Abstract

Research has established the coincidence of parental alcohol and other drug (AOD) use and child maltreatment, but few studies have examined the placement experiences and outcomes of children removed due to parental AOD use. The present study examines the demographic characteristics and placement experiences of a sample of children removed from their homes as a result of parental AOD use (n=1,333), first in comparison to the remaining sample of children in foster care (n=4554), then to a matched comparison group of children in foster care who were removed for other reasons (n=1333). Relative to the comparison sample, children removed for parental AOD use are less likely to experience co-occurring removal due to neglect and physical or sexual abuse, and are more likely to be placed in relative foster care. In addition, these children remain in care longer, experience similar rates of reunification, and have significantly higher rates of adoption.

The co-occurrence of parental alcohol and other drug (AOD) use and child maltreatment has been recognized by state and federal agencies as a growing concern, such that parental AOD abuse and involvement in illegal drug activity is recognized in the child protection statutes of approximately 45 states (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2006), and is a main contributor to out-of-home placements (Kelleher, Chaffin, Hollenberg, & Fischer, 1994). This has prompted the development of new programs to address the needs of AOD-affected children and families in the child welfare system (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2005). Compared to parents who do not use substances, AOD-using parents have lower scores on measures of parenting knowledge and behavior (Velez et al., 2004), report higher levels of personal and environmental stress (Nair, Schuler, Black, Kettinger, & Harrington, 2003), and are significantly more likely to abuse and neglect their children over time, even after controlling for significant social and demographic risk factors (Chaffin, Kelleher, & Hollenberg, 1996). As a result of these co-occurring risk factors, children born to AOD-involved parents experience diminished functioning in the areas of social, emotional, physical, and behavioral health (Johnson & Leff, 1999).

Parental AOD use is present in one-third to two-thirds of all CPS cases (Dore, Doris, & Wright, 1995), with even higher rates for court-involved samples (Besinger, Garland, Litrownik, & Landsverk, 1999). Parental AOD use also is a risk factor for CPS investigation, substantiated maltreatment, and foster care placement (Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 1999). Following an initial maltreatment investigation, children of AOD-involved parents are more likely to be re-reported for maltreatment (Connell, Bergeron, Katz, Saunders, & Tebes, in press; English, Marshall, Brummel, & Orme, 1999), and the reports are more likely to be substantiated (Fuller & Wells, 2000; Wolock & Magura, 1996; Wolock, Sherman, Feldman, & Metzger, 2001). Children of AOD-involved parents also are more likely to be removed from the home (Kelley, 1992), and are more likely to reenter foster care following reunification (Frame, Berrick, & Brodowski, 2000; Miller, Fisher, Fetrow, & Jordan, 2006; Terling, 1999).

Prior research suggests that children of AOD-involved parents differ from other children involved with CPS. These children are more likely to be born to single parents, are younger, and are more likely to be African-American and less likely to be Latino (Besinger et al., 1999). They also appear to be at particularly high risk for neglect (Besinger et al., 1999; Dunn et al., 2002; Ondersma, 2002), although some studies have reported that parental AOD use is a strong predictor of both abuse and neglect (Chaffin, et al., 1996). The out-of-home placements of AOD-affected children are more likely to be in relative foster care (Barth, 1991; Beeman, Kim, & Bullerdick, 2000; Benedict, Zuravin, & Stallings, 1996) and less likely to be in non-relative foster care (Besinger et al., 1999). Prior research also has demonstrated longer lengths of stay in foster care for AOD-affected children (Fanshel, 1975; Lewis, Giovannoni, & Leake, 1997; DHHS, 1999; Walker, Zangrillo, & Smith, 1991). For example, Lewis et al. (1997) found that two-thirds of AOD-affected children remained in care after two years as opposed to only one-third of non AOD-affected children.

A few studies have examined the relation of parental AOD use to the likelihood of being discharged to reunification and adoption. The research on the likelihood and timing of reunification generally has indicated that children of AOD-involved parents experience reduced likelihood of exiting from foster care to reunification (Murphy et al., 1991; Smith, 2003; Walker et al., 1991). The association of parental AOD use to the timing of reunification has not been a focus of research. Information about adoption likelihood and timing is less clear. Children of AOD-involved parents tend to be significantly younger than other children in foster care (Besinger et al., 1999), and research indicates that younger children are more likely to be adopted than older children (e.g., Connell, Katz, Saunders, & Tebes, 2006; Courtney & Wong, 1995). Barth and Needell (1994), however, report that the median age at placement in an adoptive home for drug-exposed infants was significantly older than for non drug-exposed infants, though this finding may have been due to sampling adopted infants rather than those waiting for adoption, or could reflect delayed permanency outcomes for AOD-affected children.

Although studies have examined characteristics of children whose parents abuse AOD, there are few empirical studies that have focused explicitly on children whose reason for removal is parental AOD use. This is true even though parental AOD use is a removal reason in about 10 - 30 percent of all removals (Beeman et al., 2000; Connell, Katz, et al., 2006). Currently, little is known about the specific influence of parental AOD use on children's foster care placement, length of stay in foster care, and permanency outcomes, such as reunification and adoption. Such information would inform the development of prevention and intervention services to meet the needs of these children and families.

The present study uses statewide administrative data to examine the characteristics, placement experiences, and discharge outcomes of children removed from parental custody and placed in foster care due to parental AOD use between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2002. First, demographic differences between AOD removals and the broader population of children placed in foster care for other reasons are described. Second, a comparison group of children in foster care for reasons other than parental AOD use (matched on child age, gender, and race/ethnicity) is used to examine univariate between group differences in child and case characteristics. Outcomes of interest include history of prior removals, presence of disability and mental health diagnosis, removal reasons beyond parental AOD use, initial foster placement setting, and length of stay in foster care. Finally, multivariate Cox proportional hazard modeling is used to examine the effect of removal due to parental AOD use on the timing of exiting foster care to either reunification or adoption, while statistically controlling for significant covariates identified in the extant literature. These covariates include: a history of prior removals (Connell, Katz et al., 2006), removal from the home due to physical and sexual abuse (Courtney & Wong, 1996; Harris & Courtney, 2003), removal due to child behavior problems (Wells & Guo, 1999), and the presence of a child disability or a mental health diagnosis (Courtney & Wong, 1996; Landsverk, Davis, Ganger, & Newton, 1996).

