Abstract

The approach using pyrrolidine enamine as substrate has been studied for this synthesis, and an important catalyst structural feature has been developed. After survey of pyrrolidine-based Brønsted acid catalyst, tetrazole catalyst (3f) was found to be optimal in synthesis of aminooxy carbonyl compounds in high yields, with complete enantioselectivity not only for aldehydes but also for ketones.

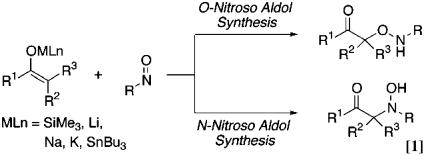

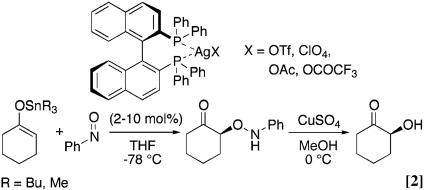

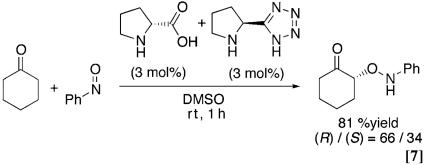

Regio- and stereoselective replacement of hydrogen by oxygen results in a rapid increase of molecular complexity (1–6). We recently described the catalytic enantioselective synthesis of α-hydroxy carbonyl compounds from ketone enolates (7). This method depends heavily on the new nitroso aldol synthesis (Eq. 1 and refs. 8 and 9), and by choosing the right catalyst, nitrosobenzene can function as an oxy electrophile for the enantioselective introduction of oxygen to α-position at carbonyl derivatives. The silver 2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl (BINAP) catalyst has been developed further into a highly reactive complex to generate α-aminooxy ketone with excellent regio- and enantioselectivity (Eq. 2).

|

|

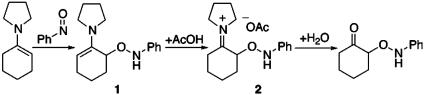

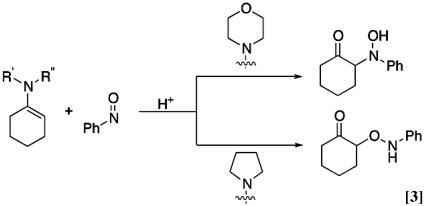

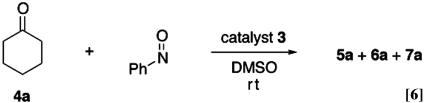

In 1972, Lewis et al. (10) reported the reaction of nitrosobenzene with 1-morpholin-1-ylcyclohexene followed by simple hydrolysis to give the hydroxyamino ketone as the major product. Surprisingly, however, we found that the similar reaction of nitrosobenzene with 1-pyrrolidin-1-ylcyclohexene followed by treatment with acetic acid gave rise to the aminooxy ketone almost exclusively (Eq. 3). The observed discrepancies may originate from the structural difference of enamines (11–18). We describe herein careful experiments on nitrosobenzene with pyrrolidine.

|

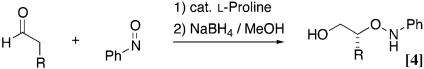

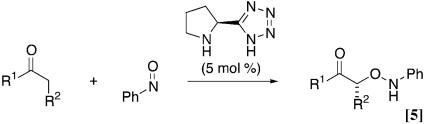

More recently MacMillan and coworkers (19), Zhong (20), and Hayashi et al. (21) independently reported the enantioselective nitroso aldol synthesis of nitrosobenzene and simple aldehydes using proline catalyst (Eq. 4). In fact, a series of recent reports of organic catalysts have shown that natural amino acid proline has been used to activate ketones and aldehyde as nucleophilic enamine intermediates for various reactions (22–25). We also reported a diamine-protonic acid catalyst (26, 27) and pyrrolidine-base tetrazole catalyst (28, 29) for asymmetric direct aldol reaction with high catalyst turnover. Herein we report that the tetrazole catalyst gave the aminooxy carbonyl compound in high yields with complete enantioselectivity not only for aldehydes but also for ketones (Eq. 5 and refs. 30 and 31).

