Abstract

Background

In 2009, the Institute of Medicine revised gestational weight gain recommendations; revisions included body mass index (BMI) category cut-point changes and provision of range of gain for obese women. Our objective was to examine resident prenatal care providers’ knowledge of revised guidelines.

Methods

Anonymous electronic survey of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine residents across U.S. from January–April 2010.

Results

660 completed the survey; 79% female and 69% aged 21–30 years. When permitted to select ≥1 response, 87.0% reported using BMI to assess weight status at initial visits, 44.4% reported using “clinical impression based on patient appearance”, and 1.4% reported not using any parameters. When asked the most important baseline parameter for providing recommendations, 35.8% correctly identified pre-pregnancy BMI, 2.1% reported “I don’t provide guidelines,” and 4.5% reported “I do not discuss gestational weight gain.” 57.6% reported not being aware of new guidelines. Only 7.6% selected correct BMI ranges for each category. Only 5.8% selected correct gestational weight gain ranges. Only 2.3% correctly identified both BMI cutoffs and recommended gestational weight gain ranges per 2009 guidelines.

Conclusions

Guideline knowledge is the foundation of accurate counseling, yet resident prenatal care providers were minimally aware of the 2009 Institute of Medicine gestational weight gain guidelines almost a year after their publication.

INTRODUCTION

Only one-third of women in the United States gain appropriate weight in pregnancy(1) despite evidence that weight gain within recommended ranges optimizes both maternal and neonatal health outcomes.(2) Women who receive guideline-congruent weight gain counseling are more likely to gain appropriately,(3; 4) yet upwards of two-thirds of women report no gestational weight gain counseling or counseling that is inconsistent with Institute of Medicine recommendations.(3–5) Barriers to provider implementation of practice guidelines include lack of awareness of and lack of familiarity with recommendations.(6)

In May 2009, the Institute of Medicine published a revision of its 1990 gestational weight gain recommendations.(2) Like the 1990 recommendations,(7) the 2009 recommendations are specific to pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI).(2) However, the recommendations were updated in two notable ways: first, BMI categories were changed from Metropolitan Life Insurance Table cut-points to those endorsed by World Health Organization(2) and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute for identification and treatment of overweight/obesity in adults,(8) and second, the guidelines provided a specific recommended range of gain for obese women as opposed to the 1990 recommendation of ‘at least 15 pounds’ without a stated upper limit (Table 1).(2; 7) As new guidelines are established, efforts need to be made to increase providers’ awareness of these guidelines, to encourage their adoption by practitioners, and to increase knowledge of the recommendations among pregnant patients themselves.(2) The objective of this study was to examine United States resident physician prenatal care providers’ knowledge of revised gestational weight gain recommendations.

Table 1.

Institute of Medicine gestational weight gain recommendations: 1990 versus 2009 guidelines

| 1990 Recommendations | 2009 Recommendations | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-pregnancy Weight Status (BMI; kg/m2)* | Gestational Weight Gain (lbs) | Pre-pregnancy Weight Status (BMI; kg/m2)* | Gestational Weight Gain (lbs) |

| Low weight (<19.8) | 28–40 | Underweight (< 18.5) | 28–40 |

| Normal weight (19.8–26.0) | 25–35 | Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 25–35 |

| High weight (26.1–29.0) | 15–25 | Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 15–25 |

| Obese (>29.0) | At least 15 | Obese (≥ 30.0) | 11–20 |

BMI is body mass index (kg/m2)

MATERIALS and METHODS

We conducted a survey of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine residents across the United States. In September 2009, we piloted the survey with Obstetrics/Gynecology residents (n=21) at the University of Massachusetts Mdical School and refined the survey accordingly (reduced length, enhance clarity/wording and improved response options). In January 2010, an anonymous electronic survey was distributed to residents training in U.S. Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine residency programs nationwide. Utilizing FREIDA (Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database Access System) and APGO (Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics) membership directories, residency websites, and publically-available information, we emailed all U.S. Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine residency program directors and/or coordinators. The initial contact email message contained: (1) an explanation of study purpose, (2) a request to contact their residents with a link to the web-based survey along with the study explanation, and (3) an option to notify the study team if they opted not to forward the link and/or to not receive future correspondences related to this study. Reminder emails were sent as needed at one and two months following the initial invitation (February and March 2010). The survey was closed three months after the first notification (April 2010). This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the University of Massachusetts Medical School’s Institutional Review Board.

