Abstract

Mutation of KRAS is a common initiating event in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Yet, the specific roles of KRAS-stimulated signaling pathways in the transformation of pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (PDECs), putative cells of origin for PDAC, remain unclear. Here we demonstrate that KRASG12D and BRAFV600E enhance PDEC proliferation, and increase survival after exposure to apoptotic stimuli in a manner dependent on MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling. Interestingly, we find that activation of PI3K/AKT signaling occurs downstream of MEK, and is dependent on the autocrine activation of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) receptor (IGF1R) by IGF2. Importantly, IGF1R inhibition impairs KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced survival, whereas ectopic IGF2 expression rescues KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-mediated survival downstream of MEK inhibition. Moreover, we demonstrate that KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced tumor formation in an orthotopic model requires IGF1R. Interestingly, we show that while individual inhibition of MEK or IGF1R does not sensitize PDAC cells to apoptosis, their concomitant inhibition reduces survival. Our findings identify a novel mechanism of PI3K/AKT activation downstream of activated KRAS, illustrate the importance of MEK/ERK, PI3K/AKT, and IGF1R signaling in pancreatic tumor initiation, and suggest potential therapeutic strategies for this malignancy.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic cancer is the 4th leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 5% (1). Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, PDAC, comprises the majority of pancreatic cancers and develops through a series of precursor lesions, known as pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias, or PanINs (2). This progression is marked by a series of genetic alterations, including activating mutations in the KRAS oncogene, and the loss of the INK4A, TP53, and MADH4 tumor suppressor genes (2–4). Of these alterations, mutational activation of KRAS occurs in approximately 95% of PDAC cases, and is present in early precursor lesions (4–6). The early occurrence and high incidence of KRAS mutation indicate that this is a critical step in the initiation of pancreatic tumor development. Mouse models for PDAC, generated through the pancreas-specific expression of an activated Kras allele, further support this hypothesis (7–9).

KRAS is a member of the Ras family of GTPases that cycle between inactive GDP- and active GTP-bound states (10). Mutations that disrupt the GTPase activity of KRAS, thereby rendering it constitutively active, are commonly observed in pancreatic cancer, resulting in the persistent activation of downstream signaling pathways (5). Perhaps the best-characterized KRAS-stimulated signaling pathway is the RAF/MEK/ERK signaling cascade (10). Members of the Raf family of serine/threonine kinases are key signal transducers in this pathway, and the gene BRAF, encoding the BRAF kinase, is commonly mutated in human malignancies including malignant melanoma and colorectal carcinoma (11). BRAF gene mutations are generally mutually exclusive with KRAS mutations; therefore, given the high rate of KRAS mutations in PDAC, BRAF mutations are infrequently seen in this disease (11). However, previous work by Kern and colleagues has shown that in the small subset of tumors that do not have activating KRAS mutations, 33% have activating mutations in BRAF (12). These findings raise the possibility that activating BRAF mutations may functionally substitute for KRAS gene mutations during pancreatic tumor initiation, yet the specific roles played by individual downstream effector pathways during pancreatic cancer initiation and progression remain unclear.

Pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (PDECs) are putative cells of origin for PDAC (2), and genetic manipulation of PDECs through the expression of oncogenes, or loss of tumor suppressor genes, provides a unique experimental system for modeling the initial transforming events in PDAC development (13–15). Additionally, in comparison to commonly used cell culture models such as NIH 3T3 cells, PDECs provide an excellent experimental model system for analyzing the signaling pathway perturbations that occur during the initiation of pancreatic tumorigenesis. Indeed, we have previously exploited this feature to demonstrate the effects of sonic hedgehog on the stimulation of the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling cascades (14).

We have also shown that activated KRAS promotes PDEC proliferation, as well as their survival after exposure to apoptotic stimuli (14). In addition, orthotopic implantation of KRASG12D-expressing PDECs that also lack the Ink4a/Arf tumor suppressor locus (alone or with concomitant Trp53 deletion) results in tumor formation (14). Using a similar experimental approach, Lee and Bar-Sagi recently demonstrated a role for Twist in bypassing oncogenic KRAS-induced cellular senescence (16). Thus, primary PDEC culture represents a unique system for the dissection of KRAS-induced signaling during pancreatic tumor initiation.

Therefore, in the present study we sought to elucidate the roles of the MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways in KRAS-mediated transformation of pancreatic epithelial cells, and to determine whether an activated BRAF molecule functionally substitutes for activated KRAS in this cell type. We find that both KRAS and BRAF stimulate the proliferation and survival of PDECs in culture, and that the induced survival is dependent on signaling through both the MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. Strikingly, we show that activation of AKT occurs downstream of the MEK/ERK pathway and the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF1R), and that PDECs expressing activated KRAS and BRAF depend upon IGF2-stimulated IGF1R signaling for survival after exposure to apoptotic stimuli. Moreover, PDAC cell lines remain dependent on these signaling pathways for survival after exposure to apoptotic stimuli. Finally, we demonstrate that KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced tumor formation in an orthotopic pancreatic tumor model is dependent on IGF1R expression. Collectively, these data provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying KRAS-mediated initiation of pancreatic tumorigenesis and pancreatic cancer cell survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Transgenic mice and animal care

The keratin-19-tv-a, Ink4a/Arflox/lox, Trp53lox/lox, and Ptf1a-cre strains have been previously described (14, 17–19). Nude mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington MA). All mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free facility with abundant food and water under guidelines approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation, culture, and infection of mouse PDECs

Isolation, culture, and infection of mouse PDECs was done as previously described (15). The RCAS-GFP, RCAS-KRASG12D-IRES-GFP, RCAS-BRAFV600E (V5 tag), RCAS-BRAF (V5 tag), and RCAS-IGF2 vectors have been described previously (14, 20, 21). Construction of the RCAS-BRAFV600E (myc-tagged) vector is described in the supplemental methods. All proliferation and survival assays were conducted as previously described (14). The MEK inhibitor PD980059, the PI3 kinase inhibitor LY2940002, and the IGF1R inhibitor AG1024 were used at final concentrations of 25μM, 20μM, and 20μM respectively. For survival assays, inhibitors were added to the culture media 1 hour prior to treatment with the apoptotic stimulus. Gene knockdown was achieved by infecting PDECs with pGIPZ- or pLKO-based lentiviruses encoding targeting shRNAs (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL). Infected PDECs were grown in media containing 2 μg/ml puromycin for at least 4 days. For serum starved shRNA-treated cells, puromycin was included in the media during serum starvation.

Culture and Treatment of Tumor Cell Lines

Cell lines were maintained as previously described (14). Murine cell lines were isolated and characterized upon isolation by immunoblotting and immunostaining in the Lewis lab. Low passage cells were frozen and used for subsequent experiments. Panc1 cells were obtained from ATCC. They were not authenticated in the Lewis lab. Small molecule inhibitors were used as described above for PDECs. Gemcitabine (Gemzar, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis IN) was used at a concentration of 50nM. Gene knockdown was performed as described for PDECs. Infected cells were in media containing 2μg/ml puromycin for at least 4 days. Proliferation and survival assays were conducted as previously described (14).

