Abstract

We investigated the protective effects of chlorogenic acid (CGA), a polyphenol compound, on oxidative damage induced by UVB exposure on human HaCaT cells. In a cell-free system, CGA scavenged 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radicals, superoxide anions, hydroxyl radicals, and intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by hydrogen peroxide and ultraviolet B (UVB). Furthermore, CGA absorbed electromagnetic radiation in the UVB range (280–320 nm). UVB exposure resulted in damage to cellular DNA, as demonstrated in a comet assay; pre-treatment of cells with CGA prior to UVB irradiation prevented DNA damage and increased cell viability. Furthermore, CGA pre-treatment prevented or ameliorated apoptosis-related changes in UVB-exposed cells, including the formation of apoptotic bodies, disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, and alterations in the levels of the apoptosis-related proteins Bcl-2, Bax, and caspase-3. Our findings suggest that CGA protects cells from oxidative stress induced by UVB radiation.

Keywords: Chlorogenic acid, Human keratinocyte, Ultraviolet B, Oxidative stress, Apoptosis

INTRODUCTION

Chlorogenic acid (3-[3,4-dihydroxycinnamoyl] quinic acid, CGA) is an antioxidant compound found in numerous plant species, including coffee beans, apples, and blueberries (Kiehne and Engelhardt, 1996; Rice-Evans et al., 1996). Structurally, CGA is related to a group of polyphenol compounds consisting of esters formed by hydroxycinnamates (caffeic acid, ferulic acid, or p-coumaric acid) and quinic acid (Rice-Evans et al., 1996). Polyphenol compounds share the common structural group phenol, an aromatic ring linkage with at least one hydroxyl substituent. It has been reported that some plant polyphenols can be applied for photo-protection against UV-induced skin damage (Vayalil et al., 2003; Caddeo et al., 2008). CGA exerts its antioxidant activity through this structural moiety (Kiehne and Engelhardt, 1996; Fiorentino et al., 2008).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are naturally produced in the body as a result of normal metabolism or environmental exposure. At high concentrations, ROS may induce oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins. Oxidation of these cellular substrates can cause degenerative disease (Ames et al., 1993; Paganga et al., 1999; Mayne, 2003; Valko et al., 2007).

UVB radiation can have deleterious effects on the skin, including carcinogenesis, inflammation, solar erythema, and premature aging (Sime and Reeve, 2004; Karol, 2009; Narayanan et al., 2010). For example, excessive UVB exposure triggers severe phenotypic changes in the dorsal skin of mice (Park et al., 2013). ROS generated as a consequence of UV irradiation can oxidize and damage cellular lipids, proteins and DNA, leading to changes and often to destruction of skin structures, which can result in inhibition of their regular function (Dhumrongvaraporn and Chanvorachote, 2013; Sklar et al., 2013). Therefore, many efforts have been made to prevent/treat these events caused by UV exposure. Antioxidants from natural or synthetic sources provide new possibilities for treatment and prevention of UV-oxidative stressed damage (Campanini et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2013).

CGA has shown its photo-protection against UV-induced skin damage in animal model and displayed the suppression on UVB-related ROS mediated cellular processes in vivo (Feng et al., 2005; Kitagawa et al., 2011). Moreover, CGA protects mesenchymal stem cells against oxidative stress (Li et al., 2012). Here, we investigated whether CGA can protect keratinocytes against UVB-induced oxidative damage and elucidated the mechanisms underlying the protective effect of CGA against UVB-induced cellular oxidative stress in human HaCaT keratinocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Chlorogenic acid (CGA) was provided by Professor Sam Sik Kang (Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea) (Lee et al., 2010). The following compounds were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA): 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO), 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA), [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium] bromide (MTT), and Hoechst 33342 dye. Primary antibodies against Bcl-2 and Bax were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA); a primary antibody against actin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc.; and a primary antibody against caspase-3 was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

Cell culture

The human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT was obtained from the Amore Pacific Company (Gyeonggi-do, Korea) and maintained at 37°C in an incubator with a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and penicillin (100 units/ml).

Cell viability assay

The effect of CGA on the viability of HaCaT cells was assessed as follows: cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 0.3×105 cells/ml, and treated 20 h later with 5, 10, 20, 40, or 80 μM CGA. MTT stock solution (50 μl, 2 mg/ml) was added to each well to yield a total reaction volume of 200 μl. Four hours later, the supernatants were aspirated. The formazan crystals in each well were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO, and the absorbance at 540 nm was read on a scanning multi-well spectrophotometer (Carmichael et al., 1987).

