Abstract

Context:

The IL-1 family plays important roles in normal physiology and mediates inflammation. The actions of IL-1 are modulated by multiple IL-1 receptor antagonists (IL-1RA), including intracellular and secreted forms. IL-1 has been implicated in autoimmunity, such as that occurring in Graves' disease (GD) and its inflammatory orbital manifestation, thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO). We have previously reported that CD34+ fibrocytes, monocyte-lineage bone marrow-derived cells, express functional TSH receptor, the central antigen in GD. When activated by TSH, they produce IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α. Moreover, they infiltrate the orbit in TAO in which they transition into CD34+ fibroblasts and comprise a population of orbital fibroblasts (OFs). Little is known currently about any relationship between TSH, TSH receptor, and the IL-1 pathway.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to determine whether TSH regulates IL-1RA in fibrocytes and OFs.

Design/Setting/Participants:

Fibrocytes and OFs were collected and analyzed from healthy individuals and those with GD in an academic clinical practice.

Main Outcome Measures:

Real-time PCR, Western blot analysis, reporter gene assays, and cell transfections were performed.

Results:

TSH induces the expression of IL-1RA in fibrocytes and GD-OFs. The patterns of induction diverge quantitatively and qualitatively in the two cell types. This results from relatively small effects on gene transcription-related events but a greater influence on secreted IL-1RA and intracellular IL-1RA mRNA stabilities. These actions of TSH are dependent on the intermediate induction of IL-1α and IL-1β.

Conclusions:

Our findings for the first time directly link activities of the TSH and IL-1 pathways. Furthermore, they identify novel molecular interactions that could be targeted as therapy for TAO.

The IL-1 family comprises multiple members, including the isoforms of IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), which modulates the activities of IL-1α and IL-1β (1–3). These related proteins are synthesized in response to a diverse set of factors that vary with cell-type (3). IL-1RA competitively binds the IL-1 receptor and attenuates downstream signaling. Four different IL-1RA forms have been identified, including the secreted isoform (sIL-1RA) and three intracellular proteins (icIL-1RA) (1). Transcripts encoding sIL-1RA and icIL-1RA differ only in the sequence extending from +4 nt to +63 nt and encoding a 21-amino acid peptide present in sIL-1RA. Two distinct gene promoters drive the expression of these proteins (4). Balance between the activities of IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-1RA determine the amplitude and duration of responses mediated through the IL-1 receptor (5–7).

The TSH receptor (TSHR), a G protein-coupled surface protein expressed on thyroid epithelial cells, mediates actions of TSH on target cells (8). TSHR is the central autoantigen in Graves' disease (GD) in which thyroid-stimulating immunuglobulins bind to the protein and provoke hyperthyroidism (8). In addition to the thyroid epithelium, relatively low levels of TSHR have been detected in several connective tissue depots, including orbital fat (9, 10), and on fibroblasts derived from these tissues (11). CD34+ fibrocytes, monocyte-derived progenitor cells resembling fibroblasts, infiltrate injured tissues undergoing remodeling in models of fibrosis (12). In earlier studies, they were found unexpectedly to express high levels of functional TSHR and thyroglobulin (13, 14). When treated with TSH or an activating monoclonal antibody, they produce high levels of IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα (13). In GD, the orbital connective tissues become inflamed, expand, and undergo remodeling in a process known as thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy (TAO) (15). CD34+ fibrocytes infiltrate the orbit in TAO (13, 16). A subset of GD orbital fibroblasts (GD-OFs) exhibits the CD34+TSHR+CXCR4+collagen 1+ phenotype, strongly suggesting that they derive from circulating fibrocytes.

Vanishingly little is currently known about the influence of TSH on IL-1 family members. We have recently reported that fibrocytes from patients with GD express IL-1RA in response to IL-1β in a pattern diverging from that in GD-OFs (17). Here we demonstrate that TSH is also an inducer of icIL-1RA in fibrocytes and GD-OFs. In contrast, TSH induces sIL-1RA in fibrocytes, but this effect is absent in GD-OFs. Activities of the respective gene promoters were unaffected by TSH, whereas RNA polymerase II recruitment to the two gene promoters was modestly influenced. TSH stabilizes IL-1RA mRNAs in isoform-specific patterns that diverged with cell type. The effects of TSH on IL-1RA expression depend on the intermediate induction of IL-1α and IL-1β. Our results suggest a potential role for TSH as a regulator of IL-1 and IL-1RA. Furthermore, it is possible that the orbital inflammation occurring in TAO may result from the activities of TSHR displayed on fibrocytes and GD-OFs and thus might be therapeutically targeted.

Materials and Methods

Materials

DMEM (catalog number 11965-092), fetal bovine serum (FBS; catalog number 16000-044), and recombinant human IL-1β (catalog number PHC0815) were from Life Technology. 5,6-Dichlorobenzimidazole (DRB) came from Cayman (catalog number 10010302). Bovine TSH (bTSH) was from Calbiochem (catalog number 609385). Luciferase expression plasmids, psRA-1680Luc containing a 1680-bp fragment of the sIL-1RA gene promoter and picRA-4555Luc containing 4555 bp of the icIL-1RA (18), were generously provided by Dr Cem Gabay (Geneva, Switzerland). ELISA kits for human IL-1RA and IL-1β were from R & D Systems, and a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay kit was from Millipore (catalog number 17-925). Anti-RNA polymerase II (Pol II) antibody (catalog number GAH-111) and quantitative PCR primers for icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA gene promoters were from SABioscience.

