Abstract

In colon cancer, mutation of the Wnt repressor Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) leads to a state of aberrant and unrestricted “high-activity” signaling. However, relevance of high Wnt tone in non-genetic human disease is unknown. Here we demonstrate that distinct Wnt activity functional states determine oligodendrocyte precursor (OPC) differentiation and myelination. Murine OPCs with genetic Wnt dysregulation (high tone) express multiple genes in common with colon cancer including Lef1, SP5, Ets2, Rnf43 and Dusp4. Surprisingly, we find that OPCs in lesions of hypoxic human neonatal white matter injury upregulate markers of high Wnt activity and lack expression of APC. Finally, we show lack of Wnt repressor tone promotes permanent white matter injury after mild hypoxic insult. These findings suggest a state of pathological high-activity Wnt signaling in human disease tissues that lack pre-disposing genetic mutation.

Introduction

Activation of canonical Wnt signaling results in the stabilization of β-catenin and its translocation to the nucleus to associate with TCF family transcriptional protein partners. In the intestine, low activity signaling mediated by TCF4-β-catenin is necessary for normal turnover of the epithelium throughout life and maintenance of Lgr5+ crypt stem cells (1). A fine balance exists in the colon between Wnt pathway activation and inhibition in the determination of this low activity state, and numerous control mechanisms therefore exist to limit Wnt signaling levels (2). Germ line mutation of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) causes familial predisposition to colon cancer (3). In the absence of APC, failure to degrade β-catenin results in unrestricted Wnt signaling, which reaches a threshold to elicit expression of LEF1(4). This high LEF1- β-catenin activity state drives uncontrolled epithelial growth and colon adenocarcinoma (5, 6). Similar low/high Wnt signaling states also distinguish normal hematopoiesis versus leukemias with mutations in Wnt pathway repressor genes (7). Many other markers have been identified from expression profiling that distinguish colon cancer from normal intestinal stem cell populations (3). Some of these factors have been shown to function as suppressors of the Wnt pathway, such as Rnf43, an E3 ligase that ubiquitinates frizzled receptors (8). Although in principle, such markers might be useful in detecting a high-activity state in a variety of human diseases, it has yet to be shown whether pathological Wnt signaling can be achieved in non-genetically-based conditions.

Oligodendrocytes are the myelinating cells of the central nervous system (CNS) and are cellular targets of injury in human disease such as multiple sclerosis (MS) (9) and neonatal white matter injury (WMI) leading to cerebral palsy (CP) (10, 11). Pathological analysis of these demyelinated lesions has revealed the presence of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) arrested at an immature/premyelinating stage (12–14). As remyelination of experimental rodent demyelinated lesions is reproducibly efficient, why do human lesions fail to myelinate? This question prompted us to investigate whether a high pathological Wnt tone could be demonstrated in human neonatal subcortical white matter affected by hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), despite the fact that this is an injury-induced, non-genetic condition.

Results

Common markers of high Wnt tone across diverse tissue types

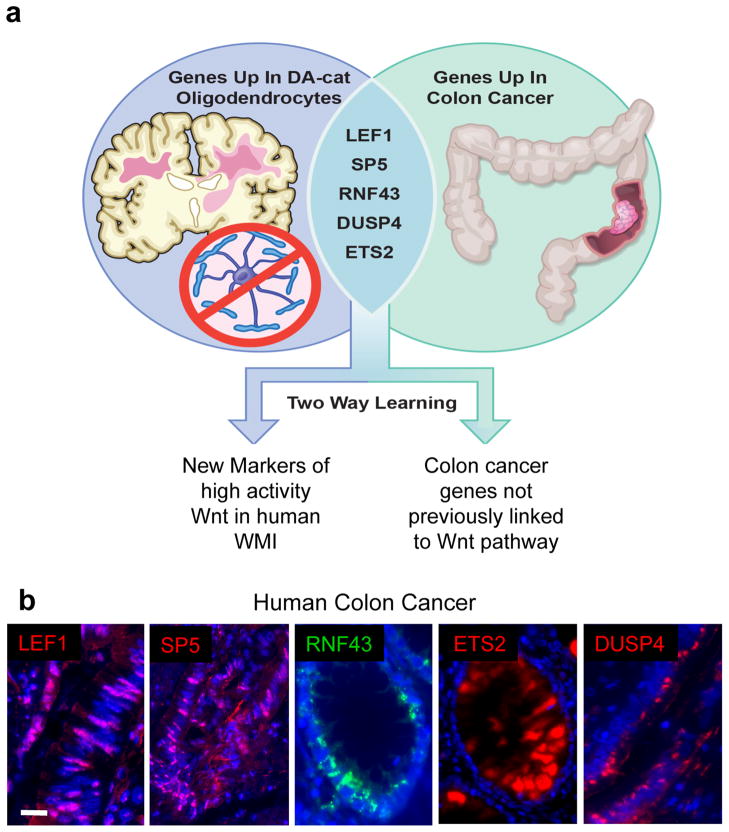

Although Wnt signaling can delay timing of OPC differentiation (15–18), it is unclear whether signaling can achieve pathological-high levels to account for fixed demyelinated lesions in human injury. Indeed, the notion of a high-activity Wnt signaling state in human WMI, or other non-genetic disorders, has not been investigated. To define markers for high Wnt signaling across various tissues, we first compared mRNA transcripts upregulated in mouse Wnt-activated OPCs (Olig2cre/DA-Cat: (15)) and human colon carcinomas that are commonly driven by mutations of the Wnt pathway such as loss of APC function (Suppl. Tab. 1; (2, 3)). This revealed over 47 genes with significant upregulation (Suppl. Tab. 1). We reasoned that such information might identify both novel targets of the Wnt pathway in colon cancer and new high-activity pathway markers in OPCs (Fig. 1a). We focused on LEF1, SP5, RNF43, DUSP4 and ETS2 based on the following criteria: (1) upregulation associated with high-activity Wnt signaling in other studies, (2) known functions in colon cancer and (3) markers available for immunohistochemistry (IHC) in human and rodent samples. All five markers were expressed in adenocarcinoma (Fig. 1b). DUSP4, a MAP-kinase phosphatase protein has not previously been reported as a Wnt-activated target; thus, our approach serves as a gene discovery tool.