The 44-question survey was administered through SurveyMonkey©. Because the 2009 Institute of Medicine recommendations included updated cutoffs for classifying pre-pregnancy BMI and addressed a range of recommended gestational weight gain by BMI category, knowledge questions for both topics were included. Residents were asked to select the correct BMI cutoffs to categorize women as underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese from five options that included both 1990 and 2009 cutoffs, and an option of “I would need to review guidelines to answer.” Responses were categorized as correct if in accordance with Institute of Medicine 2009 gestational weight gain guidelines (underweight BMI<18.5 kg/m2, normal weight 18.5≤BMI<25 kg/m2, overweight 25≤BMI<30 kg/m2, or obese ≥30 kg/m2), (2) incorrect, or (3) need to review guidelines. It should be noted that because of a typographical error in the survey, both >29.9 and >30.0 were considered correct answers for the obese BMI category. Participants were then asked to select the recommended gestational weight gain range, based on 2009 Institute of Medicine guidelines, for a singleton pregnancy for women with underweight, normal, overweight, or obese pre-pregnancy BMIs from a list of 11 options ranging from weight loss of greater than 10 pounds to weight gain of 50 pounds and including ranges of gain (e.g., 25–35 pounds) and single weight gain amounts (e.g., 30 pounds). For each pre-pregnancy BMI category, responses were categorized as correct if in accordance with the Institute of Medicine 2009 gestational weight gain guidelines (28–40 pounds for women who were underweight pre-pregnancy, 25–35 pounds for normal weight women, 15–25 pounds for overweight women, and 11–20 pounds for obese women)(2) or incorrect. We conducted additional analyses to allow variation in interpretation of the question; respondents who selected multiple answers were considered to have answered correctly if all selected answers were consistent with the Institute of Medicine 2009 guidelines (e.g., selecting “30 pounds”, “25–35 pounds”, and “35 pounds” for normal weight women).

Respondents self-reported age, gender, resident specialty (Obstetrics/Gynecology versus Family Medicine), and post-graduate year. Respondents’ BMI was calculated from self-reported height and weight, and weight status was categorized as underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5 ≤ BMI < 25 kg/m2), overweight (25 ≤ BMI < 30 kg/m2), or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2).(8)

Descriptive statistics presented as N (%). Categorical variables were compared using chi-squared test. Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) statistical analysis software.

RESULTS

A total of 660 residents (338 Obstetrics/Gynecology and 322 Family Medicine) completed the survey. The majority of respondents were female (79%) and aged 21–30 years (69%; Table 2). Obstetrics/Gynecology residents were more likely to be female than Family Medicine residents (p<0.0001) and were slightly younger (p=0.04). Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine residents had varying representation of post-graduate years in training (p<0.0001); Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine residencies are typically three and four years respectively. Of the 416 resident respondents that reported both their height and weight (63%), 70.4% were normal weight, 20.2% were overweight, and 6.7% were obese. There was no statistically significant difference in BMI distributions between specialties (p=0.39).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the sample, N (%)

| Total (N=660) | Resident Specialty

|

P-values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obstetrics & Gynecology (N=338) | Family Medicine (N=322) | |||

