Abstract

Non-invasive imaging can provide essential information for the optimization of new drug delivery-based bone regeneration strategies to repair damaged or impaired bone tissue. This study investigates the applicability of nuclear medicine and radiological techniques to monitor growth factor retention profiles and subsequent effects on bone formation. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2, 6.5 μg/scaffold) was incorporated into a sustained release vehicle consisting of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres embedded in a poly(propylene fumarate) scaffold surrounded by a gelatin hydrogel and implanted subcutaneously and in 5-mm segmental femoral defects in 9 rats for a period of 56 days. To determine the pharmacokinetic profile, BMP-2 was radiolabeled with 125I and the local retention of 125I-BMP-2 was measured by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), scintillation probes and ex vivo scintillation analysis. Bone formation was monitored by micro-computed tomography (μCT). The scaffolds released BMP-2 in a sustained fashion over the 56-day implantation period. A good correlation between the SPECT and scintillation probe measurements was found and there were no significant differences between the non-invasive and ex-vivo counting method after 8 weeks of follow up. SPECT analysis of the total body and thyroid counts showed a limited accumulation of 125I within the body. Ectopic bone formation was induced in the scaffolds and the femur defects healed completely. In vivo μCT imaging detected the first signs of bone formation at days 14 and 28 for the orthotopic and ectopic implants, respectively, and provided a detailed profile of the bone formation rate. Overall, this study clearly demonstrates the benefit of applying non-invasive techniques in drug delivery-based bone regeneration strategies by providing detailed and reliable profiles of the growth factor retention and bone formation at different implantation sites in a limited number of animals.

Keywords: Drug delivery, Controlled release, Bone morphogenetic protein-2, Single photon emission computed, tomography, Scintillation probes, Micro-computed tomography

1. Introduction

During the past decades, the accuracy and resolution of non-invasive monitoring techniques in medicine have greatly improved due to tremendous advances in knowledge, techniques and equipment. Due to the low morbidity of these procedures, they allow repeated evaluation of normal biological processes and diseases over time with limited risks of complications. As a result of the technological advances, many of these non-invasive techniques have also become available for research in small animals [1–3].

One of the research fields that can especially benefit from non-invasive monitoring techniques is bone tissue engineering. This field strives to create living, functional bone tissue to repair large bone defects due to disease, damage, or congenital defects that would fail to heal by themselves [4]. Controlled release of growth factors involved in the natural process of bone healing has become of great importance for the local modulation of bone formation at the defect site [5]. Although many of these growth factor delivery vehicles appear promising in animal experimental settings, optimization of the vehicle properties, release profiles and site-specific pharmacological actions remains challenging.

While in vivo bone formation is relatively easy to quantify by non-invasively radiographic techniques, studying the local release kinetics of the growth factors from the delivery vehicle in vivo is more complicated. One of the moderately successful ways to monitor in vivo release profiles consists of tracing a radiolabeled protein. This technique has been applied in an invasive way by ex-vivo measuring of the radioactive protein retention after surgical removal of the implants [6–11]. Although this ex vivo method is considered the golden standard because of the high spatial resolution and quantitative information, it has several disadvantages. Ex-vivo counting does not allow sequential release measurements of the same implant and requires large numbers of animals [12–16]. Furthermore, simultaneous measurement of both growth factor release and bone formation is complicated, since the first event usually precedes the latter. Therefore, non-invasive nuclear medicine techniques are being explored for determining release profiles [17–22].

Combining non-invasive nuclear medicine and radiological technologies holds great potential for the optimization of growth factor delivery vehicles, since they allow sequential measurements of both growth factor release and its biological effect (i.e. bone formation). The aim of this study was to investigate the feasibility of using non-invasive techniques to simultaneously monitor both growth factor release and bone formation. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and a previously described scintillation probe setup were used to determine local retention profiles and micro-computed tomography (μCT) was used for monitoring bone induction [17,18]. Both events were monitored at an ectopic and orthotopic implantation site in rats using a local delivery vehicle containing radioiodinated recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental design

A total of 18 rats were used for the experiment according to the approved protocol by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Growth factor release profiles and bone forming capacity were studied over a period of 8 weeks in an ectopic (subcutaneous) and orthotopic (critical sized femoral defect) implantation site in 8 rats. Release profiles were determined non-invasively by SPECT/CT and scintillation probes. Bone formation was studied using μCT. The implants were removed after 8 weeks of implantation for the comparison of non-invasive and ex-vivo measurements. Additional femoral defects without an implant were used as controls for the autologous bone formation. The bone formation in these controls was only determined using the ex-vivo μCT.

2.2. BMP-2 radioiodination

Recombinant human BMP-2 (purchased as part of an Infuse® research kit, Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Minneapolis, MN) dissolved in a BMP-2 buffer (5 mM glutamic acid, 2.5% glycine, 0.5% sucrose, 0.01% Tween80 and pH 4.5) was radiolabeled with I125 using Iodo-Gen® precoated test tubes according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Briefly, 100 μl of a 1.43 mg/ml BMP-2 solution, 20 μl of a 0.1 M NaOH solution and 2 mCi NaI125 were added to an Iodo-Gen® coated test tube and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. The radiolabeled protein was then separated from free 125I by 24 h dialysis (10 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) Slide-A-Lyzer®, Pierce) against the BMP-2 buffer and subsequently concentrated in a Vivaspin device (10 kDa MWCO, Sartorius AG, Germany). The final 125I-BMP-2 solution had an estimated concentration of 1.5 μg/μl, an activity of 4.0 μCi/μg and a trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitability of 99.8% precipitable counts.

