Abstract

Fibrosing diseases, such as pulmonary fibrosis, cardiac fibrosis, myelofibrosis, liver fibrosis, and renal fibrosis are chronic and debilitating conditions and are an increasing burden for the healthcare system. Fibrosis involves the accumulation and differentiation of many immune cells, including macrophages and fibroblast-like cells called fibrocytes. The plasma protein serum amyloid P component (SAP; also known as pentraxin-2, PTX2) inhibits fibrocyte differentiation in vitro, and injections of SAP inhibit fibrosis in vivo. SAP also promotes the formation of immuno-regulatory Mreg macrophages. To elucidate the endogenous function of SAP, we used bleomycin aspiration to induce pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis in mice lacking SAP. Compared to wildtype C57BL/6 mice, we find that in Apcs-/- “SAP knock-out” mice, bleomycin induces a more persistent inflammatory response and increased fibrosis. In both C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice, injections of exogenous SAP reduce the accumulation of inflammatory macrophages and prevent fibrosis. The types of inflammatory cells present in the lungs following bleomycin-aspiration appear similar between C57BL/6 and Apcs -/- mice, suggesting that the initial immune response is normal in the Apcs-/- mice, and that a key endogenous function of SAP is to promote the resolution of inflammation and fibrosis.

Introduction

Fibrosing diseases, such as pulmonary fibrosis, cardiac fibrosis associated with hypertensive heart disease, primary myelofibrosis of the bone marrow, liver fibrosis, and renal fibrosis are chronic and debilitating conditions and are an increasing burden for the healthcare system [1]. For instance, pulmonary fibrosis has a survival rate of only 30% five years after diagnosis and an incidence of 1 in 400 in the elderly [2]. There is currently no FDA-approved therapeutic for fibrosis in the US [3]. In fibrosing diseases, scar tissue-like fibrotic lesions cause tissue dysfunction [1], [4]. Fibrosis is mediated by infiltration of blood leukocytes into a tissue, activation and/or appearance of fibroblast-like cells, tissue remodeling, and deposition of extracellular matrix proteins such as collagen [1], [4].

Following their recruitment from the blood into a tissue, monocytes can differentiate into macrophages, dendritic cells, or fibrocytes [4], [5]. Macrophages can have inflammatory M1, pro-fibrotic M2a, or immune-regulatory M2reg characteristics [6], [7]. M1 macrophages produce IL-1β, IL-12, and TNF-α, and modulate host defense against intracellular pathogens, tumor cells, and tissue debris, but are also responsible for tissue damage associated with their release of reactive oxygen species [4], [6]. Pro-fibrotic M2a macrophages are induced by IL-4 or IL-13, are important in the clearance of parasitic infections, and promote tissue remodeling following inflammation, but also secrete a variety of factors that promote fibrosis [1], [8]. Regulatory M2reg macrophages are generally anti-inflammatory, secrete IL-10, and are important during the resolution phase of inflammation [1], [9]. Although these subsets can be viewed as separate, they may be more accurately thought of as a continuum, and may convert from one subset to another depending on the stimuli in an environment [7], [9].

There are multiple sources of fibroblast-like cells present in fibrotic lesions [4]. In addition to the proliferation of resident fibroblasts, proliferation and differentiation of pericytes, and the process of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), monocytes present within the blood are attracted to sites of injury where they differentiate into spindle-shaped fibroblast-like cells called fibrocytes, which, at least in part, mediate tissue repair and fibrosis [5], [10], [11]. Fibrocytes differentiate from CD14+ monocytes [5], [11]–[14]. Fibrocytes have been detected in human pathological conditions including asthma and pulmonary fibrosis [5], [15], , and in animal models of pulmonary fibrosis [5], [17]–[20].

We previously found that the plasma protein Serum Amyloid P component (SAP; PTX2) inhibits human and murine fibrocyte differentiation [12], [21]–[25]. In humans and most mammals, the level of SAP in the plasma is maintained at relatively constant levels, between 20–50 μg/ml [26]. In mice, SAP acts as an acute phase protein, with levels rising up to 20-fold following an inflammatory insult [27], [28]. SAP also inhibits fibrosis, not only by inhibiting fibrocyte differentiation, but also by regulating macrophage polarization [24], [25], [29]–[33]. SAP induces the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, inhibits the formation of pro-fibrotic M2a macrophages, and promotes the formation of immuno-regulatory Mreg macrophages [30], [32]–[35]. SAP is a member of the pentraxin family of proteins that includes C-reactive protein (CRP; PTX1) and pentraxin-3 (PTX3). Injections of human or murine SAP inhibit inflammation and fibrosis in animal models of pulmonary fibrosis [24], [30], [32], cardiac fibrosis [25], [29], dermal wound healing [23], radiation-induced oral mucositis [31], allergic airway disease [34], experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis [36], and kidney injury [33]. In a Phase 1B clinical trial, injections of recombinant human SAP appeared to improve lung function in pulmonary fibrosis patients [37].

Pentraxins including SAP bind to the receptors for the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G (FcγR) to initiate signaling cascades consistent with FcγR ligation, and SAP has been crystallized bound to FcγRIIa [29], [33], [38]–[42]. Human and murine monocytes express multiple FcγR receptors [43], [44]. In mice, the activating FcγRs are FcγRI, FcγRIII, and FcγRIV, and all three require FcRγ for signaling [43]. The inhibitory receptor is FcγRIIb [45]. SAP appears to act through FcγRI and FcRγ ligation to regulate the differentiation of monocytes into fibrocytes [21]. In addition, the ability of SAP to inhibit fibrosis in mouse models of pulmonary and kidney fibrosis is dependent on the FcRγ component of activating Fcγ receptors [29], [33]. Both human and murine SAP appear to bind to the same receptors [21].

In tissue culture, human and mouse monocytes spontaneously differentiate into fibrocytes when there is no SAP present [12]–[14], [46], [47]. If SAP is the only factor limiting fibrocyte differentiation and promoting immune-regulatory macrophages, this would suggest that mice lacking SAP would have an excess of M2a pro-fibrotic macrophages and fibrocytes, and spontaneously form fibrotic lesions, and thus mice lacking SAP would die quickly. However, Apcs-/- (Amyloid P component, serum) “SAP knockout mice” appear to be normal and have normal viability [48]–[50], although compared to C57BL/6 mice Apcs-/- mice are more susceptible to experimental bacterial lung infection [51]. This viability of mice lacking SAP thus suggests that in addition to SAP, other mechanisms inhibit fibrocyte differentiation and regulate fibrosis.

To elucidate the endogenous function of SAP, in this report we used bleomycin to induce inflammation and fibrosis in the lungs of Apcs-/- mice. We find that the induced lung inflammation and fibrosis in the Apcs-/- mice is persistent compared to C57BL/6 wild type mice. However, the inflammatory cells present in the lungs after bleomycin aspiration appear similar between C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice, suggesting that the initial response to the insult is independent of SAP, and that a key function of SAP is to promote the resolution of inflammation and fibrosis.

Methods

Bleomycin-induced lung inflammation

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Texas A&M University Animal Use and Care Committee (TAMU AUP #2009-0265 and #2013-0007). All procedures were performed under anesthesia, and all efforts were made to minimize suffering. 4-6 week old C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and Apcs-/- “SAP-knock-out” mice [48] were treated with an oropharyngeal aspiration of 50 μl of 3 U/kg bleomycin (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) solution in 0.9% saline or saline alone, as described previously [52]–[54]. 24 hours after bleomycin aspiration, mice were given daily intraperitoneal injections of 50 μg human SAP in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer or an equal volume of buffer, as described previously [23]–[25], [29], [53]. Arterial oxygen saturation, heart rate, and pulse distention (which measures the local blood flow at the sensor location, and is an indirect indicator of blood flow and blood pressure), were measured using the Mouse Ox vital signs monitor (STARR Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA), as described previously [24], [55]. Mice were sedated for 60 seconds with 4% isoflurane in oxygen, removed to room air, and then parameters monitored until the mice were active. To measure organ weights, following euthanasia mice were weighed, blood was collected from the abdominal aorta to isolate serum, and the heart, spleen, kidneys, lungs, and liver were removed and weighed. Mice were euthanized at 7 or 21 days after bleomycin aspiration, weighed, blood was collected from the abdominal aorta to isolate serum, and the lungs were then perfused through the trachea with 300 μl of PBS three times to collect cells by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) as described previously [53], [54], [56]. The BAL cells were collected by centrifugation at 300×g for 5 minutes, and the supernatants were transferred to eppendorf tubes, flash frozen with liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. The cells collected from BAL were resuspended in 4% BSA-PBS, counted with a hemocytometer, and cytopsins prepared as described previously [53], [54], [57]. After BAL, lungs were inflated with pre-warmed optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (VWR, Radnor, PA), embedded in OCT, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C as described previously [24], [53], [54].

Fibrocyte differentiation assay

Mouse spleen cells were isolated as described previously, except that the spleens were digested with Accutase (Global Cell Solutions, Charlottesville, VA) for 30 minutes at room temperature according to the manufacturers' instructions [21], [22]. Spleen cells were cultured in FibroLife (Lifeline Cell Technology, Frederick, MD) serum-free medium (SFM) including 50 ng/ml murine IL-13 and 25 ng/ml murine M-CSF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), as described previously [21], [22], [46]. Spleen cells were cultured in flat-bottomed, 96-well, tissue-culture plates at 3.5×105 cells/well in 200 μl with human SAP at the indicated concentrations. On day 3 of the incubation, wells were supplemented with IL-13 and M-CSF, as described previously [21], [22]. After 5 days, plates were air-dried, fixed with methanol, and stained with eosin and methylene blue, as described previously [12]–[14], [21], [22], [46]. Fibrocytes were counted using the following criteria: an adherent cell with elongated spindle-shaped morphology and an oval nucleus, as described previously [12]–[14], [21], [22], [46]. IC50 values were obtained by fitting a sigmoidal dose response curve to the data.

