Summary

Background

The prevalence of overweight/obesity, which is an important cardiovascular risk factor, is rapidly increasing worldwide. Abdominal obesity, a fundamental component of the metabolic syndrome, is not defined by appropriate cutoff points for sub-Saharan Africa.

Objective

To provide baseline and reference data on the anthropometry/body composition and the prevalence rates of obesity types and levels in the adult urban population of Kinshasa, DRC, Central Africa.

Methods

During this cross-sectional study carried out within a random sample of adults in Kinshasa town, body mass index, waist circumference and fatty mass were measured using standard methods. Their reference and local thresholds (cut-off points) were compared with those of WHO, NCEP and IFD to define the types and levels of obesity in the population.

Results

From this sample of 11 511 subjects (5 676 men and 5 835 women), the men presented with similar body mass index and fatty mass values to those of the women, but higher waist measurements. The international thresholds overestimated the prevalence of denutrition, but underscored that of general and abdominal obesity. The two types of obesity were more prevalent among women than men when using both international and local thresholds. Body mass index was negatively associated with age; but abdominal obesity was more frequent before 20 years of age and between 40 and 60 years old. Local thresholds of body mass index (≥ 23, ≥ 27 and ≥ 30 kg/m2) and waist measurement (≥ 80, ≥ 90 and ≥ 94 cm) defined epidemic rates of overweight/general obesity (52%) and abdominal obesity (40.9%). The threshold of waist circumference ≥ 94 cm (90th percentile) corresponding to the threshold of the body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2 (90th percentile) was proposed as the specific threshold of definition of the metabolic syndrome, without reference to gender, for the cities of sub-Saharan Africa.

Conclusion

Further studies are required to define the optimal threshold of waist circumference in rural settings. The present local cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference could be appropriate for the identification of Africans at risk of obesity-related disorders, and indicate the need to implement interventions to reverse increasing levels of obesity.

Summary

According to experts at the World Health Organisation (WHO), general obesity-related, cardiometabolic and cancerous morbidity and mortality are major health problems worldwide.1-10 The obesity−diabetes mellitus epidemic (diabesity) clusters with other bioclinical disorders in defining the metabolic syndrome according to ethnicity.3,4 Because of globalisation, the obesity epidemic is no longer an issue of only developed countries.8 Indeed, WHO reports one billion and 300 thousand overweight and clinically obese subjects, respectively, throughout the world.10 The obesity epidemic is therefore extending to developing countries.9,10

However, in developing countries of sub-Saharan Africa such as the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), it is to some extent difficult to define obesity. The sub-Saharan African socio-cultural context and the HIV/AIDS epidemic favour a misconception about abdominal obesity, as it is considered a social achievement,11 and lack of HIV disease (stigmatisation). The present data on general obesity is based on the body mass index (BMI) > 28 kg/m2 cut-off point.12 It is therefore urgent to define overall and abdominal obesities using relevant and specific reference values3 in central Africans with increasing urbanisation, acculturation, westernisation, epidemiological, demographic and nutrition transitions.8,13-17 The consequence of these transforming processes is lifestyle changes, including physical inactivity and excessive intakes of saturated fats, alcohol and refined sugar.14,18 The use of relevant values of reference19 and international cut-off points of waist circumference (WC) and BMI20-22 might render an easier definition of the metabolic syndrome in Africans compared to other populations of the world.

This study sought to provide baseline and reference data on nutritional status and to determine prevalence of overall and abdominal obesities in sub-Saharan Africa, in comparison with international cut-off points, gender, age and cardiometabolic risk factors. As nutritional assessments need to be updated frequently, we also evaluated the trend of overall obesity in comparison with earlier reports.12

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study involved 11 511 apparently healthy adult Africans (15 years and older) randomly selected from five geographic sites of Kinshasa (eastern, western, northern, southern and central parts), the capital of DRC, with seven million inhabitants. Selection was done by multi-stage sampling. In each geographic site, a number of quarters was randomly selected according to the population size (unpublished data of Kinshasa town): Pascal, Saint Theresa Square and Kingasani ya suka for the eastern part; Rond Point Victoire Square for the central part; Kintambo Magasin and Rond Point Kinsuka for the part; Rond Point Ngaba and Kinshasa University campus for the southern part. In the selected quarters, one street was then selected and adults of randomly selected households were invited to participate in the study.

Permission for the study was obtained from the supervising department of Kinshasa. In each quarter, the local administration gave its consent and explained the nature of the study to all residents. All the participants recruited gave their verbal consent according to the Helsinki Declaration II. The study was approved by the research and ethics committee of Kinshasa University.