|

|

Experimental Procedures

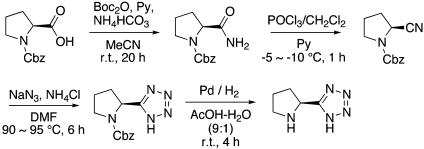

Preparation of l-Pyrrolidine-2-yl-1H-tetrazole (3f) (Scheme 1 and refs. 32 and 33). The ammonium hydrogen carbonate (1.26 eq) was added to the stirred solution of carbobenzyloxy-l-proline (1 eq), pyridine, and Boc2O (1.30 eq) in MeCN and stirred for 20 h. The solvent was removed, and the residue was diluted with ethyl acetate, washed with water, extracted with ethyl acetate, dried over MgSO4, and evaporated in vacuo to afford N-benzyloxycarbonyl-l-prolinamide as colorless crystals. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ7.36 (m, 5H, Ar-H), 6.71 (s, 1H, NHH), 5.81 (s, 1H, NHH), 5.20 (d, 1H, J = 12 Hz, OCHH), 5.15 (d, 1H, J = 12 Hz, OCHH), 4.32 (m, 1H, NCH), 3.53 (m, 2H, NCH2), 1.91–2.33 (m, 4H, CH2CH2).

Scheme 1.

The phosphorus oxychloride in dichloromethane was added over 10 min to the solution of N-benzyloxycarbonyl-l-prolinamide in dry pyridine at approximately –5 to –10°C under N2. The mixture was stirred at approximately –5 to –10°C for 1 h, and then it was poured on ice and extracted with saturated cupric sulfate solution and saturated sodium chloride solution, dried over MgSO4, and evaporated in vacuo to afford N-benzyloxycarbonyl-l-proline nitrile as a pale-yellow oil. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ7.96 (d, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.90 (t, 1H, J = 7.2 Hz, Ar-H), 7.77 (t, 2H, J = 8.0 Hz, Ar-H), 4.80 (t, 1H), 3.28–3.36 (m, 2H), 2.34–2.52 (m, 1H), 2.04–2.20 (m, 3H).

The mixture of N-benzyloxycarbonyl-l-prolinamide (1 eq), sodium azide (1.04 eq), ammonium chloride (1.1 eq), and dry dimethylformamide was stirred at ≈90–95°C under N2 for 6 h. The mixture was poured onto ice, acidified to pH 2 with diluted HCl, and extracted with CHCl3. The CHCl3 layer was washed with water and saturated sodium chloride, dried over Na2SO4, and evaporated in vacuo to afford crude material. This crude material was purified with silica gel chromatography to pure N-benzyloxycarbonyl pyrrolidin-l-2-yl-1H-tetrazole. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ7.37 (s, 5H), 5.20 (m, 3H), 3.55 (m, 2H), 2.06–2.34 (m, 4H).

N-benzyloxycarbonyl pyrrolidin-l-2-yl-1H-tetrazole and 10% palladium on charcoal in acetic acid/water (9:1) was stirred under H2 at room temperature (rt) for 4 h. The mixture was filtered through Celite, and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to afford crude l-pyrrolidine-2-yl-1H-tetrazole, which was recrystallized from acetic acid and diethyl ether.  –8.57° (c = 0.63, MeOH); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ4.82 (m, 2H), 3.33 (m, 2H), 2.39 (m, 1H), 2.02–2.41 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) δ159.6, 56.2, 46.6, 31.1, 24.8.

–8.57° (c = 0.63, MeOH); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ4.82 (m, 2H), 3.33 (m, 2H), 2.39 (m, 1H), 2.02–2.41 (m, 3H); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) δ159.6, 56.2, 46.6, 31.1, 24.8.

General Procedure for the O-Nitroso Aldol Reaction of Ketone to Nitrosobenzene Using l-Pyrrolidine-Based Tetrazole Catalyst (3f). To an rt solution of pyrrolidine-based tetrazole catalyst (5 mol %) and ketone (1.5 mmol, 3 eq) in DMSO (1 ml) was added the solution of nitrosobenzene (0.5 mmol, 1 eq) in DMSO (1 ml) dropwise for 1 h. The resulting mixture was stirred at this temperature until the nitrosobenzene was consumed completely (1 h), as determined by TLC (hexane/ethyl acetate = 3:1). The reaction mixture then was poured into iced, saturated NH4Cl solution. The aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (20 ml, three times). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 with cooling, and concentrated under reduced pressure after filtration. The residual crude product was chromatographed on a two-layered column filled with Florisil (upper layer) and silica gel (lower layer) using a mixture of ethyl acetate and hexane as the eluant to give the product.