Fig. 1.

Common markers of high activity Wnt signaling across diverse tissue types. (a) Schematic to show strategy for comparison of mRNA transcripts upregulated in Wnt-activated OPCs (Olig2cre/DA-Cat)(15) with those upregulated in human colon carcinomas (3). (b) The markers LEF1, SP5, RNF43, ETS2 and DUSP4 are expressed in human colon adenocarcinoma. Scale bar represents 15 μm.

High activity Wnt elicits Lef1 and OPC maturation arrest

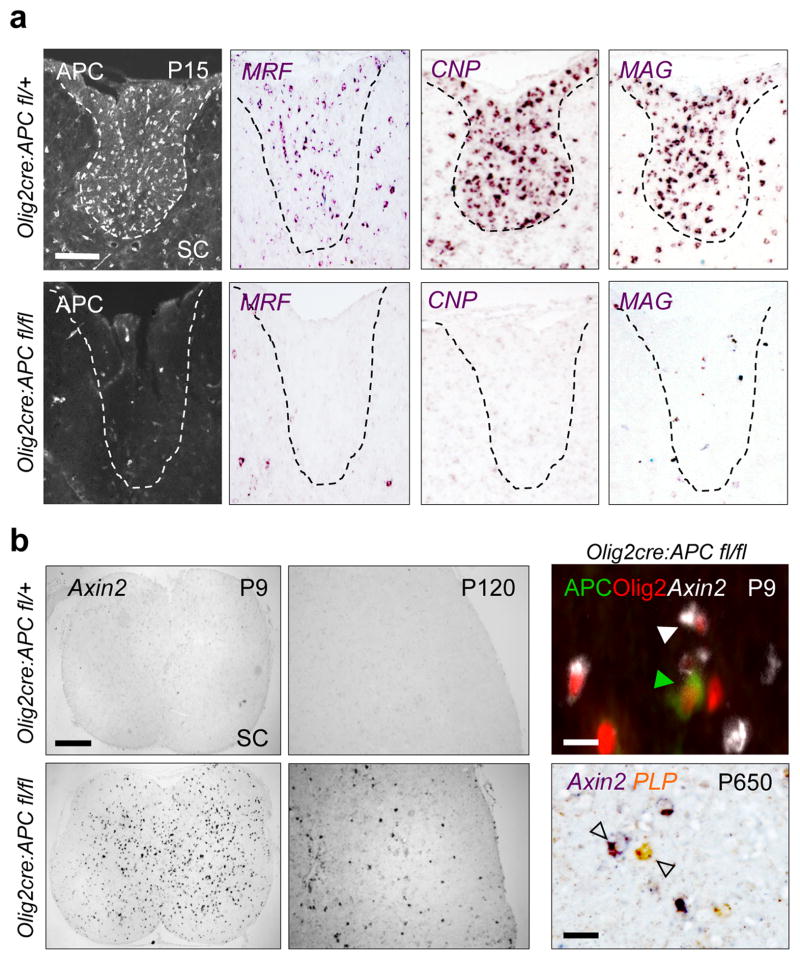

In the adult mammalian CNS, APC expression is specific to OPCs upon cell cycle exit and mature oligodendrocytes (Suppl. Fig. 1). We generated Olig2cre, APCfl/fl mice, which resulted in ~85% efficiency of APC protein loss in OPCs and ~15% “escapees” that failed to delete APC (Suppl. Fig. 2). While numbers of OPCs were normal in brain and spinal cord (Suppl. Fig. 2b), APC-deficient OPCs showed irreversible maturation arrest and failed to express myelin regulatory factor (Fig. 2a)(19), or the mature oligodendrocyte markers Cnp, Mag (Fig. 2a), Mal, Plp and Fa2h (Suppl. Fig. 2b, Suppl. Fig. 3b). APC-deficient OPCs expressed greatly elevated levels of the Wnt transcriptional target Axin2 (Fig. 2b, Suppl. Fig. 4). Only “escapees” of Olig2-cre activity that expressed APC were capable of differentiation to NOGO-A-positive mature oligodendrocytes (Suppl. Fig. 3a).

Fig. 2.

High activity Wnt signaling causes permanent OPC maturation arrest. (a) OPCs lacking APC fail to undergo a differentiation program during development and fail to express mRNAs for multiple mature oligodendrocyte markers, including MRF, CNPase, and MAG, as seen at postnatal day 15 (P15) in the spinal cord (SC) of Olig2-cre, APCfl/fl mice. Scale bar represents 100 μm. (b) APC-deficient OPCs expressed greatly elevated levels of the Wnt transcriptional target Axin2 in P9 SC (which remains elevated at P120), and remain persistently undifferentiated as late as P650. Scale bar represents 300 μm (left panel), 10 μm (right panels).