Data were collected from 2 to 29 September 2002. Gender and ages were filled in by the principal investigator (KLJB) according to identity cards. Body weight was recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg using an electronic beam balance scale, with the participants wearing light indoor clothing and no shoes. Height was measured to the nearest 1 mm using a standardised wall-mounted height board. Waist circumference (WC) was measured to the nearest 1 mm at the level of the umbilicus and the superior iliac crest, at the end of normal expiration, using a non-extensible and flexible tape on subjects in a standing position. Measurements were made on a flat surface, with the weighing scale regularly calibrated before use and securely positioned on the floor. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the body weight (kg) divided by the height squared (m2).

International cut-off points of nutritional status

The cut-off points of BMI established by WHO21 defined denutrition/underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal nutritional status (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overall overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2), and overall obesity (≥ 30 kg/m2). The degree of overall obesity was also quantified: grade (rank) I (30–34.9 kg/m2) grade II (35–39.9 kg/m2), grade III (≥ 40 kg/m2).

Abdominal (visceral) obesity was defined according to ATP III thresholds (≥ 102 cm for men and ≥ 88 cm for women)22 and the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) for Europid and other multiracial cut-off points (≥ 94 cm for men and ≥ 80 cm for women) (available from http://www.idf.org/webdata/docs/Metabolic_syndrom_definition.pdf).

The body composition for each participant included the total body water (TBW) calculated by the regression equation of Mellits and Check25 from deuterium oxide measurements [TBW in litres = 210.313 1 0.252 (weight in kg) 1 0.154 (height in cm) when ≥ 110 cm]; the lean body mass (LBM) in kg was derived from the method of Pace and Rathbun26 [LBM in kg = 0.72 (weight in kg)], and the body fat mass (BFM = body weight in kg 2 LBM in kg).

Sub-Saharan Africa-specific thresholds for anthropometry

The local percentiles, reference limits (2.5 and 97.5 percentiles), the 0.90 confidence interval (CI) of the reference limits (lower CI limit = percent limit 22.81 3 SD/√n for Gaussian distribution; lower CI limit = e-0.573 and upper CI limit = e-0.483 following logarithmic transformation for non-Gaussian distribution), the quartiles (QI−IV), and the tertiles (TI-III) of the nutritional/body composition data were calculated.

The disorders of the nutritional status/body composition were established for both men and women (similar values of weight and body fat mass) from the normal values (2.5–97.5th percentiles), the population-based reference values (reference limits), the interquartile range (25–75th percentiles), the 2.5–50th percentile range and the tertile I of the measurements. Thus, following local and appropriate cut-off points, we defined Africa-specific nutritional disorders as: underweight/denutrition (< 2.5th percentile of BMI, WC, BFM), normal nutritional status (the range between 2.5th and 75th percentile of BMI, WC and BFM), overall overweight (50−75th percentiles of BMI), overall obesity (≥ 75th percentile of BMI, grade I with 75−90th percentile of BMI, grade II or severe with 90−97.5th percentile of BMI, and grade III or very severe with > 97.5th percentile of BMI), abdominal overweight (50−60th percentiles of WC), and abdominal obesity (≥ tertile II of WC, grade I with 60−75th percentiles of WC, grade II with 75−90th percentiles of WC, and grade III with ≥ 90th percentile of WC).

Clinical insulin resistance defined by WC ≥ 94 cm

The defined local levels of cardiometabolic risk (not precise: no risk, light, moderate, high, very high risk) according to the degree of nutritional status will be used in the future prediction of the components of sub-Saharan Africa-specific metabolic syndrome (diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) version 10.0 on Windows, Excel and R software.27 Analyses were stratified by gender, year of study,12 types of thresholds and degree of nutritional disorder. For the purpose of comparisons, the Chi-square test for percentages, Students t-test and one-way ANOVA test for means were used. The Scheffe post hoc test was used to determine significant differences. The simple correlation coefficient r was calculated between age and BMI. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