Detection of the DPPH radicals

CGA (5, 10, 20, 40 or 80 μM) or NAC (1 mM) was added to 1×10−4 M DPPH in methanol, and the resulting reaction mixture was shaken vigorously. After 3 h, the amount of unreacted DPPH was determined by measuring the absorbance at 520 nm on a spectrophotometer.

Detection of superoxide anions

Superoxide anions generated by the xanthine/xanthine oxidase system were reacted with DMPO, and the resultant DMPO/•OOH adducts were detected using an ESR spectrometer (Li et al., 2003, 2004). The ESR spectrum was recorded 2.5 min after a phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4) was mixed with 0.02 ml each of 3 M DMPO, 5 mM xanthine, 0.25 U xanthine oxidase, and 20 μM CGA. The ESR spectrometer parameters were set as follows: central magnetic field, 336.8 mT; power, 5.00 mW; frequency, 9.4380 GHz; modulation width, 0.2 mT; amplitude, 1000; sweep width, 10 mT; sweep time, 0.5 min; time constant, 0.03 sec; and temperature, 25°C.

Detection of hydroxyl radicals

Hydroxyl radicals generated by the Fenton reaction (H2O2+FeSO4) were reacted with DMPO. The resultant DMPO/•OH adducts were detected using an ESR spectrometer (Li et al., 2003, 2004). The ESR spectrum was recorded 2.5 min after a phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.4) was mixed with 0.02 ml each of 0.3 M DMPO, 10 mM FeSO4, 10 mM H2O2, and 20 μM CGA. The ESR spectrometer parameters were set as follows: central magnetic field, 336.8 mT; power, 1.00 mW; frequency, 9.4380 GHz; modulation width, 0.2 mT; amplitude, 600; sweep width, 10 mT; sweep time, 0.5 min; time constant, 0.03 sec; temperature, 25°C.

Detection of intracellular ROS

The DCF-DA method was used to detect intracellular ROS generated by H2O2 or UVB (Rosenkranz et al., 1992). To detect ROS in H2O2- or UVB-treated HaCaT cells, cells were seeded in plates at a density of 1.2×105 cells/well and treated 20 h later with 20 μM CGA. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, cells were exposed to H2O2 (1 mM) or UVB (30 mJ/cm2). The UVB source was a CL-1000M UV Crosslinker (UVP, Upland, CA, USA). After an additional 30 min at 37°C, DCF-DA solution (50 μM) was added. Ten minutes later, the fluorescence of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) was detected and quantified using a PerkinElmer LS-5B spectrofluorometer (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Scavenging effect of intracellular ROS (%) = (absorbance of control - absorbance of CGA or NAC)/absorbance of control×100. The control indicates H2O2 or UVB-treated group.

UV/visible light absorption analysis

To study the UVB absorption spectra of CGA, the compound was scanned from 250 to 400 nm on a Biochrom Libra S22 UV/visible spectrophotometer (Biochrom, Cambridge, UK). CGA was diluted 1:500 in DMSO prior to scanning.

Single-cell gel electrophoresis (Comet assay)

The degree of oxidative DNA damage was assessed in a comet assay (Singh, 2000; Rajagopalan et al., 2003). A cell suspension was mixed with 70 μl of 1% low-melting agarose (LMA) at 37°C and the mixture spread onto a fully frosted microscopic slide pre-coated with 200 μl of 1% normal melting agarose (NMA). After solidification of the agarose, the slide was covered with another 170 μl of 0.5% LMA and then immersed in lysis solution (2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM Na-EDTA, 10 mM Tris, 1% Trion X-100, and 10% DMSO, pH 10) for 1 h at 4°C. The slides were subsequently placed in a gel electrophoresis apparatus containing 300 mM NaOH and 10 mM Na-EDTA (pH 13) and incubated for 30 min to allow for DNA unwinding and the expression of alkali-labile damage. An electrical field (300 mA, 25 V) was then applied for 30 min at 25°C to draw the negatively charged DNA towards the anode. The slides were washed three times for 10 min at 25°C in neutralizing buffer (0.4 M Tris, pH 7.5), and then washed once for 10 min at 25°C in 100% ethanol. Then, the slides were stained with 80 μl of 10 μg/ml ethidium bromide and observed using a fluorescence microscope and image analyzer (Kinetic Imaging, Komet 5.5, UK). The tail lengths and percentage of total fluorescence in the comet tails were recorded for 50 cells per slide.

