Abstract

Context:

We report the presence of substantial concentrations of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 in two patients and a third patient with 3-epi-25(OH)D2.

Patients:

The first patient, a 66-year-old female receiving cholecalciferol 4000 IU daily was originally found to have 53 ng/mL of 25(OH)D3 and almost an equal amount of 3-epi-25(OH)D3. Subsequently, the patient had four additional samples, each of which has similar levels of both 25(OH)D3 and 3-epi-25(OH)D3. The second patient, a 7-year-old male receiving cholecalciferol 1000 IU daily, had a 25(OH)D3 concentration of 37 ng/mL and 3-epi-25(OH)D3 of approximately 10 ng/mL. The third and most intriguing patient, a 55-year-old female was receiving ergocalciferol 50 000 IU twice weekly for approximately 3 months, at which time her serum 25(OH)D2 was 64 ng/mL and her 3-epi-25(OH)D2 was approximately 32 ng/mL. This patient's physician changed her vitamin D therapy to cholecalciferol 1000 IU daily, discontinuing ergocalciferol, and a second specimen was collected 5 months later. Analysis of this last specimen found both 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 at concentrations of 12 and 24 ng/mL respectively, plus corresponding 3-epimer peaks for both 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 observed chromatographically.

Conclusion:

The presence of a substantial concentration of 3-epi-25(OH)D in these three patients documents that one cannot assume 3-epi is a trivial metabolite of 25(OH)D for all patients. In addition, the appearance of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 when the last patient changed her vitamin D supplementation from ergocalciferol to cholecalciferol demonstrates that the 3-epimer is probably an endogenous metabolite of 25(OH)D in humans.

Epimers are stereoisomers differing only in the configuration at one chiral center of a molecule. As an example, for 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], the 3-epimer differs only at the 3 position where the hydroxyl group is in the β orientation rather than the α orientation (1). It is well documented that the 3-epimer of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [3-epi-25(OH)D3] is present in serum of children and adults (2–5). Although higher concentrations have been observed in neonates (2), 3-epi-25(OH)D3 has been reported to be present in adults and children (>1 y of age) at 3–5% of the respective 25(OH)D3 concentrations (3). Thus, the 3-epimer is generally considered a minor metabolite of 25(OH)D3. Nonetheless, because some chromatographic 25(OH)D measurement approaches include the 3-epimer whereas others do not, the presence of this molecule may add some “noise” to the “total 25(OH)D” measurement (1). Importantly, the 3-epimer of 25(OH)D3 appears to possess at least some of the calcemic and nonclassical effects of vitamin D (1, 6). Thus, whether it should be included in the measurement of “25(OH)D” remains to be defined. In this regard, the precise in vivo function(s) of 3-epi-25(OH)D remain to be clarified. Moreover, there remains some doubt as to the source of 3-epi-25(OH)D3, ie, exogenous intake or endogenous production.

The following case reports identify three individuals in whom substantial circulating concentrations of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 were observed, thus documenting the 3-epimer as a major metabolite. Moreover, in one patient a substantial amount of 3-epi-25(OH)D2 was observed while receiving ergocalciferol, and subsequently this patient developed substantial amounts of 3-epi-25(OH)D3 after transition to cholecalciferol supplementation. Thus, this is the first documentation of endogenous production of both 3-epi-25(OH)D2 and 3-epi-25(OH)D3.

Patients and Methods

These cases were identified at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Laboratory (UWHCL) through routine monitoring of patient chromatograms. All patients had 25(OH)D ordered by a healthcare provider as part of their clinical care. At UWHCL, 25(OH)D analyses are routinely performed using HPLC with UV detection (HPLC-UV) (7). The University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board has deemed this report exempt from review.

Results

Patient 1

A 66-year-old Caucasian woman with multiple sclerosis was taking two over-the-counter cholecalciferol (2000 U/tablet) tablets daily. The UWHCL received specimens for 25(OH)D analysis; these results are noted in Table 1.

Table 1.

