Abstract

The problem of heat conduction in one-dimensional piecewise homogeneous composite materials is examined by providing an explicit solution of the one-dimensional heat equation in each domain. The location of the interfaces is known, but neither temperature nor heat flux is prescribed there. Instead, the physical assumptions of their continuity at the interfaces are the only conditions imposed. The problem of two semi-infinite domains and that of two finite-sized domains are examined in detail. We indicate also how to extend the solution method to the setting of one finite-sized domain surrounded on both sides by semi-infinite domains, and on that of three finite-sized domains.

Keywords: heat equation, interface problem, non-steady-state heat conduction, composite walls, Fokas method

1. Introduction

The problem of heat conduction in a composite wall is a classical problem in design and construction. It is usual to restrict to the case of walls whose constitutive parts are in perfect thermal contact and have physical properties that are constant throughout the material and that are considered to be of infinite extent in the directions parallel to the wall. Further, we assume that temperature and heat flux do not vary in these directions. In that case, the mathematical model for heat conduction in each wall layer is given by [1, ch. 10]

| 1.1a |

and

| 1.1b |

where u(j)(x,t) denotes the temperature in the wall layer indexed by (j), κj>0 is the heat-conduction coefficient of the jth layer (the inverse of its thermal diffusivity), x=aj is the left extent of the layer and x=bj is its right extent. The sub-indices denote derivatives with respect to the one-dimensional spatial variable x and the temporal variable t. The function  is the prescribed initial condition of the system. The continuity of the temperature u(j) and of its associated heat flux

is the prescribed initial condition of the system. The continuity of the temperature u(j) and of its associated heat flux  are imposed across the interface between layers. In what follows, it is convenient to use the quantity σj, defined as the positive square root of κj:

are imposed across the interface between layers. In what follows, it is convenient to use the quantity σj, defined as the positive square root of κj:  .

.

If the layer is either at the far left or far right of the wall, Dirichlet, Neumann, or Robin boundary conditions can be imposed on its far left or right boundary, respectively, corresponding to prescribing ‘outside’ temperature, heat flux or a combination of these. A derivation of the interface boundary conditions is found in [1, ch. 1]. It should be noted that the set-up presented in (1.1a) also applies to the case of one-dimensional rods in thermal contact.

In this paper, we use the Fokas method [2–4] to provide explicit solution formulae for different heat transport interface problems of the type described above. We investigate problems in both finite and infinite domains, and we compare our method with classical solution approaches that can be found in the literature. Throughout, our emphasis is on non-steady-state solutions. Even for the simplest of the problems we consider (§3, two finite walls in thermal contact), the classical approach using separation of variables [1] can provide an explicit answer only implicitly. Indeed, the solution obtained in [1] depends on certain eigenvalues defined through a transcendental equation that can be solved only numerically. By contrast, the Fokas method produces an explicit solution formula involving only known quantities. For other problems we consider, to our knowledge no solution has been derived using classical methods and we believe the solution formulae presented here are new.

The representation formulae for the solution can be evaluated numerically, hence the problem can be solved in practice using hybrid analytical–numerical approaches [5] or asymptotic approximations for them may be obtained using standard techniques [3]. The result of such a numerical calculation is shown at the end of §2.

The problem of heat conduction through composite walls is discussed in many excellent texts (see for instance [1,6]). References to the treatment of specific problems are given in the sections below where these problems are investigated. In §2, we investigate the problem of two semi-infinite walls. Section 3 discusses the interface problem with two finite walls. Following that, we consider first the problem of one finite wall between two semi-infinite ones and the problem of three finite walls. Both of them are briefly sketched in §4 and full solutions are presented in the electronic supplementary material.

2. Two semi-infinite domains

In this section, we consider the problem of heat flow through two walls of semi-infinite width or of two semi-infinite rods.