2.3. BMP-2 delivery vehicle

The sustained delivery vehicle consisted of BMP-2-containing poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microspheres embedded into a poly (propylene fumarate) (PPF) rod which was surrounded by a cylindrical gelatin hydrogel. The materials and scaffold design were based on previous work on BMP-2 binding and extended protein release [23]. The PLGA (acid end-capped, 50:50 L:G ratio, Mw 23 kDa, Medisorb®, Lakeshore Biomaterials, AL) microspheres were fabricated using a double-emulsion-solvent-extraction technique as previously described [23,24]. The starting amount for the microsphere fabrication was 7.4 mg BMP-2/g PLGA with a 1:4 hot:cold ratio of 125I-BMP-2/BMP-2. Based on the 125I counts before and after the fabrication procedure, the microsphere entrapment efficiency was estimated at 85% or 1.1 μg BMP-2 per mg PLGA.

The microsphere/PPF composites were fabricated by photocrosslinking PPF with a Mw of 5800 Da and a polydispersity (PI) of 2.0 with N-vinylpyrrolidinone (NVP, Acros, Pittsburgh, PA) using the photo-initiator bis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl) phenylphosphine oxide (BAPO, Ciba Specialty Chemicals, Tarrytown, NY) as previously described [23,25]. This resulted in cylindrical microsphere/PPF rods with a diameter of 1.6 mm, a length of 6 mm, an average activity of 5.3± 0.3 μCi and an estimated BMP-2 loading of 6.5±0.4 μg. The rods were sterilized by ethanol evaporation and frozen down at −20 °C until use.

The microsphere/PPF composites were combined with a cylindrical shell composed of a gelatin (type A, 300 bloom, derived from acid-cured tissue, Sigma-Aldrich) hydrogel just before implantation. The gelatin hydrogels had an outer diameter of 3.5 mm and an inner diameter of 1.6 mm and were sterilized in 70% alcohol. Prior to implantation, the BMP-2 loaded microsphere/PPF composite were inserted into the gelatin cylinders.

2.4. Surgical procedure

A total of nine male 12-week-old Sprague Dawley rats (weight 323±9 g) were obtained from a professional stockbreeder (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Inc., Indianapolis, In) at least 1 week prior to the start of the experiment. Anesthesia was provided by an intramuscular injection of a ketamine/xylazine mixture (45/10 mg/kg) and the surgical sites were shaved and disinfected. For the orthotopic implant, a 2 cm skin incision was made along the lateral site of the right limb. By blunt dissection between the biceps femoris and the vastus lateralis muscle, the femur was exposed and circumferentially freed from muscles. A pre-drilled polyethylene plate (l×h×w, 22×3×4 mm) was fixed to the femur with 1 mm Kirchner-wires (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN). Subsequently, a 5-mm segmental defect was created using a surgical drill, which was filled with the microsphere/PPF/gelatin implant. No additional fixation was required to keep the slightly oversized implant (6 mm) with a PPF/microsphere rod diameter equal to the intra-medullary canal (1.6 mm) in place in the 5 mm femoral defect between inner 2 K-wires (7 mm apart). In the controls, the femoral defects were left empty. In addition to the orthotopic implant, the rats receive two ectopic implants in subcutaneous pockets in the lower left limb and the thoracolumbar area in the back. The limb pocket was filled with a 125I-BMP-2 implant and the pocket in the back with a non-radioactive implant.

2.5. SPECT/CT imaging and image analysis

Animal imaging was performed with a SPECT/CT system (X-SPECT, Gamma Medica-Ideas, Inc., Northridge, CA, USA) equipped with a single X-ray tube-detector unit and two identical high-resolution gamma cameras. The gamma cameras were collimated by low-energy, high-resolution, parallel-hole collimators with a 12.5 cm×12.5 cm field of view. Fixed system settings and imaging geometries were used throughout the course of the study. The maximum resolution of the SPECT and CT system are 1–2 mm and 50 μm, respectively. The counting rate linearity of the SPECT system was determined by scanning micro-centrifuge tubes containing 20 μl of 125I-BMP-2 solutions with activities varying from 0.041 to 12 μCi. The activity of the tube and the number of acquired counts showed a linear correlation with an R2 of 1.000.

The animals were imaged under ketamine/xylazine sedation (20/5 mg/kg) postoperatively and at days 3, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49 and 56. During imaging, the rats remained stationary on a platform in the center of the system, while the X-ray unit and gamma cameras rotated around the platform. Due to the limited field of view, the areas cranial and caudal to the diaphragm were imaged by two separate scans. For each area, a total of 64 projections at 10 s per projection were acquired over a 13 minute period for the SPECT image. The CT image acquisition (256 projections) was performed in 1 min using 0.25 mA and 80 kVp. To allow co-registration of the 3D images, both the SPECT and CT projections were reconstructed in a 7.97 cm (diameter) by 7.97 cm (length) image with a voxel size of 0.311 mm using a modified Feldkamp reconstruction algorithm and a Filtered Backprojection algorithm, respectively.

Analysis of the 125I-BMP-2 release in co-registered SPECT/CT reconstructions was performed using PMOD Biomedical Image Quantification and Kinematic Modeling Software (PMOD Technologies, Switzerland). In the postoperative scans, a volume of interest (VOI) was drawn around the full implantation site. These VOIs were loaded into the SPECT images of the consecutive scans and repositioned over the implants. The counts within each VOI were recorded, corrected for background activity and radioactive decay, and normalized to the activity at day 0 to obtain the release profiles.

