Abstract

The accumulation of β-amyloid (Aβ) is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease and is known to result in neurotoxicity both in vivo and in vitro. We previously demonstrated that treatment with the water extract of Centella asiatica (CAW) improves learning and memory deficits in Tg2576 mice, an animal model of Aβ accumulation. However the active compounds in CAW remain unknown. Here we used two in vitro models of Aβ toxicity to confirm this neuroprotective effect, and identify several active constituents of the CAW extract. CAW reduced Aβ-induced cell death and attenuated Aβ-induced changes in tau expression and phosphorylation in both the MC65 and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell lines. We confirmed and quantified the presence of several mono- and dicaffeoylquinic acids (CQAs) in CAW using chromatographic separation coupled to mass spectrometry and ultraviolet spectroscopy. Multiple dicaffeoylquinic acids showed efficacy in protecting MC65 cells against Aβ-induced cytotoxicity. Isochlorogenic acid A and 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid were found to be the most abundant CQAs in CAW, and the most active in protecting MC65 cells from Aβ-induced cell death. Both compounds showed neuroprotective activity in MC65 and SH-SY5Y cells at concentrations comparable to their levels in CAW. Each compound not only mitigated Aβ-induced cell death, but was able to attenuate Aβ-induced alterations in tau expression and phosphorylation in both cell lines, as seen with CAW. These data suggest that CQAs are active neuroprotective components in CAW, and therefore are important markers for future studies on CAW standardization, bioavailability and dosing.

Keywords: β-amyloid toxicity, Centella asiatica, caffeoylquinic acids, tau, neuroprotection

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia and is predicted to affect as many as 100 million people worldwide by 2050 [1]. The two principal pathological hallmarks of the disease in the brain, are plaques made up of β-amyloid (Aβ), and neurofibrillary tangles, comprised primarily of hyperphosphorylated tau [2]. Because changes in Aβ are evident prior to tau abnormalities [3] it is thought that tangle formation is downstream of Aβ accumulation in the progression of the disease [4] and numerous preclinical experiments support this idea [5-8]. In recent trials, Aβ lowering treatments have proved ineffective in improving clinical outcomes [9, 10], leading to the belief that targeting the toxic consequences of Aβ may be more therapeutically relevant than reducing plaque burden. An increasing number of people are turning to alternative therapies, including botanical products, to try and achieve these results [11, 12].

Centella asiatica (L.) Urban, (Apiaceae), known in the United States as Gotu Kola, is an edible plant that has been used for centuries in the Indian medical system of Ayurveda to boost memory, improve cognitive function and reverse cognitive impairments [13]. Extracts of Centella asiatica have been shown to be neuroprotective or neurotropic in a number of preclinical models. A great deal of variability exists in the chemical composition, and consequently biological properties, of different Centella asiatica extracts. In addition to variability due to diverse growing conditions of the source Centella asiatica plant material [14, 15], the method of extraction has a substantial effect on the types of chemical compounds present in an extract [16, 17]. We have previously demonstrated that the chemical profile of an ethanol extract from Centella asiatica is quite different from that of a water extract of the same batch of plant material[18]. In rodents, extracts of Centella asiatica have attenuated neurobehavioral and neurochemical effects of stroke [19], accelerated nerve regeneration [20], protected against oxidative neurotoxicity [21] and showed anti-inflammatory [22] and antioxidant effects [23]. In addition to these effects, the cognitive enhancing action of water extracts of Centella asiatica has also been demonstrated in multiple animal models [24-26] and in limited human studies [27-30]. An extract of Centella asiatica was also shown to decrease Aβ plaque burden in a transgenic mouse model of AD, however the extraction method was not described making it difficult to speculate which compounds may be responsible for that effect[31].

We have previously shown that a water extract of Centella asiatica (CAW) attenuates Aβ-induced cognitive impairments in the Tg2576 mouse model of AD [18]. These mice express a mutant form of human amyloid precursor protein leading to age-dependent Aβ accumulation in the hippocampus and cortex, and concomitant learning and memory deficits [32]. We found that two weeks of treatment with CAW in the drinking water normalized the Morris Water Maze and open field behavioral deficits normally observed in aged Tg2576 animals. Notably, CAW treatment did not alter Aβ levels in the brain suggesting that CAW may act downstream of Aβ formation to mitigate the toxic consequences.

Despite the impressive biological effects of CAW, the active compounds underlying its action remain unknown. Much of the biological activity associated with Centella asiatica is attributed to the triterpene compounds present in the plant. Asiatic acid, madecassic acid, asiaticoside and madecassoside are the major triterpene constituents found in Centella asiatica [33]. However, while these compounds are abundant in an ethanol extract of Centella asiatica, the triterpenes were not found in the CAW extract that reversed behavioral abnormalities in the Tg2576 mouse model [18], indicating that other compounds in the extract must be responsible for the beneficial effects observed.

The goal of the present project was to identify the compounds associated with neuroprotective activity of CAW. The phytochemical profile of CAW was investigated using thin layer chromatography (TLC) or high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) and ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy. We used two in vitro models of Aβ toxicity, the MC65 and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell lines, to investigate activity of compounds within CAW. MC65 cells are a model of intracellular Aβ toxicity as they conditionally express the C-terminal fragment of amyloid precursor protein (APP) [34]. In contrast SH-SY5Y cells are widely used to study the effect of exogenously administered Aβ peptide [35-41]. We examined the effects of CAW, and as well as compounds found within the extract, on cell viability as well as tau expression and phosphorylation in both of these model systems.

Materials and Methods

Aqueous extract of Centella asiatica

Dried Centella asiatica was purchased from StarWest Botanicals, Sacramento, CA (Lot no. 45158). The identity of the plant was confirmed by visual examination and by comparing its thin layer chromatographic profile with that reported in the literature [42] and the Centella asiatica sample used in our previous study [18]. The dried water extract of Centella asiatica (CAW) was prepared by refluxing Centella asiatica (60g) with water (750mL) for 1.5 hours, filtering the solution to remove plant debris and freeze drying to yield a powder (6g). A voucher specimen of the plant material (CA/2012/SW) is deposited in our laboratory.

MC65 cells

MC65 cells are a neuroblastoma line that expresses the C-terminal fragment of amyloid precursor protein (APP CTF) under the control of a tetracycline responsive promoter [34, 43]. Following tetracycline withdrawal from the medium, endogenous Aβ accumulates and cell death occurs within 72 hours. MC65 cells were cultured in MEMα supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco), 2mM L-glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.1% tetracycline (Sigma-Aldrich) as previously described [44, 45]. For experiments, cells were trypsinized and resuspended in OptiMEM without phenol red (Gibco). Cells were treated with vehicle or the desired concentrations of treatment compounds in the absence of tetracycline. All endpoints were compared to those for tetracycline-treated cells with or without the addition of treatment compounds. For viability studies cells were plated at 15,000 cells/well in 96 well plates and viability was assessed at 72 hours. Cells plated at 60,000/well in 12 well plates or 120,000k/well in 6 well plates were harvested 48h post-treatment to assess gene and protein expression respectively. Gene expression was determined by quantitative real-time PCR and protein expression by western blot.

SH-SY5Y cells

SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. For viability and gene expression experiments cells were plated at 200,000 cells/well in 12-well plates whereas for protein expression they were plated at 400,000 cells/well in 6-well plates. Three days after plating, cells were washed with PBS and switched to serum free DMEM/F12 containing 1% N-2 neuroblastoma growth factor (Gibco) and test compounds. The following day 50μM Aβ25-35 (American Peptide Company) was added to the cells. The 25-35 fragment of full length Aβ is widely used [46-49] has been shown to mediate its toxic effects [50] and therefore was the fragment used in these experiments. Fibrilized Aβ solution was prepared by incubating at 37C for 24h prior to addition to the cell cultures. Two days after the Aβ addition, viability as well as gene and protein expression were assessed.

Cell viability

Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Assays were conducted on 96 well plates with 4-8 wells per treatment condition per plate. The assays was repeated 3-4 times yielding a total of 16-24 replicates per treatment condition.