We seek two functions:

satisfying the equations

| 2.1a |

and

| 2.1b |

with the initial conditions being

| 2.2a |

and

| 2.2b |

the asymptotic conditions being

| 2.3a |

and

| 2.3b |

and the continuity interface conditions being

| 2.4a |

and

| 2.4b |

The sub- and super-indices L and R denote the left and right rods, respectively. A special case of this problem is discussed in [1, ch. 10], but only for a specific initial condition. Further, for the problem treated there, both  and

and  , are assumed to be zero. This assumption is made for mathematical convenience and no physical reason exists to impose it. If constant (in time) limit values are assumed, a simple translation allows one of the limit values to be equated to zero, but not both. As no great advantage is obtained by assuming a zero limit using our approach, we make the more general assumption (2.3).

, are assumed to be zero. This assumption is made for mathematical convenience and no physical reason exists to impose it. If constant (in time) limit values are assumed, a simple translation allows one of the limit values to be equated to zero, but not both. As no great advantage is obtained by assuming a zero limit using our approach, we make the more general assumption (2.3).

We define vL(x,t)=uL(x,t)−γL and vR(x,t)=uR(x,t)−γR. Then, vL(x,t) and vR(x,t) satisfy

| 2.5a |

| 2.5b |

| 2.5c |

| 2.5d |

| 2.5e |

and

| 2.5f |

At this point, we start by following the standard steps in the application of the Fokas method [2–4]. We begin with the so-called ‘local relations’ [2]

| 2.6a |

and

| 2.6b |

These relations are a one-parameter family obtained by rewriting (2.5a,b).

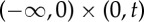

Applying Green’s formula [7] in the strip  in the left-half plane (figure 1), we find

in the left-half plane (figure 1), we find

|

2.7 |

Figure 1.

Domains for the application of Green’s formula for vL(x,t) and vR(x,t). (Online version in colour.)

Let  . Similarly, let

. Similarly, let  . As |x| can become arbitrarily large, we require

. As |x| can become arbitrarily large, we require  in (2.7) in order to guarantee that the first two integrals are well defined. Let

in (2.7) in order to guarantee that the first two integrals are well defined. Let  . The region D is shown in figure 2.

. The region D is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

The domains D+ and D− for the heat equation. (Online version in colour.)

For  , we define the following transforms:

, we define the following transforms:

|

Using these definitions, the global relation (2.7) is rewritten as

| 2.8 |

As the dispersion relation ωL(k)=(σLk)2 is invariant under k→−k, so are g0((σLk)2,t) and g1((σLk)2,t). Thus, we can supplement (2.8) with its evaluation at −k, namely

| 2.9 |

This relation is valid on  . Using Green’s formula on

. Using Green’s formula on  (figure 1), the global relation for vR(x,t) is

(figure 1), the global relation for vR(x,t) is

|

2.10 |

valid in  .

.

As above, using the invariance of ωR(k)=(σRk)2, g0((σRk)2,t) and g1((σRk)2,t) under k→−k, we supplement (2.10) with

|

2.11 |

for  .

.

Inverting the Fourier transforms in (2.8), we have

|

2.12 |

for  and t>0. The integrand of the second integral in (2.12) is entire and decays as

and t>0. The integrand of the second integral in (2.12) is entire and decays as  for

for  . Using the analyticity of the integrand and applying Jordan’s lemma [7], we can replace the contour of integration of the second integral by

. Using the analyticity of the integrand and applying Jordan’s lemma [7], we can replace the contour of integration of the second integral by  :

:

|

2.13 |

Proceeding similarly on the right, starting from (2.10), we have

|

2.14 |

for  and t>0. Here, erf(⋅) denotes the error function:

and t>0. Here, erf(⋅) denotes the error function:  . To obtain the second equality above, we integrated the terms that are explicit.

. To obtain the second equality above, we integrated the terms that are explicit.