Nuclear staining with Hoechst 33342

Cells were treated with 20 μM CGA and exposed to UVB radiation 3 h later. After a 24 h incubation at 37°C, the DNA-specific fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342 (1 μl of a 20 mM stock) was added to each well and the cells were incubated for 10 min at 37°C. The stained cells were visualized under a fluorescence microscope equipped with a CoolSNAP-Pro color digital camera. The degree of nuclear condensation was evaluated, and apoptotic cells were counted.

Analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm)

Cells were exposed to 30 mJ/cm2 UVB irradiation, treated with 20 μM CGA, and incubated at 37°C. After 12 h, the cells were stained with JC-1 (5 μM) and analyzed by flow cytometry (Troiano et al., 2007).

Western-blot analysis

Harvested cells were lysed by incubation on ice for 10 min in 160 μl of lysis buffer containing 120 mM NaCl, 40 mM Tris (pH 8), and 0.1% NP 40. The resultant cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,000×g for 5 min. Supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were determined. Aliquots (each containing 5 μg of protein) were boiled for 5 min and electrophoresed on 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Protein blots of the gels were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies (1:1000) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-IgG secondary antibodies (1:5000) (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). Protein bands were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection kit (Amersham, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Statistical analysis

All measurements were performed in triplicate and all values are expressed as the mean ± standard error. The results were subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) using Tukey’s test to analyze differences between means. In each case, a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

