Abstract

Objective

To evaluate perceived weight gain in women using contraception and determine the validity of self-reported weight gain.

Study Design

We analyzed data from new contraceptive method users who self-reported weight change at 3, 6, and 12-months after enrollment. We examined a subgroup of participants with objective weight measurements at baseline and 12-months to test the validity of self-reported weight gain.

Results

Thirty-four percent (1,407/4133) of participants perceived weight gain. Compared to copper intrauterine device users, implant users [relative risk (RR)=1.29, 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.10–1.51] and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) users [RR=1.37, 95% CI, 1.14–1.64] were more likely to report perceived weight gain. Women who perceived weight gain experienced mean weight gain of 10.3 pounds. The sensitivity and specificity of perceived weight gain were 74.6% and 84.4%, respectively.

Conclusions

In most women, perceived weight gain represents true weight gain. Implant and DMPA users are more likely to perceive weight gain among contraception users.

Keywords: contraception, perceived weight gain, reproductive-age women, weight gain

INTRODUCTION

Reported weight gain is one of the main reasons why women are not satisfied with their contraceptive method.1, 2 In clinical studies evaluating the subdermal implant, 13.7% of users reported weight gain as an adverse effect of the method and 2.3% reported weight gain as the reason for having their implant removed (Implanon package insert. Roseland, NJ: Organon USA Inc; 2006). However, perceived weight gain is rarely validated with objective measures.

The literature regarding contraception and objective measurements of weight gain has focused on certain methods, mainly oral contraceptives and depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Currently, DMPA is the only contraceptive method consistently associated with significant weight gain.3–5 However, the literature fails to address how women perceive various contraceptive methods to affect their weight, and if their perception of weight gain is accurate.

Regardless of accuracy, a woman’s perception of her weight while using a contraceptive method may be just as important as the number on a scale, particularly regarding method satisfaction and continuation. In a study on self-weighing frequency and weight loss, 20% of adults at baseline reported they never weigh themselves, and 40% reported weighing themselves less than once a week.6 Therefore, many Americans rely on perceived weight as a method of weight assessment.

The purpose of this analysis is to evaluate perceived weight gain during the first 12 months after women started a new contraceptive method and to determine the validity of self-reported weight gain. To test the accuracy of perceived weight gain, we examined a subset of women who also received height and weight measurements at baseline and 12-months post-enrollment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a secondary analysis of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project. CHOICE is a prospective cohort study developed to promote the use of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). The study provides contraception for 2–3 years at no-cost to 9,256 women in the St. Louis area in an effort to reduce unintended pregnancies in our region. English or Spanish speaking women between 14 and 45 years were eligible for the study if they: 1) resided in the study’s designated recruitment region; 2) were willing to start a new method of reversible contraception or were currently not using any method; 3) did not desire to become pregnant for at least 12 months; and 4) were sexually active with a male partner or planning to become sexually active in the next 6 months. Women were excluded if they had a history of tubal sterilization or hysterectomy. Study enrollment began in August 2007 and ended in September 2011.

All enrolled participants received contraceptive counseling at one of the designated recruitment sites, which included the university-based clinic, two abortion clinics, and several community-based clinics. Counseling sessions at the university-based clinic presented women with all reversible contraceptive methods and their associated effectiveness, side effects, benefits and risks to help participants make an informed decision. Counseling sessions at the remaining clinics were based upon what was usual contraceptive counseling for that clinic location. Also during the baseline visit, a comprehensive assessment was performed to collect demographic and reproductive history information, screen for sexually transmitted infections, and measure height and weight. The woman’s baseline body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2 and categorized into one of the following BMI groups: underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), or obese (≥30).

