Abstract

In contrast to the large literature on patients’ coping with an initial diagnosis of cancer, there have been few quantitative or qualitative studies of patients coping with recurrence. A qualitative study was undertaken to aide in the development of a tailored intervention for these patients. Individuals (N=35) receiving follow-up care for recurrent breast or gynecologic cancer at a university-affiliated cancer center participated in an individual or a group interview. Transcripts of interviews were analyzed using a coding format with two areas of emphasis. First, we focused on patients’ emotions, as there is specificity between emotions and the corresponding ways in which individuals choose to manage them. Secondly, we considered the patients’ social environments and relationships, as they too appear key in the adjustment to, and survival from, cancer. Patients identified notable differences in their responses to an initial diagnosis of cancer and their current ones to recurrence, including the following: 1) depressive symptoms being problematic; 2) with the passing years and the women’s own aging, there is shrinkage in the size of social networks; and, 3) additional losses come from social support erosion, arising from a) an intentional distancing by social contacts; b) friends and family not understanding that cancer recurrence is a chronic illness, and/or c) patients’ stemming their support requests across time. The contribution of these findings to the selection of intervention strategies is discussed.

Keywords: Cancer, oncology, emotions, social support, recurrence

Introduction

The absolute numbers of recurrence diagnoses per year is staggering, over 1.2 million expected in 2013, with over a half million individuals succumbing quickly to their disease [1]. Approximately, 20% of women with breast cancer and 40% with gynecologic cancer will recur within 10 years of diagnosis [2]. Prognosis following recurrence is generally poor, and for many there is a high symptom burden [3–6]. Biobehavioral research on recurrence remains at an early stage with the majority of the studies being descriptive or cross-sectional. Psychological and behavioral interventions have been developed to help patients cope at the time of initial diagnosis, but further information is needed to understand recurrent patients’ emotional responses and their social environment.

To this end, qualitative information was collected to better understand the emotional responses and needs of recurrence patients so that intervention strategies could be identified and adapted to this unique population. Studies have focused on negative emotions at recurrence. For example, depressive symptoms, including sadness and hopelessness [7–8], can occur along with other problems such as appetitive difficulties [9] or poor body image [10]. Studies of anxiety-related responses have documented fears of death, disability [6, 11–12], and loss of social relationships and support [12–14]. From this, therapies have been suggested or used for the management of negative emotions and behaviors [15], solving problems such as those posed by difficult physical symptoms [16–17], or existential concerns [18]; there are fewer directions for enhancing positive emotions [19].

This study examines emotional experiences—positive and negative—recognizing that an intervention for this population must capitalize upon and bolster existing areas of emotional strength, as well as foster new skills for dealing with difficult emotions that arise with recurrence. In addition, social aspects of the recurrence stressor were examined. The numbers, availability, and support of close others are associated with improved health outcomes for all individuals [20], including cancer patients [21–23]. Without intervention, however, the presence of a significant stressor like the diagnosis of cancer recurrence may strain the patients’ support network in unique ways. We were uncertain if social support would continue as it was established at the time of the initial diagnosis or if there would be a substantive change in the availability of support for some women.

Method

Participants

Thirty-five individuals participated. On average, women were 61-years-old (range 42–76; SD=9.4), Caucasian (86%), and married (66%); 40% were employed full- or part-time, 31% were retired, and 29% were unemployed (which included 17% with disability). The median family income was $57,500. Cancer diagnoses were as follows: breast (n=16) and gynecologic (n=19). When diagnosed initially, the majority received at least two treatment modalities: surgery (89%), chemotherapy (77%), and/or radiotherapy (49%). The median disease-free interval was 2.8 years (mean=4.9, range=0.20–38.4, SD=7.1). For recurrence, current treatments included the following: chemotherapy (89%), recent surgery (49%) and/or radiotherapy (14%). The median time since recurrence was 2.8 years (mean=3.0, range=0.22–16.3, SD=3.1).

