Abstract

Adolescence is a period of enhanced sensitivity to social influences and vulnerability to drug abuse. Social reward in adolescent rats has been demonstrated with the conditioned place preference (CPP) model, but it is not clear whether limited contact with another rat without play is sufficient to produce reward. We investigated this issue using an apparatus containing two main compartments each with a wire mesh barrier that allowed rats placed on either side of the barrier to have limited physical contact. Adolescent male rats were given two conditioning sessions/day for 2 or 8 days following baseline preference tests. Rats were placed into their preferred side alone for one daily 10-min session and into their initially non-preferred side (i.e., CS) for the other session during which they either had restricted or unrestricted physical access to another rat (Rat/Mesh or Rat/Phys, respectively) or to a tennis ball (Ball/Mesh or Ball/Phys, respectively) unconditioned stimulus (US). Only the Rat/Phys group exhibited CPP after 2 CS-US pairings; however, after 8 CS-US pairings, the Rat/Mesh and Ball/Phys groups also exhibited CPP. During conditioning, the rat US elicited more robust approach and contact behavior compared to the ball, regardless of physical or restricted access. The incidence of contact and/or approach increased as the number of exposures increased. The results suggest that the rank order of US reward efficacy was physical contact with a rat > limited contact with a rat > physical contact with a ball, and that rough-and-tumble play is not necessary to establish social reward-CPP. The findings have important implications for emerging drug self-administration models in which two rats self-administering drug intravenously have limited physical contact via a mesh barrier shared between their respective operant conditioning chambers.

Keywords: rough-and-tumble play behavior, place conditioning, adolescence, drug self-administration

1. Introduction

Social interaction is a hallmark feature of normal development during adolescence that enables appropriate social behavior in adulthood [1-6]. Play behaviors in particular are thought to be important for the transition into normal sexual behaviors [7, 8] and the establishment of dominance hierarchies among adult rodents [9, 10]. Social interaction is a substantial natural reward for rodents. For instance, rats will learn to traverse a T-maze to gain access to another rat [11-13]. In addition, conditioned place preference (CPP) studies reveal that rats will display robust approach towards, and spend more time in, an environment paired with access to another rat [14-18] and a single re-exposure to a social partner in the associated environment will reinstate an extinguished preference for that environment [19]. We have observed synergistic interactions between social and drug rewards using the CPP paradigm [18, 20] and such interactions may be involved in the vulnerability of adolescents to initiate drug use during this developmental period [21-36].

Specific aspects underlying the rewarding effects of social encounters in rodents remain unclear. It has been suggested that the primary rewarding feature of a social context is the ability to engage in rough-and-tumble play behavior (i.e. play fighting) [17, 37, 38]. For instance, social reinforcement is reduced when full physical contact is restricted or when the play drive of a social partner is pharmacologically inhibited with amphetamine, chlorpromazine, scopolamine or methylphenidate [11, 14, 19]. In addition, rats will display conditioned place preference (CPP) for an environment associated with a playful rat partner over one associated with a scopolamine-induced non-playful rat, suggesting that relative reward strength of social encounters are graded in nature [14]. Even though scopolamine disrupts play behavior, other social behaviors persist in the non-altered playmate despite the partner’s lack of response, such as dorsal contacts, social sniffing and crawl-overs [39, 40], but the degree to which these behaviors are rewarding is not known.

The necessity of play behavior for establishing social reward-CPP is unclear and under some circumstances play behavior is insufficient for establishing CPP. For example, adolescent social reward is observed in socially experienced rats that receive play pairings with other socially experienced rats, but not when the play pairings occur with a previously isolated partner [17]. Socially experienced rats engage in play behaviors with both types of partners, but will avoid the socially deprived partner if given the opportunity [41]. Furthermore, we have shown that there is no relationship between the magnitude of social reward-CPP and the amount of play behavior that occurs during conditioning [18]. Also, under conditions in which nicotine or cocaine reduce play behavior, these drugs also enhance social reward-CPP [18, 20].

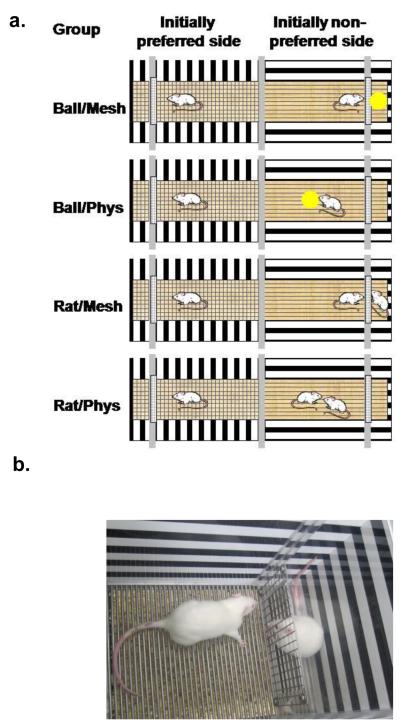

This study directly tested the hypothesis that play behavior in adolescent rats is not necessary for social reward. We used a modified CPP apparatus that allowed for a rat to be placed behind a mesh screen (see Figure 1), which created opportunities for social encounters with limited physical contact but without rough-and-tumble play behavior. We included controls to examine physical and restricted contact to an inanimate play object (i.e., a tennis ball).

Figure 1.

Conditioning procedure (a) and apparatus (b). Two conditioning sessions took place daily for 10 min each separated by a 6-h interval. Baseline preference was determined and roughly half of the rats preferred the horizontal-striped side and half preferred the vertical-striped side. One session took place in the initially preferred side of the apparatus, during which the rat was alone. The other session took place in the initially nonpreferred side, during which the rat received exposure to the US. US conditions included either limited contact through the mesh barrier or full physical contact with either a tennis ball (Ball/Mesh and Ball/Phys, respectively) or a rat (Rat/Mesh or Rat/Phys, respectively). The photograph illustrates one side of the conditioning apparatus with a rat behind the mesh barrier.

2. Methods

2.1 Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, San Diego, CA) arrived at Arizona State University on postnatal day (PND) 22 (i.e., 22 days old). To avoid prolonged isolation and foster healthy play development, rats were pair-housed upon arrival until PND 26, at which point they were single-housed thereafter. Rats were housed in a climate-controlled facility with a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 7 PM) with ad libitum access to food and water. Housing and care were conducted in accordance with the 1996 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Rats [42]. All experiments were conducted within a conservative estimate of rodent adolescence - PNDs 28-42 [5] - given that social reward peaks during this developmental period [17]. Prior to baseline testing, animals were acclimated to handling for 5-12 days (see Figure 2 for specific timeline of each experiment). On each of these days, rats were handled for at least 2 min/day. Once the rats were single-housed they remained isolated except when paired together during conditioning.