Both the cranial and caudal SPECT scans were used to study the total body accumulation and thyroid uptake of 125I. The total body accumulation was determined by outlining the rat in the CT scans. The counts within the total body VOI were corrected for background activity and compared to the sum of the ectopic and orthotopic implant VOIs. The thyroid gland was outlined with a wide margin on the CT scan and the thyroid activity was expressed as percentage of the total administered 125I-BMP-2 dose.

Analysis of bone formation in the consecutive μCT images was performed using the Analyze software package (Biomedical Imaging Resource, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). The ectopic and orthotopic bone volumes in each scan were extracted and quantified by adjusting the threshold till the soft tissue was completely masked. Any visual scattering of the K-wires outside the cortical area of the femur was removed manually.

2.6. Scintillation probe measurements

The 125I-BMP-2 release profiles of the implants were also determined by a scintillation probe setup as previously described [18]. The scintillation probe setup consisted of two scintillation detectors (Model 44-3 low energy gamma scintillator, Ludlum measurements Inc., Tx, USA) connected to digital scalers (Model 1000 scaler, Ludlum measurements Inc.) which were collimated by a 3-cm hollow tube wrapped in lead tape. Postoperatively and at the other time points, the administered dose was determined by measuring the implant activity over four 1-minute periods using both detectors (2 measurements per detector) while the animal was still sedated. To determine the retention profile, the measurements were corrected for background activity and radioactive decay and expressed as percentage of the implanted dose.

2.7. Ex-vivo counting

After 8 weeks of implantation, the rats were euthanized by an overdose of pentobarbital and the scaffolds were excised and fixed in 1.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffered saline. The thyroid, stomach, kidneys, liver and spleen were also excised to evaluate the 125I tissue distribution. The 125I activity of the implants and tissues was determined using the gamma counter. The acquired implant counts were corrected for radioactive decay and normalized to activity before implantation.

2.8. Ex vivo μCT imaging

The two Kirchner-wires in the femur closest to the orthotopic implant were removed prior to ex vivo μCT imaging. The implants were scanned ex vivo at 0.49° angular increments using a μCT-system at 18 keV [26]. Individual projections were digitized and reconstructed to a 3-dimentional image consisting of 20 μm cubic voxels in a 16-bit grayscale using a modified Feldkamp cone beam tomographic reconstruction algorithm. Image analysis was also performed using the Analyze software package. The μCT scans were used to make 3D reconstructions of the calcified tissue and to quantify the volume of the newly formed bone. The same threshold for extracting the bone volume at the orthotopic site was used to extract the ectopic bone volume. All ex vivo reconstructions and volume quantifications were obtained using standardized threshold.

2.9. Histology

To visualize bone formation over time during the histological analysis, the rats received the fluorochrome markers alizarin red (10 mg/kg, IP) and calcein green (10 mg/kg, IP,) after 4 and 6 weeks of scaffold implantation, respectively. After μCT analysis, the implants were dehydrated in graded series of alcohol and embedded in methylmethacrylate for histological analysis. Sections were stained by Goldner’s trichrome, methylene blue/basic fuchsin and hematoxilin/eosin for routine histology. Unstained sections were used for the evaluation of the fluorochromes by fluorescence microscopy.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All data are reported as means±standard deviations (SD) for n=8. The local and systemic 125I-BMP-2 distribution, the implant retention profiles and the ectopic bone formation were analyzed using a general linear model with repeated measurements. The intra-class correlation coefficient was determined between the non-invasive release measurements obtained by SPECT imaging and the scintillation probe setup. Comparison between the methods for determination BMP-2 retention in the implants was performed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Bonferroni corrected post-hoc tests were done to analyze the differences between the groups. A paired t-test was performed for the analysis of orthotopic bone formation. All tests were performed by SPSS (version 13.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) at a significance level of p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Animals

All rats, except two, remained healthy during the experiment. One animal showed a femur fracture at the distal K-wire during imaging at day 3. Despite the fracture, the rat remained in good health and the release measurements were included in the analysis. Since healing of the fracture resulted in an abnormal shape of the femur and femoral defect, the rat was excluded for bone volume analysis. Another rat developed a deep infection of the surgical wound after 4 weeks of follow up and was therefore excluded from the analysis.

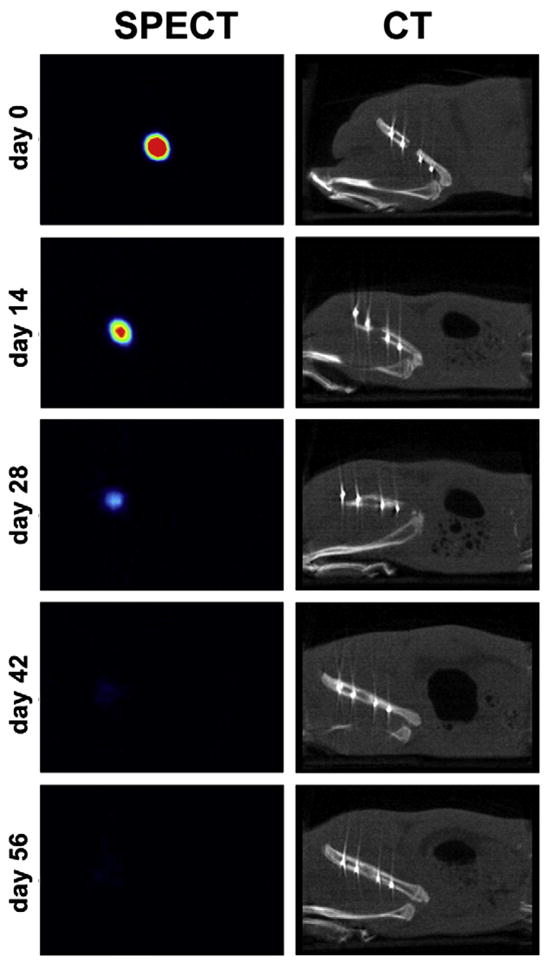

3.2. SPECT/CT imaging

Although the intensity of the radioactive signal decreased, the 125I-BMP-2 loaded implants remained visible over the full 56 day implantation period (Fig. 1). The background signal of the scans remained negligible over time and no specific uptake of the 125I tracer was seen in any other organs except the thyroid gland. The corresponding CT images showed regeneration of the femoral defect over time.

