Abstract

The properties of water can have a strong dependence on the confinement. Here, we consider a water monolayer nanoconfined between hydrophobic parallel walls under conditions that prevent its crystallization. We investigate, by simulations of a many-body coarse-grained water model, how the properties of the liquid are affected by the confinement. We show, by studying the response functions and the correlation length and by performing finite-size scaling of the appropriate order parameter, that at low temperature the monolayer undergoes a liquid-liquid phase transition ending in a critical point in the universality class of the two-dimensional (2D) Ising model. Surprisingly, by reducing the linear size L of the walls, keeping the walls separation h constant, we find a 2D-3D crossover for the universality class of the liquid-liquid critical point for  , i.e. for a monolayer thickness that is small compared to its extension. This result is drastically different from what is reported for simple liquids, where the crossover occurs for

, i.e. for a monolayer thickness that is small compared to its extension. This result is drastically different from what is reported for simple liquids, where the crossover occurs for  , and is consistent with experimental results and atomistic simulations. We shed light on these findings showing that they are a consequence of the strong cooperativity and the low coordination number of the hydrogen bond network that characterizes water.

, and is consistent with experimental results and atomistic simulations. We shed light on these findings showing that they are a consequence of the strong cooperativity and the low coordination number of the hydrogen bond network that characterizes water.

The study of nanoconfined water is of great interest for applications in nanotechnology and nanoscience1. The confinement of water in quasi-one or two dimensions (2D) is leading to the discovery of new and controversial phenomena in experiments1,2,3,4,5 and simulations4,6,7. Nanoconfinement, both in hydrophilic and hydrophobic materials, can keep water in the liquid phase at temperatures as low as 130 K at ambient pressure2. At these temperatures T and pressures P experiments cannot probe liquid water in the bulk, because water freezes faster then the minimum observation time of usual techniques, resulting in an experimental “no man's land”8. Nevertheless, new kind of experiments9,10 and numerical simulations11 can access this region, revealing interesting phenomena in the metastable state. In particular, Poole et al. found, by molecular dynamics simulations of supercooled water, a liquid-liquid critical point (LLCP), in the “no mans land”, at the end of a first–order liquid-liquid phase transition (LLPT) line between two metastable liquids phases with different density ρ: the high-density liquid (HDL) at higher T and P, and the low-density liquid (LDL) at lower T and P11. The presence of a LLPT is experimentally observed in other systems12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, consistent with theoretical models fitted to water experimental data22,23,24, and is recovered by simulations of a number of models of water11,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 and other anomalous liquids32,33,34,35,36,37. Alternative ideas, and their differences, have been discussed38,39,40,41,42, and it has been debated if experiments on confined water in the “no man's land” can be a way to test these ideas2, motivating several theoretical works43.

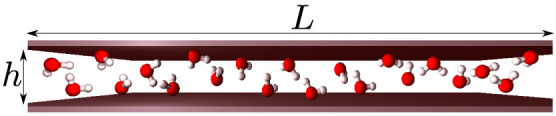

Here, to analyze the thermodynamic properties of water in confinement we consider a water monolayer between hydrophobic walls of area L2 separated by h ≈ 0.5 nm (Fig. 1). Atomistic simulations7 show that water under these conditions does not crystallize, but arranges in a disordered liquid layer, whose projection on one of the surfaces has square symmetry, with each water molecule having four nearest neighbors (n.n.). The molecules maximize their intermolecular distance by adjusting at different heights with respect to the two walls.

Figure 1. Schematic view of a section of the water monolayer confined between hydrophobic walls of size L × L separated by h ≈ 0.5 nm.

We adopt a many-body model that reproduces water properties31,40,44,45,46,47,48,49,50. We simulate ~ 105 state points, each with statistics of 5 × 106 independent calculations, for systems with N = 2.5 × 103, …, 1.6 × 105 water molecules at constant N, P and T, using a cluster Monte Carlo algorithm46,47,48, for a wide range of T and P. All quantities are calculated in internal units, as described in the Methods section.

Results

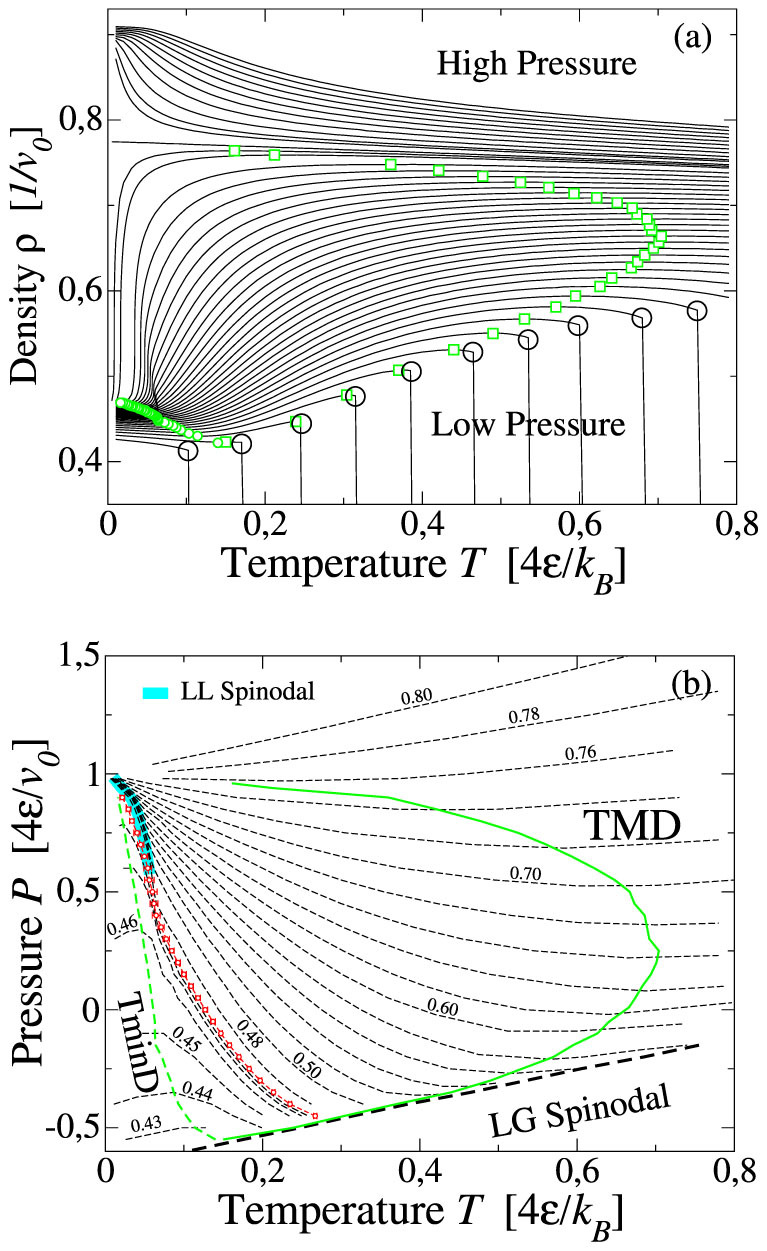

We calculate the density ρ ≡ N/V of the system as function of T along isobars. For a broad range of P, we find a maximum and a minimum of density along each isobar (Fig. 2a) according to experimental evidences for bulk and confined water52. These maxima and minima identify, for each P, the temperature of maximum density (TMD) and the temperature of minimum density (TminD). The TMD locus merges the TminD line as in experiments52 and other models53.

Figure 2.

(a) Isobaric density variation for 104 water molecule. Lines join simulated state points (~ 150 for each isobar). P increases from −0.5 (bottom curve) to 1.5  (top curve). Along each isobar we locate the maximum ρ (green squares at high T) and the minimum ρ (green small circles at low T) and the liquid-gas spinodal (open large circles at low P). (b) Loci of TMD, TminD, liquid-gas spinodal and liquid-liquid spinodal in T − P plane. Dashed lines with labels represent the isochores of the system from ρv0 = 0.43 (bottom) to ρv0 = 0.80 (top). Dashed lines without labels represent intermediate isochores. TMD and TminD correspond to the loci of minima and maxima, respectively, along isochores in the T − P plane. We estimate the critical isochore at ρv0 ~ 0.47 (red circles). All the isochores with 0.47 < ρv0 < 0.76 intersect with the critical isochore for

(top curve). Along each isobar we locate the maximum ρ (green squares at high T) and the minimum ρ (green small circles at low T) and the liquid-gas spinodal (open large circles at low P). (b) Loci of TMD, TminD, liquid-gas spinodal and liquid-liquid spinodal in T − P plane. Dashed lines with labels represent the isochores of the system from ρv0 = 0.43 (bottom) to ρv0 = 0.80 (top). Dashed lines without labels represent intermediate isochores. TMD and TminD correspond to the loci of minima and maxima, respectively, along isochores in the T − P plane. We estimate the critical isochore at ρv0 ~ 0.47 (red circles). All the isochores with 0.47 < ρv0 < 0.76 intersect with the critical isochore for  along the LL spinodal (tick turquoise) line.

along the LL spinodal (tick turquoise) line.