Fibroblast and fibrocyte cultivation

Orbital tissue was obtained as surgical waste during orbital decompressions for TAO (n = 9) or from healthy donors (n = 6). Those donors were all euthyroid at the time of participation and were not taking systemic corticosteroids. These activities have been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan. Fibroblasts were cultivated as previously described (19) and were covered with DMEM containing 10% FBS in a 37°C, humidified, 5% CO2 environment and were used between the fifth and 12th passages. The medium was changed every 4 days.

Human fibrocytes were obtained from euthyroid patients with TAO (n = 6) not taking corticosteroids or from healthy donors (n = 30). They were isolated from human peripheral blood by Ficoll density centrifugation as described (20). Typically, 107 peripheral blood mononuclear cells were inoculated into each of six-wells/plate in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. Unattached cells were discarded after 7 days and monolayers were incubated for an additional 7–10 days before use. Greater than 90% of the attached cells displayed a CD45+ CD34+TSHR+CXCR4+ phenotype (13).

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Confluent cultures were shifted to medium with 1% FBS for 16 hours before treatment with bTSH (5 mU/mL) or the test agents indicated. RNA was extracted with Aurum total RNA mini kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories; catalog number 732-6820). Purified RNA was used to generate cDNA by reverse transcription using oligo(deoxythymidine) and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Inc; catalog number 205311). Real-time PCR was performed using iQ SYBR Green supermix(Bio-Rad Laboratories; catalog number 170-8882) on a CFX96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Each sample was analyzed in triplicate with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a reference control. Primer sequences were as follows: icIL-1RA forward, 5′-CTATCAGGCCCTCCCCATGGC-3′, reverse, 5′CAACTAGTTGGTTGTTCCTCC-3′; sIL-1RA forward, 5′-CTGCAGTCACAG AATGGAAATC-3′, reverse, 5′-CAACTAGTT GGTTGTTCCTCC-3′; IL-6 forward, 5′-CAGGAGCCCAGTATAACT-3′, reverse, 5′-GAATGCCCATGCTACATTT-3′; and GAPDH forward, 5′-TTGCCATCAATGACCCCTTCA-3′, reverse, 5′-CGCCCCACTTGATTTTGGA-3′. Reactions were performed at 95°C for 5 minutes, 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 seconds, and 60°C for 30 seconds.

IL-1RA mRNA stability assay

Confluent cultures were shifted to medium with 1% FBS for 16 hours and were then pretreated with bTSH for 12 hours. DRB (50 μM) was added without or with bTSH at time 0 (see Figure 4A) and RNA harvested at the times indicated. Samples were subjected to quantitative RT-PCR. The t½ values were calculated using the comparative critical threshold method. Data were graphed as a best-fit line.

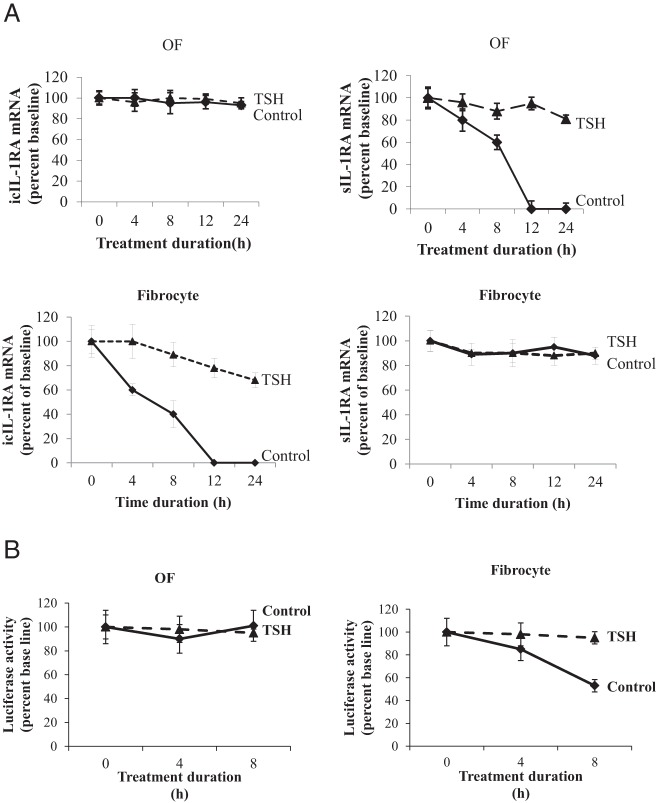

Figure 4.

bTSH enhances icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA mRNA stability in OFs and fibrocytes in a isoform- and cell-specific manner. A, bTSH (5 mIU/mL) was added to the medium of confluent cultures for 12 hours, cell layers were rinsed, and fresh medium containing DRB (50 μM) without or with bTSH was added. RNA was harvested at times indicated along the abscissa and subjected to real-time RT-PCR. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three independent replicates. B, Eighty percent confluent cultures were transfected with a chimeric luciferase reporter fused to a fragment of the IL-1RA 3′UTR. Renilla luciferase-encoding plasmid phRL-TK was cotransfected as an efficiency control. TSH (5 mIU/mL) was added for 8 hours, cell layers were rinsed, and fresh medium containing DRB (50 μM) was added without or with bTSH. Monolayers were extracted at times indicated and analyzed for luciferase activities. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three replicates. Experiments were performed three times.

