Abstract

Sound sequences such as music are usually organized perceptually into concurrent “streams.” The mechanisms underlying this “auditory streaming” phenomenon are not completely known. The present study sought to test the hypothesis that synchrony limits listeners' ability to separate sound streams. To this aim, both perceptual-organization judgments and performance measures were used. In experiment 1, listeners indicated whether they perceived sequences of alternating or synchronous tones as a single stream or as two streams. In experiments 2 and 3, listeners detected rare changes in the intensity of “target” tones at one frequency in the presence of synchronous or asynchronous random-intensity “distractor” tones at another frequency. The results of these experiments showed that, for large frequency separations between the tones, the probability of perceiving two streams was lower on average for synchronous than for alternating tones, and that sensitivity to intensity changes in the target sequence was greater for asynchronous than for synchronous distractors. Overall, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that synchrony limits listeners' ability to form separate streams and/or to attend selectively to certain sounds in the presence of other sounds, even when the target and distractor sounds are well separated from each other in frequency.

Keywords: perceptual organization, auditory stream, stream segregation, temporal coherence

Introduction

The perceptual organization of sounds—“auditory scene analysis” (Bregman, 1990)—continues to be a major topic of investigation for auditory scientists (Shamma, Elhilali, & Micheyl, 2010; Shamma & Micheyl, 2010). In particular, the mechanisms underlying the perceptual organization of sound sequences into auditory “streams”—a phenomenon commonly referred to as “auditory streaming”— is an active area of research for auditory psychophysicists, behaviorists, and neuroscientists (for reviews, see: Bee & Micheyl, 2008; Carlyon, 2004; Fay, 2008; Moore & Gockel, 2012; Snyder & Alain, 2007). This line of research is important because it may hold the key to the design of artificial sound-processing systems that can parse complex acoustic scenes as effectively as humans do (Elhilali & Shamma, 2008; Haykin & Chen, 2005; Wang & Chang, 2008). In this context, auditory-perception research plays an instrumental role in identifying general principles, or “rules,” which govern the organization of multiple sound elements spread across frequency and time into coherent auditory streams.

Previous research on auditory streaming has revealed that tones presented in rapid succession tend to be perceived as a single coherent stream if their frequencies differ by a small amount, but split into distinctly separate streams when their frequencies differ by a large amount (Bregman & Campbell, 1971; Miller & Heise, 1950). This finding and others have led to the proposal that stream segregation depends, to a large extent, on sounds falling into distinct “frequency channels” in the auditory system—an idea which is sometimes referred to as the “channeling theory” (Hartmann & Johnson, 1991). This idea has been used in various computational models of auditory stream formation (Beauvois & Meddis, 1991; McCabe & Denham, 1997), including models based on neurophysiological data recorded in the central auditory system (Bee & Klump, 2004; Fishman, Reser, Arezzo, & Steinschneider, 2001; Micheyl et al., 2007; Micheyl, Tian, Carlyon, & Rauschecker, 2005; Pressnitzer, Sayles, Micheyl, & Winter, 2008). In these models, stream segregation depends primarily on the degree of “spatial” (tonotopic) separation between the responses of neural populations, or units, which respond selectively to sound frequencies. However, it is important to note that, even in these relatively simple models, tonotopic separation, and hence stream segregation, can be influenced by other factors than frequency separation. In particular, the rate at which sounds occur and the time elapsed since sequence onset both have an influence on neural responses in the central auditory system, which can account for the effects of these two factors on stream segregation (Bee & Klump, 2004, 2005; Bee, Micheyl, Oxenham, & Klump, 2010; Fishman, Arezzo, & Steinschneider, 2004; Fishman et al., 2001). In addition, tonotopic separation is not the only dimension that can induce streaming; for instance, differences in periodicity (Grimault, Bacon, & Micheyl, 2002; Vliegen & Oxenham, 1999) or waveshape (Stainsby, Moore, Medland, & Glasberg, 2004) can also lead to stream segregation, possibly based on differential responses in neural populations tuned to that particular feature (Moore & Gockel, 2002).

More recently, a different type of physiologically inspired computational model of auditory stream formation has been proposed (Elhilali, Ma, Micheyl, Oxenham, & Shamma, 2009; Elhilali & Shamma, 2008; Shamma et al., 2010). In this model, the organization of sounds into streams is determined by the extent to which neural responses to sounds in the auditory cortex are correlated over time across different neural populations: sounds that activate neural populations in a temporally coherent fashion are grouped into a single stream, whereas sounds that produce temporally incoherent neural responses tend to be assigned to separate streams. In this context, temporal coherence refers to temporal response correlations across populations of neurons tuned to different sound parameters, such as different frequencies, or to different sound features, such as pitch and spatial location (Shamma, Elhilali, & Micheyl, 2011). Perhaps the simplest example of temporally coherent sounds is obtained by presenting two tones at different frequencies synchronously, in a repeating fashion. The principle of “stream integration based on temporal coherence” incorporates and extends those of “stream integration based on frequency proximity” and of “perceptual grouping based on synchrony” (Bregman & Pinker, 1978). In particular, the principle can account for the fact that tones that are widely separated in frequency, and therefore excite well-separated neural populations in the peripheral and central auditory systems, can nonetheless be grouped into a single stream if they are presented in a temporally coherent fashion (Elhilali et al., 2009).

Because the temporal-coherence theory was formulated relatively recently, an important goal for auditory researchers is to submit this theory systematically to tests that can challenge it. The present study provides a further direct test of the temporal-coherence theory, using a relatively simple stimulus design. It differs from the study of Elhilali et al. (2009) in two important respects. Firstly, whereas Elhilali et al. only collected performance-based measures, here, both performance-based measures and judgments of perceptual organization (“I hear one stream” or “I hear two streams”) were collected in the same listeners, using very similar stimuli. While judgments of perceptual organization may be regarded as less “objective” than measures of performance in a task requiring veridical judgments, they have the potential to provide a straightforward answer to the question: how did the listener perceive this stimulus?

