Abstract

The hyperglycemia of diabetes mellitus increases the filtered glucose load beyond the maximal tubular transport rate and thus leads to glucosuria. Sustained hyperglycemia, however, may gradually increase the maximal renal tubular transport rate and thereby blunt the increase of urinary glucose excretion. The mechanisms accounting for the increase of renal tubular glucose transport have remained ill-defined. A candidate is the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. The kinase has been shown to stimulate Na+-coupled glucose transport in vitro and mediate the stimulation of electrogenic intestinal glucose transport by glucocorticoids in vivo. SGK1 expression is confined to glomerula and distal nephron in intact kidneys but may extend to the proximal tubule in diabetic nephropathy. To explore whether SGK1 modifies glucose transport in diabetic kidneys, Akita mice (akita+/−), which develop spontaneous diabetes, have been crossbred with gene-targeted mice lacking SGK1 on one allele (sgk1+/−) to eventually generate either akita+/−/sgk1−/− or akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. Both akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice developed profound hyperglycemia (>20 mM) within ∼6 wk. Body weight and plasma glucose concentrations were not significantly different between these two genotypes. However, urinary excretion of glucose and urinary excretion of fluid, Na+, and K+, as well as plasma aldosterone concentrations, were significantly higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. Studies in isolated perfused proximal tubules revealed that the electrogenic glucose transport was significantly lower in akita+/−/sgk1−/− than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. The data provide the first evidence that SGK1 participates in the stimulation of renal tubular glucose transport in diabetic kidneys.

Keywords: serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1, diabetic nephropathy, glucose transport, sodium-glucose cotransporter, kidney

hyperglycemia increases the filtered load of glucose, which leads to glucosuria as soon as the maximal renal tubular transport rate is exceeded. Glucose transport in the diabetic kidney is upregulated (52) and thereby blunts the glucosuria. The upregulation of glucose transport is considered to result at least partially from enhanced apical expression of the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT1 (52). The signaling accounting for the upregulation of glucose transport has remained elusive.

Regulators of GLUT1 trafficking and activity include the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1 (59), which stimulates a variety of further nutrient transporters, including the glucose transporters SGLT1 (28) and GLUT4 (41); the amino acid transporters ASCT2 (SLC 1A5) (61), SN1 (13), EAAT1 (12), EAAT2 (14), EAAT3 (68), EAAT4 (16) and EAAT5 (15); the Na+-coupled dicarboxylate transporter NaDC (11); and the creatine transporter CreaT (71).

SGK1 transcription is stimulated by excessive glucose concentrations (66). Although SGK1 transcription is largely confined to the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron in normal kidneys (3, 53), its expression extends to other nephron segments in diabetic nephropathy (48).

The kinase was originally cloned as a glucocorticoid-sensitive gene (34) but later shown to be similarly regulated by mineralocorticoids (5, 19, 23, 29, 38, 42, 50, 53, 57, 70), gonadotropins (24, 36, 63, 64, 67), 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1), transforming growth factor-β (44, 83), interleukin-6 (54), fibroblast and platelet-derived growth factor (56), thrombin (4), and endothelin (85), as well as other cytokines (25, 47, 79). SGK1 transcription has further been shown to be stimulated by cell shrinkage (82), cell swelling (65), heat shock, UV radiation, and oxidative stress (51). SGK1 is activated by insulin (43) through a signaling cascade involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3 kinase) and 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) (6, 43, 62).

Beyond its effect on nutrient transporters, SGK1 is a potent regulator of renal electrolyte transporters, such as the epithelial Na+ channel ENaC (2, 17, 23, 26, 27, 32, 57, 73, 81, 84), the renal K+ channels ROMK (60, 87, 91) and KCNE1/KCNQ1 (22, 30), the epithelial Ca2+ channel TRPV5 (31, 58), the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 (89, 90), the Na+-K+-2Cl− cotransporter NKCC2, and the Na+-K+-ATPase (39, 69, 92). SGK1 contributes to the effect of aldosterone, IGF-1, and insulin on ENaC activity and thus renal salt reabsorption (7–10, 84). A gene variant of the SGK1 gene is associated with increased blood pressure (21, 22, 80) and obesity (28). Therefore, SGK1 has been suggested as a candidate for the development of metabolic syndrome (46).

The present study explored whether glucosuria in the diabetic kidney is affected by the presence of SGK1. To this end, Akita mice spontaneously developing early onset diabetes (20, 88) were crossed with gene-targeted mice lacking SGK1 on one allele (sgk1+/−). Comparison was made between akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice.

METHODS

All animal experiments were conducted according to the guidelines of the American Physiological Society as well as German law for the welfare of animals and were approved by local authorities.

Akita mice that spontaneously develop diabetes were crossed with heterozygous SGK1 knockout mice (sgk1+/−). Comparison was made between akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. Mice of similar age, sex, and background were used. Before the mice were included in the study, the diabetic phenotype was assured by determination of glucose levels. Glucose levels >200 mg/dl were considered as diabetic. The mice were fed a standard rodent diet (1314; Altromin, Heidenau, Germany) and allowed free access to tap drinking water.

For evaluation of renal excretion, mice were placed individually in metabolic cages (Techniplast, Hohenpeissenberg, Germany) for a 24-h urine collection (74). They were allowed a 3-day habituation period during which body weight, food intake, water intake, and urinary flow rate were recorded daily to ascertain that the mice had adapted to the new environment. Subsequently, a 24 h-collection of urine was performed for 2 consecutive days to obtain the basal urinary parameters. To ensure quantitative urine collection, the inner wall of the metabolic cages was siliconized and the urine was collected under water-saturated oil.

