Abstract

Objective

To compare the long-term survival of colorectal cancer (CRC) in young patients with elderly ones.

Methods

Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) population-based data, we identified 69,835 patients with non-metastatic colorectal cancer diagnosed between January 1, 1988 and December 31, 2003 treated with surgery. Patients were divided into young (40 years and under) and elderly groups (over 40 years of age). Five-year cancer specific survival data were obtained. Kaplan-Meier methods were adopted and multivariable Cox regression models were built for the analysis of long-term survival outcomes and risk factors.

Results

Young patients showed significantly higher pathological grading (p<0.001), more cases of mucinous and signet-ring histological type (p<0.001), later AJCC stage (p<0.001), more lymph nodes (≥12 nodes) dissected (p<0.001) and higher metastatic lymph node ratio (p<0.001). The 5-year colorectal cancer specific survival rates were 78.6% in young group and 75.3% in elderly group, which had significant difference in both univariate and multivariate analysis (P<0.001). Further analysis showed this significant difference only existed in stage II and III patients.

Conclusions

Compared with elderly patients, young patients with colorectal cancer treated with surgery appear to have unique characteristics and a higher cancer specific survival rate although they presented with higher proportions of unfavorable biological behavior as well as advanced stage disease.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies and is ranked as the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the USA [1]. The incidence of CRC in Asian countries is increasing rapidly and has been considered to be similar to that of the Western countries [2], [3]. Generally, CRC is thought to be a malignancy affecting mostly on the elderly persons, with more than 90% of patients being diagnosed after age 55 years [4]. The 2010 Annual Report to the Nation on Cancer celebrated a steady decline in the incidence of CRC in USA [5]. In sharp contrast to overall trends, the incidence of CRC in young patients appears to be increasing [5], [6], [7]. The incidence of the disease, considering patients aged between 20–40 years of age increased by 17% during the period between 1973 and 1999 [7].

CRC in the young generally regards as a higher prevalence of mucinous or poorly differentiated tumors including signet ring carcinoma and later stage, which tend to have a poorer prognosis compared to elderly patients [8], [9], [10], [11]. Some authors, however, argued that compared with the elderly patients, although the young ones have unfavorable cliniopathological characteristics, they have better, at least no worse, long-term survival rates than elderly [12], [13], [14]. Most of the published studies on CRC in young patients are single-institution experiences or limit sample sizes. In this regard, we used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registries to analysis age role on CRC long time survival after surgery.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The current SEER database consists of 17 population-based cancer registries that represent approximately 26% of the population in the United States. The SEER data contain no identifiers and are publicly available for studies of cancer-based epidemiology and health policy. The National Cancer Institute’s SEER*Stat software (Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software, www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat)(Version 8.1.2) was used to identify patients whose pathological diagnosis as invasive CRC (C18.0–20.9) between 1988, and 2003. Only patients who underwent surgical treatment with age of diagnosis between 18 and 74 years were included. Patients were excluded if they had in situ or incomplete TNM staging, with distant metastasis (M1), no evaluation on lymph nodes (LNs) or differentiation grade or histological type pathologically, died within 30 days after surgery, or multiple primary malignant neoplasm as determined by Extent of Disease Codes. Age, sex, race, TNM stage, tumor grade, tumor location, CRC–specific survival (CCSS) was assessed. The lymph nodes ratio (LNR) was calculated as the number of positive regional nodes divided by the number of regional nodes examined and defined as the rN classification. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not evaluated as the SEER registry does not include this information. TNM classification was restaged according to the criteria described in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual (7th edition, 2010). The primary endpoint of study is CCSS which was calculated from the date of diagnosis to the date of cancer specific death. Deaths attributed to the cancer of interest are treated as events and deaths from other causes are treated as censored observation.

This study was based on public data from the SEER database and we had got the permission to access the research data files with the reference number 12768-Nov2012. It didn’t include interaction with human subjects or use personal identifying information. The study did not require informed consent and was approved by the Review Board of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, Shanghai, China.

Statistical Analysis

Association of age (young and elderly) with clinicopathological parameters was analyzed by chi-square (χ2) test. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student’s t-test. Survival curves were generated using Kaplan-Meier estimates, differences between the curves were analyzed by log-rank test. Multivariable Cox regression models were built for analysis of risk factors for survival outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package SPSS for Windows, version 17 (Chicago: SPSS Inc, USA). Results were considered statistically significant when a two-tailed test of P<0.05 achieved.

