Abstract

Pharmacological treatment of any maternal illness during pregnancy warrants consideration of the consequences of the illness and/or medication for both the mother and unborn child. In the case of major depressive disorder, which affects up to 10–20% of pregnant women, the deleterious effects of untreated depression on the offspring can be profound and long lasting. Progress has been made in our understanding of the mechanism(s) of action of antidepressants, fetal exposure to these medications, and serotonin’s role in development. New technologies and careful study designs have enabled the accurate sampling of maternal serum, breast milk, umbilical cord serum, and infant serum psychotropic medication concentrations to characterize the magnitude of placental transfer and exposure through human breast milk. Despite this progress, the extant clinical literature is largely composed of case series, population-based patient registry data that are reliant on nonobjective means and retrospective recall to determine both medication and maternal depression exposure, and limited inclusion of suitable control groups for maternal depression. Conclusions drawn from such studies often fail to incorporate embryology/neurotransmitter ontogeny, appropriate gestational windows, or a critical discussion of statistically versus clinically significant. Similarly, preclinical studies have predominantly relied on dosing models, leading to exposures that may not be clinically relevant. The elucidation of a defined teratological effect or mechanism, if any, has yet to be conclusively demonstrated. The extant literature indicates that, in many cases, the benefits of antidepressant use during pregnancy for a depressed pregnant woman may outweigh potential risks.

I. Introduction

A. Historical Perspective

Modern psychopharmacology began in the early 1950s with the introduction of chlorpromazine, followed by other phenothiazines, and by the end of the decade, the introduction of the tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) that gave clinicians new and effective tools to treat mental health disorders. Regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were establishing standards for reproductive safety categories (Table 1) for the use of drugs during pregnancy, underscoring the need to consider acute morphologic effects as well as potential long-term adverse effects of perinatal medication exposure.

TABLE 1.

U.S. FDA Use-in-Pregnancy Ratings

| Category | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| A | Controlled studies show no risk: Adequate, well-controlled studies in pregnant women have failed to demonstrate risk to the fetus. |

| B | No evidence of risk in humans: Either animal findings show risk, but human findings do not; or, if no adequate human studies have been done, animal findings are negative. |

| C | Risk cannot be ruled out: Human studies are lacking, and animal studies are either positive for fetal risk or lacking as well. However, potential benefits may justify the potential risk. |

| D | Positive evidence of risk: Investigational or postmarketing data show risk to the fetus. Nevertheless, potential benefits may outweigh risks. |

| X | Contraindicated in pregnancy: Studies in animals or humans, or investigational or postmarketing reports, have shown fetal risk that clearly outweighs any possible benefit to the patient. |

Source: Food and Drug Administration (2011).

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) were first introduced in 1959 (imipramine), with the active desmethyl metabolite of imipramine, desipramine, introduced in 1964 (Drugs Co, 1965). The timing of the introduction of TCAs and potential effects of TCA exposure in pregnancy coincided with the timing of the thalidomide tragedy, and there were early reports of potential limb anomalies associated with amitriptyline. In animal studies, it was observed that imipramine may have produced fetal abnormalities in rabbits (Robson and Sullivan, 1963). Dr. William McBride, who first reported deformities due to thalidomide, began examining mothers and their infants and reported increased limb deformities associated with iminodibenzyl hydrochloride (associated with TCA use) during pregnancy (McBride, 1972). The article was reported by several press agencies including The Times of London (March 4, 1972), spurring a reaction from physicians reporting the safety of these medications during pregnancy in their patients (Crombie et al., 1972; Kuenssberg and Knox, 1972; Levy, 1972; Sim, 1972). Notably, at the same time, the Lithium Registry of Babies (Schou et al., 1973) reported a higher rate of a specific cardiac defect, Ebstein’s Anomaly associated with lithium. This is still taught as dogma to young clinicians despite additional studies and critical reviews (Cohen et al., 1994) showing a more modest risk. These experiences contributed to increased reluctance to treat mood disorders in pregnancy as well as a decreased tendency to less aggressively treat nonthreatening conditions such as nausea. In both cases (vide infra), recent evidence suggests that untreated psychiatric disorders or nausea are associated with risk.

In 1987, the first selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), fluoxetine, was introduced in the United States. In the subsequent 26 years, the SSRIs have essentially replaced the TCAs in North America, much of Europe, and modern Asia as first- and second-line treatments for depression. Their widespread use for a variety of mood and anxiety disorders has been accompanied by significant utilization in the perinatal period. A review of health care data bases indicated that >6% of women were prescribed an antidepressant at some point during pregnancy (Andrade et al., 2008). The reproductive safety of the SSRIs has undergone considerable scrutiny utilizing a variety of methodologies, and unfortunately, only the studies demonstrating potential risk are highly publicized relative to studies reporting their apparent safety or lack of observed untoward effects.

B. Role of Serotonin in Development

“Teratogenic agents act in specific ways (mechanisms) on developing cells and tissues to initiate sequences of abnormal developmental events (pathogenesis).”—James G. Wilson, Environment and Birth Defects, 1973

The serotonin transporter is a sodium-serotonin symporter that transports serotonin from the extracellular space into the cell (Talvenheimo et al., 1979; Hoffman et al., 1991; Masson et al., 1999). After vesicular release of serotonin into the synaptic cleft, serotonin binds to pre- and postsynaptic serotonin receptors to mediate serotonin innervation (Pineyro and Blier, 1999). The most commonly used pharmacological treatment of depression currently relies on selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitors that act by binding to the serotonin transporter and preventing uptake of serotonin into the presynaptic neuron (Stafford et al., 2001). Increased serotonin in the synaptic cleft and activation of serotonergic receptors or local paracrine actions on neuronal migration represent the most probable mechanism(s) of action to induce developmental effects on the fetus.

Serotonin has diverse ontogeneological functions in utero to guide development. These functions should be considered in the context of laboratory and clinical evidence as a mechanistic approach to investigate the effects of in utero exposure to antidepressants. Serotonin increases neurite outgrowth ex vivo in mouse embryo thalamic neurons (Lotto et al., 1999). It is likely that the mechanism of this neurite extension is via serotonin-mediated stimulation of S100β release from astrocytes through 5-HT1A agonism (Whitaker-Azmitia, 2001). Serotonin also plays an important role in axonal guidance, because disruption of serotonin availability in the forebrain can lead to abnormal thalamocortical axon trajectories (Bonnin et al., 2007, 2011). Additionally, a switch from a placental source of serotonin to an endogenous fetal source of serotonin occurs in the second trimester of mice (Bonnin et al., 2011). Therefore, disruption of serotonin signaling during these critical times of development may form the basis of any underlying long-term effects on the fetus.

Another possible mechanism of antidepressant-mediated effects in utero is through direct effects on the uterus and uterine blood flow. The 5-HT2B receptor has been examined in human uterine smooth muscle cells and agonists increase phosphoinositide hydrolysis, which may lead to smooth muscle cell contraction (Kelly and Sharif, 2006). Serotonin produces relaxation of the porcine oviduct (Inoue et al., 2003) and inhibits myometrial contractility (Kitazawa et al., 1998), a finding somewhat at odds with the data above. These effects are antagonized by mianserin, a 5-HT receptor antagonist. Vedernikov et al. (2000) isolated uterine rings of Sprague-Dawley rats on gestational (G) days 14 and 21 and used these rings for isometric tension recording and direct stimulation of the uterine rings with serotonergic compounds. These studies and others would indicate that the serotonergic system has some role in uterine musculature. Not surprisingly, no effect was observed for direct application of fluoxetine, imipramine, nortriptyline; however, 5-HT itself also had no effect on uterine contractile activity on isolated uterine rings from rats. Ex vivo experimentation on human placentas revealed that a high concentration of doxepin, which possess both transporter antagonism as well as potent receptor antagonism at multiple targets (e.g., adrenergic, muscarinic, and histaminergic), decreases nonneuronal acetylcholine release. Although the clinical relevancy of the concentrations used are not clear, this has been speculated to be a possible mechanism for some clinical findings reporting low birth weight due to prenatal antidepressant exposure, because acetylcholine may control vascularization and alter energy availability to the fetus (Wessler et al., 2007). However, similar studies have not been performed using other antidepressants. In a prospective study of uterine and umbilical artery blood flow at 20 weeks gestation, there were no effects of maternal depression and SSRIs on indices of uterine or umbilical artery blood flow. However, bupropion had a very modest effect on decreasing uterine blood flow (Monk et al., 2012).

Serotonin also plays a role in the cardiovascular system. Serotonin receptors 5-HT1A, 5-HT3, and 5-HT7 have been shown to play a physiologic role in parasympathetic regulation of the cardiovascular system (Ramage and Villalón, 2008). Therefore, it has been posited that interference of this system in utero may disrupt normal development of the cardiovascular system. Sloot et al. (2009) treated whole-rat embryos in culture with 12 monoamine transporter inhibitors. The group found both cardiac defects and major malformations when treating these embryos. However, the lowest concentration of drug used was 0.3 µg/ml, which is approximately five to six times human exposure (Sloot et al., 2009). This article was disputed as not indicative of teratogenicity, because the concentrations used are much higher than clinically relevant serum concentrations, and it is unclear whether this is a direct effect of the drug or via SERT antagonism (Brent, 2010; Scialli and Iannucci, 2010).

James Wilson (1973) has identified six principles of teratology, and if a xenobiotic is thought to be teratogenic, it should attempt to satisfy these criteria. One of these principles posits that a xenobiotic must act by a defined cellular mechanism to initiate abnormal developmental effects (Wilson, 1973). Current and future studies investigating in utero exposure of antidepressants must consider that if there is a teratogenic mechanism, presumably via increased synaptic 5-HT concentrations, it has not been thoroughly investigated or replicated.

