Abstract

Utilization of heterosis has significantly increased rice yields. However, its mechanism remains unclear. In this study, comparative transcriptional profiles of three super-hybrid rice combinations, LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9, at the flowering and filling stages, were created using rice whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray. The LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9 hybrids yielded 1193, 1630 and 1046 differentially expressed genes (DGs), accounting for 3.2%, 4.4% and 2.8% of the total number of genes (36,926), respectively, after using the z-test (p < 0.01). Functional category analysis showed that the DGs in each hybrid combination were mainly classified into the carbohydrate metabolism and energy metabolism categories. Further analysis of the metabolic pathways showed that DGs were significantly enriched in the carbon fixation pathway (p < 0.01) for all three combinations. Over 80% of the DGs were located in rice quantitative trait loci (QTLs) of the Gramene database, of which more than 90% were located in the yield related QTLs in all three combinations, which suggested that there was a correlation between DGs and rice heterosis. Pathway Studio analysis showed the presence of DGs in the circadian regulatory network of all three hybrid combinations, which suggested that the circadian clock had a role in rice heterosis. Our results provide information that can help to elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying rice heterosis.

Keywords: rice, transcriptional profiling, heterosis, photosynthesis, circadian clock

1. Introduction

The superior performance of F1-hybrids over their parents is defined as heterosis/hybrid vigor. Heterosis has a significant role in improving crop productivity [1]. As a staple food crop, rice plays a vital role in feeding the growing population, and hybrid rice has contributed greatly to world-wide grain yields [2]. Rice is also a good model plant for studying heterosis, due to its small genome size, high collinearity with other Gramineae crops and abundant genomic data resources [3]. However, the molecular mechanism underlying heterosis in rice still remains elusive [4–6].

The traditional interpretation of heterosis can mainly be explained by three hypotheses: dominance hypothesis [7,8], over-dominance hypothesis [9,10] and epistasis [11]. All these hypotheses are not connected with molecular principles, and therefore, it is difficult to explain the molecular basis of heterosis [4,12]. Genetic dissection of quantitative trait variation indicated that multiple genes may be collectively responsible for the superior performance of F1-hybrids [13]. Meanwhile, a single heterozygous gene, SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS, was reported to cause hybrid vigor in hybrid tomato [14].

The superior performance of hybrids may result from the variations in expressed genes between F1-hybrids and their parents. Genome-wide gene expression analysis between hybrids and their parents has been performed extensively in rice [15–20], maize [21,22], wheat [23–25] and Arabidopsis [26], covering tissues, such as endosperm, roots and leaves, and various developmental stages. Several studies have found that a number of differentially expressed genes responsible for heterosis tend to be specific to different tissues and developmental stages [15,18,27,28] and that the genetic basis of heterosis is trait-dependent [29]. To date, there has been little consensus on this subject, as previous studies were performed separately with different samples, different strategies and different methods. In maize, there were attempts to study hybrid-parental gene expression among various hybrid combinations [30]. Most of these studies focused on one hybrid combination and provide few clues as to the molecular mechanism underlying different hybrid rice combinations.

Previously, we have investigated the transcriptional profile of super-hybrid rice and its parents by whole-genome oligonucleotide microarray [18] and by serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) [16]. Microarray analysis of the LYP9 hybrid combination revealed that significant numbers of DGs were enriched in the energy metabolism and transport categories. The research into transcriptional and physiological metabolic changes in the LY2186 hybrid combination showed that increased carbon fixation and photosynthetic capacity play roles in hybrid vigor. These results from one hybrid combination are insufficient to explain heterosis, so in this study, we performed comparative transcriptomic analyses on three high-yielding hybrid rice combinations, LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9, at the flowering (Fw) and filling (Fi) stages in an attempt to identify components of heterosis common amongst rice hybrids. The three hybrid combinations all had yield vigor, but there were differences in their trait components. LYP9 had a high grain number, and LY2163 and LY2186 had high grain setting rates and grain weights (China Rice Data Center) [31].

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Transcriptional Profiles of Three Super-Hybrid Rice Combinations

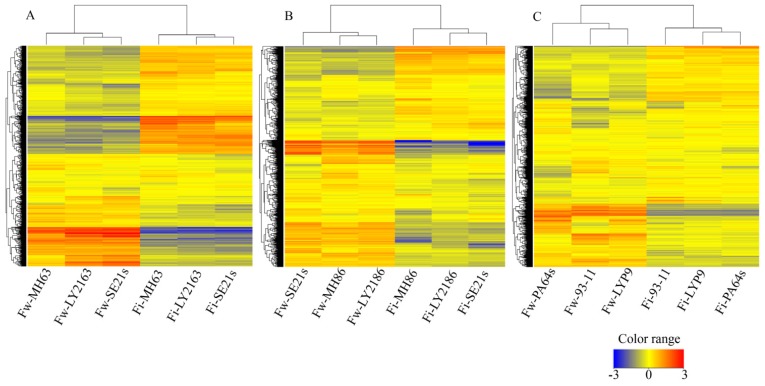

The gene expression profiles of flag leaves in three super-hybrid rice varieties, Liangyou-2163 (LY2163), Liangyou-2186 (LY2186) and Liangyoupeijiu (LYP9), and their parental lines (LY2163 = SE21s × Minghui63 (MH63), LY2186 = SE21s × Minghui86 (MH86) and LYP9 = PA64s × 93–11) were analyzed by rice whole-genome microarray. We detected 20,461 (LY2163 hybrid combination), 31,516 (LY2186 hybrid combination) and 19,950 (LYP9 hybrid combination) expressed genes from the flowering stage and 16,977 (LY2163 hybrid combination), 15,926 (LY2186 hybrid combination) and 14,373 (LYP9 hybrid combination) from the filling stage (Tables S1 and S2; Figure S1). Most of the expressed genes were shared by each hybrid combination. The identical genes accounted for 60.0%–73.5% of the expressed genes in each hybrid combination at the flowering stage and 75.6%–79.0% at the filling stage (Figure S1). Cluster analysis showed that the transcriptional profiles of the hybrids and their parents were different at each developmental stage and that similar expression patterns were observed among all three combinations at the same developmental stage (Figure 1). The expression patterns of all three hybrids were similar to their maternal parent at the filling stage. At the flowering stage, LY2163 showed a similar expression to the maternal parent, but LY2186 and LYP9 were the opposite and resembled the paternal parent (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clustering analysis of expressed genes among three hybrid combinations. Hierarchical clustering was done by GeneSpring 12.6 using normalized data. (A) LY2163 hybrid combination; (B) LY2186 hybrid combination; (C) LYP9 hybrid combination. Fw, flowering; Fi, filling.