At low T a discontinuous change in ρ is observed for  , where the parameters v0 and

, where the parameters v0 and  are explained in the Methods section, as it would be expected in correspondence of the HDL-LDL phase transition. At very high pressures (

are explained in the Methods section, as it would be expected in correspondence of the HDL-LDL phase transition. At very high pressures ( ) the system behaves as a normal liquid, with monotonically increase of ρ upon decrease of T.

) the system behaves as a normal liquid, with monotonically increase of ρ upon decrease of T.

We estimate the liquid-to-gas (LG) spinodal at  for low T (Fig. 2) as the temperature along an isobar at which we find a discontinuous jump of ρ to zero value by heating the system. The LG spinodal identifies the locus of the stability limit of liquid phase with respect to the gas phase: at pressures below the LG spinodal in the P − T plane is no longer possible to equilibrate the system in the liquid phase. The LG spinodal continues at positive pressures ending in the LG critical point (data not shown). We observe that the TMD line approaches the LG spinodal, without touching it (Fig. 2). We recover the LG spinodal also as envelope of isochores (Fig. 2b).

for low T (Fig. 2) as the temperature along an isobar at which we find a discontinuous jump of ρ to zero value by heating the system. The LG spinodal identifies the locus of the stability limit of liquid phase with respect to the gas phase: at pressures below the LG spinodal in the P − T plane is no longer possible to equilibrate the system in the liquid phase. The LG spinodal continues at positive pressures ending in the LG critical point (data not shown). We observe that the TMD line approaches the LG spinodal, without touching it (Fig. 2). We recover the LG spinodal also as envelope of isochores (Fig. 2b).

We find a second envelope of isochores at lower T and higher P, pointing out the liquid-to-liquid (LL) spinodal. Indeed, the two spinodals associated to the LLPT, i.e. the HDL-to-LDL spinodal and the LDL-to-HDL spinodal, collapse one on top of the other and are indistinguishable within our numerical resolution. Nevertheless, we clearly see that isochores are gathering around the points ( ,

,  ) and (

) and ( ,

,  ), where kB is the Boltzmann constant, marking two possible critical regions (Fig. 2b).

), where kB is the Boltzmann constant, marking two possible critical regions (Fig. 2b).

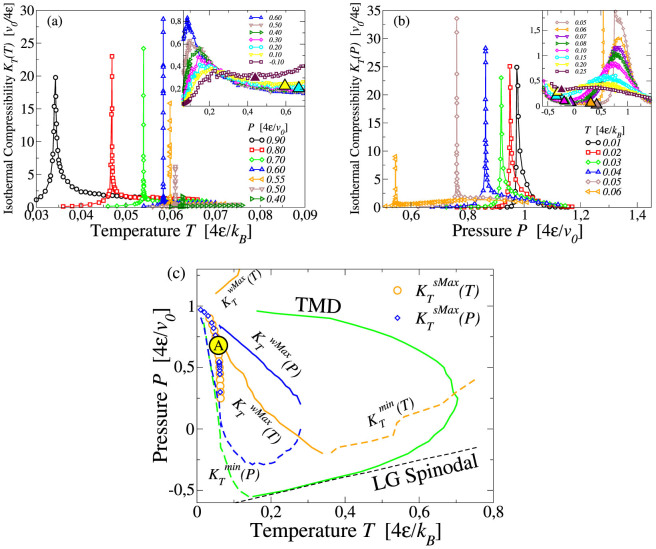

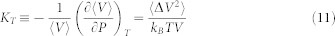

We calculate the isothermal compressibility by its definition KT ≡ −(1/〈V〉) (∂〈V〉/∂P)T and by the fluctuation-dissipation theorem KT = 〈ΔV2〉/kBTV along isobars, KT(T), and along isotherms, KT(P) (Fig. 3), where 〈V〉 ≡ V is the average volume and 〈ΔV2〉 the volume fluctuations. We find two loci of extrema for each quantity KT(T) and KT(P): one of strong maxima and one of weak maxima. The loci of strong maxima in KT(T) and KT(P), respectively  and

and  , overlap within the error bar with the LL spinodal. The maxima

, overlap within the error bar with the LL spinodal. The maxima  and

and  increase in the range of

increase in the range of  and

and  (Fig. 3), consistent with the existence of a critical region. The stronger maxima disappear for

(Fig. 3), consistent with the existence of a critical region. The stronger maxima disappear for  .

.

Figure 3.

(a) Loci of strong maxima ( ), weak maxima (

), weak maxima ( in the inset) and minima (

in the inset) and minima ( marked with large triangles in the inset) along isobars for KT(T). (b) Loci of strong maxima (

marked with large triangles in the inset) along isobars for KT(T). (b) Loci of strong maxima ( ), weak maxima (

), weak maxima ( in the inset) and minima (

in the inset) and minima ( marked with large triangles in the inset) along isotherms. The weak maxima merge with minima. (c) Projection of extrema of KT in T − P plane. The strong maxima (symbols), weak maxima (solid lines) and minima (dashed lines) of KT(T) (orange) and KT(P) (blue) form loci in T − P plane that relate to each other and intersect with the TMD line following the thermodynamic relations discussed in the text. The large yellow circle with label A identifies the region where

marked with large triangles in the inset) along isotherms. The weak maxima merge with minima. (c) Projection of extrema of KT in T − P plane. The strong maxima (symbols), weak maxima (solid lines) and minima (dashed lines) of KT(T) (orange) and KT(P) (blue) form loci in T − P plane that relate to each other and intersect with the TMD line following the thermodynamic relations discussed in the text. The large yellow circle with label A identifies the region where  and

and  converge and display the largest maxima, consistent with the occurrence of a critical point in a finite-size system. Symbols not explained here are as in Fig. 2.

converge and display the largest maxima, consistent with the occurrence of a critical point in a finite-size system. Symbols not explained here are as in Fig. 2.

We find also loci of weak maxima,  and

and  and minima

and minima  and

and  . The loci of weak extrema and minima of KT(T) and KT(P) do not coincide in the T − P plane. The locus of weak maxima along isotherms

. The loci of weak extrema and minima of KT(T) and KT(P) do not coincide in the T − P plane. The locus of weak maxima along isotherms  merges with the locus of minima

merges with the locus of minima  at the point where the slope of both loci is ∂P/∂T → ∞. Furthermore, both loci approach to the LL spinodal at high P. The locus of weak maxima along isobars

at the point where the slope of both loci is ∂P/∂T → ∞. Furthermore, both loci approach to the LL spinodal at high P. The locus of weak maxima along isobars  approaches the LL spinodal where KT exhibits the strongest maxima, and merges with the locus of minima

approaches the LL spinodal where KT exhibits the strongest maxima, and merges with the locus of minima  where the slope of both loci is ∂P/∂T → 0 (data at high P and T not shown in Fig 3). This locus intersects the TMD at its turning point. Indeed, as reported in Ref. 39 and in the Methods section, the temperature derivative of isobaric KT along the TMD line is related to the slope of TMD line

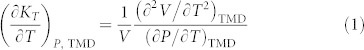

where the slope of both loci is ∂P/∂T → 0 (data at high P and T not shown in Fig 3). This locus intersects the TMD at its turning point. Indeed, as reported in Ref. 39 and in the Methods section, the temperature derivative of isobaric KT along the TMD line is related to the slope of TMD line

|

where all the quantities are calculated along the TMD line. Hence the locus of extrema in KT(T), where (∂KT/∂T)P = 0, crosses the TMD line where the slope (∂P/∂T)TMD is infinite. We observe also that the weak maxima of KT(T) and KT(P) increase as they approach the LL spinodal. All loci of extrema in KT are summarized in Fig. 3.