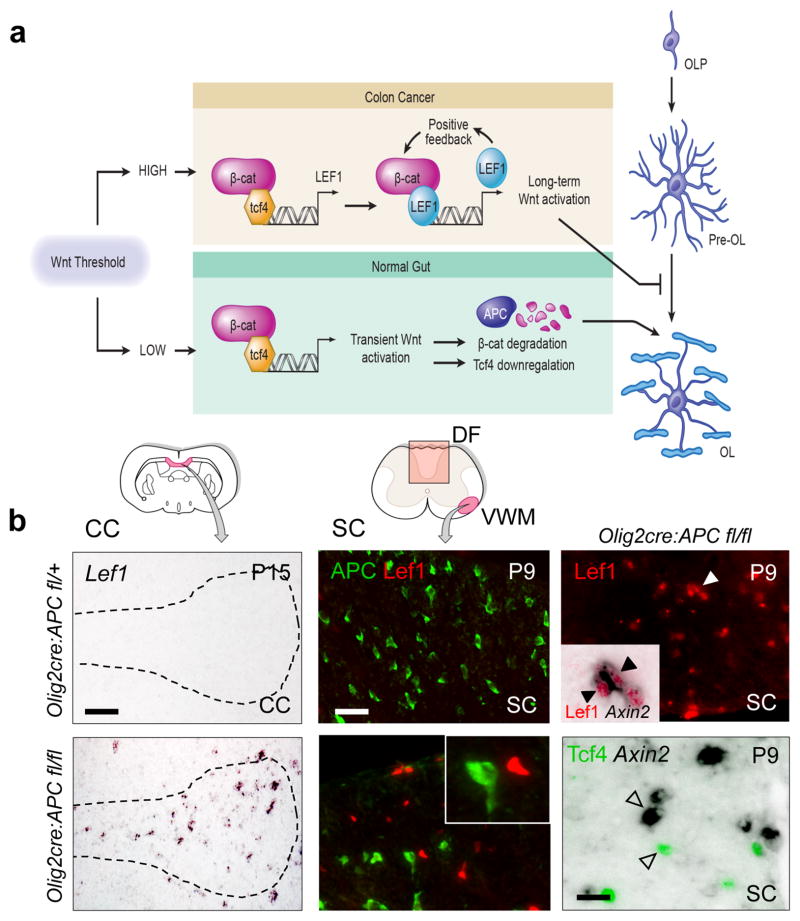

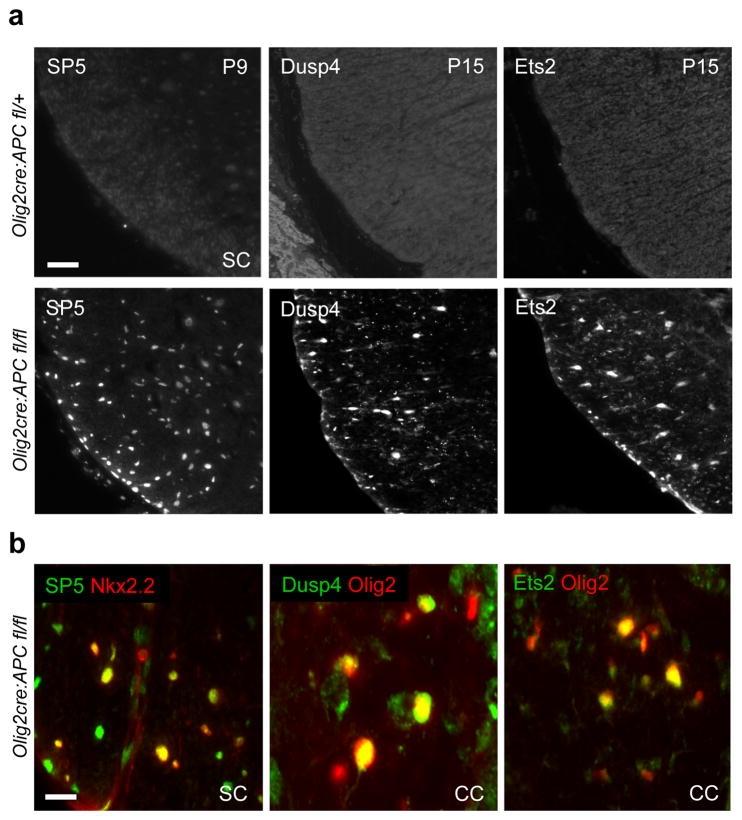

High-activity Wnt signaling in colon cancer reaches a threshold to elicit the expression of LEF1, a reported target of the Wnt pathway, and involves a subsequent switch from a TCF4-β–catenin to a LEF1-β–catenin complex (Fig. 3a; (4)). Once activated, LEF1 participates in a feed-forward loop driving its own expression, which is critical for the high-activity state. As shown (Fig. 3b), Lef1 is not expressed during normal oligodendrocyte development; however, we observed robust Lef1 expression in the corpus callosum and spinal cord of Olig2-cre, APCfl/fl animals, suggesting a high Wnt signaling threshold had been reached. Such APC-deficient OPCs expressed high levels of Axin2 and remained permanently undifferentiated (Fig. 2b, Suppl. Fig. 5), in keeping with other recent findings (20). Conversely, Axin2 expression was undetectable in APC-intact, Tcf4-positive OPCs (Fig. 3b). A fascinating finding is that such OPCs express the high activity markers SP5, Dusp4 and Ets2 (Fig. 4a and 4b). However, unlike Wnt-driven cancers of gut and hematopoetic systems, which respond to mitogenic Wnt signaling, we did not observe hyperproliferation of OPCs or glioma (Suppl. Fig. 6). In summary, high Wnt tone in OPCs is marked by the expression of Lef1 and acts purely to block differentiation (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

The switch to high-activity Wnt signaling in colon cancer (4) involves a switch from a TCF4-β–catenin to a LEF1-β–catenin complex (a). Once activated, LEF1 (absent in normal colon) participates in a feed-forward loop driving its own expression. (b) Lef1 is not expressed during normal oligodendrocyte development in Olig2-cre, APCfl/+ heterozygous mice (which have lost one allele of APC in oligodendrocyte lineage), but there is robust expression of Lef1 mRNA in the corpus callosum (CC)(Scale bar represents 70 μm) and Lef1 protein in spinal cord (SC)(Scale bar represents 30 μm) of Olig2-cre, APCfl/fl animals at postnatal day 15 (P15) and P9 respectively, and these cells expressed high levels of Axin2 (black arrows inset). Conversely, Axin2 was not detected in the APC-intact, Tcf4-positive OPCs (arrowheads)(Scale bar represents 10 μm).

Fig. 4.

Novel markers of high activity Wnt signaling in OPCs. (a) OPCs in Olig2-cre, APCfl/fl spinal cord at P9 and P15 express the high threshold Wnt signaling markers SP5, Dusp4 and Ets2, whereas these are undetectable in mice with heterozygous loss of one APC allele in oligodendrocyte lineage. Scale bar represents 60 μm. (b) High threshold Wnt signaling markers are expressed in Nkx2.2+ and Olig2+ OPCs in SC and corpus callosum (CC) of Olig2-cre, APCfl/fl mice. Scale bar represents 15 μm.