Fig. 1.

Consecutive SPECT (left) and CT (right) images of femoral implant of the same animal at different time points. The 125I-BMP-2 release from the implant is illustrated by the decreased activity over time. The regeneration of the femoral defect is shown in the CT images.

3.3. 125I-BMP-2 retention

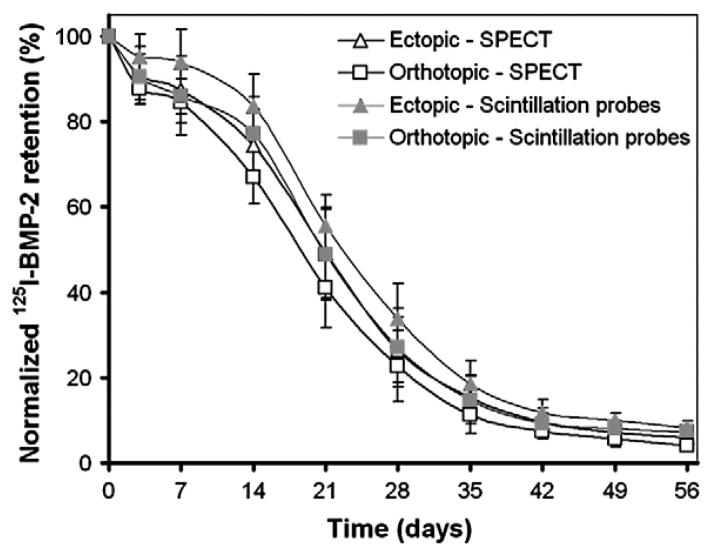

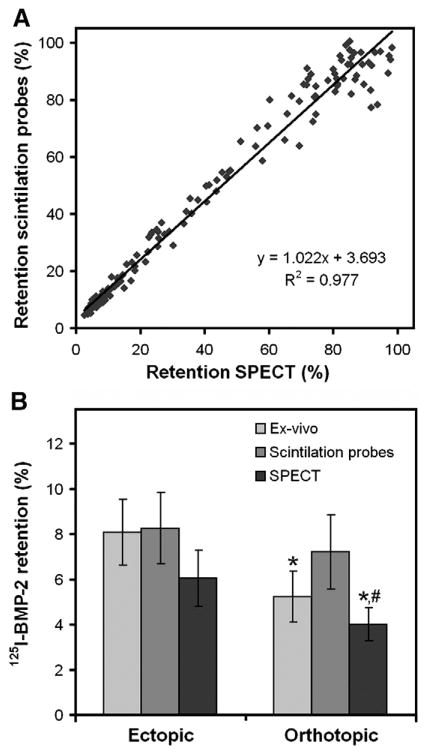

The amount of 125I-BMP-2 within the implants slowly decreased over the 56 day period (Fig. 2). The retention of the 125I-BMP-2 in the ectopic implants was significantly higher compared to the orthotopic implants (p=0.01). Although the measurements with SPECT resulted in lower retention percentages at all time points compared to the measurements with the scintillation probes, these differences were not significant (p=0.07). The measurements obtained by SPECT and the scintillation probes showed an excellent intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.977 (Fig. 3A). Comparison of the measurements obtained by the non-invasive methods and the ex-vivo counting method showed a significant overestimation of orthotopic BMP-2 retention by scintillation probes (p=0.01, Fig. 3B). Ectopic BMP-2 retention was measured without significant differences between the different methods (p>0.30).

Fig. 2.

Normalized 125I-BMP-2 retention profiles of the ectopic and orthotopic implants measured by the SPECT and scintillation probe setup as a function of time. Data represent means±SD for n=8.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the different methods to determine in vivo growth factor retention. (A) The correlation between the measurements acquired by the SPECT and scintillation probe setup. (B) Comparison of the 125I-BMP-2 implant retention after 56 days determined by the two non-invasive methods and the ex-vivo counting methods. Data in (B) represent means±SD for n=8. * and # designate significant difference relative to the ectopic retention of the implant measured with the same method and the orthotopic implant measured with the scintillation probe setup, respectively.

3.4. Total body accumulation and thyroid uptake of 125I

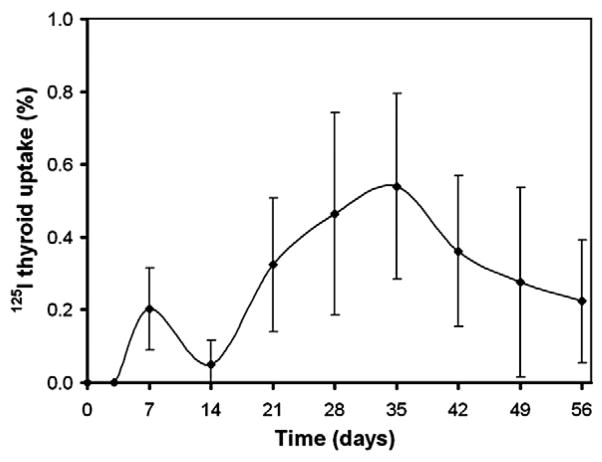

To obtain more insight into the organ accumulation and excretion of 125I-BMP-2 or its degradation products after their release from the implant, the total body and thyroid counts were measured using both cranial and caudal SPECT images. Comparison of total body counts and total implant counts showed identical profiles over time with no significant differences in count numbers (p=0.54, data not shown). To indicate the relation between the 125I uptake in the thyroid gland and the implanted 125I-BMP-2 activity, the normalized thyroid activity is shown in Fig. 4. The highest uptake of 0.58±0.28% was measured after 35 days of implantation, which corresponded to a 125I dose of 40±18 nCi.