Western Blotting

Cells were harvested and lysed by sonication and boiling in Laemmli buffer. Samples were separated electrophoretically on an SDS gel, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and immunoblotted using antibodies for total tau (tau12 antibody provided by Skip Binder, Michigan State), pTau Thr205, pTau Ser262, pTau Ser396 and pTau Ser404 (Invitrogen). The optical density of the bands was quantified using Image J software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij) and normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Each blot contained 2-4 samples per treatment condition and densitometric analysis was performed on 4-5 separate blots per experiment.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Cells were harvested and RNA was extracted using Tri-Reagent (Molecular Research Center). RNA was reverse transcribed with the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen) to generate cDNA as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Relative mRNA expression was determined using TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Invitrogen) and commercially available TaqMan primers (Invitrogen) for Tau, encoded by the microtubule associated protein tau (MAPT) gene and GAPDH. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on a StepOne Plus Machine (Applied Biosystems) and analyzed using the delta-delta Ct method. Six replicates were analyzed for each treatment condition.

Chemical analysis of CAW

Identification of the chemical constituents of the CAW extract was initially performed by TLC coupled to HRMS. All HRMS was performed on an AB Sciex Triple TOF 5600 mass spectrometer. CAW extract was applied to silica gel TLC plates (Sigma-Aldrich) and developed using chloroform:methanol:water (15:7:1). Zones separated on the TLC plates were analyzed using a CAMAG commercial TLC-MS direct sampling interface with a flow rate of 0.1 mL/min using MeOH: water (70:30 vol%). Ammonium acetate (50 mM) was added as an ion-pairing reagent. A Shimadzu LC pump was used to deliver solvent to the CAMAG TLC interface connected to the AB Sciex Triple TOF 5600 mass spectrometer and a non-targeted approach was used (Information Dependent Acquisition; IDA). Data were acquired in positive and negative ionization mode. aLC-MS/MS data were acquired over a mass range of m/z 50-1000. with a collision energy of 30 eV -. MS data was imported into the data mining software Peak View (AB SCIEX). Mass detection and ion intensities were compared for the different plant compounds based on accurate mass and MS/MS profiles.

The identities of potential chemical constituents were subsequently confirmed by comparing data from analysis using HPLC coupled to MS (LC-MS) for the extract to that of commercial reference standards (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Chromadex). LC-MS was performed on an Applied Biosystems 4000 Q-trap using a Shimadzu LC pump with an Agilent Extend C18 column (2.1×150mm, 5 μm) eluting with a gradient of acetonitrile in water both with 0.1% formic acid (acetonitrile 5 to 18% in 9 minutes, up to 25% at 20 minutes, then to 95% at 22 minutes, returning to 5% at 22.5 minutes and maintained there until 30 minutes. MS analysis was performed in negative ion mode, with a source temperature of 450°C, and source voltage of 4.5 kV. Mass spectra were acquired utilizing enhanced product ion (EPI) mode in which two experiments were used, the first selecting ions with m/z 515 and the other 353, and collisionally induced dissociation was performed using a collision energy of −30 V.

The percent content of each compound in CAW was assessed by HPLC coupled to UV detection (LC-UV). Commercial reference standards of compounds present in CAW were chromatographed along with the extract. Analysis was performed using an Agilent HPLC system (Thermo) coupled to a Surveyor Photodiode detector (Thermo). A Poroshell 120 EC18 3.0 × 50mm 2.7μ column was used with a column temperature of 60°C and eluting with a gradient of acetontrile in water with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (acetonitrile 5% to 95% in 12 minutes, maintained at 95% at 13 minutes then returning to 5% at 13.5 minutes and maintained there until 15 minutes). Detection wavelengths were 205nm and 330nm. Triterpenes were quantified at 205nm and CQA’s at 330nm.

The positional isomers 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid A could not be resolved by the HPLC conditions described above. A different method was developed specifically to separate these two compounds and quantify their individual percent composition in the CAW extract. HPLC coupled to ultraviolet detection (LC-UV) and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) in series, was performed on an Applied BioSystems 4000 Q TRAP using a Poroshell 120 EC18 3.0 × 50mm 2.7μm column. The column temperature was 40°C and elution was achieved with an acetonitrile:water gradient, containing 0.05% acetic acid (acetonitrile 5% to 25% in 8 minutes, to 40% at 10 minutes, 95% at 11 minutes and maintained at 95% to 12.5 minutes, returning to 5% at 13 minutes and maintained at 5% until 15 minutes). The UV detector was set at 330nm, and MS/MS experiments were conducted with electrospray ionization in negative ion mode, at a temperature of 550°C, with ionspray voltage −4500V, and collision energy of −50V for the m/z (515 to 191) transition, and −30V for the m/z (515 to 353) transition. Compound identities in CAW were confirmed against standards, using both retention time, and relative peak heights obtained by selected reaction monitoring (SRM) of the m/z (515 to 353), and m/z (515 to 191) fragmentation pathways. The two CQA’s were individually quantified from peak areas obtained using UV detection at 330nm.

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined using one- or two-way analysis of variance with appropriate t-tests. Bonferroni post-hoc tests were also conducted. Significance was defined as p ≤0.05. Analyses were performed using Excel or GraphPad Prism 6.

Results

CAW attenuates intracellular Aβ-induced cell death and Aβ-induced changes in tau expression and phosphorylation in MC65 cells

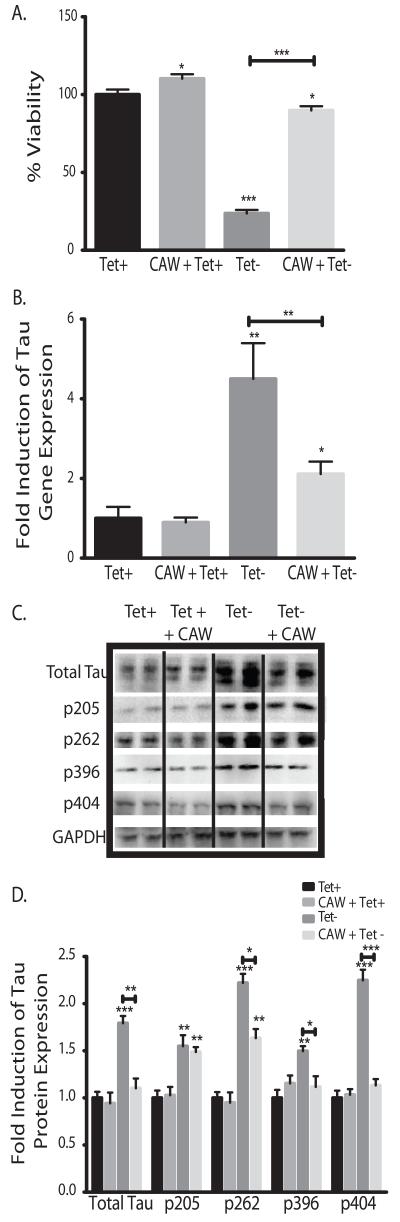

MC65 cells conditionally express human APP-C99 gene under the control of a tetracycline responsive promoter [34]. With tetracycline in the media (Tet+) the gene is repressed but when tetracycline is withdrawn (Tet-) Aβ accumulates and there is extensive cell death within 72 hours [43]. Treatment with 100μg/mL CAW significantly reduced cell death of MC65 cells following tetracycline withdrawal (Figure 1A). Interestingly CAW treatment resulted in a slight, increase in cell viability in the presence of tetracycline as well.

Figure 1.

CAW attenuates the effects of intracellular Aβ toxicity in MC65 cells. *p<0.05, **p<0.1, ***p<0.001 relative to Tet+ unless otherwise indicated. A) The addition of CAW (100ug/mL) significantly reduced cell death observed in cells grown in the absence of tetracycline compared to control-treated cells grown without tetracycline (Tet-), where intracellular Aβ accumulates. Additionally CAW increased cell growth in cells grown with tetracycline (CAW+Tet+) relative to control-treated cells grown with tetracycline (Tet+). n=20-24 per treatment condition. B) Tetracycline withdrawal significantly increased tau gene expression (Tet-) but the addition of CAW (100ug/mL) partially attenuated this effect. n=6-8 per treatment condition. C) Tetracycline withdrawal (Tet-) increased total tau protein expression and tau phosphorylation at various sites. CAW (100ug/mL), added to Tet-treatment, reduced overall tau expression and attenuated the increased phosphorylation at Ser262, Ser396 and Ser404 but had no effect at Thr205. Each immunoblot image is a grouping of representative images from different parts of the same gel. D) Densitometric analysis of 4-5 separate blots per treatment condition. Optical densities were normalized to GAPDH and fold induction is calculated relative to the Tet+ condition.

