Abstract

Semaphorin 3A (Sema3A) is a protein identified originally as a diffusible axonal chemorepellent. Sema3A has multifunctional roles in embryonic development, immune regulation, vascularization, and oncogenesis. Bone remodeling consists of two phases: the removal of mineralized bone by osteoclasts and the formation of new bone by osteoblasts, and plays an essential role in skeletal diseases such as osteoporosis. Recent studies have shown that Sema3A is implicated in the regulation of osteoblastgenesis and osteoclastgenesis. Moreover, low bone mass in mice with specific knockout of Sema3A in the neurons indicates that Sema3A regulates bone remodeling indirectly. This review highlights recent advances on our understanding of the role of sema3A as a new player in the regulation of bone remodeling and proposes the potential of sema3A in the diagnosis and therapy of bone diseases.

Keywords: Semaphorin 3A, bone remodeling, sensory innervation, osteoclast, osteoblast

Introduction

With the accelerated rate of population aging around the world, bone diseases, especially osteoporosis, have been a serious concern and cause an increase in the number of elderly people with sport disability and a reduction in the working population. In healthy adults, the continuous bone remodeling at a steady-state is mediated by osteoblastgenesis and osteoclastgenesis. An imbalance of bone remodeling can cause skeletal disorders such as osteoporosis and osteopetrosis.1,2 Therefore, it is important to elucidate molecular mechanism of bone remodeling to develop better approaches for the prevention and treatment of skeletal diseases .

Notably, increasing evidence suggests that bone remodeling is regulated by a variety of factors.3,4 Sema3A is a prototype of axonal guidance molecule in semaphorin family, and recent studies have demonstrated the implication of Sema3A in skeletal system.5,6 Furthermore, Sema3A-deficient mice have abnormal structures of bones and cartilaginous.7 In this review, we summarize recent advance on the investigation of the role of Sema3A in the modulation of bone remodeling.