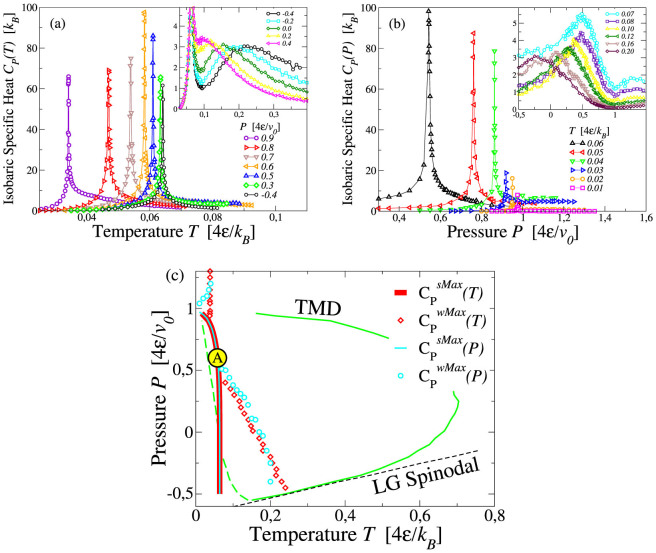

Next we calculate the isobaric specific heat CP ≡ (∂〈H〉/∂T)P = 〈ΔH2〉/kBT along isotherms and isobars, where  is the average enthalpy,

is the average enthalpy,  is the Hamiltonian as defined in the Methods section, 〈ΔH2〉 is the enthalpy fluctuations (Fig. 4). We find two maxima at low P separated by a minimum. At high-T the maxima are broader and weaker than those at low-T. As discussed in Ref. 49, the maxima at high T are related to maxima in fluctuations of the HB number NHB, while the maxima at low T are a consequence of maxima in fluctuations of the number Ncoop of cooperative HBs. The lines of strong maxima at constant P and constant T, respectively

is the Hamiltonian as defined in the Methods section, 〈ΔH2〉 is the enthalpy fluctuations (Fig. 4). We find two maxima at low P separated by a minimum. At high-T the maxima are broader and weaker than those at low-T. As discussed in Ref. 49, the maxima at high T are related to maxima in fluctuations of the HB number NHB, while the maxima at low T are a consequence of maxima in fluctuations of the number Ncoop of cooperative HBs. The lines of strong maxima at constant P and constant T, respectively  and

and  , overlap for all the considered pressures, and both maxima are more pronounced in the range

, overlap for all the considered pressures, and both maxima are more pronounced in the range  and

and  . The weak maxima

. The weak maxima  and

and  increase approaching the LL spinodal and have their larger maxima at the state point where they converge to the strong maxima, consistent with the occurrence of a critical point for a finite system (Fig. 4). The lines of weak maxima overlap for all positive pressures, branching off at negative pressures. At negative pressures, the locus

increase approaching the LL spinodal and have their larger maxima at the state point where they converge to the strong maxima, consistent with the occurrence of a critical point for a finite system (Fig. 4). The lines of weak maxima overlap for all positive pressures, branching off at negative pressures. At negative pressures, the locus  bends toward the turning point of the TMD line, as discussed in Methods section and in Ref. 53. Indeed, according to the relation

bends toward the turning point of the TMD line, as discussed in Methods section and in Ref. 53. Indeed, according to the relation

|

in case of intersection between the locus of extrema (∂CP/∂P)T = 0 and the TMD line, it results that (∂P/∂T)TMD = 0. Note that, as we explain in the Methods section, the relation (2) does not imply any change in the slope of the TminD line at the intersection with the locus of (∂CP/∂P)T = 0.

Figure 4.

(a) Loci of strong maxima ( ) and weak maxima (

) and weak maxima ( in the inset) along isobars for CP. (b) Loci of strong maxima (

in the inset) along isobars for CP. (b) Loci of strong maxima ( ) and weak maxima (

) and weak maxima ( in the inset) along isotherms. (c) Projection of CP maxima in T − P plane. The large circle with A identifies the region where CP shows the strongest maximum. Symbols not explained here are as in Fig. 2.

in the inset) along isotherms. (c) Projection of CP maxima in T − P plane. The large circle with A identifies the region where CP shows the strongest maximum. Symbols not explained here are as in Fig. 2.

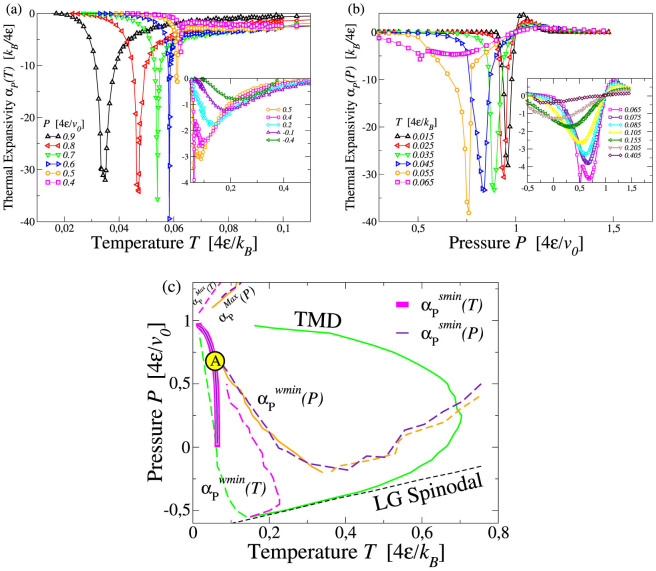

We calculate also the thermal expansivity αP ≡ (1/〈V〉) (∂〈V〉/∂T)P along isotherms and isobars (Fig. 5). As for the other response functions, we find two loci of strong extrema, minima in this case,  and

and  , along isotherms and isobars, respectively showing a divergent behavior in the same region where we find the strong maxima of KT and CP. From this region two loci of weaker minima depart. We find that the locus of weak minima along isobars

, along isotherms and isobars, respectively showing a divergent behavior in the same region where we find the strong maxima of KT and CP. From this region two loci of weaker minima depart. We find that the locus of weak minima along isobars  bends toward the turning point of the TMD. Although our calculations for αP do not allow us to observe the crossing with the TMD line, based on the relation (see Methods)

bends toward the turning point of the TMD. Although our calculations for αP do not allow us to observe the crossing with the TMD line, based on the relation (see Methods)

|

that holds at the TMD line, we can conclude that  should have zero T-derivative if it crosses the point where the TMD turns into the TminD line, because in this point the TMD slope approaches zero.

should have zero T-derivative if it crosses the point where the TMD turns into the TminD line, because in this point the TMD slope approaches zero.

Figure 5.

(a) Loci of strong minima of ( ) and weak minima (

) and weak minima ( in the inset) along isobars for αP. (b) Loci of strong minima (

in the inset) along isobars for αP. (b) Loci of strong minima ( ) and weak extrema (

) and weak extrema ( and

and  in the inset) along isotherms. (c) Projection of αP extrema in T − P plane. Orange lines are the loci of weaker extrema

in the inset) along isotherms. (c) Projection of αP extrema in T − P plane. Orange lines are the loci of weaker extrema  and

and  . The large circle with A identifies the region where the divergent minimum in αP is observed. Symbols not explained here are as in Fig. 2.

. The large circle with A identifies the region where the divergent minimum in αP is observed. Symbols not explained here are as in Fig. 2.

The locus of weaker minima along isotherms  , merges with the locus of maxima

, merges with the locus of maxima  at the state point where the slope of both loci is ∂P/∂T → ∞ (not shown in Fig. 5). According to the thermodynamic relation, discussed in Methods section,

at the state point where the slope of both loci is ∂P/∂T → ∞ (not shown in Fig. 5). According to the thermodynamic relation, discussed in Methods section,

|

we find that the locus of extrema in thermal expansivity along isotherms coincides, within the error bars, with the locus of extrema of isothermal compressibility along isobars (Fig. 5c).

All the loci of extrema of response functions that converge toward the same region A in Fig. 3, 4 and 5 increase in their absolute values. Because the increase of response functions is related to the increase of fluctuations and this is, in turn, related to the increase of correlation length ξ, to estimate ξ we calculate the spatial correlation function

|

where  is the position of the molecule i,

is the position of the molecule i,  the distance between molecule i and molecule l and 〈·〉 the thermodynamic average. The states of the water molecule, as well as the density ρ, the energy E and the entropy S of the system, are completely described by the bonding variables σij. Therefore, the function G(r) accounts for the fluctuations in ρ, E and S and allows us to evaluate the correlation length because the order parameter of the LLPT, as we discuss in the following, is related to a linear combination of ρ and E. Note that, instead, the density-density correlation function would give only an approximate estimate of ξ.

the distance between molecule i and molecule l and 〈·〉 the thermodynamic average. The states of the water molecule, as well as the density ρ, the energy E and the entropy S of the system, are completely described by the bonding variables σij. Therefore, the function G(r) accounts for the fluctuations in ρ, E and S and allows us to evaluate the correlation length because the order parameter of the LLPT, as we discuss in the following, is related to a linear combination of ρ and E. Note that, instead, the density-density correlation function would give only an approximate estimate of ξ.

