Abstract

Background

The presence of widespread pain is easily determined and is known to increase the risk for persistent symptoms.

Objective

The study hypothesis was that people with no or minimal knee osteoarthritis (OA) and high Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Pain Scale scores would be more likely than other subgroups to report widespread pain.

Design

A cross-sectional design was used.

Methods

Data were obtained from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study, which includes people with or at high risk for knee OA. The inclusion criteria were met by 755 people with unilateral knee pain and 851 people with bilateral knee pain. Widespread pain was assessed with body diagrams, and radiographic Kellgren-Lawrence grades were recorded for each knee. Knee pain during daily tasks was quantified with WOMAC Pain Scale scores.

Results

Compared with people who had high levels of pain and knee OA, people with a low level of pain and a high level of knee OA, and people with low levels of pain and knee OA, a higher proportion of people with a high level of knee pain and a low level of knee OA had widespread pain. This result was particularly true for people with bilateral knee pain, for whom relative risk estimates ranged from 1.7 (95% confidence interval=1.2–2.4) to 2.3 (95% confidence interval=1.6–3.3).

Limitations

The cross-sectional design was a limitation.

Conclusions

People with either no or minimal knee OA and a high level of knee pain during daily tasks are particularly likely to report widespread pain. This subgroup is likely to be at risk for not responding to knee OA treatment that focuses only on physical impairments. Assessment of widespread pain along with knee pain intensity and OA status may assist physical therapists in identifying people who may require additional treatment.

Radiographic signs of arthritic disease have long been known to be imperfect indicators of symptom status.1,2 Associations between radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis (OA) and knee pain in groups of people also have varied, ranging from weak3 to substantial,4 depending on the analytic approach. However, no studies have been found to indicate that radiographic evidence, in isolation, was diagnostic of symptomatic knee OA.

Because the clinical implications of this discordance are substantial,5–7 efforts have been focused on determining why there is incongruence between radiographic and symptomatic indicators of knee arthritis. In particular, emphasis has been placed on the roles of psychological stressors, pain coping, and central and peripheral pain processing constructs in explaining why symptoms sometimes are inconsistent with radiographic arthritis measures.8–11 Finan et al,10 for example, studied associations between several quantitative measures of abnormal central pain processing (central sensitization) and subgroups of patients with knee pain and knee radiographic findings that were either concordant (eg, high level of knee pain and extensive [high level of] radiographic knee OA) or discordant (eg, high level of knee pain and either no or minimal [low level of] knee OA) for knee pain and OA status. Finan et al found that people with a high level of pain and a low level of knee OA had significantly higher scores on 3 of 4 quantitative sensory tests of central sensitization than those with a low level of pain and a high level of knee OA. Direct clinical application of the work by Finan et al is limited because procedures used to quantify pain processing impairments are not routinely used in clinical practice and the effects of unilateral versus bilateral knee pain were not explored.

Recent additions to the physical therapy literature place strong emphasis on the identification of psychologically based prognostic factors associated with poor outcomes. Abnormal pain coping, for example, has been studied fairly extensively in the context of physical therapy diagnosis and treatment.12,13 Because physical therapists frequently treat patients with pain, research examining the role of pain-related psychologically based impairments seems prudent for patients with a variety of pain disorders and syndromes. Patients who are middle aged or older and have knee pain, with or without OA, are among those most commonly treated by physical therapists14 and would appear to be at risk for psychologically based pain-related impairments.15

Widespread pain is an easily determined clinical finding that has been attributed to a variety of etiological factors, including abnormal peripheral pain processing, central pain processing, or both, and a variety of psychological factors.16–18 The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) defines widespread pain as concurrent pain in the axial region, above and below the waist, and pain on the right and left sides of the body.19 The ACR originally defined widespread pain as a diagnostic criterion for identifying people with fibromyalgia, but widespread pain also has been found in people with OA and low back pain, among other disorders.15 Several authors have proposed theories to explain the link among abnormal pain processing, widespread pain, and rheumatic disorders.16,17,20–24 Knee pain with or without OA and simultaneously occurring widespread pain are important to identify early in the course of care because patients with these conditions are at increased risk for fibromyalgia25 and may be less likely to benefit from physical therapist–delivered interventions designed to target physical impairments.26–29 In our experience, physical therapists do not routinely assess for the presence of widespread pain, particularly in people referred for treatment of a specific body region, such as the knee. Given that widespread pain is associated with psychologically based impairments, abnormal pain processing, and poor outcomes, assessments for the presence of widespread pain have potential for providing clinically important information during diagnostic workup and treatment planning.