We also observed that Aβ accumulation increased tau gene expression 4 fold at 48h after tetracycline withdrawal (Figure 1B). This increase was partially attenuated by CAW treatment. The addition of CAW to the cells grown with tetracycline had no effect on tau gene expression.

Tau protein levels mirrored what was observed with the gene expression. Aβ accumulation increased tau protein levels and that induction was also partially attenuated by CAW (Figure 1C). Additionally we observed significant increases in tau phosphorylation at several sites following tetracycline removal. CAW reduced Aβ-induced tau phosphorylation at Ser396 and Ser404 and partially reduced phosphorylation at Ser262. Notably CAW did not affect Aβ-induced tau phosphorylation at Thr205 in MC65 cells nor did CAW treatment have any effect on tau phosphorylation at any site in cells grown with tetracycline. Densitometric analysis of multiple blots confirmed these changes (Figure 1D).

CAW attenuates exogenous Aβ peptide-induced cell death and Aβ peptide-induced changes in tau expression and phosphorylation in SH-SY5Y cells

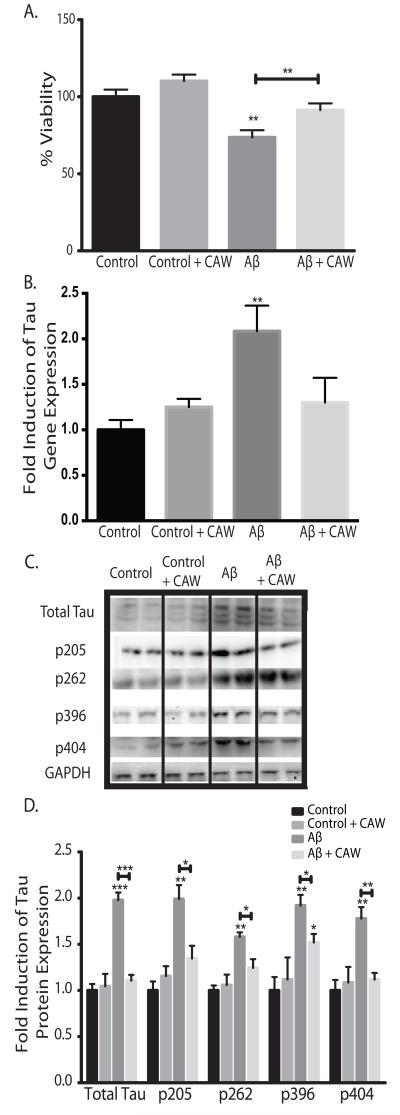

SH-SY5Y cells were treated with CAW for 24h prior to the addition of 50μM Aβ25-35 peptide. Aβ peptide treatment resulted in significant cell death after 48h but pre-treatment with CAW prevented this effect (Figure 2A). In control cells, not treated with Aβ peptide, CAW resulted in a trend towards increased cell viability but this difference was not significant.

Figure 2.

CAW attenuates the effects of extracellular Aβ peptide administration in SH-SY5Y cells. *p<0.05, **p<0.1, ***p<0.001 relative to control unless otherwise indicated. A) Aβ25-35 treatment (50uM) significantly reduced cell viability but this effect was partially attenuated by CAW (100ug/mL). n=16-24 per treatment condition. B) Aβ25-35 treatment (50uM) significantly increased tau gene expression and CAW (100ug/mL) prevented this effect. n=6-8 per treatment condition. C) Aβ25-35 treatment (50uM) also increased tau protein expression and phosphorylation at several sites. CAW (100ug/mL), added to Aβ25-35 treatment, reduced these increases in total tau protein as well as phosphorylation at each site. Each immunoblot image is a grouping of representative images from different parts of the same gel. D) Densitometric analysis of 4-5 separate blots per treatment condition. Optical densities were normalized to GAPDH and fold induction is calculated relative to the control condition.

Exogenous Aβ peptide treatment of SH-SY5Y cells increased tau gene expression 2 fold (Figure 2B). CAW treatment attenuated this increase in Aβ-treated cells to levels that were no different from control cells. However, CAW had no effect on tau expression in control-treated cells. This effect was confirmed at the protein level where CAW completely blocked Aβ-induced increases in tau expression (Figure 2C). Phosphorylation of tau was also increased with Aβ treatment at all of the sites analyzed. CAW prevented this increase at Thr205 and Ser404 and partially attenuated the increased phosphorylation at Ser262 and Ser396. Densitometric analysis of multiple blots confirmed these changes (Figure 2D).

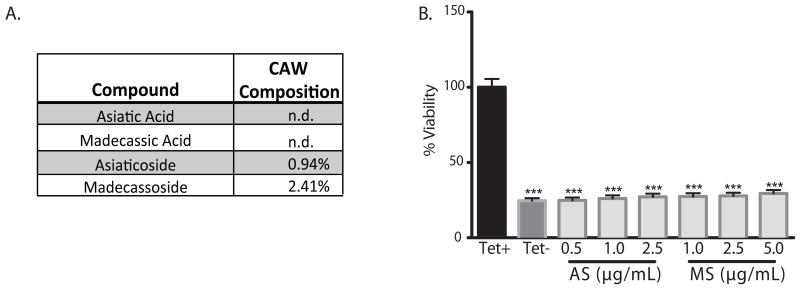

Asiaticoside and madecassoside are present in CAW but show no activity in MC65 cells.

Although the triterpenes asiatic (AA) or madecassic acid (MA) were not found in the CAW extract, non-targeted HRMS detected measurable levels of the triterpene glycosides asiaticoside (AS) and madecassoside (MS). Their percent composition in CAW was determined by LC-UV to be 0.94% for AS and 2.41% for MS (Figure 3A). Because AS and MS were not reported to be present in previous preparations of CAW [18], we wanted to investigate whether the compounds had any protective activity against Aβ toxicity. A dose range was identified for each compound, spanning the concentration that would be present in 100μg/mL CAW. Neither triterpene was protective at any dose tested in the MC65 cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Asiaticoside and madecassoside are present in CAW but not protective against Aβ toxicity in MC65 cells. A) Asiaticoside (AS) and madecassoside (MS) were detected by HRMS and their relative percent composition were determined by HPLC-UV. Asiatic and madecassic acid were not detectable (n.d.) in CAW. B) Dose ranges spanning the concentration of AS and MS present in 100ug/mL CAW were tested in MC65 cells for their ability to attenuate Aβ-induced cell death following tetracycline withdrawal. Neither compound offered any protection at any dose tested; ***p<0.01 relative to Tet+. n=24 per treatment condition.