II. Animal Exposure Studies

There are several requisite components in understanding the potential relevance of preclinical data for import into the clinical decision including: 1) comparison of developmental time points; 2) clinical relevance of exposure; and 3) outcomes of interest across species.

A. Translation of Development between Animals and Humans

Translating equivalent gestational time points of neurodevelopment across mammalian species is problematic because of a human fetus's rapid neural development in gestation compared with other animals (Gottlieb et al., 1977; Clancy et al., 2001). For comparison of rats and humans, different morphologic characteristics can be compared but there is no numeric relationship that could easily compare rat development and human development (e.g., 30 human years ≈ 1 rat year), and to do so would oversimplify the field of embryology. However, brain growth velocity peaks at birth for humans, whereas for rats, growth rate peaks on postnatal day (PND) 8, with further spurts of growth postnatally. In contrast, multiple markers of neural development in the hippocampus suggest that prenatal and postnatal development have remarkably similar temporal patterns in rats and humans (Avishai-Eliner et al., 2002). Because no ontogeneological data are available on the development of the prenatal serotonin system in humans, for the purpose of this review, it is reasonable to consider the first few postnatal weeks in rodents to be similar to the very end of human gestation (reviewed in (Watson et al., 2006). However, the in utero environment is not present during the first postnatal week of a rodent’s life, and therefore, exposure studies are complicated by difficulties in maintaining clinically relevant exposure of the offspring to medications following birth. Therefore, this review will focus on in utero animal exposure as a translatable approach to present findings from animal studies using these compounds (Tables 2 and 3).

TABLE 2.

Summary of endpoints after prenatal tricyclic/tetracyclic antidepressant exposure in animals

| Drug | Species | Dose (mg/kg per day) | Route | Exposure | Maternal Serum Monitored for Drug Conc. | 5-HT | NE | DA | Behavior | Cardio | Health | Endpoint | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLO, IPD, MNS | Rat | 10 | SC | G6–G21 | No | + | + | + | ø | P25 | De Ceballos et al., 1985b | ||

| AMI | Rat | 10 | SC | G2–G21 | No | + | ø | P60 | Henderson et al., 1993 | ||||

| CLO, DSP, NOM | Rat | 10 | OG | G6–G21 | No | + | P25 | Montero et al., 1990 | |||||

| AMI | Rat | 10 | SC | G2–G21 | No | ø | ø | ø | P30, 60, 180 | Henderson et al., 1991 | |||

| CLO, IPD, TNP | Rat | 10 | SC | G6–G21 | No | ø | P25 | Montero et al., 1991 | |||||

| IMI | Rat | 15 | OG | G8–G20 | No | + | + | + | + | P14, 30 | Jason et al., 1981 | ||

| IMI | Rat | 0, 5, 10 | SC | G8–G20 | No | + | ø | + | ø | P1, 7 | Ali et al., 1986 | ||

| IMI | Rat | Unknown | DW | G0–P21 | No | ø | ø | P290 | Tonge, 1972, 1973 | ||||

| IMI | Rat | 0, 5, 10 | SC | G8–G20 | No | ø | + | ø | P4, 7 | Harmon et al., 1986 | |||

| CLO, NOM, IPR, MNS | Rat | 10 | SC | G6–G21 | No | + | + | P25 | De Ceballos et al., 1985a | ||||

| DSP | Rat | 10 | SC | G8–G20 | No | ø | ø | ø | P20 | Stewart et al., 1998 | |||

| IMI | Rat | 5 | OG | G14–G19 | No | + | + | P21 | Coyle, 1975 | ||||

| CLO | Rat | 3, 10, 30 | IP | G8–G21 | No | + | + | P35 | File and Tucker, 1983 | ||||

| DSP, MNS, VX | Rat | 1.25/5/10 | SC | G8–G20 | No | + | + | P23, 60 | Cuomo et al., 1984 | ||||

| AMI | Rat | 10 | SC | G2–G21 | No | + | + | P30 | Henderson et al., 1990 | ||||

| CLO | Rat | 3 | DW | G14–P2 | No | + | ø | P50, 110 | Rodríguez et al., 1983 | ||||

| IMI | Rat | 5 | OG | G21–P25 | No | + | P25, 80 | Coyle and Singer, 1975a | |||||

| CLO | Rat | 7.5, 15 | IP | G8–G21 | No | + | P32, P42 | File and Tucker, 1984 | |||||

| IMI | Rat | 5 | OG | G14–G19 | No | ø | + | P60 | Coyle and Singer, 1975b | ||||

| DOX, IMI | Rat | 30 | IP | Varied | No | + | + | P35–70 | Simpkins et al., 1985 | ||||

| AMI | Hamster | 75 | IP | G8 | No | + | G15 | Beyer et al., 1984 | |||||

| IMI | Rat | 5, 15, 30 | SC | G21–G21 | No | + | P1 | Singer and Coyle, 1973 | |||||

| IMI | Rat | 10 | IP | G9–G11 | No | + | G21 | Swerts et al., 2010 | |||||

| IMI | Rat | 5 | SC | G1–21 | No | +, ø | P56, 90 | Fujii, 1997; Fujii and Ohtaki, 1985 | |||||

| IMI | Primate | 20–244 | OG | Varied | No | ø | NA | Hendrickx, 1975 |

+, Positive association; ø, null association; AMI, amitriptyline; CLO, clomipramine; DSP, deprenyl; DOX, doxepin; DSP, desipramine; DW, drinking water; G, gestation day; IMI, imipramine; IP, intraperitoneal; IPD, iprindole; MNS, mianserin; NOM, nomifensine; OG, oral gavage; P, postnatal day; SC, subcutaneous; TNP, tianeptine; VX, viloxazine.

TABLE 3.

Summary of endpoints after prenatal SSRI exposure in animals

| Drug | Species | Dose | Administration | Exposure | Maternal Serum Monitored for Drug Conc. | 5-HT | DA | Behavior | Cardio | Health | Endpoint | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/kg | ||||||||||||

| FLX, FVA | Mouse | 0–4.2 | IP | G8–G18 | Placental transfer | + | + | + | + | P20, P90 | Noorlander et al., 2008 | |

| ESC, FLX, PRX, SRT, VEN | Rat | 3–80 | OM | G12–G21 | Yes | + | ø | ø | G21–P7, P70–P100 | Capello et al., 2011 | ||

| FLX | Rat | 10 | OM | G14–P7 | No | + | + | + | P30–P120 | Forcelli and Heinrichs, 2008 | ||

| CIT | Rat | 0–20 | SC | G11–P21 | No | + | + | P22–P25 | Simpson et al., 2011 | |||

| FLX | Rat | 2.5 | OG | G6–G21 | No | + | P25 | Montero et al., 1990 | ||||

| FLX | Rat | 10 | SC | G13–G20 | No | + | P26, P70 | Cabrera-Vera et al., 1997 | ||||

| FLX | Rat | 10 | SC | G13–G20 | No | + | P26 | Cabrera-Vera and Battaglia 1998 | ||||

| ZIM | Rat | 5 | SC | G10–G20 | No | ø | +, ø | P20–P90 | Grimm and Frieder, 1987 | |||

| FLX | Rat | 12.5 | OG | G8–G20 | No | ø | ø | ø | P20 | Stewart et al., 1998 | ||

| FLX | Rat | 8, 12 | DW | G6–G20 | No | + | + | P18–P56 | Bairy et al., 2007 | |||

| FLX | Mouse | 5, 10 | SC | G13–G20 | No | + | + | P1–P120 | Cagiano et al., 2008 | |||

| FLX | Guinea pig | 7 | OM | G1–G54 | No | + | ø | P63 | Vartazarmian et al., 2005 | |||

| FLX | Mouse | 7.5 | OG | G0–P21 | No | + | ø | P40, P70 | Lisboa et al., 2007 | |||

| FLX | Mouse | 7.5 | OG | G0–P20 | No | + | P90 | Gouvêa et al. 2008 | ||||

| FLX | Rat | 10 | IP | G13–G21 | No | + | P56 | Singh et al., 1998 | ||||

| FLX | Sheep | 0.099 | IV | G120–G128 | Yes | + | G128 | Morrison et al., 2001 | ||||

| FLX | Mouse | 7.5 | OG | G0–P21 | No | +, ø | + | P40 | Favaro et al., 2008 | |||

| PRX | Mouse | 30 | Chow | G14–G16.5 | Yes | +, ø | P13–P90 | Coleman et al., 1999 | ||||

| FLX | Sheep | 0.099 | IV | G120–-G128 | Yes | ø | ø | G128 | Morrison et al., 2005 | |||

| PRX | Mouse | 30 | Chow | G14–P0 | No | ø | P34–P105 | Christensen et al., 2000 | ||||

| FLX | Rat | 10 | OG | G11–G21 | No | + | + | G21–P3 | Fornaro et al., 2007 | |||

| FLX, VEN | Rat | 8–80 | OG | G15–G20 | No | + | P1 | da-Silva et al.1999 | ||||

| FLX | Sheep | 0.099 | IV | G120–G128 | Yes | + | G128 | Morrison et al., 2004 | ||||

| FLX | Mouse | 10 | DW | G0–G21 | No | + | G14, G21 | Bauer et al., 2010 | ||||

| FLX | Rat | 10 | IP | G0–BF | No | + | P3–P30 | Periera et al., 2007 | ||||

| PRX | Rat | 10 | DW | G14–G21 | No | + | P0 | Van den Hove et al., 2008 | ||||

| FLX | Rat | 10 | IP | G9–G11 | No | ø | G21 | Swerts et al., 2010 | ||||

| FLX | Rat/rabbit | 0–15 | OG | G6–G15 | No | ø | G20/G28 | Byrd and Markham, 1994 |

+, Positive association; ø, null association; BF, breast feeding; CIT, citalopram; DW, drinking water; ESC, escitalopram; FLX, fluoxetine; FVA, fluvoxamine; G, gestation day; IV, intravenous; IP, intraperitoneal; OG, oral gavage; OM, subcutaneous osmotic minipump; P, postnatal day; SC, subcutaneous; SRT, sertraline; VEN, venlafaxine; ZIM, zimelidine.

