distal outer segment membrane.25 Accordingly, bisretinoids are present in both photoreceptor cells and RPE, although owing to outer segment shedding, bisretinoids in photoreceptor cells are kept to a minimum and instead accumulate in RPE. We found that in both Abca4+/+ and Abca4−/− mice, the severity of the acute light-induced ONL thinning was greater in older mice. Since the bisretinoids of lipofuscin accumulate in RPE cells with age, the age-related increase in retinal light damage we observed may point to injury that is initiated in RPE cells. In general, whether damage occurs primarily in the RPE versus photoreceptor cells, or both, may depend on the paradigm under which light is delivered. For instance, since long-duration light-damage models could allow for regeneration of visual pigment and repeated bleaching, formation of bisretinoids in photoreceptor cells may be promoted under these conditions, thus increasing the likelihood of primary photoreceptor cell damage. It is reported that photoreceptor cell damage is initiated distally in the outer segment and subsequently progresses to include the entire length of the outer segment.18,66 While this observation may be explained by apical–basal differences in the lipid composition of the outer segment membrane,2 another factor could be that apically situated more aged discs contain higher levels of the bisretinoid compounds that become the lipofuscin of RPE.

Photo-oxidative mechanisms are clearly involved in retinal light damage, since antioxidants can protect against photic damage, and increased oxygen availability lowers the threshold.61,67–69 Inhibition of NADPH oxidase activity also suppresses rod photoreceptor light-induced degeneration.70 A role for antioxidants in protection against light damage is significant since bisretinoids are well known to be capable of short-wavelength light-induced singlet oxygen generation, with the latter reacting back at carbon–carbon double bonds and thereby photo-oxidizing the bisretinoid.71 Interestingly, TEMPOL-H, a compound having antioxidant properties, has been shown both to inhibit A2E photo-oxidation elicited by short-wavelength light exposure72 and to protect against light-induced damage to both photoreceptor cells and RPE.73,74 Of additional note, the increase in retinal proteins modified by the reactive aldehyde 4-hydroxynonenal, a product of polyunsaturated fatty acid oxidation, is a feature of retinal light damage in rats45 and of cultured RPE cells that have accumulated A2E and are irradiated with short-wavelength light.75

The photo-oxidation and photodegradation of bisretinoid injure cells36,38 and can be visualized as photobleaching, a light-induced decline in fluorescence.76 Evidence that lipofuscin photobleaching is linked to RPE cell death in vivo has been provided by observations made during imaging of the RPE monolayer by fluorescence adaptive optics scanning light ophthalmoscopy in nonhuman primates. At irradiance levels below American National Standards Institute safety standards an abrupt autofluorescence bleaching of RPE lipofuscin is detected.77,78 Depending on the retinal irradiance, the immediate decrease in the magnitude of lipofuscin autofluorescence emission either recovers (≤210 J/cm2) after a few days or progresses to structural disruption of the RPE mosaic (≥247 J/cm2), consistent with RPE photodamage. This photo-injury is observed at both 488- and 568-nm exposures and it occurs even when photoreceptor cells appear normal.

We have previously demonstrated that albino Abca4−/− mice undergo photoreceptor cell loss that can readily be detected at 8 months of age and that is not observed in age-matched wild-type mice. This genetically induced ONL thinning is more pronounced in superior hemisphere of retina40,47 and, given our present findings, may be linked to ambient light exposure. Our present findings indicate that light is likely a critical mediator of bisretinoid toxicity. Accordingly, it has been suggested that patients with macular ABCA4 disease should be protected from unnecessary light exposure.79 The present findings are also significant since the progression of retinal degeneration in some forms of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) may be aggravated by light exposure.80 Light-mediated perturbation has also been demonstrated in animal models of RP, including those carrying mutations in rhodopsin.81–84 Thus, perhaps small-molecule therapeutics that combat overproduction of bisretinoid formation could aid in preserving photoreceptor cells in some forms of RP, until other forms of therapy (e.g., gene therapy) can be delivered. While epidemiologic studies85–88 have reported conflicting views regarding a role for light exposure in AMD pathogenesis, the European Eye Study89 has concluded that there is a significant association between light exposure and AMD in subjects with a low intake of antioxidants.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1 EY12951, RO1 EY004367, and P30EY019007 and by a grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to the Department of Ophthalmology, Columbia University.