Results

Patient Characteristics

We identified 69,835 eligible patients with CRC in SEER database during the 15-year study period (between 1988 and 2003). There were 37,130 (53.17%) males and 32,705(46.83%) females. The median ages in young and elderly groups were 36(15–40) and 64(41–74), respectively. The median follow-up period was 97(1–275) months. Patient demographics and pathological features are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients from SEER Database by age.

| Total | Young Group | Elderly Group | P value | |

| Characteristic | (n = 69835) | (n = 3014) | (n = 66821) | |

| Media foullow up(mo) | 112 | 98 | P<0.001 | |

| (IQR) | 58–158 | 42–135 | ||

| Years of diagnosis | P<0.001 | |||

| 1988–1993 | 16017 | 609 | 15408 | |

| 1994–1999 | 21295 | 955 | 20340 | |

| 2000–2003 | 32523 | 1450 | 31073 | |

| Sex | 0.615 | |||

| male | 37130 | 1589 | 35541 | |

| female | 32705 | 1425 | 31280 | |

| Race | P<0.001 | |||

| Caucasian | 55824 | 2183 | 53641 | |

| African American | 7390 | 431 | 6954 | |

| Others | 6443 | 391 | 6052 | |

| Unknowns | 178 | 9 | 169 | |

| Primary site | 0.434 | |||

| Colon cancer | 51372 | 2236 | 49136 | |

| Rectal cancer | 18463 | 778 | 17685 | |

| Pathological grading | P<0.001 | |||

| High/Moderate | 54812 | 2167 | 52645 | |

| Poor/undifferentiation | 12644 | 723 | 11921 | |

| Histological Type | P<0.001 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 61384 | 2455 | 58929 | |

| Mucinous cancer | 7804 | 474 | 7330 | |

| Signet-ring cancer | 647 | 85 | 562 | |

| AJCC stage | P<0.001 | |||

| I | 4563 | 133 | 4430 | |

| II | 35867 | 1384 | 34483 | |

| III | 29405 | 1497 | 27908 | |

| No. of LNs dissected | P<0.001 | |||

| <12 | 37653 | 1037 | 36616 | |

| ≥12 | 32182 | 1977 | 30205 | |

| Metastasis LNR | P<0.001 | |||

| rN0(0) | 40546 | 1521 | 39025 | |

| rN1(0.01–0.20) | 12814 | 722 | 12092 | |

| rN2(0.21–0.60) | 11482 | 541 | 10941 | |

| rN3(>0.60) | 4993 | 230 | 4763 |

Clinicopathological Differences between the Two Groups

When compared to elderly patients, in group of young ones, it was investigated that significant differences were found among the years of diagnosis (more frequent in recent years(2000–2003), P<0.001), race (less frequent in Caucasian race, p<0.001), pathological grading (more poor or undifferentiation in grade, p<0.001), histological type (more mucinous or signet-ring cancer, p<0.001), AJCC stage (more stage III, p<0.001), No. of LNs dissected (more cases with ≥12 LNs dissected, p<0.001) and LNR(more rN1, p<0.001). As regard to sex (p = 0.62) and primary site (p = 0.43), no significant differences between two groups were found. (Table 1).