We performed telephone interviews using standardized survey instruments at 3 and 6 months post-enrollment, and every six months for the duration of follow-up. Participants were compensated with a $10.00 gift card at each interview. During the follow-up surveys, participants were asked to self-report any changes in their weight. Specifically, the survey question asked, “Since we last spoke, has your weight changed by 5 pounds or more?” If the participant answered “yes,” she was further asked, “Did you (a) gain weight, (b) lose weight, (c) both gain and lose weight, or (d) you don’t know?” This question was not included until a revised version of the survey introduced on July 1, 2008. Therefore, only participants that answered this question are included in this analysis.

For this analysis, we evaluated women’s perceived weight change during the first 12 months of starting a new contraceptive method using data from their 3, 6, and 12-month surveys. A participant was excluded from the analysis if we could not reach a definite conclusion regarding her direction of perceived weight change over 12 months. For example, a participant was excluded if she was missing a response to the question above in any of the 3, 6, or 12-month surveys or had responded “yes” to weight change but was missing a response to how her weight had changed (i.e. weight gain or loss). In addition, if a participant ever reported “both weight gain and weight loss” or “don’t know” to the question “how did your weight change?” in any of the 3, 6, or 12-month follow-up surveys, she was excluded from the analysis sample as we could not determine the direction (gain or loss) of her weight change. Finally, if a participant’s combined responses of all three surveys included any combination of “gain” and “loss,” she was excluded because we could not determine her net sum of perceived weight change as we had no way of knowing which weight change was the most prominent.

We defined three groups: 1) perceived weight gain; 2) perceived no weight change; and 3) perceived weight loss. Group 1 (perceived weight gain) included any participant who reported “weight gain” in at least one of her 3, 6, or 12-month surveys and reported “no change” at all of the remaining 3, 6, or 12-month survey(s). Group 2 (perceived no weight change) included participants who, at all of the 3, 6, and 12-month follow-up surveys, responded, “No, my weight has not changed by 5 pounds or more since we last spoke.” Group 3 (perceived weight loss) included any participant who reported “weight loss” in at least one of her 3, 6, or 12-month surveys and reported “no change” at all of the remaining 3, 6, or 12-month survey(s).

All women enrolled in CHOICE on or after June 15, 2010 were offered eligibility screening and, if eligible, enrolled in a separate substudy to objectively assess 12-month weight change with progestin-only methods or the copper IUD. Eligibility for this substudy included: 1) CHOICE enrollment at the university-based clinic (in order to retain consistency in scale used to assess weight); 2) 18 years of age or older; 3) using the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS), copper T380A IUD, subdermal implant, or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) as current method; 4) continued use of one of the above methods for at least 11 months; and 5) willingness to return to the university-based clinic for a 12-month visit for an objective weight assessment. At the time of data analysis, 415 women had enrolled and completed this substudy of objectively measured weight change. We calculated the participant’s observed weight change by subtracting her recorded weight at baseline from the recorded weight at her 12-month follow-up. The observed weight change was classified as: a ‘gain’ if the calculated weight change was a ≥5 pound increase; ‘no change’ if the calculated weight change was less than a 5-pound change in either direction; and a ‘loss’ if the calculated weight change was a ≥5 pound decrease. We chose a 5-pound change to be consistent with our survey instrument. The observed weight change categories ‘gain,’ ‘no change,’ and ‘loss’ were then compared with the perceived weight change groups (1, 2, and 3) as previously defined. To estimate sensitivity, specificity, agreement, and relative risk calculations, we combined group 2 (perceived no weight change) and group 3 (perceived weight loss) to create a dichotomous variable for perceived weight gain: ‘yes’ (perceived weight gain) or ‘no’ (no perceived weight gain). We created a similar variable for objective weight gain, where the no weight gain group included the measured “no change” and “weight loss” groups.