Procedures

Patients diagnosed with recurrent breast or gynecologic cancers receiving follow-up care at a university-affiliated, National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center oncology clinics were sought. Exclusion criteria were as follows: age < 20 or > 85 years, other cancer diagnoses, residence > 60 miles from the center, and inability to provide informed consent. Potentially eligible patients were approached in the clinic prior to an appointment. All were provided with oral and written informed consent, indicating their awareness of the investigational nature of the study, in keeping with the institutional guidelines, and in accordance with an assurance approved by and filed with the US Department of Health and Human Services. Regarding accrual, 52 eligible patients were identified, 50 were approached, 41 completed informed consent, and 35 completed interviews, with the remaining 6 being too ill or having scheduling difficulties.

Elements guiding initial intervention conceptualization were the Biobehavioral Model of Cancer Stress and Disease Course on which our prior interventions were based [24–25], as well as approaches used in the limited past psychological intervention research patients with recurrence or advanced cancer. The qualitative aim was to ensure that our conceptual framework adequately aligned with women’s experiences and addressed their needs so that intervention strategies could be added or adjusted as needed. The interview guide (designed by senior team: L.M.T, A.O.L., and B.L.A.) included open-ended questions about women’s experience (e.g. “Could you tell me a little about your experiences since you learned of your recurrence diagnosis?”) and their coping strategies, specific problem/challenge areas, and areas in which more assistance was needed. It also included probes to obtain information about the acceptability of intervention strategies (e.g., relaxation, social support) used [24].

Interviews were conducted by senior, female, Ph.D. level clinical psychology researchers with both clinical and research experience with cancer patients. Individual (n=27) or group (n=9) audio recorded interviews, lasting 45 min. each, were conducted, with the interviewer making field notes after each interview and suggesting revisions to the interview guide as needed to ensure that emergent themes were added. Patients received $50 for their time and did not participate further.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed with the assistance of Altas.ti software [26]. An initial coding scheme was crafted based on the prior goals, theoretical model, etc., but new themes emerging during the interviews (revealed in field memos and in discussions with interviewers) were also included. Codes were applied to the data by trained Ph.D. level research assistants (n=4) in the Atlas.ti program. Each transcript was coded by two independent coders and were regularly reviewed by the senior team to ensured similar understanding of the codes and consistency of judgment [27]. No thematic differences were noted between the group and individual interviews. Using Altas.ti, the final code scheme had seven domains: (1) emotions, (2) interpersonal relationships, (3) sexuality, (4) medical system and communication with providers, (5) physical, (6) financial/legal, and (7) spirituality or meaning in life.

The senior team then reviewed all the data relevant to each code and wrote analytic memos, one for each of the seven codes. Using Atlas.ti, data were retrieved and two person pairs of coders (n=4) were assigned to a code, with each person drafting an analytic memo for the code. The later memos were then discussed and a final memo for a code was crafted, each with the following sections: a) problem areas, b) change from initial to recurrence, c) coping resources, and, d) intervention strategies. Here we present a subset of the findings from analytic memos, highlighting the three areas: 1) negative and positive emotional experiences; 2) interpersonal aspects; and, 3) emotional or interpersonal differences between the initial and recurrence diagnosis, if any.

Results

Emotions

Depression

Emotions included sadness, negative feelings about the self, indecision, lack of motivation, and hopelessness, with accompanying vegetative symptoms. When compared to the initial diagnosis, some women expressed greater depressive symptoms. For some, the sadness was overwhelming with the return of a disease that was now incurable.

“So I was depressed. I went into a deep depression…this time people tell me, ‘Well, you know you’ve survived it before.’ And I feel like even if I survive it now, for how long will it be?”

“…Emotionally for me I was really—I think I was probably devastated to find out not that I had a recurrence, but that it metastasized and I didn’t even know what it meant….I was like, ‘Holy crap I’m in trouble…’ I immediately thought, ‘Am I gonna die like right now?’ It was really hard.”

Anxiety

Women described emotions of nervousness, fear, worry, and for some, a sense of foreboding. This included awareness that one’s prognosis was worsened and the possibility that longer or more difficult treatments would follow. All noted being anxious at the initial diagnosis, but the diagnosis of recurrence was associated with heightened levels of fear for some.

“I know the first time around I was very upset…. But I wasn’t quite as shocked because I know that 1 out of 9 women get cancer…. But the second time around, I wasn’t expecting it at all. It just seemed different, and it was just a lot scarier.”

“Because as I said the first time you’re gonna be fine, everything’s ok. The second time around was like, ‘Oh no this is bad, it‘s back.’ It was a lot scarier, and I’m still scared.”

