Abstract

The Kusunda people of central Nepal have long been regarded as a relic tribe of South Asia. They are, or were until recently, seminomadic hunter-gatherers, living in jungles and forests, with a language that shows no similarities to surrounding languages. They are often described as shorter and darker than neighboring tribes. Our research indicates that the Kusunda language is a member of the Indo-Pacific family. This is a surprising finding inasmuch as the Indo-Pacific family is located on New Guinea and surrounding islands. The possibility that Kusunda is a remnant of the migration that led to the initial peopling of New Guinea and Australia warrants additional investigation from both a linguistic and genetic perspective.

The Kusunda people of central Nepal are one of the few “relic” tribes found on the Indian subcontinent (the Nahali of India and the Veddas of Sri Lanka are two others). They first appeared in the ethnographic literature in 1848, when they were described by Hodgson as follows: “Amid the dense forests of the central region of Népál, to the westward of the great valley, dwell, in scanty numbers and nearly in a state of nature, two broken tribes having no apparent affinity with the civilized races of that country, and seeming like the fragments of an earlier population” (1). The Kusunda were one of these “broken tribes”; the Chepang were the other. Hodgson went on to show, however, that the Chepang were, on linguistic grounds, closely related to the Lhopa of Bhutan and must be presumed to have split off from this group and moved west at some time in the past. Hodgson had been unable to obtain any data on the Kusunda language, so nothing could be said of their possible affinity with other groups. Nine years later Hodgson published an article that contained the first linguistic data on the Kusunda language (2) as well as data on other Nepalese languages, but he offered no specific discussion of Kusunda even though his data showed quite clearly that the Kusunda language bore virtually no resemblance to any of the other languages he examined. No additional information on Kusunda appeared for more than a century until Reinhard and Toba (3) offered a brief description of the language, which provided some additional data. The final source on Kusunda appeared in an article by Reinhard in 1976 (4), but there is very little additional information that is not already found in the article by Reinhard and Toba (3).

Although Hodgson had predicted in 1848 the demise of the Kusunda in a few generations, a few Kusunda have managed to survive to the present day. Until recently they were seminomadic hunter-gatherers living in jungles and forests, and indeed their name for themselves is “people of the forest.” They are often described as short in stature and having a darker skin color than surrounding tribes. Today the few remaining Kusunda have intermarried with neighboring tribes and drifted apart, and the language has been moribund for decades, although a few elderly speakers with some knowledge of the language still survive.

The Kusunda language is a linguistic isolate, with no clear genetic connections to any other language or language family (4, 5). Curiously, however, it has often been misclassified as a Tibeto-Burman language for purely accidental reasons. Hodgson's original description of the Kusunda language (2) also included vocabularies of various Indic and Tibeto-Burman languages. In 1909, Grierson classified Kusunda as a Tibeto-Burman language (6), like that of their immediate neighbors, the Chepang, who also were forest dwellers and spoke a Tibeto-Burman language. Later scholars often assumed, without looking at the data collected by Hodgson, that Kusunda was a Tibeto-Burman language. Kusunda was classified essentially on the basis of its neighbor's language, not its own, and this error perpetuated itself similar to a scribal error in a medieval manuscript (7–9).