Transient transfection and luciferase reporter activity assays

For IL-RA gene promoter studies, cells were transiently transfected with a luciferase reporter fused to a 4555-nt fragment of the icIL-1RA promoter, a 1680-nt fragment of the sIL-1RA promoter, or an empty control luciferase vector. Renilla luciferase-encoding plasmid phRL-TK was cotransfected with the promoter reporters as a control. After 24 hours, the cell monolayers were treated with nothing or TSH (5 mIU/mL) for 2 hours and luciferase activities were determined. The 1195-bp IL-1RA 3′untranslated region (UTR) was amplified by PCR from the icIL-1RA cDNA clone (Openbiosystem) and subcloned into a pGL3-control vector. The resulting construct as well as psRA-1680Luc and picRA-4555Luc plasmids were transfected into 80% confluent orbital fibroblasts (OFs) using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) as described (14) and subjected to dual-luciferase reporter assay (Promega). All transfection assays were performed in triplicate. Lumicount data were normalized to their Renilla transfection controls. Fibrocyte transfections utilized Amaxa Nucleofection Technology (Amaxa) as described (14) using program U23.

Quantification of IL-1 and IL-1RA

Samples were subjected to ELISA in triplicate.

RNA Pol II ChIP assay

Assessing recruitment of Pol II to the IL-1RA gene promoters was performed by the method of Bittencourt and Auboeuf (21). Briefly, cells were cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes and then washed twice with cold PBS. Cell pellets were centrifuged at 2000 rpm and resuspended in lysis buffer containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.1). Chromatin was sonicated to generate an average fragment size from 500 to 1000 bp. For each immunoprecipitation, anti-Pol II antibody (2 μg) was added to chromatin suspension (200 μL) and dilution buffer (1800 μL). These were subjected to agitation overnight at 4°C. Protein-A-agarose beads (60 μL) were added to each reaction for 1 hour at 4°C, pelleted, and washed sequentially with low, high, and then LiCl immune complex wash and Tris/EDTA buffers. Precipitated beads were rinsed with elution buffer and pooled samples were heated to 65°C for 4 hours to reverse protein-DNA cross-linking. DNA was phenol extracted, ethanol precipitated, and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR.

Nuclear run-on assay

Confluent orbital fibroblast monolayers were shifted for 12 hours to medium containing 1% FBS before being stimulated with or without TSH for 2 hours. Monolayers were then harvested, cell nuclei isolated, and nuclear run-on reactions performed as described previously (22).

Statistics

Significance was determined with a two-tailed Student's t test. All experiments were conducted at least three times.

Results

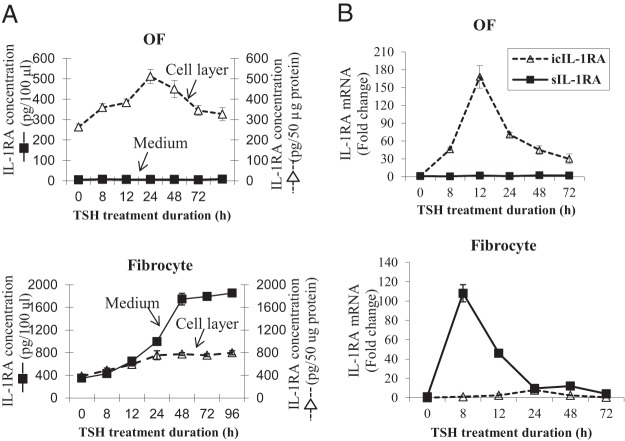

bTSH up-regulates cell-associated and released IL-1RA in OFs and fibrocytes through regulation of IL-1RA mRNA levels

IL-1β can induce divergent patterns of IL-1RA expression in OFs and fibrocytes (17). To determine whether TSH could also up-regulate IL-1RA, OFs and fibrocytes were treated with nothing or bTSH (5 mIU/mL) for graded intervals. IL-1RA protein was quantified in cell lysates and medium using a specific ELISA (Figure 1A). The agent provoked a time-dependent 2-fold increase in the cell-layer-associated cytokine in OFs after 24 hours. Low-medium levels of IL-1RA were unaffected by bTSH. In contrast, basal medium levels of IL-1RA protein were considerably higher in fibrocytes, and the release of the protein was dramatically greater as a function of TSH treatment. After 48 hours, levels plateaued at 4-fold above baseline and were maintained for the duration of the study (96 h). Figure 1B contains the time course of bTSH effects on steady-state mRNA encoding icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA. The patterns of response to TSH regarding icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA in the two different cell types were very different. sIL-1RA was not induced in OFs but was dramatically up-regulated in fibrocytes. In contrast, icIL-1RA was induced in OFs, but bTSH had less impact on this isoform.

Figure 1.

Induction time course of IL-1RA protein and mRNA expression by bTSH in OFs and fibrocytes. Cells were cultured in six-well plates and incubated without or with bTSH (5 mIU/mL) for the intervals as indicated along the abscissas. A, Media and cell lysates were collected and analyzed by a specific ELISA. B, RNA was harvested and analyzed by real-time RT-PCR for icIL-1RA (dotted lines) and sIL-1RA (solid lines). Data are expressed as mean ± SD of triplicates from three independent experiments.