Flow Cytometry

Spleen cells were analyzed by flow cytometry, as described previously [21], [22], [46]. Cells were stained using 5 μg/ml of antibodies against CD3 (clone 17A2, rat IgG2b, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) to detect T cells; CD11b (clone M1/70, rat IgG2b, BioLegend, San Diego, CA) to detect neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages; CD11c (clone 223H7, rat IgG2a, MBL International, Woburn, MA) to detect dendritic cells and macrophages; CD16/32 to detect the epitope common to FcγRII and FcγRIII (clone 93, rat IgG2a, BioLegend), CD45R/B220 (clone RA3-6B2, rat IgG2a, BD Biosciences) to detect B cells; Ly6G (clone 1A8, rat IgG2a, BD Biosciences) to detect neutrophils; GR-1 (clone RB6-8C5, rat IgG2b, BD Biosciences) to detect Ly-6C and Ly-6G macrophage subsets and neutrophils; and isotype-matched irrelevant rat monoclonal antibodies (BioLegend). The secondary antibody was a FITC-conjugated mouse F(ab')2 anti-rat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) used at 2.5 μg/ml. After blocking with PBS/20% rat serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 30 minutes at 4°C, cells were incubated with 2.5 μg/ml biotinylated anti-CD45 (clone 30-F11, rat IgG2b, BioLegend). After a 30 minute incubation on ice, cells were washed and then incubated with streptavidin-APC (BioLegend). After a 30-minute incubation on ice, cells were washed twice, resuspended in 100 μl ice-cold PBS/2% BSA, and analyzed using a C6 flow cytometer (Accuri, Ann Arbor, MI).

Immunochemistry

BAL cytospins and frozen lung tissue sections (5 μm) were prepared and immunochemistry performed as described previously [24], [35], [53], [54]. Antibodies to Ly6G (BioLegend) were used to detect neutrophils, CD11b (BioLegend) to detect blood and inflammatory macrophages, CD11c (MBL International) to detect resident lung macrophages and dendritic cells, Gr-1 (BioLegend) to detect infiltrating macrophages and neutrophils, CD206 (BioLegend) to detect the mannose receptor on macrophages and dendritic cells, and CD45 (BioLegend) to detect all leukocytes. Isotype-matched mouse irrelevant antibodies were used as controls. Lung sections were also stained with H&E or sirius red to detect inflammation, fibrosis, and collagen, as described previously [24], [35], [53], [54]. Several studies have shown that histological analysis of fibrosis and collagen content by techniques such as sirius red staining, correlates well with total collagen content as measured by hyproxyproline or sirius red (Sircol) assays [58]–[62].

Lung collagen content assays and BAL cytokine measurements

Lungs of naïve mice were purged of blood, excised, weighed, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C, as described previously [24]. Lungs were digested with 0.1 mg/ml pepsin in 0.5 M acetic acid overnight at 4°C. Tissue debris was removed by centrifugation, and collagen determined using the sirius red dye assay, as described previously [24], [52], [63]. Primary BAL fluids were assessed for IL-13 by ELISA (Peprotech), following the manufacturer's instructions. Total protein in the primary BAL was assessed by absorbance at 260 nm, 280 nm and 320 nm, using a Synergy MX spectrophotometer (BioTek, Winooski, VT). In addition, BAL fluids were analyzed by PAGE, and gels stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, as described previously [12], [24].

Measurement of endogenous murine SAP and exogenous human SAP

Blood from untreated mice, and mice euthanized at day 7 and 21 after bleomycin aspiration was collected and serum stored at −20°C. Exogenous human SAP was measured by ELISA, as described previously [12], [64]. This ELISA does not cross-react with murine SAP or other murine serum proteins (data not shown). To detect endogenous murine SAP, serum was analyzed by western blotting using sheep anti-mouse SAP antibodies (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), as described previously [12], [21], [24], [64].

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance between two groups was determined by t test, or between multiple groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

Naïve Apcs-/- mice have altered lung function

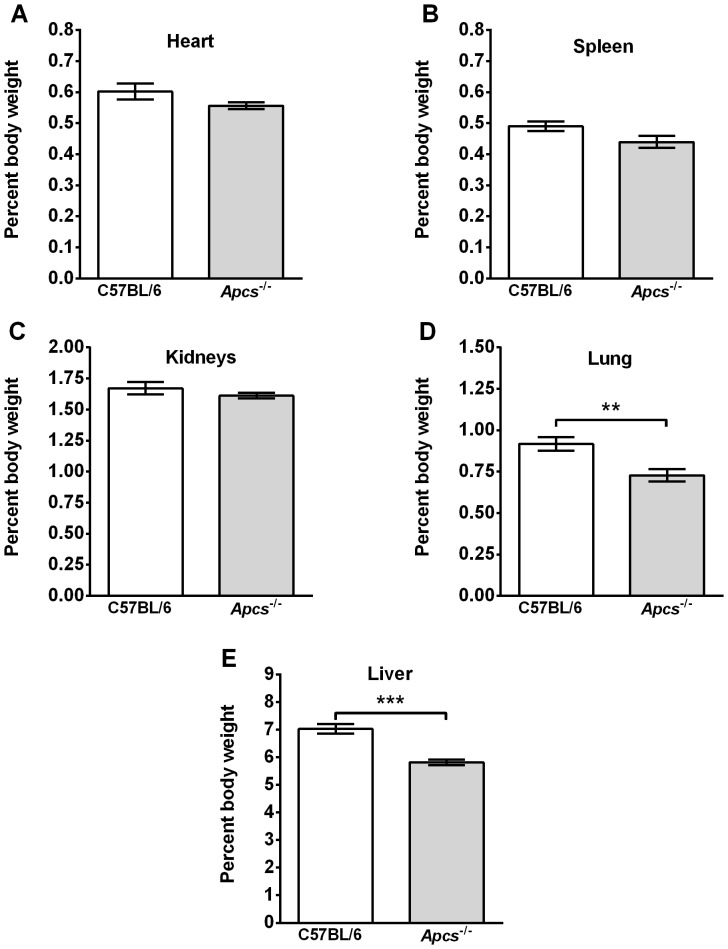

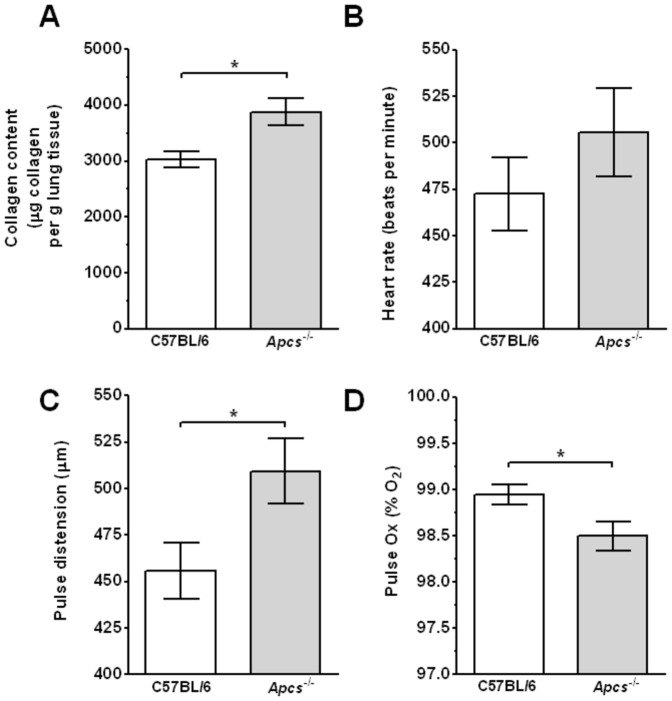

Apcs-/- mice were originally generated on a 129 background and then backcrossed to C57BL/6 mice [48], [65]. The back-crossed F2 Apcs-/- mice develop glomerulonephritis in adults >6 months old. This hybrid genetic background (129×C57BL/6) has since been shown to generate autoantibodies and glomerulonephritis independent of the Apcs-/- locus [66]–[68]. However, the mice used in the experiments described below were backcrossed for 10 generations to C57BL/6 mice as described previously [66], [67], [69]. In addition, after transfer from the Botto lab, the Apcs-/- mice were re-derived and then backcrossed for an additional two generations to C57BL/6 mice. Mice were checked for Apcs-/- gene deletion by PCR, and the sera were screened for absence of SAP protein by ELISA and/or western blotting (data not shown). To further reduce the possible effects of autoimmunity found in >6 months old mice, all experiments were performed on 4–6 week old mice. However, as young Apcs-/- mice may have altered lung and kidney characteristics due to the presence of autoantibodies, low grade fibrosis, and/or underlying infections, we compared the organ weights of 4–6 week old naïve C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice, using organ weight increase as an indicator of edema associated with inflammation [70]. The heart, spleen, and kidney weights (as a percent of body weight) were similar between Apcs-/- and C57BL/6 mice, but the liver and lung weights were lower in Apcs-/- mice (Figure 1). Compared to C57BL/6 mice, the lungs of Apcs-/- mice had increased collagen content (Figure 2A), although the lungs appeared histologically normal (data not shown). However, we could not detect the presence of the pro-fibrotic cytokine IL-13 (detection limit 7.8 pg/ml) in BAL samples (data not shown). There was a significant difference in the pulse oximetry and pulse distention (which measures the local blood flow at the sensor location and is an indirect indicator of blood flow and blood pressure), but not heart rate, between naïve C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice (Figure 2B–D). Together, these observations suggest that in mice, SAP slightly increases lung and liver mass, decreases lung collagen content, and potentiates lung function.

Figure 1. Organ weights in Apcs-/- mice.

Body and organ weights from animals not exposed to bleomycin or exogenous SAP were measured. Organ weights are expressed as a percent of body weight. A) heart, B) spleen, C) kidneys, D) lungs, and E) liver. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 12 for C57BL/6; n = 24 for Apcs-/-). **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 (t-test).

Figure 2. Apcs-/- mice have increased lung collagen and reduced lung function.

A) Lungs were assessed for collagen content. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 8 per group). Mice were assessed for B) heart rate, C) pulse distension, and D) peripheral blood oxygen content (pulse Ox). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 21 for C57BL/6; n = 14 for Apcs-/-). *p<0.05 (t-test).