|

| ||||

| Post-Graduate Year (n=660) | <0.0001 | |||

| Year 1 | 206 (31.2%) | 96 (28.4%) | 110 (34.2%) | |

| Year 2 | 183 (27.7%) | 69 (20.4%) | 114 (35.4%) | |

| Year 3 | 196 (29.7%) | 98 (29.0%) | 98 (30.4%) | |

| Year 4 | 75 (11.4%) | 75 (22.2%) | —— | |

|

| ||||

| Gender (n=499) | <0.0001 | |||

| Female | 392 (78.6%) | 234 (89.0%) | 158 (77.0%) | |

| Male | 107 (21.4%) | 29 (11.0%) | 78 (33.0%) | |

|

| ||||

| Age (n=504) | 0.04 | |||

| 21–30 years | 347 (68.9%) | 193 (72.3%) | 154 (65.0%) | |

| 31–40 years | 144 (28.6%) | 71 (26.6%) | 73 (30.8%) | |

| 41+ years | 13 (2.6%) | 3 (1.1%) | 10 (4.2%) | |

|

| ||||

| Weight status (n=416) | 0.39 | |||

| Underweight | 11 (2.7%) | 7 (3.1%) | 4 (2.1%) | |

| Normal weight | 293 (70.4%) | 164 (73.2%) | 129 (67.2%) | |

| Overweight | 84 (20.2%) | 39 (17.4%) | 45 (23.4%) | |

| Obese | 28 (6.7%) | 14 (6.3%) | 14 (7.3%) | |

When permitted to select more than one response, the majority of residents (87.0%) reported routinely using BMI and/or parameters related to BMI (weight 82.2% and height 72.3%) to assess patients’ weight status at initial prenatal visits, while 44.4% reported using their “clinical impression based on patient appearance”, and 1.4% reported not using any parameters (Table 3, question 1). Approximately half (54.6%) of respondents reported calculating BMI for all patients at their initial prenatal visit, approximately one-third when patients are visually estimated as overweight (29.5%) or obese (32.4%) and 5.5% reported never calculating it (Table 3, question 2). More than one third (35.8%) of respondents correctly identified pre-pregnancy BMI as the most important baseline parameter when providing gestational weight gain recommendations, 37.2% selected pre-pregnancy weight, almost two-fifths selected either weight or BMI at the first prenatal visit, and 2.1% stated that “I don’t provide guidelines to patients” (Table 3, question 3). When asked which measurements needed to provide appropriate gestational weight gain recommendations are recorded in prenatal patients’ medical records, residents reported that pre-pregnancy weight is “always present” or “usually present” with the greatest frequency, followed by height; about a quarter of residents reported that BMI is “always present” in their patients’ medical records (Table 3, question 4).

Table 3.

Summary of Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine residents’ responses to survey questions regarding prenatal counseling about gestational weight gain (GWG), N (%)

|

1. Clinical parameters used routinely to assess weight status at initial prenatal visits (select all that apply): (n=638)*

| |||

| BMI | 555 (87.0%) | ||

| Weight | 528 (82.8%) | ||

| Height | 461 (72.3%) | ||

| Clinical impression based on appearance | 283 (44.4%) | ||

|

| |||

|

2. BMI calculated for prenatal patients under which conditions (select all that apply): (n=577)

| |||

| All patients at initial prenatal care visit | 315 (54.6%) | ||

| When patient appears obese | 187 (32.4%) | ||

| When patient appears overweight | 170 (29.5%) | ||

| When co-morbidities exist | 125 (21.7%) | ||

| When time permits | 73 (12.7%) | ||

| Never | 32 (5.5%) | ||

| Other | 32 (5.5%) | ||

|

| |||

|

3. When providing gestational weight gain guidelines for singleton pregnancies, BASELINE parameter most important to respondents (select one): (n=581)

| |||

| Pre-pregnancy weight | 216 (37.2%) | ||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 208 (35.8%) | ||

| Weight at first prenatal visit | 65 (11.2%) | ||

| BMI at first prenatal visit | 39 (6.7%) | ||

| Physical appearance | 16 (2.8%) | ||

| Ideal BMI | 13 (2.2%) | ||

| I don’t provide guidelines to patients | 12 (2.1%) | ||

| Ideal body weight for height | 11 (1.9%) | ||

| Other | 1 (0.2%) | ||

|

| |||

|

4. Frequency anthropometric measures are recorded in prenatal charts:

| |||

| BMI (n=576) | Pre-Pregnancy Weight (n=622) | Height (n=611) | |

|

| |||

| Always Present | 148 (24.7%) | 403 (64.8%) | 345 (56.5%) |

|

| |||

| Usually Present | 156 (27.1%) | 183 (29.4%) | 160 (26.2%) |

|

| |||

| Occasionally Present | 176 (30.6%) | 32 (5.1%) | 94 (15.4%) |

|

| |||

| Never Present | 96 (16.7%) | 4 (0.6%) | 12 (2.0%) |

|

| |||

|

5. How respondents became aware of Institute of Medicine 2009 gestational weight gain recommendations: (n=535)

| |||

| Not aware | 298 (55.7%) | ||

| Journal article | 76 (14.2%) | ||

| Educational sessions | 64 (12.0%) | ||

| Colleague | 46 (8.6%) | ||

| Email notification | 35 (6.5%) | ||

| Conference or seminar | 11 (2.1%) | ||

| Webinar | 3 (0/6%) | ||

| Other | 2 (0.4%) | ||

|

| |||

|

6. Factors by which 2009 Institute of Medicine gestational weight gain guidelines should be altered: (select all that apply) (n=530)**