Expressions (2.13) and (2.14) for vL(x,t) and vR(x,t) depend on the unknown functions g0 and g1, evaluated at different arguments. These functions need to be expressed in terms of known quantities. To obtain a system of two equations for the two unknown functions, we use (2.9) and (2.10) for g0((σLk)2,t) and g1((σLk)2,t). This requires the transformation k→−σLk/σR in (2.10). The − sign is required to ensure that both equations are valid on  , allowing for their simultaneous solution. We find

, allowing for their simultaneous solution. We find

|

2.15 |

and

|

2.16 |

valid for  . These expressions are substituted into (2.13) and (2.14). This results in expressions for vL(x,t) and vR(x,t) that appear to depend on vL and vR themselves. We examine the contribution of the terms involving

. These expressions are substituted into (2.13) and (2.14). This results in expressions for vL(x,t) and vR(x,t) that appear to depend on vL and vR themselves. We examine the contribution of the terms involving  and

and  . Starting with (2.13), we obtain for vL(x,t) the following expression:

. Starting with (2.13), we obtain for vL(x,t) the following expression:

|

2.17 |

for  , t>0. The first four terms depend only on known functions. To examine the second-to-last term, we note that the integrand is analytic for all

, t>0. The first four terms depend only on known functions. To examine the second-to-last term, we note that the integrand is analytic for all  and that

and that  decays for

decays for  for

for  . Thus, by Jordan’s lemma, the integral of

. Thus, by Jordan’s lemma, the integral of  along a closed, bounded curve in

along a closed, bounded curve in  vanishes. In particular, we consider the closed curve

vanishes. In particular, we consider the closed curve  , where

, where  and

and  (figure 3).

(figure 3).

Figure 3.

The contour  is shown as a dashed line. An application of Cauchy’s integral theorem [7] using this contour allows the elimination of the contribution of

is shown as a dashed line. An application of Cauchy’s integral theorem [7] using this contour allows the elimination of the contribution of  from integral expression (2.17). Similarly, the contour

from integral expression (2.17). Similarly, the contour  is shown as a solid line and application of Cauchy’s integral theorem using this contour allows the elimination of the contribution of

is shown as a solid line and application of Cauchy’s integral theorem using this contour allows the elimination of the contribution of  from integral expression (2.19). (Online version in colour.)

from integral expression (2.19). (Online version in colour.)

As the integral along  vanishes for large C, the fourth integral on the right-hand side of (2.17) must vanish as the contour

vanishes for large C, the fourth integral on the right-hand side of (2.17) must vanish as the contour  becomes ∂D− as

becomes ∂D− as  . The uniform decay of

. The uniform decay of  for large k is exactly the condition required for the integral to vanish, using Jordan’s lemma. For the final integral in equation (2.17), we use the fact that

for large k is exactly the condition required for the integral to vanish, using Jordan’s lemma. For the final integral in equation (2.17), we use the fact that  is analytic and bounded for

is analytic and bounded for  . Using the same argument as above, the fifth integral in (2.17) vanishes and we have an explicit representation for vL(x,t) in terms of initial conditions

. Using the same argument as above, the fifth integral in (2.17) vanishes and we have an explicit representation for vL(x,t) in terms of initial conditions

|

2.18 |

To find an explicit expression for vR(x,t), we need to evaluate g0 and g1 at different arguments, also ensuring that the expressions are valid for  . From (2.15) and (2.16), we find

. From (2.15) and (2.16), we find

|

and

|

Substituting these into equation (2.14), we obtain

|

2.19 |

for  , t>0. As before, everything about the first three integrals is known. To compute the fourth integral, we proceed as we did before for vL(x,t) and eliminate integrals that decay in the regions over which we are integrating. The final solution is