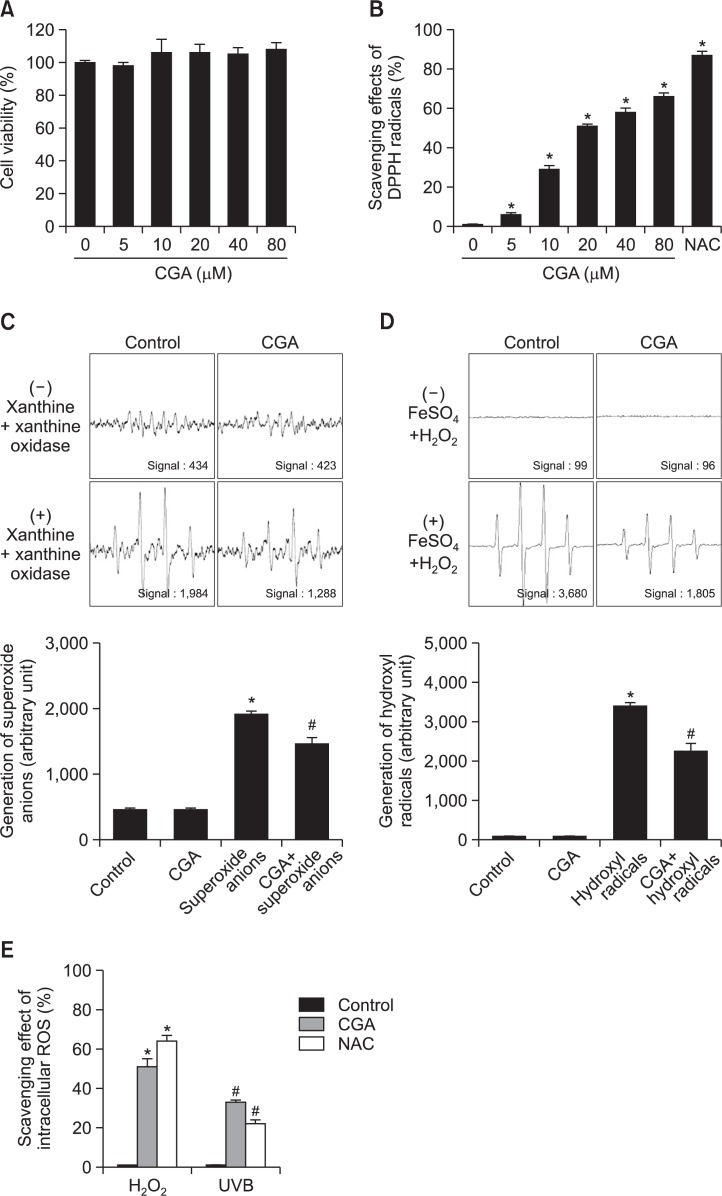

CGA scavenges free radicals including ROS

CGA was not cytotoxic at any concentration up to 80 μM: cell viability was ∼100% at all concentrations of CGA used (Fig. 1A). At concentrations ranging from 5–80 μM, the DPPH scavenging activity of CGA was increased in a concentration-dependent manner and an well-known antioxidant NAC (1 mM) was used to be positive control (Fig. 1B). Based on these results, we decided to use 20 μM CGA for all subsequent experiments. Next, we used ESR spectrometry to measure the ability of CGA to scavenge superoxide anions and hydroxyl radicals. In the xanthine/xanthine oxidase system, DMPO/•OOH yielded signals of 1,984 in the absence of CGA and 1,288 in the presence of CGA (Fig. 1C), indicating that CGA can scavenge superoxide anions. Similarly, in the FeSO4+H2O2 system (Fe2++H2O2 → Fe3++•OH+OH−), DMPO/•OH adducts yielded signals of 3,680 in the absence of CGA and 1,805 in the presence of CGA (Fig. 1D), indicating that CGA can scavenge hydroxyl radicals. In addition, we investigated whether CGA can scavenge intracellular ROS generated by H2O2 or UVB exposure. In H2O2-treated cells, 20 μM CGA scavenged 51% of ROS versus 64% for NAC, whereas in UVB-treated cells, 20 μM CGA scavenged 33% of ROS versus 22% for NAC (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

CGA scavenges ROS. (A) HaCaT cells were treated with CGA (0, 5, 10, 20, 40, or 80 μM) for 20 h. Cell viability was measured in an MTT assay. (B) Levels of the DPPH radical were measured spectrophotometrically at 520 nm. NAC (1 mM) served as the positive control. *Significantly different from the DPPH group (p<0.05). (C) The ability to scavenge superoxide anions was evaluated using the xanthine/xanthine oxidase system. *significantly different from control (p<0.05); #significantly different from superoxide anions (p<0.05). (D) Ability to scavenge hydroxyl radicals was estimated using the Fenton reaction (FeSO4+H2O2 system). *Significantly different from control (p<0.05); #significantly different from hydroxyl radicals (p<0.05). (E) The ability of CGA to scavenge intracellular ROS generated by H2O2 or UVB was evaluated in a DCF-DA assay. *,#Significantly different from control cells, respectively (p<0.05).

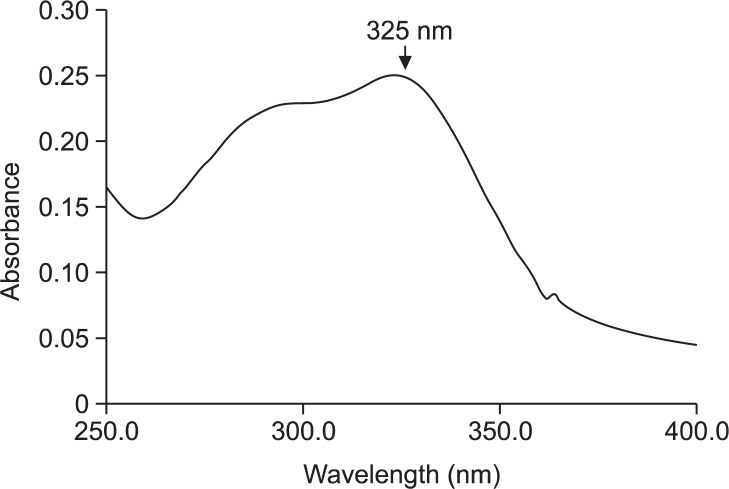

CGA absorbs UVB

To determine whether CGA itself exerts a UVB-protective effect, we investigated the light absorption of CGA over a range of UV and visible wavelengths (250–400 nm). CGA absorbed light efficiently in the UVB range (280–320 nm), with a peak at 325 nm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

CGA absorbs in the UV/visible range. UV/visible spectroscopic measurements were performed over a spectral range of 250–400 nm. The arrow indicates the absorbance peak at 325 nm.