Semaphorin signaling

Semaphorin family and the receptors

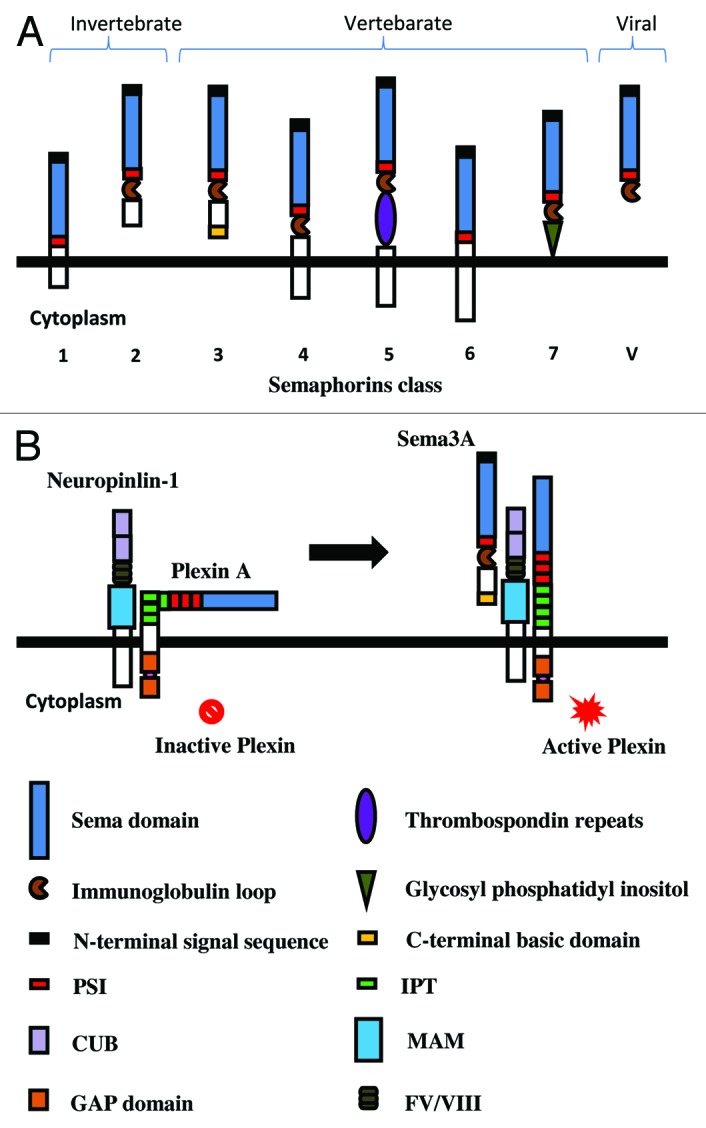

Semaphorin family proteins were originally identified in grasshopper as secreted or membrane-bound glycoproteins characterized by an N-terminal Sema domain followed by a short plexin–semaphorin–integrin (PSI) domain.8,9 Based on their C-terminal structure and similarity of amino acid, semaphorin family members are divided into eight subclasses (Fig. 1A). Classes 3–7 are present in vertebrates, whereas classes 1–2 are only found in the invertebrate so far. Classes V are encoded by viruses. In addition, different semaphorins contain different domains, such as an immunoglobulin-like domain (Ig domain) and a thrombospondin-like domain in all classes 5 and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) linkage in class 7.

Figure 1. Schematic presentation of the structure of semaphorins and the receptors. (A) The structure of emaphorins (class 1–7 and V). Semaphorins are cell surface or secreted glycoproteins characterized by an N-terminal Sema domain, which is essential for signaling, immunoglobin loop, thrombospondin domain, and glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. Class 3 molecules are secreted proteins that are distinguished by a conserved basic domain at C-terminal. (B) Sema3A signals are mediated by the receptors neuropilin 1 and plexinA. The extracellular domain of plexin contains a signal sequence, a sema domain, plexin semaphoring integrin (PSI) domains, and Ig-like plexin transcription factors (IPT). The cytosolic domain of plexin contains two GTPase-activating protein (GAP) domains. Neuropilins contain two complement binding (CUB) domains, two coagulation factor domains (FV/VIII), and a Meprin, A5, Mu (MAM) domain. Sema3A binds to the CUB domains of neuropilin and induces the conformational change of plexin, leading to the activation of intracellular signaling.

The two major receptors of semaphorins are plexins family and neuropilins (Nrp1 and Nrp2). Nine plexins have been identified in the vertebrate so far and grouped into four subfamilies (A, B, C, and D), which show high structural homology with semaphorins. Moreover, the cytoplasmic domain of plexins contains two GTPase-activating protein (GAP) domains. Neuropilins contain two complement binding (CUB) domains, two coagulation factor domains (FV/VIII), and a Meprin, A5, Mu (MAM) domain.10,11 Most membrane-bound semaphorins can bind plexins directly, whereas some secreted Sema class 3 group such as Sema3A requires neuropilins to obligate as co-receptors, which function as the ligand-binding partner in complexes (Fig. 1B). In addition, several other molecules such as intergrins have been shown to participate in the formation of the receptor complex.12,13

It is known that semaphorins play an important role as axonal guidance proteins in nervous system development; however, accumulated evidence has indicated that semaphorins have functions in a variety of tissues.5,14 Especially, several semaphorin family members are implicated in the regulation of key physiological processes, such as bone formation.15 For instance, Sema4D is secreted by osteoclasts and mediates communication between osteoclasts and osteoblasts.16-18 Sema7A regulates bone homeostasis.19 Interestingly, our recent study showed that Sema3A could regulate bone remodeling indirectly by modulating sensory nerve development.20 Therefore, in this review, we will focus on Sema3A as a example to highlight the key role of semaphorins in the regulation of bone remodeling.

Semaphorin3A

Sema3A is the first semaphorin identified in the vertebrate and acts to induce the retraction and collapse of the structure on axonal growth cone.21 Sema3A participates in the development of major structure of nervous system such as the brain, spinal cord, and peripheral nerves, and the regulation of the function of adult nervous system such as axon regeneration and neural repair.22

Sema3A has been implicated in additional physiological function such as immune responses, organogenesis, and oncogenesis. For example, Sema3A regulates the timing of tooth innervations and dental axon navigation and patterning.23,24 Since all three bones cell lineages (osteoclast, osteoblast, and osteocyte) express Sema3A and its receptors, Sema3A seems to be involved in bone development and bone homeostasis. Indeed, Behar et al. reported that sema3A-deficient mice displayed fusion of cervical bones, partial duplication of ribs, and poor alignment of the rib-sternum junctions.7

Direct regulation of bone remodeling by Sema3A

Bone remodeling is a dynamic and continuous process in which osteoblast and osteoclast reshape and replace bone during growth and after injury such as a fracture. In addition to the interaction with humoral factors, osteoclasts break down calcified bone and the osteoblasts lay down new matrix.25,26 In healthy adults, bone formation and bone resorption are maintained at a steady-state under mechanical and homeostatic regulation. As an imbalance of bone remodeling results in skeletal disorders such as osteoporosis in woman after menopause, it is important to address the precise molecular mechanisms that regulate the balance of bone remodeling from a therapeutic view.

