Abstract

We have determined the three-dimensional (3D) structure of DNA duplex that includes tandem HgII-mediated T–T base pairs (thymine–HgII–thymine, T–HgII–T) with NMR spectroscopy in solution. This is the first 3D structure of metallo-DNA (covalently metallated DNA) composed exclusively of ‘NATURAL’ bases. The T–HgII–T base pairs whose chemical structure was determined with the 15N NMR spectroscopy were well accommodated in a B-form double helix, mimicking normal Watson–Crick base pairs. The Hg atoms aligned along DNA helical axis were shielded from the bulk water. The complete dehydration of Hg atoms inside DNA explained the positive reaction entropy (ΔS) for the T–HgII–T base pair formation. The positive ΔS value arises owing to the HgII dehydration, which was approved with the 3D structure. The 3D structure explained extraordinary affinity of thymine towards HgII and revealed arrangement of T–HgII–T base pairs in metallo-DNA.

INTRODUCTION

The metal-mediated base pairs (the metallo base pairs) are currently being explored toward genetic code expansion (1–4), development of metallo-DNAs (5–12), molecular magnets (13,14), electric nano-wires (15–19) and metal ion-sensors (20,21). Among these, the HgII-sensor employing thymine–HgII–thymine (T–HgII–T) base pair was the first successful application (20).

The success of this HgII-sensor was owing to both the extraordinary HgII-thymine specificity and the thermal stability of T–HgII–T base pair (22–25). The thermal stability of the T–HgII–T base pair was similar as those of normal Watson–Crick (W–C) base pairs (24). Moreover, the positive ΔS recorded for T–HgII–T base pair formation with isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (24) indicated its peculiarity, since biomolecular complexations are usually linked with negative ΔS values (26,27). However, the lack of structural data for T–HgII–T base pairs in a DNA duplex prohibited rational explanation of this positive ΔS. In addition, as apparent from structure-based drug designs, the explanation of ΔS on structural basis is difficult and rarely possible. Therefore, the elucidation of entropic contributors from three-dimensional (3D) structures is challenging issue in structural biology/chemistry.

The metallo-DNA with T–HgII–T base pairs is regarded promising conductive nano-material. Several groups examined its ability to mediate hole/electron transport, and weak-hole transport similar to that in normal DNA was actually observed (15–18). However, as mentioned above, the lack of structural information for T–HgII–T pairs prevented rationalization of these experiments and tuning of conductivity in metallo-DNAs.

The binding mode of Hg atom in T–HgII–T base pair was surely determined using the 15N NMR and Raman spectroscopy (23,28,29). The theoretical calculations based on its structure suggested that the LUMOs appearing around HgII of the T–HgII–T base pair is distributed along the DNA-helical axis (29). Therefore, it is important to reveal mutual positioning of T–HgII–T base pairs in the metallo-DNA and to confirm if the overlap of their LUMOs is possible or not.

The metallophilic attraction between Hg atoms in consecutive T–HgII–T base pairs stabilizes structure of metallo-DNA although the Hg atoms in these metallo base pairs bear sizable positive charge (29–31). Only few observations of the metallophilic phenomenon were reported so far for some organometallic complexes. The 3D structure of metallo-DNA would provide reliable basis for physicochemical investigation of Hg–Hg metallophilic attraction.

The 3D structures of metallo-DNAs, which are currently available include solely those composed of ‘ARTIFICIAL bases’ (metal-chelators) (1,2,11). The structural information on metallo-DNAs composed of ‘NATURAL bases’ is therefore very sparse. Only the T–HgII–T base pair was thoroughly studied with molecular spectroscopy (23,28,29,32–36), 3D modeling (34) and the crystal structure of 1-methylthymine–HgII complex (37). Although the binding mode of HgII was determined in these studies, 3D structure of the metallo-DNA duplex remained unresolved.