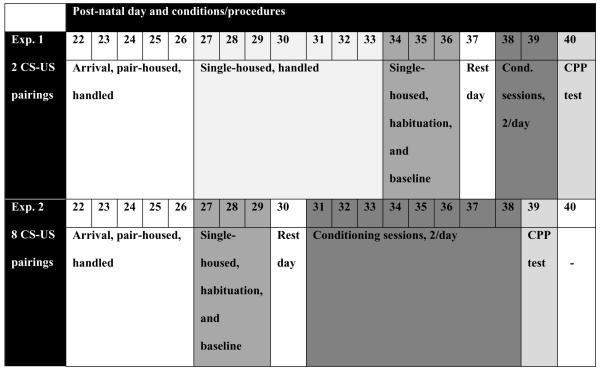

Figure 2.

Timeline of the procedures across post-natal days (PNDs) for Experiments 1 and 2.

2.2 Apparatus

Conditioning took place in rectangular Plexiglas chambers (Figure 1). Each chamber contained a removable partition that separated the chamber into two equal-sized compartments, each measuring 35 × 24 × 31 cm high. One compartment had corn cob bedding beneath a wire 1 × 1 cm grid floor and alternating black and white vertical stripes on the walls. The other compartment had pine-scented bedding beneath a parallel bar floor (5 mm diameter) and alternating black and white horizontal stripes on the walls. The stripes on the walls of both compartments were 2 cm wide. Additional end compartments were created by inserting a divider that split the original compartment into a main compartment (27 × 24 × 31 cm high) and a small end compartment (8 × 24 × 31 cm high), such that during conditioning a conspecific or a ball could be placed in the end compartment as an unconditioned stimulus (US) (see Figure 1). The divider was made of clear Plexiglas except for 1 × 1 cm wire grid mesh (16.5 × 8 cm) on the bottom portion of the dividing wall. On the pre- and post-conditioning test days, the removable center partition of the apparatus was replaced by a similar partition that contained an opening in the center (28 × 6 cm), allowing the rats free-access to the bordering compartments simultaneously. To prevent the rats from escaping from the chamber while maintaining the ability to record their behavior via an overhanging video camera, a rectangular tower measuring 70 × 24 × 74 cm high of clear Plexiglas was used as an extension of the apparatus. Unpublished data from our laboratory established that the main compartments on either side of the center were equally preferred across adolescent and adult rats (i.e., the apparatus was unbiased). The conditioning room was dimly lit with two overhead lamps, each containing a 25 watt light bulb.

A camera (Panasonic WV-CP284, color CCTV, Suzhou, China) used to record testing sessions was mounted 101 cm above the center of the apparatus. A WinTV 350 personal video recorder (Hauppage, NJ, USA) captured live video and encoded it to MPEG streams. A modified version of TopScan Software (Clever Sys., Inc. Reston, VA, USA) used the orientation of an animal’s body parts (e.g. nose, head, center of body, forepaws, base of tail, etc.) to identify behaviors that are specified by the user and recognized by the program. The software employed the whole position of the body to estimate other body parts (e.g. nose, forepaw, head etc.) when they were not in view in order to yield measures of time spent in each compartment.

2.3 Baseline preference

On the first day of the procedure for both experiments, rats were transported to the conditioning room and were placed into the CPP apparatus where they had free access to both main compartments for 10 min to habituate them to the novel environment. The mesh dividers restricting access to the small end compartments were in place throughout the entire experiment. Initial baseline preference was assessed across the next 2 consecutive days by again allowing each rat free-access to the main compartments for 10 min each day. The starting compartment was counterbalanced across days and entry into a compartment was operationally defined as a rat’s forepaws entering a compartment as determined by the software. Time spent in each compartment was averaged across the two baseline days to determine each rat’s initial side preference. Rats that failed to demonstrate at least five compartment crossovers during either baseline test day were excluded from the experiments due to inadequate environmental exploration; however, they were assigned as a physical play partner for experimental rats when initial preferences and body weights did not allow for pairing experimental rats together.

2.4 Conditioning and testing

Rats were assigned to one of four groups (n =9-10/group) that received the following US exposure upon placement into their initially non-preferred side (i.e., conditioned stimulus, CS): 1) physical access to another rat in the same compartment with nothing behind the mesh (Rat/Phys); 2) restricted access to another rat behind the mesh divider (Rat/Mesh); 3) physical access to a tennis ball in the same compartment with nothing behind the mesh (Ball/Phys); or 4) restricted access to a tennis ball behind the mesh divider (Ball/Mesh). During separate sessions, all rats were placed alone in their initially preferred side without anything behind the mesh. Rats in the ‘Ball’ conditions (i.e., Ball/Phys and Ball/Mesh) were exposed to their own brand new tennis ball and that ball remained constant throughout conditioning to control for relative novelty. Rats in the Rat/Phys group were assigned to pairs that were matched for initial compartment preference and body weight within 10 g. All rat partners were unfamiliar with each other prior to conditioning, but remained constant throughout conditioning.

Conditioning sessions were conducted twice per day at the same time of day with each rat confined to one side of the CPP apparatus for 10 min during the morning session, and confined to the opposite side of the apparatus for 10 min during the afternoon session. At least 6 h intervened between morning and afternoon sessions. Previous research from our laboratory demonstrated that social reward-CPP is established regardless of whether a biased or unbiased design is used [18]. Therefore, we chose a biased CPP design [i.e., pairing the US with the initially non-preferred side of the apparatus (CS)] because this design allows for a greater range of preference change as well as observation of a preference switch (i.e., >50% time spent in initially non-preferred side on test day) indicative of a reward effect rather than a reduction of initial aversion to the CS. The starting side for the first conditioning session was counterbalanced such that half of the rats in each group were exposed first to their initially non-preferred side containing their respective US, and the other half were exposed to their initially preferred side with no stimulus (i.e., alone). Rats then received the opposite of these conditions during the afternoon session. Two separate experiments were conducted, with Experiment 1 employing two CS-US pairings and Experiment 2 employing eight CS-US pairings, both followed by a final test for CPP. The specific timeline for each experiment is summarized in Figure 2.