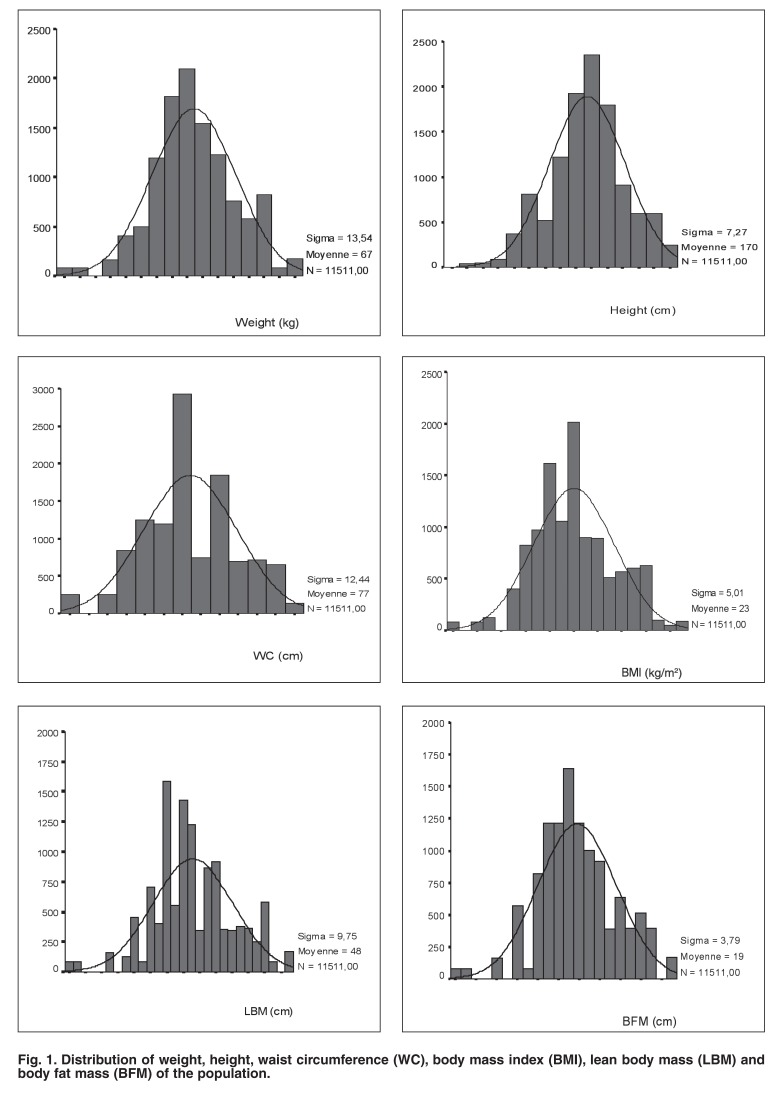

A total of 11 511 participants (response rate of 100%, 5 676 men, 5 835 women, mean age 37 ± 16 years) attended the morning mobile examination centre. The distribution of the nutritional status/body composition was Gaussian (Fig. 1). Table 1 presents the ranges, the normal values, means, percentiles, quartiles and reference limits of BMI, WC and BFM in the population.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of weight, height, waist circumference (WC), body mass index (BMI), lean body mass (LBM) and body fat mass (BFM) of the population.

Table 1. Local Characteristics Of The Study Population.

| Local values | BMI (kg/m2) | WC (cm) | BFM (kg) |

| Range | 9–37 | 46–104 | 46–104 |

| Quartile I | 9–20 | 46–68 | 7–16 |

| Quartile II | 20−23 | 68–76 | 16–18.5 |

| 50−60th percentiles | 20–23.9 | 76–79.9 | 18–18.9 |

| 60−70th percentiles | 24–24.9 | 80–83.9 | 19–19.9 |

| 70−80th percentiles | 25–27.9 | 84–86.9 | 20–21.9 |

| Quartile III or 75th percentile | 23–26 | 76–85 | 18.5–21 |

| 80−90th percentiles | 28–29.9 | 87–93.9 | 22–23.9 |

| ≥ 90th percentile | > 30 | > 94 | > 24 |

| Mean ± SD | 23 ± 5 | 77 ± 12 | 19 ± 4 |

| Normal values | 15–33 | 54–100 | 11–26 |

| References limits | 15−33 | 54−100 | 11–26 |

The WHO cut-off points overestimated the prevalence rates of general denutrition, but underestimated those of overall over weight and obesity (52%) in comparison with the respective rates calculated by the local thresholds (Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence Rates Of Nutritional Disorders Defined By The WHO And Local Cut-Off Points Of BMI.

| Nutritional disorders | WHO BMI cut-off points n (%) | Local BMI cut-off points n (%) |

| Denutrition | 1852 (16.1) | 288 (2.6) |

| Normal weight | 5867 (51) | 4967 (45.3) |

| Overall overweight | 2327 (20.2) | 3169 (28.9) |

| Overall obesity | 1465 (12.7) | 2547 (23.2) |

| Grade I | 1329 (11.5) | 738 (6.4) |

| Grade II | 136 (1.2) | 1231 (10.7) |

| Grade III | 0 (0) | 136 (1.2) |

WHO: World Health Organisation.