The lack of structural information for the metallo-DNA duplex in solution made us initiate this study aiming particularly explanation of the thermodynamic parameters for T–HgII–T base pair formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Thermal denaturation experiment

DNA sequences used for this experiment are listed in Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S1. UV spectra of the solutions of DNA decamers were recorded every 3°C for ‘1•2(T–HgII–T)’ and ‘1•3(T – A)’, and every 2°C for ‘1•2(T–T)’ (Figure 2). In the temperature profiles, UV absorbances at 260 nm were plotted against temperature (Figure 2). The Tm value which is dependent on the nearest neighbour W–C base pairs against T–HgII–T base pairs was studied using a dodecamer hetero duplex: d(CCGCXTTVTCCG) • d(CGGAWTTYGCGG), where X–Y and V–W are W–C base pairs (Supplementary Figure S1). The effect of concentration of HgII-bound duplex 1•2 on Tm value was also examined (Supplementary Figure S2). The Tm values were determined using a method described in the literature (38). In all the thermal denaturation experiments, we confirmed that temperature profiles for increasing and decreasing the temperatures were identical within the experimental error range. For further details, see Supplementary Material.

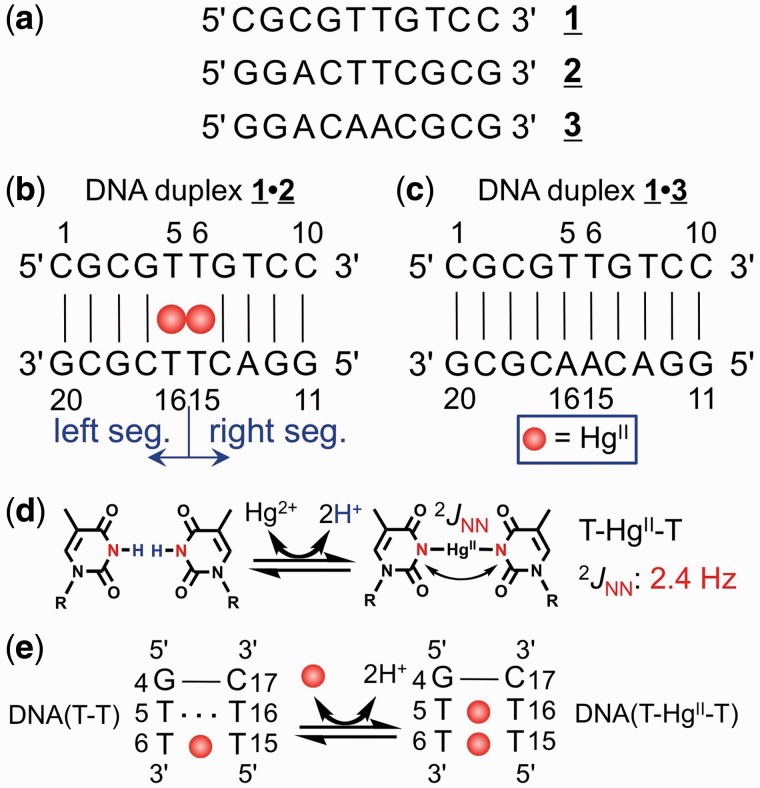

Figure 1.

The DNA sequences and the T–HgII–T base pair. (a) The DNA oligomers 1, 2 and 3. (B) The DNA duplex 1•2 with residue numbers. The definition of left and right segments is depicted. (c) The control DNA duplex 1•3 with residue numbers. (d) The reaction scheme for T–HgII–T base pair formation (the proton–HgII exchange reaction) and 2-bond 15N–15N J-coupling (2JNN) (23). (e) The schematic representation of the model used in ONIOM QM/QM calculation of thermodynamic parameters. The DNA(T–T) and DNA(T–HgII–T) stand for HgII-free and HgII-bound three base-paired (3 bp) duplex.

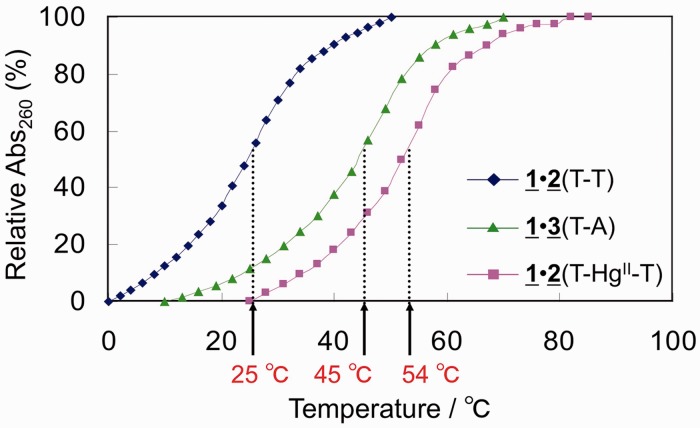

Figure 2.