| |||

| Need to review guidelines to answer | 354 (66.8%) | ||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 156 (29.4%) | ||

| Singleton versus multiple gestation | 119 (22.5%) | ||

| Pre-pregnant weight | 100 (18.9%) | ||

| Medical co-morbidities | 75 (14.2%) | ||

| BMI at initial prenatal visit | 53 (10.0%) | ||

| Weight at initial prenatal visit | 34 (6.4%) | ||

| Weight retention after prior pregnancy | 32 (6.0%) | ||

| Height | 27 (5.1%) | ||

|

| |||

|

7. When counseling patients on gestational weight gain, respondents typically present recommendations by: (n=574)

| |||

| Giving a range of pounds for total gain goal | 482 (84.0%) | ||

| Giving specific number of pounds as total gain goal or giving a specific endpoint weight | 54 (9.4%) | ||

| Not discussing gestational weight gain with patients | 26 (4.5%) | ||

Question 1 allowed respondents to ‘select all that apply.’ Data is presented only for those responses that had a frequency of >5%. Other responses included waist circumference (1.4%), do not routine assess weight status (1.4%), other (0.3%), caliper measurements (0%), and waist to hip ratio (0%).

Question 6 allowed respondents to ‘select all that apply.’ Data is presented only for those responses that had a frequency of >5%. Other responses included age (4.2%) and race (3%).

Over half of residents (55.7%) reported not being made aware of the 2009 Institue of Medicine changes in gestational weight gain recommendations (Table 3, question 5). The remaining respondents reported being made aware primarily through a variety of sources, the most common of which were journal articles (14.2%) or educational sessions (12.0%). As residents in postgraduate year 1 (PGY1) would have been medical students and not residents at the time the new guidelines were made public, an evaluation by PGY status (PGY1 vs. PGY2–4) was performed and did not reveal any statistically significant differences (p=0.12) in awareness of changed guidelines (data not shown). Two-thirds (66.8%) of residents stated that they would need to review the guidelines prior to answering the question pertaining to what factors should alter gestational weight gain recommendations; less than a third of residents correctly identified pre-pregnancy BMI (29.4%) and single versus multiple gestations (22.5%) as factors to consider (Table 3, question 6).

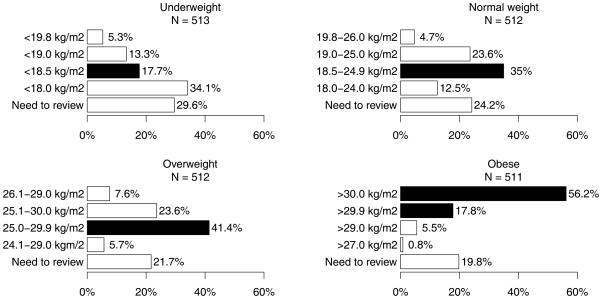

When asked to select the BMI cutoffs used by the 2009 recommendations for underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese women, 17.7%, 35.0%, 41.4%, and 74.0% of residents selected correct responses for each BMI category respectively (Figure 1). Regardless of BMI category, approximately one-quarter (range 19.8–29.6%) of respondents would need to review guidelines in order to identify the appropriate BMI ranges associated with the 2009 Institute of Medicine recommendations. General knowledge of the categories was significantly below 50% for each category with the exception of obesity and the previously stated caveat related to survey responses in that category. Fewer residents selected BMI cut-offs corresponding to 1990 guidelines than those stating they would need to review guidelines.

Figure 1. Residents’ knowledge of body mass index (BMI) ranges associated with Institute of Medicine 2009 gestational weight gain recommendations, by patients’ pre-pregnancy weight status.

Black bars represent answers corresponding to BMI cutoffs included in the 2009 Institute of Medicine gestational weight gain recommendations; white bars represent incorrect answers. Only respondents who selected one answer are included in this graph.

Residents were asked to identify recommended gain consistent with 2009 Institute of Medicine guidelines for women of different pre-pregnancy BMIs. Approximately one-third of respondents selecting a single option, answered correctly for women who were underweight (35.6%), normal weight (40.4%), or overweight (31.9%) pre-pregnancy (Table 4). However, only 17.2% of residents were able to select the correct weight gain recommendations for obese prenatal patients (Table 4). In general, respondents chose weights or weight ranges that were less than recommended, especially for overweight and obese women. The most common answer selected for obese women was a gain of 0–10 pounds (33% of respondents) and 22% indicated that obese women should gain 5–15 pounds, whereas the IOM 2009 guidelines recommend a gain of 11–20 pounds.