25(OH)D Results

| 25(OH)D3 | 25(OH)D2 | Total 25(OH)D | Estimated 3-Epi-25(OH)D3 | Estimated 3-Epi-25(OH)D2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | |||||

| September 2010 | 53 | <5 | 53 | 50 | Trace |

| April 2011 | 39 | <5 | 39 | 40 | Trace |

| July 2011 | 42 | <5 | 42 | 40 | Trace |

| November 2012 | 52 | <5 | 52 | 48 | Trace |

| July 2013 | 53 | <5 | 53 | 50 | Trace |

| Patient 2 | |||||

| October 2008 | 36 | <5 | 36 | 9 | ND |

| January 2010 | 32 | <5 | 32 | 8 | ND |

| May 2013 | 37 | <5 | 37 | 9 | ND |

| Patient 3 | |||||

| March 2008 | 16 | <5 | 16 | a | a |

| August 2011 | 11 | <5 | 11 | a | a |

| November 2012 | <5 | 64 | 64 | Trace | 32 |

| May 2013 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 6 | 12 |

Abbreviation: ND, not detected. All results are reported in nanograms per milliliter. “Total 25(OH)D” does not include 3-epi-25(OH)D.

Specimen not evaluated by LC-MS/MS.

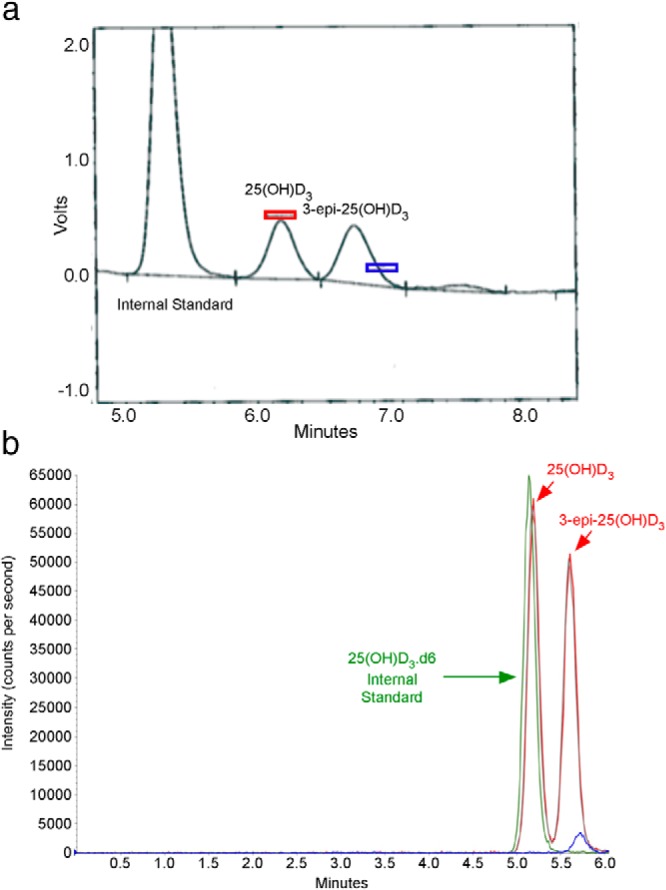

In this patient's initial specimen (September 2010) the HPLC-UV assay detected a peak that migrated after the 25(OH)D3 peak but before the retention window for 25(OH)D2 (Figure 1A). In our laboratory, this peak has historically been associated with 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (3). To verify that this peak was the 3-epimer, this specimen was re-extracted and analyzed by HPLC-tandem mass spectroscopy (HPLC-MS/MS) using positive ion detection in atmospheric pressure chemical ionization mode. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) ions used to identify 25(OH)D3 (Table 2) were identical to the MRM observed with the second peak (Figure 2), thus demonstrating that this peak represented the identical molecular weight, consistent with 3-epi-25(OH)D. As further validation, this second peak has the same retention time as the 3-epi-25(OH)D3 peak observed in the NIST 972 human serum reference material—vial 4 (for methodology and chromatograms, see supplemental data, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org). In this patient, four subsequent serum specimens were collected for 25(OH)D analysis over a 3-year period. In all of these specimens, a second peak consistent with 3-epi-25(OH)D3 and of approximately equal value to the 25(OH)D3 was observed. Thus, this patient had five specimens collected over 3 plus years, and each specimen had 3-epi-25(OH)D3 concentrations very similar to the concentration of 25(OH)D3.