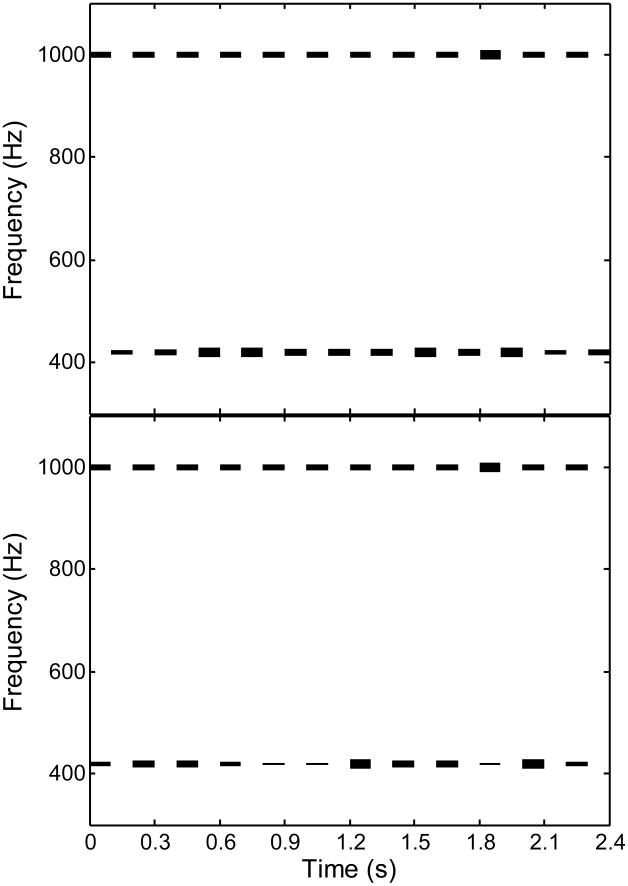

A second important difference between Elhilali et al.'s (2009) study and the current one is that the earlier study used a task that encouraged listeners to group sounds into a single stream, thereby taking advantage of any benefit bestowed through temporal coherence. In contrast, the task was used in the current study did the opposite: it encouraged listeners to segregate two tonal sequences presented concurrently in different frequency regions. Indeed, to perform well in the task, the listeners had to overcome any grouping induced through temporal coherence and ignore a sequence of “distractor” tones to focus their attention on the concurrently presented sequence of “target” tones, in which they had to detect the occurrence of a small intensity change (Figure 1). To limit listeners' ability to perform the task in cases where they were unable to listen selectively to the target tones, the distractor tones were randomly varied in level. Since the ability to attend selectively to a sequence of sounds in the presence of other sounds that vary randomly depends to a large extent on the ability to perceive the former tones as a separate stream, we reasoned that performance in this task would provide a more “objective” measure of the extent to which the listeners could segregate streams. To test the temporal-coherence and frequency-channeling theories, different stimulus conditions were used, including different frequency separations between the target and distractor tones, as well as conditions in which the target and distractor tones were either synchronous (temporal coherence) or asynchronous (temporal incoherence).

Figure 1.

Schematic spectrograms of examples of alternating and synchronous sequences of “target” and “distractor” tones. Each line segment represents a tone. Line thickness is used to represent tone intensity, with higher intensities indicated by thicker lines. In this example, the target tones had a higher frequency (1000 Hz) than the distractor tones (15 semitones below 1000 Hz, or approximately 421 Hz). The presence of a thicker line segment in the target sequence indicates the presence of a higher-intensity target, which the listeners had to detect; in these two examples, the 10th target tone had a higher intensity. Note that the intensity of the distractor tones was randomized in order to limit the listener's ability to detect the presence of a target tone unless the listener was able to ignore the distractor tones.

Experiment 1: Perceived Stream Segregation of Alternating and Synchronous Sounds

Rationale

As mentioned in the Introduction, numerous studies have been devoted to characterizing the perceptual organization of sound sequences in which the individual elements did not overlap in time. By contrast, very little is known regarding the perceptual organization of sequences of synchronous sounds. The aim of this experiment was to determine whether sequences of synchronous tones are perceived as a single stream or as two separate streams, and whether the dependence of stream segregation on frequency separation is different for synchronous tones and for alternating tones. Three hypotheses were considered.

According to the first hypothesis, stream segregation depends on frequency separation (or spectral contrast) and is uninfluenced by synchrony. Thus sequences of tones that are separated in frequency to the same extent should be perceptually organized in the same way regardless of whether they are alternating or synchronous. This outcome could be considered consistent with a strict interpretation of the “channeling” theory (Hartmann & Johnson, 1991; see also: Rose & Moore, 1997; Rose & Moore, 2000). According to this theory, stream segregation depends on separation of sounds into frequency-selective “channels” inside the auditory system, so that sounds that are well separated in frequency and fall into different peripheral channels are heard as separate streams.

The second hypothesis is based on psychophysical findings and modeling results which indicate that auditory stream formation depends, not on frequency separation per se, but on whether the sounds produce temporally coherent (i.e., correlated over time) neural responses (Elhilali et al., 2009; Elhilali & Shamma, 2008; Shamma et al., 2010). Importantly, this model can account for the fact that tones that are widely separated in frequency and, hence, produce spatially well separated neural responses in the primary auditory cortex, can form a single perceptual stream (Elhilali et al., 2009). According to this model, synchronous tones should be perceived as a single stream even for relatively large frequency separations between the A and B tones—separations for which the same tones are clearly perceived as separate streams when they are played in alternation. This outcome would be inconsistent with the strict “channeling” theory and with neurophysiologically inspired models in which stream segregation depends solely on frequency separation. It would be consistent with a strong version of the temporal-coherence theory according to which temporal coherence leads to stream integration despite peripheral-channel separation (Elhilali et al., 2009; Shamma et al., 2010).

A third hypothesis is that the perceptual organization of sound sequences depends on both frequency separation and temporal coherence, and that neither factor completely overrides the other. As a result, perceived stream segregation should increase less rapidly with increasing frequency separation for synchronous than for alternating tones. However, for relatively large frequency separations, the probability of perceiving a sequence of synchronous tones as two separate streams should be significantly higher than zero. This outcome would be inconsistent with a strict interpretation of either the channeling theory or the temporal-coherence theory. However, it would be consistent with a model in which the perceptual organization of sounds into streams depends on both temporal coherence and tonotopic separation of neural-population responses (Elhilali et al., 2009; Shamma et al., 2010; Shamma & Micheyl, 2010).

Methods

Listeners

Seven subjects (5 females and 2 males between the ages of 19 and 28 years) served as listeners. Before the experiment, listeners were tested for normal hearing with a Madsen Conera Audiometer and TDH-49 headphones. All had normal hearing, defined as pure-tone hearing thresholds of 20 dB HL or less at audiometric (octave) frequencies between 250 and 8000 Hz. All listeners in this study provided written informed consent and were compensated for their services. All testing took place in a double-walled sound-attenuating chamber.

Stimuli and procedure

The stimuli were pure tones, each 100 ms in duration, including 20-ms raised-cosine onset and offset ramps. Half of the tones had a fixed frequency of 1000 Hz; these tones are referred to as “B” tones. The other half of the tones, denoted as “A” tones, had a frequency 1, 3, 6, 9, or 15 semitones below 1000 Hz, i.e., at 943.9, 840.9, 707.1, 594.6, or 420.4 Hz. The A and B tones were presented either synchronously or in alternation. Each stimulus sequence consisted of 24 tones in total, including twelve A tones and twelve B tones. Tones of the same frequency were separated from each other in time by silent gaps of 100 ms. Therefore, the total duration of the sequence was 2.3 seconds for the synchronous case and 2.4 seconds for the alternating case. The tones were presented at a nominal level of 60 dB SPL. In order to make the stimuli used in this experiment as similar as possible to those used in Experiment 2, the actual level of the A tones varied over an 8-dB range (+/- 4 dB, selected with uniform distribution), and one of the B tones (selected at random, excluding the first four) in the sequence presented on a trial could, with a probability of 0.5, have a level 4-dB higher than the other B tones. As explained below, the random intensity variations in the A tones were introduced in order to limit the listeners' ability to take advantage of overall intensity cues, which might have allowed them to perform the perceptual task of Experiment 2 even if they heard the A and B tones in a single stream.

The ten different stimulus sequences (5 frequency separations × 2 presentation modes) were presented 28 times to each listener. In this experiment and those described below, the two presentation modes were tested in separate blocks of trials. Moreover, in the current experiment, the alternating sequences were always tested first. This was done to facilitate familiarization of the listeners with the task which we expected (based on previous studies) to be easiest to grasp with the alternating tones. The different frequency separations were presented in randomized order. Listeners were asked to indicate whether they heard a single, coherent sequence of tones, which they felt that they could only attend to as a whole (“one stream”), or two separate sequences of tones at different frequencies, which they felt that they could selectively attend to (“two streams”). They were informed that the percept could change during the course of the sequence, and were asked to focus on their percept toward the end of the sequence.

Apparatus

The stimuli were generated in Matlab and presented by means of a 24-bit digital-to-analog converter (LynxStudio Lynx22) diotically to both earphones of a Sennheiser HD580 headset. Listeners gave their responses by pressing keys “1” or “2” on a computer keyboard to denote the percept of one or two streams, respectively.