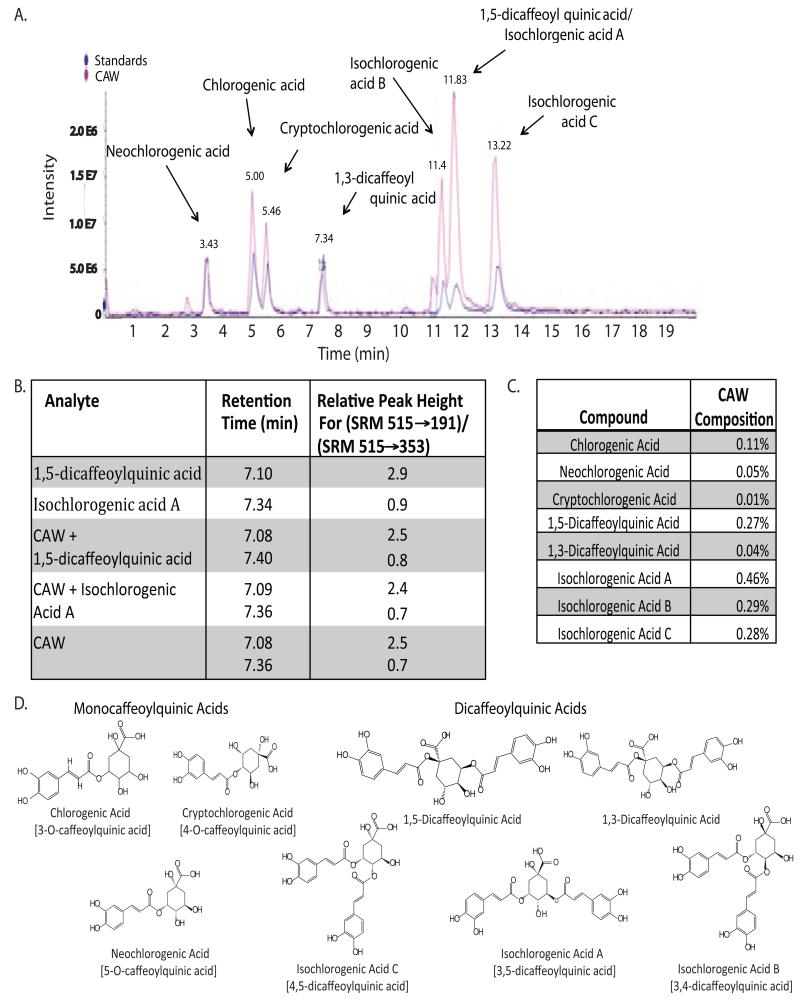

Several caffeoylquinic acids are detectable in CAW extract

Non-targeted TLC-HRMS analysis of the CAW extract identified several compounds with masses and fragmentation patterns typical of caffeoylquinic acids (CQAs). When run on LC-MS, with available standards, we were able to confirm the presence of 8 specific CQAs in CAW (Figure 4A). We achieved good resolution between most of the CQAs but 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid A co-eluted and had identical masses. However, we were able to resolve these two compounds using a modified LC-MS/MS method. The two compounds not only had differing retention times, but under appropriate MS/MS conditions, showed differences in the relative intensities of the m/z (515 to 353) and m/z (515 to 191) transitions. Differences in the relative intensities for these fragment ions were also noted for other dicaffeoylquinic acids. The relative peak height for each component was obtained by dividing the peak height in chromatograms obtained by SRM of the 515/191 transition by the peak height in chromatograms obtained by SRM of the 515/353 transition. Using selective reaction monitoring (SRM) to compare standard compounds alone, CAW, and CAW spiked with standards, we verified that both 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid A were present in CAW (Figure 4B). Peak height ratios for 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid A in CAW, may have been modified by interference from Isochlorogenic acid B, which eluted between these two compounds.

Figure 4.

Caffeoylquinic acids are present in CAW. A) The presence of several caffeoylquinic acids was confirmed by comparing the LC-MS trace for CAW to that of a solution containing standards for each CQA. B) The relative peak heights obtained by selected reaction monitoring (SRM) of the 535 to 191, and 515 to 353 transitions using LC-MS/MS differed for the isomeric dicaffeoylquinic acids. This was used to verify the presence of 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and Isochlorogenic acid A in CAW. C) The % composition of each CQA in the CAW mixture was determined from LC-UV analysis at 330nm. D) The chemical structures of the eight CQAs comprising both monocaffeoylquinic and dicaffeoylquinic acids. The chemical nomenclature is given in brackets when the common name was used.

Quantitation of CQA’s in CAW

The percent content of each CQA in CAW extract was determined by HPLC-UV, with detection at 330nm (Figure 4C). There was a wide range in percent composition from 0.01% to 0.47% with isochlorogenic acid A being the most abundant. Isochlorogenic acids B and C and 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid also contributed significantly to the CAW mixture accounting for approximately 0.27-0.28%. Each of the other CQAs analyzed accounted for less than or equal to 0.11% of CAW.

Dicaffeoylquinic acids provide greater protection against intracellular Aβ-induced cell death in MC65 cells than do monocaffeoylquinic acids

The structures of the CQAs identified separate them into two classes, monocaffeoyl quinic acids which include chlorogenic, cryptochlorogenic and neochlorogenic acids and the dicaffeoylquinic acids including isochlorogenic acids A, B and C as well as 1,5 and 1,3 dicaffeoylquinic acids (Figure 4D). The activity of each of the CQAs was assessed using the MC65 cells. A dose range was used for each compound that spanned its concentration in a 100μg/mL solution of CAW, calculated by the percent composition determined by HPLC. None of the monocaffeoylquinic acids showed any significant protection above the no treatment (Tet-) condition (Figure 5A) at any of the concentrations tested in the range relevant to their concentration in CAW. In contrast, the dicaffeoylquinic acids did significantly improve viability especially at the higher doses tested.

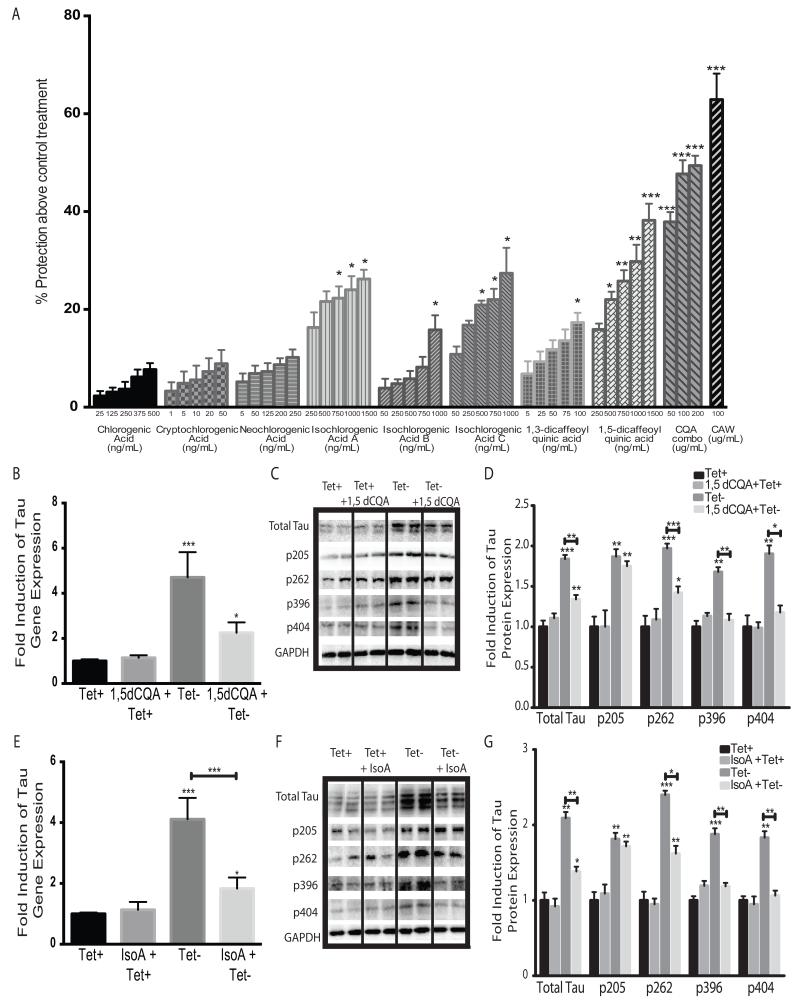

Figure 5.

Dicaffeoylquinic acids show activity in reversing the effects of Aβ accumulation in MC65 cells. A) The neuroprotective effects of each CQA were evaluated in MC65 cells grown without tetracycline. Each CQA was tested at a dose range spanning its calculated concentration in 100ug/mL CAW. A combination of all eight CQAs (CQA combo) was also prepared with each CQA at its expected concentration in 50, 100 or 200ug/mL CAW. Protection above the viability of the cells grown without tetracycline was determined; *p<0.05, **p<0.1, ***p<0.001 relative to cells grown without tetracycline (Tet- condition). n=16-24 per treatment condition. B) Treatment with 750ng/mL 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid (1,5-dCQA) significantly attenuated the increase in tau gene expression caused by tetracycline withdrawal; n=6 per treatment condition; *p<0.05, **p<0.1, ***p<0.001 relative to Tet+ unless otherwise indicated for figures 5B-5G. C) 1,5-dCQA (750ng/mL) also diminished the increased tau protein levels and phosphorylation at Ser262, Ser396 and Ser404 that resulted from tetracycline withdrawal. Each immunoblot image is a grouping of representative images from different parts of the same gel. D) Densitometric analysis of 4-5 separate blots per treatment condition. Optical densities were normalized to GAPDH and fold induction is calculated relative to the control condition. E) Treatment with 750ng/mL isochlorogenic acid A (IsoA) significantly reduced the induction of tau gene expression caused by tetracycline removal (Tet-). n=6 per treatment condition. F) IsoA (750ng/mL) similarly decreased tau protein expression and phosphorylation at Ser262, Ser396 and Ser404 caused by tetracycline withdrawal. Each immunoblot image is a grouping of representative images from different parts of the same gel. G) Densitometric analysis of 4-5 separate blots per treatment condition. Optical densities were normalized to GAPDH and fold induction is calculated relative to the control condition.