B. Exposure Studies

Studies in laboratory animals are vital to investigate the possible effects of prenatal antidepressant exposure. However, translatable exposure concentrations between animals and humans can be difficult attributable to differences in pharmacokinetics between species.

C. Tricyclic/Tetracyclic Antidepressant Animal Studies

The majority of TCA prenatal exposure studies in animals have relied upon single, daily administration of the compound or dissolving the compound in drinking water. To extrapolate animal data and apply it to the human population, exposure studies should rely on a clinically relevant dosing model that approximates human exposure. Pharmacokinetics dictates that there is a bolus effect after a single injection that may lead to suprapharmacological exposures and possible acute toxicity. Most xenobiotics are more quickly metabolized in laboratory animals compared with humans and dosing paradigms must attempt to maintain exposure throughout the dosing interval. Animal exposure studies investigating non–SSRI drugs have largely focused on imipramine, which is metabolized into desipramine. Desipramine and imipramine are norepinephrine transporter antagonists, although imipramine potently inhibits the serotonin transporter as well (Owens et al., 1997). Devane and Simpkins (1985) used a bolus injection of imipramine in pregnant rats to show imipramine and desipramine at higher concentrations in the fetal brain than the maternal serum, indicating, unsurprisingly, that these medications pass readily through the placenta and expose the offspring to a significant dose (DeVane and Simpkins, 1985). Because of the lipophilic nature of most psychotropic drugs, concentrations in brain tissue are frequently much higher than in serum or cerebrospinal fluid, but it is only drug in the brain extracellular fluid compartment that has access to its target and not that intercalated nonspecifically in lipid membranes, both of which are measured by studies utilizing “brain” concentration data. Nevertheless, studies measuring brain concentrations signify brain exposure. When administered intraperitoneally to a pregnant rat, a 30 mg/kg dose of imipramine on G18–19 resulted in ∼0.5 µg/ml in the dam plasma, ∼20 µg/ml in the maternal brain as well as a persistent (>5 µg/ml) concentration of its active metabolite desipramine for 18 hours (DeVane et al., 1984). A 10 mg/kg dose of imipramine or desipramine administered intramuscularly during the third trimester of pregnancy resulted in significant placental transfer with significant concentration in the fetal serum (2 µg/ml in fetal plasma, 1 µg/ml in maternal plasma for imipramine) (Douglas and Hume, 1967; Hume and Douglas, 1968). These studies indicate significant placental transfer in rodents, similar to clinical data.

D. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Antidepressant Animal Studies

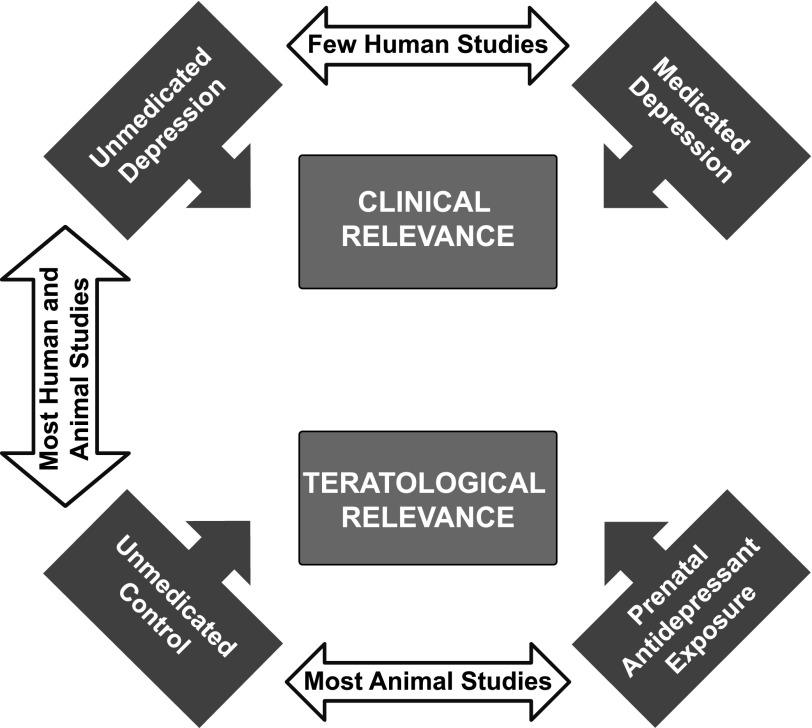

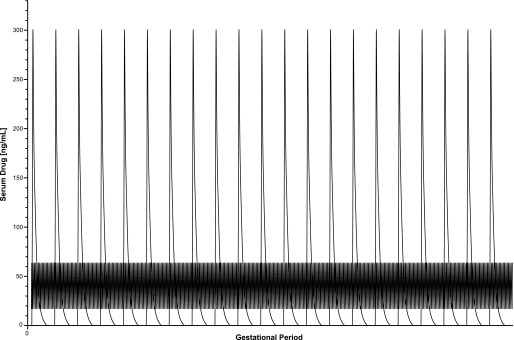

The majority of SSRI animal studies have used a model of daily injections subcutaneously or intraperitoneally to investigate the effects on the pups. As noted above, daily injections in rodents are problematic because of bolus effects that may lead to transient, possibly toxic, serum concentrations of the compound. In contrast, human exposure leads to lower Cmax and steadier serum concentrations of the compound compared with rodents (Fig. 1). Similar to TCA studies, some SSRI antidepressants have active metabolites with relatively long half-lives; this is particularly true for fluoxetine and the active metabolite norfluoxetine (half-life ∼24 hours in rats), which shares nearly identical pharmacology with fluoxetine (Owens et al., 1997). Recently, animal exposure studies using SSRIs have begun to devise more steady exposure models and measure serum concentrations of compounds to quantify the level of exposure (Bourke et al., 2013a).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of human and rat pharmacokinetics of the antidepressant escitalopram during pregnancy. Based on the published half-life of escitalopram and observed peak and trough serum concentrations observed in humans and rats. Theoretical serum sampling of escitalopram after single injections (10 mg/kg free base) during pregnancy in rats would yield a peak bolus concentration of approximately 300 ng/ml followed by rapid clearance. The clinically observed range of escitalopram in human women with no attention paid to time of sampling reveals peak serum concentrations of ∼65 ng/ml and trough serum concentrations of ∼17 ng/ml.

Studies quantifying exposure in animals are, unfortunately, uncommon. Continuous infusion of fluoxetine in sheep via maternal femoral vein catheter yielded concentrations in maternal and fetal serum of ∼150 and ∼60 ng/ml, respectively; no measurements of norfluoxetine were obtained (Morrison et al., 2004). Similar results were found in mice: placental transfer of fluoxetine was 69%, whereas human placental transfer is 73% (Noorlander et al., 2008). Placental transfer comparing rodents and humans is also reported for fluvoxamine (30% in mice, 35% in humans). Comparing maternal serum concentrations and amniotic fluid concentrations, our group observed variable placental transfer depending on the antidepressant used (Capello et al., 2011).

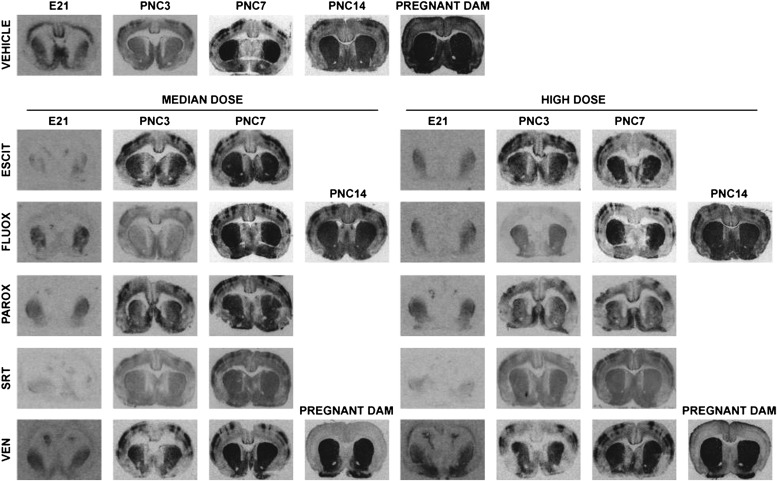

Only recently has the degree of central nervous system (CNS) exposure been quantified in response to these data on placental transfer (Fig. 2). Although we observed variable placental transfer, fetal CNS exposure is similar to that of the pregnant dam (Capello et al., 2011). Direct measurement of monoamine transporter occupancy in human infants would be limited to postabortion tissue, and radioligand studies (e.g., PET) are not feasible in the intact fetus or neonate. Whether whole-blood serotonin concentrations are a viable proxy is unknown. Our group has quantified SERT occupancy in rat pups after continuous prenatal exposure to SRIs. Osmotic minipumps were used to administer steady serum concentrations similar to human exposure, and this resulted in approximately 80–95% occupancy of the serotonin transporter in embryonic day 21 pups (the end of gestation). This is essentially the same SERT occupancy in embryonic day 21 pups and their dams. Postnatally, SERT occupancy rapidly dropped after parturition as predicted from the pharmacokinetics of the drugs in rodents. Exposure via breast milk resulted in measurable but generally low SERT occupancy (Capello et al., 2011). This was demonstrated independently for escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine (Fig. 2). These data indicate that CNS exposure in utero to SRIs is similar between dams and their fetuses. In contrast, the postnatal only exposure via lactation did not result in SERT occupancy at the level observed therapeutically in humans. The presence of SERT occupancy in the pups exposed only via lactation is measurable even if serum drug concentrations are below the limit of detection. These data would suggest CNS exposure in humans occurs and that the undetectable levels for most antidepressants in human nursing infants may still be associated with some degree of CNS exposure. The magnitude of this exposure and its physiologic relevance are not known but are much less than that targeted for therapeutic activity in adults.