To obtain blood specimen, animals were lightly anesthetized with diethylether (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), and ∼200 μl of blood were withdrawn into heparinized capillaries by puncturing the retro-orbital plexus. Plasma and urinary concentrations of Na+ and K+ were measured by flame photometry (AFM 5051; Eppendorf, Germany). Plasma glucose concentrations were determined using a glucometer (Accutrend; Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Creatinine concentrations were measured in serum using an enzymatic colorimetric method (creatinine PAP; Lehmann, Berlin, Germany) and in urine using the Jaffe reaction (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Plasma aldosterone concentrations were determined using a commercial RIA kit (Demeditec, Kiel, Germany). Urinary glucose concentrations were similarly determined using a commercial enzymatic kit (gluco-quant; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

The potential difference across the basolateral cell membrane (ΔPDbl) in isolated perfused mid to late proximal tubules was determined with and without glucose in the perfusate to stimulate electrogenic absorption as previously described (75, 76). The bath and luminal perfusates were composed of (in mM) 110 NaCl, 5 KCl, 20 NaHCO3, 1.3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, and 2 Na2HPO4. In the bath, 1 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM Na-lactate, and 20 mM mannitol, and in the lumen, 25 mM mannitol, were added. Where indicated, 20 mM mannitol was replaced by 20 mM glucose in the luminal perfusate. PDbl was measured by a high-impedance electrometer (FD223; WPI Science Trading, Frankfurt, Germany) connected with the electrode via a Ag-AgCl half cell. The Ag-AgCl reference electrode was connected with the bath. Entry of positive charge by electrogenic transport is expected to depolarize the basolateral cell membrane. The magnitude of the depolarization depends on the magnitude of the induced current, on one hand, and on the resistances of cell membranes and shunt on the other.

In situ hybridization for SGK1 mRNA was performed on cryosections from adult murine kidneys as previously described (37). The hybridized digoxigenin-labeled RNA was detected by an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche) and visualized with nitroblue tetrazolium salt-5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate substrate solution (Roche).

For SGLT1 immunohistochemistry, hybridized sections were heat treated with citrate buffer (100 mM citric acid, pH 6.0). The following pretreatment, incubation, and washing steps were carried out as previously described (55). The primary SGLT1 antibody (rabbit anti-SGLT1, 1:800; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was incubated overnight at 4°C. After being washed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) buffer, the sections were incubated with the biotinylated secondary antibody (swine anti-rabbit IgG, 1:400; DAKO, Hamburg, Germany) for 30 min at room temperature. Detection of biotinylated antibody was accomplished with the avidin-biotin-peroxidase system (DAKO) and visualized with 3–3′diaminobenzidine substrate solution (DAB; Sigma, Munich, Germany) and hydrogen peroxide (Sigma). After additional washing steps, stained sections were coverslipped with Kaiser's glycerol gelatin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Data are means ± SE, and n represents the number of independent experiments. All data were tested for significance using a paired or unpaired Student t-test, and only results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

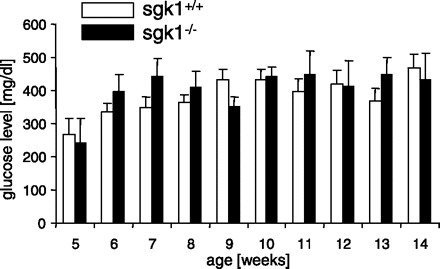

Cross breeding of Akita mice with gene-targeted mice lacking SGK1 on one allele (sgk1+/−) eventually led to the generation of heterozygous Akita mice lacking SGK1 (akita+/−/sgk1−/−) or expressing SGK1 (akita+/−/sgk1+/+). As shown in Fig. 1, both akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice developed profound hyperglycemia (>20 mM) within ∼6 wk. No significant difference was observed in plasma glucose concentrations between the genotypes.

Fig. 1.

Plasma glucose concentrations in akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. Values are means ± SE (for akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice/akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice, n = 3/5, 7/8, 9/11, 9/11, 7/11, 8/9, 6/11, 6/7, 9/9, and 7/10 for weeks 5–14, respectively) of plasma glucose concentrations in fed mice carrying the Akita mutation (akita+/−) and either lacking (sgk1−/−) or expressing (sgk1+/+) functional SGK1. Blood glucose concentrations were determined regularly between ages 5 and 14 wk.

Food intake was significantly higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. Accordingly, lack of SGK1 enhanced food intake in diabetic mice. Food intake was significantly lower in nondiabetic controls irrespective of the sgk1 genotype (Fig. 2A). Thus food intake was enhanced as a consequence of the induction of diabetes. Fluid intake tended to be higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. The fluid intake was significantly lower in nondiabetic controls (Fig. 2B). Accordingly, diabetes increased fluid intake in both genotypes. No differences were observed between the genotypes in body weight (Fig. 2C). Plasma aldosterone concentrations were significantly higher in sgk1−/− than in sgk1+/+ mice irrespective of the Akita genotype (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Food and fluid intake, body weight, and plasma aldosterone concentrations in diabetic akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice and in nondiabetic akita+/+/sgk1−/− and akita+/+/sgk1+/+ mice. Values are means ± SE (n = 7–10 for each group) of food intake (A), fluid intake (B), body weight (C), and plasma aldosterone concentrations (D) in mice carrying the Akita mutation (akita+/−) and either lacking (sgk1−/−) or expressing (sgk1+/+) functional SGK1, as well as in nondiabetic mice (akita+/+) either lacking or expressing functional SGK1. *P < 0.05 vs. respective value of akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. ###P < 0.001 vs. respective value of akita+/− mice.