Combinations of all 8 CQAs reflecting their relative percent composition equivalent to 50, 100 and 200 μg/mL CAW were also tested in MC65 cells. There was robust protection at each of the doses equivalent to 50, 100 and 200 μg/mL CAW, and the CQA combinations offered greater protection than any dose of the individual CQAs. However, the CQA combinations did not achieve as great a level of protection as was observed using 100μg/mL of the complete CAW extract. The combination equivalent to 100μg/ml CAW achieved only 76% of the protective activity observed when using the whole extract.

1,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid A attenuate Aβ-induced changes in tau expression and phosphorylation in MC65 cells

Because 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid A were the most abundant and most active of the individual CQAs in the viability screen, we further confirmed their activity by evaluating their effects on tau expression and phosphorylation. As observed with CAW, 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid (750μg/mL) significantly reduced tau gene expression following tetracycline removal although it did not return expression back to control levels (Figure 5B). Again, as was observed with CAW, this effect was limited to cells grown without tetracycline. Tau protein expression was likewise increased by Aβ accumulation and was partially attenuated with1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid treatment (Figure 5C). The Aβ-induced increases in tau phosphorylation were attenuated by 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid at all sites except thr205, consistent with what was observed with the entire extract in MC65 cells. Densitometric analysis of multiple blots confirmed these changes (Figure 5D).

Isochlorogenic acid A (750μg/mL) had an overall similar effect on tau gene and protein expression as did 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid. It partially attenuated Aβ-induced increases in tau gene expression but not to the levels seen in cells grown in the presence of tetracycline but had no effect on tau gene expression in cells grown with tetracycline (Figure 5E). These effects on tau expression were confirmed at the protein level (Figure 5F). Isochlorogenic acid A normalized the Aβ-induced phosphorylation at Ser396 and Ser404 and partially attenuated increased phosphorylation at Ser262 resulting from Aβ accumulation. Isochlorogenic acid A had no effect on the Aβ-induced phosphorylation at Thr205 nor did it affect phosphorylation at any site in the presence of tetracycline. Densitometric analysis of multiple blots confirmed these changes (Figure 5G).

1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid A attenuate Aβ peptide-induced changes in tau expression and phosphorylation in SH-SY5Y cells

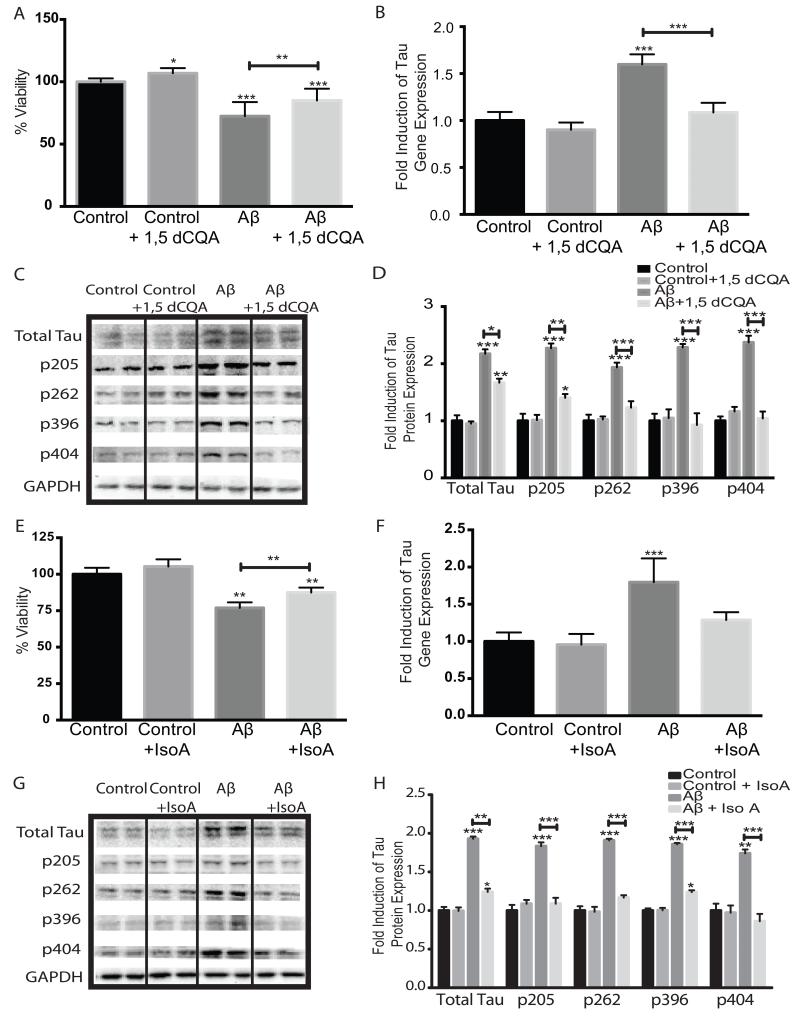

The activities of 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid A were further confirmed in the SH-SY5Y cell model system. Cells were treated with either 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid (750μg/mL) or isochlorogenic acid A (750μg/mL) 24h prior to the addition of 50μM Aβ25-35 peptide. 1,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid partially attenuated the cytotoxic effect of Aβ in peptide-treated cultures, and significantly increased cell growth in control cells as well (Figure 6A). 1,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid also normalized Aβ peptide-induced tau gene expression though it had no effect on tau expression in control cells (Figure 6B). The increased protein levels of tau caused by Aβ peptide administration were partially attenuated by 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid treatment although they were still significantly increased relative to control cells. Treatment with 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid also significantly attenuated Aβ peptide-induced increases in tau phosphorylation at all sites, although phosphorylation at Thr205 remained elevated compared to controls. Again, 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid treatment had no effect on tau protein expression or phosphorylation in control cells (Figure 6C). Densitometric analysis of multiple blots confirmed these changes (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

1,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid A attenuate the effects of Aβ25-35 administration in SH-SY5Y cells. *p<0.05, **p<0.1, ***p<0.001 relative to control unless otherwise indicated. A) 1,5dCQA (750ng/mL) reduced the cell death induced by Aβ peptide administration (50uM) and also increased cell growth in control-treated cells, n=16-24 per treatment condition. B) 1,5dCQA (705ng/mL) prevented the increase in tau gene expression caused by Aβ peptide (50uM), n=6 per treatment condition. C) 1,5dCQA (750ng/mL), when combined with Aβ peptide (50uM), also attenuated the increases in total tau protein as well as tau phosphorylation at all sites analyzed. Each immunoblot image is a grouping of representative images from different parts of the same gel. D) Densitometric analysis of 4-5 separate blots per treatment condition. Optical densities were normalized to GAPDH and fold induction is calculated relative to the control condition. E) IsoA (750ng/mL) attenuated the cytotoxicity induced by Aβ peptide treatment (50uM). n=16-24 per treatment condition F) IsoA (750ng/mL) blocked the Aβ peptide (50uM) induced increase in tau gene expression. n=6 per treatment condition. G) IsoA (750ng/mL), when combined with Aβ peptide (50uM), also reduced the increases in tau protein expression and phosphorylation induced by Aβ peptide (50uM) alone. H) Densitometric analysis of 4-5 separate blots per treatment condition. Optical densities were normalized to GAPDH and fold induction is calculated relative to the control condition.

Isochlorogenic acid A also partially prevented the cell death induced by Aβ peptide addition and there was a trend toward increased cell viability in control treated cells although it did not reach statistical significance (Figure 6E). Isochlorogenic acid A also significantly reduced Aβ peptide-induced increases in tau gene (Figure 6F) and protein expression although it did not return protein levels completely back to those observed in control cells (Figure 6G). Isochlorogenic acid A also partially attenuated increases in tau phosphorylation at Ser262 and Ser396 caused by Aβ peptide and protected against Aβ peptide-induced increases in phosphorylation at Thr205 and Ser404 completely. Consistent with what was observed for the CAW extract and 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid treatment, addition of isochlorogenic acid A had no effect on tau expression or phosphorlylation in control cells. Densitometric analysis of multiple blots confirmed these changes (Figure 6H).