Fig. 4.

Thyroid 125I uptake profile after implantation of radiolabeled BMP-2 containing ectopic and orthotopic implants as a function of time. Data represent means±SD for n=8.

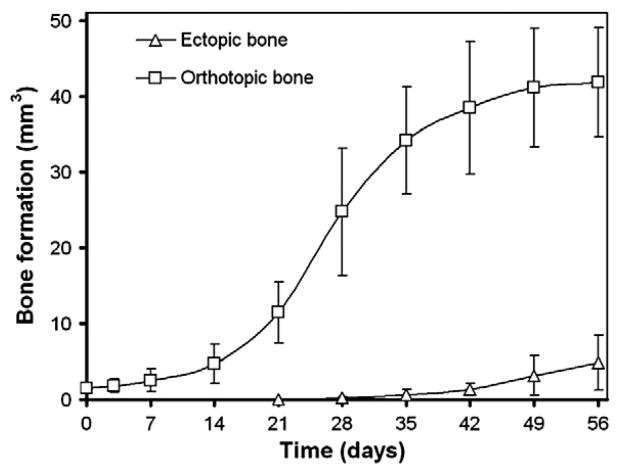

3.5. μCT analysis of bone formation

In vivo mineralization could be observed as early as 14 days in the femoral defect and 28 days in the subcutaneous 125I-BMP-2 loaded implants (images not shown). Quantification of bone volumes showed the orthotopic bone volumes increased significantly after 21 days of implantation compared to the 0 and 3 day time points (Fig. 5). Apart from the sequential in vivo imaging, high-resolution ex vivo μCT scans were made of the explants after sacrifice (Fig. 6). Although some bone formation was seen on the defect edges, none of the control implants showed bone bridging of the femoral defect. In vivo and ex vivo μCT measurements did not yield statistically significant differences in ectopic bone volume values, nor were differences found between 125I-labeled and non-labeled BMP-2 implants (Table 1). For orthotopic bone volume, the values generated by ex vivo measurement were significantly higher compared to those provided by in vivo scanning (p=0.02). The ex-vivo bone volume analysis showed a significantly higher bone volume in the 125I-BMP-2 implants compared to the empty controls.

Fig. 5.

Bone formation at the ectopic and orthotopic sites over the 56 day implantation period determined by consecutive in vivo μCT scanning and image analysis. Data represent means±SD for n=8.

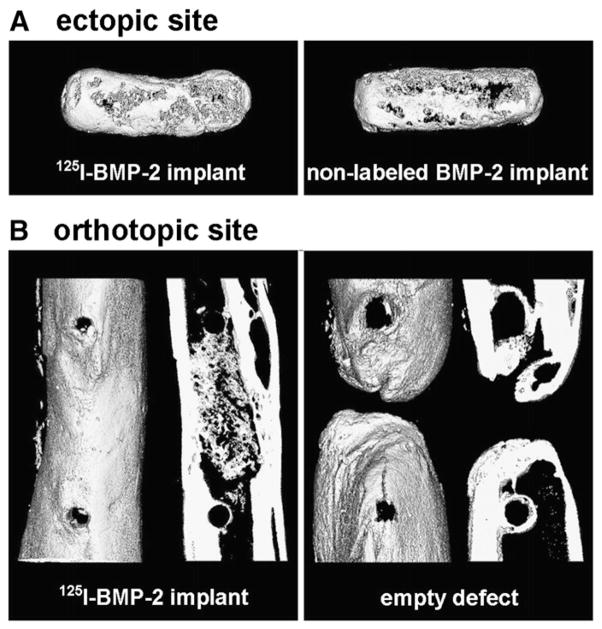

Fig. 6.

3D ex-vivo μCT renderings of ectopic bone formation in the 125I-BMP-2 and non-labeled BMP-2 loaded scaffolds (A) and 3D rentering and 400 μm mid-coronal slice of an empty femoral defect or defect containing a 125I-BMP-2 loaded implant (B) 8 weeks postoperatively.

Table 1.

Bone volume after 56 days of implantation

| Measurement method | 125I-labeled BMP-2 ectopic implant (mm3) | Non-labeled BMP-2 ectopic implant (mm3) | 125I-BMP-2 filled femoral defect (mm3) | Empty femoral defect (mm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-invasive | 4.9±3.6 | 6.0±2.2 | 43.1±7.3* | Not determined |

| Ex-vivo | 4.5±1.7 | 4.4±1.5 | 35.0±4.8*,+ | 15.1±6.6+ |

p=0.02 and

p<0.001.