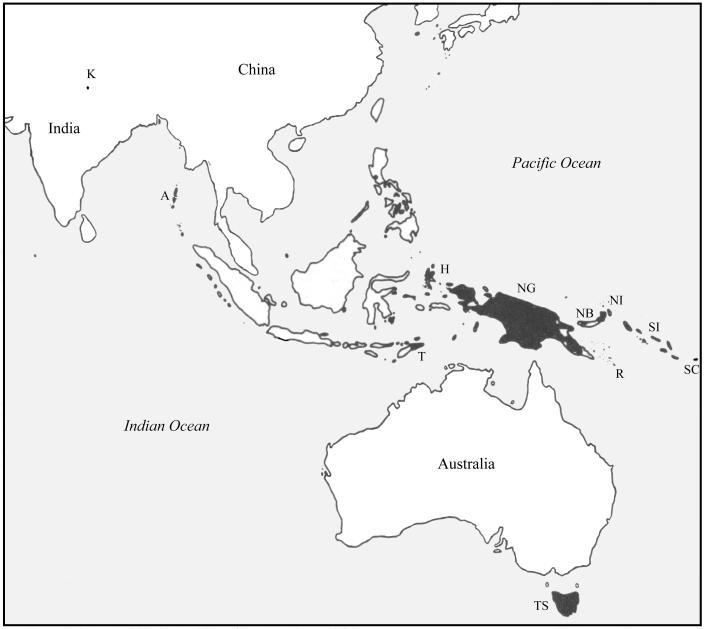

We have discovered evidence that the Kusunda language is in fact a member of the Indo-Pacific family of languages (10). The Indo-Pacific family historically occupied a vast area from the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean to the Solomon Islands in the Pacific. Today most Indo-Pacific languages are found on New Guinea, where there are >700 surviving languages. Most of the western languages have disappeared as a consequence of the Austronesian expansion, but several ancient branches have survived on the Andaman Islands, the North Moluccas (North Halmahera and its smaller neighbors), and the lesser Sundas (Timor, Alor, and Pantar). East of New Guinea, Indo-Pacific languages survive on New Britain, New Ireland, the Solomon Islands, Rossel Island, and the Santa Cruz Islands. They also were spoken in Tasmania until 1876. The distribution of Kusunda and the Indo-Pacific family is shown in Fig. 1. Although it is not possible with present evidence to demonstrate conclusively the direction of the migration that separated Kusunda from the other Indo-Pacific languages, it would seem at least plausible that Kusunda is a remnant of the original migration to New Guinea and Australia rather than a backtracking to Nepal from the region in which other Indo-Pacific languages are spoken currently.

Fig. 1.

Location of Indo-Pacific languages. K, Kusunda; A, Andaman Islands; H, Halmahera; T, Timor-Alor-Pantar; NG, New Guinea; NB, New Britain; NI, New Ireland; SI, Solomon Islands; SC, Santa Cruz Islands; R, Rossel Island; TS, Tasmania.

Recently, two molecular genetic studies (11, 12) have found that the Andamanese belong to mtDNA haplogroup M, which is found also in East Asia and South Asia and has been interpreted as “a genetic indicator of the migration of modern Homo sapiens from eastern Africa toward Southeast Asia, Australia, and Oceania” (11). In addition, the Andamanese belong to the Asia-specific Y chromosome haplogroup D. Thangaraj et al. (11) conclude that “the presence of a hitherto unidentified subset of the mtDNA Asian haplogroup M, and the Asian-specific Y chromosome D, is consistent with the view that the Andamanese are the descendants of Paleolithic peoples who might have been widely dispersed in Asia in the past.” If molecular genetic evidence can be obtained from the few remaining Kusunda, it will be interesting to determine whether it supports the conclusions we have arrived at on the basis of their language.

Grammatical Evidence

Linguistic evidence on Kusunda is sparse, limited to just three sources (2–4), and there are some discrepancies between Hodgson's 19th-century data and the late 20th-century recordings of Reinhard and Toba (3, 4). For example, Hodgson, using a simple English orthography, represents the Kusunda affricates as ch and j, indicating that he heard them as palatal: [č] and [ǰ]. Reinhard and Toba, however, represent the affricates as [ts] and [dz] and state explicitly that they are alveolar, not palatal. In this article, the source of each Kusunda form is identified as follows. Words from Reinhard and Toba (3) are taken as the default; words from Hodgson (2) are followed by (H); and words from Reinhard (4) are followed by (R). Sources for the other Indo-Pacific languages mentioned in this article are given in Supporting Appendix 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Within this relatively small and imperfect corpus there is grammatical and lexical evidence pointing toward an Indo-Pacific affinity. The strongest piece of evidence is a pronominal pattern found in the independent pronouns (involving five different parameters) that is widespread in Indo-Pacific and also found in Kusunda in precisely the same form. These five defining features are: (i) a first-person pronoun based on t; (ii) a second-person pronoun based on n or  (iii) a third-person pronoun based on g or k; (iv) a vowel alternation in the first- and second-person pronouns in which u occurs in subject forms and i in possessive (or oblique) forms; and (v) a possessive suffix -yi found on all three personal pronouns. It is significant that four of these five defining features have to do with the first- and second-person singular pronouns, which are known to be among the most stable elements of language over time (13). Indeed, it is such pronouns that have often been the first evidence for very ancient families such as Eurasiatic and Amerind.

(iii) a third-person pronoun based on g or k; (iv) a vowel alternation in the first- and second-person pronouns in which u occurs in subject forms and i in possessive (or oblique) forms; and (v) a possessive suffix -yi found on all three personal pronouns. It is significant that four of these five defining features have to do with the first- and second-person singular pronouns, which are known to be among the most stable elements of language over time (13). Indeed, it is such pronouns that have often been the first evidence for very ancient families such as Eurasiatic and Amerind.