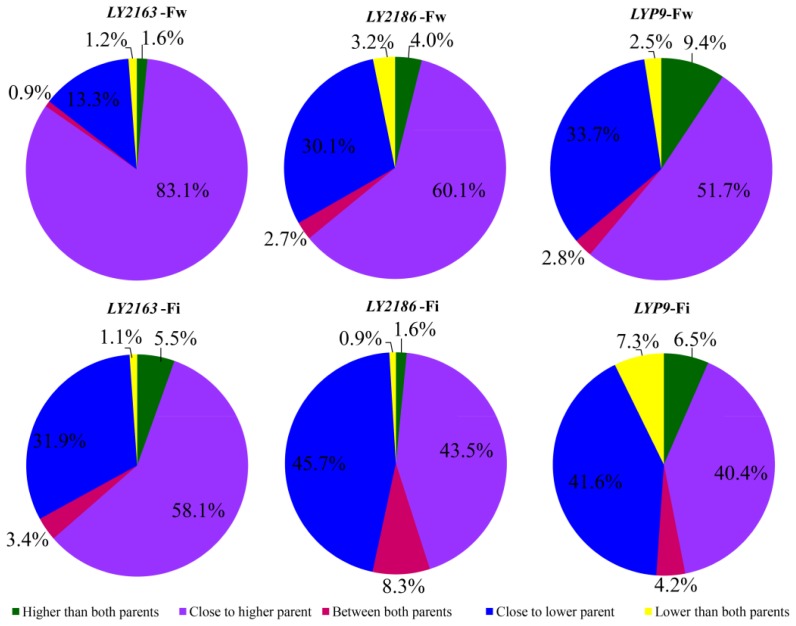

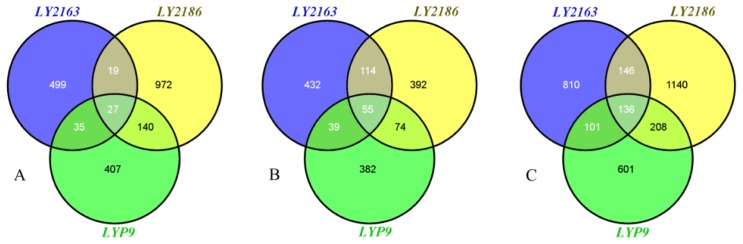

According to the statistical significance results for gene expression [18], we identified hundreds of differentially expressed genes (DGs) between the hybrid and its parents in each hybrid combination, unexpectedly, only a few DGs were shared by all three hybrid combinations (Figure 2A,B). To further find out how DG looks comparing to its two parents, the DGs of each hybrid combination at each stage were further classified into five expression patterns, higher than both parents (H2P), close to the higher parent (CHP), between both parents (B2P), close to the lower parent (CLP) and lower than both parents (L2P), based on the expression levels of these hybrid combinations. CHP and CLP made up the largest proportion and accounted for 82.0%–96.4% of the total DGs (Figure 3). The various gene expression patterns could result from the differential regulation of gene expression in the hybrid combinations [12,19].

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes (DGs) shared by three hybrid combinations. (A) DGs at the flowering (Fw) stage; (B) DGs at the filling (Fi) stage; (C) DGs at either the Fw or Fi stage.

Figure 3.

Pie graph representing expression patterns of DGs.

As it is known that the changed gene expression between hybrid and parents is one of the important factors determining the phenotypic variation, DGs at either stage/tissue should both be involved in contributing to heterosis, though it is hard to determine specifically which genes contributed directly. To make the comparison more comprehensive, we also pooled up DGs of both stages in each hybrid combination while comparing differentially expressed genes among different combinations and found 1193, 1630 and 1046 DGs for the LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9 hybrid combinations, respectively (Figure 2C). These union DGs accounted for 3.2%, 4.4% and 2.8%, respectively, of the 36,926 genes studied (Table 1; Tables S3–S8); however, only 136 DGs were shared by all three combinations, which accounted for 8.3%–13.0% of the total DGs in each hybrid combination (Figure 2C).

Table 1.

DGs identified at the flowering and filling developmental stages for the three hybrid rice combinations investigated.

| Developmental stage | LY2163 | LY2186 | LYP9 | Three hybrid combinations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flowering (Fw) | 580 (1.6%) | 1,158 (3.1%) | 609 (1.6%) | 2,099 (5.7%) |