Apcs-/- mice have a reduced number of spleen monocytes and increased inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by SAP

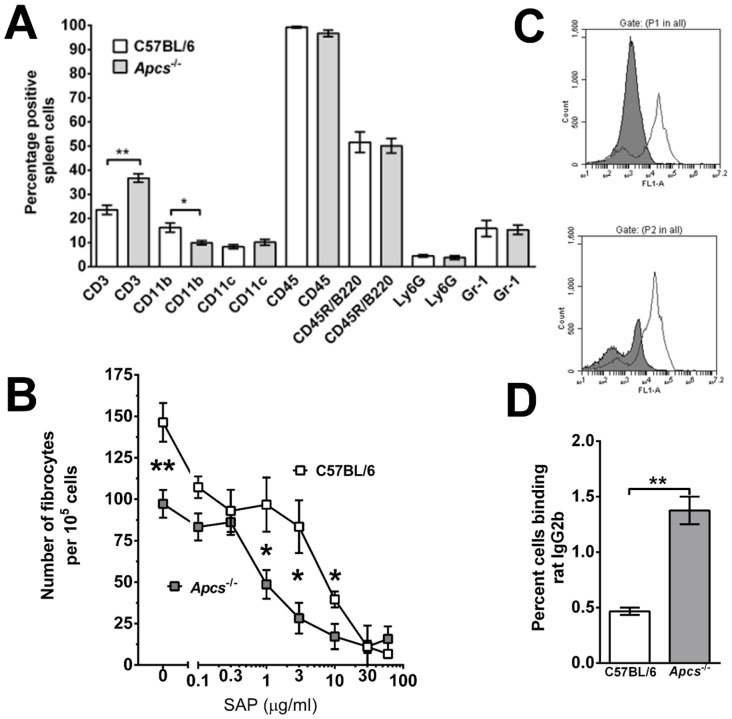

As the subsequent experiments aim to investigate the role of SAP in bleomycin-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis, we tested if Apcs-/- mice had altered immune cell numbers or an altered response to SAP. We found no significant difference in the number of cells recovered from the spleens of C57BL/6 (90±5×106; mean ± SEM; n = 3) and Apcs-/- mice (100±6×106; n = 4). Compared to C57BL/6 mice, Apcs-/- mice have increased numbers of CD3+ T cells and reduced numbers of CD11b+ monocytes and macrophages in the spleen (Figure 3A). We found no significant difference in the percentage of CD11c+ macrophages and dendritic cells, CD45+ leukocytes, CD45R/B220+ B cells, Ly6G+ neutrophils, or Gr-1+ inflammatory macrophages (Figure 3A). Spleen monocytes are CD11b+, CD11c−, Gr-1-, whereas spleen macrophages are CD11b+, CD11c+, and can be either Gr-1 positive or negative [71]–[73]. As the percentage of CD11c, Ly6G, and Gr-1 positive spleen cells was not different between C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice, these data suggest that the lower numbers of CD11b+ cells may reflect a lower number of spleen monocytes.

Figure 3. Spleen leukocyte populations and fibrocyte differentiation in Apcs-/- mice.

A) Spleen cells were analyzed for leukocyte cell populations using antibodies and flow cytometry. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3 for C57BL/6; n = 4 for Apcs-/- mice). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (t-test). B) Spleen cells were cultured for 5 days in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of SAP. After 5 days, cells were air-dried, fixed, and stained, and the number of fibrocytes was counted. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3 for C57BL/6; n = 4 for Apcs-/- mice). *p<0.05 (t-test). C) Spleen cells from C57BL/6 (top panel) and Apcs-/- (bottom panel) mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD45R/B220 (white histogram) and CD16/32 (grey histogram) using a mAb (clone 93) to a common epitope of FcγRII and FcγRIII. Flow cytometry data is a representative of four independent experiments. D) Spleen cells were incubated with rat IgG2b antibodies and IgG2b binding was analyzed by flow cytometry. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3 for C57BL/6; n = 4 for Apcs-/- mice). **p<0.01 (t-test).

Spleen cells from C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice were cultured in SFM for 5 days in the presence or absence of human SAP. Compared to the C57BL/6 spleen cells, in the absence of exogenous SAP, there were fewer fibrocytes in cultures of Apcs-/- spleen cells (Figure 3B). The decreased percentage of CD11b+spleen cells in the Apcs-/- mice (Figure 3A), and the decreased number of fibrocytes that differentiate from a given number of Apcs-/- spleen cells (Figure 3B), suggests that there is a decreased number of spleen monocytes that are capable of differentiating into fibrocytes in Apcs-/- mice.

We also tested if Apcs-/- mice had an altered fibrocyte response to SAP. As previously observed [21], [22], SAP inhibited the differentiation of fibrocytes from C57BL/6 spleen cells with an IC50 of 4.7±2.7 μg/ml (mean ± SEM) (Figure 3B), whereas Apcs-/- spleen cells had an IC50 of 0.9±0.1 μg/ml. These data suggest that the presence of endogenous SAP desensitizes monocytes to exogenous SAP, possibly by downregulating SAP receptor expression and/or signal transduction pathways. To determine if the absence of endogenous SAP alters FcγR expression, we stained spleen cells for FcγRs. We found no significant difference in the number of FcγRI positive cells, or their staining intensity (data not shown). However, Apcs-/- spleen cells had two discrete populations of spleen cells staining for a common epitope of FcγRII and FcγRIII, whereas spleen cells from C57BL/6 contain a single population (Figure 3C). Rat IgG2b binds to FcγR with high affinity [74], [75]. Compared to C57BL/6 spleen cells, Apcs-/- mice had increased numbers of rat IgG2b-binding spleen cells (Figure 3D). These data suggest that endogenous SAP either alters the expression of FcγR, or binds to the FcγR to prevent antibody binding.

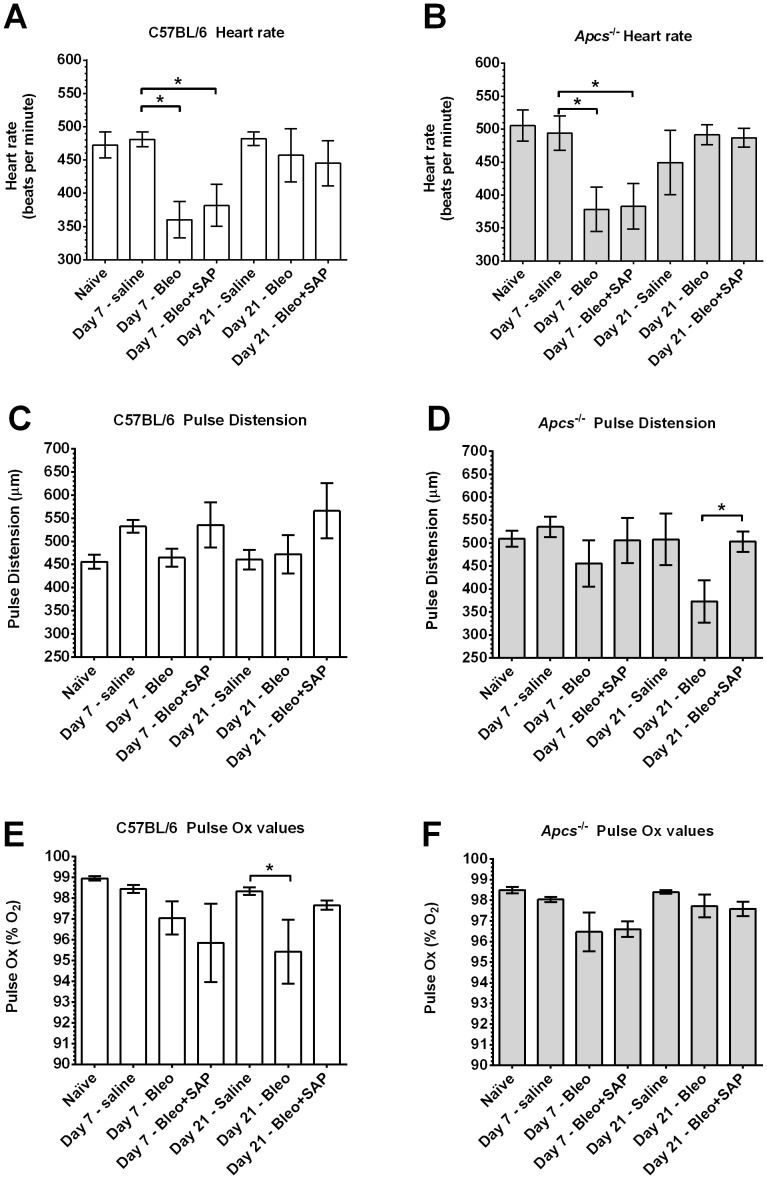

SAP is required to maintain pulse distension at 21 days after bleomycin treatment

Bleomycin aspiration leads to epithelial cell damage, inflammation, collagen deposition, and fibrosis [76], [77]. These changes also reduce lung function and peripheral blood oxygen content [24], [78]. To determine if Apcs-/- mice had an altered response to bleomycin aspiration, we measured heart rate, pulse distension, and arterial oxygen saturation (pulse Ox) at 7 days after aspiration, when there is acute inflammation and alveolar cell death, and at 21 days when there is peak fibrosis and the acute toxic effects of bleomycin have receded [76]. We observed that at day 7 in both C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice, bleomycin caused a significant reduction in heart rate compared to mice receiving saline (Figures 4A and 4B). This effect was present in mice treated with either SAP injections or buffer. At 21 days after bleomycin aspiration, the heart rate appeared normal in C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice irrespective of SAP treatment (Figures 4A and 4B). There appeared to be no significant changes in pulse distension in C57BL/6 mice (Figure 4C). At 21 days after bleomycin aspiration, Apcs-/- mice had a significant reduction in pulse distension compared to Apcs-/- mice treated with SAP (Figure 4D). At 21 days after bleomycin aspiration, there appeared to be a reduction in arterial blood oxygen saturation in C57BL/6 mice (Figure 4E). However, in mice treated with SAP, there was no significant change in arterial blood oxygen saturation (Figure 4E). Together, these results indicate that 21 days after bleomycin treatment, Apcs-/- mice show an abnormally low pulse distension, and that this phenotype can be rescued by SAP injections.

