Abstract

We present a 32-year-old female patient with fulminant neuromyelitis optica. After the initial treatment with the monoclonal antibody rituximab failed, therapy with the anti-IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab was initiated. The patient experienced a clinically relevant improvement from severe tetraparesis to low-grade paresis, which is still maintained. On MRI of the spinal cord an almost complete restitution of a predescribed extensive myelopathy accompanied this clinical improvement. Meanwhile clinical stability was achieved for over 1 year without any side effects of the ongoing treatment with tocilizumab.

Background

Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) is an autoimmune-mediated, usually relapsing disease of the central nervous system (CNS) that is characterised by bilateral severe opticus neuritis and longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions.1 With the establishment of a biomarker, the detection of antibodies against the water channel aquaporin-4 (anti-AQP4-Abs), diagnosis of NMO became easier, which has been implemented in the revised diagnostic criteria.2

The acute clinical exacerbation in NMO is usually treated with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP). In case of insufficient treatment response to IVMP plasmapheresis can be considered.3 For immunoprophylaxis, azathioprine and mitoxantrone have frequently been used in daily practice.4 5 In recent years the monoclonal antibody rituximab, targeting B lymphocytes expressing CD20, has successfully been implemented based on its clinical efficacy as well as safety.6

Therapies commonly used in multiple sclerosis (MS), such as interferon-β or natalizumab, however, often remain ineffective and may exhibit negative effects on disease activity.4 7–9

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a proinflammatory cytokine produced by various lymphocytes, including B cells and T cells. Increased IL-6 levels in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) observed in patients with NMO provide indirect evidence of its potential pathogenic role in this disease. In addition, it may increase the secretion of anti-AQP4-Abs.10 Thus, this emerging evidence provides a scientific rationale for using IL-6 as a therapeutic target in NMO. The humanised monoclonal antibody tocilizumab is an IL-6 receptor antagonist, which gained approval for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). It prevents the binding of IL-6 to its soluble and membrane-bound receptor.11 Here we describe a patient with NMO treated with tocilizumab.

Case presentation

A 32-year-old female patient presented in 2003 for the first time with numbness and dysaesthesia. The symptoms were transient and resolved spontaneously. Sensory disturbances occurred again in June as well as in December 2004. MRI of the spinal cord revealed circumscribed demyelinating lesions, whereas cranial MRI (cMRI) was normal. CSF examination revealed a low lymphocytic pleocytosis; oligoclonal bands were negative. The patient was treated with IVMP and recovered completely; immunoprophylaxis was not initiated at that time point.

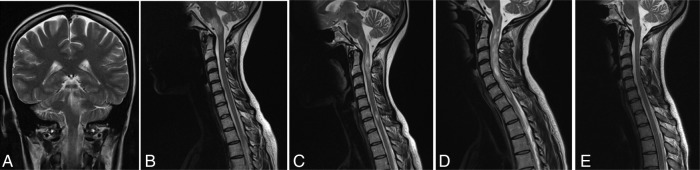

After years of clinical stability a new attack presenting as bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia, crossed brainstem symptoms, nausea and intractable hiccups occurred in January 2010. The cMRI revealed a cerebellar lesion with extension to the pons and the medulla oblongata (see figure 1A). Only after repeatedly performing IVMP was there a slow improvement of symptoms. Six months later, the patient presented with a relapse consisting of nausea, hiccups, diplopia and nystagmus. A newly occurring T2 hyperintense lesion was detected on MRI that affected almost the entire cross-section of the medulla oblongata and the pons (see figure 1B). In the same year further relapses followed with sensory disturbances and circumscribed spinal lesions. Anti-AQP4-Abs in serum were negative. Because of the severe disease activity, treatment with natalizumab was initiated in November 2010, based on the idea that this was aggressive relapsing-remitting MS. Initially, clinical stability could be achieved. However, in May 2012 while being treated with natalizumab, inflammatory attacks affecting the spinal cord were observed repeatedly (see figure 1C), initially presenting with dysaesthesia in the left half of the body, followed by numbness of the right half of the body, with only poor remission despite IVMP; plasmapheresis led to clinical amelioration. Because of the predominant disease activity within the spinal cord, the presence of anti-AQP4-Abs was re-assessed and found to be positive. At that time MRI revealed longitudinal spinal lesions, thus, the diagnosis of NMO was made. Natalizumab was stopped and treatment with rituximab was initiated in September 2012. Despite a complete depletion of CD20+B-lymphocytes in the peripheral venous blood, another relapse with a severe clinical deterioration on the EDSS (Expanded Disability Status Scale) from 6.0 to 9.0 occurred 4 weeks after treatment initiation with rituximab. Spinal cord MRI showed an extensive myelopathy from cervical vertebra 1 to 7 (see figure 1D).

Figure 1.

(A) Cranial MRI in January 2010 revealed lesion of the periaqueductal grey with extension to the left cerebellar hemisphere as well as to the pons and the medulla oblongata on T2-weighted images, after a new attack presenting as bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia, crossed brainstem symptoms, nausea and intractable hiccups. (B) Spinal MRI in July 2010 showed a newly occurred T2 hyperintense lesion that affected almost the entire cross-section of the medulla oblongata and the pons, causative for a new relapse with brainstem symptoms. (C) T2-weighted spinal cord MRI in July 2012, when the patient presented with sensory disturbances, revealed multiple circumscribed hyperintense lesions, the cranial one extending over two vertebral segments. (D) Spinal cord MRI in October 2012 after a severe clinical deterioration to an Expanded Disability Status Scale of 9 demonstrated an extensive myelopathy from cervical vertebra 1 to 7. (E) MRI in August 2013 showed an almost complete restitution of the previously described myelopathy on T2-weighted images, after 10 months treated with tocilizumab.