We hypothesize that children removed for parental AOD use will be more likely to experience co-occurring removal reasons of physical or sexual abuse and neglect in univariate analyses. These children also are expected to be placed in relative foster care settings more frequently, and are expected to remain in foster care for a longer period of time than the matched comparison sample. Finally, we expect that in multivariate analyses, removal due to parental AOD use will contribute to a lower likelihood of reunification and a higher likelihood of adoption, relative to removal for reasons other than parental AOD use.

Method

Site

This study is based on administrative data extracted from the Rhode Island Children's Information System (RICHIST), the management information system for the Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF). Rhode Island DCYF conducts Child Protective Service (CPS) investigations, makes disposition decisions, and arranges placements in a range of foster care services, including relative and non-relative foster homes, group home or residential placements, institutional settings such as psychiatric hospitals, and supervised apartment or independent living settings. Data on maltreatment incidence and foster care placements in Rhode Island are comparable to national rates (DHHS, 2006).

Data Elements, Coding, and Preparation

RICHIST data were obtained for all children that entered foster care between January 1, 1998 and December 31, 2002. By using data collected from 1998 and later, examination of the study questions was not confounded by the passing of the Adoption and Safe Families Act, or ASFA, in 1997. For children with multiple removals within this observation window, only the first removal episode was selected. Information on a number of child, parent, family, and case characteristics was collected by DCYF and entered into the RICHIST system. Child-level variables included age at admission, gender, and race/ethnicity. Two variables on child health status were also extracted from RICHIST data. Child disability is a composite variable reflecting the presence of mental retardation, physical disability, or visual/auditory impairment. The child mental health variable indicates whether the removed child had a diagnosed mental health condition. Child disability and mental health variables were recorded by caseworkers and are based on a combination of caseworker observations and record reviews, as well as parental report.

Case characteristics also were collected. Length of stay was calculated by subtracting the beginning date of placement from the end date of placement (or the end of the observation window in the case of children who remained in care). The number of prior removals from the home was collapsed into three categories (none, one prior removal, or two or more prior removals). RICHIST captures up to fifteen potential removal reasons contributing to an out-of-home placement. Caseworkers identify all applicable reasons for removal from the home (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect, child behavior, or parental AOD use) and then enter this data directly into RICHIST. They receive training in data entry to ensure compliance with state and federal requirements.

RICHIST includes a number of potential placement settings that were collapsed into four categories of relative foster homes, non-relative foster homes, group homes (e.g., group homes, supervised apartments, residential facilities), and emergency shelter placements. Finally, RICHIST captures one of nine potential reasons when a child is discharged from care. Two of these, parental reunification and adoption, were used for Cox proportional hazard analyses.

Sample

The initial RICHIST sample consisted of 5,909 children entering foster care during the observation window. Of these, 1,355 children, or about 23 percent of the total sample, were removed from the home due to parental AOD use. Twenty-two children in the AOD sample were dropped from analyses as a result of missing key demographic data (i.e., age, gender, or race/ethnicity). These exclusions resulted in a final sample of 1,333 children removed from the home for parental AOD use (AOD sample). Of the children removed for parental AOD use, 32 percent were removed solely for this reason, with no other reasons indicated. An additional 33 percent were removed for parental AOD use and one additional reason, 24 percent were removed for parental AOD use and two additional reasons, and 11% were removed for parental AOD use and three or more additional reasons. The remaining sample of 4,554 children was removed from the home for reasons other than parental AOD use.

In order to compare children in the AOD sample to children removed for other reasons, participants from the full sample of children removed for reasons other than parental AOD use (n=4,554) were selected based on their similarity in age, gender, and race to the AOD sample. The age (0-21 years; twenty-two categories), gender (two categories), and race/ethnicity (six categories) of children in the AOD sample was used to create a matrix in which each of 264 cells (22 × 2 × 6) contained the number of children matching various combinations for each of the three demographic categories. The same number of children matching the characteristics of each cell was then selected from the sample of children removed for other reasons. For example, if the AOD sample contained twelve eight-year old Caucasian girls, the same number of eight-year old Caucasian girls was randomly selected from the full sample of children removed for other reasons. The matching code allowed the age of the potential match to vary by plus or minus one year from the age of the AOD-removed child in cases were there were not enough non-AOD cases to match a given cell. Using this procedure, 1,333 children in the AOD sample were matched with 1,333 demographically similar children removed for other reasons (Non-AOD matched sample).

Data Analysis

T-tests and chi-square analyses were used to examine initial differences in age, gender, and race between the AOD sample (n=1,333) and the full sample of children removed for other reasons (n=4,554). Then, chi-square analyses were used to examine univariate differences between the AOD sample (n=1,333) and the Non-AOD matched sample (n=1,333) on prior removals, child disability and mental health status, co-occurring removal reasons (other than parental AOD use), and initial placement setting. Kaplan-Meier analysis then was used to examine the between groups difference in length of stay. Finally, two multivariate Cox proportional hazards models (Allison, 1995) were constructed to examine the contribution of being removed for parental AOD use to the timing of two discharge reasons following foster care entry – reunification and adoption – while controlling for the effects of other covariates known to be associated with these two outcomes (e.g., removals due to physical and sexual abuse, neglect, or child behavior problems; history of prior removals; presence of child disability or mental health problems). Cox proportional hazards modeling is useful for multivariate analysis of factors linked to increased or decreased timing of event occurrence, while taking into account right-censored cases (i.e., children who are not discharged to adoption or reunification, children not discharged prior to the end of the observation window). It is commonly used to analyze administrative data for samples of children in foster care (Connell, Katz, et al., 2006; Connell, Vanderploeg, et al., 2006; Mullins, Bard, & Ondersma, 2005; Smith, 2003). To account for bias in foster care research introduced by the high likelihood that siblings will experience similar placement outcomes (see Guo & Wells, 2003), a variance-corrected approach for Cox proportional hazards models was used to adjust the standard errors of the model parameters (Lin & Wei, 1989).