Divergent patterns of icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA mRNA induction by TSH in OFs and fibrocytes

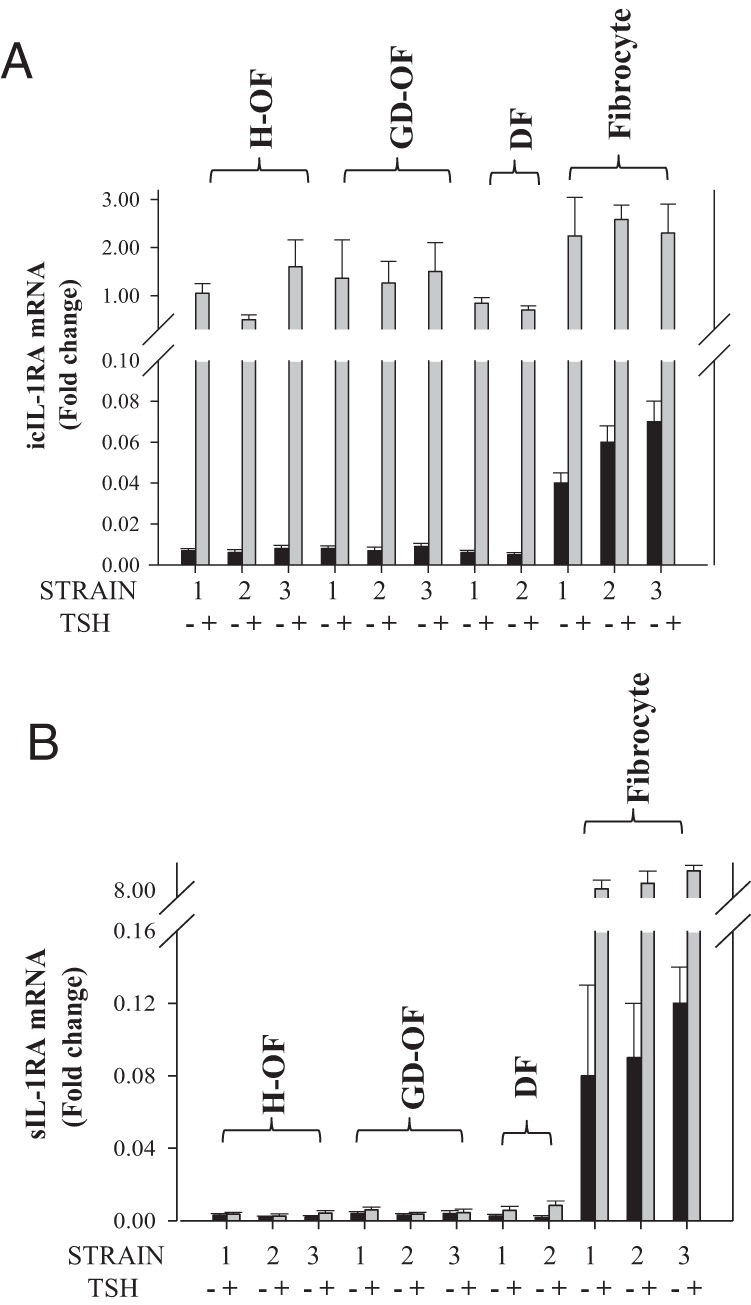

Regulation of IL-1RA isoforms diverges with regard to cell type. Steady-state icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA mRNAs were compared under basal conditions and in the presence of TSH in multiple strains of OFs and fibrocytes. As shown in Figure 2A, the levels of icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA transcripts were at the limits of detectability in untreated OFs but considerably higher in fibrocytes. When treated for 12 hours with TSH, icIL-1RA mRNA levels were dramatically increased in both cell types. In contrast, basal sIL-1RA was essentially undetectable in OFs, and bTSH failed to induce its expression (Figure 2B). By comparison, this transcript was relatively abundant in untreated fibrocytes and was substantially induced by bTSH.

Figure 2.

Induction of IL-1RA mRNAs by TSH in several strains of OFs from healthy (H-OF) donors and those with Graves' disease (GD-OFs) and fibrocytes. Three strains of each cell type were treated with bTSH for 12 hours, RNA was harvested, and analyzed for icIL-1RA (A) and sIL-1RA mRNA (B) by real-time RT-PCR. Data are expressed as means ± SD of three independent replicates.