In his original article defining the Indo-Pacific family, Greenberg (10) posited two basic pronominal patterns, n/k “I/you” and t/ ∼ n “I/you,” and he suggested that the second set originally had a possessive function. However, subsequent research has cast doubt on the antiquity of second-person k, the distribution of which is largely confined to New Guinea itself. In any event, it is the second pattern that Kusunda shares with Indo-Pacific. One finds both

∼ n “I/you,” and he suggested that the second set originally had a possessive function. However, subsequent research has cast doubt on the antiquity of second-person k, the distribution of which is largely confined to New Guinea itself. In any event, it is the second pattern that Kusunda shares with Indo-Pacific. One finds both  i and ni as the second-person pronoun; Greenberg surmised that

i and ni as the second-person pronoun; Greenberg surmised that  i had been the original form and had changed to ni in some languages as a simple sound change and in others to ni by analogy with the very widespread na “I” of the first pronominal pattern. Greenberg did not notice, however, in his pioneering article either the vowel alternation or the possessive suffix -yi. Table 1 shows the first-, second-, and third-person pronouns for Kusunda and selected Indo-Pacific languages.

i had been the original form and had changed to ni in some languages as a simple sound change and in others to ni by analogy with the very widespread na “I” of the first pronominal pattern. Greenberg did not notice, however, in his pioneering article either the vowel alternation or the possessive suffix -yi. Table 1 shows the first-, second-, and third-person pronouns for Kusunda and selected Indo-Pacific languages.

Table 1. An Indo-Pacific pronominal pattern.

| Kusunda | Juwoi | Bo | Galela | Seget | Karon Dori | Kuot | Savosavo | Bunak | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| l | chi (H) | tui | tu-lΛ | to | tet | tuo | -tuo | ne- | |

| tsi | |||||||||

| tshi (R) | |||||||||

| my | chí-yi (H) | tii-ye | ti-e | ǰi “me” | n-ie | ||||

| you | nu (H) | ηui | ηu-lΛ | no | nen | nuo | -nuo | no | e- |

| nu | |||||||||

| nu (R) | |||||||||

| your | ní-yí (H) | ηii-ye | ni “thee” | Ø-ie | |||||

| he/she | gida (H) | kitε | kitε | gao | go | gi | |||

| git | |||||||||

| his/hers | gida-yí (H) | g-ie | |||||||

| gidi |

In Kusunda the vowel alternation has only been preserved in the second person, having been eliminated through analogy in the first-person form. Furthermore, first-person *t- has been palatalized to ch- (H), ts-, or tsh- (R) under the influence of the following -i. Such a sound change is extremely common in the world's languages, and in the present case we can be sure that the original consonant was t-, because t- has been preserved in both the object form ton “me” and in first-person plural to- i “we” (-

i “we” (- i is a plural suffix). In addition to the independent pronouns, the consonantal base also indicates the verbal subject: Kusunda t- “I,” n- “you,” g- “he,” Bea d- “I,”

i is a plural suffix). In addition to the independent pronouns, the consonantal base also indicates the verbal subject: Kusunda t- “I,” n- “you,” g- “he,” Bea d- “I,”  - “you,” Onge

- “you,” Onge  - “you,” g- “he,” West Makien tV- “I,” nV “you,” and Brat t- “I,” n- “you.”

- “you,” g- “he,” West Makien tV- “I,” nV “you,” and Brat t- “I,” n- “you.”

The other Indo-Pacific languages in Table 1 have preserved different portions of the original system. It is best preserved in the Andaman Islands (Juwoi, Bo) and North Halmahera (Galela), whereas in Western New Guinea (Seget, Karon Dori), New Britain (Kuot), and the Solomon Islands (Savosavo), only the consonants are preserved, in some cases only partially. The final language in Table 1, Bunak, is spoken on Timor and obviously does not preserve either the first-person t or second-person  /n; it does, however, preserve third-person gi, and the possessive suffix is attached to all three pronouns, just as in Kusunda.

/n; it does, however, preserve third-person gi, and the possessive suffix is attached to all three pronouns, just as in Kusunda.