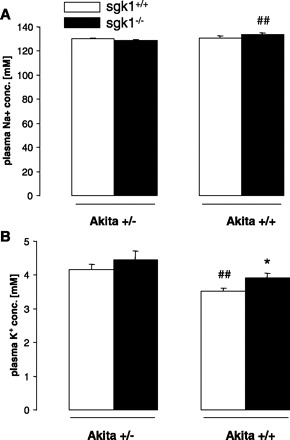

No significant differences were observed in plasma Na+ and K+ concentrations between akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. However, akita+/+/sgk1−/− mice had significantly higher plasma Na+ concentrations than akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice (Fig. 3A), and akita+/+/sgk1+/+ mice had significantly lower plasma K+ concentration than akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice (Fig. 3B). Among nondiabetic controls, sgk1−/− mice had significantly higher plasma K+ concentration than sgk1+/+ mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Plasma Na+ and K+ concentrations in diabetic akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice and in nondiabetic akita+/+/sgk1−/− and akita+/+/sgk1+/+ mice. Values are means ± SE (n = 6–8 for each group) of plasma Na+ (A) and K+ concentrations (B) in mice carrying the Akita mutation (akita+/−) and either lacking (sgk1−/−) or expressing (sgk1+/+) functional SGK1. Nondiabetic mice (akita+/+) served as controls. *P < 0.05 vs. respective value of akita+/+/sgk1+/+ mice. ##P < 0.01 vs. respective value of akita+/− mice.

Creatinine clearance tended to be higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. However, the difference did not reach statistical significance. Nondiabetic controls showed a significantly lower creatinine clearance irrespective of the sgk1 genotype (Fig. 4A). Urinary flow rate was significantly higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. Nondiabetic controls excreted significantly lower urine volume irrespective of the sgk1 genotype. Thus diabetic mice had higher urinary volumes than nondiabetic mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Urinary flow rate, creatinine clearance, and urinary excretion of Na+ and K+ in diabetic akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice and in nondiabetic akita+/+/sgk1−/− and akita+/+/sgk1+/+ mice. Value are means ± SE (n = 5–8 for each group) of urinary flow rate (A), creatinine clearance (B), and urinary excretion of Na+ (C) and K+ (D) in mice carrying the Akita mutation (akita+/−) and either lacking (sgk1−/−) or expressing (sgk1+/+) functional SGK1. Nondiabetic mice (akita+/+) served as controls. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01 vs. respective value of akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. #P < 0.05; ###P < 0.001 vs. respective value of akita+/− mice.

Urinary excretions of both Na+ and K+ were significantly higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. In nondiabetic controls lacking sgk1, the Na+ excretion was significantly lower than in diabetic mice lacking sgk1. Furthermore, non-diabetic controls had a lower K+ excretion compared with diabetic mice irrespective of the sgk1 genotype (Fig. 4, C and D).

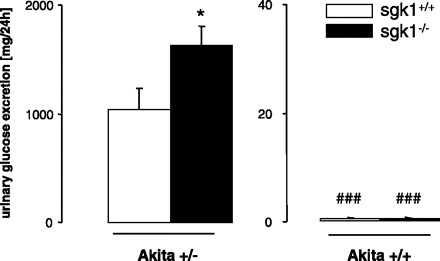

As shown in Fig. 5, urinary glucose excretion was significantly higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. Nondiabetic mice did not excrete appreciable amounts of glucose irrespective of the sgk1 genotype.

Fig. 5.

Urinary glucose excretion in diabetic akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice and in nondiabetic akita+/+/sgk1−/− and akita+/+/sgk1+/+ mice. Values are means ± SE (n = 6–8 for each group) of urinary glucose excretion in mice carrying the Akita mutation (akita+/−) and either lacking (sgk1−/−; average age = 5.54 mo) or expressing (sgk1+/+; average age = 4.26 mo) functional SGK1. Nondiabetic mice (akita+/+; average age 2.83 mo) served as controls. *P < 0.05 vs. respective value of akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. ###P < 0.001 vs. respective value of akita+/− mice.

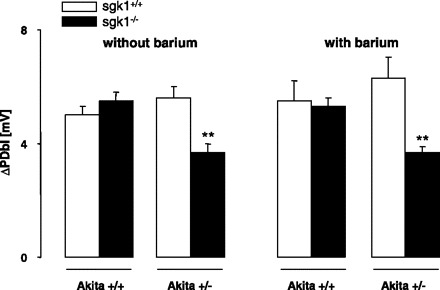

Isolated tubules were perfused to determine whether the enhanced renal glucose excretion in akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice was the result of decreased electrogenic proximal renal tubular glucose transport. The basolateral cell membrane potential tended to be higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice (−64.6 ± 2.9 mV, n = 7) than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice (−62.1 ± 2.1 mV, n = 6). Luminal application of K+ channel blocker barium (2 mM) depolarized the basolateral cell membrane potential in both akita+/−/sgk1−/− (to −58.1 ± 2.0 mV, n = 6) and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice (to −45.8 ± 5.8 mV, n = 5). The effect was significantly blunted in akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice, and thus the basolateral cell membrane potential in the presence of luminal barium was significantly higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. Application of 20 mM glucose to the luminal perfusate depolarized the basolateral cell membrane, an effect significantly blunted in akita+/−/sgk1−/− compared with akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice (Fig. 6). In nondiabetic controls, no difference was observed between sgk1−/− and sgk1+/+ mice. The responses to glucose in both the absence and presence of barium provided evidence that the electrogenic glucose uptake in the luminal membrane of proximal tubules is blunted in akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice.

Fig. 6.

Glucose-induced depolarization of the basolateral cell membrane in diabetic akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice and in nondiabetic akita+/+/sgk1−/− and akita+/+/sgk1+/+ mice. Values are means ± SE (n = 5–8 for each group) of the depolarization of the basolateral cell membrane (ΔPDbl) by addition of 20 mM glucose (replacing 20 mM mannitol) in isolated perfused proximal tubules from mice carrying the Akita mutation (akita+/−) and either lacking (sgk1−/−) or expressing (sgk1+/+ mice) functional SGK1. Nondiabetic mice (akita+/+) served as controls. **P < 0.01 vs. respective value of akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice.