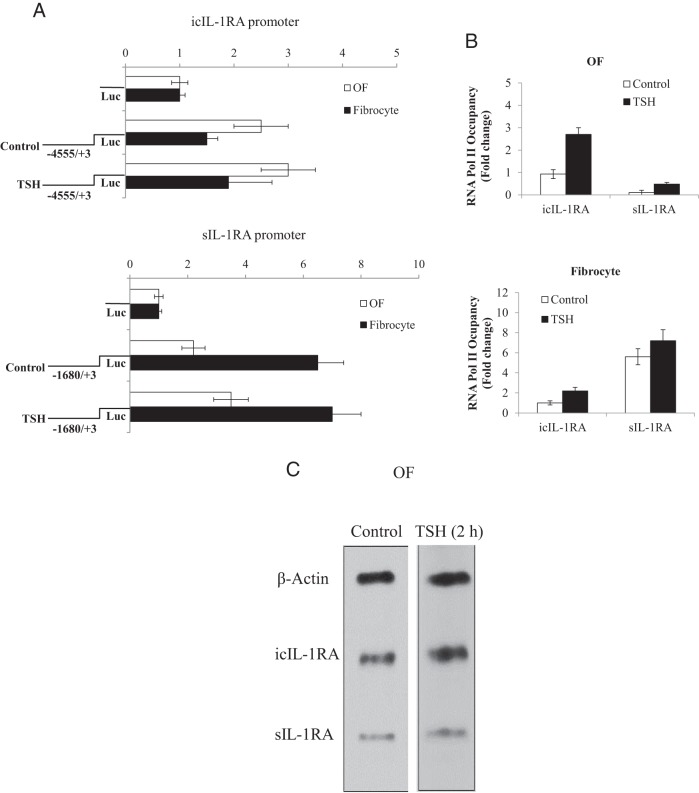

Induction of IL-1RA by bTSH cannot be attributed to enhanced gene transcription

We next determined whether the bTSH actions were a consequence of enhanced gene promoter activity. A fragment of the sIL-1RA gene promoter containing 1680 bp of the 5′-flanking DNA and a 4555-bp fragment of icIL-1RA were fused to luciferase reporter genes and designated psRA-1680Luc and picRA-4555Luc, respectively. These were transiently transfected into cells. As Figure 3A demonstrates, activity of neither promoter was influenced substantially by bTSH in either cell type. Basal icIL-1RA promoter activity appears to be higher in OFs, whereas the sIL-1RA promoter construct was more active in fibrocytes. We next determined the occupancy of Pol II sites in the two gene promoter/enhancer regions. Basal Pol II occupancy of the icIL-1RA promoter was approximately 4-fold higher in OFs compared with sIL-1RA (Figure 3B). In contrast, a higher basal occupancy of the sIL-1RA promoter sites was evident in fibrocytes than that observed in OFs. bTSH modestly up-regulates Pol II levels in both promoters and in both cell types. These findings suggest divergent basal rates of gene transcription of icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA in OFs and fibrocytes. They also suggest that the impact of bTSH on recruitment to Pol II sites in either promoter is modest. As a more direct assessment of transcription, nuclear run-on assays also demonstrated modest effects of bTSH on both icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA (∼1.2-fold above untreated control) (Figure 3C). Thus, increases in gene transcription cannot account for the dramatic effects of bTSH on IL-1RA expression in OFs or fibrocytes.

Figure 3.

Effects of bTSH on icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA gene promoter activities and gene transcription in OFs and fibrocytes. A, IL-1RA gene promoter/reporter constructs were transfected into cells as described in Materials and Methods. They were then treated with nothing or TSH for 2 hours, harvested, and luciferase activity determined. B, ChIP assays were performed in OFs and fibrocytes as described in Materials and Methods. RNA Pol II occupancy was normalized to that of GAPDH, which served as a positive control. RNA Pol II occupancy was expressed as mean ± SD of fold change of three independent experiments. C, OFs were cultured to confluence in medium containing 10% FBS and then shifted to medium with 1% FBS for 16 hours. bTSH (5 mIU/mL) or nothing (control) was added to medium for 2 hours. Intact nuclei were collected and nuclear run-on assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

bTSH enhances the stability of IL-1RA mRNAs in a cell-type-specific manner

bTSH affects the stabilities of the two IL-1RA transcripts. icIL-1RA mRNA exhibits remarkable stability in OF in the absence or presence of TSH. In contrast, the transcript decays rapidly in untreated fibrocytes (Figure 4A). The mRNA is nearly undetectable after 12 hours. in the absence of bTSH but in its presence icIL-1RA mRNA is partially rescued. Unlike icIL-1RA, sIL-1RA mRNA decays rapidly in OFs but is extremely durable in fibrocytes. bTSH stabilize sIL-1RA mRNA in OFs so that after 24 hours, levels are 80% of those at baseline. The presence of adenylate-uridylate-rich regions in the IL-1RA 3′UTR, shared by both isoforms, implies the potential instability of these two transcripts. To assess the role of IL-1RA 3′UTR in stability, this sequence was cloned, fused to a reporter gene yielding pGL3-Luc-IL-1RA-UTR, and transfected into cultures. Cultures were pretreated with bTSH for 6 hours and DRB was added at time 0 in Figure 4B. Monolayers were then incubated in the absence or presence of bTSH for up to 8 hours and luciferase activity determined. Activity in OFs was stable over the course of the study and was unaffected by bTSH. In contrast, reporter activity in the fibrocytes decayed in the absence of bTSH (60% after 8 h) but was rescued by bTSH. In aggregate, these findings imply that bTSH enhances IL-1RA mRNA levels by modestly increasing gene transcription but exerts substantial enhancement of mRNA stability. Moreover, the stabilities of the two transcripts differ substantially in OFs and fibrocytes. The 3′UTR may play very different roles in determining IL-1RA mRNA stability in the two cell types. Furthermore, the findings suggest that proteins may bind IL-1RA mRNA at the 3′UTR and therefore influence its stability in a TSH-dependent and cell-type-specific manner.