Immunoblotting

Cells for lysates were isolated in a 1mg/mL collagenase V solution (Sigma, St Louis MO), centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C, and incubated in lysis buffer on ice for 30 minutes. Lysis buffer composition is as previously described (22). Where noted, cells were serum starved for 48 hours prior to the generation of protein lysates. Protein lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Amersham, Arlington Heights IL). Immunoblotting was performed as described (23). Antibody dilutions can be found in the supplemental methods.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from serum starved PDECs using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA), purified with an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia CA), and treated with Turbo DNase (Ambion, Austin TX). cDNA was then generated using the Superscript III First Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA). For Kras expression analysis, 10ng of cDNA was mixed with TaqMan primers (Primer Set One: PN# Mm00517492_m1 and Primer Set Two PN# Mm01255197_m1) and TaqMan PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA) using the TaqMan standard protocol. For IGF- and EGF-family ligands, 10ng of cDNA was combined with SYBR Green Reaction Mix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD), and 500 nmoles of the appropriate primer pairs (IDT, Coralville, Iowa). Primer sequences can be found in supplemental methods. PCR amplification was conducted using an ABI 7300 Real Time PCR system using Applied Biosystems standard conditions.

Orthotopic implantation of PDECs

106 PDECs were resuspended in 10μL of matrigel and injected into the pancreata of nude mice as previously described (14). For studies involving the knockdown of the IGF1R, PDECs were infected with pGIPZ shRNA targeting either IGF1R or GFP (as described above) at least one week prior to orthotopic implantation.

Immunostaining

Immunostaining was performed as previously described (23). Antibody dilutions were as follows: Rabbit anti-Ki-67 (1:1000, Novocastro, Cat #NCL-Ki67p), Rabbit anti-mouse Pdx-1 (1:5000, gift of Chris Wright), Rabbit anti-Keratin-8 (1:50, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The two-tailed t test was used to compare the differences between groups. For all comparisons, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

KRASG12D and BRAFV600E enhance the proliferation and survival of pancreatic ductal epithelial cells

To investigate the effects of activated KRAS and BRAF on pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (PDECs), we isolated PDECs from transgenic mice expressing the avian leukosis virus subgroup A (ALV-A) receptor, TVA, under the control of the Keratin-19 (K19) gene promoter and enhancer elements (K19-tv-a) (14). PDECs were also isolated from K19-tv-a mice with pancreas-specific deletion of the Ink4a/Arf, and/or Trp53 tumor suppressor genes. TVA-positive PDECs were infected with RCAS viruses encoding Flag epitope-tagged KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, or GFP as a control (14). Infection of PDECs by RCAS-KrasG12D was confirmed by immunoblotting for the Flag epitope tag (Figure 1A). Importantly, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) demonstrated that expression of the ectopic KrasG12D resulted in only a 3-fold increase in mRNA levels (Supplemental Figure 1A). Elevated levels of BRAF in RCAS-BRAFV600E infected cells relative to RCAS-GFP infected controls were observed by immunoblotting (Figure 1B). This increased expression was specific to BRAF, as increased levels of ARAF and CRAF were not observed (Supplemental Figure 1B).

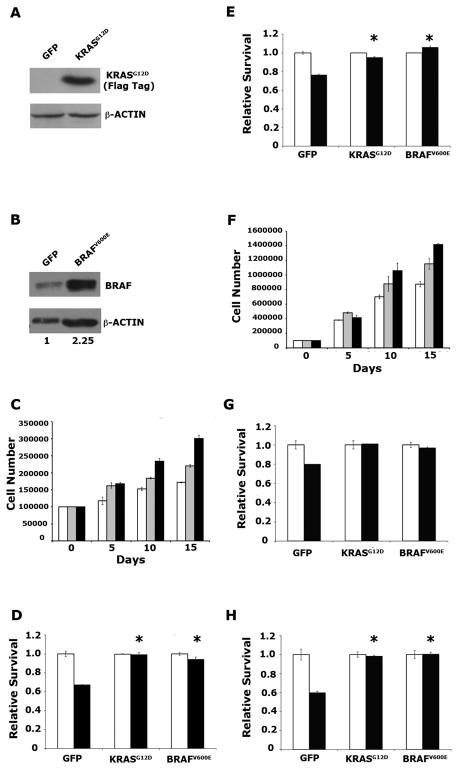

Figure 1. KRASG12D and BRAFV600E enhance proliferation and survival in pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (PDECs).

(A) Immunoblot confirming expression of ectopic FLAG epitope-tagged KRASG12D in Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs infected with RCAS-KRASG12D. β-actin is used as a loading control. (B) Immunoblot confirming elevated expression of BRAF in Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs infected with RCAS-BRAFV600E. β-actin is used as a loading control. Numbers represent relative BRAF/β-actin levels in RCAS-BRAFV600E-infected cells relative to RCAS-GFP infected controls. (C) Cell numbers of tumor suppressor wild type PDECs expressing KRASG12D (black bars), BRAFV600E (grey bars), or GFP (white bars) at indicated time points after plating. Results are representative of at least two experiments. (D, E) Viability of tumor suppressor wild type PDECs expressing KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, or GFP, treated with 100μM cycloheximide (D) or ultraviolet (UV) irradiation (E). White bars vehicle treated (or untreated) cells; black bars cycloheximide- or UV-treated cells. Values are normalized such that that viability of untreated cells is 1. Results are representative of at least two experiments. * p<0.01 compared to GFP expressing controls. (F) Cell numbers of Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs expressing KRASG12D (black bars), BRAFV600E (gray bars), or GFP (white bars) at indicated time points after plating. Results are representative of at least two experiments. (G) Viability of Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 double null PDECs expressing KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, or GFP, treated with 100μM cycloheximide, as measured by trypan blue exclusion. * p<0.01 compared to GFP expressing controls. (H) Viability of Ink4a/Arf null PDECs expressing KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, or GFP, following UV irradiation. White bars vehicle treated (or untreated) cells; black bars cycloheximide- or UV-treated cells. Values are normalized such that that viability of untreated cells is 1. Results are representative of at least two experiments. * p<0.01 compared to GFP expressing controls. All error bars, SD.

We next investigated the effect of activated KRAS and BRAF on the proliferation of PDECs. As previously shown, KRASG12D increased PDEC proliferation relative to GFP-expressing controls, and this effect was similar in both tumor suppressor wild type and Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs (Figure 1C and 1F) (14). BRAFV600E also increased PDEC proliferation relative to GFP controls, but notably this increase was less than that induced by KRASG12D (Figure 1C and 1F). In addition, we observed that PDECs infected with RCAS viruses encoding wild type BRAF did not display increased proliferation relative to GFP-expressing PDECs, indicating that mutational activation of BRAF is important for its ability to stimulate proliferation in PDECs (Supplemental Figure 1C, D).