Crossovers during baseline and preference tests were counted from previously recorded video files by an observer blind to experimental conditions. As mentioned previously, a crossover was defined as entry of a rat’s forepaws into one of the two compartments. During the first and last US-paired conditioning sessions, frequency and duration of contact with a partner rat or a tennis ball were scored for rats in the Rat/Phys and Ball/Phys groups and contacts with the mesh screen were scored for rats in the Rat/Mesh and Ball/Mesh groups using Observer 5.0 software (Noldus Information Technology BV, Wageningen, The Netherlands). This program allows for a frame by frame analysis of behavior. Contact was operationally defined as any part of the body with the exception of the tail touching either the object (i.e., ball or rat) or the mesh screen. Since contacts between rat partners were not independent, contact data from the Rat/Phys group was scored and analyzed per pair. Thus for Experiment 1, the ‘Phys’ object contact behavioral analyses included n=6 pairs for the Rat/Phys group and n=10 for the Ball/Phys group. For Experiment 2, two rats from the Rat/Phys group and two rats from the Ball/Phys group were removed from the object contact behavioral analysis due to loss of video footage of either the first or last day resulting in n=4 pairs for the Rat/Phys group and n=7 for Ball/Phys group.

2.5 Data Analysis

CPP was operationally defined as a significant increase in time spent in the initially non-preferred side (i.e., US-paired side) on the post-conditioning test relative to the average of the pre-conditioning tests (i.e., baseline). Time spent in the initially non-preferred side from both experiments was analyzed using a mixed factor ANOVA with Day (baseline vs. test day) as a repeated measures factor and Object (ball vs. rat), Contact (mesh vs. physical) and number of pairings (2 vs. 8) as between subjects factors. In addition, we transformed the data to difference scores of time in the initially non-preferred side on the test day minus the baseline and analyzed the difference scores using ANOVA with Object, Contact and Number of pairings as between subjects factors. Significant interactions were further analyzed using smaller ANOVAs, tests of simple effects and/or paired-sample t-tests with a Bonferroni correction where appropriate [43].

Crossovers were analyzed using mixed factors ANOVAs with Day (baseline vs. test day) as a repeated measures factor and Object and Contact as between subjects factors. The number of physical contacts (i.e., Rat/Phys contacts with partner rat and Ball/Phys contacts with tennis ball), duration of contacts and duration per contact were all analyzed for each experiment using separate mixed factors ANOVAs with Day (first conditioning day vs. last conditioning day) as a repeated measures factors and Physical Object as a between subjects factor. The number of mesh screen contacts, duration of contact with the mesh screen, and the duration per contact were all analyzed using mixed factors ANOVAs with Day (first conditioning day vs. last conditioning day) as a repeated measures factor and Object behind the mesh as a between subjects factor. Significant interactions were further analyzed using tests of simple effects.

3. Results

All significant effects are reported.

3.1 Conditioned place preference

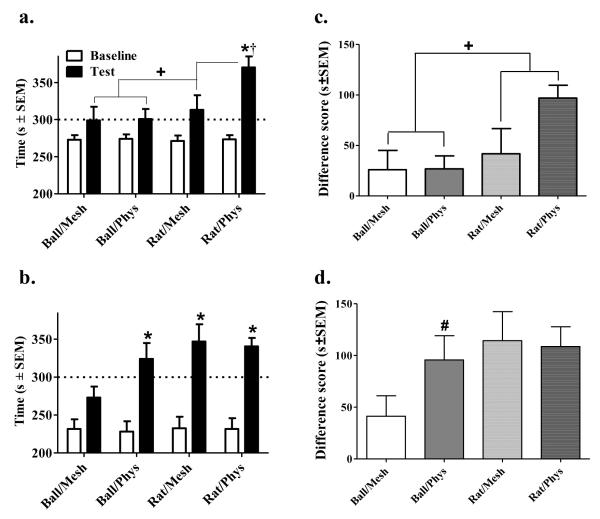

The CPP results of both experiments are shown in Figure 3. The ANOVA of time spent in the initially non-preferred side revealed main effects of Day (F(1,70)=89.44, p<0.001), Object (F(1,70)=9.56, p<0.01) and Number of pairings (F(1,70)=8.51, p<0.01) as well as Day × Object (F(1,70)=8.68, p<0.01), Day × Number of pairings (F(1,70)=8.35, p<0.01), Contact × Object × Number of pairings (F(1,70)=3.79, p=0.05), and Day × Object × Contact × Number of pairings interactions (F(1,70)=3.85, p=0.05). We analyzed the source of the 4-way interaction by conducting separate ANOVAs of the CPP data from each experiment. For Experiment 1 involving 2 CS-US pairings, the ANOVA of time spent in the initially non-preferred side revealed main effects of both Day (F(1,36)=27.83, p<0.001) and Object (F(1,36)=5.29, p<0.05) as well as an Object × Day interaction (F(1,36)=5.60, p<0.05). The significant Object × Day interaction was further analyzed using tests of simple effects of Object with the data collapsed across Contact conditions. These tests revealed that although there was no significant difference between baseline measures, rats spent significantly more time in the initially non-preferred side on test day when rat was the US object relative to when ball was the object, t(38)=2.38, p<0.05. These findings suggest that only a rat and not a ball shifted preference when 2 CS-US pairings were given during conditioning. In addition to the ANOVA, we conducted Bonferroni t-tests comparing baseline to test for each group setting alpha at p<0.0125 for significance. These t-tests revealed that only the Rat/Phys group (t(9)=7.68, p<0.001) spent more time in the initially non-preferred side on test day relative to baseline, whereas there were no significant differences between test and baseline for any other group.

Figure 3.

Object- (i.e., rat or ball) and Contact- (i.e., physical or mesh) dependent CPP after 2 or 8 CS-US pairings (a and b, respectively) expressed as the mean number of seconds ± SEM in the stimulus-paired side pre-conditioning (i.e., Baseline, white bars) vs. post-conditioning (i.e., Test, black bars). The dotted line represents 50% of the total test time (i.e., 300 seconds). Although all groups given 2 CS-US pairings exhibited an increase in time spent on the US-paired side on test day relative to baseline (main effect of day, p<0.01), the increase was greater when the object was a rat, and greatest in the Rat/Phys group. The only group that failed to display CPP with 8 CS-US pairings was the Ball/Mesh group. Preference data is also represented as difference scores of time spent in the US-paired side on test – baseline days (mean s ± SEM) after either 2 or 8 CS-US pairings (c and d, respectively) for the ball object (i.e., solid bars) or rat object (i.e., striped bars) with either physical contact (i.e., gray bars) or the object behind a mesh screen (i.e., white bars). Plus sign (+) indicates a main effect of Object, p<0.05; Dagger (†) indicates difference from all other groups, p<0.05; Asterisk (*) indicates an increase in the amount of time spent in the stimulus-paired side on Test day relative to Baseline, Bonferroni t-test, p<0.0125; Pound sign (#) indicates a difference from respective group given 2 CS-US pairings, test of simple effects, p<0.05.