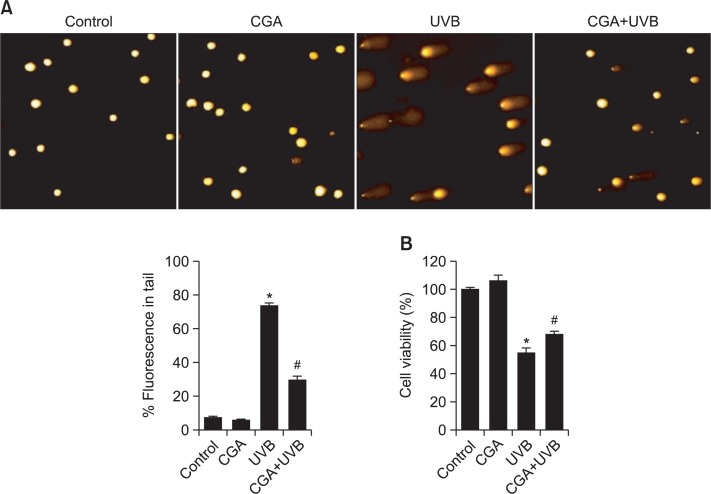

CGA suppresses UVB-induced DNA damage

UVB radiation induces multiple types of DNA damage, including single-strand breaks, double-strand breaks, cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, and pyrimidine-(6-4)-pyrimidone photoproducts (Rajnochová Svobodová et al., 2013). We conducted comet assays to assess the protective effects of CGA against UVB-induced DNA breaks. Exposure of cells to UVB increased the number of DNA breaks, resulting in an increase in fluorescence intensity in the tails of the comet-like structures formed during the assay. In the absence of CGA, the percentage of total DNA fluorescence in the comet tails of UVB-irradiated cells was 74%, whereas CGA pre-treatment decreased this value to 30% (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the protective effect of CGA against UVB-induced DNA damage increased cell viability, from 55% in CGA-untreated cells to 68% in cells pre-treated with CGA (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

CGA protects cells against UVB-induced DNA damage. (A) DNA damage was assessed in an alkaline comet assay. Representative images and the percentage of total DNA fluorescence in the comet tails are shown. *Significantly different from control cells (p<0.05); #significantly different from UVB-irradiated cells (p<0.05). (B) HaCaT cells were treated with CGA. After 1 h, the cells were exposed to UVB radiation and cell viability was determined 20 h later in an MTT assay. *Significantly different from control cells (p<0.05); #significantly different from UVB-irradiated cells (p<0.05).

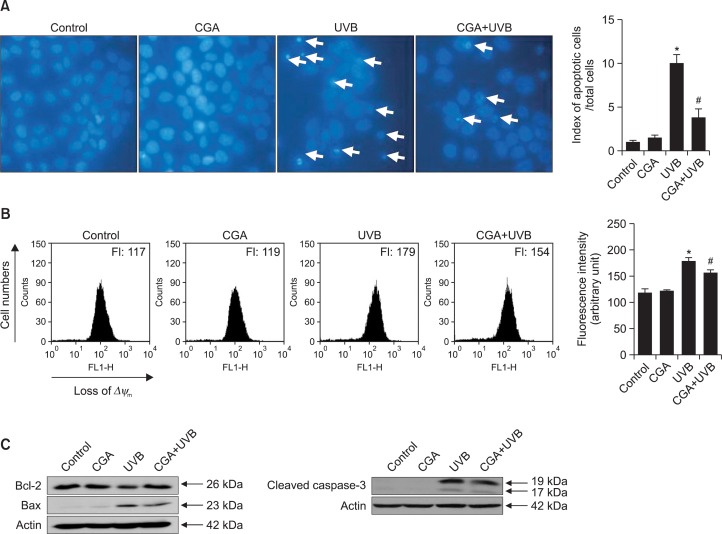

CGA suppresses UVB-induced apoptosis

UVB radiation triggers apoptosis in HaCaT keratinocytes (Jost et al., 2001). We observed intact nuclei in control cells and cells treated with CGA alone, but detected numerous apoptotic bodies (characteristic of apoptosis) in UVB-irradiated cells (apoptotic index: 11). By contrast, the number of apoptotic bodies was markedly reduced in UVB-irradiated cells that had been pre-treated with CGA (apoptotic index: 4) (Fig. 4A). Apoptosis triggers changes in mitochondrial membrane permeability and potential, and apoptosis-induced mitochondrial dysfunction can be detected by flow cytometry after JC-1 staining. The JC-1 fluorescence intensity was 179 in UVB-exposed cells, compared with 117 in non-irradiated control cells; pre-treatment with CGA decreased the intensity in UVB-exposed cells to 154 (Fig. 4B). Expression levels of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax and active caspase-3 were increased by UVB exposure, but these levels were reduced in cells pre-treated with CGA (Fig. 4C). By contrast, levels of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 expression decreased by UVB irradiation were elevated in UVB-irradiated cells that had been pre-treated with CGA (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

CGA protects cells against UVB-induced apoptosis. (A) Apoptotic bodies (arrows) were observed in cells stained with Hoechst 33342 dye by fluorescence microscopy and quantitated. *Significantly different from control (p<0.05); #significantly different from UVB-irradiated cells (p<0.05). (B) The mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) was assessed by flow cytometry after cells were stained with JC-1. *Significantly different from control cells (p<0.05); #significantly different from UVB-irradiated cells (p<0.05). (C) Cell lysates were subjected to electrophoresis, and Bcl-2 (26 kDa), Bax (23 kDa), and caspase-3 (17/19 kDa) were detected on immunoblots using appropriate antibodies. Actin was used to loading control.