Results

Demographic Differences Between Children Removed for Parental AOD Use and the Remaining Sample of Children in Foster Care

The first set of analyses compared children in the AOD sample (n=1,333) with the remaining sample of children in foster care during the same timeframe (n=4,554). These analyses revealed significant demographic differences between groups (Table 1). Children in the AOD sample were significantly younger (M = 6.05, SD = 5.38) than children removed for other reasons (M = 10.44, SD = 5.95), t(5,880) = 24.22, p < .001. The AOD sample had a significantly greater proportion of girls (49.5% compared to 43.2%), χ2(1, N=5,882) = 16.53, p < .001. The overall chi-square for race/ethnicity was significant, χ2(5, N=5,791) = 40.68, p < .001. The AOD sample had a significantly greater proportion of African-American children (20.9% compared to 16.9%), χ2(1, N=5,791) = 11.16, p = .001, significantly fewer Hispanic children (13.6% compared to 16.8%), χ2(1, N=5,791) = 8.11, p < .01, and significantly fewer Asian/Pacific Islander children (0.3% compared to 2.3%), χ2(1, N=5,791) = 22.57, p < .001, than children removed for other reasons. These differences prompted the creation of the Non-AOD matched sample (n=1,333) described earlier. The utilization of this comparison sample allows for the examination of differences between the two matched groups in univariate and multivariate analyses, while controlling for differences associated with age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Table 1.

Comparisons of demographic and case characteristics among groups of children in foster care.

| Variable | AOD Sample (n=1,333) |

Non-AOD Sample (n=4,554) |

Non-AOD Matched Sample (n=1,333) |

Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at entry | X = 6.05, s.d. = 5.38 | X = 10.44, s.d. = 5.95 | X = 6.10, s.d. = 5.35 | a |

| 0–1 | 33.7% | 15.3% | 33.3% | a |

| 2–5 | 21.2 | 12.8 | 21.4 | a |

| 6–10 | 22.3 | 15.2 | 22.5 | a |

| 11–15 | 19.1 | 37.0 | 19.1 | a |

| 16–20 | 3.8 | 19.6 | 3.8 | a |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 49.5% | 43.2% | 49.5% | a |

| Male | 50.5 | 56.8 | 50.5 | a |

| Race | ||||

| White | 58.7% | 57.3% | 58.7% | |

| African-American | 20.9 | 16.9 | 21.5 | a |

| Hispanic | 13.6 | 16.8 | 13.6 | a |

| Native American | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.3 | 2.3 | 0.3 | a |

| Bi/Multi-Racial | 5.3 | 4.9 | 4.7 | |

| Missing | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.0 | |

| Length of Stay (median) | 13.6 months | 10.0 months | 10.9 months | a,b |

| Prior Removals | ||||

| None | 84.5% | 80.7% | 84.6% | |

| 1 prior | 10.4 | 10.5 | 9.2 | |

| 2 or more prior | 4.4 | 6.2 | 4.5 | a |

| Missing | 0.8 | 2.7 | 1.7 | |

| Child Health | ||||

| Child disability | 14.3% | 21.1% | 19.2% | a,b |

| Child DSM diagnosis | 5.9 | 12.0 | 9.5 | a,b |

| Removal Reason | ||||

| Abuse | 8.9% | 29.2% | 27.5% | a,b |

| Neglect | 48.7 | 44.2 | 55.6 | a,b |

| Child behavior problem | 5.0 | 34.5 | 17.8 | a,b |

| Placement Setting | ||||

| Relative foster care | 45.1% | 15.4% | 20.3% | a,b |

| Non-relative foster care | 43.4 | 33.2 | 52.4 | a,b |

| Group home | 2.0 | 21.7 | 10.8 | a,b |

| Emergency shelter | 9.5 | 29.7 | 16.4 | a,b |

AOD Sample and Non-AOD Sample significantly differ, p < .05;

AOD Sample and Non-AOD Matched Sample significantly differ, p < .05.

Analyses of Foster Care Placement Data for Children in the AOD Sample and the Non-AOD Matched Sample

Chi-square analyses were conducted to examine differences between AOD and Non-AOD matched samples on prior removals, child disability and mental health diagnosis status, removal reason, and initial placement setting. Percentages can be found in Table 1. Results for prior removals indicated a non-significant between groups difference. The AOD sample had a significantly smaller proportion of children with an identified disability, χ2(1, N=2,587) = 14.33, p < .001, and a significantly smaller proportion of children with an identified mental health diagnosis, χ2(1, N=2,606) = 13.21, p < .001. With regard to removal reason, the AOD sample had fewer children identified as removed for abuse, χ2(1, N=2,666) = 153.77, p < .001, neglect, χ2(1, N=2,666) = 12.72, p < .001, and child behavior problems, χ2(1, N=2,666) = 107.30, p < .001. Finally, a significant between groups difference was found with respect to initial placement setting, χ2(3, N=2,666) = 242.52, p < .001. The results were consistent with a study hypothesis, and indicated that children in the AOD sample were significantly more likely to be placed with relatives, χ2(1, N=2,666) = 185.59, p < .001, and were significantly less likely to be placed with non-relatives, χ2(1, N=2,666) = 21.64, p < .001, in group homes, χ2(1, N=2,666) = 87.48, p < .001, or in emergency shelters, χ2(1, N=2,666) = 28.11, p < .001.