Fig. 2.

Representative autoradiographs of in utero exposure to SRIs. Representative autoradiographs of escitalopram (ESCIT), fluoxetine (fluoxetine), paroxetine (PAROX), sertraline (SRT), and venlafaxine (VEN), including representative pregnant dams exposed to VEN during pregnancy. Each treatment group had its own vehicle run in the same assay, but one series is shown for reference. Total binding representative images are displayed for comparison. Dense patches of total binding in the somatosensory cortex are consistent with previous studies investigating SERT binding during the early postnatal period (D'Amato et al., 1987; Kelly et al., 2002). PNC, postnatal clearance. Adapted from Capello et al. (2011).

E. Growth, Developmental, Gross Anatomical, and Physiological Outcomes

Gross anatomic differences due to prenatal NRI exposure have been investigated in animal models. Changes in birth weight or growth attributed to prenatal NRI exposure have been reported in the clinical literature. Animal studies show conflicting results; some report no changes in pup weight or litter size (Rodríguez Echandía and Broitman, 1983; De Ceballos et al., 1985b; Harmon et al., 1986; Stewart et al., 1998), an increase in fetal and neonatal weights (Cuomo et al., 1984; Swerts et al., 2010), or reduced birth weight in pups and reduced litter size (Singer and Coyle, 1973; Jason et al., 1981; Simpkins et al., 1985; Henderson and McMillen, 1990). Congenital malformations have also been investigated in prenatal exposure animal studies, showing a hint of encephalocele in Golden hamsters prenatally exposed to a single suprapharmacological (70.3 mg/kg) dose of amitriptyline (Beyer et al., 1984). Another study investigating teratological outcomes observed no differences due to prenatal exposure to imipramine in Bonnet or Rhesus primates at a dose of 244 mg/kg per day (Hendrickx, 1975). An important aspect of the thalidomide tragedy was the choice of the test species; rats and mice were not susceptible to the teratogenic effects, whereas rabbits and nonhuman primates were susceptible (Delahunt and Lassen, 1964; Fratta et al., 1965; Schumacher et al., 1968). Prenatal NRI exposure studies investigated several test species without showing any reproducible teratogenicity.

The noradrenergic system participates in thermoregulation and, therefore, has been examined in the context of prenatal NRI exposure (Mills et al., 2004). Adult male rat offspring prenatally exposed to imipramine displayed a baseline hyperthermic (difference of 1.31°C from controls) body temperature (Fujii and Ohtaki, 1985). Additionally, prenatal exposure resulted in a hyperthermic reaction to chlorpromazine (control rats were hypothermic in response to chlorpromazine), and this effect was observed on PND57 and persisted through PND90 (Fujii and Ohtaki, 1985; Fujii, 1997). Female control and females prenatally exposed to imipramine had a hypothermic response similar to male controls, indicating a sex-specific difference in thermoregulation in response to prenatal exposure.

Cardiovascular function is strongly regulated by norepinephrine (Singewald and Philippu, 1996), and some have hypothesized that disturbances in catecholamine homeostasis due to prenatal antidepressant exposure may alter cardiovascular function in the offspring. Prenatal exposure to 10 mg/kg imipramine from G8 to G20 has been shown to reduce heart weight in neonatal rats (Harmon et al., 1986). Another study examining prenatal doxepin or imipramine exposure found no differences measured in systolic blood pressure, but early prenatal exposure to doxepin increased offspring heart rate measured between PND35 and 70. Testing of aortal tissue in vitro revealed that third trimester exposure to doxepin or imipramine increased isoproterenol-induced relaxation of aortic tissue, but direct measurement of β-adrenergic receptor function or binding density was not undertaken (Simpkins et al., 1985). These studies demonstrate a role of prenatal antidepressant (TCA) exposure in the development of the cardiovascular system, whereby changes in the prenatal environment may cause long-term cardiovascular alterations; the physiologic significance is unclear.

Morrison and colleagues (2001) used Dorset Suffolk sheep and continuous infusion of fluoxetine to examine sleep endpoints. During the last trimester, a bolus injection of fluoxetine was administered followed by 8 days of continuous intravenous infusion. The measured plasma concentration of fluoxetine in the ewe was 106 ng/ml, whereas the fetal fluoxetine concentration was 58 ng/ml, showing substantial fetal transfer as expected. Fluoxetine infusion disrupted fetal sleep measured by low-voltage and high-voltage electrocortical activity (Morrison et al., 2001). A follow-up study showed no alterations in fetal plasma melatonin or prolactin during the infusion. No differences were observed in fetal behavioral state, fetal arterial pressure, heart rate, breathing, or circadian rhythm (Morrison et al., 2005).

The clinical literature has, for the most part, focused on gross indices of development such as weight, growth, or fetal mortality. Several animal studies examined these properties in the context of prenatal SSRI exposure with conflicting results. Impaired weight gain, low birth weight, or small litter size after prenatal SSRI exposure has been reported in several studies (da-Silva et al., 1999; Bairy et al., 2007; Pereira et al., 2007; Cagiano et al., 2008; Favaro et al., 2008; Forcelli and Heinrichs, 2008; Noorlander et al., 2008; Van den Hove et al., 2008; Bauer et al., 2010), whereas other studies observe no differences in weight gain or birth weight (Byrd and Markham, 1994; Stewart et al., 1998; Vartazarmian et al., 2005; Lisboa et al., 2007). Congenital malformations are reported in the clinical literature but have only been reported in the animal literature by extracting and exposing mouse embryos in vitro to 20 times the clinically observed serum concentration of sertraline for 48 hours (Shuey et al., 1992). Current studies do not support a role of clinically relevant exposure to SSRIs as a cause of congenital malformations or overt, long-term developmental consequences.

These data are consistent with the human literature suggesting alterations in sleep architecture, although the effects appear to be time limited and not associated with persistent alterations. The pup outcome data, like the human data, are also discordant. However, low birth weight in several studies is consistent with several of the clinical reports. The congenital malformation data are difficult to interpret given the relatively massive exposure that would be more consistent with daily overdose in a clinical population. Notably, the reported defects are not consistent with the purported cardiovascular defects in the human literature (see below and reviewed later).

F. Cardiovascular Outcomes

Chambers et al. (2006) reported that some children exposed prenatally to SSRIs after 20 weeks gestation displayed persistent pulmonary hypertension. Only two animal studies have tried to mechanistically determine the effects of prenatal antidepressant exposure on cardiovascular and pulmonary endpoints. Mice prenatally exposed to fluoxetine exhibited pulmonary hypertension as measured by increased right ventricle: left ventricle + septum ratio or pulmonary arterial medial thickness. Functionally, pulmonary arterial smooth muscle response to serotonin was significantly reduced. The lung concentration of serotonin was unaltered by prenatal exposure, but placental serotonin content was significantly reduced; the role of placental serotonin on cardiovascular development is unclear. Fetal mortality was increased in the first 3 days of life following fluoxetine exposure (0% in controls compared with 15% in fluoxetine-exposed pups). Newborn arterial oxygen saturation was lower in fluoxetine-exposed pups, but this normalized by the 3rd day of life. These findings were noted to be strongly indicative of pulmonary hypertension (Fornaro et al., 2007). Noorlander et al. (2008) also reported that mice prenatally exposed to fluoxetine manifested decreased left ventricle wall thickness, a measure of dilated cardiomyopathy, on PND20 and 90. These findings provide some concordant data regarding persistent pulmonary hypertension reported in the clinical population.

The issue of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) is of serious concern and, thankfully, a relatively rare clinical condition affecting 1:1000. The limited preclinical data do suggest that more subtle changes in the cardiovascular/pulmonary systems (e.g., nonteratogenic) may be a consequence of prenatal SSRI exposure as noted in a recent review (Occhiogrosso et al., 2012).

G. In Utero Exposure and Effects on Monoaminergic Function: Molecular and Biochemical Outcomes

Initial radioligand binding and catecholamine detection studies of prenatal antidepressant exposure investigated catecholamine function in the context of receptor binding, affinity, and catecholamine concentrations. Several studies have shown reduced [3H]imipramine (used as a marker for the SERT), β-adrenergic, and dopamine receptor (D2) binding after prenatal NRI exposure (Jason et al., 1981; De Ceballos et al., 1985b; Ali et al., 1986; Montero et al., 1990), but other studies observed no changes in D1 or D2 receptor binding (Henderson et al., 1991; Stewart et al., 1998), adrenergic receptor binding (Harmon et al., 1986; Henderson et al., 1991), or 5-HT2 receptor binding (Henderson et al., 1991). These measures in offspring were conducted during the late postnatal period, up to PND25, and therefore may not be long-term alterations persisting into adulthood but may still be important for normal development. Dopamine affinity for dopamine receptors was reported to be increased by prenatal NRI exposure (De Ceballos et al., 1985a); however, a mechanistic explanation on how this (a change in affinity) is physically accomplished is unclear. Norepinephrine and dopamine concentrations in several brain areas in adolescent and adult male rats and norepinephrine turnover were shown to be unaffected by prenatal exposure to imipramine (Tonge, 1972, 1973; Ali et al., 1986), although another study reported reduced hypothalamic dopamine concentrations on PND30 (Jason et al., 1981). NRIs typically have weak activity for the serotonin transporter. 5-HT1B receptors have been shown to be unaffected by prenatal clomipramine exposure (Montero et al., 1991) but 5-HT and its metabolite, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, were reduced in the striatum on PND60 following prenatal amitriptyline exposure (Henderson and McMillen, 1993); amitriptyline has SERT and NET antagonism properties, and its metabolite, nortriptyline, is a potent NET antagonist. These studies indicate some effects of prenatal NRIs on central adrenergic function, but the physiologic significance is unclear.