Figure 1.

A, HPLC-UV chromatogram (absorbance 275 nm) showing peaks detected for the internal standard (lauraphenone), 25(OH)D3, and 3-epi-25(OH)D3 for patient 1. Note the horizontal bars on the chromatogram, which represent the expected retention time windows for 25(OH)D3 (red rectangle) and 25(OH)D2 (blue rectangle), respectively. B, HPLC-MS/MS chromatogram obtained for the same specimen. Three major peaks noted in this chromatogram are the internal standard [25(OH)D3.d6] in green; 25(OH)D3, which coelutes with the internal standard; and 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (second red peak). The MRM ions for 25(OH)D3 (red peaks) are 383.3/211.2, for hexadeuterated 25(OH)D3 (green peak) are 389.3/211.1, and for 25(OH)D2 (small blue peak) are 395.3/209.1.

Table 2.

MRM Ions for Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization HPLC-MS/MS of 25(OH)D

| 25(OH)D | MRM |

|---|---|

| 25(OH)D3 | 383.3/211.2 |

| 25(OH)D3.d6 | 389.3/211.1 |

| 25(OH)D2 | 395.3/209.1 |

Abbreviation: 25(OH)D3.d6, hexadeuterated 25(OH)D3 internal standard.

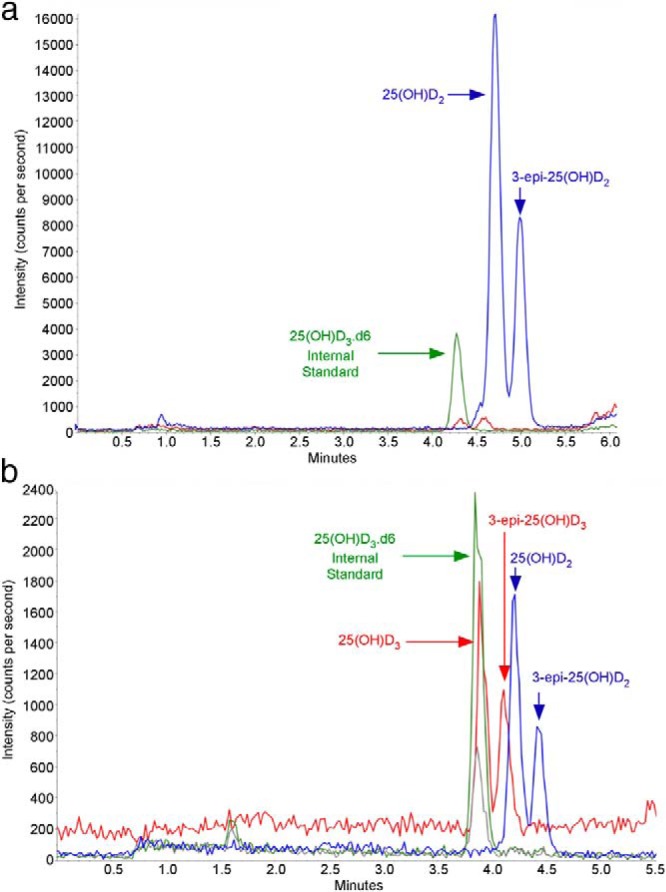

Figure 2.

A, HPLC-MS/MS chromatogram for patient 3, during period when she was receiving high-dose ergocalciferol. The prominent peaks (blue) are 25(OH)D2 and the later-eluting 3-epi-25(OH)D2. Note the very minor peaks (red) for 25(OH)D3 and 3-epi-25(OH)D3. B, HPLC-MS/MS chromatogram for patient 3, 5 months after discontinuing ergocalciferol treatment. This chromatogram shows the presence of 25(OH)D3, 3-epi-25(OH)D3 (red arrows), 25(OH)D2, and 3-epi-25(OH)D2, (blue arrows). The MRM ions for 25(OH)D3 (red peaks) are 383.3/211.2, for hexadeuterated 25(OH)D3 (green peak), are 389.3/211.1, and for 25(OH)D2 (blue peaks) are 395.3/209.1.