We observe an exponential decay of G(r) ~ e−r/ξ at high temperatures in a broad range of pressures. Approaching the region A, the correlation function can be written as G(r) ~ e−r/ξ/rd−2+η where d is the dimension of the system and η a (critical) positive exponent. When ξ is of the order of the system size, the exponential factor approaches a constant leaving the power-law as the dominant contribution for the decay.

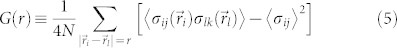

At P below the region A, we find that ξ has a maximum, ξMax, along isobars and that ξMax increases approaching A (Fig. 6). The ξMax locus coincides with the locus of strong extrema of CP, KT and αP (Fig. 6b). We observe that this common locus converges to A and that all the extrema increase approaching A. This behavior is consistent with the identification of A with the critical region of the LLCP. Furthermore, we identify the common locus with the Widom line that, by definition, is the ξMax locus departing from the LLCP in the one-phase region54,55. Our calculations allow us to locate the Widom line at any P down to the liquid-to-gas spinodal.

Figure 6.

(a) The correlation length ξ along isobars for N = 104 water molecules has maxima that increase for P approaching the critical region A. (b) The locus of ξ maxima coincides with the loci of strong extrema of KT, CP and αP. The Widom line is by definition the locus of ξ maxima at high T departing from the LLCP, that we locate within the critical region A, as discussed in the text.

At P above the region A, we find the continuation of the ξMax line, but with maxima that decrease for increasing P, as expected at the LL spinodal that ends in the LLCP (Fig. 6). Therefore, we identify the high-P part of the ξMax locus with the LL spinodal. Along this line the density, the energy and the entropy of the liquid are discontinuous, as discussed in previous works31,40,44,45,46,47,48,49.

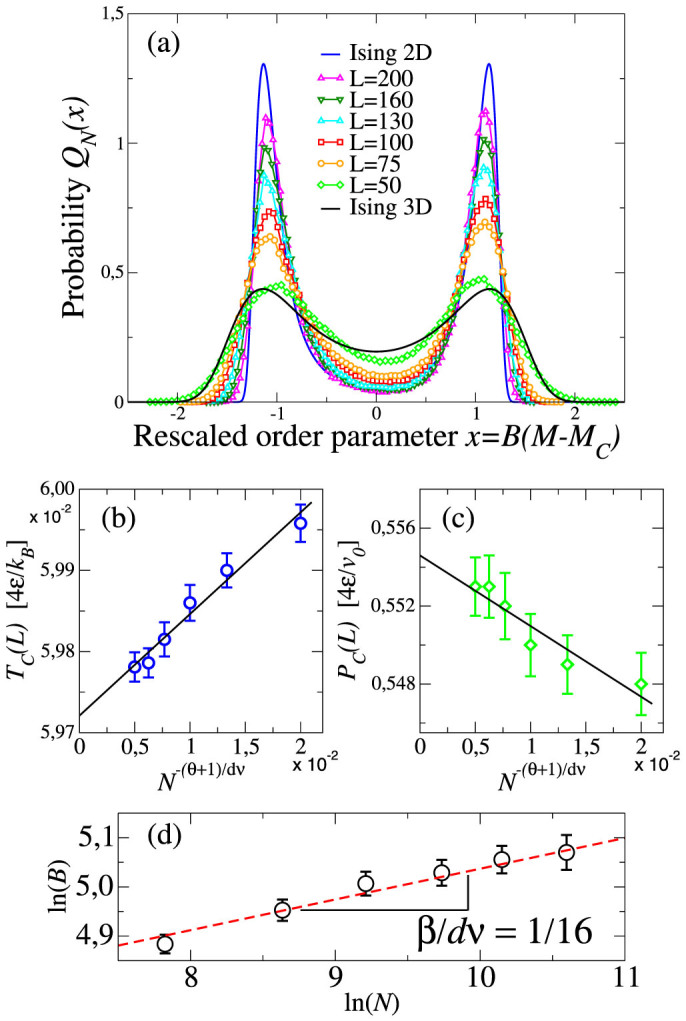

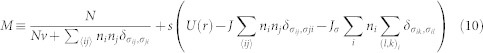

To better locate and characterize the LLCP in A we need to define the correct order parameter (o.p.) describing the LLPT. According to mixed-field finite-size scaling theory56, a density-driven fluid-fluid phase transition is described by an o.p. M ≡ ρ* + su*, where ρ* = ρv0 represents the leading term (number density),  is the energy density (both quantities are dimensionless) and s is the mixed-field parameter. Such linear combination is necessary in order to get the right symmetry of the o.p. distribution QN(M) at the critical point where

is the energy density (both quantities are dimensionless) and s is the mixed-field parameter. Such linear combination is necessary in order to get the right symmetry of the o.p. distribution QN(M) at the critical point where  . Here is x ≡ B(M − Mc),

. Here is x ≡ B(M − Mc),  , β is the critical exponent that governs M, ν is the critical exponent that governs ξ, with ν and β defined by the universality class, aM is a non-universal system-dependent parameter and

, β is the critical exponent that governs M, ν is the critical exponent that governs ξ, with ν and β defined by the universality class, aM is a non-universal system-dependent parameter and  is an universal function characteristic of the Ising fixed–point in d dimensions. We adjust B and Mc so that QN(M) has zero mean and unit variance.

is an universal function characteristic of the Ising fixed–point in d dimensions. We adjust B and Mc so that QN(M) has zero mean and unit variance.

We combine, using the multiple histogram reweighting method57 described in the Methods section, a set of 3 × 104 MC independent configurations for ~ 300 state points with  and

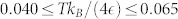

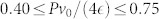

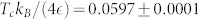

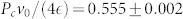

and  . We verify, by tuning s, T and P, that there is a point within the region A where the calculated QN(x) has a symmetric shape with respect to x = 0 (Fig. 7). We find s = 0.25 ± 0.03 for our range of N. The resulting critical parameters Tc(N), Pc(N) and the normalization factor B(N) follow the expected finite-size behaviors with 2D Ising critical exponents56. From the finite-size analysis we extract the asymptotic values

. We verify, by tuning s, T and P, that there is a point within the region A where the calculated QN(x) has a symmetric shape with respect to x = 0 (Fig. 7). We find s = 0.25 ± 0.03 for our range of N. The resulting critical parameters Tc(N), Pc(N) and the normalization factor B(N) follow the expected finite-size behaviors with 2D Ising critical exponents56. From the finite-size analysis we extract the asymptotic values  and

and  .

.

Figure 7.

(a) The size-dependent probability distribution QN for the rescaled o.p. x, calculated for Tc(N), Pc(N) and B(N), has a symmetric shape that approaches continuously (from N = 2500, symbols at the top at x = 0, to N = 40000, symbols at the bottom) the limiting form for the 2D Ising universality class (full blue line) and differs from the 3D Ising universality class case (full black line). Error bars are smaller than the symbols size. (b) The size-dependent LLCP temperature Tc(N) and (c) pressure Pc(N) (symbols), resulting from our best-fit of QN, extrapolate to  and

and  , respectively, following the expected linear behaviors (lines). (d) The normalization factor B(N) (symbols) follows the power law function (dashed line) ∝ Nβ/dν. We use the d = 2 Ising critical exponents: θ = 2 (correction to scaling), ν = 1 and β = 1/8 (both defined in the text).

, respectively, following the expected linear behaviors (lines). (d) The normalization factor B(N) (symbols) follows the power law function (dashed line) ∝ Nβ/dν. We use the d = 2 Ising critical exponents: θ = 2 (correction to scaling), ν = 1 and β = 1/8 (both defined in the text).

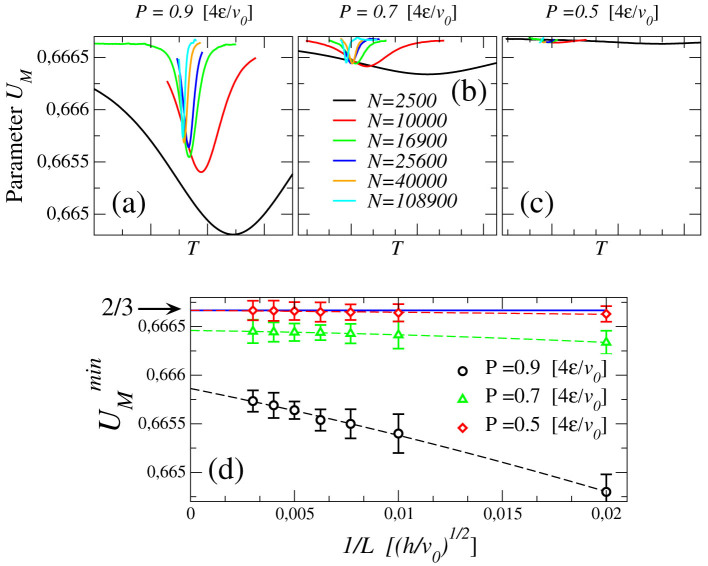

The presence of a first order phase transition ending in a critical point, associated to the o.p. M, is confirmed by the finite size analysis of the Challa-Landau-Binder parameter58 of M

|

where the symbol 〈·〉N refers to the thermodynamic average for a system with N water molecules. UM quantifies the bimodality in QN(M). The isobaric value of UM shows a minimum at the temperature where QN(M) mostly deviates with respect to a symmetric distribution (Fig. 8). Minimum of UM converges to 2/3 in the thermodynamic limit away from a first order phase transition, while it approaches to a value <2/3 where the bimodality of QN(M) indicates the presence of phase coexistence.