The CHOICE protocol and substudy described above were approved by the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine Human Research Protection Office. The methodic details of the Contraceptive CHOICE Project have been published in a separate report.7

Statistical analyses

We compared the baseline demographic and behavioral characteristics among the three perceived weight change groups—gain, no change, and loss—in both the CHOICE analysis sample and our substudy sample using chi-square or Fisher exact test where appropriate. We compared the mean objective weight change of the three perceived weight gain groups in the substudy using a one-way ANOVA test. We calculated a Kappa statistic to evaluate the agreement between objective and perceived weight gain. We calculated the sensitivity and specificity of perceived weight gain compared to the gold standard of objectively measured weight gain. We also calculated the relative risk (RR) of perceived weight gain by contraceptive methods and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from Poisson regression using the SAS GENMOD procedure. This approach provides an unbiased estimate of the relative risk in the case of common outcomes (greater than 10%). Confounding was defined as a greater than 10% relative change in the association between perceived weight gain and method choice with or without the potential confounding factor in the model. Confounders were included in the final model to obtain an adjusted RR of perceived weight gain among contraceptive methods. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.2 software. The significance level alpha was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Of the 7,977 CHOICE participants who reached 12-months at the time of data analysis, 4,133 women met our inclusion criteria. Among the 3,844 women excluded, 2968 had missing data regarding the weight question or the specific direction of weight change and 1,146 reported both weight “gain” and “loss”. We found no significant differences in demographic and behavioral characteristics between the analysis sample and the women who were excluded because of inclusion criteria or inability to reach a definite conclusion regarding their weight change. Of the 4,133 women in the analysis sample, 1,407 (34.0%) perceived weight gain, 1,634 (39.5%) perceived no weight change, and 1,092 (26.4%) perceived weight loss.

Table 1 displays the demographic and behavioral characteristics of the analysis sample and the three perceived weight change groups: gain, no change, and loss. Women who perceived weight gain were significantly more likely to be African American, parous, uninsured, and less educated. The participants in the weight gain group were also more likely to have trouble paying for basic necessities and receive public assistance. General health was highest among those who reported no perceived weight change. Compared to women who were normal or underweight at baseline (n=1,882), women who were overweight or obese at baseline (n=2,251) were more likely to report perceived weight gain (36.7% versus 30.9%) and weight loss (30.5% versus 21.5%), and less likely to report no weight change (32.8% versus 47.6%).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristics | Analysis Sample (n=4133) | Perceived Weight Gain (n=1407) | Perceived No Weight Change (n=1634) | Perceived Weight Loss (n=1092) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)* | .042 | ||||

| <21 | 851 (20.6) | 300 (21.3) | 342 (20.9) | 209 (19.1) | |

| 21–25 | 1624 (39.3) | 511 (36.3) | 670 (41.0) | 443 (40.6) | |

| >25 | 1658 (40.1) | 596 (42.4) | 622 (38.1) | 440 (40.3) | |

| Race* | <.001 | ||||

| Black | 1989 (48.1) | 823 (58.5) | 725 (44.4) | 441 (40.4) | |

| White | 1810 (43.8) | 472 (33.5) | 778 (47.6) | 560 (51.3) | |

| Other | 334 (8.1) | 112 (8.0) | 131 (8.0) | 91 (8.3) | |

| Marital Status* | .011 | ||||

| Single | 2432 (58.9) | 845 (60.1) | 972 (59.6) | 615 (56.3) | |

| Living with partner | 900 (21.8) | 289 (20.6) | 345 (21.1) | 266 (24.4) | |

| Married | 551 (13.3) | 169 (12.0) | 234 (14.3) | 148 (13.5) | |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 247 (6.0) | 103 (7.3) | 81 (5.0) | 63 (5.8) | |

| Insurance* | <.001 | ||||

| None | 1668 (40.6) | 641 (45.8) | 621 (38.2) | 406 (37.3) | |

| Private | 1873 (45.5) | 535 (38.3) | 806 (49.6) | 532 (48.9) | |

| Public | 571 (13.9) | 222 (15.9) | 199 (12.2) | 150 (13.8) | |

| Education* | <.001 | ||||

| High school diploma/GED or less | 1363 (33.0) | 546 (38.8) | 490 (30.0) | 327 (30.0) | |