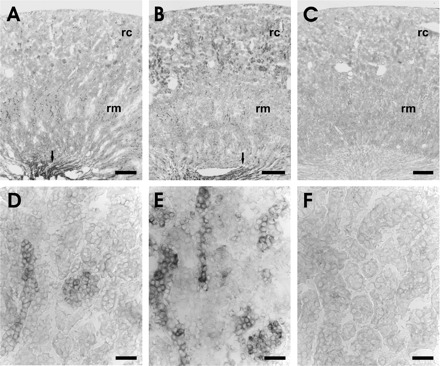

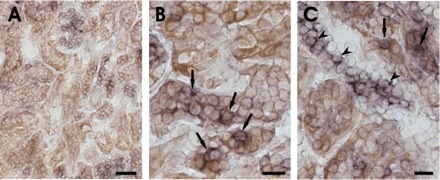

In situ hybridization of SGK1 mRNA abundance in kidneys from normal mice disclosed very low SGK1 transcript levels in the renal cortex but high transcript levels in collecting duct (Fig. 7). In the renal cortex of diabetic mice, SGK1 transcript levels were enhanced, pointing to upregulation of SGK1 transcription in hyperglycemia. As shown in Fig. 8, in some but not all cells, SGK1 colocalizes with SGLT1.

Fig. 7.

In situ hybridization for SGK1 mRNA on kidney sections of normal and diabetic mice. A and B: overview of SGK1 mRNA expression in the kidney of normal (A) and diabetic mice (B). Arrows point to the strong signals in the collecting duct epithelium of the renal papilla. C: overview of diabetic kidney section hybridized with the sense probe. D and E: higher magnification of the renal cortex of normal (D) and diabetic mice (E). F: higher magnification of the renal cortex of diabetic kidney section hybridized with the sense probe. rc, Renal cortex; rm, renal medulla. Scale bars: A–C, 500 μm; D–F, 20 μm.

Fig. 8.

Combined in situ hybridization for SGK1 mRNA and SGLT1 immunohistochemistry on kidney sections of diabetic mice. A: overview of SGK1 mRNA (violet) and SGLT1 expression (brown) in the renal cortex of diabetic mice. B and C: higher magnification of the renal cortex. Arrows point to double-labeled tubular cells coexpressing SGK1 mRNA (violet) and SGLT1 (brown). Arrowheads indicate SGK-1 mRNA-expressing cells that are negative for SGLT1. Scale bars: A, 50 μm; B and C, 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

The present study reveals a novel pathophysiological role of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. According to our observations, the kinase stimulates proximal tubular reabsorption of glucose in diabetic animals. Diabetes has been induced by crossing with Akita (akita+/−) mice. The akita+/− mice spontaneously develop diabetes due to death of pancreatic β-cells.

As shown earlier (48), excessive extracellular glucose concentrations stimulate the transcription of SGK1. Accordingly, the SGK1 transcript levels were enhanced in the renal cortex of hyperglycemic mice (Fig. 7). As a result of hyperglycemia, the filtered load exceeds the maximal tubular transport rate of glucose and thereby leads to glucosuria. The glucose-induced depolarization of the basolateral cell membrane of mid to late proximal tubules, which reflects the electrogenic transport of glucose (49), is in diabetic akita+/− mice apparently dependent on the presence of SGK1. Genetic knockout of SGK1 decreases the depolarization by almost 50%, an observation pointing to decreased SGLT1 activity. Accordingly, the glucosuria is significantly enhanced in SGK1-deficient akita+/− mice, even though plasma glucose concentration was not significantly different.

The enhanced renal loss of glucose in hyperglycemic mice lacking SGK1 (akita+/−/sgk1−/−) did not result in a significant decrease of plasma glucose levels. Presumably, extrarenal mechanisms compensated for the enhanced renal loss of glucose, such as enhanced levels of hormones increasing plasma glucose concentrations.

Both in vitro (28, 59, 72) and in vivo (18, 37, 59) data demonstrate the ability of SGK1 to stimulate glucose transporters. In addition, SGK1 can activate the potassium channel KCNE1/KCNQ1 (30), which is expressed in the apical membrane of the proximal tubule and serves to repolarize the cell membrane during electrogenic glucose reabsorption (75, 76). Addition of barium to the luminal perfusate abrogates electrogenic K+ exit across the apical cell membrane, an effect expected to increase the glucose induced depolarization. By the same token, barium depolarizes the apical cell membrane, thus decreasing electrogenic glucose transport. Apparently, in the present experiments the opposing effects largely cancelled each other, and thus barium had little influence on the glucose-induced depolarization. In earlier experiments utilizing lower luminal glucose concentrations, apical barium or genetic knockout of KCNQ1 enhanced the depolarizing effect of glucose (75, 76). In any case, according to the present study, the differences in electrogenic proximal tubular glucose transport between akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice are not abrogated by luminal application of the K+ channel blocker barium. This observation does not rule out a participation of KCNE1/KCNQ1 in the SGK1-sensitive regulation of SGLT1 activity but clarifies that altered activity of those channels does not fully account for the differences between akita+/−/sgk1−/− and akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice.

Electrogenic glucose transport in intestine was not significantly different between SGK1 knockout mice (sgk1−/−) and their wild-type littermates (sgk1+/+) under basal conditions but was significantly stimulated by the glucocorticoid dexamethasone only in sgk1+/+ mice, not in sgk1−/− mice (37).