Patient 2

A 7-year-old Caucasian male with multiple medical comorbidities had been receiving cholecalciferol (1000 IU) daily for an unspecified time period. UWHCL received several samples for 25(OH)D analysis (Table 1).

The HPLC-UV chromatogram for this patient's May 2013 specimen gave the expected 25(OH)D3 peak along with a late-eluting peak consistent with 3-epi-25(OH)D3 as noted in Figure 1A (chromatogram of patient 2 not shown). Re-extraction of the May 2013 specimen with subsequent analysis by HPLC-MS/MS confirmed that the two peaks observed on HPLC-UV had the same MRM. Therefore, the first peak is 25(OH)D3, and the second peak is 3-epi-25(OH)D3, similar to that noted in Figure 1B. HPLC-MS/MS analysis estimated the concentration of the two peaks at 40 and 10 ng/mL, respectively. Therefore, this patient's 3-epi-25(OH)D3 was approximately 25% of the 25(OH)D3, a high percentage even for a child.

Patient 3

This patient was a 55-year-old Caucasian female with combined hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and atherosclerotic vascular disease. UWHCL received several samples for 25(OH)D analysis (Table 1).

Beginning in August 2011, she was treated with ergocalciferol 50 000 IU twice weekly. HPLC-UV analysis in November 2012 observed a 25(OH)D2 of 64 ng/mL, but the chromatogram also had a second substantial peak that eluted after the 25(OH)D2 (Figure 2A). This specimen was re-extracted and analyzed by HPLC-MS/MS, which determined that the second peak responded to the same MRM, thus consistent with 25(OH)D2 (Figure 2B). Because this second peak has the same MRM as 25(OH)D2 and has a slightly longer elution time, the peak is 3-epi-25(OH)D2. The concentration of the second peak was estimated to be approximately 50% of 25(OH)D2, or approximately 32 ng/mL.

In December 2012, the patient's primary care physician had the patient discontinue ergocalciferol and switch to over-the-counter cholecalciferol 1000 IU once daily. A follow-up specimen was collected May 2013 for 25(OH)D measurement, at which time HPLC-UV analysis gave values for 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 noted in Table 1. However, the chromatogram demonstrated not only the presence of a late-eluting peak [3-epi-25(OH)D2] after 25(OH)D2, as observed in the November 2012 specimen, but also a late-eluting peak [3-epi-25(OH)D2] after 25(OH)D3. This May 2013 specimen was re-extracted and analyzed by HPLC-MS/MS, and both 25(OH)D2 and 25(OH)D3 were present. In addition, LC-MS/MS analysis also showed the presence of two late-eluting peaks after both 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 (Figure 2B). The late-eluting peak after 25(OH)D3 is consistent with 3-epi-25(OH)D3. Moreover, the corresponding late-eluting peak, after 25(OH)D2, which shares the same MRM with 25(OH)D2, is identified as 3-epi-25(OH)D2. As validation, 3-epi-25(OH)D2 obtained from a commercial source (Toronto Research Chemicals Inc) has the same retention time as the late-eluting peak after 25(OH)D2. To further clarify the identity of 3-epi-25(OH)D2, 24(OH)D2 was considered as a potential metabolite. An authentic sample of 24(OH)D2 was obtained as a gift from Ronald Horst (Heartland Assays, LLC). It was produced from biological sources and identified as described Koszewski et al (8). Analysis of this material demonstrated that 24(OH)D2 appears as a shoulder on the leading edge of the 25(OH)D2 peak in our chromatographic system and is well separated from 3-epi-25(OH)D2 (see Supplemental Data).

Discussion

We report three patients with substantial amounts of 3-epi-25(OH)D. Upon review of the electronic medical records, it was not apparent that these patients had any clinical issue/illness in common, with the exception that all three have an unusually high percentage of 3-epi-25(OH)D relative to their total 25(OH)D. Moreover, patient 3 had a peak on the chromatogram that is consistent with 3-epi-25(OH)D2, a phenomenon that has not been previously reported in human serum. Importantly, when vitamin D supplementation of patient 3 was changed from ergocalciferol to cholecalciferol, a subsequent serum sample contained a substantial amount of 3-epi-25(OH)D3. Together, this information is consistent with the endogenous production of both 3-epi-25(OH)D2 and 3-epi-25(OH)D3. These results are highly suggestive that this patient's 3-epimer levels are endogenous. As such, this is the first report documenting that the 3-epimer of both 25(OH)D3 and 25(OH)D2 is produced endogenously.

