Abstract

Two young women with completely dry and keratinised eyes post-Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) underwent unilateral oral mucous membrane grafts (MMGs) in preparation for modified osteo-odonto keratoprosthesis (MOOKP) implantation. In both cases, the mucosal graft was deemed to be too tight to accommodate the MOOKP implant. Instead of proceeding with MOOKP, the first patient underwent Auro Kpro (Boston type 1-based keratoprosthesis) implantation under the MMG, while the second patient underwent implantation of a modification of Auro Kpro with a longer optical stem (LVP Kpro) exposed through the MMG. Both patients maintained a visual acuity of 20/20, N6 at 15 months post-implantation. The first patient needed repeated mucosal trimming because of mucosal overgrowth; while in the second patient, mucosal overgrowth did not occur. This report highlights the innovative and successful use of Boston type 1-based keratoprosthesis (Auro Kpro) and its modification (LVP Kpro) in completely dry and keratinised post-SJS eyes.

Background

Management of corneal blindness because of completely dry and keratinised ocular surfaces in post-Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) eyes is extremely challenging. Conventional options like keratoplasty, limbal stem cell transplantation or Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis implantation seldom work in this scenario primarily because of the hostile nature of the ocular surface environment. The current treatment options include the modified osteo-odonto keratoprosthesis (MOOKP)1 or the Boston type 2 keratoprosthesis,2 each having their own limitations.2 3 This report highlights the innovative and successful use of Boston type 1 design-based keratoprosthesis (Auro Kpro, AuroLab, Madurai, India) and its modification (LVP Kpro) under an oral mucous membrane graft (MMG) in such severely diseased blind eyes.

Case presentation, treatment and outcome

Case 1

A 19-year-old girl presented to our clinic in April 2011. She had a history of SJS following intake of some unknown medication in 2007. She had previously undergone penetrating keratoplasty (PK) and tarsorrhaphy in her right eye, which was unsuccessful. The right eye had become phthisical with no perception of light. The left eye had undergone unsuccessful ocular surface reconstruction with amniotic membrane transplantation and an upper lid-MMG. Her vision in the left eye was hand movements with accurate projection of rays. The entire ocular surface of the left eye was completely dry and keratinised. Initially, MOOKP was planned in the left eye for visual rehabilitation. Stage 1 of MOOKP3 including total iridectomy, intracapsular cataract extraction and anterior vitrectomy was performed in December 2011. Intraoperative fundus evaluation revealed a healthy disc and retina. Stage 2 of MOOKP was performed in January 2012, where an autologous oral MMG was sutured on the ocular surface.3 Postoperatively, the mucosa showed a tight-fit on the eye with little redundancy and shallow fornices. This was deemed to be at high risk of developing mucosal necrosis following MOOKP implantation.3 As an alternative, in March 2012, she underwent Auro Kpro implantation after lifting of the oral mucosal flap and corneal exposure. The Auro Kpro is based on the Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis design and consists of an optical cylinder, fenestrated back-plate and titanium locking ring, but is manufactured locally in India. After Auro Kpro implantation, the mucosal flap was reposited and sutured to the edges of its cut-margins and a central 6 mm opening was made in the mucosa overlying the front plate of the Auro Kpro. Postoperatively, the patient's best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) improved to 20/100 at 1 week and 20/20 at 1 month (figure 1A). However, she developed mucosal overgrowth, covering the front-plate of the keratoprosthesis (figure 1B). She underwent mucosal trimming five times over the course of the next 14 months. She was last seen in June 2013 and maintained BCVA of 20/20, N6 with a healthy optic nerve (figure 1C).