Data analysis

The number of “two streams” responses measured in the different stimulus conditions for each listener was analyzed using a hierarchical Bayesian non-linear (probit regression) model (Gelman & Hill, 2007; Rouder & Lu, 2005) based on the equal-variance Gaussian signal-detection theory (SDT) model of the Yes-No task (Green & Swets, 1966). The model, the details of which can be found in Appendix A, yielded estimates of the posterior probability distribution of the probability of a “two streams” response, P(“2 streams”). The model also returned an estimate of the posterior probability density of the probit-transformed (i.e., inverse cumulative standard normal function of) P(“2 streams”), referred to as d. The variable d may be thought of as another index of the listener's propensity to respond “two streams.” One advantage of this index is that, unlike P(“2 streams”), it is defined over the entire real line (-∞; +∞) rather than bounded between 0 and 1, and is therefore not as liable to floor and ceiling effects as probability or proportion.

Results and discussion

The box-and-whisker plots in Figure 2 show posterior quantiles for the probability of a “two streams” response, P(“2 streams”), for the synchronous and alternating conditions. The outer box limits and the whiskers indicate the 75% and 95% posterior intervals (also known as “Bayesian confidence intervals,” or “credible regions”), respectively. The thicker line near the middle of each box indicates the mode of the posterior distribution, which corresponds to the maximum-a-posteriori (MAP) value of P(“2 streams”), denoted as PMAP(“2 streams”).

Figure 2.

Posterior quantiles for the probability of a “two streams” response in Experiment 1. Whiskers indicate 95% credible regions. Upper and lower box limits indicate the twenty-fifth and seventy-fifth percentiles. The thicker bar near the center of each box indicates the posterior mode.

For the alternating presentation mode (empty boxes), consistent with previous studies (e.g., Carlyon, Cusack, Foxton, & Robertson, 2001; Cusack, Deeks, Aikman, & Carlyon, 2004), PMAP(“2 streams”) generally increased markedly as frequency separation increased from 1 to 15 semitones. Although the increase was steeper for some listeners (e.g., L1) than for others (e.g., L4), the effect was observed for all seven listeners. On average across the seven listeners, PMAP(“2 streams”) increased from about 0.11 for the smallest separation tested to about 0.97 for the largest separation.

For the synchronous presentation mode (filled boxes), the results were more variable across listeners. Although PMAP(“2 streams”) increased with frequency separation for four of the listeners (L1-L4), the increase was less pronounced for two of the remaining listeners (L5-L6) and, for one listener (L7), PMAP(“2 streams”) actually decreased as frequency separation increased. On average across all the listeners, PMAP(“2 streams”) increased from about 0.29 for the 1-semitone separation to about 0.76 for the 15-semitone separation.

To assess the statistical significance of the difference in P(“2 streams”) between the alternating and synchronous conditions, we examined 95% credible regions for that difference at the group level. For the three smaller frequency separation conditions (1, 3, and 6 semitones), the MAP differences were equal to -0.15 [-0.40; 0.09], -0.05 [-0.29; 0.18], and 0.11 [-0.10; 0.33], respectively, and the 95% credible regions (indicated between brackets) all encompassed zero. For the 9-, and 15-semitone separations, the MAP differences were equal to 0.23 [0.03 ; 0.40] and 0.19 [0.03; 0.44], and the 95% credible regions did not include zero. Thus, for these two separations, P(“2 streams”) was significantly higher for the alternating presentation mode than for the synchronous presentation mode.

To assess whether the increase in the propensity of responding “two streams” with increasing frequency separation differed statistically between the alternating and synchronous conditions, we examined the posterior distribution of the difference in the increase of P(“2 streams”) between 1 and 15 semitones across synchronous and asynchronous conditions. The MAP difference was equal to 0.35, and the associated 95% credible region [0.04; 0.72] did not contain zero, indicating that the difference was significant.

To summarize, the results of this experiment, which used measures of judgments concerning the perceptual organization of sound sequences, are partly consistent with the temporal-coherence theory in that the probability that the listeners judged a tone sequence as containing two streams was generally lower for synchronous tones than for alternating tones, at least for relatively large frequency separations (9 and 15 semitones). The probability also increased less with frequency separation for the synchronous tones than for the alternating tones.

Nevertheless the individual results were highly variable across listeners, with some listeners showing no difference between synchronous and asynchronous presentation (e.g., L1). Taken at face value, this outcome suggests that some listeners behave as predicted under the hypothesis that both temporal coherence and frequency separation influence auditory streaming, whereas other listeners behave as if only frequency separation mattered and synchrony was irrelevant. On the other hand, the interpretation of “one stream”/”two streams” judgments is complicated by the somewhat imprecise nature of the concept of a “stream” and the lack of experimenter control over the aspects of the percept on which listeners base their responses. For example, it is possible that some listeners based their responses on pitch separation rather than on stream segregation per se. These listeners may have associated stimuli containing small frequency differences with the “1 stream” response and stimuli containing large frequency differences with the “2 streams” response. The synchronous presentation may have made it more difficult for these listeners to distinguish the pitches of the A and B tones, and may have resulted in more variable judgments. Finally, other perceptual features could influence the listeners. For example, the unusual response pattern in listener L7 may have been due to this listener associating beats between the two synchronous tones at small frequency separations with the “two streams” response.

These caveats underscore the limitations of “one stream”/“two streams” judgments for investigating perceptual organization, and the need to supplement such measures with more controlled measures of perceptual organization (Bregman, 1990), such as those based on psychophysical measures of performance in tasks requiring veridical judgments that can be either enhanced or hindered by streaming (Darwin & Carlyon, 1995; Micheyl, Hunter, & Oxenham, 2010; Micheyl & Oxenham, 2010; Roberts, Glasberg, & Moore, 2002; Thompson, Carlyon, & Cusack, 2011). The following experiment involved such a performance-based measure in an attempt to gain further insight into the influence of synchrony on stream segregation.

Experiment 2: Performance Measure of the Effects of Synchrony and Frequency Separation on Stream Segregation

Rationale

In this experiment, the influence of synchrony on auditory stream segregation was investigated less directly but more “objectively” than in the first experiment, using a performance measure. Specifically, listeners performed a task that required veridical judgments concerning the occurrence or non-occurrence of an intensity change in a sequence of “target” tones while a sequence of “distractor” tones was presented at a different frequency, either synchronously or in alternation with the target tones. Importantly, the level of the distractor tones was varied randomly and independently from that of the target tones, so that listeners had to attend selectively to the target sequence in order to perform well in this task. Introspection and previous findings indicate that it is difficult to ignore sounds that are part of the same stream as the attended sounds. Therefore, we reasoned that performance in this task would be poor when the listener was not able to hear the target tones as a separate stream, and good when the listener was able to hear the target and distractor tones as separate streams. In other words, performance in this task would provide an “objective” (i.e., performance-based) measure of the extent to which the listeners were able to perceptually segregate the target and distractor tones that does not rely on introspection. We also reasoned that, since this task encouraged listeners to form separate streams, the results might be less variable across listeners than in experiment 1, where listeners were free to select both their listening and response strategies.

Methods

Listeners

Eight listeners participated in this experiment. Six of these listeners were the same listeners, L1 through L6, who also participated in experiment 1. The other two listeners (L8 and L9) were new.