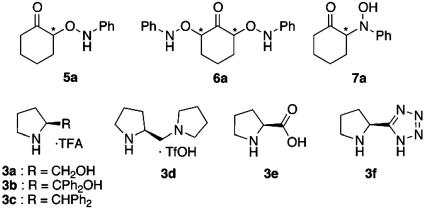

2-(N-phenyl Aminooxy) Cyclohexanone, 5a (Table 1, entry 1). Purification by flash-column chromatography with elution by hexane/ethyl acetate (10:1) provided as yellowish powder. TLC Rf = 0.30 (3:1 hexane/ethyl acetate);  (c = 3.23, CHCl3); IR (CHCl3) 3,021, 2,951, 2,872, 1,722, 1,603, 1,495, 1,132, 1,100, 1,073, 1,028, 928 cm–1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ7.82 (s, 1H, NH), 7.25 (t, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 6.94 (t, 3H, J = 8.1 Hz, Ar-H), 4.35 (q, 1H, J = 6.0 Hz, CH), 2.34–2.48 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.00–2.02 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.71–1.79 (m, 4H, CH2); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ209.9, 148.0, 128.8 (2C), 122.0, 114.3 (2C), 86.2, 40.8, 32.5, 27.2, 23.7; Anal. Calcd for C12H15NO2: C, 70.22; H, 7.37; N, 6.82. Found: C, 70.22; H, 7.42; N, 6.91. Enantiomeric excess (ee) was determined by HPLC with a Chiralcel AD column (40:1 hexane/2-propanol), 1.0 ml/min; major enantiomer tr = 34.3 min; minor enantiomer tr = 28.1 min.

(c = 3.23, CHCl3); IR (CHCl3) 3,021, 2,951, 2,872, 1,722, 1,603, 1,495, 1,132, 1,100, 1,073, 1,028, 928 cm–1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ7.82 (s, 1H, NH), 7.25 (t, 2H, J = 8.4 Hz, Ar-H), 6.94 (t, 3H, J = 8.1 Hz, Ar-H), 4.35 (q, 1H, J = 6.0 Hz, CH), 2.34–2.48 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.00–2.02 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.71–1.79 (m, 4H, CH2); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 75 MHz) δ209.9, 148.0, 128.8 (2C), 122.0, 114.3 (2C), 86.2, 40.8, 32.5, 27.2, 23.7; Anal. Calcd for C12H15NO2: C, 70.22; H, 7.37; N, 6.82. Found: C, 70.22; H, 7.42; N, 6.91. Enantiomeric excess (ee) was determined by HPLC with a Chiralcel AD column (40:1 hexane/2-propanol), 1.0 ml/min; major enantiomer tr = 34.3 min; minor enantiomer tr = 28.1 min.

Table 1.

| Entry | Catalyst (mol %) | Time | Yield, %* | 5a/6a/7a† | ee of 5a, %‡ | (Conf.)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3a (5) | 1 day | <1 | |||

| 2 | 3b (5) | 1 day | <1 | |||

| 3 | 3c (5) | 1 day | <1 | |||

| 4 | 3d (5) | 1 h | 4 | >99/-/- | 37 | (S) |

| 5 | 3e (5) | 1 h | 35 | 98/2/- | >99 | (R) |

| 6 | 3f (5) | 1 h | 94 | >99/-/- | >99 | (R) |

| 7 | 3f (3) | 1 h | 72 | >99/-/- | >99 | (R) |

| 8 | 3f (2) | 1 h | 50 | >99/-/- | >99 | (R) |

Reactions were conducted with a catalytic amount of 3, 1.0 eq of nitrosobenzene, and 3 eq of cyclohexanone (4a) in DMSO at room temperature.

Isolated yield.

Determined by yield of each isolated isomer.

Determined by HPLC and Chiralpak ad (see supporting information).

Determined after conversion to the corresponding diol (see Supporting Text).