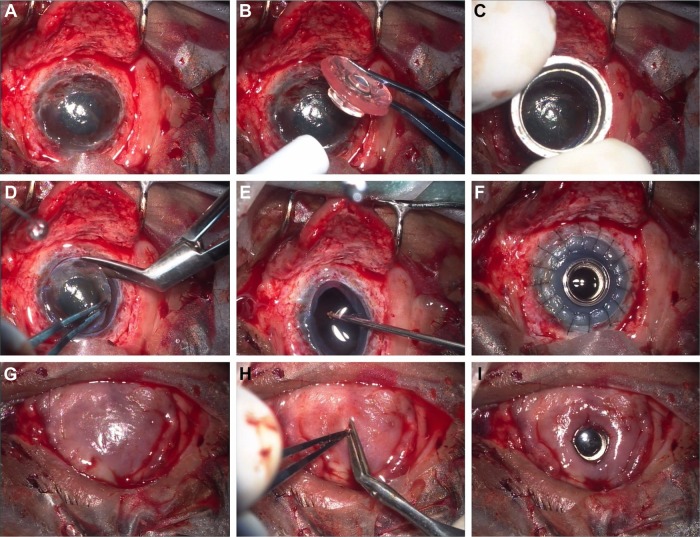

Figure 1.

Postoperative clinical photographs of the left and right eyes of cases 1 and 2, respectively. (A) The left eye of case 1, 1-month postoperatively shows adequate exposure of the front-plate of the Auro Kpro through the central opening in the oral mucous membrane graft (MMG). (B) Three months after implantation, the patient presented with mucosal overgrowth over the optical cylinder. (C) At 15-month post-implantation, the left eye of case 1 shows a stable mucosal surface with adequate central opening after having undergone five mucosal trimming procedures. (D) Right eye of case 2, 1-week post-implantation shows adequate exposure of the optical cylinder through the MMG, whose edges are tucked under the front-plate. (E) At 1-month post-implantation. At 15 months post-implantation. (F) The MMG is stable without any overgrowth over the front plate.

Case 2

A 28-year-old woman presented to us in February 2012, 16 months after recovering from SJS following chicken pox infection. At presentation, she had trichiasis, shallow fornices and keratinised ocular surfaces in both eyes. BCVA in both eyes was light perception with accurate projection of rays. As in the previous case, the patient underwent stages 1 and 2 of MOOKP in the right eye in March and May 2012, respectively. In this case, an adequately sized MMG could not be harvested because of extensive labial and buccal keratinisation. This resulted in a tightly fitted MMG on the ocular surface. Taking cues from the first case we decided to modify the original Auro Kpro design and increase the optical cylinder length such that it extended 0.75 mm beyond the surface of the carrier corneal graft (figure 2). This modification of the Auro Kpro design was named LVP Kpro. This modification was done so that the edges of the mucosal graft around the central opening could be tucked under the front-plate, thus preventing recurrent mucosal overgrowth (figure 3). This procedure was performed in June 2012. Her BCVA improved to 20/60 at 1 week (figure 1D) and 20/20 at 1 month postoperatively (figure 1E). She continued to maintain BCVA of 20/20, N6 with healthy optic discs for the next 14 months. She was last seen in September 2013 and mucosal overgrowth did not occur in this case (figure 1F).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram showing the structural difference between the Boston type 1-based keratoprosthesis (Auro Kpro, left) and its modification (LVP Kpro, right). The increased length of the optical stem of the LVP Kpro by 0.75 mm allows the front-plate to project beyond the surface of the carrier corneal graft to accommodate the mucous membrane graft.

Figure 3.

Representative intraoperative photographs illustrating the surgical technique of LVP Kpro implantation. The mucosal flap is lifted and the cornea is exposed (A); the keratoprosthesis is assembled using an appropriately sized donor corneal graft (B); the recipient cornea is trephined (C) and the host corneal button is excised using corneal scissors (D); open-sky anterior vitrectomy is performed (E); the assembled keratoprosthesis is sutured into place (F); the mucosal flap is reposed and sutured to the cut margins (G); a central opening is made in the mucosa overlying the optical cylinder (H); the edges of the mucosal opening are tucked under the front-plate of the LVP Kpro utilising the gap between the front-plate and the carrier cornea.

Discussion

The Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis is currently the most commonly implanted keratoprosthesis around the world.4 The surgical technique is simple and recent improvements in the design and postoperative care regimen have significantly improved the long-term outcomes.5 However, the device is not recommended in tear-deficient eyes postautoimmune diseases like SJS because of the high likelihood of postoperative epithelial breakdown and stromal melting in the carrier donor cornea. In this report, we describe the use of oral MMG to provide a stable epithelial cover for the Boston type 1-based keratoprosthesis in such severely damaged eyes. The drawback of such an approach seems to be the risk of the mucosa overgrowing the optical cylinder and obscuring vision. This can be addressed either by repeated mucosal trimming or by using a modification of the type 1 design with a slightly longer optical stem (LVP Kpro). The longer stem allows the mucosa to remain tucked under the front-plate of the optical cylinder.