| Filling (Fi) | 640 (1.7%) | 635 (1.7%) | 550 (1.5%) | 1,488 (4.0%) |

| Fw + Fi | 1,193 (3.2%) | 1,630 (4.4%) | 1,046 (2.8%) | 3,142 (8.5%) |

2.2. DGs Functions in the Three Hybrid Combinations

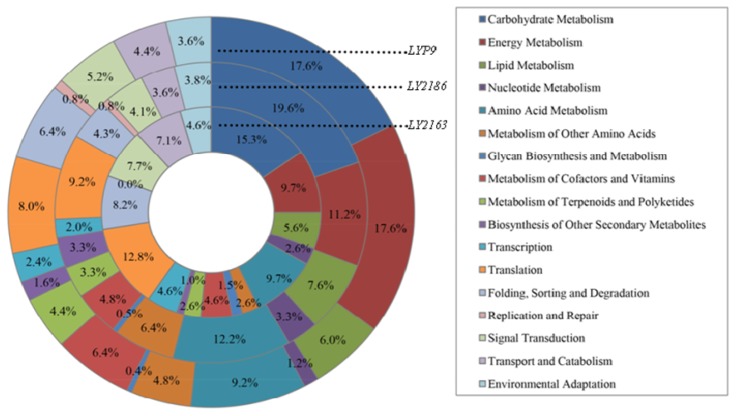

Using the functional categories of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database by KEGG Orthology-Based Annotation System (KOBAS) [32], we classified 149 of the 1193 DGs in LY2163, 282 of 1630 DGs in LY2186 and 185 of 1046 DGs in LYP9 into 17 functional categories and found that all three hybrid combinations had a similar percentage of DGs in the classified functional categories (Figure 4). A large percentage of the DGs were involved in functional categories for carbohydrate metabolism and energy metabolism. A total of 15.3%, 19.6% and 17.6% of DGs of the LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9 hybrid combination, respectively, were classified into the carbohydrate metabolism category, and 9.7%, 11.2% and 17.6% of DGs, respectively, were classified into the energy metabolism category. These results were similar to those obtained in our previous study [16] and suggested that carbohydrate metabolism and energy metabolism may play roles in rice heterosis.

Figure 4.

Graphical representation for the function classification of DGs in the F1 hybrid of three hybrid combinations.

We used MicroArray Data Interface for Biological Annotation (MADIBA) to perform Gene Ontology (GO) analysis in order to investigate the functional categories of the genes further. The results showed that 254 out of 1193, 440 out of 1630, and 297 out of 1046 DGs at the flowering and filling stages were assigned to 87, 126 and 91 GO terms from the cellular component category, in LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9, respectively (Table S9). In total, 39 GO terms are over-represented (p < 0.05) in the three combinations and two GO terms: the chloroplast and protein serine/threonine phosphatase complex were shared by three hybrid combinations. It is very interesting that among these GO terms, the DGs were significantly enriched in the chloroplast or chloroplast-related GO terms. DGs enrichment in the chloroplast indicates major changes in the photosynthetic ability of the F1 hybrids compared to their parents.

2.3. Metabolic Pathway Analysis of the DGs

The metabolic pathway analysis of total DGs by MADIBA [33] showed the involvement of 116 out of 1193 DGs in LY2163, 262 out of 1630 DGs in LY2186 and 148 out of 1046 DGs in LYP9 at either the flowering stage or filling stage (Table S10). Fisher’s exact test showed that the DGs were distributed in 71, 97 and 86, respectively, out of 143 metabolic pathways and were mainly enriched in categories, such as flavonoid biosynthesis and photosynthesis (light reactions). The carbon fixation pathway in particular showed significant DGs enrichment (p < 0.01) in all three super-hybrid combinations (Table 2, Table S10). The carbon fixation pathway transforms CO2 into organic compounds and can be a growth-limiting factor in modern agriculture [34]. The DGs enrichment of the carbon fixation pathway category suggested that carbon fixation efficiency may be enhanced in hybrid rice. Our previous study revealed that F1 hybrids showed more than 10% higher net photosynthetic rates than their parents in different hybrid combinations [16]. The results of the present study are consistent with previous findings that increased photosynthetic activity in the hybrids is responsible for heterosis [16,35].

Table 2.

The top ten DG-enriched metabolic pathways in the three hybrid rice combinations.

| Overall rank a | Metabolic pathway b | LY2163 | LY2186 | LYP9 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| p-value c | Rank d | p-value c | Rank d | p-value c | Rank d | ||

| 1 | Carbon fixation | 5.37 × 10−3 | 1 | 2.36 × 10−6 | 1 | 1.03 × 10−4 | 1 |

| 2 | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 0.185 | 3 | 0.192 | 4 | 0.116 | 3 |

| 3 | Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | 0.224 | 4 | 0.151 | 3 | 0.266 | 8 |

| 4 | Photosynthesis | 0.045 | 2 | 0.493 | 13 | 0.056 | 2 |

| 5 | Reductive carboxylate cycle (CO2 fixation) | 0.514 | 6 | 0.258 | 6 | 0.284 | 10 |

| 6 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 0.595 | 10 | 0.062 | 2 | 0.659 | 26 |

| 7 | Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 0.779 | 17 | 0.414 | 10 | 0.345 | 11 |

| 8 | Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle | 0.341 | 5 | 0.312 | 9 | 0.665 | 28 |

| 9 | Starch and sucrose metabolism | 0.755 | 16 | 0.297 | 8 | 0.632 | 23 |

| 10 | Streptomycin biosynthesis | 0.857 | 26 | 0.561 | 17 | 0.129 | 4 |

The overall rank is rank of the average of the individual pathway ranks for the three hybrid combinations;

metabolic pathway analysis was based on MicroArray Data Interface for Biological Annotation (MADIBA) [33];

the p-value is provided by Fisher’s exact test; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant;

rank indicates the significance of the pathway in each hybrid combination.

We observed that some DGs belonging to certain metabolic pathways were shared in the three hybrid combinations (Figures S2–S4), e.g., genes encoding phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Os03g15050), pyruvate, phosphate dikinase (Os05g33570), phosphoribulokinase (Os02g47020) and fructose-bisphosphatase (Os01g64660) in the carbon fixation pathway and β-fructofuranosidase (Os02g01590) and β-glucosidase (Os04g43390) in the starch and sucrose metabolic pathway. A significant proportion of these DGs may play important roles in heterosis (Figures S2–S4). Meanwhile, DGs were also found to be involved in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in the three hybrid combinations (Table 2). For example, the chalcone synthase gene (Os11g32650), involved in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway, is upregulated in both LY2186 and LYP9 hybrid combinations (compared to mid-parents) at the filling stage. Flavonoids have a variety of roles, including stress tolerance, UV-B protection [36,37] and regulation of auxin transport [38]. They have also been implicated in Arabidopsis heterosis [39,40]. Therefore, the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway may play a fundamental role in plant heterosis in Arabidopsis and rice.