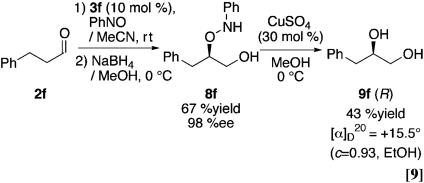

General Procedure for the O-Nitroso Aldol Reaction of Aldehyde to Nitrosobenzene Using l-Pyrrolidine-Based Tetrazole Catalyst (3f). To an rt solution of pyrrolidine-based tetrazole catalyst (10 mol %) in acetonitrile (1 ml) was added nitrosobenzene (1 eq, 0.5 mmol) in one portion and stirred at rt for 10 min. To this green, heterogeneous solution then was added aldehyde (3 eq, 1.5 mmol) in one portion. The resulting mixture was stirred at this temperature until the nitrosobenzene was consumed completely (≈15–30 min), as determined by TLC (hexane/ethyl acetate = 2:1). Then, the reaction was transferred to a methanol suspension of NaBH4 at 0°C. After 20 min, the reaction mixture then was poured into a saturated NH4Cl solution. The aqueous layer was extracted with diethyl ether (20 ml, three times). The combined organic extracts were dried over Na2SO4 with cooling and concentrated under reduced pressure after filtration. The residual crude product was chromatographed on a column filled with silica gel using a mixture of ethyl acetate and hexane as the eluant to give the product.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of 3-Phenyl-propane-1,2-diol (9f). The solution of 2-N-phenyl aminooxy-3-phenylpropan-1-ol 8f (1 eq) MeOH (1 ml) was added to a methanol suspension of CuSO4 (0.3 eq) at 0°C and stirred at this temperature for 3 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by cooled brine (20 ml), and the aqueous layer was extracted with ethyl acetate (10 ml, three times). The combined organic extracts were washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 with cooling, and concentrated under reduced pressure after filtration. The residual crude product was chromatographed on a silica gel using a mixture of ethyl acetate and hexane as the eluant to give the product.

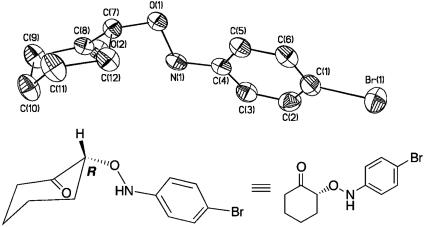

Determination of Absolute Configuration 5a. Basic data of x-ray structure are provided in Data Set 1 and Figs. 4–7, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. The reduction to diol for determination of absolute configuration was also attempted by using cyclohexanone under the 5 mol % of 3f as follows: after the nitroso aldol reaction, the treatment of CuSO4 in MeOH to afford α-hydroxy ketone, followed by reduction with NaBH4 in MeOH or the reduction with NaBH4 in MeOH for transformation of aminooxy alcohol, followed by N—O cleavage using Adam's catalyst. Unfortunately, however,

|

|

both cases could not provide enough pure trans-1,2-cyclohexanediol to compare with absolute configuration in the literature.

Results and Discussion

Reaction of nitrosobenzene with pyrrolidine enamine in benzene at 0°C generated a new intermediate 1, which was converted to the second intermediate 2 by the exposure of acetic acid. The intermediate 2 was able to be transformed to the aminooxy ketone after usual work-up (Fig. 1). Various solvents and temperature combination were examined for this transformation, and DMSO emerged as the most suitable solvent to afford aminooxy ketone without production of azoxy dimer by-product. 1H NMR study in DMSO-d6 revealed a downfield shift of enamine olefin proton (J = 3.9 Hz) from δ4.1 to 4.4 ppm, one

|

proton broad singlet at δ8.2 ppm due to the aminooxy NH, and one proton triplet (J = 4.5 Hz) at pyrrolidine α-position at δ4.3 ppm, which indicate the formation of the intermediate 1. After treatment with acetic acid, complete conversion to a single new species is observed. This species is assigned as the iminium salt 2 (34, 35) based on the significant downfield shift from δ4.3 to

|

5.3 ppm (α-proton of iminium group) and disappearance of the δ4.4 ppm triplet. After work-up, the iminium salt 2 can be hydrized to α-aminooxy ketone (detailed spectrum data are provided in Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Fig. 1.

Plausible structure of the intermediate.