Certainly this unique pronominal pattern shared by Kusunda and Indo-Pacific languages cannot be a case of accidental convergence, because the probability that Kusunda could have invented this intricate pattern independently is vanishingly small. Borrowing is equally unlikely, because there is no evidence that Kusunda has ever been in contact with any Indo-Pacific language.

Two other grammatical formatives shared by Kusunda and Indo-Pacific are demonstrative pronouns based on t and n.

This. Kusunda ta (H) “this,” yit “that” = Indo-Pacific: Puchikwar ite, Juwoi ete, Abui i(t)-do, Konda ete, Itik ide, Biaka te “this, he,” Kwomtari it

“this, he,” Kwomtari it “he,” Timbe idâ “this, that,” Selepet eda, Marind iti-, Minanibai eti “he,” Humene ida.

“he,” Timbe idâ “this, that,” Selepet eda, Marind iti-, Minanibai eti “he,” Humene ida.

That. Kusunda na “this” = Indo-Pacific: West Makian ne “this,” Abun ne “that (specific), the, he,” (mo-)ne “there,” Brat no, Tabla na “this,” Sentani nie, Urama na, Tate ne, Dimir ne-t “this.”

Lexical Evidence

Complementing the grammatical evidence are a number of lexical similarities that also point to an Indo-Pacific affinity. Some of the most convincing are given below. We do not give here all the supporting etymologies or all the supporting forms for each etymology. Rather, we have chosen for each etymology a sample of the forms from different regions of the Indo-Pacific family. The meaning of each form is the same as the head meaning unless specified otherwise.

Breast. Kusunda ambu = Indo-Pacific: Sawuy a:m, Korowai am, Wambon om, Ivori aamugo , Gogodala omo, Gaima omo “milk,” Waia amo, Gibaio a:mo:, Wabuda amo, Tebera ami, Ekagi ama, Chimbu amu-na, Wahgi am, Purari ame, Yekora ami, Yoda amu, Koita amu, Neme yama, Morawa ama, Arawum ammu, Usu amu-, Kamba auma, Biyom ami, Katiati ama, Musak amtt, Tani ame, Wanembre emi.

, Gogodala omo, Gaima omo “milk,” Waia amo, Gibaio a:mo:, Wabuda amo, Tebera ami, Ekagi ama, Chimbu amu-na, Wahgi am, Purari ame, Yekora ami, Yoda amu, Koita amu, Neme yama, Morawa ama, Arawum ammu, Usu amu-, Kamba auma, Biyom ami, Katiati ama, Musak amtt, Tani ame, Wanembre emi.

Daylight. Kusunda jina ïkya (H) “light” = Indo-Pacific: Onge eke “sun,” ekue “day, today,” Momuna iki ∼ iki “sun,” Tabla yakau “morning,” Tofamna yaku “sun,” Fas y k

k v

v “sun,” Bisorio yagi “sun,” Enga ya

“sun,” Bisorio yagi “sun,” Enga ya ama “morning,” Tunjuamu yagu “day,” Gidra yuge-bibese (-bibese “day”).

ama “morning,” Tunjuamu yagu “day,” Gidra yuge-bibese (-bibese “day”).

Dog. Kusunda agai (H), ag i = Indo-Pacific: Woisika wa

i = Indo-Pacific: Woisika wa gu, Sentani yoku, Grand Valley Dani yekke ∼ yege, South Ngalik ye

gu, Sentani yoku, Grand Valley Dani yekke ∼ yege, South Ngalik ye ge, Aghu ya

ge, Aghu ya gi, Kaeti a

gi, Kaeti a ga, Yelmek agoa, Noraia aga, Gidra yauga, Siroi age.

ga, Yelmek agoa, Noraia aga, Gidra yauga, Siroi age.

Earth/Ground. Kusunda doma (H) “earth,” tumái (H) “below” = Indo-Pacific: Tobelo timi “underneath,” Kwesten tum, Mombum tumor, Dibiri toma, Grand Valley Dani tom ∼ dom, Ngalik dom, Fasu tomo “underneath,” Sene dome “underneath,” Gende teme “underneath,” Yeletnye tyamï.

Egg. Kusunda gwá ∼ góä (H), goa = Indo-Pacific: Onge gwagane “turtle egg,” Tanglupui kwa “fruit,” Bunak otel go “fruit” (otel “tree”), Kampong Baru uku, Inanwatan go u, Solowat gu ∼ go, Eritai oko, Waritai ko, Asmat oka, Demta kuku, Sangke kwe-kwe, Sko ku, Ngala gwi, Moni ugwa ∼ ua “fruit,” Oksapmin gwe “egg, seed,” Menya qwi, Amele wagbo, Atemple aku.

u, Solowat gu ∼ go, Eritai oko, Waritai ko, Asmat oka, Demta kuku, Sangke kwe-kwe, Sko ku, Ngala gwi, Moni ugwa ∼ ua “fruit,” Oksapmin gwe “egg, seed,” Menya qwi, Amele wagbo, Atemple aku.