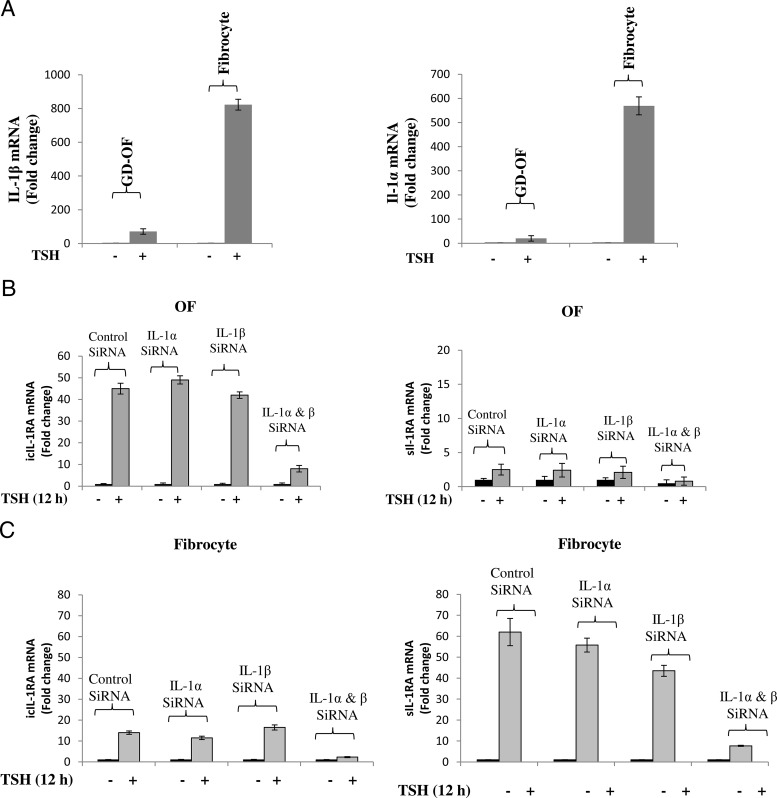

Divergent patterns of induction of IL-1α and IL-1β by TSH

Initial findings that bTSH was a strong and cell-specific inducer of IL-1RA prompted the examination of possible effects on IL-1α and IL-1β. Steady-state levels of both mRNAs were compared in the absence or presence of bTSH in GD-OFs and fibrocytes (Figure 5A). When treated for 12 hours with bTSH, both IL-1β and IL-1α mRNA levels were dramatically increased in fibrocytes. In contrast, OFs were considerably less responsive (Figure 5A) [IL-1β: fibrocytes 823.3 ± 45.3; OFs 71.3 ± 3.8 (mean ± SD, P < .01); IL-1α: fibrocytes 569 ± 39.8; OFs 20 ± 1.5, P < .05]. Differences in the magnitude of IL-1β mRNA induction in the two cell types resulted in similarly dramatic divergence of IL-1β protein (Supplemental Figure 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://jcem.endojournals.org). The question of whether the induction of either was intermediate in the effects of bTSH on IL-1RA was next addressed by knocking down IL-1α and IL-1β with specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Transfecting OFs with either siRNA targeting IL-1α or IL-1β nearly completely attenuated the induction of IL-1α and IL-1β, respectively (Supplemental Figure 2). Knocking down IL-1α together with IL-1β is required to substantially lower levels of both icIL-1RA and sIL-1RA. Similarly, knocking down either IL-1α or IL-1β only modestly attenuated the induction by bTSH of either IL-1RA transcript in fibrocytes. Cotransfection of fibrocytes with both siRNAs was necessary to appreciably reduce the amplitude of the TSH-dependent induction of either IL-1RA isoform. This result suggests that the induction of either IL-1α or IL-1β is necessary for the up-regulation by bTSH of IL-1RA.

Figure 5.

TSH up-regulates IL-1α and IL-1β in OFs and fibrocytes. Knocking these down attenuates the induction of IL-1RA isoforms in a cell-specific manner. A, Cultured GD-OFs and fibrocytes were switched to medium containing 1% FBS for 16 hours. Total RNA was harvested after being stimulated with or without TSH for 12 hours. Expression of IL-1β mRNA and IL-1α mRNA were determined and analyzed by real-time RT-PCR as described under Methods. B and C, Eighty percent confluent cultured cells were transfected with IL-1α siRNA or IL-1β siRNA alone or in combination. After 48 hours, monolayers were treated without or with bTSH for 12 hours. RNA was harvested and subjected to real-time RT-PCR for the amplicons indicated. Data are expressed as mean ± SD of three replicates. Experiments were performed three times.

Discussion

Proximate intersections between host defense and endocrine function could offer substantial survival advantages. These relate to the tight coordination that would result in an organism's ability to execute rapid metabolic responses to adverse environmental signals, such as those emerging from trauma or infection. At the same time, the immune system could mount an inflammatory reaction involving recruitment of immunocompetent cells to the tissues sustaining damage. TSH might thus represent a master switch that regulates both thyroid economy and the expression of multiple cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α (13, 23). The current results suggest that the IL-1 family represents a previously unidentified set of effectors downstream from TSHR. But this molecular crossroads might also represent peril in that unintended consequences could result from the close proximity of distinct pathways.