, t>0. As before, everything about the first three integrals is known. To compute the fourth integral, we proceed as we did before for vL(x,t) and eliminate integrals that decay in the regions over which we are integrating. The final solution is

|

2.20 |

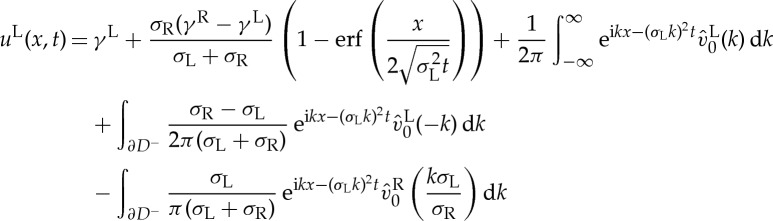

Returning to the original variables, we have the following proposition which determines uR and uL fully explicitly in terms of the given initial conditions and the prescribed boundary conditions as  .

.

Proposition 2.1 —

The solution of the heat transfer problem (2.1)–(2.4) is given by

2.21a and

2.21b

Remarks.

— The use of the discrete symmetries of the dispersion relation is an important aspect of the Fokas method [2–4]. When solving the heat equation in a single medium, the only discrete symmetry required is k→−k, which was used here as well to obtain (2.9) and (2.11). Owing to the two media, there are two dispersion relations in this problem: ω1=(σLk)2 and ω2=(σRk)2. The collection of both dispersion relations {ω1,ω2} retains the discrete symmetry k→−k but admits two additional ones, namely: k→(σR/σL)k and k→(σL/σR)k, which transform the two dispersion relations to each other. All non-trivial discrete symmetries of {ω1,ω2} are needed to derive the final solution representation, and indeed they are used, for example, to obtain relations (2.15) and (2.16).

— With σL=σR and γL=γR=0, solution formulae (2.21) in their proper x-domain of definition reduce to the solution of the whole line problem as given in [3].

— Classical approaches to the problem presented in this section can be found in the literature, for the case γL=0=γR. For instance, for one special pair of initial conditions, a solution is presented in [1]. No explicit solution formulae using classical methods with general initial conditions exist to our knowledge. At best, one is left with having to find the solution of an equation involving inverse Laplace transforms, where the unknowns are embedded within these inverse transforms.

— The steady-state solution to (2.1) with initial conditions, which decay sufficiently fast to the boundary values (2.3) at

, is easily obtained by letting

, is easily obtained by letting  in (2.21). This gives

in (2.21). This gives  . This is the weighted average of the boundary conditions at infinity with weights given by σL and σR. To our knowledge, this is a new result. It is consistent with the steady-state limit (γL+γR)/2 for the whole-line problem with initial conditions that limit to different values γL and γR as

. This is the weighted average of the boundary conditions at infinity with weights given by σL and σR. To our knowledge, this is a new result. It is consistent with the steady-state limit (γL+γR)/2 for the whole-line problem with initial conditions that limit to different values γL and γR as  . This result is easily obtained from the solution of the heat equation defined on the whole line using the Fokas method, but it can also be observed by employing piecewise-constant initial data in the classical Green’s function solution, as described in Theorem 4-1 on p. 171 (and comments thereafter) of [8]. It should be emphasized that the steady-state problem for (2.1)–(2.4) or even for the heat equation defined on the whole line with different boundary conditions at

. This result is easily obtained from the solution of the heat equation defined on the whole line using the Fokas method, but it can also be observed by employing piecewise-constant initial data in the classical Green’s function solution, as described in Theorem 4-1 on p. 171 (and comments thereafter) of [8]. It should be emphasized that the steady-state problem for (2.1)–(2.4) or even for the heat equation defined on the whole line with different boundary conditions at  and

and  is ill posed in the sense that the steady solution cannot satisfy the boundary conditions.

is ill posed in the sense that the steady solution cannot satisfy the boundary conditions.

Using a slight variation on the method presented in [5], one can compute solutions (2.21) numerically with specified initial conditions. We plot solutions for the case of vanishing boundary conditions (γL=γR=0) with

and

with αL=25 and αR=30 (figure 4). The Fourier transforms of these initial conditions may be computed explicitly. We choose σL=0.02 and σR=0.06. The initial conditions are chosen so as to satisfy interface boundary conditions (2.4) at t=0. The results clearly illustrate the discontinuity in the first derivative of the temperature at the interface x=0.