We next determined the effect of KRASG12D and BRAFV600E expression on PDEC survival when challenged with an apoptotic stimulus. For these assays, PDECs were treated with ultraviolet (UV) irradiation or cycloheximide, a cytotoxic agent that has been previously shown to cause apoptosis in PDECs and pancreatic cancer cells (14, 24). We found that both KRASG12D and BRAFV600E promoted PDEC survival after exposure to UV irradiation and cycloheximide (Figure 1D, 1E, 1G, and 1H). Moreover, these effects were irrespective of tumor suppressor status, and similar results were obtained in wild type (Figure 1D and 1E) as well as Ink4a/Arf (1H) and Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs (1G). Of note, UV-induced apoptosis in PDECs is p53-dependent, thus KRASG12D and BRAFV600E block both p53-dependent and p53-independent apoptosis. In addition, we observed increased survival, relative to GFP controls, in PDECs expressing wild type BRAF following cycloheximide treatment (Supplemental Figure 1E, F). These findings demonstrate that elevated BRAF expression, both mutant and wild type, is able to functionally substitute for activated KRAS to promote PDEC survival, and suggest an important role for the RAF/MEK/ERK cascade in the survival of pancreatic epithelial cells.

Given that tumor suppressor gene status did not impact the proliferation and survival phenotypes, we used tumor suppressor deficient PDECs for subsequent experiments as they were easier to establish and grow in culture.

Expression of KRASG12D or BRAFV600E Induces Pancreatic Tumor Formation

We have previously shown that the expression of KRASG12D in PDECs lacking Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 is sufficient to induce tumor formation in an orthotopic mouse model (14). Therefore, having demonstrated that BRAFV600E expression in PDECs is sufficient to at least partially recapitulate the increased proliferation and survival seen in KRASG12D expressing PDECs, we next sought to determine if the expression of BRAFV600E in PDECs was sufficient to induce tumor formation. We found that implantation of KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs resulted in efficient pancreatic tumor formation, whereas the implantation of GFP expressing cells did not (Table 1). In the experiment shown in Table 1, mice injected with KRASG12D-expressing PDECs formed tumors sooner than animals injected with BRAFV600E-expressing cells (4 weeks versus 8 weeks). However, this accelerated tumor formation by KRASG12D, relative to BRAFV600E, was not consistently observed across multiple replicates of the experiment. Thus, we infer that KRASG12D and BRAFV600E induce tumor formation with similar kinetics in the orthotopic model.

Table 1.

Tumor formation by KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 double null PDECs.

| Cells Implanted | Tumor Incidence | Time to Tumor Development (Weeks) | Average Tumor Volume (SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFP | 1/6 | 8 | 400mm3 (±0) |

| KRASG12D | 6/6 | 4 | 1679mm3 (±607) |

| BRAFV600E | 5/6 | 8 | 1197mm3 (±430) |

Tumor volume calculated using the formula LxWxH.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tumor tissue showed that transplantation of both KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing cells primarily resulted in the formation of undifferentiated carcinomas (Supplemental Figure 2A), occasionally with entrapped normal pancreatic tissue (Supplemental Figure 2B) and regions with glandular differentiation (Supplemental Figure 2C), consistent with our previously published findings (14). Surprisingly, tumors formed after the injection of BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs additionally contained regions with features of skeletal, cartilaginous, or bone differentiation (Supplemental Figure 2D). Consistent with this, KRAS-induced tumors displayed cells with detectable cytokeratin 8 staining throughout the tumor, whereas BRAF-induced tumors displayed cytokeratin 8 staining only in glandular structures (Supplemental Figure 2E, F). The mechanisms underlying this mesenchymal-like differentiation in BRAFV600E-induced tumors are undetermined.

Collectively, these data demonstrate that although there are subtle differences between KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced pancreatic tumors, the expression of BRAFV600E in PDECs is largely able to substitute for the expression of KRASG12D during pancreatic tumor initiation.

Signaling downstream of MEK and PI3K is necessary for survival in KRASG12D and BRAFV600E expressing PDECs

We have previously shown that enhanced survival in PDECs induced by ectopic sonic hedgehog (SHH) expression is dependent on the PI3K/AKT signaling axis, but not the MEK/ERK pathway (14). To interrogate the roles of these signaling cascades in KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-mediated survival, we exposed PDECs to apoptotic stimuli in the presence of the MEK inhibitor PD98059 or the PI3K inhibitor LY294002. We found that treatment with either of these inhibitors abrogated KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-enhanced survival after apoptotic challenge, irrespective of the apoptotic stimulus used (Figure 2A, B). By contrast, and consistent with our published data, SHH-expressing PDECs displayed reduced survival when the PI3K pathway, but not the MEK/ERK pathway, was blocked (Figure 2A,B). Similar results were obtained when PDECs were treated with Rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR signaling (Supplemental Figure 3A). Of note, combined inhibition of MEK and PI3K did not result in a further diminution of survival, indicating that inhibition of either pathway resulted in the maximum impairment in survival measurable by this assay (Supplemental Figure 3B, C).

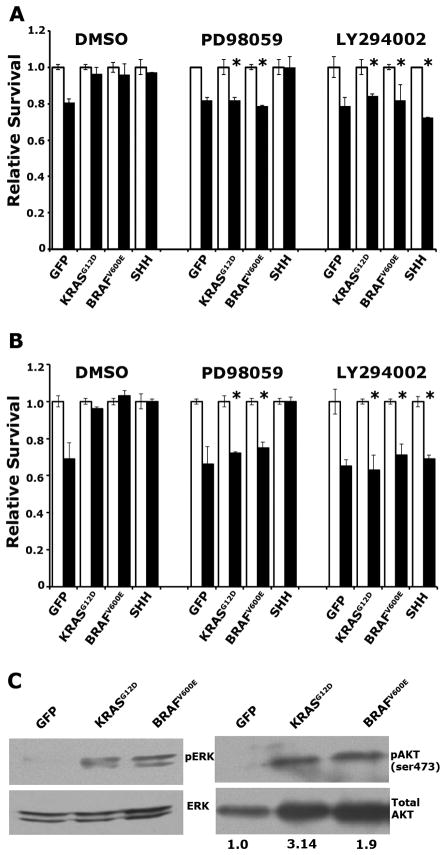

Figure 2. KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced survival in PDECs requires MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling.