The temperature profiles of UV absorbance at 260 nm. The vertical axis is a relative absorbance normalized between absorbances at the lowest and the highest temperatures. Blue diamonds: the DNA duplex 1•2 in the absence of HgII. Pink squares: the DNA duplex 1•2 in the presence of HgII. Green triangles: the DNA duplex 1•3. The Tm values for these profiles are given by the red characters with arrows.

NMR measurements and 3D structure determination

NMR spectra for the 1H resonance assignments and structure calculations were measured as described previously (23,39). By using the derived NMR spectra, we assigned all the non-exchangeable protons (39) and most of the exchangeable protons. The complete assignments are reported in Supplementary Table S1, and deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank with accession number 11 528. Resulting experimental constraints and other constraints for structure calculations are listed in Supplementary Table S2. The structural constraints for the T–HgII–T base pairs were generated based on the crystal structure of the 1-methylthymine–HgII (2:1) complex (37), i.e. N3–HgII bond length: 2.04Å and N3–HgII–N3-bond angle 180°.

Based on these structural constraints, the 3D structure of the DNA duplex with T–HgII–T pairs was calculated by simulated annealing, using the program X-PLOR ver 3.851 (40), based on previously reported protocols (41). From the calculations, 17 structures that satisfied the experimental constraints and covalent geometries were obtained out of 100 randomized structures (Supplementary Figure S3). Statistics for the converged structures are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Through the structure calculations, the N–HgII–N linkages of the T–HgII–T pairs were maintained. This is because the pairing partners of each T–HgII–T pair had already been determined in the same DNA sequence from the 2-bond 15N–15N J-coupling across HgII (2JNN) (23) (Figure 1d).

For further information on the NMR measurements and the structure calculation, see Supplementary Material. The structure is deposited in the Protein Data Bank with ID 2rt8.

ONIOM QM/QM calculations, structural modelling and geometry optimization

The structural model employed in the ONIOM QM/QM calculations (42); CAM-B3LYP(6-31G*, Stuttgart ECP for Hg):BP86(LANL2DZ) with GAUSSIAN 09 (43), was derived from the NMR structure of the DNA duplex 1•2, and is schematically depicted in Figure 1e (the G4–C17, T5–HgII–T16 and T6–HgII–T15 base pairs). The implicit water solvent was employed in all calculations. The geometry optimized structures for product and reactant adjusted from Equation (1) in Results and discussion section are depicted in Supplementary Figures S4 and S5. For the derivation of Equation (1), see Supplementary Material. In the reactant, hydrated HgII bound to the DNA(T–T) while in the DNA(T–HgII–T) product HgII was completely dehydrated. The overall helical structure of the models was ensured by relevant constraints adopted from the 3D structure of Figure 3; only the middle base pair was geometry optimized (see the legend to Supplementary Figures S4 and S5 for details). The ΔH, ΔS and ΔG were calculated for T = 298.15 K and standard pressure within the rigid-rotor harmonic-oscillator approximation, S was composed of translation, rotation and vibration contributions. For ONIOM QM/QM calculations, see also Supplementary Material.