The purpose of our study was to determine whether widespread pain is more common in people with a high level of knee pain during daily tasks and no or minimal knee OA than in people with a high level of pain and a high level of knee OA, people with a low level of pain and a high level of knee OA, or people with a low level of pain and a low level of knee OA. We performed separate assessments for associations in people with unilateral knee pain and people with bilateral knee pain because of a potentially greater influence of bilateral knee symptoms on widespread pain frequency. We hypothesized that people with a high level of knee pain during daily tasks and no or minimal knee OA, either unilateral or bilateral, would have higher rates of widespread pain than those with the other combinations of pain and OA listed above. Given that the clinical assessment for widespread pain is straightforward, the findings could have important clinical implications for identifying people who have knee pain and may be candidates for treatments designed to reduce widespread pain and associated psychologically based impairments along with more traditional interventions directed toward localized knee impairments.25

Method

Participants

Data for these analyses were obtained from the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study, a multicenter longitudinal cohort study of 3,026 community-dwelling adults who either had or were at high risk of developing symptomatic knee OA.30 People who were 50 to 79 years of age were recruited from communities in or near Iowa City, Iowa, or Birmingham, Alabama. Adults were excluded if they screened positive for rheumatoid arthritis; were diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, or reactive arthritis; were undergoing dialysis; had a history of nonmelanoma cancer; had a history of bilateral knee replacement surgery; were unable to walk without a walker or assistance from another person; or were planning to move from the area within the next 3 years. Participants signed consent forms approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Iowa and the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

At the baseline session, we selected participants who reported pain scores of 20 or higher in 1 or both knees on a visual analog scale from 0 to 100 to indicate their average pain over the previous 30 days. We chose this criterion to create a sample of participants whose average pain and self-reported functional deficits were similar to those expected for people seeking medical care for their knee pain.31

Variables of Interest

To quantify knee pain during daily tasks, we used the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Pain Scale, which ranges from 0 (no function-related pain) to 20 (severe function-related pain).32 The WOMAC Pain Scale, which also was used by Finan et al,10 was designed to capture perceptions of pain associated with daily life activities, such as falling asleep, walking, and climbing stairs.32,33 Substantial evidence exists to support the reliability and validity of the WOMAC Pain Scale.34 For participants classified as having unilateral knee pain, we used the WOMAC Pain Scale score for the involved knee. For participants with bilateral knee pain, we used the sum of the WOMAC Pain Scale scores for both knees. To divide the participant groups into those with high levels of knee pain and those with low levels of knee pain, we used median splits.10

All participants underwent bilateral flexed weight-bearing posteroanterior radiographic knee evaluations with standardized procedures.30 Two experienced radiographic assessors who were unaware of the clinical data graded the tibiofemoral joints using Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grades.35 A grade of 0 was normal; 1 indicated doubtful narrowing of the joint space and possible osteophytic lipping; 2 indicated definite osteophytes and possible narrowing of the joint space; 3 indicated definite narrowing of the joint space, some sclerosis, and possible deformity of bone ends; and 4 indicated large osteophytes, marked narrowing of joint space, severe sclerosis, and definite deformity of bone ends. Disagreements between the readers were adjudicated by a third reader to reach a consensus.

Much like Finan et al,10 we categorized participants' knees as either having no or mild knee OA (KL grade of ≤2) or having moderate to severe knee OA (KL grade of ≥3). For participants with unilateral knee pain, we used the KL grade for the involved knee. We grouped participants with bilateral knee pain into the following categories: a KL grade of ≤2 for both knees or a KL grade of ≥3 for at least 1 knee. We chose this approach because KL grades of ≤2 reflect no joint space narrowing, whereas KL grades of ≥3 indicate definite joint space narrowing and a much higher likelihood of OA-related pain.4

The presence of widespread pain was determined with the ACR criterion, which requires pain to be reported on the left side and the right side of the body, pain above the waist, and pain below the waist.19 Participants were asked to mark the painful joints on a specially designed body diagram in response to the following instruction: “Please fill in the bubbles in the pictures below to show which joints (or body regions) have had pain, aching, or stiffness on most days in the past 30 days.” Bubble symbols were placed on the hips, knees, ankles, wrists, elbows, shoulders, hands, fingers, upper middle back, lower back, and the neck. Widespread pain was classified as either present or absent, depending on whether participants met the ACR criterion. For a sensitivity analysis, we also classified widespread pain as present if a participant filled in bubbles on the body diagram indicating pain in at least 1 joint region of all 4 limbs in addition to spinal pain.

Covariates were age; sex; comorbidity, as measured with a validated self-report scale36; depression, as measured with the validated Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale37,38; race (white, black or African American, or other); and body mass index. The modified Charlson Comorbidity Index is a validated questionnaire that asks people a series of questions regarding the presence and impact of diseases such as heart attack, diabetes, and cancer.36 These covariates were chosen because they have been shown to be related to knee OA incidence or progression in people with knee pain and arthritis.39–43 Patellofemoral joint OA status also was included as a covariate and was assessed with lateral radiographs. Radiographic data were categorized as either patellofemoral OA present (ie, a definite osteophyte or likely joint space narrowing, as indicated by a KL grade of ≥1, plus any osteophyte, sclerosis, or cyst in the patellofemoral joint) or OA absent.