Figure 4.

Results for solutions (2.18) and (2.20) with  , uR0(x)= x2 e−(30)2x and σL=0.02, σR=0.06, γL=γR=0, t∈[0,0.02] using the hybrid analytical–numerical method of [5]. (Online version in colour.)

, uR0(x)= x2 e−(30)2x and σL=0.02, σR=0.06, γL=γR=0, t∈[0,0.02] using the hybrid analytical–numerical method of [5]. (Online version in colour.)

3. Two finite domains

Next, we consider the problem of heat conduction through two walls of finite width (or of two finite rods) with Robin boundary conditions. We seek two functions:

satisfying the equations

| 3.1a |

and

| 3.1b |

the initial conditions

| 3.2a |

and

| 3.2b |

the boundary conditions

| 3.3a |

and

| 3.3b |

and the continuity conditions

| 3.4a |

and

| 3.4b |

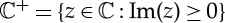

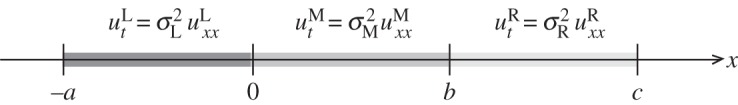

as illustrated in figure 5, where a>0, b>0 and αi, 1≤i≤4 constant.

Figure 5.

The heat equation for two finite rods.

If α1=α3=0, then Neumann boundary conditions are prescribed, whereas if α2=α4=0 then Dirichlet conditions are given.

As before, we have the local relations

| 3.5a |

and

| 3.5b |

We define the time transforms of the initial and boundary data and the spatial transforms of u for  as follows:

as follows:

|

Using Green’s theorem on the domains [−a,0]×[0,t] and [0,b]×[0,t], respectively, we have the global relations

|

3.6a |

and

|

3.6b |

Both equations are valid for all  , in contrast to (2.8) and (2.10). Using the invariance of ωL(k)=(σLk)2 and ωR(k)=(σRk)2 under k→−k, we obtain

, in contrast to (2.8) and (2.10). Using the invariance of ωL(k)=(σLk)2 and ωR(k)=(σRk)2 under k→−k, we obtain

|

3.7a |

and

|

3.7b |

Inverting the Fourier transform in (3.6a),

|

3.8 |

The integrand of the first integral is entire and decays as  for

for  . The second integral has an integrand that is entire and decays as

. The second integral has an integrand that is entire and decays as  for

for  . It is convenient to deform both contours away from k=0 to avoid singularities in the integrands that become apparent in what follows. Initially, these singularities are removable, as the integrands are entire. Writing integrals of sums as sums of integrals, the singularities may cease to be removable. With the deformations away from k=0, the apparent singularities are no cause for concern. In other words, we deform D+ to D+0 and D− to D−0 as shown in figure 6. Thus,

. It is convenient to deform both contours away from k=0 to avoid singularities in the integrands that become apparent in what follows. Initially, these singularities are removable, as the integrands are entire. Writing integrals of sums as sums of integrals, the singularities may cease to be removable. With the deformations away from k=0, the apparent singularities are no cause for concern. In other words, we deform D+ to D+0 and D− to D−0 as shown in figure 6. Thus,

|

3.9 |

Figure 6.

Deformation of the contours in figure 2 away from k=0. (Online version in colour.)

To obtain the solution on the right, we apply the inverse Fourier transform to (3.6b)

|

3.10 |

The integrand of the first integral is entire and decays as  for

for  . The second integral has an integrand that is entire and decays as

. The second integral has an integrand that is entire and decays as  for

for  . We deform the contours as above to obtain

. We deform the contours as above to obtain

|

3.11 |

Taking the time transform of the boundary conditions results in  and

and

These two equations together with (3.7a,b) are four equations to be solved for the four unknowns  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . The resulting expressions are substituted in (3.9) and (3.11).