Impact of Age on CRC Survival Outcomes

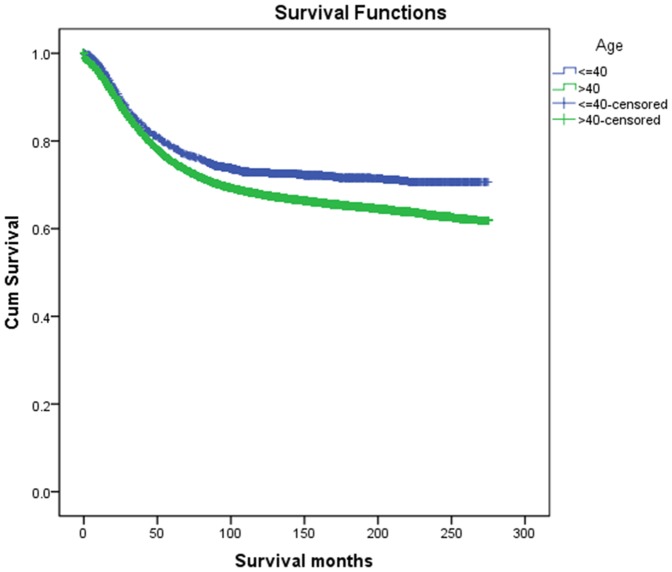

The overall 5-year CCSS was 78.6% in young group and 75.3% in elderly group, which had significant difference in univariate log-rank test (P<0.001) (Fig. 1). Besides, early year of diagnosis (P<0.001), male (P<0.001), African race (P<0.001), rectal cancer (P<0.001), poor or undifferentiation tumor grade (P<0.001), mucinous or signet-ring cancer (P<0.001), higher AJCC stage(P<0.001), less number in LNs dissection(p<0.01) and higher metastatic LNR(P<0.001), were identified as significant risk factors for poor survival on univariate analysis(Table 2). When multivariate analysis with Cox regression was performed, we convinced all these factors as independent prognostic factors (Table 3). These included age (elderly, hazard ratio (HR) 1.42, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.32–1.52), year of diagnosis (1994–1999, HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.80–0.86; 2000–2003, HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.71–0.76), gender (female, HR 0.87, 95%CI 0.85–0.90), race(African American, HR 1.19,95%CI 1.14–1.25;others, HR 1.59,95%CI 1.50–1.69), primary site(rectal cancer, HR 1.10,95%CI 1.07–1.14), pathological grading(poor or undifferentiation tumor, HR 1.32,95%CI 1.28–1.37), histological type(mucinous cancer, HR 1.10,95%CI 1.03–1.12; signet-ring cancer, HR 1.72,95%CI 1.54–1.92), AJCC stage(stage II, HR 2.91,95%CI 2.59–3.27; stage III, HR 4.83,95%CI 3.32–7.03), metastatic LNR(rN2, HR 1.92,95%CI 1.34–2.75; rN3, HR 3.23,95%CI 2.26–4.63), while the risk between rN0 and rN1 was not statistical difference(P = 0.45).

Figure 1. Survival curves in CRC patients according to age status.

Young group vs. Elderly group, χ2 = 35.84, P<0.001.

Table 2. Univariate survival analyses of CRC patients according to various clinicopathological variables.

| Variable | n | 5-year CCSS (%) | Log rank χ2 test | P | |

| Years of diagnosis | 333.65 | P<0.001 | |||

| 1988–1993 | 16017 | 70.9% | |||

| 1994–1999 | 21295 | 74.6% | |||

| 2000–2003 | 32523 | 78.3% | |||

| Sex | 105.86 | P<0.001 | |||

| male | 37130 | 74.4% | |||

| female | 32705 | 76.7% | |||

| Age | 35.84 | P<0.001 | |||

| ≤40 | 3014 | 78.6% | |||

| 41–74 | 66821 | 75.3% | |||

| Race | 195.16 | P<0.001 | |||

| Caucasian | 55824 | 76.0% | |||

| African American | 7390 | 69.3% | |||

| Others* | 6621 | 78.1% | |||

| Primary site | 144.24 | P<0.001 | |||

| Colon cancer | 51372 | 76.1% | |||

| Rectal cancer | 18463 | 73.6% | |||

| Pathological grading | 1128.17 | P<0.001 | |||

| High/Moderate | 54812 | 78.3% | |||

| Poor/undifferentiation | 12644 | 63.5% | |||

| Histological Type | 584.49 | P<0.001 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 61384 | 76.3% | |||

| Mucinous cancer | 7804 | 71.7% | |||

| Signet-ring cancer | 647 | 42.6% | |||

| AJCC stage | 7353.52 | P<0.001 | |||

| I | 4563 | 96.2% | |||

| II | 35867 | 85.4% | |||

| III | 29405 | 60.1% | |||

| No. of LNs dissected | 36.93 | P<0.001 | |||

| <12 | 37653 | 74.7% | |||

| ≥12 | 32182 | 76.3% | |||

| Metastasis LNR | 11590.57 | P<0.001 | |||

| rN0(0) | 40546 | 86.6% | |||

| rN1(0.01–0.20) | 12814 | 72.3% | |||

| rN2(0.21–0.60) | 11482 | 56.3% | |||

| rN3(>0.60) | 4993 | 36.8% | |||

*including other (American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander) and unknowns.