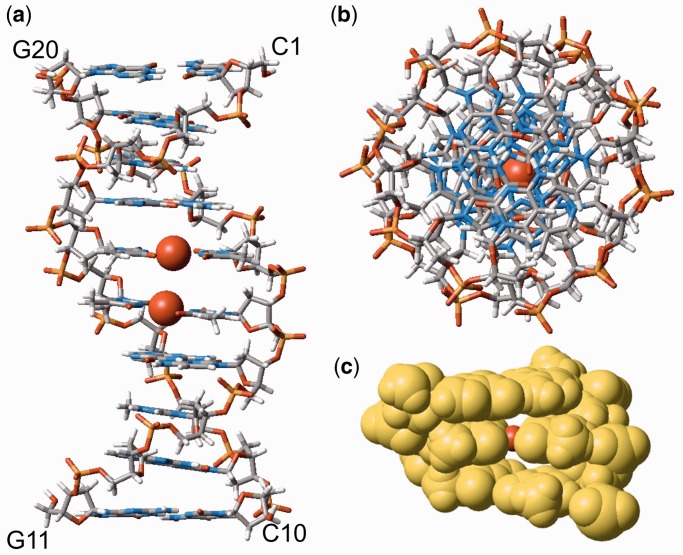

Figure 3.

The 3D structure of HgII-bound DNA duplex 1•2. (a) The side view perpendicular to helical axis. (b) The top view along helical axis. (c) The space-filling model of the middle 3-bp DNA segment including G4–C17, T5–HgII–T16 and T6–HgII–T15 pairs sketched out in Figure 1e. The Hg atoms are depicted always as red balls. The Hg–Hg distance derived solely with NOEs was ∼4 Å. When we applied the Hg–Hg distance constraint at 3.3 Å reflecting our X-ray diffraction analysis of a DNA duplex with tandem T–HgII–T base pairs (53) (Supplementary Figure S6 and Supplementary Material), the derived model structure of duplex 1•2 (Supplementary Figure S7) was consistent with the NOE constraints.

Preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of the DNA duplex and modelling of the DNA duplex 1•2 with an experimental Hg–Hg distance constraint

To obtain experimental HgII–HgII distance in a DNA duplex, a preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis was performed. For this purpose, the DNA dodecamer was co-crystallized with Hg(ClO4)2 by the hanging-drop vapour diffusion method at 4°C. Preliminary X-ray data collections were performed with synchrotron radiation (λ = 0.98Å) at BL17A in the Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan). Two HgII atoms were found at coordinates (x, y, z) = (1.1, 0.0, 7.2), (1.6, 0.9, 10.3) (Supplementary Figure S6) using the heavy-atom-search procedure of the program AutoSol from the Phenix suite (44–46). Then, the HgII–HgII distance was determined as 3.3Å which is also consistent with its theoretical values, 3.28–3.52Å (30). Based on these facts, the model structure of the DNA duplex with T–HgII–T pairs was also calculated by using rigid body minimizations and following normal energy minimizations under the HgII–HgII distance constraint (3.3Å). The derived model structure is shown in Supplementary Figure S7. For details on the preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis and the modelling studies, see Supplementary Material.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Thermal denaturation experiment

Two non-self-complementary DNA duplexes presented in Figure 1 were chemically synthesized. The thermal stabilities (Tm) of duplex 1•2 with T–T mismatches and T–HgII–T base pairs were evaluated and compared with that of reference duplex 1•3 containing W–C T–A base pairs (Figure 2).

The Tm value for duplex 1•2 increased from 25°C to 54°C upon adding HgII. Interestingly, the DNA duplex 1•2 with T–HgII–T pairs was more stable than its reference duplex 1•3 with W–C base pairs. The T–HgII–T base pair is therefore more stable than the W–C base pair in the sequence context of the DNA duplex 1•2. We also studied the effects of T–HgII–T nearest neighbour base pairs on Tm value (Supplementary Figure S1) and the highest stability was observed for the closely related sequence with the HgII-bound DNA duplex 1•2.

Structure determination

The DNA duplex 1•2 was selected for structure determination because: (i) the chemical structure of T–HgII–T was determined with 2JNN: 2-bond 15N–15N J-coupling across HgII-mediated linkage (Figure 1d) for the same sequence of DNA oligomer (23), and (ii) the closely related sequence was thermally most stable (Supplementary Figure S1). We then recorded NOESY spectra of HgII-bound DNA duplex 1•2 (39), and generated distance constraints from NOESY spectra published in the reference (39) (Supplementary Table S2).

In total, 17 structures that satisfied the NOE constraints were obtained (Supplementary Figure S3 and Table S2). All the derived structures were normal B-form duplexes (Supplementary Figure S3). The 3D structure of the duplex with the lowest energy is shown in Figure 3. The T–HgII–T pairs are well stacked without distorting the duplex, which indicates that they are accommodated into the DNA duplex in a similar manner to canonical W–C base pairs.