Despite the younger age of the female participants, mean values of the nutritional status/body composition data of the women were similar to those of the men (Table 3). The overall obesity rate defined by the WHO criteria (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) in men (12.2%, n = 691) was similar (p = 0.083) to that of women (13.3%, n = 774). However, the overall obesity rate estimated by the local threshold (BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2) was higher (p < 0.0001) in women (24.4%, n = 1 422) than in men (19.8%, n = 1 125).

Table 3. Comparison Of Characteristics Of Men With Those Of Women.

| Variables | Men | Women | p-value |

| Age (years) | 37 ± 16 | 36 ± 16 | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.4 ± 4.7 | 23.6 ± 5.3 | NS |

| WC (cm) | 77.4 ± 12.3 | 77 ± 12.6 | NS |

| Lean body mass (kg) | 48.5 ± 8.7 | 48.2 ± 10.7 | 0.143 |

| Body fat mass (kg) | 19 ± 4 | 19 ± 4 | 0.143 |

| Total body water (l) | 33 ± 3 | 33 ± 3 | 0.517 |

NS: p > 0.05

Table 4 presents the rates of abdominal obesity according to international and local thresholds. The rates of abdominal obesity estimated by the IDF criteria in men and women were similar (p > 0.05) to those defined by local criteria (without difference between men and women), respectively. However, the ATP III criteria underestimated the rates of abdominal obesity in men as well as in women.

Table 4. Prevalence Rates Of Abdominal Obesity Estimated By International And Local Cut-Off Points.

| Gender | ATP III cut-off points n (%) | IDF cut-off points n (%) | Local cut-off points n (%) |

| Men | 133 (2.3) by | 319 (5.6) by | 319 (5.6) by |

| WC ≥ 102 cm | WC ≥ 94 cm | WC ≥ 94 cm | |

| 2385 (40.9) by | |||

| WC ≥ 80 cm | |||

| Women | 954 (16.3) 2385 (40.9) | 2385 (40.9) by | 2385 (40.9) by |

| by WC ≥ 88 cm | WC ≥ 80 cm | WC ≥ 80 cm | |

| 319 (5.6) by | |||

| WC ≥ 94 cm |

WC: waist circumference.