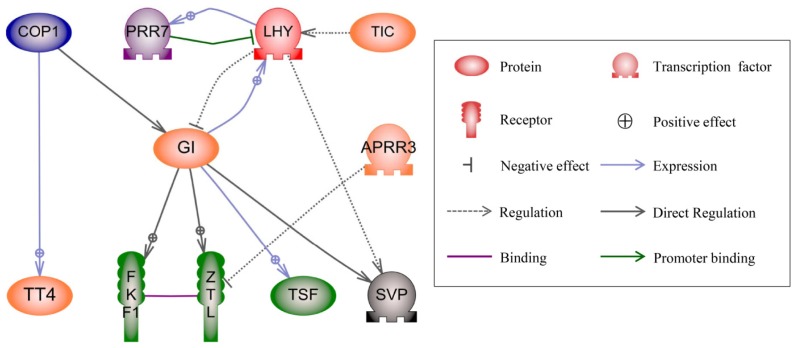

2.4. Regulatory Network Analysis of DGs in the Three Hybrids

Most genes usually need to operate synergistically with other genes to realize their biological functions [41]. To comprehensively understand the functions of DGs and their roles in heterosis, we constructed the DG-associated regulatory network in the three hybrid combinations. Eleven DGs involved in the circadian regulatory network were identified in the three hybrid combinations using Pathway Studio 9.0 software [42] (Table S11 and Figure 5). Of these 11 DGs, three DGs, LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL (LHY), PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR 7 (PRR7) and SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE (SVP), were identified in the LY2163 hybrid combination; eight DGs, LHY, GIGANTEA (GI), ZEITLUPE (ZTL), TRANSPARENT TESTA 4 (TT4), PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR 3 (APRR3), TIME FOR COFFEE (TIC), FLAVIN-BINDING KELCH REPEAT F-BOX1 (FKF1) and TWIN SISTER OF FT (TSF), were identified in the LY2186 hybrid combination; and seven DGs, TIC, LHY, APRR3, PRR7, GI, CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1 (COP1) and TT4, were identified in the LYP9 hybrid combination (Figure 5 and Table S11). In this network, the LHY activates the expression of PRR7 [43], which, in turn, negatively regulates the expression of LHY [44] and forms a feedback loop (Figure 5). Another feedback loop is between GI and LHY, GI promotes the expression of LHY and LHY represses GI [45,46]. All these DGs encode key components of the circadian clock [47]. COP1 can modulate the light input signal to the circadian clock by targeting GI for degradation [48], and GI can interact with the blue light-sensing F-box proteins, FLAVIN-BINDING, KELCH REPEAT, F-BOX 1 (FKF1) [49] and ZEITLUPE (ZTL) [50], which are involved in regulating flowering time and circadian rhythms.

Figure 5.

Gene regulatory network in three hybrid combinations. DGs in three hybrid combinations were used for direct interaction analysis by Pathway Studio 9.0. Interaction searching includes promoter binding, expression, regulation and binding. LHY, LATE ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL; PRR7, PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR 7; SVP, SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE; TIC, TIME FOR COFFEE; GI, GIGANTEA; ZTL, ZEITLUPE; APRR3, PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR 3; FKF1, FLAVIN-BINDING, KELCH REPEAT, F-BOX 1; TSF, TWIN SISTER OF FT; COP1, CONSTITUTIVELY PHOTOMORPHOGENIC 1; TT4, TRANSPARENT TESTA 4. Black, dark green, navy refers to protein are encoded by DGs in LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9 respectively; dark magenta refers to protein are encoded by DGs in LY2163 and LYP9; orange refers to protein are encoded by DGs in LY2186 and LYP9; red refers to protein are encoded by DGs in LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9.

In this study, changes in the expression levels of circadian clock-related genes were identified in all three hybrids. The circadian clock can also coordinate plant physiological metabolism and responses to changes in the external environment to provide plants with a growth advantage [51]. The circadian clock can also regulate many biological processes, such as photosynthesis [52] and starch and sucrose metabolism [53]. Epigenetic modification of two key regulator genes (CCA1 and LHY) in the circadian rhythm network resulted in altered levels of gene expression during photosynthesis and in the starch and sugar metabolic pathways, which led to growth vigor in Arabidopsis allopolyploids and hybrids [54]. Recent studies reported that methylation of CCA1, LHY genes and genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis in hybrids, may be responsible for heterosis in Arabidopsis [40]. From the above, it is apparent that DGs involved in the circadian clock play a central role in rice heterosis.