Table 3. Multivariate Cox model analyses of prognostic factors of CRC.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95%CI | P |

| Years of diagnosis | P<0.001 | ||

| 1988–1993 | 1.000 | ||

| 1994–1999 | 0.827 | 0.798–0.857 | |

| 2000–2003 | 0.735 | 0.710–0.760 | |

| Sex | P<0.001 | ||

| male | 1.000 | ||

| female | 0.874 | 0.850–0.899 | |

| Age | P<0.001 | ||

| ≤40 | 1.000 | ||

| 41–74 | 1.415 | 1.315–1.523 | |

| Race | P<0.001 | ||

| Caucasian | 1.000 | ||

| African American | 1.194 | 1.136–1.254 | |

| Others* | 1.593 | 1.498–1.693 | |

| Primary site | P<0.001 | ||

| Colon cancer | 1.000 | ||

| Rectal cancer | 1.104 | 1.071–1.138 | |

| Pathological grading | P<0.001 | ||

| High/Moderate | 1.000 | ||

| Poor/undifferentiation | 1.322 | 1.279–1.366 | |

| Histological Type | P<0.001 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 1.000 | ||

| Mucinous cancer | 1.075 | 1.029–1.123 | |

| Signet-ring cancer | 1.716 | 1.537–1.917 | |

| AJCC stage | P<0.001 | ||

| I | 1.000 | ||

| II | 2.905 | 2.586–3.265 | |

| III | 4.826 | 3.315–7.026 | |

| No. of LNs dissected | 0.063 | ||

| <12 | 1.000 | ||

| ≥12 | 0.973 | 0.946–1.001 | |

| Metastasis LNR | P<0.001 | ||

| rN0(0) | 1.000 | ||

| rN1(0.01–0.20) | 1.149 | 0.802–1.646 | |

| rN2(0.21–0.60) | 1.918 | 1.340–2.746 | |

| rN3(>0.60) | 3.233 | 2.257–4.633 |

*including other (American Indian/AK Native, Asian/Pacific Islander) and unknowns.

Stratified Analysis of Age on Cancer Survival Based on Different Stages

We then made further analysis of age on 5-year CCSS in each stage. The results showed that young patients were significantly associated with better 5-year CCSS than elderly patients in univariate analysis in both stage II and III(P<0.001), but not in stage I (P = 0.605)(Table 4). And age was also validated as independent survival factor in multivariate Cox regression in stage II (elderly, HR 1.71, 95%CI 1.47–2.00, p<0.001) and stage III (elderly, HR 1.33, 95%CI 1.22–1.45, p<0.001) patients(Table 5).

Table 4. Univariate analysis of Age on CCSS based on different stages.

| Variable | n | 5-year survival (%) | Log rank χ2 test | P |

| Stage I | ||||

| Age | 0.575 | 0.448 | ||

| ≤40 | 133 | 96.9% | ||

| 41–74 | 4430 | 96.2% | ||

| Stage II | ||||

| Age | 56.979 | P<0.001 | ||

| ≤40 | 1384 | 90.5% | ||

| 41–74 | 24483 | 85.2% | ||

| Stage III | ||||

| Age | 29.677 | P<0.001 | ||

| ≤40 | 1497 | 65.9% | ||

| 41–74 | 27908 | 59.8% |

Table 5. Multivariate Cox model analyses of prognostic factors of CRC on different stages.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95%CI | P |

| Stage II | |||

| Age | P<0.001 | ||

| ≤40 | 1.000 | ||

| 41–74 | 1.709 | 1.465–1.995 | |

| Stage III | |||

| Age | P<0.001 | ||

| ≤40 | 1.000 | ||

| 41–74 | 1.329 | 1.222–1.445 |

P values refer to comparison between two groups and were adjusted for years of diagnosis, sex, age, race, primary site, pathological grading, tumor histotype, No. of LNs dissected, Metastasis LNR as covariates.

Discussion

The current definition of young CRC patients remains controversial. Some studies used the cutoff age of 50 years [15], , while others used 30 years [14], [18] or 45 years [19]. But to date, majority of studies in the literature used the cutoff age of 40 years to denote a young patients with CRC [6], [12], [18], [20], [21]. This lack of a standard definition makes it difficult to make meaningful comparisons between different studies. We defined young patients using an upper limit of 40 years as most studies reported. In our study, the proportion of young patients with CRC with treatment of surgery has raised from 3.80%(609/15408) in year of 1988–1993 to 4.46%(1450/32523) in year of 1999–2003, which was consistent with the published epidemiologic feature [5], [22].