(A) Viability Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 double null of PDECs expressing KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, SHH, or GFP, treated with DMSO, PD98059, or LY2900042 plus 100μM cycloheximide. * p<0.05 compared to DMSO treated cells of identical genotype. (B) Viability of Ink4a/Arf null PDECs expressing KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, SHH, or GFP, treated with DMSO, PD98059, or LY2900042 plus UV irradiation. White bars vehicle treated (or untreated) cells; black bars cycloheximide or UV treated cells. Values are normalized such that viability of untreated cells is 1. Results are representative of at least two experiments. * p<0.05 compared to DMSO treated cells of identical genotype. (C) Immunoblot analysis of ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) and AKT (ser473) phosphorylation in serum starved KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, and GFP expressing Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs. Values indicate the ratio of phosphorylated AKT relative to total AKT as measured by densitometry and normalized such that GFP expressing PDECs have a ratio of 1. All error bars, SD.

Expression of KRASG12D and BRAFV600E results in activation of the MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling cascades

The dependence of KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs on both the MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways for survival was unexpected, since BRAFV600E directly stimulates the MEK/ERK signaling cascade, but not the PI3K/AKT pathway. Therefore, we ascertained the activation status of these signaling pathways in PDECs expressing KRASG12D or BRAFV600E. PDECs were serum starved for 48 hours to eliminate pathway activation induced by exogenous growth factors, and protein lysates generated from the serum-starved cells. Immunoblotting of these lysates demonstrated increased ratios of phosphorylated AKT (pAKT; at ser473) to total AKT, and phosphorylated ERK1 and ERK2 (pERK; at Thr202/Tyr204) to total ERK, in KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs relative to GFP expressing controls, confirming activation of the MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways (Figure 2C). These data suggest that BRAFV600E, and potentially KRASG12D, stimulate PI3K/AKT signaling in an indirect manner. Interestingly, we also observed increased levels of total AKT in KRAS- and BRAF-expressing PDECs relative to GFP controls (Figure 2C). Analysis of mRNA and protein levels of AKT family members indicated that this regulation occurred by translational or post-translational mechanisms (VAA and BCL, unpublished observations).

Activation of PI3K/AKT signaling in KRASG12D and BRAFV600E expressing PDECs depends on signaling through IGF1R

Since BRAF does not directly activate PI3K, we next sought to determine the mechanism by which BRAFV600E stimulates the PI3K/AKT pathway in PDECs. We hypothesized that PI3K/AKT activation occurs downstream of the RAF/MEK/ERK signaling cascade, potentially through the activation of autocrine growth factor signaling. Previous work showed that melanoma cells expressing mutant NRAS or BRAF respond to treatment with an IGF1R inhibitor; therefore, we hypothesized that IGF1R could be activated downstream of RAF/MEK/ERK signaling (25).

We first assessed the levels of IGF1R ligands in serum starved PDECs expressing KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, or GFP by qRT-PCR. We found robustly increased levels of Igf2 mRNA in both KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing cells relative to GFP-expressing controls, and a modest increase in Igf1 mRNA levels (Figure 3A). Insulin mRNA levels were unaffected by the expression of KRASG12D and BRAFV600E. Immunoblotting confirmed increased IGF2 levels in KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs relative to GFP-expressing controls (Figure 3B). Moreover, immunoblotting demonstrated increased phosphorylation of IGF1R, indicative of receptor activation, in protein lysates from serum starved KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing cells (Figure 3C). Consistent with our hypothesis that Igf2 gene expression is stimulated downstream of the MEK/ERK cascade, blockade of MEK, but not PI3K, reduced Igf2 mRNA levels in KRASG12D-expressing PDECs (Figure 3D, and Supplemental Figure 4A). In contrast to the stimulation of IGF gene expression, we did not see a similar increase in the expression level of any EGF family ligands by qRT-PCR (Supplemental Figure 4B), indicating that this increase is specific to IGF ligands.

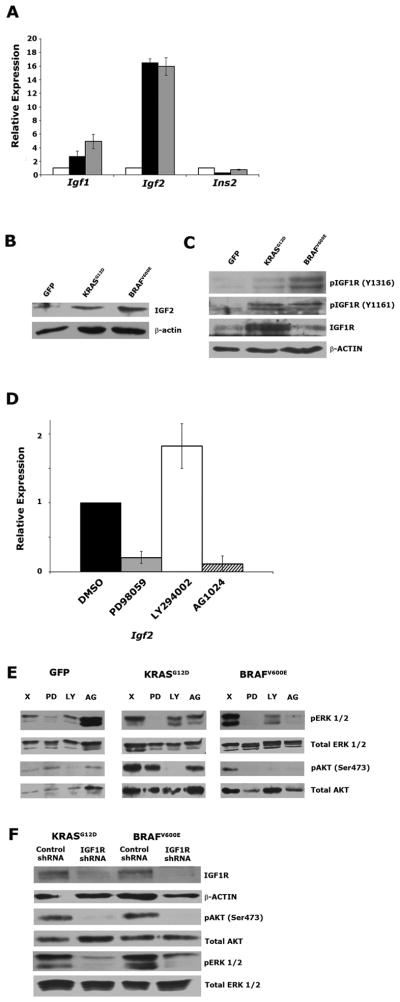

Figure 3. AKT phosphorylation in KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs depends on signaling through IGF1R.

(A) Quantitative RT-PCR measurement of Igf2 mRNA in KRASG12D-, BRAFV600E-, and GFP-expressing Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs (black, gray, and white bars respectively). β-actin is used as an endogenous control. Ligand expression in GFP-expressing cells is normalized to 1. (B) Immunoblot analysis of IGF2 levels in serum starved KRASG12D-, BRAFV600E-, and GFP-expressing Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs. β-actin is used as a loading control. (C) Immunoblot analysis of IGF1R phosphorylation in serum starved KRASG12D-, BRAFV600E-, and GFP-expressing Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs. Total IGF1R levels are also shown. β-actin is used as a loading control. (D) Quantitative RT-PCR measurement of Igf2 mRNA in serum starved in KRASG12D-expressing Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs treated with PD98059, LY294002, and AG1024. β-actin is used as an endogenous control. (E) Immunoblot analysis of ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) and AKT (ser473) phosphorylation in serum starved KRASG12D-, BRAFV600E-, and GFP-expressing Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs treated with PD98059, LY294002, and AG1024. (F) Immunoblot analysis of ERK (Thr202/Tyr204) and AKT (ser473) phosphorylation, as well as IGF1R expression in serum starved KRASG12D-, BRAFV600E-, and GFP-expressing Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs expressing an IGF1R-targeting shRNA. All error bars, SD.

To determine if AKT activation in KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs depends upon signaling through MEK, and subsequently through IGF1R, we inhibited MEK, PI3K, and IGF1R, and ascertained the impact on ERK and AKT phosphorylation via immunoblot. As expected, we found that ERK phosphorylation (pERK) is dramatically reduced in the presence of PD98059. Surprisingly, we found that pERK levels are also reduced in the presence of LY294002 and the IGF1R inhibitor AG1024 in KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs, but not GFP controls (Figure 3E). These results suggest that a potential feedback loop between the RAF/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways specifically occurs downstream of KRASG12D and BRAFV600E in PDECs.