Two studies investigating the serotonergic system after prenatal fluoxetine exposure have been conducted by Battaglia and colleagues (Cabrera-Vera and Battaglia, 1998). Prenatal exposure via maternal fluoxetine injection resulted in an increased density of [3H]citalopram-labeled SERT sites in the CA2 (+47%) and CA3 (+38%) areas of the hippocampus, as well as the basolateral (+32%) and medial (+44%) amygdaloid nuclei in prepubescent progeny. In the diencephalon, the lateral hypothalamus displayed an increased SERT density (+21%) in prepubescent progeny. In contrast, the density of 5-HT transporters was significantly decreased in the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (−21%) and in the substantia nigra (−19%) in prepubescent progeny. At PND90, there were no significant differences between control and fluoxetine animals (Cabrera-Vera and Battaglia, 1998). This model also resulted in 28% reduction in 5-HT content in the frontal cortex of prepubescent offspring and the midbrain of adult progeny as well as attenuated p-chloroamphetamine-induced reduction in midbrain 5-HT content (Cabrera-Vera et al., 1997). The physiologic significance of these changes is unknown.

After prenatal fluoxetine exposure, rats exhibited a lower Bmax of [3H]imipramine binding sites (predominantly SERT) in the cerebral cortex up to PND25 compared with controls, indicative of a reduction in SERT expression and opposite of that reported by Cabrera-Vera and Battaglia (1998) and Montero et al. (1990). Pregnant rats exposed to a steady concentration of 10 mg/kg per day of fluoxetine from osmotic minipumps resulted in decreased cell count in the nucleus accumbens and decreased SERT immunoreactivity in the raphe on PND120 (Forcelli and Heinrichs, 2008). The serum concentrations of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine were not determined in this study, but our experience suggests that this may be a clinically relevant exposure. A similar study examining prenatal fluvoxamine exposure reported decreased SERT immunoreactivity in the raphe on PND20 and 90 (Noorlander et al., 2008). Only one study has investigated nonserotonergic receptors and reported no changes in D1 or D2 receptor binding in the striatum on PND20 after prenatal fluoxetine exposure (Stewart et al., 1998). Other non–CNS studies of monoamine systems have shown that vas deferens tissue from PND30 rats exhibited decreased affinity for 5-HT, norepinephrine, and phenylephrine using a bioassay, but as noted earlier, changes in affinity are difficult to reconcile mechanistically (Pereira et al., 2007). Prenatal fluoxetine exposure seems to selectively affect the serotonergic system but not other monoaminergic systems. In the absence of other data, this is likely true for all of the SSRIs as they generally share a very similar pharmacology.

The known serotonergic regulation of the HPA axis (Owens et al., 1991a,b) led Morrison and colleagues (2004) to investigate pituitary and adrenal output in the context of prenatal fluoxetine exposure. During continuous infusion of fluoxetine to pregnant sheep, on certain days, fluoxetine decreased plasma ACTH concentrations compared with preinfusion day but not compared with control in the pregnant sheep. In the fetus, basal plasma ACTH concentrations were increased on G127 compared with preinfusion day. Cortisol was unaffected in the ewes, but on G127 and 128, fetal cortisol in fluoxetine-exposed animals was significantly elevated compared with controls (Morrison et al., 2004). Further studies of the HPA axis may help elucidate the function of the developing serotonin system on the fetal HPA axis.

Serotonin’s role in early development has been explored using prenatal citalopram exposure. Simpson and colleagues (2011) examined prenatal and postnatal exposures to citalopram and its possible effects on cortical network functioning in rats. A comparison of gestational citalopram exposure and postnatal (PND8–21) exposure showed disruptive behavioral effects of postnatal exposure only. Additionally, abnormal callosal connectivity was observed in postnatally exposed animals (Simpson et al., 2011). This study describes an exquisitely regulated developmental system with serotonin at the center. However, because the effects were mostly ascribed to the postnatal exposure period and two daily 10 mg/kg bolus injections were used for citalopram exposure, direct translation to prenatal antidepressant exposure is uncertain as is the overall clinical relevance.

Our group recently conducted studies on the long-term effects of prenatal antidepressant and/or stress exposure in rats. After steady exposure to escitalopram throughout pregnancy and/or chronic variable stress exposure, the offspring were analyzed in adulthood. Adult male rats had no significant changes in gene expression using a microarray and real-time PCR in the hippocampus, hypothalamus, or amygdala due to prenatal stress and/or escitalopram exposure. Behavior was also unaffected by prenatal treatments. After stimulation of the HPA axis with an acute air puff startle, plasma ACTH and cortisol concentrations were not physiologically affected by prenatal stress and/or escitalopram exposure (Bourke et al., 2013b).

These data, similar to the human data, indicate that antidepressant exposure in pregnancy can influence some measures of monoaminergic function and, albeit inconsistent between the preclinical and clinical data, some degree of effects on measures of neuroendocrine function.

H. Behavioral Outcomes

Disrupted behavior in laboratory animals may indicate a phenotypic difference due to prenatal antidepressant exposure. Several groups have investigated exploratory behaviors and social interaction after prenatal NRI exposure. The open-field test for rodents is used to measure exploratory behavior in a novel environment (possible inquisitive/anxiety-like behavior), and several groups have reported that prenatal NRI exposure decreased rearing behavior in adolescence (Coyle, 1975; File and Tucker, 1983; Drago et al., 1985). Prenatal NRI exposure also decreased exploration in adolescence and adulthood in male rats (Rodríguez Echandía and Broitman, 1983). Additionally, prenatal and prenatal + lactational NRI exposure to 3 mg/kg chloroimipramine delivered via tap water produced similar effects while lactation alone did not, indicating that exposure via lactation as predicted from earlier studies of quantifying exposure may not produce any behavioral effects (Rodríguez Echandía and Broitman, 1983). Measures of social interaction were shown to be increased in adolescence due to prenatal NRI exposure (File and Tucker, 1983, 1984) in male and female rats. However, other groups report the opposite: prenatal NRI exposure decreased social interaction in adolescence and adulthood in male rats (Coyle and Singer, 1975b; Rodríguez Echandía and Broitman, 1983).

The antidepressant neonatal syndrome was first reported in 1973 (Webster, 1973) with imipramine, and more recently, it has garnered considerable attention (Moses-Kolko et al., 2005). Clinically, the description has consistently included jitteriness and twitching. Although we do not believe that this is the classic “serotonin syndrome,” it may be indicative of alterations in the 5-HT system. Animal studies have recapitulated the classic “serotonin syndrome” through postnatal coadministration of clorgyline, a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, followed by administration of 5-hydroxytryptophan, the immediate precursor of serotonin. De Ceballos et al. (1985b) explored this in rats as a measure of the involvement of the developing serotonin system. Prenatal chloroimipramine, a potent SRI with some NRI activity, prevented drug-induced serotonin syndrome-like behaviors such as head twitches and a resting tremor. However, the 5-HT2 antagonists, iprindole or mianserin, both potentiated animal measures of a serotonin syndrome. Nomifensine, an NRI/dopamine reuptake inhibitor, had no effect on the behavioral characteristics of the serotonin syndrome. Although the conflicting effects seen in this study preclude a definitive interpretation, there does seem to be a serotonergic influence on postnatal jitteriness observed in laboratory animal infants prenatally exposed to antidepressants.

Measures of learning, the startle response, and hyperactivity have also been investigated in the context of prenatal NRI exposure. Only one study has examined prenatal NRI exposure in swim tests used to assess cognitive function on PND60 and PND125 but did not find any association between prenatal imipramine exposure and the cognitive outcomes in a Henderson-type maze (Coyle and Singer, 1975a). The acoustic startle response, which measures the startle reflex after a loud acoustic tone, has been shown to be mediated in part by the noradrenergic system (Olson et al., 2011). Prenatal NRI exposure has been shown to decrease the acoustic startle response in PND18 male rats (Ali et al., 1986) and adolescent (PND42–47) male rats (File and Tucker, 1984), although a dose-response relationship was not observed in either study. Haloperidol-induced catalepsy was unaltered by prenatal amitriptyline exposure in adolescent or adult males (Henderson and McMillen, 1993). Locomotion has been shown to be increased with prenatal NRI but not prenatal SRI exposure in male and female adolescent and adult rats (Cuomo et al., 1984) and adolescent male rats (Henderson and McMillen, 1990). However, when challenged with amphetamine, imipramine-exposed rats did not display any changes in locomotion compared with unexposed rats and completed negative geotaxis faster than control groups (Ali et al., 1986). Prenatal desipramine also did not produce any differences in quinpirole-induced stereotypy or locomotion (Stewart et al., 1998). Behavioral studies investigating prenatal NRI exposure are inconsistent, and although some groups have found behavioral differences, several endpoints have a null result or other studies conflict with positive associations with prenatal NRI exposure. Moreover, mechanistic explanations for many of the reported findings are lacking.

Studies investigating anxiety-like or depressive-like behavior have been performed in animals to elucidate any effects due to prenatal SRI exposure. Mice exposed prenatally to fluoxetine exhibited increases in anxiety-like behavior in adolescence and adulthood in the elevated plus maze, open-field test, and novelty suppressed feeding test (Noorlander et al., 2008). Others have reported increased immobility in the forced swim test for females in adolescence and adulthood (Lisboa et al., 2007). However, others report no differences in anxiety- or depressive-like behaviors (Coleman et al., 1999; Hsiao et al., 2005; Lisboa et al., 2007; Favaro et al., 2008). Ultrasonic vocalizations during separation or behavioral testing were increased in pups prenatally exposed to fluoxetine or paroxetine (Coleman et al., 1999; Cagiano et al., 2008). Prenatal exposure to the atypical antidepressant bupropion produced a decrease in rearing and ambulatory activity in the open-field test in adult male mice, although the doses used have not been commented upon as clinically relevant (Hsiao et al., 2005; Su et al., 2007). Alterations in locomotion may be a potential confound in behavioral tests, and false-positives in anxiety-like behavior, for example, may be attributed to altered locomotion. Studies have shown that prenatal fluoxetine exposure increases activity and improves motor coordination in the rotorod test (Bairy et al., 2007). A similar finding was reported with prenatal bupropion exposure (Su et al., 2007). In contrast, Coleman et al. (1999) and Stewart et al. (1998) observed no changes in baseline locomotion or quinpirole-induced stereotypy attributable to prenatal SSRI exposure.