However, prior experience with cancer armed women with information, familiarity with the oncology staff, logistics of treatment, etc., which countered anxiety and provided a sense of control.

“It’s the initial part that’s the scary part. Once you’ve had a treatment and it wasn’t all that bad and you managed to get through it, then the second time around isn’t so bad.”

“Well I wasn’t shocked, I wasn’t horrified by it like the first time you hear you have cancer. It’s like, ‘Oh it’s back, and okay we’ll deal with it.’ That’s how much I had learned about cancer. That if it would come back, there are options.”

Anger

In its mildest form, anger includes feelings of irritation, frustration, or envy, but can extend to rage or aggression. Many reported following physicians’ recommendations or adopting a healthier lifestyle after the initial diagnosis, but “doing everything right” did not matter, leading to anger.

“I asked the doctors, ‘What am I doing wrong?’ Am I eating right? I try to eat my vegetables. I never smoke. I don’t drink. I’ve never been overweight in my life.”

“I just get frustrated because I was very proactive with my health. I was under a doctor’s care and he still missed it… And now I have a recurrence, it pisses me off because I did everything I’m supposed to do…”

Happiness

While there was much negativity noted, women spontaneously described feelings of acceptance, positive emotions, or engaging in behaviors that made them feel happy. Some described active attempts to shift their emotions or mindfully accepting difficult circumstances and living in the present.

“At this point I’m just positive as I can be… and happy. And this isn’t always a happy situation I realize.”

“[My husband] would usually take me [to radiation treatment] maybe once or twice a week…. It’s not that I couldn’t have gone by myself, but…we just made an outing of it and made it fun.”

“We all should live each day to the fullest and we’ve been reminded of that, so that’s what we’re doing.”

“You just got to accept you have cancer just like somebody with diabetes or a heart problem. You got it. And I had to accept I have it and there’s no cure.”

Love

Women’s positive responses also included feelings of self-love, kindness, affection, and wanting to help others.

“And the first person you have to forgive—for anything—is yourself. If you can forgive yourself, you can forgive other people. It makes life better.”

Hope

Hope can be experienced as a sense of optimism, belief in one’s ability to generate ways to reach important goals, and the requisite motivation to initiate and sustain movement toward goals [28–29]. Many conveyed not wanting to give up or lose hope; they still had a life to live and goals to complete. At times, the help of others, especially other cancer survivors, prompted hope.

“I figure I can take anything now, because this is pretty darn traumatic. I feel confident that I can handle this, I can handle anything, whereas I didn’t feel that way before.”

“I met one lady [and…when] I met her, I said, ‘Are you sure you have had breast cancer and ovarian and you’re doing okay?’ And she says, ‘Oh yeah, I’m working and all that and life goes on.” It really helps a lot seeing someone else who is going through what you’re going through now, and they’re doing fine and you feel, ‘I can beat this’.”

Responses to and from the social environment

Social network shrinkage and erosion

Changes in one’s social network occurs across the life span [30]. For this age group, normative life events that decrease one’s social network may include retirement, death of a parent, or loss of a spouse. With the passing of years since the initial diagnosis and the patients’ own aging, shrinkage in the social network occurred, making coping more difficult.

“I think the hardest thing for me personally was not having my husband. I wondered why my husband was taken because I sure could’ve used him in these last 11 years because he would’ve been so wonderful.”

“…When I had my first one I was employed, and I had a good network of friends that I was pretty close to. …The second time, I was retired, and your circle of friends…you don’t have the same frequency of contact.”

Another source of social change was support erosion—a change from initial to recurrence in support received for the diagnoses. One source seemed to be intentional distancing by friends or acquaintances. Another source occurred when friends and family did not understand the nature of cancer recurrence—its continuing stress, physical debilitation, and fatigue. Lacking this understanding, friends or family might not provide support or provide support that did not match the patient’s needs.

“Before there was like a whole group of people…they would send me a card…or they would call and say ‘Hey, how are you doing?’…And now you know they went on with their lives…So I’m alone more…”

“When I first had the surgery, we had offers for help. You know things like that. Now my house is not really very clean…People don’t—they just ignore the situation.”

“I’m doing it on my own. And they’re doing the best they can, my particular family… but when it comes to Stage IV cancer, they have no knowledge how to talk to somebody or anything. So, that’s the big difference.”