2.5. Mapping of DGs Quantitative Trait Loci (QTLs)

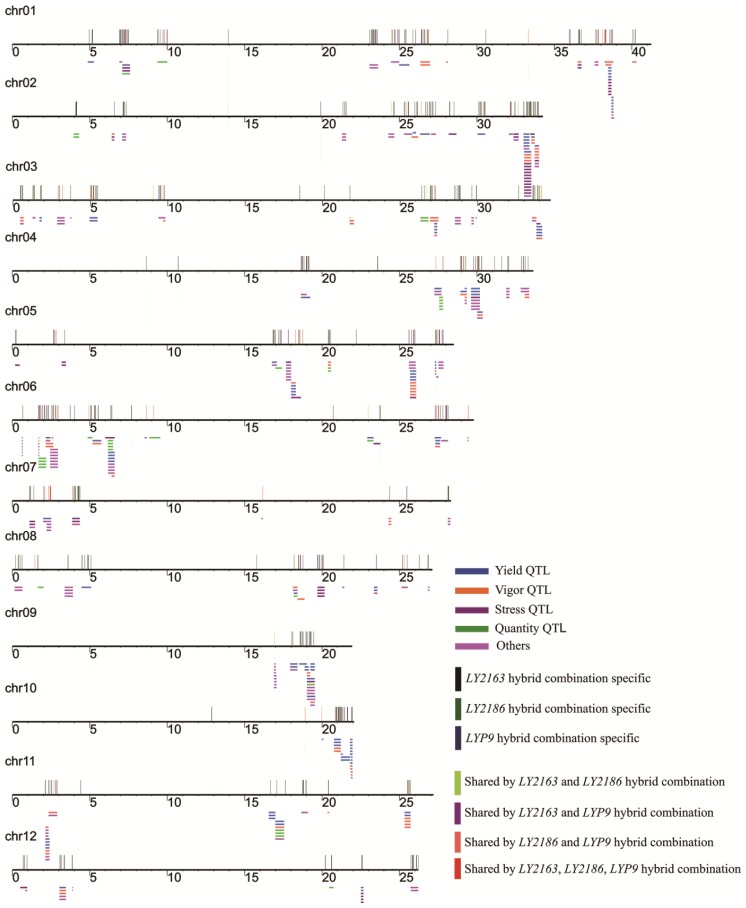

In order to examine whether DGs have potential associations with agronomic traits in hybrid rice, we mapped 2682 DGs to 4476 QTLs based on their genome coordinates in the Gramene database [55] (Table 3). Among them, 120 DGs and 3884 QTLs were shared by all three hybrid combinations. In the LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9 hybrid combinations; 989, 1385 and 884 DGs were mapped to 909, 1006 and 969 QTLs in the yield category, respectively (Table 3), and 882 QTLs were shared by all three hybrid combinations (Table 3). More than 80% of the DGs were located in QTLs, of which over 90% were in the yield-related QTLs in the three hybrid combinations. Similar results were found after the transcriptional profiling of the LY2186 hybrid combination by Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE) [16]. Furthermore, in the LY2163, LY2186 and LYP9 hybrid combinations, we identified 164, 276 and 195 DGs that were located in 354, 591 and 424 QTLs, collectively 737 QTLs at small intervals of less than 100 genes (Figure 6).

Table 3.

Correlations between DGs a and quantitative trait locus (QTL) b in the three hybrid rice combinations.

| Category | LY2163 | LY2186 | LYP9 | Shared by three hybrid combinations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of DGs | 1,193 | 1,630 | 1,046 | 136 |

| DGs located to QTL | 1,004 | 1,411 | 894 | 120 |

| DGs located to yield-related QTL | 989 | 1385 | 884 | 119 |

| Number of QTL located by DGs | 4,057 | 4,326 | 4,114 | 3,884 |

| QTL of yield category | 909 | 1,006 | 969 | 882 |

| QTL of vigor category | 939 | 995 | 953 | 911 |

| QTL of Sterility or fertility category | 137 | 156 | 137 | 124 |

| QTL of quality category | 326 | 341 | 318 | 310 |

| QTL of development category | 427 | 450 | 421 | 412 |

| QTL of abiotic stress category | 346 | 365 | 339 | 315 |

| QTL of biotic stress category | 211 | 220 | 212 | 208 |

| QTL of biochemical category | 108 | 112 | 110 | 107 |

| QTL of anatomy category | 654 | 681 | 655 | 615 |

Refers to differentially expressed genes between the hybrid and its parents;

refers to QTLs in the Gramene database [55] that harbor DGs were aligned with the gene coordinates in Rice Genome Annotation Release 6.1.

Figure 6.

Distribution of DGs among QTLs of a small interval. QTLs in Gramene (number of harbored genes ≤ 100) and harbored DGs were aligned to the Michigan State University (MSU) Rice Genome Release 6.1. The long horizontal line represents 12 chromosomes of the rice genome; the short horizontal lines represent the QTL span, and short vertical lines represent DGs.

Among the DG-located QTLs, many were well characterized, including panicle number (CQAQ9, CQJ1, CQK1, CQK2, etc.), seed number (CQAS138, CQAS142, CQAS21, CQAS25, etc.), 1000 seed weight (AQAK031, AQCY015, AQCY017, CQAS23, etc.) and grain yield (AQGK001, AQFF004, AQFF006, AQDK009, etc.). Functional annotation of some DGs can explain the QTL traits to some degree, for example soluble starch synthase 3 (Os04g53310) to AQCY010 for the filled grain number, glycoside hydrolase (Os03g03350) to CQAS39 for yield and malate dehydrogenase (Os01g46070) to CQN50 for the spikelet number. All the above results indicated that DGs can correlate with the superior heterotic traits in hybrid rice. Interestingly, the DG GRAIN INCOMPLETE FILLING 1 (GIF1, Os04g33740) in the LY2186 hybrid combination could be mapped to the yield-related QTLs involved in filled grain number, seed set percentage and 100 seed weight. A recent report showed that GIF could increase yield through improved grain filling [56].

As described above, although only a few shared DGs were found among the three hybrid combinations, they shared similar functional categories and mapped to the QTLs of similar agronomic traits, which indicated that in different hybrid combinations, genes that determined the traits were different, but they belonged to the same or similar pathways and played similar roles in determining the superior heterotic phenotype. Hybrids from different hybrid combinations may have different traits or the same traits may be regulated by different genes, because of their different breeding strategies and methods. However, the genes that determined the same traits may have been artificially selected, and the underlying molecular regulatory apparatus may be similar. These results suggested that different hybrid rice varieties in different combinations may have different genes contributing to the heterotic phenotype, but they all had a similar higher level regulatory mechanism. High grain yield is an important characteristic in all three hybrids and is determined mainly by three typical quantitative traits: the number of panicles, the number of grains per panicle and grain weight [57]. This suggests that the yield heterosis of the different combinations does not arise from a single or a small number of genes. Most of the DGs in the QTLs were different in the three tested hybrid combinations, but they tended to be located in similar QTLs. This suggested that the yield heterosis in the three hybrid combinations may be caused by different genes with more or less similar functions. In this study, we have established the potential correlations between DGs and agricultural traits and indicated promising insights for understanding the common mechanism of heterosis in rice.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Plant Materials