Behavioral testing of learning and memory has been conducted in animals prenatally exposed to SSRIs. The Morris water maze and passive avoidance tests have been used to assess learning and memory in rodents. Prenatal exposure to fluoxetine resulted in an increase in learning in male and female adolescent rats (Bairy et al., 2007) but others have reported no differences due to prenatal SSRI exposure in the same tests (Grimm and Frieder, 1987; Christensen et al., 2000; Cagiano et al., 2008). Therefore, in these limited studies that do not attempt to use clinically relevant dosing, there does not seem to be a consistent role of prenatal SSRI exposure in the development of learning and memory skills.

Indices of social interaction have been investigated in animal studies of prenatal SSRI exposure. Prenatal fluoxetine exposure produced impaired sexual motivation in adult mice measured by no difference in preference for social contact with a male versus a female (Gouvêa et al., 2008). Aggressive behavior and foot shock-induced aggressive behavior have been shown to increase following prenatal SSRI exposure (Singh et al., 1998; Coleman et al., 1999). Several studies report no changes in social interaction or sexual behavior (Lisboa et al., 2007; Cagiano et al., 2008).

Several other indices of behavior have been investigated in the context of prenatal SSRI exposure. The acoustic startle response, a test of the fear-induced startle response (Koch, 1999), and prepulse inhibition, a test of sensorimotor gating, typically used to test animal models of schizophrenia and/or antipsychotic drug efficacy (Geyer et al., 2002), were examined by Vartazarmian et al. (2005) in guinea pigs prenatally exposed to fluoxetine. Prepulse inhibition was increased in both males and females after prenatal fluoxetine exposure, but the acoustic startle response was unchanged (Vartazarmian et al., 2005). Pain sensitivity has also been investigated after prenatal SSRI exposure, with one study showing an increase in pain threshold assessed by the hot plate test in adult guinea pigs after prenatal fluoxetine exposure via osmotic minipumps (7 mg/kg per day) (Vartazarmian et al., 2005); however, another study showed no changes in pain sensitivity in mice prenatally exposed to fluoxetine (7.5 mg/kg per day via oral gavage) (Lisboa et al., 2007). Forcelli and Heinrichs (2008) examined drug-seeking behavior after prenatal fluoxetine exposure using a steady exposure model via osmotic minipump implantation on G14 in the dam. Prenatal fluoxetine increased cocaine-induced place conditioning at PND60. Prenatal fluoxetine additionally increased the nose-poke response rate during the extinction phase of cocaine self-administration behavior on PND90, indicating an increase in the conditioned reinforcing effects of cocaine (Forcelli and Heinrichs, 2008). Others observed no changes in cocaine-induced place conditioning attributable to prenatal SSRI exposure (Hsiao et al., 2005). As described above, many behavioral studies examining the effects of prenatal SSRI exposure are often contradictory and a reproducible endpoint has not been identified as indicative of behavioral teratogenicity.

Concise ontogeneological data on human serotonergic function in the CNS is lacking, and definitive mapping of in utero exposure and postnatal exposures onto human fetal/infant serotonergic development is not possible at present (Avishai-Eliner et al., 2002). Importantly, the distribution of serotonergic neurons in rats is similar on G19 to adult groupings (Lidov and Molliver, 1982). Gingrich and colleagues investigated the use of serotonin reuptake inhibitors during postnatal development and find significant, long-term behavioral alterations in mice (Ansorge et al., 2004, 2008). Importantly, these studies employ a dosing regimen (i.e., daily administration) during the postnatal period (PND4–21) that may not adequately recapitulate human in utero exposure. To their credit, the dosing regimens used by Gingrich and colleagues postnatally lead to clinically relevant levels of SERT transporter occupancy, and drug exposure is maintained throughout their studies. However, the use of postnatal dosing may not be fully relevant to humans because, after birth, exposure in humans via lactation is low and infants are unlikely to receive any type of therapeutic dose of antidepressants for medical reasons for the first few years of life. Additionally, daily dosing does result in transient peaks that can be suprapharmacological, possibly toxic, and may be partially responsible for their observations.

III. Human Exposure Studies

Postmarketing surveillance and retrospective human studies examining the effects on the fetus and/or offspring of prenatal antidepressant exposure are the most common methods to assess possible adverse effects of perinatal exposure. Similarly, case reports and case series provide initial avenues for re-examination of existing data sets and future investigations. These data should contribute to delineation of potential mechanisms that can subsequently be tested in preclinical and clinical investigations with appropriate controls.

A. Defining the Clinical Problem

Pregnancy expands a woman's health considerations beyond herself to include her unborn child. In the case of a woman diagnosed with major depressive disorder, which has been reported to affect up to 10–20% of pregnant women (Gavin et al., 2005), the deleterious effects of untreated depression on the offspring can be profound and long lasting. Although the literature is replete with studies suggesting adverse effects, it is noteworthy that the definition of maternal depression has varied significantly across the investigations. Maternal depression and stress are often considered synonymous, making it difficult to delineate the impact, if any, of depressive symptoms from a clinical diagnosis of major depression. Depression during pregnancy has been associated with poor maternal health behaviors, including tobacco use, alcohol and drug use, and poor compliance with prenatal care (Zuckerman et al., 1989). Maternal depressive symptoms during pregnancy are associated with a higher risk of low birth weight and preterm delivery (Steer et al., 1992; Orr and Miller, 1995; Halbreich, 2005; Dunkel Schetter and Tanner, 2012). Behaviorally, neonates (8–72 hours postnatal) of depressed mothers are more inconsolable and cry excessively as assessed by the Neurologic and Adaptive Capacity Scale (Zuckerman et al., 1990). Children also exhibit increased internalizing behavior such as emotional reactivity, depression, anxiety, irritability, and withdrawal (Misri et al., 2006; Tronick and Reck, 2009). In a detailed prospective investigation conducted at 6 months postpartum, salivary cortisol reactivity was elevated in infants born to mothers with a history of major depression during pregnancy (Brennan et al., 2008; Field, 2011). Other groups have also demonstrated HPA axis abnormalities associated with maternal depression (Field, 2011). Additionally, mothers with a history of an affective disorder have a 2.5- to 5-fold increased risk of giving birth to a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Figueroa, 2010). Pregnant women who experienced a significant psychosocial stress exposure during pregnancy are reported to have an increased risk of giving birth to children later diagnosed with schizophrenia or shortened leukocyte telomere length (Khashan et al., 2008; Entringer et al., 2011). Stress during pregnancy has also been associated with an increased risk of developing an autism spectrum disorder in the offspring (Kinney et al., 2008). Human studies have shown that maternal depression, anxiety, and stress during pregnancy are associated with a greater risk of poor maternal health behaviors, obstetrical complications, offspring with HPA axis abnormalities, and neonatal and later behavioral aberrations. These data underscore the potential risks of untreated maternal symptoms during pregnancy, although the severity of symptoms warranting intervention remains obscure.

Preclinical studies typically use stress paradigms to model the potential impact of maternal depression during the perinatal period (see Newport et al., 2001 for review). Rodent studies utilizing prenatal stress exposures to the pregnant dam show disruption of stress responsivity in the offspring when examined at postnatal day 70 (Mueller and Bale, 2008). Chronic stress during pregnancy alters expression of key regulators and mediators of the stress pathway in the offspring, including decreased protein expression of the mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor in the hippocampus and prolonged increases in serum corticosterone concentrations in response to a stressor suggestive of impaired negative feedback (Maccari and Morley-Fletcher, 2007). Disruptions due to prenatal stress have been shown to persist via epigenetic miRNA mechanisms to offspring, and these may be passed on to subsequent generations (Darnaudery and Maccari, 2008; Dunn et al., 2011; Morgan and Bale, 2011).

Defining comparable stressor paradigms in preclinical models that appropriately reflect the clinical scenario of maternal depression is difficult at best. The key intersection might be summarized as “significant perinatal stress is associated with potentially quantifiable long lasting changes that may influence the developmental trajectory of the offspring.” Consistent with this area of concern is the American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) practice bulletin for psychotropic medications in pregnancy citing evidence that untreated maternal depression may pose significant risks (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2007; ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins–Obstetrics, 2008). Very recently, adult offspring (18 years of age) were at a significantly greater risk of having a diagnosis of depression if their mothers had depression during the pregnancy for that child (Pearson et al., 2013).