Figure 4. Heart rate, pulse distension, and pulse Ox after bleomycin aspiration.

At day 7 and 21 after bleomycin aspiration, C57BL/6 (A, C, E) and Apcs-/- (B, D, and F) mice were assessed for A) and B) heart rate, C) and D) pulse distension and E) and F) pulse Ox. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4–9 mice per time point). *p<0.05 (1-way ANOVA, Tukey's test).

Apcs-/- mice have increased numbers of inflammatory macrophages following aspiration of bleomycin

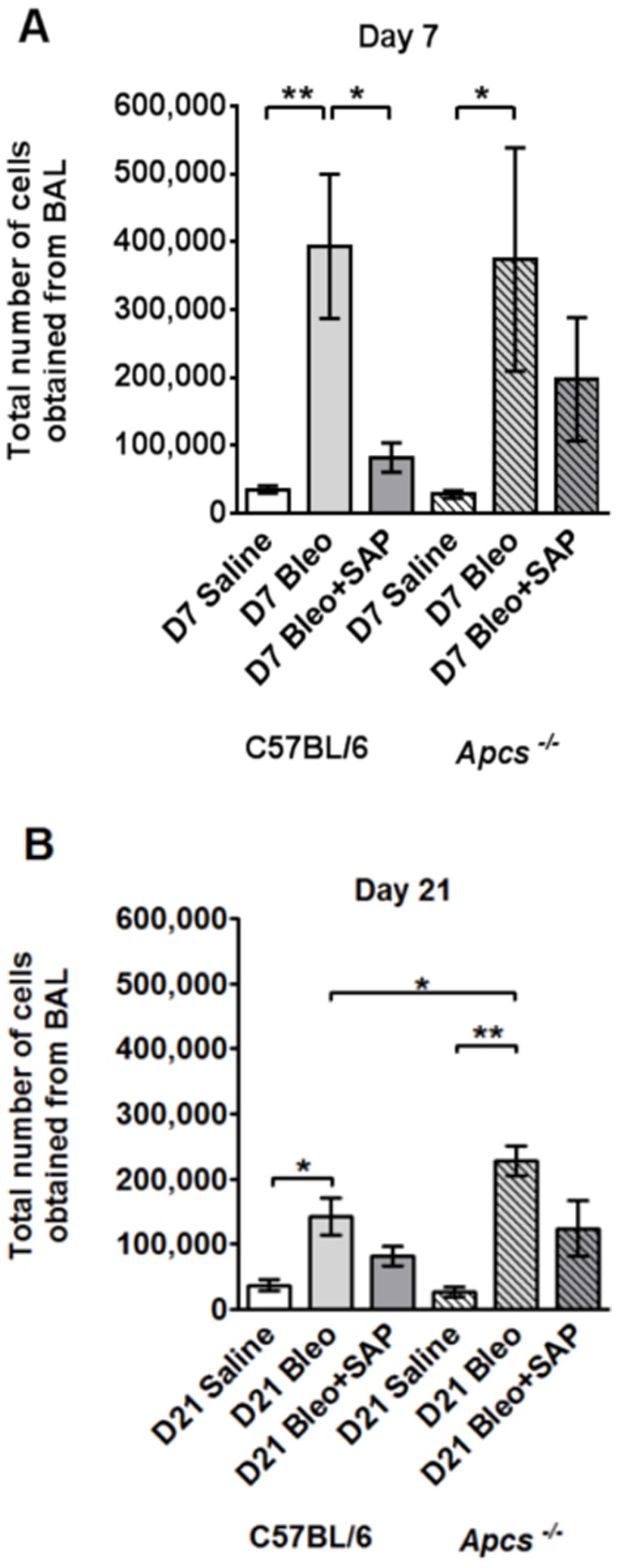

SAP injections inhibit neutrophil, macrophage, and fibrocyte accumulation in the lungs of bleomycin-treated C57BL/6 mice [24], [30], [53]. We thus tested the hypothesis that bleomycin aspiration would cause increased numbers of cells in the lungs, and/or a more persistent inflammatory and fibrotic response, in Apcs-/- mice. Following bleomycin aspiration, C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice were treated with daily intraperitoneal injections of SAP or buffer, and then euthanized at 7 days (to measure the inflammatory response) and 21 days (to measure the fibrotic response) [76], [79]. The weakly adhered cells from the airways were collected by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), counted, and cell morphology was used to determine the total number of neutrophils, macrophages, and lymphocytes in the BAL. At day 7, the BAL from mice receiving bleomycin alone contained significantly more cells than the saline control for both genotypes, and the mice given bleomycin and then treated with SAP tended to have less cells than the mice given bleomycin (Figure 5A). These data suggest that the early response to bleomycin-induced inflammation is similar in C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice.

Figure 5. Changes in BAL cell number following bleomycin aspiration.

The total number of cells collected from the BAL is shown in A) for day 7 and B) for day 21. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4–6 mice per group). *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (by ANOVA between groups, and t-test when comparing C57BL/6 and Apcs-/-).

At day 21, the BAL from C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice given bleomycin aspiration without SAP treatment contained significantly more cells than the saline control (Figure 5B). However, bleomycin caused significantly more cells to appear in the BAL of Apcs-/- mice compared to C57BL/6 mice (Figure 5B). There was no significant difference in the number of cells in the BAL of C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice given saline alone, or given bleomycin and then treated with SAP (Figure 5B). These data suggest that a phenotype of Apcs-/- mice is that they have a more persistent inflammatory response compared to C57BL/6 mice, and that this effect can be decreased by SAP injections.

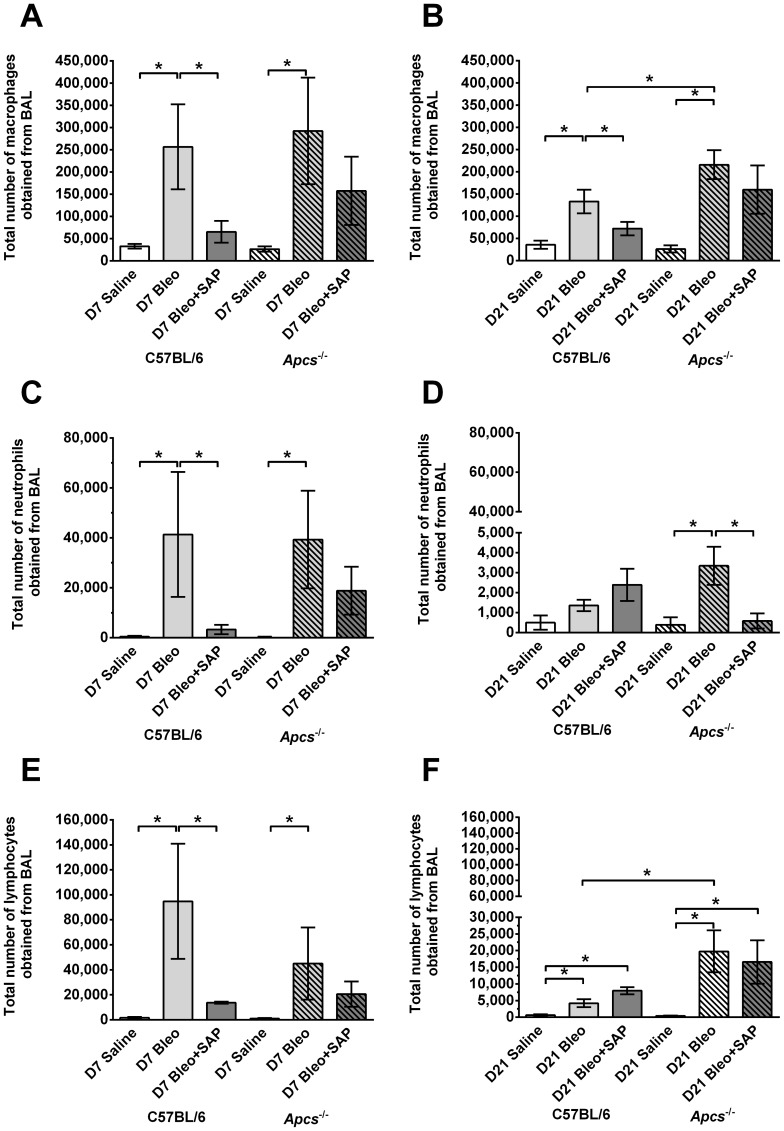

Cell morphology was used to determine the total number of macrophages, lymphocytes, and neutrophils in the BAL. At day 7, compared to saline aspiration, there were elevated numbers of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes in the BAL of both C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice given bleomycin, and these numbers were reduced by SAP treatment (Figure 6A, B, and C). At day 21, compared to C57BL/6 mice, there were significantly more macrophages and lymphocytes in the BAL of Apcs-/- mice following bleomycin aspiration, and these numbers were reduced somewhat by SAP treatment (Figure 6B and F).

Figure 6. Changes in BAL leukocyte populations following bleomycin aspiration.

Graphs show the total number of A) and B) macrophages, C) and D) neutrophils, and E) and F) lymphocytes obtained in the BAL at day 7 (A, C, and E) and day 21 (B, D, and F). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4–6 mice per group). *p<0.05 (by ANOVA between groups, and t-test when comparing C57BL/6 and Apcs-/-).