Three super-hybrid rice cultivars: LY2163 (SE21s × MH63), LY2186 (SE21s × MH86) and LYP9 (PA64s × 93-11) were grown in the same field. The flag leaves of the field-grown plants at the flowering and filling stages were sampled, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

3.2. Microarray Experiment and Data Processing

The whole-genome array was developed using the predicted genes of indica 93-11 [58,59] with 70-mer oligonucleotides. The microarray was designed by the microarray laboratory at the Beijing Genomic Institute (Beijing, China) using results from previous studies [18,60], and the slides were processed according to the standard procedure [61]. Total RNA was extracted according to the published methods [62], quantified and labeled with Cy5 and Cy3 [63,64]. There were four biological replicates for each sample, and two dye swap hybridizations were carried out for each sample pair in order to reduce biological and technical errors. Separate tagged image file format images of the Cy5 and Cy3 channels were obtained by a ScanArray Lite scanner (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA), and the spot intensities were quantified using Axon GenePix Pro 5.1 image analysis software (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). The raw data was processed (excluding dirty points and bad points) according to the criteria described previously [18]. The processed data were normalized using the mean of all the expressed genes. The normalization of the two-channel data for each array was carried out using the intensity-based Loess method with R language (A language and environment for statistical computing). DGs were defined by a log-scale ratio of signal intensity between the hybrid and either of its parents with a p < 0.01 (z-test) [18].

3.3. Functional Category and Metabolic Pathway Analysis

For the expressed genes investigation, we performed functional annotations using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) [65,66] against the MSU Rice Genome Annotation Project Release 6.1. Cluster analysis of the expressed genes from the hybrid combinations was undertaken using the hierarchical clustering method and GeneSpring GX 12.6 software (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Functional classification analysis of DGs was carried out by the KEGG orthology-based annotation system (KOBAS) version 2.0 [32]. The DGs pathway analysis was undertaken by MADIBA [33]. The p-value acquired was based on the number of enzymes found in each pathway by Fisher’s exact test.

3.4. Regulatory Network Analysis

The DGs list was analyzed for the presence of a regulatory network using Pathway Studio software (Ariadne Genomics, Rockville, MD, USA) [42], version 9.0, according to Entrez ID, which utilized DGs matched from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [67]. The ResNet Plant Database (version 4.0, Ariadne Genomics, Rockville, MD, USA) was used to identify the directed interactions among genes. These interactions were classified as promoter binding, expression, regulation and protein-protein binding types. False interaction relationships were eliminated using the references in the database.

3.5. Mapping DGs to Rice QTLs

Rice QTL data with physical positions on the MSU Rice Genome Annotation Project Release 6.1 were acquired from Gramene [55]. The DGs were mapped to rice QTLs using gene coordinates from the MSU Rice Genome Annotation Project, Release 6.1. QTLs at small intervals of less than 100 genes were mapped with DGs in the rice chromosomes, as described previously [18].

4. Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed the transcriptional profiles of three super-hybrid rice combinations at the flowering and grain filling stages. There were similar proportions of DGs in all three hybrid combinations; they had similar expression patterns and were mainly distributed in the carbohydrate metabolism and energy metabolism categories, which indicated that the three hybrid combinations had similar regulatory mechanisms. The DGs in each hybrid were particularly enriched in the carbon fixation pathway, the starch and sucrose metabolic pathway and the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway. The results were consistent with the higher photosynthesis and assimilation efficiency seen in hybrid rice [16]. We analyzed the DGs involved in the regulatory network and found that the circadian network could regulate DGs in the three important metabolic pathways mentioned above and played a key role in heterosis. Our research established a correlation between DGs and agricultural traits by mapping DGs to QTLs and revealed that a similar regulatory mechanism underlying heterosis may exist in a number of hybrid rice.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiujie Wang and Meng Wang for the advice in the regulatory network analysis and Kranthi Kumar Gadidasu for editing the manuscript. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012AA10A304 and 2013AA102701), the “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA08010402), the Ministry of Agriculture of China (2014ZX08012-002), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31100931 and 91335111) and the State Key Laboratory of Plant Genomics of China (2013B0125-3).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Y.P., G.W. and L.Z. initiated the research, carried out the biological experiments, performed the computational analyses, co-designed and drafted the manuscript. G.L. co-designed, analyzed the data and revised the manuscript. X.W. participated in the biological experiments and material collections. Z.Z. designed, interpreted the results and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Melchinger A.E., Gumber R.K. Overview of Heterosis and Heterotic Groups in Agronomic Crops. In: Lamkey K.R., Staub J.E., editors. Concepts and Breeding of Heterosis in Crop Plants. Crop Science Society of America; Madison, WI, USA: 1998. pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng S.H., Zhuang J.Y., Fan Y.Y., Du J.H., Cao L.Y. Progress in research and development on hybrid rice: A super-domesticate in China. Ann. Bot. 2007;100:959–966. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang L., Peng Y., Dong Y., Li H., Wang W., Zhu Z. Progress of Genomics and Heterosis Studies in Hybrid Rice. In: Chen Z.J., Birchler J.A., editors. Polyploid and Hybrid Genomics. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Oxford, UK: 2013. pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birchler J.A., Auger D.L., Riddle N.C. In search of the molecular basis of heterosis. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2236–2239. doi: 10.1105/tpc.151030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semel Y., Nissenbaum J., Menda N., Zinder M., Krieger U., Issman N., Pleban T., Lippman Z., Gur A., Zamir D. Overdominant quantitative trait loci for yield and fitness in tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12981–12986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604635103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birchler J.A. Reflections on studies of gene expression in aneuploids. Biochem. J. 2010;426:119–123. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce A.B. The Mendelian theory of heredity and the augmentation of vigor. Science. 1910;32:627–628. doi: 10.1126/science.32.827.627-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones D.F. Dominance of linked factors as a means of accounting for heterosis. Genetics. 1917;2:466–479. doi: 10.1093/genetics/2.5.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shull G.H. The composition of a field of maize. Am. Breed. Assoc. Rep. 1908;4:296–301. [Google Scholar]