Length of Stay in Foster Care for the Matched Comparison Samples

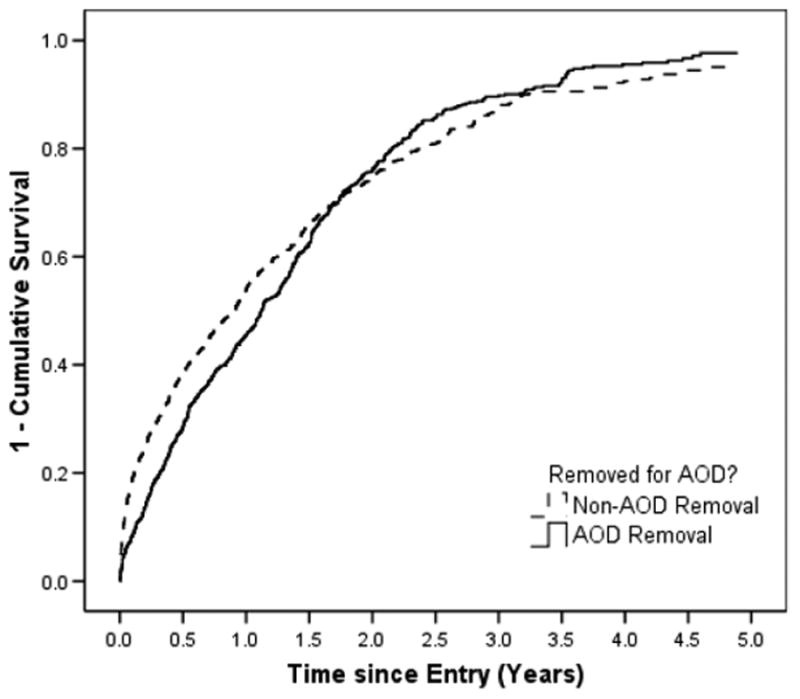

Kaplan-Meier analyses were conducted to examine differences between the matched comparison samples on length of stay in foster care. The results indicated a significant difference between the AOD sample (Median = 13.6 months) and Non-AOD matched sample (Median = 10.9 months) for length of stay in foster care, χ2(1, N=2,666) = 28.79, p < .001. This was consistent with one of the study hypotheses. As shown in Figure 1, the rates of exit for the two groups intersect at approximately 20 months, indicating that the difference in discharge rates between the two groups diminished over time. Post-hoc analyses were conducted to examine pairwise between groups comparisons for length of stay based on initial placement settings in relative and non-relative foster care. These analyses indicated that among children initially placed in relative foster care, the AOD sample (Median = 13.8 months) remained in care longer than the Non-AOD matched sample (Median = 11.4 months), χ2(1, N=636) = 5.50, p < .02. Similarly, among children initially placed in non-relative foster care, the AOD sample (Median = 14.4 months) remained in care longer than the Non-AOD matched sample (Median = 10.9 months), χ2(1, N=952) = 17.44, p < .001.

Figure 1.

Group comparison on length of stay in foster care.

Relationship of Removal Due to Parental AOD Use to Permanency Outcomes for the Matched Comparison Samples

Two multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were run to examine the influence of removal due to parental AOD use on the timing of being discharged to reunification (Model 1) and adoption (Model 2). These analyses controlled for child demographic and health characteristics, prior removals, other removal reasons, and initial placement setting. Cox models yield a risk ratio, which corresponds to the percentage change in the hazard rate for a given category of a variable, relative to the comparison category for that variable. Risk ratios significantly greater than one are indicative of increased risk associated with a given level of the covariate, and risk ratios significantly less than 1 are indicative of decreased risk associated with a given level.

Factors associated with reunification

The model for reunification is presented in Table 2. The overall chi-square predicting time to reunification was significant, χ2(21, N=2,584) =108.62, p< .0001. A number of significant child- and case-level factors emerged as significant predictors. Relative to infants, being older contributed to faster reunification (Risk Ratio2–5 years = 1.20, p<.05; Risk Ratio6–10 years = 1.26, p<.01; Risk Ratio11–15 years = 1.25, p<.05), with the exception of the non-significant finding for the 16-20 age group. Boys reunified faster relative to girls, Risk Ratioboys = 1.13, p<.05. Race/ethnicity and removal due to physical or sexual abuse, neglect, and child behavior problems were non-significant predictors of time to reunification. Initial placement in an emergency shelter was associated with faster reunification, Risk Ratioshelter = 1.46, p<.001. Two or more prior removals delayed reunification, Risk Ratio2 or more = 0.52, p<.05. Child disability, Risk Ratiodisability = 0.69, p<.0001, and child mental health diagnosis, Risk Ratiomental health diagnosis = 0.59, p<.0001, each significantly delayed reunification. Finally, after controlling for all other variables in the model, being removed for parental AOD use delayed time to reunification by about 12%, but this finding did not reach statistical significance (Risk RatioAOD removal = 0.88, p=.12). Consequently, the study hypothesis was only partially supported. However, in a model that did not utilize a variance-corrected approach to control for siblings in the dataset, this finding reached a trend level of significance (p<.10).

Table 2.