In addition, due to the local topology of the T–HgII–T pairs, their C1′–C1′ distances are shorter by ∼1Å than those found in W–C base pairs. Nonetheless, the difference was within the structural variation of B-form DNA duplexes. Therefore, the T–HgII–T pairs structurally mimic W–C base pairs without any significant perturbation of the double helix. This fact most likely explains why the DNA polymerase can incorporate thymine (T) against T in the template strand via the formation of T–HgII–T pair (47,48).

Closer look along the helical axis of DNA duplex 1•2 revealed perfectly aligned Hg atoms (Figure 3b). The space-filling model of the respective part of DNA duplex 1•2 further revealed that Hg atoms are shielded from bulk water (Figure 3c). The well-stacked metallo base pairs with the HgII–HgII distance at 4.03–4.17Å and narrow O4−O4/O2−O2 spacing exclude any possibility for bulk water to penetrate into proximity of Hg atoms. The relationship between 3D structure and the thermodynamic parameters will be discussed later.

Based on the 3D structure, we confirmed the theoretical prediction by Voityuk (49) and us (29) that overlap of their LUMOs of Hg atoms in the metallo-DNA is possible. This implies that the metallo-DNA duplex could be effective route for (an) excess electron(s). Furthermore, the well-stacked arrangement of T–HgII–T pairs suggests that interaction of Hg atoms is not repulsive, which supports existence of the Hg–Hg metallophilic attraction inside metallo-DNA. Recently, existence of the metallophillic attraction between heavy metals in metallo-DNAs was theoretically proposed for the AgI-mediated imidazole–imidazole base pairs (50) and the T–HgII–T pairs (30,31), and the 3D structure presented here is an additional indicative of such a newly proposed attractive force between heavy metals.

The relationship between 3D structure and the thermodynamic parameters

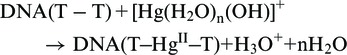

Next, we considered relationship between the 3D structure and the thermodynamic parameters for the T–HgII–T formation determined by Torigoe’s group (24,25), which showed positive ΔS and negative ΔH (Table 1). Based on the 3D structure, the reaction for T–HgII–T base pair formation can be written as follows. See also Supplementary Material for detailed derivation of Equation (1).

|

(1) |

where the DNA(T–T) and DNA(T–HgII–T) stand for DNA duplex with T–T mismatch and that with T–HgII–T pair, respectively (Figure 1e). In the Equation (1), we considered (i) the imino proton (H+)–HgII exchange reaction upon T–HgII–T base pair formation (Figure 1d); (ii) the dehydration of HgII cation during reaction; and (iii) the pKa = 3.4 for HgII–aqua complex (51) that implies existence of hydroxy-ligand of HgII.

Table 1.

Experimental and theoretical thermodynamic parameters

| ΔH°/kcal/mol | ΔS°/cal/mol/K | ΔG°/kcal/mol | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental (ITC)a | −3.85 ± 0.18 | 13.1 ± 0.65 | −7.76 ± 0.19 | (24) |

| −4.76 ± 0.13 | 10.6 ± 0.84 | −7.91 ± 0.12 | (24) | |

| Theoreticalb | −4.04 | 14.2 | −8.27 | This work |

aIn reference (25), thermodynamic parameters possessed much larger standard deviations. Therefore, only the precise data from reference (24) were shown in table. bCalculated values are based on Equation (1) (see Supplementary Figures S4 and S5, and Supplementary Methods). ΔG° values are given at 298.15 K.

Upon the HgII-binding to T–T mismatch, number of water molecules initially coordinated to HgII were released to bulk. Accordingly, the dehydration of HgII should yield the entropy increase following the thermodynamic assumptions. Such positive ΔS is known as dehydration entropy. However, the complete dehydration in this case has been only rarely validated experimentally. In summary, based on the 3D structure, one contributor to the ΔS was identified as dehydration entropy owing to the complete dehydration of HgII.