Eye. Kusunda chining (H), ta-inin, ini (R) = Indo-Pacific: Warapu ini, Oirata ina, Woisika -e

(R) = Indo-Pacific: Warapu ini, Oirata ina, Woisika -e , Kui -en, Abui -e

, Kui -en, Abui -e , Yahadian ni, Mor na(-)na, West Kewa ini, Koiari ni “eye, face,” Magi ini, Morara ni

, Yahadian ni, Mor na(-)na, West Kewa ini, Koiari ni “eye, face,” Magi ini, Morara ni i, Yabura ni

i, Yabura ni aba, Yareba niapa.

aba, Yareba niapa.

Father1. Kusunda m m “older brother,” m

m “older brother,” m m (R) “older brother, father's sister's older son, mother's sister's older son” = Indo-Pacific: Abui mama, Moi -mam-, Arandai mame, Eipo mam “mother's brother,” Demta mami, Manambu mam “older brother,” Angoram mam, Korowai mom “mother's brother,” Huli mama “grandfather,” Kobon mam “brother,” Kate mama

m (R) “older brother, father's sister's older son, mother's sister's older son” = Indo-Pacific: Abui mama, Moi -mam-, Arandai mame, Eipo mam “mother's brother,” Demta mami, Manambu mam “older brother,” Angoram mam, Korowai mom “mother's brother,” Huli mama “grandfather,” Kobon mam “brother,” Kate mama -, Kwale mama, Pulabu mama, Saep mam, Jilim momo, Bongu mem, Kare momo-, Sihan meme-, Samosa mame-, Wamas mama-, Garuh mam, Mugil -mam, Kuot mamo, Baining mam, Taulil mama, Baniata mama.

-, Kwale mama, Pulabu mama, Saep mam, Jilim momo, Bongu mem, Kare momo-, Sihan meme-, Samosa mame-, Wamas mama-, Garuh mam, Mugil -mam, Kuot mamo, Baining mam, Taulil mama, Baniata mama.

Father2. Kusunda yei = Indo-Pacific: Isam eya, Bauzi ai, Gresi aya, Nimboran aya, Taikat aya, Yuri ay , Dera aya, Kwomtari ayæ

, Dera aya, Kwomtari ayæ , Busa aiya(

, Busa aiya( ), Amto aiya, Urat yai, Yis aya, Seti aya, Wiaki yaye, Hewa aiya, Amal aya, Siagha aye, Dibolug iaia, Ekagi aiya “great grandfather,” Sausi ai- “older sibling (same sex),” Danaru aya “older sibling (same sex),” Utu aya, Baniata ai.

), Amto aiya, Urat yai, Yis aya, Seti aya, Wiaki yaye, Hewa aiya, Amal aya, Siagha aye, Dibolug iaia, Ekagi aiya “great grandfather,” Sausi ai- “older sibling (same sex),” Danaru aya “older sibling (same sex),” Utu aya, Baniata ai.

Fire. Kusunda já (H), dza, dza (R) = Indo-Pacific: Pawaian sia, Tebera si, Bisorio tseya “tree, fire,” Gahuku dza “tree,” Kamano zafa “tree,” Gadsup yaa(-ni) “tree,” Kate dza- “(it) burns,” Mape dza- “(it) burns,” Burum dze- “(it) burns,” Nabak dzi- “(it) burns,” Selepet si- “(it) burns,” Aeka (d)zi, Orokaiva dzii.

(R) = Indo-Pacific: Pawaian sia, Tebera si, Bisorio tseya “tree, fire,” Gahuku dza “tree,” Kamano zafa “tree,” Gadsup yaa(-ni) “tree,” Kate dza- “(it) burns,” Mape dza- “(it) burns,” Burum dze- “(it) burns,” Nabak dzi- “(it) burns,” Selepet si- “(it) burns,” Aeka (d)zi, Orokaiva dzii.