Stimuli and procedure

The stimuli were similar to those used in experiment 1. Importantly, the intensity of one of the B tones (chosen at random, excluding the first four) could be increased by 4 dB with a probability of 0.5 (see example in Figure 1); when this happened, the selected B tone had a level of 64 dB SPL instead of 60 dB SPL. The reason for never applying the intensity change to one of the first four B tones was to allow stream segregation to “build up” prior to the occurrence of the change (Bregman, 1978; Carlyon et al., 2001; Thompson et al., 2011). The listener's task was to listen to the B tones while trying to ignore the A tones, and to report whether or not a level change occurred within the B-tone sequence, disregarding the spurious level variations in the A tones. As in experiment 1, the level of the A tones was roved over a 8-dB (+/-4 dB) range and one or two of the A tones (chosen at random) had their level increased by 4 dB on top of the imposed rove; the roving, combined with the presence of spurious higher-level tone(s) in the distractor sequence, ensured that listeners would perform poorly if they were unable to ignore the A tones. After each response, feedback was provided in the form of a message (“correct” or “wrong”) displayed on the computer screen. As in experiment 1, the tones were presented either in alternation or synchronously (in separate blocks), and different frequency separations (1, 3, 6, 9, and 15 semitones, as in experiment 1) were tested.

Listeners first took part in a practice phase aimed at familiarizing them with the experimental procedure and task. During this phase they performed the task starting with only the target (B) tones (and no distractor A tones). Then, the distractors were introduced at the largest frequency separation (15 semitones), first alternating, then synchronous. Subsequently, the frequency separation was progressively reduced (from 9 semitones, to 6 semitones, to 3 semitones, and finally 1 semitone) while listeners continued to perform blocks of trials involving alternating distractors followed by blocks of trials involving synchronous distractors. Each listener performed at least 100 trials per block, with each block corresponding to one presentation mode (alternating or synchronous) and one frequency separation. This practice phase was followed by a “test” phase. During the test phase (i.e., the experiment proper), the different presentation-mode and frequency-separation conditions were tested in random order in blocks of 51 or 52 trials each. To minimize the confusion that might result from synchronous and alternating tones being intermingled across trials, the two stimulus-presentation modes were tested in separate blocks. However, “synchronous blocks” and “alternating blocks” were mingled within a given session. In this test phase, listeners performed between 104 and 216 trials per condition depending on their availability—over 200 trials per condition per listener were obtained for 86% of the cases.

Data analysis

At the end of the test phase, the number of hits (i.e., “change present” responses on trials on which a change did occur in the target stream) and the number of false-alarms (i.e., “change present” responses on trials on which no change occurred in the target stream) were tallied and used to compute estimates the signal-detection theoretic measures of sensitivity (d') and bias (c') (Green & Swets, 1966). The details of this analysis are described in Appendix B.

Results and discussion

Figure 3 shows posterior quantiles for d' for the eight listeners who participated in this experiment. With the exception of listener L3, for whom the MAP d' (d'MAP) was usually close to zero (indicating very poor performance), the d'MAP generally increased with frequency separation over the 1- to 15-semitone range, and this increase was usually larger for the alternating than for the synchronous presentation mode. These trends are reflected in the group-level posteriors, which are shown in the upper panel of Figure 4.

Figure 3.

As Fig. 2 but showing individual posterior quantiles for d' for Experiment 2.

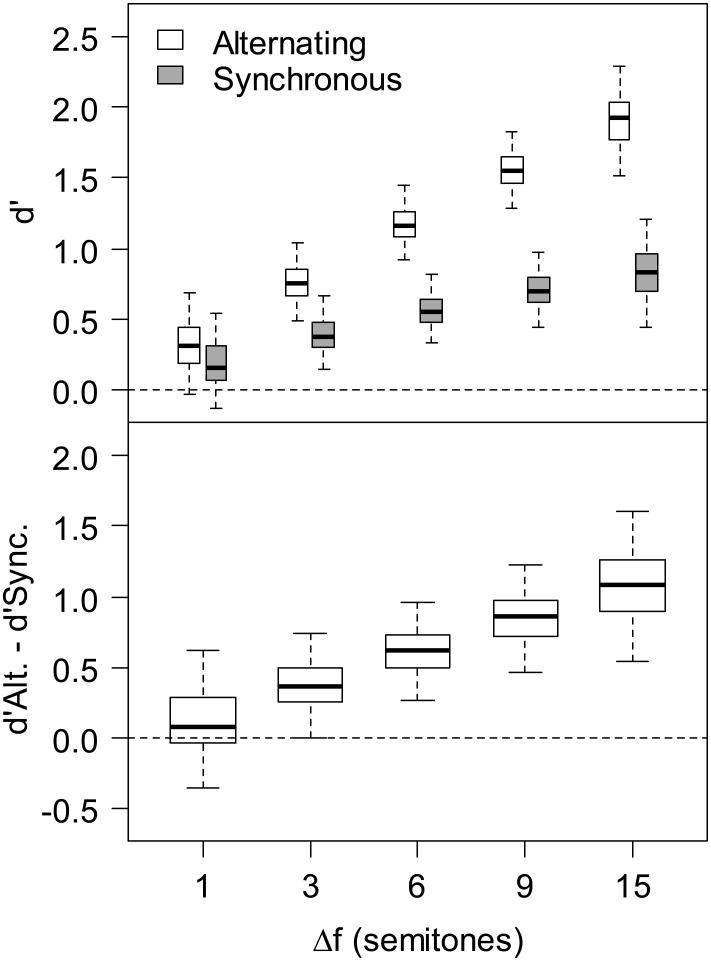

Figure 4.

As Fig. 2 but showing group-level posterior quantiles for d' and for the difference in d' between the alternating and synchronous presentation modes for Experiment 2.

To determine whether the differences in d' between the two presentation modes were significant, we examined posterior distributions for the difference in d' between the alternating and synchronous modes. The results are shown in the lower panel of Figure 4 for the group, and in Figure 5 for the individual results. For all listeners except L3, significant differences in d' between the synchronous and alternating presentation modes were observed for at least one of the frequency separations tested. In general, the differences were such that d' was higher for the alternating than for the synchronous presentation mode. Based on the 95% credible regions for the difference in d' between the two presentation modes (Figure 4, lower panel), d' was significantly higher for the alternating condition than for the synchronous condition for the three largest separations tested (6, 9, and 15 semitones), with a borderline outcome for the 3-semitone separation.

Figure 5.

As Fig. 2 but showing individual posterior quantiles for the difference in d' between the alternating and synchronous presentation modes for Experiment 2.

Figure 6 shows the group-level posterior quantiles for the decision-criterion measure, c'. As indicated by the fact that the 95% credible regions for this variable always included zero (which corresponds to no bias), there was no significant bias at the group level. However, a trend is apparent for c' to fall below the zero line, suggesting that, on the whole, the listeners tended to be slightly conservative in their responses concerning the presence of a target.

Figure 6.

As Fig. 2 but showing group-level posterior quantiles for c' for Experiment 2.

Experiment 2a: Assessing the Role of Masking

Rationale

The aim of this control experiment was to test whether the difference in performance between the alternating and synchronous presentation modes, observed in the previous experiment, would also be observed when the target tones were lower in frequency than the distractors. An effect of frequency order might be expected based on the “upward spread of masking,” whereby a masker that is lower in frequency than the target generally has a greater masking effect than a masker that is higher in frequency than the target (Egan & Hake, 1950). Thus, if the difference between the alternating and synchronous presentation modes at the larger frequency separations was due entirely to peripheral masking, the difference should be less in the current experiment, where the target frequency was below that of the distractor.

Methods

Listeners

Six of the eight listeners who participated in Experiment 2 (L1, L2, L3, L4, L6, and L8) also participated in this control experiment.

Stimuli, procedure, and data analysis

This experiment was identical to Experiment 2, except that the distractor (A) tones were always higher in frequency than the target (B) tones, and that only two A-B frequency separations (6 and 15 semitones) were tested. Data were analyzed using the same model as for the previous experiment.