The 3D structure of HgII-bound DNA duplex 1•2 enabled calculation of the ΔS and ΔH with the ONIOM QM/QM method. Using the 3-bp DNA segment (Figures 1e and 3c) derived from the 3D structure of DNA duplex 1•2, the models of product (Supplementary Figure S4) and reactant (Supplementary Figure S5) were constructed following the Equation (1). Based on these structures, the thermodynamic parameters were calculated (Table 1). The calculated ΔH (−4.04 kcal/mol) and ΔS (14.2 cal/mol/K) agreed with the experiment (Table 1). From the result, not only the absolute values of ΔH and ΔS, but also the positive sign for ΔS was reproduced by theory. In addition, the calculated thermodynamic parameters in this work were consistent with those derived previously with different protocols for the complete reaction pathway describing formation of T–HgII–T base pair (52). The determined 3D structure rationally explained the thermodynamic parameters.

CONCLUSION

The first 3D structure of metallo-DNA composed exclusively of ‘NATURAL’ bases and containing tandem T–HgII–T base pairs was determined in solution. The positive ΔS recorded for T–HgII–T base pair formation was explained as HgII-dehydration entropy on the structural basis. The 3D structure rationally explained the specific HgII affinity toward T–T mismatch and unveiled the 3D arrangement of the metallo base pairs in the DNA duplex.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