Glucose transport in renal proximal tubules was not considered to be regulated by SGK1, since in healthy humans and intact animals SGK1 is expressed in the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron rather than in the proximal tubule (35, 46, 53, 78). In the absence of hyperglycemia, SGK1 deficiency leads to impaired Na+ reabsorption in the aldosterone sensitive nephron segments with a compensatory increase in proximal tubular Na+ reabsorption (86). Hyperglycemia, however, markedly upregulates SGK1 expression (33, 44). Accordingly, excessive SGK1 expression has been observed throughout the kidney in diabetic nephropathy (44, 48). In isolated perfused proximal tubules, the glucose-induced current tended to be higher in diabetic akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice than in nondiabetic akita+/+/sgk1+/+ mice, a difference, however, that did not reach statistical significance. Thus electrogenic glucose transport may not be increased in diabetic animals. In any case, in diabetic, but not nondiabetic animals, electrogenic glucose transport is partially dependent on the presence of SGK1.

Impaired upregulation of proximal tubular glucose reabsorption augments glucosuria. The nonreabsorbed glucose leads to osmotic diuresis and thus increases urinary output and renal excretion of Na+ and K+ (45). Accordingly, urinary flow rate and urinary excretions of Na+ and K+ were increased to significantly greater extent in akita+/−/sgk1−/− mice than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. The renal loss of Na+ is expected to cause volume depletion, which should stimulate Na+ intake and aldosterone release. Plasma aldosterone levels are indeed significantly higher in akita+/−/sgk1−/− than in akita+/−/sgk1+/+ mice. Even in nondiabetic conditions, plasma aldosterone concentrations are enhanced in sgk1−/− mice, which is a result of impaired SGK1-dependent stimulation of renal tubular Na+ reabsorption (86). Moreover, lack of SGK1 compromises the ability to excrete potassium loads (40) and to enhance salt appetite in response to mineralocorticoid excess (77). Plasma aldosterone concentrations are thus increased in sgk1−/− mice even under control conditions and partially compensate for the lack of SGK1.

In conclusion, the present observations disclose that SGK1 contributes to the upregulation of renal tubular glucose reabsorption in the diabetic kidney.

GRANTS

This study was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants GRK 1302, DFG GRK 880, and DFG Ha 1755/8-1, National Institutes of Health Grant DK-5628, and National Natural Science Foundation of China NSFC Grant 30270618.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical assistance of E. Faber and meticulous preparation of the manuscript by T. Loch and L. Subasic.