Treatment with LY2904002 reduced AKT phosphorylation at Ser 473 (pAKT) (Figure 3E). Interestingly, pAKT levels were also strongly reduced in BRAFV600E-expressing cells treated with PD98059 or AG1024, demonstrating that AKT activation lies downstream of MEK and IGF1R (Figure 3E). Treatment of KRASG12D-expressing PDECs with LY294002 robustly reduced pAKT levels, while PD98059 and AG1024 had a measureable, but more modest impact (Figure 3E).

To further assess the impact of IGF1R on the MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, we utilized shRNA-mediated knockdown to reduce IGF1R levels and downstream signaling. Immunoblotting confirmed efficient knockdown of IGF1R in PDECs infected with a lentivirus encoding an IGF1R-targeting shRNA relative to PDECs expressing a non-silencing control (Figure 3F). Immunoblotting demonstrated that pERK and pAKT levels were strongly inhibited in KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs following IGF1R knockdown (Figure 3F). These findings suggest that AKT activation occurs downstream of IGF1R. Coupled with our finding that IGF2 induction occurs downstream of MEK (Figure 3D), these data further suggest that a MEK-IGF2-IGF1R signaling axis regulates AKT activation downstream of activated KRAS and BRAF in primary pancreatic ductal epithelial cells.

IGF1R inhibition impairs KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-mediated survival

We next investigated the impact of IGF1R inhibition on PDEC survival. We found that AG1024 inhibited the ability of KRASG12D and BRAFV600E to enhance survival in PDECs challenged with either cycloheximide (Figure 4A) or UV irradiation (Figure 4B). Importantly, survival in SHH-expressing PDECs was not impacted by AG1024 treatment, consistent with SHH-enhanced survival occurring in a MEK-independent manner, and in line with the hypothesis that IGF1R activation occurs downstream of MEK (Figure 4A, B). Similarly, IGF1R knockdown impaired survival after apoptotic challenge (Figure 4C). Interestingly, insulin receptor (IR) knockdown resulted in a reproducible, but statistically insignificant reduction in survival after apoptotic challenge, suggesting a potential role for IGF1R/IR heterodimers in mediating IGF2-stimulated signaling (Figure 4C).

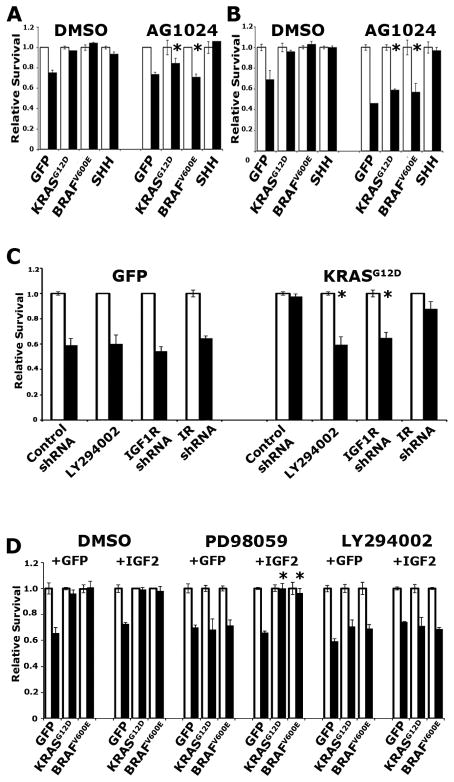

Figure 4. KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced survival in PDECs requires IGF1R signaling.

(A) Viability of Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 double null PDECs expressing KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, SHH, or GFP treated with DMSO or AG1024, plus 100μM cycloheximide. * p<0.01 compared to DMSO treated cells of identical genotype. (B) Viability of Ink4a/Arf null PDECs expressing KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, SHH, or GFP treated with DMSO or AG1024 plus UV irradiation as measured by trypan blue exclusion. White bars untreated cells, black bars UV treated cells. Values are normalized such that viability of untreated cells is 1. Results are representative of at least two experiments. * p<0.01 compared to DMSO treated cells of identical genotype. (C) Impact of IGF1R- and IR-targeting shRNAs on the viability of KRASG12D- and GFP-expressing Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 double null PDECs treated with 100μM cycloheximide. * p<0.05 compared to cells treated with control shRNA. (D) Viability of Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null PDECs expressing KRASG12D, BRAFV600E, or GFP, as well as ectopic IGF2 (or GFP as a control), following treatment with 100μM cycloheximide and the indicated inhibitors. White bars vehicle treated cells, black bars cycloheximide treated cells. Values are normalized such that viability of untreated cells is 1. Results are representative of at least two experiments. * p<0.05 compared to GFP expressing cells treated with PD98059. All error bars, SD.

If the hypothesis that IGF2 stimulates IGF1R-mediated signaling downstream of MEK is correct, then ectopic expression of IGF2 in KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing cells should rescue survival in the setting of MEK inhibition, but not PI3K inhibition. To test this hypothesis, we infected KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs with RCAS viruses encoding IGF2 or GFP as a control, and challenged these cells with apoptotic stimuli in the presence of specific signaling pathway inhibitors. Consistent with our hypothesis, we found that ectopic IGF2 expression rescued KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced survival in PDECs after challenge with cycloheximide in the presence of PD98059, but not LY294002 (Figure 4D). Importantly, IGF2 expression by itself was not sufficient to promote the survival of PDECs after apoptotic challenge (Figure 4D), demonstrating that other molecules and pathways regulated by oncogenic KRAS and BRAF are required to promote cell survival.

IGF1R is required for KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis

The data above demonstrated a critical role for IGF1R-mediated signaling in the survival of PDECs. To determine whether this effect contributes to KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced transformation of pancreatic epithelial cells, we used targeting shRNAs to knock down IGF1R expression in Ink4a/Arf and Trp53 double null PDECs expressing either KRASG12D or BRAFV600E. Effective shRNA-mediated knockdown was confirmed by immunoblot (Supplemental Figure 5A). Orthotopic implantation of 106 PDECs resulted in efficient tumor formation in KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-expressing PDECs, whereas tumor formation was robustly inhibited in mice implanted with cells that simultaneously expressed IGF1R shRNA (Table 2). Interestingly, if mice implanted with cells expressing the IGF1R-targeting shRNA were allowed to remain on the study for a longer period of time, tumors eventually formed. Analysis of IGF1R expression in these tumors demonstrated equivalent IGF1R levels to tumors formed by cells expressing a non-silencing control (Supplemental Figure 5B). Together, these data suggest that IGF1R is required for KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis.

Table 2.

IGF1R knockdown impairs KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis.

| Cells Implanted | Tumor Incidence | Time to Tumor Development (Weeks) | Average Tumor Volume (SEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| KRASG12D Control | 4/5 | 7 | 576mm3 (±436) |

| KRASG12D IGF1R shRNA | 0/6 | 7 | N/A |

| BRAFV600E Control | 6/6 | 7 | 1211mm3 (±239) |

| BRAFV600E IGF1R shRNA | 5/6 | 7 | 72mm3 (±20) |

Tumor volume calculated using the formula LxWxH.