Discussion

We have previously reported that two weeks of CAW treatment reverses cognitive defects in animal model of Aβ toxicity [18]. Here we show that, CAW protects against Aβ induced cytotoxicity in two cellular models, the MC65 and SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cell lines. MC65 cells overexpress APP under the control of a tetracycline responsive promoter. The withdrawal of tetracycline induces the expression of APP and its subsequent processing to Aβ leading to Aβ accumulation and ultimately cell death[43]. SH-SY5Y cells are a model system frequently used to assess the effects of Aβ peptide, particularly the Aβ25-35 fragment [46-49] as it has been shown to mediate the toxic effects of Aβ[50]. While these systems do not perfectly model the in vivo biology of AD, they do recapitulate the effects of both endogenous and exogenous Aβ and therefore allow for the study of its toxic consequences.

Using these cellular models, we also observed that CAW attenuates Aβ induced changes in tau expression and phosphorylation in both SH-SY5Y and MC65 cells. While Aβ has previously been shown to induce tau phorphorylation in SH-SY5Y cells [51-53], to our knowledge this is the first report of Aβ-induced alterations in tau in the MC65 cell line. Tau is a cytoskeletal protein normally bound to microtubules. When it becomes hyperphosphorylated tau dissociates from the microtubules and can aggregate generating neurofibrillary tangles [2]. The phosphorylation sites investigated in this study are all abnormally phosphorylated in AD [54], making them potentially relevant to disease pathology. However, because multiple kinases are known to phosphorylate each of these sites [55], it is unclear which, if any, of them CAW might affect. However, the fact that CAW treatment did not alter tau phosphorylation in control or Tet+ treated cells suggests that a direct effect of CAW on kinase activity is unlikely. Each of these sites can also be dephosphorylated by phosphoseryl/phosphothreonyl protein phosphatase-2A (PP-2A) [54] which is one of the most active enzymes in dephosphorylating abnormal tau [56, 57]. Both the expression and activity of this enzyme is known to be decreased in AD brains [58-60]. Therefore the possibility exists that CAW treatment might promote the expression or activation of PP-2A, although this remains to be determined.

Additionally, further investigation is needed to understand if these changes in tau expression and phosphorylation are relevant to the mechanism of Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in these cell lines. No significant tau aggregation or tangles appear in either the MC65 or SHSY5Y cells prior to Aβ-induced cell death nor are there reports of tangles in the Tg2576 mice, where we previously observed the cognitive enhancing effects of CAW. Thus it may be the case that these alterations in tau are merely a marker for, and not mechanistically linked to, Aβ toxicity in these cell lines.

The neuroprotective effects of Centella asiatica have been well documented [20, 61-64], yet these effects have usually been attributed to the bioactive triterpenes (asiatic acid, madecassic acid, asiaticoside, madacassoside) present in the plant. We previously reported that our original extract of CAW does not contain these triterpenes [18]. Interestingly our analysis of the CAW preparation used in the present study did show the presence of asiaticoside and madecassoside. This apparent inconsistency is likely due to the fact that a different collection of Centella asiatica was used in the present experiments. As previously mentioned, plant material from a single species can be highly variable in phytochemical composition depending on genetic factors, and conditions of growth and collection [16, 17]. Variability has been shown between different accessions of Centella asiatica, even those grown within relatively narrow geographical regions [14, 65]. While the presence of the triterpenes in this preparation was unexpected, based on our assay in MC65 cells they appear to have no activity against Aβ-induced toxicity. This, combined with the fact that these compounds were not present in the previous CAW extract that showed beneficial effects in mouse model [18], leads us to conclude that the triterpenes are not responsible for the neuroprotective activity of CAW against Aβ-induced toxicity.

Instead we have identified several caffeoylquinic acids that show neuroprotective activity against both intracellular and extracellular Aβ-toxicity. Some of the CQAs we found in CAW have been previously described in Centella asiatica but not in a water extract specifically. Chlorogenic acid, cryptochlorogenic acid, neochlorogenic acid and isochlorogenic acids A and B were all identified in an alcohol extract of Centella asiatica [14]. Here we also confirm the presence of 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 1,3 dicaffeoylquinic acid and isochlorogenic acid C in CAW. These compounds have not previously been associated with the neuroprotective activities of Centella asiatica, although there have been studies reporting antioxidant components, potentially phenolic in nature [65, 66] in this plant.

CQAs are found in many types of plants and have been shown to have neuroprotective effects in several model systems. In primary rat neurons CQAs were protective against excitotoxic and hypoxic damage [67] and prevented H202-induced apoptosis [68]. CQAs also protected against Aβ1-42 toxicity in primary neurons [69] and in vivo were shown to inhibit microglial activation and protect neurons during focal cerebral ischemia [70].

Additionally CQAs inhibited Aβ1-42 aggregation in vitro and isochlorogenic acid C was protective against Aβ1-42 induced cell death in SH-SY5Y cells [71]. Interestingly 3,4,5 tricaffeoylquinic acid was found to be an even more potent inhibitor of Aβ1-42 induced cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells than the dicaffeoylquinic acids [72] suggesting that an increased number of caffeoyl groups on the quinic acid moiety may result in increased neuroprotection. This is consistent with our finding that monocaffeoylquinic acids offered less protection from Aβ-induced cell death in the MC65 cells than did the dicaffeoylquinic acids.

It remains to be seen if the bioactive CQAs identified in this in vitro study are what mediate the in vivo cognitive enhancing effects of CAW that we previously observed in Tg2576 mice [18]. Both isochlorogenic acid A and a CQA-rich sweet potato extracts have been shown to improve cognition in senescence accelerated-prone mice [73, 74] but the effects of CQAs in the Tg2576 model of Aβ toxicity have yet to be investigated.

It will also be interesting to evaluate the effects of both CAW and the CQA compounds in healthy, aged mice. Our in vitro data shows that while there is a robust effect of CAW and the CQAs when either intracellular Aβ accumulates or Aβ peptide is administered exogenously, the effect of CAW under control conditions is modest and restricted to viability. It is therefore difficult to speculate whether or not the extract, or isolated compounds from the extract, would display any cognitive enhancing effects in vivo in the absence of Aβ pathology.

The eight CQAs evaluated here are not a comprehensive list of CQAs present in CAW extract. We were unable to get standards for some CQAs previously reported to be present in Centella asiatica, and also detected by HRMS in our CAW extract, such as irbic acid [14]. Also, it is possible that the CQAs do not represent the entirety of active compounds in CAW. HRMS analysis revealed that CAW is a complex mixture of which all the CQAs we identified account for less than 1.5%. Additionally the combination of CQAs equivalent to their abundance in 100ug/mL CAW did not reach the same level of protection in MC65 cells as the entire extract, suggesting that other compounds in CAW contribute to its ability to prevent Aβ-toxicity. More analysis, either by untargeted HRMS or by bioactivity-guided fractionation, is needed to fully elucidate all the active constituents of CAW.

The data presented here clearly show the neuroprotective effects of CAW in two in vitro models of Aβ toxicity, and identify CQAs as active components of that extract. These CQAs can be used as marker compounds in future studies to determine the bioavailability of CAW and will help identify a therapeutic window for dosing in future animal or human studies. Bioavailability studies will also allow us to evaluate the relevance of the CAW and CQA doses used in these in vitro experiments. Additionally, current standardization of Centella asiatica extracts focuses on measuring the triterpenes. This study demonstrates that the CQA’s may also be relevant therapeutically, and that their content should also be optimized.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by grants awarded to A. Soumyanath and N. Gray from the Oregon Alzheimer’s Disease Center (NIH-NIA 5 P30 AG008017 24), a T32 grant (NIH-NCCAM AT002688) on which N. Gray is a trainee and by a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review grant awarded to J. Quinn. HPLC and LC-MS work was supported by the Bio-Analytical Shared Resource/Pharmacokinetics Core in the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology at Oregon Health & Science University. The authors also acknowledge the Biomolecular Mass Spectrometry Core of the Environmental Health Sciences Core Center at Oregon State University (NIH grant P30ES000210) for LC-HRMS and LC- MS analyses (NIH grant S10RR027878).