Footnotes

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akutsu N, Lin R, Bastien Y, Bestawros A, Enepekides DJ, Black MJ, White JH. Regulation of gene expression by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Its analog EB1089 under growth-inhibitory conditions in squamous carcinoma Cells. Mol Endocrinol 15: 1127–1139, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez de la Rosa D, Zhang P, Naray-Fejes-Toth A, Fejes-Toth G, Canessa CM. The serum and glucocorticoid kinase sgk increases the abundance of epithelial sodium channels in the plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes. J Biol Chem 274: 37834–37839, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez de la Rosa D, Canessa CM. Role of SGK in hormonal regulation of epithelial sodium channel in A6 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C404–C414, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belaiba RS, Djordjevic T, Bonello S, Artunc F, Lang F, Hess J, Gorlach A. The serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase Sgk-1 is involved in pulmonary vascular remodeling: role in redox-sensitive regulation of tissue factor by thrombin. Circ Res 98: 828–836, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhargava A, Fullerton MJ, Myles K, Purdy TM, Funder JW, Pearce D, Cole TJ. The serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase is a physiological mediator of aldosterone action. Endocrinology 142: 1587–1594, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biondi RM, Kieloch A, Currie RA, Deak M, Alessi DR. The PIF-binding pocket in PDK1 is essential for activation of S6K and SGK, but not PKB. EMBO J 20: 4380–4390, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blazer-Yost BL, Esterman MA, Vlahos CJ. Insulin-stimulated trafficking of ENaC in renal cells requires PI 3-kinase activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 284: C1645–C1653, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blazer-Yost BL, Liu X, Helman SI. Hormonal regulation of ENaCs: insulin and aldosterone. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C1373–C1379, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blazer-Yost BL, Paunescu TG, Helman SI, Lee KD, Vlahos CJ. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase is required for aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 277: C531–C536, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blazer-Yost BL, Vahle JC, Byars JM, Bacallao RL. Real-time three-dimensional imaging of lipid signal transduction: apical membrane insertion of epithelial Na+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C1569–C1576, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boehmer C, Embark HM, Bauer A, Palmada M, Yun CH, Weinman EJ, Endou H, Cohen P, Lahme S, Bichler KH, Lang F. Stimulation of renal Na+ dicarboxylate cotransporter 1 by Na+/H+ exchanger regulating factor 2, serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase isoforms, and protein kinase B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 313: 998–1003, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehmer C, Henke G, Schniepp R, Palmada M, Rothstein JD, Broer S, Lang F. Regulation of the glutamate transporter EAAT1 by the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2 and the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoforms SGK1/3 and protein kinase B. J Neurochem 86: 1181–1188, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boehmer C, Okur F, Setiawan I, Broer S, Lang F. Properties and regulation of glutamine transporter SN1 by protein kinases SGK and PKB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 306: 156–162, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boehmer C, Palmada M, Rajamanickam J, Schniepp R, Amara S, Lang F. Post-translational regulation of EAAT2 function by co-expressed ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2 is impacted by SGK kinases. J Neurochem 97: 911–921, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boehmer C, Rajamanickam J, Schniepp R, Kohler K, Wulff P, Kuhl D, Palmada M, Lang F. Regulation of the excitatory amino acid transporter EAAT5 by the serum and glucocorticoid dependent kinases SGK1 and SGK3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 329: 738–742, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bohmer C, Philippin M, Rajamanickam J, Mack A, Broer S, Palmada M, Lang F. Stimulation of the EAAT4 glutamate transporter by SGK protein kinase isoforms and PKB. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 324: 1242–1248, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Böhmer C, Wagner CA, Beck S, Moschen I, Melzig J, Werner A, Lin JT, Lang F, Wehner F. The shrinkage-activated Na+ conductance of rat hepatocytes and its possible correlation to rENaC. Cell Physiol Biochem 10: 187–194, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boini KM, Hennige AM, Huang DY, Friedrich B, Palmada M, Boehmer C, Grahammer F, Artunc F, Ullrich S, Avram D, Osswald H, Wulff P, Kuhl D, Vallon V, Haring HU, Lang F. Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 mediates salt sensitivity of glucose tolerance. Diabetes 55: 2059–2066, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brennan FE, Fuller PJ. Rapid upregulation of serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase (sgk) gene expression by corticosteroids in vivo. Mol Cell Endocrinol 166: 129–136, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breyer MD, Qi Z, Tchekneva E. Diabetic nephropathy: leveraging mouse genetics. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 15: 227–232, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busjahn A, Luft FC. Twin studies in the analysis of minor physiological differences between individuals. Cell Physiol Biochem 13: 51–58, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Busjahn A, Seebohm G, Maier G, Toliat MR, Nurnberg P, Aydin A, Luft FC, Lang F. Association of the serum and glucocorticoid regulated kinase (sgk1) gene with QT interval. Cell Physiol Biochem 14: 135–142, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen SY, Bhargava A, Mastroberardino L, Meijer OC, Wang J, Buse P, Firestone GL, Verrey F, Pearce D. Epithelial sodium channel regulated by aldosterone-induced protein sgk. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 2514–2519, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu S, Rushdi S, Zumpe ET, Mamers P, Healy DL, Jobling T, Burger HG, Fuller PJ. FSH-regulated gene expression profiles in ovarian tumours and normal ovaries. Mol Hum Reprod 8: 426–433, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowling RT, Birnboim HC. Expression of serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase (sgk) mRNA is up-regulated by GM-CSF and other proinflammatory mediators in human granulocytes. J Leukoc Biol 67: 240–248, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Debonneville C, Flores SY, Kamynina E, Plant PJ, Tauxe C, Thomas MA, Munster C, Chraibi A, Pratt JH, Horisberger JD, Pearce D, Loffing J, Staub O. Phosphorylation of Nedd4-2 by Sgk1 regulates epithelial Na+ channel cell surface expression. EMBO J 20: 7052–7059, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diakov A, Korbmacher C. A novel pathway of epithelial sodium channel activation involves a serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase consensus motif in the C terminus of the channel's α-subunit. J Biol Chem 279: 38134–38142, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dieter M, Palmada M, Rajamanickam J, Aydin A, Busjahn A, Boehmer C, Luft FC, Lang F. Regulation of glucose transporter SGLT1 by ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2 and kinases SGK1, SGK3, and PKB. Obes Res 12: 862–870, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Driver PM, Rauz S, Walker EA, Hewison M, Kilby MD, Stewart PM. Characterization of human trophoblast as a mineralocorticoid target tissue. Mol Hum Reprod 9: 793–798, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Embark HM, Bohmer C, Vallon V, Luft F, Lang F. Regulation of KCNE1-dependent K+ current by the serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK) isoforms. Pflügers Arch 445: 601–606, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Embark HM, Setiawan I, Poppendieck S, van de Graaf SF, Boehmer C, Palmada M, Wieder T, Gerstberger R, Cohen P, Yun CC, Bindels RJ, Lang F. Regulation of the epithelial Ca2+ channel TRPV5 by the NHE regulating factor NHERF2 and the serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase isoforms SGK1 and SGK3 expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem 14: 203–212, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faletti CJ, Perrotti N, Taylor SI, Blazer-Yost BL. sgk: an essential convergence point for peptide and steroid hormone regulation of ENaC-mediated Na+ transport. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 282: C494–C500, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng Y, Wang Q, Wang Y, Yard B, Lang F. SGK1-mediated fibronectin formation in diabetic nephropathy. Cell Physiol Biochem 16: 237–244, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Firestone GL, Giampaolo JR, O'Keeffe BA. Stimulus-dependent regulation of the serum and glucocorticoid inducible protein kinase (Sgk) transcription, subcellular localization and enzymatic activity. Cell Physiol Biochem 13: 1–12, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores SY, Loffing-Cueni D, Kamynina E, Daidie D, Gerbex C, Chabanel S, Dudler J, Loffing J, Staub O. Aldosterone-induced serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 expression is accompanied by Nedd4-2 phosphorylation and increased Na+ transport in cortical collecting duct cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2279–2287, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonzalez-Robayna IJ, Falender AE, Ochsner S, Firestone GL, Richards JS. Follicle-Stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates phosphorylation and activation of protein kinase B (PKB/Akt) and serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase (Sgk): evidence for A kinase-independent signaling by FSH in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 14: 1283–1300, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grahammer F, Henke G, Sandu C, Rexhepaj R, Hussain A, Friedrich B, Risler T, Metzger M, Just L, Skutella T, Wulff P, Kuhl D, Lang F. Intestinal function of gene-targeted mice lacking serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G1114–G1123, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gumz ML, Popp MP, Wingo CS, Cain BD. Early transcriptional effects of aldosterone in a mouse inner medullary collecting duct cell line. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F664–F673, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henke G, Setiawan I, Bohmer C, Lang F. Activation of Na+/K+-ATPase by the serum and glucocorticoid-dependent kinase isoforms. Kidney Blood Press Res 25: 370–374, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang DY, Wulff P, Volkl H, Loffing J, Richter K, Kuhl D, Lang F, Vallon V. Impaired regulation of renal K+ elimination in the sgk1-knockout mouse. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 885–891, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeyaraj S, Boehmer C, Lang F, Palmada M. Role of SGK1 kinase in regulating glucose transport via glucose transporter GLUT4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 356: 629–635, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kellner M, Peiter A, Hafner M, Feuring M, Christ M, Wehling M, Falkenstein E, Losel R. Early aldosterone up-regulated genes: new pathways for renal disease? Kidney Int 64: 1199–1207, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobayashi T, Cohen P. Activation of serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated protein kinase by agonists that activate phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase is mediated by 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 (PDK1) and PDK2. Biochem J 339: 319–328, 1999 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar JM, Brooks DP, Olson BA, Laping NJ. Sgk, a putative serine/threonine kinase, is differentially expressed in the kidney of diabetic mice and humans. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2488–2494, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lang F. Osmotic diuresis. Ren Physiol 10: 160–173, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lang F, Bohmer C, Palmada M, Seebohm G, Strutz-Seebohm N, Vallon V. (Patho)physiological significance of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase isoforms. Physiol Rev 86: 1151–1178, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lang F, Cohen P. Regulation and physiological roles of serum- and glucocorticoid-induced protein kinase isoforms. Sci STKE 2001: RE17, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lang F, Klingel K, Wagner CA, Stegen C, Warntges S, Friedrich B, Lanzendorfer M, Melzig J, Moschen I, Steuer S, Waldegger S, Sauter M, Paulmichl M, Gerke V, Risler T, Gamba G, Capasso G, Kandolf R, Hebert SC, Massry SG, Broer S. Deranged transcriptional regulation of cell-volume-sensitive kinase hSGK in diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 8157–8162, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lang F, Messner G, Rehwald W. Electrophysiology of sodium-coupled transport in proximal renal tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 250: F953–F962, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Menuet D, Isnard R, Bichara M, Viengchareun S, Muffat-Joly M, Walker F, Zennaro MC, Lombes M. Alteration of cardiac and renal functions in transgenic mice overexpressing human mineralocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem 276: 38911–38920, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leong ML, Maiyar AC, Kim B, O'Keeffe BA, Firestone GL. Expression of the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible protein kinase, Sgk, is a cell survival response to multiple types of environmental stress stimuli in mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 278: 5871–5882, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Linden KC, DeHaan CL, Zhang Y, Glowacka S, Cox AJ, Kelly DJ, Rogers S. Renal expression and localization of the facilitative glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT12 in animal models of hypertension and diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F205–F213, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loffing J, Zecevic M, Feraille E, Kaissling B, Asher C, Rossier BC, Firestone GL, Pearce D, Verrey F. Aldosterone induces rapid apical translocation of ENaC in early portion of renal collecting system: possible role of SGK. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F675–F682, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meng F, Yamagiwa Y, Taffetani S, Han J, Patel T. IL-6 activates serum and glucocorticoid kinase via p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289: C971–C981, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Metzger M, Conrad S, Skutella T, Just L. RGMa inhibits neurite outgrowth of neuronal progenitors from murine enteric nervous system via the neogenin receptor in vitro. J Neurochem 103: 2665–2678, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mizuno H, Nishida E. The ERK MAP kinase pathway mediates induction of SGK (serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase) by growth factors. Genes Cells 6: 261–268, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Naray-Fejes-Toth A, Canessa C, Cleaveland ES, Aldrich G, Fejes-Toth G. sgk is an aldosterone-induced kinase in the renal collecting duct: effects on epithelial Na+ channels. J Biol Chem 274: 16973–16978, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Palmada M, Poppendieck S, Embark HM, van de Graaf SFJ, Boehmer C, Bindels RJM, Lang F. Requirement of PDZ domains for the stimulation of the epithelial Ca2+ channel TRPV5 by the NHE regulating factor NHERF2 and the serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase SGK1. Cell Physiol Biochem 15: 175–182, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palmada M, Boehmer C, Akel A, Rajamanickam J, Jeyaraj S, Keller K, Lang F. SGK1 kinase upregulates GLUT1 activity and plasma membrane expression. Diabetes 55: 421–427, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Palmada M, Embark HM, Yun C, Böhmer C, Lang F. Molecular requirements for the regulation of the renal outer medullary K+ channel ROMK1 by the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 311: 629–634, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Palmada M, Speil A, Jeyaraj S, Bohmer C, Lang F. The serine/threonine kinases SGK1, 3 and PKB stimulate the amino acid transporter ASCT2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 331: 272–277, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Park J, Leong ML, Buse P, Maiyar AC, Firestone