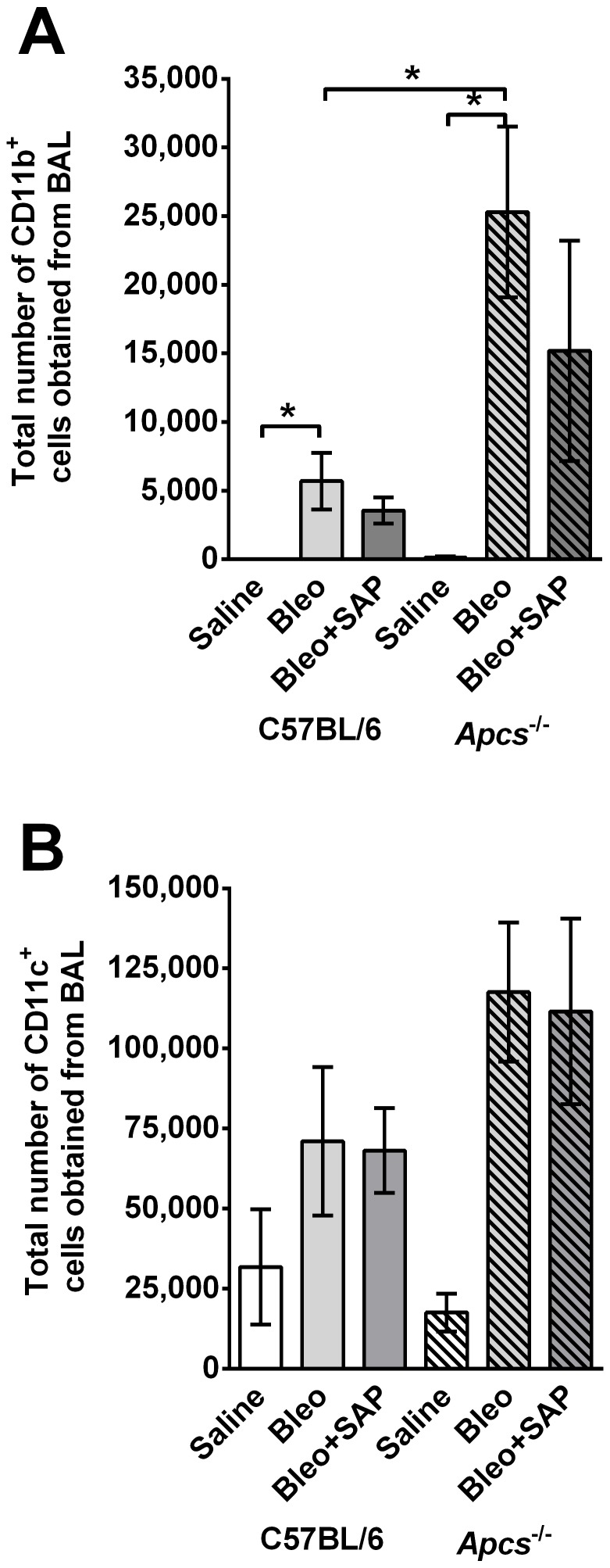

BAL cells were also labeled with antibodies to identify resident alveolar macrophages (CD11b- CD11c+) or newly recruited inflammatory macrophages (CD11b+ CD11c+) [80]–[83]. At 21 days post-bleomycin aspiration, compared to C57BL/6 mice, there were significantly more CD11b+ cells in the BAL of Apcs-/- (Figure 7A). SAP treatment slightly reduced these numbers in both C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice. There was no significant difference in the number of resident alveolar CD11c+ cells between C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice that aspirated bleomycin (Figure 7B). These data indicate that SAP limits CD11b+ inflammatory macrophage accumulation in mouse lungs at 21 days after bleomycin aspiration.

Figure 7. Changes in BAL CD11b+ inflammatory cells and CD11c+ resident lung cells in C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice.

Graphs show the total number of A) CD11b positive and B) CD11c positive cells collected from the BAL at day 21. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3–6 per group). *p<0.05, (t-test).

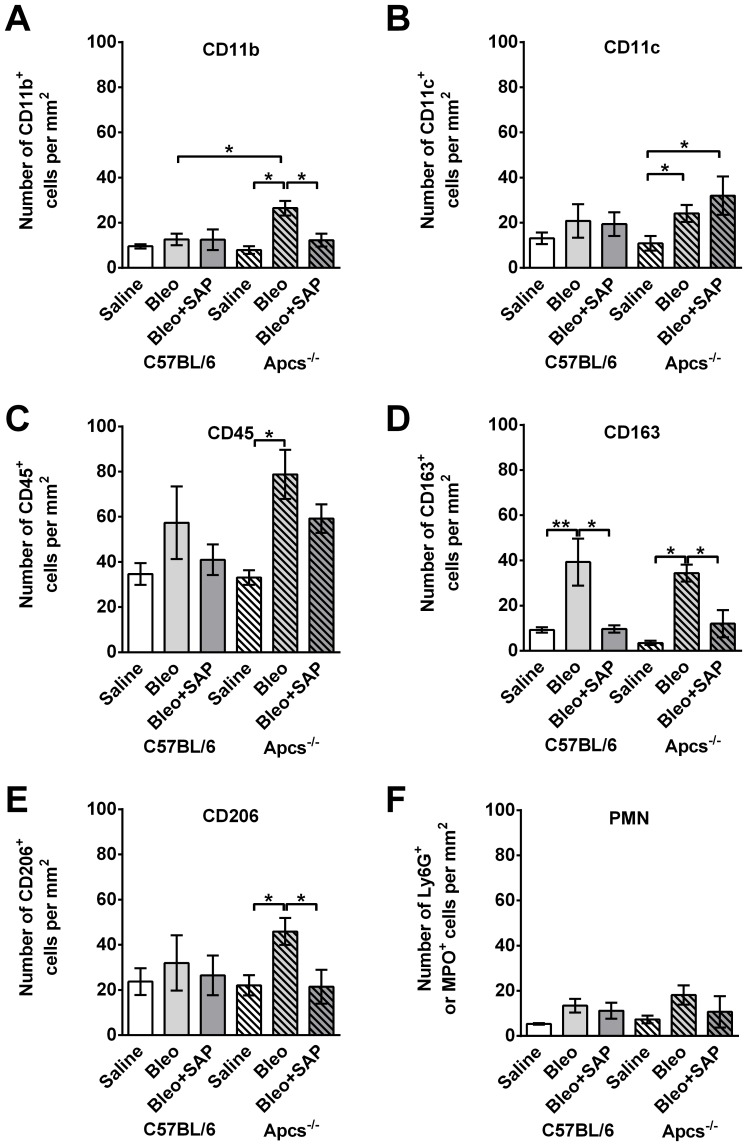

Following BAL, lungs were sectioned and stained with antibodies to detect cells that were not removed by BAL. At 21 days after bleomycin aspiration, compared to C57BL/6 mice, there were significantly more CD11b+ cells in the lungs of Apcs-/- mice (Figure 8A). In addition, SAP treatment significantly reduced the number of CD11b+ cells in the lungs of Apcs-/- mice (Figure 8A). At day 21, bleomycin also cause an increase in CD11c+, CD45+, CD163+, and CD206+ cells in Apcs-/- lungs, and SAP injections reduced the number of CD163+ and CD206+ cells (Figure 8B, C, D, and E). In C57BL/6 mice, following bleomycin aspiration, the only significant difference compared to the saline control was an increase in CD163+ cells, which was also reduced with SAP injections (Figure 8D). There was no difference in the numbers of CD11b, CD11c, CD45, or CD206 positive cells in the lungs of C57BL/6 mice treated with bleomycin compared with those treated with bleomycin and then receiving SAP injections (Figure 8). There were no significant changes in the numbers of neutrophils in either C57BL/6 or Apcs-/- mice (Figure 8F). These results suggest that a phenotype of Apcs-/- mice is an abnormally high number of CD11b inflammatory macrophages present in the lungs after BAL at 21 days after bleomycin treatment, and that this phenotype is rescued by SAP injections.

Figure 8. Changes in tissue leukocyte population in C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice following bleomycin instillation.

Cryosections of mouse lungs were labeled with antibodies against A) CD11b (neutrophils and inflammatory macrophages), B) CD11c (resident macrophages and dendritic cells), C) CD45 (total leukocytes), D) CD163 (macrophages), E) CD206 (macrophages), and F) Ly6G (neutrophils). Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4–6 mice per group). Significance was determined by ANOVA within treatment groups and t-test when comparing C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice.