So far, most drugs target osteoclastgenesis by reducing the rate of bone resorption such as RANKL inhibitor. However, these drugs often cause the reduction in new bone formation because of the consequent disruption of the linkage between osteoclast and osteoblast activity.27,28 Recently, Hayashi et al. found that Sema3A plays a dual role in osteoclasts and osteoblasts and is a potential therapeutic agent in bone diseases.29

Sema3A signaling in osteoclastgenesis

Osteoclats, originated from the monocyte/macrophage lineage of hematopoietic stem cells, are large and multinucleated cells, which destroy the bone extracellular matrix.30 The discovery of receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand (RANKL)/receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B (RANK)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) system led to major advances in our understanding the molecular mechanism of bone resorption. OPG is an important osteoclastgenesis inhibitor secreted from osteoblasts.31 Sema3A was contained in conditioned medium from OPG-deficient mouse calvarial cells and could inhibit osteoclast formation. Interestingly, Sema3A-deficient mice have a severe osteopenic phenotype.29 In addition, the mutant Nrp1 knockin mice (Nrpsema- mice), which lacked the Sema-binding ability, exhibited a similar phenotype to Sema3A-deficient mice. These in vivo data suggest that Nrp1 is the functional receptor of Sema3A in bone cells.29

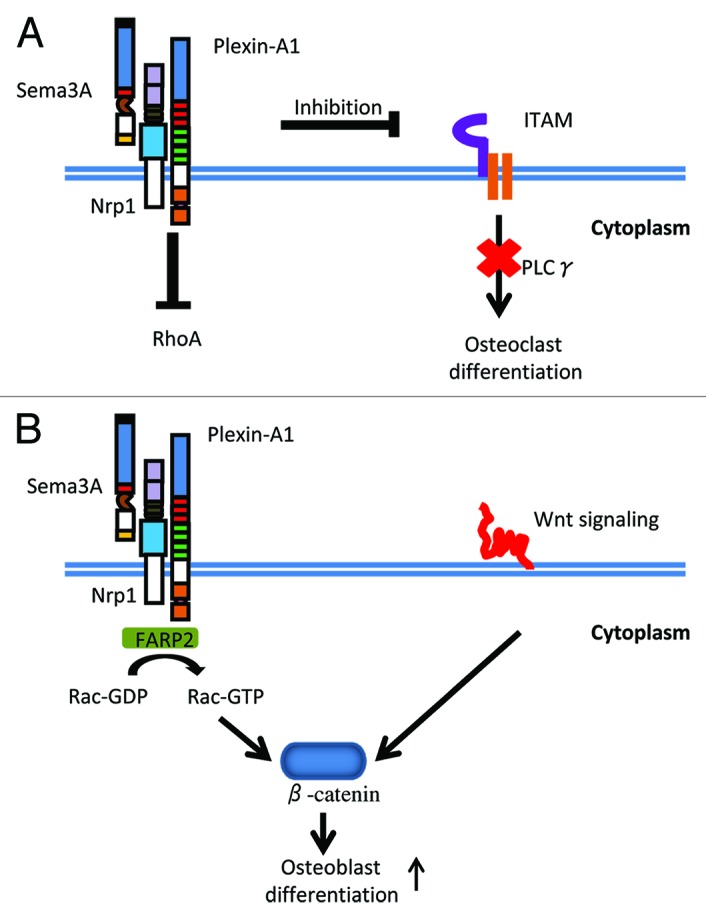

PlexinA family is the primary receptor of Sema3A and they form receptor complex with Nrp1. Takegahara et al. found that in response to Sema6D, plexinA1 associated with the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 (TREM2) and DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa (DAP12) to enhance osteoclastgenesis by activating the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) signaling.32 Sema3A-Nrp1 axis disrupted the interaction between plexinA1 and TREM2-DAP12 to affect osteoclast differentiation induced by RANKL. In addition, Sema3A blocked tyrosine phosphorylation Cγ2 (PLCγ2) and calcium oscillation (Fig. 2A).29 Semaphorin signaling is known to regulate cytoskeletal rearrangement and the Rho family of small GTPases.14,32,33 Interestingly, Sema3A-Nrp1 axis repelled ostoclast precursor cells through affecting small GTPase RhoA activation but not Rac activation.29 Our preliminary experiments confirmed that Rac activation was not involved in Sema3A-dependent inhibition of osteoclast differentiation by using dominant-negative Rac1 constructs (unpublished data).