Results and discussion

For the smaller frequency separation (6 semitones), the group-level d'MAP was 0.55 (with a 95% credible region of [0.03; 1.02]) for the alternating presentation mode, and was 0.16 ([-0.25; 0.66]) for the synchronous presentation mode. Note that the 95% credible region encompasses zero for the synchronous mode, suggested that sensitivity was not significantly above chance in this condition. The MAP difference in d' between the two presentation modes was equal to 0.37, with a 95% credible region of [-0.32; 1.00]. Thus, even though the 95% credible region for d'MAP in the asynchronous presentation mode did not encompass zero, the difference between the two presentation modes at the smaller frequency separation was not statistically significant.

For the larger frequency separation (15 semitones), the group-level d'MAP was equal to 0.84 (with a 95% credible region of [0.40; 1.38]) for the alternating presentation mode, and to 0.12 ([-0.34; 0.62]) for the synchronous presentation mode. Again, the 95% credible region of d' for the synchronous condition includes zero, indicating that performance was not significantly above chance in that condition. The MAP difference in d' between the two presentation modes was equal to 0.66, with a credible region of [0.03; 1.41]. Thus, for this frequency separation, d' was significantly higher for the alternating than for the synchronous presentation mode. This outcome argues against the idea that significantly poorer sensitivity for the synchronous than for the alternating presentation mode in Experiment 2 was due entirely to peripheral masking, because such masking was unlikely to be significant for such a large (15-semitone) frequency separation between the target and distractor tones. Thus, the detrimental effect of the synchronous distractor tones on sensitivity in both experiments was probably caused by central factors.

Perceptual masking effects that cannot be accounted for by peripheral mechanisms are traditionally referred to as “informational masking” effects in the auditory-perception literature (Durlach et al., 2003). Previous findings have suggested that informational masking effects arise in conditions where the target sound is not well separated perceptually from the masker(s), e.g., when target and masker tones fall into the same auditory stream (Kidd, Mason, Deliwala, Woods, & Colburn, 1994). The results of the current study are consistent with this, showing long-distance perceptual interference effects in Experiments 2 and 2a under stimulus conditions (synchronous presentation) which, according to Experiment 1, made it more difficult for some listeners to perceptually organize the target and masker tone sequences into separate streams.

The reason why sensitivity was generally lower in Experiment 2a than in Experiment 2 is unclear. One interpretation is that “hearing out” and following lower-pitch target targets in the presence of higher-pitch distractors may be more difficult than vice versa. Alternatively, since the listeners performed the current experiment after Experiment 2, we cannot rule out the possibility that, after they had learned to pay attention to the higher-pitch stream, the listeners found it difficult to do change their listening strategy to do just the opposite.

Experiment 3: Characterizing the Dependence of Stream Segregation on Onset Delay

Rationale

In all of the experiments described above, the target and distractor tones were either synchronous, or their onsets were separated by 100 ms so that the tones never overlapped temporally. The results of these experiments showed differences in sensitivity (d') between these two extreme stimulus conditions. However, they provided no information regarding how sensitivity varies as a function of onset delay between these two extremes. The aim of Experiment 3 was to characterize the dependence of d' on the delay between the onsets of the target and distractor tones over the range from 0 to 100 ms. We were particularly interested in determining whether d' increases slowly over this range of delays, or whether a relatively small delay is already sufficient to produce differences in sensitivity as large as those observed between the synchronous and alternating conditions in Experiment 2. Based on the results of previous studies, which indicate that relatively small temporal shifts (a few tens of ms) may be sufficient to induce stream segregation (Bregman & Pinker, 1978; Elhilali et al., 2009; Turgeon, Bregman, & Roberts, 2005), we expected sensitivity for tones staggered by as little as 30 ms to be significantly larger than sensitivity for synchronous tones, and similar to sensitivity for tones staggered by 100 ms.

Method

Listeners

Seven listeners (L1-L6, and L8) participated in this experiment.

Stimuli and procedure

The methods of this experiment were the same as for Experiment 2, except that a single frequency separation was tested (15 semitones) and that onset-time differences between the target and distractor tones of 35, 50, and 71 ms were tested in addition to 0 and 100 ms. These onset delays, which correspond approximately to constant steps on a logarithmic time scale, were tested in randomized order.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using a variant of the model used to analyze the data of Experiment 2, with the frequency-separation parameter replaced by an onset-delay factor, and the presentation-mode factor removed.

Results and discussion

Figure 7 shows individual- and group-level posterior quantiles of d' for the different delay conditions. With the exception of L3, whose performance was—as in Experiment 2—generally quite low and often not significantly higher than the chance level, a trend was observed for d' to increase as the delay between the target- and distractor-tone onsets increased from 0 to 100 ms. The trend was more marked for some listeners (L4, L6, and L8) than for others (L1, L2, and L5). The group-level results showed a gradual increase in d' with increasing delay: the mean d'MAP increased from approximately 1.48 for the 0-ms delay to 2.43 for the 100-ms delay.

Figure 7.

As Fig. 2 but showing group-level posterior quantiles for d' for Experiment 3.

To quantify the statistical significance of the increase in d' with increasing delay, we examined the 95% credible regions for the differences in d' between different delay conditions. The credible region for the difference between the 0- and 100-ms delay (MAP = 1.10; 95% credible region: [0.03; 2.05]) was found not to include zero, indicating a significant increase in d' between these two extreme delay conditions. The only other pair of delay conditions for which a significant difference in d' (based on the 95% credible regions) was observed was for the 0- and 50-ms delays (MAP = 0.65; 95% credible region: [0.04; 1.42]).

The results of this experiment are consistent with those of Experiments 2 and 2a in that they show a significant difference in sensitivity to changes in intensity in the target stream in the presence of the distractor stream between the synchronous (0-ms delay) and alternating (100-ms delay) presentation modes, with higher sensitivity for the latter. In addition, the results show a gradual increase in sensitivity across this range of onset delays, at least at the group level. However, it is interesting to note in the individual data that some listeners (L6 and L8) showed an abrupt improvement in sensitivity as the onset delay increased from 0 to 35 ms. This indicates that, for some listeners, an asynchrony of 35 ms or less seems to be enough to “break” the perceptual-binding effect of temporal coherence and allow the separation of concurrently presented streams. This is consistent with other results in the literature, which also indicate that asynchronies of 20-40 ms (on average) are sufficient to induce stream segregation, at least for pure tones separated in frequency by 6 semitones or more (Elhilali et al., 2009), or when the target and masker sound differ in their spectral composition, and thus, their timbre (Turgeon et al., 2005). Onset-time asynchronies of about 30 ms have also been found to promote segregation of complex-sound components (Rasch, 1978; Turgeon et al., 2005). We can only speculate as to the origin of the relatively large inter-individual variability in the effects of across-frequency asynchrony on performance, which is apparent in the results of this experiment. Results in the literature show substantial inter-individual differences in tasks involving judgments of asynchrony between tones at different frequencies (Wojtczak, Beim, Micheyl, & Oxenham, 2012). It is conceivable that this variability, in turn, stems from inter-individual differences in neural-response delays across frequency.

Experiment 4: Do Frequency Shifts Facilitate Stream Segregation?

Rationale

The goal of this experiment was to test whether listeners' ability to attend selectively to the target tones in the presence of the synchronous distractor tones can be enhanced by variations in the frequency of the distractor tones over time. We reasoned that varying the frequency of the distractor tones between two values, while keeping the frequency of the target tones constant, would provide a salient cue for distinguishing the distractor tones from the target tones and, consequently, make it easier for the listeners to attend selectively to the target. If this were the case, then performance should be higher with the alternating-frequency distractors than with constant-frequency distractors. An alternative hypothesis, which was tested in this experiment, is that alternating the frequency of the distractors might draw the listener's attention to the distractors (Cusack & Carlyon, 2003). This hypothesis leads to the prediction that performance should be worse with the alternating-frequency distractors than with the constant-frequency distractors.