Analytic Approach

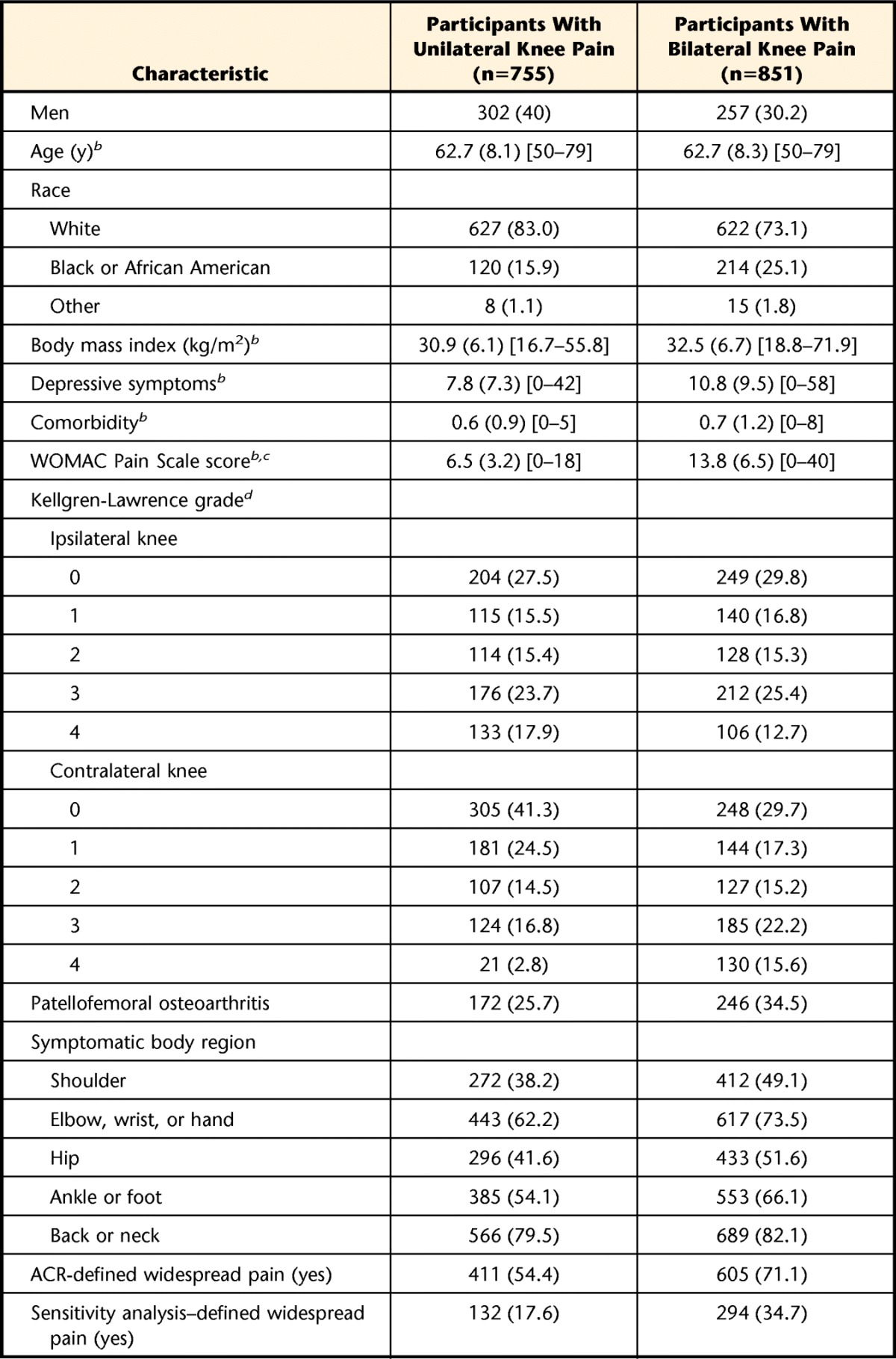

We calculated descriptive statistics for participants with unilateral knee pain and participants with bilateral knee pain (Tab. 1). Our primary analysis addressed the extent to which widespread pain was associated with an increased risk of being a member of the subgroup of participants with a high level of pain and a low KL grade (high pain/low KL subgroup). Specifically, we considered widespread pain to be the exposure variable in logistic regression models and subgroup membership to be the response variable. Using the ACR classification of widespread pain and the unilateral knee pain analysis as an example, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) that compared the high pain/low KL subgroup to each of the other 3 subgroups (ie, participants with a high level of pain and a high KL grade [high pain/high KL subgroup], participants with a low level of pain and a high KL grade [low pain/high KL subgroup], and participants with a low level of pain and a low KL grade [low pain/low KL subgroup]). Given that 3 comparisons were performed, we considered an effect to be statistically significant if the P value was less than .017.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants With Unilateral Versus Bilateral Knee Paina

Data are reported as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise indicated. Some percentage calculations are based on slightly smaller sample sizes due to missing data. ACR=American College of Rheumatology.

b Data are reported as mean (SD) [range].

c For people with bilateral knee pain, the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities (WOMAC) Pain Scale score is the sum of the WOMAC Pain Scale scores for both knees.

d For people with bilateral knee pain, the ipsilateral knee Kellgren-Lawrence grade is for the right knee, and the contralateral knee grade is for the left knee.