Figure 8. Challa-Landau-Binder parameter UM (defined in the text) of the o.p.

M for different system sizes, calculated for three pressures: (a)  , (b)

, (b)  , and (c)

, and (c)  slightly below

slightly below  . The curves are calculated with the histogram reweighting method. (d) Scaling of the minima of UM for different P. The arrow points to value 2/3 corresponding to the absence of a first-order phase transition in the thermodynamic limit. Error bars are calculated propagating the statistical error from histogram reweighting method.

. The curves are calculated with the histogram reweighting method. (d) Scaling of the minima of UM for different P. The arrow points to value 2/3 corresponding to the absence of a first-order phase transition in the thermodynamic limit. Error bars are calculated propagating the statistical error from histogram reweighting method.

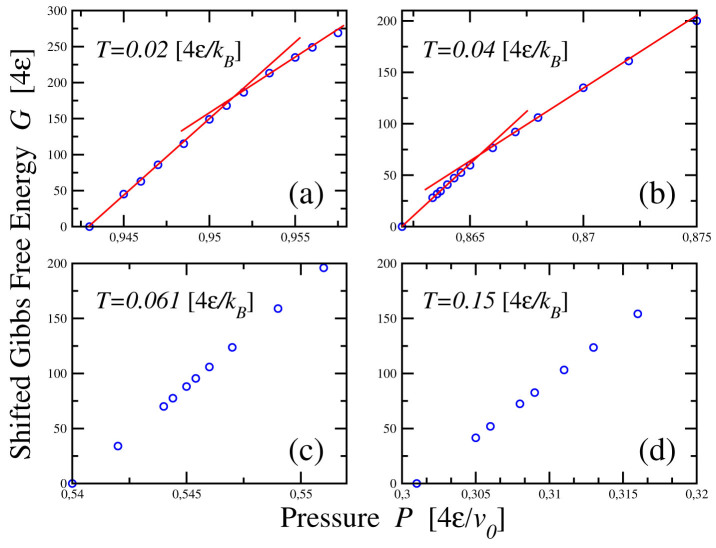

These results are consistent with the behavior of the Gibbs free energy G calculated with the histogram reweighting method (Fig. 9). In particular, we calculate G along isotherms, for P crossing the LLPT and the loci of weak maxima in KT(T) and CP(P). We find that the behavior of G for T < Tc is consistent with the occurrence of a discontinuity in volume V = ∂G/∂P, in the thermodynamic limit, with a decrease of V corresponding to the transition from LDL to HDL for increasing P. Crossing the loci  the volume decreases with pressure without any discontinuity as expected in the one-phase region.

the volume decreases with pressure without any discontinuity as expected in the one-phase region.

Figure 9. Gibbs free energy G along isotherms, as function of P. Points are shifted so that G = 0 at the lowest P. Lines are guides for the eyes.

(a) For  there is a discontinuity in the P-derivative of G at

there is a discontinuity in the P-derivative of G at  as expected at the LLPT, consistent with the behavior of the response functions at this state point (e.g., in Fig. 3b, 4b). (b) For

as expected at the LLPT, consistent with the behavior of the response functions at this state point (e.g., in Fig. 3b, 4b). (b) For  we observe the discontinuity in the P-derivative at

we observe the discontinuity in the P-derivative at  , again consistent with the LLPT. The LDL has a lower chemical potential (μ ≡ G/N) than the HDL, μLDL < μHDL, due to the HB energy gain in the LDL. For

, again consistent with the LLPT. The LDL has a lower chemical potential (μ ≡ G/N) than the HDL, μLDL < μHDL, due to the HB energy gain in the LDL. For  (c) and for

(c) and for  (d), both larger than Tc, we instead do not observe any discontinuity in the P-derivative of G by crossing the locus of

(d), both larger than Tc, we instead do not observe any discontinuity in the P-derivative of G by crossing the locus of  and the locus of

and the locus of  , respectively, as expected in the one-phase region.

, respectively, as expected in the one-phase region.

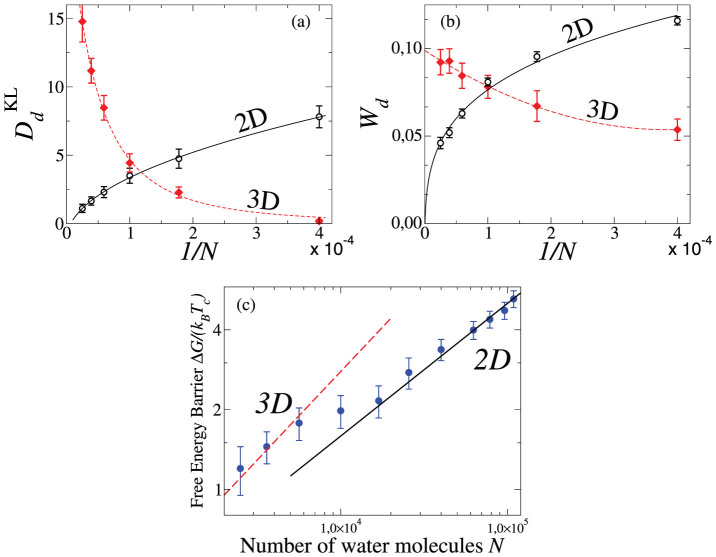

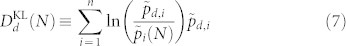

The distribution QN(N) adjust well to the data only for large N. We, therefore, perform a more systematic analysis. For each N, we quantify the deviation of the calculated  from the expected

from the expected  for the 2D Ising. Furthermore, due to the behavior of data for small N (Fig. 7a), we calculate the deviation from the 3D Ising

for the 2D Ising. Furthermore, due to the behavior of data for small N (Fig. 7a), we calculate the deviation from the 3D Ising  56. We estimate the Kullback-Leibler divergence51,59,

56. We estimate the Kullback-Leibler divergence51,59,

|

of the probability distribution  of xi from the theoretical value

of xi from the theoretical value  of xi (i = 1, …, n) in d dimensions (Fig. 10a), and the Liu et al. deviation51,

of xi (i = 1, …, n) in d dimensions (Fig. 10a), and the Liu et al. deviation51,

|

with  difference between the distribution peak and its value at x = 0 (Fig. 10b).

difference between the distribution peak and its value at x = 0 (Fig. 10b).

Figure 10.

(a) Kullback-Leibler divergence  and (b) Liu et al. deviations Wd of the calculated

and (b) Liu et al. deviations Wd of the calculated  from the Ising universal function

from the Ising universal function  in d = 2 (open symbols) and d = 3 (closed symbols), as a function of 1/N, with N water molecules, at constant

in d = 2 (open symbols) and d = 3 (closed symbols), as a function of 1/N, with N water molecules, at constant  . In both panels lines are power-law fits and we observe a crossover between 2D and 3D behavior at

. In both panels lines are power-law fits and we observe a crossover between 2D and 3D behavior at  . (c) The free-energy cost to form an interface between the two liquids coexisting at the LLCP scales as

. (c) The free-energy cost to form an interface between the two liquids coexisting at the LLCP scales as  with d = 3 for N < 104 and d = 2 for N > 104.

with d = 3 for N < 104 and d = 2 for N > 104.

We confirm  for

for  and find s = 0.10 ± 0.02 for

and find s = 0.10 ± 0.02 for  for our range of N. For both

for our range of N. For both  and Wd, with d = 2 and d = 3, we find minima at

and Wd, with d = 2 and d = 3, we find minima at  and

and  that become stronger for increasing N. We find that

that become stronger for increasing N. We find that  and W2 decrease with increasing N, vanishing for N → ∞ (Fig. 10). Therefore, for an infinite monolayer between hydrophobic walls separated by h ≈ 0.5 nm, the system has a LLCP that belongs to the 2D Ising universality class, as expected from our representation of the system as the 2D projection of the monolayer.

and W2 decrease with increasing N, vanishing for N → ∞ (Fig. 10). Therefore, for an infinite monolayer between hydrophobic walls separated by h ≈ 0.5 nm, the system has a LLCP that belongs to the 2D Ising universality class, as expected from our representation of the system as the 2D projection of the monolayer.