It has been suggested that C-3 epimerization is a common metabolic pathway for vitamin D metabolites and that the epimerase enzyme(s) responsible for such production are located in microsomes and differ from the cytochrome P450 system (9, 10). It should be recognized that the work documenting epimerase activity has occurred using immortalized cell lines in vitro (6, 10–12). Nonetheless, it has been speculated that the epimerase occurs in extrarenal tissues and utilizes enzymes distinct from the classic hepatic system involved in vitamin D metabolism (1). It is to be expected that between-individual differences in enzyme activity (likely genetic) would exist, with some individuals having greater amounts of 3-epi-25(OH)D as observed in these three patients. It seems probable that the three cases reported here represent patients that have an epimerase activity that is considerably higher than that found in most individuals.

The clinical importance of 3-epi-25(OH)D remains to be clarified. However, the 3-epimer form of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 does possess biological activity and appears to act via the vitamin D receptor (11, 13–16). Thus, future total 25(OH)D measurements would benefit by inclusion of the 3-epi-25(OH)D contribution into the “total 25(OH)D” result, whether measured via immunoassay or chromatographic methods.

This report describes three patients with increased levels of 3-epi-25(OH)D that have been identified within a single hospital clinical laboratory over the past 5 years. Although a comprehensive quality assurance program exists at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics Laboratory, there is no formal mechanism in place mandating the technologists to flag specimens at a given level of 3-epi-25(OH)D. As such, it is probable that other patients with similarly high values of 3-epi-25(OH)D have been missed, thereby precluding estimation of the prevalence of such high concentrations. Nonetheless, because our laboratory has measured approximately 100 000 unique patient specimens over the past 5 years, we can conservatively estimate that a minimum of 30 patients per million have similarly elevated 3-epi-25(OH)D values. Systematic evaluation of larger datasets to delineate the prevalence of such high levels is indicated.

How to optimally measure 25(OH)D in the clinical and research laboratory remains an area of intense interest and ongoing standardization efforts (17–21). In this regard, serum specimens that have substantial amounts of the 3-epimer, if this is included in the total 25(OH)D result, could lead to misclassification of a given patient's vitamin D status. Although chromatography-based methodologies have been considered by some as the “gold standard” for 25(OH)D measurement (22), some immunoassays are reported to have no cross-reactivity with the 3-epimer and report only total 25(OH)D (23). In contrast, it has been noted that some chromatography-based 25(OH)D assays fail to separate the 3-epimer from 25(OH)D (24). Thus, either methodology could be judged as having either a positive or negative impact on the reported total 25(OH)D result by missing, or alternatively, including the 3-epimer.

In conclusion, we report three patients with substantial levels of 3-epi-25(OH)D, including one in whom endogenous production of both 3-epi-25(OH)D3 and 3-epi-25(OH)D2 is demonstrated. Such between-individual variation in the amount of 3-epi-25(OH)D, coupled with variability of 3-epimer detection by the different assay methodologies, confounds current efforts to accurately measure total 25(OH)D and impairs the ability to define vitamin D status. Future research is required to define the biological importance of the 3-epimer, and consensus must be reached regarding whether to include the 3-epimer value in the “total 25(OH)D” result.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (National Institutes of Health) Comprehensive Centers of Excellence, 1P60/RO1 MD 003428-01.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- 3-epi-25(OH)D3