. The resulting expressions are substituted in (3.9) and (3.11).

Although we could solve this problem in its full generality, we restrict to the case of Dirichlet boundary conditions (α2=α4=0), to simplify the already cumbersome formulae below. Then,  and

and  are determined and we solve two equations for two unknowns. System (3.7a,b) is not solvable for

are determined and we solve two equations for two unknowns. System (3.7a,b) is not solvable for  and

and  if ΔL(k)=0, where

if ΔL(k)=0, where

|

It is easily seen that all values of k satisfying this (including k=0) are on the real line. Thus on the contours, the equations are solved without problem, resulting in the expressions below. As before, the right-hand sides of these expressions involve  and

and  , evaluated at a variety of arguments. All terms with such dependence are written out explicitly below. Terms that depend on only known quantities are contained in KL and KR, the expressions for which are given later.

, evaluated at a variety of arguments. All terms with such dependence are written out explicitly below. Terms that depend on only known quantities are contained in KL and KR, the expressions for which are given later.

|

3.12 |

and

|

3.13 |

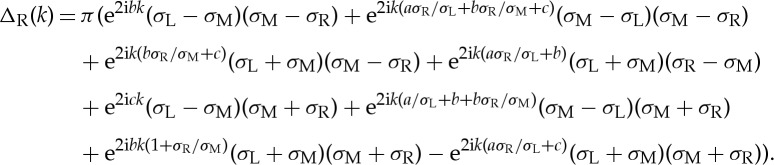

where ΔR(k)=ΔL(kσR/σL). The integrands written explicitly in (3.12) and (3.13) decay in the regions around whose boundaries they are integrated. Thus, using Jordan’s lemma and Cauchy’s theorem, these integrals are shown to vanish. Thus, the final solution is given by KL and KR.

Proposition 3.1 —

The solution of heat transfer problem (3.1)–(3.4) is given by

3.14 for −a<x<0, and for 0<x<b

3.15

Remarks.

— The solution of the problem posed in (3.1)–(3.4) may be obtained using the classical method of separation of variables and superposition [1]. The solutions uL(x,t) and uR(x,t) are given by a series of eigenfunctions with eigenvalues that satisfy a transcendental equation, closely related to the equation ΔL(k)=0. This series solution may be obtained from proposition 3.1 by deforming the contours along

and

and  to the real line, including small semicircles around each root of either ΔL(k) or ΔR(k), depending on whether uL(x,t) or uR(x,t) is being calculated. Indeed, this is allowed because all integrands decay in the wedges between these contours and the real line, and the zeros of ΔL(k) and ΔR(k) occur only on the real line, as stated above. Careful calculation of all different contributions, following the examples in [2,3], shows that the contributions along the real line cancel, leaving only residue contributions from the small circles. Each residue contribution corresponds to a term in the classical series solution. It is not necessarily beneficial to leave the form of the solution in proposition 3.1 for the series representation, as the latter depends on the roots of ΔL(k) and ΔR(k), which are not known explicitly. By contrast, the representation of proposition 3.1 depends on known quantities only and may be readily computed, using one’s favourite parameterization of the contours

to the real line, including small semicircles around each root of either ΔL(k) or ΔR(k), depending on whether uL(x,t) or uR(x,t) is being calculated. Indeed, this is allowed because all integrands decay in the wedges between these contours and the real line, and the zeros of ΔL(k) and ΔR(k) occur only on the real line, as stated above. Careful calculation of all different contributions, following the examples in [2,3], shows that the contributions along the real line cancel, leaving only residue contributions from the small circles. Each residue contribution corresponds to a term in the classical series solution. It is not necessarily beneficial to leave the form of the solution in proposition 3.1 for the series representation, as the latter depends on the roots of ΔL(k) and ΔR(k), which are not known explicitly. By contrast, the representation of proposition 3.1 depends on known quantities only and may be readily computed, using one’s favourite parameterization of the contours  and

and  .