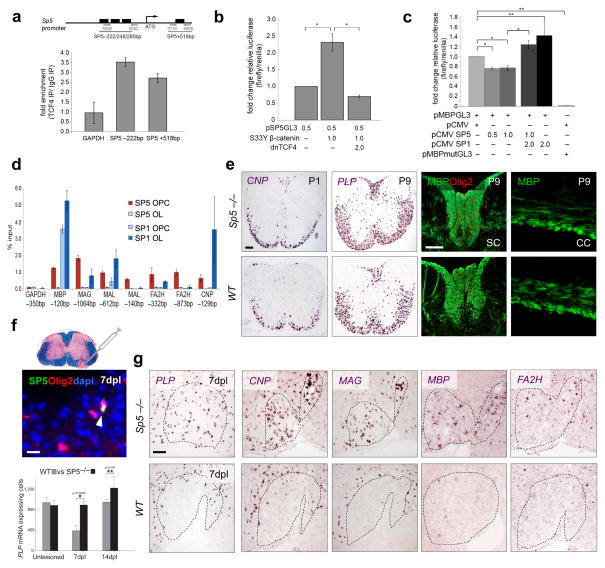

SP5 is a Wnt target that inhibits myelin gene expression

We investigated SP5, encoding a zinc finger type transcription factor of the SP/KLF family, which was the most highly upregulated transcription factor in Wnt-activated OPCs. We first asked whether SP5 was a direct Wnt target. As shown (Fig. 5a), Tcf4 binds to consensus binding sites at the SP5 locus in OPCs as shown by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). SP5 luciferase reporter gene activation was observed in the presence of β-catenin and endogenous Tcf4 in OPCs, and was inhibited by dominant-negative Tcf4 (Fig. 5b). The related factor SP1 binds to the myelin basic protein (MBP) enhancer to activate expression (21). As shown (Fig. 5d, Suppl. Fig. 7), SP5 directly bound multiple myelin gene loci in OPCs, but not mature oligodendrocytes while the converse was the case for SP1, which showed preferential binding at myelin genes in mature oligodendrocytes. SP5 expression inhibited baseline MBP levels, while SP1-induced activation of MBP enhancer activity (Fig. 5c). These findings indicate direct activation of SP5 by Wnt signaling within OPCs, and that SP5 proteins inhibit myelin gene expression through competition with SP1.

Fig. 5.

Transcription factor SP5 is a Wnt target that inhibits mature oligodendrocyte gene expression. SP5 was the most highly upregulated transcription factor in Wnt-activated OPCs. (a) Sp5 is a target of the Wnt pathway in OPCs in vitro. There are predicted Tcf4 binding sites at the SP5 promoter locus, and ChIP demonstrates Tcf4 binding at these predicted sites in OPCs. (b) Sp5 transcription is increased with Wnt pathway activation, as SP5 luciferase reporter gene activation was observed in the presence of β-catenin (dominant active SY33) and endogenous Tcf4 in OPCs, and was inhibited by transfection of dominant-negative Tcf4 (dnTCF4) (t test * p< 0.05). (c) MBP luciferase reporter gene activation in vitro in OPCs is inhibited by transfection with SP5, and this also inhibited SP1-induced activation of MBP enhancer activity (t test * p< 0.05, ** p<0.01). (d) ChIP showed that SP5 directly bound multiple myelin gene promoter loci (MBP, MAG, MAL, FA2H, CNPase) in OPCs but not mature oligodendrocytes while the converse was observed for SP1. (e) Oligodendrocyte development proceeds normally in SP5−/− animals with normal expression of CNPase and MBP mRNA at P1 and P9 respectively in the SC, and MBP protein in SC and CC. Scale bar represents 100 μm. (f) SP5 expression is seen in a subset of Olig2+ cells during wildtype mouse remyelination at 7dpl (Scale bar represents 10 μm). SP5−/− animals showed acceleration of OPC differentiation in the mouse model of remyelination using focal injection of lysolecithin into adult spinal cord white matter, with significant increases in number of cells expressing PLP mRNA at 7 days post lesioning (7dpl) and 14dpl (t test * p = 0.0002, ** p = 0.04, n=4). (g) SP5−/− animals showed acceleration of OPC differentiation during remyelination and precocious expression of myelin genes Plp, Cnp, Mag, Mbp and Fa2h at 7dpl compared to wildtype (WT) animals. Scale bar represents 100 μm. Error bars represent s.d.

SP5-null animals are viable without known gut or white matter abnormalities (22). Consistent with this, we found that oligodendrocyte development proceeds normally in SP5−/− animals (Fig. 5e, Suppl. Fig. 8). We next used focal injection of lysolecithin into adult spinal cord white matter to assess kinetics of remyelination. Compared to low SP5 expression levels in developing WT OPCs (Fig. 4a), we observed increased SP5 expression levels in OPCs during remyelination (Fig. 5f). Strikingly, SP5−/− animals showed acceleration of OPC differentiation during remyelination and precocious expression of myelin genes Mag, Cnp, Fa2h, Mbp and Plp at 7-days post-lesion (dpl)(Fig. 5f and 5g, Suppl. Fig. 9). These findings indicate that SP5 is a direct Wnt target and the first transcription factor identified whose function is required to delay kinetics of normal remyelination. Further, they suggest remyelination achieves an “intermediate” Wnt signaling state characterized by increased expression of SP5 and requirement for SP5-function.