With the decrease in size or frequency of contact with those in their support network, some women relied on a smaller number of supportive others. Many felt guilty about asking for help, prompting some to not ask or talk about their experiences or feelings. Worry about burdening their family now or worry of future burdens upon their passing contributed to such feelings.

“I didn’t even tell my family that I was going through it the second time…. I told them afterwards. And my mother said, ‘You should have told me.’ I think I might have told one sister, but not the rest of the family. My dad was still having problems so I didn’t want him to worry.”

“Well, I was diagnosed again in April, and that was my one big thought: ‘I got to get this house sold. I got to get this all figured out so my daughters don’t have to take care of it.’”

Lastly, the women themselves reported narrowing their social networks intentionally. This self-imposed social change was viewed positively.

“There were people in my life with a lot of drama, and I was the go-to person… I would help you, but I can’t do that anymore. And so, those people I’ve slowly let drift out of my life. If you’ve got a lot of drama…I’m not your person anymore.”

“And it just came to me that I can’t do everything I used to do, housework-wise or handling other people’s problems. I gotta concentrate now on me…Cancer has kind of taught you that.”

Positive support

Despite possible reductions in the numbers of persons available, the majority of individuals gave examples of receiving emotional support from friends, relatives, or other cancer survivors and of receiving help with chores of home life or the “tasks” of going to treatment.

“Just like my son that lives at home now, he takes care of all the outside grass-cutting and all that sort of stuff, so I don’t have that to worry about. And, the girls come in and they wash up my dishes whenever they’re sitting there, when I’m not feeling too good.”

Support failures and mismatches

Of course, not all of the support that was offered was felt positively. There were examples of negative, ill-timed, or thoughtless remarks. More common, however, was a poor matching of support offered with what the patient wanted or needed.

“I have a sister that I cannot talk to her all the time because every time I talk to her she says, ‘How you feeling?’ I say, ‘Oh, I’m feeling okay today.’ And she says, [(dramatically]) ‘Oh, You know you’re going to be fine!’ And then I asked her, ‘How you know?’ And she said, ‘Because you know if the Lord wanted you to die, you would be gone by now.’ And I go, ‘You don’t know that,’ and we can argue like that.”

“…we have to find ways to say, ‘I am still me. I’m still me and the boundaries that we had before are still there.’ You know, ‘because I have breast cancer doesn’t mean that you can call me 17 times a day and come to my house every time you feel like it because you’re worried that I’m going somewhere.’ … just letting people know that I’m still the same.”

Emotional support from a significant other and intimacy

A spouse or partner can provide emotional support, get information, or simply manage tasks. However, some women worried about their partner’s emotional struggles with their cancer. In addition, several mentioned the importance of physical intimacy and the need to feel their partner’s love and affection even though their own sexual desire was low.

“My husband is supportive in his own fashion, but you can’t expect to get everything you need from most husbands… Yeah, it drags ’em down… he has his own fears of death and dying that I don’t have.”

“I didn’t want that detachment. I wanted that relationship closeness, the sensual side of things… I didn’t want any of our marriage to crumble, any aspect of it, and I never wanted my husband to come home and see me laying on the couch or laying in the bed because I was sick.”

Discussion

Qualitative interviews were an early step to develop a tailored psychological intervention for those coping with recurrence. We focused on patients’ emotions, as intervention targets would include changing negative emotions and enhancing positive emotions. We also focused on the patients’ social environment and relationships. While therapists provide important support, patients’ friends and family are the primary sources of sustained contact and connection. Two areas—emotion regulation and social ties—are key to adjustment to and survival from cancer [21, 31].

Meta-analyses consistently show larger intervention effect sizes for treating anxiety symptoms rather than depressive ones [32–33]. However, the qualitative data here suggest that depressive symptoms may be more problematic for those with recurrence. This is consistent with estimates for the frequency of major depressive disorder, 8 to 40% for patients with advanced disease [34] and higher estimates for those with recurrence [35]. Most salient were symptoms of sadness, pessimism, loss of hope, and for some, feeling both sad and alone. Interestingly, in accordance with previous studies, women made no mention of negative feelings about the self (worthlessness, self-dislike, punishment) commonly seen in depressed psychiatric patients [36]. The importance of depression in premature mortality in healthy adults [37] as well as those with cancer is well documented [38].