Cox regression model for discharge to reunification with a parent.

| Variable | B | Std. error | Risk Ratio | 95% CI | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Lower | |||||

| Age | |||||

| 0–1a | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2–5 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 1.20* | 1.02 | 1.41 |

| 6–10 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 1.26** | 1.06 | 1.50 |

| 11–15 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 1.25* | 1.03 | 1.52 |

| 16–20 | 0.05 | 0.19 | 1.05 | 0.72 | 1.54 |

| Gender | |||||

| Femalea | - | - | - | - | - |

| Male | 0.12 | 0.06 | 1.13* | 1.01 | 1.26 |

| Race | |||||

| Caucasiana | - | - | - | - | - |

| African-American | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.92 | 0.78 | 1.09 |

| Hispanic | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 1.19 |

| Native American | −0.29 | 0.34 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 1.45 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | −1.22 | 0.99 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 2.05 |

| Two or more Races | −0.15 | 0.17 | 0.86 | 0.61 | 1.21 |

| Prior Removals | |||||

| Nonea | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1 prior | 0.05 | 0.10 | 1.06 | 0.87 | 1.28 |

| 2 or more prior | −0.65 | 0.26 | 0.52* | 0.31 | 0.87 |

| Child Health | |||||

| Child disability | −0.38 | 0.09 | 0.69** | 0.57 | 0.82 |

| Child mental health | −0.52 | 0.13 | 0.59** | 0.46 | 0.77 |

| Removal Reason | |||||

| Abuseb | −0.04 | 0.10 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 1.16 |

| Neglectb | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 1.06 |

| Child behaviorb | −0.05 | 0.12 | 0.95 | 0.75 | 1.20 |

| Placement Setting | |||||

| Relative foster carea | - | - | - | - | - |

| Non-rel. foster care | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1.01 | 0.87 | 1.18 |

| Group home | −0.01 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 1.29 |

| Emergency shelter | 0.38 | 0.12 | 1.46** | 1.16 | 1.84 |

| AOD removal | |||||

| Non-AODa | - | - | - | - | - |

| AOD | −0.12 | 0.08 | 0.88 | 0.76 | 1.03 |

| Event/censored values: | |||||

| Event: 1,313 | |||||

| Censored: 1,271 | |||||

| Total: 2,584 | |||||

| % Censored: 49.2% | |||||

| Test of null hypothesis (all parameters=0) | |||||

| Without covariates | With covariates | Model Chi-square | df | p | |

| -2 log L | 18,771.9 | 18,663.3 | 108.6 | 21 | <.0001 |

p<.05;

p<.01.

Reference category for contrasts.

Reference category for abuse, neglect, and child behavior removal reasons is “not present.”

Factors associated with adoption

The model for adoption is presented in Table 3. The overall chi-square predicting discharge to adoption was significant, χ2(21, N=2,584) =229.76, p<.0001. A number of significant child- and case-level factors emerged as significant predictors of time to adoption. Relative to infants, being older significantly delayed time to adoption (Risk Ratio2–5 years = 0.62, p<.001; Risk Ratio6–10 years = 0.46, p<.001; Risk Ratio11–15 years = 0.08, p<.001). There were no 16–20 year olds in the risk set who were discharged from out-of-home care to adoption. Gender and race were not significantly related to the timing of discharge to adoption, although there were no Asian/Pacific Islander children discharged to adoption in this sample. Removals for abuse, neglect, and child behavior problems were not significantly related to time to adoption. Similarly, initial placement settings and prior history of removals were not significantly related to the timing of adoption. Child disability, Risk Ratiodisability = 0.67, p<.05, and child mental health diagnosis, Risk Ratiomental health diagnosis = 0.38, p<.01, each significantly delayed time to adoption. Finally, when controlling for all other variables in the model, being removed for parental AOD use was related to faster time to adoption, relative to being removed for other reasons, Risk RatioAOD Removal = 1.32, p<.05. This finding supported another study hypothesis.

Table 3.

Cox regression model for discharge to adoption.

| Variable | B | Std. error | Risk Ratio | 95% CI | Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Lower | |||||

| Age | |||||

| 0–1a | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2–5 | −0.47 | 0.14 | 0.62** | 0.48 | 0.81 |

| 6–10 | −0.79 | 0.18 | 0.46** | 0.32 | 0.65 |

| 11–15 | −2.54 | 0.39 | 0.08** | 0.04 | 0.17 |

| 16–20c | −13.72 | 0.35 | 0.00** | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Gender | |||||

| Femalea | - | - | - | - | - |

| Male | −0.001 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 1.22 |

| Race | |||||

| Caucasiana | - | - | - | - | - |

| African-American | −0.16 | 0.16 | 0.85 | 0.63 | 1.17 |

| Hispanic | −0.12 | 0.20 | 0.89 | 0.60 | 1.32 |

| Native American | −0.01 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 0.20 | 4.81 |

| Asian/Pacific Islanderc | −11.70 | 1.08 | 0.00** | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Two or more races | −0.14 | 0.24 | 0.87 | 0.54 | 1.40 |

| Prior Removals | |||||

| Nonea | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1 prior | 0.20 | 0.23 | 1.22 | 0.77 | 1.93 |

| 2 or more prior | 0.74 | 0.39 | 2.09+ | 0.97 | 4.51 |

| Child Health | |||||

| Child disability | −0.40 | 0.19 | 0.67* | 0.47 | 0.97 |

| Child mental health | −0.96 | 0.35 | 0.38** | 0.19 | 0.77 |

| Removal Reason | |||||

| Abuseb | 0.01 | 0.19 | 1.01 | 0.69 | 1.47 |

| Neglectb | 0.23 | 0.13 | 1.26+ | 0.97 | 1.63 |

| Child behaviorb | 0.24 | 0.33 | 1.27 | 0.67 | 2.43 |

| Placement Setting | |||||

| Relative foster carea | - | - | - | - | - |

| Non-rel. foster care | −0.06 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 0.72 | 1.24 |

| Group home | −0.79 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.18 | 1.19 |

| Emergency shelter | −0.44 | 0.29 | 0.65 | 0.37 | 1.15 |

| AOD removal | |||||

| Non-AODa | - | - | - | - | - |

| AOD | 0.28 | 0.14 | 1.32* | 1.01 | 1.72 |

| Event/censored values: | |||||

| Event: 391 | |||||

| Censored: 2,193 | |||||

| Total: 2,584 | |||||

| % Censored: 84.9% | |||||

| Test of null hypothesis (all parameters=0) | |||||

| Without covariates | With covariates | Model Chi-square | df | p | |

| -2 log L | 4,831.9 | 4,602.1 | 229.8 | 21 | <.0001 |

p<.10;

p<.05;

p<.01.