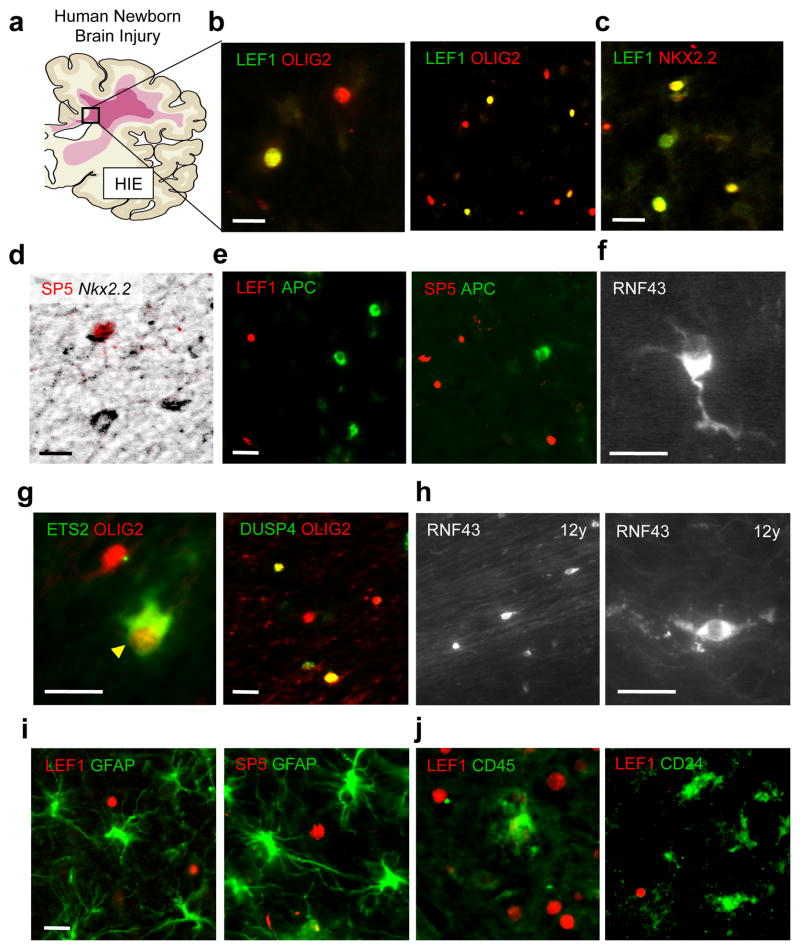

OPCs in human WMI express multiple novel genes in common with colon cancer

Subcortical WMI occurs in term infants that suffer severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE; Fig. 6a). As shown (Fig. 6b–d, and g), immature oligodendrocyte lineage cells in such lesions expressed markers of high activity Wnt signaling (i.e., LEF1, SP5, ETS2, DUSP4, RNF43). Surprisingly, such OPCs (Olig2+, Nkx2.2+) that co-expressed LEF1 and SP5 (Fig. 6c and d) in these lesions were uniformly APC-negative (n =300 Lef1+ cells, three independent HIE cases)(Fig. 6e), suggesting deficient Wnt repressor tone. Indeed, RNF43 was expressed in cells with the simple bipolar morphology of OPCs in neonatal WMI (Fig. 6f), and in a chronic white matter lesion from a 12-year old child with CP (Fig. 6h), consistent with the possibility of a long-standing high-activity Wnt signaling state.

Fig. 6.

OPCs in human neonatal WMI express multiple genes in common with colon cancer. (a) Subcortical WMI occurs in human term infants that suffer severe hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE). (b) High threshold Wnt signaling marker LEF1 is expressed in a subset of Olig2+ oligodendrocyte lineage cells in human HIE. (c) A proportion of immature OPCs (Nkx2.2+) co-expressed LEF1 (c) and SP5 (d) in these lesions and were always APC-negative (e). (g) Immature OPCs in such lesions expressed additional markers of high threshold Wnt signaling (ETS2, DUSP4). RNF43 was expressed in cells with the simple bipolar morphology of OPCs in neonatal WMI (f), and in a chronic WMI lesion from a 12-year old child with cerebral palsy (h). LEF1 and SP5 were not expressed by either GFAP+ astrocytes (i) or inflammatory cells expressing CD45 or CD24 markers (j) in lesions of human HIE. Scale bars represent 10 μm.

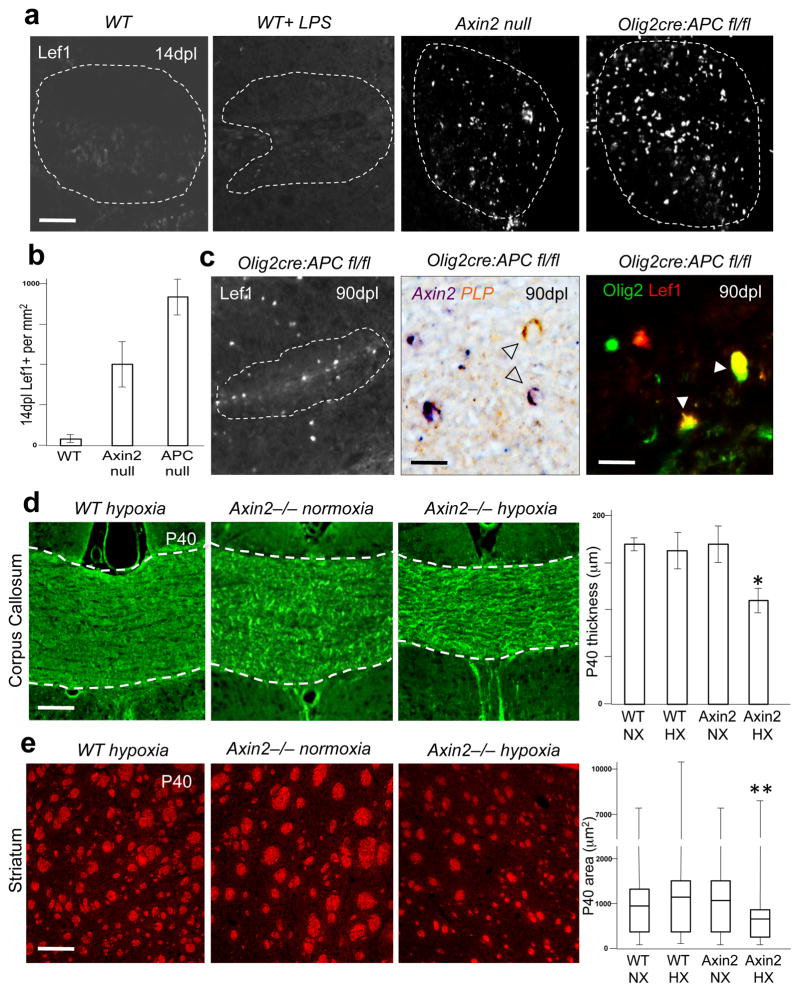

Loss of Wnt repressor tone determines transition to high activity signaling

Given these findings, we further investigated the function of Wnt repressor tone during remyelination, and compared Lef1 expression in animals that were either wild type, Axin2−/− or Olig2-cre, APCfl/fl (Fig. 7a). Whilst Axin2 is a direct target of the Wnt pathway (Fig. 2b), Axin2−/− mice also have a hyperactive Wnt tone, as the Axin2 protein is a known repressor of the pathway through functions in the β–catenin degradation complex (16, 23). In the lysolecithin gliotoxic model, white matter oligodendrocytes are initially killed off and must be replaced by newly generated OPCs. As expected, based on findings from development (Fig. 2), APC-null oligodendrocytes show a permanent block in remyelination with persistence of Lef1 and Axin2 expression for as long as 90 dpl (Fig. 7c, Suppl. Fig. 10). Moreover, we observed that numbers of Lef1+ cells were increased in lesions inversely to Wnt repressor tone (Fig. 7b), suggesting that the percentage of Lef1+/Olig2+ OPCs comprises an index of Wnt activity levels.