However, by increasing the confinement, i.e. reducing N and L at constant ρ,  and W2 become larger than

and W2 become larger than  and W3, respectively. Therefore, the calculated

and W3, respectively. Therefore, the calculated  deviates from the 3D probability distribution less than from the 2D probability distribution. For N = 2500 we find that both

deviates from the 3D probability distribution less than from the 2D probability distribution. For N = 2500 we find that both  and W3 have values approximately equal to those for

and W3 have values approximately equal to those for  and W2 calculated for a system ten times larger. In particular we find

and W2 calculated for a system ten times larger. In particular we find  for N = 2500. Hence, by increasing the confinement of the monolayer at constant ρ, the LLCP has a behavior that approximates better the bulk25,26,27,28,29,30,38, with a crossover between 2D and 3D-behavior occurring at

for N = 2500. Hence, by increasing the confinement of the monolayer at constant ρ, the LLCP has a behavior that approximates better the bulk25,26,27,28,29,30,38, with a crossover between 2D and 3D-behavior occurring at  .

.

This dimensional crossover is confirmed by the finite-size analysis of the Gibbs free energy cost ΔG/(kBTc) to form an interface between the two liquids in the vicinity of the LLCP, calculated as  , where

, where  and

and  are the minimum and maximum values of the probability distribution

are the minimum and maximum values of the probability distribution  of configurations of N water molecules with energy

of configurations of N water molecules with energy  and volume V at the LLCP. This quantity is expected to scale as

and volume V at the LLCP. This quantity is expected to scale as  . We find that our data can be fitted as

. We find that our data can be fitted as  for small sizes and as

for small sizes and as  for large sizes with a crossover around N = 104 (Fig. 10c). Considering the value of the estimated ρc in real units (

for large sizes with a crossover around N = 104 (Fig. 10c). Considering the value of the estimated ρc in real units ( )45, the corresponding crossover wall-size is

)45, the corresponding crossover wall-size is  .

.

Discussion

Our rationale for this dimensional crossover at fixed h is that, when L/h decreases toward 1, the characteristic way the critical fluctuations spread over the system, i.e. the universality class of the LLCP, resembles closely the bulk because the asymmetry among the three spatial dimensions is reduced. A similar result was found recently by Liu et al. for the gas-liquid critical point of a Lennard-Jones (LJ) system confined between walls by fixing L and varying h51. However, in the case considered by Liu et al. the crossover was expected because the number of layers of particles was increased from one to several, making the system more similar to the isotropic 3D case. Here, instead, we consider always one single layer, changing the proportion L/h by varying L. Therefore, it could be expected that the system belongs to the 2D universality class for any L.

Furthermore, the extrapolation of the results for the LJ liquid to our case of a monolayer with  , where r0 is the water van der Waals diameter, would predict a dimensional crossover at

, where r0 is the water van der Waals diameter, would predict a dimensional crossover at  51. Here, instead, we find the crossover at

51. Here, instead, we find the crossover at  , i.e. one order of magnitude larger than the LJ case. We ascribe this enhancement of the crossover to (i) the presence of a cooperative HB network and (ii) the low coordination number that water has in both the monolayer and the bulk. These are the main differences between water and a LJ fluid. The cooperativity intensifies drastically the spreading of the critical fluctuations along a network, contributing to the effective dimensionality increase of the confined monolayer. Moreover, the HB network has in 3D a coordination number (z = 4) as low as in 2D, making the first coordination shell similar in both dimensions.

, i.e. one order of magnitude larger than the LJ case. We ascribe this enhancement of the crossover to (i) the presence of a cooperative HB network and (ii) the low coordination number that water has in both the monolayer and the bulk. These are the main differences between water and a LJ fluid. The cooperativity intensifies drastically the spreading of the critical fluctuations along a network, contributing to the effective dimensionality increase of the confined monolayer. Moreover, the HB network has in 3D a coordination number (z = 4) as low as in 2D, making the first coordination shell similar in both dimensions.

Our findings are consistent with recent atomistic simulations of water nanoconfined between surfaces.60,61,62. Zhang et al. found that water dipolar fluctuations are enhanced in the direction parallel to the confining surfaces (hydrophobic graphene sheets) within a distance of 0.5 nm60. Ballenegger and Hansen found similar results for confined polar fluids, including water, within ≈ 0.5 nm distance from the hydrophobic surface61. Bonthuis et al. extended these results to both hydrophilic and hydrophobic confining surfaces. All these findings are consistent with our result showing the enhancement of the fluctuations of the o.p. in the direction parallel to the confining walls separated by h ≈ 0.5 nm. Furthermore, Zhang et al. observed that the effect does not depend on the details of the water-surface interaction but stems from the very presence of interfaces60. This is confirmed by our study, where the water-interface interaction is purely due to excluded volume. Following the authors of Ref. 60, this observation allows us to relate our finding for rigid surfaces to experimental results for water hydrating membranes63, reporting new types of water dynamics in thin interfacial layers, and water nanoconfined in different types of reverse micelles64, showing that the water dynamics is governed by the presence of the interface rather than the details (e.g., the presence charged groups) of the interface.

In conclusion, we analyze the low-T phase diagram of a water monolayer confined between hydrophobic parallel walls of size L separated by h ≈ 0.5 nm. We study water fluctuations associated to the thermodynamic response functions and their relations to the loci of TMD, TminD. For each response function we find two loci of extrema, one stronger at lower-T and one weaker and broader at higher-T. These loci converge toward a critical region where the fluctuations diverge in the thermodynamic limit, defining the LLCP. We calculate the Widom line departing from the LLCP based on its definition as the locus of maxima of ξ and show that it coincides with the locus of strong maxima of the response functions. We find that the LLCP belongs to the 2D Ising universality class for L → ∞, with strong finite-size effects for small L. Surprisingly, the finite-size effects induce the LLCP universality class to converge toward the bulk case (3D Ising universality class) already for a system with a very pronounced plane asymmetry, i.e. a water monolayer of height h ≈ 0.5 nm and L/h ≈ 50. For normal liquid, instead, this is expected only for much smaller relative values of L (L/h ≤ 5). We rationalize this result as a consequence of two properties of the HB network: (i) its high cooperativity, that enhances the fluctuations, and (ii) its low coordination number, that makes the first coordination shell for the monolayer and the bulk similar.

Methods

The model

We consider a monolayer formed by N water molecules confined in a volume V ≡ hL2 between two hydrophobic flat surfaces separated by a distance h, with  , where v0 is the water excluded volume. Each water molecule has four next-neighbours7. We partition the volume into N equivalent cells of height

, where v0 is the water excluded volume. Each water molecule has four next-neighbours7. We partition the volume into N equivalent cells of height  and square section with size

and square section with size  , equal to the average distance between water molecules. By coarse-graining the molecules distance from the surfaces, we reduce our monolayer representation to a 2D system. We use periodic boundary conditions parallel to the walls to reduce finite-size effects. We simulate constant N, P, T, allowing V(T, P) to change, with each cell i = 1, …, N having number density

, equal to the average distance between water molecules. By coarse-graining the molecules distance from the surfaces, we reduce our monolayer representation to a 2D system. We use periodic boundary conditions parallel to the walls to reduce finite-size effects. We simulate constant N, P, T, allowing V(T, P) to change, with each cell i = 1, …, N having number density  . To each cell we associate a variable ni = 0 (ni = 1) depending if the cell i has ρi/ρ0 ≤ 0.5 (ρi/ρ0 > 0.5). Hence, ni is a discretized density field replacing the water translational degrees of freedom. The water-water interaction is given by

. To each cell we associate a variable ni = 0 (ni = 1) depending if the cell i has ρi/ρ0 ≤ 0.5 (ρi/ρ0 > 0.5). Hence, ni is a discretized density field replacing the water translational degrees of freedom. The water-water interaction is given by

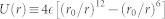

|

The first term, summed over all the water molecules i and j at O–O distance rij, has U(r) ≡ ∞ for  (water van der Waals diameter),

(water van der Waals diameter),  for r ≥ r0 with

for r ≥ r0 with  , and U(r) ≡ 0 for r > rc ≡ 25r0 (cutoff).

, and U(r) ≡ 0 for r > rc ≡ 25r0 (cutoff).