In addition, we performed a logistic regression analysis in which we adjusted for the covariates of age, sex, race, body mass index, depressive symptoms, comorbidity, and patellofemoral joint involvement. We chose logistic regression as our primary analytic approach because it allows for an adjustment of covariates. However, ORs overestimate relative risk as the prevalence of the outcome of interest increases. For this reason, we also calculated relative risk.

We repeated this analytic approach for participants with bilateral involvement and as part of a sensitivity analysis in which the widespread pain standard requiring pain in at least 1 joint region of all 4 limbs in addition to spinal pain was applied.

Analyses were performed with STATA version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Role of the Funding Source

The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST) comprises 4 cooperative grants (Felson–AG18820, Torner–AG18832, Lewis–AG18947, and Nevitt–AG19069) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the US Department of Health and Human Services, and is conducted by MOST study investigators. This article was prepared with MOST data but does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of MOST study investigators. The funding source played no role in the design or conduct of the current study.

Results

Our sample comprised 755 participants with unilateral knee pain and 851 participants with bilateral knee pain. Participants with bilateral knee pain were more commonly women and African American, had a higher body mass index, and had a higher level of depressive symptoms than participants with unilateral knee pain. Participants with bilateral knee pain also more frequently reported widespread pain on the basis of both the ACR criterion and the alternative definition of widespread pain (sensitivity analysis) (Tab. 1).

Participants With Unilateral Knee Pain

For participants with unilateral knee pain, the prevalence of widespread pain, as determined with the ACR criterion, was 54% (95% confidence interval=51%–58%); the prevalence of widespread pain, as determined with the more stringent sensitivity analysis criterion, was 17%. When we applied the ACR criterion to participants with unilateral knee pain, we found a significantly greater risk of participants with widespread pain being members of the high pain/low KL subgroup than of the low pain/high KL subgroup (Tab. 2). The adjusted OR was 1.9 (P=.015).

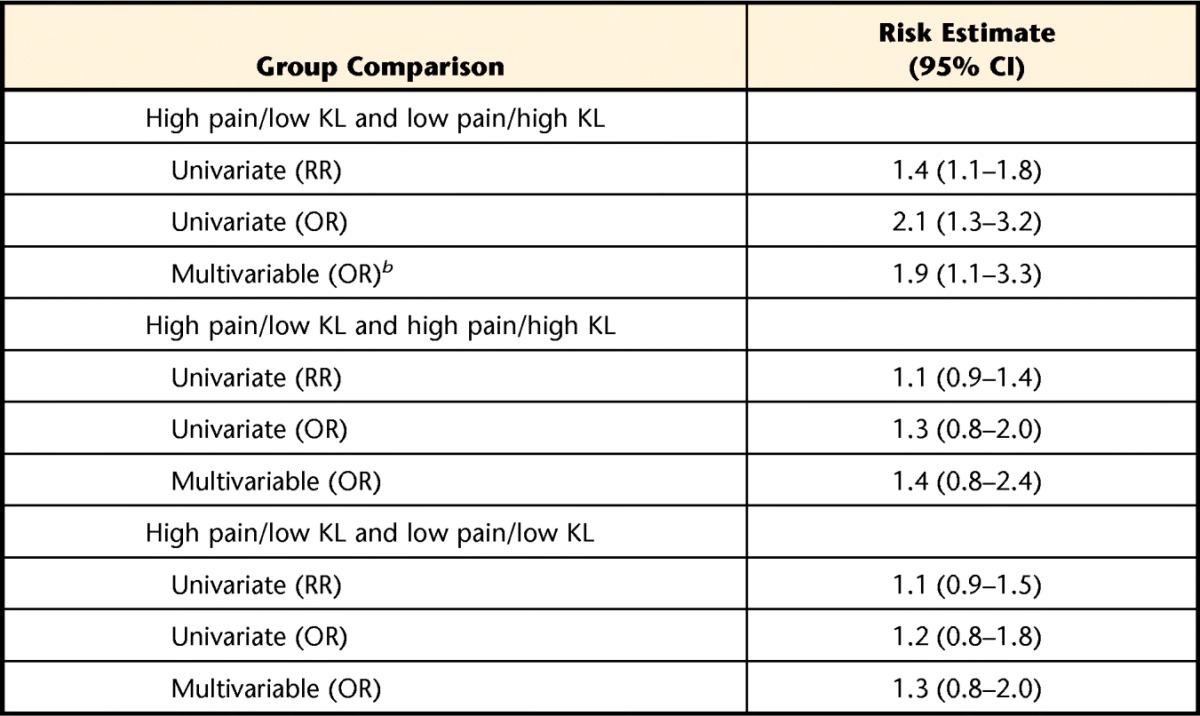

Table 2.