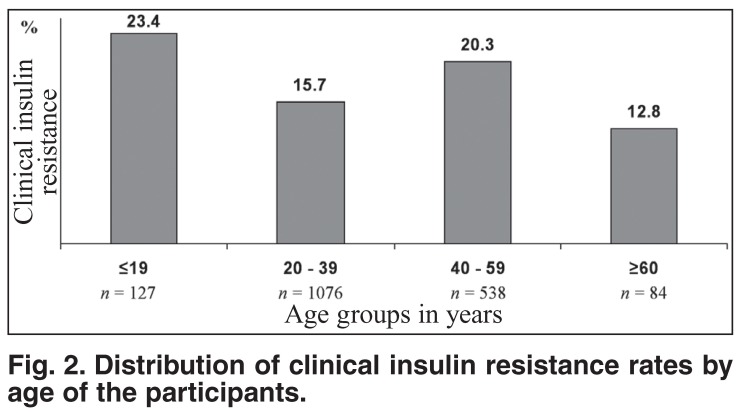

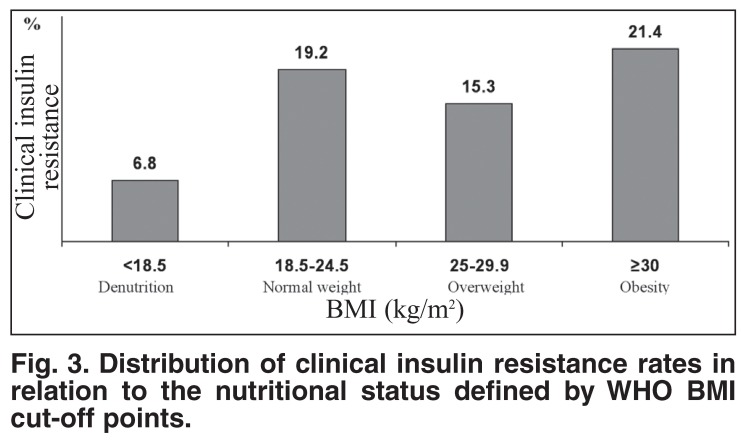

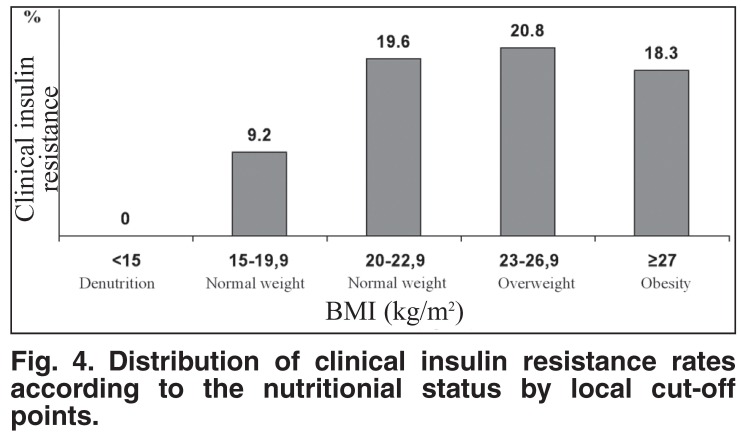

Despite the existing inverse relationship between clinical insulin resistance and age of participants, the highest rates of clinical insulin resistance were present among participants aged 19 years or younger and between 40 and 59 years (Fig. 2). The distribution of clinical insulin resistance rates by the degree of overall obesity defined by WHO criteria showed a paradoxical presence of clinical insulin resistance among participants with overall denutrition, and higher rates of clinical insulin resistance in participants with normal weight, in comparison with those who were overweight (Fig. 3). However, clinical insulin resistance was not present in denutrition and increased with the degree (positive relationship) of overall obesity defined by local BMI cut-off points (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Distribution of clinical insulin resistance rates by age of the participants.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of clinical insulin resistance rates in relation to the nutritional status defined by WHO BMI cut-off points.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of clinical insulin resistance rates according to the nutritionial status by local cut-off points.

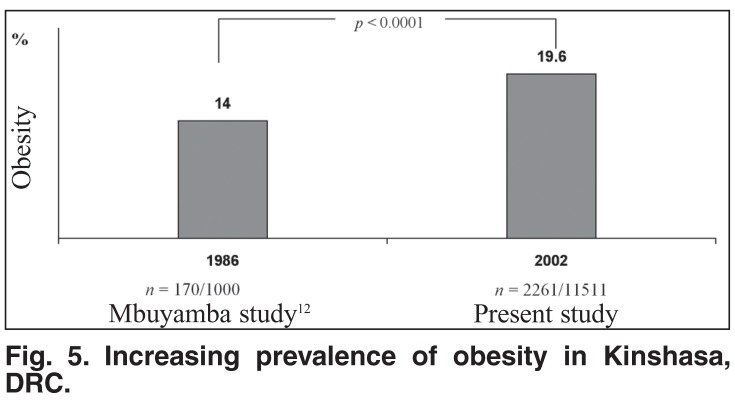

Using BMI ≥ 28 kg/m2 as the cut-off point, the present rate of obesity was higher (p < 0.0001) than that reported in 198612 and suggested an increasing trend of obesity (Fig. 5). Age was negatively correlated (r = 20.030; p < 0.0001) with BMI values.

Fig. 5.

Increasing prevalence of obesity in Kinshasa, DRC.

Finally, Table 5 provides a definition of the cardiometabolic risk according to sub-Saharan Africa-specific levels of nutritional disorders quantified by different levels of BMI, WC and BFM. This cardiometabolic risk profile will serve in future to identify individuals at higher risk for type 1 and 2 diabetes.

Table 5. Definition Of Levels Of Cardiometabolic Risk By Different Local Cut-Off Points Of BMI, WC And BFM.

| Nutritional status | Local cut-off points of BMI | Local cut-off points of WC | Local cut-off points of BFM | Cardiometabolic risk |

| Denutrition | < 15 | < 54 | < 11 | Undetermined |

| Normal weight | 15–22.9 | 54–75 | 11–18.9 | Reference |

| Overweight | 23–26.9 | 76–79 | 19–20.9 | Light |

| Obesity | ||||

| Grade I | 27–29.9 | 80–85 | 21–21.9 | Moderate |

| Grade II | 30–33.9 | 86 – 93 | 22–23.9 | High |

| Grade III | ≥ 34 | ≥ 94 | ≥ 24 | Very high |

BMI: body mass index, WC: waist circumference, BFM: body fat mass.

Discussion

This is the first study in Kinshasa to assess indices and disorders of nutrition. The present data on anthropometry and body composition in central Africans offer significant contributions, not only in providing an understanding of the index of health and well-being at both the individual and population levels, but also in terms of cardiometabolic risk.

Until now, African studies were limited to estimating the prevalence of overall overweight/obesity using different cutoff points of BMI.12,27 Concern for a new worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome3,4 has arisen from the lack of sub-Saharan Africa-specific cut-off points of waist circumference. Therefore, the need to identify the status of overall and abdominal overweight and obesity among African adults is important so that effective intervention programmes can be implemented at an early stage.