Figure 2. Sema3A signaling in bone remodeling. (A) Sema3A-mediated regulation of osteoclastgenesis. Sema3A-Nrp1 axis inhibits PLCγ activation and calcium oscillation, leading to the inhibition of osteoclast differentiation. In addition, Sema3A-Nrp1 axis repels ostoclast precursor cells through affecting RhoA activation. (B) Sema3A-mediated regulation of osteoblastgenesis. Sema3A activates Rac1 and canonical Wnt signaling via FERM, RhoGEF, and pleckstrin domain-containing protein 2 (FARP2), leading to osteoblast differentiation.

Sema3A signaling in osteoblastgenesis

Osteoblasts originated from mesenchymal stem cells, they can differentiate into chondroncytes, adipocytes, and myoblasts, and are responsible for synthesis of bone matrix.34,35 In addition to the severe osteoclastic phenotype, both Sema3A-deficient and Nrpsema- mice had decreased amounts of the factors of bone formation based on histomorphometric analyses. In accord with the osteoblastic phenotype in vivo, primary osteobalasts from Sema-deficient mice had a defect in differentiation with decreased expression of osteoblast markers, such as Runx2 and Bglap.29 We found that Sema3A accelerated osteoblastic differentiation. In contrast, the knockdown of Sema3A in osteoblasts hampered the differentiation, and treatment with Sema3A restored the defective differentiation in Sema3A-knockdown osteoblasts.20 In addition, Sema3A expression is very high in osteoblasts (unpublished data). Taken together, these findings suggest that Sema3A is a positive regulator in oseoblastgenesis in an autocrine manner.

Intriguingly, using primary osteoblasts from sema-deficient mice, it was shown that Wnt signaling is involved in the molecular pathway by which Sema3A regulates osteoblastgenesis.29 Canonical Wnt signaling is well-known to regulate the differentiation of osteobalsts and adipocytes.36,37 Rac1, which promotes β-catenin localization in the nucleus in response to Wnt ligands, is required for the action of Sema3A on the collapse of the growth cone.38 Indeed, treatment of osteoblasts with recombinant Sema3A activated Rac1 via FERM, RhoGEF, and pleckstrin domain-containing protein 2 (FARP2), leading to nuclear accumulation of β-catenin induced by Wnt3a (Fig. 2B).29 These results are consistent with our recent report that ectopic expression of a dominant-negative form of Rac1 inhibited Sema3A-dependent osteoblast differentiation.20

Indirect regulation of skeletal sensory nerves by Sema3A

Historically, most bone biologists believe that bone remodeling is regulated in an endocrine manner. However, the discovery that leptin regulates bone mass through a hypothalamic relay shed new light on the mechanism underlying bone remodeling.39 The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) has been shown to mediate the regulation of bone remodeling by β-adrenergic receptor-2 (Adrb2).40 Thanks to the use of excited fluorescent nerve-specific markers and genetic mutant mice models, great advances have been achieved in the field of neuroskeletal biology.

Skeleton innervations

More than 50 years ago, bone innervations were shown to affect bone homeostasis in peroneal denervation experiments.41 Later it was found that sympathetic nerves exist in the bone marrow and they are positive for dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), and neuropeptide Y (NPY) by immunofluorescence staining.42-44 On the other hand, sensory fibers are detected in vertebral bones, long bones, and bone marrow. In particular, an extremely dense distribution of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (SP) is observed primarily in periosteal innervations.45-47 In addition, rapid neural growth of CGRP-positive nerves occurs during bone regeneration in the periosteum of adult rodents.48 However, so far, the molecular mechanism by which skeletal innervations regulate bone remodeling is elusive.

Recent evidence suggests that both central and peripheral nervous systems regulate bone remodeling.39 Sema3A is a well-known axon guidance molecule and functions as a chemorepellent in nervous systems. Indeed, Sema3A-deficent mice have multiple phenotypes due to abnormal neuronal innervations.7,49 Moreover, Sema3A exhibits temporal and spatial expression patterns in parallel with the establishment of innervations.7 Therefore, we speculate that Sema3A may modulate bone remodeling indirectly via regulating nervous systems.