- 3-epimer of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3

- HPLC-MS/MS

- HPLC-tandem mass spectroscopy

- MRM

- multiple reaction monitoring

- 25(OH)D

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

References

- 1. Bailey D, Veljkovic K, Yazdanpanah M, Adeli K. Analytical measurement and clinical relevance of vitamin D(3) C3-epimer. Clin Biochem. 2013;46:190–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Singh RJ, Taylor RL, Reddy GS, Grebe SK. C-3 epimers can account for a significant proportion of total circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D in infants, complicating accurate measurement and interpretation of vitamin D status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3055–3061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lensmeyer G, Poquette M, Wiebe D, Binkley N. The C-3 epimer of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3) is present in adult serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strathmann FG, Sadilkova K, Laha TJ, et al. 3-Epi-25 hydroxyvitamin D concentrations are not correlated with age in a cohort of infants and adults. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:203–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Granado-Lorencio F, Blanco-Navarro I, Pérez-Sacristán B, Donoso-Navarro E, Silvestre-Mardomingo R. Serum levels of 3-epi-25-OH-D3 during hypervitaminosis D in clinical practice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E2266—E2270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Molnár F, Sigüeiro R, Sato Y, et al. 1α,25(OH)2–3-epi-vitamin D3, a natural physiological metabolite of vitamin D3: its synthesis, biological activity and crystal structure with its receptor. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lensmeyer GL, Wiebe DA, Binkley N, Drezner MK. HPLC method for 25-hydroxyvitamin D measurement: comparison with contemporary assays. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1120–1126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Koszewski NJ, Reinhardt TA, Beitz DC, et al. Use of Fourier transform 1H NMR in the identification of vitamin D2 metabolites. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kamao M, Hatakeyama S, Sakaki T, et al. Measurement and characterization of C-3 epimerization activity toward vitamin D3. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;436:196–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kamao M, Tatematsu S, Hatakeyama S, et al. C-3 Epimerization of vitamin D3 metabolites and further metabolism of C-3 epimers: 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 is metabolized to 3-epi-25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and subsequently metabolized through C-1α or C-24 hydroxylation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:15897–15907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown AJ, Ritter C, Slatopolsky E, Muralidharan KR, Okamura WH, Reddy GS. 1α,25-dihydroxy-3-epi-vitamin D3, a natural metabolite of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, is a potent suppressor of parathyroid hormone secretion. J Cell Biochem. 1999;73:106–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siu-Caldera ML, Sekimoto H, Weiskopf A, et al. Production of 1α,25-dihydroxy-3-epi-vitamin D3 in two rat osteosarcoma cell lines (UMR 106 and ROS 17/2.8): existence of the C-3 epimerization pathway in ROS 17/2.8 cells in which the C-24 oxidation pathway is not expressed. Bone. 1999;24:457–463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brown AJ, Ritter CS, Weiskopf AS, et al. Isolation and identification of 1α-hydroxy-3-epi-vitamin D3, a potent suppressor of parathyroid hormone secretion. J Cell Biochem. 2005;96:569–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rehan VK, Torday JS, Peleg S, et al. 1α,25-dihydroxy-3-epi-vitamin D3, a natural metabolite of 1α,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3: production and biological activity studies in pulmonary alveolar type II cells. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;76:46–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kadiyala S, Nagaba S, Takeuchi K, et al. Metabolites and analogs of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3): evaluation of actions in bone. Steroids. 2001;66:347–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Messerlian S, Gao X, St Arnaud R. The 3-epi- and 24-oxo-derivatives of 1α,25 dihydroxyvitamin D(3) stimulate transcription through the vitamin D receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2000;72:29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sempos CT, Vesper HW, Phinney KW, Thienpont LM, Coates PM. Vitamin D status as an international issue: National surveys and the problem of standardization. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2012;243:32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Phinney KW. Development of a standard reference material for vitamin D in serum. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:511S–512S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tai SS, Bedner M, Phinney KW. Development of a candidate reference measurement procedure for the determination of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 in human serum using isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2010;82:1942–1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carter GD, Jones JC. Use of a common standard improves the performance of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methods for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin-D. Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46:79–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thienpont LM, Stepman HC, Vesper HW. Standardization of measurements of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 and D2. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2012;243:41–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de la Hunty A, Wallace AM, Gibson S, Viljakainen H, Lamberg-Allardt C, Ashwell M. UK Food Standards Agency Workshop Consensus Report: the choice of method for measuring 25-hydroxyvitamin D to estimate vitamin D status for the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:612–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carter GD. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D: a difficult analyte. Clin Chem. 2012;58:486–488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Farrell CJ, Martin S, McWhinney B, Straub I, Williams P, Herrmann M. State-of-the-art vitamin D assays: a comparison of automated immunoassays with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry methods. Clin Chem. 2012;58:531–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]