Reference category for contrasts.

Reference category for abuse, neglect, and child behavior removal reasons is “not present.”

Discussion

The present study used a matched comparison group design to examine the placement experiences of children removed due to parental alcohol or drug use, a group that comprised 23 percent of the total foster care sample. Children removed for parental AOD use differed from the broader child welfare population with regard to age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Comparisons to a demographically matched group revealed that children removed for parental AOD use were less likely to have an identified disability or mental health diagnosis, and were less likely to experience co-occurring removal reasons of neglect, abuse, and child behavior problems. In addition, children removed for parental AOD use experienced significantly longer lengths of stay in foster care, regardless of initial placement setting. Finally, two multivariate models examining the influence of AOD removal on discharge reasons revealed that after controlling for demographic characteristics, disability and mental health status, prior removals, other removal reasons, and initial placement setting, being removed for parental AOD use was not related to the timing of reunification with a parent after controlling for the inclusion of sibling relationships in the data. However, parental AOD removal was significantly related to faster time to adoption.

In the present study, the initial differences observed with regard to age and race/ethnicity between children removed due to parental AOD use and the remaining sample of children in foster care were consistent with findings from previous research with children of AOD-involved parents (Besinger et al., 1999; Conners et al., 2004; Dore & Doris, 1998). The present study extends these findings to children for whom parental AOD use is an identified reason for foster care placement. Unlike previous research, we also observed that girls were overrepresented among children removed for parental AOD use compared to children in the general foster care population. Based on these differences, a demographically matched comparison group was constructed from the administrative data. This procedure represents an additional contribution of the present study, in that we were able to control for differences on important demographic characteristics for subsequent analyses, thus strengthening the confidence in attributing group differences to the influence of being removed for parental AOD use. We believe this is a promising approach for future research examining samples of maltreated children and children in foster care.

The findings from comparisons of the matched groups revealed some interesting group differences. Contrary to one hypothesis, children removed for parental AOD use were less likely to be removed due to physical and sexual abuse, neglect, and child behavior problems. These findings are contrary to other studies reporting a higher risk for these types of maltreatment (Besinger et al., 1999; Chaffin et al., 1996; DHHS, 1999; Dunn et al., 2002; Ondersma, 2002). However, it is important to note that the present study examined removal reasons, rather than maltreatment experiences directly. Although the two are undoubtedly linked, caseworkers need only identify one reason for removal in a given case, although they are asked to identify all applicable reasons. In this study, one-third of the AOD sample was indicated as removed due only to parental AOD use. Given that only one reason for removal is required for removal, it is possible that in the presence of severe parental AOD abuse, caseworkers are less likely also to indicate abuse, neglect, or child behavior problems. Therefore, it is possible that examining removal reasons as a grouping indicator could lead to an underestimate of the rates of abuse and neglect that actually occur in the presence of AOD use.

Consistent with prior research on children of AOD-involved parents, children removed due to parental AOD use were more likely initially to be placed in relative foster care (Barth, 1991; Beeman et al., 2000; Benedict et al., 1996), and less likely to be placed in non-relative foster care (Besinger et al., 1999). It is possible that the members of the family support networks of AOD-involved parents have grown accustomed to caring for the children of their AOD-involved family member when their ability to parent effectively is adversely affected by their substance use. This could make the decision by CPS to place a child with a relative an available and more convenient option. It is also possible that caseworkers are concerned about the permanency timelines that took effect with ASFA. When children are placed in relative foster care settings, ASFA timelines for permanency hearings and pursuit of termination of parental rights may be bypassed. This option might be pursued more frequently in cases of parental AOD use, where there also may be concerns about substance abuse treatment timeframes and potential for relapse (Mullins et al., 2004; SAMHSA, 2005).

In addition, children removed for parental AOD use experienced longer lengths of stay in foster care, consistent with other studies (Fanshel, 1975; Lewis et al., 1997; DHHS, 1999; Walker et al., 1991). Based on prior research linking relative foster care to longer lengths of stay (Courtney, 1994; Goerge, 1990), post-hoc comparisons confirmed that the AOD sample experienced longer lengths of stay among those initially placed in relative and non-relative foster care settings. This suggests a unique influence of being removed due to parental AOD use that transcends the influence of initial placement setting alone. Again, it is possible that AOD-affected children are placed in relative foster care intentionally so that the permanency timelines established by ASFA can be bypassed, allowing more time for AOD-affected parents to seek treatment and pursue reunification. To our knowledge, prior studies have not reported that samples of AOD-affected children or children removed for parental AOD use who are initially placed in non-relative foster care remain in care longer than children removed for other reasons. This finding supports the view that parental AOD use complicates permanency planning and extends length of stay in foster care for AOD-removed children, regardless of initial placement setting.

Children in foster care for parental AOD use were reunified at comparable rates to children in care for reasons other than parental AOD use; however, their rates for adoption were higher. The non-significant findings linking parental AOD removal to reunification are counter to studies that have examined samples of children of AOD-involved parents (Murphy et al., 1991; Smith, 2003; Walker et al., 1991). However, when using a less conservative statistical approach that does not control for siblings in the dataset, the findings demonstrated that AOD removal is related to delayed exits to reunification at the trend level. To our knowledge, this finding has not been reported in the literature. It is possible that parents whose children are removed for their drug use are difficult to engage and retain in substance abuse treatment, and often do not make adequate treatment progress to justify reunification, or that caseworkers and judges are hesitant to reunify until sustained sobriety can be demonstrated. If this were true, it would increase the likelihood and speed with which adoption is pursued.