For Experiment 2 involving 8 CS-US pairings, the ANOVA of time spent in the initially non-preferred side revealed main effects of both Object (F(1,34)=4.42, p<0.05) and Day (F(1,34)=61.07, p<0.001), but no interactions. Thus, when the data were collapsed across the contact variable, rats conditioned with a social partner demonstrated greater preference shifts than rats conditioned with a ball. In addition, all rats in general demonstrated preference shifts toward their initially non-preferred compartment following eight days of conditioning. However, it is important to note that only the Ball/Phys, Rat/Mesh, and Rat/Phys groups exhibited a preference switch indicative of reward (i.e., >50% of the total test time in their initially non-preferred side during the post-conditioning test), whereas the Ball/Mesh control group still spent < 50% of the test time in their initially non-preferred side, which may reflect reduction of initial aversion rather than conditioned reward (see Figure 3B). The strong main effect of Day may have obscured the detection of potential group differences. Therefore, paired-sample t-tests with Bonferroni correction (i.e., alpha set at p< 0.0125 for significance) were conducted and revealed significant increases in the time spent in the initially non-preferred side on the test day relative to baseline in the Rat/Mesh group (t(9)=4.07, p<.01), the Rat/Phys group (t(9)=5.70, p<0.001) and the Ball/Phys group (t(8)=4.10, p<0.01), but not the Ball/Mesh group.

An independent samples t-test revealed a significant difference between baseline values for Experiment 1 and 2, (t(51.70)=5.7, p<0.001), and therefore, we conducted additional analyses on differences scores calculated as time spent in the initially nonpreferred side during the test minus baseline (Figure 3C and D). The ANOVA of difference scores revealed significant main effects of Object (F(1,70)=8.68, p<0.01) and Number of pairings (F(1,70)=8.35, p<0.01), as well as an Object × Contact × Number of pairings interaction (F(1,70)=3.85, p=0.05). To further probe this interaction, separate ANOVAs were conducted for each experiment. For Experiment 1 involving 2 CS-US pairings, the ANOVA of difference scores revealed a significant main effect of Object (F(1,36)=5.60, p<0.05) where rats conditioned with another rat spent more time on the US-paired side compared to rats conditioned with a ball, regardless of type of contact. Furthermore, planned comparisons of difference scores between experiments of respective groups conditioned with 2 versus 8 pairings revealed a significant difference in the Ball/Phys group only (t(17)=2.66, p<0.05). Collectively, these findings indicate that the difference scores significantly increased after 8 pairings when rats received physical contact with a ball.

3.2 Crossovers on test day

Crossovers from one side of the chamber to the other on baseline and test days are shown in Table 1. The ANOVA of crossovers revealed a within subjects main effect of Day for both Experiment 1 (F(1,34)=104.55, p<0.001) and 2 (F(1,36)=83.04, p<0.001), where all groups displayed significantly more crossovers on test day compared to baseline. Independent samples t-tests with Bonferroni correction (i.e., alpha set at p< 0.025 for significance) revealed significantly more baseline crossovers with 2 pairings compared to 8 (t(72)=5.3, p<0.001), but no difference in the number of crossovers on test day.

Table 1.

Behaviors measured during baseline, conditioning and test days

| Ball | Rat | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh | Physical | Mesh | Physical | ||

| Crossovers | |||||

| 2 pairings | Baseline | 30.0 ± 2.0 | 24.6 ± 1.9 | 30.0 ± 3.2 | 25.6 ± 1.4 |

| Test | 45.2 ± 4.4* | 41.2 ± 5.5* | 53.9 ± 3.9* | 47.1 ± 5.9* | |

| 8 pairings | Baseline | 17.8 ± 1.4† | 19.7 ± 2.2† | 22.1 ± 2.0† | 17.6 ± 2.6† |

| Test | 42.9 ± 7.0* | 47.0 ± 4.9* | 40.2 ± 4.5* | 41.3 ± 1.7* | |

| Number of physical contacts | |||||

| 2 pairings | Day 1 | — | 46.8 ± 4.5 | — | 59.8 ± 6.9 |

| Day 2 | — | 47.3 ± 2.8 | — | 54.0 ± 8.7 | |

| 8 pairings | Day 1 | — | 45.9 ± 4.5 | — | 53.3 ± 6.2 |

| Day 8 | — | 44.7 ± 6.7 | — | 37.4 ± 3.5 | |

| Time in physical contact | |||||

| 2 pairings | Day 1 | — | 81.9 ± 9.2 | — | 464.5 ± 9.2+ |

| Day 2 | — | 113.8 ± 17.7 | — | 479.3 ± 15.5+ | |

| 8 pairings | Day 1 | — | 61.5 ± 10.3 | — | 452.3 ± 13.8+ |

| Day 8 | — | 97.2 ± 23.2* | — | 562.3 ± 11.9*+ | |

| Time in contact with mesh | |||||

| 2 pairings | Day 1 | 124.0 ± 15.6 | — | 243.4 ± 21.3+ | — |

| Day 2 | 102.5 ± 14.0 | — | 254.8 ± 20.0+ | — | |

| 8 pairings | Day 1 | 97.7 ± 10.8 | — | 285.4 ± 18.6+ | — |

| Day 8 | 184.1 ± 14.5* | — | 333.6 ± 14.2*+ | — | |

| Time/contact with mesh | |||||

| 2 pairings | Day 1 | 6.4 ± 0.6 | — | 6.4 ± 0.7 | — |

| Day 2 | 5.9 ± 0.5 | — | 6.8 ± 0.5 | — | |

| 8 pairings | Day 1 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | — | 8.4 ± 0.7 | — |

| Day 8 | 6.4 ± 0.6* | — | 5.8 ± 0.8* | — | |

Asterisk indicates a main effect of Day;

Plus sign indicates a main effect of Object;

Dagger indicates difference from 2 pairings, Bonferroni t-test, p<0.025.