Various studies have reported poorer prognosis among young patients with CRC. Taylor et al. [21] in their review demonstrated that when compared to elderly patients, young patients less than 40 years of age presented with more advanced lesions and had lower survival rates. Similar results were reported by Marble et al [23] and Cusack et al [24]. This reduction in survival has been attributed to more advanced disease at diagnosis [6], [17], [20]. Tumor stage was very powerful factor effect long time survival rate. Poor tumor differentiation and mucinous and signet-ring cancer were also characteristic histological features in these patients [6]. It is well known that mucinous, signet-ring and poorly differentiated tumors tend to have a poorer prognosis compared to well and moderately differentiated tumors [25], Our study show that 5-year CCSS of adenocarcinoma, mucinous and signet-ring cancer was 76.3%, 71.7% and 42.6% respectively, signet-ring cancer is at extremely low rate.

In this cohort, despite the significantly higher incidence of poor prognostic factors such as poorly differentiated tumors, mucinous and signet-ring cancer, advanced AJCC stage in young group compared with the patients over 40 years of age, young CRC patients had a better 5-year CCSS, especially in stage II and stage III. This is demonstrated on both univariate and multivariate analysis. Our result is consist with some recently published articles [12], [13]. In this study, we included 3,014 young CRC patients, which is to date the largest number, and excluded CRC patients over 75 years old for short life expectation, which made our results more convincing. Young patients have a poorer biological behavior of carcinoma, but this is compensated by the better overall condition, faster postoperative recovery. In general, a good performance status is essential for the success of chemotherapy [26] and extensive lymphadenectomy. Clinicians are more inclined to gain all therapeutical options in young patients as they are at a better health condition and are more likely to tolerate toxicities associated with chemotherapy [27] while elderly patients always undertreated because of their age [28]. Adjuvant chemotherapy isn’t indication for stage I patients, which could help explaining why there weren’t significant difference in CCSS between young and elderly patients in this stage. Young patients also have a higher proportion of tumors demonstrating microsatellite instability, which are associated with a better prognosis [29]. Examination of at least 12 lymph nodes in the staging of CRC was recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and about 65.59%(1977/3014) young CRC patients met this criterion compared with 45.20%(30205/66821) in elderly patients, which difference is statistical. Evaluation of an increasing number of lymph nodes has been shown to be associated with improved survival after resection of colon cancer [30], [31], but the level of significance just failed in multivariable Cox regression models in our study (P = 0.063). we also verified metastatic LNR as an independent prognosis factors by rN classification used by Zhang et al [32].

Although this is a large population-based study evaluating prognosis of young patients with CRC, it has several potential limitations. First, the SEER database lacks several important tumor characteristics (eg, perineural invasion and lymphovascular invasion), cancer therapy (neoadjuvant and adjuvant, quality of surgery). Thus, our analyses could not adjust for these potential confounding factors. Second, this data include only patients who had undergone surgical resection for CRC. As such, this group of patients can not represent CRC patients who had irresectable tumors or refused surgical intervention for various reasons. Still, our study has its convincing power regarding young CRC good survival rate after surgery.

In summary, compared to elderly patients, young patients with CRC aged 40 and below appear to have unique characteristics and have a higher CCSS after surgery although they presented with higher proportions of unfavorable biological behavior as well as advanced stage disease.