Treatment

After high-dose IVMP and plasmapheresis, treatment with the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab was initiated. The patient receives tocilizumab (8 mg/kg body weight) intravenous monthly.

Outcome and follow-up

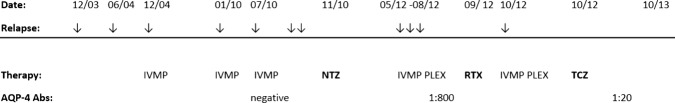

Within 8 weeks the patient regained ability to walk without assistance. Meanwhile, after more than a year of therapy there is tremendous clinical improvement from a prior severe tetraparesis (EDSS: 9.0) to a currently low-grade paresis with unrestricted walking distance (EDSS: 2.5). The infusions are tolerated without side effects. A follow-up MRI in August 2013 showed an almost complete restitution of the previously described myelopathy (see figure 1E). The anti-AQP4-Ab titre dropped from the initial 1 : 800 down to 1 : 20 (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical course and concomitant drugs.NTZ: natalizumab 300 mg monthly; PLEX: plasmaexchange; RTX: rituximab 2×1000 mg; TCZ: tocilizumab 8 mg/kg body weight monthly.

Discussion

Here we present a patient with highly active NMO despite immunosuppression with rituximab. Changing the treatment regimen to tocilizumab, in contrast, stopped disease activity and even induced clinical improvement. This very positive clinical observation in the light of few other case reports points to the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab as an alternative effective therapeutic option in NMO.12 13

It is of interest that in our case the diagnosis of NMO could not be established in the beginning. Anti-AQP4-Ab positivity, however, is not a prerequisite to fulfil the diagnostic critieria2 as such a negative antibody report should not pre-exclude this diagnosis. The decrease of antibody titres, as seen in our case, is, however, not surprising, since IL-6 was shown to enhance the survival of anti-AQP4-Ab secreting B cells.10

Our case, in addition, supports the notion that natalizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the α4 integrin involved in T cell egress out of the bloodstream into the CNS, failed to exhibit clinical efficacy. This is in line with previous reports8 9 and supports the notion that the pathogenesis of spinal cord inflammation is, at least based on current experimental evidence, mediated independently of the α4 integrin.14

It remains to be established whether IL-6 plays a central role in the pathogenesis of NMO. Recently published data on the clinical efficacy of complement neutralisation by the monoclonal antibody eculizumab stress the critical role of autoantibodies in NMO and NMO spectrum diseases (NMOSD).15 However, the good clinical experience gathered in RA clearly supports the need to explore tocilizumab as a treatment in NMO in greater detail.

Learning points.

In cases of predominantly inflammatory lesions in the spinal cord neuromyelitis optica (NMO) or NMO spectrum diseases must be considered.

The lack of anti-AQP4-Abs (antibodies against the water channel aquaporin-4) in serum does not pre-exclude the diagnosis of NMO.

Interleukin-6 receptor antagonists may represent therapeutic options in the treatment of NMO.

Natalizumab may not be effective in patients with NMO.

Footnotes

Contributors: A-SL was involved in drafting of the manuscript and approved the final version. MS was involved in critical revision of manuscript and approved the final version. BCK and EL were involved in drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bukhari W, Barnett MH, Prain K, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of neuromyelitis optica. Int J Mol Sci 2012;13:12970–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, et al. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2006;66:1485–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SH, Kim W, Huh SY, et al. Clinical efficacy of plasmapheresis in patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder and effects on circulating anti-aquaporin-4 antibody levels. J Clin Neurol Seoul Korea 2013;9:36–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okamoto T, Ogawa M, Lin Y, et al. Treatment of neuromyelitis optica: current debate. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2008;1:5–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstock-Guttman B, Ramanathan M, Lincoff N, et al. Study of mitoxantrone for the treatment of recurrent neuromyelitis optica (Devic disease). Arch Neurol 2006;63:957–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cree BAC, Lamb S, Morgan K, et al. An open label study of the effects of rituximab in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2005;64:1270–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimizu Y, Yokoyama K, Misu T, et al. Development of extensive brain lesions following interferon beta therapy in relapsing neuromyelitis optica and longitudinally extensive myelitis. J Neurol 2008;255:305–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleiter I, Hellwig K, Berthele A, et al. Failure of natalizumab to prevent relapses in neuromyelitis optica. Arch Neurol 2012;69:239–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacob A, Hutchinson M, Elsone L, et al. Does natalizumab therapy worsen neuromyelitis optica? Neurology 2012;79:1065–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chihara N, Aranami T, Sato W, et al. Interleukin 6 signaling promotes anti-aquaporin 4 autoantibody production from plasmablasts in neuromyelitis optica. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:3701–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkiteshwaran A. Tocilizumab. MAbs 2009;1:432–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araki M, Aranami T, Matsuoka T, et al. Clinical improvement in a patient with neuromyelitis optica following therapy with the anti-IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody tocilizumab. Mod Rheumatol Jpn Rheum Assoc 2013;23:827–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kieseier BC, Stüve O, Dehmel T, et al. Disease amelioration with tocilizumab in a treatment-resistant patient with neuromyelitis optica: implication for cellular immune responses. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:390–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothhammer V, Heink S, Petermann F, et al. Th17 lymphocytes traffic to the central nervous system independently of α4 integrin expression during EAE. J Exp Med 2011;208:2465–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pittock SJ, Lennon VA, McKeon A, et al. Eculizumab in AQP4-IgG-positive relapsing neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders: an open-label pilot study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:554–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]