3.3 Behavior during conditioning sessions

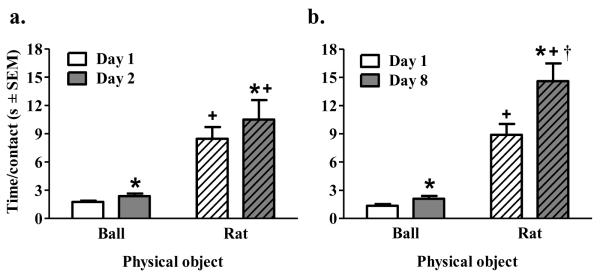

For physical contact with a ball or a rat, number of contacts and time spent in contact with object are shown in Table 1 and time per contact is shown in Figure 4. The ANOVA for number of physical contacts revealed no significant effects for either experiment. However, time spent in contact yielded a significant main effect of Object in both Experiment 1 (F(1,14)=703.46, p<0.001) and 2 (F(1,9)=551.63, p<0.001), and a significant main effect of Day in Experiment 2 (F(1,9)=8.02, p<0.05) indicating that more time was spent in contact with the object when the object was a rat compared to a ball, and that regardless of object, contact time increased from day 1 to day 8. The ANOVA of time per contact for Experiment 1 revealed main effects of Day (F(1,14)=7.06, p<0.05) and Object (F(1,14)=36.88, p<0.001) indicating that time per contact increased from day one to day two and time per contact on both days was significantly higher when the physical object was a rat compared to a ball. The ANOVA of time per contact for Experiment 2 revealed significant main effects of Day (F(1,9)=24.79, p<0.001) and Object (F(1,9)=104.79, p<0.001) as well as a significant Day × Object interaction (F(1,9)=14.78, p<0.01). Tests of simple effects revealed that duration per contact with a rat increased from day 1 to day 8 (t(3)=3.53, p<0.05), but not for a ball, and was significantly higher on both day 1 (t(3.14)=6.50, p<0.01) and day 8 (t(3.16)=6.58, p<0.01) compared time per contact with a ball.

Figure 4.

Time per contact for rats that received physical contact with a ball (Ball/Phys; solid bars) or a rat (Rat/Phys; striped bars) shown for the first (i.e., white bars) and last (i.e., gray bars) day of conditioning in Experiment 1 (a) and 2 (b). Asterisk (*) indicates a main effect of day where day 2 or day 8 is greater than day 1, p<0.05. Plus sign (+) indicates a main effect of Object where a rat is greater than a ball, p<0.001. Dagger (†) represents a greater increase from Day 1 to Day 8 relative to that of the Ball condition, tests of simple effects, p<0.05.

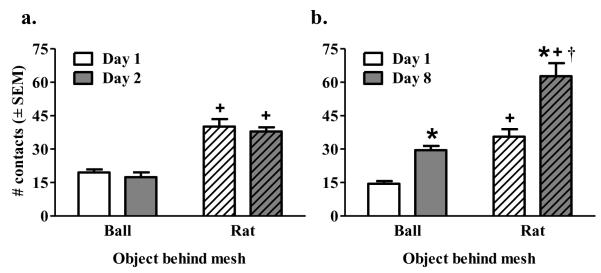

For contact with the mesh screen in front of either a ball or a rat, number of contacts are shown in Figure 5 and time spent in contact and time per contact are shown in Table 1. For Experiment 1, the ANOVA of number of contacts with the mesh screen revealed a significant effect of Object (F(1,18)=414.74, p<0.001) indicating that regardless of day, rats contacted the mesh screen significantly more when a rat was the object behind the mesh compared to a ball. For Experiment 2, the ANOVA of number of mesh contacts revealed a significant main effect of Day (F(1,17)=96.70, p<0.001) and Object (F(1,17)=31.62, p<0.001) as well as an Object × Day interaction (F(1,17)=7.80, p<0.05). Tests of simple effects revealed that number of mesh contacts increased from day 1 to day 8 for both the rat (t(9)=7.58, p<0.001) and the ball behind the mesh screen (t(8)=7.03, p<0.001) and was significantly higher on both day 1 (t(17)=5.73, p<0.001) and day 8 (t(17)=5.10, p<0.001) when the object behind the mesh was a rat compared to a ball. The interaction indicates that the increase in number of mesh contacts from day 1 to day 8 was greater in the Rat/Mesh group relative to the Ball/Mesh group. The ANOVAs for time in contact with the mesh revealed a significant main effect of Object for both Experiment 1 (F(1,18)=38.23, p<0.001) and Experiment 2 (F(1,17)=94.67, p<0.001) indicating that rats spent more time contacting the mesh when the object behind it was another rat compared to a ball. A main effect of Day was also found in Experiment 2 (F(1,17)=29.94, p<0.001) indicating that the number of contacts increased on day 8 compared to day 1. The ANOVAs of time per contact yielded a significant effect of Day (F(1,17)= 7.54, p<0.05) for Experiment 2 indicating that time per contact with the mesh screen decreases by day 8 compared to day 1. No significant effects were found for time per contact with mesh for Experiment 1.

Figure 5.

Number of contact with the mesh screen in front of a tennis ball (Ball/Mesh; solid bars) or rat (Rat/Mesh striped bars) on the first (i.e., white bars) and last (i.e., gray bars) day of conditioning in Experiment 1 (a) and 2 (b). Asterisk (*) indicates a main effect of day where day 8 is greater than day 1, p<0.001. Plus sign (+) indicates a main effect of object where a rat is greater than a ball, p<0.001. Dagger (†) represents a greater increase from Day 1 to Day 8 relative to that of the Ball condition, tests of simple effects, p<0.05.

4. Discussion

The results indicate that social reward-CPP can be obtained in adolescent male rats even when physical contact is limited and rough-and-tumble play is prevented. These findings provide conclusive evidence that rough-and-tumble play behavior is not necessary for a social encounter between adolescent male rats to be rewarding, and also provide evidence that full physical contact enhances the rewarding effects produced by a conspecific. We conclude that the unconditioned stimuli used in this study differ in reward magnitude with the following rank order from most to least rewarding: Rat/Phys > Rat/Mesh > Ball/Phys > Ball/Mesh.

Reward magnitude is in part inferred by the degree of preference shift; however, because there is often a ceiling effect where similar CPP is observed with stimuli that vary in reward magnitude [44], the number of pairings needed to establish CPP is another measure indicative of reward magnitude. The more highly rewarding a US, the more rapidly CPP is established [45]. In the present study, the physical presence of another rat was the only US strong enough to produce CPP after 2 CS-US pairings in Experiment 1, suggesting that it was the most rewarding US. There was also a significant Object x Day interaction in Experiment 1 in which the time spent in the US-paired side increased more relative to baseline when a rat was the US object than when a ball was the US object regardless of contact condition (physical vs. mesh), suggesting that in general the rat US is more rewarding than the ball US. After 8 CS-US pairings in Experiment 2, similar CPP was observed among the Rat/Phys, Rat/Mesh, and Ball/Phys groups yet the Ball/Mesh group still failed to exhibit CPP. Collectively, these findings suggest that encountering another rat even if it is behind a mesh is more rewarding than the physical presence of a non-social play object, and that physical contact is needed to observe reward with the non-social play object and only after 8 pairings. This point is further bolstered by the Ball/Phys group displaying a significantly lower difference score with 2 pairings compared to 8. In contrast, the Rat/Phys group remained consistently high from 2 to 8 pairings, the Ball/Mesh group remained consistently low, and there was no significant change in the Rat/Mesh group’s difference scores from 2 to 8 pairings likely because their scores were already somewhat elevated after 2 pairings. The difference between the Rat/Phys and Ball/Phys groups further suggests that social reward-CPP cannot be explained by the presence of another object within the conditioning environment.