A closer examination of the survival curves suggests that the lag experienced by children removed for parental AOD use disappears by about 20 months. These findings likely reflect the influence of increased rates of adoption for AOD removed children that begin to take place more frequently 12 to 18 months following removal (Connell, Katz, et al. 2006; Courtney & Wong, 1996). We have speculated that this period of increased adoption rates may be a result of caseworker decisions to pursue adoption after other permanency goals had been pursued, in addition to the amount of time required to legally free a child for adoption. The present findings are consistent with prior studies, and suggest that over time, adoption becomes an increasingly likely option for caseworkers, particularly as reunification is slightly delayed. For AOD-using parents who wish to avoid termination of parental rights and instead be reunified with their children, specialized substance abuse treatment that takes child welfare concerns into account might be in particular need.

Limitations

This study was based on administrative data, which often lacks the detail that would be helpful in uncovering additional factors that make AOD-removed children and their families different from children removed for other reasons. In the present study, important factors that previously have been related to placement outcomes, such as poverty, substance abuse treatment compliance, and parenting attitudes and behaviors (Courtney & Wong, 1996; Fuller & Wells, 1999; Smith, 2003) were not available. In particular, it would have been useful to match the comparison group with the additional criteria of income/SES, although this information was not available in the current study. It is possible that parents with more economic resources who become involved with CPS have access to legal and treatment options that other parents do not, thereby leading to differential outcomes such as higher rates of reunification and lower rates of termination of parental rights and adoption. Although researchers have acknowledged the limitations of administrative data, such data continues to be a useful means to observe patterns in placement experiences using very large samples (Drake & Jonson-Reid, 1999). By identifying other factors related to AOD removal, the present study provides a basis for further integration of work in this area.

This study also was limited by the fact that nearly two-thirds of children removed for parental AOD use experienced at least one additional removal reason. The presence of children with co-occurring removal reasons in addition to parental AOD use makes it more difficult to attribute group differences solely to being removed for parental AOD use. In addition, it is unknown whether parents in the Non-AOD removal group had substance use issues, although their children were ultimately removed for other reasons. However, the present study provides strong empirical support for a variety of factors associated with removal due to parental AOD use, controlling for the child's age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

Implications for Prevention and Intervention

We see a number of potential implications from these findings with respect to the development of appropriate prevention and intervention strategies. First, this study found that 23 percent of children removed from their homes between 1998 and 2002 experienced an out-of-home placement, due at least in part, to parental AOD use. This population constitutes a substantial portion of all foster care removals, and suggests that this group of children requires more research attention. Second, the present findings suggest that children removed for parental AOD use would benefit from specialized services. Prevention programs could target the particular risk of co-occurring neglect and removal due to parental AOD use. For example, at the time of an allegation of parental substance use, screening a family for neglect could identify those families and children who are particularly at-risk for negative outcomes, such as frequent maltreatment incidents, and the accompanying developmental risk posed by the combination of parental substance use and neglectful parenting. Third, in this study, children removed for parental AOD use were much more likely to be placed in relative foster care. Services could be targeted to provide support to the family members who are more likely to assume responsibility for a child's care following removal due to parental AOD use. For example, teams with special expertise in the areas of parental substance abuse, neglect, and working with relative caregivers could be trained to provide specialized services to this group of children and families. Finally, given the decreased likelihood for reunification and the increased likelihood for these children to be adopted, additional programs that emphasize child welfare concerns in conjunction with substance abuse treatment needs might be essential for parents who wish to be reunified with their children.

In summary, this study contributes to the literature on the children of AOD-involved parents, and to our knowledge, is one of the few studies to examine children placed in foster care as a direct result of parental AOD use. The use of a demographically matched comparison group provides a strong methodological framework for making conclusions about the influence of such placement reasons on children's foster care experiences. An increased understanding of the characteristics and placement experiences of this subgroup of children is essential for the development of empirically-based prevention and intervention programs to improve safety and permanency outcomes, and ultimately, child well-being, for children of parents who abuse alcohol and other drugs.

Footnotes

The authors wish to thank members of the Division of Prevention and Community Research, Yale University School of Medicine for helpful comments and suggestions.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey J. Vanderploeg, Yale University School of Medicine; New Haven, CT.

Christian M. Connell, Yale University School of Medicine; New Haven, CT

Colleen Caron, Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth, and Families; Providence RI

Leon Saunders, Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth, and Families; Providence RI

Karol H. Katz, Yale University School of Medicine; New Haven, CT

Jacob Kraemer Tebes, Yale University School of Medicine; New Haven, CT

References

- Allison PD. Survival analysis using the SAS system: A practical guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP. Adoption of drug-exposed children. Children and Youth Services Review. 1991;13:323–342. [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Needell B. Outcomes for drug-exposed children four years post-adoption. Children & Youth Services Review. 1994;18:37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Beeman SK, Kim H, Bullerdick SK. Factors affecting placement of children in kinship and nonkinship foster care. Children and Youth Services Review. 2000;22:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict MI, Zuravin S, Stallings RY. Adult functioning of children who lived in kin versus nonrelative family foster homes. Child Welfare. 1996;75:529–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besinger B, Garland A, Litrownik A, Landsverk J. Caregiver substance abuse among maltreated children placed in out-of-home care. Child Welfare. 1999;78:221–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Kelleher K, Hollenberg J. Onset of physical abuse and neglect: Psychiatric, substance abuse, and social risk factors from prospective community data. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20:191–203. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(95)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. Parental drug use as child abuse: Summary of state laws. 2006 Retrieved November 15, 2006, from http://www.childwelfare.gov/systemwide/laws_policies/statutes/drugexposedall.pdf.