Considering anxiety, it is not the case that it is not problematic, it is. Unlike the newly diagnosed, recurrence patients have learned to navigate the medical system, have experience with cancer treatments, and are familiar with oncology professionals [5]. Thus, anxiety at recurrence manifests as less physiological (e.g., feelings of tension, anxiety) and more cognitive (e.g., worry, rumination, and intrusive thoughts). Foci include worry of physical symptoms, cancer progression, cancer death, and the needs of their family. Lastly, anger was voiced by some, including the frustration that their own efforts and cancer treatments had not kept the disease at bay and annoyance at facing additional rounds of therapy.

In contrast, patients’ expressions of positive emotions provide information on their own coping strategies. Happiness could be achieved by choosing circumstances that left patients feeling good, actively changing unavoidable situations (such as going to treatment) by linking them to positive occasions (like going on outings afterwards), and accepting that theirs was a chronic, untreatable illness. Women also provided comments of self-forgiveness for past events or examples of self-care when eliminating stressors or ending unsatisfying relationships.

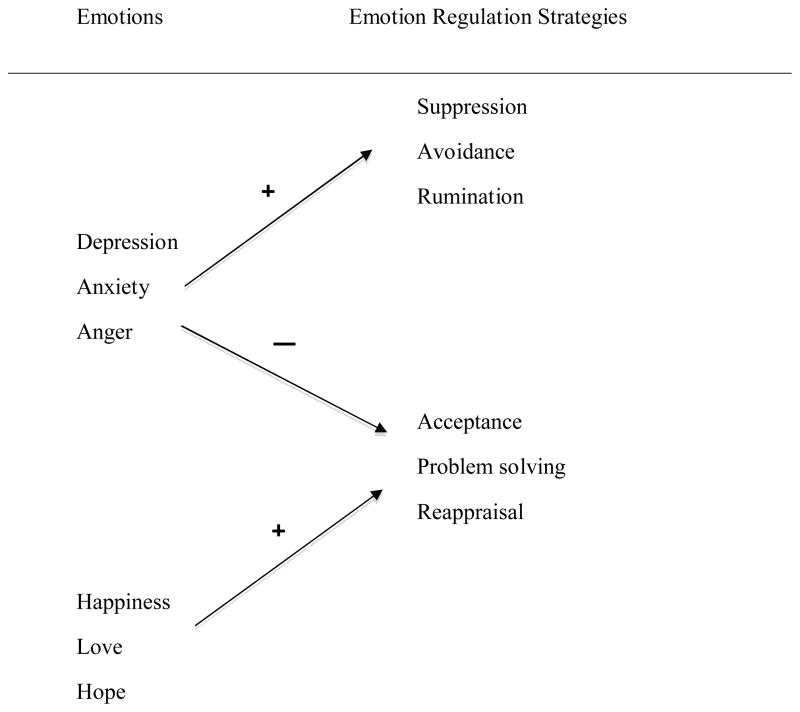

We viewed emotions as drivers of patients’ own emotional-regulation strategies, be they adaptive or maladaptive. Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, and Schweizer [39] discuss three maladaptive strategies that put individuals at further risk for heightened negative emotions if not psychopathology. One is suppression of emotional expression or unwanted thoughts [40], which increases the likelihood of negative affect and negative thoughts. A second is experiential avoidance [41], or avoiding thoughts, emotions, or memories related to an unpleasant experience. Lastly, instead of avoiding or suppressing negative thoughts and moods, some individuals focus on their emotions, particularly their anxiety, and worry and ruminate about the cause, consequences, timeline for its worsening, etc.

In contrast, three strategies are widely regarded as protective [39]. Reappraisal—generating benign or positive interpretations of difficult situations is beneficial for positive emotions [42]. Problem solving involves active attempts to change a stressful situation, change one’s response to it, and plan for a new course of action. Proposed years ago [43], problem solving continues as a mainstay in the treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders, including those of cancer patients [17, 44]. Lastly, non-judgmental acceptance of difficult emotions, feelings, or sensations is another strategy for adaptive emotion regulation.