The link between bone remodeling and sensory innervations by Sema3A

Sema3A is ubiquitously expressed in a variety of tissues, including the bone. To specifically dissect the role of Sema3A in nervous systems without the disruption from other organs, we generated neuro-specific Sema3a-deficient mice (Sema3Aneuron−/− mice) based on synapsin I-cre mice or nestin-cre mice.49-51 These Sema3Aneuron−/− mice exhibited similar phenotype to Sema3A−/− mice, such as low bone mass. In contrast, oseteoblast-specific Sema3A-deficent mice (Sema3Aosb−/− mice) did not develop any bone abnormalities.52,53 These results indicate that Sema3A in osteoblasts is not the sole cause of bone phenotype in Sema3A−/− mice in vivo.20

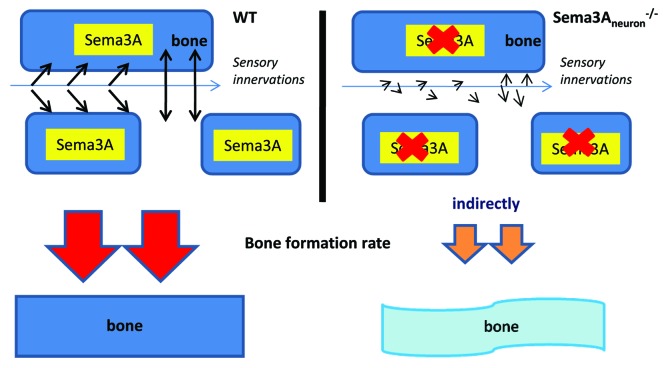

Surprisingly, skeleton innervations are significantly decreased in both Sema3A−/− mice and Sema3Aneuron−/− mice, but not in wild-type mice and Sema3Aosb−/− mice. Furthermore, sensory-positive nerves makers such as CGRP were decreased in bones of Sema3A−/− mice and Sema3Aneuron−/− mice. In contrast, DBH-positive sympathetic nerve fibers, which inhibit bone formation, were not affected significantly in Sema3A−/− mice and Sema3Aneuron−/− mice.20 Therefore, low sensory innervations we observed are consistent with low bone mass in Sema3Aneuron−/− mice (Fig. 3).54 Notably, PlexinA4−/− mice exhibited phenotypic similarity in skeleton and sensory innervations with Sema3A−/− mice and Sema3Aneuron−/− mice,55 suggesting that Sema3A-PlexinA4 pathway is important for nerve innervations in the bone. The special expression pattern of PlexinA4 in nerve and bone system may imply that the role of PlexinA4 is different from the other members of plexin family in the development of nerve and bone.20

Figure 3. Role of sensory nerves in bone remodeling may be mediated by Sema3A indirectly in mouse model. In Sema3Aneuron−/− mice, the sensory innervations are low and this is correlated with low bone mass. Therefore, sema3A is important for nerve innervations in the bone.

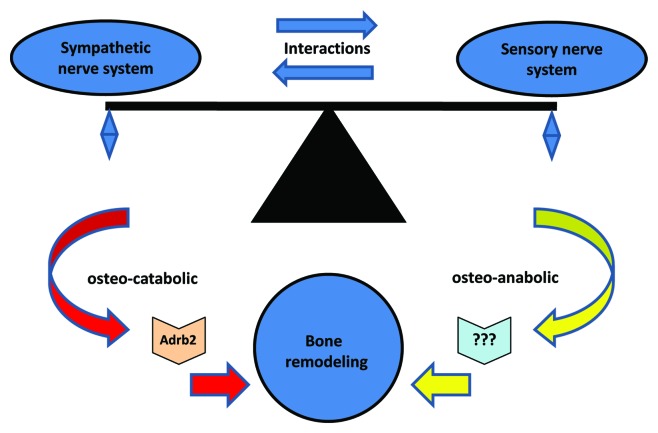

Recent studies show that there is an interaction between sensory neuron and sympathetic neuron.56,57 Based on the inhibition of bone remodeling by the sympathetic nervous system, we present an intriguing model that there is a balance between osteo-anabolic afferent sensory nerves and osteo-catabolic efferent sympathetic nerves (Fig. 4). Consequently, Sema3A may provide a link between bone remodeling and sensory innervations.