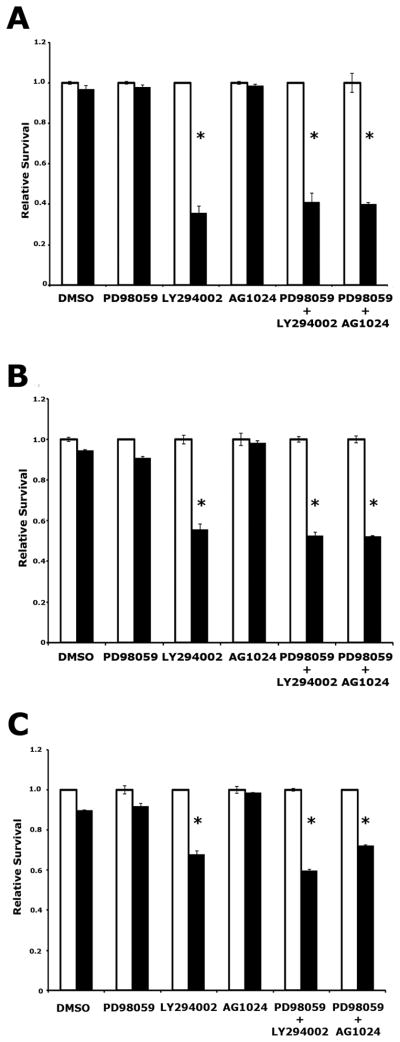

Combined MEK and IGF1R inhibition impairs the survival of pancreatic cancer cells

Given that IGF1R is required for PDEC survival after apoptotic challenge and for KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis, we asked whether IGF1R is similarly required for the survival of pancreatic cancer cells. We first assessed the effect of IGF1R inhibition on the proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells derived from our orthotopic model. Consistent with our previously published data (14), we found that inhibition of MEK or PI3K strongly impaired the proliferation of the 170#3 cell line that harbors KRASG12D and deletion of Ink4a/Arf and Trp53 (Supplemental Figure 6A). Similarly, inhibition of IGF1R with AG1024 also reduced proliferation in this cell line (Supplemental Figure 6A).

We next determined the effect of MEK inhibition, PI3K inhibition, and IGF1R inhibition on the survival of pancreatic cancer cells. We found that inhibition of PI3K in 170#3 cells reduced survival after challenge with cycloheximide (Figure 5A). Interestingly, in contrast to our findings in PDECs, we found that individual inhibition of MEK or IGF1R did not significantly impact survival after apoptotic challenge in the 170#3 cell line (Figure 5A). However, combined inhibition of MEK and IGF1R reduced survival to the levels seen with PI3K inhibition (Figure 5A). Similar results were observed in the human PDAC cell line Panc1 (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Combined inhibition of MEK and IGF1R impairs pancreatic cancer cell survival.

(A) Viability of the KRASG12D-expressing, Ink4a/Arf, Trp53 null murine pancreatic cancer cell line 170#3 following treatment with 100μM cycloheximide and the indicated inhibitors. White bars vehicle treated cells; black bars cycloheximide treated cells. Values are normalized such that that viability of untreated cells is 1. Results are representative of at least two experiments. * p<0.05 compared to DMSO treated cells. (B) Viability of the human Panc1 pancreatic cancer cell line following treatment with 100μM cycloheximide and the indicated inhibitors. White bars vehicle treated cells; black bars cycloheximide treated cells. Values are normalized such that that viability of untreated cells is 1. Results are representative of at least two experiments. * p<0.05 compared to DMSO treated cells.

(C) Viability of the 170#3 cell line following treatment with 50nM gemcitabine and the indicated inhibitors. White bars vehicle treated cells; black bars gemcitabine treated cells. Values are normalized such that that viability of untreated cells is 1. Results are representative of at least two experiments. * p<0.05 compared to DMSO treated cells. All error bars, SD.

To confirm that this phenomenon occurs following exposure to a clinically relevant compound, we treated 170#3 cells with a 50nM concentration of the standard of care chemotherapeutic gemcitabine (26), a concentration that normally fails to elicit significant death in this cell line, in combination with inhibition of MEK, PI3K, and IGF1R. We found that PI3K inhibition, or combined inhibition of MEK and IGF1R (but not inhibition of MEK or IGF1R alone), sensitized PDAC cells to gemcitabine (Figure 5C). Similar results were obtained when IGF1R knockdown was combined with small molecule-mediated inhibition of MEK, demonstrating that these findings are not the consequence of toxicity induced by simultaneous exposure to AG1024 and PD98059 (Supplemental Figure 6B, C). Thus, our data indicate that combined inhibition of MEK and IGF1R sensitizes pancreatic cancer cells to apoptotic stimuli, suggesting that combined inhibition of these signaling molecules may represent a novel therapeutic strategy for this malignancy.

DISCUSSION

Activating mutations in KRAS are commonly identified in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), and are present in early precursor PanIN lesions (5, 27, 28). Given the critical importance of initiating oncogenic lesions in oncogene addiction, targeted inhibition of mutant KRAS is an attractive therapeutic strategy (29–34). However, previous attempts to directly target KRAS have not been successful (10). Therefore, attention has shifted towards targeting downstream effector proteins. Yet, the roles of specific signaling cascades downstream of activated KRAS during pancreatic tumor initiation remain unclear. Therefore, in this study we elucidated the roles of the MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling cascades in mediating the transformation of primary pancreatic ductal epithelial cells (PDECs), a presumptive cell of origin for PDAC.

Consistent with our previously published findings (14), we demonstrate that KRASG12D promotes the proliferation of and survival of PDECs. Intriguingly, an activated BRAF molecule, BRAFV600E, likewise stimulates the proliferation of PDECs, but does so less potently than KRASG12D, suggesting that other signaling cascades induced by KRASG12D contribute to the induction of PDEC proliferation. By contrast, BRAFV600E and KRASG12D promote survival to a similar extent, suggesting a central role for the MEK/ERK signaling cascade in KRAS-induced survival in primary pancreatic epithelial cells. Further, expression of KRASG12D or BRAFV600E in PDECs results in tumor development, with similar kinetics, in an orthotopic pancreatic cancer mouse model. Cumulatively, these data are consistent with the reported observation that a fraction of KRAS wild type pancreatic cancers contain activating mutations in BRAF (12), and are consistent with a prominent role for the MEK/ERK signaling cascade in pancreatic epithelial cell transformation and pancreatic tumor initiation. Indeed recent work by Collisson et al highlighted a central role for MEK/ERK signaling in pancreatic cancer cells and demonstrated that BRAFV600E potently stimulates the initiation of pancreatic tumorigenesis in vivo (35).