The first objective of this study was to establish local normal and reference values of body mass index, waist circumference and body fat mass at the population level. The normal values were roughly equivalent to the reference values of each nutritional parameter.

Using standardised methods, international thresholds,19-21 and local criteria (the cut-off points for overall overweight and overall obesity would have to be about 23−26.9 kg/m2, respectively; the cut-off points for abdominal obesity/clinical insulin resistance ≥ 80 cm, ≥ 90 cm and ≥ 94 cm; excess of body fat mass ≥ 21 kg), the present study reports higher rates of overweight/obesity in comparison with previous data from the same background.12,29 The lifestyle changes related to urban migration, industrialisation, westernisation,13 epidemiological and nutrition transitions16,17 may explain the difference between developing countries and developed nations.8-10

As reported for industrialised countries,2-6,28 the present high rates of overall and abdominal obesities might also explain the emergence of non-communicable diseases (arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, cancers and cardiovascular diseases) in sub-Saharan Africa.30-33 However, the WHO criteria23,24 tended to underestimate the prevalence of overall overweight and overall obesity, and to overestimate the prevalence of denutrition in comparison with local criteria. The prevalence of abdominal obesity in men and women, respectively, was underestimated by the ATP III cut-off points.21,22 The underestimation of overall and abdominal obesities in central Africans was also reported in Cameroon.29 Curiously, the IDF thresholds to define abdominal obesity (central adiposity) rates for Europid, sub-Saharan African, Eastern and Middle-Eastern populations (WC ≥ 94 cm for men and ≥ 80 cm for women) underestimated rates of abdominal obesity in comparison with local cut-off points for WC.

In considering only waist circumference ≥ 94 cm to define clinical insulin resistance, the WC ≥ 94-cm cut-off point (≥ 90th percentile of WC) corresponded to body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2 (≥ 90th percentile of BMI) and body fat mass ≥ 24 kg (90th percentile of BFM). Therefore, WC ≥ 94 cm defined individuals with a very high cardiometabolic risk in this African population. WC ≥ 94 cm and ≥ 80 cm for men and women, respectively provided the same rates of abdominal fat as reported in Cameroon for WC ≥ 94 cm.29

The present study shows that clinical insulin resistance (WC ≥ 90 cm including grades II and III of abdominal obesity) was present in each category of nutritional disorder defined by WHO BMI criteria,23,24 including denutrition. The merit of the local BMI criteria to define nutritional disorders was the absence of clinical insulin resistance within the denutrition category. These results suggest that BMI cut-off points (mostly BMI < 30 kg/m2) do not evaluate the same excess of fat mass29,35 and the fat-related cardiometabolic risk in comparison with WC cut-off points. Indeed, WC ≥ 94 cm compared with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 was the better predictor of arterial hypertension in a working population of Africans in Kinshasa.36 This is because the visceral fat distribution (abdominal obesity) is metabolically more active than the subcutaneous fat, and therefore more harmful for health in general,37 and risk of atherosclerotic diseases in particular.38,39

Therefore, waist circumference is the best simple anthropometric index of abdominal and visceral adipose tissue accumulation and is proposed as a surrogate of insulin resistance/hyperinsulinaemia in sub-Saharan Africa with low resources and low values of serum total cholesterol and triglycerides, but high levels of HDL cholesterol.31-33 As the measurement of waist circumference is recommended to identify individuals requiring intervention to reduce cardiometabolic risk,40 the present study proposes the use of the following categories to indicate in combined male and female Africans: low cardiometabolic risk, < 80 cm; increased risk, 80−93 cm; and substantially increased risk, ≥ 94 cm. These cut-offs correspond to BMI of < 27 kg/m2, 27−30 kg/m2, and ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively.

The concomitant presence of denutrition and obesity means that these young adults (37 ± 16 years) are facing epidemiological, demographic and nutrition transitions.8,14-16 Furthermore, the economy of DRC has been in recession with predictably deleterious effects on these participants with denutrition: a decrease in body weight and body fat associated with inadequate food and energy supplies. However, some Africans with denutrition and higher levels of WC will have a higher risk of arterial hypertension, as demonstrated among African children from Kinshasa with higher blood pressure and heart rate in comparison with their normal-weighted counterparts.41

The progression to the metabolic syndrome and atherosclerotic diseases for Africans with denutrition and normal weight may be explained by the positive relationship between Helicobacter pylori and higher waist circumference and blood pressure, higher levels of total cholesterol and fibrinogen, but lower HDL cholesterol levels than shown in lean adult Africans.42

Contrary to Africans from Cameroon with a positive relationship between age and BMI levels,29,43 the Africans in this study from Kinshasa showed a negative correlation between age and BMI levels. Furthermore, despite the highest rates of clinical insulin resistance (WC ≥ 90 cm) observed for ages 19 years and younger and between 40 and 59 years, globally there was a negative correlation between clinical insulin resistance and age of participants.