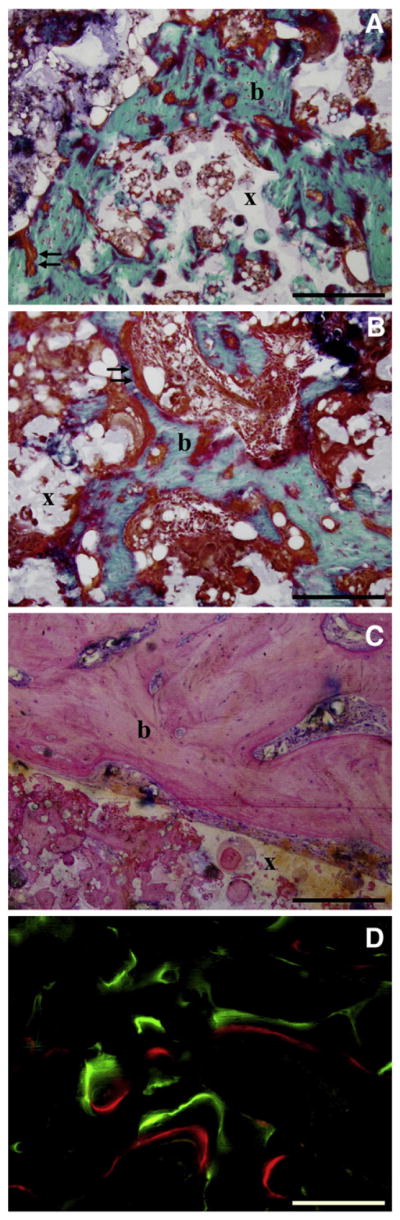

3.6. Histology

Bone formation as evaluated by histology (Fig. 7) was in line with the data obtained by μCT. The gelatin shell around the solid microsphere/PPF rod was completely resorbed after 56 days of implantation. Homogeneous degradation of the microspheres inside the PPF resulted in an interconnected, porous network that was filled with connective, adipous and bone tissue. The ectopic bone had a woven and trabecular appearance with osteoid depositions along the bone surface. No microscopic difference could be observed between the tissues formed in the 125I-BMP-2 loaded and non-labeled BMP-2 loaded ectopic implants. The appearance of bone formed inside the pores of the orthotopic 125I-BMP-2 loaded scaffolds was similar to bone formed in the ectopic implants. The osseous bridge between the proximal and distal part of the femur consisted of cortical and trabecular bone. In the empty defects, the newly formed bone that extended from the defects edges was not sufficient to bridge the defect. The rest of the empty defect was filled with well-vascularized connective tissue. Fluorescence microscopy showed the presence of both fluorochromes in all samples. Calcein green was found throughout the complete cortical bridge in the femoral defects (Fig. 7D) confirming the extensive mineralization in the μCT scans of the femoral defects before 4 weeks of implantation. In the ectopic implants the dye was found in small circles along the surface of the implants, indicating that ossification had started simultaneously at multiple sites in the ectopic sites (data not shown).

Fig. 7.

Histological sections of 125I-BMP-2 loaded (A, C, D) and BMP-2 loaded (B) implants after 8 weeks of ectopic (A,B) and orthotopic (C,D) implantation in rats. Degradation of the microspheres resulted in an interconnected porous PPF network (x). Goldner-stained sections showed bone formation (b) and osteoid deposition (arrows) on the surface and inside the pores of the microsphere/PPF scaffold (x). Fluorochrome analysis showed calceine green and alizarin red deposition in newly formed bone (D).

4. Discussion

This study clearly shows the benefit of using non-invasive techniques to monitor the growth factor retention and bone formation in local delivery vehicles during bone regeneration. The sequential measurements provided detailed profiles of both events in a small number of animals which results in less radioactive waste compared to ex-vivo measurement methods. The nuclear medicine and radiological techniques were able to detect 125I-BMP-2 retention and bone induction in both a superficial ectopic and a deep orthotopic implantation site. Comparison of the 125I detection methods showed a good correlation between the SPECT and scintillation probe measurements and no significant differences between the non-invasive and ex vivo analysis after 8 weeks of follow up.

Two non-invasive nuclear medicine techniques with a tremendous difference in spatial resolution were used to determine the local 125I-BMP-2 retention profiles. The SPECT system uses 2 collimated gamma cameras equipped with multiple small NaI detectors to obtain multiple projections which can be reconstructed into high-resolution 3D images. The single NaI detector of the scintillation probe cannot even localize the implant in a 2D plane and therefore has no spatial resolution at all. Despite the difference in spatial resolution, the local 125I-BMP-2 retention profiles had similar shapes with an excellent correlation between the non-invasive methods. This indicates that spatial resolution is less of an issue during local 125I-BMP-2 retention measurements.

The limited influence of spatial resolution is mainly the result of the 125I-BMP-2 administration method and pharmacokinetic characteristics. In contrast to immunodetection studies of cancer or non-oncological diseases, 125I-BMP-2 is not injected systemically but loaded into a local delivery vehicle and implanted at a known location [3,27]. The fixed position of the delivery vehicle after implantation facilitates consistent probe positioning. Furthermore, the favorable pharmacokinetic characteristics of BMP-2 help minimize the interference of non-implant related gamma-radiation. Previous 125I-BMP-2 injection and sustained release studies have shown a fast 125I clearance from the injection site or tissue surrounding the implant [18,19,22,28]. Apart from these local favorable conditions, the SPECT images and total body counts from this study also show a rapid systemic clearance and minimal organ accumulation of 125I-BMP-2 or its degradation products. The current study is in line with the low blood concentrations and high urine excretion of the 125I-label from previous studies [18,22]. The fixed implant position and the minimal interference of non-implant related gamma irradiation allowed the accurate and reliable measurement of the 125I-BMP-2 retention profile using the scintillation probe setup [17,18].