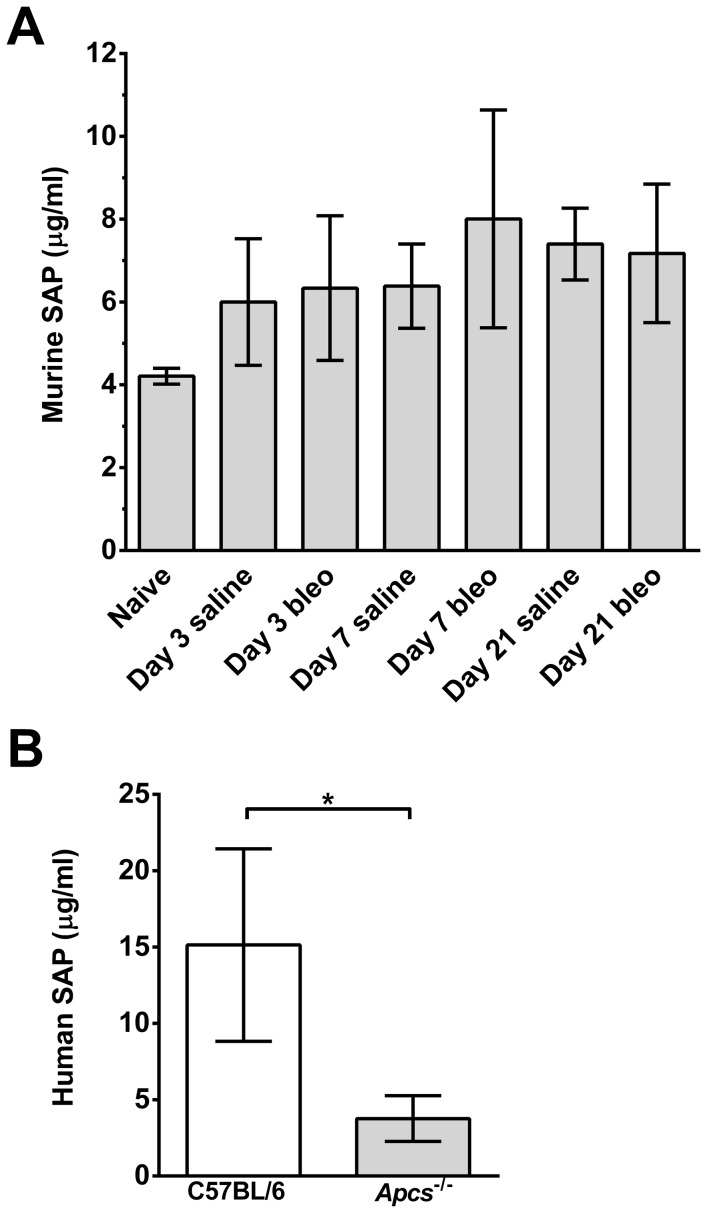

Bleomycin aspiration does not increase endogenous SAP levels

Exogenous SAP injections reduce inflammation and fibrosis in many organ systems [3], [84]. However, as SAP is an acute phase response protein in mice [85], [86], the stimuli that induce inflammation and fibrosis may elevate endogenous SAP. Therefore, we tested if bleomycin aspiration increased endogenous SAP levels in the serum of C57BL/6 mice. We did not observe a significant increase in murine serum SAP at 3, 7, or 21 days after bleomycin aspiration (Figure 9A). These data indicate that bleomycin aspiration does not appear to promote a persistent systemic increase in SAP levels. As the lack of endogenous SAP in the Apcs-/- mice may alter the pharmacokinetics for exogenous SAP, we collected serum from C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice injected daily for 6 days with 50 μg SAP following bleomycin aspiration. We observed that exogenous human SAP was detectable at day 7 in the sera of both C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice (Figure 9B), although the levels were lower in Apcs-/- mice (Figure 9B). In addition, we did not detect any compensatory changes in the levels of serum CRP between C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice either at baseline or at 7 or 21 days after bleomycin challenge (data not shown).

Figure 9. Endogenous and exogenous SAP levels in C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice.

A) Serum was collected at day 0, 3, 7, and 21 from C57BL/6 mice that had received saline or bleomycin. Serum was assayed for the presence of endogenous murine SAP by western blotting. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3–7 mice per group). B) C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice were injected with human SAP for 6 days following bleomycin aspiration. Serum was collected at day 7 and human SAP levels determined by ELISA. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4–6 mice per group).

Endogenous or exogenous SAP has no effect on bleomycin-induced lung damage

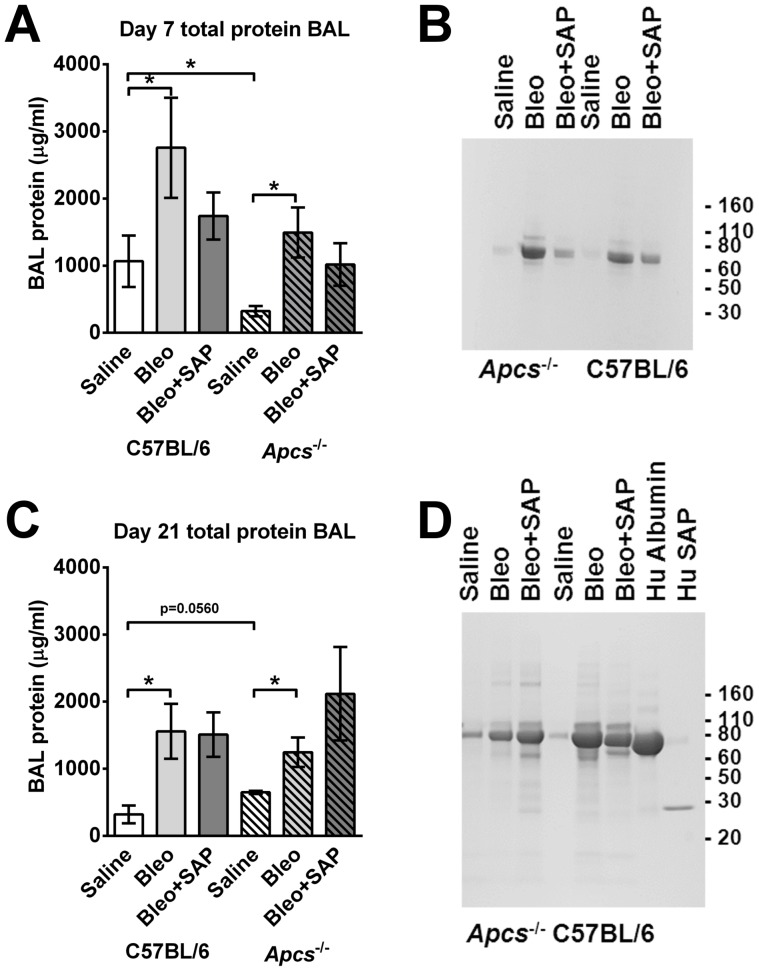

To determine if exogenous or endogenous SAP levels could also regulate bleomycin-induced lung damage, we measured total lung BAL protein levels, as a measure of lung tissue damage following bleomycin aspiration [87], [88]. We found that at day 7, bleomycin caused an increase in BAL protein levels, and that Apcs-/- mice had lower protein levels compared to C57BL/6 mice (Figure 10A). The bleomycin-induced BAL protein appeared to be mainly albumin, as determined by PAGE (Figure 9B and 9D). SAP injections did not significantly affect the protein levels present in the BAL. At day 21, following bleomycin aspiration BAL protein levels were also increased in the C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice (Figure 10C and 10D). SAP injections had no significant effect on BAL protein levels. These data suggest that SAP does not regulate edema or epithelial barrier destruction following bleomycin instillation.

Figure 10. SAP has no effect on bleomycin-induced lung damage.

BAL was collected at day 7 (A and B) and day 21 (C and D) following saline or bleomycin instillation, and SAP injections. A and C) Total protein was assessed by spectrophotometry. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3 for C57BL/6; n = 5 for Apcs-/-). * indicates p<0.05 (t test). B and D) BAL were analyzed by PAGE on a 4–15% reducing gel, and stained with Coomassie. In D, BAL samples were analyzed alongside human albumin and human SAP. The gel is representative of three independent experiments.

Apcs-/- mice have increased fibrotic response following aspiration of bleomycin

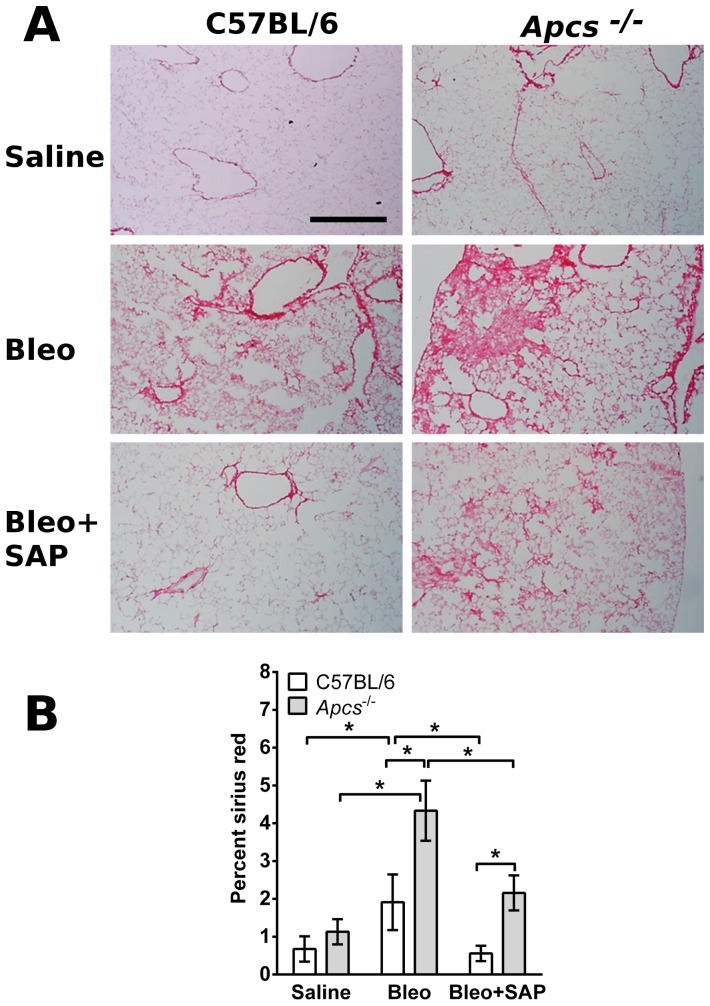

The data above suggest that Apcs-/- mice have a more severe inflammatory response and impaired lung function following bleomycin aspiration. To determine if Apcs-/- mice also have a more severe fibrotic response, lung sections were stained with picrosirius red to detect collagen. Compared to C57BL/6 mice, at 21 days after bleomycin treatment, Apcs-/- mice had increased numbers and size of fibrotic lesions and more extensive deposition of collagen (Figure 11). In addition, in both C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice, SAP injections significantly reduced picrosirius red staining (Figure 11A and B). These data suggest that a phenotype of Apcs-/- mice is an increased fibrotic response to bleomycin, that this phenotype can be rescued by SAP injections, and that treatment with exogenous SAP can reduce fibrosis.

Figure 11. Changes in collagen content in C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice following bleomycin aspiration.

A) Day 21 lungs were stained with picrosirius red to show collagen deposition. Bar is 500 μm. B) The percentage area stained with picrosirius red was quantified as a percentage of the total area of the lung. Significance was determined by ANOVA within treatment groups and t-test when comparing C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice. *p<0.05. (n = 4-6 mice per group).

Discussion

We found that compared to C57BL/6 mice, Apcs-/- mice had a persistent inflammatory response and increased fibrosis in the lungs after bleomycin aspiration. However, the inflammatory cells present during the initial phases of inflammation were similar between C57BL/6 and Apcs -/- mice, suggesting that the initial response to the insult is independent of SAP. These data suggest that a key function of SAP is to promote the resolution of inflammation and fibrosis.