Previous research has shown that isolated adolescent rats are highly sensitive to novel object-CPP [46], but because the ball was most novel initially when CPP was not observed in the Ball/Phys group, we do not think that the CPP observed in this group after eight pairings was a result of novelty. Furthermore, novelty-CPP is typically established with repeated access to different novel objects in one of two distinct environments or a choice between a familiar or novel environment [47-50]. We speculate when the US is an inanimate object, the rats may need to have full physical contact with it to find the experience rewarding in contrast to when the US is another rat.

Approach behaviors measured during the conditioning sessions further support differences in the reward value of a conspecific compared to an inanimate play object. In groups that had physical contact during conditioning, time per physical contact increased from day 1 to either day 2 or day 8, and after 8 sessions, the time per contact was greater for a rat than a ball (Figure 4). In the groups that did not have full physical contact with the play object, the most sensitive measure of approach behavior was the number of mesh contacts. With 2 CS-US pairings, there were more contacts with the mesh when rat was the object than when ball was the object regardless of day. With 8 CS-US pairings, again there were more mesh contacts when rat was the object and there were more mesh contacts on day 8 than on day 1, with the Rat/Mesh group exhibiting the highest rate of mesh contacts on day 8 (Fig. 5). The findings that these approach behaviors increase rather than decrease with repeated exposures is likely because rats habituate to other environmental cues but not to the object itself. The finding that approach measures were the highest after 8 pairings with a rat US is likely because the rat is more rewarding than the ball, perhaps due to reciprocation of interaction by the partner rat but not by the ball.

Our findings expand upon previous research that has examined the contribution of play to rewarding effects of a social encounter. For instance, Humphreys and Einon (1981) demonstrated that a rat will choose a conspecific that is able to engage in play over a restricted or unmotivated play partner in a T-maze. Our results are consistent with their study and extend the findings to the CPP model. In this model, a relationship between the amount of play behavior during conditioning and the magnitude of social reward-CPP has been found but may not be reliable [17, 18]. Calcagnetti and Schecter (1992) have shown that rats fail to exhibit CPP if they are paired with a partner whose play drive is pharmacologically inactivated. Similarly, our findings suggest that in rats that are motivated to play, a rat that is restricted from playing provides a less rewarding stimulus than one that is able to play. Importantly, our results further suggest that a restricted rat (i.e., Rat/Mesh) is nonetheless rewarding, and therefore play is not necessary for social reward-CPP.

The present results are consistent with previous research suggesting that rodents find other elements of social encounters to be rewarding besides rough-and-tumble play. These other elements are influenced by social deprivation and the ability to engage in play. For instance, rats that have a choice between an opening in an apparatus facing another rat versus one that does not face another rat will spend more time investigating the social opening rather than non-social opening, which does not habituate over multiple trials [51]. Similarly, we found that rats contact the mesh screen separating them from another rat more frequently than if it were separating them from a ball and contacts with screen in front of a rat US increase by the 8th trial, suggesting that approach behavior or investigation of a conspecific increases over time and persists beyond the novelty stage. In addition, shifts to social behaviors unrelated to play (i.e., crawling over, grooming and sniffing the social partner) are observed when motivation to play is decreased by social experience such as group housing [41] or through pharmacological inactivation of play behaviors [39, 40]. Furthermore, periods of isolation in adolescence elevate social motivation [19, 37, 38, 41, 52, 53]. Thus, it is possible that social motivation in the present study was high due to isolation housing during conditioning, thereby allowing for non-play social encounters to substitute for social reward typically derived from play behavior.

Barriers restricting physical access to a stimulus are frequently used to examine motivation for social investigation as well as social recognition in rodents. In fact, rodents will inherently prefer a novel conspecific compared to a novel object in initial testing [54-56], similar to our day 1 of conditioning where mesh screen contacts are higher with an initially unfamiliar partner behind the screen than with a novel ball. Mesh screens have also been used in experiments examining the effects of differential housing conditions on play behavior. Results from these studies suggest that rats living in duplex housing (i.e., separated by a mesh screen) demonstrate a ‘play rebound’ similar to fully isolated rats [37, 57, 58]. This effect of play deprivation is attenuated when housing conditions allow for bodily contact, but not vigorous attributes of play behavior (i.e., chasing and pinning), indicating that the “need” for play can be attenuated with more mild forms of social contact [37].

A potential concern in the present study is that animals that were given 2 pairings had less of a preference for their initially preferred side, and therefore higher baseline values of time spent in the initially non-preferred side, than animals given 8 pairings. Higher initial baseline values decrease sensitivity for detecting a significant increase in time spent in the US-paired side post-conditioning and this may have contributed to the lack of CPP in the Ball/Phys and Rat/Mesh groups given only 2 pairings. One mitigating argument against this concern is that neither of these groups exhibited as much time spent in the US-paired side post-conditioning after 2 pairings as they did after 8 pairings, suggesting that the lack of effect with 2 pairings was not simply due to a higher baseline. Nonetheless, preference data were also analyzed after transformation to difference scores of test-baseline to minimize variability across cohorts. The variation in baselines across experiments likely reflects age differences between the cohorts of rats since those in Experiment 1 were tested for baseline preference on PND 35-36, whereas those in Experiment 2 were tested on PND 28-29.

Age differences between cohorts may have also contributed to locomotor activity differences. Locomotor activity as measured by compartment crossovers during baseline testing was significantly lower for Experiment 2 compared to Experiment 1, probably because rats in Experiment 2 received baseline testing at an earlier PND than those in Experiment 1. Younger rats may have been more anxious during baseline testing, but we doubt that anxiety played a role during the test day because all groups displayed significantly more crossovers on test day compared to baseline and test day crossovers were not different between experiments.