Give. Kusunda ái (H), ya-gan, ya-wu “give! (imperative)” = Indo-Pacific: Juwoi a-, Jarawa a :ya, Bale oa-, Brat -e, Hatam -yai “take, give,” Sentani ye, Manem ya, Elepi yau, Kamasau nieg “give it to me,” Wambon yo-, Riantana y , Maklew -ai-, Gidra ai(o), Northeast Kiwai ai.

, Maklew -ai-, Gidra ai(o), Northeast Kiwai ai.

Knee. Kusunda tugutu = Indo-Pacific: Onge i-tokwage “elbow,” Bale togo “wrist,” Puchikwar togur “ankle,” Juwoi togar “ankle,” Sahu dodo a “joint,” Karas ta

a “joint,” Karas ta gum “elbow,” Iha -tu

gum “elbow,” Iha -tu un “elbow, knee,” Baham -tu

un “elbow, knee,” Baham -tu gon “elbow, knee,” Kampong Baru -tuguno “elbow,” Arandai -tuge-do “elbow,” Bo na-toku “elbow” (na- “arm”), South Ngalik -(e)dokodu, Biami toku “elbow,” Kapriman sεthukhwa “elbow,” Keladdar tu

gon “elbow, knee,” Kampong Baru -tuguno “elbow,” Arandai -tuge-do “elbow,” Bo na-toku “elbow” (na- “arm”), South Ngalik -(e)dokodu, Biami toku “elbow,” Kapriman sεthukhwa “elbow,” Keladdar tu “elbow,” Kimaghama tu

“elbow,” Kimaghama tu kiε “elbow,” Karima si-tuku “elbow” (si- “arm”), Kebenagara du

kiε “elbow,” Karima si-tuku “elbow” (si- “arm”), Kebenagara du wat “elbow,” Tonda do

wat “elbow,” Tonda do odi “elbow,” Kesawai toko “elbow, knee,” Pulabu tu

odi “elbow,” Kesawai toko “elbow, knee,” Pulabu tu gai “elbow,” Musar tukuma

gai “elbow,” Musar tukuma “elbow.”

“elbow.”

Liver. Kusunda kammu, qamu (R) = Indo-Pacific: Kauwerawet okum, Agob kam(o) “belly, stomach, guts,” Gidra komu “belly, guts,” Karima kamo, Binandare gomo, Sausi kamo, Siroi gamu, Kwato kamamu, Panim gem -, Silopi kemu-, Utu gemu-, Saruga gam-, Musak kumu “liver, belly,” Mugil -gem “belly,” Dimir kamema

-, Silopi kemu-, Utu gemu-, Saruga gam-, Musak kumu “liver, belly,” Mugil -gem “belly,” Dimir kamema “lung,” Korak -gom, Ulingan kema, Musar gema “lung.”

“lung,” Korak -gom, Ulingan kema, Musar gema “lung.”

Morning. Kusunda gorak (H) “tomorrow,” goraq “tomorrow,” gora dzi “this morning” = Indo-Pacific: Onge gegariko-, Kosarek kwelek-nak, Bine koroke, Kunini korokerage, Meriam gerag

dzi “this morning” = Indo-Pacific: Onge gegariko-, Kosarek kwelek-nak, Bine koroke, Kunini korokerage, Meriam gerag , Enga koraka “day,” Moere kuru-kia, Sulka kolkha.

, Enga koraka “day,” Moere kuru-kia, Sulka kolkha.

Mountain. Kusunda dibi o

o “hill” = Indo-Pacific: Sahu tubu “summit,” Iha t

“hill” = Indo-Pacific: Sahu tubu “summit,” Iha t ber, Kosarek dub “mountain peak,” Suki dipra “hill,” Foe tuma ∼ duma, Yaben tab

ber, Kosarek dub “mountain peak,” Suki dipra “hill,” Foe tuma ∼ duma, Yaben tab :nu, Bilua sopu.

:nu, Bilua sopu.

River. Kusunda wide “flow (noun)” = Indo-Pacific: Baham weǰa, Iha wadar, Puragi owedo, Aikwakai wetai, Siagha wedi, Pisa wadi, Aghu widi, Kombai wodei, South Kati ok-wiri (ok- “water”), Awin waiduo “Fly River.”

“flow (noun)” = Indo-Pacific: Baham weǰa, Iha wadar, Puragi owedo, Aikwakai wetai, Siagha wedi, Pisa wadi, Aghu widi, Kombai wodei, South Kati ok-wiri (ok- “water”), Awin waiduo “Fly River.”