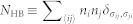

The second term represents the directional (covalent) component of the hydrogen bond (HB), with  ,

,  number of HBs, with the sum over n.n., where σij = 1, …, q is the bonding index of molecule i to the n.n. molecule j, with δab = 1 if a = b, 0 otherwise. Each water molecule can form up to four HBs. We adopt a geometrical definition of the HB, based on the

number of HBs, with the sum over n.n., where σij = 1, …, q is the bonding index of molecule i to the n.n. molecule j, with δab = 1 if a = b, 0 otherwise. Each water molecule can form up to four HBs. We adopt a geometrical definition of the HB, based on the  angle and the OH—O distance. A HB breaks if

angle and the OH—O distance. A HB breaks if  . Hence, only 1/6 of the entire range of values [0, 360°] for the

. Hence, only 1/6 of the entire range of values [0, 360°] for the  angle is associated to a bonded state. Therefore, we choose q = 6 to account correctly for the entropy variation due to the HB formation and breaking. Moreover, a HB breaks when the OH—O distance > rmax − rOH = 3.14 Å, where rOH = 0.96 Å and rmax = 4.1 Å. The value of rmax is a consequence of our choice ni = 0 for ρi/ρ0 ≤ 0.5, i.e.

angle is associated to a bonded state. Therefore, we choose q = 6 to account correctly for the entropy variation due to the HB formation and breaking. Moreover, a HB breaks when the OH—O distance > rmax − rOH = 3.14 Å, where rOH = 0.96 Å and rmax = 4.1 Å. The value of rmax is a consequence of our choice ni = 0 for ρi/ρ0 ≤ 0.5, i.e.  , implying that ninj = 0 when

, implying that ninj = 0 when  Å ≡ rmax.

Å ≡ rmax.

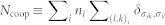

The third term of the Eq.(9) accounts for the HB cooperativity due to the quantum many-body interaction65, with  and

and  , where (l, k)i indicates each of the six different pairs of the four indices σij of a molecule i. The value

, where (l, k)i indicates each of the six different pairs of the four indices σij of a molecule i. The value  is chosen in such a way to guarantee an asymmetry between the two components of the HB interaction. To the cooperative term is due the O–O–O correlation that locally leads the molecules toward an ordered configuration. In bulk water this term would lead to a tetrahedral structure at low P up to the second shell, as observed in the experiments66. An increase of T or P partially disrupts the HB network and induces a more compact local structure, with smaller average volume per molecule. Therefore, for each HB we include an enthalpy increase PvHB, where vHB/v0 = 0.5 is the average volume increase between high-ρ ices VI and VIII and low-ρ (tetrahedral) ice Ih. Hence, the total volume is V ≡ V0 + NHBvHB, where V0 ≥ Nv0 is a stochastic continuous variable changing with Monte Carlo (MC) acceptance rule46. Because the HBs do not affect the n.n. distance66, we ignore their negligible effect on the U(r) term. Finally, we model the water-wall interaction by excluded volume.

is chosen in such a way to guarantee an asymmetry between the two components of the HB interaction. To the cooperative term is due the O–O–O correlation that locally leads the molecules toward an ordered configuration. In bulk water this term would lead to a tetrahedral structure at low P up to the second shell, as observed in the experiments66. An increase of T or P partially disrupts the HB network and induces a more compact local structure, with smaller average volume per molecule. Therefore, for each HB we include an enthalpy increase PvHB, where vHB/v0 = 0.5 is the average volume increase between high-ρ ices VI and VIII and low-ρ (tetrahedral) ice Ih. Hence, the total volume is V ≡ V0 + NHBvHB, where V0 ≥ Nv0 is a stochastic continuous variable changing with Monte Carlo (MC) acceptance rule46. Because the HBs do not affect the n.n. distance66, we ignore their negligible effect on the U(r) term. Finally, we model the water-wall interaction by excluded volume.

The observables

The LLCP is identified by the mixed-field order parameter M and not by the magnetization of the Potts variables σi,j as in normal Potts model. M is related to the configuration of the system by the relation

|

where v ≡ V0/N and s is the mixed-field parameter. M is therefore a linear combination of density and energy.

Thermodynamic response functions are calculated from

|

and

|

as long as the volume and energy distributions are not clearly bimodal, i.e. excluding the values of T and P where the phase coexistence is observed, based on the definition of M. Here  , for

, for  and, H is the enthalpy of the system.

and, H is the enthalpy of the system.

The Monte Carlo method

The system is equilibrated via Monte Carlo simulation with Wolff algorithm46, following an annealing procedure: starting with random initial condition at high T, the temperature is slowly decreased and the system is re-equilibrated and sampled with 104 ÷ 105 independent configurations for each state point. The thermodynamic equilibrium is checked probing that the fluctuation-dissipation relations, Eq. (11) and (12), hold within the error bar.

The histogram reweighting method

The probability QN(M) is calculated in a continuous range of T and P across the ξMax line. We consider an initial set of m ∈ [10:20] independent simulations within a temperature range  and a pressure range

and a pressure range  . For each simulation i = 1, …, m we calculate the histograms hi(u, ρ) in the energy density–density plane. The histograms hi(u, ρ) provide an estimate of the equilibrium probability distribution for u and ρ; this estimate becomes correct in the thermodynamic limit. For the NPT ensemble, the new histogram h(u, ρ, P′, β′) for new values of β′ = 1/kBT′ and P′ close the simulated ones, is given by the relation57

. For each simulation i = 1, …, m we calculate the histograms hi(u, ρ) in the energy density–density plane. The histograms hi(u, ρ) provide an estimate of the equilibrium probability distribution for u and ρ; this estimate becomes correct in the thermodynamic limit. For the NPT ensemble, the new histogram h(u, ρ, P′, β′) for new values of β′ = 1/kBT′ and P′ close the simulated ones, is given by the relation57

|

where Ni is the number of independent configurations of the run i. The constants Ci, related to the Gibbs free energy value at Ti and Pi, are self-consistently calculated from the equation57

|

We choose as initial set of parameters Ci = 0. The parameters Ci are recursively calculated by means of Eq. (13) and (14) until the difference between the values at iteration k and k + 1 is less then the desired numerical resolution (10−3 in our calculations). Once the new histogram is calculated, QN(M) at Ti and Pi is calculated integrating h(u, ρ, Pi, βi) along a direction perpendicular to the line ρ + su.

Thermodynamic relations

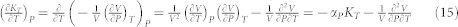

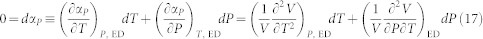

We report here the calculations for the thermodynamic relations in Eq. (1), (2), (3) and (4)39. To verify the relation (4) we calculate the derivative of KT along isobars

|

and the derivative of αP along isotherms

|

Following39,67 the line of extrema in density (TMD and TminD lines) is characterized by αP = 0, hence, dαP = 0 along the TMD line. Therefore,

|

where the index “ED” denotes that the derivatives are taken along the locus of extrema in density. So, the slope ∂P/∂T of TMD is given by

|

from which, using Eq. (15) with αP = 0, we get Eq. (1). The Eq. (18) holds as long as both (∂αP/∂P)T and (∂αP/∂T)P do not vanish contemporary, as it occurs along the Widom line, where the loci of strong minima of αP overlap. For this reason the intersection between the Widom line and TminD line does not imply any change in the slope (∂P/∂T)TminD.

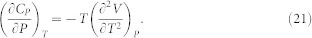

To calculate Eq. (2) we start from CP and αP written in terms of Gibbs free energy

|

from which results

|

|

Substituting in Eq. (18) we get the Eq. (2) at the TMD. Moreover, because of αP = 0 at the TMD line, from the last equivalence of Eq. (20) we get

|

from which, using Eq. (18), we get the Eq. (3).

Author Contributions

V.B. and G.F. designed the research. V.B. made the simulations. G.F. supervised the work. Both authors analyzed the data, prepared the figures, wrote the text and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Spanish MEC grant FIS2012-31025 and the EU FP7 grant NMP4-SL-2011-266737.