Table 4. Residents’ knowledge of Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2009 gestational weight gain (GWG) recommendations, by patients’ pre-pregnancy weight status.

Only respondents who selected one answer are included in the table. Dark gray cells represent answers corresponding to recommended ranges of GWG according to 2009 IOM GWG guidelines; light gray cells indicate answers consistent with IOM 2009 recommendations but not inclusive of entire recommended range; white cells represent answers inconsistent with IOM 2009 recommendations.

| Underweight (N=444) | Normal weight (N=450) | Overweight (N=445) | Obese (N=448) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gain 50 lbs | 0.9% | 0% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Gain 28–40 lbs | 35.6% | 0.9% | 0.2% | 0.7% |

| Gain 35 lbs | 9% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0% |

| Gain 25–35 lbs | 31.1% | 40.4% | 1.1% | 0% |

| Gain 30 lbs | 9.2% | 4.2% | 1.6% | 0.2% |

| Gain 15–25 lbs | 8.8% | 40.4% | 31.9% | 4.9% |

| Gain 15 lbs | 1.4% | 3.1% | 7% | 4.9% |

| Gain 11–20 lbs | 2.3% | 7.1% | 20.5% | 17.2% |

| Gain 5–15 lbs | 0.7% | 2.4% | 24.7% | 22.1% |

| Gain 0–10 lbs | 0.2% | 0.7% | 11% | 33% |

| Lose up to 10 lbs | 0.9% | 0.4% | 1.6% | 16.7% |

In additional analyses conducted to allow variation in interpretation of the question, respondents selecting multiple answers were considered correct if all selected answers were consistent with Institute of Medicine 2009 guidelines as previously described in methods. Such categorization was done for 1/48 respondents who selected multiple answers for recommended gestational weight gain for underweight women, 9/56 for normal weight women, 1/49 for overweight women, and 0/41 for obese women. If respondents who selected multiple responses were included, 40.4% answered correctly for underweight, 41.7% for normal weight, 35.2% for overweight and 20.2% for obese BMI women.

The majority of respondents (84.0% of 574) correctly identified that when counseling patients on gestational weight gain, they should present their recommendations as a range of gain for total pregnancy weight gain (Table 3, question 7). However, when asked to pick the appropriate amount of weight to gain, when counseling patients about gestational weight gain per BMI category, many of these respondents selected single points of gain (e.g., 30 pounds) as opposed to ranges. Single points of gain as opposed to ranges were selected by 20.5%, 7.5%, 9% and 5.3% of respondents for underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese BMI (Table 4).

Of the 660 respondents, only 7.6% selected the correct BMI range for all BMI categories and 13.2% stated they would need to review the guidelines to correctly answer for all categories. Only 5.8% of respondents selected the correct gestational weight gain ranges for all BMI categories, and only 2.3% correctly identified both BMI categories and weight gain ranges as per 2009 Institute of Medicine guidelines for all categories of pre-pregnancy BMI. Knowledge of BMI cutoffs or recommended ranges of gestational weight gain did not differ by demographic characteristics listed in Table 1 nor by program specialty (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, 58% of United States Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine residents were not aware of the updated 2009 Institute of Medicine gestational weight gain guidelines nearly one year after their publication. Only 2.3% of respondents could identify BMI cutoffs and BMI-based weight gain recommendations presented in the revised guidelines for underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obese women. Given that few respondents selected answers consistent with the former 1990 guidelines, knowledge appears to be lacking overall, not just lagging in the update from 1990 to 2009.

Lack of provider advice and inaccurate advice are associated with inappropriate gain.(3; 4) Conversely, women who receive guideline-congruent weight gain counseling are more likely to gain within recommended ranges.(3; 4) In a survey that predated the gestational weight gain guideline revisions, 57.9% of physicians surveyed from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists indicated that ‘most of the time’ they counsel their patients regarding weight gain in pregnancy; this survey however did not report the accuracy of this counseling.(9) Previous studies have found that 27–58% of women reported not receiving advice about gestational weight gain from their prenatal providers(3; 10). In a recent study of women in late pregnancy, only 29% reported receiving any provider counseling and only 12% reported counseling concordant with Institute of Medicine 2009 recommendations.(5) Additionally, a recent study identified consistent themes from semi-structured interviews of 24 overweight and obese women who recently delivered their first child that included (1) providers advise gain in excess of guidelines or give no recommendations at all and (2) providers are perceived as being unconcerned about excessive gain.(11) Importantly, these women additionally reported that they desire and value gestational weight gain advice from their providers.(11) Our results suggest that providers’ lack of knowledge of guidelines may at least partially account for observed low reported rates of guideline-congruent counseling.