.- — Similarly, the familiar piecewise linear steady-state solution of (3.1)–(3.4) with Dirichlet boundary conditions [1] can be observed from (3.14) and (3.15) by choosing initial conditions that decay appropriately and constant boundary conditions fL(t)=γL and fR(t)=γR. It is convenient to choose zero initial conditions, as the initial conditions do not affect the steady state. As above, the contours are deformed so that they are along the real line with semicircular paths around the zeros of ΔL(k) and ΔR(k), including k=0. As one of these deformations arises from

while the other comes from

while the other comes from  , the contributions along the real line cancel each other, while the semicircles add to give full residue contributions from the poles associated with the zeros of ΔL(k). All such residues vanish as

, the contributions along the real line cancel each other, while the semicircles add to give full residue contributions from the poles associated with the zeros of ΔL(k). All such residues vanish as  , except at k=0. It follows that the steady-state behaviour is determined by the residue at the origin. This results in

, except at k=0. It follows that the steady-state behaviour is determined by the residue at the origin. This results in

and

which is piecewise linear and continuous.

- — A more direct way to recover only the steady-state solution to (3.1) with

and

and  constant is to write the solution as the superposition of two parts:

constant is to write the solution as the superposition of two parts:  and

and  . The first parts

. The first parts  and

and  satisfy the boundary conditions as

satisfy the boundary conditions as  and the stationary heat equation. In other words,

and the stationary heat equation. In other words,

A piecewise linear ansatz with the imposition of the interface conditions results in linear algebra for the unknown coefficients [1]. With the steady-state solution in hand, the second (time-dependent) parts

and

and  satisfy the initial conditions modified by the steady-state solution and the boundary conditions minus their value as

satisfy the initial conditions modified by the steady-state solution and the boundary conditions minus their value as

where, as usual, we impose continuity of temperature and heat flux at the interface x=0. The dynamics of the solution is described by

and

and  , both of which decay to zero as

, both of which decay to zero as  . Their explicit form is easily found using the method described in this section.

. Their explicit form is easily found using the method described in this section.

4. Other problems

With the basic principles of the method outlined in the previous two sections, problems with more layers, both finite and infinite, may be addressed. We state two additional problems below and include solutions for specific initial conditions. More complete solutions can be found in the electronic supplementary material.

(a). Infinite domain with three layers

In this section, we consider the heat equation defined on two semi-infinite rods enclosing a single rod of length 2a.

We seek three functions:

with t≥0, satisfying the equations

| 4.1a |

| 4.1b |

and

| 4.1c |

with the initial conditions being

| 4.2a |

| 4.2b |

and

| 4.2c |

the asymptotic conditions being

| 4.3a |

and

| 4.3b |

and the continuity conditions being

| 4.4a |

| 4.4b |

| 4.4c |

and

| 4.4d |

as shown in figure 7.

Figure 7.

The heat conduction problem for a single rod of length 2a between two semi-infinite rods.

Asymptotic conditions (4.3) are not the most general possible but are used here to simplify calculations. To our knowledge, no aspect of this problem is addressed in the literature.

To solve this problem, one would proceed with the following steps:

(i) Write the local relations in each of the three domains: left, middle and right.

(ii) Use Green’s theorem to define the three global relations, keeping track of where they are valid in the complex k plane.

(iii) Solve the three global relations for uL(x,t), uM(x,t) and uR(x,t) by inverting the Fourier transforms.

(iv) Using the k→−k symmetry of the dispersion relationships on the three original global relations, write down three more global relations. This uses the discrete symmetry of each individual dispersion relation.