- Connell CM, Katz KH, Saunders L, Tebes JK. Leaving foster care: The influence of child and case characteristics on foster care exit rates. Children & Youth Services Review. 2006;28:780–798. [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Bergeron N, Katz KH, Saunders L, Tebes JK. Re-referral to Child Protective Services: The influence of child, family, and case characteristics on risk status. Child Abuse & Neglect. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.004. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Vanderploeg JJ, Flaspohler P, Katz KH, Saunders L, Tebes JK. Placement transitions among children in foster care: A longitudinal study of child and case influences. Social Service Review. 2006;80:398–418. doi: 10.1086/505554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners NA, Bradley RH, Mansell L, Liu JY, Roberts TJ, Burgdorf K, et al. Children of mothers with serious substance abuse problems: An accumulation of risks. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2004;30:85–100. doi: 10.1081/ada-120029867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME. Factors associated with the reunification of foster children with their families. Social Service Review. 1994;68:81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ME, Wong YI. Comparing the timing of exits from substitute care. Children and Youth Services Review. 1996;18:307–334. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. Blending perspectives and building common ground. Washington, DC: Author; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health Human Services, Administration for Children Families. The AFCARS report. 2006 Retrieved November 13, 2006 from the World Wide Web: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/stats_research/afcars/tar/report13.htm.

- Dore MM, Doris JM. Preventing child placement in substance-abusing families: Research-informed practice. Child Welfare. 1998;77:407–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore M, Doris JM, Wright P. Identifying substance abuse in maltreating families: A child welfare challenge. Child Abuse and Neglect. 1995;19:531–543. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Jonson-Reid M. Some thoughts on the increasing use of administrative data in child maltreatment research. Child Maltreatment. 1999;4:308–315. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn MG, Tarter RE, Mezzich AC, Vanyukov M, Kirisci L, Kirillova G. Origins and consequences of child neglect in substance abuse families. Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22:1063–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(02)00132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Marshall DB, Brummel S, Orme M. Characteristics of repeated referrals to child protective services in Washington State. Child Maltreatment. 1999;4:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Fanshel D. Parental failure and consequences for children: The drug-abusing mother whose children are in foster care. American Journal of Public Health. 1975;65:604–612. doi: 10.2105/ajph.65.6.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame L, Berrick JD, Brodowski ML. Understanding re-entry to out-of-home care for reunified infants. Child Welfare. 2000;79:339–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller TL, Wells SJ. Predicting maltreatment recurrence among CPS cases with alcohol and other drug involvement. Children and Youth Services Review. 2003;25:553–569. [Google Scholar]

- Goerge RM. The reunification process in substitute care. Social Service Review. 1990;64:422–457. [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Wells K. Research on timing of foster care outcomes: One methodological problem and approaches to its solution. Social Service Review. 2003;77:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Harris MS, Courtney ME. The interaction of race, ethnicity, and family structure with respect to the timing of family reunification. Children and Youth Services Review. 2003;25(5-6):409–429. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JL, Leff M. Children of substance abusers: Overview of research findings. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1085–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher K, Chaffin M, Hollenberg J, Fischer E. Alcohol and drug disorders among physically abusive and neglectful parents in a community-based sample. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1586–1590. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.10.1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ. Parenting stress and child maltreatment in drug-exposed children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16:317–328. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90042-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsverk J, Davis I, Ganger W, Newton R. Impact of child psychosocial functioning on reunification from out-of-home placement. Children and Youth Services Review. 1996;18(4-5):447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Giovannoni JM, Leake B. Two-year placement outcomes of children removed at birth from drug-using and non drug-using mothers in Los Angeles. Social Work Research. 1997;21:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Wei L. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1989;84:1074–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Miller KA, Fisher PA, Fetrow B, Jordan K. Trouble on the journey home: Reunification failures in foster care. Children & Youth Services Review. 2006;28:260–274. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins SM, Bard DE, Ondersma SJ. Comprehensive services for mothers of drug-exposed infants: Relations between program participation and subsequent child protective services reports. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10:72–81. doi: 10.1177/1077559504272101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J, Jellnick M, Quinn D, Smith G, Poitrast FG, Goshko M. Substance abuse and serious child mistreatment: Prevalence, risk, and outcome in a court sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1991;15:197–211. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90065-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair P, Schuler ME, Black MM, Kettinger L, Harrington D. Cumulative environmental risk in substance abusing women: Early intervention, parenting stress, child abuse potential and child development. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:997–1017. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(03)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondersma SJ. Predictors of neglect within low-SES families: The importance of substance abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:383–391. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. How parental drug use and drug treatment compliance relate to family reunification. Child Welfare. 2003;82:335–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Overview of Findings from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: 2005. Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-27, DHHS Publication No. SMA 05-4061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terling T. The efficacy of family reunification practices: Reentry rates and correlates of reentry for abused and neglected children reunited with their families. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:1359–1370. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez ML, Jansson LM, Montoya ID, Schweitzer W, Golden A, Svikis D. Parenting knowledge among substance abusing women in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C, Zangrillo P, Smith JM. Parental drug abuse and African American children in foster care. Washington, DC: National Black Child Development Institute; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wells K, Guo S. Reunification and reentry of foster children. Children and Youth Services Review. 1999;21:273–294. [Google Scholar]

- Wolock I, Magura S. Parental substance abuse as a predictor of child maltreatment re-reports. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1996;20:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolock I, Sherman P, Feldman LH, Metzger B. Child abuse and neglect referral patterns: A longitudinal study. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23:21–47. [Google Scholar]