| Some College | 1662 (40.2) | 572 (40.7) | 639 (39.1) | 451 (41.3) | |

| College degree or graduate school | 1107 (26.8) | 288 (20.5) | 505 (30.9) | 314 (28.7) | |

| Trouble paying for basic expenses* | <.001 | ||||

| No | 2608 (63.2) | 771 (54.9) | 1138 (69.8) | 699 (64.0) | |

| Yes | 1519 (36.8) | 633 (45.1) | 493 (30.2) | 393 (36.0) | |

| Receiving Public Assistance* | <.001 | ||||

| No | 2680 (64.9) | 816 (58.1) | 1136 (69.6) | 728 (66.7) | |

| Yes | 1448 (35.1) | 589 (41.9) | 496 (30.4) | 363 (33.3) | |

| Parity* | <.001 | ||||

| Nulliparous | 2030 (49.1) | 608 (43.2) | 867 (53.1) | 555 (50.8) | |

| Parous | 2103 (50.9) | 799 (56.8) | 767 (46.9) | 537 (49.2) | |

| Baseline BMI (kg/m2)* | <.001 | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 211 (5.1) | 45 (3.2) | 125 (7.7) | 41 (3.8) | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 1671 (40.4) | 537 (38.2) | 770 (47.1) | 364 (33.3) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 1040 (25.2) | 376 (26.7) | 360 (22.0) | 304 (27.8) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 1211 (29.3) | 449 (31.9) | 379 (23.2) | 383 (35.1) | |

| Baseline Method* | <.001 | ||||

| LNG IUS | 1892 (45.8) | 650 (46.2) | 705 (43.2) | 537 (49.2) | |

| Copper-IUD | 532 (12.9) | 156 (11.1) | 212 (13.0) | 164 (15.0) | |

| Implant | 651 (15.8) | 266 (18.9) | 233 (14.3) | 152 (13.9) | |

| DMPA | 282 (6.8) | 130 (9.3) | 102 (6.2) | 50 (4.6) | |

| Pills, Patch, Ring | 774 (18.7) | 204 (14.5) | 381 (23.3) | 189 (17.3) | |

| General Health (Baseline)* | <.001 | ||||

| Excellent | 1199 (29.1) | 352 (25.1) | 545 (33.4) | 302 (27.7) | |

| Very good | 1681 (40.7) | 549 (39.2) | 659 (40.4) | 473 (43.3) | |

| Good | 1016 (24.6) | 399 (28.4) | 365 (22.3) | 252 (23.1) | |

| Fair | 215 (5.2) | 94 (6.7) | 61 (3.7) | 60 (5.5) | |

| Poor | 15 (0.4) | 8 (0.6) | 3 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | |

| General Health (12 months)* | <.001 | ||||

| Excellent | 1012 (24.6) | 267 (19.0) | 475 (29.2) | 270 (24.8) | |

| Very good | 1651 (40.1) | 522 (37.2) | 689 (42.4) | 440 (40.3) | |

| Good | 1115 (27.1) | 433 (30.9) | 383 (23.6) | 299 (27.4) | |

| Fair | 322 (7.8) | 167 (11.9) | 75 (4.6) | 80 (7.3) | |

| Poor | 19 (0.4) | 14 (1.0) | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) |

Significant at alpha level of .05

P-value calculated using Fisher Exact Test. All other p-values calculated using χ2 test.

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

GED, general education development test; DMPA, Depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate; IUC, intrauterine contraceptive; LNG, levonorgestrel; BMI, Body Mass Index.

Some n-values do not sum to total number in column heading, which accounts for missing responses.

Table 2 presents the demographic and behavioral characteristics for the subgroup of participants who received an objective measurement of weight change at baseline and 12 months. Of the 415 women who completed this assessment, 281 participants met the inclusion criteria. We found no differences when we compared excluded participants to those included in the analysis sample. Black race, lower socioeconomic status, higher baseline BMI, and use of DMPA or the implant were significantly associated with perceived weight gain.