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R, J.E., Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(3):186–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maccioni RB, M.J.a.B.L. The molecular bases of Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders, Archives of Medical Research. 2001;32(5):367–381. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(01)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braak H, Z.H., Del Tredici K, Blennow K. Intraneuronal tau aggregation precedes diffuse plaque deposition, but amyloid-β changes occur before increases of tau in cerebrospinal fluid. Acta Neuropathol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1139-0. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanger DP, A.B., Noble W. Tau phosphorylation: the therapeutic challenge for neurodegenerative disease. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(3):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park SS, J.H., Kim YJ, Park TK, Kim C, Choi H, Mook-Jung IH, Koo EH, Park SA. Asp664 cleavage of amyloid precursor protein induces tau phosphorylation by decreasing protein phosphatase 2A activity. J Neurochem. 2012;123(5):856–65. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tokutake T, K.K., Yajima R, Sekine Y, Tezuka T, Nishizawa M, Ikeuchi T. Hyperphosphorylation of Tau induced by naturally secreted amyloid-β at nanomolar concentrations is modulated by insulin-dependent Akt-GSK3β signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(42):35222–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.348300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Z, Z.R., Qi J, Wen S, Tang Y, Wang D. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β by Angelica sinensis extract decreases β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity and tau phosphorylation in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89(3):437–47. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ott S, H.A., Henkel MK, Redzic ZB, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J. Pre-aggregated Aβ1-42 peptide increases tau aggregation and hyperphosphorylationafter short-term application. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2011;349(1-2):169–77. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0671-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Media Announcement, E.L. Eli Lilly and Company Announces Top-Line Results on Solanezumab Phase 3 Clinical Trials in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. 2012 Available from: http://newsroom.lilly.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=702211%3E.

- 10.Wasilewski A. Johnson & Johnson Announces Discontinuation Of Phase 3 Development of Bapineuzumab Intravenous (IV) In Mild-To-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. 2012 [cited 2012 October 22]; Available from: < http://www.jnj.com/connect/news/all/johnson-and-johnson-announces-discontinuation-of-phase-3-development-of-bapineuzumab-intravenous-iv-in-mild-to-moderate-alzheimers-disease%3E.