DISCUSSION

Solar UV radiation can trigger erythema, hyperpigmentation, hyperplasia, immune suppression, photo-aging, and skin cancer (F’Guyer et al., 2003; Bowden, 2004; Matsumura and Ananthaswamy, 2004; Afaq et al., 2005; Halliday, 2005). UVB induces intracellular oxidative stress as well as apoptosis, and many studies report that various antioxidant agents protect cells against the UVB-induced damage (Jin et al., 2007).

CGA, an ester of caffeic acid and quinic acid, is one of the most abundant naturally existing phenolic compounds in many plant species (Kiehne and Engelhardt, 1996; Rice-Evans et al., 1996). CGA possesses antioxidant activity, e.g., the ability to scavenge DPPH free radicals (Wu, 2007). Our results confirmed and expanded these findings. CGA scavenged DPPH radicals in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B), and potently eliminated ROS such as superoxide anions and hydroxyl radicals (Fig. 1C, D). In addition, the DCF-DA assay (Fig. 1E) revealed that CGA also protected HaCaT keratinocytes against intracellular ROS generated as a result of H2O2 or UVB exposure.

The effect of UVB absorption is important to act as a protective agent about UVB radiation; for example, UVB absorbing ability of vitamin E compound may be a critical determinant of photoprotection (McVean and Liebler, 1999). Thus, we also determined the λmax of CGA to predict its ability to prevent UVB-mediated damage. As shown in Fig. 2, the absorbance maximum of CGA was approximately 325 nm, close to the UVB range (280–320 nm). Our UVB absorbance data of CGA was also consistent to the results of CGA from Lepidogrammitis drymoglossoides (Baker) Ching, showing the peak around the wavelength ranging from 315 nm to 335 nm (Wen et al., 2012).

UVB-induced cell death occurs via the generation of ROS. In many cell lineages in vitro, the resultant oxidative stress induces DNA damage, including DNA fragmentation, ultimately leading to apoptosis (Salucci et al., 2012). The results of the comet assays (Fig. 3A) demonstrated that CGA treatment reduced the amount of DNA breakage induced by UVB radiation. Specifically, the comet tail, which represents UVB-induced DNA strand breaks, was significantly shorter in CGA-treated cells. Such a protective effect against DNA damage is also shown in Fig. 4A. We then evaluated the ability of CGA to prevent cell death induced by UVB radiation; to this end, we monitored the levels of two pro-apoptotic markers, Bax and cleaved caspase-3, and an anti-apoptotic protein, Bcl-2. As shown in Fig. 4C, the level of Bcl-2 protein was increased in and cells pre-treated with CGA prior to UVB irradiation (combination group), whereas the levels of Bax and cleaved caspase-3 protein in the combination group was reduced.

Taken together, the findings reported herein show that CGA has potential antioxidant properties. Specifically, CGA can scavenge ROS such as DPPH, hydroxyl radicals, superoxide anions, and hydrogen peroxide, as well as protect cells against UVB-induced oxidative stress. UVB radiation causes photo-chemical damage to DNA (Ryter et al., 2007). In mammalian cells, UVB radiation induces mitochondrial dysfunction by potently suppressing transcription within the organelle (Vogt et al., 1997). Mitochondria have a sensitive redox system, and many studies suggest that the mitochondrial dysfunction resulting from oxidative stress could induce apoptosis (Zamzami et al., 1995, 1996; Green and Reed, 1998; Susin et al., 1998; Morel and Barouki, 1999). CGA gets involved in prevention of the disrupted mitochondria permeability potential from UVB-irradiated cell. The data reported herein show that CGA protects keratinocytes against UVB-induced oxidative stress. Because CGA shows absorbance in the UVB wavelength range and scavenges ROS, it prevents UVB-mediated oxidative stress in HaCaT cells. Thus, CGA could be used in products aimed at protecting against UVB-mediated skin diseases.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) and Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) through the Promoting Regional Specialized Industry.