Provider knowledge of new guidelines is critical for accurate counseling. In our study, a majority of resident respondents stated that they were unaware of the new guidelines, a known barrier to gestational weight gain counseling.(6) We surveyed physicians-in-training so as to minimize the effect of an inertia related to previous practice. Additionally, with ‘medical knowledge’ and ‘practice-based learning and improvement’ being Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) competencies,(12) and with residents generally having protected curricular and/or didactic time, we sought to optimize the likelihood that the surveyed population would be knowledgeable of the new guidelines. Despite this effort, overall awareness of and knowledge about the old or revised gestational weight gain guidelines was quite low and thus lead us to consider that resident physicians may experience complex interactions with new information that precludes efficient diffusion of innovation(13) and that they may additionally experience other barriers unique to their training positions.(14) We gave consideration to often long cycles between repeated or refreshed topics in residency core curricula by evaluating response differences by post-graduate year and noted no difference (data not shown). We expected physicians-in-training to know the most up-to-date guidelines; however, our findings highlight a need to identify and bolster effective educational opportunities regarding awareness, implementation of evidenced-based guidelines. In this case, this would be true of both the old and revised guidelines.

With appreciation for the unique circumstances of residents and residency training, and with consideration of answer correctness utilizing both 1990 and 2009 Institute of Medicine gestational weight gain recommendations, this study highlights a significant deficit regarding the didactic knowledge needed for accurate counseling despite modest changes in guidelines and the prior ones existing for nearly 20 years. This deficit may reflect the low prioritization of weight and weight discussions amongst competing training priorities and/or that some health professionals do not consider gestational weight gain important(15) despite significant evidence-based associations with non-adherence and suboptimal obstetric outcomes(2) and small trials where women who were provided guideline-congruent weight gain counseling, were more likely to gain appropriately during pregnancy.(16; 17)

In order to provide guideline-concordant gestational weight gain counseling, providers need access to the basic anthropometric parameters necessary to calculate pre-pregnancy BMI. Only 56.5%, 64.8% and 25.7% of respondents reported that height, prepregnancy weight, and prepregnancy BMI were “always” present in their patients’ charts. We previously found that prepregnancy weight and height were missing from 27.9% and 27.7% of prenatal charts, and that only 4.6% of charts had BMI documented.(18) Encouraging prenatal care providers to document prepregnancy weight and height and to calculate BMI is an important step and could be a relatively simple intervention for increasing the proportion of pregnant women who are counseled appropriately. Electronic medical records that require recording of these data and automatically calculate BMI may help address this problem. Additionally, electronic medical record systems could be programmed to provide suggestions for gestational weight gain counseling based on Institute of Medicine 2009 guidelines and to assist prenatal care providers in tracking their patients’ weight gain; there is evidence that prenatal care providers would accept such decision support tools embedded in their electronic medical record to assist with gestational weight gain counseling.(19)

Interestingly, 44% of respondents reported ‘routinely’ using ‘clinical impression based on appearance’ to assess their prenatal patients’ weight status. With two-thirds of Americans being overweight or obese,(20; 21) approximately 1 of 5 U.S. women being obese at delivery,(22) and 1 in 6 adults being obese across the 34 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries,(23) representing 5 of 7 continents, it is likely that weight perceptions are influenced by daily exposure to this population. There is evidence of shifts in body weight norms (24) and in provider perceptions, with Schmeid and colleagues coining the phrase ‘creeping normality’ regarding care of obese childbearing women in Australia.(25) Thus, determination of weight status by visual cues only is likely to result in an underestimate of BMI and a propensity to recommend excessive ranges of gain. This may be counteracted by our survey respondents choosing gain or ranges of gain below those actually recommended for particular BMI categories (Table 4) which may be reflective of open academic discourse and disagreement with committee recommendations(26) and/or evidence that less gain may be beneficial, especially for obese women.(27; 28)