Unilateral Knee Pain Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios for Associations With Widespread Paina

CI=confidence interval, KL=Kellgren-Lawrence grade for knee osteoarthritis, RR=relative risk, OR=odds ratio.

b These estimates were adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, depressive symptoms, comorbidity, and patellofemoral involvement.

The sensitivity analysis for participants with unilateral knee pain provided a similar pattern of findings (for the high pain/low KL subgroup compared with the low pain/high KL subgroup: unadjusted OR=2.4, P=.006; adjusted OR=2.3, P=.014) (data not shown).

For all analyses, relative risk estimates were lower than their respective ORs, but statistical significance was maintained only for the comparison of the high pain/low KL subgroup with the low pain/high KL subgroup. The more conservative relative risk estimate indicated that participants in the high pain/low KL subgroup were, on average, 40% more likely to have widespread pain than participants in the low pain/high KL subgroup. The relative risk estimates for the other 2 subgroup comparisons were not significantly different from 1, that is, no increased risk of widespread pain for participants with unilateral knee pain (Tab. 2).

Participants With Bilateral Knee Pain

For participants with bilateral knee pain, the prevalence of widespread pain, as determined with the ACR criterion, was 71% (95% confidence interval=68%–74%); the prevalence of widespread pain, as determined with the more stringent sensitivity analysis criterion, was 34%. For participants with bilateral knee pain, there was a significantly greater risk of participants with widespread pain being members of the high pain/low KL subgroup than of the other 3 subgroups (Tab. 3). This finding was consistent for both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. For example, the adjusted analysis indicated that participants with widespread pain had a greater risk of being members of the high pain/low KL subgroup than of the low pain/high KL subgroup (OR=2.9, P=.008), low pain/low KL subgroup (OR=2.1, P=.001), or high pain/high KL subgroup (OR=1.6, P=.018).

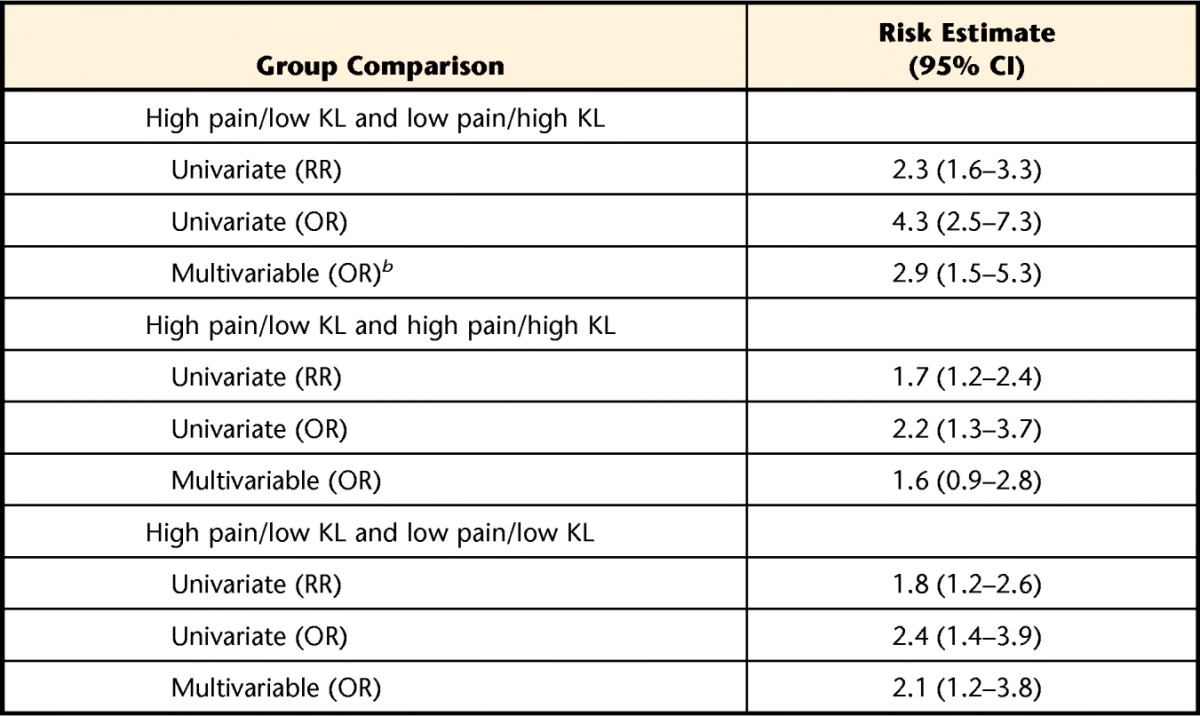

Table 3.