Many groups have shown that SAP injections can reduce inflammation and fibrosis induced by multiple different stimuli [3], [84]. However, in all these experimental systems, endogenous SAP would be present and the stimuli used to induce inflammation and fibrosis may have also elevated endogenous SAP levels. However, the single bleomycin aspiration dose we used did not significantly increase plasma SAP levels. At day 7 following bleomycin aspiration, there was no difference in the number of cells recovered from the BAL of C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice, although we did observe that SAP injections reduced the BAL cell numbers in both strains of mice. These data suggest that the initial inflammatory response to bleomycin is similar in C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice, and that the levels of endogenous SAP are incapable of moderating the inflammatory response. These data may also help explain the strain variation in response to bleomycin. C57BL/6 mice are sensitive to bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, but Balb/c and DBA/2 strains are resistant [89], [90]. The different strain sensitivities to bleomycin have been associated to a variety of genes including bleomycin hydrolase [58], [91]. However, SAP may also play a crucial role as C57BL/6 mice have low levels of SAP (5–10 μg/ml) whereas the serum concentration of SAP in Balb/c and DBA/2 mice is 50–100 μg/ml [27], [86].

At day 21 following bleomycin aspiration, compared to C57BL/6 mice, Apcs-/- mice had significantly more cells in the BAL, and these cells contained a significant number of inflammatory CD11b+ macrophages. The cells present in the lung tissue of Apcs-/- mice also contained increased numbers of CD11b+ inflammatory macrophages, and CD206+ M2a pro-fibrotic macrophages. Compared to the C57BL/6 mice, the overall inflammatory and fibrotic response was elevated and persistent in the Apcs-/- mice, although the composition of the cells found was not significantly different. These data suggest that the inflammatory response is not aberrant in Apcs-/- mice, but that the absence of endogenous SAP leads to the persistence of signals that drive inflammation. As SAP binds to apoptotic cells and other debris formed during inflammation, and promotes phagocytosis of this material, the absence of SAP in Apcs-/- mice, or reduced levels of SAP in susceptible individuals, may be an additional contributing factor to persistent inflammation and fibrosis following inflammation [32], [92].

The observation that there was no significant difference in the BAL protein composition of C57BL/6 and Apcs-/- mice following bleomycin aspiration suggests that SAP has no protective effect on lung epithelial cells. However, following bleomycin exposure the apoptotic lung epithelial cells, when coated with SAP, are likely to be removed by phagocytosis without generating a pro-inflammatory response [30], [33], [93]–[95]. This agrees with previous data indicating that following TGFβ-induced lung fibrosis, exogenous SAP has no effect on the apoptosis of lung cells during the first week [32]. In addition, we have shown that SAP injections can be delayed for 7–10 days after an inflammatory insult, and yet still reduce inflammation and fibrosis [24], [32].

Compared to C57BL/6 mice, Apcs-/- spleen cells had an increased numbers of IgG binding cells, altered FcγR expression, and increased inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by SAP, indicating that endogenous SAP alters the expression of FcγR, and/or binding of SAP to the FcγR. These data also indicate that an additional function of endogenous SAP is to modulate FcγR expression and/or IgG binding, possibly to modulate the inflammatory response.

Compared to C57BL/6 mice, naïve Apcs-/- mice have significantly smaller lungs, with increased collagen content. This correlates with reduced pulse Ox and increased pulse distension in the Apcs-/- mice. These data suggest that the lungs of Apcs-/- mice are less efficient at oxygenating the blood, and that the heart is compensating to overcome this problem. These findings may be related to the reduced number and/or altered functionality of fibrocytes detected in the spleens of Apcs-/- mice. Together, our results suggest that endogenous and exogenous SAP levels are important in the regulation of bleomycin-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis, and that SAP promotes the resolution of inflammation and reduces fibrosis by multiple mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marina Botto (Imperial College, London) for providing the Apcs-/- mice. We thank the staff of the Comparative Medicine Program at Texas A&M University for assistance with the animal husbandry. We also thank Nehemiah Cox, Sarah Herlihy, Michael White, and Ivy Zheng for assistance with the oropharyngeal aspiration and bronchoalveolar lavage work, and Jonathan Phillips for critical reading of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Texas A&M University and National Institutes of Health grant HL083029. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Wynn TA, Ramalingam TR (2012) Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nature Medicine 18: 1028–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, et al. (2011) An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Statement: Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Evidence-based Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 183: 788–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomer RH (2013) New Approaches to Modulating Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Duffield JS, Lupher M, Thannickal VJ, Wynn TA (2013) Host Responses in Tissue Repair and Fibrosis. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 8: 241–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reilkoff RA, Bucala R, Herzog EL (2011) Fibrocytes: emerging effector cells in chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 427–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, et al. (2004) The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol 25: 677–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mosser DM, Edwards JP (2008) Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 958–969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murray PJ, Wynn TA (2011) Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol 11: 723–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biswas SK, Mantovani A (2010) Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nature immunology 11: 889–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A (1994) Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Molecular Medicine 1: 71–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN (2001) Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. Journal of Immunology 166: 7556–7562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pilling D, Buckley CD, Salmon M, Gomer RH (2003) Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by serum amyloid P. Journal Of Immunology 17: 5537–5546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pilling D, Tucker NM, Gomer RH (2006) Aggregated IgG inhibits the differentiation of human fibrocytes. Journal Of Leukocyte Biology 79: 1242–1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shao DD, Suresh R, Vakil V, Gomer RH, Pilling D (2008) Pivotal Advance: Th-1 cytokines inhibit, and Th-2 cytokines promote fibrocyte differentiation. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 83: 1323–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schmidt M, Sun G, Stacey MA, Mori L, Mattoli S (2003) Identification of Circulating Fibrocytes as Precursors of Bronchial Myofibroblasts in Asthma. The Journal of Immunology 171: 380–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mehrad B, Burdick MD, Zisman DA, Keane MP, Belperio JA, et al. (2007) Circulating peripheral blood fibrocytes in human fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 353: 104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quan TE, Cowper S, Wu SP, Bockenstedt LK, Bucala R (2004) Circulating fibrocytes: collagen-secreting cells of the peripheral blood. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 36: 598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hashimoto N, Jin H, Liu T, Chensue SW, Phan SH (2004) Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in pulmonary fibrosis. Journal Of Clinical Investigation 113: 243–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, et al. (2004) Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J ClinInvest 114: 438–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moore BB, Murray L, Das A, Wilke CA, Herrygers AB, et al. (2006) The Role of CCL12 in the Recruitment of Fibrocytes and Lung Fibrosis. American Journal Of Respiratory Cell And Molecular Biology 35: 175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Crawford JR, Pilling D, Gomer RH (2012) FcγRI mediates serum amyloid P inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 92: 699–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crawford JR, Pilling D, Gomer RH (2010) Improved serum-free culture conditions for spleen-derived murine fibrocytes. Journal Of Immunological Methods 363: 9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naik-Mathuria B, Pilling D, Crawford JR, Gay AN, Smith CW, et al. (2008) Serum amyloid P inhibits dermal wound healing. Wound Repair and Regeneration 16: 266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pilling D, Roife D, Wang M, Ronkainen SD, Crawford JR, et al. (2007) Reduction of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by serum amyloid P. The Journal of Immunology 179: 4035–4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haudek SB, Xia Y, Huebener P, Lee JM, Carlson S, et al. (2006) Bone Marrow-derived Fibroblast Precursors Mediate Ischemic Cardiomyopathy in Mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103: 18284–18289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Steel DM, Whitehead AS (1994) The major acute phase reactants: C-reactive protein, serum amyloid P component and serum amyloid A protein. ImmunolToday 15: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pepys MB, Baltz M, Gomer K, Davies AJ, Doenhoff M (1979) Serum amyloid P-component is an acute-phase reactant in the mouse. Nature 278: 259–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Le PT, Muller MT, Mortensen RF (1982) Acute phase reactants of mice. I. Isolation of serum amyloid P- component (SAP) and its induction by a monokine. JImmunol 129: 665–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haudek SB, Trial J, Xia Y, Gupta D, Pilling D, et al. (2008) Fc Receptor Engagement Mediates Differentiation of Cardiac Fibroblast Precursor Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105: 10179–10184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Murray LA, Rosada R, Moreira AP, Joshi A, Kramer MS, et al. (2010) Serum Amyloid P Therapeutically Attenuates Murine Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis via Its Effects on Macrophages. PLoS ONE 5: e9683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Murray L, Kramer M, Hesson D, Watkins B, Fey E, et al. (2010) Serum amyloid P ameliorates radiation-induced oral mucositis and fibrosis. Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair 3: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Murray LA, Chen Q, Kramer MS, Hesson DP, Argentieri RL, et al. (2011) TGF-beta driven lung fibrosis is macrophage dependent and blocked by Serum amyloid P. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 43: 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Castano AP, Lin SL, Surowy T, Nowlin BT, Turlapati SA, et al. (2009) Serum amyloid P inhibits fibrosis through Fc gamma R-dependent monocyte-macrophage regulation in vivo. Science translational medicine 1: 5ra13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreira AP, Cavassani KA, Hullinger R, Rosada RS, Fong DJ, et al. (2010) Serum amyloid P attenuates M2 macrophage activation and protects against fungal spore-induced allergic airway disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126: : 712–721 e717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pilling D, Fan T, Huang D, Kaul B, Gomer RH (2009) Identification of markers that distinguish monocyte-derived fibrocytes from monocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts. PLoS ONE 4: e7475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ji Z, Ke ZJ, Geng JG (2011) SAP suppresses the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in C57BL/6 mice. Immunol Cell Biol 90: 388–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dillingh MR, van den Blink B, Moerland M, van Dongen MGJ, Levi M, et al. (2013) Recombinant human serum amyloid P in healthy volunteers and patients with pulmonary fibrosis. Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 26: 672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bharadwaj D, Mold C, Markham E, Du Clos TW (2001) Serum amyloid P component binds to Fc gamma receptors and opsonizes particles for phagocytosis. JImmunol 166: 6735–6741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grage-Griebenow E, Flad HD, Ernst M (2001) Heterogeneity of human peripheral blood monocyte subsets. JLeukocBiol 69: 11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chi M, Tridandapani S, Zhong W, Coggeshall KM, Mortensen RF (2002) C-reactive protein induces signaling through Fc gamma RIIa on HL-60 granulocytes. JImmunol 168: 1413–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mold C, Baca R, Du Clos TW (2002) Serum amyloid P component and C-reactive protein opsonize apoptotic cells for phagocytosis through Fcgamma receptors. Journal of autoimmunity 19: 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Macdonald SL, Kilpatrick DC (2006) Human serum amyloid P component binds to peripheral blood monocytes. Scand J Immunol 64: 48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV (2008) Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Biburger M, Aschermann S, Schwab I, Lux A, Albert H, et al. (2011) Monocyte Subsets Responsible for Immunoglobulin G-Dependent Effector Functions In Vivo. Immunity 35: 932–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ravetch JV, Kinet JP (1991) Fc receptors. AnnuRevImmunol 9: 457–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pilling D, Vakil V, Gomer RH (2009) Improved serum-free culture conditions for the differentiation of human and murine fibrocytes. Journal of Immunological Methods 351: 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cox N, Pilling D, Gomer RH (2012) NaCl Potentiates Human Fibrocyte Differentiation. PLoS One 7: e45674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Botto M, Hawkins PN, Bickerstaff MC, Herbert J, Bygrave AE, et al. (1997) Amyloid deposition is delayed in mice with targeted deletion of the serum amyloid P component gene. NatMed 3: 855–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Togashi S, Lim SK, Kawano H, Ito S, Ishihara T, et al. (1997) Serum amyloid P component enhances induction of murine amyloidosis. Lab Invest 77: 525–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Soma M, Tamaoki T, Kawano H, Ito S, Sakamoto M, et al. (2001) Mice lacking serum amyloid P component do not necessarily develop severe autoimmune disease. BiochemBiophysResCommun 286: 200–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yuste J, Botto M, Bottoms SE, Brown JS (2007) Serum amyloid P aids complement-mediated immunity to Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS Pathog 3: 1208–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walters DM, Kleeberger SR (2008) Mouse Models of Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53. Maharjan AS, Roife D, Brazill D, Gomer RH (2013) Serum amyloid P inhibits granulocyte adhesion. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 6: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Herlihy SE, Pilling D, Maharjan AS, Gomer RH (2013) Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV Is a Human and Murine Neutrophil Chemorepellent. The Journal of Immunology 190: 6468–6477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kebaier C, Chamberland RR, Allen IC, Gao X, Broglie PM, et al. (2012) Staphylococcus aureus α-Hemolysin Mediates Virulence in a Murine Model of Severe Pneumonia Through Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Journal of Infectious Diseases 205: 807–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Daubeuf F, Frossard N (2012) Performing Bronchoalveolar Lavage in the Mouse. Current Protocols in Mouse Biology: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57. Pilling D, Akbar AN, Girdlestone J, Orteu CH, Borthwick NJ, et al. (1999) Interferon-β mediates stromal cell rescue of T cells from apoptosis. European Journal Of Immunology 29: 1041–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Haston CK, Amos CI, King TM, Travis EL (1996) Inheritance of susceptibility to bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in the mouse. Cancer Res 56: 2596–2601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kumar RK (2005) Morphological methods for assessment of fibrosis. Methods MolMed 117: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hubner RH, Gitter W, El Mokhtari NE, Mathiak M, Both M, et al. (2008) Standardized quantification of pulmonary fibrosis in histological samples. Biotechniques 44: : 507–511, 514–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ding J, Yannam GR, Roy-Chowdhury N, Hidvegi T, Basma H, et al. (2011) Spontaneous hepatic repopulation in transgenic mice expressing mutant human α1-antitrypsin by wild-type donor hepatocytes. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 121: 1930–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, et al. (2007) TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med 13: 1324–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wynn TA, Barron L, Thompson RW, Madala SK, Wilson MS, et al.. (2011) Quantitative assessment of macrophage functions in repair and fibrosis. Current protocols in immunology/edited by John E Coligan [et al] Chapter 14: Unit14 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64. Gomer RH, Pilling D, Kauvar L, Ellsworth S, Pissani S, et al. (2009) A Serum Amyloid P-binding hydrogel speeds healing of partial thickness wounds in pigs. Wound Repair and Regeneration 17: 397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bickerstaff MC, Botto M, Hutchinson WL, Herbert J, Tennent GA, et al. (1999) Serum amyloid P component controls chromatin degradation and prevents antinuclear autoimmunity. NatMed 5: 694–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bygrave AE, Rose KL, Cortes-Hernandez J, Warren J, Rigby RJ, et al. (2004) Spontaneous autoimmunity in 129 and C57BL/6 mice-implications for autoimmunity described in gene-targeted mice. PLoSBiol 2: E243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Heidari Y, Bygrave AE, Rigby RJ, Rose KL, Walport MJ, et al. (2006) Identification of chromosome intervals from 129 and C57BL/6 mouse strains linked to the development of systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun 7: 592–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Carlucci F, Cortes-Hernandez J, Fossati-Jimack L, Bygrave AE, Walport MJ, et al. (2007) Genetic dissection of spontaneous autoimmunity driven by 129-derived chromosome 1 Loci when expressed on C57BL/6 mice. J Immunol 178: 2352–2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Van Molle W, Hochepied T, Brouckaert P, Libert C (2000) The Major Acute-Phase Protein, Serum Amyloid P Component, in Mice Is Not Involved in Endogenous Resistance against Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha-Induced Lethal Hepatitis, Shock, and Skin Necrosis. Infection and Immunity 68: 5026–5029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Kumar V, Abbas AK, et al.. (2005) Acute and Chronic Inflammation. Robbins and Cotran: Pathological Basis of Disease. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. pp. 47–86.