- 11.Flaherty JH, T.R., Teoh J, Kim JI, Habib S, Ito M, Matsushita S. Use of alternative therapies in older outpatients in the United States and Japan: prevalence, reporting patterns, and perceived effectiveness. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(10):M650–5. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.m650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Astin JA, P.K., Marie A, Haskell WL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among elderly persons: one-year analysis of a Blue Shield Medicare supplement. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(1):M4–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.1.m4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shinomol GK, M. Effect of Centella asiatica leaf powder on oxidative markers in brain regions of prepubertal mice in vivo and its in vitro efficacy to ameliorate 3-NPA-induced oxidative stress in mitochondria. Phytomedicine. 2008;15(11):971–84. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long HS, Stander MA, Van Wyk B. Notes on the occurrence and significance of triterpenoids (asiaticoside and related compounds) and caffeoylquinic acids in Centella species. South African Journal of Botany. 2012;82:53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinkhaus B, L.M., Schuppan D, Hahn EG. Chemical, pharmacological and clinical profile of the East Asian medical plant Centella asiatica. phytomedicine. 2000;7(5):427–48. doi: 10.1016/s0944-7113(00)80065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betz JM, Brown PN, Roman MC. Accuracy, precision, and reliability of chemical measurements in natural products research. Fitoterapia. 2011;82(1):44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Govindaraghavan S. Quality assurance of herbal raw materials in supply chain: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 2008;5(2):176–212. doi: 10.1080/19390210802332810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soumyanath A, Z.Y., Henson E, Wadsworth T, Bishop J, Gold BG, Quinn JF. Centella asiatica Extract Improves Behavioral Deficits in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease: Investigation of a Possible Mechanism of Action. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012:381974. doi: 10.1155/2012/381974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tabassum R, V.K., Shrivastava P, Khan A, Ejaz Ahmed M, Javed H, Islam F, Ahmad S, Saeed Siddiqui M, Safhi MM, Islam F. Centella asiatica attenuates the neurobehavioral, neurochemical and histological changes in transient focal middle cerebral artery occlusion rats. Neurol Sci. 2013;34(6):925–33. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soumyanath A, Zhong YP, Gold SA, Yu X, Koop DR, Bourdette D, Gold BG. Centella asiatica accelerates nerve regeneration upon oral administration and contains multiple active fractions increasing neurite elongation in-vitro. Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmacology. 2005;57(9):1221–1229. doi: 10.1211/jpp.57.9.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haleagrahara N, P.K. Neuroprotective effect of Centella asiatica extract (CAE) on experimentally induced parkinsonism in aged Sprague-Dawley rats. J Toxicol Scie. 2010;35(1):41–47. doi: 10.2131/jts.35.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta R, F.S. Effect of Centella asiatica on arsenic induced oxidative stress and mental distribution in rats. J Appl Toxicol. 2006;26(3):213–22. doi: 10.1002/jat.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo JS, C.C., Koo MW. Inhibitory effects of Centella asiatica water extract and asiaticoside on inducible nitric oxide synthase during gastric ulcer healing in rats. Planta Med. 2004;70(12):1150–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-835843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohandas Rao KG, M.R.S., Gurumadhva Rao S. Enhancement of Amygdaloid Neuronal Dendritic Arborization by Fresh Leaf Juice of Centella asiatica (Linn) During Growth Spurt Period in Rats. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2009;6(2):203–10. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Veerendra Kumar MH, G.Y. Effect of Centella asiatica on cognition and oxidative stress in an intracerebroventricular streptozotocin model of Alzheimer’s disease in rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2003;30(5-6):336–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2003.03842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta YK, V.K.M., Srivastava AK. Effect of Centella asiatica on pentylenetetrazole-induced kindling, cognition and oxidative stress in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;74(3):579–85. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dev RDO, Mohamed S, Hambali Z, Samah BA. Comparison on cognitive effects of Centella asiatica in healthy middle aged female and male volunteers. European Journal of Scientific Research. 2009;31(4):553–565. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Appa Rao MVR, Srinivasan K, Koteswara Rao T. The effect of Mandookaparni (Centella asiatica) on the general mental ability (medhya) of mentally retarded children. Journal of Research in Indian Medicine. 1973;8:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tiwari S, Singh S, Patwardhan K, Gehlot S, Gambhir IS. Effect of Centella asiatica on mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and other common age-related clinical problems. Digest Journal of Nanomaterials and Biostructures. 2008;3(4):215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wattanathorn J, Mator L, Muchimapura S, Tongun T, Pasuriwong O, Piyawatkul N, Yimtae K, Sripanidkulchai B, Singkhoraard J. Positive modulation of cognition and mood in the healthy elderly volunteer following the administration of Centella asiatica. Journal of ethnopharmacology. 2008;116(2):325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhanasekaran M, H.L., Hitt AR, Tharakan B, Porter JW, Young KA, Manyam BV. Centella asiatica extract selectively decreases amyloid beta levels in hippocampus of Alzheimer’s disease animal model. Phytother Res. 2009;23(1):9–14. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsiao K. Transgenic mice expressing Alzheimer amyloid precursor proteins. Exp Gerontol. 1998;33(7-8):883–9. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James JT, D.I. Pentacyclic triterpenoids from the medicinal herb, Centella asiatica (L.) Urban. Molecules. 2009;14(10):3922–3941. doi: 10.3390/molecules14103922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sopher BL, F.K., Kavanagh TJ, Furlong CE, Martin GM. Neurodegenerative mechanisms in Alzheimer disease. A role for oxidative damage in amyloid beta protein precursor-mediated cell death. Mol Chem Neuropathol. 1996;29(2-3):153–68. doi: 10.1007/BF02814999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shahnawaz M, S.M., Shin SY, Park IS. Wild-type, Flemish, and Dutch amyloid-β exhibit different cytotoxicities depending on Aβ40 to Aβ42 interaction time and concentration ratio. J Pept Sci. 2013;19(9):545–53. doi: 10.1002/psc.2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Q, Y.X., Patal K, Hu R, Chuang S, Zhang G, Zheng J, Wang Q, Yu X, Patal K, Hu R, Chuang S, Zhang G, Zheng J. Tanshinones inhibit amyloid aggregation by amyloid-β peptide, disaggregate amyloid fibrils, and protect cultured cells. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4(6):1004–15. doi: 10.1021/cn400051e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee C, P.G., Lee SR, Jang JH. Attenuation of β-amyloid-induced oxidative cell death by sulforaphane via activation of NF-E2-related factor 2. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:313510. doi: 10.1155/2013/313510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bang OY, H.H., Kim DH, Kim H, Boo JH, Huh K, Mook-Jung I. Neuroprotective effect of genistein against beta amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16(1):21–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei W, N.D., Wang X, Kusiak JW. Abeta 17-42 in Alzheimer’s disease activates JNK and caspase-8 leading to neuronal apoptosis. Brain. 2002;125(9):2036–43. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wei W, W.X., Kusiak JW. Signaling events in amyloid beta-peptide-induced neuronal death and insulin-like growth factor I protection. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(20):17649–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111704200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Agnaf OM, M.D., Patel BP, Austen BM. Oligomerization and toxicity of beta-amyloid-42 implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273(3):1003–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wagner H. Plant drug analysis. A thin-layer chromatographic atlas. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sopher BL, F.K., Smith AC, Leppig KA, Furlong CE, Martin GM. Cytotoxicity mediated by conditional expression of a carboxyl-terminal derivative of the beta-amyloid precursor protein. Brain Res Mol. 1994;26(1-2):207–17. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woltjer RL, M.I., Ou JJ, Montine KS, Montine TJ. Advanced glycation endproduct precursor alters intracellular amyloid-β/AβPP carboxy-terminal fragment aggregation and cytotoxicity. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2006;5(6):467–76. doi: 10.3233/jad-2003-5607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woltjer RL, M.W., Milatovic D, Kjerulf JD, Shie FS, Rung LG, Montine KS, Montine TJ. Effects of chemical chaperones on oxidative stress and detergent-insoluble species formation following conditional expression of amyloid precursor protein carboxy-terminal fragment. Neurobiology of Disease. 2007;25(2):427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen TF, T.M., Chou CH, Chiu MJ, Huang RF. Dose-dependent folic acid and memantine treatments promote synergistic or additive protection against Aβ<sub>(25-35)</sub> peptide-induced apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells mediated by mitochondria stress-associated death signals. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;62C:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee C, P.G., Lee SR, Jang JH. Attenuation of β-amyloid-induced oxidative cell death by sulforaphane via activation of NF-E2-related factor 2. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:313510. doi: 10.1155/2013/313510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu WS, Z.Y., Shi ZH, Chang SY, Nie GJ, Duan XL, Zhao SM, Wu Q, Yang ZL, Zhao BL, Chang YZ. Mitochondrial ferritin attenuates β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity: reduction in oxidative damage through the Erk/P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(2):158–69. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mantha AK, D.M., Taglialatela G, Perez-Polo RJ, Mitra S. Proteomic study of amyloid beta (25-35) peptide exposure to neuronal cells: Impact on APE1/Ref-1’s protein-protein interaction. J Neurosci Res. 2012;90(6):1230–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yankner BA, D.L., Kirschner DA. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid beta protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science. 1990;250(4978):279–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2218531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang HC, T.D., Xu K, Jiang ZF. Curcumin attenuates amyloid-β-induced tau hyperphosphorylation in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells involving PTEN/Akt/GSK-3β signaling pathway. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2013 doi: 10.3109/10799893.2013.848891. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang S, Z.Y., Xu L, Lin X, Lu J, Di Q, Shi J, Xu J. Indirubin-3′-monoxime inhibits beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neurosci Lett. 2009;450(2):142–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Datki Z, P.R., Zádori D, Soós K, Fülöp L, Juhász A, Laskay G, Hetényi C, Mihalik E, Zarándi M, Penke B. In vitro model of neurotoxicity of Abeta 1-42 and neuroprotection by a pentapeptide: irreversible events during the first hour. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17(3):507–15. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang JZ, G.-I.I., Iqbal K. Kinases and phosphatases and tau sites involved in Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(1):59–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin L, L.X., Wilson CM, Magnaudeix A, Perrin ML, Yardin C, Terro F. Tau protein kinases: involvement in Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(1):289–309. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang JZ, G.C., Zaidi T, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Dephosphorylation of Alzheimer paired helical filaments by protein phosphatase-2A and -2B. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(9):4854–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang JZ, G.-I.I., Iqbal K. Restoration of biological activity of Alzheimer abnormally phosphorylated tau by dephosphorylation with protein phosphatase-2A, -2B and -1. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1996;38(2):200–8. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00316-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gong CX, S.T., Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Phosphoprotein phosphatase activities in Alzheimer disease brain. 1993;3:921–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03603.x. 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gong CX, S.S., Wang JZ, Zaidi T, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Phosphatase activity toward abnormally phosphorylated tau: decrease in Alzheimer disease brain. J Neurochem. 1995;65(2):732–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65020732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vogelsberg-Ragaglia V, S.T., Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. PP2A mRNA expression is quantitatively decreased in Alzheimer’s disease hippocampus. Exp Neurol. 2001;168(2):402–12. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wanakhachornkrai O, P.V., Chunhacha P, Wanasuntronwong A, Vattanajun A, Tantisira B, Chanvorachote P, Tantisira MH. Neuritogenic effect of standardized extract of Centella asiatica ECa233 on human neuroblastoma cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13(1):204. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu MF, X.Y., Liu JK, Qian JJ, Zhu L, Gao J. Asiatic acid, a pentacyclic triterpene in Centella asiatica, attenuates glutamate-induced cognitive deficits in mice and apoptosis in SH-SY5Y cells. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33(5):578–87. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang X, W.J., Dou Y, Xia B, Rong W, Rimbach G, Lou Y. Asiatic acid protects primary neurons against C2-ceramide-induced apoptosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;679(1-3):51–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.G V, K.S., V L, Rajendra W. The antiepileptic effect of Centella asiatica on the activities of Na/K, Mg and Ca-ATPases in rat brain during pentylenetetrazol-induced epilepsy. Indian J Pharmacol. 2010;42(2):82–6. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.64504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Upadhyaya S, Saikia LR. Evaluation of phytochemicals, antioxidant activity and nutrient content of Centella asiatica (L.) urban leaves from different localities of Assam. International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences. 2012;3(4):656–663. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zainol MK, A.-H.A., Yusof S, Muse R. Antioxidative activity and total phenolic compounds of leaf, root and petiole of four accessions of Centella asiatica (L.) Urban. Food Chem. 2003;81:575–581. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim JY, L.H., Hwang BY, Kim S, Yoo JK, Seong YH. Neuroprotection of Ilex latifolia and caffeoylquinic acid derivatives against excitotoxic and hypoxic damage of cultured rat cortical neurons. Arch Pharm Res. 2012;35(6):1115–22. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-0620-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim J, L.S., Shim J, Kim HW, Kim J, Jang YJ, Yang H, Park J, Choi SH, Yoon JH, Lee KW, Lee HJ. Caffeinated coffee, decaffeinated coffee, and the phenolic phytochemical chlorogenic acid up-regulate NQO1 expression and prevent H2O2-induced apoptosis in primary cortical neurons. Neurochem Int. 2012;60(5):466–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Xiao HB, C.X., Wang L, Run XQ, Su Y, Tian C, Sun SG, Liang ZH. 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid protects primary neurons from amyloid β 1-42-induced apoptosis via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Chin Med J (Engl) 2011;124(17):2628–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang SX, G.H., Hu LM, Liu YN, Wang YF, Kang LY, Gao XM. Caffeic acid ester fraction from Erigeron breviscapus inhibits microglial activation and provides neuroprotection. Chin J Integr Med. 2012;18(6):437–44. doi: 10.1007/s11655-012-1114-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miyamae Y, K.M., Murakami K, Han J, Isoda H, Irie K, Shigemori H. Protective effects of caffeoylquinic acids on the aggregation and neurotoxicity of the 42-residue amyloid β-protein. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20(19):5844–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Miyamae Y, H.J., Sasaki K, Terakawa M, Isoda H, Shigemori H. 3,4,5-tri-O-caffeoylquinic acid inhibits amyloid β-mediated cellular toxicity on SH-SY5Y cells through the upregulation of PGAM1 and G3PDH. Cytotechnology. 2011;63(2):191–200. doi: 10.1007/s10616-011-9341-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sasaki K, H.J., Shimozono H, Villareal MO, Isoda H. Caffeoylquinic acid-rich purple sweet potato extract, with or without anthocyanin, imparts neuroprotection and contributes to the improvement of spatial learning and memory of SAMP8 mouse. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(21):5037–45. doi: 10.1021/jf3041484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Han J, M.Y., Shigemori H, Isoda H. Neuroprotective effect of 3,5-di-O-caffeoylquinic acid on SH-SY5Y cells and senescence-accelerated-prone mice 8 through the up-regulation of phosphoglycerate kinase-1. Neuroscience. 2010;69(3):1039–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]