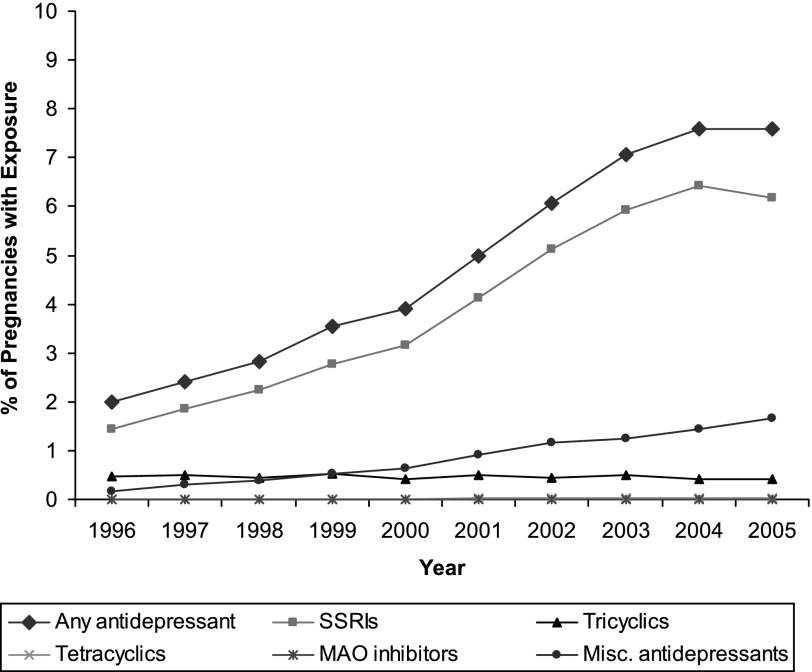

The use of antidepressants in the perinatal period appears to be increasing. For example, in the Netherlands, based on patient health records, 2% of all pregnant women were prescribed antidepressants (SSRIs or TCAs) during the 1st trimester of pregnancy (Ververs et al., 2006). In the United States of America, the number of women filling antidepressant prescriptions during pregnancy is as high as 8.7% (Cooper et al., 2007). The National Birth Defects Prevention Study in the United States has also observed that antidepressant use during pregnancy has increased 300% from 1998 to 2005 (Alwan et al., 2011). Given the increased use of antidepressants during pregnancy (Fig. 3), there is a great need for more rigorous studies that control for the potential confounds of other exposures and maternal symptoms to delineate potential adverse effects, if any, on the child. At present, a lack of clear, long-term consequences that coincide in preclinical and clinical studies should be acknowledged before a treatment decision is made and further argues for additional studies. Care providers need to be aware of the baseline percentage of untoward outcomes that naturally occur rather than attribute any untoward effects to prenatal medication exposure (Kaye and Weinstein, 2005).

Fig. 3.

Use of antidepressants during pregnancy: 1996–2005. The line with diamonds indicates any antidepressant use, the line with squares indicates SSRI use, the line with triangles indicates tricyclic antidepressant use, the line with crosses indicates tetracyclic antidepressant use, the line with asterisks indicates monoamine oxidase inhibitor use, and the line with circles indicates other miscellaneous antidepressant use. Less than 0.1% of pregnant women were exposed to tetracyclic antidepressants and MAO inhibitors. The pregnancy period is considered to be the period from 1 to 270 days before delivery, with three 90-day trimesters: first trimester incorporates the period from 181 to 270 days before delivery; second trimester incorporates the period from 91 to 180 days before delivery; third trimester incorporates the period from 1 to 90 days before delivery. Data for 2005 are not available for 1 of the 7 sites included in the analyses. Antidepressant use in the seven health plans for the period 1996–2000 were calculated using data from an earlier CERT study by Andrade et al. (2008) that evaluated medication use during pregnancy using similar methods (definitions and measures) as the present study. Adapted from Andrade et al. (2008).

Although increased usage during pregnancy is occurring, discontinuation of antidepressant treatment during pregnancy is also increasing, and antidepressant use decreases over each trimester (Ververs et al., 2006; Alwan et al., 2011). Although many medications may be used transiently, affective disorders belong to a class of complex diseases that typically are best controlled by continuous treatment (pharmacotherapy or proven psychotherapy techniques) (Kupfer et al., 2012). Pregnancy itself is a major determinant of antidepressant treatment discontinuation, and confirmation of pregnancy is associated with a 1.8- to 3.5-fold increase in antidepressant discontinuation, leading to a steady decline in antidepressant use over the course of pregnancy (Ramos et al., 2007; Bennett et al., 2010; Petersen et al., 2011).

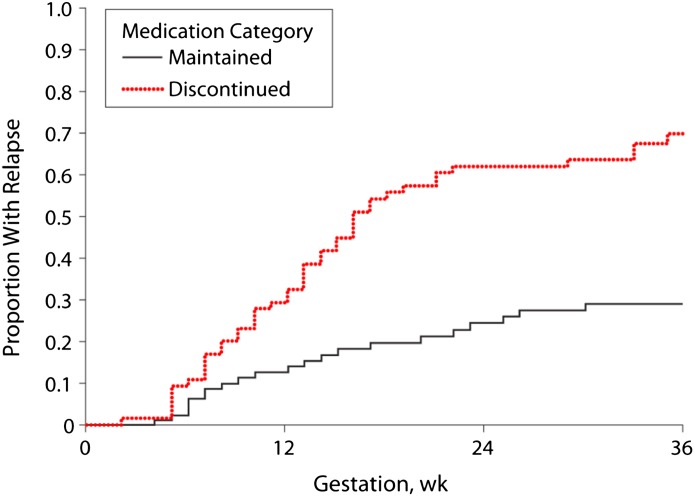

The efficacy of the newer antidepressant medications in the treatment of major depression in nonpregnant populations has undergone increasing scrutiny relative to the treatment effects compared with placebo over the past decade (Thase, 2008). This raises important issues with respect to the potential use of antidepressants during pregnancy: are they efficacious in the treatment of depression during pregnancy? There are no randomized clinical trials of antidepressants during pregnancy despite agreement that such trials are warranted and satisfy ethical critique (Coverdale et al., 2008; Howland, 2013). As such, the only insights into the expected benefits of antidepressant treatment, defined as a reduction in depressive symptoms, are obtained from the studies of depression recurrence across pregnancy. A high relapse rate was observed in a prospective study in women who discontinued antidepressants (Fig. 4) and suggests efficacy in reducing risk for recurrence (Cohen et al., 2006). However, this was not confirmed in a community-derived sample (Yonkers et al., 2011). Unfortunately, neither study commented on whether reintroduction of antidepressant medication ameliorated symptoms. It is noteworthy, that in the Cohen study, the recurrence rate in women continuing antidepressants during pregnancy exceeded 25% over a 40-week period. This recurrence rate is higher than typically reported in nonpregnant samples. This lack of sustained efficacy may be attributable to changes in plasma concentrations of antidepressants across pregnancy (Sit et al., 2008). It is also plausible that pregnancy represents a unique medical condition in which antidepressants are less effective over time as reported in patients with diabetes. In the absence of randomized clinical trials, the efficacy of antidepressants in the short-term treatment of depressive episodes during pregnancy is unknown, although there is evidence supporting a decreased risk for recurrence in clinical populations.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves illustrating the time to relapse after discontinuation of antidepressants during pregnancy. Adapted from Cohen et al. (2006).

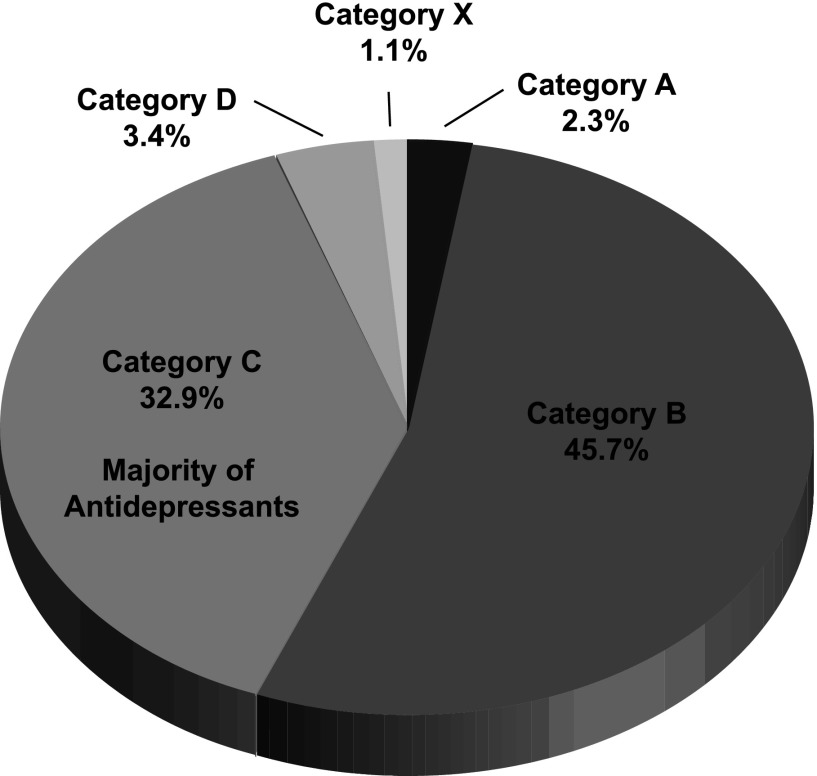

The limited studies and apparent contradictory results raise questions with respect to the historical premise that pregnancy protects the mother from the psychiatric disorders (Zajicek, 1981; Kendell et al., 1987). Proper counseling by providing balanced information is vital to making an informed decision about continuation and/or initiation of antidepressant treatment through pregnancy. The FDA safety classifications for pregnancy are shown in Table 1. The majority of antidepressants are currently category C; although there are animal studies indicating an adverse effect on the fetus, there are no adequate and well-controlled human studies, and the drug can be used during pregnancy only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus (Fig. 5). Paroxetine and the TCAs are rated category D; there are adequate and well-controlled human studies indicating a risk to the fetus, but the use of the drug in the pregnant woman may be acceptable despite the risk (Food and Drug Administration, 2011). Overall, the FDA recommends antidepressant use in pregnancy based on a risk-benefit decision on a case-by-case basis.

Fig. 5.

Percentage of pregnant women taking prescription drugs arranged by the Food and Drug Administration-labeling categories between 1996 and 2000 in the United States. Category A represents drugs that have well-controlled and adequate human and animal studies that show a low risk to the fetus. Category B drugs are classified as having animal studies that do not show a major risk to the fetus and the absence of well-controlled and adequate human studies. In Category C, a drug during pregnancy has an adverse effect in animal studies but there is an absence of well-controlled and adequate human studies. Category D drugs have a clear adverse effect in human and animal studies but the benefit to the pregnant woman may outweigh the risk. Category X drugs have a clear adverse effect in human and animal studies, and the benefit to the pregnant woman does not outweigh the risk to the fetus (Food and Drug Administration, 2011). Data adapted from (Andrade et al., 2004).