Bilateral Knee Pain Unadjusted and Adjusted Odds Ratios for Associations With Widespread Paina

CI=confidence interval, KL=Kellgren-Lawrence grade for knee osteoarthritis, RR=relative risk, OR=odds ratio.

b These estimates were adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, depressive symptoms, comorbidity, and patellofemoral involvement.

The sensitivity analysis for people with bilateral knee pain provided a similar pattern of findings, and all comparisons with the high pain/low KL subgroup were statistically significant (P<.017) (data not shown).

The relative risk estimates for all 3 subgroup comparisons indicated that participants in the high pain/low KL subgroup were, on average, 70% to 130% more likely to have widespread pain than those in the other 3 subgroups (Tab. 3).

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether participants in subgroups defined by WOMAC Pain Scale knee pain ratings and radiographic determinations of knee OA severity would show hypothesized patterns of prevalence of widespread pain. Subgroups of participants with high WOMAC Pain Scale ratings for knee pain with activity and low KL grades were significantly more likely to have widespread pain than other subgroups, particularly in comparisons of participants with bilateral knee pain. Our interpretation of this finding is that people who have discordant pain and knee OA measures, such that they have a high level of pain and no or minimal knee OA, are the most likely to report widespread pain. Although the results were consistent for participants with either unilateral or bilateral knee pain, the presence of bilateral pain produced a larger and more consistent effect in the subgroups. This finding was consistent for both the ACR definition of widespread pain and the more rigorous sensitivity analysis criterion of pain reported in all 4 limbs in addition to spinal pain.

The clinical implications of these findings are potentially substantial. Clinicians should be vigilant when performing assessments for the presence of widespread pain, particularly when patients report bilateral knee pain. Interventions typically focused only on knee joint structures may be less effective for people with widespread pain in addition to knee pain.26–28 People with minimal knee OA and a high level of knee pain during daily tasks appear to be at particularly high risk for likely causes of widespread pain, such as abnormal pain processing and psychologically related factors. Assessments of widespread pain may aid in identifying patients who have OA and may benefit from psychologically based interventions as well as those who may be relatively unresponsive to knee-focused interventions, including surgery.5,6 Some patients may respond to interventions designed to address pain-related physical impairments in other body regions. Clinicians should consider using our cutpoints when considering the risk of widespread pain in their patients. A low level of knee pain was considered to be present when WOMAC Pain Scale scores were ≤6 in participants with unilateral knee problems and ≤13 (WOMAC Pain Scale scores for both knees combined) in participants with bilateral knee pain. Splits for KL grades were ≤2 for a low KL grade and 3 or 4 for a high KL grade in the tibiofemoral joints.

The overall prevalence of ACR-defined widespread pain in the present study was 63.7%—much higher than the 12.5% population-based estimate for people 50 years of age or older.44 Schiphof et al29 reported a lower prevalence—8.7% to 16.9%—in people with knee OA of various KL grades, but many people in the sample had either no pain or no knee OA. In addition, the fact that the participants were asked only 2 questions regarding pain sites may have led to underreporting of pain in other locations. We suspect that the present study revealed a higher prevalence of widespread pain than previous reports because we included only people who had pain with a rating of 2 or higher on a verbal pain rating scale from 0 to 10 and because the determination of pain in other locations required people to focus specifically on all major joint regions by using a body diagram when documenting the presence of pain; this approach likely enhanced complete reporting.

The results of the present study are consistent with those of Finan et al10 to the extent that widespread pain was found to be associated with KL and pain subgroups in strikingly similar patterns. For example, compared with the subgroups with low levels of pain, the subgroups with high levels of pain generally had higher (worse) quantitative sensory test scores (in the study by Finan et al) or a greater proportion with widespread pain (in the present study).

Patients in the study by Finan et al10 were initially recruited for a study designed to assess the effects of psychosocially based treatments for pain and insomnia. A total of 76% of patients were reported to have a diagnosis of insomnia. The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study, the parent study for our participants, was not designed specifically to study insomnia, but a substantial proportion of the participants reported some level of sleep disturbance. One item on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression measure38 is worded as follows: “My sleep was restless.” A total of 72.3% of the participants in the present study reported having at least 1 or 2 nights of restless sleep in the preceding week. Although the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study did not document whether people were diagnosed with insomnia, sleep problems were common; this finding is typical in studies of people with OA.45

Widespread pain has been studied from a variety of perspectives. For example, a genetic predisposition for chronic widespread pain was recently reported.46 Widespread pain has been shown to be predictive of declines in walking speed47 and of the presence of consistent versus inconsistent knee pain.48 Jinks et al49 found that widespread pain predicted the onset of mild and severe knee pain in a population-based sample of people more than 50 years of age. For a variety of reasons, it appears that physical therapists should determine the widespread pain status of patients who are middle aged or older and are being seen for knee pain.