PDB ID: 2rt8 BioMagResBank accession number: 11528

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan [grants-in-aid for Scientific Research (B) (24310163 to Y.T.) and (C) (18550146 to Y.T.)]; Human Frontier Science Program Organization, France (Human Frontier Science Program, young investigator grant to Y.T. and V.S.); GAČR (Czech Republic) [P205/10/0228 to V.S.]; Intelligent Cosmos Foundation (to Y.T.); Daiichi-Sankyo Foundation of Life Science and the Invitation Fellowship for Research in Japan (short-term) from the JSPS (to Y.T. and V.S.). Funding for open access charges: Grant-in-aid for Scientific Research (B) [24310163] from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Photon Factory (PF) for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities (Proposal No. 2011G630) and acknowledge the staff of beamline BL17A at the PF.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meggers E, Holland PL, Tolman WB, Romesberg FE, Schultz PG. A novel copper-mediated DNA base pair. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10714–10715. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atwell S, Meggers E, Spraggon G, Schultz PG. Structure of a copper-mediated base pair in DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:12364–12367. doi: 10.1021/ja011822e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meggers E. Exploring biologically relevant chemical space with metal complexes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2007;11:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schlegel MK, Essen L-O, Meggers E. Duplex structure of a minimal nucleic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8158–8159. doi: 10.1021/ja802788g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka K, Shionoya M. Synthesis of a novel nucleoside for alternative DNA base pairing through metal complexation. J. Org Chem. 1999;64:5002–5003. doi: 10.1021/jo990326u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weizman H, Tor Y. 2,2'-bipyridine ligandoside: A novel building block for modifying DNA with intra-duplex metal complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:3375–3376. doi: 10.1021/ja005785n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Switzer C, Sinha S, Kim PH, Heuberger BD. A purine-like nickel(II) base pair for DNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:1529–1532. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka K, Clever GH, Takezawa Y, Yamada Y, Kaul C, Shionoya M, Carell T. Programmable self-assembly of metal ions inside artificial DNA duplexes. Nat. Nanotech. 2006;1:190–195. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clever GH, Kaul C, Carell T. DNA-metal base pairs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:6226–6236. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Müller J. Metal-ion-mediated base pairs in nucleic acids. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2008:3749–3763. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johannsen S, Megger N, Böhme D, Sigel RKO, Müller J. Solution structure of a DNA double helix with consecutive metal-mediated base pairs. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:229–234. doi: 10.1038/nchem.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ono A, Torigoe H, Tanaka Y, Okamoto I. Binding of metal ions by pyrimidine base pairs in DNA duplexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:5855–5866. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15149e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka K, Tengeiji A, Kato T, Toyama N, Shionoya M. A discrete self-assembled metal array in artificial DNA. Science. 2003;299:1212–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1080587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clever GH, Reitmeier SJ, Carell T, Schiemann O. Antiferromagnetic Coupling of Stacked Cu(II)-Salen Complexes in DNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:4927–4929. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carell T, Behrens C, Gierlich J. Electrontransfer through DNA and metal-containing DNA. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003;1:2221–2228. doi: 10.1039/b303754a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito T, Nikaido G, Nishimoto SI. Effects of metal binding to mismatched base pairs on DNA-mediated charge transfer. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2007;101:1090–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joseph J, Schuster GB. Long-distance radical cation hopping in DNA: The effect of thymine-Hg(II)-thymine base pairs. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1843–1846. doi: 10.1021/ol070135a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo LQ, Yin N, Chen GN. Photoinduced electron transfer mediated by π-stacked thymine-Hg2+-thymine base pairs. J. Phy. Chem. C. 2011;115:4837–4842. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isobe H, Yamazaki N, Asano A, Fujino T, Nakanishi W, Seki S. Electron Mobility in a Mercury-mediated Duplex of Triazole-linked DNA ((TL)DNA) Chem. Lett. 2011;40:318–319. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ono A, Togashi H. Highly selective oligonucleotide-based sensor for Mercury(II) in aqueous solutions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:4300–4302. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ono A, Cao S, Togashi H, Tashiro M, Fujimoto T, Machinami T, Oda S, Miyake Y, Okamoto I, Tanaka Y. Specific interactions between silver(I) ions and cytosine-cytosine pairs in DNA duplexes. Chem. Commun. 2008:4825–4827. doi: 10.1039/b808686a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyake Y, Togashi H, Tashiro M, Yamaguchi H, Oda S, Kudo M, Tanaka Y, Kondo Y, Sawa R, Fujimoto T, et al. Mercury(II)-mediated formation of thymine-HgII-thymine base pairs in DNA duplexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2172–2173. doi: 10.1021/ja056354d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka Y, Oda S, Yamaguchi H, Kondo Y, Kojima C, Ono A. 15N-15N J-coupling across HgII: direct observation of HgII-mediated T-T base pairs in a DNA duplex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:244–245. doi: 10.1021/ja065552h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Torigoe H, Ono A, Kozasa T. HgII ion specifically binds with T:T mismatched base pair in duplex DNA. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:13218–13225. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torigoe H, Miyakawa Y, Ono A, Kozasa T. Positive cooperativity of the specific binding between Hg2+ ion and T:T mismatched base pairs in duplex DNA. Thermochim. Acta. 2012;532:28–35. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner DH, Sugimoto N, Freier SM. RNA structure prediction. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 1988;17:167–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.17.060188.