Strengths of our study include its broad distribution to residency programs across the United States thus contributing to the generalizability of our results. We surveyed residents to access a cohort of current, active practitioners in teaching environments who we hypothesized would be exposed to new clinical guidelines. This may decrease generalizability to non-resident populations and may reflect unique barriers residents face in providing evidence-based care.(14) Despite the Institute of Medicine being specifically affiliated with the United States and seeking to provide unbiased advice pertinent to United States residents’ health and associated pertinent policy, this study is additionally generalizable outside of the U.S. as the literature reviews leading to changed gestational weight gain recommendations were based on outcomes in U.S. and European populations.(2) Similarly, international investment in this topic is evident by recent literature examining international populations, including Australia(29) and Thailand.(30) An additional strength is that this survey was distributed 8–12 months after the publication of the revised guidelines, allowing sufficient time for diffusion of the revisions. Despite the lag time, knowledge of the guidelines was minimal and consistent with McDonald et al’s reports of appropriate counseling rates.(5) (31) McDonald surveyed cohorts of prenatal patients in Canada whereas our surveyed cohort was prenatal providers in the United States; despite the geographic differences, there is little reason to believe that training priorities and translation of that training is significantly different especially with complementary results among patients and providers. Study limitations include participation self-selection which may bias our results(32) towards enhanced knowledge; thus the 2.3% who answered all knowledge-based questions correctly, may actually be an overestimate of the general resident population. The survey may not have reached a significant number of residents as residency directors and coordinators are appropriate ‘gate keepers’ to residents’ email; thus having gone through these gate keepers, we are unable to adequately calculate view, participation, or response rates.(32) According to available resources, there are approximately 10,000 Obstetrics/Gynecology and Family Medicine residents in the United States; we are unable to assess whether all residents received the survey and are confident that many did not. If however we assume a potential pool of 10,000 respondents and a respondent group of 660 residents, at a minimum, the overall response rate was 6.6%. This is likely a great underestimate given previously cited reasons for a smaller denominator than assumed in this calculation. Nonetheless, this response rate is consistent with other published web-based survey results of providers(33) with use of electronic surveys deemed acceptable amongst obstetric providers.(34)

Weight gain in pregnancy consistent with Institute of Medicine guidelines is associated with better maternal and neonatal outcomes.(2) However, while appropriate gain is highly desirable, it is achieved in only a minority of pregnancies.(1; 35) Provider counseling influences gestational weight gain(3; 4) and over-gaining is associated with postpartum weight retention and subsequent obesity(36–39). Our results suggest that resident providers are minimally aware of the new guidelines and thus are not able to provide guideline-congruent weight gain advice to their prenatal patients. The results of this study and the current obesity epidemic demand that significant efforts be made towards resident and general prenatal provider education regarding gestational weight gain guidelines, including implementation and accurate counseling of patients. These efforts would be well exerted on residents as future independent providers, early in their careers, with high potential for impacting the care and thus health of generations of women and their children.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Salary support for Dr. Waring provided by KL2TR000160.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: A portion of the findings in this manuscript were presented in abstract and poster form at the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology Annual Clinical Meeting in San Francisco, CA, May 2010. No authors of any actual or perceived conflicts of interest with regards to materials presented in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Moore Simas TA, Liao X, Garrison A, et al. Impact of updated Institute of Medicine guidelines on prepregnancy body mass index categorization, gestational weight gain recommendations, and needed counseling. J Womens Health. 2011;20(6):837–844. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cogswell ME, Scanlon KS, Fein SB, Schieve LA. Medically advised, mother’s personal target, and actual weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:616–622. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stotland NE, Haas JS, Brawarsky P, et al. Body mass index, provider advice, and target gestational weight gain. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:633–638. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000152349.84025.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald SD, Pullenayegum E, Taylor VH, et al. Despite 2009 guidelines, few women report being counseled correctly about weight gain during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205:333, e331–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabana M, Rand C, Powe N, et al. Why don’t physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282:1458–1465. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute of Medicine. Nutrition during pregnancy. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute of Health. Evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults - The evidence report. 1998 NIH Publication No. 98-4083. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Power ML, Cogswell ME, Schulkin J. Obesity prevention and treatment practices of U.S. obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:4. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000233171.20484.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phelan S, Phipps MG, Abrams B, et al. Practitioner advice and gestational weight gain. J Women Health. 2011;20(4):585–591. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stengel MR, Kraschnewski JL, Hwang SW, et al. “What my doctor didn’t tell me”: Examining health care provider advice to overweight and obese pregnant women on gestational weight gain and physical activity. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22(6):e535–3540. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) [Accessed September 17, 2013.];Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) common program requirements. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf.