The strongest concern we had with the use of MMG was that of intraocular migration of mucosal epithelium along the optical stem of the keratoprosthesis leading to fistula formation, aqueous leak, endophthalmitis or extrusion. However, this did not happen in at least the first 15 months of follow-up. The other concern in any keratoprosthesis is the risk of glaucoma. In both these cases, a complete iridectomy was performed in preparation for MOOKP. It has been hypothesised that cyclo-dialysis clefts created during iridectomy may inadvertently provide an additional channel for aqueous drainage and prevent glaucoma. The absence of peripheral iris tissue may also help by preventing anterior synechiae formation and secondary angle-closure, which is presumed to be one of the mechanisms of glaucoma in the Boston type 1 keratoprosthesis.

If either or both of these approaches continue to be effective in the longer-term, they could turn out to be superior alternatives to the MOOKP and Boston type 2 designs. Management of postoperative intraocular complications such as retinal detachment or glaucoma is challenging in MOOKP and Boston type 2 implanted eyes due to the altered ocular anatomy. However, implanting a glaucoma drainage valve or making vitrectomy ports will be comparatively simpler through the MMG. It may even be possible to insert a trochar directly through the mucosa and perform a 23 or 25g pars plana vitrectomy without needing to expose the sclera. Additional advantages for the patients would be the ability to close the lids and even wear an ocular prosthesis over the mucosa for better cosmetic results. It may even be possible to implant the LVP Kpro under the existing ocular surface pannus (in SJS or ocular burns) or cover the donor cornea with a conjunctival-Tenon's flap (ocular burns with poor lid closure or shallow fornices) without needing a prior MMG. Either of the approaches may also be useful in MOOKP-implanted eyes that present with extrusion of the prosthesis. Furthermore, these novel approaches can be useful in children with chronic SJS-related blindness, in whom MOOKP is not possible.

The science of keratoprosthesis is in constant evolution, and active research is ongoing in pursuit of the ideal device. This report highlights the possibility of using Boston type 1-based keratoprosthesis (Auro Kpro) or its modification (LVP Kpro) under the cover of MMG in treatment of completely dry eyes post-SJS. Although long-term outcomes of these approaches are awaited, survival for more than a year without surface breakdown, infection, extrusion or glaucoma is quite encouraging in itself.

Learning points.

An oral mucous membrane graft (MMG) can provide a stable epithelial surface under which a Boston type 1 design-based keratoprosthesis can be implanted in completely dry post-Stevens Johnson Syndrome (SJS) eyes.

Mucosal overgrowth is a problem with such an approach, and can be tackled by either performing repeated mucosal trimming or using a modified Boston type 1-based keratoprosthesis with a longer optical stem (LVP Kpro).

Both approaches are viable and can serve as alternatives to the modified osteo-odonto keratoprosthesis and Boston type 2 keratoprosthesis in such severe cases.

These innovative approaches can relatively simplify the management of corneal blindness in completely dry post-SJS eyes.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have substantially contributed to the conception of this work and to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work; and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Falcinelli G, Falsini B, Taloni M, et al. Modified osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis for treatment of corneal blindness: long-term anatomical and functional outcomes in 181 cases. Arch Ophthalmol 2005;123:1319–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pujari S, Siddique SS, Dohlman CH, et al. The Boston keratoprosthesis type II: the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary experience. Cornea 2011;30:1298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basu S, Pillai VS, Sangwan VS. Mucosal complications of modified osteo-odonto keratoprosthesis in chronic Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:867–873.e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aldave AJ, Sangwan VS, Basu S, et al. International results with the Boston type I keratoprosthesis. Ophthalmology 2012;119:1530–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traish AS, Chodosh J. Expanding application of the Boston type I keratoprosthesis due to advances in design and improved post-operative therapeutic strategies. Semin Ophthalmol 2010;25:239–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]