We understand now why the age of 60 years or older is one of the risk factors of the epidemic of ischaemic stroke among Congoleses patients,32,33 as individuals from 40 to 59 years have a higher cardiometabolic risk. The present findings also suggest that the risk of the metabolic syndrome (type 2 diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension) would appear before the age of 20 years and after the age of 40 years. This observation explains the difficulty we are facing to classify diabetes mellitus and to define type 2 diabetes in Kinshasa.

Conclusion

There were differences in defining prevalences of overall and abdominal obesities when WHO criteria, ATP III and local Africa-specific cut-off points of BMI and WC were used; transient IDF thresholds for sub-Saharan Africa were equivalent to local Africa-specific cut-off points of WC. As WHO criteria and ATP III cut-off points underestimated the prevalence of overall overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity, it was necessary to take into account age, body shape, nutrition transition, economic recession and ethnicity before interpreting BMI and WC in terms of cardiometabolic risk.

Not taking into account gender for sub-Saharan Africa, the following cut-offs are recommended to identify individuals at higher cardiometabolic risk: low risk (BMI < 27 kg/m2 and WC < 80 cm), increased risk (BMI 27−30 kg/m2 and WC 80−93 cm), and substantially increased risk (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2 and WC ≥ 94 cm).

Increasing and epidemic levels of overall overweight/obesity and abdominal obesity (52%) has caused the need for further serial urban and rural studies to monitor trends and validate optimal thresholds to establish a new worldwide definition of the metabolic syndrome.

Contributor Information

JB Kasiam Lasi On’kin, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo.

B Longo-Mbenza, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo.

A Nge Okwe, Biostatistics Unit, Lomo Medical Centre and Heart of Africa Centre of Cardiology, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo.

N Kangola Kabangu, Biostatistics Unit, Lomo Medical Centre and Heart of Africa Centre of Cardiology, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo.

References

- 1.Bray GA. Overweight is risking fate. Définition, classification, prevalence, and risks. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;499:14–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb36194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaufman F. Diabesity: The Obesity−Diabetes Epidemic That Threatens America, and What We Must Do to Stop it. New York: Bantam; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberti KGMM, Zimmet P. The metabolic syndrome − a new worldwide definition. Lancet. 2005;366:1059–1060. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67402-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reaven GM. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haffner S, Taegtmeyer H. Epidemic obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Circulation. 2003;108:1541–1545. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000088845.17586.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hennekens CH. Increasing burden of cardiovascular disease: current knowledge and future direction for research and risk factors. Circulation. 1998;97:1095–1102. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.11.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray CJ. Geneva: WHO; 1996. Global Burden of Disease and Injuries Series. Vol 1: The global burden of disease. A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Vander Hoorn S, Murray CJL. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet. 2002;360(9343):1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King H, Aubert RE, Herman WH. Global burden of diabetes, 1995−2025: prevalence, numerical estimates, and projections. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1414–1431. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.9.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Obesity. Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Geneva: WHO; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.et al. Etat des lieux du Secteur de la santé: enquêtes auprès des ménages et profils sanitaires des provinces et zones de santé. Kinshasa: Ministère de la santé publique, Rapport provisoire, Mars. 1999

- 12.M’buyamba-kabangu JR, Fagard R, Lijnen P. et al. Epidemiological study of blood pressure and hypertension in a sample of urban Bantu of Zaire. J Hypertens. 1986;4:485–491. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198608000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu Z, Nissinen A, Vartiainen E, Song G, Guo Z, Tian H. Changes in cardiovascular risk factors in different socioeconomic groups: seven year trends in a Chinese urban population. J Epidemiol Comm Hlth. 2000;54:692–696. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.9.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngondo A, Pitshandenge S. Kinshasa; CEDAS: Perspectives démographiques du Zaïre 1984−1999. pp. 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.et al. Un aperçu Démographique, Kinshasa. 2001