Root. Kusunda itak “root, tuber” = Indo-Pacific: Bojigiab cok, Juwoi cdk-, Bale cag-, Moni taki, Bogaya tako, Binumarien tuka, Wiru teke, Kire thok.

Run. Kusunda gorgo-wóto (H) = Indo-Pacific: Gogodala gigira, Pulabu guru-, Usino gururw, Danaru  guruguru-, Jilim guru-, Rerau gur-, Duduela guri-, Male gur-, Bemal gurgure-, Sihan ku

guruguru-, Jilim guru-, Rerau gur-, Duduela guri-, Male gur-, Bemal gurgure-, Sihan ku ure-, Isebe guguli-, Panim gugul-, Bau gu

ure-, Isebe guguli-, Panim gugul-, Bau gu ur-, Baimak kura-, Gal gur-, Sulka guru

ur-, Baimak kura-, Gal gur-, Sulka guru , Buin kuro-.

, Buin kuro-.

Sand. Kusunda g li = Indo-Pacific: Sougb gεria, Tao-Sumato giri, Podopa kekere ∼ gegera, Keuru kekelea, Orokolo kekele, Elema kekere, Opao kekere, Kosarek kirik-a

li = Indo-Pacific: Sougb gεria, Tao-Sumato giri, Podopa kekere ∼ gegera, Keuru kekelea, Orokolo kekele, Elema kekere, Opao kekere, Kosarek kirik-a er, Yafi g

er, Yafi g l

l k ∼ g

k ∼ g r

r k, Dera g

k, Dera g l

l k.

k.

Short. Kusunda poto = Indo-Pacific: Fayu bosa “small,” Sehudate buse “small,” Monumbo put, Bahinemo botha, Northeast Tasmanian pute ∼ pote “small,” Southeast Tasmanian pute “small,” Middle Eastern Tasmanian pote “small.”

= Indo-Pacific: Fayu bosa “small,” Sehudate buse “small,” Monumbo put, Bahinemo botha, Northeast Tasmanian pute ∼ pote “small,” Southeast Tasmanian pute “small,” Middle Eastern Tasmanian pote “small.”

Shoulder. Kusunda p naq “shoulder strap for net bag” = Indo-Pacific: Kede ben, Puchikwar ben “shoulder blade,” Bojigiab ben, Iha mbe

naq “shoulder strap for net bag” = Indo-Pacific: Kede ben, Puchikwar ben “shoulder blade,” Bojigiab ben, Iha mbe ∼ nbe

∼ nbe , Kwerba pan ∼ ban “upper arm,” Manambu ban “back,” Yelogu bw

, Kwerba pan ∼ ban “upper arm,” Manambu ban “back,” Yelogu bw ny

ny gïr “back,” Murik pinagep ∼ phinagemb, Pogaya peni, Tirio pauna, Yei mbi

gïr “back,” Murik pinagep ∼ phinagemb, Pogaya peni, Tirio pauna, Yei mbi g, Waia bena, North East Kiwai bena, Ipikoi beno, Fuyuge bano “spine.”

g, Waia bena, North East Kiwai bena, Ipikoi beno, Fuyuge bano “spine.”

Today. Kusunda ibe “today,” ib “now” = Indo-Pacific: Inanwatan abo “morning,” Momuna abee, Taikat yabui “morning,” Kwoma aφa, Washkuk apa, Yei abete, Bugi yabada “day, sun,” Ekagi abata “morning,” Pole ambi “today,” ambi-ati “now,” Awa apiae ∼ ahbiyah “tomorrow,” Lemio yampir “dawn,” Usu ib

“now” = Indo-Pacific: Inanwatan abo “morning,” Momuna abee, Taikat yabui “morning,” Kwoma aφa, Washkuk apa, Yei abete, Bugi yabada “day, sun,” Ekagi abata “morning,” Pole ambi “today,” ambi-ati “now,” Awa apiae ∼ ahbiyah “tomorrow,” Lemio yampir “dawn,” Usu ib te “tomorrow,” Bongu yamba “tomorrow,” Garuh abera “morning,” Atemple ambïre “tomorrow, yesterday,” Yaben balima “tomorrow,” Siwai imba “now.”

te “tomorrow,” Bongu yamba “tomorrow,” Garuh abera “morning,” Atemple ambïre “tomorrow, yesterday,” Yaben balima “tomorrow,” Siwai imba “now.”