Table 2.

Baseline demographic and behavioral characteristics of women with objective weight measurements at baseline and 12 months.

| Characteristics | Substudy Analysis Sample (n=281) | Perceived Weight Gain (n=111) | Perceived No Weight Change (n=100) | Perceived Weight Loss (n=70) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | .836 | ||||

| <21 | 37 (13.2) | 15 (13.5) | 15 (15.0) | 7 (10.0) | |

| 21–25 | 110 (39.1) | 45 (40.5) | 39 (39.0) | 26 (37.1) | |

| >25 | 134 (47.7) | 51 (46.0) | 46 (46.0) | 37 (52.9) | |

| Race* | <.001† | ||||

| Black | 141 (50.2) | 75 (67.6) | 40 (40.0) | 26 (37.2) | |

| White | 128 (45.5) | 35 (31.5) | 53 (53.0) | 40 (57.1) | |

| Other | 12 (4.3) | 1 (0.9) | 7 (7.0) | 4 (5.7) | |

| Marital Status | .413† | ||||

| Single | 156 (55.5) | 64 (57.7) | 57 (57.0) | 35 (50.0) | |

| Living with partner | 66 (23.5) | 28 (25.2) | 17 (17.0) | 21 (30.0) | |

| Married | 40 (14.2) | 12 (10.8) | 18 (18.0) | 10 (14.3) | |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 19 (6.8) | 7 (6.3) | 8 (8.0) | 4 (5.7) | |

| Insurance* | .011 | ||||

| None | 90 (32.0) | 44 (39.6) | 28 (28.0) | 18 (25.7) | |

| Private | 151 (53.7) | 51 (46.0) | 64 (64.0) | 36 (51.4) | |

| Public | 40 (14.2) | 16 (14.4) | 8 (8.0) | 16 (22.9) | |

| Education | .266 | ||||

| High school diploma/GED or less | 65 (23.1) | 30 (27.1) | 19 (19.0) | 16 (22.9) | |

| Some College | 110 (39.2) | 44 (39.6) | 35 (35.0) | 31 (44.3) | |

| College degree or graduate school | 106 (37.7) | 37 (33.3) | 46 (46.0) | 23 (32.9) | |

| Trouble paying for basic expenses* | .004 | ||||

| No | 176 (62.9) | 56 (50.9) | 70 (70.0) | 50 (71.4) | |

| Yes | 104 (37.1) | 54 (49.1) | 30 (30.0) | 20 (28.6) | |

| Receiving Public Assistance* | .001 | ||||

| No | 180 (64.1) | 60 (54.1) | 78 (78.0) | 42 (60.0) | |

| Yes | 101 (35.9) | 51 (45.9) | 22 (22.0) | 28 (40.0) | |

| Parity * | .018 | ||||

| Nulliparous | 129 (45.9) | 46 (41.4) | 57 (57.0) | 26 (37.1) | |

| Parous | 152 (54.1) | 65 (58.6) | 43 (43.0) | 44 (62.9) | |

| Baseline BMI by CDC Classifications (kg/m2)* | .035† | ||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 9 (3.2) | 2 (1.8) | 5 (5.0) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 121 (43.0) | 39 (35.2) | 55 (55.0) | 27 (38.6) | |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 64 (22.8) | 28 (25.2) | 19 (19.0) | 17 (24.3) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 87 (31.0) | 42 (37.8) | 21 (21.0) | 24 (34.3) | |