Disclosure: L. Wu, None; K. Ueda, None; T. Nagasaki, None; J.R. Sparrow, None

References

- 1. Hunter JJ, Morgan JI, Merigan WH, Sliney DH, Sparrow JR, Williams DR. The susceptibility of the retina to photochemical damage from visible light. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012; 31: 28–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Organisciak DT, Vaughan DK. Retinal light damage: mechanisms and protection. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2010; 29: 113–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Organisciak DT, Darrow RA, Barsalou L, Kutty RK, Wiggert B. Circadian-dependent retinal light damage in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41: 3694–3701 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beatrice J, Wenzel A, Reme CE, Grimm C. Increased light damage susceptibility at night does not correlate with RPE65 levels and rhodopsin regeneration in rats. Exp Eye Res. 2003; 76: 695–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hafezi F, Marti A, Munz K, Reme CE. Light-induced apoptosis: differential timing in the retina and pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res. 1997; 64: 963–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wenzel A, Grimm C, Samardzija M, Reme CE. Molecular mechanisms of light-induced photoreceptor apoptosis and neuroprotection for retinal degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005; 24: 275–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Noell WK, Walker VS, Kang BS, Berman S. Retinal damage by light in rats. Invest Ophthalmol. 1966; 5: 450–473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams TP, Howell WL. Action spectrum of retinal light damage in albino rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1983; 24: 285–287 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ham WT, Mueller HA. Retinal sensitivity to damage from short wavelength light. Nature. 1976; 260: 153–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Norren D, Gorgels TGMF. The action spectrum of photochemical damage to the retina: a review of monochromatic threshold data. Photochem Photobiol. 2011; 87: 747–753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grimm C, Wenzel A, Hafezi F, Yu S, Redmond TM, Reme CE. Protection of Rpe65-deficient mice identifies rhodopsin as a mediator of light-induced retinal degeneration. Nat Genet. 2000; 25: 63–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maeda A, Maeda T, Golczak M, et al. Involvement of all-trans-retinal in acute light-induced retinopathy of mice. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284: 15173–15183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Danciger M, Matthes MT, Yasamura D, et al. A QTL on distal chromosome 3 that influences the severity of light-induced damage to mouse photoreceptors. Mamm Genome. 2000; 11: 422–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wenzel A, Reme CE, Williams TP, Hafezi F, Grimm C. The Rpe65 Leu450Met variation increases retinal resistance against light-induced degeneration by slowing rhodopsin regeneration. J Neurosci. 2001; 21: 53–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sieving PA, Chaudhry P, Kondo M, et al. Inhibition of the visual cycle in vivo by 13-cis retinoic acid protects from light damage and provides a mechanism for night blindness in isotretinoin therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001; 98: 1835–1840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Keller GA, Grimm C, Wenzel A, Hafezi F, Reme CE. Protective effects of halothane anesthesia on retinal light damage: inhibition of metabolic rhodopsin regeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 476–480 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rapp LM, Tolman BL, Koutz CA, Thum LA. Predisposing factors to lightinduced photoreceptor cell damage: retinal changes in maturing rats. Exp Eye Res. 1990; 51: 177–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vaughan DK, Nemke JL, Fliesler SJ. Evidence for a circadian rhythm of susceptibility to retinal light damage. Photochem Photobiol. 2002; 75: 547–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hao W, Wenzel A, Obin MS, et al. Evidence for two apoptotic pathways in light-induced retinal degeneration. Nat Genet. 2002; 32: 254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weng J, Mata NL, Azarian SM, Tzekov RT, Birch DG, Travis GH. Insights into the function of Rim protein in photoreceptors and etiology of Stargardt's disease from the phenotype in abcr knockout mice. Cell. 1999; 98: 13–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lamb TD, Pugh EN. Dark adaptation and the retinoid cycle of vision. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004; 23: 307–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Becker RS, Inuzuka K, Balke DE. Comprehensive investigation of the spectroscopy and photochemistry of retinals, I: theoretical and experimental considerations of absorption spectra. J Am Chem Soc. 1971; 93: 38–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mellerio J. Light effects on the retina. In: DM Albert, Jakobiec FA. eds Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology: Basic Science. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co; 1994; 1326–1345 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boyer NP, Higbee D, Currin MB, et al. Lipofuscin and N-retinylidene-N-retinylethanolamine (A2E) accumulate in the retinal pigment epithelium in the absence of light exposure: their origin is 11-cis retinal. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287: 22276–22286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sparrow JR, Boulton M. RPE lipofuscin and its role in retinal photobiology. Exp Eye Res. 2005; 80: 595–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamamoto K, Yoon KD, Ueda K, Hashimoto M, Sparrow JR. A novel bisretinoid of retina is an adduct on glycerophosphoethanolamine. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 9084–9090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parish CA, Hashimoto M, Nakanishi K, Dillon J, Sparrow JR. Isolation and one-step preparation of A2E and iso-A2E, fluorophores from human retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998; 95: 14609–14613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kim SR, Jang YP, Jockusch S, Fishkin NE, Turro NJ, Sparrow JR. The all-trans-retinal dimer series of lipofuscin pigments in retinal pigment epithelial cells in a recessive Stargardt disease model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007; 104: 19273–19278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wu Y, Fishkin NE, Pande A, Pande J, Sparrow JR. Novel lipofuscin bisretinoids prominent in human retina and in a model of recessive Stargardt disease. J Biol Chem. 2009; 284: 20155–20166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gaillard ER, Atherton SJ, Eldred G, Dillon J. Photophysical studies on human retinal lipofuscin. Photochem Photobiol. 1995; 61: 448–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rozanowska M, Jarvis-Evans J, Korytowski W, Boulton ME, Burke JM, Sarna T. Blue light-induced reactivity of retinal age pigment: in vitro generation of oxygen-reactive species. J Biol Chem. 1995; 270: 18825–18830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Boulton M, Dontsov A, Jarvis-Evans J, Ostrovsky M, Svistunenko D. Lipofuscin is a photoinducible free radical generator. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1993; 19: 201–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wassell J, Davies S, Bardsley W, Boulton M. The photoreactivity of the retinal age pigment lipofuscin. J Biol Chem. 1999; 274: 23828–23832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Godley BF, Shamsi FA, Liang FQ, Jarrett SG, Davies S, Boulton M. Blue light induces mitochondrial DNA damage and free radical production in epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005; 280: 21061–21066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schutt F, Davies S, Kopitz J, Holz FG, Boulton ME. Photodamage to human RPE cells by A2-E, a retinoid component of lipofuscin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41: 2303–2308 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sparrow JR, Cai B. Blue light-induced apoptosis of A2E-containing RPE: involvement of caspase-3 and protection by Bcl-2. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 1356–1362 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sparrow JR, Nakanishi K, Parish CA. The lipofuscin fluorophore A2E mediates blue light-induced damage to retinal pigmented epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000; 41: 1981–1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sparrow JR, Vollmer-Snarr HR, Zhou J, et al. A2E-epoxides damage DNA in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Vitamin E and other antioxidants inhibit A2E-epoxide formation. J Biol Chem. 2003; 278: 18207–18213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim SR, Fishkin N, Kong J, Nakanishi K, Allikmets R, Sparrow JR. The Rpe65 Leu450Met variant is associated with reduced levels of the RPE lipofuscin fluorophores A2E and iso-A2E. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004; 101: 11668–11672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wu L, Nagasaki T, Sparrow JR. Photoreceptor cell degeneration in Abcr−/− mice. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010; 664: 533–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim SR, Nakanishi K, Itagaki Y, Sparrow JR. Photooxidation of A2-PE, a photoreceptor outer segment fluorophore, and protection by lutein and zeaxanthin. Exp Eye Res. 2006; 82: 828–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fishkin N, Sparrow JR, Allikmets R, Nakanishi K. Isolation and characterization of a retinal pigment epithelial cell fluorophore: an all-trans-retinal dimer conjugate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005; 102: 7091–7096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grimm C, Wenzel A, Williams TP, Rol PO, Hafezi F, Reme CE. Rhodopsin-mediated blue-light damage to the rat retina: effect of photoreversal of bleaching. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 497–505 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mittag TW, Bayer AU, LaVail MM. Light-induced retinal damage in mice carrying a mutated SOD I gene. Exp Eye Res. 1999; 69: 677–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tanito M, Elliot MH, Kotake Y, Anderson RE. Protein modifications by 4-hydroxynonenal and 4-hydroxyhexenal in light-exposed rat retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 3859–3868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maeda A, Maeda T, Golczak M, Palczewski K. Retinopathy in mice induced by disrupted all-trans-retinal clearance. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283: 26684–26693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sparrow JR, Blonska A, Flynn E, et al. Quantitative fundus autofluorescence in mice: correlation with HPLC quantitation of RPE lipofuscin and measurement of retina outer nuclear layer thickness. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 2812–2820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Radu RA, Yuan Q, Hu J, et al. Accelerated accumulation of lipofuscin pigments in the RPE of a mouse model for ABCA4-mediated retinal dystrophies following Vitamin A supplementation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 3821–3829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pang JJ, Chang B, Hawes NL, et al. Retinal degeneration 12 (rd12): a new, spontaneously arising mouse model for human Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). Mol Vis. 2005; 11: 152–162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Katz ML, Redmond TM. Effect of Rpe65 knockout on accumulation of lipofuscin fluorophores in the retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001; 42: 3023–3030 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Maeda T, Maeda A, Casadesus G, Palczewski K, Margaron P. Evaluation of 9-cis-retinyl acetate therapy in Rpe65-/- mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 4368–4378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Grey AC, Crouch RK, Koutalos Y, Schey KL, Ablonczy Z. Spatial localization of A2E in the retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011; 52: 3926–3933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fan J, Rohrer B, Frederick JM, Baehr W, Crouch RK. Rpe65-/- and Lrat-/- mice: comparable models of Leber congenital amaurosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 2384–2389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Noell WK. Possible mechanisms of photoreceptor damage by light in mammalian eyes. Vis Res. 1980; 20: 1163–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reme CE, Hafezi F, Marti A, Munz K, Reinboth JJ. Light Damage to Retina and Retinal Pigment Epithelium. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998; 68–85 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Organisciak DT, Winkler BS. Retinal light damage:practical and theoretical considerations. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1994; 13: 1–29 [Google Scholar]

- 57. Boulton M. Melanin and the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pautler EL, Morita M, Beezley D. Hemoprotein(s) mediate blue light damage in the retinal pigment epithelium. Photochem Photobiol. 1990; 51: 599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hoppeler T, Hendrickson P, Dietrich C, Reme CE. Morphology and time-course of defined photochemical lesions in the rabbit retina. Curr Eye Res. 1988; 7: 849–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Maeda A, Golczak M, Maeda T, Palczewski K. Limited roles of Rdh8, Rdh12, and Abca4 in all-trans-retinal clearance in mouse retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 5435–5443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ham WT, Mueller HA, Ruffolo JJ, et al. Basic mechanisms underlying the production of photochemical lesions in the mammalian retina. Curr Eye Res. 1984; 3: 165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ham WTJ, Allen RG, Feeney-Burns L, et al. The involvement of the retinal pigment epithelium. In: Waxler M, Hitchins VM. eds CRC Optical Radiation and Visual Health. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, Inc; 1986; 43–67 [Google Scholar]

- 63. Friedman E, Kuwabara T. The retinal pigment epithelium, IV: the damaging effects of radiant energy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1968; 80: 265–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Busch EM, Gorgels TGMF, Roberts JE, van Norren D. The effects of two stereoisomers of N-acetylcysteine on photochemical damage by UVA and blue light in rat retina. Photochem Photobiol. 1999; 70: 353–358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ham WT, Ruffolo JJ, Mueller HA, Clarke AM, Moon ME. Histologic analysis of photochemical lesions produced in rhesus retina by short-wavelength light. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1978; 17: 1029–1035 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bush RA, Remé CE, Malnoë A. Light damage in the rat retina: the effect of dietary deprivation of N-3 fatty acids on acute structural alterations. Exp Eye Res. 1991; 53: 741–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Tanito M, Kaidzu S, Anderson RE. Protective effects of soft acrylic yellow filter against blue light-induced retinal damage in rats. Exp Eye Res. 2006; 83: 1493–1504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Organisciak DT, Darrow RM, Jiang YI, Marak GE, Blanks JC. Protection by dimethylthiourea against retinal light damage in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992; 33: 1599–1609 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Tomita H, Kotake Y, Anderson RE. Mechanism of protection from light-induced retinal degeneration by the synthetic antioxidant phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005; 46: 427–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Haruta M, Bush RA, Kjellstrom S, et al. Depleting Rac1 in mouse rod photoreceptors protects them from photo-oxidative stress without affecting their structure or function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 2009: 9397–9402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sparrow JR, Gregory-Roberts E, Yamamoto K, et al. The bisretinoids of retinal pigment epithelium. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012; 31: 121–135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhou J, Jang YP, Chang S, Sparrow JR. OT-674 suppresses photooxidative processes initiated by an RPE lipofuscin fluorophore. Photochem Photobiol. 2008; 84: 75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Tanito M, Li F, Elliot MH, Dittmar M, Anderson RE. Protective effect of TEMPOL derivatives against light-induced retinal damage in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007; 48: 1900–1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Tanito M, Li F, Anderson RE. Protection of retinal pigment epithelium by OT-551 and its metabolite TEMPOL-H against light-induced damage in rats. Exp Eye Res. 2010; 91: 111–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Zhou J, Cai B, Jang YP, Pachydaki S, Schmidt AM, Sparrow JR. Mechanisms for the induction of HNE- MDA- and AGE-adducts, RAGE and VEGF in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2005; 80: 567–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yamamoto K, Zhou J, Hunter JJ, Williams DR, Sparrow JR. Toward an understanding of bisretinoid autofluorescence bleaching and recovery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012; 53: 3536–3544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Morgan JI, Dubra A, Wolfe R, Merigan WH, Williams DR. In vivo autofluorescence imaging of the human and macaque retinal pigment epithelial cell mosaic. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009; 50: 1350–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Morgan JI, Hunter JJ, Masella B, et al. Light-induced retinal changes observed with high-resolution autofluorescence imaging of the retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008; 49: 3715–3729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cideciyan AV, Swider M, Aleman TS, Roman MI, Sumaroka A, Schwartz SB. Reduced-illuminance autofluorescence imaging in ABCA4-associated retinal degenerations. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2007; 24: 1457–1467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Cideciyan AV, Hood DC, Huang YZ, et al. Disease sequence from mutant rhodopsin allele to rod and cone photoreceptor degeneration in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998; 95: 7103–7108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Naash ML, Peachey NS, Li Z-Y, et al. Light-induced acceleration of photoreceptor degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant rhodopsin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996; 37: 775–782 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Wang M, Lam TT, Tso MO, Naash MI. Expression of a mutant opsin gene increases the susceptibility of the retina to light damage. Vis Neurosci. 1997; 14: 55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cideciyan AV, Jacobson SG, Aleman TS, et al. In vivo dynamics of retinal injury and repair in the rhodopsin mutant dog model of human retinitis pigmentosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005; 102: 5233–5238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Organisciak DT, Darrow RM, Barsalou L, Kutty RK, Wiggert B. Susceptibility to retinal light damage in transgenic rats with rhodopsin mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 486–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Tomany SC, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R, Klein BEK, Knudtson MD. Sunlight and the 10-year incidence of age-related maculopathy: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004; 122: 750–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. McCarty CA, Mukesh BN, Fu CL, Mitchell P, Wang JJ, Taylor HR. Risk factors for age-related maculopathy: the Visual Impairment Project. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001; 119: 1455–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hyman LG, Lilienfeld AM, Ferris FL, Fine SL. Senile macular degeneration: a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1983; 118: 213–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Delcourt C, Carriere I. Ponton-Sanchez A, Sourrey S, Lacroux A, Papoz L. Light exposure and the risk of age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001; 119: 1463–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Fletcher AE, Bentham GC, Agnew M, et al. Sunlight exposure, antioxidants, and age-related macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008; 126: 1396–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]