Another reason for investigating the influence of frequency variations in this study stemmed from the idea that “frequency-shift detectors” may play an important role in the perceptual “binding” of successive sounds and, therefore, in the formation of auditory streams (Demany & Ramos, 2005). These putative frequency-shift detectors have been found to be tuned preferentially to relatively small frequency changes—about 1 semitone, or approximately 6% (Demany, Pressnitzer, & Semal, 2009). If the activation of frequency-shift detectors in the auditory system promotes the perceptual grouping of sounds over time, then the introduction of small (1 semitone) frequency changes between successive distractor tones should promote the perceptual organization of these tones into a coherent stream. As a result, the (constant-frequency) target tones might be easier to hear out separately.

Methods

Listeners

Seven listeners (L1-L6 and L8) participated in this experiment.

Stimuli and procedure

The experiment was similar to Experiment 2, except that only two stimulus conditions were tested. In one of these two conditions, the frequency of the distractor tones was fixed at 420.45 Hz (i.e., 15 semitones below the frequency of the target tones, 1000 Hz). In the other condition, the frequency of the distractor tones alternated between 433.07 and 407.84 Hz. Note that these two frequencies are approximately centered on 420.45 Hz and are separated from each other by approximately 6% (or one semitone), which is close to the frequency-shift magnitude that optimally activates frequency-shift detectors in the human auditory system, according to a previous study (Demany et al., 2009). The target and distractor tones were always synchronous, and only one nominal frequency separation between these tones (15 semitones) was tested. The rationale for using a large frequency separation between the target and distractor tones was to limit peripheral interference effects. Moreover, based on the previous results showing large differences in sensitivity between the alternating and synchronous presentation mode for the 15-semitone separation, we reasoned that the difference between the two test conditions, if any, would be largest for that separation.

Data analysis

The Bayesian hierarchical model that was used to analyze these results was similar to that used to analyze the results of Experiment 2 (described in Appendix B), except that, since a single frequency-separation condition was tested, the multivariate Gaussian structure that was used to “tie” together the parameters corresponding to different frequency-separation conditions in the model used to analyzed the data of experiment 2 was no longer needed here. Moreover, since the tones were always synchronous, the index corresponding to the presentation mode was used to indicate whether the frequency of the distractor tones was constant or varying.

Results and discussion

The mean d' values for the two test conditions were almost identical, being equal to 1.35 (95% credible region: [0.61; 2.03]) for the condition in which the frequency of the distractor was fixed and to 1.34 (95% credible region: [0.78; 1.94]) for the condition in which the frequency of the distractor was alternating. Accordingly, the mean of the posterior mean difference in d' between the two test conditions across the seven listeners was very close to zero, being equal to 0.003, and the 95% credible region ([-0.94; 0.91]) included zero.

Only two of the seven listeners showed a significant difference in d' between the fixed-distractor-frequency and the alternating-distractor-frequency conditions. For one of these listeners, d' was larger for the alternating-distractor-frequency condition than for the fixed-distractor-frequency condition, with a mean d' difference of -0.45 (95% credible region: [-0.81; -0.08]), but for the other listener, the difference was in the opposite direction (mean = 0.84; 95% credible region: [0.06; 1.61]). Thus, although the introduction of frequency shifts in the distractor sequence appears to have helped one listener and hurt another listener, for most listeners, and on the average, it had no impact on performance.

A different outcome might have been obtained if, instead of being applied to the distractor tones, the frequency variations had been applied to the target tones. Indeed, findings in the literature suggest that frequency or intensity variations can enhance the salience of a sound, thus facilitating its detection or discrimination (Erviti, Semal, & Demany, 2011; Demany, Carcagno, & Semal, in press). Therefore, the present results should not be interpreted as evidence that the introduction of frequency variations cannot facilitate selective attention. However, the present results provide no evidence that small frequency shifts (6%), which according to previous studies should have strongly activated frequency-shift detectors in the human auditory system (Demany et al., 2009; Demany & Ramos, 2005), promote stream segregation for synchronously presented sounds.

General discussion

This study sought to investigate the influence of synchrony on auditory stream segregation using a combination of introspective perceptual-organization judgments (“one stream”/ “two streams”) and performance-based measures. In Experiment 1, listeners judged whether they heard sequences of alternating or synchronous tones as either one or two streams. Results were found to be highly variable across listeners, especially for the synchronous sequences: for some listeners the probability of reporting two streams was less for synchronous than for alternating tones, whereas other listeners showed no consistent difference between the two presentation modes. Taken at face value, these results suggest that some listeners behave according to the predictions of models in which stream formation depends crucially on temporal coherence (Elhilali et al., 2009; Elhilali & Shamma, 2008; Shamma et al., 2010), while other listeners behave according to the predictions of models in which stream segregation depends essentially on frequency (or tonotopic) separation (Fishman et al., 2001; Hartmann & Johnson, 1991). However, the interpretation of results based on introspective judgments is limited by the lack of experimenter control over the aspect(s) of the percept upon the listeners base their responses.

The performance-based measures (Experiments 2 and 3), which involved the detection of an intensity increment in the target tone in the presence of distractor tones, showed a clearer pattern of results, with several instances—at both the individual and group levels—of significantly lower sensitivity (d') to intensity changes when the target and distractor were synchronous than when they were asynchronous. The results of a control experiment (Experiment 2a) suggested that this effect could not be entirely explained in terms of peripheral (cochlear) interactions. An additional argument against a peripheral origin of the effect of synchrony on sensitivity stems from the fact that significant differences between the synchronous and asynchronous presentation modes were observed even for relatively large frequency separations between the tones, such as 15 semitones; for such large separations, it is unlikely that the moderate-level tones used in this study interacted sufficiently at the level of the cochlea to account for the observed differences in performance. Rather, the observed differences between the synchronous and asynchronous conditions were probably mediated by central factors. A likely explanation for the detrimental impact of synchrony on sensitivity is that synchrony promoted perceptual grouping across-frequency.

From this point of view, the results of Experiments 2 and 3 and, to a lesser extent, those of Experiment1, are consistent with neurophysiologically inspired and computational models of scene analysis in which temporal coherence—as reflected in correlations between the response patterns of neural populations activated by sounds—plays a role in the perceptual organization of sounds into streams (Elhilali et al., 2009; Shamma et al., 2010). The results are also consistent with earlier findings which demonstrate that temporal relationships between sound elements across frequency play an important role in the perceptual grouping of sounds (Bregman & Pinker, 1978; Dannenbring & Bregman, 1978). In fact, the findings of the present study can be explained parsimoniously in terms of synchrony or lack thereof, without necessarily involving the notion of temporal coherence. However, as mentioned above, the principle of temporal coherence usefully extends other perceptual-organization principles, such as grouping by frequency proximity or synchrony. As a result, models that incorporate this principle can account for psychoacoustical findings that cannot be accounted for by models that rely solely on frequency (tonotopic) separation or synchrony (Elhilali et al., 2009; Shamma et al., 2010).

The results of these experiments, in which large inter-individual differences were observed both for “one stream”/“two streams” judgments and for performance-based measures, underscore a need for theories and models of auditory-scene analysis to take into account the fact that different cues (or rules) may have a different relative importance in determining stream formation for different listeners.

Acknowledgments

Christophe Micheyl, Andrew Oxenham, and Shihab Shamma were supported by NIH grant R01 DC 07657; Coral Hanson was supported by NSF grant # SMA-1063006.