Figure 4. The hypothetical balance between osteo-anabolic afferent sensory nerves and osteo-catabolic efferent sympathetic nerves. The sympathetic nervous system regulates osteo-catabolic (bone resorbing) response via β-adrenergic receptor-2 (Adrb2) in the bone cells, while sensory nerve system regulates osteo-anabolic (bone forming) response via unidentified receptors. The balance of these actions modulate bone remodeling.

Clinical potential of Sema3A in bone diseases

To investigate the therapeutic potential of Sema3A, Hayashi et al. performed three experiments. First, intravenous injection of recombinant Sema3A led to increased osteoblastic parameters and decreased osteoclastic parameters in wild-type mice. Second, Sema3A treatment enhanced bone regeneration in a mouse model of cortical bone defect. Third, Sema3A treatment rescued bone loss in ovariectomized mice.29 Moreover, in Sema3Aneuron−/− mice bone regeneration was reduced with defective nerve innervations after bone marrow ablation.20 These data suggest that sema3A has the potential to be used for the treatment of bone diseases

Notably, Sema3A expression is proposed as a marker for systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis.58,59 Similarly, Sema3A may be a marker for skeleton disorders such as osteoporosis. In fact, familial dysautonomia patients who have loss of sensory nerves suffer from osteoporosis.60

In conclusion, Sema3A regulates bone remodeling directly by regulating the activities of osteoclasts and osteoblasts, and indirectly by engaging in sensory nerve innervations. These findings provide new insight into the role of sema3A in bone biology. Consequently, sema3A represents a novel target for the diagnosis and therapy of skeletal disorders.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/27752