The advantage of both the SPECT and the scintillation probe setup is their high sensitivity for the detection of 125I. This isotope was favorable for the measurement of sustained release profiles due to its 60 day half-life and low energy gamma rays. Its relatively long half life allows a lower radioactive starting dose for the long term release measurements, whereas its low energy gamma radiation is unlikely to cause extensive biological damage [29]. Not surprisingly, comparison of bone volumes in the 125I-BMP-2 and non-labeled BMP-2 implants showed no significant effect of 125I-radiation on local ectopic bone formation. However, although the energy deposition of the 125I gamma rays is limited, the highly localized ionizations from Auger and conversion electrons can result in considerable biological consequences at the implantation site [29]. Since 125I-BMP-2 and its degradation products are rapidly cleared upon their release from the implant, we expect that most of the 125I label is located in the extracellular fluids where these electrons are potentially less toxic. The final choice of detection technology will depend on the intended application and research aims. The SPECT method has the advantage that it can be easily applied to new drugs or growth factors, since its high spatial resolution also provides insight in the pharmacokinetics, bio-distribution and 125I-labeling stability of the bioactive molecule. For growth factors with well studied, favorable pharmacokinetic profiles, the scintillation probe setup can be a simple and cheap non-invasive method to obtain detailed release profiles.

Although tracing of radioactively labeled proteins is an effective method to determine their in vivo pharmacokinetic profile, one of its general limitations is the possibility of detachment of the radioactive tracer from the protein. Since free 125I has a high affinity for the thyroid gland and to some extent for the stomach, monitoring of the radioisotope uptake in these organs can be used as an indicator for de-iodination. In this study, measurements of the thyroid and stomach by respectively SPECT and ex vivo counting indicated a limited accumulation of free 125I over the 8 week follow up period. This indicated that the 125I-BMP-2 is sufficiently stable towards in vivo de-iodination. Furthermore, it is unlikely that the exposure of the thyroid gland to these low 125I dosages will impair its function [30].

From a bone regeneration perspective, μCT imaging can assist in determining the onset and extent of bone induction over time. Since BMP-2 release preceded bone formation, monitoring of both events in the same animal over a prolonged period of time may be useful for optimizing the drug delivery vehicles. In the ectopic implantation site, the in vivo and ex vivo μCT systems were equally effective in determining bone volumes. The difference between the in vivo and ex vivo determined orthotopic bone volumes is likely the result of X-ray scattering of metal K-wires. However, this problem can be simply overcome in future studies by using different orthotopic models or alternative non-metal fixation methods.

All techniques allowed the simultaneous evaluation of the bone tissue engineering construct in both an ectopic and orthotopic site without interference between implantation sites. Whereas the femoral defect represents a clinically applicable site, the ectopic site showed the osteoinductive potential of the construct without interference of osteoconduction or periosteal bone formation as disturbing mechanisms in the BMP-2 induced bone formation. As shown by the femoral defect controls, the critical size defect did not heal spontaneously. Evaluation of the bone regeneration rate of the polymer construct with or without BMP-2 showed that the carrier alone was not able to promote healing of the defect.

The significant differences in protein release and bone formation between the ectopic and orthotopic implantation sites were not surprising. The differences between the surgical sites (e.g. location, wound bed dimensions and haematoma size) likely influenced the local physiologic environment around the delivery vehicle, which could have affected local BMP-2 release as well as the local response to this growth factor. Furthermore, the normal auto-inductive capacity of bone can be expected to enhance BMP-2 induced bone regeneration at the orthotopic implantation.

In conclusion, this study shows that non-invasive monitoring techniques can be used to obtain detailed profiles of growth factor retention and bone formation simultaneously in a limited number of animals. Our study has utilized 2 different methods to measure the growth factor retention from 2 different (ecotopic and orthotopic) implantation sites and examined its biological effects. Comparison of the SPECT and scintillation probe setup showed that both methods were equally effective for the measurement of the 125I-BMP-2 retention profile. By combining these nuclear medicine techniques with radiological imaging techniques, detailed profiles of both release and bone formation were obtained, which can assist in the optimization of the drug delivery vehicles and site-specific pharmacological actions in bone regeneration.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Shanfeng Wang and Mr. James A. Greutzmacher from the Tissue Engineering and Biomaterials laboratory, Mrs. Teresa Decklever and Dr. Bradley Kemp from the Department of Nuclear Medicine, Dr. Erik Ritman, Mrs. Patricia Beighley and Mr. Andrew Vercnocke from the Physiological Imaging Research Laboratory and Mrs. Julie Burges and Mr. Jim Herrick from the Bone Histomorphometry Laboratory for their contributions to this work. The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (R01 AR45871 and R01 EB03060) and The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development ZonMW (Agiko 920-03-325) for financial support.