Perhaps the most important limitation of the present study was its cross-sectional nature. The present study did not provide direct evidence of the prognostic importance of widespread pain, although a substantial body of literature on a variety of disorders exists to support this inference.26,28,49 Future work should examine the potential prognostic significance of measures of widespread pain to determine whether interventions designed to reduce widespread pain have the potential to reduce chronicity and enhance functional status in patients with widespread pain and knee OA. In addition, we dichotomized our WOMAC Pain Scale knee pain and OA measures for the purposes of subgrouping participants. Although we contend that these subgroups have potential clinical utility (ie, in our experience, physical therapists sometimes subgroup patients on the basis of high or low levels of pain or disease status), some information is lost when measures are converted from quantitative to dichotomous. In our view, we improved the clinical interpretation of findings using this approach, but we likely also lost some information and statistical power.

Conclusion

The subgroup of participants with high WOMAC Pain Scale knee pain scores and no or minimal knee OA had the highest prevalence of participants with widespread pain. The findings were similar for participants with either unilateral or bilateral knee pain, but the findings for bilateral knee pain were more robust. The evidence suggested that widespread pain should be considered part of the clinical examination of people who are middle aged or older and have knee pain. People with high WOMAC Pain Scale knee pain scores, no or minimal OA, and widespread pain represent a specific subgroup of people who are at risk for persistent symptoms and who may benefit from psychologically based interventions designed to reduce or eliminate widespread pain. For some people, interventions directed toward pain-related physical impairments in other body regions also may be effective. Research is needed to explore the role of psychologically based interventions for people with knee pain and widespread pain.

The Bottom Line

What do we already know about this topic?

People with widespread pain are at risk for poor outcomes. Identifying the presence of widespread pain in people seeking physical therapy may assist in establishing prognosis and in considering the use of psychologically based interventions.

What new information does this study offer?

This study found that middle-aged and older people with high levels of knee pain, but either no or minimal knee osteoarthritis (OA), are at higher risk for widespread pain than are people with more substantial knee OA or low levels of knee pain. This finding is particularly true for people with bilateral knee pain.

If you're a patient or a caregiver, what might these findings mean for you?

If you have widespread pain along with knee pain, especially if you have pain in both knees, you should consider seeking out physical therapists who have experience using pain coping treatment approaches.

Footnotes

Both authors provided concept/idea/research design, writing, and data analysis. Dr Riddle provided data collection, project management, clerical support, and consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Iowa and the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

The Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study (MOST) comprises 4 cooperative grants (Felson–AG18820, Torner–AG18832, Lewis–AG18947, and Nevitt–AG19069) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the US Department of Health and Human Services, and is conducted by MOST study investigators. This article was prepared with MOST data but does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of MOST study investigators.