- 10.East E.M. Heterosis. Genetics. 1936;21:375–397. doi: 10.1093/genetics/21.4.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu S.B., Li J.X., Xu C.G., Tan Y.F., Gao Y.J., Li X.H., Zhang Q., Saghai Maroof M.A. Importance of epistasis as the genetic basis of heterosis in an elite rice hybrid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:9226–9231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hochholdinger F., Hoecker N. Towards the molecular basis of heterosis. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schnable P.S., Springer N.M. Progress toward understanding heterosis in crop plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013;64:71–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krieger U., Lippman Z.B., Zamir D. The flowering gene SINGLE FLOWER TRUSS drives heterosis for yield in tomato. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:459–463. doi: 10.1038/ng.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bao J., Lee S., Chen C., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Liu S., Clark T., Wang J., Cao M., Yang H., et al. Serial analysis of gene expression study of a hybrid rice strain (LYP9) and its parental cultivars. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:1216–1231. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.060988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song G.S., Zhai H.L., Peng Y.G., Zhang L., Wei G., Chen X.Y., Xiao Y.G., Wang L., Chen Y.J., Wu B., et al. Comparative transcriptional profiling and preliminary study on heterosis mechanism of super-hybrid rice. Mol. Plant. 2010;3:1012–1025. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssq046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song S., Qu H., Chen C., Hu S., Yu J. Differential gene expression in an elite hybrid rice cultivar (Oryza sativa L) and its parental lines based on SAGE data. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei G., Tao Y., Liu G., Chen C., Luo R., Xia H., Gan Q., Zeng H., Lu Z., Han Y., et al. A transcriptomic analysis of superhybrid rice LYP9 and its parents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:7695–7701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902340106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang H.Y., He H., Chen L.B., Li L., Liang M.Z., Wang X.F., Liu X.G., He G.M., Chen R.S., Ma L.G., et al. A genome-wide transcription analysis reveals a close correlation of promoter INDEL polymorphism and heterotic gene expression in rice hybrids. Mol. Plant. 2008;1:720–731. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He G., Zhu X., Elling A.A., Chen L., Wang X., Guo L., Liang M., He H., Zhang H., Chen F., et al. Global epigenetic and transcriptional trends among two rice subspecies and their reciprocal hybrids. Plant Cell. 2010;22:17–33. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swanson-Wagner R.A., Jia Y., DeCook R., Borsuk L.A., Nettleton D., Schnable P.S. All possible modes of gene action are observed in a global comparison of gene expression in a maize F1 hybrid and its inbred parents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:6805–6810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510430103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uzarowska A., Keller B., Piepho H.P., Schwarz G., Ingvardsen C., Wenzel G., Lubberstedt T. Comparative expression profiling in meristems of inbred-hybrid triplets of maize based on morphological investigations of heterosis for plant height. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;63:21–34. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9069-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ni Z., Sun Q., Liu Z., Wu L., Wang X. Identification of a hybrid-specific expressed gene encoding novel RNA-binding protein in wheat seedling leaves using differential display of mRNA. Mol. Gen. Genet. 2000;263:934–938. doi: 10.1007/pl00008693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu L.M., Ni Z.F., Meng F.R., Lin Z., Sun Q.X. Cloning and characterization of leaf cDNAs that are differentially expressed between wheat hybrids and their parents. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2003;270:281–286. doi: 10.1007/s00438-003-0919-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yao Y., Ni Z., Zhang Y., Chen Y., Ding Y., Han Z., Liu Z., Sun Q. Identification of differentially expressed genes in leaf and root between wheat hybrid and its parental inbreds using PCR-based cDNA subtraction. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005;58:367–384. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-5102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vuylsteke M., van Eeuwijk F., van Hummelen P., Kuiper M., Zabeau M. Genetic analysis of variation in gene expression in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2005;171:1267–1275. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.041509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoecker N., Keller B., Muthreich N., Chollet D., Descombes P., Piepho H.P., Hochholdinger F. Comparison of maize (Zea mays L) F1-hybrid and parental inbred line primary root transcriptomes suggests organ-specific patterns of nonadditive gene expression and conserved expression trends. Genetics. 2008;179:1275–1283. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.088278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ge X., Chen W., Song S., Wang W., Hu S., Yu J. Transcriptomic profiling of mature embryo from an elite super-hybrid rice LYP9 and its parental lines. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flint-Garcia S.A., Buckler E.S., Tiffin P., Ersoz E., Springer N.M. Heterosis is prevalent for multiple traits in diverse maize germplasm. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stupar R.M., Gardiner J.M., Oldre A.G., Haun W.J., Chandler V.L., Springer N.M. Gene expression analyses in maize inbreds and hybrids with varying levels of heterosis. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:33. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.China Rice Data Center. [(accessed on 24 January 2014)]. Available online: http://www.ricedata.cn.