This information, together with the reported proline-catalyzed reactions of nitrosobenzene with aldehydes, prompted us to test the possible enantioselective O-nitroso aldol synthesis of cyclohexanone by using pyrrolidine-based Brønsted acid catalysts (26–29, 36–43). The results with various catalysts are summarized in Table 1 and Eq. 6 (44). The several kinds of substituted pyrrolidine-trifluoroacetic acid (3a–3c) were unable to catalyze nitroso aldol process after 1 day at rt. The diamine-protonic acid catalyst (3d) afforded O-adduct with S configuration but did not provide catalyst turnover. The proline (3e) and pyrrolidine-based tetrazole (3f) afforded a promising level of regioselection and enantioselection with R configuration for the O-nitroso aldol adduct. The tetrazole catalyst especially was shown to be more attractive from the higher reactivity. The difference of reactivity is clearly demonstrated by the following comparison experiments taking advantage of the complete enantioselectivity for aminooxy ketone (Eq. 7): under the 3 mol % l-pyrrolidine-based tetrazole and d-proline as a mixed catalyst, the O-nitroso aldol product was isolated in 81% yield, with 32% ee mainly from the tetrazole catalyst (R/S = 66:34).

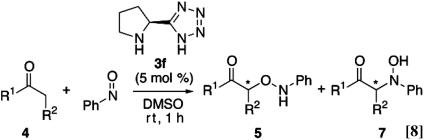

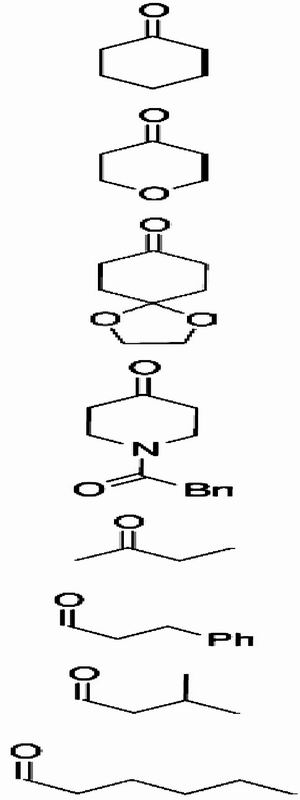

The scope of the O-nitroso aldol reaction was investigated further by using other ketones and aldehydes (Table 2 and Eq. 8). Optimal results were obtained with 5 mol % of l-pyrrolidine-tetrazole (3f) in the reaction of nitrosobenzene with an excess of cyclohexanone (5a: 94%, >99% ee). The other substituted cyclohexanones (4b, 4c, and 4d) also reacted smoothly in the presence of 3f (5 mol %) to afford O-adducts 5 in 87–97% yield and in >99% ee. When the acyclic ketone (4e) and aldehydes (4f–4h) were used, the enantioselectivities were still maintained in excellent level, but yields of O-nitroso aldol products were moderate due to production of N-adduct (7e) and azoxy dimer by-product. The use of 10–20 mol % catalyst, however, afforded a 67–75% yield.

Table 2. Scope of O-nitroso aldol reaction.

| Entry | 4 | Yield, %* | 5/7† | ee of 5, %‡ | (Conf.)§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

4a | 94 | >99/- | >99 | (R) |

| 2 | 4b | 87 | >99/- | >99 | ||

| 3 | 4c | 97 | >99/- | 99 | ||

| 4 | 4d | 95 | >99/- | >99 | ||

| 5¶ | 4e | 75 | 72/28 | >99 | ||

| 6** | 4f | 67∥ | >99/- | 98 | (R) | |

| 7†† | 4g | 65∥ | >99/- | 98 | ||

| 8** | 4h | 69∥ | >99/- | 98 |

Reactions were conducted with 5 mol % of 3f, 1.0 eq of nitrosobenzene, and 3 eq of 4 in DMSO at rt.

Isolated yield.

Determined by yield of each isolated isomer.

Determined by HPLC (Supporting Text).

Determined after conversion to the corresponding diol (Supporting Text).

Reaction was conducted with 20 mol % of 3f in DMSO at rt.

Determined by isolated yield of corresponding primary alcohol obtained after reduction of product.

Reactions were conducted with 10 mol % of 3f in MeCN at rt.

Reaction was conducted with 20 mol % of 3f in MeCN at rt.