Our data also demonstrate that the survival promoted by activated KRAS and BRAF is dependent on both the MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling cascades. Intriguingly, we identified that IGF1R is also required for KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-stimulated cell survival. Significantly, our dissection of the signaling pathways activated by KRASG12D and BRAFV600E demonstrated that the activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway lies downstream of both MEK and IGF1R. Indeed, we showed that Igf2 expression is induced downstream of MEK, resulting in the autocrine activation of IGF1R and subsequent stimulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway. Thus, in primary pancreatic epithelial cells, KRASG12D-induced PI3K/AKT activation occurs predominantly through an indirect mechanism rather than via direct activation of PI3K by KRAS.

Interestingly, the effect of IGF1R knockdown on pAKT levels was more robust than that observed upon AG1024 treatment. These data suggest that knockdown of IGF1R more completely inhibits downstream signaling than treatment with AG1024 at the concentration utilized for these studies (20μM), a concentration that inhibits IGF1R, but not insulin receptors (IR) (36, 37). However, our data also demonstrated that knockdown of the insulin receptor produced a modest but measurable effect on sensitivity to apoptotic stimuli, suggesting that IGF1R/IR heterodimers may, in part, mediate signals downstream of IGF ligands. In vivo genetic studies may shed light on the role of IR on KRASG12D-driven pancreatic tumorigenesis.

Significantly, shRNA-mediated knockdown of IGF1R inhibited KRASG12D- and BRAFV600E-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis in an orthotopic mouse model, underlining the importance of IGF1R signaling for pancreatic tumorigenesis. Moreover, tumors that eventually developed in mice injected with cells expressing IGF1R-targeting shRNAs displayed normal levels of IGF1R, strongly suggesting that this receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) is required for KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Together, our data provide the novel observation that IGF1R is activated downstream of mutant KRAS in primary pancreatic epithelial cells via an autocrine signaling loop, and that IGF1R-mediated signaling is required to promote KRAS-induced tumor initiation. Moreover, our findings provide functional insight into the reported observation of elevated IGF and IGF1R expression in PDAC, and the association of elevated IGF1R levels with poor prognosis in PDAC (38–40).

Our studies also highlight the importance of cellular context in evaluating the roles of signaling molecules at specific stages of pancreatic tumor development. For example, despite the impact of MEK and IGF1R inhibition on survival in PDECs, we found that individual blockade of these signaling proteins did not sensitize pancreatic cancer cells to apoptotic stimuli. Indeed, in contrast to our findings in PDECs, inhibition of MEK or IGF1R did not impact AKT phosphorylation in pancreatic cancer cells, suggesting that genetic and/or epigenetic changes that occurred during transformation reduced the reliance on MEK and IGF1R for PI3K/AKT pathway activation. Thus, our identification of IGF1R as a key signaling molecule stimulated downstream of MEK/ERK signaling likely would not have occurred in immortalized fibroblasts or cancer cell lines. Therefore, additional studies analyzing primary pancreatic epithelial cells may be uniquely suited to the identification of other critical molecules required for pancreatic tumor initiation.

In contrast to the insensitivity of pancreatic cancer cells to inhibition of MEK or IGF1R, their combined inhibition sensitized human and mouse pancreatic cancer cell lines to apoptotic stimuli. These findings suggest that combined inhibition of MEK and IGF1R could potentially be part of new therapeutic regimens for the treatment of PDAC. Significantly, there are several ongoing clinical trials utilizing IGF1R inhibition in many solid tumors, including in PDAC where it is used in combination with gemcitabine (41–43). Our results suggest that simultaneous inhibition of MEK and IGF1R in combination with gemcitabine may potentially be more efficacious. Interestingly, our findings regarding the efficacy of combined inhibition of MEK and IGF1R are consistent with recently published observations by Engelman and colleagues who found that RTKs, particularly IGF1R, controlled PI3K activation in KRAS mutant colon cancer cell lines, and that combined inhibition of MEK and IGF1R led to tumor regression in a xenograft model (44). Indeed, RTKs have emerged as common mediators of resistance to BRAF targeted therapies in melanoma and colorectal cancer (45–48). In many instances, these RTKs reactivate MEK/ERK signaling independently of BRAF, and in that way confer resistance to BRAF inhibitors. In other instances, these RTKs drive enhanced survival through the activation of PI3K/AKT signaling, and potentially other mechanisms. Indeed, consistent with our findings combined MEK/IGF1R inhibition or combined MEK/PI3K inhibition induced massive apoptosis in BRAF inhibitor resistant cells (44, 48). Our studies raise the possibility that these mediators of resistance may be commonly activated downstream of MEK/ERK signaling during the early phases of tumorigenesis.

In total, our data demonstrate a critical role for IGF1R signaling in pancreatic tumor initiation and pancreatic cancer cell survival, and suggest that IGF1R is a viable target in combinatorial therapeutic strategies in PDAC. Further studies regarding the role of the IRS adapter proteins and other downstream molecules may shed further light on the role of IGF1R-stimulated signaling cascades in pancreatic tumorigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: CA113896 and CA155784 from the NIH to BCL; the Verville Foundation to BCL. Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center grant P30 DK32520.

Supported by Public Health Service grants CA113896 and CA155784 from the National Cancer Institute to BCL, and by the Verville Foundation. BCL is a member of the UMMS DERC (P30 DK32520).