Our lab is particularly interested in the reward strength of a rat behind a mesh screen because we aim to investigate the influence of this type of social context on acquisition of drug-self administration in adolescent rats. For the latter paradigm, it is necessary to keep the rats separate (i.e., behind a mesh barrier) so that they do not disrupt each other’s drug infusion lines. Given that many adolescents initiate drug use in a social setting, it is important to integrate this factor into animal drug abuse paradigms to more closely model social contributions to drug reward and reinforcement in humans. It has long been known that alcohol consumption in humans is more pleasurable when it takes place in a social context than when alone [59, 60]. Similarly in rats, oral ethanol intake is facilitated by social interaction [61, 62] and social context can influence sensitivity to alcohol and attenuate its aversive effects [63, 64]. We have observed a synergistic interaction between social reward and either cocaine or nicotine reward [18, 20] yet little is known about the influence of social context on intravenous drug self-administration. The results from the present study suggest that limited exposure of two rats separated by a mesh barrier is rewarding and should provide a valid model for examining effects of social interaction on acquisition, maintenance and extinction of intravenous drug self-administration.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that rough-and-tumble play is not necessary to establish social reward-CPP in adolescent male rats. Specifically, limited physical contact with another rat is rewarding but to a lesser degree than full physical contact with another rat. In addition, rats elicit more robust approach and contact behavior than an inanimate object during conditioning. The present results suggest that a mesh barrier between adolescent rats will be useful for examining social influences on other aspects of behavior, such as intravenous drug self-administration.

Highlights.

CPP was established in adolescent rats using pairings of a conspecific or a ball

These stimuli were available in the compartment or behind a mesh barrier

Only physical access to a partner produced CPP after 2 pairings

Partner behind mesh and physical access to ball produced CPP after 8 pairings

A conspecific behind a mesh barrier is rewarding in the absence of play

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Emile Saad for his assistance with preliminary work on this project, Heather Koch and Jose Alba for their data collection contributions, and Matthew Adams for his assistance with software setup. The project described was supported by grants DA0011064, F32DA025413, R21DA023123 and F31DA02746 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. This research was also supported in part by funds from the More Graduate Education at Mountain States Alliance at Arizona State University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute through the Undergraduate Science Education Program and from the Arizona State University School of Life Sciences.

Abbreviations

- CPP

Conditioned place preference

- CS

Conditioned stimulus

- US

Unconditioned stimulus

- Rat/Phys

Physical access to another rat

- Rat/Mesh

Restricted access to another rat behind a mesh barrier

- Ball/Phys

Unrestricted access to a ball

- Ball/Mesh

Restricted access to a ball behind a mesh barrier

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Einon DF, Morgan MJ, Kibbler CC. Brief periods of socialization and later behavior in the rat. Dev Psychobiol. 1978;11:213–25. doi: 10.1002/dev.420110305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Panksepp J. The ontogeny of play in rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1981;14:327–32. doi: 10.1002/dev.420140405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Meaney MJ, Stewart J. Environmental factors influencing the affiliative behavior of male and female rats (Rattus norvegicus) Anim Learn Behav. 1979;7:397–405. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Smith PK. Does play matter? Functional and evolutionary aspects of animal and human play. Behav Brain Sci. 1982;5:139–84. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neurosci Biobehav R. 2000;24:417–63. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].van den Berg CL, Hol T, Van Ree JM, Spruijt BM, Everts H, Koolhaas JM. Play is indispensable for an adequate development of coping with social challenges in the rat. Dev Psychobiol. 1999;34:129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Meaney MJ, Stewart J, Beatty WW. Sex differences in social play, the socialization of sex roles. Adv Study Behav. 1985;15 [Google Scholar]