Fig. 7.

Loss of Wnt repressor tone determines transition to pathological Wnt signaling. (a) High threshold wnt marker Lef1 is expressed at very low levels in wildtype (WT) mouse remyelination (lysolethicin focal injection spinal cord)(Scale bar represents 100 μm) at 14dpl and is not increased by intraperitoneal injection of LPS during remyelination, but Lef1 expression increased very significantly in lesions inversely to wnt tone in Axin2−/− or Olig2-cre, APCfl/fl mice (a and b). (c) APC-null oligodendrocytes show a permanent block in differentiation to a remyelinating stage with persistence of Lef1 and Axin2 expression at 90 days after injury (90dpl). Scale bar represents 10 μm. (d) Wnt repressor function regulates neonatal WMI, as demonstrated using mild/chronic neonatal hypoxemia in developing mice (10% FiO2, postnatal day 3–7). Hypoxia in wildtype mice (WT HX) causes only transient delay of myelination at P11 (data not shown) with full recovery of corpus callosum thickness (d) and striatal thickness (e) to wildtype normoxic levels (WT NX) by P40 (Scale bars represent 50 μm). Axin2−/− mice kept in normoxic conditions (Axin2 NX) have similar white matter volumes to WT animals at P40. Axin2−/− mice kept in hypoxic conditions (Axin2 HX) demonstrate significantly reduced corpus callosum thickness (2 way ANOVA *p = 0.023, n=4) and striatum white matter volumes (2 way ANOVA **p = 0.0009, n=4) at P40 compared with WT HX. Error bars represent s.e.m.

To assess whether Wnt repressor function regulates neonatal WMI, we tested effects of mild/chronic neonatal hypoxemia (10% FiO2, P3–P7) on white matter volume throughout the brain. In wild type mice, this treatment causes only transient delay of myelination at P11 (data not shown) with full recovery of white matter volume by P40 (Fig. 7d and e). In contrast, Axin2−/− mice demonstrated selective white matter volume deficits, while grey matter volume was not significantly affected. Together these findings suggest that a deficient Wnt repressor tone and hypoxia is sufficient for permanent effects on white matter.

Discussion

Pathological Wnt signaling in cancers of colon and blood are associated with a high-activity state in genetically predisposed cells. We demonstrate for the first time that various Wnt pathway activity states can exist in oligodendrocyte lineage, and distinguish the normal process of myelination from pathological OPC differentiation block, in a dose-dependent fashion. We show that developing OPCs require APC function to prevent transition to a high-activity Wnt signaling state that permanently blocks their differentiation. Considering the requirement for APC in both colonic stem cells and OPCs, it is possible that individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome, who carry heterozygous loss-of-function APC mutations, who are reported to suffer from intellectual disability (24), might be prone to WMI. OPCs with high-activity Wnt signaling express many known markers in common with colon cancer including Lef1, SP5, Ets2, Rnf43 (4, 8, 25, 26) as well as newly identified Dusp4 (this study). Further studies are needed to define the tissue-specific functions of such putative pathway components downstream of Wnt signaling in OPCs. As one example, we found that SP5 is a direct Tcf4 target, which acts in a competitive balance with the related transcription factor SP1 for binding at mature myelin gene loci, and is essential to inhibit kinetics of OPC differentiation after demyelinating injury.

Akin to the colon, high activity Wnt signaling in OPCs reaches the threshold to induce the expression of Lef1, with a subsequent switch from a TCF4-β–catenin to a LEF1-β–catenin dependent complex. We show that remyelination in a simple murine model and wild type genetic background does not result in high activity Wnt signaling, as Lef1-expressing OPCs are not observed. Nor did we observe Lef1 expression when other factors such as hypoxia or LPS-induced inflammation were added to gliotoxic injury (Fig. 7a and data not shown). In contrast, OPCs that carry heterozygous or homozygous mutations of Axin2 or APC repressor genes show Lef1 expression in OPCs in a dose dependent manner. Thus, Wnt repressor tone is the critical factor that regulates transition to a high activity state after injury. Indeed, Axin2−/− mice subjected to mild hypoxia develop fixed deficits in white matter volume at P40 in dramatic contrast to wild type controls that show no injury whatsoever.

Genetic alterations in Wnt pathway repressors lead to certain cancers as well as non-cancerous pathology (e.g., bone hypertrophy) (27). Surprisingly, we found that OPCs in human neonatal HIE (i.e., a non-genetic lesion) expressed high-activity markers similar to colon cancer, suggesting a parallel state of pathological Wnt signaling. This pathological Wnt tone in OPCs in human HIE goes some way to explaining why human lesions may fail to myelinate. However, further investigation is needed to determine how this high-activity state is achieved. One possibility is that hypoxic and/or inflammatory factors result in epigenetic dysregulation of Wnt repressor tone. In this regard, it is noteworthy that OPCs with high-Wnt tone consistently lacked APC expression. APC might be regulated at the transcriptional, translational level (28), or could be mis-localized within OPCs (29) in the setting of injury. For example, hypoxia in colon cancer cell lines affects APC levels via a direct effect of hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) at the APC promoter (30). Secondly, several previous studies indicate that epigenetic silencing of Wnt repressors in certain colon cancers may contribute to disease progression (31, 32), which could represent a pre-cancerous ‘kindling state’ that selects for somatic mutations. Further research is needed to establish epigenetic mechanisms that mitigate against Wnt repressor tone in human WMI and the extent to which a high-activity Wnt signaling state exists in other non-genetically-based human diseases.