The authors would like to thank the Associate Editor, Dr. Soto-Faraco, and Drs. B.C.J. Moore, R. Cusack, and D. Jones for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Appendix A. Hierarchical Bayesian Model for Inferring Response Probabilities Given Response Counts

The data of Experiment 1 were analyzed using a Bayesian hierarchical non-linear (probit) regression model (for an introduction to hierarchical Bayesian models in psychophysics, see, e.g., Rouder & Lu, 2005). The number of “two streams” response measured in listener j, for the presentation mode (alternating, synchronous) indexed by m and the frequency separation (1, 3, 6, 9, or 15 semitones) indexed by k, nm,k,j, was modeled as a draw from a binomial distribution with parameter t (the total number of stimulus sequences presented in this test condition and this listener), and Ψm,k,j (the probability of a “two streams” response for this condition and this listener),

| (1) |

Ψm,k,j, was modeled as the integral of the standard-normal function of a latent variable, dm,k,j,

| (2) |

dm,k,j represents the listener's propensity of responding “two streams” on the real line, with negative values corresponding to a higher propensity of responding “one stream” than responding “two streams,” and positive values corresponding to the opposite situation.

The random variable, dm,k,j, was assumed to be drawn from a Gaussian distribution with mean, μm,k,j, and variance, σ2,

| (3) |

This allowed fluctuations in sensitivity (due, possibly, to fluctuations in the level of attention) across different test conditions within a given listener to be taken into account in the model.

The mean propensity vector, μm,j =[μm,1,j, …, μm,5,j], was drawn from a multivariate Gaussian with a constant mean given by a five-element zero vector, μ0, and a covariance matrix, Σm,

| (4) |

The covariance matrix, Σm, was obtained as the inverse of the precision matrix, Ωm, which was drawn from a Wishart prior parameterized in terms of a prior covariance matrix, Vm, and scale, ν, as required by the jags software (Plummer, 2011) used to implement this probabilistic model,

| (5) |

Each element of the prior covariance matrix, Vm[x,y] (where x and y are row and columns indices) was defined by the following equation,

| (6) |

This covariance structure corresponds to a Gaussian-process regression model (Rasmussen & Williams, 2006) in which the covariance function is a weighted sum of an isotropic quadratic-exponential covariance function and a “linear” covariance function. The first term models decaying correlations as a function of distance, thus enforcing a smoothness constraint on μm,k,j across k, reflecting a prior assumption that variations in the mean propensity of responding “two streams” across k were unlikely to be abrupt. The second term models a linear trend in μm,k,j as a function of k, reflecting a prior assumption (based on the results of many previous studies) that the propensity to respond “two streams” was likely to increase with frequency separation, at least for the alternating tones. Note that the parameters, αm, βm, and λm, are all indexed by m, the presentation mode; these parameters were estimated independently for the two presentation modes.

Although the Gaussian-process regression model described above is more complex than a generalized linear model, it presents several advantageous features over the latter. In particular, it does not assume a linear relationship between frequency separation and the listener's propensity to respond “two streams,” and it can accommodate a wide variety of functional relationships, including both linear and nonlinear ones. Moreover, since the mean propensities of responding “two streams” corresponding to different listeners and different frequency separations were estimated jointly, rather than independently (as would have been the case if point estimates of the “two streams” response probabilities had been computed instead), the model allows for desirable “shrinkage” effects (Carlin & Louis, 2009; Gelman & Hill, 2007; Rouder & Lu, 2005) across the different frequency-separation conditions.

Vaguely informative priors were placed on the model parameters. Specifically, truncated Gaussian priors (yielding only non-negative values) with zero means and variances equal to 1000, 1000, and 100 were placed on the parameters, αm, βm, and λm. A Gamma(1, 1) prior was placed on the variance of the within-subject error term, σ2, reflecting a prior assumption that this error should remain relatively small, compared to the across-individual variability and to the effect of frequency separation within a given listener. The scale parameter of the Wishart prior on Vm was set to 7, i.e., the dimension of the covariance matrix plus 1 (Carlin & Louis, 2009).

All model parameters were estimated using Markov-chain Monte-Carlo (MCMC) methods implemented in rjags v3.5 (Plummer, 2011) under R (R Development Core Team, 2011). Posterior distributions were estimated based on 5000 samples (obtained by thinning 50000 samples using a 10-sample thinning interval) following a 50000-sample burn-in phase. Convergence of the chains was assessed using trace and autocorrelation plots and other quantitative diagnostic tools implemented in the CODA package (Plummer, Best, Cowles, & Vines, 2006). Scale-reduction factors (Gelman & Rubin, 1992) were generally close to 1.00.

Appendix B. Hierarchical Bayesian Model for Inferring d' and c

The data from experiments 2-4 were analyzed using a variant of the model described in Appendix A, modified to account for the fact that these experiments returned counts of hits and of false-alarms. These counts were used to infer sensitivity (d') and bias (c') for each listener and test condition; by definition, c' = 0 for an unbiased listener (Macmillan & Creelman, 2005). First, the hit and false-alarm counts measured for presentation mode indexed by m, condition indexed by k, and listener j, hm,k,j, and fm,k,j, were assumed to be drawn from binomial distributions defined by the corresponding hit and false-alarm probabilities, πm,k,j and φm,k,j, and the corresponding numbers of target-present and target-absent trials, n1m,k,j, and n0m,k,j,

| (7) |

| (8) |

πm,k,j and φm,k,j were related to d' and to the criterion, c, according to the standard Gaussian signal-detection-theory model of the observer for the Yes-No task (Green & Swets, 1966; Macmillan & Creelman, 2005),

| (9) |

| (10) |

The “unbiased” criterion, c'm,k,j, is obtained by subtracting 0.5d'm,k,j from cm,k,j.

The same priors as used for the variable dm,k,j in the model described in Appendix A were used for the variables d'm,k,j and c'm,k,j in the current model. Model parameters were estimated using MCMC methods as described in Appendix A.

Contributor Information

Christophe Micheyl, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Coral Hanson, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Andrew Oxenham, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

Laurent Demany, Université de Bordeaux, and CNRS, Bordeaux, France.

Shihab Shamma, University of Maryland, MD, and Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, France.