- 71. Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, et al. (2009) Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science 325: 612–616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Niedermeier M, Reich B, Rodriguez Gomez M, Denzel A, Schmidbauer K, et al. (2009) CD4+ T cells control the differentiation of Gr1+ monocytes into fibrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 17892–17897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Rose S, Misharin A, Perlman H (2012) A novel Ly6C/Ly6G-based strategy to analyze the mouse splenic myeloid compartment. Cytometry Part A 81A: 343–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Unkeless JC (1979) Characterization of a monoclonal antibody directed against mouse macrophage and lymphocyte Fc receptors. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 150: 580–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Keller R, Keist R, Bazin H, Joller P, van Der Meide PH (1990) Binding of monomeric immunoglobulins by bone marrow-derived mononuclear phagocytes; its modulation by interferon-γ. European Journal of Immunology 20: 2137–2140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Moore BB, Hogaboam CM (2008) Murine models of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Moeller A, Ask K, Warburton D, Gauldie J, Kolb M (2008) The bleomycin animal model: A useful tool to investigate treatment options for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis? The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 40: 362–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Wang D, Morales JE, Calame DG, Alcorn JL, Wetsel RA (2010) Transplantation of Human Embryonic Stem Cell-Derived Alveolar Epithelial Type II Cells Abrogates Acute Lung Injury in Mice. Mol Ther 18: 625–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mouratis MA, Aidinis V (2011) Modeling pulmonary fibrosis with bleomycin. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine 17: 355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Duan M, Li WC, Vlahos R, Maxwell MJ, Anderson GP, et al. (2012) Distinct Macrophage Subpopulations Characterize Acute Infection and Chronic Inflammatory Lung Disease. The Journal of Immunology 189: 946–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Gibbons MA, MacKinnon AC, Ramachandran P, Dhaliwal K, Duffin R, et al. (2011) Ly6Chi Monocytes Direct Alternatively Activated Profibrotic Macrophage Regulation of Lung Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184: 569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yona S, Kim K-W, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, et al. (2013) Fate Mapping Reveals Origins and Dynamics of Monocytes and Tissue Macrophages under Homeostasis. Immunity 38: 79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Johnston LK, Rims CR, Gill SE, McGuire JK, Manicone AM (2012) Pulmonary Macrophage Subpopulations in the Induction and Resolution of Acute Lung Injury. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 47: 417–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Duffield JS, Lupher ML Jr (2010) PRM-151 (recombinant human serum amyloid P/pentraxin 2) for the treatment of fibrosis. Drug News Perspect 23: 305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Pepys MB, Baltz ML, Musallam R, Doenhoff MJ (1980) Serum protein concentrations during Schistosoma mansoni infection in intact and T-cell deprived mice. I. The acute phase proteins, C3 and serum amyloid P-component (SAP). Immunology 39: 249–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Mortensen RF, Beisel K, Zeleznik NJ, Le PT (1983) Acute-phase reactants of mice. II. Strain dependence of serum amyloid P- component (SAP) levels and response to inflammation. JImmunol 130: 885–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Parker JC, Townsley MI (2004) Evaluation of lung injury in rats and mice. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology 286: L231–L246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kulkarni AA, Thatcher TH, Hsiao H-M, Olsen KC, Kottmann RM, et al. (2013) The Triterpenoid CDDO-Me Inhibits Bleomycin-Induced Lung Inflammation and Fibrosis. PLoS ONE 8: e63798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Schrier DJ, Kunkel RG, Phan SH (1983) The role of strain variation in murine bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. AmRevRespirDis 127: 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Chung MP, Monick MM, Hamzeh NY, Butler NS, Powers LS, et al. (2003) Role of repeated lung injury and genetic background in bleomycin-induced fibrosis. Am J RespirCell MolBiol 29: 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Haston CK, Wang M, Dejournett RE, Zhou X, Ni D, et al. (2002) Bleomycin hydrolase and a genetic locus within the MHC affect risk for pulmonary fibrosis in mice. HumMolGenet 11: 1855–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lu J, Marjon KD, Mold C, Du Clos TW, Sun PD (2012) Pentraxins and Fc receptors. Immunological Reviews 250: 230–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Savill J, Dransfield I, Gregory C, Haslett C (2002) A blast from the past: clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. NatRevImmunol 2: 965–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Lu J, Marnell LL, Marjon KD, Mold C, Du Clos TW, et al. (2008) Structural recognition and functional activation of FcgR by innate pentraxins. Nature 456: 989–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhang W, Xu W, Xiong S (2011) Macrophage Differentiation and Polarization via Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt–ERK Signaling Pathway Conferred by Serum Amyloid P Component. The Journal of Immunology 187: 1764–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]