References

- 1.Beckmann N, Kneuer R, Gremlich HU, Karmouty-Quintana H, Ble FX, Muller M. In vivo mouse imaging and spectroscopy in drug discovery. NMR Biomed. 2007;20(3):154–185. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross S, Piwnica-Worms D. Molecular imaging strategies for drug discovery and development. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10(4):334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peremans K, Cornelissen B, Van Den Bossche B, Audenaert K, Van de Wiele C. A review of small animal imaging planar and pinhole spect Gamma camera imaging. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2005;46(2):162–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2005.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260(5110):920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rose FR, Hou Q, Oreffo RO. Delivery systems for bone growth factors – the new players in skeletal regeneration. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2004;56(4):415–427. doi: 10.1211/0022357023312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdiu A, Walz TM, Wasteson A. Uptake of 125I-PDGF-AB to the blood after extravascular administration in mice. Life Sci. 1998;62(21):1911–1918. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00159-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friess W, Uludag H, Foskett S, Biron R, Sargeant C. Characterization of absorbable collagen sponges as rhBMP-2 carriers. Int J Pharm. 1999;187(1):91–99. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(99)00174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao T, Uludag H. Effect of molecular weight of thermoreversible polymer on in vivo retention of rhBMP-2. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;57(1):92–100. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200110)57:1<92::aid-jbm1146>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hori K, Sotozono C, Hamuro J, Yamasaki K, Kimura Y, Ozeki M, Tabata Y, Kinoshita S. Controlled-release of epidermal growth factor from cationized gelatin hydrogel enhances corneal epithelial wound healing. J Control Release. 2007;118(2):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosseinkhani H, Hosseinkhani M, Khademhosseini A, Kobayashi H. Bone regeneration through controlled release of bone morphogenetic protein-2 from 3-D tissue engineered nano-scaffold. J Control Release. 2007;117(3):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uludag H, Gao T, Wohl GR, Kantoci D, Zernicke RF. Bone affinity of a bisphosphonate-conjugated protein in vivo. Biotechnol Prog. 2000;16(6):1115–1118. doi: 10.1021/bp000066y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi Y, Yamamoto M, Tabata Y. Enhanced osteoinduction by controlled release of bone morphogenetic protein-2 from biodegradable sponge composed of gelatin and beta-tricalcium phosphate. Biomaterials. 2005;26(23):4856–4865. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uludag H, D’Augusta D, Golden J, Li J, Timony G, Riedel R, Wozney JM. Implantation of recombinant human bone morphogenetic proteins with biomaterial carriers: a correlation between protein pharmacokinetics and osteoinduction in the rat ectopic model. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50(2):227–238. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200005)50:2<227::aid-jbm18>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uludag H, D’Augusta D, Palmer R, Timony G, Wozney J. Characterization of rhBMP-2 pharmacokinetics implanted with biomaterial carriers in the rat ectopic model. J Biomed Mater Res. 1999;46(2):193–202. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(199908)46:2<193::aid-jbm8>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto M, Tabata Y, Hong L, Miyamoto S, Hashimoto N, Ikada Y. Bone regeneration by transforming growth factor beta1 released from a biodegradable hydrogel. J Control Release. 2000;64(1–3):133–142. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto M, Takahashi Y, Tabata Y. Controlled release by biodegradable hydrogels enhances the ectopic bone formation of bone morphogenetic protein. Biomaterials. 2003;24(24):4375–4383. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00337-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delgado JJ, Evora C, Sanchez E, Baro M, Delgado A. Validation of a method for non-invasive in vivo measurement of growth factor release from a local delivery system in bone. J Control Release. 2006;114(2):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kempen DH, Lu L, Classic KL, Hefferan TE, Creemers LB, Maran A, Dhert WJ, Yaszemski MJ. Non-invasive screening method for simultaneous evaluation of in vivo growth factor release profiles from multiple ectopic bone tissue engineering implants. J Control Release. 2008;130(1):15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Louis-Ugbo J, Kim HS, Boden SD, Mayr MT, Li RC, Seeherman H, D’Augusta D, Blake C, Jiao A, Peckham S. Retention of 125I-labeled recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 by biphasic calcium phosphate or a composite sponge in a rabbit posterolateral spine arthrodesis model. J Orthop Res. 2002;20(5):1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruhe PQ, Boerman OC, Russel FG, Spauwen PH, Mikos AG, Jansen JA. Controlled release of rhBMP-2 loaded poly(DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid)/calcium phosphate cement composites in vivo. J Control Release. 2005;106(1–2):162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo BH, Fink BF, Page R, Schrier JA, Jo YW, Jiang G, DeLuca M, Vasconez HC, DeLuca PP. Enhancement of bone growth by sustained delivery of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 in a polymeric matrix. Pharm Res. 2001;18(12):1747–1753. doi: 10.1023/a:1013382832091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokota S, Uchida T, Kokubo S, Aoyama K, Fukushima S, Nozaki K, Takahashi T, Fujimoto R, Sonohara R, Yoshida M, Higuchi S, Yokohama S, Sonobe T. Release of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein 2 from a newly developed carrier. Int J Pharm. 2003;251(1–2):57–66. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kempen DHR, Lu L, Hefferan TE, Creemers LB, Maran A, Classic KL, Dhert WJA, Yaszemski MJ. Retention of in vitro and in vivo BMP-2 bioactivity in sustained delivery vehicles for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:3245–3252. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oldham JB, Lu L, Zhu X, Porter BD, Hefferan TE, Larson DR, Currier BL, Mikos AG, Yaszemski MJ. Biological activity of rhBMP-2 released from PLGA microspheres. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122(3):289–292. doi: 10.1115/1.429662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S, Lu L, Yaszemski MJ. Bone–tissue-engineering material poly(propylene fumarate): correlation between molecular weight, chain dimensions, and physical properties. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(6):1976–1982. doi: 10.1021/bm060096a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorgensen SM, Demirkaya O, Ritman EL. Three-dimensional imaging of vasculature and parenchyma in intact rodent organs with X-ray micro-CT. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(3 Pt 2):H1103–H1114. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.3.H1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldenberg DM, Larson SM. Radioimmunodetection in cancer identification. J Nucl Med. 1992;33(5):803–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruhe PQ, Boerman OC, Russel FG, Mikos AG, Spauwen PH, Jansen JA. In vivo release of rhBMP-2 loaded porous calcium phosphate cement pretreated with albumin. J Mater Sci, Mater Med. 2006;17(10):919–927. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0181-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloomer WD, Adelstein SJ. Iodine-125 cytotoxicity: implications for therapy and estimation of radiation risk. Int J Nucl Med Biol. 1981;8(2–3):171–178. doi: 10.1016/0047-0740(81)90071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doniach I, Shale DJ. Biological effects of 131I and 125I isotopes of iodine in the rat. J Endocrinol. 1976;71(1):109–114. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0710109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]