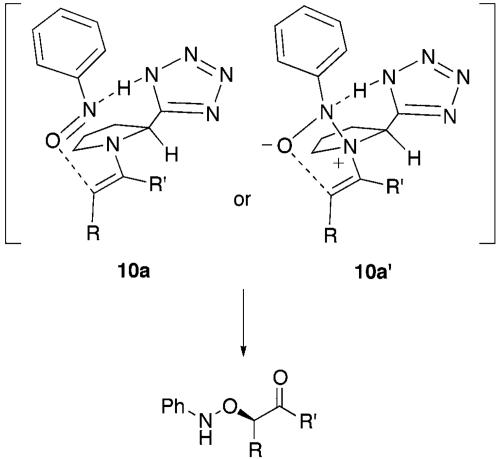

The absolute configuration of α-aminooxy compounds was determined by the x-ray structure of the product provided by the reaction of p-bromo nitrosobenzene and cyclohexanone (Fig. 2) and reduction to the corresponding diols derived from hydrocinnamaldehyde (Eq. 9; ref. 45) (see Experimental Procedures). This observation indicated the similar transition-state-proposed models for the proline-catalyzed aldol reaction. The most stable enamine conformer derived from ketone or aldehyde can be assigned as shown in Fig. 3 (46–50). Taking into consideration the basic properties of enamine or nitroso compound as both nucleophilic and electrophilic functions (51–53), the reaction of nitrosobenzene may proceed from the same side of tetrazole (or carboxylic acid) by either direct activation of nitrosobenzene by acidic proton (10a) or an indirect route via amine-nitrosobenzene complexation followed by rearrangement (10a′).

Fig. 2.

X-ray structure of the O-nitroso aldol adduct.

Fig. 3.

Plausible transition state in the enantioselective O-nitroso aldol process.

Conclusions

The O-nitroso aldol synthesis has been developed by using pyrrolidine-tetrazole catalyst not only for aldehydes but also ketones. With the appropriate Brønsted acidity in tetrazole catalyst, both high ees and reactivity were realized in catalytic reaction. Identification of clean and regioselective transformation of O-nitroso aldol adducts furnished from pyrrolidine enamine gave the essential information to achieve a catalytic enantioselective route by using chiral amine catalyst. We believe that this O-nitroso aldol synthesis offers an entry into pyrrolidine-based organic catalysis and delivers valuable information about the relationship between small amines and nitroso compounds.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ian M. Steele for x-ray crystallographic analysis; Yuhei Yamamoto for determination of absolute configuration; the editor for generous consideration concerning the absolute configuration; and Kazuaki Ishihara (Graduate School of Engineering, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan) for helpful discussion. Support for this research was provided by the Solution Oriented Research for Science and Technology project of the Japan Science and Technology Agency, National Institutes of Health Grant GM068433-01, and a grant from the University of Chicago.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: ee, enantiomeric excess; rt, room temperature.

References

- 1.Davis, F. A. & Haque, M. S. (1990) Adv. Oxygenated Processes 2, 61–116. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis, F. A. & Chen, B. C. (1992) Chem. Rev. (Washington, D.C.) 92, 919–934. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis, F. A. & Chen, B. C. (1995) in Houben-Weyl: Methods of Organic Chemistry, eds. Helmchen, G., Hoffmann, R. W., Mulzer, J. & Schaumann, E. (Thieme, Stuttgart), pp. 4497–5016.

- 4.Chen, B. C., Zhou, P. & Davis, F. A. (2001) in Asymmetric Oxidation Reactions, ed. Katsuki, T. (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford), pp. 37–50.

- 5.Becker, H. & Sharpless, K. B. (2001) in Asymmetric Oxidation Reactions, ed. Katsuki, T. (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford), pp. 81–104.

- 6.Zhou, P., Chen, B. C. & Davis, F. A. (2001) in Asymmetric Oxidation Reactions, ed. Katsuki, T. (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford), pp. 128–145.

- 7.Momiyama, N. & Yamamoto, H. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 6038–6039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Momiyama, N. & Yamamoto, H. (2002) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 41, 2986–2988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Momiyama, N. & Yamamoto, H. (2002) Org. Lett. 4, 3579–3582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis, J. W., Myers, P. L. & Ormerod, J. A. (1972) J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 20, 2521–2524. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitacco, G. & Valentin, E. (1982) in The Chemistry of Amino, Nitroso, Nitro and Related Groups, Supplement F2, ed. Patai, S. (Wiley, Chichester, U.K.), pp. 623–714.

- 12.Cook, A. G. (1988) in Enamines: Synthesis, Structure, and Reactions, ed. Cook, A. G. (Dekker, New York), pp. 1–101.