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Starikov EB, Nordén B. Entropy–enthalpy compensation as a fundamental concept and analysis tool for systematical experimental data. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2012;538:118–120. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka Y, Ono A. Nitrogen-15 NMR spectroscopy of N-metallated nucleic acids: insights into 15N NMR parameters and N-metal bonds. Dalton Trans. 2008:4965–4974. doi: 10.1039/b803510p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchiyama T, Miura T, Takeuchi H, Dairaku T, Komuro T, Kawamura T, Kondo Y, Benda L, Sychrovský V, Bouř P, et al. Raman spectroscopic detection of the T–HgII–T base pair and the ionic characteristics of mercury. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5766–5774. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benda L, Straka M, Sychrovský V, Bouř P, Tanaka Y. Detection of mercury-TpT dinucleotide binding by Raman spectra: A computational study. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2012;116:8313–8320. doi: 10.1021/jp3045077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benda L, Straka M, Tanaka Y, Sychrovský V. On the role of mercury in the non-covalent stabilisation of consecutive U-Hg(II)-U metal-mediated nucleic acid base pairs: metallophilic attraction enters the world of nucleic acids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011;13:100–103. doi: 10.1039/c0cp01534b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young PR, Nandi US, Kallenbach NR. Binding of mercury(II) to poly(dA-dT) studied by proton nuclear magnetic-resonance. Biochemistry. 1982;21:62–66. doi: 10.1021/bi00530a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buncel E, Boone C, Joly H, Kumar R, Norris AR. Metal ion-biomolecule interactions .12. 1H AND 13C NMR evidence for the preferred reaction of thymidine over guanosine in exchange and competition reactions with mercury(II) and methylmercury(II) J. Inorg. Biochem. 1985;25:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuklenyik Z, Marzilli LG. Mercury(II) site-selective binding to a DNA hairpin. Relationship of sequence-dependent intra- and interstrand cross-linking to the hairpin-duplex conformational transition. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:5654–5662. doi: 10.1021/ic960260a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Onyido I, Norris AR, Buncel E. Biomolecule-mercury interactions: modalities of DNA base-mercury binding mechanisms. Remediation strategies. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:5911–5929. doi: 10.1021/cr030443w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johannsen S, Paulus S, Düpre N, Müller J, Sigel RKO. Using in vitro transcription to construct scaffolds for one-dimensional arrays of mercuric ions. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102:1141–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kosturko LD, Folzer C, Stewart RF. Crystal and molecular-structure of a 2:1 complex of 1-methylthymine-mercury(II) Biochemistry. 1974;13:3949–3952. doi: 10.1021/bi00716a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puglisi JD, Tinoco I., Jr Absorbance melting curves of RNA. Methods Enzymol. 1989;180:304–325. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(89)80108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanaka Y, Yamaguchi H, Oda S, Nomura M, Kojima C, Kondo Y, Ono A. NMR spectroscopic study of a DNA duplex with mercury-mediated T-T base pairs. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2006;25:613–624. doi: 10.1080/15257770600686154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brünger AT. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1992. X-PLOR, version 3.1 manual. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka Y, Kojima C, Yamazaki T, Kodama TS, Yasuno K, Miyashita S, Ono AM, Ono A, Kainosho M, Kyogoku Y. Solution structure of an RNA duplex including a C-U base-pair. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7074–7080. doi: 10.1021/bi000018m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Svensson M, Humbel S, Froese RDJ, Matsubara T, Sieber S, Morokuma K. ONIOM: a multilayered integrated MO+MM method for geometry optimizations and single point energy predictions. A test for Diels-Alder reactions and Pt(P(t-Bu)3)2+H2 oxidative addition. J. Phys. Chem. 1996;100:19357–19363. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Montgomery JA, Jr, Vreven T, Kudin KN, Burant JC, et al. 2009 Gaussian 09, Revision A.02. Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. Substructure search procedures for macromolecular structures. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2003;59:1966–1973. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903018043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terwilliger TC, Adams PD, Read RJ, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Afonine PV, Zwart PH, Hung LW. Decision-making in structure solution using Bayesian estimates of map quality: the PHENIX AutoSol wizard. Acta Crystallogr. D. 2009;65:582–601. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909012098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Urata H, Yamaguchi E, Funai T, Matsumura Y, Wada S. Incorporation of thymine nucleotides by DNA polymerases through T-HgII-T base pairing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:6516–6519. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park KS, Jung C, Park HG. ‘Illusionary’ polymerase activity triggered by metal ions: use for molecular logic-gate operations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:9757–9760. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voityuk AA. Electronic coupling mediated by stacked [Thymine-Hg-Thymine] base pairs. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:21010–21013. doi: 10.1021/jp062776d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumbhar S, Johannsen S, Sigel RKO, Waller MP, Müller J. A QM/MM refinement of an experimental DNA structure with metal-mediated base pairs. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013;127:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sjoberg S. Metal-complexes with mixed-ligands. 11. Formation of ternary mononuclear and polynuclear mercury(II) complexes in system Hg2+-Cl−OH−. A potentiometric study in 3.0 M NaClO4, Cl media. Acta Chem. Scan. A. 1977;31:705–717. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Šebera J, Burda J, Straka M, Ono A, Kojima C, Tanaka Y, Sychrovský V. Formation of the T–HgII–T metal-mediated DNA base pair: proposal and theoretical calculation of the reaction pathway. Chem. Eur. J. 2013;19:9884–9894. doi: 10.1002/chem.201300460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kondo J, Yamada T, Hirose C, Okamoto I, Tanaka Y, Ono A. Crystal structure of metallo-DNA duplex containing consecutive Watson-Crick-like T–HgII–T base pairs. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:2385–2388. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.