Methods

Human HIE neonatal tissue and human colon cancer tissue

All human HIE tissue was collected in accordance with guidelines established by the University of California San Francisco Committee on Human Research (H11170-19113-07) as previously described (16, Fancy et al., Nat Neurosci 14, 1009 (2011)). Immediately after procurement, all brains were immersed in phosphate buffered saline with 4% paraformaldehyde for three days. On day 3, the brain was cut in the coronal plane at the level of the Mamillary Body and immersed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for an additional three days. Post fixation, all tissue samples were equilibrated in PBS with 30% sucrose for at least 2 days. Following sucrose equilibration, tissue was placed into molds and embedded with OCT for 30 minutes at room temperature followed by freezing in dry ice-chilled ethanol. UCSF neuropathology staff performed brain dissection and its evaluation. The diagnosis of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) requires clinical and pathological correlation; no widely accepted diagnostic criteria is present for the pathological diagnosis of HIE. None of the HIE cases evaluated in this study were identical but did show consistent evidence of diffuse white matter gliosis, as evaluated by the qualitative increase in the number of GFAP positive cells in addition to the increased intensity of GFAP staining.

Human colon cancer samples were from US Biomax, T055 colon cancer tissue array (4×(2×3) array) with 6 cases/24 cores per slide.

Comparison of transcripts in Wnt-activated OPCs with human colon carcinomas

We retrieved log(2) fold-change expression values from a previous study using Olig2-Cre/DA-Cat mice (15, Fancy et al., Genes Dev 23, 1571 (2009)) and another on colon cancer RNA profiling (3, Nature 487, 330 (2012)). Transcripts elevated in either data set or with a positive normalized “domain knowledge score” (DKS) were selected (Suppl Table 1). Normalized DKS was defined as the ratio of the number of articles in PubMed supporting upregulation vs. downregulation of each transcript. The PubMed query terms for upregulation were: (“elevated expression” OR “upregulated” OR “increase” OR “overexpression” OR “highly expressed” OR “enhanced expression”) AND (“colorectal” OR “colon” OR “rectal”). The PubMed query terms for downregulation were: (“reduced expression” OR “downregulated” OR “decrease”) AND (“colorectal” OR “colon” OR “rectal”).

Mice

Animal husbandry and procedures were performed according to UCSF guidelines under IACUC approved protocols.

APC-fl/fl

A conditional (floxed) allele of APC provided by Dr. R. Fodde (Leiden University) (Robanus-Maandag, E.C., et al., Carcinogenesis, 31(5): p. 946–52 (2010)). Through intercrosses with an early Olig2 pan lineage cre-recombinase we can achieve conditional knockout of APC in OPCs.

SP5-LacZ

The SP5-LacZ mouse has been described previously (22, Harrison et al., Developmental biology 227, 358 (2000)) and has a LacZ knocked into the SP5 locus.

Axin2-LacZ

The Axin2-LacZ mouse has been described previously (Lustig, B, et al. Mol Cell Biol 22:1184–1193 (2002)). The LacZ insert mimics the expression pattern of Axin2 but does not lead to a detectable phenotype in the heterozygous state. In the homozygous state, this effectively acts as an Axin2 null animal.

Olig2-tva-cre

A multi-functional mouse line was constructed previously (Schüller, U, et al. Cancer Cell 14:123–134 (2008)) by inserting tva, an avian-specific retroviral receptor, and an IRES-cre recombinase cassette into the endogenous Olig2 locus by homologous recombination. This Olig2-cre allowed for cre mediated activity in oligodendrocyte lineage cells.

Immunohistochemistry and antibodies

The primary antibodies used were as follows: APC (1:100 mouse monoclonal OP80, Calbiochem), Lef1 (1:200 Rabbit mAb C12A5, Cell Signaling), anti-human Lef1 (1:100 rabbit polyclonal Ab22884, Abcam), RNF43 (1:200 rabbit polyclonal Ab84125, Abcam), ETS2 (1:200 chicken polyclonal Ab17901, Abcam), DUSP4 (1:200 rabbit polyclonal Ab60229, Abcam), SP5 (1:200 rabbit polyclonal Ab36593, Abcam), Tcf4 (1:100 mouse monoclonal 6H5-3, Upstate), Olig2 (1:3000 rabbit polyclonal from CD Stiles, Harvard), Nkx2.2 (1:100 mouse monoclonal, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), PDGFRα (1:200 rat 558774, BD Biosciences), NOGO-A (1:200 rabbit, Millipore), and GFAP (1:500 mouse, Sigma).

Murine lysolecithin focal demyelination model

Demyelinated lesions were produced in the ventrolateral or dorsal spinal cord white matter of 8–10 week old Axin2 null, Olig2cre:APCfl/fl and wild-type littermate mice. Anaesthesia was induced and maintained with inhalational isoflurane/oxygen, supplemented with 0.05 ml of buprenorphine (Vetergesic 0.05 mg/ml) given subcutaneously. Having exposed the spinal vertebrae at the level of T12/T13, tissue was cleared overlying the intervertebral space, and the dura was pierced with a dental needle just lateral to midline. A Hamilton needle was advanced through the pierced dura at an angle of 45° and 0.5μl 1% lysolecithin (Lα-lysophosphatidylcholine) was injected into the ventrolateral white matter.

Murine developmental Chronic Hypoxia and statistics

Chronic hypoxic rearing was performed as previously described (Weiss et al., Experimental Neurology, 189: pp. 141–149 (2004)). Briefly, C57/B6 litters were culled to a size of 8 pups, cofostered with a CD1 dam and reared from P3 to P11 in a ventilated hypoxia chamber set to 10% 02 (A-Chamber, Biospeherix, Ltd. Lacona, NY). Following hypoxic rearing animals were returned to normal housing, weened at P28, and sacrificed at P40 as were normoxic controls. Statistical significance for the interaction effect of chronic hypoxic rearing and Axin2 deletion was determined by Two-Way ANOVA tests using the StatPlus software plugin (AnalystSoft) for Microsoft Excel. P-values of less than 0.05 are reported as significant.