- 16.Caselli G, Meslé F, Vallin J. Epidemiologic transition theory exceptions. Genus. 2002;58(1):9–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meslé F, Vallin J. Transition sanitaire: tendances et perspectives. Méd Sci. 2000;16:1161–1171. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts L. International Rescue Committee. Bukavu DRC: May, 2000. Mortality in Eastern DRC: Results from five mortality surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 191.Misra A, Wasir JS, Vikram NK. Waist circumference criteria for the diagnosis of abdominal obesity are not applicable uniformly to all populations and ethnic groups. Nutrition. 2005;21:969–967. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford ES. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome defined by the International Diabetes Federation among adults in the US. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(11):2745–2749. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.11.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.et al. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3160–3167. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.et al. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bray GA, Bouchard C. Handbook of Obesity. Etiology and Pathophysiology. 2nd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Croft JB, Keenan NL, Sheridan DP, Wheeler FC, Speers MA. Waist-to-hip ratio in a biracial population: measurement, implications, and cautions for using guidelines to define high risk for cardiovascular disease. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:60–64. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mellits ED, Cheek DB. The assessment of body water and fatness from infancy to adulthood. Brozek J, editor. Physical Growth and Body Composition. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1970;35(7):12–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pace N, Rathbun EW. Studies on body composition III. The body water and chemically combined nitrogen content in relation to fat content. J Biol Chem. 1945;158:685–691. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Amoah AG. Obesity in adult residents of Accra, Ghana. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:S97–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han TS, Williams K, Sattar N, Hunt KJ, Lean ME, Haffner SM. Analysis of obesity and hyperinsulinemia in the development of metabolic syndrome: San Antonia Heart Study. Obes Res. 2002;10:923–931. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’ Kamadjeu RM, Edwards R, Atanga JS, Kiawi EW, Unwin N, Mbanya JC. Anthropometry measures and prevalence of obesity in the urban adult population of Cameroon: an update from the Cameroon burden of Diabetes Baseline Survey: Br Med C Publ Hlth. 2006;6:22–28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO Regional Office for Africa; Harare: 2000. Non-communicable diseases: A strategy for the African region. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Longo-Mbenza B, Lukoki-Luila E, Phanzu Mbete LB, Kintoki Vita E. Is hyperuricemia a risk factor of stroke and coronary heart disease among Africans? In J Cardiol. 1999;17:17–22. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(99)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Longo-Mbenza B, Phanzu-Mbete LB, M’buyamba-Kabangu JR, Tonduangu K, Mvunzu M, Muvova D, Lukoki-Luila E. et al. Hematocrit and stroke in black Africans under tropical climate and meteorological influence. Ann Med Interne. 1999;150(3):171–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longo-Mbenza B, Tonduangu K, Muyeno K, Phanzu-Mbete LB, Kebolo Baku A, Muvova D, Lelo T. et al. Predictors of stroke-associated mortality in Africans. Rev Epidém et Santé Publ. 2000;48:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper RS, Amoah AG, Mensah GA. High blood pressure: the foundation for epidemic cardiovascular disease in African populations. Eth Dis. 2003;13(2 Suppl 2):S49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belahsen R, Mziwira M, Fertat F. Anthropometry of women of childbearing age in Morocco: body composition and prevalence of overweight and obesity. Pub Hlth Nutr. 2004:523–530. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Longo-Mbenza B, Nkoy Belila J, Vangu Ngoma D, Mbungu S. Prevalence and risk factors of arterial hypertension among urban Africans in workplace: the obsolete role of body mass index. Niger J Med (in press) doi: 10.4314/njm.v16i1.37280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montague CT, O’Rahilly S. The perils of portliness: causes and consequences of visceral adiposity. Diabetes. 2000;49:883–888. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.6.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pouliot MC, Despres JP, Lemieux S. et al. Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:460–468. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seidell JC, Bouchard C. Abdominal adiposity and risk of heart disease. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;281:2284–2285. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.24.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han TS, Van Leer EM, Seidell JC, Lean ME. Waist circumference action levels in the identification of cardiovascular risk factors: prevalence study in a random sample. Br Med J. 1995;311:1401–1405. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7017.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longo-Mbenza B, Lukoki Luila E, M'buyamba-Kabangu JR. Nutritional status, socio-economic status, heart rate, and blood pressure in African school children and adolescents. Int J Cardiol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.11.004. (e-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Long-Mbenza B, Nkondi Nsenga J, Vangu Ngoma D. Prevention of the metabolic syndrome insulin resistance and the atherosclerotic diseases in Africans infected by Helicobacter pylori infection and treated by antibiotics. Int J Cardiol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.12.003. (e-pub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pasquet P, Temgoua LS, Melaman-Sego F, Froment A, Rikong-Adie H. Prevalence of overweight and obesity for urban adults in Cameroon. Ann Hum Biol. 2003;30(5):551–562. doi: 10.1080/0301446032000112652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]