(v) Deform the integrals of the solution expressions to

or

or  as dictated by the region of analyticity of the integrand.

as dictated by the region of analyticity of the integrand.(vi) Use the discrete symmetries of the dispersion relationship to the collection of global relations for g0(ω,t), g1(ω,t), h0(ω,t) and h1(ω,t). Care should be taken that relations can only be solved simultaneously provided their regions of validity overlap. At this stage, as in the previous two sections, the discrete symmetries from one dispersion relation to another come into play.

(vii) Terms containing unknown functions are shown to be zero by examining the regions of analyticity and decay for the relevant integrands and the use of Jordan’s lemma.

For brevity of the presentation, we will assume that uM(x,0)=0=uR(x,0). The solution to the non-restricted problem can be found in the electronic supplementary material. After defining the transforms

|

we proceed as outlined above. The solution formulae are given in the following proposition:

Proposition 4.1 —

The solution of the heat transfer problem (4.1)–(4.4) with uM(x,0)=uR(x,0)=0 is

for

with ΔL(k)=π((σL−σM)(σM−σR)+e4iakσL/σM(σL+σM)(σM+σR)),

for −a<x<b with ΔR(k)=π((σL+σM)(σM+σR)+e4iakσR/σM(σL−σM)(σM−σR)). Lastly, the expression for uR(x,t), valid for x>a, is

(b). Finite domain with three layers

We consider the heat conduction problem in three rods of finite length as shown in figure 8.

Figure 8.

The heat equation for three finite layers.

We seek three functions:

satisfying the equations

| 4.5a |

| 4.5b |

and

| 4.5c |

with the initial conditions being

| 4.6a |

| 4.6b |

and

| 4.6c |

the boundary conditions being

| 4.7a |

and

| 4.7b |

and the continuity conditions being

| 4.8a |

| 4.8b |

| 4.8c |

and

| 4.8d |

The solution process is as before, following the steps outlined in the previous section. For simplicity, we assume Neumann boundary data (α1=α3=0), zero boundary conditions (fL(t)=fR(t)=0) and uM(x,0)=0=uR(x,0). The solution with uM(x,0)≠0 and uR(x,0)≠0 is given in the electronic supplementary material. We define

|

The solution is given by the following proposition:

Proposition 4.2 —

The solution to the heat transfer problem (4.5)–(4.8) with α1=α3=0, fL(t)=fR(t)=0 and uM(x,0)=uR(x,0)=0 is

for −a<x<0 with

Next,

for 0<x<b, with

and

for b<x<c with

Acknowledgements

Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding sources. We thank the American Institute for Mathematics (AIM, Palo Alto, CA, USA) for its hospitality, while some of this work was being conducted.

Funding statement

This work was generously supported by the National Science Foundation under grant no. NSF-DMS-1008001 (B.D., N.E.S.). N.E.S. also acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation under grant no. NSF-DGE-0718124.

References

- 1.Hahn D, Özisik M. 2012. Heat conduction Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 3rd edn. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deconinck B, Trogdon T, Vasan V. 2014. The method of Fokas for solving linear partial differential equations. SIAM Rev. 56, 159–186 (doi:10.1137/110821871) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fokas AS. 2008. A unified approach to boundary value problems. CBMS-NSF Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics, vol. 78 Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fokas AS, Pelloni B. 2005. A transform method for linear evolution PDEs on a finite interval. IMA J. Appl. Math. 70, 564–587 (doi:10.1093/imamat/hxh047) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flyer N, Fokas AS. 2008. A hybrid analytical-numerical method for solving evolution partial differential equations. I. The half-line. Proc. R. Soc. A 464, 1823–1849 (doi:10.1098/rspa.2008.0041) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carslaw HS, Jaeger JC. 1959. Conduction of heat in solids, 2nd edn. New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ablowitz MJ, Fokas AS. 2003. Complex variables: introduction and applications, 2nd edn, Cambridge Texts in Applied Mathematics Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guenther RB, Lee JW. 1996. Partial differential equations of mathematical physics and integral equations. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications Inc. (Corrected reprint of the 1988 original.) [Google Scholar]