References

- 1.Johnell O, Kanis JA. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1726–33. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodan GA, Martin TJ. Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science. 2000;289:1508–14. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeda S, Karsenty G. Molecular bases of the sympathetic regulation of bone mass. Bone. 2008;42:837–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takayanagi H. Osteoimmunology: shared mechanisms and crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:292–304. doi: 10.1038/nri2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roth L, Koncina E, Satkauskas S, Crémel G, Aunis D, Bagnard D. The many faces of semaphorins: from development to pathology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:649–66. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8518-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomez C, Burt-Pichat B, Mallein-Gerin F, Merle B, Delmas PD, Skerry TM, Vico L, Malaval L, Chenu C. Expression of Semaphorin-3A and its receptors in endochondral ossification: potential role in skeletal development and innervation. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:393–403. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Behar O, Golden JA, Mashimo H, Schoen FJ, Fishman MC. Semaphorin III is needed for normal patterning and growth of nerves, bones and heart. Nature. 1996;383:525–8. doi: 10.1038/383525a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semaphorin Nomenclature Committee Unified nomenclature for the semaphorins/collapsins. Cell. 1999;97:551–2. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen BJ, Robinson RA, Pérez-Brangulí F, Bell CH, Mitchell KJ, Siebold C, Jones EY. Structural basis of semaphorin-plexin signalling. Nature. 2010;467:1118–22. doi: 10.1038/nature09468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamagnone L, Comoglio PM. Signalling by semaphorin receptors: cell guidance and beyond. Trends Cell Biol. 2000;10:377–83. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01816-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Püschel AW. The function of neuropilin/plexin complexes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;515:71–80. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0119-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumanogoh A, Marukawa S, Suzuki K, Takegahara N, Watanabe C, Ch’ng E, Ishida I, Fujimura H, Sakoda S, Yoshida K, et al. Class IV semaphorin Sema4A enhances T-cell activation and interacts with Tim-2. Nature. 2002;419:629–33. doi: 10.1038/nature01037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasterkamp RJ, Peschon JJ, Spriggs MK, Kolodkin AL. Semaphorin 7A promotes axon outgrowth through integrins and MAPKs. Nature. 2003;424:398–405. doi: 10.1038/nature01790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neufeld G, Kessler O. The semaphorins: versatile regulators of tumour progression and tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:632–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giacobini P, Prevot V. Semaphorins in the development, homeostasis and disease of hormone systems. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2013;24:190–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delorme G, Saltel F, Bonnelye E, Jurdic P, Machuca-Gayet I. Expression and function of semaphorin 7A in bone cells. Biol Cell. 2005;97:589–97. doi: 10.1042/BC20040103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutton AL, Zhang X, Dowd DR, Kharode YP, Komm BS, Macdonald PN. Semaphorin 3B is a 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced gene in osteoblasts that promotes osteoclastogenesis and induces osteopenia in mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:1370–81. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Negishi-Koga T, Shinohara M, Komatsu N, Bito H, Kodama T, Friedel RH, Takayanagi H. Suppression of bone formation by osteoclastic expression of semaphorin 4D. Nat Med. 2011;17:1473–80. doi: 10.1038/nm.2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jongbloets BC, Ramakers GM, Pasterkamp RJ. Semaphorin7A and its receptors: pleiotropic regulators of immune cell function, bone homeostasis, and neural development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2013;24:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuda T, Takeda S, Xu R, Ochi H, Sunamura S, Sato T, Shibata S, Yoshida Y, Gu Z, Kimura A, et al. Sema3A regulates bone-mass accrual through sensory innervations. Nature. 2013;497:490–3. doi: 10.1038/nature12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo Y, Raible D, Raper JA. Collapsin: a protein in brain that induces the collapse and paralysis of neuronal growth cones. Cell. 1993;75:217–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80064-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He Z, Wang KC, Koprivica V, Ming G, Song HJ. Knowing how to navigate: mechanisms of semaphorin signaling in the nervous system. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:re1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.119.re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Potiron V, Nasarre P, Roche J, Healy C, Boumsell L. Semaphorin signaling in the immune system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;600:132–44. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-70956-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adams RH, Eichmann A. Axon guidance molecules in vascular patterning. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001875. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karsenty G, Kronenberg HM, Settembre C. Genetic control of bone formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:629–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teitelbaum SL, Ross FP. Genetic regulation of osteoclast development and function. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:638–49. doi: 10.1038/nrg1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid IR, Miller PD, Brown JP, Kendler DL, Fahrleitner-Pammer A, Valter I, Maasalu K, Bolognese MA, Woodson G, Bone H, et al. Denosumab Phase 3 Bone Histology Study Group Effects of denosumab on bone histomorphometry: the FREEDOM and STAND studies. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2256–65. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Odvina CV, Zerwekh JE, Rao DS, Maalouf N, Gottschalk FA, Pak CY. Severely suppressed bone turnover: a potential complication of alendronate therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1294–301. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi M, Nakashima T, Taniguchi M, Kodama T, Kumanogoh A, Takayanagi H. Osteoprotection by semaphorin 3A. Nature. 2012;485:69–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teitelbaum SL. Osteoclasts: what do they do and how do they do it? Am J Pathol. 2007;170:427–35. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyce BF, Xing L. Functions of RANKL/RANK/OPG in bone modeling and remodeling. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;473:139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takegahara N, Takamatsu H, Toyofuku T, Tsujimura T, Okuno T, Yukawa K, Mizui M, Yamamoto M, Prasad DV, Suzuki K, et al. Plexin-A1 and its interaction with DAP12 in immune responses and bone homeostasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:615–22. doi: 10.1038/ncb1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran TS, Kolodkin AL, Bharadwaj R. Semaphorin regulation of cellular morphology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:263–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdallah BM, Kassem M. Human mesenchymal stem cells: from basic biology to clinical applications. Gene Ther. 2008;15:109–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heino TJ, Hentunen TA. Differentiation of osteoblasts and osteocytes from mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2008;3:131–45. doi: 10.2174/157488808784223032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baron R, Rawadi G. Wnt signaling and the regulation of bone mass. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2007;5:73–80. doi: 10.1007/s11914-007-0006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takada I, Kouzmenko AP, Kato S. Wnt and PPARgamma signaling in osteoblastogenesis and adipogenesis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:442–7. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall A, Lalli G. Rho and Ras GTPases in axon growth, guidance, and branching. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001818. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karsenty G, Ferron M. The contribution of bone to whole-organism physiology. Nature. 2012;481:314–20. doi: 10.1038/nature10763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Levasseur R, Liu X, Zhao L, Parker KL, Armstrong D, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell. 2002;111:305–17. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ring PA. The influence of the nervous system upon the growth of bones. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 1961;43:121–40. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duncan CP, Shim SSJ. J. Edouard Samson Address: the autonomic nerve supply of bone. An experimental study of the intraosseous adrenergic nervi vasorum in the rabbit. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1977;59:323–30. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.59B3.19482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Castañeda-Corral G, Jimenez-Andrade JM, Bloom AP, Taylor RN, Mantyh WG, Kaczmarska MJ, Ghilardi JR, Mantyh PW. The majority of myelinated and unmyelinated sensory nerve fibers that innervate bone express the tropomyosin receptor kinase A. Neuroscience. 2011;178:196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bjurholm A, Kreicbergs A, Terenius L, Goldstein M, Schultzberg M. Neuropeptide Y-, tyrosine hydroxylase- and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-immunoreactive nerves in bone and surrounding tissues. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1988;25:119–25. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(88)90016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohtori S, Inoue G, Koshi T, Ito T, Watanabe T, Yamashita M, Yamauchi K, Suzuki M, Doya H, Moriya H, et al. Sensory innervation of lumbar vertebral bodies in rats. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1498–502. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318067dbf8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mach DB, Rogers SD, Sabino MC, Luger NM, Schwei MJ, Pomonis JD, Keyser CP, Clohisy DR, Adams DJ, O’Leary P, et al. Origins of skeletal pain: sensory and sympathetic innervation of the mouse femur. Neuroscience. 2002;113:155–66. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(02)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahns DA, Ivanusic JJ, Sahai V, Rowe MJ. An intact peripheral nerve preparation for monitoring the activity of single, periosteal afferent nerve fibres. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;156:140–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hukkanen M, Konttinen YT, Santavirta S, Paavolainen P, Gu XH, Terenghi G, Polak JM. Rapid proliferation of calcitonin gene-related peptide-immunoreactive nerves during healing of rat tibial fracture suggests neural involvement in bone growth and remodelling. Neuroscience. 1993;54:969–79. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taniguchi M, Yuasa S, Fujisawa H, Naruse I, Saga S, Mishina M, Yagi T. Disruption of semaphorin III/D gene causes severe abnormality in peripheral nerve projection. Neuron. 1997;19:519–30. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu Y, Romero MI, Ghosh P, Ye Z, Charnay P, Rushing EJ, Marth JD, Parada LF. Ablation of NF1 function in neurons induces abnormal development of cerebral cortex and reactive gliosis in the brain. Genes Dev. 2001;15:859–76. doi: 10.1101/gad.862101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okada S, Nakamura M, Katoh H, Miyao T, Shimazaki T, Ishii K, Yamane J, Yoshimura A, Iwamoto Y, Toyama Y, et al. Conditional ablation of Stat3 or Socs3 discloses a dual role for reactive astrocytes after spinal cord injury. Nat Med. 2006;12:829–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dacquin R, Starbuck M, Schinke T, Karsenty G. Mouse alpha1(I)-collagen promoter is the best known promoter to drive efficient Cre recombinase expression in osteoblast. Dev Dyn. 2002;224:245–51. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodda SJ, McMahon AP. Distinct roles for Hedgehog and canonical Wnt signaling in specification, differentiation and maintenance of osteoblast progenitors. Development. 2006;133:3231–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.02480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Offley SC, Guo TZ, Wei T, Clark JD, Vogel H, Lindsey DP, Jacobs CR, Yao W, Lane NE, Kingery WS. Capsaicin-sensitive sensory neurons contribute to the maintenance of trabecular bone integrity. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:257–67. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suto F, Ito K, Uemura M, Shimizu M, Shinkawa Y, Sanbo M, Shinoda T, Tsuboi M, Takashima S, Yagi T, et al. Plexin-a4 mediates axon-repulsive activities of both secreted and transmembrane semaphorins and plays roles in nerve fiber guidance. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3628–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4480-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kessler JA, Bell WO, Black IB. Interactions between the sympathetic and sensory innervation of the iris. J Neurosci. 1983;3:1301–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-06-01301.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie W, Strong JA, Mao J, Zhang JM. Highly localized interactions between sensory neurons and sprouting sympathetic fibers observed in a transgenic tyrosine hydroxylase reporter mouse. Mol Pain. 2011;7:53. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-7-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vadasz Z, Haj T, Halasz K, Rosner I, Slobodin G, Attias D, Kessel A, Kessler O, Neufeld G, Toubi E. Semaphorin 3A is a marker for disease activity and a potential immunoregulator in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:R146. doi: 10.1186/ar3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takagawa S, Nakamura F, Kumagai K, Nagashima Y, Goshima Y, Saito T. Decreased semaphorin3A expression correlates with disease activity and histological features of rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maayan C, Bar-On E, Foldes AJ, Gesundheit B, Pollak RD. Bone mineral density and metabolism in familial dysautonomia. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:429–33. doi: 10.1007/s001980200050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]