Figure 1 displays the linkage between emotions and the regulation strategies they may evoke. The arrows indicate the two-pronged powerful effect of depression, anxiety, and anger: they increase the likelihood that an individual will use maladaptive strategies and decrease the likelihood of using adaptive strategies. The emotions of happiness, love, and hope, in contrast, increase an individual’s use of adaptive strategies. It is not clear, however, that positive emotions exert any effect—direct or indirect—on reducing negative emotions or decreasing maladaptive choices. Empirical support for this conceptualization comes from two studies with patients with recurrence. Yang [45] found that traumatic stress regarding the diagnosis of recurrence exerted a powerful, negative effect on quality of life months later; however, this effect was mediated by patients being more likely to use maladaptive strategies—denial, avoidance, and alcohol use—to cope. Giese-Davis and colleagues [46] reported that, unfortunately, even when psychological treatment reduces negative emotions, adaptive coping does not necessarily improve. This conceptualization suggests that for interventions, adaptive coping needs to be addressed systematically by teaching, prompting, and helping patients maintain adaptive strategies.

Figure 1.

Negative and positive emotions and the corresponding strategies used for emotion regulation.

Considering the social domain, cancer can be isolating, with the challenge being to mobilize oneself and one’s environment to make it less so. Research is clear: network numbers matter [20, 47]. A notable impression from these interviews was the shrinkage in the network size from the initial to recurrence diagnosis. The reduction was oftentimes “natural” [7], as with retirement, but the losses are life changing nevertheless. Confronting recurrence is worsened when one is alone [7] and overall, unmarried cancer patients are at greater risk for depressed mood when compared to married patients [48].

In addition to fewer contacts, the interviews suggested a reduction in the frequency of contact with the remaining supportive others. We can only hypothesize why this may occur, but research suggests that the level of patient’s distress may contribute [49–51]. When patients’ distress is prolonged, close others may eventually find it overwhelming, leading to burnout for supporters and/or patients feeling guilty for needing support. Lastly, many felt friends or family simply did not appreciate the qualitative differences of recurrent disease or treatments (e.g., chronic fatigue, longer recoveries following chemotherapy, etc).

Directions for treatment tailoring are suggested by these data. We do not know, however, how generalizable our summaries of the comments would be to others with different characteristics (e.g., gender, ethnicity, site of disease) than these patients. The treatment components discussed below are ones common to the intervention literatures, but we know little of whether or not treatment “matching” is important when treating cancer patients, with or without recurrence.

Components relevant to emotion regulation and social aspects of recurrence are considered. Interventions for anxiety and depressive disorders, as well as interventions for cancer patients, focus on reducing negative emotions directly via emotional, cognitive or behavioral change. Progressive muscle relaxation, problem solving, or assertive communication, for example, has been used successfully for reducing negative mood and stress [32–33]. There are fewer therapies for increasing adaptive emotional regulation, per se, but mindfulness is receiving attention. While the elements of mindfulness are a point of debate amongst researchers and clinicians, non-judgmental acceptance of emotions is seen as key. To the degree that depressive and anxiety symptoms are associated with thoughts, feelings, or worries tied to negative past experiences or the anticipation of future challenges, mindfulness skills might be useful. Treatment strategies employing mindfulness have been used to reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety in a variety of clinical samples [52], including cancer patients [53].

A second treatment element is to increase the likelihood of positive emotions and pursuits, as suggested above. As observed here and found empirically, cancer patients report fewer achievement and leisure goals [54–55] compared to healthy controls. Moreover, cancer recurrence can change the likelihood or salience of some goals and decrease hopeful thoughts about others. Snyder and colleagues [56] conceptualized hope as beliefs related to one’s ability to generate ways to reach important goals and the requisite motivation to initiate and sustain movement toward goals. Suggestive evidence comes from Cheavens and colleagues [57] who tested an intervention to increase hope and found increases in meaning in life and decreases in anxiety and depressive symptoms for cancer patients. Sustaining hope in the longer term may be particularly helpful for coping with recurrence.

In summary, qualitative study of women coping with breast or gynecologic cancer recurrence identified notable differences in their emotions in response to the initial and recurrence diagnoses and a changed social environment. Differences included depressive symptoms, shrinkage in the size of one’s social network, and social support erosion. These findings suggest biobehavioral strategies with the addition of others such as mindfulness, enhancing hope, and social support enhancement as possibilities to assist those coping with recurrence.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients for their kind participation and thank Jennifer Cheavens for her thoughtful comments regarding treatment components. We acknowledge the following individuals for assitance with the research: Eleshia Morrison, Salene Wu, Tanesha Walker, David Wanner, Fatima Brunson, Kate Freeman, Katie Schatz, Peter Hwang, and Stephanie Davis. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R21 CA135005 and K05 CA098133).