References

- 1. Torgerson WR, Dotter WE. Comparative roentgenographic study of the asymptomatic and symptomatic lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:850–853 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lawrence JS, Bremner JM, Bier F. Osteo-arthrosis: prevalence in the population and relationship between symptoms and x-ray changes. Ann Rheum Dis. 1966;25:1–24 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bedson J, Croft PR. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Neogi T, Felson D, Niu J, et al. Association between radiographic features of knee osteoarthritis and pain: results from two cohort studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b2844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dowsey MM, Nikpour M, Dieppe P, Choong PF. Associations between pre-operative radiographic changes and outcomes after total knee joint replacement for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:1095–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Valdes AM, Doherty SA, Zhang W, et al. Inverse relationship between preoperative radiographic severity and postoperative pain in patients with osteoarthritis who have undergone total joint arthroplasty. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41:568–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moseley JB, O'Malley K, Petersen NJ, et al. A controlled trial of arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis of the knee. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Creamer P, Hochberg MC. The relationship between psychosocial variables and pain reporting in osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11:60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Creamer P, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Costa P, et al. The relationship of anxiety and depression with self-reported knee pain in the community: data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Arthritis Care Res. 1999;12:3–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Finan PH, Buenaver LF, Bounds SC, et al. Discordance between pain and radiographic severity in knee osteoarthritis: findings from quantitative sensory testing of central sensitization. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:363–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Baar ME, Dekker J, Lemmens JA, et al. Pain and disability in patients with osteoarthritis of hip or knee: the relationship with articular, kinesiological, and psychological characteristics. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:125–133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bergbom S, Boersma K, Overmeer T, Linton SJ. Relationship among pain catastrophizing, depressed mood, and outcomes across physical therapy treatments. Phys Ther. 2011;91:754–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fritz JM, Beneciuk JM, George SZ. Relationship between categorization with the STarT Back Screening Tool and prognosis for people receiving physical therapy for low back pain. Phys Ther. 2011;91:722–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Di Fabio RP, Boissonnault W. Physical therapy and health-related outcomes for patients with common orthopaedic diagnoses. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27:219–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Staud R. Evidence for shared pain mechanisms in osteoarthritis, low back pain, and fibromyalgia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2011;13:513–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Amris K, Jespersen A, Bliddal H. Self-reported somatosensory symptoms of neuropathic pain in fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain correlate with tender point count and pressure-pain thresholds. Pain. 2010;151:664–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graven-Nielsen T, Arendt-Nielsen L. Assessment of mechanisms in localized and widespread musculoskeletal pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:599–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee YC, Nassikas NJ, Clauw DJ. The role of the central nervous system in the generation and maintenance of chronic pain in rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yunus MB. Central sensitivity syndromes: a new paradigm and group nosology for fibromyalgia and overlapping conditions, and the related issue of disease versus illness. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:339–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lyon P, Cohen M, Quintner J. An evolutionary stress-response hypothesis for chronic widespread pain (fibromyalgia syndrome). Pain Med. 2011;12:1167–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arendt-Nielsen L, Fernandez-de Las Penas C, Graven-Nielsen T. Basic aspects of musculoskeletal pain: from acute to chronic pain. J Man Manip Ther. 2011;19:186–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Potvin S, Larouche A, Normand E, et al. DRD3 Ser9Gly polymorphism is related to thermal pain perception and modulation in chronic widespread pain patients and healthy controls. J Pain. 2009;10:969–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Normand E, Potvin S, Gaumond I, et al. Pain inhibition is deficient in chronic widespread pain but normal in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:219–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Goldenberg DL, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA. New concepts in pain research and pain management of the rheumatic diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2011;41:319–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grotle M, Foster NE, Dunn KM, Croft P. Are prognostic indicators for poor outcome different for acute and chronic low back pain consulters in primary care? Pain. 2010;151:790–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McBeth J, Prescott G, Scotland G, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy, exercise, or both for treating chronic widespread pain. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:48–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Papageorgiou AC, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ. Chronic widespread pain in the population: a seven year follow up study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:1071–1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schiphof D, Kerkhof HJ, Damen J, et al. Factors for pain in patients with different grades of knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:695–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Felson DT, Niu J, Guermazi A, et al. Correlation of the development of knee pain with enlarging bone marrow lesions on magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2986–2992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Belo JN, Berger MY, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Prognostic factors in adults with knee pain in general practice. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:143–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, et al. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bellamy N, Buchanan WW. A preliminary evaluation of the dimensionality and clinical importance of pain and disability in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. Clin Rheumatol. 1986;5:231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Collins NJ, Misra D, Felson DT, et al. Measures of knee function: International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Subjective Knee Evaluation Form, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Physical Function Short Form (KOOS-PS), Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADL), Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, Oxford Knee Score (OKS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Activity Rating Scale (ARS), and Tegner Activity Score (TAS). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(suppl 11):S208–S228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, et al. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34:73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blalock SJ, DeVellis RF, Brown GK, Wallston KA. Validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale in arthritis populations. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:991–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Belo JN, Berger MY, Reijman M, et al. Prognostic factors of progression of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:13–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dunlop DD, Semanik P, Song J, et al. Risk factors for functional decline in older adults with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1274–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mallen CD, Peat G, Thomas E, et al. Predicting poor functional outcome in community-dwelling older adults with knee pain: prognostic value of generic indicators. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1456–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Niu J, Zhang YQ, Torner J, et al. Is obesity a risk factor for progressive radiographic knee osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:329–335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Peters TJ, Sanders C, Dieppe P, Donovan J. Factors associated with change in pain and disability over time: a community-based prospective observational study of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:205–211 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thomas E, Peat G, Harris L, et al. The prevalence of pain and pain interference in a general population of older adults: cross-sectional findings from the North Staffordshire Osteoarthritis Project (NorStOP). Pain. 2004;110:361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Allen KD, Renner JB, DeVellis B, et al. Osteoarthritis and sleep: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1102–1107 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Peters MJ, Broer L, Willemen HL, et al. Genome-wide association study meta-analysis of chronic widespread pain: evidence for involvement of the 5p15.2 region. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:427–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. White DK, Felson DT, Niu J, et al. Reasons for functional decline despite reductions in knee pain: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Phys Ther. 2011;91:1849–1856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Neogi T, Nevitt MC, Yang M, et al. Consistency of knee pain: correlates and association with function. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2010;18:1250–1255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jinks C, Jordan KP, Blagojevic M, Croft P. Predictors of onset and progression of knee pain in adults living in the community: a prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:368–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]