Investigators in the MotheRisk study in Toronto have commented on the absence of evidence-based information in the assessment of treatment decisions (Einarson, 2009). “Positive” studies that have an outcome or purported association of prenatal antidepressant exposure with some kind of malformation and/or adverse event are quickly reported by news outlets and disseminated to the lay public. Even more problematic in informing clinical decision making is the selective reporting of antidepressant effects and an apparent de-emphasis on the impact of maternal depression as was seen in the study by Oberlander and colleagues (2006). More recently, Domar and colleagues (2013) provided a selected review and noted the potential benefits of psychotherapy and exercise in nonpregnant groups as alternative treatment strategies. Although this article was quoted on several news media, they failed to note the >20% of women in their reproductive years do not have health insurance and that 48% of pregnancies in the United States are covered by Medicaid (Marcus et al., 2013). These are important considerations with respect to the availability and affordability of nonpharmacological treatment options. “Negative” studies that fail to identify any adverse effects garner far less media attention. This dichotomy in informing the lay public as well as bringing research data to the attention of clinicians contributes to the clinical conundrum and may lead to clinical decisions lacking evidence-based information (Einarson and Koren, 2007). Patients routinely overestimate the risk to the fetus when not presented with proper medical information (Einarson et al., 2005). The potential impact of reporting bias is illustrated in a study by Bonari and colleagues (2005) (see Table 4). For example, gastrointestinal medications, antibiotics, and antidepressants may have similar overall risks to the fetus, and in most cases, the antidepressant literature is more extensive. However, 87% of women believe that for antidepressants, the risk to the fetus is higher than the actual risk (Table 4) (Bonari et al., 2005).

TABLE 4.

Impact of MotheRisk counseling on perception of teratogenic risk

| Perception of Risk (Precounseling) * | Perception of Risk (Postcounseling) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| 87% of depressed women rated risk of antidepressants as greater than 1–3% | 12% of depressed women rated risk of antidepressants as greater than 1–3% | <0.001 |

| 56% of women with gastric problems rated risk of medications as greater than 1–3% | 4% of women with gastric problems rated risk of medications as greater than 1–3% | <0.001 |

| 22% of women with infections rated the risk of medications greater than 1–3% | 2% of women with infections rated the risk of medications greater than 1–3% | <0.001 |

Reproduced with permission from (Bonari et al., 2005).

Actual baseline rate for major malformations in the general population is 1–3%

B. Quantification of Fetal and Nursing Infant Antidepressant Exposure

The extent of fetal psychotropic drug exposure is governed by the pharmacokinetic properties of the maternal, placental, and fetal compartment. The primary routes of fetal exposure are through umbilical circulation and amniotic fluid. All psychotropics studied in vivo to date cross the placenta and are found in amniotic fluid (Hostetter et al., 2000; Loughhead et al., 2006a,b). Yet there are significant differences in placental passage rates. Bidirectional placental transfer is primarily mediated by simple diffusion, and the determinants of the transplacental diffusion rate include molecular weight, lipid solubility, degree of ionization, and plasma protein binding affinity (Moore et al., 1966; Pacifici and Nottoli, 1995; Audus, 1999). In addition, placental P-glycoprotein (multidrug resistance protein 1), which actively transports substrates from the fetal to the maternal circulation, is likely a partial determinant of fetal psychotropic exposure. Consequently, agents with greater affinity for P-glycoprotein may be associated with lower fetal-to-maternal medication ratios, as demonstrated in an investigation of antipsychotic placental passage (Newport et al., 2007). Further clarification of the factors governing placental passage may ultimately contribute to the development of psychotropic agents with minimal rates of placental transfer (Wang et al., 2007).

Ex vivo studies of isolated human placentas show that tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors pass across the placental barrier. Steady-state placental perfusion studies of amitriptyline, citalopram, or fluoxetine and their metabolites can reach up to 10% (Heikkinen et al., 2001, 2002b). In contrast, in vivo studies of umbilical cord medication distribution show much higher transfer of antidepressants as predicted for lipophilic substances.

Collection of paired maternal/umbilical cord blood at delivery as an index of placental passage has produced some interesting results. The TCAs nortriptyline, clomipramine, and their metabolites pass readily into umbilical cord serum in in vivo studies (Loughhead et al., 2006b). SSRI exposure results in higher umbilical cord transfer rates compared with TCAs. SSRI cord serum: maternal serum ratios are between 0.52 and 1.1 depending on the compound, illustrating significant placental transfer. Metabolites, which in some cases (e.g., norfluoxetine, desmethylvenlafaxine) are also active at inhibiting the serotonin transporter, readily transfer across the placental barrier (Rampono et al., 2004, 2009; Kim et al., 2006). Maternal/cord serum ratios have been rated as follows sertraline < paroxetine < fluoxetine < citalopram (Hendrick et al., 2003b). In a study of prenatal antidepressant exposure and pharmacogenetics, human infant drug concentrations were virtually undetectable and no relationship was associated with the drug-metabolizing enzymes CYP2D6 or CYP2C19 genotypes (Berle et al., 2004). Antidepressants are also present in human amniotic fluid (Loughhead et al., 2006a), providing additional routes of exposure.

Pregnancy can affect the metabolism and apparent clearance of medications. The clearance of several SSRIs has been shown to increase over the course of pregnancy (Sit et al., 2008), and our group demonstrated an increase in depressive scores for some women requiring dose adjustment during pregnancy (Hostetter et al., 2000). Similarly, postpartum, mothers taking citalopram, escitalopram, or sertraline have also been shown to be in a refractory metabolic state (Sit et al., 2008).

The majority of professional and lay organizations support breast milk as the "ideal" form of nutrition for the neonate through the first year of life. Studies of antidepressant exposure in breast milk are extensive relative to other classes of nonpsychotropic medications. Postpartum TCA exposure through breastfeeding results in a low exposure to the infant compared with in utero exposure. TCAs and their metabolites pass readily into breast milk, but because of the low absolute amounts (typically nanograms per milliliter range, with an estimated daily consumption of 100 ml/kg body weight), the nursing infant is exposed to a relatively small dose (Brixen-Rasmussen et al., 1982; Stancer and Reed, 1986; Wisner and Perel, 1991; Breyer-Pfaff et al., 1995; Yoshida et al., 1997). In many studies of TCAs, infant serum concentrations for drug or metabolite are undetectable at the level of analytic sensitivity used in those studies. Wisner et al. (1997) performed a controlled study of mother-infant breastfeeding pairs who had not received antidepressants during pregnancy. Nortriptyline and its metabolites were measured in the serum of six mother-infant pairs given nortriptyline 24 hours after birth for 4 weeks. Although nortriptyline and its hydroxylated metabolites were measured in maternal serum, infant serum concentrations were low or nondetectable (<4 ng/ml) compared with the typical clinical range of 50–150 ng/ml used in adults (Wisner et al., 1997).

SSRIs appear to transfer into breast milk at a much higher rate than TCAs, but exposure to the infant is still minimal. The first step in lactational exposure is transfer from the maternal serum to the breast milk. Breast milk has a natural gradient of fat content, with increasing fat content as one goes from fore to hind milk, and this can affect drug concentrations within the milk available at a feeding (Stowe et al., 1997, 2000, 2003). Additionally, breast milk concentrations change in direct relationship to maternal serum concentrations over the course of the day. The presence of both a temporal and fore to hind milk gradients for antidepressants should be kept in mind when examining the methodology of various research reports. Newport et al. (2009) examined the excretion of venlafaxine into breast milk. The infant/maternal plasma ratio was 0.062:1 for venlafaxine and 0.58:1 for the active metabolite desvenlafaxine, indicating significant exposure through lactation, although the effect was primarily driven by an extremely high ratio in a particular mother-infant pair from a cohort of five pairs. Otherwise, the ratios for desvenlafaxine in four other mother-infant pairs were 0.006, 0.009, 0.24, and 0.6:1 (Newport et al., 2009). Examination of other antidepressants has shown that the maternal serum and milk concentration ratio was paroxetine (0.7) < sertraline (1.8) < citalopram (2.1) < venlafaxine (2.4). Notably, the increasing milk: plasma ratios roughly correlate with the degree of protein binding for individual medications. Our previous work utilizing octanol partition coefficients as an index of lipophilicity of antidepressants (Capello et al., 2011) suggests that venlafaxine should have the lowest transfer into breast milk if driven primarily by lipophilicity.

Following transfer into breast milk, the question arises of whether the infant is exposed to an appreciable dose. Several antidepressants are detectable in human breast milk but are low or undetectable in infant serum (Altshuler et al., 1995; Epperson et al., 1997; Mammen et al., 1997; Stowe et al., 1997; Wisner et al., 1998; Heikkinen et al., 2002a; Briggs et al., 2009). A single study of potential functional consequences of nursing infant exposure estimated infant platelet serotonin uptake, measured by whole-blood serotonin concentrations, were shown to be unaffected in mother-infant breastfeeding pairs (Epperson et al., 2001). Weissman et al. (2004) conducted a large scale meta-analysis of 57 studies that examined mother-infant breastfeeding pairs to determine the amount of antidepressant exposure via lactational transfer. Overall, nortriptyline, sertraline, and paroxetine usually had undetectable concentrations in infant serum. Typically, fluoxetine, citalopram, and venlafaxine-exposed infants have detectable serum concentrations, but these concentrations are typically less than 10% of those clinically observed in the mother (Weissman et al., 2004). The extant literature indicates that fetal exposure in utero is substantially more pronounced than exposure via breast milk.