| Baseline Method* | .004† | ||||

| LNG IUS | 99 (35.2) | 38 (34.2) | 29 (29.0) | 32 (45.7) | |

| Copper-IUD | 73 (26.0) | 18 (16.2) | 35 (35.0) | 20 (28.6) | |

| Implant | 78 (27.8) | 37 (33.4) | 26 (26.0) | 15 (21.4) | |

| DMPA | 31 (11.0) | 18 (16.2) | 10 (10.0) | 3 (4.3) | |

| General Health | .598† | ||||

| Excellent | 77 (27.4) | 34 (30.6) | 25 (25.0) | 18 (25.7) | |

| Very good | 123 (43.8) | 50 (45.1) | 45 (45.0) | 28 (40.0) | |

| Good | 73 (26.0) | 23 (20.7) | 28 (28.0) | 22 (31.4) | |

| Fair | 7 (2.5) | 4 (3.6) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Poor | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| General Health at 12 months | .381† | ||||

| Excellent | 67 (24.0) | 21 (19.1) | 28 (28.0) | 18 (26.1) | |

| Very good | 124 (44.4) | 48 (43.6) | 42 (42.0) | 34 (49.3) | |

| Good | 71 (25.5) | 34 (30.9) | 25 (25.0) | 12 (17.4) | |

| Fair | 16 (5.7) | 7 (6.4) | 4 (4.0) | 5 (7.2) | |

| Poor | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Objective Weight* | <.001† | ||||

| Gain | 114 (40.6) | 85 (76.6) | 26 (26.0) | 3 (4.3) | |

| No Change | 99 (35.2) | 21 (18.9) | 56 (56.0) | 22 (31.4) | |

| Loss | 68 (24.2) | 5 (4.5) | 18 (18.0) | 45 (64.3) | |

| Mean WT Change (lbs)* | 2.2 ±12.2 | 10.3 ±9.9 | 1.5 ±8.1 | −9.5 ±10.5 | <.001‡ |

Significant at alpha level of .05

P-value calculated using one-way ANOVA

P-value calculated using Fisher Exact Test. All other p-values calculated using χ2 test.

Data are n (%) or mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise specified.

GED, general education development test; DMPA, Depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate; IUC, intrauterine contraceptive; LNG, levonorgestrel. BMI, Body Mass Index.

Some n-values do not sum to total number in column heading, which accounts for missing responses.

The mean weight change over 12 months for the total subset of women with objective weight change assessment was a 2.2 pound increase. The three perceived weight change groups—gain, no change, and loss—experienced a mean weight change of 10.3 pounds gained, 1.5 pounds gained, and 9.5 pounds lost, respectively (P<.001). Of the 114 women who objectively gained 5 pounds or more during the 12 month period, 85 perceived weight gain. Conversely, among the 167 who did not gain ≥5 pounds, 141 perceived no weight gain. Therefore, the sensitivity and specificity of perceived weight gain was 74.6% (85/114) and 84.4% (141/167), respectively. Additionally, we calculated a Kappa statistic to measure the agreement between perceived weight gain and actual weight gain. The tests demonstrated moderate to good agreement (Kappa=0.59, P<.0001). The positive predictive value for perceived weight gain was 77%.