References

- Beauvois MW, Meddis R. A computer model of auditory stream segregation. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A. 1991;43(3):517–541. doi: 10.1080/14640749108400985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee MA, Klump GM. Primitive auditory stream segregation: a neurophysiological study in the songbird forebrain. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2004;92(2):1088–1104. doi: 10.1152/jn.00884.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee MA, Klump GM. Auditory stream segregation in the songbird forebrain: effects of time intervals on responses to interleaved tone sequences. Brain Behavior and Evolution. 2005;66(3):197–214. doi: 10.1159/000087854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee MA, Micheyl C. The cocktail party problem: what is it? How can it be solved? And why should animal behaviorists study it? Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2008;122(3):235–251. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.122.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bee MA, Micheyl C, Oxenham AJ, Klump GM. Neural adaptation to tone sequences in the songbird forebrain: patterns, determinants, and relation to the build-up of auditory streaming. Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Neuroethology, Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology. 2010;196(8):543–557. doi: 10.1007/s00359-010-0542-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman AS. Auditory streaming is cumulative. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception Performance. 1978;4(3):380–387. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.4.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman AS. Auditory Scene Analysis: The Perceptual Organisation of Sound. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bregman AS, Campbell J. Primary auditory stream segregation and perception of order in rapid sequences of tones. Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1971;89(2):244–249. doi: 10.1037/h0031163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bregman AS, Pinker S. Auditory streaming and the building of timbre. Canadian Journal of Psychol. 1978;32(1):19–31. doi: 10.1037/h0081664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlin BP, Louis TA. Bayesian Methods for Data Analysis. Third. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Carlyon RP. How the brain separates sounds. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2004;8(10):465–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlyon RP, Cusack R, Foxton JM, Robertson IH. Effects of attention and unilateral neglect on auditory stream segregation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2001;27(1):115–127. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.27.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack R, Deeks J, Aikman G, Carlyon RP. Effects of location, frequency region, and time course of selective attention on auditory scene analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2004;30(4):643–656. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.30.4.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannenbring GL, Bregman AS. Streaming vs. fusion of sinusoidal components of complex tones. Perception & Psychophysics. 1978;24(4):369–376. doi: 10.3758/bf03204255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin CJ, Carlyon RP. Auditory organization and the formation of perceptual streams. In: Moore BCJ, editor. Handbook of Perception and Cognition. Vol. 6. Hearing. San Diego: Academic; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Demany L, Carcagno S, Semal C. The perceptual enhancement of tones by frequency shifts. Hearing Research. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2013.01.016. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demany L, Pressnitzer D, Semal C. Tuning properties of the auditory frequency-shift detectors. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2009;126(3):1342–1348. doi: 10.1121/1.3179675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demany L, Ramos C. On the binding of successive sounds: perceiving shifts in nonperceived pitches. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;117(2):833–841. doi: 10.1121/1.1850209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlach NI, Mason CR, Kidd G, Jr, Arbogast TL, Colburn HS, Shinn-Cunningham BG. Note on informational masking. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2003;113(6):2984–2987. doi: 10.1121/1.1570435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan JP, Hake HW. On the masking pattern of a simple auditory stimulus. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1950;22(5):622–630. [Google Scholar]

- Elhilali M, Ma L, Micheyl C, Oxenham AJ, Shamma SA. Temporal coherence in the perceptual organization and cortical representation of auditory scenes. Neuron. 2009;61(2):317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.005. S0896-6273(08)01053-2 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhilali M, Shamma SA. A cocktail party with a cortical twist: how cortical mechanisms contribute to sound segregation. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2008;124(6):3751–3771. doi: 10.1121/1.3001672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erviti M, Semal C, Demany L. Enhancing a tone by shifting its frequency or intensity. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2011;129(6):3837–3845. doi: 10.1121/1.3589257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay RR. Sound source perception and stream segregation in nonhuman vertebrate animals. In: Yost WA, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Auditory Perception of Sound Sources. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 307–323. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman YI, Arezzo JC, Steinschneider M. Auditory stream segregation in monkey auditory cortex: effects of frequency separation, presentation rate, and tone duration. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2004;116(3):1656–1670. doi: 10.1121/1.1778903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman YI, Reser DH, Arezzo JC, Steinschneider M. Neural correlates of auditory stream segregation in primary auditory cortex of the awake monkey. Hearing Research. 2001;151(1-2):167–187. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Hill J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Rubin DA. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Statistical Science. 1992;7(4):457–472. [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics. New York: Krieger; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Grimault N, Bacon SP, Micheyl C. Auditory stream segregation on the basis of amplitude-modulation rate. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2002;111(3):1340–1348. doi: 10.1121/1.1452740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann WM, Johnson D. Stream segregation and peripheral channeling. Music Perception. 1991;9(2):155–184. [Google Scholar]

- Haykin S, Chen Z. The cocktail party problem. Neural Computation. 2005;17(9):1875–1902. doi: 10.1162/0899766054322964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd G, Jr, Mason CR, Deliwala PS, Woods WS, Colburn HS. Reducing informational masking by sound segregation. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1994;95(6):3475–3480. doi: 10.1121/1.410023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan NA, Creelman CD. Detection Theory: A User's Guide. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SL, Denham MJ. A model of auditory streaming. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1997;101:1611–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Micheyl C, Carlyon RP, Gutschalk A, Melcher JR, Oxenham AJ, Rauschecker JP. The role of auditory cortex in the formation of auditory streams. Hearing Research. 2007;229(1-2):116–131. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.01.007. S0378-5955(07)00024-X [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheyl C, Hunter C, Oxenham AJ. Auditory stream segregation and the perception of across-frequency synchrony. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2010;36(4):1029–1039. doi: 10.1037/a0017601. 2010-15881-018 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheyl C, Oxenham AJ. Objective and subjective psychophysical measures of auditory stream integration and segregation. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology. 2010;11(4):709–724. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micheyl C, Tian B, Carlyon RP, Rauschecker JP. Perceptual organization of tone sequences in the auditory cortex of awake macaques. Neuron. 2005;48(1):139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Heise GA. The trill threshold. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1950;22(5):637–638. [Google Scholar]

- Moore BCJ, Gockel H. Factors influencing sequential stream segregation. Acta Acustica united with Acustica. 2002;88:320–333. [Google Scholar]

- Moore BCJ, Gockel HE. Properties of auditory stream formation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences. 2012;367(1591):919–931. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0355. rstb.2011.0355 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M. rjags: Bayesian Graphical Models Using MCMC 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Plummer M, Best N, Cowles K, Vines K. CODA: Convergence Diagnosis and Output Analysis for MCMC. R News. 2006;6:7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pressnitzer D, Sayles M, Micheyl C, Winter IM. Perceptual organization of sound begins in the auditory periphery. Current Biology. 2008;18:1124–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rasch RA. The perception of simultaneous notes, such as in polyphonic music. Acustica. 1978;40:21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen CE, Williams C. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B, Glasberg BR, Moore BC. Primitive stream segregation of tone sequences without differences in fundamental frequency or passband. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2002;112(5 Pt 1):2074–2085. doi: 10.1121/1.1508784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MM, Moore BC. Perceptual grouping of tone sequences by normally hearing and hearing-impaired listeners. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1997;102(3):1768–1778. doi: 10.1121/1.420108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose MM, Moore BC. Effects of frequency and level on auditory stream segregation. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2000;108(3 Pt 1):1209–1214. doi: 10.1121/1.1287708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouder JN, Lu J. An introduction to Bayesian hierarchical models with an application in the theory of signal detection. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2005;12(4):573–604. doi: 10.3758/bf03196750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamma SA, Elhilali M, Micheyl C. Temporal coherence and attention in auditory scene analysis. Trends in Neuroscience. 2010;34(3):114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.11.002. S0166-2236(10)00167-0 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamma SA, Micheyl C. Behind the scenes of auditory perception. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2010;20(3):361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.03.009. S0959-4388(10)00047-4 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder JS, Alain C. Toward a neurophysiological theory of auditory stream segregation. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(5):780–799. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stainsby TH, Moore BC, Medland PJ, Glasberg BR. Sequential streaming and effective level differences due to phase-spectrum manipulations. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2004;115(4):1665–1673. doi: 10.1121/1.1650288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SK, Carlyon RP, Cusack R. An objective measurement of the build-up of auditory streaming and of its modulation by attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 2011;37(4):1253–1262. doi: 10.1037/a0021925. 2011-07485-001 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon M, Bregman AS, Roberts B. Rhythmic masking release: effects of asynchrony, temporal overlap, harmonic relations, and source separation on cross-spectral grouping. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance. 2005;31(5):939–953. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.31.5.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vliegen J, Oxenham AJ. Sequential stream segregation in the absence of spectral cues. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;105(1):339–346. doi: 10.1121/1.424503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Chang P. An oscillatory correlation model of auditory streaming. Cognitive Neurodynamics. 2008;2(1):7–19. doi: 10.1007/s11571-007-9035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtczak M, Beim JA, Micheyl C, Oxenham AJ. Perception of across-frequency asynchrony and the role of cochlear delays. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2012;131(1):363–377. doi: 10.1121/1.3665995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]