REFERENCES

- Afaq F, Adhami VM, Mukhtar H. Photochemoprevention of ultraviolet B signaling and photocarcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2005;571:153–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7915–7922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden GT. Prevention of non-melanoma skin cancer by targeting ultraviolet-B-light signalling. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddeo C, Teskač K, Sinico C, Kristl J. Effect of resveratrol incorporated in liposomes on proliferation and UV-B protection of cells. Int J Pharm. 2008;363:183–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campanini MZ, Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Ivan AL, Ferreira VS, Vilela FM, Vicentini FT, Martinez RM, Zarpelon AC, Fonseca MJ, Faria TJ, Baracat MM, Verri WA, Georgetti SR, Casagrande R. Efficacy of topical formulations containing Pimenta pseudocaryophyllus extract against UVB-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in hairless mice. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2013;127:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael J, DeGraff WG, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, Mitchell JB. Evaluation of a tetrazolium-based semiautomated colorimetric assay: assessment of chemosensitivity testing. Cancer Res. 1987;47:936–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhumrongvaraporn A, Chanvorachote P. Kinetics of ultraviolet B irradiation-mediated reactive oxygen species generation in human keratinocytes. J Cosmet Sci. 2013;64:207–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng R, Lu Y, Bowman LL, Qian Y, Castrannova V, Ding M. Inhibition of activator protein-1, NF-κB, and MAPKs and induction of phase 2 detoxifying enzyme activity by chlorogenic acid. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:27888–27895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino A, D’Abrosca B, Pacifico S, Mastellone C, Piscopo V, Caputo R, Monaco P. Isolation and structure elucidation of antioxidant polyphenols from quince (Cydonia vulgaris) peels. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:2660–2667. doi: 10.1021/jf800059r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- F’Guyer S, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Photochemoprevention of skin cancer by botanical agents. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:56–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DR, Reed JC. Mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 1998;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday GM. Inflammation, gene mutation and photoimmunosuppression in response to UVR-induced oxidative damage contributes to photocarcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2005;571:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin GH, Liu Y, Jin SZ, Liu XD, Liu SZ. UVB induced oxidative stress in human keratinocytes and protective effect of antioxidant agents. Radiat Environ Biophys. 2007;46:61–68. doi: 10.1007/s00411-007-0096-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jost M, Gasparro FP, Jensen PJ, Rodeck U. Keratinocyte apoptosis induced by ultraviolet B radiation and CD95 ligation - differential protection through epidermal growth factor receptor activation and Bcl-xL expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:860–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karol MH. How environmental agents influence the aging process. Biomol Ther. 2009;17:113–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kiehne A, Engelhardt UH. Thermospray-LC-MS analysis of various groups of polyphenols in tea. II: Chlorogenic acids, theaflavins and thearubigins. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch. 1996;202:299–302. doi: 10.1007/BF01206100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa S, Yoshii K, Morita S, Teraoka R. Efficient topical delivery of chlorogenic acid by an oil-in-water microemulsion to protect skin against UV-induced skin damage. Chem Pharm Bull. 2011;59:793–796. doi: 10.1248/cpb.59.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CW, Ko HH, Lin CC, Chai CY, Chen WT, Yen FL. Artocarpin attenuates ultraviolet B-induced skin damage in hairless mice by antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect. Food Chem Toxicol. 2013;60:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2013.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Kim JS, Kim HP, Lee J, Kang SS. Phenolic constituents from the flower buds of Lonicera japonica and their 5-lipoxygenase inhibitory activities. Food Chem. 2010;120:134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Abe Y, Mashino T, Mochizuki M, Miyata N. Signal enhancement in ESR spin-trapping for hydroxyl radicals. Anal Sci. 2003;19:1083–1084. doi: 10.2116/analsci.19.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Abe Y, Kanagawa K, Usui N, Imai K, Mashino T, Mochizuki M, Miyata N. Distinguishing the 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO)-OH radical quenching effect from the hydroxyl radical scavenging effect in the ESR spin-trapping method. Anal Chim Acta. 2004;512:121–124. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Bian H, Liu Z, Wang Y, Dai J, He W, Liao X, Liu R, Luo J. Chlorogenic acid protects MSCs against oxidative stress by altering FOXO family genes and activating intrinsic pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;674:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura Y, Ananthaswamy HN. Toxic effects of ultraviolet radiation on the skin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;195:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne ST. Antioxidant nutrients and chronic disease: use of biomarkers of exposure and oxidative stress status in epidemiologic research. J Nutr. 2003;133:933S–940S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.3.933S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVean M, Liebler DC. Prevention of DNA photodamage by vitamin E compounds and sunscreens: roles of ultraviolet absorbance and cellular uptake. Mol Carcinog. 