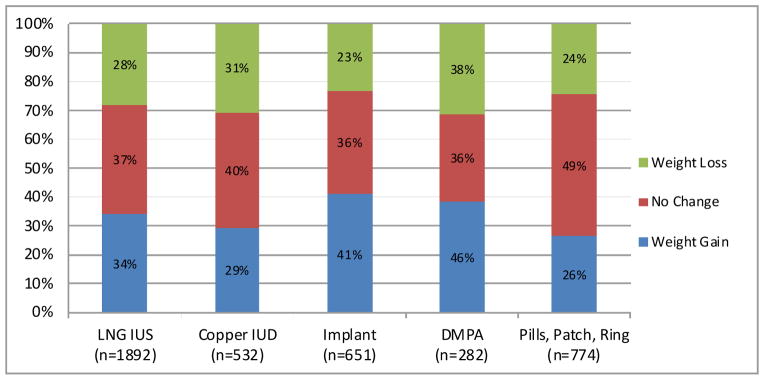

Figure 1 presents perceived weight change by contraceptive method. Each bar represents the total number of women using the specified method at baseline. The subdermal implant and DMPA showed the most perceived weight gain of all reversible methods analyzed. Forty-one percent of implant users and forty-six percent of DMPA users perceived weight gain of 5 pounds or more. Table 3 shows the crude and adjusted relative risk of perceived weight gain for each contraceptive method compared to the copper IUD. After adjusting for race, implant (RR=1.29, 95% CI: 1.10, 1.51) and DMPA (RR=1.37, 95% CI: 1.14–1.64) users were significantly more likely to perceive weight gain compared to copper IUD users. LNG-IUS, pill, patch, and ring users were no more likely to perceive weight gain compared to copper IUD users.

Figure 1.

Percent of women reporting weight change by baseline contraceptive method

Table 3.

Risk of perceived weight gain and contraceptive method.

| Method | Relative risk (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusteda | |

| LNG IUS | 1.17 (1.01–1.35) | 1.13 (0.98–1.30) |

|

| ||

| Copper-IUD | Reference | Reference |

|

| ||

| Implant | 1.39 (1.18–1.63) | 1.29 (1.10–1.51) |

|

| ||

| DMPA | 1.57 (1.31–1.88) | 1.37 (1.14–1.64) |

|

| ||

| Pills, patch, ring | 0.90 (0.75–1.07) | 0.88 (0.74–1.05) |

CI, confidence interval.

Model adjusted for race.

COMMENT

We found perceived weight gain to be a reasonable measure of objective weight gain. Although not a perfect measure, most women (77%) who self-reported weight gain were objectively found to have gained 5 pounds or more over 12 months. In addition, participants who perceived weight gain were found to have gained an average of 8.8 pounds more over 12 months than the group that perceived no change (p < 0.001). Our results suggest that self-reported weight change may be a reasonable proxy for true weight gain, and may be a practical way for clinicians and epidemiologists to monitor patients’ weight changes. Pronk and colleagues also noted that self-reported weight is an acceptable alternative given circumstances where it is difficult or inefficient to obtain measured weight.8

Currently, over one-half of reproductive-age women in the United States have a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2, which, according to the CDC’s standard weight status categories, classifies them as overweight or obese.9 Similarly, 54.5% of women in our analysis had a BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 at baseline, placing them into the overweight or obese BMI categories. Over one-third (37%) of the overweight and obese women in our analysis perceived weight gain. This finding is alarming; in addition to already being at an unhealthy weight, many subsequently reported a weight gain of at least 5 pounds over twelve months. Our results indicate that this is true weight gain for most women.

Because of the many adverse physical and mental health effects that commonly accompany obesity, it is important for clinicians to be aware of their patients’ weight gains. It may be useful, as well as simple and cost-effective, to have women report perceived weight changes to their primary care provider at regular intervals. This perceived change may be a trigger for an objective assessment. If validated, the clinician may suggest weight loss strategies or consider screening for diseases associated with obesity, such as diabetes or hypertension.

We were interested in perceived weight gain and its association with certain contraceptive methods. We found that almost one-half of implant and DMPA users (40.9%, 46.1% respectively) perceived weight gain. As stated earlier, DMPA is the one method that has been consistently associated with significant weight gain in previous studies.3–5 To our knowledge, there are few studies addressing weight gain or perceived weight gain with the use of the etonogestrel implant. Future studies should determine if the subdermal implant is associated with the objective evidence of weight gain. Understanding that some contraceptive methods have higher rates of perceived weight gain could prove helpful to clinicians when counseling their patients. It also may be helpful for clinicians to understand that certain patient characteristics (e.g. race, social economic status, education, parity, baseline BMI, etc.) are more likely to be associated with perceived weight gain.