GL, Hemmings BA. Serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase (SGK) is a target of the PI 3-kinase-stimulated signaling pathway. EMBO J 18: 3024–3033, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richards JS. New signaling pathways for hormones and cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate action in endocrine cells. Mol Endocrinol 15: 209–218, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richards JS, Fitzpatrick SL, Clemens JW, Morris JK, Alliston T, Sirois J. Ovarian cell differentiation: a cascade of multiple hormones, cellular signals, and regulated genes. Recent Prog Horm Res 50: 223–254, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rozansky DJ, Wang J, Doan N, Purdy T, Faulk T, Bhargava A, Dawson K, Pearce D. Hypotonic induction of SGK1 and Na+ transport in A6 cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F105–F113, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saad S, Stevens VA, Wassef L, Poronnik P, Kelly DJ, Gilbert RE, Pollock CA. High glucose transactivates the EGF receptor and up-regulates serum glucocorticoid kinase in the proximal tubule. Kidney Int 68: 985–997, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Salvador LM, Park Y, Cottom J, Maizels ET, Jones JC, Schillace RV, Carr DW, Cheung P, Allis CD, Jameson JL, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Follicle-stimulating hormone stimulates protein kinase A-mediated histone H3 phosphorylation and acetylation leading to select gene activation in ovarian granulosa cells. J Biol Chem 276: 40146–40155, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schniepp R, Kohler K, Ladewig T, Guenther E, Henke G, Palmada M, Boehmer C, Rothstein JD, Broer S, Lang F. Retinal colocalization and in vitro interaction of the glutamate transporter EAAT3 and the serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45: 1442–1449, 2004. [Erratum. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 45 (Aug): 2474, 2004.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Setiawan I, Henke G, Feng Y, Bohmer C, Vasilets LA, Schwarz W, Lang F. Stimulation of Xenopus oocyte Na+,K+ATPase by the serum and glucocorticoid-dependent kinase sgk1. Pflügers Arch 444: 426–431, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shigaev A, Asher C, Latter H, Garty H, Reuveny E. Regulation of sgk by aldosterone and its effects on the epithelial Na+ channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F613–F619, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shojaiefard M, Christie DL, Lang F. Stimulation of the creatine transporter SLC6A8 by the protein kinases SGK1 and SGK3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 334: 742–746, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shojaiefard M, Strutz-Seebohm N, Tavare JM, Seebohm G, Lang F. Regulation of the Na+, glucose cotransporter by PIKfyve and the serum and glucocorticoid inducible kinase SGK1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 359: 843–847, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Snyder PM, Olson DR, Thomas BC. Serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase modulates Nedd4-2-mediated inhibition of the epithelial Na+ channel. J Biol Chem 277: 5–8, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vallon V. In vivo studies of the genetically modified mouse kidney. Nephron Physiol 94: 1–5, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vallon V, Grahammer F, Richter K, Bleich M, Lang F, Barhanin J, Volkl H, Warth R. Role of KCNE1-dependent K+ fluxes in mouse proximal tubule. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 2003–2011, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vallon V, Grahammer F, Volkl H, Sandu CD, Richter K, Rexhepaj R, Gerlach U, Rong Q, Pfeifer K, Lang F. KCNQ1-dependent transport in renal and gastrointestinal epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 17864–17869, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vallon V, Huang DY, Grahammer F, Wyatt AW, Osswald H, Wulff P, Kuhl D, Lang F. SGK1 as a determinant of kidney function and salt intake in response to mineralocorticoid excess. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R395–R401, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vallon V, Wulff P, Huang DY, Loffing J, Volkl H, Kuhl D, Lang F. Role of Sgk1 in salt and potassium homeostasis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R4–R10, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vereninov AA, Vassilieva IO, Yurinskaya VE, Matveev VV, Glushankova LN, Lang F, Matskevitch JA. Differential transcription of ion transporters, NHE1, ATP1B1, NKCC1 in human peripheral blood lymphocytes activated to proliferation. Cell Physiol Biochem 11: 19–26, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Von Wowern F, Berglund G, Carlson J, Mansson H, Hedblad B, Melander O. Genetic variance of SGK-1 is associated with blood pressure, blood pressure change over time and strength of the insulin-diastolic blood pressure relationship. Kidney Int 68: 2164–2172, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wagner CA, Ott M, Klingel K, Beck S, Melzig J, Friedrich B, Wild KN, Broer S, Moschen I, Albers A, Waldegger S, Tummler B, Egan ME, Geibel JP, Kandolf R, Lang F. Effects of the serine/threonine kinase SGK1 on the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) and CFTR: implications for cystic fibrosis. Cell Physiol Biochem 11: 209–218, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Waldegger S, Barth P, Raber G, Lang F. Cloning and characterization of a putative human serine/threonine protein kinase transcriptionally modified during anisotonic and isotonic alterations of cell volume. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 4440–4445, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Waldegger S, Klingel K, Barth P, Sauter M, Rfer ML, Kandolf R, Lang F. h-sgk serine-threonine protein kinase gene as transcriptional target of transforming growth factor beta in human intestine. Gastroenterology 116: 1081–1088, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wang J, Barbry P, Maiyar AC, Rozansky DJ, Bhargava A, Leong M, Firestone GL, Pearce D. SGK integrates insulin and mineralocorticoid regulation of epithelial sodium transport. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F303–F313, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wolf SC, Schulze M, Sauter G, Risler T, Lang F. Endothelin-1 increases serum-glucose-regulated kinase-1 expression in smooth muscle cells. Biochem Pharmacol 71: 1175–1183, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wulff P, Vallon V, Huang DY, Volkl H, Yu F, Richter K, Jansen M, Schlunz M, Klingel K, Loffing J, Kauselmann G, Bosl MR, Lang F, Kuhl D. Impaired renal Na+ retention in the sgk1-knockout mouse. J Clin Invest 110: 1263–1268, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yoo D, Kim BY, Campo C, Nance L, King A, Maouyo D, Welling PA. Cell surface expression of the ROMK (Kir 1.1) channel is regulated by the aldosterone-induced kinase, SGK-1, and protein kinase A. J Biol Chem 278: 23066–23075, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yoshioka M, Kayo T, Ikeda T, Koizumi A. A novel locus, Mody4, distal to D7Mit189 on chromosome 7 determines early-onset NIDDM in nonobese C57BL/6 (Akita) mutant mice. Diabetes 46: 887–894, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yun CC. Concerted roles of SGK1 and the Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2 (NHERF2) in regulation of NHE3. Cell Physiol Biochem 13: 29–40, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yun CC, Chen Y, Lang F. Glucocorticoid activation of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 3 revisited. The roles of SGK1 and NHERF2. J Biol Chem 277: 7676–7683, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yun CC, Palmada M, Embark HM, Fedorenko O, Feng Y, Henke G, Setiawan I, Boehmer C, Weinman EJ, Sandrasagra S, Korbmacher C, Cohen P, Pearce D, Lang F. The serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase SGK1 and the Na+/H+ exchange regulating factor NHERF2 synergize to stimulate the renal outer medullary K+ channel ROMK1. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 2823–2830, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zecevic M, Heitzmann D, Camargo SM, Verrey F. SGK1 increases Na,K-ATP cell-surface expression and function in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Pflügers Arch 448: 29–35, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]