- 13.Hickmott, P. W. (1994) in The Chemistry of Enamines, ed. Rappoport, Z. (Wiley, Chichester), pp. 727–871.

- 14.Hickmott, P. W. (1982) Tetrahedron 38, 1975–2050. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitesell, J. K. & Whitesell, M. A. (1983) Synthesis, 517–536.

- 16.Takazawa, O., Kogami, K. & Hayashi, K. (1985) Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 58, 2427–2428. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gunawardena, G. U., Arif, A. M. & West, F. G. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119, 2066–2067. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kempf, B., Hampel, N., Ofial, A. R. & Mayr, H. (2003) Chem. Eur. J. 9, 2209–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown, S. P., Brochu, M. P., Sinz, C. J. & MacMillan, D. W. C. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 10808–10809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong, G. (2003) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 42, 4247–4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi, Y., Yamaguchi, J., Hibino, K. & Shoji, M. (2003) Tetrahedron Lett. 44, 8293–8296. [Google Scholar]

- 22.List, B. (2001) Synlett, 1675–1686.

- 23.List, B. (2002) Tetrahedron 58, 5573–5590. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Northrup, A. B. & MacMillan, D. W. C. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 6798–6799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duthaler, R. O. (2003) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 42, 975–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saito, S., Nakadai, M. & Yamamoto, H. (2001) Synlett, 1245–1248.

- 27.Nakadai, M., Saito, S. & Yamamoto, H. (2002) Tetrahedron 58, 8167–8177. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torii, H., Nakadai, M., Ishihara, K., Saito, S. & Yamamoto, H. (2004) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Cobb, A. J. A., Shaw, D. M. & Ley, S. V. (2004) Synlett, 558–560.

- 30.Bøgevig, A., Sundén, H. & Córdova, A. (2004) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 43, 1109–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayashi, Y., Yamaguchi, J., Sumiya, T. & Shoji, M. (2004) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 43, 1112–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pozdnev, V. F. (1995) Tetrahedron Lett. 36, 7115–7118. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Almquist, R. G., Chao, W. & White, C. J. (1985) J. Med. Chem. 28, 1067–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leonard, N. J. & Paukstelis, J. V. (1963) J. Org. Chem. 28, 3021–3024. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiu, K., Peng, S., Cheng, M., Wang, S. & Liao, F. (1993) J. Organomet. Chem. 461, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bui, T. & Barbas, C. F., III. (2000) Tetrahedron Lett. 41, 6951–6954. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bogevig, A., Kumaragurubaran, N. & Jørgensen, A. K. (2002) Chem. Commun., 620–621. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Halland, N., Hazell, R. G. & Jørgensen, K. A. (2002) J. Org. Chem. 67, 8331–8338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Juhl, K. & Jørgensen, K. A. (2003) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 42, 1498–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramachary, D. B., Chowdari, N. S. & Barbas, C. F., III. (2003) Synlett, 1910–1914.

- 41.Melchiorre, P. & Jørgensen, K. A. (2003) J. Org. Chem. 68, 4151–4157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mase, N., Tanaka, F. & Barbas, C. F., III. (2003) Org. Lett. 5, 4369–4372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Notz, W., Tanaka, F., Watanabe, S., Chowdari, N. S., Turner, J. M., Thayumanavan, R. & Barbas, C. F., III. (2003) J. Org. Chem. 68, 9624–9634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freundler, P. & Julliard (1909) Compt. Rend. 148, 289–290. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bergstein, W. A., Kleemann, A. J. & Martens, J. (1981) Synthesis, 76–78.

- 46.Bahmanyar, S. & Houk, K. N. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 11273–11283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bahmanyar, S. & Houk, K. N. (2001) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 12911–12912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoang, L., Bahmanyar, S., Houk, K. N. & List, B. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 16–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bahmanyar, S., Houk, K. N., Martin, H. J. & List, B. (2003) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 2475–2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bahmanyar, S. & Houk, K. N. (2003) Org. Lett. 5, 1249–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stork, G., Brizzolara, A., Landesman, H., Szmuszkovicz, J. & Terrell, R. (1963) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85, 207–222. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kupper, R. & Michejda, C. J. (1980) J. Org. Chem. 45, 2919–2921. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cook, G. & Waddle, J. L. (2003) Tetrahedron Lett. 44, 6923–6925. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.