IL-1α and IL-1β exert powerful proinflammatory actions on many target cells. As a consequence, they have been examined extensively for their putative roles not only in infectious events but also in autoimmune diseases. As closely related molecules, IL-1RA proteins have been considered critical determinants of both the amplitude and duration of the inflammatory responses provoked by IL-1 (1, 2). They have been characterized for not only their participation in disease pathogenesis but also as potential therapeutics. When the balance between IL-1 and IL-1RA becomes disrupted, either by virtue of excessive production of one or diminished levels of the other, exaggerated tissue reactivity can occur, leading to disruption of tissue architecture or function (5, 6). This imbalance may well explain the situation arising in active TAO. IL-1α and IL-1β have been detected in orbital tissues affected by the disease (24) as has IL-1RA (25). IL-1RA is induced in cytokine-activated GD-OFs and can be regulated by several factors including glucocorticoids. The levels of sIL-1RA resulting from exposure to TSH appear to be considerably lower than those of icIL-1RA in these cells (Figure 1B). This dichotomy becomes even more apparent when the profile of IL-1RA gene expression in OFs is compared with that of fibrocytes treated with either IL-1β (17) or TSH (Figure 2). The relative underrepresentation of sIL-1RA in the gene expression repertoire in GD-OFs is of particular importance in reconciling the apparent susceptibility of the orbit to inflammation because sIL-1RA accounts for much of the IL-1-blocking actions attributed to IL-1RA (26). In fact, sIL-1RA appears to dominate the modulation and resolution of IL-1-mediated chronic inflammation. In contrast, the impact of icIL-1RA on the actions of either IL-1α or IL-1β remains unclear (27–29). Watson et al (29) reported that icIL-1RA1 expressed in malignant human ovarian epithelial cells inhibited mature IL-1α-induced IL-18 expression by decreasing mRNA stability. Furthermore, cotransfecting icIL-1RA1 with either pro-IL-1α or ppIL-1α blocked their effects on cell migration, an effect apparently related to intracellular activity (30). The current findings suggest that TSH might play an important and previously unrecognized regulatory role in determining the balance between IL-1 and IL-1RA through its induction of both molecules.

The aggregate of our results suggests that although modest up-regulation of gene transcription might contribute to increases provoked by TSH of the levels of IL-1RA, the dominant mechanistic component appears to result from cell- and isoform-specific changes in mRNA stability. The results shown in Figure 4B, demonstrating divergent activities of a 3′UTR-linked reporter in response to TSH, suggest that its effects on IL-1RA mRNA stabilization are mediated through interactions occurring at the UTR in fibrocytes but not in OFs. Thus, the determinants of IL-1RA mRNAs in OFs might instead be mediated through sequences located elsewhere in the mature transcript.

Relatively few previous studies have examined relationships between the IL-1 and TSH pathways. IL-1β inhibits release of TSH from the pituitary while enhancing that of prolactin and GH (31). It reduces TSH and thyroid hormone levels in rats (32). IL-1β attenuates TSH-dependent thyroglobulin expression (33, 34). TSH and IL-1β synergistically enhance the synthesis of IL-6 in FRTL-5 cells (35). On the other hand, IL-1 inhibited TSH-dependent FRTL-5 proliferation (36). Earlier studies have examined circulating IL-1RA levels in the context of GD and TAO (37, 38). But nowhere could we find previous evidence that TSH might regulate IL-1 or IL-1RA. The current findings suggest a novel relationship in which IL-1 could represent an effector arm of TSH. Thus, it might be added to other cytokines such as IL-6, which are induced in fibrocytes (13, 23).

The connectivity between pathways regulating thyroid economy and host defense suggests important potential consequences associated with the pathological activation of TSHR. This connection might provide a plausible explanation underlying the widely recognized development/worsening of TAO in poorly managed hypothyroidism, such as following 131iodine thyroid ablation (39). Moreover, the current findings suggest a potential complication associated with the use of small molecules (40) and blocking anti-TSHR monoclonal antibodies as therapy in TAO. Additional studies will be necessary to assess the impact of TSH on immune responses and IL-1-dependent inflammation.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Ms Roshini Fernando for her great help with some of the experiments.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants EY008976, EY011708, and DK063121; the Center for Vision Grant EY007003 from the National Eye Institute; an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness; and the Bell Charitable Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

Footnotes

- bTSH

- bovine TSH

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DRB

- 5,6-dichlorobenzimidazole

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GD

- Graves' disease

- GD-OF

- GD orbital fibroblast

- icIL-1RA

- IL-1RA form with three intracellular proteins

- IL-1RA

- IL-1 receptor antagonist

- OF

- orbital fibroblast

- Pol II

- polymerase II

- sIL-1RA

- secreted isoform of IL-1RA

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- TAO

- thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy

- TSHR

- TSH receptor

- UTR

- untranslated region.