The authors thank Victor Adelanwa and Sharon Magnusson for technical assistance; Richard Marais and Sheri Holmen for reagents; Lucio Castilla, Roger Davis, Michelle Kelliher, and Leslie Shaw for critical discussion and evaluation of the work; and members of the Lewis lab for critical reading of the manuscript and helpful discussions.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hruban RH, Goggins M, Parsons J, Kern SE. Progression model for pancreatic cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2000;6:2969–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nature reviews Cancer. 2002;2:897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hezel AF, Kimmelman AC, Stanger BZ, Bardeesy N, Depinho RA. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes & development. 2006;20:1218–49. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almoguera C, Shibata D, Forrester K, Martin J, Arnheim N, Perucho M. Most human carcinomas of the exocrine pancreas contain mutant c-K-ras genes. Cell. 1988;53:549–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90571-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanda M, Matthaei H, Wu J, Hong SM, Yu J, Borges M, et al. Presence of somatic mutations in most early-stage pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:730–3. e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguirre AJ, Bardeesy N, Sinha M, Lopez L, Tuveson DA, Horner J, et al. Activated Kras and Ink4a/Arf deficiency cooperate to produce metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes & development. 2003;17:3112–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerra C, Mijimolle N, Dhawahir A, Dubus P, Barradas M, Serrano M, et al. Tumor induction by an endogenous K-ras oncogene is highly dependent on cellular context. Cancer cell. 2003;4:111–20. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer cell. 2003;4:437–50. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nature reviews Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417:949–54. doi: 10.1038/nature00766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calhoun ES, Jones JB, Ashfaq R, Adsay V, Baker SJ, Valentine V, et al. BRAF and FBXW7 (CDC4, FBW7, AGO, SEL10) mutations in distinct subsets of pancreatic cancer: potential therapeutic targets. The American journal of pathology. 2003;163:1255–60. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63485-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agbunag C, Bar-Sagi D. Oncogenic K-ras drives cell cycle progression and phenotypic conversion of primary pancreatic duct epithelial cells. Cancer research. 2004;64:5659–63. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morton JP, Mongeau ME, Klimstra DS, Morris JP, Lee YC, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Sonic hedgehog acts at multiple stages during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:5103–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701158104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber FS, Deramaudt TB, Brunner TB, Boretti MI, Gooch KJ, Stoffers DA, et al. Successful growth and characterization of mouse pancreatic ductal cells: functional properties of the Ki-RAS(G12V) oncogene. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:250–60. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KE, Bar-Sagi D. Oncogenic KRas suppresses inflammation-associated senescence of pancreatic ductal cells. Cancer cell. 2010;18:448–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonkers J, Meuwissen R, van der Gulden H, Peterse H, van der Valk M, Berns A. Synergistic tumor suppressor activity of BRCA2 and p53 in a conditional mouse model for breast cancer. Nature genetics. 2001;29:418–25. doi: 10.1038/ng747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawaguchi Y, Cooper B, Gannon M, Ray M, MacDonald RJ, Wright CV. The role of the transcriptional regulator Ptf1a in converting intestinal to pancreatic progenitors. Nature genetics. 2002;32:128–34. doi: 10.1038/ng959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krimpenfort P, Quon KC, Mooi WJ, Loonstra A, Berns A. Loss of p16Ink4a confers susceptibility to metastatic melanoma in mice. Nature. 2001;413:83–6. doi: 10.1038/35092584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson JP, VanBrocklin MW, Guilbeault AR, Signorelli DL, Brandner S, Holmen SL. Activated BRAF induces gliomas in mice when combined with Ink4a/Arf loss or Akt activation. Oncogene. 2010;29:335–44. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao G, Pedone CA, Del Valle L, Reiss K, Holland EC, Fults DW. Sonic hedgehog and insulin-like growth factor signaling synergize to induce medulloblastoma formation from nestin-expressing neural progenitors in mice. Oncogene. 2004;23:6156–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y, Xia F, Hermance N, Mabb A, Simonson S, Morrissey S, et al. A cytosolic ATM/NEMO/RIP1 complex recruits TAK1 to mediate the NF-kappaB and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/MAPK-activated protein 2 responses to DNA damage. Molecular and cellular biology. 2011;31:2774–86. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01139-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis BC, Klimstra DS, Varmus HE. The c-myc and PyMT oncogenes induce different tumor types in a somatic mouse model for pancreatic cancer. Genes & development. 2003;17:3127–38. doi: 10.1101/gad.1140403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koehler JA, Drucker DJ. Activation of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling does not modify the growth or apoptosis of human pancreatic cancer cells. Diabetes. 2006;55:1369–79. doi: 10.2337/db05-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeh AH, Bohula EA, Macaulay VM. Human melanoma cells expressing V600E B-RAF are susceptible to IGF1R targeting by small interfering RNAs. Oncogene. 2006;25:6574–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burris HA, 3rd, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15:2403–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tada M, Omata M, Kawai S, Saisho H, Ohto M, Saiki RK, et al. Detection of ras gene mutations in pancreatic juice and peripheral blood of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer research. 1993;53:2472–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe H, Sawabu N, Ohta H, Satomura Y, Yamakawa O, Motoo Y, et al. Identification of K-ras oncogene mutations in the pure pancreatic juice of patients with ductal pancreatic cancers. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1993;84:961–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1993.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, Kantarjian H, Resta DJ, Reese SF, Ford JM, et al. Activity of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;344:1038–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Druker BJ, Talpaz M, Resta DJ, Peng B, Buchdunger E, Ford JM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;344:1031–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104053441401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363:809–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;350:2129–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, Tracy S, Greulich H, Gabriel S, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:13306–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Collisson EA, Trejo CL, Silva JM, Gu S, Korkola JE, Heiser LM, et al. A Central Role for RAF->MEK->ERK Signaling in the Genesis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 2012 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.LeRoith D, Roberts CT., Jr The insulin-like growth factor system and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2003;195:127–37. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(03)00159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parrizas M, Gazit A, Levitzki A, Wertheimer E, LeRoith D. Specific inhibition of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity and biological function by tyrphostins. Endocrinology. 1997;138:1427–33. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.4.5092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valsecchi ME, McDonald M, Brody JB, Hyslop T, Freydin B, Yeo CJ, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor and insulinlike growth factor 1 receptor expression predict poor survival in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hakam A, Fang Q, Karl R, Coppola D. Coexpression of IGF-1R and c-Src proteins in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1972–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1026122421369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bergmann U, Funatomi H, Yokoyama M, Beger HG, Korc M. Insulin-like growth factor I overexpression in human pancreatic cancer: evidence for autocrine and paracrine roles. Cancer research. 1995;55:2007–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zha J, Lackner MR. Targeting the insulin-like growth factor receptor-1R pathway for cancer therapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:2512–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kurzrock R, Patnaik A, Aisner J, Warren T, Leong S, Benjamin R, et al. A phase I study of weekly R1507, a human monoclonal antibody insulin-like growth factor-I receptor antagonist, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2010;16:2458–65. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez-Calderero I, Sanchez Chavez E, Garcia-Carbonero R. The insulin-like growth factor pathway as a target for cancer therapy. Clin Transl Oncol. 2010;12:326–38. doi: 10.1007/s12094-010-0514-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ebi H, Corcoran RB, Singh A, Chen Z, Song Y, Lifshits E, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinases exert dominant control over PI3K signaling in human KRAS mutant colorectal cancers. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:4311–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI57909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corcoran RB, Ebi H, Turke AB, Coffee EM, Nishino M, Cogdill AP, et al. EGFR-mediated re-activation of MAPK signaling contributes to insensitivity of BRAF mutant colorectal cancers to RAF inhibition with vemurafenib. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:227–35. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nazarian R, Shi H, Wang Q, Kong X, Koya RC, Lee H, et al. Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation. Nature. 2010;468:973–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prahallad A, Sun C, Huang S, Di Nicolantonio F, Salazar R, Zecchin D, et al. Unresponsiveness of colon cancer to BRAF(V600E) inhibition through feedback activation of EGFR. Nature. 2012;483:100–3. doi: 10.1038/nature10868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Villanueva J, Vultur A, Lee JT, Somasundaram R, Fukunaga-Kalabis M, Cipolla AK, et al. Acquired resistance to BRAF inhibitors mediated by a RAF kinase switch in melanoma can be overcome by cotargeting MEK and IGF-1R/PI3K. Cancer cell. 2010;18:683–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.