- 32.Xie C., Mao X., Huang J., Ding Y., Wu J., Dong S., Kong L., Gao G., Li C.Y., Wei L. KOBAS 20: A web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W316–W322. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Law P.J., Claudel-Renard C., Joubert F., Louw A.I., Berger D.K. MADIBA: A web server toolkit for biological interpretation of Plasmodium and plant gene clusters. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bar-Even A., Noor E., Lewis N.E., Milo R. Design and analysis of synthetic carbon fixation pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:8889–8894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907176107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujimoto R., Taylor J.M., Shirasawa S., Peacock W.J., Dennis E.S. Heterosis of Arabidopsis hybrids between C24 and Col is associated with increased photosynthesis capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:7109–7114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204464109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J., Ou-Lee T.M., Raba R., Amundson R.G., Last R.L. Arabidopsis flavonoid mutants are hypersensitive to UV-B irradiation. Plant cell. 1993;5:171–179. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bieza K., Lois R. An Arabidopsis mutant tolerant to lethal ultraviolet-B levels shows constitutively elevated accumulation of flavonoids and other phenolics. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:1105–1115. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.3.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peer W.A., Murphy A.S. Flavonoids and auxin transport: Modulators or regulators? Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korn M., Peterek S., Mock H.P., Heyer A.G., Hincha D.K. Heterosis in the freezing tolerance and sugar and flavonoid contents of crosses between Arabidopsis thaliana accessions of widely varying freezing tolerance. Plant Cell Environ. 2008;31:813–827. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen H., He H., Li J., Chen W., Wang X., Guo L., Peng Z., He G., Zhong S., Qi Y., et al. Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation and gene expression changes in two Arabidopsis ecotypes and their reciprocal hybrids. Plant Cell. 2012;24:875–892. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.094870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barabasi A.L., Oltvai Z.N. Network biology: Understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrg1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nikitin A., Egorov S., Daraselia N., Mazo I. Pathway studio—The analysis and navigation of molecular networks. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2155–2157. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farre E.M., Harmer S.L., Harmon F.G., Yanovsky M.J., Kay S.A. Overlapping and distinct roles of PRR7 and PRR9 in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakamichi N., Kiba T., Henriques R., Mizuno T., Chua N.H., Sakakibara H. Pseudo-response regulators 9 7 and 5 are transcriptional repressors in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2010;22:594–605. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.072892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalchau N., Baek S.J., Briggs H.M., Robertson F.C., Dodd A.N., Gardner M.J., Stancombe M.A., Haydon M.J., Stan G.B., Goncalves J.M., et al. The circadian oscillator gene GIGANTEA mediates a long-term response of the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock to sucrose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:5104–5109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015452108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mizoguchi T., Wheatley K., Hanzawa Y., Wright L., Mizoguchi M., Song H.R., Carre I.A., Coupland G. LHY and CCA1 are partially redundant genes required to maintain circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:629–641. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murakami M., Tago Y., Yamashino T., Mizuno T. Comparative overviews of clock-associated genes of Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48:110–121. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu J.W., Rubio V., Lee N.Y., Bai S., Lee S.Y., Kim S.S., Liu L., Zhang Y., Irigoyen M.L., Sullivan J.A., et al. COP1 and ELF3 control circadian function and photoperiodic flowering by regulating GI stability. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:617–630. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fornara F., Panigrahi K.C., Gissot L., Sauerbrunn N., Ruhl M., Jarillo J.A., Coupland G. Arabidopsis DOF transcription factors act redundantly to reduce CONSTANS expression and are essential for a photoperiodic flowering response. Dev. Cell. 2009;17:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim W.Y., Fujiwara S., Suh S.S., Kim J., Kim Y., Han L., David K., Putterill J., Nam H.G., Somers D.E. ZEITLUPE is a circadian photoreceptor stabilized by GIGANTEA in blue light. Nature. 2007;449:356–360. doi: 10.1038/nature06132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harmer S.L. The circadian system in higher plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009;60:357–377. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yakir E., Hilman D., Harir Y., Green R.M. Regulation of output from the plant circadian clock. FEBS J. 2007;274:335–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Graf A., Schlereth A., Stitt M., Smith A.M. Circadian control of carbohydrate availability for growth in Arabidopsis plants at night. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:9458–9463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914299107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ni Z., Kim E.D., Ha M., Lackey E., Liu J., Zhang Y., Sun Q., Chen Z.J. Altered circadian rhythms regulate growth vigour in hybrids and allopolyploids. Nature. 2009;457:327–331. doi: 10.1038/nature07523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Youens-Clark K., Buckler E., Casstevens T., Chen C., DeClerck G., Derwent P., Dharmawardhana P., Jaiswal P., Kersey P., Karthikeyan A.S. Gramene database in 2010: Updates and extensions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D1085–D1094. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang E., Wang J., Zhu X., Hao W., Wang L., Li Q., Zhang L., He W., Lu B., Lin H., et al. Control of rice grain-filling and yield by a gene with a potential signature of domestication. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1370–1374. doi: 10.1038/ng.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xing Y., Zhang Q. Genetic and molecular bases of rice yield. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010;61:421–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu J., Hu S., Wang J., Wong G.K., Li S., Liu B., Deng Y., Dai L., Zhou Y., Zhang X., et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L ssp indica) Science. 2002;296:79–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1068037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu J., Wang J., Lin W., Li S., Li H., Zhou J., Ni P., Dong W., Hu S., Zeng C., et al. The genomes of Oryza sativa: A history of duplications. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma L., Chen C., Liu X., Jiao Y., Su N., Li L., Wang X., Cao M., Sun N., Zhang X., et al. A microarray analysis of the rice transcriptome and its comparison to Arabidopsis. Genome Res. 2005;15:1274–1283. doi: 10.1101/gr.3657405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eisen M.B., Brown P.O. DNA arrays for analysis of gene expression. Methods Enzymol. 1999;303:179–205. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)03014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bachem C.W.B., Oomen R.J.F.J., Visser R.G.F. Transcript imaging with cDNA-AFLP: A step-by-step protocol. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 1998;16:157–157. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ma L., Gao Y., Qu L., Chen Z., Li J., Zhao H., Deng X.W. Genomic evidence for COP1 as a repressor of light-regulated gene expression and development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2383–2398. doi: 10.1105/tpc.004416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ma L., Li J., Qu L., Hager J., Chen Z., Zhao H., Deng X.W. Light control of Arabidopsis development entails coordinated regulation of genome expression and cellular pathways. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2589–2607. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maglott D., Ostell J., Pruitt K.D., Tatusova T. Entrez gene: Gene-centered information at NCBI. Nucleic Acids. Res. 2011;39:D52–D57. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]