- [8].Moore CL. Development of mammalian sexual behavior. In: Collin ES, editor. The Comparative Development of Adaptive Skills: Evolutionary Implications. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, N.J.: 1985. pp. 19–55. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pellis SM, Pellis VC. Role reversal changes during the ontogeny of play fighting in male rats: attack vs. defense. Aggress Behav. 1991;17:179–89. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pellis SM, Pellis VC, Kolb B. Neonatal testosterone augmentation increases juvenile play fighting but does not influence the adult dominant relationships of male rats. Aggress Behav. 1992;18:437–47. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Humphreys AP, Einon DF. Play as a Reinforcer for Maze-Learning in Juvenile Rats. Anim Behav. 1981;29:259–70. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Normansell L, Panksepp J. Effects of Morphine and Naloxone on Play-Rewarded Spatial Discrimination in Juvenile Rats. Developmental Psychobiology. 1990;23:75–83. doi: 10.1002/dev.420230108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Werner CM, Anderson DF. Opportunity for Interaction as Reinforcement in a T-Maze. Pers Soc Psychol B. 1976;2:166–9. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Calcagnetti DJ, Schechter MD. Place Conditioning Reveals the Rewarding Aspect of Social-Interaction in Juvenile Rats. Physiol Behav. 1992;51:667–72. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Crowder WF, Hutto CW. Operant Place Conditioning Measures Examined Using 2 Nondrug Reinforcers. Pharmacol Biochem Be. 1992;41:817–24. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Van den Berg CL, Pijlman FT, Koning HA, Diergaarde L, Van Ree JM, Spruijt BM. Isolation changes the incentive value of sucrose and social behaviour in juvenile and adult rats. Behav Brain Res. 1999;106:133–42. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Douglas LA, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Rewarding properties of social interactions in adolescent and adult male and female rats: impact of social versus isolate housing of subjects and partners. Dev Psychobiol. 2004;45:153–62. doi: 10.1002/dev.20025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Thiel KJ, Okun AC, Neisewander JL. Social reward-conditioned place preference: a model revealing an interaction between cocaine and social context rewards in rats. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:202–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Trezza V, Damsteegt R, Vanderschuren LJ. Conditioned place preference induced by social play behavior: parametrics, extinction, reinstatement and disruption by methylphenidate. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19:659–69. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Thiel KJ, Sanabria F, Neisewander JL. Synergistic interaction between nicotine and social rewards in adolescent male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;204:391–402. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].O’Dell LE. A psychobiological framework of the substrates that mediate nicotine use during adolescence. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):263–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Torres OV, Tejeda HA, Natividad LA, O’Dell LE. Enhanced vulnerability to the rewarding effects of nicotine during the adolescent period of development. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:658–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].O’Dell LE, Torres OV, Natividad LA, Tejeda HA. Adolescent nicotine exposure produces less affective measures of withdrawal relative to adult nicotine exposure in male rats. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2007;29:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].O’Dell LE, Bruijnzeel AW, Smith RT, Parsons LH, Merves ML, Goldberger BA, et al. Diminished nicotine withdrawal in adolescent rats: implications for vulnerability to addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:612–9. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cao J, Belluzzi JD, Loughlin SE, Dao JM, Chen Y, Leslie FM. Locomotor and stress responses to nicotine differ in adolescent and adult rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;96:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dwyer JB, McQuown SC, Leslie FM. The dynamic effects of nicotine on the developing brain. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;122:125–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cao J, Lotfipour S, Loughlin SE, Leslie FM. Adolescent maturation of cocaine-sensitive neural mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:2279–89. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jamner LD, Whalen CK, Loughlin SE, Mermelstein R, Audrain-McGovern J, Krishnan-Sarin S, et al. Tobacco use across the formative years: a road map to developmental vulnerabilities. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(Suppl 1):S71–87. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001625573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Belluzzi JD, Lee AG, Oliff HS, Leslie FM. Age-dependent effects of nicotine on locomotor activity and conditioned place preference in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:389–95. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1758-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Leslie FM, Loughlin SE, Wang R, Perez L, Lotfipour S, Belluzzia JD. Adolescent development of forebrain stimulant responsiveness: insights from animal studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:148–59. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dwyer JB, Broide RS, Leslie FM. Nicotine and brain development. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2008;84:30–44. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kameda SR, Fukushiro DF, Trombin TF, Procopio-Souza R, Patti CL, Hollais AW, et al. Adolescent mice are more vulnerable than adults to single injection-induced behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Olds RS, Thombs DL. The relationship of adolescent perceptions of peer norms and parent involvement to cigarette and alcohol use. J Sch Health. 2001;71:223–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ. Cognitive and social influence factors in adolescent smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1984;9:383–90. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(84)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sussman S. Risk factors for and prevention of tobacco use. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44:614–9. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Barron S, White A, Swartzwelder HS, Bell RL, Rodd ZA, Slawecki CJ, et al. Adolescent vulnerabilities to chronic alcohol or nicotine exposure: findings from rodent models. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1720–5. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000179220.79356.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Panksepp J, Siviy S, Normansell L. The psychobiology of play: theoretical and methodological perspectives. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1984;8:465–92. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(84)90005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Panksepp J, Beatty WW. Social deprivation and play in rats. Behav Neural Biol. 1980;30:197–206. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(80)91077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Deak T, Panksepp J. Play behavior in rats pretreated with scopolamine: increased play solicitation by the non-injected partner. Physiol Behav. 2006;87:120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pellis SM, McKenna M. What do rats find rewarding in play fighting?--an analysis using drug-induced non-playful partners. Behav Brain Res. 1995;68:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(94)00161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP, Spear NE. Social behavior and social motivation in adolescent rats: role of housing conditions and partner’s activity. Physiol Behav. 1999;67:475–82. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Clark JD, Gebhart GF, Gonder JC, Keeling ME, Kohn DF. Special Report: The 1996 Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. ILAR J. 1997;38:41–8. doi: 10.1093/ilar.38.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Keppel G. Design and Analysis: A Researcher’s Handbook. 3rd ed Prentice-Hall Inc.; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bevins RA. The reference-dose place conditioning procedure yields a graded dose-effect function. Int J Comp Psychol. 2005;18:101–11. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Bardo MT, Rowlett JK, Harris MJ. Conditioned place preference using opiate and stimulant drugs: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1995;19:39–51. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)00021-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Douglas LA, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Novel-object place conditioning in adolescent and adult male and female rats: effects of social isolation. Physiol Behav. 2003;80:317–25. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bardo MT, Neisewander JL, Pierce RC. Novelty-Induced Place Preference Behavior in Rats - Effects of Opiate and Dopaminergic Drugs. Pharmacol Biochem Be. 1989;32:683–9. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bevins RA, Besheer J, Palmatier MI, Jensen HC, Pickett KS, Eurek S. Novel-object place conditioning: behavioral and dopaminergic processes in expression of novelty reward. Behavioural Brain Research. 2002;129:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00326-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Bevins RA, Bardo MT. Conditioned increase in place preference by access to novel objects: antagonism by MK-801. Behavioural Brain Research. 1999;99:53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wright RL, Conrad CD. Chronic stress leaves novelty-seeking behavior intact while impairing spatial recognition memory in the Y-maze. Stress. 2005;8:151–4. doi: 10.1080/10253890500156663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Deak T, Arakawa H, Bekkedal MY, Panksepp J. Validation of a novel social investigation task that may dissociate social motivation from exploratory activity. Behav Brain Res. 2009;199:326–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Social interactions in adolescent and adult Sprague-Dawley rats: impact of social deprivation and test context familiarity. Behav Brain Res. 2008;188:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ikemoto S, Panksepp J. The effects of early social isolation on the motivation for social play in juvenile rats. Dev Psychobiol. 1992;25:261–74. doi: 10.1002/dev.420250404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Perez A, Barbaro RP, Johns JM, Magnuson TR, et al. Sociability and preference for social novelty in five inbred strains: an approach to assess autistic-like behavior in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:287–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-1848.2004.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Moy SS, Nadler JJ, Young NB, Perez A, Holloway LP, Barbaro RP, et al. Mouse behavioral tasks relevant to autism: phenotypes of 10 inbred strains. Behav Brain Res. 2007;176:4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nadler JJ, Moy SS, Dold G, Trang D, Simmons N, Perez A, et al. Automated apparatus for quantitation of social approach behaviors in mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2004;3:303–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hole G. The Effects of Social Deprivation on Levels of Social Play in the Laboratory Rat Rattus-Norvegicus. Behav Process. 1991;25:41–53. doi: 10.1016/0376-6357(91)90044-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Holloway KS, Suter RB. Play deprivation without social isolation: housing controls. Dev Psychobiol. 2004;44:58–67. doi: 10.1002/dev.10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Pliner P, Cappell H. Modification of Affective Consequences of Alcohol - Comparison of Social and Solitary Drinking. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1974;83:418–25. doi: 10.1037/h0036884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Smith RC, Parker ES, Noble EP. Alcohol and Affect in Dyadic Social-Interaction. Psychosom Med. 1975;37:25–40. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Tomie A, Burger KM, Di Poce J, Pohorecky LA. Social opportunity and ethanol drinking in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28:1089–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Tomie A, Uveges JM, Burger KM, Patterson-Buckendahl P, Pohorecky LA. Effects of ethanol sipper and social opportunity on ethanol drinking in rats. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:197–202. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Gauvin DV, Briscoe RJ, Goulden KL, Holloway FA. Aversive attributes of ethanol can be attenuated by dyadic social interaction in the rat. Alcohol. 1994;11:247–51. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP, Spear NE. Acute effects of ethanol on behavior of adolescent rats: role of social context. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:377–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]