Reference

- 1. Arend WP, Palmer G, Gabay C. IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33 families of cytokines. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:20–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gabay C, Lamacchia C, Palmer G. IL-1 pathways in inflammation and human diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:232–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malyak M, Smith MF, Jr, Abel AA, Hance KR, Arend WP. The differential production of three forms of IL-1 receptor antagonist by human neutrophils and monocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:2004–2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Butcher C, Steinkasserer A, Tejura S, Lennard AC. Comparison of two promoters controlling expression of secreted or intracellular IL-1 receptor antagonist. J Immunol. 1994;153:701–711 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Opp MR, Krueger JM. Interleukin 1-receptor antagonist blocks interleukin 1-induced sleep and fever. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R453–R457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Romero R, Sepulveda W, Mazor M, et al. The natural interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in term and preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;167:863–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang HY, Wen Y, Kruessel JS, Raga F, Soong YK, Polan ML. Interleukin (IL)-1β regulation of Il-1β and IL-1 receptor antagonist expression in cultured human endometrial stromal cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:1387–1393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rapoport B, Chazenbalk GD, Jaume JC, McLachlan SM. The thyrotropin (TSH) receptor: interaction with TSH and autoantibodies. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:673–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Endo T, Ohno M, Kotani S, Gunji K, Onaya T. Thyrotropin receptor in non-thyroid tissues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;15:774–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feliciello A, Porcellini A, Ciullo I, Giulio B, Avvedimento EV, Fenzi G. Expression of thyrotropin-receptor mRNA in healthy and Graves' disease retro-orbital tissue. Lancet. 1993;342:337–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Valyasevi RW, Erickson DZ, Harteneck DA, et al. Differentiation of human orbital preadipocyte fibroblasts induces expression of functional thyrotropin receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:2557–2562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Herzog EL, Bucala R. Fibrocytes in health and disease. Exp Hermatol. 2010;38:548–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Douglas RS, Afifiyan NF, Hwang CJ, et al. Increased generation of fibrocytes in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:430–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fernando R, Atkins S, Raychaudhuri N, et al. Human fibrocytes coexpress thyroglobulin and thyrotropin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:7427–7432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bahn RS. Graves' ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:726–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith TJ. Pathogenesis of Graves' orbitopathy: a 2010 update. J Endocrinol Invest. 2010;33:414–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li B, Smith TJ. Divergent expression of IL-1 receptor antagonists in CD34+ fibrocytes and orbital fibroblasts in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy: contribution of fibrocytes to orbital inflammation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2783–2790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gabay C, Smith MF, Eidlen D, Arend WP. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) is an acute-phase protein. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2930–2940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smith TJ. Dexamethasone regulation of glycosaminoglycan synthesis in cultured human skin fibroblasts. Similar effects of glucocorticoid and thyroid hormones. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:2157–2163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bucala R, Spiegel LA, Chesney J, Hogan M, Cerami A. Circulating fibrocytes define a new leukocyte subpopulation that mediates tissue repair. Mol Med. 1994;1:71–81 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bittencourt D, Auboeuf D. Analysis of co-transcriptional RNA processing by RNA-ChIP assay. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;809:563–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang HS, Cao HJ, Winn VD, et al. Leukoregulin induction of prostaglandin-endoperoxide H synthase-2 in human orbital fibroblasts. An in vitro model for connective tissue inflammation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22718–22728 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gillespie EF, Papageorgiou KI, Fernando R, et al. Increased expression of TSH receptor by fibrocytes in thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy leads to chemokine production. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E740–E746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hiromatsu Y, Yang D, Bednarczuk T, Miyake I, Nonaka K, Inoue Y. Cytokine profiles in eye muscle tissue and orbital fat tissue from patients with thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1194–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cao HJ, Han R, Smith TJ. Robust of PGHS-2 by IL-1 in orbital fibroblasts results from low levels of IL-1 receptor antagonist expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C1429–C1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arend WP, Malyak M, Guthridge CJ, Gabay C. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: role in biology. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:27–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Evans I, Dower SK, Francis SE, Crossman DC, Wilson HL. Action of intracellular IL-1Ra (type 1) is independent of the IL-1 intracellular signalling pathway. Cytokine. 2006;33:274–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levine SJ, Wu T, Shelhamer JH. Extracellular release of the type I intracellular IL-1 receptor antagonist from human airway epithelial cells: differential effects of IL-4, IL-13, IFN-γ, and corticosteroids. J Immunol. 1997;158:5949–5957 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Watson JM, Lofquist AK, Rinehart CA, et al. The intracellular IL-1 receptor antagonist alters IL-1 inducible gene expression without blocking exogenous signaling by IL-1β. J Immunol. 1995;155:4467–4475 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Merhi-Soussi F, Berti M, Wehrle-Haller B, Gabay C. Intracellular interleukin-1 receptor antagonist type 1 antagonizes the stimulatory effect of interleukin-1α precursor on cell motility. Cytokine. 2005;32:163–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rettori V, Jurcovicova J, McCann SM. Central action of interleukin-1 in altering the release of TSH, growth hormone, and prolactin in the male rat. J Neurosci Res. 1987;18:179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dubois JM, Dayer JM, Siegrist-Kaiser CA, Burger AG. Human recombinant interleukin-1β decreases plasma thyroid hormone and thyroid stimulating hormone levels in rats. Endocrinology. 1988;123:2175–2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yamashita S, Kimura H, Ashizawa K, et al. Interleukin-1 inhibits thyrotrophin-induced human thyroglobulin gene expression. J Endocrinol. 1988;122:177–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kung AW, Lau KS. Interleukin-1β modulates thyrotropin-induced thyroglobulin mRNA transcription through 3′5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Endocrinology. 1990;127:1369–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iwamoto M, Sakihama T, Kimura T, Tasaka K, Onaya T. Augmented interleukin-6 production by rat thyrocytes (FRTL5): effect of interleukin-1β and thyroid stimulating hormone. Cytokine. 1991;3:345–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Azuma H, Zeki K, Tanaka Y, et al. Inhibitory effect of IL-1 on the TSH dependent growth of rat thyroid cells (FRTL-5). Endocrinology. 1990;37:619–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bartalena L, Manetti L, Tanda ML, et al. Soluble interleukin-1 receptor antagonist concentration in patients with Graves' ophthalmopathy is neither related to cigarette smoking nor predictive of subsequent response to glucocorticoids. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2000;52:647–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Salvi M, Pedrazzoni M, Girasole G, et al. Serum concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines in Graves' disease: effect of treatment, thyroid function, ophthalmopathy and cigarette smoking. Eur J Endocrinol. 2000;2:197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stan MN, Durski JM, Brito JP, Bhagra S, Thapa P, Bahn RS. Cohort study on radioactive iodine-induced hypothyroidism: implications for Graves' ophthalmopathy and optimal timing for thyroid hormone assessment. Thyroid. 2013;23:620–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Neumann S, Eliseeva E, McCoy JG, et al. A new small-molecule antagonist inhibits Graves' disease antibody activation of the TSH receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:548–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]