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked SEER database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibilities of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER database.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81001055), Shanghai Pujiang Program (No.13PJD008), National High Technology Research and Development Program (863 Program, No.2012AA02A506) and Shanghai Shenkang Program (No. SHDC12012120). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A (2013) Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 63: 11–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sung JJ, Lau JY, Young GP, Sano Y, Chiu HM, et al. (2008) Asia Pacific consensus recommendations for colorectal cancer screening. Gut 57: 1166–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Byeon JS, Yang SK, Kim TI, Kim WH, Lau JY, et al. (2007) Colorectal neoplasm in asymptomatic Asians: a prospective multinational multicenter colonoscopy survey. Gastrointest Endosc 65: 1015–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atkin WS, Cuzick J, Northover JM, Whynes DK (1993) Prevention of colorectal cancer by once-only sigmoidoscopy. Lancet 341: 736–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, Eheman C, Zauber AG, et al. (2010) Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer 116: 544–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Livingston EH, Yo CK (2004) Colorectal cancer in the young. Am J Surg 187: 343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Liu JH, Etzioni DA, Livingston EH, et al. (2003) Rates of colon and rectal cancers are increasing in young adults. Am Surg 69: 866–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Varma JR, Sample L (1990) Colorectal cancer in patients aged less than 40 years. J Am Board Fam Pract 3: 54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nakamura T, Yoshioka H, Ohno M, Kuniyasu T, Tabuchi Y (1999) Clinicopathologic variables affecting survival of distal colorectal cancer patients with macroscopic invasion into the adjacent organs. Surg Today 29: 226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Heimann TM, Oh C, Aufses AH Jr (1989) Clinical significance of rectal cancer in young patients. Dis Colon Rectum 32: 473–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chan KK, Dassanayake B, Deen R, Wickramarachchi RE, Kumarage SK, et al. (2010) Young patients with colorectal cancer have poor survival in the first twenty months after operation and predictable survival in the medium and long-term: analysis of survival and prognostic markers. World J Surg Oncol 8: 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li M, Li JY, Zhao AL, Gu J (2011) Do young patients with colorectal cancer have a poorer prognosis than old patients? J Surg Res 167: 231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schellerer VS, Merkel S, Schumann SC, Schlabrakowski A, Fortsch T, et al. (2012) Despite aggressive histopathology survival is not impaired in young patients with colorectal cancer : CRC in patients under 50 years of age. Int J Colorectal Dis 27: 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kam MH, Eu KW, Barben CP, Seow-Choen F (2004) Colorectal cancer in the young: a 12-year review of patients 30 years or less. Colorectal Dis 6: 191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Benmoussa A, Badre W, Pedroni M, Zamiati S, Badre L, et al. (2012) Clinical and molecular characterization of colorectal cancer in young Moroccan patients. Turk J Gastroenterol 23: 686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. You YN, Xing Y, Feig BW, Chang GJ, Cormier JN (2012) Young-onset colorectal cancer: is it time to pay attention? Arch Intern Med 172: 287–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ben-Ishay O, Brauner E, Peled Z, Othman A, Person B, et al. (2013) Diagnosis of colon cancer differs in younger versus older patients despite similar complaints. Isr Med Assoc J 15: 284–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Neufeld D, Shpitz B, Bugaev N, Grankin M, Bernheim J, et al. (2009) Young-age onset of colorectal cancer in Israel. Tech Coloproctol 13: 201–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mitry E, Benhamiche AM, Jouve JL, Clinard F, Finn-Faivre C, et al. (2001) Colorectal adenocarcinoma in patients under 45 years of age: comparison with older patients in a well-defined French population. Dis Colon Rectum 44: 380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karsten B, Kim J, King J, Kumar RR (2008) Characteristics of colorectal cancer in young patients at an urban county hospital. Am Surg 74: 973–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Taylor MC, Pounder D, Ali-Ridha NH, Bodurtha A, MacMullin EC (1988) Prognostic factors in colorectal carcinoma of young adults. Can J Surg 31: 150–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Siegel RL, Jemal A, Ward EM (2009) Increase in incidence of colorectal cancer among young men and women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18: 1695–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marble K, Banerjee S, Greenwald L (1992) Colorectal carcinoma in young patients. J Surg Oncol 51: 179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cusack JC, Giacco GG, Cleary K, Davidson BS, Izzo F, et al. (1996) Survival factors in 186 patients younger than 40 years old with colorectal adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 183: 105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adkins RB Jr, DeLozier JB, McKnight WG, Waterhouse G (1987) Carcinoma of the colon in patients 35 years of age and younger. Am Surg 53: 141–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goodwin RA, Asmis TR (2009) Overview of systemic therapy for colorectal cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 22: 251–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chew MH, Koh PK, Ng KH, Eu KW (2009) Improved survival in an Asian cohort of young colorectal cancer patients: an analysis of 523 patients from a single institution. Int J Colorectal Dis 24: 1075–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Serra-Rexach JA, Jimenez AB, Garcia-Alhambra MA, Pla R, Vidan M, et al. (2012) Differences in the therapeutic approach to colorectal cancer in young and elderly patients. Oncologist 17: 1277–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS (2005) Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol 23: 609–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang GJ, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, Moyer VA (2007) Lymph node evaluation and survival after curative resection of colon cancer: systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 99: 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, Mayer RJ, Macdonald JS, et al. (2003) Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol 21: 2912–2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang J, Lv L, Ye Y, Jiang K, Shen Z, et al. (2013) Comparison of metastatic lymph node ratio staging system with the 7th AJCC system for colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 139: 1947–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]