Cell counts and statistical measures

For all cell counts, at least four animals per genotype were used for each time point indicated. Cells were counted on three or more non-adjacent sections per mouse and presented as an average +/− standard deviation. Statistical comparisons of cell counts were established using Student t test. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications (15, Fancy et al., Genes Dev 23, 1571 (2009)(16, Fancy et al., Nat Neurosci 14, 1009 (2011). Data collection and analysis were performed blind to the conditions of the experiment. Data were collected and processed randomly, and animals were randomly assigned to treatment groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Rosa Beddington (NIMR Mill Hill, London, UK; deceased) and Terry Yamaguchi (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) for SP5 null mice. We thank Riccardo Fodde (Leiden University) for APC floxed mice. Procurements of human brain tissues have been supported by the University of California MRPI grant #142657. This work was supported by grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (to DHR), the National Institutes of Health (to DHR, EJH), and the Medical Scientist Training Program at the University of California, San Francisco (to EPH). SEB is a Harry Weaver Neuroscience Scholar of the NMSS. DHR is a HHMI Investigator.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

S.P.J.F. conceived of and performed all experiments and analysis, with the exception of the following: E.P.H performed and analyzed all experiments related to in vitro OLP cultures. J.C.S., T.J.Y. and L.S. helped analyze Wnt pathway activation in murine hypoxic injury. S.E.B. performed bioinformatics. E.J.H. procured human brain developmental tissue. S.L. provided advice on ChIP protocol and analysis. D.H.R conceived the experiments and oversaw all aspects of the analysis. The paper was written by S.P.J.F. and D.H.R.

References

- 1.Schuijers J, Clevers H. Adult mammalian stem cells: the role of Wnt, Lgr5 and R-spondins. EMBO J. 2012 Jun 13;31:2685. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012 Jun 8;149:1192. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012 Jul 19;487:330. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hovanes K, et al. Beta-catenin-sensitive isoforms of lymphoid enhancer factor-1 are selectively expressed in colon cancer. Nat Genet. 2001 May;28:53. doi: 10.1038/ng0501-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korinek V, et al. Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC−/− colon carcinoma. Science. 1997 Mar 21;275:1784. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5307.1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu W, et al. Mutations in AXIN2 cause colorectal cancer with defective mismatch repair by activating beta-catenin/TCF signalling. Nat Genet. 2000 Oct;26:146. doi: 10.1038/79859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luis TC, et al. Canonical wnt signaling regulates hematopoiesis in a dosage-dependent fashion. Cell Stem Cell. 2011 Oct 4;9:345. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koo BK, et al. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature. 2012 Aug 30;488:665. doi: 10.1038/nature11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franklin RJ, Ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: from biology to therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Nov;9:839. doi: 10.1038/nrn2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khwaja O, Volpe JJ. Pathogenesis of cerebral white matter injury of prematurity. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2008 Mar;93:F153. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.108837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verney C, et al. Microglial reaction in axonal crossroads is a hallmark of noncystic periventricular white matter injury in very preterm infants. Journal of neuropathology and experimental neurology. 2012 Mar;71:251. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182496429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang A, Tourtellotte WW, Rudick R, Trapp BD. Premyelinating oligodendrocytes in chronic lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2002 Jan 17;346:165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buser JR, et al. Arrested preoligodendrocyte maturation contributes to myelination failure in premature infants. Ann Neurol. 2012 Jan;71:93. doi: 10.1002/ana.22627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jablonska B, et al. Oligodendrocyte regeneration after neonatal hypoxia requires FoxO1-mediated p27Kip1 expression. J Neurosci. 2012 Oct 17;32:14775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2060-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fancy SP, et al. Dysregulation of the Wnt pathway inhibits timely myelination and remyelination in the mammalian CNS. Genes Dev. 2009 Jul 1;23:1571. doi: 10.1101/gad.1806309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fancy SP, et al. Axin2 as regulatory and therapeutic target in newborn brain injury and remyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2011 Aug;14:1009. doi: 10.1038/nn.2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye F, et al. HDAC1 and HDAC2 regulate oligodendrocyte differentiation by disrupting the beta-catenin-TCF interaction. Nat Neurosci. 2009 Jul;12:829. doi: 10.1038/nn.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chew LJ, et al. SRY-box containing gene 17 regulates the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. J Neurosci. 2011 Sep 28;31:13921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3343-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emery B, et al. Myelin gene regulatory factor is a critical transcriptional regulator required for CNS myelination. Cell. 2009 Jul 10;138:172. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lang J, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli regulates oligodendroglial development. J Neurosci. 2013 Feb 13;33:3113. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei Q, Miskimins WK, Miskimins R. The Sp1 family of transcription factors is involved in p27(Kip1)-mediated activation of myelin basic protein gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2003 Jun;23:4035. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4035-4045.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harrison SM, Houzelstein D, Dunwoodie SL, Beddington RS. Sp5, a new member of the Sp1 family, is dynamically expressed during development and genetically interacts with Brachyury. Developmental biology. 2000 Nov 15;227:358. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lustig B, et al. Negative feedback loop of Wnt signaling through upregulation of conductin/axin2 in colorectal and liver tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 2002 Feb;22:1184. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1184-1193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heald B, Moran R, Milas M, Burke C, Eng C. Familial adenomatous polyposis in a patient with unexplained mental retardation. Nature clinical practice Neurology. 2007 Dec;3:694. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y, et al. Elevated expression and potential roles of human Sp5, a member of Sp transcription factor family, in human cancers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006 Feb 17;340:758. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munera J, Cecena G, Jedlicka P, Wankell M, Oshima RG. Ets2 regulates colonic stem cells and sensitivity to tumorigenesis. Stem cells. 2011 Mar;29:430. doi: 10.1002/stem.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baron R, Kneissel M. WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat Med. 2013 Feb;19:179. doi: 10.1038/nm.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran H, Polakis P. Reversible modification of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) with K63-linked polyubiquitin regulates the assembly and activity of the beta-catenin destruction complex. J Biol Chem. 2012 Aug 17;287:28552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.387878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson BR. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of APC regulates beta-catenin subcellular localization and turnover. Nature cell biology. 2000 Sep;2:653. doi: 10.1038/35023605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newton IP, Kenneth NS, Appleton PL, Nathke I, Rocha S. Adenomatous polyposis coli and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 {alpha} have an antagonistic connection. Molecular biology of the cell. 2010 Nov 1;21:3630. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki H, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of SFRP genes allows constitutive WNT signaling in colorectal cancer. Nature genetics. 2004 Apr;36:417. doi: 10.1038/ng1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koinuma K, et al. Epigenetic silencing of AXIN2 in colorectal carcinoma with microsatellite instability. Oncogene. 2006 Jan 5;25:139. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.