Tree. Kusunda í (H), yi, ii (R) = Indo-Pacific: Sentani i “fire,” Biaka yei “fire,” Kwomtari i

“fire,” Kwomtari i “fire,” Rocky Peak yεyu “fire,” Siagha yi, Kombai e, Girara ei, Gogodala i, Kairi i “tree, fire,” Tumu ii, Kibiri i, Mena

“fire,” Rocky Peak yεyu “fire,” Siagha yi, Kombai e, Girara ei, Gogodala i, Kairi i “tree, fire,” Tumu ii, Kibiri i, Mena  i, Pawaian i(n), Kasua i, Pa ĩ, Angaataha i-patï [-patï (class prefix)], Fuyuge i(-ye) “tree, wood,” Zia i, Notu yi, Yeletnye yi.

i, Pawaian i(n), Kasua i, Pa ĩ, Angaataha i-patï [-patï (class prefix)], Fuyuge i(-ye) “tree, wood,” Zia i, Notu yi, Yeletnye yi.

Unripe. Kusunda kátuk (H) “bitter,” qatu “bitter” = Indo-Pacific: Kede kat “bad,” Chariar kede “bad,” Juwoi kadak “bad (character),” Moi kasi, Biaka kwat

“bad,” Juwoi kadak “bad (character),” Moi kasi, Biaka kwat k

k “green,” Grand Valley Dani katekka “green,” Foe khasigi, Siagha kadaγai, Kaeti ketet, Orokolo kairuka “green,” Doromu kati, Northeast Tasmanian kati “bad,” Southeast Tasmanian kati “bad.”

“green,” Grand Valley Dani katekka “green,” Foe khasigi, Siagha kadaγai, Kaeti ketet, Orokolo kairuka “green,” Doromu kati, Northeast Tasmanian kati “bad,” Southeast Tasmanian kati “bad.”

Woman. Kusunda puan “co-wife” = Indo-Pacific: Bunak pana ∼ fana “woman, wife,” Oirata panar “female (of animal),” Moni pane “girl,” Brat vaniya, Yava wanya, Pole wena, West Kewa wena, Forei wa :nyi “wife,” Yekora bana, Dumpu fan, Kolom p no, Tauya fena

no, Tauya fena a.

a.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This article was written as part of the Santa Fe Institute's program on the Evolution of Human Languages, directed by Murray Gell-Mann, and we gratefully acknowledge their support, the support of City University of Hong Kong (Grants 901001 and CERG 9040781 to W.S.-Y.W., Principal Investigator), where part of the article was written, and the invaluable assistance of Ruth Thurman at the Summer Institute of Linguistics office in Papua, New Guinea.

References

- 1.Hodgson, B. H. (1848) J. Asiat. Soc. Bengal 17, 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodgson, B. H. (1857) J. Asiat. Soc. Bengal 26, 317–332. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinhard, J. & Toba, T. (1970) A Preliminary Linguistic Analysis and Vocabulary of the Kusunda Language (Summer Institute of Linguistics, Kirtipur, Nepal).

- 4.Reinhard, J. (1976) J. Inst. Nepal Asian Stud. 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Driem, G. (2001) Languages of the Himalayas (Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands), Vol. 1, p. 258. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grierson, G. A., ed. (1909) Linguistic Survey of India (Banarsidass, Delhi, India), Vol. 3, Part 1, pp. 399–405. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voegelin, C. F. & Voegelin, F. M. (1977) Classification and Index of the World's Languages (Elsevier, New York).

- 8.Ruhlen, M. (1991) A Guide to the World's Languages (Stanford Univ. Press, Stanford, CA), Vol. 1.

- 9.Grimes, B. F., ed. (1992) Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Summer Institute of Linguistics, Dallas), 12th edition.

- 10.Greenberg, J. H. (1971) in Current Trends in Linguistics, ed. Sebeok, T. A. (Mouton, The Hague, The Netherlands), Vol. 8, pp. 807–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thangaraj, K., Singh, L., Reddy, A. G., Rao, V. R., Sehgal, S. C., Underhill, P. A., Pierson, M., Frame, I. G. & Hagelberg, E. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endicott, P., Gilbert, M. T., Stringer, C., Lalueza-Fox, C., Willerslev, E., Hansen, A. J. & Cooper, A. (2003) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 178–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolgopolsky, A. (1986) in Typology, Relationship and Time, eds. Shevoroshkin, V. V. & Markey, T. L. (Karoma, Ann Arbor, MI), pp. 27–50.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.