References

- Paul D. R. Creating New Types of Carbon-Based Membranes. Science 335, 413 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Density hysteresis of heavy water confined in a nanoporous silica matrix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12206 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper A. Density minimum in supercooled confined water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 47, E1192 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitby M. & Quirke N. Fluid flow in carbon nanotubes and nanopipes. Nat. Nanotechnol 2, 87 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S., Choi M. Y., Kumar P. & Stanley H. E. Phase transitions in confined water nanofilms. Nat. Phys. 6, 685–689 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Faraudo J. & Bresme F. Anomalous Dielectric Behavior of Water in Ionic Newton Black Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 236102 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangi R. & Mark A. E. Monolayer Ice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 025502 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima O. & Stanley H. E. The relationship between liquid, supercooled and glassy water. Nature 396, 329 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson A. et al. Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering of liquid water. J. Electron. Spectrosc. 188, 84–10 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Taschin A., Bartolini P., Eramo R., Righini R. & Torre R. Evidence of two distinct local structures of water from ambient to supercooled conditions. Nature Comm. 4, 2401 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole P. H., Sciortino F., Essmann U. & Stanley H. E. Phase-Behavior Of Metastable Water. Nature 360, 324 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Katayama Y. et al. A first-order liquid-liquid phase transition in phosphorus. Nature 403, 170 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama Y. et al. Macroscopic Separation of Dense Fluid Phase and Liquid Phase of Phosphorus. Science 306, 848 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaco G., Falconi S., Crichton W. A. & Mezouar M. Nature of the First-Order Phase Transition in Fluid Phosphorus at High Temperature and Pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 90, 255701 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Kurita R. & Mataki H. Liquid-Liquid Transition in the Molecular Liquid Triphenyl Phosphite. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 025701 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurita R. & Tanaka H. Critical-Like Phenomena Associated with Liquid-Liquid Transition in a Molecular Liquid. Science 306, 845 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves G. N. et al. Detection of First-Order Liquid/Liquid Phase Transitions in Yttrium Oxide-Aluminum Oxide Melts. Science 322, 566 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K.-i. & Tanaka H. Liquid–liquid transition without macroscopic phase separation in a waterglycerol mixture. Nature Mater. 11, 436 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H. Bond orientational order in liquids: Towards a unified description of water-like anomalies, liquid-liquid transition, glass transition, and crystallization - Bond orientational order in liquids. Eur. Phys. J. E 35, 113 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K-i. & Tanaka H. General nature of liquidliquid transition in aqueous organic solutions. Nature Comm. 4, 2844 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machon D., Meersman F., Wilding M. C., Wilson M. & McMillan P. F. Pressure-induced amorphization and polyamorphism: Inorganic and biochemical systems. Prog. Mater. Sci. 61, 216–282 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand C. E. & Anisimov M. A. Peculiar Thermodynamics of the Second Critical Point in Supercooled Water. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 14099 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holten V. & Anisimov M. A. Entropy-driven liquid-liquid separation in supercooled water. Sci. Rep. 2, 713 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson A., Huang C. & Pettersson L. G. M. Fluctuations in ambient water. J. Mol. Liq. 176, 2–16 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H. A self-consistent phase diagram for supercooled water. Nature 380, 328 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Abascal J. L. F. & Vega C. Widom line and the liquid-liquid critical point for the TIP4P/2005 water model. J. Chem. Phys. 133, 234502 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciortino F., Saika-Voivod I. & Poole P. H. Study of the ST2 model of water close to the liquid-liquid critical point. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 19759 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring T., Franzese G., Buldyrev S., Herrmann H. & Stanley H. E. Nanoscale Dynamics of Phase Flipping in Water near its Hypothesized Liquid-Liquid Critical Point. Sci. Rep. 2, 474 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring T. A. et al. Finite-size scaling investigation of the liquid-liquid critical point in ST2 water and its stability with respect to crystallization. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 244506 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole P. H., Bowles R. K., Saika-Voivod I. & Sciortino F. Free energy surface of ST2 water near the liquid-liquid phase transition. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 034505 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese G., Marques M. I. & Stanley H. E. Intramolecular coupling as a mechanism for a liquid-liquid phase transition. Phys. Rev. E 67, 011103 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese G., Malescio G., Skibinsky A., Buldyrev S. V. & Stanley H. E. Generic mechanism for generating a liquid-liquid phase transition. Nature 409, 692 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry S. & Angell C. A. Liquid-liquid phase transition in supercooled silicon. Nature Mater. 2, 739 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scandolo S. Liquid–liquid phase transition in compressed hydrogen from first-principles simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3051 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh P. & Widom M. Liquid-Liquid Transition in Supercooled Silicon Determined by First-Principles Simulation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 075701 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilaseca P. & Franzese G. Isotropic soft-core potentials with two characteristic length scales and anomalous behaviour. J. Non-Cryst. Sol. 357, 419 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Gallo P. & Sciortino F. Ising Universality Class for the Liquid-Liquid Critical Point of a One Component Fluid: A Finite-Size Scaling Test. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 77801 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Palmer J. C., Panagiotopoulos A. Z. & Debenedetti P. G. Liquid-liquid transition in ST2 water. J. Chem. Phys. 137, 214505 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastry S., Debenedetti P. G., Sciortino F. & Stanley H. E. Singularity-free interpretation of the thermodynamics of supercooled water. Phys. Rev. E 53, 6144 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokely K., Mazza M. G., Stanley H. E. & Franzese G. Effect of hydrogen bond cooperativity on the behavior of water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1301 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limmer D. T. & Chandler D. The putative liquid–liquid transition is a liquid–solid transition in atomistic models of water. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 134503 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer J. C., Car R. & Debenedetti P. G. The Liquid-Liquid Transition in Supercooled ST2 Water: a Comparison Between Umbrella Sampling and Well-Tempered Metadynamics. Faraday Discuss. 167, (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo P. & Rovere M. Special section on water at interfaces. J. Phys.: Cond. Matt. 22, 280301 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strekalova E. G., Mazza M. G., Stanley H. E. & Franzese G. Large Decrease of Fluctuations for Supercooled Water in Hydrophobic Nanoconfinement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 145701 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de los Santos F. & Franzese G. Understanding Diffusion and Density Anomaly in a Coarse-Grained Model for Water Confined between Hydrophobic Walls. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 14311 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza M. G., Stokely K., Strekalova E. G., Stanley H. E. & Franzese G. Cluster Monte Carlo and numerical mean field analysis for the water liquid-liquid phase transition. Comp. Phys. Comm. 180, 497 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Franzese G., Bianco V. & Iskrov S. Water at Interface with Proteins. Food Biophys. 6, 186 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Bianco V., Iskrov S. & Franzese G. Understanding the role of hydrogen bonds in water dynamics and protein stability. J. Biol. Phys. 38, 27 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza M. G., Stokely K., Pagnotta S. E., Bruni F., Stanley H. E. & Franzese G. More than one dynamic crossover in protein hydration water. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 19873 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese G. & Bianco V. Water at Biological and Inorganic Interfaces. Food Biophys. 8, 153 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Panagiotopoulos A. Z. & Debenedetti P. G. Finite-size scaling study of the vaporliquid critical properties of confined fluids: Crossover from three dimensions to two dimensions. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 144107 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallamace F., Branca C., Broccio M., Corsaro C., Mou C.-Y. & Chen S.-H. The anomalous behavior of the density of water in the range 30 K ¡ T ¡ 373 K. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 18387 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole P. H., Saika-Voivod S. & Sciortino F. Density minimum and liquid-liquid phase transition. J. Phys.: Cond. Matt. 17, L431 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Xu L. et al. Relation between the Widom line and the dynamic crossover in systems with a liquid-liquid phase transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 46, 16558 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzese G. & Stanley H. E. The Widom line of supercooled water. J. Phys.: Cond. Matt. 20, 205126 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Wilding N. B. & Binder K. Finite-size scaling for near-critical continuum fluids at constant pressure. Phys. A 1, 439 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotopoulos A. Z. Monte Carlo methods for phase equilibria of fluids. J. Phys.: Cond. Matt. 12, R25 (2000) for a review. [Google Scholar]

- Franzese G. & Coniglio A. Phase transitions in the Potts spin-glass model. Phys. Rev. E 58, 2753 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Kullback S. & Leibler R. A. On Information and Sufficiency. Ann. Math. Statist. 22, 79–86 (1951). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C., Gygi F. & Galli G. Strongly Anisotropic Dielectric Relaxation of Water at the Nanoscale. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 2477–2481 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ballenegger V. & Hansen J.-P. Dielectric permittivity profiles of confined polar fluids. J. Chem. Phys. 122, 114711 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthuis D. J., Gekle S. & Netz R. R. Dielectric Profile of Interfacial Water and its Effect on Double-Layer Capacitance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 166102 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tielrooij K. J., Paparo D., Piatkowski L., Bakker H. J. & Bonn M. Dielectric Relaxation Dynamics of Water in Model Membranes Probed by Terahertz Spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 97, 2484–2492 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen D. E., Levinger N. E., Spry D. B. & Fayer M. D. Confinement or the Nature of the Interface? Dynamics of Nanoscopic Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 14311–14318 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández de la Peña L. & Kusalik P. G. Temperature Dependence of Quantum Effects in Liquid Water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 5246 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper A. K. & Ricci M. A. Structures of high-density and low-density water. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2881 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo L. P. N., Debenedetti P. G. & Sastry S. Singularity-free interpretation of the thermodynamics of supercooled water. II. Thermal and volumetric behavior. J. Chem. Phys. 109, 626 (1998). [Google Scholar]