- 13.Dalrymple PW, Lehmann HP, Roderer NK, Streiff MB. Applying evidence in practice: a qualitative case study of the factors affects residents’ decisions. Health Informatics J. 2010;16(3):177–188. doi: 10.1177/1460458210377469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nvan Dijk N, Hooft L, Wieringa-de Waard M. What are the barriers to resident’s practicing evidenced-based medicine? A systematic review. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1163–1170. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d4152f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellison GT, Holliday M. The use of maternal weight measurements during antenatal care. a national survey of midwifery practice throughout the United Kingdom. J Eval Clin Pract. 1997;3:303–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.1997.t01-1-00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asbee SM, Jenkins TR, Butler JR, et al. Preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy through dietary and lifestyle counseling: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:305–312. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318195baef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson CM, Strawderman MS, Reed RG. Efficacy of an intervention to prevent excessive gestational weight gain. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore Simas TA, Doyle Curiale DK, Hardy J, et al. Efforts needed to provide Institute of Medicine-recommended guidelines for gestational weight gain. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(4):777–783. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d56e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oken E, Switkowski K, Price S, et al. A qualitative study of gestational weight gain counseling and tracking. Matern Child Health J. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1158-9. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frayer C, Carroll M, Ogden C. [Accessed September 17, 2013.];Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960–1962 through 2009–2010. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_09_10/obesity_adult_09_10.htm.

- 21.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu SY, Callaghan WM, Bish CL, D’Angelo D. Gestational weight gain by body mass index among U.S. women delivering live births, 2004–2005: fueling future obesity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:271, e271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.09.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchner B. Nutrition, obesity and EU health policy. Eur J Health Law. 2011;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1163/157180911x546084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke MA, Heiland FW, Nadler CM. From “overweight” to “about right”: Evidence of generational shift in body weight norms. Obesity. 2010;18:1226–1234. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmied VA, Duff M, Dahlen HG, et al. ‘Not waving but drowning’: a study of the experiences and concerns of midwives and other health professionals caring for obese childbearing women. Midwifery. 2011;27:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Artal R, Lockwood CJ, Brown HL. Weight gain recommendations in pregnancy and the obesity epidemic. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;115(1):152–155. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c51908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiel DW, Dodson EA, Artal R, et al. Gestational weight gain and pregnancy outcomes in obese women: How much is enough? Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:752–758. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000278819.17190.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) ACOG Committee opinion no. 548: weight gain during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):210–212. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000425668.87506.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Jersey SJ, Nicholson JM, Callaway LK, Daniels LA. A prospective study of pregnancy weight gain in Australian women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;52(6):545–551. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Titapant V. Is the U.S. Institute of Medicine recommendation for gestational weight gain suitable for Thai singleton pregnant women? J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald SD, Pullenayegum E, Bracken K, et al. Comparison of midwifery, family medicine, and obstetric patients’ understanding of weight gain during pregnancy: a minority of women report correct counselling. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34(2):129–135. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)35155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasmeen S, Romano PS, Tandredi DJ, et al. Screening mammography beliefs and recommendations: a web-based survey of primary care physicians. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matteson KA, Anderson BL, Pinto SB, et al. Surveying ourselves: examining the use of a web-based approach for a physician survey. Eval Health Prof. 2011;34(4):448–463. doi: 10.1177/0163278710391086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carmichael S, Abrams B, Selvin S. The pattern of maternal weight gain in women with good pregnancy outcomes. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1984–1988. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gunderson EP, Abrams B. Epidemiology of gestational weight gain and body weight changes after pregnancy. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:261–274. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rooney BL, Schauberger CW. Excess pregnancy weight gain and long-term obesity: One decade later. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(2):245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rooney BL, Schauberger CW, Mathiason MA. Impact of perinatal weight change on long term obesity and obesity-related illnesses. Obstet Gynecol Annu. 2005;106:1349–1356. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000185480.09068.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rossner S, Ohlin A. Pregnancy as a risk factor for obesity: lessons from the Stockholm pregnancy and weight development study. Obes Res. 1995;3(Suppl 2):267s–275s. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]