1999;24:169–176. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(199903)24:3<169::aid-mc3>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel Y, Barouki R. Repression of gene expression by oxidative stress. Biochem J. 1999;342:481–496. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan DL, Saladi RN, Fox JL. Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:978–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganga G, Miller N, Rice-Evans CA. The polyphenolic content of fruit and vegetables and their antioxidant activities. What does a serving constitute? Free Radic Res. 1999;30:153–162. doi: 10.1080/10715769900300161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park HM, Kim HJ, Jang YP, Kim SY. Direct analysis in real time mass spectrometry (DART-MS) analysis of skin metabolome changes in the ultraviolet B-induced mice. BiomolTher. 2013;21:470–475. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2013.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan R, Ranjan SK, Nair CK. Effect of vinblastine sulfate on gamma-radiation-induced DNA single-strand breaks in murine tissues. Mutat Res. 2003;536:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(03)00015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajnochová Svobodová AR, Galandáková A, Palíková I, Doležal D, Kylarová D, Ulrichová J, Vostálová J. Effects of oral administration of Lonicera caerulea berries on UVB-induced damage in SKH-1 mice. A pilot study. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2013;12:1830–1840. doi: 10.1039/c3pp50120e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G. Structure-anti-oxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:933–956. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkranz AR, Schmaldienst S, Stuhlmeier KM, Chen W, Knapp W, Zlabinger GJ. A microplate assay for the detection of oxidative products using 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin-diacetate. J Immunol Methods. 1992;156:39–45. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90008-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryter SW, Kim HP, Hoetzel A, Park JW, Nakahira K, Wang X, Choi AM. Mechanisms of cell death in oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:49–89. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.9.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salucci S, Burattini S, Battistelli M, Baldassarri V, Maltarello MC, Falcieri E. Ultraviolet B (UVB) irradiation-induced apoptosis in various cell lineages in vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;14:532–546. doi: 10.3390/ijms14010532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sime S, Reeve VE. Protection from inflammation, immunosuppression and carcinogenesis induced by UV radiation in mice by topical Pycnogenol®. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;79:193–198. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2004)079<0193:pfiiac>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh NP. Microgels for estimation of DNA strand breaks, DNA protein crosslinks and apoptosis. Mutat Res. 2000;455:111–127. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar LR, Almutawa F, Lim HW, Hamzavi I. Effects of ultraviolet radiation, visible light, and infrared radiation on erythema and pigmentation: a review. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2013;12:54–64. doi: 10.1039/c2pp25152c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susin SA, Zamzami N, Kroemer G. Mitochondria as regulators of apoptosis: doubt no more. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1366:151–165. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiano L, Ferraresi R, Lugli E, Nemes E, Roat E, Nasi M, Pinti M, Cossarizza A. Multiparametric analysis of cells with different mitochondrial membrane potential during apoptosis by polychromatic flow cytometry. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2719–2727. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vayalil PK, Elmets CA, Katiyar SK. Treatment of green tea polyphenols in hydrophilic cream prevents UVB-induced oxidation of lipids and proteins, depletion of antioxidant enzymes and phosphorylation of MAPK proteins in SKH-1 hairless mouse skin. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:927–936. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt TM, Welsh J, Stolz W, Kullmann F, Jung B, Landthaler M, McClelland M. RNA fingerprinting displays UVB-specific disruption of transcriptional control in human melanocytes. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3554–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen J, Kang L, Liu H, Xiao Y, Zhang X, Chen Y. A validated UV-HPLC method for determination of chlorogenic acid in Lepidogrammitis drymoglossoides (Baker) Ching, Polypodiaceae. Pharmacognosy Res. 2012;4:148–153. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.99076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. Effect of chlorogenic acid on antioxidant activity of Flos Lonicerae extracts. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2007;8:673–679. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2007.B0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamzami N, Marchetti P, Castedo M, Decaudin D, Macho A, Hirsch T, Susin SA, Petit PX, Mignotte B, Kroemer G. Sequential reduction of mitochondrial transmembrane potential and generation of reactive oxygen species in early programmed cell death. J Exp Med. 1995;182:367–377. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamzami N, Susin SA, Marchetti P, Hirsch T, Gómez-Monterrey I, Castedo M, Kroemer G. Mitochondrial control of nuclear apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1533–1544. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]