Strengths of our analysis include a relatively large sample size and a diverse sample in terms of race and socioeconomic status. Our population reflects the St. Louis population, but may not be generalizable to other U.S. populations. As a note of caution, the perceived weight gain group in Table 1 (n=1407) is ten times as large as the objective weight gain group in Table 2 (n=111). Thus, associations in the perceived weight gain group were more likely to be statistically significant (due to larger samples size and power); whereas, few associations were statistically significant in the objective weight gain group due to smaller sample size.

One limitation of our study includes the definition of perceived weight gain and loss. Since the survey question asked about weight change in intervals (since the participant’s last survey), and not since the woman started her method, it was challenging to clearly define self-reported weight change over 12 months. Women who reported both weight gain and weight loss during the 12 months were excluded from the analysis, even though their net weight change may have been greater than 5 pounds in either direction. In addition, participants were asked if they perceived a weight change of 5 pounds or more. Thus, a participant may have perceived a weight gain, but if it was less than 5 pounds, she reported no weight change. If the woman perceived a 3 or 4 pound weight gain at each of the surveys, she may have perceived an overall 9–12 pound weight gain over 12-months, yet, her responses placed her in the perceived no weight change group. Another limitation of our study is that CHOICE is an observational study, not a randomized trial; thus, there is still the potential for residual bias despite our efforts to control for confounding variables. Biological plausibility does support our findings. Finally, there is reason to believe that media may have influenced participants’ reports and their associations of weight gain with certain contraceptive methods. For example, DMPA has been widely reported to be associated with weight gain and many women are aware of this association; therefore, women using DMPA may have been more likely to report weight gain.

In conclusion, self-reported weight change is easy to obtain and in most women, represents true weight gain. The perception of weight gain is clinically important, because it may affect a woman’s satisfaction with her contraceptive method or influence a woman’s decision to continue use of the method. Future studies should consider interventions that can promote healthy weight control, especially in women at high-risk for weight gain, and should assess the relationship between perceived weight gain and contraceptive continuation and satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project is funded by the Susan T. Buffett Foundation. This research was also supported in part by grant K23HD070979 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD).

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Tessa Madden reports receiving speaking honoraria from Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Jeffrey Peipert reports serving as an etonorgestrel implant trainer. Fees for this service are paid to Washington University in St. Louis. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Reprints will not be made available.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bahamondes L, Pinho F, de Melo NR, Oliveira E, Bahamondes MV. Associated factors with discontinuation use of combined oral contraceptives. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 33:303–9. doi: 10.1590/s0100-72032011000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hani D, Imthurn B, Merki-Feld GS. Weight gain due to hormonal contraception: myth or truth? Gynakol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch. 2009;49:87–93. doi: 10.1159/000197907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berenson AB, Rahman M. Changes in weight, total fat, percent body fat, and central-to-peripheral fat ratio associated with injectable and oral contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:329, e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonny AE, Ziegler J, Harvey R, Debanne SM, Secic M, Cromer BA. Weight gain in obese and nonobese adolescent girls initiating depot medroxyprogesterone, oral contraceptive pills, or no hormonal contraceptive method. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:40–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pantoja M, Medeiros T, Baccarin MC, Morais SS, Bahamondes L, Fernandes AM. Variations in body mass index of users of depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate as a contraceptive. Contraception. 81:107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linde JA, Jeffery RW, French SA, Pronk NP, Boyle RG. Self-weighing in weight gain prevention and weight loss trials. Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:210–6. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF. The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 203:115, e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pronk NP, Crain AL, Vanwormer JJ, Martinson BC, Boucher JL, Cosentino DL. The Use of Telehealth Technology in Assessing the Accuracy of Self-Reported Weight and the Impact of a Daily Immediate-Feedback Intervention among Obese Employees. Int J Telemed Appl. 2011:909248. doi: 10.1155/2011/909248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman M, Berenson AB. Self-perception of weight gain among multiethnic reproductive-age women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 21:340–6. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]