Footnotes

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2013. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brewster AM, Hortobagyi GN, Broglio KR, Kau SW, Santa-Maria CA, Arun B, Buzdar AU, Booser DJ, Valero V, Bondy M, Esteva FJ. Residual risk of breast cancer recurrence 5 years after adjuvant therapy. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:1179–1183. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddiqi A, Given CW, Given B, Sikorskii A. Quality of life among patients with primary, metastatic and recurrent cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care (English Language Edition) 2009;18:84–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenne Sarenmalm E, Öhlén J, Odén A, Gaston-Johansson F. Experience and predictors of symptoms, distress and health-related quality of life over time in postmenopausal women with recurrent breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2008;17:497–505. doi: 10.1002/pon.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen BL, Shapiro CL, Farrar WB, Crespin TR, Wells-Di Gregorio SM. Psychological responses to cancer recurrence: A controlled prospective study. Cancer. 2005;104:1540–1547. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munkres A, Oberst M, Hughes SH. Appraisal of illness, symptom distress, self-care burden, and mood states in patients receiving chemotherapy for initial and recurrent cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1992;19:1201–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brothers BM, Andersen BL. Hopelessness as a predictor of depressive symptoms for cancer patients coping with recurrence. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:267–275. doi: 10.1002/pon.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahon SM, Cella DF, Donovan MI. Psychosocial adjustment to recurrent cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 1990;17:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Body JJ, Lossignol D, Ronson A. The concept of rehabilitation of cancer patients. Current Opinion in Oncology. 1997;9:332–340. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199709040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kullmer U, Stenger K, Milch W, Zygmunt M, Sachsse S, Munstedt K. Self-concept, body image, and use of unconventional therapies in patients with gynaecological malignancies in the state of complete remission and recurrence. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 1999;82:101–106. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(98)00226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahon SM, Casperson DM. Exploring the psychosocial meaning of recurrent cancer: A descriptive study. Cancer Nursing. 1997;20:178–186. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199706000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisman AD, Worden JW. The emotional impact of recurrent cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Onocology. 1986;3:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hann DM, Oxman TE, Ahles TA, Furstenberg CT, Stuke TA. Social support adequacy and depression in older patients with metastatic cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1995;4:216–221. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newsom JT, Schulz R. Social support as a mediator in the relation between functional status and quality of life in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:34–44. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.11.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edelman S, Kidman AD. Application of cognitive behaviour therapy to patients who have advanced cancer. Behaviour Change. 2000;17:103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherwood P, Given BA, Given CW. A cognitive behavioral intervention for symptom management in patients with advanced cancer. Oncological Nursing Forum. 2005;32:1190–1198. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.1190-1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS. Project genesis: Assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:1036–1048. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Classen C, Butler LD, Koopman C, Miller E, DiMiceli S, Giese-Davis J, Fobair P, Carlson RW, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Supportive-expressive group therapy and distress in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A randomized clinical intervention trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:494–501. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angiola JE, Bowen AM. Quality of life in advanced cancer: An acceptance and commitment therapy view. The Counseling Psychologist. 2013;41:313–335. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine. 2000;51:843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinquart M, Duberstein PR. Associations of social networks with cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2010;75:122–137. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, Glaser R, Emery CF, Crespin TR, Shapiro CL, Carson WE., 3rd Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: A clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:3570–3580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andersen BL, Thornton LM, Shapiro CL, Farrar WB, Mundy BL, Yang HC, Carson WE., 3rd Biobehavioral, immune, and health benefits following recurrence for psychological intervention participants. Clinical Cancer Research. 2010;16:3270–3278. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen BL, Golden-Kreutz DM, Emery CF, Thiel DL. Biobehavioral intervention for cancer stress: Conceptualization, components, and intervention strategies. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2009:253–265. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersen BL, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. A biobehavioral model of cancer stress and disease course. American Psychologist. 1994;49:389–404. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.5.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atlas.Ti. Software, S; Berlin: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: A thematic analysis and code development. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snyder CR, Rand KL, King EA, Feldman DB, Woodward JT. “False” Hope. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;58:1003–1022. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gum A, Snyder CR. Coping with terminal illness: The role of hopeful thinking. J Palliat Med. 2002;5:883–894. doi: 10.1089/10966210260499078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wrzus C, Hanel M, Wagner J, Neyer FJ. Social network changes and life events across the life span: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:53–80. doi: 10.1037/a0028601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, Steptoe A. Do stress-related psychological factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. 2008;5:466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheard T, Maguire P. The effect of psychological interventions on anxiety and depression in cancer patients: Results of two meta-analyses. British Journal of Cancer. 1999;80:1770–1780. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schneider S, Moyer A, Knapp-Oliver S, Sohl S, Cannella D, Targhetta V. Pre-intervention distress moderates the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for cancer patients: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;33:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9227-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotopf M, Chidgey J, Addington-Hall J, Ly KL. Depression in advanced disease: A systematic review part 1. Prevalence and case finding. Palliative Medicine. 2002;16:81–97. doi: 10.1191/02169216302pm507oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: Five year observational cohort study. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2005;330:1–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38343.670868.D3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waller NG, Compas BE, Hollon SD, Beckjord E. Measurement of depressive symptoms in women with breast cancer and women with clinical depression: A differential item functioning analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2005;12:127–141. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cuijpers P, Smit F. Excess mortality in depression: A meta-analysis of community studies. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2002;72:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giese-Davis J, Collie K, Rancourt KM, Neri E, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Decrease in depression symptoms is associated with longer survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: A secondary analysis. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:413–420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wegner DM, Broome A, Blumberg SJ. Ironic effects of trying to relax under stress. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. Guilford Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Stress-processes and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:107–113. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Zurilla TJ, Goldfried MR. Problem solving and behavior modifications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1971;78:107–126. doi: 10.1037/h0031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nezu CM, Tsang S, Lombardo ER, Baron KP. Complementary and alternative therapies. In: Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Gellar PA, editors. Handbook of psychology: Health psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang HC, Thornton LM, Shapiro CL, Andersen BL. Surviving recurrence: Psychological and quality of life recovery. Cancer. 2008;112:1178–1187. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giese-Davis J, Koopman C, Butler LD, Classen C, Cordova M, Fobair P, Benson J, Kraemer HC, Spiegel D. Change in emotion-regulation strategy for women with metastatic breast cancer following supportive-expressive group therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:916–925. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koopman C, Hermanson K, Diamond S, Angell K, Spiegel D. Social support, life stress, pain and emotional adjustment to advanced breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1998;7:101–111. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199803/04)7:2<101::AID-PON299>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kugaya A, Akechi T, Okamura H, Mikami I, Uchitomi Y. Correlates of depressed mood in ambulatory head and neck cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:494–499. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199911/12)8:6<494::aid-pon403>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bolger N, Foster M, Vinokur AD, Ng R. Close relationships and adjustment to a life crisis: The case of breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:283–294. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moyer A, Salovey P. Predictors of social support an psychological distress in women with breast cancer. Journal of Health Psychology. 1999;4:177–191. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alferi SM, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weiss S, Dura RE. An exploratory study of social support, distress, and life disruption among low-income hispanic women under treatment for early stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20:41–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piet J, Wurtzen H, Zachariae R. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on symptoms of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:1007–1020. doi: 10.1037/a0028329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pinquart M, Frohlich C, Silbereisen RK. Cancer patients’ perceptions of positive and negative illness-related changes. J Health Psychol. 2007;12:907–921. doi: 10.1177/1359105307082454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pinquart M, Silbereisen R, Fröhlich C. Life goals and purpose in life in cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2009;17:253–259. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snyder CR, Irving L, Anderson JR. Hope and health: Measuring the will and the ways. In: Snyder C, Forsyth DR, editors. Handbook of social and clinical psychology: The health perspective. Pergamon Press; New York: 1991. pp. 285–305. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheavens JS, Feldman DB, Gum A, Michael ST, Snyder CR. Hope therapy in a community sample: A pilot investigation. social Indicators Research. 2006;77:61–78. [Google Scholar]